Abstract

Since the supreme leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) called on the clergy to embark on an online jihad to rescue youngsters trapped in the “killing field” of the internet, a vast number of clerics and state-sponsored religious organizations and actors have expanded their online activities. The growing body of Islamic online contents produced by the IRI’s promoters and the proliferation of social media-related practices in religious places and events have shaped the online visual culture of the Iranian revolutionary youths. To explore this under-researched area, this study concentrates on three sets of visual tropes: (1) selfies with martyrs, (2) selfies taken by revolutionary clerics in disaster-stricken areas, and (3) shared images of the holy shrine of Imam Reza on Instagram. In addition to online documents (including posters, photographs, and reports), the data includes selectively chosen Instagram postings retrieved by searching pertinent accounts, hashtags, and locations on the platform. The investigation inquires the ways in which online image-making has been incorporated in the construction of holy sites and the culture of sacrifice and martyrdom propagated by the IRI as ideal youth aspirations. The findings demonstrate the extensive appropriation of social media and intensive integration of online image-making in this field. The study contributes to understanding of the online spaces and practices aimed at extending the influence over the online youth culture in Iran in line with the IRI’s cultural plans and policies.

1. Introduction

With over 4.6 million followers and seven thousand posts on his Farsi profile, Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Seyyed Ali Khamenei, has Instagram accounts under his name in ten languages, including English, French, German, Turkish and Russian.1 Alongside his vicarious deployment of Instagram, Khamenei has ordered the Iranian nation to “draw up battle array in front of the positioned enemy” in the virtual space.2 He has recently addressed Iranian youths as “officers of the soft war” and urged them on several occasions to exploit advantages of virtual spaces for “explanation of the truth”, where “the enemies of Iran and Islam” allegedly misinform the nation.3 In line with the supreme leader’s concern about the production of proper online contents, particularly by youths and Islamic seminaries,4 many Iranian clerics and religious cultural institutions, such as holy shrines, have set out to appear on the internet. The holy shrine of Imam Reza (765−818 CE), the 8th Imam of Shia in the city of Mashhad, which is the most important shrine in Iran, has a profile with over 731,000 followers and 5112 posts.5 In the second place, the holy shrine of his sister, Fatima Masumeh (790–816 CE), in the city of Qom has an Instagram profile with over 125,000 followers and 2945 posts.6

In this context, this study examines the visual contribution of religious state-sponsored online actors by focusing on online images and the Instagram postings coming from two interconnected epicenters: Firstly, Iranian revolutionary cleric Instagrammers, who follow the supreme leader’s call for the online jihad, and secondly, holy shrines, which are popular religious places administrated by the IRI and utilized for cultural and political purposes. With regards to recent literature on youth culture and media, this investigation contributes to the representations of young people as an “ideological vehicle”, with youths celebrated as the invigorating precursor to a prosperous future (Osgerby 2020), which in the IRI’s view is the Iranian Islamic civilization. Although youths are deemed vulnerable to dangerous “media effects”, through the usage of media they engage in processes of identity construction and cultural creativity (ibid; Subrahmanyam and Šmahel 2011). After charting the tensions in the virtual landscape of religious promotion in Iran, the study inquires (1) what types of image-spaces have been constructed by Iranian revolutionary clerics through the practice of smartphone image-making in order to shape the online youth culture? (2) what types of gestures and dispositions have been framed in shared images of the holy shrine of Imam Reza by and of young people?

1.1. The Online Jihad, Iranian Clerics and the Youth

Given their pronounced opposition to the “Western culture”, the presence of Iranian clergymen on Instagram, a US-based social networking platform, seems paradoxical. The clerics’ exploitation of Instagram, however, is justified as fighting the media war imposed by the US since the establishment of the Islamic Revolution.7 Iran’s supreme leader has described media, ranging from radio to online social networks, as the recent kinds of weaponry employed by the enemy to influence the nation’s public mind.8 He once illustrated the virtual space as “the killing field of youngsters and youths.”9 In the Second Phase of Revolution Statement, addressed to the Iranian nation in 2019, he urged youths to break the media siege as “the first and most fundamental Jihad.”10 He has asserted that the most important duty of clergymen is to counter the enemy and to rescue the youths in virtual spaces.11

The media war on and with Instagram markedly intensified just after the assassination of Major General Ghassem Soleimani, the late Quds Force commander, by the US military in Iraq in 2020. In response to his unexpected loss and to commemorate his martyrdom, many of his grieving supporters posted pictures of him, many of which were immediately removed by Instagram, flagged as being against its Community Guidelines on “violence and dangerous organizations.” Some of the Instagram pages were temporarily blocked and the main hashtags utilized for him in Farsi and English are kept hidden and inaccessible on the platform until now. In this context, posting the contents that will be removed by Instagram has emerged as a digital form of offensive in the media war. As the head of the Online Camp in the Basij (an Iranian paramilitary volunteer organization) has put it:

Today we can take advantage of the online platforms that we once considered as a threat and wanted to block. […] Instagram had to remove 13 million of our posts and Twitter had to block ten thousand of our accounts. This demonstrates that we have success over the enemy in the virtual space.12

However, Internet platforms have opened up alternative spaces for nonconformist clerics to reach young audiences online, too. Hassan Aghamiri, a dissident cleric nicknamed the “Telegram Cleric,” became famous amongst young social media users. He criticized Iranian religious authorities and the socio-political governing body on many issues such as neglecting places for youth recreation and entertainment while over-constructing mosques and Islamic schools. Put on trial by the Special Clerical Court, Aghamiri was convicted of offenses such as “spreading lies, disturbing the public mind, and shaking youths’ religious faith.”13 Subsequently, the court divested him of his clerical uniform. After his conviction, however, he became even more popular and gained a larger number of followers on Instagram, where he livestreams his speeches.14 Presenting himself as an owner of a honey production business, he has framed his religious activities as unsalaried public service. With over 3.7 million followers, several of his Instagram videos are viewed exceeding 1.5 million times. Using the online platform, he has managed to construct an unprecedented public image of a popular, dissident cleric who communicates with large groups of audience independent of state-controlled media.

Online platforms have let surface the serious offline tensions between clerics and dissatisfied groups of Iranian society, which is not allowed to be discussed in the IRI’s official media. Given the increasing public discontent, clergymen, as a perceived symbols of the Islamic political authority, have been treated with wariness and disrespect by people in public places. The severity of the tensions has led to multiple altercations, physical confrontations, and even a few cases of clerics’ murders.15 The motive of a fatal knife attack in 2017 was confessed as killing a person who was merely assumed to be an authority.16 Mohammad Reza Zaeri, a conservative but dissident cleric, described people’s negative attitudes towards himself in an Instagram post on 6 January 2022:

In the past ten days, I was once spat on and a couple of times severely humiliated and cursed. Even now a Snap (an Iranian online taxi app) driver dropped me midway on my route in a bad manner. Are the ones who must comprehend [the gravity of the situation] even slightly aware of the increasing degrees of ravaging hatred and disgust, about which we (critical clerics) had warned? No.17

In response to the defamation, many clerics have set about offering public services to enhance their social image offline (Lebni et al. 2021) and online.

