Abstract

The Kangxi Southern Inspection Tours strengthened the Qing Dynasty’s control over Jiangnan Buddhism, thereby promoting the standardization and officialization of Jiangnan temples and externalizing imperial power through images and physical space. Taking Jinshan Temple as an example, this study combines spatial analysis of architecture and image analysis used by art historians to examine the transformation between physical and pictorial spaces in Jinshan Temple, revealing the spatial operation of imperial power. The intervention of imperial power sparked the space reconstruction of Jinshan Temple through a process of “merger-occupation-infiltration-adjustment”. Thus, the control measures of Kangxi are revealed, including the emphasis on the geographical significance of the temple, space occupation of royal buildings, change in landscape, and the adaptation of monks by adjusting their imagination of the sacred space. By determining the spatial reconstruction, we observe that the spatial strategy of power reflects Kangxi’s religious attitude toward Buddhism of “neither promoting nor suppressing, but treating it reasonably” 朕惟置之焉能有無之間, which may enrich our understanding of the influence of Kangxi’s Southern Inspection Tours on Jiangnan’s religious space.

1. Introduction

Imperial inspection tours, a continuing ritual activity since ancient times (Qin 1880), were appreciated by emperors and were regarded as a form of ritual governance and benevolent civilian administration in Confucian classics (Chang 2007). Emperor Kangxi continued this Han Confucian tradition during his reign. He made six Southern Inspection Tours (hereafter Southern Tours or tours)—in 1684, 1689, 1699, 1703, 1705, and 1707—to prove the legitimacy of his regime to his Han subjects and present his image as an ideal Confucian ruler. During these tours, he intervened in Buddhist affairs by visiting temples and thus restraining the development of Jiangnan Buddhism. In the field of architecture, most of the studies of Kangxi’s Southern Tours focused on the physical construction of the temporary palace attached to the temple (Ma 2017; He 2018). Such space construction hardly reflects any in-depth research of Kangxi’s political intentions. This deficiency in traditional research focusing on the physical space can be addressed by the introduction of image research. The power relationship in the physical space was presented more intuitively through selective image recreation. Through research of the spatial relationship in images, the real intention and means of power operation of Emperor Kangxi can be deeply analyzed.

This study takes Jinshan Temple 金山寺 in Zhenjiang 鎮江 as an example to examine how Emperor Kangxi imposed imperial control over Jiangnan Buddhism during his Southern Tours. The adjustments and adaptations made by the monks on the temple are also assessed. Imperial power was externalized by means of spatialization, specifically of Buddhist temples. In this study, the term “space” includes two aspects: one is physical space, such as temple architecture and landscape; the other is the pictorial space formed by artists through the selective recreation of real scenes. For physical space, this study uses architectural methods to analyze the geographical location, historical succession, and spatial structure of Jinshan Temple. For pictorial space, the method proposed by Wu Hung, an art historian, is applied to analyze the space as the constitutive element in the specific meaning of an image (Hu. Wu 2018, p. 239). The images’ spatial structures can be analyzed by determining how specific content was represented, thus revealing the underlying power intention and political significance. Under the control of imperial power, the abovementioned two spaces interacted with each other and jointly promoted Jinshan Temple’s spatial reconstruction.

2. Jiangnan Temples during Kangxi’s Southern Tour

Different Qing Dynasty emperors had various perspectives on Buddhism. In contrast to Emperor Shunzhi 順治 (1638–1661) and Emperor Yongzheng 雍正 (1678–1735), Emperor Kangxi 康熙 (1654–1722) maintained distance from the religious world and did not participate in worship. In fact, he “hated it from birth” 生來便厭聞此種 (Xu 2014, p. 112) and considered Buddhism to be a heresy. Throughout his reign (1662–1722), he exercised restraint, management, and exploitation of Buddhism. Prior to Kangxi, the Qing emperors exerted varying levels of authority over Buddhism, but the majority of their Buddhist regulations were focused on the capital city and its surroundings (Tuo et al. 1976). However, Emperor Kangxi increased his grip over Jiangnan’s Buddhist temples through his Southern Tours and thereby expanded his political power. The Qing Emperors’ subsequent control over Buddhism in the Jiangnan region was the continuation of Kangxi’s Southern Tour.

During his tours, Emperor Kangxi visited numerous Jiangnan temples. The itinerary was vaguely described in the official documents of the Qing court, but among the Buddhist temples visited by the emperor, only Jinshan Temple, Daming Temple 大明寺, Tianning Temple 天寧寺, Ruiguang Temple 瑞光寺, Shengen Temple 聖恩寺, and Santa Temple 三塔寺 were recorded in the Qing Shilu 清實錄 and Qiju Zhu 起居注. Fortunately, Emperor Kangxi had inscriptions made for all the temples he visited on his tours (Liu 1988). From the statistics on the tablets and couplets of Jiangnan temples, we can deduce that more than 50 temples were visited during the emperor’s six Southern Tours, including those to which he sent inscriptions but did not visit in person.

2.1. Control of Jiangnan Temples

A large number of Ming supporters entered the temples as monks or fostered Buddhism in the early Qing dynasty. Therefore, anti-Qing and pro-Ming ideology infiltrated the temples (Yu 1999), especially in the Jiangnan region, which endangered the Qing Court’s authority. Emperor Kangxi knew that a blanket prohibition of Buddhism would not eliminate its religious power, which would become even stronger when it was revived. Therefore, he proposed to regulate Buddhism by “neither promoting nor suppressing, but treating it reasonably” 朕惟置之焉能有無之間 (Q. Li 2010, p. 340). Only by properly regulating religion can it be used by the regime to maintain public support. Emperor Kangxi encouraged the standardization and officialization of Jiangnan Buddhist temples through the control of religious affairs such as the ordination of monks, temple construction, and ritual system.

Historian Hamashima Atsutoshi pointed out that the emperor’s rewards were one of the key variables in determining whether the folk gods in Jiangnan were worshipped by the populace (Atsutoshi 2008, p. 118). During the Southern Tours, Emperor Kangxi rewarded Jiangnan temples with numerous tablets, couplets, Buddhist scriptures, and statues. At the same time, according to the statistics of Jiangnan Tongzhi 江南通志 and Zhejiang Tongzhi 浙江通志, the emperor provided grants to rebuild Jiangnan temples, such as Tianning Temple, Gaomin Temple, Jinshan Temple, Hufu Temple, Huiju Temple, and Da Bao’en Temple. According to the Qing Huidian 清會典, the Qing Court divided Buddhist temples into “imperial temples” 敕建寺廟 and “private temples” 私建寺廟 (Yi et al. 1992, pp. 3624–25). The abovementioned temples were categorized as “imperial temples,” which the empire supported in terms of property expansion and upkeep. In addition, memorials to the throne (Zouzhe 奏摺) during the Kangxi reign show that the appointment of monks in several temples was strictly managed. The abbots of Jinshan Temple, Gaomin Temple, and Tianning Temple were directly appointed by officials with the approval of the emperor (The First Historical Archives of China 1985, vol. 1, p. 141). Furthermore, the Bao’en Temple, Jinshan Temple, and Gaomin Temple were included in the official ritual system. On the emperor’s birthday, these temples held relevant Buddhist celebrations and local officials prayed with incense (The First Historical Archives of China 1985, vol. 4, p. 20; vol. 7, p. 1168; vol. 6, p. 62). In summary, Emperor Kangxi implemented five measures in the management of temples (also listed in Table 1) as follows: appointing the abbot, funding the temple construction, integrating the temple into the imperial ritual system, providing tablets and couplets to the temples, and providing Buddhist scriptures and statues. The majority of these temples were centered in Yangzhou 揚州府, Zhenjiang 鎮江府, Jiangning 江寧府, and Hangzhou 杭州府.

