Abstract

In early 2020, Jain diaspora communities and organizations that had been painstakingly built over the past decades were faced with the far-reaching consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic and its concomitant restrictions. With the possibility of regular face-to-face contact and participation in recurring events—praying, eating, learning, and meditating together—severely limited in most places, organizations were compelled to make a choice. They either had to suspend their activities, leaving members to organize their religious activities on an individual or household basis, or pursue the continuation of some of their habitual activities in an online format, relying on their members’ motivation and technical skills. This study will explore how many Jain organizations in London took to digital media in its different forms to continue to engage with their members throughout 2020. Looking at a selection of websites and social media channels, it will examine online discourses that reveal the social and mental impact of the pandemic on Jains and the broader community, explore the relocation of activities to the digital realm, and assess participation in these activities. In doing so, this article will open a discussion on the long-term effects of this crisis-induced digital turn in Jain religious praxis, and in socio-cultural life in general.

Keywords:

COVID-19; digital religion; media and religion; Jainism; diaspora; social media; religion; pandemic 1. Introduction

1.1. The London Jain Community on the Eve of the Pandemic

With its high-density Jain community of an estimated 25,000 individuals, the city of London is home to one of the largest Jain communities outside India. Although the first Jain visited the United Kingdom as early as 1892, the number of Jains settling (semi-)permanently in the United Kingdom remained very low until the 1960s (Jain 2011, p. 96), and those that did come to the United Kingdom did so mostly for purposes of higher education. As a rule, these migrants did not bring families along to the United Kingdom and did not settle permanently. However, this changed when British colonial rule came to an end in East Africa in the early sixties (Shah 2012, p. 8). The independence of the East African nations saw successive nationalist and socialist governments moving to Africanize the economy and define citizenship. The regulations and restrictions thus imposed compelled 70% of the estimated 360,000 South Asians then settled there to leave (Tandon and Raphael 1984, p. 2). Consequently, 100,000 of these East African Asians moved to the United Kingdom, among whom were an estimated 15,000 Jains (Jain 2011, p. 96). The circumstances and scale of this extraordinary wave of migration were most formative to Jainism in the United Kingdom. In the following decades, these twice-migrants from East Africa have been joined by Jains who migrated from India or elsewhere, creating a diverse community that gave rise to a large number of organizations.

These Jain organizations are dotted around London, but the vast majority of activities and events takes place in a 5 km by 5 km square in North-West London (around Kingsbury, Kenton, Harrow, and Edgware). On any day, London Jains have a choice of different religious and social activities they can attend. Pāṭhśālā (religious classes) for adults and children are organized by a number of organizations, at different locations in the greater London area (e.g., SCVP School1, OAUK2, SDJA3, JVB London4), and different derāsars (Jain temples) are open to those who wish to worship (e.g., OAUK, SDJA, Mahavir Foundation5, JainNetwork6). In addition to providing religious classes and managing derāsars, Jain organizations offer a variety of activities, including bhakti (devotional music) sessions, yoga, shared meals, arts and crafts classes, study groups, walks, and so on. Although some activities are aimed at specific communities, religious groups, or age brackets, most are open to all interested individuals, and it is not uncommon to meet the same people at different events and locations in the same week.

All this changed in March 2020. Together with much of everyday life, this busy Jain landscape came to a sudden halt when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. The U.K. government imposed a stay-at-home order and forced cultural venues—including religious venues—to close on 26 March. However, even before the lockdown was officially enforced, most Jain organizations had already moved to cancel their educational, cultural, and social activities and closed the temples, as illustrated by the excerpt from a message posted on Mahavir Foundation’s Facebook page on 22 March.

ATTENTION! DERASAR ATTENDANCE AND GATHERINGJai Jinendra and PranaamI am sure all of you are following the grave effects of COVID-19. […] Our prime objective is the welfare of our Pujari, Devotees and our Community. With a heavy heart, Mahavir Foundation, Kenton Derasar will be closed to the public for the foreseeable future and with immediate effect. […] Please, follow our social media for updates on Mahavir Foundation decisions. […] KEEP WELL AND SAFEThank you for your support. I am sure together we will see brighter days if we heed the warnings of our government.[MF FB 22/3/2020, accessed on 5 March 2021]

The hubs of Jain activity around London fell silent. Infrastructure that took years and millions in community funds to build stood empty. Organizations now had to rethink, recalibrate, and reorganize: How could they continue to function and support their members as well as the wider community in this difficult time? In the first weeks, the general emphasis was on providing correct information on the virus and safety measures as well as setting up charity efforts and COVID-19-related social work. As it became clear the restrictions would remain in place for a longer period of time, organizations had to face the question of what to do with their regular activities. Although collective ritual activities are common in a sizable community such as the one in London, many Jain religious practices are essentially performed on an individual basis. The tradition does not mandate congregational worship or even temple visits. As such, and in contrast to Catholic and Islamic practice, COVID-19 restrictions did not directly clash with Jain doctrine (see e.g., Al-Astewani 2021 for an elaboration on the implications of COVID-19 restrictions on Islamic practice in the United Kingdom). The pandemic could have resulted in a turn towards more individual modes of religious praxis and a temporary cessation of communal activities without posing any great doctrinal difficulty. Collective activities—both religious and social—form the core business of Jain organizations, however, and have been instrumental in cultivating and building the community as we know it today (Shah 2017). Therefore, as the lockdown and restrictions wore on, most Jain organizations worked to increase their online presence and organize either their regular activities or an alternative program in a virtual form. On 6 April, the first larger-scale online event took place. Young Jains UK7 organized celebrations to honor the 24th Tīrthaṅkara’s8 birthday in the form of an hour of song and storytelling.9 A total of 400 participants were present, providing an early indication of the need (a part of) the community felt to remain connected through religious and social events, even under lockdown restrictions.

1.2. Method and Setup

The complex relationship between religion and digital media has been a topic of increasing interest and research for more than three decades. The materials presented in this article illustrate how the offline and the online world are not strictly separated, but instead blend together and extend into each other, and how available media and technologies and religious actors mutually influence each other. This article thus affirms Heidi Campbell’s concept of the religious-social shaping of technology (Campbell 2005, 2013). In addition to theoretical discussions on religion and digital media, case studies have contributed to a more contextualized understanding of digital religion. Such case studies focusing specifically on South Asian religious traditions include Xenia Zeiler’s Digital Hinduism (Zeiler 2020) as well as Murali Balaji’s slightly earlier volume by the same name (Balaji 2018) on Hinduism, Gregory Price Grieve and Daniel Veidlinger’s The pixel in the Lotus on Buddhism (Grieve and Veidlinger 2014), and my own works on Jainism (Vekemans 2014, 2019a, 2020, 2021; Vekemans and Vandevelde 2018). Although these studies discuss different traditions with different doctrinal rules and sensibilities that impact the ways in which digital media are engaged with for religious purposes, they have many tropes and findings in common. They all conclude that, in the past decades, religious actors and organizations have taken to digital media. They have done so primarily to make information known (cf. Chris Helland’s religion online (Helland 2000, 2005)). This information can be religious in nature (e.g., expositions on doctrine, e-versions of prayer books) or purely practical (e.g., directions to and opening hours of a religious organization). In addition to this primary function of providing information, researchers examining different traditions note efforts to turn digital media into a more participatory platform for discussion and religious praxis (cf. Chris Helland’s online religion (Helland 2000, 2005)). They also note how the recent proliferation of different media platforms and technologies greatly broadened the scope of what type of content can be shared, and how it can be accessed, which in turn has made the distinction between informational and practice-focused materials even more tenuous.

