Abstract

Scholars have for some years hypothesized a “new visibility” of religion, so that a relevant role in the publicization of religion is played by the media. However, while the public visibility of religion in the media has recently become a topic of great interest at the international level, in Italy, the literature on this topic is quite scarce. It is of particular interest in Italy due to the central role played by the Catholic Church, which, despite the changed socio-political context and the transformations of the media system, does not seem to have lost its capacity to intervene publicly. Therefore, this study intends to fill this gap through a longitudinal analysis of the coverage of the Catholic Church in the main Italian print newspapers in the last 17 years (2005–2021). In total, 202,788 articles were collected and analysed using a content analysis. Results show that, in Italy, we cannot speak of a greater visibility of religion, in particular of the Catholic Church today in print press than in the past, nor of a uniformity with respect to the way in which is spoken about it in terms of issues and religious actors.

1. Introduction

The issue of the visibility of religion in the public sphere is now more central than ever. All over the world, we are still experiencing a strong and lively presence of religion, that is capable of playing a central role in the major debates that animate our democracies and the life of other political systems. The increased sense of uncertainty of the historical moment we are living through, characterised by new and old wars and populist impulses, seems to have provided even more oxygen to the debate on the role played by religion in our societies. We should bear in mind the role of the head of the Orthodox Russian Church and, more recently, of Pope Francis in the Russian invasion of Ukraine, or the use of religious symbols by rightist populist political actors in many countries (Arato and Cohen 2018; DeHanas and Shterin 2018; Hoelzl 2020; Marchetti et al. 2022).

In this regard, the literature has been hypothesising for some decades now of the return of religion to the public sphere in which the media play an important role in increasing this visibility over time. But can the same be said for Italy? While the public visibility of religion within the media became a topic of great interest internationally (Hoover 2006; Knott et al. 2013; Hjelm 2015; Cohen 2018), the literature on this topic in Italy is rather lacking. In fact, the literature lacks longitudinal studies over time that allow for an in-depth investigation of the visibility of religion in the Italian public debate. The only volume that has systematically analysed religious information in the Italian press dates back to more than thirty-five years (Tentori 1986).

The contributions in the volume edited by Tentori (1986) showed how writing about religion in Italy meant talking about Catholicism. Even today, in fact, if we look at the data concerning religious phenomena in Italy, despite an increase in religious pluralism as a consequence, in particular, of migratory phenomena, the majority of the population continues to be Catholic (Garelli 2020), even though being Catholic for Italians has in recent decades taken on a characterisation that is increasingly more cultural than purely of faith (Garelli 2014).

The study therefore starts from the same assumption that in Italy it is still the Catholic Church that monopolises the discourse on religion, even after so many years and in a profoundly changed social and religious context. At the same time, a study focused on Italy must necessarily consider the changing place of religion in contemporary society (Davie and Wilson 2020). In addition, the research cannot avoid considering the characteristics that make Italy a unique case. These include the presence on its territory of the Pope and the Holy See, the State–Church relations sanctioned by the Concordat, the diffusion and rooting of the institution throughout the country and the role it plays in favour of the weaker segments of the population, and the plurality of religious orders, movements, and Catholic associations, but also the presence and central role of the Catholic media in the media landscape. For all these reasons, the Catholic Church in Italy exercises a traditionally stable power of externalisation; it has always interacted with politics and habitually intervenes in the issues on the agenda, updating values that belong to the Catholic cultural and value substratum rooted in the country (Marchetti 2011). Therefore, this study aims to investigate the role of religion in the public debate by analysing the coverage of the Catholic Church by the Italian press over a period of time (17 years) that is sufficiently broad to capture continuities and differences. The choice to analyse the print press is due to the availability of materials covering a sufficiently wide time span to be able to capture continuities and differences in the coverage of the Catholic Church, and because it continues to be important in reading the dynamics of the Italian public debate.

The study analyses the coverage of the Catholic Church in Italy by the main national newspapers, trying to detect (a) the trend of its presence in the 17 years considered, (b) what types of Catholic Church actors have received more attention over time, and (c) the issues on which the Catholic Church is more legitimised to intervene by the media. Therefore, this study attempts to answer three main research questions:

RQ1:

Has the Catholic Church’s presence in the public debate increased or decreased over time?

RQ2:

Which Catholic Church actors have received the most attention over time? Are there changes over time?

RQ3:

On which issues has the Catholic Church been most legitimised to intervene? Are there changes over time?

The hypothesis (HP) from which the research work starts is as follows: considering the specific characteristics of the Italian context and in particular the relevant role of the Catholic Church, in Italy, we cannot speak of a greater visibility of religion, and in particular of the Catholic Church, today compared to the past, but speak rather of a transformation of its presence in the public discourse. However, we hypothesise a shift in the public presence of the Catholic Church in the media because there have been numerous changes in the media system, the Italian political landscape, the Catholic Church institution, and population’s religious sentiment during the period under examination.

2. The State of Research

For some years, scholars from various disciplines have been talking about a return of religion to the public sphere (Meyer and Moors 2006; Butler et al. 2011; Rovisco and Kim 2014; Schewel and Wilson 2020). Referring to a debate opened by Casanova (1994, 2008), religions therefore continue to have a public role (public religions). By this, we mean the ability of religious institutions to influence the main issues that challenge today’s societies and their governments, raising questions and proposals on the basis of their own systems of values and moral codes. The secularization processes that have taken place in recent decades (Norris and Inglehart 2007; Casanova 2011; Habermas 2018) have not inhibited the ability of religious institutions to participate—and therefore to be legitimized to do so—in the public debate, imposing their own issues or frames to the themes at the centre of the discussion. In this sense, the interest is more broadly directed to the understanding of the place of religion in the public sphere by investigating the processes that lead to its legitimisation (Axner 2015; Lövheim and Lindermann 2015). Churches have always played a fundamental role within societies, assisting the actions of local and national governments in the welfare, as well as acting as socialisation agencies (Norris and Inglehart 2007). All these elements have legitimised religious institutions—individually or collectively—to have a voice in the debate, sometimes opposing governments on ethical and moral issues and carrying out advocacy actions (Lövheim 2019).

