Abstract

In many countries, those considering enrolling in a Catholic college or university may have a choice between a few universities or none at all. In the United States, they can choose between more than 240 Catholic colleges and universities. This provides a rich array of choices, but it may also make the decision of where to apply and ultimately enroll more complicated. This article provides a simple framework to discuss some of the factors that affect the decision to enroll in higher education and where to enroll. Four basic sequential questions that students may ask are considered: (1) Should I go to college? (2) How should I select a college? (3) How can I compare different colleges? (4) Should I go to a Catholic college? By providing elements of response to these questions, the article provides insights into the decision to enroll in Catholic education and its implications for universities.

1. Introduction

The Catholic Church is the largest non-governmental provider of education in the world. According to data from the Church, in 2020, Catholic pre-primary, primary, and secondary schools enrolled 61.4 million students globally (Secretariat of State [of the Vatican] 2022). In addition, Catholic institutions of higher education enroll 6.6 million students (on global trends in Catholic higher education, see Wodon (2020, 2022)). For basic education, enrollment in Catholic schools has been growing especially rapidly in Africa. As a result, today, seven in ten students in Catholic primary schools live in low and lower-middle-income countries. By contrast, for higher education, Catholic universities and other post-secondary education institutions remain concentrated in upper-middle and high-income countries, as is the case for other types of universities (on some of the challenges affecting the higher education sector as a whole, see International Federation of Catholic Universities Foresight Unit (2021); Mellul (2022)). Globally, seven in ten students in Catholic higher education live in upper-middle or high-income countries1.

The United States, the country of focus for this article, plays an especially important role in Catholic higher education globally. This is in part due to the size of the country and the fact that it has a highly educated and comparatively wealthy population. However, it is also due to the fact that universities in the United States are popular abroad. Although the number of international students has been reduced due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it remains high. Overall, in 2020, of all students enrolled in Catholic higher education globally, almost one-fifth (1.2 million) were enrolled in the United States. This estimate includes both students in universities and those enrolled in other forms of higher education. If one considers only university students, the United States accounts for 22% of all students enrolled in Catholic universities globally (more than 0.8 million out of a total of almost 3.8 million students). After the United States, India and the Philippines have the largest number of students in Catholic higher education. Several European and Latin American countries also have many Catholic universities and, therefore, students. By contrast, sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and North Africa, and the rest of Asia account for only a small share of all students in Catholic higher education.

In many countries, those considering enrolling in a Catholic college2 or university may have a choice between a few universities or none at all. In the United States, they can choose between well over 200 Catholic colleges and universities. This provides a rich array of choices, but it may also make the decision of where to apply and enroll more complicated3. This article discusses some of the factors that may affect the decision of prospective students to enroll in higher education and where to enroll4.

Faith and values are likely to matter for some students enrolling in Catholic colleges and universities, but not for all. This is suggested by both international data (Aparicio Gómez and Tornos Cubillo 2014; Mabille and Bartroli 2021) and data for the United States, where some have argued that faith may actually matter more than often believed (Mayrl and Oeur 2009; Sommerville 2006; Hill 2009; Jacobsen and Jacobsen 2012).

In order to provide a framework for the analysis, it is useful to place ourselves within the frame of mind of a student (or a student advisor). As shown in Figure 1, four basic sequential questions are likely to be considered by students: (1) Should I go to college? (2) How should I select a college? (3) How can I compare different colleges? (4) Should I go to a Catholic college? While answers to those questions can be provided only by individual students themselves, some data are available to inform responses to these questions.

Figure 1.

Four Basic Sequential Questions. Source: Author.

This article hopefully provides insights on the decision to enroll in Catholic education that could be useful not only for students but also for university administrators at a time when many colleges and universities are under financial pressure. Estimates from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center (2022) suggest that in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic, post-secondary enrollment fell to 16.2 million students in the spring of 2022, a drop of 4.1 percent or 685,000 students from the previous year. Adding the drop of 3.5 percent observed the previous year, post-secondary institutions lost nearly 1.3 million students since the start of the pandemic. The loss was especially severe at the undergraduate level (a decline of 9.4 percent or nearly 1.4 million students). Enrollment losses were larger in community colleges and in 4-year public colleges than in private 4-year colleges. Therefore, Catholic colleges and universities may not have suffered as much since they are typically included in the 4-year private non-profit category. However, many have been weakened by the crisis. There have been stories in the media about Catholic colleges and universities closing because of the additional financial stress brought about by the pandemic. More fundamentally, long-term pressures on the sustainability of at least some Catholic institutions are likely to become more severe. This is in part because of demographic shifts5, but also because of a process of secularization that may lead students to not consider enrolling in Catholic institutions6. Therefore, understanding the factors that may lead students to enroll in Catholic higher education is important (beyond the United States, universities have been affected by the pandemic worldwide; they have tried to adapt, but with mixed success, according to a survey by UNESCO (2021)7).

Given this context, this article aims to provide a simple analysis of the decision to go to college and enroll in a Catholic university in the United States. The article is structured as follows. The next four sections consider each of the four questions mentioned above, namely (from the point of view of a student): (1) Should I go to college? (2) How should I select a college? (3) How can I compare different colleges? (4) Should I go to a Catholic college? A brief conclusion follows.

2. Should I Go to College?

Enrolling in college may not be the right choice for everybody, and unfortunately, college remains difficult to afford for too many youths in the United States. Still, about two-thirds of young people in the United States decide to enroll in higher education institutions. Indeed, according to recent statistics from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, of 3.2 million youth ages 16 to 24 who graduated from high school between January and October 2019, 2.1 million (66.2%) were enrolled in college in October of that year. In addition, the number of adults going to college is increasing.

As another useful measure to show how going to college is an opportunity sought by many students, consider the gross enrollment rate for tertiary education, which tends to be higher than the share of high school graduates going to college since it includes older individuals8. According to data from the World Development Indicators, the gross enrollment rate for tertiary education in the United States was 88.3% for the latest year of data available. This is higher than the rate for all high-income countries (75.7%) and more than twice the level observed globally (38.8%)9.