An exploration of Jainism’s digital presence revealed that Jains started using the Internet as a repository for religious information as early as the mid-1990s (e.g., Jainworld.com, accessed 10 May 2021). Consistent with the findings discussed above, most Jain websites have a clear informational/organizational focus with limited to no room for peer-to-peer discussion. Websites providing online ritual spaces and online resources to facilitate religious practices have existed since the early 2000s, but are rare. The advent of social media has invited more participation and peer-to-peer exchange, and a recent examination of Jain mobile applications found a significant amount of devotional materials and ritual resources (Vekemans 2019b). Approaching these digital sources from the perspective of potential users has revealed some skepticism about the use of the Internet as a primary source of doctrinal information, usually hinging on questions of authority and source (Vekemans 2019a). The same approach found strong skepticism concerning the usefulness of different forms of online rituals and events, which were generally only considered a last-resort option. Objections are raised regarding the mind-set of users/participants, the purity and sacredness of virtual environments and devices, and—where applicable—the lack of a social dimension (Vekemans and Vandevelde 2018). Similar objections were noted in research on online rituals in Hinduism (Karapanagiotis 2010; Scheifinger 2008).10

Although Jainism, and Jain organizations and individuals, were present and active in the digital world before the COVID-19 pandemic, the discussion below illustrates how both the type of online activities and the attitudes towards them have changed considerably. To date, published research on the effects of a crisis of the scope and impact of the 2020 pandemic on the relationship between religion and digital media is scarce, and consists mostly of case studies examining different religions from a variety of disciplinary perspectives—including law, medicine, and psychology, as well as theology, religious studies, and anthropology (e.g., Thomas and Barbato 2020; Parish 2020; Al-Astewani 2021; Wildman et al. 2020, and the corona dossier blog on the Religious Matters in an Entangled World research project). Tilak Parekh’s work on the digital presence of the Hindu temple in Neasden is particularly interesting, as it situated itself in a context that is in many respects similar to the one this article discusses (Parekh 2020). This article wishes to contribute to this emerging discussion by presenting one instance of a crisis-induced digital leap in a detailed and localized way. The choice of London-based Jain organizations is informed by both the unique density of Jain individuals and organizations, which allows for some comparison of organizational strategies, and by the authors’ prior experience in the same field, which enables a better informed juxtaposition of the pre- and post-COVID situation. The following sections examine how Jain organizations in London took to digital media in an attempt to engage with their members in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and its concomitant restrictions, with a focus on the digital relocation of events. To account for changes in COVID-19 restrictions and potential effects of digital fatigue, this article looks at online discourses, activities, and participation rates over a period of ten months, from March 2020 until December 2020.

It bears mention that the pandemic that prompted the digital relocation on which this article focusses also required researchers to rethink and adapt their methods. As international travel was severely restricted by both national governments and academic institutions for most of 2020, a shift to online versions of ethnographic methods of data gathering was necessary. As such, the data that inform this research were gathered through a close observation of websites and social media accounts (Facebook and YouTube) of London-based Jain organizations. In addition to this, I had some informal online conversations with Jains living in London. However, it will take some temporal distance and significantly more in situ data gathering to really come to grips with the long-term impact of the pandemic and the digital leap that followed in its wake on the social fabric of religious communities.

The next section of this article deals with crisis and sets out to provide a simplified timeline of COVID-19 restrictions and discusses the initial impact of the pandemic on religious life. It subsequently examines the first response of Jain organizations. The following section focuses on continuation. It investigates how different organizations took to digital media to continue to engage with their members despite restrictions on physical movement and social interaction. It details the type and frequency of events and the degree of participation. In conclusion, this article discusses serendipitous side effects of digital relocation and reiterates how the current crisis-induced wealth of online activities contrasts with previous findings indicating that online activities, especially rituals, were generally not considered full alternatives to in situ practices by diasporic Jains (Vekemans and Vandevelde 2018, Vekemans 2019a). This prompts the question of whether this crisis-induced digital turn may herald some longer-term changes in the relationship between Jain praxis and digital media. However, as the pandemic rages on at the time of writing, any answers to such questions must remain speculative for the time being.

2. Jain Community in Times of Crisis

2.1. A Timeline of Restrictions

As the national health situation in the United Kingdom worsened and countries in continental Europe had already implemented stringent measures to minimize further spread of the virus, Prime Minister Boris Johnson issued the strong advice to stop non-essential travel and contact on 16 March.11 Subsequently, the U.K. government announced a lockdown, which was implemented from 26 March. Cafes, pubs, restaurants, and schools, as well as nightclubs, theatres, cinemas, gyms, and places of worship, had to close and social distancing was enforced. Jain organizations in London were thus obliged to cancel their planned events, and temples were to be closed to the public. In fact, most Jain organizations had already cancelled their activities and closed their facilities before the official start of the lockdown. Jain Vishva Bharati London sent an e-mail bulletin announcing the cancellation of their events until further notice on 11 March. SCVP School and Oshwal Association UK followed on 12 March. A week before the lockdown was implemented on 26 March, the pandemic had already brought organized Jain activity in London to a halt. Although restrictions were subsequently loosened in three amendments to the regulations, it was only on 15 June that places of worship were allowed to open again for private prayer (as opposed to congregational worship), provided the basic rules of social distancing and hygiene were adhered to and enforced. On 4 July, an updated version of the regulations allowed places of worship to open more generally, although indoor gatherings were limited to 30 people, and the basic rules of social distancing and hygiene were to be followed at all times. From 8 August, face coverings became mandatory in places of worship. The reopening of the temples from June onwards was a joyous occasion as events such as the reopening ceremony livestreamed on the Mahavir Foundation YouTube channel11 (cf. Figure 1) and messages such as the excerpt from the SDJA’s website below illustrate.

Mandir reopening hooray!!Jai Jinendra!We know you are all eager to do Dev Darshan in person at the mandir, so, following the recent government guidelines (www.gov.uk) to open places of worship by Monday 15 June 15, we are pleased to announce that the mandir will be OPEN from this coming Monday for PRIVATE worship only. This means that we will not be able to have any communal activities such as abhishek, puja or lectures, in order to maintain social distancing guidelines.13[SDJA blog, 11 June 2020, accessed on 8 March 2021]

Figure 1.

Screenshot showing devotees standing on marked squares on the temple floor to ensure social distancing.

However, in spite of the enthusiasm the reopening of the temples created, the gradual easing of restrictions over summer did not result in a resumption of Jain community life as it was before the pandemic. Jain organizations decided to continue with virtual events. This decision was partially informed by a general sense of caution and care for the significant number of elderly community members. However, it was also driven by the limitations to the number of participants in combination with the necessity of social distancing that rendered a return to communal religious activities and events impractical, if not impossible.

Figure 1 illustrates the impact of social distancing on a typical Jain temple space. Marked squares on the floor of the Kenton derāsar indicate where a devotee should stand to ensure appropriate distance to others. Whereas it is not unusual for devotees to sit some way apart from each other for individual practices such as mantra recitation and meditation, this particular derāsar has a relatively small hall, which is often filled with families and small groups. In accordance with restrictions, this popular temple-space can accommodate a corona-proof maximum of twelve devotees. The limited capacity even compelled the board to close the temple for the weekend of 14 and 15 November, when they feared Jain festivals would draw an unmanageable crowd owing to which social distancing would be difficult to enforce.

Expecting a further easing of restrictions after the summer holidays, some organizations had hoped to be able to (partly) resume normal activities, and had started to prepare accordingly. However, September brought a sobering surge in infections, which translated to more restrictions, including the ‘rule of six’ for indoor and outdoor gatherings. October saw the introduction of a new tier-based system of restrictions in England. A second national lockdown was imposed from 5 November, which banned collective worship until 2 December. As the situation in many regions, including London, worsened, Tier 4 restrictions were imposed from 21 December, and a third national lockdown started on 5 January 2021. Most Jain organizations’ premises remained closed for most of the period between March and December 2020. Temples were open from the easing of restrictions mid-June until the implementation of Tier 4 restrictions on 21 December, but in practice only facilitated individual darśan14 by a very limited number of devotees at any one time.

2.2. Early Responses

Although the full human and social costs of the current crisis cannot be tallied yet, it is clear that the scale of the pandemic and the impact of the restrictions imposed by the government to attempt to control it have impacted the fiber of society in a myriad of ways. The immediate effects of the first ‘lockdown’ were an abrupt end to normal patterns of activity—social, economic, religious, and cultural—for most, plus job insecurity and loss of income for some. As established relationships of care were disrupted, care for children, people with disabilities, and the elderly had to be quickly renegotiated to fit within the narrow allowances of the restrictions. These sudden changes had an impact on the mental wellbeing and self-sufficiency of many in the United Kingdom and beyond. The initial responses of Jain organizations to the shock of the first lockdown and its immediate effects included the provision of tailored information on the health situation, efforts to set up charity work, and attempts to provide mental support their members in a period of uncertainty and stress.

