Abstract

In every society, refugees face social and economic exclusion. In particular, social distance towards refugees may be seen remarkably in cities where host people and refugees live together intensely. This study examined essential predictors of social distance towards refugees: religiosity, socioeconomic status (SES), satisfaction with life, and threat perception towards refugees. A quantitative research strategy was used to collect cross-sectional data from 1453 individuals via an online questionnaire in Turkey. Confirmatory factor, correlation, regression, and mediation analyses were conducted. In this study, the effect of religiosity and socioeconomic status on social distance towards refugees and the serial mediation effects of satisfaction with life and threat perception towards refugees on this relationship were analyzed. Questions related to age, gender, marital status, education level, and having refugee neighbors or not were used as control variables. It was found that religiosity and SES were associated with social distance towards refugees. Furthermore, in the effect of religiosity and SES on social distance towards refugees, the serial mediating roles of satisfaction with life and threat perception towards refugees, respectively, were identified.

1. Introduction

The global number of refugees and asylum seekers is growing. The number of Syrians is around 3.6 million in Turkey, 944,000 in Lebanon, 676,000 in Jordan, 532,000 in Germany, 253,000 in Iraq, 133,000 in Egypt, 109,000 in Sweden, 94,000 in Sudan, 49,000 in Austria, and 32,000 in the Netherlands. As it has been observed, 83% of Syrians escaping the crisis are in Turkey and neighboring nations (Todd 2019). The current refugee numbers put the economic and social opportunities of the countries in the region and Europe into trouble. The peoples of the host countries regard refugees as a threat to their security and a burden on their economies (Koc and Anderson 2018). The host community’s social distance, which is a subject’s lack of availability and relational openness to individuals viewed as outside their social category (Bichi 2008), towards refugees may lead to refugees’ isolation. It was observed that the social distance towards refugees differed according to societies with different characters and experiences. The host society’s perspective is influenced by its previous problems with refugees, their crime rates, their contributions to the host country, and their social, cultural, political, and economic burdens. In addition, the religiosity and socioeconomic status of the host country’s people also affect attitudes and social distance towards refugees. In this study, the effect of Turkish people’s religiosity and socioeconomic status on the social distance they put towards refugees was examined. The serial moderation effects of satisfaction with life and threat perception towards refugees were tested in this effect. Marital status, education level, gender, age, and whether participants have refugee neighbors were used as control variables.

This study is based on the theory developed by Ellison et al. (1989) which explains that religiosity positively affects satisfaction with life. Ellison later updated this theory, with religiosity and socioeconomic status (education level and income) having an impact on satisfaction with life (Ellison 1991). In a study conducted by Headey et al. (2010) which was based on this theory, a significant positive relationship was found between long-term changes in religious practices and changes in life satisfaction with data from the German Socioeconomic Panel Questionnaire. Likewise, positive associations were determined between religiosity and satisfaction with life in other studies (Chumbler 1996; Ngamaba and Soni 2017; Rakrachakarn et al. 2015; Yoo 2017). This study started with a research question: How is the relationship realized between religiosity, SES, and social distance towards refugees?

The most remarkable finding of this study was that religiosity and SES had a significant negative effect on social distance towards refugees only through satisfaction with life and threat perception towards refugees. In other words, it is possible to reduce the social distance towards Syrians by reducing threat perception. Religiosity had a positive effect on satisfaction with life and a negative effect on the threat perception towards refugees. Socioeconomic status (SES) had a positive and significant effect on satisfaction with life and a negative and significant effect on the threat perception towards refugees. It was understood that host people’s satisfaction with life and threat perception towards refugees had a serial mediating effect on this relationship. Additionally, satisfaction with life had a negative, but not significant, effect on social distance towards refugees, whereas threat perception towards refugees had a significant positive effect. Therefore, increasing satisfaction with life reduces threat perception towards refugees, and decreasing threat perception diminishes social distance towards refugees. Satisfaction with life was high in women, the elderly, and married people. Furthermore, it was found that males had a high threat perception towards refugees. Social distance towards refugees was revealed to be more common among non-neighbors, low-educated people, and married people.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Research Theory

This study was built on the concept presented by Ellison which states that religiosity has a beneficial effect on life satisfaction (Ellison et al. 1989). Ellison’s research investigated the link between satisfaction with life and three types of religiosity: participative, affiliative, and devotion (praying frequency and closeness to God). It was found that religiosity’s individual and social dimensions, close religious affiliation, participation, and devotion have positive relationships with satisfaction with life (Ellison et al. 1989). However, Ellison later modified this idea on the basis that, in addition to religiosity, trauma and age also have an impact on life satisfaction (Ellison 1991). In Chumbler’s model, in addition to demographic questions such as family income, education, and marital status used by Ellison, social involvement and social class factors explaining the individual’s socioeconomic status were added (Chumbler 1996). Therefore, in all three models, the association of the individual’s religiosity and socioeconomic status with satisfaction with life was emphasized.

It is a matter of debate how religiosity and spirituality affect people’s life satisfaction, attitudes, and health with their different dimensions. Religiosity increases life satisfaction by reducing risky behaviors, increasing social support, diversifying coping mechanisms, strengthening physical and mental endurance, increasing the hope of individuals for the future, and reducing the risk of getting sick (Benda et al. 2006; Cetin 2019; Green and Elliott 2010; Idler et al. 2003; Koçak 2021; Meer and Mir 2014; Páez et al. 2018). Those who attend places of worship regularly, such as mosques, synagogues, and churches, are more likely to marry, form friendship networks, and participate in social activities than those who do not (Hummer et al. 1999). Thus, a religious lifestyle may promote personal quality of life by strengthening community engagement (Ellison et al. 1989). Furthermore, sponsorship activities of religious organizations that carry out volunteering activities foster social interaction, communication, and friendship by encouraging people to gather. Many studies have revealed that social links enhance marriage, improve family relationships, and provide a deep meaning to life (Ives et al. 2010; Muruthi et al. 2020; Rababa et al. 2021; Ten Kate et al. 2017; Yıldırım et al. 2021). According to Berger (1967), religion is strongly associated with human beings and life.

It can thus be said that religion has played a strategic part in the human enterprise of world-building. Religion implies the farthest reach of man’s self-externalization, of his infusion of reality with his own meanings. Religion implies that human order is projected into the totality of being. Put differently, religion is the audacious attempt to conceive of the entire universe as being humanly significant.

Religious beliefs create “symbolic universes” (Berger 1967) by giving their own meaning to life and death. People’s fears have subsided in those universes, and expectations for the future have increased for both the current life and the hereafter. Thus, those with a strong religious belief are happier and more satisfied with their lives (Ellison 1991). A study comparing the satisfaction with life levels of those who prefer religious life and secular life determined that those who prefer religious life have high satisfaction with life. In contrast, those who prefer secular life have very low satisfaction with life (Chumbler 1996). In addition, an eight-year examination using National Health Interview Survey data discovered that consistent attendance at worship services was correlated with an extra eight years of life expectancy compared to never attending (Hummer et al. 1999).

2.2. Religiosity, Socioeconomic Status, and Social Distance towards Refugees

Religion can be thought of as a mediator that unites refugee and native groups into a single identity, replacing their ethnic distinctions with a faith-based one. However, it is sometimes viewed as a challenge to the secular national identity and tends to produce social distance (Şafak-Ayvazoğlu et al. 2021). Religion, race, nationality, xenophobia, gender, education level, the frequency of interaction, and socioeconomic status are the predictors of social distance towards refugees (Anderson 2018; Genkova and Grimmelsmann 2020; Triandis and Triandis 2012). Various predictors of behaviors towards refugees come to the fore, and these can be based on the country, society, the problems they experience with refugees, economic indicators, and religious understandings (Koc and Anderson 2018). According to the literature, there are both positive and negative correlations between religion and views towards migrants. In some studies, ethnic differences and negative attitudes towards refugees are emphasized through the positive relationship between right-wing conservatism and religiosity (Laythe et al. 2002; Rowatt et al. 2009; Rowatt and Franklin 2004). A study found that the inclusion of authoritarian approaches (fundamentalism) to religion may make attitudes towards refugees more restrictive and exclusive (Perry et al. 2015). It was revealed that negative attitudes are more obvious towards those groups who had different orientations in their life later on. Strong religiosity was positively linked with sexual orientation prejudice, but open religiosity was negatively linked with this in the study of Leak and Finken (2011). Carlson et al. (2019) found that openness and agreeableness were negatively correlated with prejudices towards refugees, while religious commitment was positively correlated. A study found that those who have religious affiliations have more negative behaviors than those who do not. This effect is higher for refugees when negative attitudes towards refugees and immigrants are compared (Deslandes and Anderson 2019). In a study undertaken to assess prejudices and attitudes towards refugees among Christians and Muslims in Malaysia, a multi-religious country, variations in explicit and implicit attitudes towards refugees were revealed. In particular, it was observed that prejudice and negative attitudes increased towards different religions (Cowling and Anderson 2019). However, religiosity generally has a positive effect on human behavior and makes individuals more prosocial. In this sense, religion contributes to greater socialization and welfare increase as it connects individuals to a certain social system where people come together and contribute to each other (Cetin 2019; Páez et al. 2018). According to the findings of a study conducted by Pichon et al. (2007), religious beliefs can spontaneously activate prosocial behavioral patterns. Blogowska et al. (2013) discovered that moderate religious people are more tolerant to out-groups than fundamentalist religious people. Furthermore, theology students show a more positive attitude than students in other faculties. However, there was no gender difference in attitudes towards refugees (Yelpaze and Güler 2018). Based on the literature, the following hypothesis was established.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Religiosity has a negative effect on social distance towards refugees.