Going to college is a privilege, as well as a great opportunity that can bring lifelong rewards. There is extensive literature on the benefits of going to college in the United States. Much of this literature focuses on employment-related benefits. In comparison to those with only a high school diploma, individuals with a college degree tend (on average) to (1) have higher earnings; (2) have more and better job opportunities, including access to specialized careers that may not be available to those with only a high school diploma; (3) have lower unemployment rates, higher job satisfaction rates, more stability in employment, and better pensions; (4) develop stronger skills in a range of areas, including problem-solving, critical and analytical thinking, communications, leadership, and more generally personal growth as well as self-esteem. It may not always be necessary to go to college to enjoy these benefits, but a college degree helps, and the trend is for more job openings to require a degree.

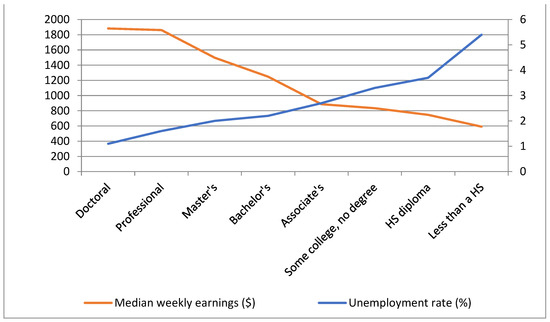

As an example of some of the employment-related benefits associated with a college degree, Table 1 and Figure 2 provide data available from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics on unemployment rates and median weekly earnings by educational attainment10. Workers with a Bachelor’s degree make approximately USD 500 more in median weekly earnings than those with only a high school diploma. That is an increase of two-thirds versus the pay level for high school graduates. In addition, the unemployment rate for high school graduates is typically much higher than for college graduates. The disadvantages faced by those without a college degree have been further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has disproportionately affected low-income workers in the service sector not only in the short term but also in the future.

Table 1.

Unemployment Rate (%) and Median Weekly Earnings (USD) by Educational Attainment.

Figure 2.

Unemployment Rate (%) and Median Weekly Earnings (USD) by Educational Attainment. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Note: Data updated in September 2020.

In today’s labor market, workers need to acquire certain key competencies required by employers, but college often helps to do so. According to a recent report by the Center on Education and the Workforce (Carnevale et al. 2020b), certain competencies are associated with higher wages. Across occupations, being able to communicate, engage in teamwork, provide sales and customer service, exercise leadership, and demonstrate problem-solving skills and complex thinking are the most demanded competencies by employers. By contrast, physical strength and coordination are the least in demand. Not surprisingly, the jobs in which cognitive competencies tend to be used the most are held mostly by workers with higher levels of education. For example, three-fourths of workers who intensively use communications skills have a bachelor’s degree or higher, while only one in ten workers who use strength and coordination abilities most intensively do.

A logical conclusion of these various analyses is that a college education may be even more important in the future than it is today for succeeding in the labor market. It should be recognized that there may be other ways to acquire skills and competencies that are in demand in the labor market and that prospective students should be careful not to accumulate too much debt to go to college. It is also clear that beyond what can be learned in college, there will be a greater premium in the future on life-long learning. Still, going to college, if feasible, is often a great first step.

Beyond benefits for the labor market, a college education can also bring a wide range of other benefits that can last a lifetime. For example, better-educated men and women tend to have more agency in their lives—they tend to be more empowered to make their own decisions. Across countries, more educational attainment is associated with being able to rely on friends when in need and even with a stronger ability to engage in altruistic behaviors such as giving to charitable organizations, volunteering, and helping strangers. This particular association between educational attainment and altruistic behaviors is clearly not because somehow those who are better educated are more altruistic, but rather because individuals who are better educated are more likely to be in a position in their own life that enables them to help others (Nguyen and Wodon 2018).

Finally, a commonly perceived medium term threat for workers is that of automation and artificial intelligence (AI). While some jobs will be created by AI, many others may be eliminated. The COVID-19 crisis has accelerated investments in automation and AI, according to research by McKinsey (Lund et al. 2021). In the United States, jobs in the food and customer service industries may be most affected. While automation and AI were previously expected to affect mostly middle-wage occupations in manufacturing and office work, the expectation now is that low-wage workers will be more affected than before. As a result, almost all of the growth in the labor force is expected to take place in high-wage jobs, which often require a college degree and high-level socio-emotional skills. The McKinsey report also notes that in Europe and the United States, workers with less than a college degree are more likely to need to change occupations after COVID-19 than before.

3. How Should I Select a College?

Each student is unique, with his or her own set of priorities when selecting a college. One set of priorities is not necessarily better than another, as they depend on the student’s background and aspirations. However, the fact that there are more than 240 Catholic colleges and universities in the United States is a great asset for the sub-sector to respond to different sets of priorities among prospective students. While, again, each student is indeed unique, it is interesting for students to know about the priorities of other students and whether there are differences in the priorities of students who chose to enroll in Catholic colleges and universities in comparison to all college freshmen. For some students, faith may be an important factor in the choice of a college, but other factors come into play as well. For other students, faith may not matter much. It is important to emphasize that Catholic colleges and universities welcome students from all backgrounds as well as all faiths (or lack thereof) and worldviews. For the United States specifically, according to data from the CIRP (Cooperative Institutional Research Program) Freshman Survey11, about a quarter of all college freshmen at four-year colleges in the United States identify as Catholic, while the proportion is just above two fifths for freshmen at Catholic institutions identified as Roman Catholic. In other words, most students at Catholic colleges and universities are not themselves Catholic. The fact that many students who attend Catholic colleges and universities are not themselves Catholic is an asset because it brings diversity to their campuses.

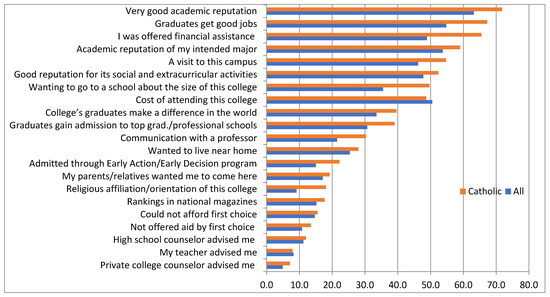

Data from the CIRP Freshman Survey can be used to compare students’ priorities depending on the type of schools they choose to attend. Those data were mentioned in Wodon (2022), but here the focus is on a comparison between responses for students in Catholic colleges and the sample as a whole. As shown in Table 2 and Figure 3 for the latest available CIRP survey (data for 2019), the main reasons cited for attending Catholic colleges relate to academic reputation (71.8%); job prospects (67.3%); financial assistance (65.5%); reputation of the intended major (59.0%); campus visits (54.7%); social and extracurricular activities (52.4%); college size (49.7%); and finally cost (48.7%). Reputation and job prospects clearly matter, as do visits to the schools, financial assistance and cost, extracurricular activities, and the size of the college. Differences between results for all institutions and those for freshmen at Catholic institutions are, however, worth pointing out. The largest differences in priorities for selecting a college between a student going to Catholic institutions and all students relate to financial assistance, college size, employment prospects, faith affiliation, and advice from professors.