Table 1.

Statistics of Jiangnan Buddhist temples during Emperor Kangxi’s Southern Tours.

2.2. Reshuffle of Jiangnan Temples’ Distribution

After the Tang and Five Dynasties, the southern Buddhist patterns may be separated into three regions: Jiangnan 江南, Lingnan 嶺南, and Bashu 巴蜀. The center of Jiangnan is Hangzhou 杭州, where Buddhist temples experienced unprecedented prosperity after the economic and cultural development of the Southern Song Dynasty. At that time, most of the top-level temples were gathered in and around Hangzhou, according to the “Five Mountains and Ten Temples” (“Wushan shicha” 五山十刹) official temple hierarchy. During the Yuan Dynasty, the Jiangnan region continued the Southern Song Dynasty’s distribution of Buddhism, with Hangzhou serving as its center (S. Zhang 2000). Hence, Nanjing—that is, Jiangning Prefecture in the Qing Dynasty—was developed later during the Ming Dynasty. During the Kangxi period of the Qing Dynasty, the Southern Tours launched a reshuffle of the original distribution of Jiangnan Buddhist temples.

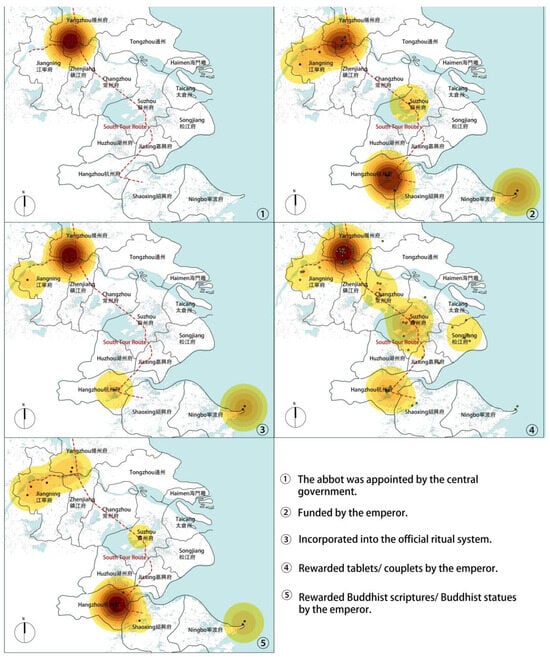

A kernel density analysis (Figure 1) shows that in addition to Hangzhou Prefecture, wherein a large number of Buddhist temples were concentrated since the Southern Song Dynasty, Emperor Kangxi’s control over Buddhist temples primarily focused on the junction of Yangzhou and Zhenjiang Prefectures, which was closely related to the political situation in the early Qing Dynasty. During the reign of Shunzhi, the Hongguang regime of the Southern Ming was still entrenched in Jiangning. In the east, Zhenjiang and Yangzhou were situated on either side of the Yangtze River, and both served as Jiangning’s military entry points. In Yangzhou and Zhenjiang, the forces of Southern Ming fought with the Qing army, and the local people were particularly ferocious in their opposition to the Qing government. Local politics remained unstable up until the early years of the Kangxi reign (Meyer-Fong 2003). The Southern Tours provided Emperor Kangxi with a considerable opportunity to administer and control the Buddhist temples in Jiangnan, particularly those in Yangzhou and Zhenjiang. Eventually, the imperial power control system was formed, with the Yangzhou–Zhenjiang area and Hangzhou Prefecture as the two centers, extending to the surrounding areas and even the whole Jiangnan region.

Figure 1.

Kernel density analysis of Jiangnan Buddhist temples during the Kangxi reign.1 Diagram by authors.

3. Visit and Images of Jinshan Temple in the Kangxi Reign

Jinshan Temple was appropriated by the emperor for rebuilding and was dubbed as the “Imperial Jiangtian Temple” 敕建江天禪寺 as early as the 23rd year of Kangxi (1684), that is, during Kangxi’s first Southern Tour (Shi 2021, p. 173). Jinshan was the first Buddhist temple in Jiangnan to be integrated into the imperial administration system.

3.1. Records of Kangxi’s Visit to Jinshan Temple

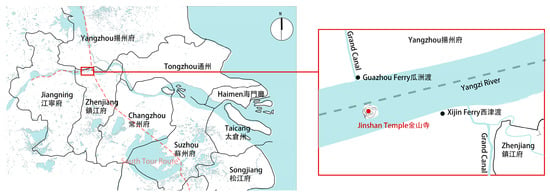

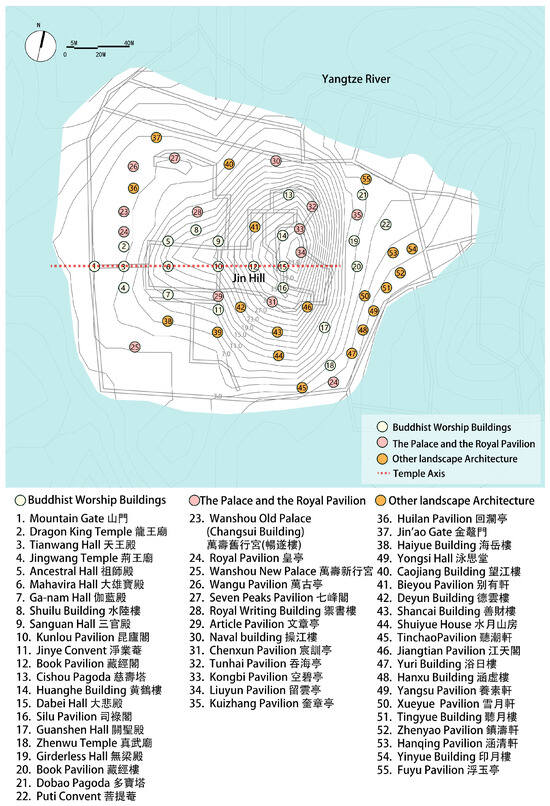

Jinshan Temple occupies the west gentle slope of Jinshan Hill, sitting east and facing west. Geographically, Jinshan was an island located at the confluence of the Grand Canal and the Yangtze River during the Kangxi reign (Figure 2) and was thus one of the most important mooring points for the royal boat as it traveled south along the river. According to statistics of his visits to the Jiangnan temples in Qing Shilu and Qiju Zhu, Emperor Kangxi most frequently visited Jinshan Temple during his Southern Tours, with 10 trips there and back, a number far more than any of his visits to other temples. Subsequently, Kangxi’s tour itinerary was basically imitated by his grandson, Emperor Qianlong, who visited Jinshan Temple on each tour, which amounted to 17 visits in 30 years, demonstrating the importance of this temple.

