Abstract

For a long time, scholarly research on Buddhism in Luoyang during the Tang Dynasty has mainly focused on eminent monks and Buddhist temples. This focus is evident in the recorded literature of ancient times, such as The Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks and The Biographies of Eminent Monks. Based on stone inscriptions, this paper examines the dissemination and development of Buddhism in the Eastern Capital of Luoyang during the Tang Dynasty. This article presents the following viewpoints and findings: Firstly, the epitaphs and pagoda inscriptions provide historical details that are not widely known, such as the names of temples in the suburb, the identities of prominent monks who propagated Dharma in Luoyang, the Buddhist scriptures chanted and learned by the Luoyang people, and the people’s motivation to adopt Buddhism. Secondly, the epitaphs and pagoda inscriptions supplement important historical materials on Chan Buddhism, confirming the widespread popularity of the Northern Sect of Chan Buddhism in the Luoyang region. Thirdly, the epitaphs and pagoda inscriptions reveal that Luoyang Buddhist practice was popular, characterized by the succession of blood-related monastic companions; that is, many families had two or more relatives who became monks or nuns simultaneously or successively, a phenomenon that has not attracted attention from academic circles. Fourthly, the blood-related monastic companions of Buddhist practice affected the mentoring relationships and organizational management of temples and monasteries, promoting communication and interaction between Buddhism and traditional Chinese culture.

1. Introduction

Luoyang was one of the hubs of ancient Chinese Buddhism and held an important position with significant influence in the history of Buddhism. Buddhism was introduced to China during the Han 漢 Dynasty (202 BC–220 AD), and Luoyang, stationed in the Central Plains, was its first stop. The White Horse Temple, known as “Shiyuan” 釋源 (the origin of Chinese Buddhism) and “Zuting” 祖庭 (the Ancestral Buddhist Temple), was built in Luoyang, which is also the main site of the Buddhist transmission by early eminent monks from Western regions to China. Luoyang qielanji 洛陽伽藍記 (The Record of Buddhist Temples and Monasteries in Luoyang) records the rise and fall of Buddhist temples and monasteries, narrating amusing anecdotes from Luoyang during the Northern Wei 北魏 Dynasty (386–534). As one of the political, economic, and cultural centers, Luoyang served as the Eastern Capital of the Tang Dynasty (618–907) and the “Shendou” 神都 (the Divine Capital) of the Wuzhou 武周 Dynasty (690–705). The Longmen Grottoes 龍門石窟 are the largest treasure trove of stone carving art, with the most Buddhist statues in the world. However, insufficient archaeological materials and related documentation may mean that the attention given by scholars to Luoyang Buddhism in the Tang Dynasty did not do justice to its historical significance and international influence within Buddhism.

To date, academic research on Buddhism in Luoyang during the Tang Dynasty has focused on Buddhist buildings and prominent monks within the city proper. This research has yielded valuable insights, particularly on the history of eminent monks and famous temples and monasteries. For instance, archaeologists have discovered the location and name of Buddhist temples where early Western Regions monk transmitted Buddhism to China, and scholars have also studied the building time and renovation processes of the Dafuxian Temple 大福先寺 (Xin 2006, p. 153; Wen 1996, pp. 328–32, etc.) as well as the activities of eminent monks seen in nine newly unearthed stone inscriptions in the Luoyang area (Zhang 2008, vol. 5, p. 90). However, the utilization of stone inscriptions that can truly demonstrate the dissemination and evolution of Buddhism in Luoyang is not sufficient, and there is relatively scant research on the material culture of Buddhism, especially as it relates to laity and to monastics who were not influential enough to be included in The Biographies of Eminent Monks. One representative study is Hou Xudong’s Wu, liu shiji beifang minzhong fojiao xinyang -yi zaoxiangji wei zhognxin de kaocha 五,六世紀北方民眾佛教信仰——以造像記為中心的考察 (Buddhist Beliefs of the Northern People in the Fifth and Sixth Century—An Investigation Centered on Inscriptions on Buddhist Statue). The representative study used a database of 1600 inscriptions on Buddhist statues to investigate the impact of Buddhism on the thoughts and behaviors of the people in the fifth and sixth centuries (Hou 2015, pp. 102–326). Although the study covered a historical period spanning from the Southern and Northern Dynasties (420–589) to the Sui Dynasty (581–618), it provides valuable references for studying the popular Buddhist beliefs in Luoyang during the Tang Dynasty.

Professor Zürcher, a renowned Sinologist, said that “Although we have almost no knowledge of the relationship between the Luoyang monastic Sangha and its surrounding environment, it is obvious that temples are not an isolated enclave of foreign cultures. Because of inadequate materials, we cannot discuss their social background” (Zürcher 2003, p. 39). Professor Zürcher’s statement regarding the current status of Buddhist research in Luoyang during the early Middle Ages can also apply to that during the Tang Dynasty from the sixth to eighth centuries. Although the academic community has been involved in the study of regional Buddhism in Luoyang during the Middle Ages, there are still many research gaps. Fortunately, since the beginning of the twentieth century, the total number of newly unearthed epitaphs has exceeded 10,000, with over 70% of them found in Luoyang. Stone inscriptions, which are handwritten materials, contain little-known life details of Luoyang Buddhists and provide valuable historical information concerning the dissemination of Buddhism during the Tang Dynasty, helping to recreate the scenes of popular Buddhist life and filling some gaps in the history of Buddhism. The local history engraved on the stones, like a mirror, reflects the scene of the spread and prosperity of Buddhism and presents the specific details of Buddhist practice in Luoyang.

Based on the underutilized stone inscriptions, this article explores the dissemination and acceptance of Buddhism in Luoyang during the Tang Dynasty, delving into aspects such as where monks or nuns resided and practiced in the suburbs, which monks or nuns propagated Dharma, what kind of Buddhist scriptures spread outside of temples and monasteries, and the dynamic that motivated people to convert to Buddhism. Furthermore, this paper discusses the phenomenon and social influence of the blood-related monastic companions of Buddhist practice in Luoyang, an area that has received limited attention in previous studies. The stone inscriptions discussed in this research include pagoda inscriptions of monks and nuns, epitaphs of lay Buddhists, and inscriptions on Buddhist statues. These stone inscriptions were mainly found in Luoyang and can be seen now in stone inscription books, academic journals, public museums, and in our private collections.

2. Temples and Monasteries in the Outskirts of Luoyang City

Buddhist buildings, including large temples and small monasteries, were common cultural landscapes in Luoyang. Regarding the names and locations of Buddhist temples within the city proper, there is significant research that has unearthed detailed documents passed down from ancient times. According to the available literature, it is known that about one-third of the Fang 坊 (small, borough-like district with surrounding walls in ancient Chinese cities) in the Eastern Capital city had temples and monasteries built. For example, the Linzhi Temple 麟趾寺 was located in Xingyi Fang 興藝坊 near Shangdongmen (上東門), close to the eastern area of the city (Xu 2013, vol. 5, p. 177); the Zhaocheng Temple 昭成寺 was located in Daoguang Fang 道光坊 on the right side of the eastern area (Xu 2013, vol. 5, p. 172); the Huayan Temple 華嚴寺 was located in Jingxing Fang 景行坊 in the northern area (Wang 1955, vol. 48, p. 849); the Anguo Temple 安國寺 was located in Xuanfeng Fang 宣風坊 in the southern area (Xu 2013, vol. 5, p. 168); and the Chonghua Temple 崇化寺 was located in Jingshan Fang 旌善坊 in the southern area (Xu 2013, vol. 5, p. 150).

Eminent monks from Luoyang, such as Xuanzang 玄奘, Daoyue 道岳, Zhixing 智興, Zhiman 志滿, Tanrun 曇潤, and Yihui 義輝, as well as those from abroad such as Vajrabodhi 金剛智, Śubhakarasiṃha 善無畏, and Bukong 不空, all used to practice Buddhism, giving sermons, expounding Buddhist doctrines, and holding Buddhist lectures in Luoyang. In addition to the Buddhist temples distributed within the city, there were other important Buddhist temples in the suburbs. The stone inscriptions provide clues to the locations of the suburban temples in which monks or nuns resided and practiced Buddhism.