The socioeconomic status of host individuals also has an effect on attitudes towards refugees. The host community may see refugees as a cultural, economic, and political threat to them (Heath and Richards 2016; Markaki and Longhi 2012). In particular, it was understood that there is more anti-refugee opposition in countries where the macroeconomic situation is not good, unemployment is high, numbers of refugees from different ethnicities are high, and they are mentioned with terrorist incidents (Abdelaaty and Steele 2020). In a country where people have a weak socioeconomic status, negative attitudes and social distance towards refugees who are active in labor markets may increase (Halperin et al. 2007). However, it was found that attitudes towards refugees are more positive in societies with good social and economic opportunities. In a study comparing people’s attitudes towards asylum seekers in Denmark and Israel, it was found that Danes have more inclusive and more moderate approaches to granting rights than Israeli society (Hercowitz-Amir et al. 2017). In a study conducted in European countries to learn about local people’s thoughts towards immigrants, it was understood that positive behaviors towards immigrants increased as education and socioeconomic status increased (Heath and Richards 2016). Many studies show that the income status of the host population, their status in the labor market, and education levels have an effect on their attitudes towards refugees (Abdelaaty and Steele 2020; Bansak et al. 2016; Hainmueller and Hopkins 2014; Heizmann and Huth 2021; Kuntz et al. 2017). It was understood that as the social and economic opportunities of the host people increase, they reduce their negative attitudes towards refugees and the social distance they put between them (Heizmann and Huth 2021; Markaki and Longhi 2012). Based on the literature, the following hypothesis was established.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

SES has a negative effect on social distance towards refugees.

2.3. Satisfaction with Life and Threat Perception towards Refugees as Mediators

Satisfaction with life reflects the difference between individual expectations and the current state of the individual. The more significant the difference between personal expectations and the current state, the lower the life satisfaction (Karataş and Tagay 2021). Religion may bridge the gap between what people want and where they are now. Religious people are happier because they feel connected to their principles and believe that overcoming adversity will reward them. Religious individuals do not complain about their troubles, and they are generally happy with their lives (Ellison et al. 1989; Lim and Putnam 2010). According to the findings of studies on religiosity and life satisfaction, those who have a stronger religious belief and commitment report fewer negative emotions and higher levels of life satisfaction (Roberto et al. 2020; Yonker et al. 2012). According to a study conducted in Turkey, religion mitigates the detrimental impact of income disparity on life satisfaction and positively impacts life satisfaction (Yeniaras and Tugra 2016). In addition to a similar positive link, it was not simply religiosity but the social context provided by religion that strengthened this positive relationship (Okulicz-Kozaryn 2010). According to Páez et al. (2018), religion was linked to low income and social level, as well as being older and female. Without any other factor, these characteristics were found to be negatively related to life satisfaction. However, when religiosity was a moderator, it was found that the negative effect decreases. Attendance at communal religious rites, on the other hand, was correlated with life satisfaction, whereas private religiosity was not. These findings support the notion that the social part of religion enhances well-being and happiness (Páez et al. 2018). Previous results revealed that religiosity has a positive association with life satisfaction (Bergan and McConatha 2001; Joshanloo and Weijers 2016). While religiosity increases life satisfaction, life satisfaction decreases individuals’ tendency to exclude others or perceive them as threats. Thus, attaining spiritual satisfaction increases the sharing of existing economic and social belongings and naturally decreases their tendency to exclude others because they get what they hope from life. Even though refugees are seen as a threat in terms of political, economic, and cultural burdens and living space (Wyszynski et al. 2020), the increase in the life satisfaction of the host society reduces the perception of threat towards refugees (Meidert and Rapp 2019). The host society’s perception of threat towards refugees can sometimes vary depending on their socioeconomic status, culture, and values, and the refugees’ economic situation, education level, ethnicity, and religion, as well as satisfaction with life (Bansak et al. 2016; Vala and Pereira 2020). According to the literature, the following hypothesis was established.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Religiosity has a positive association with SwL.

Turkey accepted the Syrians as guests with the expectation that they would return (Ergin 2016). The fact that the majority of the immigrants belong to the religion of Islam has increased the intimacy between the Turkish people and the Syrians (Şahin 2016). Despite various worries in Turkish society, societal acceptability is high, owing to a shared history, religion, and culture. According to Syrians’ statements, they are happy and safe and encounter no significant discrimination (Erdoğan 2020). Additionally, the current government, a center-right and conservative-democratic party, has consistently maintained a humanitarian and brotherhood-based attitude towards Syrian refugees, viewing them as guests rather than refugees (Lazarev and Sharma 2017). This approach reflects Ansar and Muhajir Islamic discourse from the time of the Prophet Muhammed (Gulmez 2019). Therefore, the current ruling party used Ansar and Muhajir discourse, and in the party manifesto, Syrian refugees were accepted as guests, and the right of temporary protection was given.

In a study conducted in 11 countries worldwide and in 10 countries in Europe, half of the people stated that refugees brought an essential economic burden to their country (Dempster and Hargrave 2017). In countries with high unemployment, this view is even more negative. Since there is a certain amount of unemployment in Turkey, the employment of Syrian refugees in the labor market makes it difficult for unemployed Turkish individuals to find a job (Bidinger 2015). In addition, the fact that Syrians employ their children in the informal sector further increases the problems (Pinedo Caro 2020; Yalçın 2016). Thus, Syrians in Turkey are seen as mainly an economic threat and an opportunity due to cheap labor (Akar and Erdoğdu 2019). Despite these issues, Turkish people do not react to the government because of the Syrians’ problems (Sönmez and Adıgüzel 2017). Even in border cities where there are many Syrians, the votes of the current government have not decreased (Erdoğan 2020). Consequently, thanks to the religious-spiritual approaches by government and volunteer organizations (Danış and Nazlı 2019), and the common religion (Lazarev and Sharma 2017) and history of the two societies for 400 years (Ergin 2016; Shaherhawasli and Güvençer 2021), the Syrians were not viewed as a threat in Turkey as much as in other developed countries. Based on the literature, the following hypothesis was established.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Religiosity has a negative association with threat perception towards refugees.

According to the literature, it was found that the satisfaction with life levels of individuals with a high socioeconomic status increase. In Kendig et al.’s (2016) and Ozdemir’s (2019) studies, it was found that SES status had a positive and significant relationship with satisfaction with life. A high level of education of the parents in a family increases the income levels, and as a result, the children also have a good socioeconomic status. A high socioeconomic status of a host population reduces the negative attitude towards refugees due to economic reasons (Kehrberg 2007; Pak and Elitsoy 2020; Vala and Pereira 2020), as individuals with a good socioeconomic status do not see refugees as rivals for themselves in the labor markets. Additionally, working in labor markets is seen as an integration opportunity for refugees by host societies (Brell et al. 2020; İçduygu and Diker 2017). Furthermore, there is a positive association between socioeconomic status and self-esteem (Raymore et al. 2018; Twenge and Campbell 2016). Moreover, self-esteem can lead to less out-group discrimination and thus reduce the perception of threat towards refugees (Verkuyten and Nekuee 2001). Therefore, the following hypotheses were established.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

SES has a positive effect on SwL.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

SES has a negative effect on threat perception towards refugees.

In many countries, immigrants are often seen as a threat. European societies often argued that the most critical factor behind international anti-immigration in migrant assessment is the economical factor (Fatıma 2019). A study in Europe asked whether immigrants are a threat; more than half of Europeans said they see refugees as a threat (Canatan 2013). The benefit and threat relationships are negative; as the benefit increases, the threat decreases (Topal et al. 2017). The fact that Syrians work in the labor market with meager wages and in the informal sector causes difficulties in the employment of the Turkish workforce. Therefore, the employment of Syrians is seen as an economic threat, especially for those who are unemployed and have a weak financial situation. Topal et al. (2017) found that working for meager wages in labor markets is the most significant economic threat to the host population. In particular, the fear of being unemployed grows with threat perception and reduces the life satisfaction of individuals (Wulfgramm 2011).

