Abstract

Based on Huber’s centrality of religiosity concept, a non-experimental research project was designed in a group of 178 women and 72 men, voluntary participants in online studies, quarantined at home during the first weeks (the first wave) of the pandemic, to determine whether and to what extent religiosity, understood as a multidimensional construct, was a predictor of the worsening of PTSD and depression symptoms in the conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic. The study made use of CRS Huber’s scale to study the centrality of religiosity, Spitzer’s PHQ-9 to determine the severity of depression, and Weiss and Marmar’s IES-R to measure the symptoms of PTSD. Our study, which provided interesting and non-obvious insights into the relationship between the studied variables, did not fully explain the protective nature of religiosity in dealing with pandemic stress. Out of five components of religiosity understood in accordance with Huber’s concept (interest in religious issues, religious beliefs, prayer, religious experience, and cult), two turned out to contribute to modifications in the severity of psychopathological reactions of the respondents to stress caused by the pandemic during its first wave. A protective role was played by prayer, which inhibited the worsening of PTSD symptoms, whereas religious experience aggravated them. This means that in order to interpret the effect of religiosity on the mental functioning of the respondents in a time of crisis (the COVID-19 pandemic), we should not try to explain this effect in a simple and linear way, because religious life may not only bring security and solace, but also be a source of stress and an inner struggle.

1. Introduction

“It is you alone who are to be feared. Who can stand before you when you are angry?From heaven you pronounced judgement, and the land feared and was quiet.”(Psalm 76:8–9)

The pandemic we have been dealing with everywhere around the world since the beginning of 2020 seems to be a stressful situation that leads to numerous psychopathological and neuropsychiatric symptoms. The results of clinical analyses correspond with each other in various countries, pointing to high rates of mental problems, such as acute post-traumatic stress and depression among people at risk of being traumatized by the COVID-19 pandemic (Babicki et al. 2021; Brooks et al. 2020; Cenat et al. 2020; Choi et al. 2020; Consolo et al. 2020; Fekih-Romdhane et al. 2020; Gualano et al. 2020; Lee 2020; Luo et al. 2020; 89; 96; 112; 113). An additional emotional burden may also be caused by recurring opinions that the pandemic is “a punishment upon the sinful” (Isiko 2020; http://idziemy.pl/wiara/epidemia-kara-boza-/63557 (accessed on 22 February 2021); https://deon.pl/kosciol/ksiadz-na-mszy-koronawirus-to-kara-za-homoseksualizm-i-aborcje-jest-reakcja-prymasa,779805 (accessed on 22 February 2021)). In relation to suggestions expressed in literature as to the relevance of studying both patients, i.e., public service workers (health care workers, social service workers, and members of uniformed services, i.e., people who take care of others, which are particularly important in times of crisis), and the healthy population, which is also at a high risk of experiencing pandemic stress (Chow et al. 2021; 105), we decided to study the latter group, looking for potential protective factors (mental resources) in dealing with pandemic stress. We chose the religiosity factor and the position of religiosity among other personal constructs of an individual, because previous studies have shown that religiosity, understood as a system of personal religious constructs (Huber 2003), seems to be an immunogenic factor, which is not always very strong, but is usually regularly reported in the case of more efficient dealing with various types of burdens (Koenig 2012; Koenig et al. 2012). This is also confirmed by the results of studies on a positive role of religiosity in dealing with stress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic (Galea et al. 2020; Lucchetti et al. 2020; Modell and Kardia 2020; Pirutinsky et al. 2020; 111), even though the essence of this stress was not fully explained.

1.1. The Purpose of the Study

The presented empirical studies focus on analyzing the relationship between religiosity and health, suggesting that it has an immunogenic character. The main purpose of this study was to determine the relationship between religiosity and an increase in psychopathological reactions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in a sample made up of healthy people during the lockdown time (Poland). The analysis covered two types of psychopathological reactions, depression and PTSD (intrusions, avoidance, and hyperarousal), and five factors of religiosity (interest in religious issues, religious beliefs, religious experience, prayer, and cult, which are measures of the centrality of religiosity), based on Huber’s concept (Huber 2003). The study tested the hypothesis that religiosity understood as a multidimensional cognitive–emotional–behavioral construct is a predictor of an increase in psychopathological reactions, such as PTSD and depression, associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

1.2. Background

More and more data point to religiosity as a predictor of mental health (which mainly alleviates anxiety and depression), suggesting that it serves as a factor of personal resilience. It is an element of individual identity, enables social networking, and is an important source of individual and social resources, which places it among resources that are related to the effectiveness of coping with stress and other psychological problems. Moreover, a growing body of research is linking it to well-being (Huber 2007; Hayward and Krause 2014; Koenig 2012; 106).

For the purpose of this paper, we adopted Huber’s psychological concept of religiosity, understood as a system of personal religious constructs—global centrality and five traditional structural dimensions of religiosity, religious beliefs, prayer, religious experience, cult, and interest in religious issues (114), and made an attempt to empirically rationalize them, which was possible thanks to the tool devised by Huber. Religiosity understood as a psychological construct is treated equally to other personal constructs, and the same properties are ascribed to it. In Huber’s view, religiosity is like a prism through which a person perceives reality and uses this perception to shape their experiences and behavior. The concept is based on the perception of elements of the surrounding world (ideas, people, and events) within the framework of religious meanings. A system of personal religious constructs is a psychological basis for a religious perception and experience of the world. The experiences and actions of an individual, understood as a function of the system of religious constructs, depend on the position of this construct in the system of all personal constructs and on its content. The closer religious issues are to the center of the system, the more strongly they affect the thoughts, emotions, and behavior of an individual (Krok 2016).

Huber’s model (2003) is a synthesis of two approaches to religiosity: psychological—developed by Allport (Allport and Ross 1967), and sociological—developed by Glock and Stark (1965), which led to the development of a model useful from the viewpoint of religiosity in its phenomenological complexity, cognitive (religious beliefs and knowledge), emotional (religious feelings), and behavioral (religious practices and their consequences). In this way, it includes a proposal to treat religiosity as a multidimensional construct. By combining the views of Allport and Glock, it captures the motivational status of religiosity and shows it through its structural dimensions. The theoretical foundation of this synthesis is the concept of a system of religious constructs. The author assumed that:

- Five dimensions of religiosity reflect a representative spectrum of potential uniquely religious activities in the system of personal religious constructs.

- The more often a system of religious constructs is activated, the more likely it is to be in the center of a person’s personality.

- The centrality of the religious construct system implies a probability that it functions autonomously in the configuration of other personal construct systems.

- The functional autonomy of a system of religious constructs implies a probability of an inner religious motivation (115; 114).