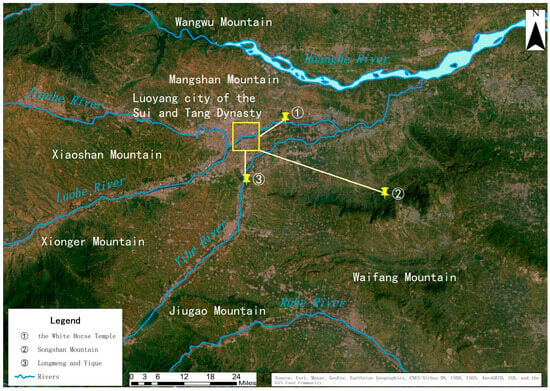

The first area is the White Horse Temple, located in the east of Waiguo City 外郭城 during the Sui and Tang Dynasties and near Luoyang City 漢魏洛陽故城 during the Han and Wei Dynasties (Figure 1). According to The Record of Buddhist Temples and Monasteries in Luoyang, the White Horse Temple, the first temple built after Buddhism was introduced to China, was erected during the reign of Emperor Ming 明帝 (57–75) of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220). The Pagoda Inscription of Zhang Zhen 張貞塔銘, engraved in the 26th year of the Kaiyuan 開元 era (738), records that Zhang became a monk at the White Horse Temple (Zhou 1992, pp. 1480–81). The Pagoda Inscription of Yuanjing 圓敬塔銘, engraved in the 18th year of the Zhenyuan 貞元 era (792) and written by Prime Minister Quan Deyu 權德輿, records that Yuanjing practiced at the White Horse Temple (Li 1966, vol. 785, p. 4151). The above-mentioned stone inscriptions show that the White Horse Temple was still the main suburban residence of monks in Luoyang during the Tang Dynasty.

Figure 1.

Suburban Luoyang temple locations.

The second area is Mt. Songshan in the southeast of the Luoyang region (Figure 1). Mt. Songshan is also known as Mt. Songgao 嵩高 or Mt. Zhongyue 中嶽 (one of the well-known Five Mountains in the middle of China). Sima Qian 司馬遷 (145 BC-?) of the Han Dynasty once said that “In the past, the capital cities of Xia 夏, Shang 商 and Zhou 周 Dynasties were all located in the area between the Huanghe River and the Luohe River, so Mt. Songgao was named Mt. Zhongyue, and the other four well-known Mountains 四嶽 were just like the leaders of the four directions of east, west, south, and north, with Sidu 四瀆 (the four important rivers named Changjiang River, Huanghe River, Huaihe River, and Jishui River) in the east of Mt. Xiaoshan 崤山. 昔三代之君, 皆在河、洛之間, 故嵩高為中嶽, 而四嶽各如其方, 四瀆咸在山東” (Sima 1959, vol. 28, p. 1371). The most famous temple in Mt. Songshan is the Shaolin Temple 少林寺, known as the Ancestral Buddhist Temple of Chan Buddhism. It was built during the reign of Emperor Xiaowen 孝文帝 (471–499) of the Northern Wei Dynasty. The temple was destroyed during Jiande’s 建德 era (572–578) by Emperor Wu 武帝 of the Northern Zhou Dynasty 北周 (557–581) and soon rebuilt during the era of Daxiang 大象 (579–580) under Emperor Jing 靜帝. In the fourth year of the Wude 武德 era (621), Li Shimin 李世民, the King of Qin, known as Tang Taizong 唐太宗, the second emperor of Tang, personally wrote a letter titled “Qinwang gao shaolinsi zhujiao” 秦王告少林寺主教 (A Letter from the King of Qin to the Buddhist Abbot of the Shaolin Temple). This letter was later inscribed on a pillar erected in front of the temple. The Pagoda Inscription of Lingyun 靈運塔銘, engraved in ninth year of the Tianbao 天寶 era (750), records that Lingyun became a monk at the Shaolin Temple in Mt. Songshan (Zhou 1992, p. 1642).

At the foot of Jicui Peak 積翠峰 in the south of Mt. Taishi 太室山 in the Mt. Songshan range, the Huishan Temple 會善寺 was located 15 miles east of the Shaolin Temple. According to The Stele Inscription of Huishan Temple 會善寺碑, written by Wangzhu 王著 of the Song 宋 Dynasty (960–1279), this temple was originally the summer palace of Emperor Xiaowen of the Northern Wei Dynasty and later became a temple where the famous monk Chengjue 澄覺 practiced. During the Kaihuang 開皇 (581–600) era of the Sui Dynasty, it was named the Huishan Temple by Emperor Wen 文帝 (581–604) (Chang 2008, vol. 9, p. 462).

The Pagoda Inscription of Jingxian 景賢塔記, written by Monk Wengu 温古 during the Tang Dynasty, records that Jingxian passed away at the Huishan Temple. This record can also be seen in other stone inscriptions, such as The Epitaph of Song Sigu 宋思谷墓誌, engraved in the second year of the Kaiyuan era (714), with the cover inscription written by the monk of Mt. Taishi (Chen 1991, vol. 8, p. 187), and The Pagoda inscription of Jingzang 淨藏塔銘, with information about Jingzang’s residence near the western pagoda of the Huishan Temple, engraved in the fifteenth year of Tianbao’s era (746) (Chen 1991, vol. 11, p. 78). Together with the Buddhist temples, seen in the local chronicles during the Ming and Qing Dynasties, such as the Fawang Temple 法王寺, the Yongtai Temple 永泰寺, the Zhongyue Temple 中嶽寺, the Songyue Temple 嵩岳寺, the Longtan Temple 龍潭寺, the Luya Temple 盧崖寺, the Beilou Temple 碑樓寺, the Tianzhong Temple 天中寺, the Longquan Temple 龍泉寺, the Zhulin Temple 竹林寺, the Yuquan Temple 玉泉寺, the Hualin Temple 華林寺, and the Xiangyu Temple 香峪寺 (Huang 2016, pp. 12–22), there were at least fifteen temples located in the Mt. Songshan area during the Tang Dynasty.

The third area is Yique Longmen 伊闕龍門 in the south of Waiguo City during the Sui and Tang Dynasties (Figure 1). The stone inscriptions of the Tang Dynasty record that there were at least thirteen Buddhist temples located around Mt. Longmen, including the Wanshou Temple 萬壽寺, the Tianzhu Temple 天竺寺, the Fengxian Temple 奉先寺, the Jingshan Temple 敬善寺, the Guanghua Temple 廣化寺, the Baoying Temple 寶應寺, the Bodhi Temple 菩提寺, the Xiangshan Temple 香山寺, the Qianyuan Temple 乾元寺, the Yique Temple 伊闕寺, the Hufa Temple 護法寺, the Yuanxian Temple 元憲寺 (Figure 2), and the Hongsheng Temple 弘聖寺 (Table 1). This area was also an ideal burial place for monks and nuns in the Eastern Capital. For example, Shenhui 神會of the Heze Temple 荷澤寺, the monk Yan of the Tiangong Temple 天宮寺, the nuns Baoen 報恩 and Bianzhao 遍照 of the Xiuxing Temple 修行寺, and Wuyin 悟因, Huiyin 惠隱, and Dazhi 大智 of the Anguo Temple 安國寺 were all buried in Longmen (Song 2022, August 25).

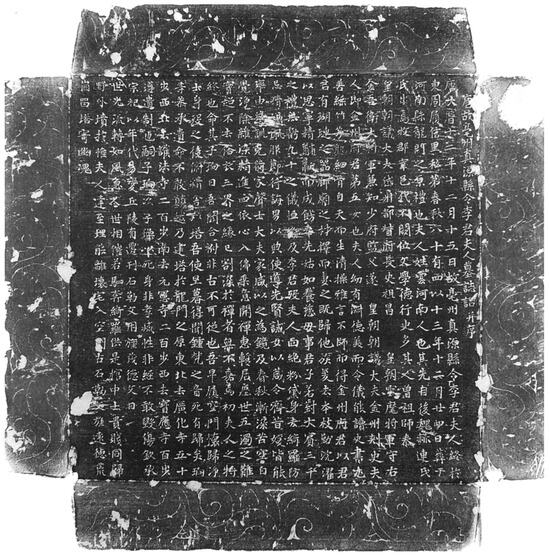

Figure 2.

The Epitaph of Mr. Li’s Wife Yun 李君妻雲氏墓誌, engraved in the 13th year of the Dali 大曆 era (778), unearthed in Luoyang.

Table 1.

Buddhist temples in the Longmen area.

The three aforementioned suburban Buddhist temples and monasteries were mainly located in areas of the ancient city in the east during the Han and Wei Dynasties (Mt. Songshan in the southeast and Longmen in the south) and were mostly built in well-known mountains or alongside prominent rivers during the Han and Wei Dynasties. These temples and monasteries complemented the Buddhist temples in the Luoyang region, creating a thriving environment of Buddhist buildings inside and outside the city. Today, it can be seen that there were at least seventy-one Buddhist temples in and around Luoyang city, with twenty-nine in the suburbs and forty-two in the city (Yang 2020, pp. 60–66), reflecting the characteristic of widespread placement and high density of Buddhist buildings in Luoyang during the Tang Dynasty.