Damage perception can contribute to Syrians’ exclusionary sentiments in three areas: economic gain harm, public space damage, and national identity (Saraçoğlu and Bélanger 2019). There are different approaches in studies on this subject. A study found that host people with a group and high life satisfaction increased their exclusionary attitudes towards refugees (Dyduch-Hazar et al. 2019). In addition, social distance towards refugees increased in peoples where local or national identity, which is a higher value than life satisfaction and suppresses it, is prominent (Konukoğlu et al. 2020). In recent years, white supremacist and racist movements in Europe and America have shown exclusionary attitudes towards those who are not like them and have different religions, as they see a threat to their economy, politics, and security (Besley and Peters 2020; Burris et al. 2000). The emergence of the names of members of certain religions through terrorist acts strengthens the perception of threat towards the members of that religion. Therefore, there is a perception of security and political threat, especially towards immigrant groups (Dunwoody and McFarland 2018; Klaus et al. 2018; Lohrmann 2000). Although these approaches see refugees as a security and political threat, economic problems are often seen as a threat. This threat is likely to decrease as life satisfaction increases (Dias Matavelli et al. 2020). From a competitive standpoint, the greater the host population’s socioeconomic level, the less they consider and reject refugees as an economic danger (Abdelaaty and Steele 2020). There is evidence in specific research that the opinion of refugees as a threat may diminish with an increase in the economic safety of the host people (Kehrberg 2007). Those with a low socioeconomic status, on the other hand, have a solid reaction to refugees according to some studies (Coenders et al. 2017; Kunovich 2004). In this sense, there is a possibility that a high socioeconomic status and an increase in life satisfaction will reduce the threat perception towards refugees and then lower social exclusion towards them (Citrin et al. 1997; Marozzi 2016; Padir 2019). Studies in the literature show that life satisfaction reduces the tendency to exclude refugees or other groups or perceive them as a threat (Aker 2019; Cowling et al. 2019; Pak and Elitsoy 2020; Stephan et al. 2005). Thus, the following hypotheses were created.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

SwL has a negative effect on threat perception towards refugees.

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

SwL has a negative effect on social distance towards refugees.

Hypothesis 9 (H9).

Threat perception towards refugees has a positive effect on social distance towards refugees.

Hypothesis 10 (H10).

There is a serial mediation impact in the effect of religiosity on social distance towards refugees via SwL and threat perception towards refugees.

Hypothesis 11 (H11).

There is a serial mediation impact in the effect of socioeconomic status on social distance towards refugees via SwL and threat perception towards refugees.

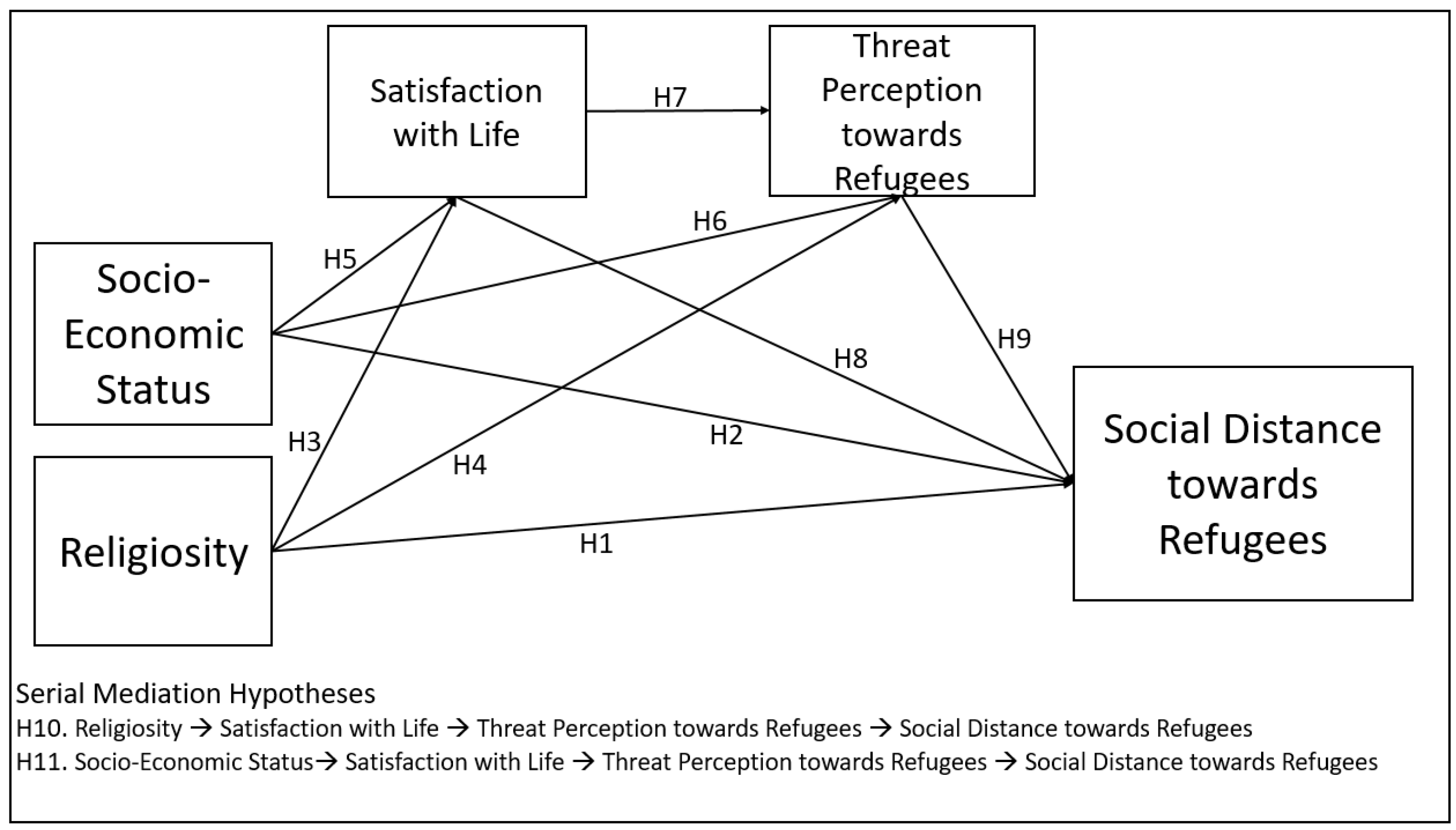

2.4. The Context of This Study

As the internal problems and conflicts of countries increase, the number of applicants for refugee status is increasing. Refugees are generally seen as a burden for the governments of the countries they visit and as an economic, political, security, and cultural threat to their people. For this reason, generally, the host community sees refugees as a threat, meaning they tend to exclude refugees or maintain a social distance towards them. This study investigated how Turkish people’s religiosity, socioeconomic status, and satisfaction with life affect their threat perception and social distance towards Syrian refugees in Turkey. Figure 1 shows the conceptual model of the research. To find an answer to the research question, hypotheses were formed for each relationship.

Figure 1.

Research conceptual model.

In order to test the hypotheses, direct and indirect analyses were conducted between all variables, as shown in Figure 1. Regression analyses were conducted between the independent variables of religiosity and SES, the dependent variable of social distance towards refugees, and mediator variables SwL and threat perception. Since serial mediation analysis was conducted in this study, a direct effect was also conducted between the first and second mediator variables. Finally, the mediation effect of both independent variables on the dependent variable, first via satisfaction with life and then with threat perception towards refugees as serial mediators, was tested. The concept of serial mediation establishes a causal chain connecting the mediators (Hayes 2018) (satisfaction with life, threat perception towards refugees) to a certain cause–effect path flow. In our model, religiosity and socioeconomic status can increase satisfaction with life, decreasing threat perception towards refugees and thus decreasing social distance towards refugees.

3. Method

3.1. Participants

A total of 1453 individuals from different cities of Turkey participated in this study. Since most of the participants were reached through universities as students in the faculty of health sciences, the number of young and female participants was higher. Participants were aged 18 and over. All participants were included in the analysis because they completed all the questions entirely.

The frequencies of the demographic data of the participants were shown in

Table 1. Considering the entire sample, most participants were female (65.5% female, 34.5% male), and the mean age was relatively low (mean = 32.98, SD = 13.495). Since the majority of the participants were young, it was determined that there were many singles (44.3% married, 55.7% single), their educational status was relatively high, and most of them were university graduates (59.4% university, 20.2% high school, 11.2% elementary, 6.5% middle school, and 2.6% master’s or Ph.D. degree). In addition, when the participants were asked whether they had Syrian neighbors, nearly half of them stated that they had Syrian neighbors (46.6% Yes, 53.4% No).