Figure 2.

Geographical map of Jinshan Temple. Diagram by authors.

3.2. Image of Jinshan Temple

During the Kangxi reign, numerous images related to Jinshan Temple were created and could be further split into official and folk creations depending on their funder. Official images were further divided into palace paintings and documentary illustrations.

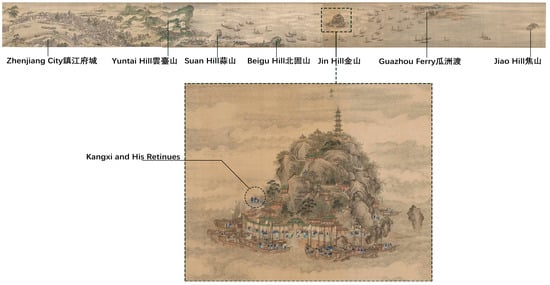

The palace paintings are titled Kangxi’s Southern Tours 康熙南巡圖, which took six years to complete and were painted by Wang Hui 王翬 (1632–1717) and court painters such as Yang Jin 楊晉 (1644–1728) and Leng Mei 冷枚 (1669–1742) beginning in 1691, two years after Kangxi’s second Southern Tour (L. Li 2013). This painting is a conceptual portrayal of significant events and locations during that tour and serves as a graphical interpretation of important aspects of the trip, given that the painter did not actually travel with the emperor (Hearn 1990, p. 55). This painting contained 12 scrolls. The beginning of Vol. 6 (Figure 3) depicts the scene from Guazhou 瓜州 crossing to Zhenjiang City 鎮江府城. From right to left, the painting depicted Jiaoshan Hill 焦山, Guazhou Ferry 瓜洲渡, Jinshan Hill 金山, Beigushan Hill 北固山, Xijin Ferry 西津渡, Suanshan Hill 蒜山, Yuntaishan Hill 雲臺山, and Zhenjiang City 鎮江府城.

Figure 3.

Part of Kangxi’s Southern Tour, Scroll 6, 1695, image cited from Jinmo Tang, https://www.sothebys.com/zh/auctions/ecatalogue/2016/roy-and-marilyn-papp-collection-of-chinese-paintings-n09544/lot.576.html?locale=zh-Hant, access on 20 May 2023.

In addition to the paintings funded by the palace, official images also included illustrations attached to various gazetteers (zhi 志). During the Kangxi reign, Jinshan Longyou Temple Gazetteer (Jinshan Longyou Chan Si Zhilue 金山龍遊禪寺志略), Zhenjiang Prefecture Gazetteer (Zhengjiang Fuzhi 鎮江府志), and Imperial Jiangtian Temple Gazetteer (Chijian Jinshan Jiangtian Chansi Xinzhi 敕建金山江天寺新志) had illustrations of Jinshan Temple and were compiled. The above three gazetteers were, respectively, compiled in 1681, 1685, and 1720, which corresponded to the times before Kangxi’s first Southern Tour, after the first tour, and at the end of the sixth Tour. Therefore, the latter two gazetteers completed the lacking records of Kangxi’s Southern Tours in Jinshan Longyou Temple Gazetteer, of which the frontispiece illustration can be regarded as the pictorial correction of the image of Jinshan after the first Southern Tour.

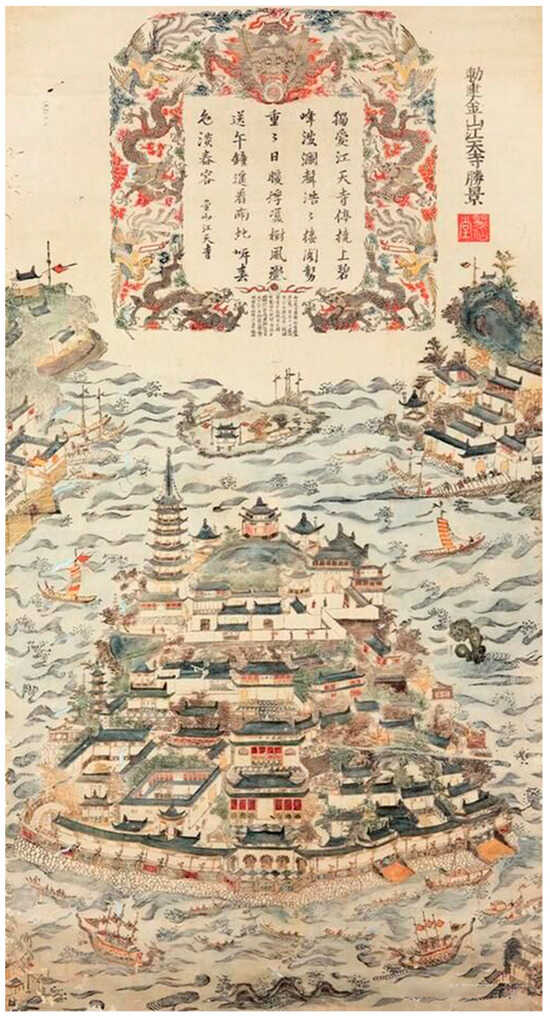

Among the folk images, the woodblock print Scenic Map of Imperial Jinshan Jiangtian Temple (Chijian Jinshan Jiangtian Si Shengjing Tu 敕建金山江天寺勝景圖) with ink plates and colors is an important representative of this period. The existing edition of the Yongzheng reign reflects the image of Jinshan Temple after Kangxi’s Southern Tours and before those of Qianlong. In this print, Jinshan Temple stands in the center as the focal point. The poem Jinshan Jiangtian Temple 金山江天寺by Emperor Kangxi was written on the decoration with a dragon pattern above the temple, and the surroundings of Jinshan such as Guazhou Ferry 瓜洲渡, Jiaoshan Hill 焦山, and Chaoan Temple 超岸寺 were depicted in order from right to left, respectively.