Accordingly, the online presence of Iranian Shia clerics builds up around three epicenters of tension: the confrontation with the “Western enemies” in defense of religious and ideological values, the internal tension between traditional clerical establishments and non-conforming clerics, and the conflicts between unsatisfied groups of people and clerics.

1.2. The Culture and Politics of Shia Holy Shrines in Iran

Holy shrines (haram) mark the most sacred type of religious spaces in contemporary Iranian culture. They pivot around holy tombs, which are associated with the Prophet, an Imam (the most important figures in Shia Islam following the Prophet), or a descendant of them (imamzadeh). Providing great sources of religious emotion and identification, they attract people of various social fractions and faith groups, and consequently are “unique platforms for the performance of romantic, passionate, creative, inventive, enchanted, imaginative thoughts and wishes of pilgrims and visitors” (Stadler 2020, p. 2). Holy shrines possess psychological and sociological functions by providing visitors with feelings of calm and confidence. As for the sociological function, adults and particularly young people spend their leisure time in the shadow of religiosity and spirituality (Shaker 2005). Rituals such as collective praying create a sentiment of social solidarity and integrate individuals with groups of people beyond friends and associates (Vasigh 2020, p. 242). Shia Muslims believe that their Imams are “still alive”, as noted in the Quran (3: 169). So, during the time of visiting, they find themselves in the presence of the Imam: Pilgrims are seen, listened to, and responded to by him, although he is not perceptible. Holy shrines are therefore sites of divine presence, where people seek connections or feel in contact with God or with Imams (Honarpisheh 2013).

Holy shrines have been utilized as a practical and discursive instrument for the implementation, expansion, and establishment of the IRI’s religious values in public spaces, many times against secular youthful activities and events. Denouncing recreational trips in universities, the supreme leader urged visits to Mashhad for the sake of spiritual achievement.18 Ahmad Alamolhoda, an ultra-conservative cleric and the Friday prayer leader in Mashhad, has strongly objected to holding concerts in Mashhad as disrespecting Imam Reza and the religious identity of the city.19 In 2016, he asserted that Mashhad is not touristic, but it is a city of ziyarat (pilgrimage) and sacredness. Addressing urban planners and managers, he also condemned the development of recreational centers in the city as a war campaign against Imam Reza. Subsequently, the then minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance canceled concerts in Mashhad.20

Given that holy shrines are administrated under the control of official Islamic organizations, they are impregnated with political and ideological motives. The head of the Endowment and Charity Organization, Seyyed Mahdi Khamushi, who appoints holy shrines administrators nationwide, has urged them to humbly follow the supreme leader’s directions and assist the conservative President Raeisi.21 At an international level, the popularity of holy shrines has been employed for the expansion and justification of the IRI’s foreign policies. The Iranian involvement in the Syrian civil war in support of Bashar al-Asad was framed as “defending the shrine of the God’s family” since the shrine of the first Imam’s daughter, Zaynab bint Ali (626–682 CE), is in Damascus. By extension, the troops and young volunteer fighters mobilized and recruited for the Syrian war are referred to as the “holy shrine’s defenders” in the IRI formal discourse.22 Accordingly, holy shrines and clerics are employed as apparatuses of influence on religious youth culture in Iran.

1.3. Religion, Media, and the Online Space

The vast and ubiquitous use of social media in all social and cultural spheres have channeled researchers’ attention towards the consequences of online media on religious deeds, belief communities, and faith authorities. Within the growing literature on religion, media and culture, the theoretical framework of mediatization, to frame media spaces as agents of religious change (Hjarvard 2008), has gained substantial recognition (Lövheim and Lynch 2011; Couldry and Hepp 2013; Hjarvard 2016; Mishol-Shauli and Golan 2019; Rota and Krüger 2019). Following Bruno Latour (2007), however, the way in which processes of mediatization restructures the social is viewed as a field with a variety of potential agents for action (Krotz and Hepp 2011).

Academic interest in the usage of online platforms by Muslims who live in non-Muslim countries revolve around three major causes (Evolvi and Giorda 2021): First, the ways Muslims utilize digital media for gaining knowledge about Islam (Echchaibi 2011; Bahfen 2018); second, the expansion of the intersection of offline and online Islamophobia in the wake of the proliferation of online practices, including acts of threat, discrimination and abuse against Muslims and the imposition of stereotypes (Awan 2014; Evolvi 2019; Elfenbein et al. 2021); and third, the utilization of online tools for resisting stereotypes by Muslims in European and North American societies, responding to hate, integrating into society, as well as normalizing the practice of “lived Islam” in everyday settings (Van Zoonen et al. 2011; Evolvi 2017). This cause manifests itself in the online presence of Muslim women who wear hijab to consolidate agency and gain visibility (Echchaibi 2013; Wheeler 2014; Peterson 2016, 2020).

Many Muslims view social media as a double-edge sword, providing opportunities to expand intercommunal contacts and access to religious sources, while also diluting the quality of affiliations and increasing exposure to distractions (Ferguson et al. 2021). Islam on Instagram has been researched by Indonesian scholars, highlighting the constructive effects on the consolidation of religious communities. Millennial Muslims have established online faith movements on Instagram (Rahman et al. 2021). Solahudin and Fakhruroji (2020) argue that despite the expectation that religious populism on social media poses a challenge to authoritative figures and religious institutions, traditional offline Islamic authorities remain to be the prime source of online religious practices in Indonesia. Putri and Sunesti (2021) observe that Instagram-based advertisements of sharia housing, a new trend in Indonesian Muslim communities, has led to the construction of a collective devotional identity through the popularization of the image of a halal lifestyle. Having investigated the media activities of Instagram da’wa (proselytization) activists, Nisa (2018) maintains that Instagram affords Indonesian Muslim women an alternative space to establish their identity as strictly pious and virtuous Muslims and causes the convergence of religiousness and consumption through branding an online market for hijabi lifestyle. By contrast, Women in Mosques, an online campaign in Turkey, encourages women to share experiences of marginalization in mosques inflicted by the patriarchal gendered organization of the religious space (Nas 2021).

The distinction between online religion and religion online has been underscored in the field of media and religion studies (Helland 2000). While the former provides information about religion by referring to offline traditions, the latter affords opportunities for participation in online religious activities (Young 2004). Religion online is described as the online function of traditional religious communities which exist primarily in physical spaces for exhibition of their religious identities and expansion of community outreach on digital media (Frost and Youngblood 2014). Online religion, however, refers to religious practices which are performed using the conduit of the internet (Campbell 2012). This tension suggests that online platforms can not only provide supplements but can also substitute for offline religious communities. The shift from the offline space to the online signals two major social ramifications: a crisis of authority and a crisis of authenticity (Dawson and Cowan 2004). Authority is challenged because there is not any procedure through which the information and performance posted online can be vetted by established religious institutions beforehand. Authenticity is impaired because people with any kind of religious background can appear in online communities and produce religious contents. Hence, the concept of networked religion has been introduced to encapsulate the way religion functions online as loose social networks with varying degrees of religious affiliation and commitment, malleable identities, challenged authorities, and a self-directed form of engagement (Campbell 2012).