To sum up the role of religiosity in maintaining health in various areas, it can be said that religiosity (1) makes it possible for an individual to adopt broader perspectives on life; (2) provides energy and the potential to use the capabilities and resources of an individual more fully; (3) serves as a getaway from stress, which turns it into a buffer whose absence could lead to mental disorders; (4) supports the socialization process, for example by restricting behavior that could indicate social maladjustment; and (5) can serve as an outlet for symptoms of mental disorders observed by a given person (109). The presented content may serve as the basis for justifying a study on the protective role of religiosity in dealing with the symptoms of PTSD and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

Studies were conducted in the first weeks of complete lockdown during the first wave of the pandemic. The tested sample of 178 women (71.2%, MAGE = 36.76, SD = 13.31) and 72 men (28.8%, MAGE = 41.18, SD = 13.51) aged from 18 to 71 was chosen via the Internet, using the snowball sampling method, which is a procedure admissible in exploratory studies (Babbie 2016). The research project presented in this article was exploratory, because its main aim was not to test a theory, but to search for new relationships between the studied variables. The analysis of differences in basic socio-demographic characteristics does not distinguish between male and female respondents (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic Data.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Impact Event Scale-Revised (IES-R Scale)

The Polish version of the IES-R by Weiss and Marmar, adapted by Juczyński and Ogińska-Bulik (2009), was used to measure PTSD symptoms. It is assessed on a five-point Likert scale (0–4). Twenty-two statements are used to determine the current and subjective feeling of discomfort related to a specific event that happened in the past. It covers three dimensions of PTSD: (1) intrusions, which stand for recurring images, dreams, thoughts, or perceptions associated with trauma; (2) hyperarousal, which is characterized by increased vigilance, anxiety, impatience, and difficulty in focusing; and (3) avoidance, manifested by attempts to get rid of thoughts, emotions, or conversations associated with trauma. The reliability of the scale was assessed with regard to its internal consistency and absolute stability. The internal consistency assessed on the basis of a-Cronbach is 0.92 for the whole scale, and for intrusions, hyperarousal, and avoidance it is, respectively, 0.89, 0.85, and 0.78. Most of the statements correlate above 0.60 with the overall score of the scale (Juczyński and Ogińska-Bulik 2009).

2.2.2. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

To measure depression symptoms, we used the PHQ-9 by 95 (95), in the Polish adaptation by Kokoszka et al. (2016). The respondent marks the answers on a scale from 0 to 3, depending on the frequency of occurrence of a given symptom in the last two weeks. The PHQ-9 was very reliable—a-Cronbach = 0.88. The sensitivity and specificity of the PHQ-9 in detecting an episode of depression were 82% and 89%, respectively, with a cutting point of 12. The results of the PHQ-9 showed a strong correlation with the results of the BDI (rho = 0.92, p 0.001) and the HRDS (rho = 0.87, p 0.001). The Polish version of the PHQ-9 has very good psychometric properties and is an effective screening tool for depression among people aged 18–60 (Kokoszka et al. 2016).

2.2.3. Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS)

The CRS Scale by Huber in its Polish adaptation by 115 (115) is a measure of the centrality of religiosity, i.e., the position of a system of religious constructs in human personality. It consists of five sub-scales: (1) interest in religious issues, i.e., the frequency and importance of cognitive confrontation with religious content, without taking into account the aspect of their personal acceptance; (2) religious beliefs—the degree of subjectively assessed probability of the existence of transcendent reality and the intensity of openness to various forms of transcendence; (3) prayer—the frequency of contact with transcendent reality and the subjective meaning of that contact for an individual; (4) religious experience—the frequency with which transcendence becomes part of human experience and the extent to which the transcendent world of religious meanings is individually confirmed by the sense of communication and action; and (5) cult—the frequency and subjective meaning of human participation in religious services. The overall result is the sum of the subscale results and is a measure of the centrality of the system of religious meanings in an individual’s personality. The scale consists of 15 items with a Likert scale to which the respondents respond, choosing between five and eight possible responses. In each case, the responses are transposed to the five-point scale (the higher the score, the greater the importance/frequency of the behavior). The a-Cronbach factor for the overall score is 0.93, for religious beliefs 0.90, prayer 0.88, and religious experience 0.86. The factor for interest in religious issues and participation in religious services is 0.82. The values of intercorrelation between items and the score in individual subscales indicate the accuracy of a separate theoretical construct, and the subscales can be considered homogeneous (115).

2.2.4. Statistical Methods

Multiple regression analysis was used to determine the general tendency in dependencies between variables. In all the tools used, questions were dedicated to the COVID-19 pandemic (respondents were asked about their reactions to the experienced pandemic event). Statistical calculations were done using the STATISTICA v.13 package (Statistica software—Polish version from StatSoft Corporation Poland, the partner of Tibco Corporation, Palo Alto, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Samples Characteristic

The analysis of differences has not indicated differences between average results obtained by respondents in specific areas (Table 2), as a result of which it was decided to perform further analyses of the results of the whole study group.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and the significance of differences in the intensity of studied variables in men and women.

Diagnostic criteria proposed by authors of the tools were used to assess psychopathological symptoms experienced by the respondents. To assess the results of the IES-R, it is recommended to determine a limit value at which the result obtained by a given respondent may be considered to indicate post-traumatic stress. In accordance with recommendations presented in the literature, it was determined that the cut-off point is 1.4 (Juczyński and Ogińska-Bulik 2009). On these grounds, it should be suggested that 43.2% of respondents have PTSD symptoms (from different groups). The cut-off point for depression was 10, as proposed by Manea et al. (2012), due to the best psychometric values of this approach. In this approach, 28% of respondents experienced depression (Figure 1). The results of the clinical analysis correspond to the results obtained in other countries, demonstrating psychological problems, such as acute post-traumatic stress or depression, among people exposed to trauma resulting from the COVID-19 epidemic and quarantine (Babicki et al. 2021; Brooks et al. 2020; Cenat et al. 2020; Choi et al. 2020; Consolo et al. 2020; Fekih-Romdhane et al. 2020; Gualano et al. 2020; Luo et al. 2020; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al. 2020; 89; 96; 112).

Figure 1.

Clinical diagnosis of the symptoms of PTSD (A) and depression (B) in the study group.

3.2. Multiple Regression Analysis Results

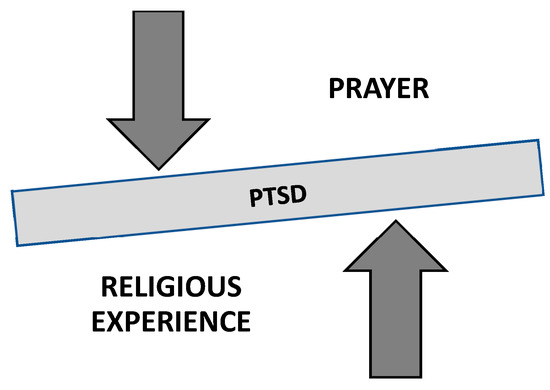

Multiple regression analysis was used to determine the general tendency in dependencies between variables (Table 3). Out of all the supposed depression predictors (model 1), the following ones had a statistically significant influence on the worsening of symptoms in the study group: hyperarousal (p 0.0001), avoidance (p = 0.026), and the age of respondents (p 0.001). No factor of the centrality of religiosity was a predictor of the worsening of depression symptoms. The analysis of regression in model 2 (prediction of PTSD symptoms) shows that the following predictors had a significant stimulating effect on the probability of developing PTSD symptoms: age (p 0.001), depression (p 0.001), and religious experiences (p = 0.001). The only factor of religiosity that significantly lowered the probability of developing PTSD symptoms was prayer (p = 0.014).