As the number of patients in hospitals rose, and South Asian and Black communities seemed to be particularly at risk from the virus15 (Razai et al. 2021), community organizations felt they had to step up and inform members on COVID-19, restrictions, and precautions. Not all organizations included in this study took this role up to the same extent. Whereas some limited themselves to sharing information that impacted regular events, others went further and shared medical information put forward by the NHS and WHO. Although such reliable information was available, it was not necessarily available in a format accessible to all. Accordingly, some organizations produced custom-made information tailored to their members. Oshwal Association UK posted information in Gujarati on their website and a link to it on their website as early as 30 March, and organized a Q&A with qualified doctors and scientists from within the Jain community on Zoom, which was also streamed on YouTube on 12 April.16 Although most of the Q&A was conducted in English, the event ended with a summary of the main points in Gujarati. OneJAIN17 organized similar Q&As, and provided information in Gujarati and Hindi on their website.18 JVB London perhaps went furthest in this drive to provide members of the Jain community with reliable health advice, and set up a system whereby telephonic medical advice and guidance could be accessed.19 Providing information remained important throughout the year and, indeed, as the vaccination effort started, a new wave of Q&As and seminars on COVID-19 and vaccines could be discerned on Jain organization’s social media in the first months of 2021.

As the pandemic and restrictions wore on, the societal upheaval brought about by the first lockdown prompted a range of Jain organizations to set up a volunteer force and raise funds for charity projects in support of the wider community. These projects were aimed primarily to alleviate practical needs and show support for the NHS. The two Facebook messages included below—both posted in the first month of the first lockdown—illustrate the type of needs the organizations sought to address.

COVID-19 Help groupThese are challenging times with challenged individuals. We have a small team of members who are available to support you and/or anyone you know for:

Similar services were set up by other Jain organizations, including OAUK (who posted about COVID relief on Facebook from 30 March and set up a page on their website matching of volunteers and those requesting assistance at the start of April). In addition to their own charity and volunteering activities (seva), funds were raised and volunteers mobilized to support local organizations such as homeless shelters (OA South), food banks (SCVP), and meal deliveries for the elderly (SCVP). Oshwal Association provided meal services for NHS workers at local hospitals. Calls for donations for pandemic relief in India also circulated from April 2020, most often for projects of India-based organizations with local affiliates in the United Kingdom (JITO UK20, Veerayatan (SCVP)).

Next to these systems put in place to take care of primary needs like food and medicine, the continuing mental wellbeing of the community was a point of concern from the start. The organizations that set up volunteer groups usually included “providing someone to talk to” in their list of services offered (see the citations above). JVB(L) offered personal consultations with one of their ordained nuns (samaṇīs):

Many people are facing health issues, acute fear, anxiety including physical, mental and emotional distress due to the current Corona pandemic. Dr. Samani Pratibha Pragyaji is happy to be contacted for personal consultation by any member of our society should they need spiritual guidance and blessings. […]Telephone: […] 2 p.m.–4 p.m. (only if it is critical or an emergency she can be contacted at any time).[JVB-L e-mail bulletin 30 March 2020]

In addition to one-on-one help and counselling, three types of online events were organized to address and improve issues of mental wellbeing. First, talks and information sessions on dealing with anxiety and wellbeing were noticeably prevalent in the first months of the pandemic, and continue to be organized sporadically at the time of writing. Examples of early activities explicitly engaging with the mental health effects of the pandemic and the (first) lockdown are Young Jains UK’s Enriching Conversations21 with themes such as ‘Finding Calm in the Chaos’, ‘Dharma and Mental Health’, and ‘Looking at the bigger picture’. These conversations, organized on Zoom, and not streamed publically, are clearly meant to offer interested members and non-members a safe platform to discuss. For Mental Health Awareness Week at the end of May, they also shared links to different mental health organizations on their Facebook page. OAUK organized a Mental Wellbeing Webinar on 24 May. Second, bodily practices impacting physical and mental health were also among the first activities to be organized in a virtual format. OA started different virtual yoga and fitness sessions in early April. Other organizations offering such classes online are Navnat22 and Mahavir Foundation. Meditation sessions were on offer by JVB and SCVP. Lastly, the relocation of regular activities to online platforms, discussed in the next section, also had a significant impact on the mental wellbeing of Jain community members. In addition to seeking to alleviate practical problems and uncertainties, this relocation aimed to re-establish some form of normalcy, keep the Jain community connected, and ensure the continuing relevance of Jain institutions and organizations to their members.

3. Continuation: Relocation to the Digital

When the pandemic struck, Jain organizations set forth to inform members on current developments and guidelines with regard to the pandemic, and mobilizing support networks to alleviate practical, material, and mental needs of Jains and the broader community. As traditional modes of communication such as printed newsletters, bulletin boards, and word of mouth were no longer useable because of the lockdown restrictions, websites and social media accounts acquired a new importance to Jain organizations and their members. Furthermore, Jain organizations started moving beyond the purely informational, scheduling religious as well as social activities and events in a virtual format. Whereas such virtual events were rare before the COVID-19 pandemic, by April 2020, they had become the norm. Although some organizations took longer than others to adopt virtual events, this relocation of regular events to the online realm usually came somewhat later than the early responses discussed above (organizing charity and providing information as well as mental support). It followed when it became clear that the COVID-19 restrictions would remain in place for a longer period of time.

In a community where virtual events were rare before the pandemic hit, the digital relocation of events that took place in the spring of 2020 presented a—in some cases steep—learning curve for both participants and organizers, as the excerpts below illustrate.

If you need technical help beforehand please ask your children or family members or failing that contact […].[SCVP FB 18 March 2020]In light of the coronavirus pandemic, Oshwal is trying to introduce a range of online events.We are trying out a new platform which hopefully will allow us to hold virtual events in the future. We hope that this will encourage young and old to get involved in an online Oshwal community. We need 10 to 20 volunteers to try out this platform. Register today for trial! […]Thank you[OAUK FB 21 March 2020, accessed on 10 march 2021]

Whereas the first excerpt echoes a generally held fear that older community members might not be able to access and thus benefit from the events organized online, the second clearly indicates a learning process on the part of the organizers. Depending on the available manpower, infrastructure, and technical knowhow, some organizations seem to have made the digital leap faster and higher than others. JVB London was very early in moving their regular activities online. After the announcement of the cancellation of all their events on Wednesday 11 March, they already had a virtual version of their regular Sunday program, including meditation and a talk, in place on 22 March. In other words, they only missed one Sunday. Young Jains UK also started early with their first Enriching Conversations session taking place on 25 March. Other organizations took a little longer to start organizing events in a virtual form.

Recurring events, such as Mahavir Foundation’s daily ārtī livestream, provide a great window into the experiments and learning process that underlie the crisis-induced digital turn. On 19 April, Mahavir Foundation hosted a live-stream on their YouTube channel titled “Derasar LIVE”23 (the series was renamed to Derasar Aarti Mangal Divo24 LIVE from 20 April). The video—a Zoom session streamed to YouTube—starts and we see a frontal view of the main shrine of the Kenton derāsar. There is some conversation in the background, followed by a single voice starting to chant. The singer then receives a phone call. We see the derāsar from different angles as the pujārī25 and his correspondent on the phone test out different set-ups. After some time, the audio is switched off, but the pujārī can be seen pacing through the temple and talking on the phone. This next livestream, on 20 April26, again starts with a phone call to double check the set-up. The camera is set to give a frontal view of the five main idols (closer up than in the previous video). From the sixth minute, we hear chanting. Although the person performing the rituals is mostly out of the camera shot, we can just see the waving of a ritual lamp in the left margin from the 20th minute (Figure 2). By the end of April, the camera position had been optimized to show the viewer more of the ārtī, and more qualitative sound had been added, with occasional bhakti songs being included.