The online and offline are no longer seen as completely distinct fields of practice (Campbell and Lövheim 2011). Considering the integration of online and offline spaces, the notion of onlife interconnections proves to be constructive as it points out to the blurring distinction between reality and virtuality and insists on the developing entanglements between humans, machines, and nature (Floridi 2015). On that basis, the term digital religion is proposed to indicate “the technological and cultural space that is evoked when we talk about online and offline religious sphere have become blended and integrated” (Campbell and Evolvi 2020). Current approaches to studying the online-offline relations have been articulated through three areas of inquiry (Campbell and Lövheim 2011): (1) How new, digital media are becoming embedded in contemporary religious life? (2) How do technology and religion shape each other? (3) How does the internet change or enhance tendencies, dimensions, and identities already existing in offline religious domains? Accordingly, this study sets out to inquire these questions concerning the religious youth culture unfolding on Instagram.

1.4. Existing Research on Online Shia Iranians and Instagram

The integrated usage of media in religious rituals in Iranian Islamic culture has been noted in several studies by Iranian scholars. It has been observed that the practice of visiting holy shrines has become a participatory performance in which pilgrims inside the shrine let their friends and family join in their spatial experience through phone calls, sharing images, and selfies (Ghazvini 2019). Several studies demonstrate the adverse effect of the usage of Instagram on Islamic identity and commitment amongst Iranian youths (Saei et al. 2020; Sharifi et al. 2018). It has been established that the “uncritical consumption” of Instagram has an adverse influence on the observance of Islamic hijab (Far et al. 2019). A study on young populations of 19–29 year-old in Tehran and four major cities indicates that the active use of Instagram causes deviation from “traditional” religiosity in four dimensions of beliefs, values, norms, and symbols (Mollabashi et al. 2020).

An exploration of Instagram activities of Iranian clerics demonstrates that using the platform clergymen present new types of personal, familial, and social selves, which are performed relatively independently of their traditional communities and institutions (Kazemi et al. 2019). The social self of clerics is especially highlighted as Instagram provides the chance of communication with wide-ranging groups of people in comparison to traditional media and offline spaces. According to this study, as clerics try to amend and enhance their social image, they show a significant tendency towards celebrity culture. Moreover, the fragmented nature of Instagram space has made them transform their religious activities from verbal to practical forms. An examination of an Instagram Live between a cleric and a female singer (respectively Hassan Aghamiri and Ahlam) shows that the online conversation and singalong led to the “explosion and fusion of religion and music spheres”, which are traditionally deemed as opposing (Badinfekr et al. 2021).

An exploration of Instagram postings of participants in Arba’in’s Pilgrimage, an annual public walk towards the city of Karbala in Iraq with millions of partakers, points out three impacts of mobile image sharing on the ceremony: Photographs taken with celebrity participants cause desacralization of the pilgrimage, the individual practice of selfie-making reconstruction of religious identity, and instagramming results in the popularization, aestheticization and expansion of the ritual (Movahed et al. 2020). Narges Valibeigi (2018) has researched the presentation of Shia Iranians on Instagram, investigating the ways in which the practice of photo sharing has shaped the manner and experience of being religious. Her focus is set on three photographic tropes, all of which pertain to the rituals performed for Imam Hossein, the third Imam of Shia. She argues that Instagram has become a sacralized medium and an environment with the capacity for reflecting religiosity and connecting Shia believers to each other, which simultaneously contributes to the desacralization of religious concepts by making religious images accessible anywhere at any time. Considering the limited scope of the published studies on internet platforms and religiosity in Iran, the investigation of the online culture of Shia Iranians proves to be an under-researched field of study.

2. Materials and Methods

The following investigation is a “small data” analysis conducted with a visual anthropological perspective (Utekhin 2017). The main material comes from online images published by official Iranian news agencies concerning selfies in the Islamic culture. In addition, the following Instagram feeds were chosen as sources of Instagram posts:

- https://www.instagram.com/imamreza_ir/ (accessed on 17 May 2021) a public Instagram account “dedicated to Imam Reza” as a media center of the holy shrine, with 2935 posts and 172k followers

- https://www.instagram.com/moradishahab/ (accessed on 17 May 2021) the profile of a popular pro-state cleric, with 1147 posts and 447k followers

- https://www.instagram.com/explore/tags/اول_بیل_بزن_بعدا_حرف_بزن/ (accessed on 17 May 2021) a hashtag coined by Seyyed Komeil Mousavi, a revolutionary cleric, with 2929 posts

- https://www.instagram.com/explore/locations/1311987612260369/ (accessed on 18 January 2022) the location page of the holy shrine of Imam Reza on Instagram.

A collection of 160 postings were manually selected with regards to the inclusion of three components: (1) spatial elements and arrangements concerning the representation of the youth, (2) depiction of the practice of mobile image-making by religious actors and visitors, and (3) representations of gestures in holy sites. The method of analysis is based on visual social semiotics (Rose 2016) with an emphasis on spatial elements and relations, bodily positions, and gestures.

With an embodied-spatial approach (Low 2016), the study concentrates on spaces constructed through online images, created by the practice of image-making, and formed through Instagram affordances. Employing a qualitative method of visual analysis based on social semiotics (Rose 2016), the investigation inquires the following questions: (1) What types of spatial elements, relationships, arrangements, and gestures are accentuated within shrine images? (2) What types of Instagram-based functions are utilized for religious rituals in holy shrines? (3) What is the influence of Instagram-related practices on holy shrines and sacred sites? (4) What types of spatial elements, relationships, arrangements, and gestures are framed in revolutionary clerics’ shared images?

3. Results

3.1. Selfies in Disaster: Clerics Shoveling in the Mud

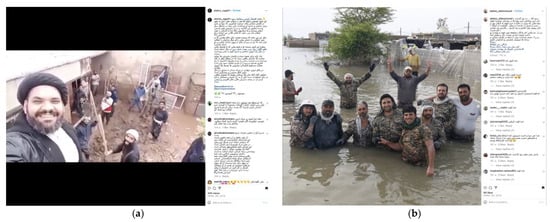

A central theme which in the online social imagery of revolutionary clerics is the presentation of volunteering public service, especially in underprivileged and disaster-stricken areas. In the spring of 2019, after wide areas in the west of Iran were flooded, many different groups of people across the country came up to the disaster-stricken regions to help. Through their Instagram activities, revolutionary clerics tried to bring their presence into the limelight online. With several clerics working in the mud in his background, Seyyed Komeil Mousavi, a former officeholder in the Islamic Development Organization, posted a selfie video apparently in one of the flooded houses (Figure 1a).23 Addressing dissident influencers including actors and filmmakers, he states in the video that while celebrities are complaining comfortably at home and not offering any help, the ones who are frequently attacked by their criticism are working hard on site. Then, the working clerics complete his message by chanting a slogan together while moving their shovels in the air: “First shovel, then complain.” In the end, Mousavi concludes the video by reiterating and hashtagging the slogan.24

Figure 1.

