Abstract

For historical reasons, the vast majority of primary schools in the Republic of Ireland are under the patronage of the Catholic church. Patronage involves a number of responsibilities, including the provision of a Patron’s Programme. Traditionally in the form of Religious Education (RE), such programmes should satisfy the curricular requirement for religious/ethical education and act as an expression of school ethos. In order to meet this responsibility, the Irish Episcopal conference in 2015 published its first curriculum in Religious Education, which forms the basis for the Grow in Love programme for pupils from Junior Infants to Sixth Class in all Catholic primary schools. However, effective teaching and learning of RE is dependent on the ‘buy in’ of those teaching it. The religious beliefs, understandings, and practices of those teaching RE are influential in this regard. Drawing from the data of a large-scale, multi-phase study, this paper describes the religious identity and beliefs of first-year students entering an Initial Teacher Education programme in Ireland—in this case, the Bachelor of Education (BEd) degree—to qualify as primary-level teachers. It situates the data in the wider context of religious identity and beliefs in Ireland and goes on to explore how the religious profiles of these students fit with the required understanding, knowledge and ability to teach Religious Education in Catholic schools. Findings indicate that the majority of these students identify as Catholic and believe in God. For most, God is important in their lives. However, there is a complexity to these beliefs, with a significant number who do not know what to think. This paper concludes with a discussion of the implications of these findings for the teaching of Religious Education and for the patrons of Catholic schools.

Keywords:

Catholic schools; belief; identity; God; student teacher (ITE); Religious Education; Grow in Love 1. Introduction

The Irish primary school system is, overall, a privately managed, state-funded system of education. For historical reasons, it is also largely denominational. Although there is widespread agreement that this legacy is problematic (Tuohy 2013; Kieran and McDonagh 2021; McGraw and Tiernan 2022), it is still the case that 89% of primary schools have a Catholic patron. Under the Education Act (Ireland 1998), the patron has numerous rights and responsibilities, one of which is to uphold the characteristic spirit (ethos) of the school. One clear expression of ethos is the Patron’s Programme, which traditionally fulfilled the requirement for Religious Education as a subject on the curriculum. In denominational schools, it still takes the form of a Religious Education (RE) programme.

In recent years, the Catholic community has carried out considerable work on its Patron’s Programme by means of the Catholic Preschool and Primary Religious Education Curriculum in Ireland (IEC 2015) and the well-received RE programme Grow in Love (Kelly 2021). Both are grounded in the central tenets of the Catholic Christian faith. However, as with any programme, the teaching and learning of the programme rely on the ability of teachers to understand, appreciate and communicate these fundamental concepts.

At the same time, reflective of similar international patterns, Catholic education in Ireland finds itself in a detraditionalised cultural context (Boeve 2007). The Irish religious landscape is changing. Census data reveal that the percentage of those who identify as Catholic is in steady decline, while the proportion of those with no religion continues to rise. Christian religious practice in Ireland is also decreasing, especially among young people (cf. Meehan and Laffan 2021). This context and its implications for Catholic education are discussed further below. It certainly raises questions for the teaching and learning of Religious Education (RE) in Catholic schools, such as, to what extent are the beliefs of teachers reflective of the central themes of the Patron’s Programme?

This paper arises from a larger study on the religious identity, beliefs and practices (religiosity) of Initial Teacher Education (ITE) students (first years) taking the Bachelor of Education (BEd) degree in order to qualify as primary-school teachers in the Republic of Ireland (henceforth Ireland). Giving voice to student teachers in order to understand their religious views, beliefs and practices and the ensuing implications for RE in Catholic primary schools was a specific focus. Because of the dominance of Catholic schools at primary level, the vast majority of students who qualify and seek employment as primary-level teachers in Ireland take up positions in Catholic schools. The research question at the centre of this study is: how congruent are the beliefs of student teachers with the core themes of the Catholic Preschool and Primary Religious Education Curriculum in Ireland (CPPREC) and Grow in Love? Findings indicate that while most teachers identify as Catholic, their beliefs are multi-variant and complex. Significantly, the data suggest that self-identification as Catholic does not necessarily imply belief in God. The findings of this study suggest implications for Catholic education in Ireland that resonate with many themes in this Special Issue, particularly the need for new approaches to encouraging religious literacy among teachers in Catholic schools.

1.1. Religious Education and Catholic Primary Schools in Ireland

In Ireland today, 96.4% of schools at primary level are denominational. Such schools are under the patronage or trusteeship of a faith community; 89% have a Catholic patron. Multi-denominational schools make up 5.4%, under more recent patrons such as Educate Together (DE 2023). Irrespective of school patronage, the curricular framework for all schools is set by the Minister of Education, through the National Assessment for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA).

In 2023, the Department of Education (DE) published the Primary Curriculum Framework for Primary and Special Schools (hereafter, the Framework). The Framework aims ‘to provide a strong foundation for every child to thrive and flourish, supporting them in realising their full potential as individuals and as members of communities and society’ (DE 2023, p. 5). This aim is to be achieved through five broad curricular areas to be developed by the NCCA: Languages; Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) Education; Wellbeing; Arts Education; and Social and Environmental Education. In addition, the Framework also recognises the right of school patrons ‘to design their own programme in accordance with the ethos of their school’ (p. 14). Every Patron’s Programme is to be developed by a school’s patron with the aim of contributing to children’s holistic development, ‘particularly from the religious and/or ethical perspective, [that] underpins and supports the characteristic spirit of the school’ (p. 19).

This dimension of the Framework is reflective of Section 30 of the Education Act (Ireland 1998), which provides for Religious Education and the right of patrons to design a RE curriculum for their schools. Further, the Act obliges the Minister of Education to ensure that adequate time is allocated to the delivery of this curriculum area. The 2023 Framework adopts Religious/Ethical/ Multi-belief, and Values Education—The Patron’s Programme as the title of this area. In Catholic schools, this area continues to be called Religious Education with the CPPREC (IEC 2015) as the basis for the development of Religious Education programmes.

1.2. Catholic Preschool and Primary Religious Education Curriculum for Ireland (IEC 2015)

The teaching and learning of Religious Education in a primary school is a matter for the patron (usually the bishop of the local diocese), delegated to the Board of Management (Ireland 1998). The year 2015 marked a milestone in Catholic primary education, with the publication by the Irish Episcopal Conference (IEC) of its first curriculum in Religious Education: The Catholic Preschool and Primary Religious Education Curriculum for Ireland (CPPREC). Up to this point, the IEC had published Religious Education programmes for schools, such as the Alive O and Children of God series, without the foundation of a curriculum. The CPPREC (IEC 2015) for Ireland provides a comprehensive curriculum to shape the development of all RE programmes for Catholic schools in Ireland—north and south. ‘The aim of this Religious Education curriculum is: to help children mature in relation to their spiritual, moral and religious lives, through their encounter with, exploration and celebration of the Catholic faith’ (p. 31).