Figure 2.

Screenshot from Derasar Aarti Mangal Divo LIVE on Mahavir Foundation’s YouTube channel, showing the derāsar’s main idols in the centre of the picture, and the pujārī waving a tray with a lighted lamp in the corner.

3.1. Untangling 2020′s Surge of Digital Activity

When we compare the level of social media activity (YouTube and Facebook) of a selection of London-based Jain organizations, it quickly becomes apparent that the pandemic has indeed resulted in a surge of activity. Technical and technological expertise in both organizations and individuals has grown throughout 2020, which has resulted in a broadening array of digital media and online activities as the year progressed. The initial period between March and May 2020 seems to have been most formative in the digital relocation process. Table 1 shows the number of Facebook posts between March and May 2020, and compares this with the number of posts in the same period in 2019. It also shows the number of videos uploaded to YouTube channels for the entire year 2020, and provides the total number of videos uploaded before 2020 for comparison.

Table 1.

Social media activity of London Jain organizations.

Looking at Facebook pages, a rise in the number of posts can be seen compared with the same period one year earlier for Oshwal Association, Mahavir Foundation, and Young Jains UK. The number of posts to the OAUK’s Facebook page more than quadrupled. Some organizations took a bit longer to move to social media communication and events. Navnat’s online activities started from the middle of April 2020 (see YouTube), but activity on their Facebook page only resumed on 3 June. Even for those organizations whose activity level on Facebook has remained roughly stable (such as JVB London, SCVP school), the type and themes of these posts tend to be different. There is, for example, a marked rise in the number of posts referencing mental welfare and messages pertaining to COVID-19-related information and charities. Unsurprisingly, announcements of and links to online events are also very prevalent in 2020. Indeed, again perhaps due to the severe limitations of word of mouth and physical billboards as ways of making activities and events known within the community, events are now often announced online multiple times, including on the day they will take place.

The online events themselves take place on different platforms. Facebook Live and YouTube streaming are the obvious choice for broadcasting lectures, rituals, yoga tutorials, and so on. The comment sections allow for a limited amount of interaction between viewers, and between organizers and participants. However, when more intense interaction is warranted, platforms like Zoom are more suitable. The importance of YouTube is compounded as Zoom recordings are often made available on this video-sharing platform, both as a livestream and for asynchronous viewing after the event. Looking at events organized within the London Jain community in 2020, we see that Facebook Live is not used often. Whereas JVB did use Facebook Live to broadcast (parts of) events in 2019, the Jain organizations under consideration here, including JVB, have clearly found their way to Zoom, YouTube, or the combination of those two. Zoom can be used when multi-directional communication and/or a degree of privacy is warranted, for example, in the case of Young Jains UK’s Enriching Conversations program or children’s activities. It also allows for the division of participants into smaller groups, which makes it suitable for teaching interactively. For more public events that require a degree of exchange and discussion, or an easy juxtaposition of a speaker and a presentation, a combination of Zoom and YouTube is often used. This is, for example, the case for JVB (London)’s lectures. Recorded events can also be incorporated into the organizations’ websites and Facebook pages. Some smaller-scale activities, such as the weekly gathering of the Bhakti Mandal29, are also conducted through WhatsApp.30

Which type of events are organized, and on which platforms, differs between organizations. The organizations discussed here tended to fall back on their core business. Those offering religious education continued providing this service. Classes for children are conducted by, for example, JVB-L, SCVP School, SDJA, and OAUK, generally as a password-protected Zoom session. Classes and lectures for adults are occasionally also streamed on YouTube and made available on websites and Facebook (Oshwal Association livestreams their adult pāṭhśālā, SCVP and JVB London also livestream their lectures).

Organizations that have a derāsar had to ensure that a caretaker was at hand to perform the necessary daily rites (cf. footnote 25 on pujārī). However, as places of worship had to remain closed throughout the spring of 2020, they also felt the need to enable their constituents to participate in some capacity. Mahavir Foundation decided early on to livestream ārtī from the Kenton derāsar every day, and more elaborate rituals every week. Oshwal Association did not do the same, but limited themselves to livestreams of rituals on Jain holy days and special occasions. Indeed, OAUK organized relatively few religious activities online in the first months, when their emphasis was more on social and mental health, providing entertainment, and offering opportunities for exercise. Religious activities, such as pāṭhśālā classes and occasionally rituals, were introduced into the program from the summer onward. Although the live-streamed rituals allow participants to do individual darśan of the images and idols in the derāsar from their own home, some communications, such as the directions given in the excerpts below, indicate an attempt to move beyond the purely visual and individual, and organize a communal practice based around live-streamed events, thus confirming the participants as an enduring community of praxis.

What to do:-At your own place, in front of Bhagwan Photo or Mangal Murti in your home derasar.Prayer

(As per above)Chaityavandan at 7.30 p.m.

God Simandarswami-Stavan, StutiIf you do not know or do not have book-you can do chaityavandan of any bhagwan.Arati and Divo at 7.50 p.m.

(You can use 1 divo for both arati and mangal divo) […][MF FB 16 April 2020, accessed on 22 February 2021]With everyone in lockdown over the last six weeks, we have organised a special celebration for the whole family from the comfort of your homes to lift the spirits! […] we (at SCVP London and Veerayatan UK) are continuing our classes virtually…. working around the current lockdown due to the corona outbreak.This Friday Dr Vinod Kapashi OBE, will be describing Mahavir Bhagwan’s birth. […] For this celebration, we would like everyone to dress up in their finest traditional clothes and would like you all to have the following items (if possible) so everyone can join in the celebration-little bell or thali-danko, some rice, Bhagwan’s idol or photo and flags (British, Indian, Jain).[SCVP FB Event 8 May 2020, accessed on 5 March 2021]

Organizations focusing on social events explored which type of activities could be conducted online. Whereas they usually have a range of activities including outings, walks, music, and lectures, Young Jains UK really focused on their Enriching Conversations series. Navnat and OA, who regularly organize a full-day program including lunch, yoga, lectures, religious music, a chance to visit the derāsar for ārtī or darśan, and so on, for a mostly senior crowd, had to evaluate which components could reasonably be moved online. Whereas yoga and lectures turned out to be easy to organize online, the social interaction, playing cards, and eating and singing together were less open to virtual relocation for a senior audience.

The crisis-induced digital relocation thus changed the type of activities organized within the community, abruptly ending communal lunches, children’s fun days, and multi-day meditation camps. On the other hand, it caused a rise in the numbers and popularity of specific types of events. The number of webinars and lectures rose, with some praising the “Zoom effect” for the increased availability of such activities (see below). Different types of yoga and musical evenings (often by musicians from India) were also noticeably prevalent during 2020, perhaps because they are both easily organized in a virtual form and have a positive impact on the physical and mental health of participants.

3.2. Virtual Audiences and Participation

We must assume that audiences for online activities are not a 1:1 rendition of the audiences that usually attended events in situ. Access to technology (in the form of the necessary devices, but also the required skills) and dislike of virtual formats may impede participation. On the other hand, informal conversations have indicated that ease of access and the absence of social pressure to stay until the end, participate in a certain way, or socialize afterwards may actually invite participation. It is as yet not possible to fully understand the exact changes in the demography of participants in Jain socio-religious events. What is clear is that participation in most virtual events is relatively high.

Keeping in mind public discussions on “Zoom fatigue”31, an examination of participation over time seems warranted. Looking at YouTube channels of London-based Jain organizations, a pattern of online participation emerges. After an initial peak in participation, the numbers dwindle somewhat, but remain stable at a relatively high level. This initial peak can be explained in part by curiosity of the community to explore the new format of events and a turn towards social and religious community as a reaction to the uncertainty and shock at the onset of the pandemic. However, especially looking at the number of views for events that were livestreamed on YouTube and remain available for asynchronous viewing, we must also keep in mind that the number of views is the sum of people who watched the event live and those who watched it later. The older the video, the more time it has had to accumulate such asynchronous views, some of which may even have been accidental. This may skew data by amplifying the initial peak and subsequent decline in participation. On the other hand, the number of people that participated through Zoom instead of watching the livestream or viewing the video afterwards is not included in these tallies.