Table 1.

Frequencies of sociodemographic variables.

3.2. Data Collection Instruments

Participants were asked to answer the basic sociodemographic and socioeconomic status questions, and the scales of religiosity, satisfaction with life, threat perception towards refugees, and social distance towards refugees used in the study.

3.2.1. Sociodemographic Questions

During the study, sociodemographic variables such as marital status, gender, age, education level, and whether participants have refugee neighbors were used. Age was asked as an open-ended question, while others were asked as categorical questions. Education level was measured by asking participants to indicate their highest education level, with options ranging from elementary school, the lowest, to master’s or Ph.D., the highest. For the question, “Did you have any refugee neighbor(s) at any point in your life?” participants were asked to answer “Yes” or “No” to the question.

3.2.2. Socioeconomic Status

Participants were asked questions about their family background because their families’ socioeconomic status directly or indirectly contributes positively to the current and future states of family members in Turkey (Cetindamar et al. 2011; Gizir and Aydin 2018; Tabak 2020). The educational status of the mothers and fathers of the participants was asked in the form of five categories, from elementary school, the lowest, to master’s or Ph.D. degree, the highest. In addition, the participants were asked to choose one of the income groups of the family from the lowest to the highest. The participants’ socioeconomic status was determined by computing the average of the education levels of the mother and the father and the categorical income status of the family. Similarly, studies in the literature used the average of parent education level and family income level for socioeconomic status (Aarø et al. 2009; Louis and Zhao 2016; Wickrama et al. 2009).

3.2.3. Religiosity

The religiosity sub-factor with two questions was taken from the Religious Attitude Scale developed by Ok (2011). The religious attitude scale developed for Muslims was evaluated with the results of two separate samples collected from university students. The internal consistency ratios of two different samples were 0.81 and 0.91. Factors were determined by performing both exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis. Assessing Attitude towards Christianity among Adolescents and Intrinsic Religiosity scales were used to develop the scale (Allport and Ross 1967; Francis et al. 2005). In the study, statements such as “I try to fulfill the requirements of the religion I believe in”, and “I pay attention to whether my life is in accordance with religious values” were used. In addition, a five-point Likert scale was used, and the answers were from (1) certainly not agree to (5) certainly agree. In this study, the internal consistency of the religiosity sub-scale was α = 0.88.

3.2.4. Satisfaction with Life

The satisfaction with life scale used in this study was developed by Diener et al. (1985) and later adapted into Turkish by Dağlı and Baysal (2016) after a validity and reliability study. The Cronbach alpha coefficient of the adapted Turkish version was 0.88. The scale consists of 5 items in total. Some of these items are as follows: “I have a life close to my ideals”, “My living conditions are excellent”, and “I am satisfied with my life”. In this single-factor scale, as the score increases, the satisfaction with life level of the individual rises. In this study, 5 items and a 7-point Likert scale between strongly disagree (1) and strongly agree (7) were used. The Cronbach alpha value of the current study was determined as α = 0.858.

3.2.5. Threat Perception towards Refugees

In order to measure the threat perceptions of Turkish people towards Syrians, three items were asked about the economy, security, and politics. For each item, participants were asked to choose one of five levels. To this end, a Likert scale was used, and the answers were from (1) certainly not agree to (5) certainly agree. Items used were as follows: “I think Syrian refugees limit the employment opportunities of Turkish individuals who can work in Turkey”, “I think Syrian refugees increase crime rates and disturb the peace”, and “I think that granting citizenship to Syrian refugees will threaten our democracy”. The internal consistency value of the current study was α = 0.782.

3.2.6. Social Distance towards Refugees

Social distance towards refugees is a sub-scale of negative attitudes towards refugees developed by Sunata et al. (2016). The scale was developed to understand attitudes towards refugees in Turkey. A social distance towards refugees sub-scale consisting of only 4 statements was used for this study. These statements were as follows: “I avoid being friends with a Syrian refugee”, “I do not prefer to sit next to a Syrian refugee when I see a Syrian refugee on the bus”, “The presence of Syrian refugees in the park where I always take my child makes me nervous”, and “I am uncomfortable when my child is friends with Syrian refugee children”. A 5-point Likert scale was used for each question, which was graded from strongly disagree (1) to completely agree (5). As the total score increases, the social distance towards refugees increases. The internal consistency score of the present study was α = 0.907.

3.3. Procedure

Sociodemographic questions and scales were converted into questionnaires and uploaded to the online environment. Participants in the study were reached through Survey Monkey, an online data collection platform (https://tr.surveymonkey.com, 20 May 2021). Participants were selected voluntarily using a snowball sampling method which relies on first sampling responders and then referring others with the desired trait (Johnson 2014). The research was carried out between 5 May and 20 May 2021. With the support of the first participants, their families, school, and co-workers were reached with the snowball method. After the participants were informed about why the research was conducted, which method was applied, the anonymity of the collected information, and what the data would be after the research, their consent was obtained, and they were asked to answer the questions. Anonymity was ensured since no personal identification information was requested from the participants, and IP addresses of the participants were not collected via the online platform. Furthermore, it was ensured that the participants could start the survey at any time, finish it at any time, and stop answering. The survey took an average of 6 min. The research was implemented according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

3.4. Statistical Analyses

This study was designed as quantitative and cross-sectional. After the data were collected via the Survey Monkey online platform, they were first transferred to the MS Excel program for cleaning and editing. Afterwards, IBM SPSS Statistics 25 program and IBM Amos 24 program were used to perform statistical analysis (IBM Corp 2013). First of all, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA, to test the fit of the proposed measurement model) was carried out via the Amos 25 program to ensure the suitability of the factors and construct validity. Next, a new SPSS data file was produced by conducting data imputation through the Amos 25 program. Afterwards, frequency, correlation, regression, and serial mediation analyses were performed using SPSS and PROCESS-Macro Plug-in (Hayes 2018) statistical programs. First, the percentage, mean, and standard deviations of demographic data were determined by frequency analysis. Next, correlation analysis was performed using the Pearson coefficient to determine the relationships between the factors. Multiple regression analysis was used for direct effects between variables and PROCESS-Macro Model 6 mediation analysis for indirect analysis.

4. Results and Hypothesis Tests

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used in this study to assess the appropriateness and construct validity of the components. CFA, a robust statistical approach for investigating latent components’ effects and interactions, directly examines assumptions a priori on connections seen between variables (Jackson et al. 2009). First, a five-factor measuring model was developed using the research scales. CMIN/DF (chi-square/standard deviation), IFI (incremental fit index), CFI (comparative fit index), NFI (normed fit index), GFI (goodness of fit index), and RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation) were used as the goodness of fit values. Then, the cut-off limits of Kline were used as a reference to test the goodness of fit index values of the developed measurement model (Kline 2016).

The CFA values revealed in the first test of the measurement model were within the acceptable cut-off limits (CMIN/DF = 3.182; CFI = 0.915; IFI = 0.923; NFI = 0.912; GFI = 0.920; RMSEA = 0.041). However, it was thought that the goodness of fit results of the first measurement model could be better. To this end, three covariances were created between the high covariances in the residual values found in the modification indices of the measurement model. After modifications, as a result of the final test results, it was determined that the constructed model fit well with the theoretical model and results were within good fit values (CMIN/DF = 2.889; CFI = 0.983; IFI = 0.983; NFI = 0.974; GFI = 0.976; RMSEA = 0.036), as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis values.

4.2. Correlation Analyses

Table 3

shows the correlation analyses between the variables. While the age variable had a positive correlation with satisfaction with life (r = 0.102, p < 0.01) and religiosity (r = 0.187, p < 0.01), it had a negative correlation with education (r = −0.520, p < 0.01) and socioeconomic status (r = −0.292, p < 0.01). There was a positive relationship between education and socioeconomic status (r = 0.344, p < 0.01), and a negative relationship with religiosity and social distance towards refugees (r = −0.249, r = −0.070, p < 0.01, respectively). A negative association was found between religiosity and socioeconomic status, threat perception from refugees, and social distance towards refugees, and a positive relationship was found with satisfaction with life (r = −0.255, r = −0.286, r = −0.159, r = 0.337, p < 0.01, respectively). Conversely, a positive relationship was found between socioeconomic status and satisfaction with life, threat perception towards refugees, and social distance towards refugees (r = 0.154, r = 0.058, r = 0.059, p < 0.01, p < 0.05, p < 0.05, respectively). There was a negative association between satisfaction with life and threat perception towards refugees and social distance towards refugees (r = −0.301, r = −0.231, p < 0.01, respectively), and a strong relationship was observed between threat perception towards refugees and social distance towards refugees (r = 0.825, p < 0.01). Therefore, hypotheses H3 and H4 were accepted.