3. The Wide Influence of Northern Chan Buddhism in Luoyang

The Tang Dynasty reigned for 290 years and had twenty emperors. Almost all these emperors tended to support the development of Buddhism through a series of measures such as building a large number of official temples and Buddhist statues, opening Buddhist caves, setting up scripture translation centers, and cultivating Buddhist talents throughout the country. In the second year of Wude’s 武德 era (619), Emperor Gaozu 高祖 (618–626) called eminent monks together in the capital and established the Ten Head Monks 十大德 to manage ordinary monks and nuns. Emperor Taizong 太宗 (626–649) supported Buddhism, while Emperor Gaozong 高宗 (649–683), Emperor Zhongzong 中宗 (684, 705–710), and Emperor Ruizong 睿宗 (684–690) believed in Buddhism. After Empress Wu Zetian’s accession to the Central Palace, Buddhism gained extensive support and reached its peak, and some important local Buddhism sects that adapted to China’s national conditions, such as the Tiantai Sect 天臺宗, Chengshi Sect 成實宗, Sanlun Sect 三論宗, FaxingSect 法相宗, Lv Sect 律宗, Huayan Sect 華嚴宗, Pure Land Sect 淨土宗, Jushe Sect 俱舍宗, and Chan Sect 禪宗, gathered in Luoyang to promote their own teachings. Northern Chan Buddhism was the most popular localized form of Buddhism in Luoyang, and its founder, Shen Xiu 神秀 (606–706), was highly respected by Empress Wu Zetian. Even at the age of 90, he was invited to Luoyang and received offerings from Wu in a solemn and grand ceremony that is described in some ancient works such as The Biographies of Eminent Monks in the Song Dynasty: “Shen Xiu was carried up to the Central Palace with a sedan chair usually used by an emperor, and Wu Zetian knelt down to welcome him in person (神秀) 肩輿上殿, (武則天) 親加跪禮” (Zan 1987, vol. 8, p. 177). Empress Wu was interested in Chan and invited at least eight Chan masters to the court (Weinstein 2010, p. 46).

Shen Xiu’s disciples Puji 普寂 and Yifu 義福 continued to propagate Dharma in the two capital regions, earning profound respect from the court and the public. The disciples’ preaching gained the faith and support of the supreme ruler, and they also garnered a large number of followers among the literati and aristocratic class (Yang 1999, pp. 106–8). Stone inscriptions from the Kaiyuan to Tianbao eras contain authentic and vivid records of the Northern Chan Buddhism monk Puji, also known as Dazhao 大照, propagating Dharma in Luoyang, as can be read in the following quotes.

The Epitaph of Mr. Li’s Wife Yan 李君妻嚴氏墓誌 states: “Madam deeply understood karma and retribution, and wanted to seek liberation. When suddenly experienced meditative equanimity, she knew that everything in the world was like dreams and bubbles and practicing Buddhism could alleviate all troubles, thus, the Monk Dazhao performed a head-touching ritual, giving her a Buddhist name Zhenruhai 夫人深悟因緣, 將求解脫, 頓味禪寂, 克知泡幻。數年間能滅一切煩惱, 故大照和上摩頂受記, 號真如海” (Chen 1991, vol. 10, p. 203).

The Epitaph of Murong Xiang and his Wife Tang 慕容相及妻唐氏墓誌 states: “After practicing Buddhism, Madam was happy about Dharma and looked for Master Dazhao to learn the essence of Buddhism 坐菩提之樹, 遊灋喜之園。因觀大照禪師, 求了義也” (Chen 1991, vol. 11, p. 17).

The Epitaph of Wei Xiaohai 韋小孩墓誌 states: “After her husband’s death, the wife was deeply shaken and emotionally depressed, often crying during the day. When the mourning period ended, she converted to Buddhism and once relied on Master Dazhao to learn Buddha dharma, taking any easy and quick ways to practice Buddhism 逮府君冥寞朝露, 而夫人低徊晝哭, 服喪之後, 禪悅爲心。嘗依止大照禪師, 廣通方便” (Zhou 1992, p. 1647).

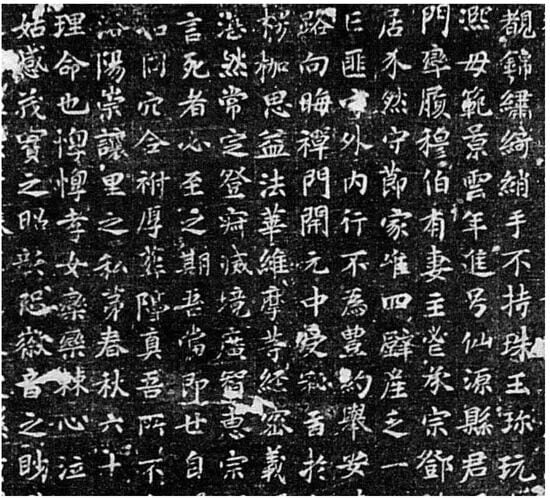

The Epitaph of ZhengChong 鄭沖墓誌 states (Figure 3): “During the Kaiyuan and Tianbao eras, she successively studied profound and subtle Buddhist teachings from Master Dazhao and Master Hongzheng 開元中, 受秘旨於大照宗師;天實際, 證微言於弘正法主” (Zhongguo Institute of Cultural Relics 2008, p. 167).

Figure 3.

Part of the rubbings of The Epitaph of ZhengChong 鄭沖墓誌, engraved in the tenth year of the Tianbao 天寶 era (751), unearthed in Luoyang.

The Epitaph of Cui Zangzhi 崔藏之墓誌 states: “He knew that everything in the self was just in a dream, and all dharmas were empty. He visited Master Dazhao and respectfully consulted Master about Buddhism 知身是幻, 見法皆空。因詣大照禪師, 摳衣請益” (Zhongguo Institute of Cultural Relics 2008, p. 127).

The above epitaphs provide valuable records of lay Buddhist life in Luoyang, containing many precious historical facts and details about the popularity of Northern Chan Buddhism that Northern Chan Buddhism had a wide and deep social impact in Luoyang, where Chan seemed to have become a part of secular life instead of just a religion, subtly integrating into the daily lives of citizens, attracting countless people to explore their own inner selves, and providing a unique key for people to comfort their hearts and understand suffering that is rarely seen in the recorded historical literature. There are many records in the stone inscriptions about Master Dazhao’s preaching that mention followers such as Mr. Li’s wife Yan of Guiyi Fang 歸義坊, Madame Tang of Huijie Fang 會節坊, Madame Wei of Lushun Fang 履順坊, Madame Zheng of Chongrang Li 崇讓里, and official Cui Zangzhi 崔藏之, who learned Buddhism from Master Dazhao in different ways. “Master Dazhao” is the posthumous title for Shenxiu’s disciple Puji (?–739), and his family name in the secular world was Feng. He was from Changle Xindu 長樂信都 (now Jizhou, Hebei) and began to learn Buddhism in his childhood and later followed Shenxiu (606–706), the founder of Northern Zen Buddhism, to practice in the Yuquan Temple in Jingzhou. During the Shenlong 神龍 era (706), Shenxiu passed away, and Emperor Zhongzong issued an edict ordering Puji to inherit Shenxiu’s career and “lead the disciples and publicize the teachings 統領徒眾, 宣揚教跡” (Dong 1983, vol. 262, pp. 2657–61). The inscription mentions that Madame Zheng first followed Puji during the Kaiyuan era and then learned Buddhist Dharma from Master Hongzheng 弘正 during the Tianbao era. Hongzheng, in that inscription, was also a monk of Northern Chan Buddhism and he inherited Puji’s Buddhist career (Dong 1983, vol. 390, p. 3973). In the thirteenth year of the Kaiyuan era (735), Puji was ordered to reside in the Jing’ai Temple 敬愛寺, and in the fifteenth year, he was ordered by Emperor Xuanzong to stay at the Xingtang Temple 興唐寺 in Luoyang, where he passed away in the twenty-seventh year of the Kaiyuan era (739) (Dong 1983, vol. 262, pp. 2657–61). Therefore, Madame Zheng continued to follow Hongzheng, Puji’s disciple, in order to practice Buddhism.

The epitaphs unearthed in Luoyang also mention Tantra and Śubhakarasiṃha 善無畏, as can be read in the following texts.

The Epitaph of Long Tingwei 龍庭瑋墓誌 states: “Long was joyful upon hearing that in Buddhism there is the secret teaching of non-production, so he gave up his official position and went south to Mt. Songshan to meet with Monk Dazhao, and obtained the Esoteric doctrines and secret techniques of practice 聞釋氏有無生密教, 而心悅之。乃不之官, 南見嵩丘大照和尚, 得心地秘法” (Zhao and Zhao 2007, p. 332).

The Epitaph of Peng Shao and his Wife Xu 彭紹及妻徐氏墓誌 states: “After her husband Peng passed away, Madame Xu made up her mind to pursue the essence of Buddhism. She learned the Esoteric meaning of Buddhist scriptures from Master Śubhakarasiṃha 三藏法師 and Bodhisattva practice from Master Dazhao, day and night without slacking off 自公云逝, 志求寶相。於無畏三藏受文字義, 於大照禪師學菩薩行, 不捨晝夜, 而常修習” (Zhao 2004, p. 189).