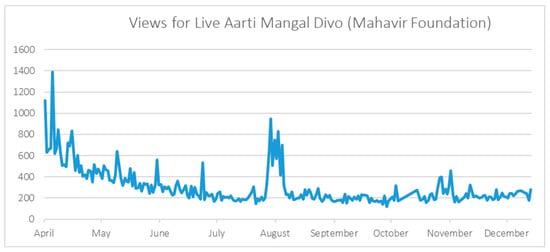

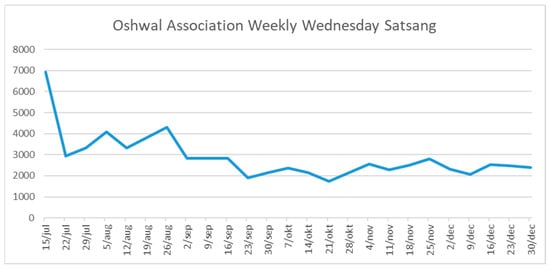

Interestingly, changes in COVID-19 restrictions—for example, the easing of restrictions over summer 2020, or the imposition of a new lockdown from 5 November 2020—do not seem to have impacted online participation in any significant way. This is a clear reflection of the fact that measures were never eased enough to make regular community gatherings and communal temple practice truly viable again. Festivals and holy days (see Dundas 2002, pp. 214–18) tend draw more people to Jain derāsars and activities in regular years, and the sudden relocation to online formats in 2020, has not changed this. Activities organized for festival days tend to draw large audiences. Furthermore, attendance for regular events around these periods exhibits a slight rise. The most important Jain festivals that occurred within the period under examination are Āyambil Oḷī (31 March–8 April 2020 and 22–31 October), Mahāvīr Janma Kalyāṇak (6 April), Paryūṣaṇ (15–22 August), Das Lakṣaṇ (23 August–1 September 2020), and Diwālī followed by Mahāvīr Nirvāṇa (14 and 15 November). Figure 3 below, showing the number of views for the daily “Aarti Mangal Divo” livestream on the Mahavir Foundation YouTube channel, illustrates these typical evolutions in participation in regular online events, including a slow decline from a very high participation rate during the first national lockdown, and clear spikes in participation around the festivals of Paryūṣaṇ and Diwālī/Mahāvīr Nirvāṇa. The number of views for the Oshwal Association “Weekly Satsang” livestreams shown in Figure 4 demonstrates a similar, albeit less pronounced pattern.

Figure 3.

Number of views for the Mahavir Foundation’s “Aarti Mangal Divo” livestream on YouTube.

Figure 4.

Number of views for the Oshwal Association UK’s “Weekly Wednesday Satsang” livestream on YouTube.

3.3. Celebrating Paryūṣaṇ 2020

The first Āyambil Oḷī and Mahāvīr Janma Kalyāṇak fell early in the pandemic, before digital relocation was complete. The Mahāvīr Janma Kalyāṇak celebrations by Young Jains UK on 6 April 2020 can be regarded as one of the first large-scale religious events organized in virtual form within the London Jain community. It was unique in scope and character at the time. However, in the months following, organizations and individuals gradually built up experience with online events. By early summer, London’s Jain organizations planned and organized a diverse program of Paryūṣaṇ celebrations online. This yearly eight-day festival observed by Śvetāmbar Jains centers around repentance and forgiveness. During this time, devout Jains typically take vows of fasting and spend extra time on religious study. Although, as in most Jain festivals, individual restraint and effort and a serious mind-set are paramount (Dundas 2002, p. 215), the festival also marks a very social and sociable period in the Jain calendar: many people spend more time at the temple, a diverse range of activities is organized at Jain centers, and large get-togethers at the temple hall and at private residences mark especially the first and last days of the festival. Members of the community do daily pratikramaṇ (ritual of repentance), and Jain centers everywhere invite speakers to deliver daily lectures. In India, these speakers are often sādhūs (Jain monks) or sādhvīs (Jain nuns). In a diaspora setting, recorded or livestreamed sermons by ascetics are an option, but lectures by pandits (mostly from India, but also from the USA and elsewhere) are usually preferred, as they can travel to deliver their lectures in situ.32

For Paryūṣaṇ 2020, the core events of the festival—lectures/study and pratikramaṇ—were relocated online. In addition to these, there were considerably more livestreams of pūjā33 and ārtī, and the nightly bhakti/bhāvnā34 musical programs were especially popular. In the description of the activities below, the large amount of overseas contributors is noteworthy. OAUK, Navnat Vanik Association, and Mahavir Foundation presented comparable full-day programs to their members. OAUK streamed four events on their YouTube channel each day of Paryuṣaṇ: morning pūjā and ārtī; a combination of bhakti/bhāvnā and satsaṅg (group study) conducted by their own pujārī Jayeshbhai Shah; pratikramaṇ; and evening bhakti music by various musicians in the United Kingdom, India, and Kenya. Navnat Vanik Association put together a similar full-day program with pravacans (sermons) by Jain sādhvī Param Sambodhiji Mahasatiji from India in the morning, followed by storytelling by pandit Paritosh Shah (USA), as well as Sthānakvāsī, Derāvāsī, and English pratikramaṇ in the afternoon. Bhakti/bhāvnā by a group in India closed the day’s program in the evenings. With the exception of English pratikramaṇ, all these events were conducted on Zoom and streamed to the Navnat Vanik Association’s YouTube channel. Mahavir Foundation streamed a similar set of events daily, with live sermons by sādhū JP Guruji, different bhāv pūjās by pandit Nikunj Guruji, and daily bhakti/bhāvnā by Harshil and Moxit—all of whom performed from India. Table 2 shows the participation numbers for these three large paryuṣan programs.

Table 2.

Number of views for the three largest Paryūṣaṇ programs as of 15 March 2020.

Other paryuṣan celebrations included SCVP’s special children’s classes and English pratikramaṇ (Zoom only), which drew between 500 and 600 participating families daily. JVB London organized classes and pratikramaṇ in English and Hindi especially for children. JainNetwork streamed recorded paryuṣaṇ pravachans by Śvetāmbar monk Ratnasundersuri Maharaj from Mumbai, and bhakti/bhāvnā every day. The sermons got around 45 views, whereas again, the bhakti program was clearly the most popular, drawing 170 views on the first day of the festival.

The numbers given in Table 2 do not include members that joined on Zoom, nor do they take into account multiple family members participating or watching events on the same screen. Keeping in mind that the London Jain community consists of some 25,000 Jains, we must conclude that the 2020 virtual edition of this religious festival was a success, as organizers succeeded in reaching out and motivating a significant proportion of Jains to participate in some paryūṣaṇ event or other.

Traditionally, paryūṣaṇ is followed by a chaitya paripāṭi (literally, ‘a succession of shrines’), a community pilgrimage (or yātrā) to a nearby temple or temples. Both Oshwal Association and Mahavir Foundation managed to organize a virtual alternative for the traditional community pilgrimage. Oshwal Association’s yātrā was streamed on 30 September. The trip starts and ends at the Oshwal Centre and Temple at Potters Bar. In true bhāv yātrā37 style, Jayeshbhai describes how participants make their way to the airport, board their flight, transfer to a bus upon arrival, and drive to the temple in Nairobi, where members of the local Oshwal Association receive them with song and speeches before guiding them to the temple in the Visa Oshwal Centre. Next, they travel back to the United Kingdom to visit the temples in Manchester, Leicester, and the Kenton temple in London.

Mahavir Foundation streamed their yātrā on 6 September, starting at their own temple in Kenton, then moving to Jain temples in Dubai, Lonavala (India), Antwerp (Belgium), and New Jersey (USA). Although this video does not display the same bhāv yātrā like narration, it does refer back to the earlier paryūṣaṇ celebrations, as music and commentary are provided by Harshil and Moxit (Mumbai), and short speeches by JP Guruji (then in Lonavala).