Table 3.

Models and results of the multiple regression analysis.

This is a kind of complementarity of effect (Figure 2), because the reduction in PTSD symptoms (which include hyperarousal and anxiety symptoms) caused by prayer was accompanied by the worsening of these sensations caused by religious experience.

Figure 2.

The influence of religious experience and prayer on the severity of PTSD symptoms in the study group—“balm and risk”.

Our study, which provided interesting and non-obvious insights into the relationship between the studied variables, did not fully explain the protective nature of religiosity in dealing with pandemic stress. Out of five components of religiosity understood in accordance with Hubert’s concept, two turned out to contribute to a modification in the severity of psychopathological reactions of the respondents related to pandemic stress during the first wave of the pandemic. While prayer (which in Huber’s concept is understood as making contact with transcendent reality) had a clearly protective role by blocking the worsening of PTSD symptoms, the role of religious experience turned out to be different and exacerbated psychopathological symptoms.

This means that an increase in prayer activity alleviated the symptoms of PTSD. The toning effect of prayer (items: “How often (during the pandemic) do you usually pray?” “How important is personal prayer for you (during the pandemic)?” “How often (during the pandemic) do you pray to God during a weekday?”) may constitute a behavioral buffer (a ritual?), which protects an individual against negative emotions characteristic of PTSD by occupying the individual’s thoughts, guiding them in a different direction or giving them a feeling that they are making an effort to protect their life and functioning.

When it comes to religious experience (the emotional aspect), perhaps it labels the pandemic as God’s retaliatory or punishing behavior (in this case, the pandemic would be treated as an expression of God’s wrath or a punishment). An analysis of items in this subscale indirectly confirms this hypothesis (“How often (during the pandemic) do you experience situations in which you have the feeling that God wants to communicate something to you?” “How often (during the pandemic) do you experience situations in which you have the feeling that God intervenes in your life?” “How often (during the pandemic) do you experience situations in which you have the feeling that God is present?”). After all, the questionnaire does not specify whether God’s communication or intervention should be friendly or cautionary. The pandemic, with its global scale and serious effects, which may be physical (the death of many people around the world), social (social distancing), or psychological (severe stress), is an extremely negative phenomenon and may be perceived as a warning or a threat. It also needs to be emphasized that the first wave of the pandemic was accompanied by extremely dramatic media coverage, which has led to the effect of vicarious traumatization and could have contributed to the escalation of fear, panic, or even the belief in impending annihilation (Ahmad and Murad 2020; Babicki et al. 2021; Cuello-Garcia et al. 2020; Liu and Liu 2020; 117).

It is also interesting that age, which was a predictor of PTSD symptoms, restrained the severity of depression. This means that older respondents most probably experienced more severe symptoms of hyperarousal and anxiety (PTSD) and less severe symptoms of depression.

4. Discussion

According to source literature, religiosity has a preventive and prophylactic effect on individual and social disorders and pathologies. It supports coping processes in traumatic situations by being a source of hope and helping individuals achieve an appropriate distance on the path of revaluation and prioritization according to a specific vision of life (Corveleyn 1996; King et al. 2005; Koenig 2001; Krok 2014, 2016; Maredpour 2017; Merrill and Salazar 2002; Moberg 2002; Pargament et al. 2005). The concept that is usually used in research to explain the protective effect of religion and religiosity is Pargament’s (1996, Pargament and Lomax 2013) concept, which treats religion as a way toward the transmission of a specific philosophical orientation of the world that affects the understanding of the world and makes reality and suffering understandable and bearable. This is confirmed by recent research on the sense of coherence as an effective resource in dealing with pandemic-induced stress (Barni et al. 2020; 111).

Numerous studies on dealing with stress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic consider religiosity to be an effective mental resource in dealing with the reality of the pandemic (Chow et al. 2021; Del Castillo et al. 2020; Galea et al. 2020; Koenig 2020; Lucchetti et al. 2020; Modell and Kardia 2020; Pirutinsky et al. 2020; 111). When it comes to its protective effect on the most common negative consequences of the pandemic, i.e., PTSD and depression, research has been undertaken to confirm this effect and determine the type of its influence using Huber’s theory, which treats religiosity as a collection of specific constructs. This was possible thanks to a questionnaire that could precisely measure specific dimensions of religiosity.

It seems that the best example of a broad metanalysis regarding the effects of religiosity on mental functioning is a study by Koenig (2012), based on an analysis of 601 source materials, which suggests that religiosity (still understood and studied as a multidimensional construct) has a clearly protective effect on health. Later studies also show that religion may play an important role in dealing with depression1 (Aflakseir and Mahdiyar 2016; Fehring et al. 1997; Grossoehme et al. 2020; Lorenz et al. 2019; 98, 100; 110). However, we did not manage to confirm its effectiveness in dealing with depression caused by the pandemic. Our results, which show the ineffectiveness of religiosity in dealing with depression by the respondents, confirm other results, which showed no connection between religiosity and this disorder (Abou Kassm et al. 2018; Miller et al. 2008), showed a selective impact on psychopathological symptoms manifested in mood disorders and the existence of a clearly negative correlation only with suicidal thoughts or behavior (107), or showed a predictive effect of depression (Baetz et al. 2006; Maltby and Day 2000a; Nelson et al. 2002; 97; 94; 108). Koenig’s metanalysis of the available research shows that religiosity is also a resource in dealing with other mental problems, for example addictions, anxiety, or psychosis (2012). Some findings show that there was no association between religiosity and mental health (Fradelos et al. 2018; Rippentrop et al. 2005). However, there are reports that show that various aspects of religiosity are associated with mental disorders, such as anxiety, insomnia, problems with social relationships, and psychoses (Agorastos et al. 2014; Johnson et al. 2011; Joseph and Diduca 2001; Joseph et al. 2002; Kioulos et al. 2015; Kovess-Masfety et al. 2018; Lee et al. 2019; Maltby et al. 2000b; Mohr et al. 2010, 2011; Ng 2007; 93; 103, 102) or PTSD (Connor et al. 2003; 104) in various clinical groups. It has also been shown that religiosity lowers reflectivity and the level of analytical thinking, (Gervais and Norenzayan 2012, Pennycook et al. 2014) although the results of this study were not replicated (90), or does not affect how individuals deal with traumas (Kucharska 2020). Moreover, researchers emphasize that religiosity may also have a negative or harmful effect on mental health when it includes negative affective attitudes towards God, negative religious behavior, and spiritual struggles (Lee et al. 2019; Pirutinsky et al. 2020; 104). In our studies, religiosity, or rather its specific aspect, i.e., religious experience, turned out to be a predictor of an increase in the severity of PTSD symptoms. On the other hand, prayer had a protective role and eased PTSD symptoms, which confirms the results of other studies (Bentzen 2019; Coppen 2020). There is convincing evidence in favor of a relationship between natural disasters and intensified symptoms of religiosity (Bentzen 2019). It is also known that praying is a common way of dealing with adversity. When a disaster happens, people want to be close to God, and praying is the only strategy to achieve it. There is evidence that praying activities have intensified during the current pandemic (Bentzen 2020; Dein et al. 2020), which is also confirmed by our study. Although it is suggested to ascribe mixed and often contradicting results of studies on anxiety and religion to a lack of standardized measures, imperfect research procedures, a limited possibility of assessing anxiety, the bias of experimenters (O’Connor and Vandenberg 2005), and poor operationalization of religious constructs (92), it still seems that standardized measurement methods used in this case and the universally recognized theoretical assumption (Huber’s theory) support the attempt to study their actual role and the mechanisms of correlation between the studied variables.