The above epitaphs, engraved in the first year of the Tianbao era (742), mention that Long Tingwei, the magistrate of Huachi County 華池縣令, heard of the teachings of Esoteric Buddhism before following Puji’s teaching. Madame Xu, who lived in Kangshu Fang 康俗坊, studied Buddhism under Śubhakarasiṃha before following Puji’s practice. Śubhakarasiṃha 善無畏 (637–735) was one of the Three Great Masters 三大士 of the Kaiyuan era and one of the founders of the Chinese Tantric Sect. He accompanied Emperor Xuanzong (712–756) to Luoyang in the twelfth year of the Kaiyuan era (724) and translated several important classics of the Tantric Sect (Xiao 2014, p. 107). In the twenty-eighth year of the Kaiyuan era (740), Śubhakarasiṃha passed away and was buried at the Guanghua Temple 廣化寺 in Longmen West Mountain (Zan 1987, vol. 2, pp. 17–22).

Both Tantra and Chan belong to the eight major sects of local Chinese Buddhism, and these two are closely related. The unearthed epitaphs in Luoyang provide evidence of not only the fact that the Northern Chan Sect and its closely related Tantric Sect were widely popular among the people but also of the Tang Dynasty’s national policy of free religious belief, the coexistence of multiple religions, and the absence of barriers between sects. The people could choose their beliefs at any time. As shown in the previous text, Śubhakarasiṃha of the Tantric Sect taught the Esoteric meaning of Buddhist scriptures, and Puji of the Northern Chan Sect taught Bodhisattva practice, seemingly fulfilling their respective duties of clear division of labor.

Shenxiu’s Chan ideology, representing the Northern Chan Sect, holds an important place in the history of Chinese Buddhism. However, as the historical materials of Chan are mostly based on the Southern Sect, the materials about the Northern Chan Sect are relatively scarce. Stone inscriptions provide an accurate record of the good reputation and influence of the Puji sect of the Northern Chan in the Eastern Capital during the Kaiyuan and Tianbao periods as well as the historical fact that the Northern Chan Sect became popular in Luoyang. Thus, the literature found in stone inscriptions is an important supplement to the existing historical materials on Chan.

4. Buddhist Scriptures Circulated in the Luoyang Region

Since the time of the Han Dynasty, a large number of Buddhist classics have been translated by leading monks. The records of learning, exposition, and dissemination of Buddhist scriptures are mainly found in The Biographies of Eminent Monks of successive dynasties, such as The Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks and The Biographies of Eminent Monks in the Song Dynasty, which record that in the early Tang Dynasty, Fazang 法藏 preached Avataṃsaka-sūtra 華嚴經, and Daoyin 道氤 expounded Jing yezhangjing 淨業障經 (Buddhist Sutra for Eliminating Karmavarana), Yoga-sūtra 瑜伽經, Vijñāptimātratāsiddhi 維識, Hetuvidyā 因明, and Pañca-saptati 百法明門論 (the 100 dharmas) (Li 2004, p. 162). In the later Tang Dynasty, Lingyin 令諲 expounded the Amitâbha-sūtra 阿彌陀經 and Mādhyamika-śāstra 中觀論 (Li 2004, p. 177). These conclusions are drawn through the recorded literature from the perspective of monks who promoted Dharma. However, the stone inscriptions document the types of Buddhist scriptures studied and chanted in the Eastern Capital from the perspective of practice and acceptance.

The epitaphs concerned were engraved during the period from the third year of the Shengli 聖曆 era (700) to the twelfth year of the Tianbao era (753), marking the heyday of the Tang Dynasty. These stone inscriptions mention that the Buddhist scriptures chanted or learned by the Luoyang people mainly include Nirvāṇa-sūtra 涅槃經, Vajracchedikā-prajñāpāramitā 金剛般若, Vimalakīrtinirdeśa sutra 維摩詰經, The Lotus Sutra 妙法蓮華經, Avataṃsaka-sūtra 華嚴經, Laṅkâvatāra-sūtra 楞伽經, and Viśeṣa-cinti-brahma-paripṛcchā-sūtra 思益經. During the same period, temple monks mainly preached Avataṃsaka-sūtra 華嚴經, Jingyezhang jing 淨業障經 (Buddhist Sutra for Eliminating karmâvaraṇa), Yoga-sūtra 瑜伽經, Vijñāptimātratāsiddhi 維識, Hetuvidyā 因明, and Pañca-saptati 百法 (Table 2). There is a significant difference in the content of the Buddhist scriptures promoted and elucidated by temple monks and in the types and focus of the Buddhist scriptures chanted and practiced among the people of Luoyang. In the literature available today, Vishechachinta Brahma Pariprichcha is rarely seen—either in The Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks or in The Biographies of Eminent Monks in the Song Dynasty. However, stone inscriptions record that Viśeṣa-cinti-brahma-paripṛcchā-sūtra was an important scripture chanted or read in Luoyang Buddhist families. Viśeṣa-cinti-brahma-paripṛcchā-sūtra, an important classic work of the Mahayana Bodhisattva sect in Buddhism, with three main translations passed down from ancient times, is also an important classic preached by the monks of the Shenxiu faction of the Northern Chan Sect. The Pagoda Inscription of Dazhao 大照禪師塔銘 states that Shen Xiu once instructed his disciple Puji to “read Viśeṣa-cinti-brahma-paripṛcchā-sūtra first and then Laṅkâvatāra-sūtra 看《思益》, 次《楞伽》” (Dong 1983, vol. 262, p. 1174). In short, the stone inscriptions record the circulation of these Buddhist scriptures in Luoyang from a unique perspective, making up for some of the gaps in the bibliographic records of Buddhist scriptures circulating in the Luoyang region in the recorded literature such as The Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks and The Biographies of Eminent Monks in the Song Dynasty.

Table 2.

List of Buddhist scriptures chanted or read in Buddhist families.

5. Ascribed Background Prior to Receiving Ordination

During the Tang Dynasty, the residents of Luoyang were enthusiastic about embracing Buddhism. This enthusiasm is related to the historical status of Luoyang as “the origin of Chinese Buddhism”, its political status as one of the administrative centers, and also the geographical conditions such as convenient water and land transportation and abundant resources. The enthusiasm is also related to the personal efforts of Empress Wu Zetian to promote the development of Buddhism as well as the large number of Buddhist temples located in the residential districts and the effectual dissemination of Buddhism by the above-mentioned monks such as Xuanzang and Daoyue and the well-known temples. Luoyang was also a core area for the development of Buddhism, and Buddhist worship was prevalent. Furthermore, the people there, ranging from nobles to commoners, all tended to show their respect for Buddha in various ways. Although the recorded literature such as The Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks and The Biographies of Eminent Monks records the life experiences of some monks engaged in propagating Buddhism, there are very few records regarding the different ascribed backgrounds of the people for receiving ordination. However, the stone inscriptions provide detailed records of why and how the Luoyang people adopted Buddhism, and those Buddhists can be divided into three groups as follows.

The first group is those who were said to have been born with knowledge about the practice of Buddhism 生而知之 (Table 3). Some pagoda inscriptions describe that this group of people aspired to practice Buddhism from a very young age and genuinely sought and yearned for the teachings of Buddhism, and they can be said to be enlightened and wise individuals who “came due to the Mahayana vow 乘願而來.” The pagoda inscriptions provide a detailed account of how such individuals began their Buddhist career. For example, Huiyin 惠隱 admired Buddhism from childhood (Metal and Stone Group of Beijing Library 1989, vol. 24, p. 55). Master Shiyan 石岩 had an early knowledge of Buddhism, setting him apart from ordinary people (Zhang 2008, vol. 5, p. 89). Master Da Zheng 大證 of the Jing’ai Temple had deep insights into Buddhism as a child (Dong 1983, vol. 370, p. 3758). Master Tongguang 同光 of the Shaolin Temple was born with a Buddhist nature (Metal and Stone Group of Beijing Library 1989, vol. 27, p. 103). Chengkong 澄空 of the Anguo Temple had a Buddha-like nature since childhood, and she could consciously “act like a Bhiksuni and received precepts 持心受戒” before undergoing tonsure to be a nun (Metal and Stone Group of Beijing Library 1989, vol. 28, p. 101). The famous nun Wei 韋和尚, the abbess of the Anguo Temple, had a great desire to promote the Dharma during her childhood (Zhou 1992, p. 1836). The motivation of these Buddhists was said to grow in their childhood, and they began to formally learn Buddhism as teenagers and then became monks or nuns in their youth. They believed that Buddhism represented supreme wisdom and that practicing it was the great holy path, with their mission to begin the promotion of Buddhism.

Table 3.