4. Spatial Reconstruction of Jinshan Temple during Kangxi’s Southern Tour

4.1. Merger: The Jinshan Temple in the Imperial Political Territory

During the Song and Yuan dynasties, Jinshan Temple was only listed as the eighth in rank of the Jaicha 甲刹 in the official temple hierarchy of “Five Mountains and Ten Temples” (Wushan Shicha 五山十刹), far behind others such as Jingci Temple 淨慈寺 and Lingyin Temple 靈隱寺. Given that Jinshan Temple was not prominent among Jiangnan’s Buddhists prior to the Qing Dynasty, the emperor’s decision to choose this site as a mooring point was actually based on both its strategic importance and its location at a major water transportation hub. Surrounded by water on all sides, Jinshan Temple was simple to defend and challenging to attack. In the early years of Shunzhi’s reign (1644–1661), Jinshan Temple was an important area contested by the forces of Southern Ming and the Manchu regime (Lu 1901, p. 16). The Southern Ming people once built walls in Jinshan Temple to store food for use in battle against the Qing army. After more than 40 years of this war against this strategic place, Emperor Kangxi attempted to declare his sovereignty by climbing the hill and overlooking the surroundings, as described in Kangxi’s Southern Tour, Scroll 6 康熙南巡圖·第六卷.

At the beginning of the scroll in Kangxi’s Southern Tour, Scroll 6 (Figure 3), the royal boat was moored at the piedmont, and Emperor Kangxi was depicted on a high platform looking into the distance. This scene was consistent with the record in Notes on the Southern Tour 南巡筆記by Emperor Kangxi: “I led my retinues to look into the distance for thousands of miles” 朕率扈從諸臣,一一探眺,縱目千里. This platform, named Miaogao Terrace 妙高臺, was located in the Jinshan Temple and was first built by the monk Liao Yuan 釋了元 (1032–1098) during the Song Dynasty. The preface of Liao Yuan’s poem said: “When I looked east to worship for a moment, there was a sunset in the northwest of Jiaoshan Mountain, with the star shining above, so I built Miaogao Terrace at the abbot’s chamber, potentially opposite to it” 東望瞻禮,須臾,焦山西北霞光,上燭星漢,即于方丈構妙高臺,潛對其地 (L. Zhang 1996, p. 113). Therefore, when it was first built, the Miaogao Terrace was located at the top of Jinshan Hill, from which people could see Jiaoshan Hill on its east side. However, during the Ming Dynasty, a monk rebuilt the platform halfway up the southwest slope. From then on, the terrace was “covered by overlapping mountains, and visitors could no longer see Jiaoshan Hill on Miaogao Terrace” 為層巒掩蔽,焦山不可望而見 (L. Zhang 1996, p. 113). After the renovation in the 23rd and 26th years of Kangxi’s reign, Miaogao Terrace became completely oriented to the west, which increased the difficulty of viewing the east. During the Qing Dynasty, Zhenjiang City was geographically situated 4 km to the east of Jinshan Hill and thus could not be seen in the field when viewed from the Miaogao Terrace (Figure 2). However, in Kangxi’s Southern Tour, Scroll 6, Zhenjiang City was drawn to the west of Jinshan Hill, forming a line-of-sight correlation with the Miaogao Terrace. This overlooking correlation in the painter’s imagination may originate from the special inspiration of Emperor Kangxi.

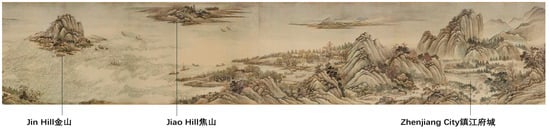

The segment mentioned above can be compared with another image that Wang Hui drew during the same period. The Yangtze River Wanli Map 長江萬里圖, drawn in the 37th year of Kangxi’s reign (1698) and 3 years after Wang Hui completed Kangxi’s Southern Tour, was an impromptu work after he came across Yan Wengui’s 燕文貴 (967–1044) Yangtze River Scroll 長江卷 (Weng 2018). In this scroll, Wang Hui drew Zhenjiang City to the east of Jinshan Hill (Figure 4), faithful to its actual geography. By contrast, Wang Hui’s unusual orientation of Zhenjiang City in Kangxi’s Southern Tour, Scroll 6 was quite political; more than 40 years after the defeat of the Southern Ming regime, Emperor Kangxi ordered the removal of the defensive wall built by the Southern Ming forces at Jinshan Temple and the rebuilding of the landscape corridor. At the same time, he climbed Miaogao Terrace and “looked over” Zhenjiang City. By looking down from above, the emperor asserted his dominion over Jinshan Temple and its surrounding areas, and thus the entire Jiangnan region, as an occupier rather than a visitor. In this case, Jinshan Temple was more than an isolated island in the middle of the river; it was also a vital anchor point for Emperor Kangxi in unifying Jiangnan’s political and cultural territories.

Figure 4.

Part of Yangtze River Wanli Map, 1698, image cited from Boston Museum of Art, https://collections.mfa.org/objects/491924/ten-thousand-miles-along-the-yangzi-river?ctx=6cb731be-84f2-447a-aa1e-83bf7af77938&idx=17, access on 20 May 2023.

4.2. Occupation: Construction of Royal Buildings

As previously mentioned, Emperor Kangxi did not regard Jinshan Temple as a purely religious place, but instead gave it a political function to maintain local loyalty and territorial unity, thus consolidating absolute imperial power over religious authority. At the same time, beginning with Kangxi’s third tour in 1699, imperial power gradually intervened in the physical space construction of Jinshan Temple through spatialization (Table 2).

Table 2.

Construction of Jinshan Temple during the Kangxi reign. Diagram by authors.