To explain this phenomenon, it is worth interpreting the meaning of the studied phenomena. Our study has shown that among the aspects of religiosity, prayer and religious experience turned out to be particularly significant (but only in relation to PTSD). However, this does not mean that they had a simple linear effect that alleviated negative psychopathological symptoms (Figure 2). What seems to be particularly important is religious experience, which at the time of a global crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, may include various beliefs, including the belief that the pandemic is a negative message from God (the pandemic as God’s wrath/punishment for sins), which can lead to additional mental tension. However, it is a rather “shallow” (external?) type of religiosity (115), and it is worth thinking about the image of God behind this explanation. Is it not an image of a weak and indifferent God, who no longer controls the world or is not interested in it at all? It seems that it may also show a simple understanding of divine providence as God’s mechanical and immediate intervention on behalf of the requests of people. Perhaps this type of religiosity may lead to guilt or increase tension, as shown in our study. In the literature, intrinsic religiosity is commonly distinguished from extrinsic religiosity. Intrinsic religiosity stands for an internalization of the teachings of religion and finding personal master motives in religion, whereas extrinsic religiosity reflects more instrumental and utilitarian aspects of religion, thereby providing security and solace, sociability and distraction, status, and self-justification (Agorastos et al. 2014; Allport and Ross 1967; Hunt and King 1971). It may correspond with negative religious coping, which reflects a weak relationship with God (e.g., re-evaluating the power of God, feeling abandoned or punished by God, etc.) and the lack of a secure attachment to God (Hall and Brokaw 1995; Hebert et al. 2009; Manning-Walsh 2005; O’Brien et al. 2019; Pargament et al. 1998; 94; 104; 116; 119). It may take many forms: the feeling of anger or of being abandoned or punished by God or the fear that the trauma reflects the doings of the devil or demons (Dein et al. 2020; Isiko 2020). It is also worth mentioning the concept of crisis religiosity, which appears in difficult situations and consists mainly of prayer without deeper involvement (Ahrenfeldt et al. 2017).

It is also worth considering whether or not the effect that age has on the experience of psychopathological reactions confirms (indirectly) this interpretation of the results when older, more religious people experience more tension related to the pandemic (Religious life in Poland. Results of the Social Coherence Survey 2018).

To sum up, it can be said that despite the fact that religious beliefs and practices may serve as a powerful source of solace, hope, and meaning, they are often “intricately” entangled in fears, as well as empirically confirmed neurotic and psychotic disorders, which sometimes makes it more difficult to determine whether they are immunogenic or pathogenic (Huber 2007; Koenig 2012; Pargament and Lomax 2013). It should also be added that the protective property does not have to arise from religiosity itself, but could also stem from elements that are associated with religiosity: avoiding risky behavior due to shared moral standards; social support; the sense of meaning, purpose, and control; and meditation habits, which could inhibit health disorders (Kornreich and Aubin 2012). Nevertheless, detailed mechanisms underlying the protective effects of religiosity on health have not been fully understood yet (Jantos and Kiat 2007; Kawachi 2020; 91; 99; 118). To sum up, it may be concluded that the COVID-19 pandemic has reset former certainties, including those concerning the effects of religiosity and its components.

5. Limitations

We are aware of the fact that our studies are not free from limitations. In our opinion, these limitations are mostly the manner of measurement (via the Internet), the character of the study group, and the unique nature of the studied situation, which limits the replicability of the obtained results:

- The method of data collection: Online studies, which are the only type of studies possible during the pandemic, have already become a standard, but they have their limitations, e.g., the impossibility of fully controlling the study situation, measurement errors resulting from the impossibility of standardizing the study situation, problems with competencies and the nature of online communication, and technical issues (for example, the possibility of taking part in the study multiple times), which should be remembered when results are interpreted.

- Specific proportions in the study group: The group is dominated by women and residents of big cities with higher education, but it is a typical situation in voluntary psychological research conducted on the Internet.

- It is unfortunate that an additional tool, which would make it possible to analyze beliefs about the causes of the pandemic, was not added to the study. It could to a large extent substantiate the results of our studies. We also suppose that the inclusion of other contextual variables, such as the image of God (Hall and Brokaw 1995), could provide data to facilitate the understanding of complex phenomena shown in our studies.

- An unprecedented situation: Numerous changes in all aspects of life caused by the COVID-19 pandemic are an unprecedented phenomenon (Ćurković et al. 2020). This is why it is important to interpret the obtained results with caution, because this situation is unlike any other (the largest reported epidemics of the 20th and 21st century, i.e., SARS 2003, H1N1 2009, and Ebola 2014, did not have the same scale and publicity as the COVID-19 pandemic). Moreover, we need to remember that we had an opportunity to study not only the reaction to the pandemic itself, but also the reaction to long-term home isolation, social isolation, the sudden restructuring of time, the effects of other sudden lifestyle changes, and the results of dramatic media coverage (Cuello-Garcia et al. 2020).

6. Conclusions

The hypothesis presented in this paper was partially confirmed. The analysis of the obtained results shows that there were relationships between religiosity and the severity of psychopathological reactions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in the study group made up of healthy people when there was a total lockdown during the first wave of the pandemic. Symptoms of depression were not in any way modified by religiosity and its individual factors. However, its effect was visible in relation to PTSD. Religious experience turned out to be a predictor that significantly increased the probability of developing PTSD symptoms. The only factor of religiosity that significantly lowered the probability of PTSD symptoms was prayer. Religious matters are important in the assessment and treatment of patients, so clinicians must be open to the influence of religion and religiosity on patients’ mental health. Understanding the role of religiosity in the prevention of mental disorders will help clinicians determine whether it is a source of stress for individual patients. However, the obtained results suggest that in order to interpret the effect of religiosity on the mental functioning of the respondents in time of crisis (the COVID-19 pandemic), we should not try to explain this effect in a simple and linear way, because religious life may not only bring security and solace, but may also be a source of stress and an inner struggle. So is religiosity the remedy to various health problems? The study supplements documentation on a wide range of health consequences, which can be triggered or modified by religiosity. However, more work is required for this evidence to be translated into practical advice for individuals and society.