Examples of those who were said to have been born with a knowledge of the practice of Buddhism.

The second group is those who adopted Buddhism through learning 學而知之 (Table 4). This group systematically learned the classics of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism and then chose to leave Confucianism and become Buddhists, even after passing the imperial examination and becoming officials. This group reflects a manifestation of the vigorous development of Buddhist culture. For example, Zhang Luo 張洛, a recluse in Luoyang, eventually converted to Buddhism, specifically Mahayana Buddhism, after systematically learning the classics of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism (Metal and Stone Group of Beijing Library 1989, p. 1156). Liu De 劉德 studied Confucian classics in his early years and began practicing Buddhism at the age of fifty after abandoning Confucianism (Chen 1991, vol. 6, p. 165). Master Dazhi 大智 initially followed the Daoist Huang-Lao School and Confucianism, but, because he could not find a way to be saved, he stopped advancing, and at the age of thirty, he became a monk (Metal and Stone Group of Beijing Library 1989, vol. 24, p. 12). At the age of twenty, Monk Zhen 貞和尚 passed the imperial examination and became famous in the capital, but later, he abandoned his official career in order to practice Buddhism (Zhou 1992, p. 1480). During the Tianbao era (742–756), Master Mingyan 明演 took the imperial examination and served as the Wei of Linpu County 臨濮縣尉 and the assistant magistrate of Puyang County 濮陽縣丞 during the Baoying era (762–763). However, he suddenly felt that everything was empty, so he resigned and devoted himself to the worship of Buddha (Metal and Stone Group of Beijing Library 1989, vol. 28, p. 162). Most Buddhists of this type had considerable cultural cultivation, noble aspirations, commendable conduct, good material living conditions, talent, and virtue but were unwilling to become officials or even gave up official careers, devoting themselves to meditation and Chan studies because they were obsessed with exploring the mysteries of Buddhism. These Buddhists delved deeply into Chan studies and converted to Buddhism to fulfill their spiritual demands.

Table 4.

Examples of those who converted to Buddhism through learning.

The third group includes those who turned to Buddhism when facing hardships in life 困而知之 such as personal setbacks or the loss of a loved one (Table 5). As a result, they embraced Buddhism to find spiritual support or chose to worship Buddha to receive blessings. For example, Madame Wang of Yiren Li 依仁里 chose to become a nun after her husband’s death (Zhou 1992, p. 1497). Lai Xiang’er 來香兒 of Shiyong Fang 時邕坊 adopted Buddhism after the death of her family member (Chen 1991, vol. 11, p. 88). After the death of her husband, Madame Liu lived in a widowed and depressed state and later went to the Shengshan Temple to become a nun (Zhao 2009, p. 594). Madame Wei of Kangsu Fang 康俗坊 embraced Buddhism after her relatives passed away one after another (Chen 1991, vol. 12, p. 165). Madame Wang of Jianchun Fang 建春坊 adopted the worship of Buddha due to her widowed and lonely life (Chen 1991, vol. 12, p. 105). Madame Zhu of Yude Fang 毓德坊 converted to Buddhism due to her husband’s death, and her belief in Buddhism brought happiness to her mind (Chen 1991, vol. 8, p. 70). Accordingly, women were the main members of this group. What the stone inscriptions reveal is that people were motivated to adopt Buddhism not from innate religious emotions or from an interest in Buddhist philosophy but from pragmatism; that is, they regarded practicing Buddhism as an effective way to address life’s difficulties and alleviate emotional distress, and they opted for it even though it meant choosing a life of chastity. In their minds, Buddha or Bodhisattva were not holy, religious idols, but a kind of spirit for relieving difficulties and blessing Buddhists. Therefore, they became vegetarians, chanted scriptures daily, held precepts, practiced self-discipline and Buddhism, and showed reverence for Buddha and Bodhisattva. Through the process of “conversion”, one gradually or suddenly transformed a divided, self-despising, or unhappy self into a unified, superior, and happy self (James 2009, p. 189).

Table 5.

Examples of those who began to practice Buddhism after facing hardships.

6. Worship of Buddha by Blood-Related Monastic Companions in Luoyang

The Tang Dynasty, which reigned over a long period characterized by national unity, social stability, and a prosperous economy, promoted the vigorous development of culture and religious beliefs. Despite the dynasty’s cultural policy of the coexistence of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism, Buddhism had a wide and profound influence. By the time of the reign of Emperor Xuanzong, there were already 5358 Buddhist temples and monasteries in the country (Li 2014, vol. 4, p. 125). Buddhism was highly popular in Luoyang, the Eastern Capital. As a result, the social concept of “practicing Buddhism is considered high 修佛以為高” emerged. This concept meant that becoming a monk or a nun and practicing Buddhism were viewed as an individual and family achievement accorded the same honor as becoming an official through the imperial examination. There were two ways that this concept was expressed.

One way was recording the personal information of the monastic children in detail, such as the Dharma names, titles, and the names of temples where they resided and practiced, to praise the deceased in epitaphs. For example, The Epitaph of Wang Ping 王平墓誌, engraved in the sixteenth year of the Zhenyuan era (800), says that Wang lived in Xuanjiao Fang 宣教坊 of the Eastern Capital, and his daughter, under the Dharma name Mingwu 明悟, became a nun at the Xiuxing Temple 修行寺 (Chen 1991, vol. 12, p. 156). Moreover, The Epitaph of Li Jinrong 李進榮墓誌, engraved in the seventeenth year of the Zhenyuan era (801), records that the son of Li in Demao Fang 德懋坊 became a monk with the Buddhist name Ruyuan 如圓 at the Tongde Temple 同德寺 (Chen 1991, vol. 12, p. 166). Similarly, The Epitaph of Zhang Shen and His Wife Fan 張詵及妻樊氏墓誌, engraved in the first year of the Yongzhen era (805), declares that the eldest daughter of Zhang in Yongtai Fang 永泰坊 became a nun with the Dharma name Yixing 義性 at the Ningcha Temple 甯刹寺 (Chen 1991, vol. 12, p. 191). Likewise, The Epitaph of Sun Tong 孫通墓誌, engraved in the first year of the Wenming 文明 era (684), says that Sun’s daughter was a nun with the Dharma name Xiuding 修定 in the Jingfu Temple 景福寺 (Chen 1991, vol. 6, p. 99).

Another way was listing the monastic children’s identity together with the official children to show respect to Buddhistsin writing epitaphs. For example, The Epitaph of Yu Ben 于賁墓誌 records that his eldest son was an assistant magistrate of Yishi county in Puzhou 蒲州猗氏縣丞, his second son was a monk in Tiangong Temple 天宮寺, his third son was a changxuan 常選 (a type of official position) in the Ministry of Personnel 吏部 (Ministry of Official Personal Affairs in feudal China), and the fourth son was a Right Qianniu 右千牛 (a type of officer, guarding the emperor closely) (Chen 1991, vol. 8, p. 115). All these instances are not only true records of the people in the Eastern Capital worshipping monks and the close interaction between the people and monks or nuns, but also indirectly reflect the popularity of the social concept of practicing Buddhism as a high priority in Luoyang during the Tang Dynasty.

The residents of Luoyang readily accepted Buddhist ideas and culture. This acceptance was reflected in the fact that multiple family members became monks or nuns either simultaneously or successively: brothers and sisters, aunts and nieces all became monks or nuns, usually in the same temple. They can be described as blood-related Buddhist monastic companions, and there were three main types of situations in which that phenomenon occurred.

The first type is that brothers or sisters from the same family became monks or nuns, either in the same temple or in different ones. Among these individuals, the most famous was Master Xuanzang 玄奘 from Goushi County 缑氏县 in Luoyang. In his childhood, he practiced Buddhism with his elder brother, Master Changjie 長捷, in the Pure Land Temple 淨土寺 (Dao 2014, vol. 4, p. 95). Similarly, Daoyue 道岳 and his two brothers all became monks. A prominent monk from Luoyang, Master Mingkuang 明曠, became a monk at the age of seventeen, as did his elder brother Daoyue. Master Mingkuang was proficient in Shastra on Prajnaparamita Sutra 大智度論 and Vinaya of Ma-hasamghika 僧祇律. Likewise, Daoyue’s younger brother, Master Minglue 明略, became a monk at the age of nineteen and was skilled in expounding the Nirvana Sutra 涅槃經 (Dao 2014, vol. 13, p. 457). Moreover, The Buddhist Stone Pillar Inscription of Zhenjian 真堅經幢銘 records that Zhenjian 真堅 and her sister Zhenxin 真心 became nuns at the Tiangong Temple 天宮寺 and the Anguo Temple 安國寺, respectively, in the Eastern Capital (Zhang 1989, vol. 2, p. 28).