The CPPREC (IEC 2015) has a Trinitarian focus: ‘the mystery of God—Father, Son and Holy Spirit—is the centre of the curriculum’ (IEC 2015, p. 25). This is the organising principle around which the four strands of the curriculum—Christian Faith, Word of God, Liturgy and Prayer, and Christian Morality—are structured. Everything that is taught revolves around this idea: God is Trinity. This is the core belief that supports and orientates all that is taught in Religious Education. It is the foundation upon which any programme is to be built. While there are many other important elements to the curriculum that emerge from this principle, as mentioned in the strands above, we have sought to concentrate on this one in particular: belief in God as Father, Son and Holy Spirit. The curriculum has a clear idea of the nature of God in the Christian tradition. In this research project, we wanted to see if this idea of God was shared by the incoming cohort of students preparing to become primary school teachers.

Another way of saying that God is Trinity is to say that God is love (Catholic Church 2000, #253). According to Barron (2007), ‘If you say that God is love, you have to mean that within the very being of God there is a play between the Lover, the Beloved and the Love they share—yes, God loves that world, that’s true, but more primordially God is love’. The phrase God is love, is shorthand for God is Trinity. Rather than God is loving, John’s letter clearly states that ‘God is love’ (1 John 4:8,16). For Pope Benedict XVI, ‘These words [God is love] from the First Letter of John express with remarkable clarity the heart of the Christian faith’ (Pope Benedict XVI 2006, #1). John’s letters were written in Greek and the word he used for love was agape. This has a particular meaning. Agape is characterised by self-forgetfulness, an overwhelming desire for the well-being of the other. Nothing is sought in return; it is literally unconditional. God is this kind of love. Love is not something that God does; rather, it is who God is.

This God, who is Trinity and love, is both personal and purposeful. Rather than some anonymous, distant, impersonal force, this God seeks to draw close to all people, to be in a relationship with them. The CPPREC (IEC 2015) seeks ways to help children to develop ‘an informed, mature response to God’s call to relationship’ (p. 15). It wants them to understand that the God revealed in the Christian tradition wants to draw close to them, to become their friend (see Exodus 33:11; John 15:14–15). It lifts up the call to love one’s neighbour and care for creation.

Grow in Love

Emanating from the CPPREC (IEC 2015), Grow in Love is the Religious Education programme for Catholic primary schools throughout Ireland. A developmental programme, with strands, strand units and aims and similar to that of other subjects, it applies to children from Junior Infants to Sixth Class. Just as the mystery of God as Trinity is the centre of CPPREC (IEC 2015), so the idea that God is love is at the heart of the programme. It ‘seeks to reveal a God who is Love—present to all in a purposeful and personal manner’ (O’Connell 2017, p. 86). The title Grow in Love makes sense in this regard, with the word ‘Love’ interchangeable with the word ‘God’. It is hoped that children will notice and respond to the presence and action of God/Love in their lives through their relationships with their families, friends and creation. It is important not only that teachers understand and teach the programme accurately and in an age-appropriate manner, but that they can foster, where appropriate, a relationship between the children and this God, who is love (1 John 4:8, 16).

God as love is an abstract idea; it is ‘made pre-eminently visible in the person of Jesus Christ’ (O’Donnell et al. 2019, p. 5). Through the programme, the children come to know the Jesus of history and are introduced to the Christ of faith. Lessons are organised around the liturgical calendar, with themes such as: God, Creation, Jesus, Advent and Christmas, Social Justice, Church, Holy Week and Easter, Eucharist and Morality, with God is love as the central, unifying idea.

1.3. Religious Identity in Ireland Today

The 2023 national census reveals that the Catholic population in the Republic of Ireland stands at 68%. This marks a decrease of roughly 11% from the 2016 census, when Catholics were 79% of the population. Since 2016, the Muslim and Orthodox Christian populations have increased to c. 1.6% and c. 2%, respectively. When the proportion of those who identify as Catholic is combined with that of other Christian and religious traditions (see Table 1 below), we see that 77.8% of the population are members of a religious tradition.

Table 1.

Religions and Worldviews in Ireland. Source: CSO (2016a, 2023).

The number of those indicating No Religion jumped from 9.6% in 2016 to 14.3% in 2023. However, No Religion does not necessarily imply atheistic belief. In fact, the figure for those who self-identify as Atheist has fallen by 87% and now stands at 0.01%. At the same time, the majority of those who identified as having no religion in 2016 also claimed to be spiritual (Behaviour & Attitudes 2016, p. 108).

There are other increases in diversity among the population. For instance, over half a million non-Irish nationals live in Ireland (CSO 2016b), with the largest group of immigrants coming from Poland, the UK, Lithuania, Romania, Latvia, and Brazil (CSO 2016b).

This emerging diversity has introduced alternative world views, practices and beliefs to Ireland. Boeve (2007, p. 24ff) refers to this as religious pluralisation. Catholicism is no longer an assumed fundamental life option—people make religious choices rather than necessarily following in the footsteps of their forebears. This growing diversity relativises the ‘(until recently) unquestioned monopoly position of Christianity in answering question of meaning and values’ (Boeve 2007, p. 26). Christianity is no longer a given and unquestioned horizon of individual and social identity. Sheridan (2022) points out that ‘A significant legislative agenda of successive Irish governments has mirrored the changing Irish population and the changing Irish attitudes towards various social and moral issues’ (p. 60). He points to the two most recent ones: in 2015, an amendment to the constitution to recognise marriage between two people of the same gender, and in 2018 a change to the constitution to allow for legislation on abortion.

Such religious pluralisation gives rise to another of Boeve’s descriptors of the religious situation in Europe, that of detraditionalisation. This term not only alludes to Europe’s declining institutional Christian horizon but also hints at the more generally observed socio-cultural interruption of traditions (religious as well as class, gender, etc.), which are no longer able to pass themselves effortlessly on from one generation to the next (Boeve 2007, p. 21).

Detraditionalisation allows people the opportunity to choose their own path in life. They are freer to shape their own identity in a way that was not possible in earlier times. For instance, they do not have to believe in God or conform to stereotypical images of roles and identity.