An important role in this process is certainly played by the media, the primary arena for the visibility of religion, as well as of different political/economic/societal actors and the most important issues at the centre of the public sphere. The relationship between religion and the media has therefore become an increasingly investigated research topic in the last 15 years (Hoover 2006; Campbell 2010; Hjelm 2015; Cohen 2018; see also the recent article published in this journal by Mihai (2023)). A part of this literature supports an increase in quantitative terms of the presence of religion in the media starting from the very beginning of the millennium (Knott et al. 2013; Lövheim and Lindermann 2015). According to this line of research, the increased visibility of religion (which does not necessarily correspond to its greater incidence in matters of public interest) is due to, at least in part, the role of the media that publishes an increasing number of “religion stories”, i.e., news focused on various dimensions related to religion and the Churches (Hjelm 2015). Central to all these studies are the concepts of publicization of religion (Herbert 2011), regarding the proliferation of religious symbols and discourses in the public sphere, and of the mediatization of religion (Hjarvard 2008, 2012), according to which religion is always more linked—and sometimes “subdued”—to a media logic (Altheide and Snow 1979).

However, the hypothesis of increased visibility is mostly based on studies focused on countries that are culturally distant from the Italian case (Knott et al. 2013; Hjelm 2015; Lövheim and Lindermann 2015). An attempt to consider Italy was made by Lövheim (2019) who proposed a synthesis of various studies aimed at investigating the increased visibility of religion in the media, including in Italy, through the research conducted by Ozzano and Giorgi (2016) that focused on the religion–politics relationship and in particular on ethical issues. Lövheim (2019) drew several studies focused on the analysis of the coverage of religion in different European countries, analysing the main issues on which different religions are usually covered by the media and summarising the results in three main frames, i.e., of conflict, of culture, and of constitutional rights.

With regard to the Italian case, the study by Marchetti and colleagues (2019) that analysed the coverage of the Catholic Church more generally in the main print media within a year partly confirmed the picture elaborated by Lövheim (2019), underlining how the Catholic Church in Italy is legitimised by the media to intervene in the public debate when it takes the floor on controversial topics under discussion that imply an ideological demarcation between opposites (e.g., pro-immigration/anti-immigration) or that touch on fundamental ethical–moral issues such as the defence of life (abortion and euthanasia). The research also showed how the Catholic Church carried out advocacy work for the weakest (the poor, the immigrants, and the persecuted), giving a voice to the demands of the unrepresented and proposing solutions to problems that often involve a high degree of divisiveness among political actors.

However, understanding all these dynamics would not be possible without considering the characteristics and transformations of the media ecosystem during the 17 years under review. The conflict and the dynamics between opposing ideological positions and the controversial nature and divisiveness of the issues that we have seen characterise the main issues on which the Churches are traditionally—and not only in Italy—called upon to intervene and coincide perfectly with the newsworthiness criteria elaborated by the media literature that explain why one fact or event is more newsworthy than another (Gans 1979, 2011). Then, the dynamics of agenda-building processes help consider the different dimensions that affect the structuring of the public arena: the plurality of actors, the interaction and competition between them as the driving force behind the formation of public opinion and democratic processes, the culture of organised social groups, and the presence of different media (Cobb and Elder 1975; Marini 2007). In such context, within this competitive arena, the Catholic Church is one of the actors that, among others, is active in supporting issues of its interest and affirming particular worldviews.

3. Data and Method

For the research, all the articles published during the period between 1 January 20051 and 31 December 2021 by four of the main Italian newspapers—selected based on their circulation and political orientation in their print version (Corriere della Sera, la Repubblica, il Giornale and La Stampa)—were collected. Articles were selected according to some keywords (at least one of 38) that appeared either in the title or in the text2.

A total of 202,788 articles were published by the four selected newspapers and collected through the Factiva—Dow Jones3 and Volopress4 databases. The number of articles referring to the Catholic Church was subsequently standardised with regard to the total number of articles published on all topics by the considered newspapers, in order to take into account the changes in the newspapers’ structure that occurred over the seventeen years under consideration.

The entire material collected was then subjected to a content analysis using QDA Miner5, a programme for the qualitative analysis of computer-assisted texts, and its quantitative component WordStat6, a text mining tool capable of identifying the most recurrent themes, subjects, and trends within a corpus of articles. The unit of analysis consists of each individual article published by the selected newspapers during the period under study. The analysis of the most present church actors in the journalistic coverage was carried out by means of the Named Entities Analysis, i.e., a function of WordStat that makes it possible to identify, on the basis of algorithms, the recurrence of proper names of persons, places, organisations, or acronyms. Based on this first phase, lists of ecclesial actors were created (ad hoc dictionaries) and diversified according to the different years taken into consideration, which considered the internal changes within the church institution and the alternation of its leadership (the Popes, the Italian Bishops’ Conference presidencies, the Vatican Secretaries of State, etc.). For this reason, a total of seven different dictionaries were drawn up and applied to the analysis in such a way that a person who held one role in one year and another in the following year is placed differently in the relevant groups of actors7.

For the detection of topics, a Topic Modelling Analysis was carried out, which allows the most important topics within a given corpus to be extracted using WordStat. The main statistical procedure used for topic extraction is factor analysis. The automatically extracted topics were then manually organised to verify the correct attribution of words and phrases to specific topics and to aggregate the topics that recurred more than once. Due to the large time span, a substantial number of themes were detected, several of them confined to short time intervals. In order to detect the main issues on which the Catholic Church was covered and to help understand their development over the years, only those topics that recurred the most over time were then selected.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. The Decrease of the Presence of the Catholic Church in the Italian Daily Press

The frequency of publication of articles containing references to the Catholic Church over time (Table 1) makes it possible to answer the first research question that prompted this study (RQ1): has the Catholic Church’s presence in the public debate increased or decreased over time?

Table 1.

Articles published by the four selected newspapers from 2005 to 2021 (a.v.) *.