Table 2.

Share of College Freshmen Declaring Various Reasons as “Very Important” in Deciding to Go to that Particular College [Ranked by Share for Catholic Institutions], 2019 CIRP Freshman Survey (%).

Figure 3.

Principal Reasons for Deciding to Go to a Particular College, 2019 (%). Source: Adapted from Stolzenberg et al. (2020).

Financial assistance: The largest difference in Table 2 in absolute terms in the reasons declared for attending a particular institution between students overall and those in Catholic institutions is for financial aid. The proportion of students in Catholic institutions that declared this was a factor in their choice of college is 16.6 points higher than for all students combined. This reflects the fact that in a typical year, more than nine in ten students enrolled at Catholic institutions receive some form of financial aid.

College size: The second largest difference is for college size. While a handful of Catholic colleges and universities have more than 20,000 students, most are medium or small in size, which is welcomed by students enrolling in those institutions. There are, in particular, many liberal arts colleges among Catholic institutions.

Employment prospects: The third largest difference is for the perception that college graduates attain good jobs. Many Catholic colleges and universities have strong placement records, which is one of the reasons why student debt default rates are much lower among graduates from Catholic institutions than nationally.

Faith affiliation: The fourth largest difference is for the faith affiliation of the college. Typically less than one in ten incoming freshmen consider the religious orientation or affiliation of their college as a very important factor in their choice of attending that college. Among students attending Catholic colleges, the corresponding figure is about one in five students.

Advice from professors: The fifth largest difference in Table 2 relates to the advice provided by a Professor. Professors in Catholic colleges and universities tend to care about their students, not only academically but in terms of integral human development—this is part of the institutions’ ethos.

It is worth noting that in other market research, some of the characteristics associated with Catholic universities are “conservative”, “traditional”, and “expensive”12. This is not necessarily a positive perception from a marketing point of view, but it does suggest again that students choosing Catholic universities may have a slightly different set of priorities than those enrolling elsewhere. As is the case for the CIRP survey, this other survey suggested that the Catholic character of the college was not the main deciding factor for its choice by prospective students. Indeed, less than one in ten students, as well as parents, identified religious affiliation as a key driver of their choice. Factors such as institutional size, research opportunities, internships, and job placement were more important, as noted in the CIRP survey. These are all areas where Catholic universities do comparatively well, according to data from the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities. It is therefore not surprising that more than 40% of respondents in that other survey were interested in attending a Catholic university.

4. How Can I Compare Colleges?

All Catholic colleges and universities—and one could argue most colleges in general, including those that are not Catholic, aim to provide a comprehensive education for the whole person. Prospective students should carefully look at the websites of the universities they are considering in order to understand their programs, the courses being taught, who is teaching those courses, the opportunities for extracurricular activities or internships, distance learning options, and exchange programs, among others. Ideally, students should make visits to the campuses of the colleges and universities they are most interested in, although this is not always feasible, especially for international or out-of-state students.

Given that career prospects do matter for students when selecting a college or university and that going to college is one of the largest financial investments people make in their lifetime, prospective students should do their homework in terms of the job prospects that may be available to them depending on both the university they choose to attend and the type of studies they choose to graduate in. This does not mean that other aspects of the higher education experience do not matter. They do. There is much more to higher education, and, in particular, Catholic higher education, than preparing oneself for a career. Those aspects will be discussed later. At the same time, characteristics of different colleges and universities such as graduation rates, the type of studies in which most students major, the cost of the education being provided, and the salaries that graduates from different fields may be expected to make when their complete their education does matter for most students. The good news is that data on those outcomes are now readily available.

4.1. College Scorecard

A key source of information to compare colleges and universities is the government-run College Scorecard13. If you type the name of a specific college or university in the College Scorecard search field, you will be provided with a wide range of information, including the type of college or university this is (e.g., two or four years, public or private, the faith affiliation if any of the institution, whether it is in an urban, suburban, or rural setting, and whether the institution is small, medium, or large in terms of undergraduate enrollment).

Estimates of graduation rates are provided based on the share of students who graduate within eight years of entering a school for the first time. Estimates of the median annual earnings of students after graduation are also available for students who received federal financial aid (student debt is a major issue in the United States14). Estimates of the annual average cost of attending colleges and universities are also available for most schools, including not only tuition costs but also living costs, books and supplies, and fees minus the average grants and scholarships for federal financial aid recipients. Cost data are available according to the level of family income of students, which matters given differences in financial aid by income, at least for American students. Various statistics related to financial aid and debt levels are provided.

The College Scorecard also provides for each college or university a ranking of the main fields of study according to the number of students graduating, as well as a list of the fields of study with the highest earnings and those with the lowest debt levels. In addition, a list of all available fields of study is also provided. Finally, data are available on racial/ethnic diversity and gender, as well as on test scores and acceptance rates. A useful feature of the Scorecard is that it enables users to compare up to 10 universities and 10 fields of study. While other tools are available to compare universities, including in terms of rankings, the College Scorecard is unique in terms of the focus on a range of outcomes for students that relate to graduation rates and labor market outcomes. While these aspects of higher education are again not the sole drivers of the choice of where to enroll, they clearly matter.

The good news for Catholic colleges and universities is that apart from promoting integral education, they also do well (on average) on the various measures provided by the College Scorecard in comparison to other institutions. Most Catholic colleges and universities tend to have relatively high graduation rates, high salaries upon graduation, and high debt repayment rates, as mentioned earlier. For example, according to the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities, 80% of U.S. Catholic colleges and universities have graduation rates above the national average. Catholic colleges and universities also tend to do relatively well on a range of indices related to the experience of the students while in higher education. For example, many schools have a tradition of engaging students in service opportunities (as discussed in more details below), which can be crucial for their personal development and even career choices. However, there are also differences between colleges and universities, including between Catholic colleges and universities. Therefore, checking the data available in the College Scorecard as well as other databases can be useful for prospective students. For College Scorecard data, this can be performed directly on the College Scorecard website, but it can also be performed using other visualization tools based on the data, as illustrated in the next section.