Unfortunately, we do not know how the pandemic will develop. Even if it will be possible to go back to classic written surveys, the period in which the study was conducted was clearly unique, which will make it impossible to collect comparative material. Due to new information on the nature of the disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the development of the vaccine, and the ongoing adaptation processes (the effect of getting used to the pandemic), results of this type of study (conducted at such a unique and important time in history) will most probably be largely unreplicated. Nevertheless, we hope that they will serve as a new reason to study and try to understand the complex effect that religiosity has on human health in extraordinary situations.

Finally, it is worth adding that although the results provided by the use of typically psychometric tools of psychological measurement seem to suggest that people who are affected by the COVID-19 pandemic mainly experience suffering, and that the pandemic has only negative impacts, it can (and should) be also considered from a broader than psychological stress perspective. It is undoubtedly a time of trial, but also a time that can be used to grow (which is very clearly emphasized by, e.g., the life-span approach). The following example can be cited here: as more men now work at home, the pandemic forces them (and also creates a unique opportunity) to take action and participate in childcare and housework. It is quite a unique situation of their exceptionally long stay at home, which, although forced by a pandemic, may and should be used as an unprecedented opportunity to rediscover the “great absent” fathers of the 20th century. Staying at home together and the necessity of dividing a small home space and controlling emotions in more frequently experienced family conflict situations can trigger thus far unknown forces and skills in organizing a life together. Of course, this requires openness and the ability to accept the available state help, as well as the ability to provide it.

This also means that the studied phenomena can be a field of interpretation for other human sciences, for example for the theology of spirituality. The experience of suffering in the variety of its forms and manifestations is a space and a phenomenon effectively marrying the role and place of spirituality and psychology in their mutual dynamic (101). In psychological research, the objective is not to explain the purposefulness of suffering, but its mechanism and causes (which, perhaps, is a simplification and narrowing of the issue to only the emotional sphere), and a broader philosophical and theological approach allows us to see in suffering the potential for maturation, which reflects the deepest spiritual layers, which can lead to the overall integration of the human person, as well as his/her relationship with others. So, from this perspective, should suffering always be identified with evil? In terms of psychology as an empirical science, the experience of evil and suffering, especially of the innocent, remains an unsolvable problem; however, in Dąbrowski’s (1979) studies, these experiences could constitute a developmental opportunity. Let us remember this while smiling through our tears today.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.T.-B., and R.S.; methodology, W.T.-B., and R.S.; formal analysis, W.T.-B., and R.S.; investigation, R.S., and W.T.-B.; resources, R.S., and W.T.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, W.T.-B., and R.S.; writing—review and editing, R.S., and W.T.-B.; visualization, R.S., and W.T.-B.; supervision, R.S., and W.T.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Economics and Innovation in Lublin (protocol code—3 May 2020; date of approval—13 May 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Abou Kassm, Sandra, Sani Hlais, Christina Khater, Issam Chehade, Ramzi Haddad, Johnny Chahine, Mohammad Yazbeck, Rita Abi Warde, and Wadih Naja. 2018. Depression and religiosity and their correlates in Lebanese breast cancer patients. Psychooncology 27: 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aflakseir, Abdulaziz, and Mansoureh Mahdiyar. 2016. The Role of Religious Coping Strategies in Predicting Depression among a Sample of Women with Fertility Problems in Shiraz. Journal of Reproduction Infertility 17: 117–22. [Google Scholar]

- Agorastos, Agorastos, Cüneyt Demiralay, and Christian G. Huber. 2014. Influence of religious aspects and personal beliefs on psychological behavior: Focus on anxiety disorders. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 7: 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, R. Araz, and Hersh Rasool Murad. 2020. The Impact of Social Media on Panic During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Iraqi Kurdistan: Online Questionnaire Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 22: e19556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahrenfeldt, Linda Juel, Sören Möller, Karen Andersen-Ranberg, Astrid Roll Vitved, Rune Lindahl-Jacobsen, and Niels Christian Hvidt. 2017. Religiousness and health in Europe. European Journal of Epidemiology 32: 921–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allport, W. Gordon, and Michael J. Ross. 1967. Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 5: 432–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbie, E. Earl. 2016. The Practice of Social Research, 14th ed. Boston: Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Babicki, Mateusz, Ilona Szewczykowska, and Agnieszka Mastalerz-Migas. 2021. Mental Health in the Era of the Second Wave of SARS-CoV-2: A Cross-Sectional Study Based on an Online Survey among Online Respondents in Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baetz, Marilyn, Rudy Bowen, Glenn Jones, and Tulay Koru-Sengul. 2006. How spiritual values and worship attendance relate to psychiatric disorders in the Canadian population. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 51: 654–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barni, Daniela, Francesca Danioni, Elena Canzi, Laura Ferrari, Sonia Ranieri, Margherita Lanz, Raffaella Iafrate, Camillo Regalia, and Rosa Rosnati. 2020. Facing the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Sense of Coherence. Frontiers in Psychology 11: e578440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentzen, Jeanet Sinding. 2019. Acts of God? Religiosity and natural disasters across subnational world districts. The Economic Journal 129: 2295–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentzen, Jeanet Sinding. 2020. In Crisis, We Pray: Religiosity and the COVID-19 Pandemic. London: Centre for Economic Policy Research. Available online: https://cepr.org/active/publications/discussion_papers/dp.php?dpno=14824 (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Brooks, K. Samantha, Rebecca K. Webster, Louise E. Smith, Lisa Woodland, Simon Wessely, Neil Greenberg, and Gideon James Rubin. 2020. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet 395: 912–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenat, Jude Mary, Joana N. Mukunzi, Pari-Gole Noorishad, Cécile Rousseau, Daniel Derivois, and Jacqueline Bukakad. 2020. A systematic review of mental health programs among populations affected by the Ebola virus disease. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 13: 109966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Edmond Pui Hang, Bryant Pui Hung Hui, and Eric Yuk Fai Wan. 2020. Depression and Anxiety in Hong Kong during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, Soon Ken, Benedict Francis, Yit Han Ng, Najmi Naim, Hooi Chin Beh, Mohammad Aizuddin Azizah Ariffin, Mohd Hafyzuddin Md Yusuf, Jia Wen Lee, and Ahmad Hatim Sulaiman. 2021. Religious Coping, Depression and Anxiety among Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Malaysian Perspective. Healthcare 9: 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, M. Kathryn, Jonathan R. T. Davidson, and Li-Ching Lee. 2003. Spirituality, resilience, and anger in survivors of violent trauma: A community survey. Journal of Traumatic Stress 16: 487–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consolo, Ugo, Pierantonio Bellini, Davide Bencivenni, Cristina Iani, and Vittorio Checchi. 2020. Epidemiological Aspects and Psychological Reactions to COVID-19 of Dental Practitioners in the Northern Italy Districts of Modena and Reggio Emilia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppen, Luke. 2020. Will Coronavirus Hasten the Demise of Religion—Or Herald Its Revival? The Spectator. Available online: https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/will-coronavirus-cause-a-religious-resurgenceor-its-ruination (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Corveleyn, Jozef. 1996. The psychological explanation of religion as wish-fulfillment. A test-case: The belief in immortality. In International Series in the Psychology of Religion. Religion, Psychopathology, and Coping. Edited by Halina Grzymala-Moszczynska and Benjamin Beit-Hallahmi. Amsterdam: Rodopi, vol. 4, pp. 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Cuello-Garcia, Carlos, Giordano Pérez-Gaxiola, and Ludo van Amelsvoort. 2020. Social media can have an impact on how we manage and investigate the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 127: 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćurković, Marko, Andro Košec, and Danijela Ćurković. 2020. Math and aftermath of COVID-19 pandemic and its interrelationship from the resilience perspective. The Journal of Infection 81: e173–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowski, Kazimierz. 1979. Dezintegracja Pozytywna. Warszawa: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy. [Google Scholar]