This pluralisation and detraditionalisation has given rise to a new ‘social imaginary’ (Taylor 2004). According to Taylor, social imaginary is the ‘ways people imagine their social existence, how they fit together with others, how things go on between them and their fellows, the expectations that are normally met, and the deeper normative notions and images that underlie these expectations’ (p. 23). This new way of thinking has diminished the appreciation for the sacred nature of the world, reduced the numbers of those who identify with a particular religious tradition, privatised religious belief, and shifted the conditions of the plausibility of religious belief. There is now a ‘move from a society where belief in God was unchallenged and indeed, unproblematic, to one in which it is understood to be one option among others and frequently not the easiest to embrace’ (Taylor 2007, p. 3). The conditions for belief have altered.

Boeve echoes these ideas. He believes that there is now ‘a culturally motivated reserve or uneasiness to name God or the divine, or to link God or the divine in definitive ways to a particular tradition’ (Boeve 2007, p. 140). Such uneasiness gives rise to a vague religiosity, both inside and outside the Christian churches. This new pattern or conditions for belief contribute to what Halík (2015) refers to as the seeker–dweller paradigm. For Halík, there is a grey zone between traditional believers and convinced atheists. ‘If we want to understand the spiritual situation of contemporary Western post-secular society, we have to move from the traditional believers–nonbelievers paradigm to the new seekers–dwellers paradigm’ (Halík 2015, p. 131). The Catholic church can be a home for dwellers (traditional believers) and an open space for seekers such as the increasing numbers who say they are spiritual without being religious (Hošek 2015, p. 3); who believe without belonging (Davie 2015).

It seems that the culture in Ireland and in Western Europe has moved from an enchanted age (Weber 1965), where the culture was infused with Christian faith, to a disenchanted one where faith is now an unpopular option that appears to run against the cultural tide of the day. Taylor builds on the work of Weber (1965) and distinguishes between a porous, premodern self, which was open to ‘enchantment’—that is, to ‘spirits, demons, cosmic forces’—and, by extension, to religious faith (Taylor 2007, p. 38). But today, he believes that we live in a time where the self is ‘buffered’ or ‘disenchanted’ and the ‘buffered’ or ‘disenchanted’ self is enclosed by an ‘immanent frame’, one that is largely closed to the possibility of a transcendent dimension of life (pp. 29–43). That said, Groome (2019) believes there are three advantages to this new reality: (a) it encourages a personally chosen faith, (b) it invites an expansion to one’s imaging of God, and (c) it highlights that faith must be free and freeing—an empowering choice, as God intends (p. 30).

1.4. Belief, Belonging and Young People

Recent demographic data reflect this detraditionalised shift among young people in Ireland today. For instance, Bullivant’s (2018) study on religious affiliation found that 54% of 16–29 year olds in Ireland self-identified as Catholic, with 39% not religious (p. 6). In this age group, 26% say they never attended a religious service outside of special occasions (p. 7). Of those who identify as Catholic, 16% say they never pray (p. 9). A 2021 a survey of young people studying for a Professional Masters in Education (primary education), found that while 58% identified as Catholic, their belief in God was multi-variant and complex (Kieran and Mullally 2021). These figures echo those of a previous survey of 16–19 year olds in Ireland who identified as Catholic (see Francis et al. 2019, p. 84). Table 2 below outlines their responses to questions about belief in God.

Table 2.

Belief in God, among 16–19 year olds (adapted from Francis et al. 2019 p. 89).

Whereas 56% of young Catholics in this survey stated a belief in God, almost half of this group were unsure/unbelievers. This disconnect reflects international findings. For instance, ‘in Denmark fully 28% of atheists and agnostics identify as Christians; in Brazil the figure is 18%’ (Bullivant 2018, p. 4). The detraditionalisation of Boeve (2007) is evident in these figures.

Reflecting on these figures, Cullen (2019) says ‘That just around half of the Catholic students surveyed reported that they believe in God … gives pause for thought. If belief in God…is at the core of Catholic identity, then what do young people mean when they identify as Catholic?’ (p. 275). A further question relating to the focus of this study also arises: if belief in God is at the heart of the CPPREC (IEC 2015), what do these findings mean for Religious Education in Catholic schools? In all three studies, a little over half of the young people surveyed said they belonged to the Catholic tradition. However, with a large number of young Catholics uncertain about the existence of God, we can conclude that self-identification as a Catholic does not in itself mean belief in God.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Methods

The findings presented in this article are drawn from a large, multi-phase project which was conducted over a three-year period. The project utilised a mixed methods approach to data collection, allowing the findings to be presented in both a qualitative and quantitative manner.

The quantitative component adopted a cross-sectional, correlational research design. At the beginning of each academic year across the life of the project, Year 1 students on an Initial Teacher Education (ITE) undergraduate programme at primary level were invited to complete a survey in the form of questionnaire. The survey included the 31 questions from the religion section of the European Values Survey (EVS) along with 4 questions regarding influences on religious beliefs formulated by the researchers. The EVS is a largescale, Europe-wide, longitudinal research programme surveying human beliefs, preferences, attitudes, values and opinions among all European citizens. It is a research project that explores how Europeans think about life, family, work, religion, politics and society. The survey also included a Participant Information section, which sought information for instance on age, geographical location and family.

The questionnaire was highly structured, with numerical and closed questions, thus allowing for the generation of frequencies of response and facilitating data analysis with descriptive statistics. It was administered by a research assistant, and answers were gathered electronically, by means of Personal Response Devices (PRD).

Flick (2014) remarks that the volume of qualitative data generated from such a group, when carefully interpreted and utilised correctly, is highly valuable in any research study. Therefore, a qualitative component was included, comprising semi-structured interviews. A question menu was constructed, comprising open-ended questions to encourage the participants’ views and to allow for the development of thought and probing of responses (see Appendix B).

2.2. Sample Group

The instrument was administered to 1720 first-year students entering an undergraduate ITE degree, with a valid response rate of N = 1163 or 67.7%. This represents a convenient random sample taken from within the overall cohort. Convenience sampling is described by Flick (2014) as ‘participants who were selected because they are available’ (p. 175). It also meets the definition for cluster sampling, highlighted by Flick (2014) as ‘naturally occurring groups’, where ‘the population is divided into batches’ (p. 180). As the profile of those entering ITE at primary level is predominately female (82.4%), the minority of participants in this study were male (17.6.%), mirroring the overall gender gap in the teaching profession in Ireland (Heinz et al. 2023). A total of 93.3% of respondents were between the ages of 18 and 19 years and 71.3% came from a rural background. Following completion of the instrument, students were invited to take part in individual semi-structured interviews, digging deeper into the quantitative responses; for this data source, N = 18.