Images shared with the hashtag “First shovel, then complain”: (a) The video selfie made by Seyyed Komeil Musavi, which is reposted by an Instagram user to criticize it as an act of pretention. The original post by Seyyed Komeil Musavi is not available anymore. Source: https://www.instagram.com/p/BwuiOPIgkTg/ (accessed on 17 May 2021). (b) Image with the same hashtag, taken by a group of members of the IRGC in flood-stricken areas in south-western Iran. Source: https://www.instagram.com/p/Bw4Ts3tAAiK/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link (accessed on 17 May 2021).

Parviz Parastui, one of the well-known actors addressed by Seyyed Komeil Mousavi, reposted the video to criticize it as a useless, hypocritical pretention.25 If the clerics truly follow the original Islamic role models, he wrote in the caption, they must not exhibit their righteous conducts.26 In response, another jihadi cleric posted a video of himself on the back of a pickup, having a bandaged hand, and driving on a bumpy road; all signs of being immersed in a help operation on site. In the video he declares:

Many ask [suspiciously] why clerics wear the turban when they are shoveling to help flood-stricken people. [They believe] this is an act of hypocrisy. They question because they intend to induce [the false impression that] clerics are indolent parasites with no empathy for people’s sufferings. With their conducts, however, the clerics have indeed proved the opposite: the clergy is from and for people. All my fellow clerics should shovel with the turban.27

With presenting themselves as being in service of the public good and through the emphasis on their outfit as a fundamental element of their identity, clerics have tried to re-brand the clergy as social helpers. This is understood as a practical response to the public criticism on social media regarding the budgets allocated to religious organizations and questioning their actual public benefit. Moreover, shared images of helpers in disaster-stricken areas represent young affiliates of the IRGC (Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps) as selfless helpers who are ready to sacrifice themselves and save their people (Figure 1b).

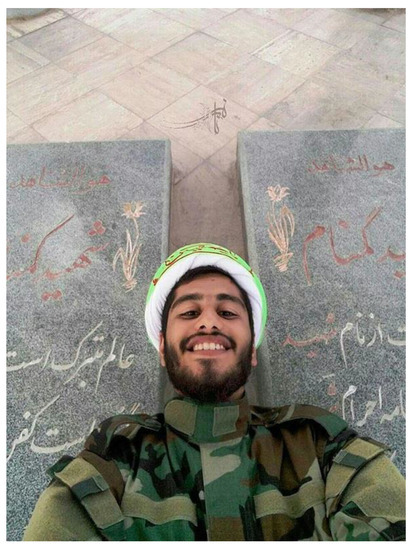

3.2. Taking Selfies with Martyrs

In 2016, DEFA Press (Sacred Defense News) published a selfie taken by Saeid Bayazizadeh, a 22-year-old seminary student, who joined Iranian troops operating in Syria. He made the selfie while placing himself on the ground between the gravestones of two unidentified martyrs buried in his military training camp (Figure 2). After joining the troops, according to DEFA Press, he was killed in Syria too. The article is concluded by posing a rhetorical question: “And what do you and I know? Maybe these two martyrs mediated the great blessing [of martyrdom] that was granted to this basiji seminary student”.28 Apparently, this was the first time that the culture of martyrdom in Iran was materialized in a selfie format and received public attention. So, taking selfies with martyrs’ graves is not only framed as a way of joining them in a symbolic cultural fashion, but it is also introduced as a practice with actual effects, which is the blessing of becoming a martyr.

Figure 2.

The selfie taken by Saeid Bayazizadeh, a seminary student who was reportedly martyred in Syria. While lying on the ground, he locates himself between two gravestones of “unidentified martyrs” buried in his military training camp. source: https://defapress.ir/fa/news/108536/سلفی-یک-شهید-با-شهدای-گمنام-عکس (accessed on 17 May 2021).

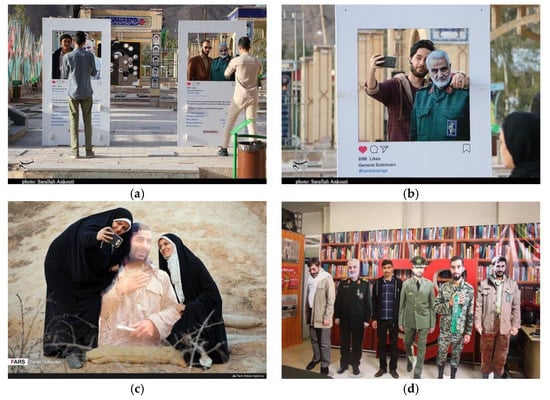

IRI’s cultural institutions have tried on many occasions to appropriate the practices of selfie taking and photo sharing for the popularization and celebration of of the culture of martyrdom. In March 2018, for example, the Foundation of Martyrs and Veterans in the city of Kashan organized a contest entitled “selfies with martyrs’ mothers”.29 In the next year, Mohammad Rasulollah Division, a division of the IRGC in Tehran, organized another contest under the title “selfie photos and videos with martyrs’ images”. In the announcement videoclip, while young people are cleaning martyrs’ graves and putting red roses and petals on the gravestones, they pose and take gestures for capturing photos and selfies.30 In the final scene of the video, a group of youths come together in front of a monument dedicated to martyrs in Tehran cemetery of Behesht-e Zahra and gather around an old man in a wheelchair, who is supposed to be a veteran of the Iran-Iraq War. Using a selfie-stick, the veteran then takes a selfie. Another example of taking photos with martyrs took place in Tehran Book Fair 2019, where a publisher decorated its exhibition section by arranging five life-size cut-outs of martyrs for visitors to take selfies and photos with (Figure 3d). Cut-outs of martyrs have also appeared in the southeast of Iran, at the location of former war zones of the Iran–Iraq War (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

Selfie taking with martyrs’ cut-outs: (a) Instagram stands located at the burial site of Ghassem Soleimani. Source: Tasnim News; (b) A young man taking selfie with the cut-out of Ghassem Soleimani at his burial place, while putting his arm on the martyr’s shoulder. Source: Tasnim News; (c) Female visitors taking selfies with a martyr cut-out in the southeast of Iran on their visit to former war zones of the Iran-Iraq War. Source: Farsnews; (d) A young man (third from the left) standing among the cut-outs of martyrs in Tehran Book Fair. Source: Navid-e Shahed.

The cut-out of Ghassem Soleimani was once placed on his burial site in the city of Kerman, printed on a stand and framed in the iconic graphic design of Instagram interface, according to an illustrated report by Tasnim News in 2020 (Figure 3a,b).31 The negative space inside the framework was cut out in order for visitors to stand beside the image of the martyr and take photographs with him. The Like icon under the image counts 85 million times of likes, which amounts to the round number of the total population of Iran. The hashtag underneath reads #hardrevenge, which was the motto utilized by IRGC commanders against the US after Soleimani’s assassination. The caption is a quotation from Ayatollah Khamenei translated in English: “We should view our dear Shahid Sardar (martyred General) as a school of thought, as a guideline and as an instructive lesson.” In this case, the aesthetics of Instagram platform and the practice of smartphone photography are integrated into the rituals of visiting the sacred site dedicated to Ghassem Soleimani.