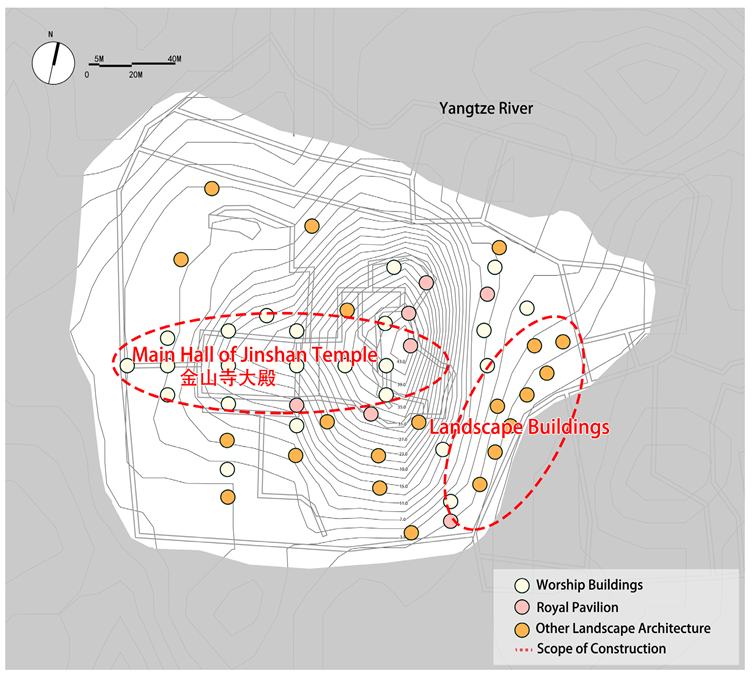

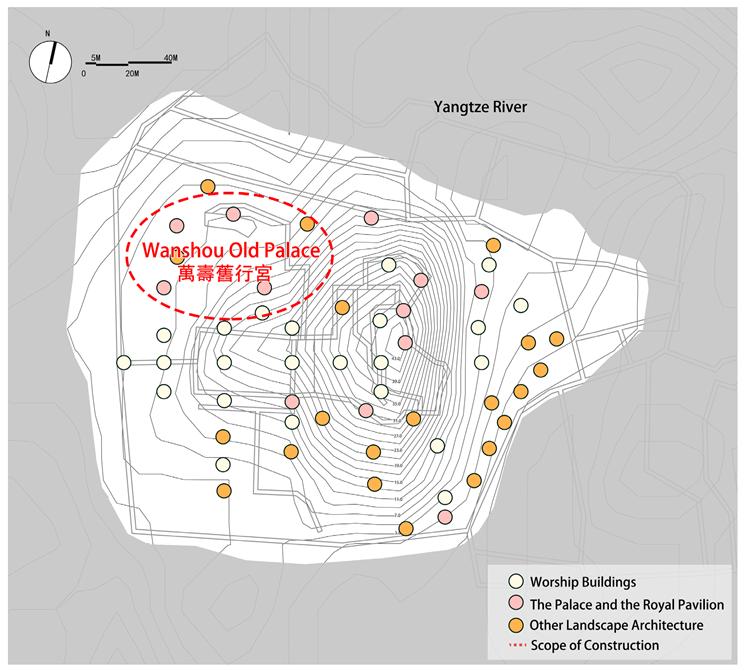

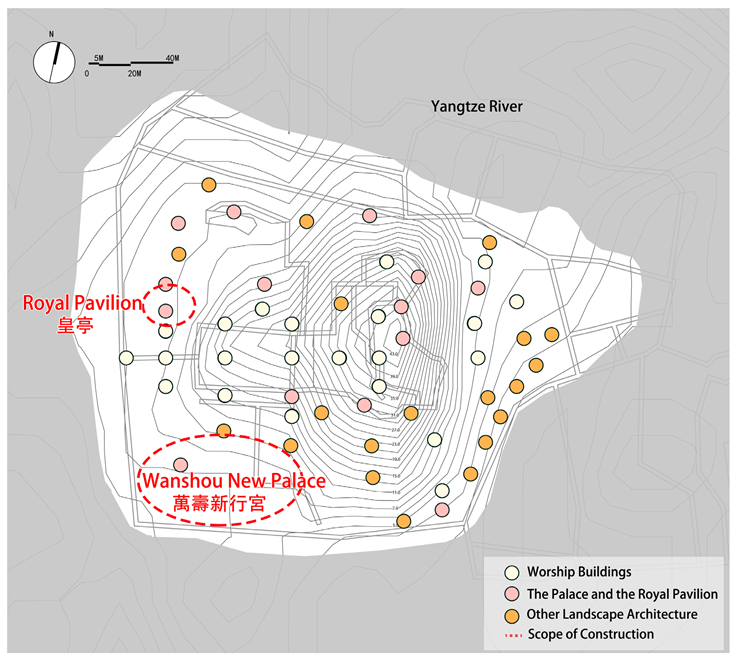

After the Ming–Qing dynasty transition, the main halls of Jinshan Temple had been dilapidated and even partially collapsed. In the Shunzhi reign, the abbot of Jinshan Temple, Tiezhou Xinghai 鐵舟行海 (1608–1683), worked on temple renovations for more than 30 years. However, during Emperor Kangxi’s first tour, buildings such as the Wuliang Hall were still unrepaired (Tiezhou Xinghai 2001, pp. 1–11). After his first Southern Tour, Emperor Kangxi allocated funds for the Jinshan Temple’s renovation, which was mainly based on the original main hall and did not include the construction of the temporary palace. Thus, the original spatial structure of the hill was retained. With the emperor’s permission, construction of the temporary palace began in 1698, a year before the third Southern Tour. The temporary palace was located on the northwest slope of Jinshan Hill, replacing the Dache Hall 大徹堂 of the temple. Built by Cao Yi 曹寅 (1658–1712) of Jiangning weaving 江甯織造, the temporary palace was named Wanshou Old Palace 萬壽舊行宮 (Shi 2021, p. 183), where Emperor Kangxi stayed during his two Southern Tours in 1699 and 1703. Later on, Cao Yin and Li Xu 李煦 (1655–1729) of Suzhou weaving 蘇州織造 donated their salaries to build another temporary palace one year before the fifth Southern Tour (1704). The new palace was named Wanshou New Palace 萬壽新行宮 (Shi 2021, p. 183) and was built on the southwest slope of the Hill, where logistics buildings such as Kusi 庫司 and Xiangji 香積 used to be located. The old palace in the northwest was given to the Empress Dowager. In addition, on the east slope of Jinshan Hill, landscape buildings such as Yinyue 印月樓, Tingyue 聽月樓, and Hanxu 涵虛樓 were built for the emperor’s recreation (Shi 2021, p. 184).

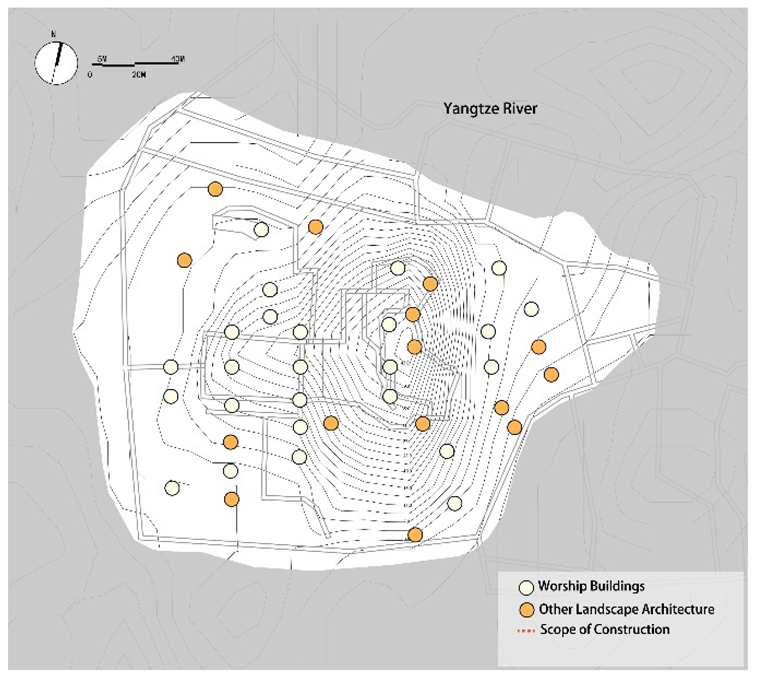

As the main place for daily living and handling government affairs for the emperor during the Southern Tours, the temporary palace built for his brief stays away from the capital was one of the physical manifestations of imperial power penetrating the localities. The construction activities sparked by Kangxi’s Southern Tours allowed for space dedicated to advocating imperial power to enter the architectural system of the Jinshan Temple. After several tours, except for the west slope where the temple’s main hall was located, the other three sides either became the palace or were rebuilt as landscape sightseeing places for the emperor to visit. Based on the east–west axis of the temple, a new spatial organization of Buddhist halls surrounded by imperial architecture was formed (Figure 5). The actual area available for the construction of the Buddhist Hall was significantly reduced compared with the previous generation, and thus the construction scale of Buddhist space in Jinshan Temple was effectively controlled.