- Dein, Simon, Kate Loewenthal, Christopher Alan Lewis, and Kenneth I. Pargament. 2020. COVID-19, mental health and religion: An agenda for future research. Mental Health, Religion Culture 23: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Castillo, A. Fides, Hazel T. Biana, and Jeremiah Joven B. Joaquin. 2020. ChurchInAction: The role of religious interventions in times of COVID-19. Journal of Public Health 42: 633–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehring, J. Richard, Jeff F. Miller, and Colin Shaw. 1997. Spiritual well-being, religiosity, hope, depression, and other mood states in elderly people coping with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum 24: 663–71. [Google Scholar]

- Fekih-Romdhane, Feten, Farah Ghrissi, Bouthaina Abbassi, Wissal Cherif, and Majda Cheour. 2020. Prevalence and predictors of PTSD during the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from a Tunisian community sample. Psychiatry Research 290: 113131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fradelos, Evangelos C., Dimitra Latsou, Dimitroula Mitsi, Konstantinos Tsaras, Dimitra Lekka, Maria Lavdaniti, Foteini Tzavella, and Ioanna V. Papathanasiou. 2018. Assessment of the relation between religiosity, mental health, and psychological resilience in breast cancer patients. Contemporary Oncology (Poznan, Poland) 22: 172–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galea, Sandro, Raina M. Merchant, and Nicole Lurie. 2020. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: The need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Internal Medicine 180: 817–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gervais, Will M., and Ara Norenzayan. 2012. A. Analytic thinking promotes religious disbelief. Science 336: 493–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glock, Charles Y., and Rodney Stark. 1965. Religion and Society in Tension. Chicago: Rand McNally. [Google Scholar]

- Grossoehme, Daniel H., Sarah Friebert, Justin N. Baker, Matthew Tweddle, Jennifer Needle, Jody Chrastek, Jessica Thompkins, Jichuan Wang, Yao I. Cheng, and Maureen E. Lyon. 2020. Association of Religious and Spiritual Factors with Patient-Reported Outcomes of Anxiety, Depressive Symptoms, Fatigue, and Pain Interference Among Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. JAMA Network Open 3: e206696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualano, Maria R., Giuseppina Lo Moro, Gianluca Voglino, Fabrizio Bert, and Roberta Siliquini. 2020. Effects of Covid-19 Lockdown on Mental Health and Sleep Disturbances in Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Todd W., and Beth Fletcher Brokaw. 1995. The relationship of spiritual maturity to level of object relations development and God image. Pastoral Psychology 43: 373–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, R. David, and Neal Krause. 2014. Religion, mental health and well-being: Social aspects. In Religion, Personality, and Social Behavior. Edited by Vassilis Saroglaou. New York: Psychology Press, pp. 255–90. [Google Scholar]