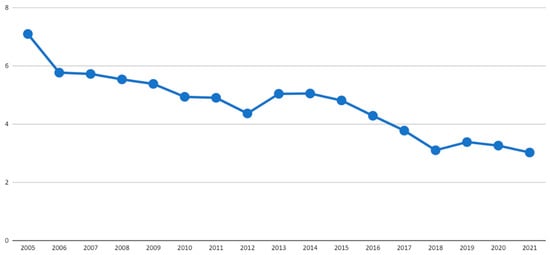

Even at first glance, the decrease in the presence of the Catholic Church in the Italian press over time is evident, confirming our initial hypothesis. However, this decrease in the years 2020–2021 was undoubtedly influenced by the attention that the newspapers paid to the issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic, which inevitably led to a compression of the space dedicated to other topics, and the constant negative trend over time remains particularly evident even if we do not consider the two pandemic years (Table 1). In order to exclude the possible interference of other factors in the analysis of coverage—such as variations in the foliation and format of newspapers over time—a standardisation of the number of articles featuring the Catholic Church in relation to the total number of articles published by the same newspapers was then carried out, which basically confirmed a reduction in the space reserved over time by the Italian press for the Catholic Church (Figure 1). Thus, the data appear to contrast the findings of other studies, according to which the presence of religion in the media has increased in quantitative terms over the last 20 years (Knott et al. 2013; Lövheim and Lindermann 2015).

Figure 1.

Percentage of articles dedicated to the Catholic Church out of the total number of articles published per year by all newspapers considered (2005 *–2021).

The reasons for a decline of this kind may be several and are not easy to identify. Possible explanations for the reduction in the Catholic Church’s presence in the considered newspapers can be sought in changes in the media ecosystem and in the editorial choices of newspapers that have seen a significant decrease in the number of their readers. Print newspapers readers are becoming more cultured and interested in political events. It is possible that the written press has become increasingly “targeted” towards a more politically socialised public over time, reducing the space for intervention by “non-political” actors. At the same time, it is possible that newspaper coverage of the Catholic Church has shifted online on the websites of newspapers. Furthermore, there have been many factors of change even within the “catholic world” that could be determined by the different communication strategies of the Catholic Church (Golan and Martini 2022). In this regard, we have witnessed the succession of different pontificates including a resigning pontiff, the alternation of positions at the top of the Italian Bishops’ Conference, the numerous reform processes, such as the one concerning Vatican communication in 2015, and, finally, changes in the religious sentiment of the population (Garelli 2020). These changes may have resulted in a shift in the attention that journalists pay to the Catholic Church and ecclesial actors over time.

4.2. The Catholic Church Actors That Have Received the Most Attention over Time

Turning now to the second research question (RQ2) concerning the Catholic Church actors who have received the most attention over time, Table 2 shows the coverage devoted to the different actors of the Catholic Church in the 17 years under consideration. Without too many surprises, it is mainly the ecclesiastical leadership that is particularly newsworthy: Pope, cardinals, bishops, and the Vatican. The hierarchical level of the actors involved continues to be a news-value determining a greater journalistic coverage (Galtung and Ruge 1965), on the basis of the “hierarchy of credibility” (Becker 1967) whereby journalists tend to favour those sources considered to be the best known and reliable.

Table 2.

Catholic Church actors’ coverage on total articles per year (%) **.

It is easy to imagine that the Pope is the most present actor in the national newspapers. However, it is interesting to see how his coverage changes over time. From a higher coverage in 2005 (39%), the year of the death of John Paul II and the inauguration of Benedict XVI, the coverage decreases in the years 2006–2012 (from 32.3% to 27.1%) to the point that in some time intervals the references made to bishops are higher than those made to the Pope (in 2010, they reach 32.5% compared to 27.5% for the Pope). In 2013, the highest value is recorded when we consider the Pope’s 43.7% and the Pope emeritus’s 19.6%. With the exception of 2013, the coverage of Pope Francis remains high with a considerable gap compared to the other ecclesial actors (45.5% in 2015), and this difference mostly constant over time. This leads to the conclusion that despite the newsworthiness traditionally experienced by the leader of the Catholic Church, the effect of personalisation of the figure by Pope Francis and also his popularity and appreciation outside the “catholic world” are noticeable8. The process of personalisation (Mazzoleni and Schulz 1999) and leadership (Mazzoleni 2012) traced in other contexts by the literature on communication—first and foremost, in the political sphere—is also evident in the Catholic Church’s presence in today’s public debate in which Pope Francis seems to centralise attention on himself today more than yesterday.

The presence of dioceses, priests, parishes, religious orders, movements, and Catholic associations is noteworthy, albeit with lower references made than those recorded for Catholic Church leaders. Particularly interesting is the presence of the local Catholic Church represented by priests and parishes in the coverage of newspapers with national distribution. Despite the fact that these two types of actors are referenced to at a lower rate than those belonging to the highest levels of the ecclesiastical hierarchy over the entire period under consideration, it is interesting to observe the increase in their references in the last two years (2020 and 2021) characterised by the COVID-19 pandemic. The coverage of priests and parishes increases from 2019 to 2021 by approximately four percentage points. There seem to be two reasons for this attention: (1) the interest in a consequence of the liturgy resulting from the restrictions imposed for containing COVID-19 infections; and (2) the role played by the local Catholic Church in the pandemic emergency in which parish priests found themselves on the front line to manage many different aspects of the crisis and, in particular, to serve a support function for the weakest segments of the population. We had already highlighted the Catholic Church’s proximity to the last—the ‘last’ being immigrants (Marchetti et al. 2019). It is the Catholic Church’s commitment to social work that, in times of extreme emergency, finds a place in the pages of the newspapers, confirming the newsworthiness of the “face” of the Catholic Church committed to social work and assistance to the most fragile (Norris and Inglehart 2007).

4.3. The Main Issues on Which the Catholic Church Has Been Most Legitimised to Intervene

Turning to the third research question (RQ3) about the topics on which the Catholic Church was most legitimised to intervene by the Italian press, Table 3 shows the main topics together with their description. With the exception of the “COVID-19” topic which, as it is easy to guess, was detected in conjunction only in the last few years of analysis (2020–2021), and all the other themes proved to recur cyclically over time, confirming their recurring representation of the Catholic Church by the printed press. In other words, the topics that will be explored here are issues on which the Catholic Church has traditionally been empowered by the press to intervene (Tentori 1986; Lövheim 2019; Marchetti et al. 2019).