Figure 5.

Diagram of Jinshan Building location during the Kangxi reign. Diagram by authors.

4.3. Infiltration: Landscape as a Medium of Power

Emperor Kangxi effectively restrained the development scale of Jinshan Temple in terms of physical space construction. At the same time, the transformation of the image of the Jinshan Temple in official images revealed another hidden intention.

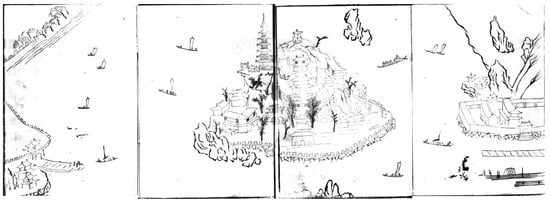

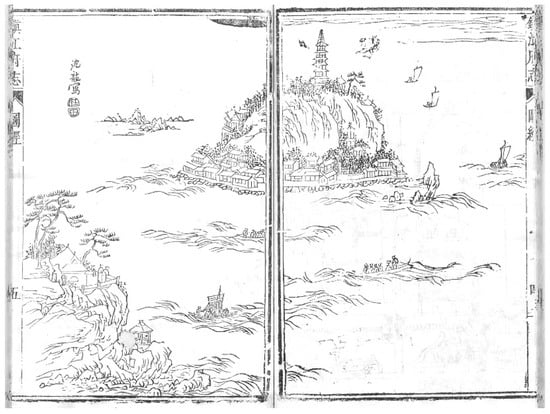

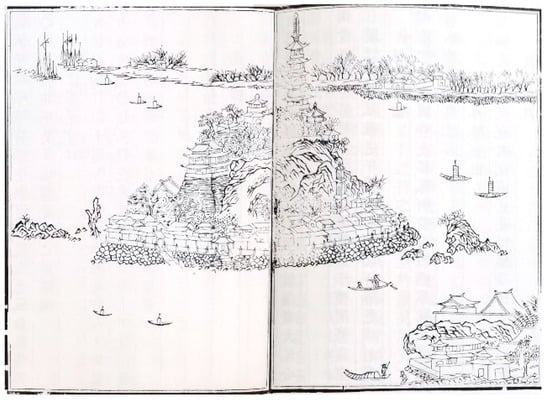

In the Jinshan Map of Jinshan Longyou Temple Gazetteer (Figure 6), published before the Southern Tour, the front elevation of the temple was highlighted, and Mountain Gate山門, Tianwang Hall 天王殿, Mahavira Hall 大雄寶殿, Kunlu Pavilion 昆盧閣, and Dabei Hall 大悲殿 were painted from the piedmont to the hilltop. All these Buddhist halls were arranged on the central axis from east to west. However, during the southern tour, the official images created mainly depicted the east, south, and north slopes, while the front elevation of Buddhist halls on the west slope was deliberately hidden. The Kangxi’s Southern Tour, Scroll 6, focused on the southern slope of the Jinshan Hill but only briefly included the main hall of the temple on the western slope. The illustration of Jinshan Hill in the Zhenjiang Prefecture Gazetteer (Figure 7), published in the 24th year of Kangxi (1685), also hid the main hall on the western slope. This perspective was later imitated in the illustration of the Imperial Jiangtian Temple Gazetteer (Figure 8), published in the 59th year of Kangxi (1720). The illustration depicted the landscape architecture that was newly built for the Southern Tours on the eastern slope, highlighting its importance through visual representation.

Figure 6.

Jinshan Map in Jinshan Longyou Temple Gazetteer. Source: (Tiezhou Xinghai 2001, pp. 4–5).

Figure 7.

Illustration in the Zhenjiang Prefecture Gazetteer. Source: (Gao and Zhu 1685, vol. 1).

Figure 8.

Illustration in the Imperial Jiangtian Temple Gazetteer. Source: (Shi 2021, p. 178).

Comparison of the above figures reveals that the newly created official images during the Southern Tours all seemed to highlight the characteristics of Jinshan as a scenic spot and hid the Buddhist space to diminish its religious attributes. This point can also be proven by the inscriptions written after Emperor Kangxi personally funded the renovation of Jinshan Temple. In 1686, Emperor Kangxi wrote in the Imperial Jinshan Jiangtian Temple Inscription (Yuzhi Jinshan Jiangtian Si Bei Ji 禦制金山江天寺碑記): “When I passed through this place on my Southern Tour, I stopped at the temple for a rest to feel the calm flow of the Yangtze River and the connection between the water and the sky. As a result, I wrote down the words ‘A Glance at the River and Sky’ in the temple and ordered the temple to be renovated, so as not to bother my subjects with this matter. After the renovation, I was invited to write a plaque. The magnificent beauty of the Jinshan Temple should be enough to increase the wonders of the landscape. Because of the memory of the view of the vast, I can still imagine it, so it was named ‘Jiangtian Temple’.” 朕南巡過此,停憩山寺,撫長江之安流,見水天之相接,曠焉興懷,書 ‘江天一覽’四字留之寺中,爰命葺而新之,不以勞吾民. 事竣請其額,其瑰壯巨麗當益足以增江山之奇矣,因憶舊觀浩淼澄,空闊無際,猶可心會,遂名之曰 ‘江天寺’雲 (Shi 2021, p. 174). As can be gleaned from the inscription, Emperor Kangxi’s main consideration for the renovation of Jinshan Temple was the embellishment of the landscape rather than the accumulation of merit in the religious world. Notably, Emperor Kangxi named it Jinshan Temple based on its scenic situation. This was not an isolated case in Kangxi’s reign. For example, Gaomin Temple 高旻寺 was named after the pagoda that soared into the sky beside the temple, where “Min” means “high and wide sky”. Xiangfu Temple 香阜寺 was named after the hill where the temple was located, where “Fu” means “a hill”. Apparently, these newly developed temples during the Southern Tours were all renamed by the emperor according to their unique geographical situation or scenic features.