- Hebert, Randy, Bozena Zdaniuk, Richard Schulz, and Michael Scheier. 2009. Positive and Negative Religious Coping and Well-Being in Women with Breast Cancer. Journal of Palliative Medicine 12: 537–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, Stefan. 2003. Zentralität und Inhalt. Ein Neues Multidimensionales Messmodell der Religiosität. Opladen: Leske+Budrich. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Stefan. 2007. Are religious beliefs relevant in daily life? In Religion Inside and Outside Traditional Institutions. Edited by Heinz Streib. Lieden: Brill Academic Publishers, pp. 211–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, Richard A., and Morton King. 1971. The intrinsic-extrinsic concept: A review and evaluation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 10: 339–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isiko, P. Alexander. 2020. Religious construction of disease: An exploratory appraisal of religious responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in Uganda. Journal of African Studies and Development 12: 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantos, Marek, and Hosen Kiat. 2007. Prayer as medicine: How much have we learned? The Medical Journal of Australia 186: 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, Kimberly S., James A. Tulsky, Judith C. Hays, Robert M. Arnold, Maren K. Olsen, Jennifer H. Lindquist, and Karen E. Steinhauser. 2011. Which domains of spirituality are associated with anxiety and depression in patients with advanced illness? Journal of General Internal Medicine 26: 751–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, Stephen, and Debbie Diduca. 2001. Schizotypy and religiosity in 13–18 year old school pupils. Mental Health, Religion Culture 4: 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, Stephen, David Smith, and Debbie Diduca. 2002. Religious orientation and its association with personality, schizotypal traits and manic-depressive experiences. Mental Health, Religion Culture 5: 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juczyński, Zygfryd, and Nina Ogińska-Bulik. 2009. Pomiar zaburzeń po stresie traumatycznym—polska wersja Zrewidowanej Skali Wpływu Zdarzeń [Measurement of post-traumatic stress disorders—Polish version of the Revised Event Impact Scale]. Psychiatria 6: 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi, Ichiro. 2020. Invited Commentary: Religion as a Social Determinant of Health. American Journal of Epidemiology 189: 1461–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Dana E., Doyle Cummings, and Lauren Whetstone. 2005. Attendance at religious services and subsequent mental health in midlife women. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 35: 287–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kioulos, Kanellos T., oanna-DespoinaJBergiannaki, Alexander K. Glaros, Maria Vassiliadou, Z. Alexandri, and George N. Papadimitriou. 2015. Religiosity dimensions and subjective health status in Greek students. Psychiatriki 26: 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, Harold G., Dana King, and Verna B. Carson. 2012. Handbook of Religion and Health. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, Harold G. 2001. Religion and medicine II: Religion, mental health, and related behaviors. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 31: 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold G. 2012. Religion, spirituality, and health: The research and clinical implications. ISRNPsychiatry 2012: 278730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold G. 2020. Maintaining health and well-being by putting faith into action during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 2205–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokoszka, Andrzej, Adam Jastrzębski, and Marcin Obrębski. 2016. Ocena psychometrycznych właściwości polskiej wersji Kwestionariusza Zdrowia Pacjenta-9 dla osób dorosłych [Assessment of the psychometric properties of the Polish version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for adults]. Psychiatria 13: 187–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kornreich, Charles, and Henri-Jean Aubin. 2012. Religion et fonctionnement du cerveau (partie 2): Les religions jouent-elles un rôle favorable sur la santé mentale? [Religion and brain functioning (part 2): Does religion have a positive impact on mental health?]. Revue Médicale de Bruxelles 33: 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kovess-Masfety, Viviane, Sukumar Saha, Carmen C. W. Lim, Sergio Aguilar-Gaxiola, Ali Al-Hamzawi, Jordi Alonso, Guilherme Borges, Giovanni de Girolamo, Peter de Jonge, Koen Demyttenaere, and et al. 2018. Psychotic experiences and religiosity: Data from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 137: 306–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, Dariusz. 2014. Religiousness and Social Support as Predictive Factors for Mental Health Outcomes. Archives of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy 16: 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, Dariusz. 2016. Współzależność religijności z poczuciem sensu życia i nadzieją w okresie późnej adolescencji [Interdependence of Religiosity with a Sense of Meaning in Life and Hope in late Adolescence]. Psychologia Rozwojowa 21: 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharska, Justyna. 2020. Religiosity and the psychological outcomes of trauma: A systematic review of quantitative studies. Journal of Clinical. Psychology 76: 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Sang-Ahm, Eun-Ju Choi, and Han Uk Ryu. 2019. Negative, but not positive, religious coping strategies are associated with psychological distress, independent of religiosity, in Korean adults with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behavior 90: 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Sang-Ahm. 2020. Coronavirus Anxiety Scale: A brief mental health screener for COVID-19 related anxiety. Death Studies 44: 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Cong, and Yi Liu. 2020. Media Exposure and Anxiety during COVID-19: The Mediation Effect of Media Vicarious Traumatization. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 4720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, Louisa, Anne Doherty, and Patricia Casey. 2019. The Role of Religion in Buffering the Impact of Stressful Life Events on Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Depressive Episodes or Adjustment Disorder. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16: 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchetti, Giancarlo, Leonardo Garcia Góes, Stefani Garbulio Amaral, Gabriela Terzian Ganadjian, Isabelle Andrade, Paulo Othávio de Araújo Almeida, Victor Mendes do Carmo, and Maria Elisa Gonzalez Manso. 2020. Spirituality, religiosity and the mental health consequences of social isolation during Covid-19 pandemic. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Min, Lixia Guo, Mingzhou Yu, Wenying Jiang, and Haiyan Wang. 2020. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research 291: 113190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltby, John, and Liza Day. 2000a. Depressive symptoms and religious orientation: Examining the relationship between religiosity and depression within the context of other correlates of depression. Personality and Individual Differences 28: 383–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltby, John, Iain Garner, Christopher Alan Lewis, and Liza Day. 2000b. Religious orientation and schizotypal traits. Personality and Individual Differences 28: 143–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manea, Laura, Simon Gilbody, and Dean McMillan. 2012. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): A meta-analysis. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de l’Association Medicale Canadienne 184: E191–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manning-Walsh, Juanita. 2005. Spiritual struggle: Effect on quality of life and life satisfaction in women with breast cancer. Journal of Holistic Nursing 23: 120–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maredpour, Alireza. 2017. The Relationship between Religiosity and Mental Health in High School Students Using the Mediating Role of Social Support. Health, Spirituality and Medical Ethics 4: 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill, M. Ray, and Richard D. Salazar. 2002. Relationship between church attendance and mental health among Mormons and non-Mormons in Utah. Mental Health, Religion Culture 5: 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, William R., Alyssa Forcehimes, Mary J. O’Leary, and Marnie D. LaNoue. 2008. Spiritual direction in addiction treatment: Two clinical trials. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 35: 434–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moberg, O. David. 2002. Research on spirituality. In Aging and Spirituality: Spiritual Dimensions of Aging Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. Edited by David O. Moberg. New York: Haworth Pastoral, pp. 55–69. [Google Scholar]