This group offers an interesting insight into the beliefs and practices of student teachers. With 89% of all primary schools under Catholic patronage (DE 2022), it is likely that the majority of those who find employment as primary teachers over the next decade will do so in Catholic schools.

2.3. Approach to Analysis

Adopting an explanatory mixed-methods design, quantitative and qualitative data were analysed independently using the appropriate analytic approaches. The results of both strands of analysis were used to answer the main research question (Creswell and Clark 2011). When researchers begin to analyse data, they must be able to stand behind the validity of the data gathered. The quantitative data gathered were achieved through careful sampling and appropriate statistical treatment. However, quantitative research, by its very nature, possesses a measure of standard error which must be acknowledged. Factors that need to be considered are bias, subjectivity and attitudes; therefore, validity should be seen as a degree, rather than an absolute (Cohen et al. 2011). Once all data across the three years were gathered, they were analysed using PSPP software. It was inputted, and variable names were created, as follows: participant’s information; belief in core teachings of the tradition; faith practices in community; religion and public life; and personal religiosity. These were then subdivided into variable types, labels and values. This led to the generation of a code book. These variables are a subset of the label “Code Religion and Morals”, within the larger EVS study.

Descriptive analysis allows for the transformation of raw data into an ordered form that will allow the data to be interpreted in a descriptive format (Halter 2014). It allows for the descriptions of the basic features and summaries of what is to be found in the data. This was performed through the creation of tables that showed frequencies, percentages, mean and standard deviation. Descriptive statistics present quantitative descriptions in a manageable form. Descriptive statistics were generated on age profile, geographical location, mass attendance, beliefs and practices.

The qualitative data allow the researchers to search for rich patterns and themes across all the evidence gathered. Strauss and Corbin (1990) consider coding to represent the way data are deconstructed, conceptualised and restructured in a new way, leading to the development of theories to explain phenomena. To achieve this, the researchers chose Braun and Clarke’s (2013) thematic analysis. They employed the six phases of coding of thematic analysis, which led to the identification of the following four major themes:

- Images and Understandings of God;

- Religious Identity and Influences;

- Prayer;

- Atheist/Agnostic.

This paper explores results from two of these themes: Religious Identity and Influences; and Images and Understandings of God.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Theme 1: Religious Identity and Influences

According to Werbner (2010), religious identity for believers is about an engagement with the transcendent, both on an individual and community level. People with a religious identity know that they belong to a social group that gives them a value system or an emotional bond. It is ‘above all, a discourse of boundaries, relatedness and otherness on the one hand, and encompassment and inclusiveness, on the other’ (Werbner 2010, p. 243). Ream and Savin-Williams (2003) write that adolescent/young adults’ religious development can be portrayed as a time of choice and explorations. This period in their lives can see some remaining within the religious tradition they were socialised into by their parents, while others may decide to align to a new religious tradition or move away from religion altogether.

3.2. Religious Identity

The first section of our results outlines how the student teachers in this study describe their religious identity and how that identity has been informed. In a marked departure from both the 2023 census figures and recent survey data (see Introduction), almost 95% identified as Roman Catholic. This figure is significantly higher than the 68% nationally in the census (CSO 2023) and than the 58% in Kieran and Mullally (2021). In total, almost 98% of the students said they belonged to a religious denomination. It is safe to say that the self-identification as Catholic by 94.6% of the participants is out of step with the wider trend in Irish society, where we see a significant drop in those identifying as Catholic in the census between 2016 and 2022, 78.3% and 69%, respectively, and this warrants further investigation.

3.3. Religious Influence and Family

Religious identity is very much influenced by the family; when children grow up in a family where religion is part of their lives, they are more likely to be religious themselves (Hardy and Longo 2021; French et al. 2013). In this study, c. 60% reported being influenced by their parents when it comes to religion in their lives. This is somewhat consistent with McGuckin et al. (2014), who found that 75% of young people reported that parents had an influence on their religious identity in the Irish context.

Student 1 describes howDefinitely my family influences my beliefs and my practices. My mom would be very religious … I get on really well with my mom, so whatever she does I kind of follow … she has lived a good life and she’s happy with things and she is just doing really well, so I kind of want to be like her.(Student 1)

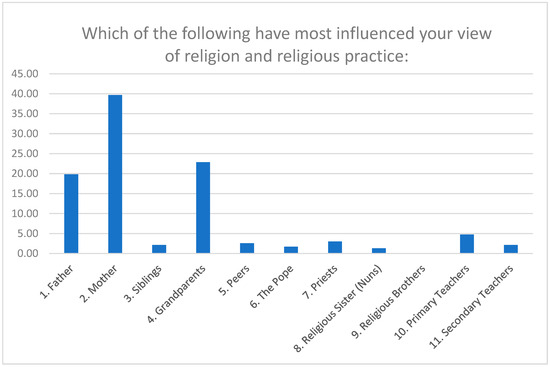

Figure 1 below shows that almost three times as many students referred to the religious influence of their mothers compared to their fathers. In keeping with the research of Byrne et al. (2019), the female influence extends to grandmothers, as Student 2 describes: ‘My mom and my grandma are really religious and it’s just important to them, so I think they just kind of made me feel it’s important to me too’.

Figure 1.

Influences on religion and religious practice.

In a society where most parents are working, many families rely on grandparents to provide additional support. The New Growing Up in Ireland Report (ERSI 2018) found that grandparents were an important part of family life for most nine-year-olds. Over two-thirds saw their grandparent(s) at least once a week and 88% had a close relationship with at least one grandparent. Francis et al. (2019) note that 90% of those who cite their religious identity as being important to them recognise that religion is also important to their grandparents and see them as vital in the passing on of faith. It is not surprising, then, that almost 25% of respondents in this study cited their grandparents as having a significant influence on their religious identity, with comments such as ‘My grandparents go to mass every day and they go every Sunday, so they always influenced me’ (Student 14).

In summary, 85% of respondents (Figure 1) identified their family as an influence on their views on religions and religious practice.

3.4. Theme 2: Images and Understandings of God

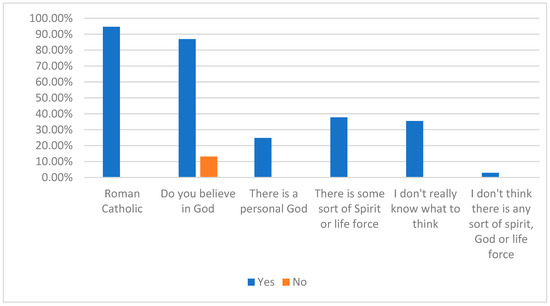

In response to the question, ‘Do you believe in God?’, 87% of students answered ‘Yes’ and 13% ‘No’.