4. In Conclusions: Implications of the 2020 Digital Leap in the London Jain Diaspora

4.1. Accessibility and Archives

The sections above sought to provide an in-depth description of how the hub of London Jain activity found its way online in 2020. This digital turn was crisis-induced; it has been a development that might not have taken place were it not for the COVID-19 pandemic. This is corroborated by the sparsity of online-only activities and events in this same community preceding the pandemic, and the relatively negative appraisal of virtual religious events that was illuminated by previous research (Vekemans and Vandevelde 2018). However, as virtual events have become a lived reality in the past year, a number of positive aspects and implications of the rise in online events have been noted. Despite worries regarding the generational digital divide, many of these positive effects pertain to access.

Although proficiency with technology is a prerequisite that may have excluded some from the wave of online events (e.g., some seniors), indications are that, for others, the current digital turn actually made it easier to participate. Issues of mobility and to a certain extent geography that would otherwise inhibit participation are largely bypassed when events are organized online. This can be viewed on a local scale, where events usually organized at the Oshwal Centre in Potter’s Bar in the far north of London (only accessible by car) drew more participants from all over the London area and beyond. The same effect is also visible on a global scale. Although time differences can still impede participation in some events, it is now not exceptional to see Jains in Mumbai, Manchester, Melbourne, or Mombasa joining in for an activity by a London-based organization, as the excerpts below illustrate.

Honoured to have been a part of this wonderful celebration. All 300 helped make history of first YJ Mahavir Janma Kalyanak online celebrations. Was lovely to have so many people re-involved in the community and make something special for the community. Heartening to have people from USA and Kenya in addition to the UK.[Comment on post after Mahavir Jayanti celebrations on YJUK Facebook 7 April 2020, accessed on 12 March 2021]Thoroughly enjoyed the Adinath Varshitap Celebration. Very well conducted by Jayeshbhai and the bhajans sang by Vijaybhai Doshi were so melodious and his tone in still ringing in my ear. Ashish congratulations for making use of modern technology. People all over the world could participate in OAUK Online Activities. Thanks to the whole team for giving their valuable time to the community.[Comment on online Akshay Tritya announcement on OAUK FB 26 April 2020, accessed on 10 March 2021]

This global attendance at locally organized events illustrates how the Internet complicates geographic locationality, at times reproducing hyper-local practices and sensibilities, at other times utterly geographically untethered. Some of the factors that divide Jains into subgroups based on gender, language, sect, geographic location, and even migration history become less consequential (or at least easier to circumnavigate) when activities and events are removed from their in situ localization and transported to the online realm, opening up possibilities of global participation and potentially strengthening ideas of a unified Jain community. This is further enforced by the way cooperation with organizations and individuals overseas is much more straightforward in a digital format. The case study discussed above, in which online paryūṣaṇ activities and yātrās were examined, illustrates just how international these local events have become. This is not just true for large events; SCVP-school, a large pāṭhśālā affiliate of India-based Veerayatan, posted their schedule for online classes, which included the regular London-based teachers, but also classes taught by teachers in India (5:30 hours’ time difference) and Kenya (3:00 hours’ time difference). Throughout 2020, lectures and music performances by teachers and artists in India and the United States were quite prevalently organized by most organizations included in this research. For Jains living in places with a large and active Jain community (such as London), the sharp rise in online and thus to an extent non-geography-dependent events adds to an already full schedule. However, Jains living in more remote locations in fact have significantly more access to Jain activities owing to the digital relocation caused by the pandemic.

Any limitations to participation caused by infrastructural constraints have also largely been overcome with the move to online activities. The number of participants in some online activities exceeds the number of people that would and could attend such activities when organized traditionally. Oshwal Association has the largest hall of all currently active Jain organizations. It seats up to 500 people. For very large events, the community has occasionally rented banquet halls; the largest such venue, at Harrow Leisure Centre, accommodates just over 2000 people. The paryūṣaṇ bhakti/bhāvnā evening on 19 August, livestreamed on the Oshwal UK YouTube channel, was watched by more than 9500 people. Mahavir Foundation has a number of smaller rooms available. However, they would not be able to accommodate the 900+ people that watched the Ladies Wing Rakhi Making workshop, which streamed on 26 July. Such examples abound. Similar patterns of increased engagement with religious activities when they were moved online were noted for Catholic Easter liturgies organized by the Vatican (Glatz 2020) and Mass attendance in Wales (Parish 2020).

Whereas the paragraphs above dealt with physical access, geography, and mobility, anachronous access to past events has also dramatically increased with the 2020 digital turn. This unintended perk of the current digital turn has led to great enthusiasm, especially in those for whom study is an important part of religious practice.

The Zoom effect has been phenomenal. A plethora of online talks!!![R., Adult pāṭhśālā teacher]

The plethora of lectures and seminars that are made available online contribute to a growing—albeit largely unstructured—repository of knowledge on different aspects of Jainism emerging primarily on YouTube. Some indicate that such lectures are now easier to follow and use as study material. Not only can they be rewound and watched multiple times, one of my respondents indicated that she found it easier to focus on the speaker’s arguments as she felt there were less diversions when taking classes in an online format. Seen from this perspective, the limited social interaction between participants in online formats can be a positive point.

4.2. Awards and Afterthoughts

Even if we allow for the positive aspects of the digital turn just described, it is safe to say that the COVID-19 pandemic and its concomitant restrictions have taken a heavy toll on social and community life. No outings, no communal meals, and no school fairs. No sitting shoulder to shoulder for a religious class. No crowding into a temple hall to participate in pūjā or other rituals. No gossip on the bus towards Oshwal Association’s Sunday program. No busy hallway full of shoes and children at the entrance of the Kenton derāsar. Even so, Jains in London have cooked together, made handicrafts, competed and voted in talent shows, and sang songs. Thanks to the digital leap undertaken by Jains and their community organizations, community life has not come to a complete halt, and help and support were mobilized for those who needed it. Organizations tried to keep their members stuck at home healthy and occupied through new activities (such as workshops, virtual rituals, and music evenings) and a virtual version of their regular activities (meditation, yoga, lectures, and classes). Many are impressed by what has been achieved in a relatively short timeframe. Indeed, OneJAIN gave out COVID Response Awards in recognition of the work done by Jain individuals and organizations during the crisis.

For the first time, the Jain community had constituted the OneJAIN COVID19 Excellence in Community Service award to recognise the incredible work that the organisations have been doing to support the community during the crisis. Examples included providing community activities over Zoom, including meditation, yoga, prayers, musical events and business briefings. Other examples were around supporting the elderly and vulnerable through the provision of food and shopping, and aiding the NHS and frontline staff with PPE and hot meals.[https://www.onejainuk.org/, accessed on 8 March 2021]

While digital media have been present in different ways in the religious lives of many, the degree to which organizations and individual practitioners have taken to digital media for socio-religious praxis in the current situation prompts the question of whether this crisis-induced digital turn will have lingering effects, especially given the tepid reception of online religious events described in previous research (Vekemans and Vandevelde 2018; Vekemans 2019a). It seems very plausible that many Jains will want to revert back to the in situ practices from before the COVID-19 pandemic. In line with previous research that prompted a reassessment of ritual in a way that emphasises flexibility and resilience (e.g., Brosius and Polit 2011; Langer et al. 2006), the current crisis has shown that it is possible to stream Jain rituals. It has shown that it is even possible to retain some version of communal practice online (e.g., by providing instructions regarding the timing and choice of mantras, dress codes, and so on). However, most temple-going Jains will in all probability argue that physical proximity to a consecrated idol in a dedicated temple space cannot be replicated fully online. A yearning to rekindle previously established social ties is another important reason Jains wish to return to in situ practice as usual. Although online events arguably maintain some social cohesion within the community, the type and intensity of interaction possible during online events is scarcely an equivalent alternative to the myriad of social interactions taking place during and in the margins of in situ events, as both the attendees and the available modes of communications differ significantly from pre-COVID events.