4.2. Buyer Beware Interactive Tool

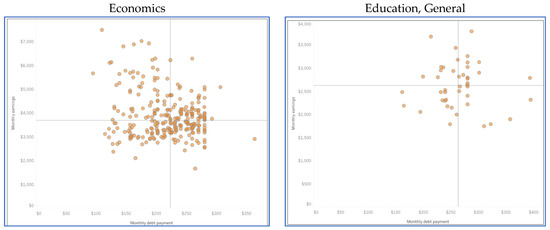

Based on data from the College Scorecard, a useful visualization tool has been developed by Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce15. The tool visualizes the first year (i.e., right out of college) monthly expected earnings for graduates as well as debt payments for college loans. This is performed for 37,000 College Majors at 4400 Institutions. An example of the scatterplots that can be created using the tool is provided in Figure 4. The scatterplot displays the data for Bachelor’s degrees in economics and in education. The average monthly debt payment burden is on the horizontal axis, while monthly average earnings are on the vertical axis. Colleges located towards the upper left corner of the Figures (higher wages and lower debt payments) tend to have, on average, better returns on investments for their students. It is worth noting that first-year earnings may be more likely influenced by choice of major rather than the choice of school. For example, dentistry majors and engineers tend to have high salaries almost regardless of their institution.

Figure 4.

First Year Monthly Expected Earnings and Debt Payments for Bachelor’s Degrees. Source: Buyer Beware Interactive Tool, based on Carnevale et al. (2020a).

The scatterplot for economics has more data points than that for education simply because more schools operate undergraduate programs in economics with a sufficient number of graduates for statistical validity in the estimates than is the case for education as an undergraduate major. The average expected monthly earnings for economics majors are typically higher than for education majors as expected. The differences in debt payments tend to be smaller, although, on average, education majors have slightly larger debt payments than economics majors.

This type of information and comparisons should again not be the main factor for choosing one major versus another, but it can be informative. Each dot on the scatterplots represents a particular college and university, with the name of the institution provided. This can also be used to compare various Catholic colleges and universities or to compare those institutions with others.

Another useful feature of the tool is that you can find a ranking of institutions by the state in terms of expected earnings, debt payments, or earnings net of debt payments. Typically, differences in rankings based on expected earnings and earnings net of debt payments are small because, as already shown in Figure 4, debt payments tend to be much smaller than earnings (this is the case on average but may not be the case for specific individuals). The analysis can again be performed for various types of degrees, and for each school, it is feasible to drill down further by field of study. Perhaps not all Catholic colleges and universities will fare well in these within-state comparisons, but many should do well.

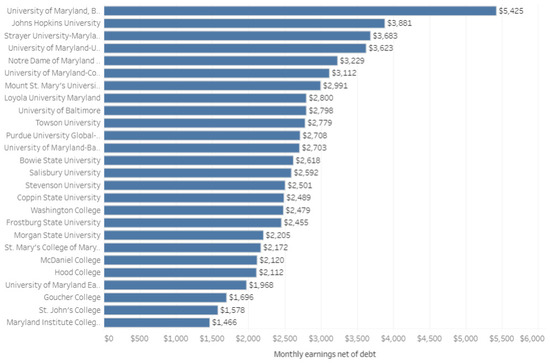

As an illustration, the visual for expected monthly earnings net of debt payments and estimates for holders of Bachelor’s degrees in Maryland are provided in Figure 5. The choice of Maryland is purely illustrative and based on the fact that the data can be displayed easily because the number of colleges and universities in the state is not too large.

Figure 5.

First Year Monthly Expected Earnings Net of Debt Payments for Bachelor’s Degrees, Colleges and Universities in the State of Maryland. Source: Buyer’s Beware Interactive Tool, based on Carnevale et al. (2020a).

The Buyer Beware tool provides data on 26 colleges and universities in Maryland, three of which are Catholic universities: (1) Notre Dame of Maryland University in Baltimore, which ranks fifth in monthly earnings net of debt in the state; (2) Mount Saint Mary’s University in Emmitsburg, which ranks seventh; and (3) Loyola University Maryland in Baltimore, which ranks eighth. The differences in monthly earnings net of debt payments between the three universities are fairly small. There is a fourth Catholic university in the state, Saint Mary’s Seminary and University in Baltimore, but it is not included in Figure 5 because it is a seminary for the formation of priests with an additional Ecumenical Institute. Therefore, it does not offer the range of programs that colleges and universities typically offer. Note that the entry for St. Mary’s College in Maryland in Figure 5 is a different (and not a Catholic) institution.

Finally, it is important to note that while instructive, simple comparisons of monthly earnings net of debt between colleges and universities do not necessarily reflect the quality of the instruction and other services provided by the institutions. Earnings can be affected by a wide range of factors, including the pool of students different colleges attract, the types of majors they choose (recall the comparison of earnings between economics and education in Figure 4), and the location of the university (some geographic areas have significantly higher earnings than others). These and other factors affect earnings and potential levels of debt as well, so there is not necessarily causality between the (quality of the) instruction and other services provided by the institutions and the level of earnings net of debt payments that graduates can expect.

4.3. College Rankings

Over the years, more and more college rankings at the national and international levels have been created, sometimes using defensible methods, other times not so much16. College rankings have become somewhat of a cottage industry. While they do provide some value for prospective students, especially when students must choose between a large number of colleges for which they may not have easy access to data, the rankings also have perverse effects. In the case of the College Scorecard, while the data can be used to provide rankings as performed in Figure 5, the Scorecard itself does not rank colleges and universities.

In the United States, some of the best-known rankings are those conducted annually by U.S. News & World Report, the Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education, the Princeton Review, Forbes, and Washington Monthly, to just name a few. U.S. News & World Report provides several rankings, considering both universities and liberal arts colleges at the national and regional levels. There are also some niche rankings available on the web, including rankings of Catholic colleges and universities that are sometimes based on these well-known rankings but may also rely on other criteria.

How well do Catholic colleges and universities do on national or regional rankings? Comparatively, they often do relatively well. As just one statistic, while Catholic colleges and universities account for only a very small share of all colleges and universities in the United States, 14 Catholic universities were ranked in the top 100 national universities according to U.S. News & World Report at the time of writing. Because there are few Catholic community colleges, this particular comparison in terms of shares may be a bit biased. Still, many Catholic colleges and universities tend to have good rankings according to at least some criteria, and when they do, this is often visible on their websites, as it is for other colleges.