The second type involves aunts and nieces often choosing to become nuns within the same temple. Among the most famous ones are Xiao Yu’s daughters and granddaughter. Xiao Yu 蕭瑀 (575–648), one of the twenty-four meritorious statesmen of Lingyan Pavilion 淩煙閣二十四功臣, was a descendant of the Xiao Liang 蕭梁 royal family and moved to Luoyang in the Sui Dynasty. He served as the prime minister six times during the reign of Emperor Taizong, and his three daughters, Fadeng 法燈 (Metal and Stone Group of Beijing Library 1989, vol. 16, p. 149), Fale 法樂 (Metal and Stone Group of Beijing Library 1989, vol. 16, p. 148), and Fa Yuan 法願 (Wang 1998, vol. 54, p. 148), all became nuns at the Jidu Temple 濟度寺. Xiao Yu’s granddaughter, Huiyuan 惠源, also became a nun at the same temple (Zhou 1992, p. 1473).

In the epitaphs unearthed in Luoyang, there are some more examples of aunts and nieces entering monastic life together. For instance, The Epitaph of Bhiksuni Li Wushi 比丘尼李五師墓誌 records that Bhiksuni Wuyin 悟因 followed her aunt, Nun Lu of Anguo Temple, to become a nun in the same temple (Zhao and Zhao 2007, p. 312). The Epitaph of Nun Wei 韋和尚墓誌records that Nun Wei served as the abbess of the Anguo Temple, and her cousin Rucan 如燦 and niece Qixu 契虛 also became nuns in the temple as her disciples (Zhou 1992, p. 1836). The Epitaph of Chengkong 澄空墓誌 records that Chengkong of the Anguo Temple and her niece Qiyuan 契源 practiced together at the Anguo Temple (Chen 1991, vol. 12, p. 128). The Epitaph of Kou Youjue 寇幼覺墓誌 records that at the age of six, Kou became a nun and practiced at the Linzhi Temple 麟趾寺 in the Eastern Capital and that her niece Rucan 如燦 also became a nun (Luoyang Cultural Relics Work Team 1991, p. 617).

The third type is that the mother and daughter or mother and son jointly practiced Buddhism: the mother usually practiced at home, while the daughter or son became a nun or a monk in a Buddhist temple. For example, The Epitaph of Bhiksuni Zhihong 比丘尼志弘墓誌 records that Zhihong, the granddaughter of King Xu, Li Sujie 許王李素節, became a nun at the Ningcha Temple 寧刹寺 at the age of fifty-five. Zhihong’s daughter Wuzhen 悟真 also became a nun (Zhang 2008, vol. 5, p. 90). The Epitaph of Wang Zhiyan 王智言墓誌 records that Wang’s wife devoted herself to the practice of Buddhism at home, decorating her house in the shape of a Buddhist temple and sending her son to become a monk (Zhou 1992, p. 1497). Likewise, The Epitaph of Liu 劉氏墓誌 records that Madame Liu studied Buddhism at home, and her son became a monk and worshipped the Buddha (Zhao 2004, p. 193). Similarly, The Epitaph of Qingjingguan 清淨觀墓誌 records that Madame Wang practiced Buddhism at home in Anye Li 安業里, while her daughter Tanran 坦然 went to the Anguo Temple to practice Buddhism (Zhongguo Institute of Cultural Relics 2008, p. 175). On a similar note, The Epitaph of Han Shen 韓神墓誌 records that Han practiced Buddhism at home, and his son was a monk in the Dayun Temple (Zhou 1992, p. 1106).

The emergence of blood-related monastic companions in Buddhist practice resulted from the strong prevalence of Buddhism in Luoyang. During the Tang Dynasty, residents regarded becoming a monk or a nun as a way of showing filial piety: practicing Buddhism in temples could earn a good reputation. Therefore, to some extent, adopting a Buddhist monastic life became a highly regarded social trend. There are descriptions of social life written by contemporary people of that era: epitaphs unearthed in Luoyang contain many examples of the demonstration of filial piety through the choice of becoming a monk or a nun. For example, The Epitaph of Wang Duan 王端墓誌, engraved in the first year of the Baoli era (825), records that Wang of Qinghua Fang 清化坊 in the Eastern Capital chose to worship Buddha at home to express his filial piety for his parents (Metal and Stone Group of Beijing Library 1989, vol. 30, p. 45). Moreover, The Epitaph of Li Su 李肅墓誌, engraved in the first year of the Yongzhen era (805), records that Li’s younger sister Dharma—named Yiyun 義藴—chose to become a nun in her childhood and practiced Buddhism at the Anguo Temple in order to repay the kindness of her parents in raising her (Chen 1991, vol. 12, p. 195). Parents also considered sending their children to become monks or nuns as an act of filial piety. For example, The Epitaph of Wang Ting’s Wife Song Nizi 王挺妻宋尼子墓誌, engraved in the second year of Changshou era (693), records that Song sent his son Xuansi玄嗣 to become a monk at the Eastern Temple (Henan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Henan Luoyang Cultural Relics Anagement Office 1984, p. 405). The Epitaph of Wang Zhiyan and His Wife王智言及妻墓誌 records that in the twenty-seventh year of the Kaiyuan era (739), Madame Zhang in Yiren Li 依仁里 practiced Buddhism at home and sent her son to become a monk (Chen 1991, vol. 10, p. 170).

Buddhism flourished because the rulers formulated a series of policies that favored the development of Buddhism. These policies included appointing Buddhist officials, setting up special Buddhist households, such as Sengqihu 僧祗戶 (households for monks and nuns) and Fotuhu 佛圖戶 (households for those who served monks and nuns), compiling registers for monks and nuns, regulating the construction of temples and monasteries, and providing not only policy but also economic support to monks and nuns. In the equal-field system implemented during the Tang Dynasty, “each Daoist was given thirty acres of land, each female Daoist twenty acres, and each monk or nun likewise 凡道士給田三十畝, 女冠二十畝, 僧尼亦如之” (Li 2014, vol. 3, p. 75). Temples and monasteries owned land and enjoyed support from the government and wealthy aristocrats besides receiving donations from the public. The temples and monasteries not only possessed land, wealth, and labor but also enjoyed privileges such as exemption from corvée labor, military service, and taxes. The strong economic foundation provided a conducive and relaxed academic environment for the development of Buddhism. Monks and nuns could focus on spreading Buddhism, and they had a significant impact on the popular practice of Buddhism among the general public.

It can be seen that in the temples of Luoyang during the Tang Dynasty, although the status of monastic monks and nuns had changed from kinship to a mentoring relationship, when their masters (relatives of secular society) passed away, the apprentice, as a member of a secular family, used Confucian etiquette to show filial piety to the elders and send them off. At the same time, after the death of parents in secular families, many monks and nuns used Confucian etiquette within the role of secular children to show filial piety, which is a concrete manifestation of the deep integration of Buddhist and Confucian ideas. An example of this integration is seen in the family of Master Bianhui 辩惠 in The Epitaph of Master Bianhui 辩惠墓誌 engraved in the fourteenth year of the Tianbao era (755). The inscription states:

“The secular name of Master Bianhui is Fang Yanjing… Her grandfather was Fang Xianzhi, the descendant of Duke Cheng 成公 in Jiaodong, and he was the Governor of Jizhou, with a rank of Yinqing guanglu dafu 银青光禄大夫. Her father was Fang Wen, a literary attendant of the Prince… At the age of nine, she was sent to a temple to become a nun due to the death of her grandmother Wang, who was titled Xianjun of Langya County 琅琊郡君. Previously, the family members ate a hundred days monastery dishes without meat or fish… At the age of eighteen, she received half precepts, and at the age of twenty, she received full precepts and practiced at the Grand Anguo Temple in the Eastern Capital… When she passed away, her disciples, also her nieces, Fang Zhao and Hongzhao, wept to complete the mourning ceremony to show their family filial piety… 禪師釋名辯惠, 字嚴淨, 俗姓房氏……王父皇銀青光祿大夫、冀州刺史、膠東成公, 諱先質。烈考皇朝太子文學, 諱溫……禪師九歲, 祖母琅琊郡君王氏薨, 百日齋, 度為沙彌尼……十八受半戒, 廿受具戒。纔三日, 於東都大安國寺通誦聲聞戒經……弟子姪女昭、弘照等, 泣奉遺願……”.(Wu 1991, vol. 4, p. 25)

Bianhui once practiced at the Jingfu Temple, the Anguo Temple in Luoyang, and the Fayun Temple 法雲寺 in Chang’an. After her death, her funeral was arranged by her disciples Fang Zhao and Fang Hongzhao, who were also her nieces, in accordance with Confucian customs. Relatives became monks or nuns at the same time or in succession, and secular kinship transformed into a mentoring relationship and a religious organizational relationship, but the monks and nuns still supported and cared for each other. The connection of secular identity and family members’ Buddhist practice in the same temple influenced the existing membership structure and closed practice model of the monastic community as well as the pre-existing mentoring relationship and management models in the traditional temples. The cultivation groups and practices based on kinship also weakened the religious and sacred aspects of Buddhism, which diminished the mystery and exclusivity of temples.