Table 3.

Main topics and their description.

The data that emerged in the study of the issues on which the Catholic Church was most covered as coherently fit within the framework previously elaborated by scholars (Ozzano and Giorgi 2016; Lövheim 2019; Marchetti et al. 2019). As this study also confirms, religious institutions are legitimised by the media to intervene when they speak out on issues at the centre of public debate, in particular, on divisive and polarising issues. Looking at Table 3, we can see that there are topics related to morality and, within them, there are issues related to the “world of life and death” (Ozzano and Giorgi 2016; Marchetti et al. 2019) such as the topics of “Bioethics” and “Family and civil unions”; topics consistent with the conflict frame (Lövheim 2019) such as “Wars and crisis situations” and “Islam and interreligious dialogue”; topics on which the Catholic Church carries out an advocacy action towards the weakest (Marchetti et al. 2019) such as the topics of “Immigration” and “Social Issues”, and issues concerning the public role of religion and religious institutions in a secular state (Lövheim 2019) such as the topic of “Secularism” and also of “The catholic vote”.

Table 3 shows an in-depth overview of the topics, organized as follows: ethical issues (“Bioethics” and “Family and civil unions”); societal matters (“Immigration”, “Social issues”, and “COVID-19”); internal religious issues (“Liturgical and faith issues” and “Catholic Church events”); international issues (“Diplomatic relations”, “Wars and crisis situations”, and “Interreligious dialogue”); “Scandals”; and Catholic Church–politics relationships (“Secularism” and “Catholic vote”).

Table 4 helps to explore the development of the 13 topics over the 17 years under analysis. First of all, the data in Table 4 show how attention garnered by the Catholic Church is increased in conjunction with certain central debates in the political and democratic life of our country in which the Catholic Church has intervened, supporting its position in line with its own universe of values (see “bioethical issues” and “family and civil unions” topics). In this study, the former topic includes all the articles that call into question issues pertaining to the world of life and death, such as euthanasia, abortion, assisted fertilisation, the use of stem cells, or surrogate motherhood. The second topic refers instead to the debates concerning family issues, divorce, civil unions and, more recently, the sphere of LGBTQ+ rights. Both topics rely on a common ground which is the respect for catholic morality. The trend of the two topics presented in Table 4 confirms how the voice of the Catholic Church has been newsworthy in correspondence with the great debates that have spread in Italy in recent years: from 2005 (27.8%), the year in which cardinal Ruini (at the time, the president of the Italian Bishops’ Conference) publicly supported abstentionism in the referendum vote on assisted fertilisation, to 2009 (16.2%), and then the Church’s voice reappears in recent years from 2016 (11.4%) to 2020 (9.4%) in conjunction with the renewed debates on bioethics. Moreover, its coverage of these issues is also favoured by the intervention of its actors on specific cases at the national and the international levels (e.g., the case of Charlie Gard9). The issues pertaining to the “defence of the world of life” that have focused the press’s attention on the positions of the Catholic Church over the last 17 years are entirely consistent with the themes identified by Casanova (1994, 2008) that legitimise the public role of religions, as also pointed out by Ozzano and Giorgi (2016) and Marchetti and colleagues (2019) for the Italian case. These issues are closely linked to the symbolic cultural universe represented not only by the Catholic Church, but by religions in general, which view their role to be of recognised defenders on this issue (Lövheim 2019). At the same time, these are also highly divisive issues in the coverage of this topic, and the emphasis is on the divergent positions of the actors in the field and the clash that this generates. The same is applicable for the topic “Family and Civil Unions” on which newspapers’ attention is focused at the same time as on the main legislative proposals on the matter (with values of 49.2% in 2007 and 39.9% in 2016, Table 4).

Table 4.

Trend of the main topics by year (%) *.

The results also confirm the importance of the major events of the Catholic Church. As Table 4 shows, the topic “Church events” is particularly recorded in conjunction with the two changes to the papal throne: in 2005 with the election of Pope Benedict XVI (51.7%) after the death of Pope John Paul II, and in 2013, with the resignation of Pope Benedict XVI and the election of Pope Francis (30.1%). The advent of a new pontiff is the perfect media event (Dayan and Katz 1992; Guizzardi 1986) because of the high rituality with which it is characterised. It is an event of historic significance, which the world’s media followed live and journalists reported on in detail. In addition to the election of the popes, the newspapers also recounted other events that marked the calendar of the Catholic Church in the years taken into consideration (such as the World Youth Days, in particular that of 2005, or the Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy 2015–2016 when the topic is present in 29.8% and 10.4% of the articles analysed, respectively), or the prayer of Pope Francis whose image became iconic at St. Peter’s Square that was empty due to COVID-19 on 27 March 2020, followed by millions of people locked in their homes because of the virus.

Furthermore, there are topics that characterise both pontificates, that of Pope Benedict XVI and that of Pope Francis. In fact, the analysis of the last 17 years of media coverage makes it possible to analyse roughly the same number of years for each pontificate, favouring comparison. In particular, some topics are present only—or in any case predominantly—in correspondence with one or the other pontificate, confirming a characterisation of the action of the two pontiffs on specific and different issues. Proceeding in order, in the case of Pope Benedict XVI in the years from 2006 to 2012, there was a more important presence of the topic “Liturgical and faith issues” (with a peak in 2007—17.4%), which after 2013 almost completely disappeared. This topic refers to issues purely internal to the Catholic Church and to the sphere of faith, prayer, and liturgy (e.g., the debate related to the reintroduction of the Latin Mass, in reference to the precepts of Catholic doctrine, etc.). Theological, faith, and liturgical issues are presented in the press as the prerogative of a pontiff, Pope Benedict XVI, formerly Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, who has been referred to as the “theologian pope” since his election. On the other hand, the case of Pope Francis is different. Judging by the data of the study, his pontificate was instead characterised by two topics that seem to indicate the openness of the Catholic Church—a Church that uses the tools of diplomacy and actively seeks to influence even national issues outside of Italy and international controversies. This is the case of the topic “Diplomatic Relations”—mostly present in the years of Pope Francis’ pontificate. For instance, all those articles dedicated to the Vatican’s diplomatic relations (such as the Pope’s meetings with Heads of State, ministers, etc.) and the topic “Wars and crisis situations”, indicating the Catholic Church intervening in—and/or condemning—crisis and war situations in other countries of the world. The other topic that characterises the pontificate of Pope Francis is then that of “Wars and Crisis Situations” present almost exclusively in the years of Pope Bergoglio’s pontificate (Table 4) with a peak of 15.8% in 2014. It must be said that, from 2013, the year of Pope Francis’ election, there has been a sharp increase in war and crisis situations around the world. This has certainly affected the action of Pope Francis’ pontificate. But the same applies to the topic “Diplomatic Relations”, and the openness to the outside world and interest in issues that affect not only the Vatican and Italy particularly characterise the work and identity of Pope Bergoglio. The topic “Wars and Crisis Situations” turns out to be perfectly in line with what has also emerged in other studies on the presence and role of religion—and religious institutions—in the public sphere (Mason 2019). Such as the conflict frame noted by Lövheim (2019) whereby religion and religious actors are often associated with issues affecting conflicts and crises of various kinds.