If we place this result against the findings from Theme 1, it is interesting to note that while 87% said they believe in God, 95% of the same group said that they belonged to the Catholic denomination. In other words, c. 8% of participants say they are Catholic but do not believe in God, echoing the findings of Francis et al. (2019). They found that of the 16–19 year olds in Ireland who identified as Catholic, 44% were either uncertain that God exists or fairly sure God does not exist or completely confident that God does not exist. Our finding that 95% of participants in our survey say they are Catholic and 87% claim to believe in God is also in keeping with other surveys like this one (Bullivant 2018, p. 4). Clearly, for these participants, being Catholic is not about a question of faith or necessarily a belief in God. Perhaps it is as Inglis suggests: ‘that being Catholic is like some indelible mark that they have accepted and have no desire to change. It is literally part of what they are in the same way that they are, for example, white, male and Irish’ (Inglis 2004, p. 14).

However, in keeping with the results of Theme 1, the stated belief in God among these students is considerably higher than the national average (CSO 2023) and than other cohorts of similar age referenced earlier (see Francis et al. 2019; Kieran and Mullally 2021). Also, the number of students who say they do not believe in God (13.1%) is considerably higher than the national figure of 0.01% in the 2023 census.

3.5. Images of God

The study reveals a range of understandings and images of God: 25% of students believe that ‘There is a personal God’, while 38% opted for the category ‘There is some sort of spirit or life force’. A further 3% said ‘I don’t think there is any sort of spirit, God or life force.’ This figure is much smaller than the 13% of students who responded ‘No’ to the question, ‘Do you believe in God?’ However, at 3% it is considerably higher than the national figure of 0.01% of the population who identify as atheist (CSO 2023).

Significantly, 34.5% answered ‘I don’t really know what to think’ and 38% chose ‘There is some sort of spirit or life force’. This result (a combined 72%% of students) illustrates the vague religiosity described by Boeve (2007): while a large proportion of students identify as Catholic (94.6%), they appear to be without clarity about what or who they believe in.

Figure 2 below integrates results from Theme 1 and Theme 2 by showing the percentages of students who are Catholic and who believe in God, and offering some insight into their understandings of God.

Figure 2.

Images of God.

The data presented in Figure 2 go to the heart of the research question on the religiosity of student teachers and the implications for Religious Education in Catholic schools. We have seen earlier how ‘the mystery of God—Father, Son and Holy Spirit—is the centre of the curriculum’ (IEC 2015, p. 25). Central to CPPREC (IEC 2015) is an understanding of a personal, Trinitarian God who seeks a relationship with the human person. This relationship within God is characterised by self-giving love and a call to love one’s neighbour and care for creation.

However, only 25% of respondents in this case understand God as personal. At first glance, this suggests that the beliefs of nearly three quarters of respondents is incongruent with the understanding of God in CPPREC (IEC 2015). However, qualitative methods can clarify the statistical results, and here the qualitative data provide some interesting insights. The vast majority of interviewees, for instance, described a personal God and believed that God is interested in their wellbeing. For most, while they depicted God in masculine terms, possibly reflecting the faith of their parents/grandparents, this did not seem fully adequate to their understanding of God. The response of Student 1 is typical in this regard: ‘But as a Catholic, I suppose, growing up you were always taught that God is the man in heaven who is the Father of Jesus … I know that it’s often discussed as a he but I don’t think that’s right, that he’s a he’ (Student 1).

Some students were problematising this traditional image and using a Trinitarian framework to do so: ‘I describe God in the conventional Catholic way, like a man in the sky above everybody…I would consider God to be the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit and not just God by himself’ (Student 2). This Trinitarian description—God as Father, Son and Holy Spirit—was a theme in many responses.

The vast majority of students in the qualitative research had a sense that God was a ‘someone’, aware of them and bringing them comfort when they were in trouble: ‘I think it’s like someone who’s always watching out for you and is there when you need things’ (Student 12). This presence is to ‘give us strength in our low times’ (Student 9). In other words, whereas some of these students had opted for the category of ‘life force’ in the survey, what they described in interviews was a God of comfort—a personal God in relationship with them. Furthermore, almost half of them reached for the concept of love in their attempts to describe God, with comments such as ‘Love could be used instead of God … Like I was saying earlier, God and love I think are quite similar. To me, God is just a word, so I would use the word love or happiness’ (Student 1). For Student 10, God is ‘kind of like a state of being…more like love and kindness and respect and stuff like that, as opposed to a person with a face on, if that makes sense’. This brings to mind the work of Groome (2019), when he spoke about the advantages to faith in this new cultural and social reality of today. These students display evidence of a personally chosen faith, an expansion to one’s imaging of God and that faith must be free and freeing.

However, not all students felt this way, and some distanced themselves from belief in God. For instance, Student 11 stated: ‘If they believe in God, they can’t act how they truly want to. If there’re afraid of what God would think, something like that, I don’t know’. This view that belief in God is restrictive and based on fear was not shared among the believers in the group, none of whom saw God in this way. Their overall sense was of a personal God who wanted to comfort them when they needed it.

In short, whereas the quantitative findings indicate that most students either ‘don’t know what to think’ (34.5%) or see God as ‘some sort of spirit or life force’ (38%), the qualitative data tell a different story. The interviews reveal a sense that God is personal, relational, a ‘someone’ who cares about them, most especially when they are in need of help. This sense that God is important and helpful in their lives is very much in keeping with the Christian understanding of God in the CPPREC (IEC 2015) and the Grow in Love series.

That said, the notion of a vague religiosity spoken about earlier can be seen in some of the quantitative data. It revealed that 34.5% of first year students ‘don’t know what to think’ about God.

Given that almost 73% of the students either ‘don’t know what to think’ about God or see God as ‘some sort of spirit or life force’, it cannot be assumed that the image of God contained in the CPPREC (IEC 2015) and the Grow in Love programme makes sense or appeals to them on a personal basis. It may prove challenging for these students to understand and appreciate the depth of the Trinitarian God who is love (1 John 4:8, 16), who is a relationship of self-giving love between the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, and is revealed in the person of Jesus Christ, the face of God (Colossians 1:15). Consequently, it may be difficult for them to propose such an understanding of God to the children they teach.