3.3. Smartphone Photography in the Holy Shrine

Before the advent of the mobile phone camera, photography was prohibited in the holy shrine and carrying analog or digital cameras, as the only available tool for photography, was forbidden. Since the emergence of mobile phone cameras, however, image-making has become a popular, integrated practice in the shrine. By sharing a short video depicting people surrounding him and taking selfies, Shahab Moradi, a popular pro-state cleric, describes his experience of public photography as a religious celebrity in Imam Reza holy shrine:

I take photos with people every day, either selfies or group photographs. This is inevitable when one is famous. […] Sometimes I really get tired of it. For example, sometimes in the holy city of Mashhad it takes me three or four hours to get to the shrine.32

As such, image-making is not only utilized as a way of consolidating the popularity of clerics, but it is also framed as a legitimate practice to be performed in holy shrines.

A string of personal anecdotes, posted on a personal blog in 2013, critically delineates the author’s experience of witnessing smartphone photography in the holy shrine:33

[…] some [visitors] are so unaware of the place they are. As if visiting a historical building, they come in, look around, and take photos regardless of their position in the Shrine; no matter if turning their back to the zarih (the burial chamber). God forbid shrine’s servants are not present; then there won’t be any place left for praying and greetings [to the Imam]. […] Once in front of the zarih was packed with people holding mobile phones in hands and posing for souvenir photos. I do not disagree with photography in holy places, but I reject disrespect and desecration. Why do we downgrade places of sanctity to historical and recreational attractions?

Further, the author points out to the way in which the use of smartphones may impair the sacredness of the shrine:

I remember a person filming the zarih. Then, on his mobile screen I saw a picture of a Western woman with an obscene appearance. Does he believe in the truth of Imam Reza and his immortal presence [in the shrine]? If his spirit is not touched [by the Imam’s presence] in the shrine, at least he should change his mobile phone’s background.

The writer explains that the practice of smartphone photography undermines the sacredness of the holy shrine in three ways: firstly, by causing distractions from the holy presence of the Imam, secondly, through the “inappropriate” gesture of photography, which is associated with touristic sites, and thirdly, through the possible display of improper profane images. Interestingly, the author concludes the post with a comparison of shrine photography in the age of smartphones with the offline traditional pilgrimage photography in the past. Pilgrimage or shrine photography as one of the most popular vernacular genres of Iranian photography had emerged even before the popularization of analog cameras (Eshaghi 2015). The old type of shrine photography was performed either on nearby roofs overlooking the shrine’s dome or in photo studios around the shrine. In studios people would stand in front of a backdrop with a painted image of the shrine or zarih on it and make a serious, respectful pose. This way, the space of image-making and the space of ziyarat were completely separated from each other. The photograph would be carried home and positioned in a special place and kept as a cherished object. In addition, the fanciful painting in the background gave space to creative religious imagination through the representation of stories about Imam Reza (Nazarali 2016).

3.4. Instagramming Ziyarat

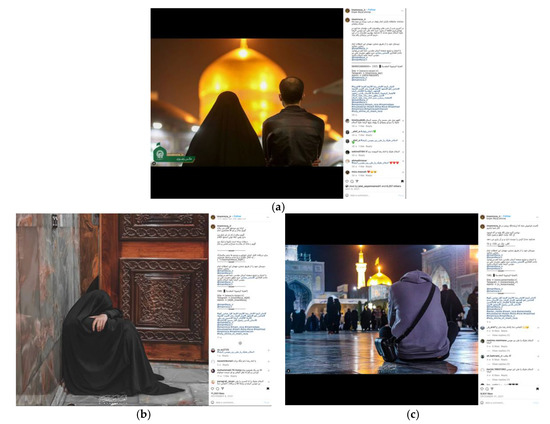

In addition to the official account run in the name of the Imam Reza shrine administration,34 many images are posted of the holy shrine by Instagram users marked with pertinent locations and hashtags.35 There are also several Instagram pages dedicated to the holy shrine, which present examples of employing Instagram-based practices and functions for the purpose of mediated pilgrimage. For instance, two expressions reappearing in the captions on “Imamreza_ir” account indicate the instagrammization of the visiting rituals: “By mentioning your friends, invite them to these moments of Imam Reza” and “By spreading and publicizing the account of the holy shrine you can be an honorary servant of the #virtual_courtyard (in Farsi) of the pure shrine of Imam Reza.”36 This way, the Instagram profile has been integrated into the physical domain of the holy shrine as a virtual courtyard along with the physical ones and a certain tract of the Instagram terrain is territorialized as a sacred space. This is not only an attempt to utilize the platform in favor of religion, but it also forms a type of mediated, instagrammed visit.37 In the same line, a frequent theme on the profile is dedicated to the vicarious visit. It is arranged in the way that Instagram users should comment or tag their names or their friends and family members under the vicarious visit post in order that shrine servants visit the shrine on behalf of them or the mentioned people.

By framing certain types of gestures, a series of shrine images posted by the shrine accounts appear to establish particular types of emotional states and gestures and prescribe certain tropes of mobile photography in the shrine. A notable motif portrays visitors, usually from behind, standing in front of the golden dome and arches in a humble manner (Figure 4). With their gaze fixed upwards to the shrine, the motif stresses humbleness of the visitor in the presence of the Imam and reinforces the symbolic, medial role of the dome in making a spiritual connection with the Imam. Many video clips with vocals emphasize the position of submissiveness and the feeling of guiltiness, by encouraging visitors to beg the Imam for help and forgiveness. Another recurring motif consists of the gesture of sitting alone on the ground or leaning against a wall in solitude, again in front of the golden dome. This motif has a similar effect to the previous one, and in addition, underscores the private, emotional relationship that the visitor can form with the Imam.

Figure 4.

The gestures of ziyarat in the holy shrine framed by @imam_reza Instagram account: (a) A gesture of respect and submission in the presence of the Imam Reza’s golden dome; (b) A woman leaning against the wall in the holy shrine; (c) A man sitting on the ground in a holy court.

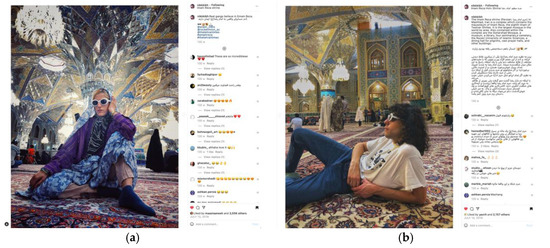

3.5. Youths’ Alternative Images: Being Cool in the Holy Shrine

Visitors with liberal attitudes on Islam, differing from the IRI’s official Islam, construct alternative holy shrine spaces through their online images. A notable example appears on the Instagram profile of a young Iranian artist, based in Europe, named Niknaz Khalouzadeh. According to her postings, her lifestyle easily breaches the IRI’s cultural framework. In a video of hers, for instance, she dances with a group of her female friends in the streets of the “holy” city of Mashhad without wearing the “Islamic” hijab. Three of her postings depict her and her companions in Imam Reza Shrine posing with spectacular decorative elements in their background. In these images they take up carefree and playful positions, the females combining the old-fashioned flower-patterned chador with a pair of stylish white sunglasses (Figure 5a). By applying an Instagram filter to one of her photos, she has made an image of herself shaking her neck, which stresses the joyful gist of her gesture. In her caption she has explained her way of attachment to the place:

Figure 5.