This international dimension of the Italian press coverage of the Catholic Church is also linked to the topic of “Islam and interreligious dialogue”. This category includes all those articles dedicated to the broader issue of the presence and role of Islam in Western societies, referring in particular to articles on the phenomenon of Islamic terrorism and the construction of Islamic places of worship in Italy and elsewhere. Once again, we are facing a theme that can be traced back to the more general conflict frame elaborated by Lövheim (2019) in which religious institutions are called upon to intervene in occasions of conflicts and situations of international tension. In this case, the Catholic Church proposes itself—through its intervention—as a promoter of peace in major national and international tensions of a religious nature (such as situations of religious persecution in various countries around the world). In this regard, the Catholic Church is mostly covered when it intervenes in what can be defined as trigger events (Boydstun 2013), i.e., events capable of triggering unexpected and sudden articulations of an issue. In this case, reference is made to the terrorist attacks recorded in the years under analysis that have contributed to generating the debate on Islamic extremism as a threat to Western societies. Indeed, if we look at the trend of the theme in Table 4, we can see that the most relevant peaks are close to the major terrorist attacks in recent years (31.7% in 2015, the year of the attack on the headquarters of the French newspaper Charlie Hebdo and the attack on the Bataclan theatre).

A topic that recurs several times in the considered years, with an increase in the recent years of Pope Benedict XVI’s pontificate (2010–2012), is that of “scandals” (in 2010, the topic reached 20.8%). The topic includes all those articles that reported on events of a different nature (sex scandals, financial ones, etc.) that involved the Catholic Church at different levels. As Soukup (2019) reports, in popular usage the term “scandal” typically refers to something wrong, mostly of a moral nature, capable of provoking a strong public reaction. Scandals are by their very nature highly newsworthy events. All the more so if religious actors end up in the eye of the storm of a scandal: “since religion by definition upholds and defends a moral order, it constitutes a perfect target for scandal-like accusations” (Soukup 2019, p. 389). The religious institution at any level juxtaposed with a scandal event contributes to the story taking on even more exaggerated dynamics. The genre of religious scandal in the media requires a religious figure to act against the dictates of religion or violate the moral expectations that the religious figure personally entails (Soukup 2019). This is primarily the case of scandals involving cases of sexual abuse, particularly perpetrated against minors. In the case of sexual abuse, the tension is heightened between a Church that is the bearer of moral order (particularly on issues concerning the sexual sphere in general and, a fortiori, the inviolability of the sexual sphere of minors) and a Church that tramples on its own values. In this regard, the year in which the coverage on the subject of scandals peaked, 2010, coincides with the widespread echo of the scandals from Boston (USA), which turned the international spotlight on the abuse perpetrated by clergymen, and with the Catholic Church releasing data for the first time on the trials of priests in the same year. The same thing happens with financial scandals. Although they have a different effect on public opinion compared to paedophilia cases, the financial scandal has another aspect associated with the moral sphere. In this case, the image of a poor Church that helps the weakest thanks to the donations of the faithful, which often preaches poverty itself, finds itself at the centre of scandals that bring out, on the contrary, the opulent face of the religious institution, the one involved in the buying and selling of valuable real estate and money laundering. Soukup (2019) argues that whatever the nature of the scandal, the media’s focus on scandals involving religious institutions indicates an approach of general scepticism towards religious groups and a simplified understanding of the nature of religion, which emphasises and exaggerates the conflictual dimension between society and the religious institution.

Among the topics that have recurred the most and, in some cases, have been a constant in the media coverage of the Catholic Church in Italy, there are certainly the topics of “Secularism” and “Catholic vote”. These two themes are distinct from each other but, on closer inspection, show points of contact. The secularity of the state or secularism is a topic that has been involving the Catholic Church in public debate for decades. Within the topic “Secularism”, in this study, all items related to the debate on the secularity of the State and the separation of Church and State (such as religious symbols in public places, the teaching of religion in schools, the debate on the appropriateness of renewing the State-Church concordat, etc.) have been included. Table 4 shows the trend of the topic with an important and continuous presence especially in the initial years of analysis, from 2005 to 2009, with a peak of 21.7% in 2005. As Garelli (2014) argues, in France, the debate on religious symbols has mainly revolved for years around the issue of the Islamic headscarf; however, in Italy, it has instead focused on whether or not the crucifix should be displayed in places of public service (schools, hospitals, courtrooms, etc.). According to Garelli, the crucifix is in fact one of the most debated cultural issues in Italy, both because of the frequency with which it is addressed and the harshness of the tones used, and also because the discussion involves not only ordinary citizens but also increasingly high number of institutional offices at cross-national borders (Garelli 2014). Also, in the present study, the Strasbourg Court ruling on the issue of displaying crucifixes in public places recorded an increase in articles relating to the topic of the secularity of the State (16.3% in 2009). However, the topic of “Secularism” is of particular interest in this study because it allows the observation of a topic that has undergone transformations over time. It shifts from having to justify and in some way legitimise the religious symbols—and hence their presence—in public space, to having to defend the use of the same from the instrumentalization of non-religious actors. In the first case, we are facing a type of involvement of the religious institution in the debate on secularism that we can define as more traditional, that is, linked to the broader discussion on the public role of religion (Casanova 1994, 2008). In the second case, we witness a renewed decline in the Catholic Church’s role in the debate on secularism. In this regard, reference is made to the recorded increase in the Church’s coverage on the issue of secularism in 2018 (18.1% in Table 4), which after years returns to heat up the debate due to the use of religious symbols by populist centre-right leaders. In this sense, the issue has been reversed, and the Catholic Church has now been called upon to intervene in the public debate to defend its symbols from a use often defined as improper, in a historical moment in which the religious element is a symbolic and rhetorical resource for numerous leaders and parties of the populist right (Ozzano 2019; Marchetti et al. 2022), not only in Italy (Wagenvoorde 2020).