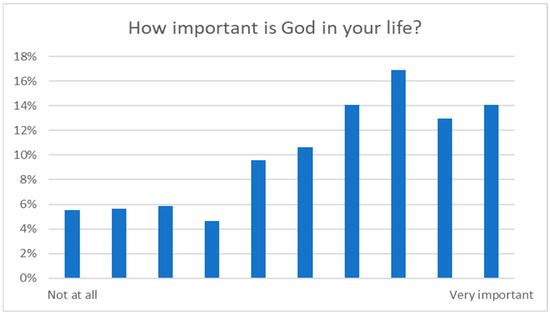

Despite this range of understandings of God, 69% of students report that God is important or very important in their lives (see Figure 3). Whatever they conceive God to be, it is something they value.

Figure 3.

Importance of God.

4. Conclusions

The Catholic school in Ireland now operates within a plural society, where religion, or certainly engaged Catholicism, while still significant to some, can no longer be presumed. The novelty of the paper lies in its presentation of the religious beliefs of first-year Initial Teacher Education students and their congruence (or lack thereof) with one of the central ideas in the Catholic Preschool and Primary Religious Education Curriculum for Ireland (IEC 2015). This paper is part of a larger study. It is not the aim of this paper to scrutinise the implications of these findings for the teaching of content. This will form part of the next stage of the project. However, the data generated from this research indicate that the proportion of students in ITE who identify as Catholic is higher than in the general population, including their own age group in the general population and on the PME programme. This identity, and the belief systems which accompany it, are influenced primarily by family, particularly the female members. Belief in God is still remarkably high among this cohort, despite the societal challenges (Taylor 2007). However, the disconnect between how some identify (95% Catholic) and belief in God (13% unbelievers) is resonant of the culturally motivated reserve to link God in definitive ways to a particular tradition (Boeve 2007).

Most students profess some of the core religious beliefs that cohere with the underpinning identity of Catholic schools and the RE they teach: they believe in God, and God is important in their lives. The qualitative data indicate that God is personal for most of the students who took part in the interviews. God is a ‘someone’ who cares for them and wants to help them, especially when times are tough. Notwithstanding the influence of family, the evidence shows many students following their own religious path without the felt need to hold a particular image of God or assume the religious beliefs of those who have gone before them. Many students gave expression to a personally chosen faith, with some looking to expand their idea of God. Groome’s concern that faith must be free and freeing (Groome 2019, p. 32) is clearly met in these instances. His insights are important here. The advantage he sees in this new reality is one of authenticity. Where faith is freely chosen, it can be communicated with authenticity. The CPPREC (IEC 2015) is clear in this regard: faith should never be imposed or coerced. Thus, ITE students are taught to propose Christian faith to children in schools, never to impose it.

However, it is significant that when it comes to their understanding/image of God, many student teachers do not know what to think (34.5%). Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the image of God contained in the CPPREC (IEC 2015) and the Grow in Love programme does not immediately cohere with their own beliefs. It may prove challenging for these students to understand and appreciate a God who is a relationship of self-giving love between the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, revealed in the person of Jesus Christ, the face of God. It may then be difficult for them to propose such an understanding of God to children in Catholic primary schools, regardless of the Grow in Love programme.

The level of uncertainty highlighted in the results is indicative of Boeve’s detraditionalisation. Understanding of God as love, and belief in God as personal and revealed in Jesus Christ, cannot be taken for granted. This, then, raises questions for the provision of teachers for Catholic primary education into the future. The Catholic school ‘above all else…will seek to ensure that every pupil will leave the school knowing, in theory and in practice…that God is love’ (Lane 2012, p. 51). Given the data outlined above, the question emerges: will there be enough teachers who understand and appreciate the religious underpinning of the Catholic school and the CPPREC (IEC 2015), so that they can adequately teach the Grow in Love programme into the future?

The findings outlined in this article pose both challenges and opportunities for the Catholic primary school sector. The teaching and learning of Religious Education in a school is a matter for the patron. The patron has the right and responsibility to ensure that its own programme is taught and taught well. Providing support for teachers of Religious Education in sustained and life-giving ways is an important first step. This means building on initial teacher education by providing ongoing, high-quality Continual Professional Development (CPD). A preservice teacher’s introduction to teaching any subject is not sufficient to carry and sustain them throughout their professional lives. Furthermore, the teaching and learning of Religious Education requires systematic evaluation. The Catholic community in Ireland needs to look to other jurisdictions dealing with similar issues for help in meeting these challenges and opportunities.

The pedagogy and appeal of Grow in Love and its warm reception among teachers (Kelly 2021) suggest the potential for high-quality Religious Education and an openness of teachers to good quality CPD. The findings of this study in terms of identity and beliefs of student teachers, and the importance of God in most of their lives, is a promising starting point for those responsible for supporting teachers in this regard. The Catholic community has been at the forefront in the design of high-quality RE programmes such as Grow in Love; it is time now to walk with the teachers they employ so they can understand, appreciate and teach them.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.O. and M.H.; methodology, D.O. and M.H.; formal analysis, D.O. and M.H.; investigation, D.O. and M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, D.O. and M.H.; writing—review and editing, D.O., M.H. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mary Immaculate College, MIREC A15-040, 19 September 2015.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data is not publicly available due to ethical restrictions—no permission was sought for this in the original ethics application.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Quantitative Questionnaire

Participant Information

Do you agree to take part in this survey?

- Yes

- No

Gender:

- Male

- Female

Age:

- 18–19

- 20–24

- 25–29

- 30–34

- 35–39

- 40–44

- 45–49

- 50–54

- 55–59

- 60+

How would you describe your geographical location?

- Urban

- Rural

How many siblings do you have? (Insert number)

European Values Survey, Religion

Q 1 Do you belong to a religious denomination?

- Yes

- No

Q 2 Which religious denomination do you belong to?

- Roman Catholic

- Protestant

- Free church/ non-conformist/ evangelical

- Jew

- Muslim

- Hindu

- Buddhist

- Orthodox

- None of the above

Q 3 Were you ever a member of (another) religious denomination?

- Roman Catholic

- Protestant

- Free church/non-conformist/evangelical

- Jew

- Muslim

- Hindu

- Buddhist

- Orthodox

- None of the above

Q 4 Apart from weddings, funerals and christenings, about how often do you attend religious services these days?

- More than once a week

- Once a week

- Once a month

- Only on specific holy days

- Once a year

- Less often

- Never, practically never

Q 5 Apart from weddings, funerals and christenings, about how often did you attend religious services when you were 12 years old?

- More than once a week

- Once a week

- Once a month

- Only on specific holy days

- Once a year

- Less often

- Never, practically never

Do you personally think it is important to hold a religious service for any of the following events?