Table 3.

Correlations analyses.

4.3. Direct Multiple Regression Analyses

Direct regression analyses were conducted between independents and dependents, as shown in

Table 3, with different steps. As shown in

Table 4, control variables were included in the analysis at each step. In Step 1, religiosity and SES had a positive effect on SWL (B = 0.56, B = 0.83, p < 0.001, respectively). In Step 2, it was understood that religiosity, SES, and SWL had a negative effect on TPtR (B = −0.21, B = −0.17, B = −0.17, p < 0.001, p < 0.01, p < 0.001, respectively). In Step 3, negative effects of religiosity on SDtR and positive effects of SES were found (B = −0.22, B = 0.16, p < 0.001, p < 0.05, respectively). In Step 4, in addition to religiosity and SES, SWL and TPtR were included in the model. Considering the negative effect of religiosity on SDtR in the previous step (Step 3), the effect of religiosity on SDtR turned positive with the dominant effect of threat perception towards refugees (TPtR) (B = 0.12, p < 0.001). The effects of SES and threat perception towards refugees (TPtR) on social distance towards refugees (SDtR) were found to be positive (B = 0.14, B = 1.06, p < 0.01, p < 0.001, respectively). When demographic variables were evaluated, it was understood that education increased life satisfaction and decreased TPtR and SDtR, and those with refugee neighbors had less TPtR and SDtR. In light of the direct effects, hypotheses H1 and H2 were rejected, and H5, H6, H7, H8, and H9 were accepted.

Table 4.

Direct effects on SwL, TPtR, and SDtR.

4.4. Indirect Analyses

In order to understand the indirect effects in this study, first of all, the direct effects must be understood. In Table 4, it is shown that religiosity had a significant effect on satisfaction with life. Next, satisfaction with life had a significant negative effect on threat perception towards refugees, and finally, threat perception towards refugees had a positive effect on social distance towards refugees. Consequently, it was observed that a significant relationship continued until social distance towards refugees through religiosity, satisfaction with life, threat perception towards refugees, and Indirect 3, shown in Table 5, occurred significantly (γ = −0.1017, SE = 0.0132, 95% CI [−0.1293, −0.0771]). Indirect 1 was not significant as satisfaction with life had no significant effect on social distance towards refugees (γ = −0.0083, SE = 0.0087, 95% CI [−0.0251, 0.0086]). For Indirect 2, it was found that religiosity decreased threat perception towards refugees, and the reduced threat perception towards refugees decreased social distance towards refugees (γ = −0.2225, SE = 0.0313, 95% CI [−0.2838, −0.1606]). Therefore, the two mediators fully mediate the relationship between religiosity and social distance towards refugees in a serial causal order, as shown in Indirect 3 in Table 5. Therefore, hypothesis H10 was accepted.

Table 5.

Indirect effects of religiosity on SDtR.

Table 4 reveals that socioeconomic status (SES) had a significant impact on satisfaction with life. Furthermore, satisfaction with life had a significant negative effect on threat perception towards refugees, and finally, threat perception towards refugees had a positive impact on social distance towards refugees. Hence, it was observed that a significant association continued until social distance towards refugees via SES, satisfaction with life, threat perception towards refugees, and Indirect 3, shown in Table 6, occurred significantly (γ = −0.1494, SE = 0.0211, 95% CI [−0.1918, −0.1090]). Indirect 1 was not significant since satisfaction with life had no significant effect on social distance towards refugees (γ = −0.0122, SE = 0.0087, 95% CI [−0.0377, 0.0138]). On the other hand, Indirect 2 was statistically significant because SES reduced threat perception towards refugees, and the diminished threat perception towards refugees lowered social distance towards refugees (γ = 0.1814, SE = 0.0592, 95% CI [0.0659, 0.2989]). Therefore, the two mediators fully mediate the relationship between socioeconomic status and social distance towards refugees in a serial causal order, as shown in Indirect 3 in Table 6. Therefore, hypothesis H11 was accepted.

Table 6.

Indirect effects of SES on SDtR.

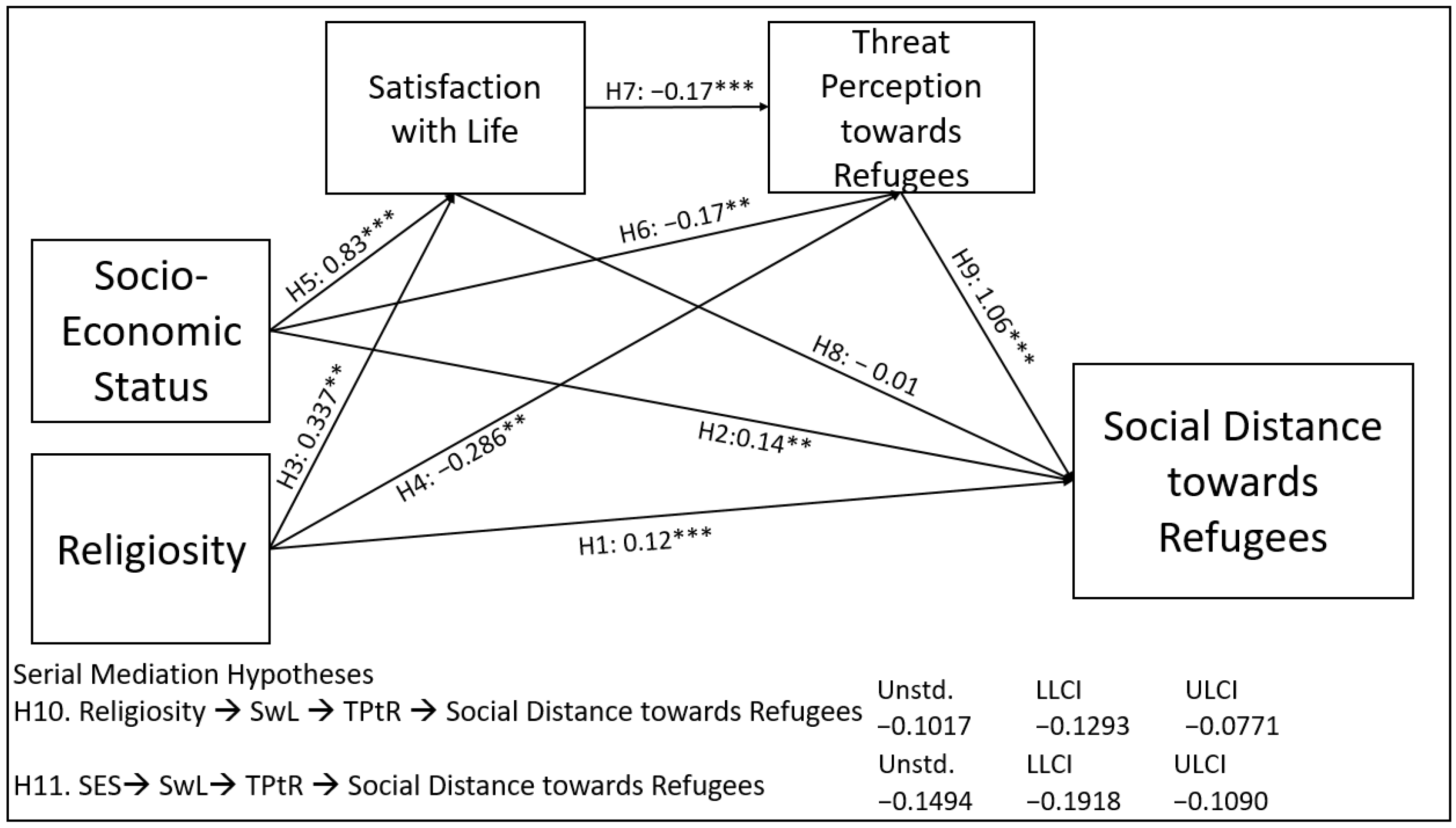

4.5. Results of the Proposed Research Model and Hypotheses

The results obtained as a result of the direct and serial mediation tests of the hypotheses shown in Figure 1, which represent the conceptual model of the research, are shown in

Figure 2

below. The direct effect values and significance levels between both factors are presented on the arrow line between the factors. In addition, the serial indirect effect values are shown in the lower part of

Figure 2

next to hypotheses H10 and H11. As shown in Figure 2, the reducing effects of religiosity and SES on social distance towards refugees were determined only through satisfaction with life and threat perception towards refugees.

Figure 2.