Yet all this does not matter that much, especially as most prospective students cannot enroll in top-ranked universities—there are just too few places available. However, more fundamentally, it does not matter when selecting a college whether one institution is ranked slightly higher than another in any specific metrics. What matters is whether there is a good fit between the student’s profile and aspirations and what a particular college or university has to offer. In order to consider whether specific schools are a good match, college guides can be another useful source of information, although many of them focus mostly on nationally ranked colleges and universities17.

5. Should I Go to a Catholic College?

Of the four questions considered in this article, this is the most difficult question for which to provide insights based on data because it depends so much on the priorities of individual prospective students. However, a few pointers can be provided, at least tentatively. This is performed for four key topics: (1) the quality of the education provided; (2) the level of emphasis on faith, values, and collaboration; (3) opportunities for service learning; and (4) the strength of alumni networks. All four aspects are related but are discussed sequentially for ease of exposition.

5.1. Quality of the Education Provided

There are, unfortunately, no measures of the quality of the education provided by colleges and universities that are available for most institutions and widely accepted. What does seem clear, though, is that many Catholic colleges and universities place an emphasis on the quality of teaching in the classroom. This is part of how they see their mission. Many Catholic colleges and universities also try to make the education they provide affordable to students from disadvantaged backgrounds. This does not mean that they succeed in doing so, but the preferential option for the poor is a key aspect of Catholic social thought that does again affect how colleges and universities perceive their education mission.

Importantly, beyond large universities that enroll many students, many Catholic institutions are small liberal arts colleges, which matters again for the quality of the education received by students. Of all Catholic colleges and universities on the list maintained by the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities, more than a third (36.4%) are classified as liberal arts colleges. Liberal arts colleges, whether Catholic or not, tend to be undergraduate institutions placing a strong emphasis on teaching in comparison to national, highly ranked universities where a professor’s research and publications tend to be valued more than the quality of teaching. The fact that the liberal arts colleges are small often makes it easier for students to have more contact with professors and more in-depth discussions. These colleges are known to promote critical thinking, including discussion of philosophical issues. They may not work for everyone, but they add value, and it should be mentioned that many small Catholic colleges operate within that tradition.

5.2. Faith, Values, and Collaboration

Catholic colleges and universities do place an emphasis on faith and values, but this is not forced upon students, and the degree to which students in Catholic colleges and universities themselves emphasize faith as a reason for enrolling in their school varies. In some Catholic colleges and universities, most students are Catholics. In others, a minority are. Nationally, as mentioned earlier, only about two-fifths of students in Catholic colleges and universities are themselves Catholic.

While there are differences in the faith affiliations and student bodies of individual Catholic institutions, there are also differences between Catholic and other religious colleges and universities. Recall the earlier analysis of differences in the reasons for choosing a college between all students and those attending Catholic institutions. There are also differences between Catholic and other religious institutions. This is especially the case in terms of whether the faith affiliation of a university is a key reason for enrolling in that university. If one compares nonsectarian, Catholic, and other religious colleges (data not shown in Table 2 but available in the CIRP Freshman survey), only 7.0% of freshmen in nonsectarian colleges state that they were attracted by the religious affiliation/orientation of their college. The proportion is 18.1% for those in Catholic colleges, as was shown in Table 2, but it reaches 35.8% for other religious colleges, denoting even stronger importance granted to faith affiliation by students attending those religious non-Catholic institutions, many of which are evangelical. Catholic colleges and universities, therefore, occupy a sort of middle ground with respect to the importance of faith as a motivation for students to enroll.

In practice, if a student is interested in exploring or deepening his or her faith, whether Catholic or otherwise, there is no doubt that resources are available to do so in Catholic colleges and universities. However, if this is not the student’s priority, there should be no stigma. In another question in the CIRP survey, students are asked whether they consider various objectives as essential or very important. For most objectives, the differences in positive answers between freshmen at Catholic universities and all universities are small, but for “integrating spirituality into my life”, the difference is (not surprisingly) larger. This is considered a priority by 43.1% of freshmen in the full sample versus 62.2% of freshmen in Catholic colleges. Yet again, some students may not be interested in integrating spirituality into their life. Colleges respect that. The fact that most students who attend Catholic colleges and universities are not Catholic themselves is actually an asset for the institutions because it brings valued diversity on campus, which promotes dialogue.

One interesting aspect of the Catholic ethos is that it encourages collaboration as opposed to competition. This is often the case in the classroom but also in research and other activities that professors engage in. Because of this emphasis on collaboration, and the affinities that a common worldview affords, there are many examples of collaborations across Catholic colleges and universities for both research and practice. This can provide an added layer to a student’s college experience, as can the fact that service to others is valued on campus, with typically a wide range of opportunities for volunteer work and a willingness of many students to engage in such work. This is discussed in more detail in the next section dedicated to the opportunities for students to benefit from service learning.

5.3. Service Learning

In the United States, more than in most other countries, universities—Catholic or otherwise, have aimed to provide opportunities for students to engage in service learning. The American Association of Colleges and Universities (AACU) identifies service learning as one of 11 high-impact practices that can benefit students18. AACU notes that in service learning, field-based experiential learning takes place with community partners as part of a deliberate instructional strategy. Students gain experience on topics covered in the curriculum, and they apply what they are learning in the classroom in real-world settings, with the classroom providing space for reflection on students’ experiences. Service learning programs often emphasize issues of social justice. As with community service, service learning enables students to give back to the community, but in a way that harnesses the benefits of structured learning. As with internships, students may acquire through service learning skills that will be useful for the job market, but this is performed with a social justice lens and the aim to serve (and learn from) local communities. For these reasons, service learning has been promoted by public and other private universities as well as by Catholic universities, but its potential has recently been emphasized by Pope Francis as part of his broader call for a Global Compact on Education19.

Three complementary data points suggest that Catholic colleges and universities may have a comparative advantage for service learning in the United States. First, investing in service learning may help Catholic higher education institutions respond to the desire of many of their students to engage in community and service work. As shown in Table 3, data from the CIRP Freshman survey suggest that a larger share of students enrolling in Catholic institutions (43.9%) expect to participate in volunteer or community service work than is the case for students at other institutions (35.5%). Of the 17 practices identified in this part of the survey, this is the practice with the largest difference between students in Catholic institutions and all students considered together. Catholic universities rank higher for this indicator than other religiously affiliated private institutions (39.4% of students expecting to participate in volunteer or service work), nonsectarian private institutions (37.4%), and public institutions (28.7%).