Posing in the holy shrine of Imam Reza (Used with permission): (a) source: https://www.instagram.com/p/Bz2cbbDoEHq/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link (accessed on 17 May 2021) (b) source: https://www.instagram.com/p/Bz5YO3hI5JZ/ (accessed on 17 May 2021).

In my opinion, Imam Reza Shrine is one of the most beautiful places to visit in Iran, [where] one gets amazed by the visitors’ broad age range and variety of nationalities, all of whom share the same faith in the place. The shrine is extremely clean, servants are very well behaved, and it is highly safe. […] It boasts astonishing mirror ornamentations, extraordinary tiles, and a very adorable pure atmosphere. Instead of coffeeshops, from now on, I’d like to go to the shrine to chill.

In this way, Niknaz Khalouzadeh has reconstructed the shrine’s space for the sake of a casual, non-sacred function, which is hanging out, relaxing, and taking aesthetic, cool and funny photographs (Danesi 1994). Her images have employed the visual character of the architectural ornamentation, which is basically associated with the holy shrine, for the purpose of fashion experiments and artistic inspiration. With her creative employment of the chador, which is a mandatory item of clothing for female visitors, she has generated a loose space of performance allowing her to deviate from the conventional gestures of ziyarat without conspicuously transgressing sensitive limits. As she mentions in the caption, by acting like foreign visitors she and her friends enjoy a freedom usually granted to international pilgrims and tourists in holy shrines (Figure 5b).

Another example of being cool in the holy shrine comes from an online boutique’s Instagram profile.38 As an online shop based in a small city near Tehran, Walton Boutique offers sports outfits and articles of clothing. By modeling in a variety of sumptuous settings the boutique owner presents his merchandise: leaning against a Mercedes Benz in Turkey, posing on a hill overlooking the city of Tehran, and in luxurious mansions. A recent geo-tagged post portrays him posing in the holy shrine in front of a golden arched entry.39 At one level, the image presents a picture of a fashionable visitor which is in line with the gist of the traditional visiting manner encouraging visitors to wear their best available clothes. At another level, however, the practice of modeling in the Shrine contrasts the tradition of pilgrimage by transforming the holy place to a stage for clothing advertisement. Considering these two dimensions together demonstrates again the creative employment of potentialities in the sacred space for its desacralization. What is underlined by this image is the conveyance of the luxurious ornate elements of the holy place to asecular, aesthetic setting through Instagramming the shrine.

4. Discussion

As a significant terrain in the global online space, Instagram is framed in official Iranian discourse as a frontier in the media war between Western actors, equipped with weaponries of misinformation and skepticism, and the Iranian nation, in particular its youths. On this basis, revolutionary clerics, Islamic cultural institutions, and elite youths have been called upon online jihad to counter the enemy by providing proper online contents. On the domestic level, however, Instagram has provided a contested space where offline and online tensions between religious classes, particularly clerics, and politically, economically, or socially discontented groups of society manifest itself.

Clerics have exploited the virtual platform of Instagram as an opportune means of communication to extend their influence over young users, improve their social image, and respond to serious critics questioning their social benefit. In this way, they have framed themselves as pioneers of helping people and as leaders of revolutionary youth campaigns in disaster-stricken and deprived areas. By colliding with dissident online actors and cinema celebrities, as established cultural authorities among young populations, they have attempted to portray themselves as legitimate replacement for the social status of celebrities. The online presence of clerics relies heavily on their offline activities, on one hand, and the division they demarcated with secular online influencers, on the other hand. The image-spaces they have constructed on Instagram extends their top-down and exclusionary types of public associations as they do not enter into conversation with non-religious groups of society and insist on male-dominated and sex-segregated spaces. Moreover, through the utilization of the offline infrastructure they have in control, such as holy shrines, clerics produce images which invoke religious emotions fostering sentimentality and submissiveness.

The findings demonstrated that the practice of networked, mobile image-making has become an integrated part of Iranian Shia culture and has shaped the ritual and the spatiality of sacred places. The presence of holy shrines on Instagram has enhanced the popularization of Islamic culture owing to two major reasons. Firstly, to appear as spectacular and beautified places to be they emphasize the visual attractiveness and material opulence, which consequently translates the sacred to the luxurious. Secondly, people with secular affiliations with religious traditions, and even those with non-religious incentives, contribute to the social media imagery of holy places. As a result, the use of Instagram has expanded the realm of youth religiosity through the performance of alternative identities and production of cool images on holy sites without provoking any conflict in traditional religious communities. This has also led to the decontextualization of holy shrines, as elements of ornamentation are utilized in secular settings on social media.

Funding

This paper was supported by the PhD scholarship from the German Academic Scholarship Foundation (Studienstiftung des deutchen Volkes).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | https://www.instagram.com/khamenei_ir/ (accessed on 28 January 2022). Ayattollah Khamenei’s network of Instagram accounts is extended by several associate profiles echoing his opinions and statements on a variety of themes such as the Palestinian cause, news analysis, and Islamic lifestyle. While the profiles under his name seem to be officially administerated, none are granted Instagram’s Verified Badge. It is not evident if the account administerators have not requested verification or Instagram has declined their request. The leader’s semi-unofficial presence, however, suggests an ambivalent stance on Western social media: utilizing the popular online platforms as a fashionable means of propagation while not confirming their legitimacy as adversarial Western corporations. |

| 2 | https://farsi.khamenei.ir/speech-content?id=47637 (accessed on 9 January 2022). |

| 3 | https://farsi.khamenei.ir/speech-content?id=47510 (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 4 | Fars News. https://www.farsnews.ir/news/14000112000548/انتشار-برای-نخستین-بار%7C-رهبر-انقلاب-دستگاه-تولید-محتوا-را-تقویت-کنید (accessed on 10 May 2021). |

| 5 | https://www.instagram.com/www_aqr_ir/?hl=en (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 6 | https://www.instagram.com/astanqom/?hl=en (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 7 | https://farsi.khamenei.ir/speech-content?id=40833 (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 8 | https://farsi.khamenei.ir/newspart-index?tid=2558 (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 9 | |

| 10 | https://english.khamenei.ir/news/6415/The-Second-Phase-of-the-Revolution-Statement-addressed-to-the (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 11 | https://hawzah.net/fa/Article/View/96960/وظیفه-و-نقش-روحانیت-در-فضای-مجازی-از-دیدگاه-رهبر-معظم-انقلاب (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 12 | Fars News. https://www.farsnews.ir/news/14001028000253/فعالان-فضای-مجازی-موفقیت%E2%80%8Cها-و-پیشرفت%E2%80%8Cهای-انقلاب-را-برای-افکار-عمومی (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 13 | Jahan News. “Aghamiri is sentenced to remove his clerical uniform.” https://www.jahannews.com/news/665216/جزئیات-حکم-خلع-لباس-سیدحسن-آقامیری-عکس (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 14 | https://www.instagram.com/hasanaghamirii/ (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 15 | https://old.iranintl.com/ايران/حمله-در-معابر-عمومی-و-کشته-شدن-چهار-روحانی-در-دو-سال-گذشته (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 16 | https://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1396/08/02/1555363/جزئیات-قتل-یک-روحانی-در-تهران-مقتول-دانشجوی-دکترای-الهیات-بود (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 17 | Za’eri wrote further in the caption “The ones who come and go with [their own] drivers and bodyguards are never accountable! The young driver stressed three times that he does not give ride to clerics!” https://www.instagram.com/p/CYZUWlhto_z/ (accessed on 17 April 2021). |