The proposed research model’s findings; ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

The direct and serial indirect hypotheses shown in the conceptual research model were tested. The results and significance levels of the tests are shown in Figure 2. In addition,

Table 7

shows the results of the hypotheses obtained as a result of the analyses. As a result, nine hypotheses were accepted, and two hypotheses were rejected. The hypotheses are explained in more detail in the Discussion section of the article. Finally, the research question was evaluated in the light of the results of the hypotheses.

Table 7.

Summary of hypothesis testing results.

5. Discussion

As a result of the internal turmoil that started in Syria in 2011, firstly, the neighboring countries of Syria and then many European countries were exposed to the influx of Syrian refugees. One of the countries most affected by this refugee influx has been Turkey. While many wealthy European countries rejected Syrians, the receiving countries received incomparable numbers of Syrian refugees that Turkey accepted with its open door policy. Although the racist and radical exclusionary approaches impact the perception of threat and negative attitudes towards refugees in European countries (Besley and Peters 2020), there are other additional reasons. These are the effect of immigrants on the increasing burden of the welfare state (Dempster and Hargrave 2017), the increase in social and economic problems (Fatıma 2019), the difficulties experienced in cultural adaptation, the fear of unemployment of the host people (Blanchflower and Shadforth 2009), and the increasing security fear and the negative perception used by the media about Muslim refugees based on terrorist acts (Kyuchukov 2016; Poushter 2016). Although Turkey hosts the highest number of refugees globally, the problems experienced in other countries are less experienced in Turkey. Due to the common historical, cultural, and religious characteristics, there have not been many negativities between the two communities. Therefore, despite being a middle-income country, Turkey’s context provides an unusual opportunity to understand how well Turkey has managed this difficult process at the administrative and societal levels. However, there are concerns that Syrians’ employment, health, and education opportunities will make it difficult for them to return if the Syrian civil war ends (Akcapar and Simsek 2018; Içduygu and Nimer 2019; Sunata and Abdulla 2019). These concerns cause Syrian refugees to be made a political tool, making the problem management difficult.

With this study, an attempt was made to understand the effect that the levels of religiosity, socioeconomic status, satisfaction with life, and threat perception towards refugees have on the attitudes of Turkish people towards refugees and how the causal chain relationship works in these attitudes. The attitudes of Turkish people were tested by correlation and direct effects, and indirect effect analyses tested the serial causal chain (serial mediation) process. While hypotheses H1, H2, and H8 were rejected in this study, hypotheses H3–H7 and H9–H11 were accepted. Below, first, the analyses of the direct effects and then the indirect effects and, finally, the evaluation of the research question, presented in the introduction, are discussed in line with the hypotheses and the current literature results.

5.1. Direct Effects

In this study, the effect of religiosity on social distance towards refugees varied according to different factors. For example, when there was no perceived threat towards refugees, religiosity had a negative effect on social distance towards refugees (Table 4, Step 3). However, when threat perception towards refugees was included in the analysis, the effect of religiosity on social distance towards refugees was positive (Table 4, Step 4). In other words, in the case of threat perception, the effect of religiosity is suppressed by the threat, religiosity becomes passive, and threat perception is active. Therefore, the effect of religiosity on social distance towards refugees was positive if threat perception was taken into account, and therefore the H1 hypothesis was rejected. There were positive and negative results in the relationship of religiosity with social distance towards refugees in the literature. Positive results were achieved in the effect of religiosity on social distance towards refugees, mostly due to far-right movements, white supremacist influence, pressure from authoritarian approaches, and increased threat perceptions (Carlson et al. 2019; Deslandes and Anderson 2019; Laythe et al. 2002; Perry et al. 2015; Rowatt et al. 2009; Şafak-Ayvazoğlu et al. 2021). On the contrary, some studies have found negative associations between religiosity and social distance towards refugees because religiosity would make individuals more social towards other groups. Additionally, religiosity can increase tolerance and contribute to improved well-being by connecting individuals within a particular social system in which individuals can contribute to one another (Blogowska et al. 2013; Cetin 2019; Páez et al. 2018; Pichon et al. 2007). Thus, empirical findings and the literature explain that religiosity is important in behaviors and social distance towards refugees, but its direction changes according to the threat perception.

The impact of socioeconomic status on social distance towards refugees was positive in the current study. Therefore, the H2 hypothesis based on the literature was rejected. In the literature, it was determined that societies with a low socioeconomic status generally exclude groups other than themselves, namely, refugees, because they see them as economic rivals, and they think that they will increase their current problems (Abdelaaty and Steele 2020; Halperin et al. 2007; Heath and Richards 2016). In addition, it was found that societies with an advanced socioeconomic status approach other groups and refugees with more moderate and socially inclusive practices, especially in European welfare states (Heizmann and Huth 2021; Hercowitz-Amir et al. 2017; Kuntz et al. 2017). However, the empirical result in this study is contrary to the literature, and socioeconomic status had a positive effect on social distance towards refugees. Moreover, this effect was observed to be lessened with the inclusion of threat perception towards refugees. The results related to the finding that improvement in socioeconomic status decreases threat perception and increases social distance can be explained by the understanding that “we do not see refugees as a threat unless they harm our well-being, but do not be too close to us”.

This study determined that religiosity had a positive association with satisfaction with life and a negative correlation with threat perception towards refugees. That is why hypotheses H3 and H4 were accepted. According to the literature, religiosity increases satisfaction with life. Religiosity improves the strength of individuals to endure adversities by reducing the distance between the current situation and expectations and makes problems part of the reward. Furthermore, it mitigates the detrimental impact of income disparity in life, leading individuals to come together to reduce their problems and ultimately increase their satisfaction with life levels (Ellison et al. 1989; Lim and Putnam 2010; Roberto et al. 2020; Yeniaras and Tugra 2016; Yonker et al. 2012). One of the remarkable findings of this study is that religiosity reduces threat perception towards refugees. Religiosity, in general, and Islam, in particular, accept different races, colors, and religions, not excluding out-groups and adopting harmony in differences. Based on this teaching of Islam, the current government used the Ansar and Muhajir approach to make the complex process more manageable. The literature on the perception of threat towards Syrians in Turkey supports the empirical findings obtained in this study (Erdoğan 2020; Gulmez 2019; Koçak 2021; Kocak et al. 2021; Şahin 2016). The fact that religiosity reduces the perception of threat towards refugees in Turkey is a unique model because refugees are seen as a threat in terms of economic, political, and security reasons in the world. Therefore, benefiting from religiosity and spirituality will decrease the increasing threat perception that disrupts societies’ inner peace.

The H5 and H6 hypotheses were accepted since a positive association was detected between socioeconomic status and satisfaction with life, and a negative association was found with threat perception towards refugees. In this study, the parents’ education and income levels, which are the components of socioeconomic status, can give family members an important status and life satisfaction in society. Satisfaction with life will naturally increase as education will provide a higher income with it. The empirical results obtained are consistent with the literature (Kendig et al. 2016; Ozdemir 2019). On the other hand, as the socioeconomic status of individuals increases, their perception of threat towards out-groups or refugees decreases (Pak and Elitsoy 2020; Vala and Pereira 2020). This is because the life satisfaction and self-esteem of those with an increasing socioeconomic status rise, and they do not see refugees as competitors in the labor market (Raymore et al. 2018; Twenge and Campbell 2016). On the contrary, they prefer to see refugees from an economic point of view and benefit from their labor, and thus threat perception towards refugees decreases in time (İçduygu and Diker 2017; Verkuyten and Nekuee 2001).

Hypothesis H7 was accepted, as satisfaction with life had a significant negative effect on threat perception towards refugees. In contrast, it did not significantly affect social distance towards refugees, and H8 was rejected. Although the threat perception and social distance towards refugees have political and security dimensions, they are mostly socioeconomic issues. In Turkey, a middle-income country, low-educated individuals with less job security and job opportunities perceive refugees, who carry out cheap labor, as a threat. Therefore, low-educated and low-income people think that refugees are likely to take their jobs (Wulfgramm 2011). However, with the benefits and satisfaction with life levels of those whose education and income are high, the perception of threat towards refugees decreases (Topal et al. 2017). However, on the contrary, some studies found that the societies of developed countries with high satisfaction with life have exclusionary attitudes towards refugees due to economic, political, and security reasons (Besley and Peters 2020; Dyduch-Hazar et al. 2019). In some studies, when it comes to national issues such as security and politics, it was found that satisfaction with life is suppressed, albeit at a high level, and the perception of threat towards refugees increases rapidly (Besley and Peters 2020; Klaus et al. 2018; Konukoğlu et al. 2020).