Another example is from The Epitaph of Han Shen 韓神墓誌, engraved in the third year of the Jinglong era (709). The inscription states:

“He devoted himself to practice Buddhism at home and had profound insight into Buddhist scriptures and was proficient in The Diamond Sutra and Nirvana Sutra… he passed away at home on October 14th in the third year of Jing Long era… He was buried with his wife in Mt. Mangshan of Luoyang… His monk son Daosheng, born with a knowledge of the practice of Buddhism and filial piety, practiced in the Dayun Temple. He wrote an epitaph to demonstrate the pleasant virtues of his father and show gratitude for his father’s kindness during his upbringing 迺息意常務, 專心空門, 般若玄關, 即能盡了, 涅槃奧義, 靡所不通……以景龍三年十月十四日終於私第……合葬於北芒里之山原……有子中大雲寺僧道生, 道實生知, 孝惟天與。永誦報恩之偈, 思題旌德之銘……”.(Chen 1991, vol. 8, p. 132)

Han Shen, a native of Baitu Xiang 白土鄉 in Luoyang, practiced Buddhism before he passed away. After his death, his son Daosheng, a monk at the Dayun Temple, acted as a member of a secular family and wrote a Confucian-style epitaph to express his gratitude for his father’s upbringing. A similar situation can also be seen in The Epitaph of Chengkong 澄空墓誌, which records that in the ninth year of the Zhenyuan era (793), after the death of Chengkong, the nun of the Anguo Temple, her apprentice and niece, Qiyuan 契源, arranged her funeral ceremony according to local Confucian customs (Chen 1991, vol. 12, p. 128) to show her family filial piety.

Another example of the blend of Confucianism with Buddhism can be seen in The Epitaph of Wang Yu’er 王玉兒墓誌, which records that in the tenth year of the Zhenguan era (636), Madame Wang of Shiyong Fang 時邕坊 passed away. Her monk sons, Huizheng 惠政 and Xingwei 行威, went home to attend their mother’s funeral as members of a secular family (Chen 1991, vol. 2, p. 44).

As a foreign religion, Buddhism was initially unable to adapt to China’s unique social environment, and its advocacy of leaving home practice in Buddhist temples or monasteries conflicted with traditional Confucian concepts such as filial piety at home, so the early followers of Buddhism were mainly in the upper class elites and were not very popular among the people. When Buddhism adjusted its way of practice and religious beliefs gradually, changing from a spiritual belief into an on-the-ground lifestyle, people can practice Buddhism in their family space anytime and anywhere, while monks and nuns can freely shuttle between temples and families. The ethical conflict between Confucianism and Buddhism between “filial piety” and “becoming a monk or a nun” has been adjusted and dissolved, and secular families and religious beliefs have achieved mutual support and reconciliation.

7. Conclusions

During the Sui and Tang Dynasties, Buddhism reached a peak in its development and had a widespread impact on both the court and the public. As an important component of contemporary historical writing from that time, a large number of epitaphs in the Tang Dynasty unearthed in Luoyang over the last century have provided detailed records of the great prosperity and historical context of Buddhist beliefs in the Luoyang region from various perspectives. These stone inscriptions fill many gaps in the traditional Buddhist literature and provide new materials and open up new fields for the study of Buddhism during the period of the Tang Dynasty. In this article, we aimed to explore the dissemination and acceptance of Buddhism in the Luoyang region through use of stone inscription materials. The Eastern Capital of the Tang Dynasty, also known as the Divine Capital of the Wu Zhou Dynasty, served as our research object. We drew the following conclusions.

Firstly, the stone inscription documents provide additional information about the locations of the suburban Buddhist temples, which were mainly gathered in three areas, namely the ancient city of Han and Wei in the east, Mt. Songshan area in the south, and the Longmen area in the south of the city. Specifically, the following temples were located in these three areas: the White Horse Temple, the Shaolin Temple, the Huishan Temple, the Wanshou Temple, the Tianzhu Temple, the Fengxian Temple, the Jingshan Temple, the Guanghua Temple, the Baoying Temple, the Bodhi Temple, the Xiangshan Temple, the Qianyuan Temple, the Yique Temple, the Hufa Temple, the Yuanxian Temple, and the Hongsheng Temple. Most of these Buddhist temples were old, dating back to the Northern Wei Dynasty, and they were nestled amidst mountains and rivers, with beautiful scenery and a blend of natural sights and cultural ambiance.

Secondly, the stone inscriptions reveal that Northern Chan Buddhism was widely spread in Luoyang. And Puji, the disciple of Shenxiu, the founder of Northern Chan, and Hongzheng, the disciple of Puji, as well as Śubhakarasiṃha of Esoteric Buddhism, all promoted Buddhism in Luoyang. They preached Buddhist scriptures everywhere and recruited disciples from a broad base, earning great respect from the local people. The contents of these stone inscriptions supplement some missing details in historical literature records.

Thirdly, the stone inscriptions record the types of Buddhist scriptures chanted and read in the Luoyang region, mainly including the Nirvana Sutra, Vajra Prajna Paramita Sutra, Vimalakirti-nirdesa Sutra, The Lotus Sutra, Avatamsaka Sutra, Lankavatara Sutra, and Viśeṣa-cinti-brahma-paripṛcchāSutra, which is not consistent with the types of Buddhist scriptures that were emphasized and preached by temple monks, as stated in historical documents such as The Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks and The Biographies of Eminent Monks of the Song Dynasty.

Fourthly, the stone inscriptions reveal that there were three groups of ascribed backgrounds for receiving ordination. The first group is those who received ordination in childhood: publicizing Buddhist scriptures and promoting Buddhism were their lifelong missions, and they eventually became monks or nuns. The second group is those who decided to convert to Buddhism through learning: after a long period of studying Confucian and Daoist classics, they decided to abandon Confucianism and practice Buddhism even though they were already officials who had passed the imperial examination. They delved deeply into the practice of Chan, and their motivation to practice Buddhism was to obtain spiritual satisfaction. The third group is those who began to practice Buddhism when trapped in life. Most of this group embraced Buddhism after experiencing setbacks in life. Mostly composed of women, this group’s motivation for turning to Buddhism was to seek spiritual support and blessings in the future.

Fifthly, worshipping the Buddha had become a common way of daily life in Luoyang, characterized by a noticeable succession of blood-related monastic companions adopting Buddhist practices. Specifically, two or more relatives of a family became monks or nuns at the same time or consecutively. This phenomenon can be divided into three categories. The first category is a generation of brothers and sisters who became monks or nuns simultaneously or sequentially. The second category is the generations of aunts and nieces who became nuns, usually at the same temple. The third category is the generations of mothers and daughters (or sons) who practiced Buddhism, with mothers usually staying at home and daughters (or sons) becoming nuns or monks. The blood-related monastic companion of Buddhist practice affected the traditional member structure and closed nature of Buddhist monastic community as well as the established mentoring relationship and management methods within traditional monasteries. These changes resulted in a weakening of the religious and divine aspects of Buddhism, consequently decreasing the mystery and secluded nature of temples and monasteries and promoting communication and the blending of Buddhism and traditional Chinese culture.

To sum up, the spread and acceptance of Buddhism in Luoyang is a significant example of the special role played by the region in the process of communication and interaction between Buddhism and traditional Chinese culture. However, the Buddhist materials in the recorded literature mainly include macroscopic Buddhist history, important Buddhist events, the deeds of renowned monks, and Buddhist buildings. The specific historical details related to the spread of Buddhism and the daily Buddhist beliefs of citizens in Luoyang are mainly recorded in stone inscriptions and rarely seen in historical documents. We hope that this research, by utilizing a large number of stone inscriptions, will promote the study of some important issues of Buddhism such as the relationship between Buddhism and capital cities, and the rise and fall of the Northern Sect of Chan Buddhism in Luoyang and so on.