Q6 Birth

- Yes

- No

Q7 Marriage

- Yes

- No

Q8 Death

- Yes

- No

Q 9 Independently of whether you go to church or not, would you say you are:

- A religious person

- Not a religious person

- A Convinced atheist

FOR THOSE BELONGING TO A CHURCH OR A RELIGIOUS COMMUNITY; ASK YOUR CHURCH/RELIGIOUS COMMUNITY

Generally speaking, do you think that your church is giving, in your country, adequate answers to …

Q 10 The moral problems and needs of the individual

- Yes

- No

Q 11 The problems of family life

- Yes

- No

Q 12 People’s spiritual needs

- Yes

- No

Q 13 The social problems facing our country today

- Yes

- No

FOR THOSE NOT BELONGING TO A CHURCH OR RELIGIOUS COMMUNITY ASK: THE CHURCHES

Generally speaking, do you think that the churches are giving, in your country, adequate answers to …

Q 14 The moral problems and needs of the individual?

- Yes

- No

Q 15 The problems of family life?

- Yes

- No

Q 16 People’s spiritual needs?

- Yes

- No

Q 17 The social problems facing our country today?

- Yes

- No

Do you believe in:

Q 18 God?

- Yes

- No

Q 19 Life after death?

- Yes

- No

Q 20 Hell?

- Yes

- No

Q 21 Heaven?

- Yes

- No

Q 22 Sin?

- Yes

- No

Q 23 Do you believe in re-incarnation; that is, that we are born into this world again?

- Yes

- No

Q 24 Which of these statements comes closest to your beliefs?

- There is a personal God

- There is some sort of spirit or life force

- I don’t really know what to think

- I don’t really think there is any sort of spirit, God or life force

Q 25 I have my own way of connecting with the Divine without churches or religious services.

- Not at all

- ……

- ……

- ……

- Very much

Q 26 Whether or not you think of yourself as a religious person, how spiritual would you say you are, that is, how strongly are you interested in the sacred or the supernatural?

- Very interested

- Somewhat interested

- Not very interested

- Not at all interested

Q 27 These are statements one sometimes hears. Please choose the statement that best describes your view.

- There is only true religion

- There is only one true religion, but other religions do contain some basic truths as well

- There is not one true religion, but all great world religions contain some basic truths

- None of the great religions have any truths to offer

Q 28 How important is God in your life?

- not at all important

- very important

Q 29 Do you get comfort and strength from religion?

- Yes

- No

Q 30 Do you take some moments of prayer, meditation or contemplation or something like that?

- Yes

- No

Q 31 How often do you pray to God outside of religious services? Would you say …

- Every day

- More than once a week

- Once a week

- At least once a month

- Several times a year

- Less often

- Never

Supplementary Questions

Which of the following best describes your primary school?

- Denominational: Catholic

- Denominational: Church of Ireland

- Denominational: Muslim

- Denominational: Jewish

- Denominational: Quaker

- Multidenominational: Educate Together

- Multidenominational: Community National Schools (VEC)

- Multidenominational: Steiner

Which of the following best describes your post-primary school?

- Denominational: Catholic

- Denominational: Church of Ireland

- Multidenominational: Educate Together

- Multidenominational: Community School (VEC)

- Multidenominational: Comprehensive School

- Multidenominational: Community Colleges

- Multidenominational: Education & Training Board School

Which of the following have most influenced your view of religion and religious practice?

- Father

- Mother

- Siblings

- Grandparents

- Peers

- The Pope

- Priests

- Religious Sister (Nuns)

- Religious Brothers

- Primary Teachers

- Secondary Teachers

Which of the following have most influenced your view of religion and religious practice?

- Media

- Social Media (Blogs, Twitter, Facebook)

- Church

- Parish

- School

- Charity Organizations (St. Vincent de Paul, Trocaire)

- Music

- Films/Television

- Literature

WOULD YOU BE WILLING TO VOLUNTEER AND MEET WITH A RESEARCHER BETWEEN NOW AND CHRISTMAS, TO HAVE A CONVERSATION ABOUT THESE QUESTIONS? IT WILL BE COMPLETELY CONFIDENTIAL AND FOR ABOUT 20 TO 30 MINUTES. THE AIM IS TO GO BELOW THE SURFACE OF THESE QUESTIONS AND HEAR THE STUDENTS’ VOICES AND EXPERIENCES IN THESE MATTERS.

Appendix B

Semi-Structured Focus-Group Questions

Note: Questions will be mainly influenced by data gathered during phase 1. However, these are questions that will appear on the schedule.

If you are part of a religious denomination, in what ways do you practice your faith and why?

- How would you describe God?

- Where do you experience God?

- In what ways do you experience God?

- Who or what would you say influences your beliefs about religion and your religious practices?

References

- Barron, Robert. 2007. What is the Trinity? In Faith Clips. DVD. Des Plaines, IL: Word on Fire. [Google Scholar]

- Behaviour & Attitudes. 2016. RTE/Behaviour & Attitudes 2016 General Election Exit Poll. Dublin: Behaviour & Attitudes. [Google Scholar]

- Boeve, Leiven. 2007. God Interrupts History: Theology in a Time of Upheaval. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2013. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bullivant, Stephen. 2018. Europe’s Young Adults and Religion: Findings from the European Social Survey (2014–16) to Inform the 2018 Synod of Bishops. London: Benedict XVI Centre for Religion and Society, St. Mary’s University, London and Institut Catholique de Paris. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, Gareth, Leslie Francis, Ursula McKenna, and Bernadette Sweetman. 2019. Exploring the personal, social and spiritual worldview of male adolescent atheists within the Republic of Ireland: An empirical enquiry. In Religion and Education, The Voices of Young People in Ireland. Edited by Gareth Byrne and Leslie Francis. Dublin: Veritas, pp. 247–83. [Google Scholar]

- Catholic Church. 2000. Catechism of the Catholic Church. Washington, DC: Bishops Conference. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Louis, Lawrence Mannion, and Keith Morrison. 2011. Research Methods in Education, 7th ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John W., and Vicki L. Plano Clark. 2011. Designing and Conducting Mixed-Methods Research, 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- CSO (Central Statistics Office). 2016a. Census of Population: Profile 8: Irish Travellers, Ethnicity, Religion. Available online: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-cp8iter/p8iter/ (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- CSO (Central Statistics Office). 2016b. Census of Population: Profile 7: Migration and Diversity. Available online: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-cp7md/p7md/p7anii/ (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- CSO (Central Statistics Office). 2023. FY030 Actual and Percentage Change in Population Usually Resident and Present. Available online: https://data.cso.ie/ (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Cullen, Sandra. 2019. Turn up the volume: Heaver what the voices of young people are saying in education. In Religion and Education, The Voices of Young People in Ireland. Edited by Gareth Byrne and Leslie Francis. Dublin: Veritas, pp. 271–281. [Google Scholar]

- Davie, Grace. 2015. Religion in Britain, A Persistent Paradox. London: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education. 2022. Primary Schools 2021–2022. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/en/collection/primary-schools/#20222023 (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Department of Education. 2023. Education Indicators for Ireland. February. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/pdf/?file=https://assets.gov.ie/246552/96fc2eb5-b7c9-4a17-afbc-de288a471b3f.pdf#page=null (accessed on 31 September 2023).