| 18 | Fars News. A fresh look at the Revolution Leader’s warning about mix-gender trips in universities after 13 years. 8 August 2015. Accessed 17 January 2022. https://www.farsnews.ir/news/13940504000427/بازخوانی-هشدار-۱۳-سال-پیش-رهبر-انقلاب-درباره-اردوهای-مختلط-در-دانشگاه |

| 19 | ISNA. https://www.isna.ir/news/95050114902/5-جمله-آیت-الله-علم-الهدی-و-5-نکته (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 20 | BBC. https://www.bbc.com/persian/arts/2016/08/160816_nm_mashhad_concer_janati (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 21 | http://www.ensafnews.com/302744/رئیس-سازمان-اوقاف-افراد-با-زاویه-سیاسی/ (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 22 | https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2017/1/19/why-thousands-of-iranians-are-fighting-in-syria (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 23 | The original post was removed by Mousavi on his Instagram profile https://www.instagram.com/chanelkomeil/ (accessed on 28 January 2022). However, the video is still available on several other profiles and news website, for instance: https://www.khabaronline.ir/news/1249346/فیلم-آقای-پرستویی-اول-بیل-بزن-بعد-حرف-بزن (accessed on 15 January 2022). |

| 24 | The hashtag of “first shovel, then complain” has 4012 posts on Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/explore/tags/اول_بیل_بزن_بعدا_حرف_بزن/ (accessed on 15 January 2022). |

| 25 | https://www.instagram.com/p/BwIDQ2ulxSv/ (accessed on 10 January 2022). |

| 26 | It is said that Shia Imams helped the poor in dark times of the night for the sake of not being recognized. On this basis, hiding righteous deeds is considered as a moral value in Shia Islam. Showing them on the contrary is deemed as hypocrisy. |

| 27 | https://www.instagram.com/p/BwJiy27HX_D/ (accessed on 28 January 2022). In another instagrammed video a cleric responds to the accusation of hypocrisy by claiming that turban is part of clothes of clerical living, not a work uniform. Clerics have turban while working, he argues, because they always wear it. He adds the images of clerics provide evidence for the future when people ask where clerics in times of public hardship. https://www.instagram.com/p/BwTvlXUFHtR/ (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 28 | https://defapress.ir/fa/news/108536/سلفی-یک-شهید-با-شهدای-گمنام-عکس (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 29 | https://iqna.ir/fa/news/3700020/مسابقه-عکس-سلفی-با-مادران-شهدا-برگزار-می%E2%80%8Cشود (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 30 | https://tehran.farhang.gov.ir/ershad_content/media/image/2019/11/917577_orig.mpg (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 31 | https://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1398/12/06/2210585/عکس-یادگاری-با-حاج-قاسم-در-گلزار-شهدای-کرمان-به-روایت-تصویر (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 32 | Shahab Moradi. 19 November 2017. https://www.instagram.com/p/BbsTwH4Do5y/ (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 33 | Sa’el-e Kharabat. No Photos! 4 June 2013. Accessed on 17 January 2022. http://abdolghadir.blogfa.com/post/61 |

| 34 | See note 5 above. |

| 35 | https://www.instagram.com/explore/locations/227081143/imam-reza-shrine/ (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 36 | https://www.instagram.com/imamreza_ir/ (accessed on 10 January 2022). |

| 37 | https://www.instagram.com/p/CYY02ZKITvL/ (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 38 | https://www.instagram.com/wallton__boutique/ (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

| 39 | https://www.instagram.com/p/CY1eLhKNsmk/ (accessed on 28 January 2022). |

References

- Awan, Imran. 2014. Islamophobia and Twitter: A typology of online hate against Muslims on social media. Policy & Internet 6: 133–50. [Google Scholar]

- Badinfekr, Mohammad Javad, Hossein Sarafraz, and Morteza Samiei. 2021. The function of celebrity in transition from ideological to cultural semiotics (Farsi). Quarterly of New Media Studies 24: 37–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bahfen, Nasya. 2018. The individual and the ummah: The use of social media by Muslim minority communities in Australia and the United States. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 38: 119–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Heidi A. 2012. Understanding the relationship between religion online and offline in a networked society. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 80: 64–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Heidi A., and Giulia Evolvi. 2020. Contextualizing current digital religion research on emerging technologies. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies 2: 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campbell, Heidi A., and Mia Lövheim. 2011. Introduction: Rethinking the online–offline connection in the study of religion online. Information, Communication & Society 14: 1083–96. [Google Scholar]

- Couldry, Nick, and Andreas Hepp. 2013. Conceptualizing Mediatization: Contexts, Traditions, Arguments. Communication Theory 23: 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danesi, Marcel. 1994. Cool: The Signs and Meanings of Adolescence. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, Lorne L., and Douglas E. Cowan. 2004. Introduction. In Religion Online: Finding Faith on the Internet. Edited by Dawson L. Lorne and Douglas E. Cowan. London: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Echchaibi, Nabil. 2011. Voicing Diasporas: Ethnic Radio in Paris and Berlin between Cultural Renewal and Retention. Lunenburg: Lexicon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Echchaibi, Nabil. 2013. Muslimah Media Watch: Media activism and Muslim choreographies of social change. Journalism 14: 852–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfenbein, Caleb, Farah Bakaari, and Julia Schafer. 2021. Mapping Anti-Muslim Hostility and its Effects. In Digital Humanities and Research Methods in Religious Studies. Edited by Christopher D. Cantwell and Kristian Petersen. Berlin: De Gruyter, vol. 2, pp. 249–70. [Google Scholar]

- Eshaghi, Peyman. 2015. To Capture a Cherished Past: Pilgrimage Photography at Imam Riza’s Shrine, Iran. Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication 8: 282–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evolvi, Giulia. 2017. Hybrid Muslim identities in digital space: The Italian blog Yalla. Social Compass 64: 220–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Evolvi, Giulia. 2019. # Islamexit: Inter-group antagonism on Twitter. Information, Communication & Society 22: 386–401. [Google Scholar]

- Evolvi, Giulia, and Maria Chiara Giorda. 2021. Introduction: Islam, Space, and the Internet. Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture 10: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Far, Nemati, Sayyid Nosrat Allah, Safoorai Parizi, and Mohammad Mehdi. 2019. Investigating the effect of social networks on hijab with an emphasis on the religiousity dimensions (Farsi). Religion and Communication 26: 335–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, Jauhara, Elaine Howard Ecklund, and Connor Rothschild. 2021. Navigating Religion Online: Jewish and Muslim Responses to Social Media. Religions 12: 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridi, Luciano. 2015. The Onlife Manifesto: Being Human in a Hyperconnected Era. Berlin: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, Jonathon K., and Norman E. Youngblood. 2014. Online religion and religion online: Reform Judaism and web-based communication. Journal of Media and Religion 13: 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazvini, Mahrou Zia. 2019. Remediated Pilgrimage to the Shrine of Imam Reza. Ph.D. dissertation, Lancaster University, Lancaster. [Google Scholar]