Linked to this, the topic of the “Catholic vote” is the only one that maintains a constant presence in all 17 years (except 2021). This category includes all those articles dedicated to the question of the positioning of Catholics in the party and the political arena in general. The relationship between Catholics and politics in Italy has been widely studied over the years for the role that the catholic cultural component has played in the orientation of electoral behaviour (Parisi 1979; Pace 1995; Segatti 2006; Diamanti and Ceccarini 2007; Marzano 2013; Diotallevi 2016). In the interpretation of the data in this study, the theme of the catholic vote has been linked to that of secularism insofar as it always relates, in a certain sense, to the space and role played by the Catholic Church—in this case by Catholics in general—within the public sphere, particularly the political sphere. The transversal presence over time of the topic of the catholic vote indicates the attention paid to a portion of the electorate that over time—albeit with different profiles—is appealing to a part of the party offer in our country. On closer inspection, it seems to be one of the topics that has changed the most over time where the issue of the Catholic electorate is first the prerogative of the Catholic Church itself to guide the consensus of Catholics, and then of the political class itself to “urge” a less defined electorate.

Another issue on which the Catholic Church is periodically covered in the press during the period under review is that of “immigration”, in line with the findings of Marchetti and colleagues (2019). Together with the ethical issues discussed above, the one of immigration is another particular divisive issue. Table 4 shows how the coverage of the Catholic Church on the issue over the 17 years increases as the political clash on the issue grows (in 2019, the year of the Lega-Movimento 5 Stelle government, it is 41%). However, in this case, the Catholic Church is not only reported on by the press because it intervenes on an issue particularly divisive that is at the centre of numerous political controversies, but also because it is legitimised to participate in the debate due to its issue ownership on the topic. In fact, the Catholic Church, thanks to the numerous “hands” it has throughout Italy, is one of the main actors to deal with the reception of migrants in our country. Dioceses, parishes, associations, and catholic movements throughout the country are daily engaged in guaranteeing sustenance, training, and integration to the many people who reach Italy after fleeing situations of war, poverty, and crisis. The topic that is periodically covered is of the Catholic Church that denounces situations of exploitation and violation of rights, and promotes the reception and integration of immigrants into the Italian society. In this sense, and for all intents and purposes, it carries out an advocacy action to maintain attention on the issue and influence government decisions on the matter (agenda building).

Similarly, with the topic “Social Issues”, as seen with the topic of immigration, the Catholic Church that is legitimised by the press to intervene is the one that takes the front line and stands up in defence of the last, the most fragile. The social issue is another of the main topics on which the Catholic Church has a standing on the media due to its activities at the local and national levels to protect the weakest segments of the population, in a country where the third sector—made up of many catholic organisations, the main one being Caritas—is one of the main actors in the social protection network on the ground (Itçaina 2018). For keeping up with the news cycles of attention, in this study, the topic recurs, in particular, as a backlash of the two most important economic crises of the years considered in the study, that of 2008 (a first “wave” of coverage on the topic is recorded in the years 2009–2013) and the more recent one as a consequence of the COVID-19 emergency (which registers 20.7% in 2021).

Finally, the topic “COVID-19”, unlike the others and as can be guessed, was found only in the recent years of the analysis in correspondence with the pandemic emergency that affected not only Italy but also the whole world (38.6% in 2020 and 28.9% in 2021). In this exceptional situation, the Catholic Church found its place in the press as a protagonist in the response to the crisis caused by the virus. COVID-19 called for special emergency management for which the Catholic Church and its institutions on the ground were to some extent—and more than other civil actors—already prepared. The Catholic Church is rooted throughout the country and hence can possibly count on its resources both human (the priests, the nuns, the volunteers) and organizational (the numerous spaces owned and managed by the Church). For example, all those parishes and dioceses that have made their spaces available for the vaccination campaign, in the face of a shortage of premises belonging to the public actors, as also noted by other studies on the subject (Contreras 2021). At the same time, there is also no shortage of news that we could define as exotic, that is, all those news items born from facts and events that stimulate the curiosity of readers because they involve unusual, sympathetic—and sometimes irreverent—aspects of the Catholic Church that journalists find particularly appealing. Reference is made to the curiosity generated by the Catholic Church that is forced to adapt its rites in a context of limited travel through the adoption of digital tools (Contreras 2021) and to church actors’ no-vax positions.

5. Concluding Remarks

In answering the three research questions, the study essentially confirmed the initial hypothesis that, in Italy, contrary to the literature, it is not possible to speak of a current greater visibility of religion and in particular of the Catholic Church compared to the past. In response to the first research question (RQ1), the analysis of the trend on coverage shows a decrease in the attention dedicated to the Catholic Church; the reasons behind this are certainly not easy to trace, but in the course of the work, we have tried to propose some reasons, i.e., changes in the media ecosystem and in the editorial choices of newspapers, but also changes within the “catholic world”.