- ERSI. 2018. Growing Up in Ireland: Key Findings—Cohort ’08 at ’09 Years Old. Available online: https://www.esri.ie/system/files/publications/SUSTAT67.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Flick, Uwe. 2014. An Introduction to Qualitative Research, 5th ed. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, Leslie, Gareth Byrne, Bernadette Sweetman, and Gemma Penny. 2019. Growing up female and Catholic in the Republic of Ireland and in Scotland: The intersectionality of religious identity, religious saliency, and nationality. In Diversity and Intersectionality: Studies in Religion, Education and Values. Edited by Jeff Astley and Leslie Francis. Oxford: Peter Lang, pp. 67–99. [Google Scholar]

- French, Doran C., Nancy Eisenberg, Julie Sallquist, Urip Purwono, Ting Lu, and Sharon L. Christ. 2013. Parent-adolescent relationships, religiosity, and the social adjustment of Indonesian Muslim adolescents. Journal of Family Psychology 27: 421–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groome, Thomas. 2019. Faith for the Heart, A ‘Catholic’ Spirituality. New York: Paulist Press. [Google Scholar]

- Halík, Tomáš. 2015. Church for the Seekers. In A Czech Perspective on Faith in a Secular Age. Edited by Tomáš Halík and Pavel Hošek. Washington, DC: The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy, pp. 125–33. [Google Scholar]

- Halter, Christopher. 2014. The PSPP Guide (Expanded Edition): An Introduction to Statistical Analysis. Melbourne: Creative Minds Press Group. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, Sam A., and Gregory S. Longo. 2021. Developmental Perspectives on Youth Religious Non-Affiliation. In Empty Churches: Non-Affiliation in America. Edited by James L. Heft and Jan E. Stets. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 135–71. [Google Scholar]

- Heinz, Manuela, Elaine Keane, and Kevin Davison. 2023. Gender in initial teacher education: Entry patterns, intersectionality and a dialectic rationale for diverse masculinities in schooling. European Journal of Teacher Education 46: 134–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hošek, Pavel. 2015. Introduction: Towards a kenotic hermeneutics of contemporary Czech culture. In A Czech Perspective on Faith in a Secular Age. Edited by Tomáš Halík and Pavel Hošek. Washington, DC: The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Inglis, Tom. 2004. Catholic Identity, Habitus and Practice in Contemporary Ireland. Proposed ISSC Working Paper. Available online: https://www.ucd.ie/geary/static/publications/workingpapers/isscwp2004-13.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Ireland. 1998. Education Act. Dublin: Stationery Office. [Google Scholar]

- Irish Episcopal Conference. 2015. Catholic Preschool and Primary Religious Education Curriculum for Ireland. Dublin: Veritas. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, Óisséne. 2021. An Exploration of the Attitudes of Primary School Teachers Towards the Teaching of Religious Education in Catholic Primary Schools in Ireland. Master’s thesis, Marino Institute of Education, Dublin, Ireland. Available online: http://www.tara.tcd.ie/bitstream/handle/2262/97773/%C3%93iss%C3%A9ne%20Kelly%20thesis.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- Kieran, Patricia, and Aiveen Mullally. 2021. Beyond Belief? Pre-Service Teachers’ Perspectives on Teaching RE in Ireland. Journal of Religious Education 69: 423–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieran, Patricia, and John McDonagh. 2021. The centre cannot hold: Decolonising the RE curriculum in the Republic of Ireland. British Journal of Religious Education 43: 123–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, Dermot. 2012. Catholic primary education and the primary school in the twenty first century. In Catholic Primary Education, Facing New Challenges. Edited by Eugene Duffy. Dublin: Columba Press. [Google Scholar]

- McGraw, Sean, and Jonathan Tiernan. 2022. The Politics of Irish Primary Education, Reform in an Era of Secularisation. Oxford: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- McGuckin, Conor, Christopher Alan Lewis, Sharon Cruise, and John Paul Sheridan. 2014. The Religious socialisation of young people in Ireland. In Education Matters: Readings in Pastoral Care for School Chaplains, Guidance Counsellors and Teachers. Edited by James O’Higgins Norman. Dublin: Veritas, pp. 228–45. [Google Scholar]

- Meehan, Amalee, and Derek Laffan. 2021. Inclusive second level Religious Education in Ireland today: What do teachers say? Journal of Religious Education 69: 439–51. [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, Daniel. 2017. Going below the surface of Grow in Love, Some of the theological presuppositions in the new Catholic religious education primary programme in Ireland. In Does Religious Education Matter? Edited by Mary Shanahan. London: Routledge, pp. 78–86. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, Chris, Marie O’Rourke, Elaine Mahon, Gene Butler, G. Ann Bracken, and Amanda Smith. 2019. Grow in Love, Sixth Class. Dublin: Veritas. [Google Scholar]

- Pope Benedict XVI. 2006. God is love, Deus Caritas Est. Washington, DC: USCCB Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ream, Geoffrey L., and Ruth C. Savin-Williams. 2003. Religious Development in Adolescence. In Backwell Handbook of Adolescence. Edited by Gerald L. Adams and Michael D. Berzonsly. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, John-Paul. 2022. Catholic Teacher Formation in the Republic of Ireland. In Formation of Teachers for Catholic Schools. Edited by Leonard Franchi and Richard Rymarz. Singapore: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, Anselm, and Juliet Corbin. 1990. Basics of Qualitative Research. Newbury Park: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Charles. 2004. Modern Social Imaginaries. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Charles. 2007. A Secular Age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tuohy, David. 2013. Denominational Education and Politics, Ireland in a European Context. Dublin: Veritas. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Max. 1965. The Sociology of Religion. London: Methuen & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Werbner, Pnina. 2010. Religious Identity. In The Sage Handbook of Identities. Edited by Margaret Wetherell and Chandra Talpade Mohantt. London: Sage, pp. 233–57. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).