As individuals’ threat perception towards refugees increased, this study discovered that their social distance towards refugees increased as well. Accordingly, hypothesis H9 was accepted. It was found that there was a strong positive relationship between threat perception towards refugees and social distance towards refugees. When the feeling of threat by the host population is based on multiple aspects such as economics, politics, security, national identity, and public space, the exclusionary attitudes towards refugees rise, as is the case in many countries (Dias Matavelli et al. 2020; Saraçoğlu and Bélanger 2019). While the perception of mutual threat persists, there will likely be a potential societal risk in refugee-receiving communities for the foreseeable future. As the refugee crisis is multifaceted, both parties must be aware of their respective responsibilities. When it comes to reducing the feeling of threat, the host community should embrace a humanitarian approach that is tolerant of differences. It is important to emphasize that refugees have an attitude that will help them understand their basic responsibilities and fundamental rights, reducing the feeling of threat they face. In addition, religious approaches that bring people together, foster human fraternity, promote coexistence, and regard obstacles as gifts will play an essential role in lowering threat perception.

When demographic variables were evaluated, it was understood that education increased life satisfaction and decreased threat perception and social distance towards refugees, and those who have refugee neighbors had less threat perception and social distance towards refugees. Therefore, while life satisfaction increases with the individual’s education, the perception of threat and exclusion towards refugees decrease simultaneously. Similarly, it was determined that those with Syrian neighbors had less threat perception and exclusion towards refugees than those who did not. The literature shows that an increase in the education level of the host and the immigrant society and the strong religious and family ties facilitate the integration and adaptation process (Şafak-Ayvazoğlu et al. 2021; Silveira and Allebeck 2001). In addition, the fact that refugees and Turks are neighbors helps both sides to break their mutual prejudices and depoliticize themselves (Saraçoğlu and Bélanger 2021). However, being neighbors with Syrians sometimes led to very positive thoughts and feelings for some Turks, while others did not have any (Güney 2021). Therefore, it has been understood that both education and being a neighbor make a remarkable contribution to mutual integration and break both communities’ mutual prejudices.

5.2. Indirect Effects

The independent variables of religiosity and socioeconomic status (SES) were investigated for their impacts on social distance towards refugees in this study, conducted first through satisfaction with life and subsequently through threat perception towards refugees, with serial mediation. According to the findings, mediators had a statistically substantial impact on the causal chain that connected the independent factors to the dependent variable. As a result, there were statistically significant indirect effects observed in this study. Furthermore, it was understood from the Indirect 3 results in Table 5 and Table 6, which show both indirect effects, that the entire model had a significant causal chain. Accordingly, hypotheses H10 and H11 were accepted.

According to the results of the indirect analysis in Table 5, religiosity was found to have a positive impact on satisfaction with life. However, satisfaction with life did not significantly impact social distance towards refugees (Indirect 1). On the other hand, religiosity was observed to have a significant negative effect on threat perception towards refugees. In contrast, threat perception towards refugees significantly affected social distance towards refugees (Indirect 2). At the last stage, there was a significant causal chain from religiosity, satisfaction with life, and threat perception towards refugees to social distance towards refugees. Therefore, the whole serial mediating model was statistically significant (Indirect 3). Thus, it seems that satisfaction with life and threat perception have complementary roles. In other words, religion affects satisfaction with life positively, while satisfaction with life can only affect social distance towards refugees through threat perception towards refugees. Therefore, while religiosity improves satisfaction with life, the perception of threat decreases and eventually causes a reduction in the social distance (Indirect 3).

SES had a strong effect on life satisfaction, but life satisfaction did not affect social distance towards refugees, as shown in Table 6 (Indirect 1). SES, on the other hand, had a significant negative effect on the perceived threat from refugees. Additionally, threat perceptions towards refugees affected social distance (Indirect 2). The serial mediation model contains a statistically significant causal chain that begins from socioeconomic status, life satisfaction, and threat perceptions towards refugees to social distance towards refugees (Indirect 3). Thus, it appears that life satisfaction and threat perception are complementary. In other words, SES affects satisfaction with life positively, while satisfaction with life can only affect social distance towards refugees through threat perception towards refugees. Thus, while SES increases life satisfaction, it also decreases threat perception, lowering social distance (Indirect 3). Concerning the indirect effect, it was discovered that, while religiosity and socioeconomic status (SES) decreased social distance towards refugees, they first raised life satisfaction, and subsequently, the increased life satisfaction reduced threat perception.

5.3. Evaluation of Research Question

A research question was asked at the beginning of the study, “How is the relationship realized between religiosity, SES, and social distance towards refugees?” To this end, the study investigated how religiosity and SES affect social distance towards refugees in Turkey. Satisfaction with life and threat perception towards refugees were used as serial mediators in this study. We found that both mediating variables complement each other and add meaning to the conceptual model we established. That is, both religiosity and SES increase life satisfaction. However, it was found that life satisfaction did not directly affect social distance towards refugees. However, it was found that increasing life satisfaction decreased the perception of threat towards refugees, and then the reduced threat perception diminished social distance towards refugees, as shown in Table 5 and Table 6. According to this result, the religious, cultural, and social structure underlying the success of Turkey, which is a good example in the practices towards refugees, is briefly evaluated below.

The refugee problem has become an increasingly important problem in many countries. According to international law and humanitarian approaches, Turkey has allowed Syrian refugees to receive health and education services and participate in labor markets. The common historical, cultural, and religious ties of Syrians and Turks facilitated their acceptance and integration. However, the Syrians dispersed to various cities, and their numbers grew to be almost as many as the local population in certain places. Although there were problems in economic, security, and policy issues, there were no serious reactions. Sometimes, these problems are exacerbated by the media and politics, occupying more of the agenda. In addition to the basic education and health services provided from the beginning of the process (Saleh et al. 2018), the government has tried to strengthen acceptance and integration by highlighting the common religious ties of Turks and Syrians.

Turkish society has different religions, ethnic structures, cultures, and world views. Although the Turkish state is secular, religion has an exceptional place in the lives of the majority of the people. Turkish people are predominantly a conservative society as they are mostly religious. The majority of those who define themselves as religious also have national feelings because religion, multiculturalism, and nationalism are linked notions in Turkish society for historical and cultural motives (Koçak 2021; Onar 2009). However, while socialist approaches constitute an important group, the number of liberals is increasing, albeit it is small (Konda 2010). However, it can be seen that socialist and liberal groups give importance to religion and religious values, show respect, and practice from time to time, although not as much as conservatives. In a recent study, the rate of those who pray five times a day was 24.4% in Turkey (Aydın 2020). In one study, the rate of those who define themselves as religious was 62.5%, while those who define themselves as a believer or someone who has belief was 34.6% in Turkey. Therefore, religion takes place in the life of society at a rate of 97.1% in total (Konda 2010). Although atheism and deism have started to be seen in recent years (Kenton 2019), the values revealed by the religion of Islam impact the social culture, traditions, and individual preferences of Turkish society.

Turkey is a unique country with a strong Islamic aspect and is close to Western culture and values. The culture of living together with different societies throughout history is pervasive in Turkey. Therefore, it would be incomplete to explain the relatively positive attitudes of Turks towards refugees with the fact that Syrians became Muslims, as societies belonging to different religions have been living peacefully for centuries in Turkey. On the one hand, most Turkish and Syrian inhabitants have similar beliefs, generating a favorable attitude towards refugees. On the other hand, it was discovered that positive attitudes towards Armenians, Jews, and Greeks who have various religions and live in Turkey exceeded those for current Muslim refugees (Koçak 2021; Yitmen and Verkuyten 2018). Therefore, it may be wrong to attribute the positive attitude towards refugees only to religious brotherhood. The belief in Islam encourages the coexistence of members of Islam with members of different faiths. Islam’s acceptance of individuals of diverse faiths and ethnicities promotes harmony. The Muslims’ guidebook, the Qur’an, contributes to this process by some verses such as “to you is your religion, and to me is my religion” (Qur’an 2001, vol. 109, p. 6).

6. Limitations

In this study, the effect of religiosity and SES on the attitude of Turks towards Syrians was investigated. While it is noteworthy that this study was conducted only with Turks, it is necessary to conduct and compare similar studies with other refugee-receiving societies. Another limitation is that the study was conducted only on Syrians. However, similar studies need to be carried out on the many refugees from Afghanistan in Turkey that have arrived in recent years. In addition, similar studies should be conducted with refugees to understand what effect religiosity has on them. Since the survey was conducted during the most intense period of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was carried out only in the online environment. For this reason, thoughts and approaches could not be obtained by meeting face to face with the Turks. The religiosity questions used in this study generally investigated whether the actions required by Islam were generally applied or not. However, more specific questions that separate individual and social religious requirements could have strengthened this study. Moreover, sufficient scales to be used in research related to refugees have not been developed. Therefore, developing new scales and conducting research with the host society and refugees in different periods will contribute to academia and policymakers.