Table 3.

Likelihood that Students Will Engage in Selected Practices [Ranked by Share for Catholic Institutions], 2019 CIRP Freshman Survey (%).

Second, data from U.S. News & World Report suggest that Catholic and other Christian colleges and universities are viewed as among the best in this area. Specifically, in the spring and summer of 2021, U.S. News asked college presidents, provosts, and admissions deans to name schools with the best programs in eight high-impact areas20. Rankings were generated simply on the base of the number of nominations received by schools. For service learning, of the 25 universities with at least 10 nominations from respondents, seven were Catholic institutions, and another three were Christian institutions. In other words, 40 percent of the top 25 institutions for service learning were Catholic or Christian, an unusually large share of top rankings given the small share of all colleges and universities in the country that are Catholic or Christian21.

Third, data collected from Catholic colleges and universities globally by ZIGLA (2019) suggest that institutions in the United States tend to have fairly well-integrated service-learning programs. A survey was sent to 448 Catholic universities globally to take stock of existing experiences. A total of 132 institutions responded fully, including 34 in the United States. Globally, service learning was deemed highly integrated with only 27% of responding universities, but in the United States, most of the institutions that responded had scores suggesting a high level of integration of service learning in the universities. Given the possibility of bias in the sample (universities that have made more progress towards highly integrated service learning programs may have been more likely to respond), the scores may be higher than what would have been observed if all universities had responded to the survey. Still, the results are encouraging for the comparative performance of Catholic colleges and universities in the United States, even if the COVID-19 pandemic may have generated additional challenges for service learning22.

5.4. Alumni Networks

A fourth potential strength of Catholic colleges and universities in the United States that may matter to students considering where to enroll is the strength of their alumni network23. Alumni giving can make a real difference in a college’s finances and in the life of students, especially those receiving scholarships. In the fiscal year 2020, total philanthropic giving to the education sector in the United States was at just under USD 50 billion, according to the CASE Voluntary Support of Education Survey. Of that amount, USD 11 billion (22 percent of the total) was given by alumni. The rest was given by foundations (33 percent), corporations (13 percent), non-alumni individuals (8 percent), and other organizations (14 percent), but much of that last category consists of giving through donor-advised funds24 and may thus also come in larger part from alumni. However, in addition, alumni can also make a difference for students in other ways. Freeland Fisher and Price (2021) note that alumni can play four important roles: (1) mentors to drive student success and persistence; (2) sources of career advice, inspiration, and referrals; (3) sources of experiential learning and client projects; and (4) staff for program delivery. Unfortunately, according to a Strada-Gallup Alumni Survey25, less than one in ten college graduates state that their alumni network was helpful or very helpful in the job market. Even in top universities which tend to advertise the value of their alumni networks more, only one in six alumni say their alumni network was helpful or very helpful. Furthermore, nationally the resources devoted by colleges and universities to alumni engagement may have decreased slightly in recent years, according to a VAESE survey26.

While the potential of alumni to benefit current students remains somewhat untapped, some colleges and universities are doing better than others. A useful albeit imperfect metric for measuring university performance in engaging alumni is the giving rate, i.e., the share of alumni who donate to the university. The metric is used among others by U.S. News & World Report in its rankings. One could argue that if alumni are willing to give to their college or university, they may also be more willing to support current students with career advice or networking opportunities. On average, only eight percent of alumni gave to their alma mater during the 2017–2018 and 2018–2019 academic years, according to data collected by U.S. News. Data from US News’ website27 suggest that two of the top 10 schools in alumni giving rates were Catholic institutions, and a third were Christian schools. Seven of the top 10 institutions were liberal arts colleges, and the two national universities in the top 10 were comparatively small in terms of enrollment and were known to value the liberal arts. Most of these colleges and universities were highly ranked. As their graduates tend to do well on the job market, this enables them to give to their alma mater. However, there also seems to be an association between the alumni giving rate and both college size (smaller colleges seem to do better) and type (liberal arts colleges seem to do better). This is good news for Catholic colleges and universities since many are relatively small (as mentioned earlier when discussing the CIRP survey, a small college size is a criterion for some of the students that are choosing to enroll in a Catholic university), and most maintain a liberal arts curriculum.

Why may comparatively smaller institutions and liberal arts colleges do well on the giving rate? It could be that students establish stronger links with faculty and peers (other students) in comparatively smaller colleges, and the feeling of belonging may be greater. Another key factor in the relationship between alumni and their alma mater is whether students were mentored by faculty. When asked who served as a mentor to them, recent graduates in the Strada-Gallup Alumni Survey mentioned arts and humanities faculty first (43 percent), followed by science and engineering professors (28 percent) and social sciences professors (20 percent). Professors from a business field of study came last at nine percent. These statistics may be affected by the share of students selecting various fields of study, but the mentoring role that arts and humanities professors play may contribute to a comparatively stronger performance of liberal arts colleges on the giving rate. This is again good news for Catholic colleges and universities since they tend to take student mentoring seriously.

6. Conclusions

Based on data for the United States, the aim of this article was to provide a basic analysis of four key questions that prospective college students may have: (1) Should I go to college? (2) How should I select a college? (3) How can I compare different colleges? (4) Should I go to a Catholic college? Prospective students must answer these questions, and no one else can do it in their place (even if student advisors can provide some support). However, there are resources available to try to sort things out. Although the focus in the last section of this article has been on documenting some of the comparative advantages that Catholic colleges and universities may have, the goal is not to ‘oversell’ these advantages. Many Catholic institutions have core strengths, but so do other institutions, and in some areas, Catholic institutions may not be top performers. The college search process is a matter of fit between a student’s aspirations and what colleges may offer.

The sources of information discussed in the article tend to relate to the economic aspects of college education simply because this is where comparative data have been collected most systematically, but other aspects such as the opportunities provided by service learning have also been discussed. The aim of enrolling in a higher education program is not solely to prepare oneself for the labor market. However, labor market outcomes do matter. Going to college is a serious investment in both time and money and must be considered as such when making decisions. Issues of cost, debt, and expected labor market outcomes should be among the factors considered by prospective students when choosing a particular college or university for their higher education adventure. Prospective students should carefully look at the websites of the universities they are considering to better understand their programs, the courses being taught, who is teaching them, and what opportunities for extracurricular activities, internships, distance learning options, and exchange programs may be available. Ideally, students should make visits to campuses and talk to current students and alumni as well as professors.