- Helland, Christopher. 2000. Online-religion/religion-online and virtual communitas. In Religion on the Internet: Research Prospects and Promises. Edited by Jeffrey K. Hadden and Douglas E. Cowan. London: JAIPress/Elsevier Sience, pp. 205–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hjarvard, Stig. 2008. The mediatization of religion: A theory of the media as agents of religious change. Northern Lights: Film & Media Studies Yearbook 6: 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hjarvard, Stig. 2016. Mediatization and the changing authority of religion. Media, Culture & Society 38: 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Honarpisheh, Donna. 2013. Women in pilgrimage: Senses, places, embodiment, and agency. Experiencing Ziyarat in Shiraz. Journal of Shi’a Islamic Studies 6: 383–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, Seyyed Mohammad, Mahdi Molaei Arani, and Gholipur Bahramabadi Zahra. 2019. A typology of the representation of clerics’ selves on Instagram: Capacities and challanges (Farsi). Reliogion and Cultural Politics 13: 127–59. [Google Scholar]

- Krotz, Friedrich, and Andreas Hepp. 2011. A concretization of mediatization: How ‘mediatization works’ and why mediatized worlds are a helpful concept for empirical mediatization research. Empedocles: European Journal for the Philosophy of Communication 3: 137–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, Bruno. 2007. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lebni, Javad Yoosefi, Arash Ziapour, Nafiul Mehedi, and Seyed Fahim Irandoost. 2021. The Role of Clerics in Confronting the COVID-19 Crisis in Iran. Journal of Religion and Health 60: 2387–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lövheim, Mia, and Gordon Lynch. 2011. The mediatisation of religion debate: An introduction. Culture and Religion 12: 111–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, Setha. 2016. Spatializing Culture: The Ethnography of Space and Place. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mishol-Shauli, Nakhi, and Oren Golan. 2019. Mediatizing the Holy Community—Ultra-Orthodoxy Negotiation and Presentation on Public Social-Media. Religions 10: 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mollabashi, Yavar Alipour, Shahnaz Hashemi, and Ali Jafari. 2020. The role of Instagram in the reproduction of religious culture amongst Iranian youths. Islam and Social Studies 30: 157–90. [Google Scholar]

- Movahed, Majid, Zeinab Niknejat, Zahra Moaven, and Maryam Hashempour Sadeghian. 2020. Representation of Arbean’s Walk in Cyberspace: Sociological semiotic analysis of Arbean’s Walk’s images on Instagram. Bi-Quarterly Scientific Journal of Religion & Communication 27: 411–45. (In Farsi). [Google Scholar]

- Nas, Alparslan. 2021. “Women in Mosques”: Mapping the gendered religious space through online activism. Feminist Media Studies, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarali, Hossein. 2016. Digital Photography Does Not Have Ritual Character. Tasnim News Agency. July 6. Available online: https://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1395/04/16/1121960/عکس-دیجیتال-حال-و-هوای-آیینی-ندارد-خاطرات-عکس-با-حرم-در-نسیان-تکنوکراسی (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Nisa, Eva F. 2018. Creative and lucrative Da‘wa: The visual culture of Instagram amongst female Muslim youth in Indonesia. Asiascape: Digital Asia 5: 68–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Osgerby, Bill. 2020. Youth Culture and the Media: Global Perspectives. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, Kristin M. 2016. Beyond fashion tips and hijab tutorials: The aesthetic style of Islamic lifestyle videos. Film Criticism 40: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, Kristin M. 2020. The Unruly, Loud, and Intersectional Muslim Woman: Interrupting the Aesthetic Styles of Islamic Fashion Images on Instagram. International Journal of Communication 14: 1194–213. [Google Scholar]

- Putri, Addin Kurnia, and Yuyun Sunesti. 2021. Sharia Branding in Housing Context: A Study of Halal Lifestyle Representation. JSW (Jurnal Sosiologi Walisongo) 5: 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Taufiqur, Nurnisya Frizki Yulianti, Nurjanah Adhianty, and Hifziati Lailia. 2021. Hijrah and the articulation of islamic identity of indonesian millenials on instagram. Jurnal Komunikasi: Malaysian Journal of Communication 37: 154–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Gillian. 2016. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Rota, Andrea, and Oliver Krüger. 2019. The Dynamics of Religion, Media, and Community: An Introduction. Online-Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet 14: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Saei, Mansur, Hossein Basirian-e Jahromi, and Ehsan Zahiroddini. 2020. The relationship between Instagram activities and adherence to religious identity. Satellite TVs and New Media Studies 22: 65–92. [Google Scholar]

- Shaker, Muhammad Kazem. 2005. Spirituality and Prayer in Shiite Islam. Swindon: AHRC. [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi, Rahnemu Saeid, Majid Sharifi Rahnemu, and Javad Hedayati Manzour. 2018. Relationship between Instagram usage and religious identity amongst youths in the range of 15–18 years old in the city of Hamedan. Quarterly of Deisciplinary Knowledge 5: 29–58. [Google Scholar]

- Solahudin, Dindin, and Moch Fakhruroji. 2020. Internet and Islamic Learning Practices in Indonesia: Social Media, Religious Populism, and Religious Authority. Religions 11: 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stadler, Nurit. 2020. Voices of the Ritual: Devotion to Female Saints and Shrines in the Holy Land. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Subrahmanyam, Kaveri, and David Šmahel. 2011. Digital Youth: The role of Media in Development. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Utekhin, Ilya. 2017. Small data first: Pictures from Instagram as an ethnographic source. Russian Journal of Communication 9: 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valibeigi, Narges. 2018. Being Religious through Social Networks: Representation of Religious Identity of Shia Iranians on Instagram. In Mediatized Religion in Asia. London: Routledge, pp. 163–89. ISBN 9781315170275. [Google Scholar]

- Van Zoonen, Liesbet, Farida Vis, and Sabina Mihelj. 2011. YouTube interactions between agonism, antagonism and dialogue: Video responses to the anti-Islam film Fitna. New Media & Society 13: 1283–300. [Google Scholar]

- Vasigh, Behzad. 2020. Expression of Applying the Spiritual Sense of Place Instead of the Concept of Sense of Place (Case Study: Shrine of Imam Riḍā (as)). Journal of Razavi Culture 30: 223–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, Kayla Renée. 2014. Remixing images of Islam. The creation of new Muslim women subjectivities on YouTube. Online-Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet 6: 144–63. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Glenn. 2004. Reading and praying online: The continuity of religion online and online religion in Internet Christianity. In Religion Online: Finding Faith on the Internet. Edited by Lorne L. Dawson and Douglas E. Cowan. London: Routledge, pp. 93–106. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).