Therefore, the infiltration of power gradually worked through the medium of landscape; Emperor Kangxi did not mention the yearning for religious pilgrimage sites in his inscriptions but imposed the literati aesthetic taste of landscape on the Buddhist places. For one thing, this tendency was related to Emperor Kangxi’s attitude of “disinterest in Daoism and Buddhism” 不好仙佛 (Xu 2014, p. 112). For another, this tendency also reflects Emperor Kangxi’s control strategy on Buddhism; that is, he did not use violent or powerful political means, but rather he intervened softly in the control of temples. Emperor Kangxi used the literati aesthetic of landscape to praise the geographical environment of the temples, and thus he gently co-opted and assimilated Buddhism, which he considered heresy, into his control as a Confucian supreme ruler. In this process, the landscape provided legitimacy as a medium for the intervention of imperial power, enabling the emperor to be considered as accommodating to monks while still effectively controlling the development of the Buddhist temple.

4.4. Adjustment: Response of the Temple under Imperial Control

Kangxi’s de-religious strategy that highlighted Jinshan Temple as a scenic spot rather than a religious pilgrimage site, in turn, provided a new narrative for the folk imagination of the temple.

The Scenic Map of the Imperial Jinshan Jiangtian Temple (Figure 9) was drawn after Kangxi’s Southern Tours. On the right side of the print is the square seal of “Juxian Tang” 聚仙堂, which is assumed to represent the name of the painting shop. Based on a preliminary comparison of the source with other Buddhist mountain images dating from the same period, we may deduce the methods of creation of this artwork. According to scholar Wu Han, other images of Buddhist mountains, such as the Complete Map of Great Jiuhua Mountain in Southeast China (Dongnan Diyi Da Jiuhua Shan Quan Tu 東南第一大九華山全圖), Complete Map of the Imperial Putuo Mountain in the South China Sea (Chijian Nanhai Putuo Shan Jing Quan Tu 敕建南海普陀山境全圖), and the Scenic Map of Great Imperial Emei Mountain (Yuti Tianxia Da Emei Shan Shengjing Tu 禦題天下大峨眉山勝景圖), were all printed and distributed to followers at the temple’s cost. The Complete Map of the Sacred Landscape of Wutai Mount (Wutai Shan Shengjing Quan Tu 五臺山聖境全圖) was even drawn by the monks of the temple (Ha. Wu 2020). Therefore, this kind of image had the common characteristics showing that the creator or funder was the temple and the audience was the pilgrim. Combined with the above analysis, we can infer that the Scenic Map of Imperial Jinshan Jiangtian Temple was also funded by the Jinshan Temple and made at the folk painting shop named “Juxian Tang” to attract pilgrims and expand the religious influence of the temple.

Figure 9.

Scenic Map of Imperial Jinshan Jiangtian Temple. Source: (Gao 2014, p. 102).2

The depiction of Jinshan Temple in the Scenic Map of the Imperial Jinshan Jiangtian Temple shows evident symmetry and centrality. Jinshan Hill was drawn as an isosceles triangle, and the architectural boundaries of the palaces on the north and south sides converged towards the center, strengthening the central axis formed by the Tianwang Hall, Mahavira Hall, and other Buddhist halls. This print used a solemn composition similar to that of an icon, making the entire mountain become the object of pilgrimage. Thus the viewing process of the audience was similar to a pilgrimage process. The buildings at the top of the central axis, the most sacred place for prayer, were neither pagodas nor Buddhist halls, but rather three hexagonal pavilions that served landscape functions.

The three pavilions were rebuilt after Kangxi’s first Southern Tour. Seen from the west slope, Kongbi Pavilion 空碧亭 was in the middle, while Tunhai Pavilion 吞海亭 and Liuyun Pavilion 留雲亭 were located on both sides. Built at the top of Miaogao Peak, the highest terrain of Jinshan Hill, Kongbi Pavilion housed Emperor Kangxi‘s Imperial Jinshan Jiangtian Temple Inscription inscribed by Zhang Yushu 張玉書 (1642–1711), the Bachelor of the Imperial Academy 翰林院學士, after the renovation of the Jinshan Temple; Tunhai Pavilion on the north side housed Kangxi‘s poem tablet, named “Jinshan Temple’s night moon” 金山寺夜月; and Liuyun Pavilion on the south side had the four-character tablet, named “A Glance at the River and Sky” 江天一覽, which was inscribed by Yang Fengxiang 楊鳳翔, the general of Jinhai 鎮海將軍 in 1687 (Shi 2021, pp. 173–380).

These three landscape buildings, rather than Buddhist halls or pagodas, together became the most sublime elements of the sacred space of Jinshan Temple, namely, the symbolic space of Emperor Kangxi’s unification of religious heresies with literati landscape aesthetics, but also an important symbol of the temple to show off its imperial grace. This spatialization became the means for the temple to consciously seek royal protection in the context of the Southern Tours. Meanwhile, similar to the intention of the above images, the monks of Jinshan Temple devised the legend of the dragon’s arrival, claiming that the dragon emerged in the sky unexpectedly when Emperor Kangxi visited Jinshan Temple and sat in Tianwang Hall in 1705.

This legend was recorded in the Imperial Jiangtian Temple Gazetteer. The “Tianwang” and the “Dragon” were Buddhist Dharma protector gods who symbolized the imperial power’s support for Buddhism. Since then, Jinshan Temple’s prestige has risen in the Buddhist community, and is considered one of the four major Zen temples, along with Gaomin Temple 高旻寺 in Yangzhou, Tianning Temple 天寧寺 in Changzhou, and Tiantong Temple 天童寺 in Ningbo.

5. Conclusions

The Southern Inspection Tours strengthened the imperial control over Jiangnan Buddhist Temples, represented by Jinshan Temple, and enhanced the Qing Court’s dominion over Jiangnan Buddhism. In this context, the ordinary Jinshan Temple was transformed into an imperial temple that was directly managed by the Qing Court. Imperial power intervened in local religious affairs through spatialization, which caused the reconstruction of Jinshan Temple space through a process of “merger-occupation-infiltration-adjustment”, and finally formed the temple layout dominated by imperial space. Emperor Kangxi designated Jinshan Temple as a geographical anchor point in his vast empire, and thus restricted the scale of the temple through the construction of the imperial building. Moreover, the landscape was used as a soft medium to intervene in the control of the temple space. At the same time, under the control of imperial power, monks consciously constructed the sacred image of Jinshan Temple as sheltered by the highest secular power by creating or funding folk artworks.