The analysis in this article may perhaps provide useful insights for student advisors as well as college administrators apart from students trying to find institutions that will be a good fit. The fact that financial assistance, college size, and employment prospects show up high in relative differences in priorities for students enrolling in Catholic colleges is not surprising. Faith affiliation also matters for a subset of students. However, one of the other factors with a large differential in the role that it plays for students choosing a Catholic institution is particularly interesting: advice from professors matters. This is a strength that can be built up during campus visits, even when conducted remotely as was the case during the COVD-19 pandemic. The personal touch that advice from a professor can bring is more important to student choice than many campus leaders may realize. Furthermore, according to surveys of alumni, beyond college choice, mentoring provided by (especially liberal arts) professors also seems to matter for the quality of the education received.

The college/university market is becoming increasingly competitive, and this is not likely to change. However, there is a wealth of data available not only to inform students but also to guide Catholic colleges and universities in reaching out to potential students. Using these data in a more systematic way may well help Catholic (and other) colleges and universities sharpen their comparative advantage and core mission. The data and evidence reviewed in this article remain at a general level, and so do the insights that these data reveal. At the level of a particular institution or geographic market, it would be important to disaggregate the data whenever feasible. In addition, as often performed by colleges and universities through focus groups and other methods, in-depth qualitative work can be invaluable to better understand the motivations of students to choose a particular college or university, as well as the institution’s particular strengths and potential areas for improvement.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | As discussed in Wodon (2022), Karram (2011) notes that in Africa, much of the growth in private higher education can be attributed to religious institutions. Yet this is from a very low base, so that Africa is not expected to account for a large share of students enrolled in religious institutions of higher learning globally for some time. |

| 2 | The term ‘college’ is used in the American context where it means a small university, not in the French way where a college is a high school. |

| 3 | The exact count depends on which colleges and universities are included; for example some lists may include seminaries, while others may not. |

| 4 | The analysis in this article is based in part on Wodon (2021a), although the data have been updated and sections have been added, in particular on the opportunities provided by service learning and alumni networks. |

| 5 | As the children of baby boomers complete their studies, future enrollment among traditional age groups targeted by universities is expected to decline, with the pandemic having led to a further decrease in fertility rates. |

| 6 | As noted by Smith (2021), the share of the adult population identifying as Christian is declining, as are the shares of adults praying daily or considering religion as very important in their life. |

| 7 | The survey was conducted by UNESCO among member states and associate members. Among key findings, the survey found (1) an increase in the reliance on online education and hybrid modes of teaching; (2) a higher ability of universities to cope with the crisis in high income countries; (3) a drop in international mobility for students; (4) relatively mild effects on staffing; (5) disruptions in research; (6) widening inequalities in various areas; (7) sharp reduction in maintenance activities and some services on campuses; (8) more difficult transition to the job markets for students; and (9) more emphasis placed on digital strategies in a range of areas. |

| 8 | A gross enrollment ratio is the ratio of total enrollment, regardless of age to the population of the age group that officially corresponds to the level of education shown. |

| 9 | The estimate for the United States is for 2018, while those for the world and high income countries are for 2019. |

| 10 | The data in Table 2 show an association between educational attainment and labor market outcomes, but this may not necessarily reflect causality. |

| 11 | The survey has been implemented annually by the Higher Education Research Institute at the University of California for more 50 years. It is administered to first-year students before they start classes at their institution and includes questions among others on behaviors in high school, academic preparedness, admissions decisions, expectations of college, interactions with peers and faculty, student values and goals, student demographic characteristics, and concerns about financing college. |

| 12 | Results from a market research survey by EAB Enrollment Services as discussed in Redden (2019). The survey is instructive, but not nationally representative as its sample is based on the firm’s inquiry pools for Catholic colleges. |

| 13 | The data are available at https://collegescorecard.ed.gov/. |

| 14 | Surveys suggest that just under half of young adults who go to college took on some debt, including student loans, for their education. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit for the fourth quarter of 2019 shows that outstanding student loan debt rose by USD 10 billion, to USD 1.51 trillion (Federal Reserve Bank of New York 2020). The share of student loan balances transitioning into serious delinquency (90 days + past due) is at just under one in ten, but about one in five of those who still owe money are behind on their payments. Individuals who did not complete their degree or who attended a for-profit institution are more likely to struggle with repayment than those who completed a degree from a public or private not-for-profit institution (which includes Catholic colleges and universities), even including those who took on a relatively large amount of debt. When considering the choice of a particular college or university, careful attention needs to be paid to the cost of enrollment (tuition and other costs) and the expected earnings upon completion. The data are based on school-reported information and the U.S. Department of Education cannot confirm the completeness of data being reported. |

| 15 | The tool is at https://cew.georgetown.edu/cew-reports/collegemajorroi/. It is based on Carnevale et al. (2020a). |

| 16 | There is a lively debate on the value, robustness, and potential negative effects of many of those rankings, but this debate will not be dealt with here. |

| 17 | Apart from a wide range of college rankings, there are also a wide range of college guides, some of which may again be more useful than others. While these guides may be well known to American students, they may not be well known among international applicants to American colleges and universities. Two widely used guides are The Princeton Review: The Best [386] Colleges, and The Fiske Guide to Colleges. Both guides go beyond academics to provide a description of other aspects of the college experience at different institutions. |

| 18 | See https://www.aacu.org/trending-topics/high-impact. While service learning is considered a high impact practice by AACU, robust evidence on the impact of the practice remains limited. A review for business schools by Marco-Gardoqui et al. (2020) suggests benefits for students, but many of the studies included in the review were qualitative or small scale. Using more stringent criteria (i.e., considering only randomized controlled trials), Filges et al. (2022) suggests that for K12 education, the available evidence so far does not conclusively establish that service learning programs improve student outcomes. Common sense and lessons from good practices suggest that service learning could generate benefits for students, but more research is needed to establish that this is indeed the case. |

| 19 | Service is mentioned as a pillar of the culture of encounter by Pope Francis (2019) in calling for a Global Compact on Education and is a key theme in Fratelli Tutti (Francis 2020). Service learning is also explicitly mentioned in the Vademecum from the Congregation for Catholic Education (2021) for the Global Compact on Education. |