However, contrary to this, in response to the third research question (RQ3), the analysis of the main topics on which the Church has been covered is consistent with those developed in the literature as issues on which religions are traditionally legitimised to intervene, recognising the public role of religion. These are mostly particularly divisive issues (such as those on bioethics, civil unions, etc.) on which the Catholic Church intervenes in accordance with its own value set and by advocating its own frames to the issues under discussion. There are also issues on which the Catholic Church has a recognised issue ownership (such as immigration and social issues in general), carrying out advocacy actions. Furthermore, confirming the initial hypothesis, if, on one hand, there was no increase in coverage, on the other hand, the analysis of the topics also confirmed the transformation of some issues that has declined in different ways over time (such as topics concerning the secularity of the state and the catholic vote), thus indicating a coverage that, although focused on specific recursive issues, changes its nature over time.

Finally, answering the second research question (RQ2) about the main Catholic Church actors that have received the most attention over the time, without too many surprises, the focus of attention is the Catholic Church leadership—particularly the Pope, but also other actors. At the same time, in the recent years, there has been an increasing focus on lower levels of the hierarchical scale (such as priests), also due to their role in the pandemic emergency. One may wonder how much of this is due to the intervening phenomena of disintermediation caused by the advent of social media, which expands the opportunities for traditionally non-newsworthy actors to intervene in public debates.

For this reason, as future developments of the study, it is desirable to continue the research on this topic by considering different media (news websites and online only) to see whether the coverage devoted to the Catholic Church and its actors also changes with varying media characteristics and newsworthiness criteria. At the same time, the data presented in the article need further investigation. In particular, it is desirable to delve deeper into each issue that has emerged to see how, consistent with the nature of the topic, the Catholic Church is also represented in terms of the framing of individual issues.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M. and S.P.; Methodology, R.M. and S.P.; Software, R.M. and S.P.; Validation, R.M. and S.P.; Formal analysis, R.M. and S.P.; Investigation, R.M. and S.P.; Resources, R.M. and S.P.; Data curation, R.M. and S.P.; Writing–original draft, R.M. and S.P.; Writing–review & editing, R.M. and S.P.; Visualization, R.M. and S.P.; Supervision, R.M. and S.P.; Project administration, R.M. and S.P.; Funding acquisition, R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by MUR PRIN 2022 - 202295MWTJ RE-PUBLIC. Religion in Public: Forms and Dynamics of Religious Publicization in Italy, and by the Centro Universitario Cattolico (CUC), Rome.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | In the database used for the corpus selection, articles from la Repubblica before 1 July 2005 are not available. Therefore, articles from la Repubblica were collected as of 1 July 2005. |

| 2 | Italian keywords used: Arcivescovo, Benedetto XVI, Bergoglio, Cardinal, Cardinale, Cardinali, cattolicesimo, cattoliche, cattolici, cattolico, CEI, Chiesa cattolica, Conferenza Episcopale, curia, diocesane, diocesani, diocesano, Diocesi, frati, Giovanni Paolo II, monsignor, Papa Benedetto, Papa emerito, Papa Francesco, parrocchie, parroci, parroco, Pontefice, prete, preti, Ratzinger, Santa sede, suora, suore, Vaticano, vescovi, vescovo, Wojtyla. |

| 3 | See https://global.factiva.com/ (accessed on 1 November 2023). |

| 4 | See https://www.volopress.it/ (accessed on 1 November 2023). |

| 5 | See https://provalisresearch.com/products/qualitative-data-analysis-software/ (accessed on 1 November 2023). |

| 6 | See https://provalisresearch.com/products/content-analysis-software/ (accessed on 1 November 2023). |

| 7 | The categories of actors identified are: Pope, Cardinals, Bishops, Vatican, Italian Episcopal Conference (CEI), Religious Orders, Movements and Associations, Dioceses, Parishes, Priests, Catholic Media, and Benedict XVI. In the latter case, a dedicated category was established to distinguish the resigning pope from the incumbent pope starting from the year 2013. |

| 8 | See https://www.repubblica.it/politica/2023/01/23/news/papa_francesco_convince_sette_italiani_su_dieci_la_chiesa_perde_consensi-384687165/ (accessed on 1 November 2023). |

| 9 | Charlie Gard was a one-year-old child who had been suffering from a serious illness since birth and died after the judges ordered him to be taken off the artificial respirator. In this case, Pope Francis personally intervened to allow the child to avoid the decision of the English judges by transferring him to the Holy See-owned Bambino Gesù hospital in Rome. |

References

- Altheide, David L., and Robert P. Snow. 1979. Media Logic. Beverly Hills: London Sage, vol. 8, pp. 1094–96. [Google Scholar]

- Arato, Andrew, and Jean L. Cohen. 2018. Civil Society, Populism, and Religion. In Routledge Handbook of Global Populism. Edited by Carlos de la Torre. London: Routledge, pp. 112–26. [Google Scholar]

- Axner, Marta. 2015. Studying Public Religions: Visibility, Authority and the Public/Private Distinction. In Is God Back? Reconsidering the New Visibility of Religion. Edited by Titus Hjelm. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, pp. 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, Howard. S. 1967. Whose Side Are We On? Social Problems 14: 239–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boydstun, Amber E. 2013. Making the News. Politics, the Media, and Agenda Setting. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Judith, Habermas Jurgen, Taylor Charles, and Cornel West. 2011. The Power of Religion in the Public Sphere. New York: Columbia UP. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidi. 2010. When Religion Meets New Media. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, José. 1994. Public Religions in the Modern World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, José. 2008. Public Religions Revisited. In Religion: Beyond the Concept. The Future of the Religious Past. Edited by Hent de Vries. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, José. 2011. The Secular, Secularizations, Secularisms. Oxford: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb, Roger W., and Charles D. Elder. 1975. The Politics of Agenda-Building: An Alternative Perspective for Modern Democratic Theory. The Journal of Politics 33: 892–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Yoel. 2018. Spiritual News: Reporting Religion Around the World. New York: Peter Lang Inc., International Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, Diego. 2021. Church Communication Highlights 2020. Church, Communication and Culture 6: 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davie, Grace, and Erin K. Wilson. 2020. Religion in European society: The factors to take into account. In Religion and European Society: A Primer. Edited by Ben Schewel and Erin K. Wilson. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayan, Daniel, and Elihu Katz. 1992. Media Events. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- DeHanas, Daniel N., and Marat Shterin. 2018. Religion and the Rise of Populism. Religion, State & Society 46: 177–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamanti, Ilvo, and Luigi Ceccarini. 2007. Catholics and Politics after the Christian Democrats: The influential minority. Journal of Modern Italian Studies 12: 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diotallevi, Luca. 2016. On the current absence and future improbability of political Catholicism in Italy. Journal of Modern Italian Studies 21: 485–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galtung, Johan, and Mari Holmoboe Ruge. 1965. The Structure of Foreign News: The Presentation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus Crises in Four Norwegian Newspapers. Journal of Peace Research 2: 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gans, Herbert J. 1979. Deciding What’s News. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Gans, Herbert J. 2011. Multiperspectival news revisited: Journalism and representative democracy. Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 12: 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garelli, Franco. 2014. Religion Italian Style. Ashgate AHRC/ESRC Religion and Society Series; London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Garelli, Franco. 2020. Gente di Poca Fede: Il Sentimento Religioso nell’Italia Incerta di Dio. Bologna: Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Golan, Oren, and Michele Martini. 2022. Sacred Cyberspaces: Catholicism, New Media, and the Religious Experience. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP. [Google Scholar]