The analysis of the transformation of Jinshan Temple’s spatial structure during the Southern Tours reveals that the Qing Court adopted a complex political strategy toward the Jiangnan religious forces at the time of tense conflicts between the Manchu and the Han in the early Qing Dynasty. Emperor Kangxi attempted to show his tolerance and support for Buddhism, taking moderate measures to co-opt monks in the Jiangnan region and to allay the public’s opposition to the Qing regime.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Y. and S.Z.; methodology, A.Y. and S.Z.; software, S.Z.; validation, A.Y. and S.Z.; formal analysis, A.Y. and S.Z.; investigation, S.Z.; resources, S.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Y. and S.Z.; writing—review and editing, A.Y. and S.Z.; visualization, S.Z.; supervision, A.Y.; project administration, A.Y.; funding acquisition, A.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [Shanghai Pujiang Program] grant number [2020PJC021].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The darker the orange color in the figure, the more concentrated the temples are in that area. |

| 2 | The upper portion of this painting is inscribed with the title Scenic Map of the Imperial Jinshan Jiangtian Temple, as well as Kangxi’s poem Jinshan Jiangtian Temple金山江天寺: I particularly like Jiangtian Temple. When I parked my boat and went up the mountain, I could hear the roar of the waves, see the lofts stacked up on top of each other, the warm sunlight reflecting on the trees, the breeze bringing the afternoon bells, and the river bank from a distance. The spring scenery was very beautiful. 独爱江天寺,停桡上碧峰。波澜声浩浩,楼阁势重重。日暖浮双树,风微送午钟。遥看南北岸,春色澹春容。 |

References

- Atsutoshi, Hamashima. 2008. Rural Society and Folk Belief in Jiangnan in Ming and Qing Dynasties 明清江南農村社會與民間信仰. Xiamen: Xiamen University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Michael G. 2007. A Court on Horseback. Imperial Touring and the Construction of Qing Rule, 1680–1785. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Degui 高得貴, and Lin Zhu 朱霖. 1685. Zhenjiang Fuzhi 鎮江府志 (Zhenjiang Prefecture Gazetteer).

- Gao, Fumin 高福民. 2014. Kangqian Shengshi “Suzhou Edition” Atlas 康乾盛世“蘇州版”圖錄冊. Shanghai: Shanghai Jinxiu Articles Publishing House, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- He, Feng 何峰. 2018. Research on Kangqian’s Southern Tours and Temporary Palaces in Jiangsu and Zhejiang Regions 康乾南巡與江浙地區行宮研究. Social Sciences 2: 154–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hearn, Maxwell Kessler. 1990. The “Kangxi Southern Inspection Tour”: A Narrative Program by Wang Hui. Princeton: Princeton University. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Li 李理. 2013. Research on the Collection of Paintings in Shenyang Palace Museum 瀋陽故宮博物院院藏繪畫研究. Beijing: Forbidden City Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Qingzhi 李清植. 2010. Wenzhengong Nianpu 文貞公年譜 (Chronicle of Wenzhengong). In Beijing Library Cang Zhenben Nianpu Congkan 北京圖書館藏珍本年譜叢刊. Edited by Beijing Library. Beijing: Beijing Library Press, vol. 85. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Jinzao 劉錦藻. 1988. Qingchao Xu Wenxian Tongkao 清朝續文獻通考 (General Study on Continued Literature of the Qing Dynasty). Hangzhou: Zhejiang Ancient Books Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Jianzeng 盧見曾. 1901. Jinshan Zhi 金山志 (Jinshan Gazetteer). Zhengjiang: Yayu Tang 雅雨堂, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Shengnan 馬勝楠. 2017. Study on Buddhist Temple-Based Temporary Palaces for Qianlong Southern Inspection Tour 乾隆朝南巡附寺行宮研究. Ph.D. dissertation, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Fong, Tobie. 2003. Building Culture in Early Qing Yangzhou. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Huitian 秦蕙田. 1880. Wu Li Tongkao 五禮通考 (General Study on the Five Rites). Suzhou: Jiangsu Shuju 江蘇書局, vol. 178. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Mingquan 釋明銓. 2021. Chijian Jinshan Jiangtiansi Xinzhi 敕建金山江天寺新志 (Imperial Jiangtian Temple Gazetteer). In Zhenjiang Wenku 鎮江文庫. Edited by Jinwen Xia 夏錦文. Yangzhou: Guangling Shushe, vol. 24. [Google Scholar]

- The First Historical Archives of China. 1985. Kangxi Chao Hanwen Zhupi Zouzhe Huibian 康熙朝漢文朱批奏摺彙編 (Kangxi Dynasty Chinese Memorials to the Throne Compilation). Beijing: China Archive Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tiezhou Xinghai 鐵舟行海. 2001. Jinshan Longyou Chansi Zhilue 金山龍遊禪寺志略 (Jinshan Longyou Temple Gazetteer). In Jinshan Longyou Chansi Zhilue Deng Sizhong 金山龍遊禪寺志略等四種. Edited by the Palace Museum. Yangzhou and Haikou: Hainan Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Tuo, Jin 托津, and et al. 1976. Da Qing Huidian Shili-Libu大清會典事例 (禮部) (Record of Laws and Systems of the Qing Dynasty-Department of Rites). Taiwan: Xin Wen Feng Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, Wange 翁萬戈. 2018. Read Wang Hui’s Painting of the Yangtze River in Laixiju 萊溪居讀王翬《長江萬里圖》. Shanghai: Shanghai Shuhua Publishing House, p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Han. 2020. Between the Secular and The Sacred: The Space-Time Construction and Humanistic Implication of the Map of Famous Mountains in National Map and Tibetan Map. Literature 3: 180–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Hung 巫鴻. 2018. Space in Art History “空間”的美術史. Shanghai: Shanghai People Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Shangding 徐尚定. 2014. Kangxi Qiju Zhu Biaodian Quanben 康熙起居注標點全本 (Complete Annotated Version of Record of Kangxi’s Daily Activities). Beijing: Oriental Press, p. 112. vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Sanga 伊桑阿, and et al. 1992. Kangxi Chao Da Qing Huidian-Libu 康熙朝大清會典(禮部) (Record of Laws and Systems of the Kangxi Reign in the Qing Dynasty—Department of Rites). In Historical Data Series of Modern China 近代中國史料叢刊. Edited by Yunlong Shen 沈雲龍. Taiwan: Wenhai Publishing House, vol. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Benyuan 于本源. 1999. Religious Policy in Qing Dynasty 清王朝的宗教政策. Beijing: China Social Sciences Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Lai 張萊. 1996. Jingkou Sanshan Zhi 京口三山志 (Jingkou Three Hills Gazetteer). In Sikuquanshu Cunmu Congshu-Shibu 四庫全書存目叢書(史部). Edited by Sikuquanshu Cunmu Congshu Bianzuan Weiyaunhui 四庫全書存目叢書編纂委員會. Jinan: Qilu Shushe, vol. 229. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Shiqing. 2000. Wushanshicha-tu and Zen Buddhist Temples of Jiangnan. Nanjing: Southeast University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).