However, even while longing for a return to normalcy, many individual community members were grateful for the possibilities of digital media, and amazed at the relative ease in which it had become central to their spiritual practice within the context of the pandemic. This conclusion resonates in Tilak Parekh’s work on the digital presence of the Neasden Temple (Parekh 2020). As organizations are motivated by positive experiences with transnational cooperation, the chance to engage with larger global audiences, and the opportunity to facilitate access for local members, the future of Jain events may be far more hybrid then was previously considered possible. The long-term effects of the crisis-induced digital turn discussed in this paper will only become evident in the coming months and years. Further research, backed by more diverse data than currently available, will have to assess to what extent the changed relationship between religious organization and digital media, and the concomitant blending of local and global dimensions brought about by the pandemic, will have resulted in permanent changes.

Funding

This research was funded by Research Foundation—Flanders (FWO), grant 12T7320N.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Commission of the Faculty of Arts and Philosophy at Ghent University, Belgium (10 September 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The digital materials used in this study are publicly available (cf. primary sources). Access to data derived from ethnographic work are restricted for reasons of privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | When it was started in 1996, SCVP (Shree Chandana Vidyapeeth) was the only formal Jain pāṭhśālā in London. It was organized at the instigation of Ācārya Chandana-jī Mahārāj and her disciple sādhvī Shilapi jī, who also set up Veerayatan, a non-profit charity organization offering education and conducting other types of charity works in India. SCVP School offers adult classes for beginners and advanced students, and five levels of children’s pāṭhśālā classes. |

| 2 | OAUK, Oshwal Association UK, was the first Jain organization in the United Kingdom, formally started in 1968. It is by far the largest Jain organization in the United Kingdom by the number of members, activities, and infrastructure. Their temple in Potters Bar (North of London) was inaugurated in 2005, and remains the only Jain temple in traditional architectural style in the United Kingdom (Shah et al. 2012, pp. 77–78). OAUK organizes a variety of religious and social activities for the Oshwal Community. |

| 3 | SDJA, Shree Digamber Jain Association, was formalized in 1989, and the current temple in Harrow was inaugurated in 2006. Their practice is based around the teachings of Kāñjī Svāmī, a twentieth century Jain reformer who revived the Digambar tradition in Gujarat (Dundas 2002, pp. 265–71), and gained a significant following in East Africa. |

| 4 | Jain Vishva Bharati (JVB) is an organization affiliated to Jain Vishva Bharati Institute (deemed University) in Ladnun (Rajasthan). The organization was set up in the philosophy of the Śvētāmbar Terāpanth subtradition. JVB’s centres abroad (Orlando, Houston, New Jersey, and London) consist of teams of two samaṇīs that are sent out to teach and serve the spiritual needs of a diasporic Jain community and any other interested parties that may share its location. In London, the samaṇīs conduct a weekly Sunday program including gyānśālā classes for children and prekṣā meditation and a lecture for adults. Since the opening of their own Jain World Peace Centre in Harrow in 2017, activities are mostly organized there. |

| 5 | Mahavir Foundation was established and registered as a charity in 1987, as an inclusive alternative to the more community-specific focus of OAUK and Navnat Vanik Organization. Its base of operations consists of three residential properties just outside of Kingsbury, bought in 1995. More commonly known as the Kenton Derāsar, these now house a temple, but also different areas for classes and discourses. |

| 6 | JainNetwork was established as a registered charity in 2007. Soon after, the organization acquired a piece of land with old industrial buildings in the Colindale area, where activities have been organized since 2010. However, this existent infrastructure has gradually been demolished to build an elaborate new Jain Centre. |

| 7 | Young Jains UK was founded in 1987 as an explicitly non-sectarian organisation that encourages the discussion and exploration of Jain philosophy, spirituality, and its practical importance to life (https://youngjains.org.uk/category/about-us, accessed on 20 March 2021). |

| 8 | A Tīrthaṅkara (lit. ‘fordmaker.’) is a central figure in Jainism, who has overcome all spiritual obstacles, attained liberation, and spread the teachings. |

| 9 | https://www.facebook.com/events/2822074427840346 (accessed on 12 March 2021). |

| 10 | Interestingly, the degree to which Jains in the diaspora are open to the idea of online events and rituals seems to be dependent on the geographic and demographic lay-out of their community. The vast majority of the Jain organizations discussed in this article have at least a basic website, and many also have a social media presence. However, these websites and social media pages tend to function as billboards, giving visitors some information about the organization and its activities, and guiding them towards activities. Before the pandemic, in situ events were the norm in London. Perhaps owing to the relative density of the Jain population and the array of Jain organizations active in the same area, organizers did not feel compelled to offer hybrid events, and the demand for online events was generally low. Although recordings of lectures and (parts of) large events were occasionally shared on social media, this was mostly done after the in situ event had taken place, and not as a hybrid live-streamed event. Online events, such as online lectures, but also live-streams of temples and so on, are more common in Jain organizations that cater to Jain communities that are more geographically spread out (such as in many places in the USA, where one centre often caters to a large urban centre, or indeed an entire state). See Vekemans 2019a for a further discussion of the impact of population density on digital practices. |

| 11 | Data on government restrictions are taken from the Institute for Government website (https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/timeline-lockdown-web.pdf, accessed on 10 March 2021.) |

| 12 | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LCHmiPieMFM&t=978s (accessed on 10 May 2021). |

| 13 | This excerpt makes a distinction between private worship and communal practices usually conducted at the temple. Private worship here seems to refer to darśan (visual contemplation of, e.g., an idol), whereas pūjā (ritual in which different substances are offered to, e.g., an idol), abhiṣek (ritual in which an idol is anointed with different liquids), and lectures are identified as communal modes of practice. It is worth noting that this distinction is one of habit and convenience under the current circumstances. Although members of the SDJA usually perform abhiṣek in a group, this is not mandatory, and such rituals can also be performed individually. However, even when performed individually, these rituals take more time and entail more direct contact with vessels, idols, and so on, which would in turn require more administrative follow-up (e.g., a system of time-slots and prior reservations) and decontamination of utensils after use. |

| 14 | Lit. ‘glancing, beholding’. A form of visual worship or contemplation. Usually, this is done in front of a statue of a tīrthaṅkar, but it may also be done for (images of) lay or ascetic gurus or places of pilgrimage. |

| 15 | https://www.bbc.com/news/health-54476259 (accessed on 10 May 2021). |

| 16 | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gCQARJUx8qs (accessed on 10 May 2021). |

| 17 | OneJAIN was launched in 2014, after a meeting of all Jain organizations, where it was agreed that a single voice was needed to better represent the community in government and interfaith matters. It is a branch or project connected to the Institute of Jainology (IoJ). |

| 18 | https://www.onejainuk.org/covid (accessed on 8 March 2021). |

| 19 | https://www.jvblondon.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/news-letter-jvb-JUNE-2020.pdf, p. 19. (accessed on 10 May 2021). |

| 20 | Jain International Trade Organization is a worldwide organization of Jain businessmen, industrialists, knowledge workers, and professionals, with a local in the United Kingdom (https://jito.org/uk, accessed 8 March 2021). |

| 21 | On the 25 March, Young Jains UK started a series of interactive online sessions titled ‘Enriching Conversations’. The aim of this recurring event was to help participants stay connected, share insights, and remain centered (https://www.facebook.com/events/509419783081123, accessed 10 March 2021). The first session was themed ‘Finding Calm in the Chaos’. The conversations started twice-weekly, but the frequency dropped to once a week and then once a month as the year progressed. |

| 22 | Navnat Vanik Association was founded in 1970 and represents about 3500 members, including both Jains and Hindus. Today, the main centre of Navnat in London is the Navnat Centre in Hayes. |

| 23 | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_oTMuxVpUSc (accessed 10 May 2021). |

| 24 | Maṅgal dīvo is a ritual act in which a single lamp is lighted as a symbol for the burning away of bad karma. It is often performed as part of ārtī rituals. Ārtī is a simple Jain ritual of holding a small lighted lamp (dīyā). Usually, this is done in front of an image of a tīrthaṅkar, but it may also be done for (images of) lay or ascetic gurus, places of pilgrimage, ancestors, and so on. |