| 20 | The eight areas were: First-Year Experiences, Co-ops/Internships, Learning Communities, Senior Capstone, Service Learning, Study Abroad, Undergraduate Research/Creative Projects, and Writing in the Disciplines. |

| 21 | The ranking is at https://www.usnews.com/best-colleges/rankings/service-learning-programs. |

| 22 | On an experience of service learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, see Tian and Noel (2020). |

| 23 | This section builds on Wodon (2021b). |

| 24 | A donor-advised fund is a giving account that individuals can establish with a public charity. The donors make a charitable contribution to the charity (which is eligible for a tax deduction) and use the fund to recommend grants to other charities over time. |

| 25 | Information on the Strada-Gallup Alumni Survey is at https://news.gallup.com/reports/244058/2018-strada-gallup-alumni-survey.aspx. |

| 26 | Results from the VAESE survey are available at https://www.alumniaccess.com/vaese_alumni_study_download. |

| 27 |

References

- Aparicio Gómez, Rosa, and Andrés Tornos Cubillo. 2014. Youth Cultures in Catholic Universities. A Worldwide Survey. Madrid and Paris: La Quinta Tinta/CCR-IFCU. [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale, Anthony P., Ban Cheah, Martin Van Der Werf, and Aartem Gulish. 2020a. Buyer Beware: First Year Earnings and Debt for 37,000 College Majors at 4400 Institutions. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale, Anthony P., Megan L. Fasules, and Kathryn Peltier Campbell. 2020b. Workplace Basics: The Competencies Employers Want. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. [Google Scholar]

- Congregation for Catholic Education. 2021. Global Compact on Education Vademecum. Rome: Congregation for Catholic Education. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York. 2020. Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit, 2019: Q4 (Released February 2020); New York: Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

- Filges, Trine, Jens Dietrichson, Bjørn C. A. Viinholt, and Nina T. Dalgaard. 2022. Service Learning for Improving Academic Success in Students in Grade K to 12: A Systematic Review. Campbell Systematic Reviews 18: e1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis. 2019. Message of his Holiness Pope Francis for the Launch of the Global Compact on Education. Rome: The Vatican. [Google Scholar]

- Francis. 2020. Encyclical Letter Fratelli Tutti of the Holy Father Francis on Fraternity and Social Friendship. Rome: The Vatican. [Google Scholar]

- Freeland Fisher, Julia, and Richard Price. 2021. Alumni Networks Reimagines: Innovations Expanding Alumni Connections to Improve Postsecondary Pathways. San Lexington: Christensen Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Jonathan P. 2009. Higher Education as Moral Community: Institutional Influences on Religious Participation During College. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 48: 515–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Federation of Catholic Universities Foresight Unit. 2021. Q1-2021 Trends in Higher Education/Tendances de L’enseignement supérieur/Tendencias de la Educación Superior. Global Catholic Education Knowledge Note. Washington, DC: Global Catholic Education. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, Rhonda H., and Douglas Jacobsen. 2012. No Longer Invisible: Religion in University Education. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Karram, Grace. 2011. The International Connections of Religious Higher Education in Sub-Saharan Africa: Rationales and Implications. Journal of Studies in International Education 15: 487–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, Susan, Anu Madgavkar, James Manyika, Sven Smit, Kweilin Ellingrud, Mary Meaney, and Olivia Robinson. 2021. The Future of Work after COVID-19. New York: McKinsey Global Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Mabille, François, and Montserrat Alom Bartroli, eds. 2021. Towards a Better Understanding of Youth Cultures and Values. Paris: CIRAD-IFCU. [Google Scholar]

- Marco-Gardoqui, Marta, Almudena Eizaguirre, and María García-Feijoo. 2020. The Impact of Service-learning Methodology on Business Schools’ Students Worldwide: A Systematic Literature Review. PLoS ONE 15: e0244389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayrl, Damon, and Freeden Oeur. 2009. Religion and Higher Education: Current Knowledge and Directions for Future Research. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 48: 260–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellul, Corinne. 2022. The Post-Covid-19 World of Work and Study: IFCU 2020–21 Report. Paris: International Federation of Catholic Universities. [Google Scholar]

- National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. 2022. Overview: Spring 2022 Enrollment Estimates. Herndon: National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Hoa, and Quentin Wodon. 2018. Faith Affiliation, Religiosity, and Altruistic Behaviors: An Analysis of Gallup World Poll Data. Review of Faith & International Affairs 16: 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Redden, Elizabeth. 2019. Conservative. Traditional. Expensive. Inside Higher Ed. Posted February 11. Available online: https://www.insidehighered.com/admissions/article/2019/02/11/survey-asks-how-prospective-students-and-their-parents-view-catholic (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Secretariat of State [of the Vatican]. 2022. Annuarium statisticum Ecclesiae 2020/Statistical Yearbook of the Church 2020/Annuaire Statistique de l’Eglise 2020. Rome: Libreria Editrice Vaticana. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Gregory A. 2021. About Three in Ten U.S. Adults Are Now Religiously Unaffiliated. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Sommerville, C. John. 2006. The Decline of the Secular University. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stolzenberg, Ellen B., Melissa C. Aragon, Edgar Romo, Victoria Couch, Destiny McLennan, M. Kevin Eagan, and Nathaniel Kang. 2020. The American Freshman: National Norms Fall 2019. Los Angeles: Higher Education Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Qianhui, and Thomas Noel Jr. 2020. Service-Learning in Catholic Higher Education and Alternative Approaches Facing the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Catholic Education 23: 184–96. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2021. COVID-19: Reopening and Reimagining Universities, Survey on Higher Education through the UNESCO National Commissions. Paris: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Wodon, Quentin. 2020. Enrollment in Catholic Higher Education: Global and Regional Trends. Journal of Catholic Higher Education 39: 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Wodon, Quentin. 2021a. Directory of Catholic Colleges and Universities in the United States 2021. Washington, DC: Global Catholic Education. [Google Scholar]

- Wodon, Quentin. 2021b. Engaging Catholic Higher Education Alumni: Should We Organize Ourselves Better? Update: The Newsletter of the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities, Fall. Washington, DC: Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities. [Google Scholar]

- Wodon, Quentin. 2022. Catholic Higher Education Globally: Enrollment Trends, Current Pressures, Student Choice, and the Potential of Service Learning. Religions. forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- ZIGLA. 2019. Mapping, Identification and Characterization of Service-learning in Higher Education: Final Report. Buenos Aires: ZIGLA. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).