- Guizzardi, Gustavo. 1986. La Narrazione del Carisma. I viaggi di Giovanni Paolo II in Televisione. Torino: Rai-Eri. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 2018. Rinascita delle Religioni e Secolarismo. Brescia: Morcelliana. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert, David E. J. 2011. Theorizing Religion and Media in Contemporary Societies: An Account of Religious ‘Publicization. European Journal of Cultural Studies 14: 626–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjarvard, Stig. 2008. The Mediatization of Religion: A Theory of the Media as Agents of Religious Change. Northern Lights: Film & Media Studies Yearbook. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjarvard, Stig. 2012. Three Forms of Mediatized Religion: Changing the Public Face of Religion. In Mediatization and Religion. Edited by Stig Hjarvard and Mia Lövheim. Göteborg: Nordicom. [Google Scholar]

- Hjelm, Titus. 2015. Is God Back? Reconsidering the New Visibility of Religion. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hoelzl, Michael. 2020. The New Visibility of Religion and Its Impact on Populist Politics. Religions 11: 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, Stewart M. 2006. Religion in the Media Age. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Itçaina, Xabier. 2018. Catholic Mediations in Southern Europe: The Invisible Politics of Religion. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Knott, Kim, Poole Elizabet, and Teemu Taira. 2013. Media Portrayals of Religion and the Secular Sacred: Representation and Change. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lövheim, Mia. 2019. Culture, Conflict and Constitutional right: Representations of Religion in the Daily Press. In Religion and European Society: A Primer. Edited by Ben Schewel and Erin K. Wilson. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Lövheim, Mia, and Alf Lindermann. 2015. Media, Religion and Modernity: Editorials and Religion in Swedish Daily Press. In Is God Back? Reconsidering the New Visibility of Religion. Edited by Titus Hjelm. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti, Rita. 2011. La Chiesa nel dibattito pubblico. In Altri flussi. La comunicazione politica della società civile, ed. Edited by Rolando Marini. Milano: Guerini Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti, Rita, Susanna Pagiotti, Anna Stanziano, and Marco Mazzoni. 2019. Il coverage della Chiesa cattolica: Non più solo un’immagine «vaticana». Problemi dell’Informazione 44: 545–69. [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti, Rita, Nicola Righetti, Susanna Pagiotti, and Anna Stanziano. 2022. Right-Wing Populism and Political Instrumentalization of Religion: The Italian Debate on Salvini’s Use of Religious Symbols on Facebook. Journal of Religion in Europe 15: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, Rolando. 2007. Mass Media e Discussione Pubblica: Le Teorie Dell’agenda Setting. Roma-Bari: Gius, Laterza & Figli Spa. [Google Scholar]

- Marzano, Marco. 2013. Quel che Resta Dei Cattolici. Milano: Feltrinelli Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, Debra. 2019. Religion coverage. The International Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoleni, Gianpietro. 2012. La Comunicazione Politica. Bologna: Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoleni, Gianpietro, and Winfried Schulz. 1999. Mediatization of politics: A challenge for democracy? Political Communication 16: 247–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Birgit, and Annelies Moors. 2006. Religion, Media, and the Public Sphere. Indianapolis: Indiana UP. [Google Scholar]

- Mihai, Coman. 2023. Media, Religion, and the Public Sphere. Religions 14: 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2007. Sacro e Secolare. Religione e Politica nel Mondo Globalizzato. Bologna: Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Ozzano, Luca. 2019. Religion, Cleavages, and Right-wing Populist Parties: The Italian Case. The Review of Faith & International Affairs 17: 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozzano, Luca, and Alberta Giorgi. 2016. European Culture Wars and the Italian Case: Which Side Are You On. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pace, Enzo. 1995. L’unità dei Cattolici in Italia. Milano: Guerini e Associati. [Google Scholar]

- Parisi, Arturo. 1979. Un partito di cattolici? L’appartenenza religiosa e i rapporti con il mondo cattolico. In Democristiani. Edited by Arturo Paris. Bologna: Il Mulino, pp. 85–125. [Google Scholar]

- Rovisco, Maria, and Sebastian Kim. 2014. Cosmopolitanism, Religion and the Public Sphere. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Schewel, Ben, and Erin K. Wilson. 2020. Religion and European Society: A Primer. London: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Segatti, Paolo. 2006. I cattolici al voto, tra valori e politiche dei valori. In Dov’è la Vittoria?Il Voto del 2006 Raccontato Dagli Italiani. Edited by Itanes. Bologna: Il Mulino, pp. 109–26. [Google Scholar]

- Soukup, Paul A. 2019. Scandals, media and religion. In The Routledge Companion to Media and Scandal. London: Routledge, pp. 389–98. [Google Scholar]

- Tentori, Tullio. 1986. L’informazione Religiosa Nella Stampa Italiana. Milano: Franco Angeli. [Google Scholar]

- Wagenvoorde, Renee. 2020. The Religious Dimensions of Contemporary European Populism. In Religion and European Society: A Primer. Edited by Ben Schewel and Erin K. Wilson. London: Wiley, pp. 111–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).