| 25 | Ritual assistant employed to facilitate devotees wanting to do rituals in a Jain temple. The pujārī is often also the caretaker of the temple. These men are themselves traditionally seldom Jainsm but mostly Vaiṣṇava Hindus trained in the technical aspects of different Jain rituals. As such, their role in the Jain temples and the organizations around them is almost entirely logistical. In diaspora communities, the way the care of temples is organized differs. Some temples engage Hindu pujārīs (e.g., Antwerp, Detroit), but most places in London engage Jain pandits and/or community members for temple upkeep and ritual obligations. It is the pujārī who makes sure the necessary daily rituals are performed for any consecrated idols. In cases where regular devotees are not at hand to do this (such as under lockdown), these rituals are performed by the pujārī himself. |

| 26 | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J8zrcpgNPdc&t=1779s (accessed on 10 May 2021). |

| 27 | Activity resumed in June 2020, with a regular schedule of online events. |

| 28 | The Institute of Jainology (IoJ) was registered as a charitable trust in 1986, informed by a growing need to represent the Jain community in international, national, and local politics and society. Although IoJ maintains an office in India, where it has, for example, supported the efforts to obtain minority status for Jains, most of their work is international or United Kingdom-based. Since its inception, IoJ has been active in interfaith and political lobbying, as well as attempting to make Jainism more known and visible within the larger community. Since 2014, they are more or less sanctioned to speak for the U.K. Jain community as a whole when it comes to representation in local and national politics, under the OneJAIN project. |

| 29 | Bhakti Mandal is a group that meets weekly for devotional music and songs. They occasionally perform at different organizations’ events too. |

| 30 | It is likely that many smaller events organized on WhatsApp or exclusively on Zoom stay under the radar of this research. If they are not advertised on publicly accessible websites or social media channels, the only way to learn about them is by word of mouth or through members-only chat groups or mailing lists. |

| 31 | https://hbr.org/2020/04/how-to-combat-zoom-fatigue (accessed on 10 May 2021). |

| 32 | Initiated Jain monks and nuns are generally not allowed to travel by mechanical means, making it virtually impossible for them to reach diasporic communities outside the South-Asian subcontinent. Some Jain sects have reinterpreted this rule and do allow travel by fully-initiated ascetics (e.g., Śvētāmbar Sthānakvāsī Amarmuni Sampradāy—best known for the charitable organization Veerayatan to which SCVP School in London is affiliated) or a special group of semi-initiated ascetics (Śvētāmbar Terāpanth samaṇ and samaṇīs—such as the nuns running JVB London). However, the vast majority of Jain ascetic groups do not travel outside South-Asia. Pandits are best described as religious teachers. They are knowledgeable and respected, but still part of the lay community. Most diaspora organizations prefer to invite a pandit for lectures, as these men and women can come deliver their lectures in situ. In 2020, as in situ lectures were not possible to begin with, lectures by ascetics in India seemed more popular. |

| 33 | Pūjā denotes a ritual presenting of offerings. When this ritual uses material components, it is called dravya pūjā and performed in a temple or shrine, usually in front of an image of a tīrthaṅkar. However, it also has a mental, internal version called bhāv pūjā. |

| 34 | Bhakti means devotion, and is most often used to refer to devotional music and singing. Bhāvnā denotes spiritual contemplation. The bhakti/bhāvnā evenings that took place during paryūṣaṇ 2020 were thus programs mixing devotional music with short contemplations on Jain values, concepts, and figures. |

| 35 | The number given here is the sum of the views for the deravāsi pratikramaṇ and the views for the sthānakvāsi pratikramaṇ on the Navnat Vanik Association’s YouTube channel. English pratikramaṇ was also organized, but not livestreamed on YouTube. |

| 36 | On the seventh day of the program, the Derāvāsī pratikramaṇ was livestreamed separately. The Sthānakvāsī Pratikramaṇ was streamed in one go with the evening’s bhakti program. |

| 37 | Bhāv yātrā is the practice of making a mental journey, usually a pilgrimage. Instead of physically travelling to Jain sites such as Palitana (Gujarat), devotees make use of paintings and other images of the place of pilgrimage to go through the stages of the pilgrimage in their mind. This can be done individually, but on occasion, this is done communally, in which case it is common practice that a pandit or community member describes the pilgrimage and the physical and devotional impressions of the travelers to the participants (see Luithle-Hardenberg 2015). |

Primary Sources

BBC News Website. https://www.bbc.com/news/health-54476259 (accessed 10 May 2021)

Institute for Government Website. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/timeline-lockdown-web.pdf (accessed 10 March 2021)

Institute of Jainology Website. https://www.jainology.org/ (accessed 11 May 2021)

Jain Vishva Bharati London Facebook Page. https://www.facebook.com/JainVishvaBharatiLondon (accessed 10 May 2021)

Jain Vishva Bharati London Website. JVB London. https://www.jvblondon.org/ (accessed 10 May 2021)

Jain Vishva Bharati London YouTube Channel. https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC6kYQigwQQ_aUtPshD7E5bA (accessed 10 May 2021)

JainNetwork Facebook Page. https://www.facebook.com/JainCentreLondon (accessed 10 May 2021)

JainNetwork YouTube Channel. https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCirz_XeWXcxa_hW4LO15yyA (accessed 10 May 2021)

Jainworld Website. www.Jainworld.com (accessed 10 May 2021)

JITO UK Website. https://jito.org/uk (accessed 8 March 2021)

Mahavir Foundation Facebook Page. https://www.facebook.com/mahavirfoundation.org (accessed 22 February 2021)

Mahavir Foundation Website. https://mahavirfoundation.com/ (accessed 10 May 2021)

Mahavir Foundation YouTube Channel. https://www.youtube.com/channel/UClheaTzT6GsvPMp80ixqNeg (accessed 10 May 2021)

Navnat Vanik Association Facebook Page. https://www.facebook.com/NavnatCentre (accessed 10 May 2021)

Navnat Vanik Association Website. https://www.navnat.com/ (accessed 10 May 2021)

Navnat Vanik Association YouTube Channel. https://www.youtube.com/user/NavnatWebmaster (accessed 10 May 2021)

OneJAIN Website. https://www.onejainuk.org/ (accessed 8 March 2021)

Oshwal Association UK Facebook Page. https://www.facebook.com/oshwaluk (accessed 10 March 2021)

Oshwal Association UK Website. Oshwal Association. https://www.oshwal.org.uk/ (accessed 10 May 2021)

Oshwal Association UK YouTube Channel. https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCGbMPrIV6rRTZkVhAme8gng (accessed 10 May 2021)

Religious Matters in an Entangled World research project. 2020. Corona dossier blog. https://religiousmatters.nl/dossier-corona1/ (accessed 10 May 2021)

SCVP School Facebook Page. https://www.facebook.com/SCVPLondon (accessed 5 March 2021)

SCVP School Website. https://scvp.info/site/ (accessed 10 May 2021)

SCVP School YouTube Channel. https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCQkG-Od3nOPCyZ-kpt1zxMQ (accessed 10 May 2021)

SDJA. Homepage ‘Digamber Jains London’. http://sdja.co.uk/blog/ (accessed 8 March 2021)

Young Jains UK Facebook Page. https://www.facebook.com/youngjainsuk (accessed 12 March 2021)

Young Jains UK Website. https://youngjains.org.uk (accessed 20 March 2021)

References

- Al-Astewani, Amin. 2021. To Open or Close? COVID-19, Mosques and the Role of Religious Authority within the British Muslim Community: A Socio-Legal Analysis. Religions 12: 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, Murali, ed. 2018. Digital Hinduism: Dharma and Discourse in the Age of New Media. London: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brosius, Christiane, and Karin Polit. 2011. Introducing Media Rituals and Ritual Media. In Reflexivity, Media, and Virtuality (Ritual Dynamics and the Science of Ritual IV). Edited by Axel Michaels. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 267–75. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidi A. 2005. Exploring Religious Community Online. Bern: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidi A., ed. 2013. Digital Religion: Understanding Religious Practice in New Media Worlds. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]