7. Conclusions and Some Implications

In this study, the effect of religiosity, SES, satisfaction with life, and threat perception towards refugees on the attitudes of Turks towards Syrian refugees in Turkey was investigated. While the life satisfaction of refugees and its predictors have been examined in other studies, this study focused on the host people. This study surveyed 1453 individuals from different regions of Turkey, and it was designed as quantitative and cross-sectional. The serial mediating effect of satisfaction with life and threat perception towards refugees was tested on the impact of religiosity and SES on social distance towards refugees. For this purpose, correlation, direct, and indirect analyses were used. In this study on the approach of the host population, which was previously not focused on enough, it was determined that the religiosity and SES levels of the host people reduced social distance towards refugees only through life satisfaction and threat perception.

In every refugee-receiving country, the interaction between refugees and the host community can be problematic. For this reason, mainly economic, security, and political threat perceptions need to be successfully managed mutually. Otherwise, refugee-receiving countries will have to cope with social chaos as well as a financial burden. This study found that religiosity was especially effective in this challenging process in Turkey. Therefore, if Turkey is taken as a model, it would be appropriate for Islam’s inclusive approach to different beliefs, races, cultures, and traditions to be included in this model. For this reason, it is necessary to highlight the religious teachings and spirituality that accept differences, see difficulties as rewards, and provide inner peace to the individual in the social arena. Moreover, to this end, it will be necessary for policymakers, non-governmental organizations, educators, and experts to carry out more work in schools and families.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Aarø, Leif Edvard, Alan Flisher, Sylvia Kaaya, Hans Onya, Francis Namisi, and Annegreet Wubs. 2009. Parental education as an indicator of socioeconomic status: Improving quality of data by requiring consistency across measurement occasions. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 37: 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaaty, Lamis, and Liza G. Steele. 2020. Explaining Attitudes toward Refugees and Immigrants in Europe. Political Studies, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akar, Sevda, and Mustafa Erdoğdu. 2019. Syrian Refugees in Turkey and Integration Problem Ahead. Journal of International Migration and Integration 20: 925–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcapar, Sebnem Koser, and Dogus Simsek. 2018. The Politics of Syrian Refugees in Turkey: A Question of Inclusion and Exclusion through Citizenship. Social Inclusion 6: 176–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aker, Deniz Yetkin. 2019. Yabancılara Karşı Olumsuz Hisler: Avrupa Birliği’ne Üye Olmayan Ülkelerden Gelen Göçle İlgili Kamuoyu Araştırması. Savunma Bilimleri Dergisi 18: 135–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, Gordon, and Michael Ross. 1967. Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 5: 432–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, Joel. 2018. Implicit and Explicit Attitudes Towards Asylum Seekers in Australia: Demographic and Ideological Correlates. Australian Psychologist 53: 181–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, Mustafa. 2020. Türkiye Eğilimleri, Kantitatif Araştırma Raporu 07 Ocak 2021. Available online: https://www.khas.edu.tr/sites/khas.edu.tr/files/inline-files/TEA2020_Tur_WEBRAPOR_1.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Bansak, Kirk, Jens Hainmueller, and Dominik Hangartner. 2016. How economic, humanitarian, and religious concerns shape European attitudes toward asylum seekers. Science 354: 217–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benda, Brent, Sandra Pope, and Kelly Kelleher. 2006. Church attendance or religiousness: Their relationship to adolescents’ use of alcohol, other drugs, and delinquency. In Spirituality and Religiousness and Alcohol/Other Drug Problems: Treatment and Recovery Perspectives. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis, pp. 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergan, Anne, and Jasmin Tahmeseb McConatha. 2001. Religiosity and Life Satisfaction. Activities, Adaptation & Aging 24: 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Peter. 1967. The Scared Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion. Doubleday. Available online: https://www.worldcat.org/title/sacred-canopy-elements-of-a-sociological-theory-of-religion/oclc/374304. (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Besley, Tina, and Michael Peters. 2020. Terrorism, trauma, tolerance: Bearing witness to white supremacist attack on Muslims in Christchurch, New Zealand. Educational Philosophy and Theory 52: 109–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichi, Rita. 2008. Mixed Approach to Measuring Social Distance. Cognitie, Creier, Comportament 12: 487. [Google Scholar]

- Bidinger, Sarah. 2015. Syrian Refugees and the Right to Work: Developing Temporary Protection in Turkey. Boston University International Law Journal, 223–49. Available online: https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/builj33&id=229&div=&collection (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Blanchflower, David, and Chris Shadforth. 2009. Fear, Unemployment and Migration. The Economic Journal 119: F136–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blogowska, Joanna, Catherine Lambert, and Vassilis Saroglou. 2013. Religious prosociality and aggression: It’s real. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 524–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brell, Courtney, Christian Dustmann, and Ian Preston. 2020. The labor market integration of refugee migrants in high-income countries. Journal of Economic Perspectives 34: 94–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burris, Val, Emery Smith, and Ann Strahm. 2000. White Supremacist Networks on the Internet. Sociological Focus 33: 215–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canatan, Kadir. 2013. Avrupa Toplumlarının Göç Algıları ve Tutumları: Sosyolojik Bir Yaklaşım. İstanbul Üniversitesi Sosyoloji Dergisi. 3, pp. 317–32. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/iusosyoloji/5023 (accessed on 4 April 2021).

- Carlson, Marianne Millen, Stacey McElroy, Jamie Aten, Edward Davis, Daryl Van Tongeren, Joshua Hook, and Don Davis. 2019. We Welcome Refugees? Understanding the Relationship between Religious Orientation, Religious Commitment, Personality, and Prejudicial Attitudes toward Syrian Refugees. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 29: 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, Mehmet. 2019. Effects of Religious Participation on Social Inclusion and Existential Well-Being Levels of Muslim Refugees and Immigrants in Turkey. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 29: 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetindamar, Dilek, Vishal Gupta, Esra Karadeniz, and Nilufer Egrican. 2011. What the numbers tell: The impact of human, family and financial capital on women and men’s entry into entrepreneurship in Turkey. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 24: 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumbler, Neale. 1996. An empirical test of a theory of factors affecting life satisfaction: Understanding the role of religious experience. Journal of Psychology and Theology 24: 220–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citrin, Jack, Donald Green, Christopher Muste, and Cara Wong. 1997. Public opinion toward immigration reform: The role of economic motivations. Journal of Politics 59: 858–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenders, Marcel, Mérove Gijsberts, and Peer Scheepers. 2017. Resistance to the Presence of Immigrants and Refugees in 22 Countries. In Nationalism and Exclusion of Migrants: Cross-National Comparisons. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis, pp. 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowling, Misha Mei, and Joel Anderson. 2019. The Role of Christianity and Islam in Explaining Prejudice against Asylum Seekers: Evidence from Malaysia. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 29: 108–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowling, Misha Mei, Joel Anderson, and Rose Ferguson. 2019. Prejudice-relevant Correlates of Attitudes towards Refugees: A Meta-analysis. Journal of Refugee Studies 32: 502–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dağlı, Abidin, and Nigah Baysal. 2016. Yaşam Doyumu Ölçeğinin Türkçe’ye Uyarlanması: Geçerlilik ve Güvenilirlik Çalışması. Elektronik Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi 15: 1250–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danış, Didem, and Dilara Nazlı. 2019. A Faithful Alliance Between the Civil Society and the State: Actors and Mechanisms of Accommodating Syrian Refugees in Istanbul. International Migration 57: 143–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempster, Helen, and Karen Hargrave. 2017. Understanding Public Attitudes towards Refugees and Migrants. Working Papers 512. London: Chatham House and ODI’s Forum on Refugee and Migration Policy Initiative, p. 512. [Google Scholar]

- Deslandes, Christine, and Joel Anderson. 2019. Religion and Prejudice Toward Immigrants and Refugees: A Meta-Analytic Review. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 29: 128–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias Matavelli, Rafaela, Saul Neves de Jesus, Patrícia Pinto, and João Viseu. 2020. Social Support as a moderator of the relationShip between financial threat and life SatiSfaction. Journal of Spatial and Organizational Dynamics 8: 16–28. Available online: https://www.jsod-cieo.net/journal/index.php/jsod/article/view/221 (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Diener, Ed, Robert A. Emmons, Randy J. Larsem, and Sharon Griffin. 1985. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 49: 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunwoody, Philip, and Sam McFarland. 2018. Support for Anti-Muslim Policies: The Role of Political Traits and Threat Perception. Political Psychology 39: 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyduch-Hazar, Karolina, Blazej Mrozinski, and Agnieszka Golec de Zavala. 2019. Collective Narcissism and In-Group Satisfaction Predict Opposite Attitudes Toward Refugees via Attribution of Hostility. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, Christopher, David Gay, and Thomas Glass. 1989. Does Religious Commitment Contribute to Individual Life Satisfaction? Social Forces 68: 100–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]