Author Contributions

Investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, T.S.; editing and supervision, Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [Key project of China National Social Science Fund (19AZW011)].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chang, Songmu 常松木. 2008. Guyun—Zhongguo songshanlishijianzhuqun 古韻—中國嵩山歷史建築群 [Classical Charm—Historical Building Complex in Mt. Songshan of China]. In Dengfengwenshiziliao 登封文史資料 [Literary and Historical Materials of Dengfeng]. Zhengzhou: Henan People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Changan 陳長安. 1991. Suitang wudai muzhi huibian·luoyangjuan 隋唐五代墓誌匯編·洛陽卷 [Collection of Inscriptions of the Sui, Tang, and Five Dynasties—Luoyang Volume]. Tianjin: Tianjin Ancient Books Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Dao, Xuan 道宣 (596–667). 2014. Xu gaosengzhuan 續高僧傳 [A Continuation of the Biography of Eminent Monks]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Gao 董誥 (1740–1818). 1983. Quan tangwen 全唐文 [Complete Prose Works of the Tang Dynasty]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Benxing 郝本性. 1991. Suitang wudaimuzhihuibian·henanjuan 隋唐五代墓誌匯編·河南卷 [Collection of Epitaphs of the Sui, Tang, and Five Dynasties—Henan Volume]. Tianjin: Tianjin Ancient Books Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Henan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics河南省文物研究所, and Henan Luoyang Cultural Relics Anagement Office河南省洛陽地區文管處編. 1984. Qiantangzhizhai cangzhi 千唐志齋藏志 [The Epitaphs Collected in Qiantang Zhizhai]. Beijing: Cultural Relics Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Xudong 侯旭東. 2015. Wu, liu shiji beifang minzhong fojiaoxinyang-yi zaoxiangji wei zhongxin de kaocha 五,六世紀北方民眾佛教信仰——以造像記為中心的考察 [Buddhist Beliefs of Northern People in the Wu and Sixth Century—An Investigation Centered on the Buddhist Statue Inscriptions]. Beijing: Social Science Literature Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Jiongjiong 黃炯炯. 2016. Tangdai songshansiyuanyanjiu 唐代嵩山寺院研究 [Research on Temples in Mt. Songshan in the Tang Dynasty]. Master’s thesis, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China. [Google Scholar]

- James, William. 2009. The Varieties of Religious Experience. Translated by Yue Tang. Beijing: Commercial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Fang 李昉 (925–996). 1966. Wenyuanyinghua 文苑英华 [The Classics of Literary World]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Linfu 李林甫 (758–814). 2014. Tang liudian 唐六典 [The Six Satute Books of the Tang Dynasty]. Collated by Zhongfu Chen 陳仲夫. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yinghui 李映輝. 2004. Tangdai fojiao diliyanjiu 唐代佛教地理研究 [A Study of Buddhist Geography in the Tang Dynasty]. Changsha: Hunan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luoyang Cultural Relics Work Team洛陽市文物工作隊. 1991. Luoyang chutulidaimuzhijisheng 洛陽出土歷代墓誌輯繩 [Collection of Inscriptions of Past Dynasties Unearthed in Luoyang]. Beijing: China Social Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Metal and Stone Group of Beijing Library北京圖書館金石組. 1989. Beijing tushuguancangzhongguolidaishiketabenhuibian 北京圖書館藏中國歷代石刻拓本匯編 [Collection of Rubbings of Stone Engravings from Various Dynasties in Beijing Librar]. Zhengzhou: Zhongzhou Ancient Books Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Sima, Qian 司馬遷. 1959. Shiji 史記 [The Historical Records]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Ting 宋婷. 2022. Tangdai beizhishuxiezhongdeluoyang 唐代碑誌書寫中的洛陽 [Luoyang Seen in the Stone Inscriptions Writing of the Tang Dynasty]. In China Social Science Daily. Beijing: Social Sciences in China Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Lanfeng 孫蘭風. 1992. Suitang wudaimuzhihuibian (Beijing daxuejuan) 隋唐五代墓誌彙編(北京大學卷) [Compilation of Inscriptions of the Sui, Tang, and Five Dynasties (Peking University Volume)]. Tianjin: Tianjin Ancient Books Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Chang 王昶 (1725–1806). 1998. Jinshi cuibian 金石萃編 [Collection of Metal and Stone Engravings]. Nanjing: Jiangsu Ancient Books Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Pu 王溥 (922–982). 1955. Tang huiyao 唐會要 [The Compilation of State Regulations in the Tang Dynasty]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, Stanley. 2010. Buddhism under the T’ang. Translated by Yu Zhang. Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Yucheng 溫玉成. 1996. Luoyang Dafuxiansilishi kaocha 洛陽大福先寺歷史考察 [Historical Investigation of Dafuxian Temple in Luoyang]. In Luoyang kaogu sishinian-1992 Luoyang kaoguxueshuyantaohuilunwenji 洛陽考古四十年—一九九二年洛陽考古學術研討會論文集 [Proceedings of the Luoyang Archaeological Academic Symposium in 1992]. Beijing: Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Gang 吳鋼. 1991. Suitangwudaimuzhihuibian·shanxijuan 隋唐五代墓誌匯編·陝西卷 [Collection of Epitaphs of the Sui, Tang, and Five Dynasties—Shanxi Volume]. Tianjin: Tianjin Ancient Books Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Yuanzhen 吳元真. 2000. Beijing tushuguancanglongmenshikuzaoxiangtijitabenquanbian 北京圖書館藏龍門石窟造像題記拓本全編 [Completed Works of Rubbings of Inscriptionson Buddhist Statues in Longmen Grottoes Collected by Beijing Library]. Guilin: Guangxi Normal University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Zhenshi 蕭振士. 2014. Zhongguo fojiao wenhuajianmingcidian 中國佛教文化簡明辭典 [A Concise Dictionary of Chinese Buddhist Culture]. Beijing: World Book Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, Deyong 辛德勇. 2006. Dafuxiansi weizhiyuYouyifanggengming Jide shijian 大福先寺位置與遊藝坊更名積德時間 [The location of Dafuxian Temple and the Time of Renaming Youyifang to Jidefang]. In Suitangliangjingcongkao 隋唐兩京叢考 [Textual Research on Two Capitals of Sui and Tang Dynasties]. Xi’an: Sanqin Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Song 徐松 (1781–1848). 2013. Tang liangjingchengfangkao 唐兩京城坊考 [Textual Research on the Two Capital Cities of the Tang Dynasty]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Yuanjia 楊園甲. 2020. Suitang luoyangfosiyanjiu 隋唐洛陽城佛寺研究 [Research on Buddhist Temples in Luoyang during the Sui and Tang Dynasties]. Master’s thesis, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Zengwen 楊曾文. 1999. Tang wudaichanzongshi 唐五代禪宗史 [History of Chan Buddhism in the Tang and Five Dynasties]. Beijing: China Social Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zan, Ning 贊寧 (919–1001). 1987. Song gaosengzhuan 宋高僧傳 [Biography of Eminent Monks in the Song Dynasty]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Naizhu 張乃翥. 1989. Longmen cangchuangdubaliangti 龍門藏幢讀跋兩題 [Two Topics on Reading the Postscript of Buddhist Stone Pillars in Longmen]. Dunhuang Research 2: 28. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Naizhu 張乃翥. 2008. Luoyang xinjishikesuojiantangdaizhongyuanzhi fojiao 洛陽新輯石刻所見唐代中原之佛教 [Buddhism in the Central Plains of the Tang Dynasty as Seen in the New Series of Stone Engravings in Luoyang]. Central Plains Cultural Relics 5: 91. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Junping 趙君平. 2004. Mangluo beizhisanbaizhong 邙洛碑誌三百種 [Three Hundred Types of Epitaphs Unearthed in Luoyang]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Junping 趙君平, and Wencheng Zhao 趙文成. 2007. Heluo mukeshiling 河洛墓刻拾零 [Compilation of Stone Inscriptions Unearthed in Heluo Area]. Beijing: Bibliographic Literature Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Junping 趙君平, and Wencheng Zhao 趙文成. 2015. Qin-jin-yu xinchutumuzhisouyixubian 秦晉豫新出墓誌蒐佚續編 [A Continuation of Collection of Inscriptions Newly Unearthed in Shanxi, Shanxi and Henan]. Beijing: National Library Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Zhenhua 趙振華. 2009. Luoyang xinchubiqiunimuzhiyutangdaidongdushengshansi 洛陽新出比丘尼墓誌與唐代東都聖善寺 [The Newly Unearthed Epitaph of Bhiksuni in Luoyang and the Shengshan Temple in the Eastern Capital of the Tang Dynasty]. In Gudailuoyangmingkewenxianyanjiu 洛陽古代銘刻文獻研究 [Research on Ancient Inscription Documents in Luoyang]. Xi’an: Sanqin Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Zhongguo Institute of Cultural Relics中國文物研究所. 2008. Qiantang Zhizhai Museum 千唐志齋博物館: Xinzhongguo chutu muzhi•hanansan•Qiantang Zhizhaiyi 新中國出土墓誌•河南三•千唐志齋壹 [Collection of Epitaphs Unearthed in New China: Henan Henan Volume 3, Qiantang Zhizhai Volume 1]. Beijing: Cultural Relics Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Shaoliang 周紹良. 1992. Tangdai muzhihuibian 唐代墓誌彙編 [Collection of Epitaphs of the Tang Dynasty]. Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Zürcher, Erik. 2003. The Buddhist Conquest of China: The Spread and Adaptation of Buddhism in Early Medieval China 佛教征服中國:佛教在中國中古早期的傳播與適應. Nanjing: Jiangsu People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).