- Modell, M. Stephen, and Sharon L. R. Kardia. 2020. Religion as a health promoter during the 2019/2020 COVID outbreak: View from Detroit. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 2243–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr, Sylvia, Laurence Borras, Carine Betrisey, Brandt Pierre-Yves, Christiane Gilliéron, and Philippe Huguelet. 2010. Delusions with religious content in patients with psychosis: How they interact with spiritual coping. Psychiatry 73: 158–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr, Sylvia, Nader Perroud, Christiane Gillieron, Pierre-Yves Brandt, Isabelle Rieben, Laurence Borras, and Philippe Huguelet. 2011. Spirituality and religiousness as predictive factors of outcome in schizophrenia and schizo-affective disorders. Psychiatry Research 186: 177–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, J. Christian, Barry Rosenfeld, William Breitbart, and Michele Galietta. 2002. Spirituality, religion, and depression in the terminally ill. Psychosomatics 43: 213–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, Felicity. 2007. The interface between religion and psychosis. Australasian Psychiatry 15: 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, Brittany, Srijana Shrestha, Melinda A. Stanley, Kenneth I. Pargament, Jeremy Cummings, Mark E. Kunik, Terri L. Fletcher, Jose Cortes, David Ramsey, and Amber B. Amspoker. 2019. Positive and negative religious coping as predictors of distress among minority older adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 34: 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, Shawn, and Brian Vandenberg. 2005. Psychosis or faith? Clinicians’ assessment of religious beliefs. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 73: 610–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, Naiara, Nahia Idoiaga Mondragon, María Dosil Santamaría, and Maitane Picaza Gorrotxategi. 2020. Psychological Symptoms During the Two Stages of Lockdown in Response to the COVID-19 Outbreak: An Investigation in a Sample of Citizens in Northern Spain. Frontiers in Psychology 11: e1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, I. Kenneth, and James W. Lomax. 2013. Understanding and addressing religion among people with mental illness. World Psychiatry 12: 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, I. Kenneth, Bruce W. Smith, Harold G. Koenig, and Lisa Perez. 1998. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 37: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, I. Kenneth, Gina M. Magyar-Russell, and Nichole A. Murray-Swank. 2005. The sacred and the search for significance: Religion as a unique process. Journal of Social Issues 61: 665–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, I. Kenneth. 1996. Religious methods of coping: Resources for the conservation and transformation of significance. In Religion and the Clinical Practice of Psychology. Edited by Edward P. Shafranske. Washington: American Psychological Association, pp. 215–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, Gordon, James Allan Cheyne, Nathaniel Barr, Derek J. Koehler, and Jonathan A. Fugelsang. 2014. Cognitive style and religiosity: The role of conflict detection. Memory Cognition 42: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirutinsky, Steven, Aaron D. Cherniak, and David H. Rosmarin. 2020. COVID-19, Mental Health, and Religious Coping Among American Orthodox Jews. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 2288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Religious life in Poland. Results of the Social Coherence Survey. 2018. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/inne-opracowania/wyznania-religijne/zycie-religijne-w-polsce-wyniki-badania-spojnosci-spolecznej-2018,8,1.html (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Rippentrop, Elisabeth A., Elizabeth M. Altmaier, Joseph J. Chen, Ernest M. Found, and Valerie J. Keffala. 2005. The relationship between religion/spirituality and physical health, mental health, and pain in a chronic pain population. Pain 116: 311–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, Nader, Amin Hosseinian-Far, Rostam Jalali, Aliakbar Vaisi-Raygani, Shna Rasoulpoor, Masoud Mohammadi, Shabnam Rasoulpoor, and Behnam Khaledi-Paveh. 2020. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Health 16: 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, Clinton, Brian Sundermeier, Kenneth Gray, and Robert J. Calin-Jageman. 2017. Direct replication of Gervais Norenzayan (2012): No evidence that analytic thinking decreases religious belief. PLoS ONE 12: e0172636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiber, Judith A., and Dorothy Y. Brockopp. 2012. Twenty-five years later--what do we know about religion/spirituality and psychological well-being among breast cancer survivors? A systematic review. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 6: 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreve-Neiger, Andrea K., and Barry A. Edelstein. 2004. Religion and anxiety: A critical review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review 24: 379–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddle, Ronald, Gillian Haddock, Nicholas Tarrier, and E. Brian Faragher. 2014. Religious delusions in patients admitted to hospital with schizophrenia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 37: 130–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Timothy B., Michael E. McCullough, and Justin Poll. 2003. Religiousness and depression: evidence for a main effect and the moderating influence of stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin 129: 614–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, Robert L., Kurt Kroenke, and Janet B. W. Williams. 1999. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA 282: 1737–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steardo, Luca, r, Luca Steardo, and Alexei Verkhratsky. 2020. Psychiatric face of COVID-19. Translational Psychiatry 10: 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strawbridge, William J., Sarah J. Shema, Richard D. Cohen, Robert E. Roberts, and George A. Kaplan. 1998. Religiosity buffers effects of some stressor on depression but exacerbates others. The Journal of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 53: 118–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svob, Connie, Linda Reich, Priya Wickramaratne, Virginia Warner, and Myrna M. Weissman. 2016. Religion and spirituality predict lower rates of suicide attempts and ideation in children and adolescents at risk for major depressive disorder. Child Adolescent Psychiatry 55: S251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svob, Connie, Lidia Y. X. Wong, Marc J. Gameroff, Priya J. Wickramaratne, Myrna M. Weissman, and Jürgen Kayser. 2019. Understanding self-reported importance of religion/spirituality in a North American sample of individuals at risk for familial depression: A principal component analysis. PLoS ONE 14: e0224141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svob, Conie, Priya J. Wickramaratne, Linda Reich, Ruixin Zhao, Ardesheer Talati, Marc J. Gameroff, Rehan Saeed, and Myrna M. Weissman. 2018. Association of Parent and Offspring Religiosity with Offspring Suicide Ideation and Attempts. JAMA Psychiatry 75: 1062–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatar, Marek. 2012. Duchowość cierpienia wobec wybranych ujęć psychologii [The spirituality of suffering in the face of selected approaches to psychology]. Warszawskie Studia Pastoralne 15: 133–60. [Google Scholar]

- Tateyama, Maki, Mariko Asai, M. Hashimoto, Mathias Bartels, and Siegfried Kasper. 1998. Transcultural study of schizophrenic delusions. Tokyo versus Vienna and Tubingen (Germany). Psychopathology 31: 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tateyama, Maki, Masahiro Asai, Mamoru Kamisada, Motohide Hashimoto, Mathias Bartels, and Hans Heimann. 1993. Comparison of schizophrenic delusions between Japan and Germany. Psychopathology 26: 151–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, Christy T., Eric Kuhn, Robyn D. Walser, and Kent D. Drescher. 2012. The Relationship between Religiosity, PTSD, and Depressive Symptoms in Veterans in PTSD Residential Treatment. Journal of Psychology and Theology 40: 313–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troyer, Emily A., Jordan N. Kohn, and Suzi Hong. 2020. Are we facing a crashing wave of neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19? Neuropsychiatric symptoms and potential immunologic mechanisms. Brain, Behavior Immunity 87: 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unterrainer, Human F., Andrew J. Lewis, and Andreas Fink. 2014. Religious/spiritual well-being, personality and mental health: A review of results and conceptual issues. Journal of Religion and Health 53: 382–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unterrainer, Human F., Helmuth Schoeggl, Andreas Fink, Christa Neuper, and Hans Peter Kapfhammer. 2012. Soul darkness? Dimensions of religious/ spiritual well-being among mood-disordered inpatients compared to healthy controls. Psychopathology 45: 310–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Herreweghe, Lore, and Wim Van Lancker. 2019. Is religiousness really helpful to reduce depressive symptoms at old age? A longitudinal study. PLoS ONE 14: e0218557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walesa, Czesław. 2014. Różnice w zakresie religijności kobiet i mężczyzn [Differences in the religiosity of women and men]. Horyzonty Psychologii 4: 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Samuel R., Kenneth I. Pargament, Mark E. Kunik, James W. Lomax, I, and Melinda A. Stanley. 2012. Psychological distress among religious nonbelievers: A systematic review. Journal of Religion and Health 51: 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger-Litman, Sarah L., Leib Litman, Zohn Rosen, David H. Rosmarin, and Cheskie Rosenzweig. 2020. A look at the first quarantined community in the USA: Response of religious communal organizations and implications for public health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 2269–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Shuiyuan, Dan Luo, and Yang Xiao. 2020. Survivors of COVID-19 are at high risk of posttraumatic stress disorder. Global Health Research and Policy 5: 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Kai, Yi-Miao Gong, Lin Liu, Yan-Kun Sun, Shan-Shan Tian, Yi-Jie Wang, Yi Zhong, An-Yi Zhang, Si-Zhen Su, and Xiao-Xing Liu. 2021. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder after infectious disease pandemics in the twenty-first century, including COVID-19: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Molecular Psychiatry 4: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzycka, Beata, Rafał P. Bartczuk, and Radosław Rybarski. 2020. Centrality of Religiosity Scale in Polish Research: A Curvilinear Mechanism that Explains the Categories of Centrality of Religiosity. Religions 11: 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzycka, Beata. 2009. Tradition or charisma—Religiosity in Poland. In What the World Believes: Analysis and Commentary on the Religion Monitor. Edited by Bertelsmann Stiftung. Gütersloh: Verlag Bertelsmann Stiftung, pp. 201–22. [Google Scholar]

- Zarzycka, Beata. 2014. Struktura czynnikowa polskiej adaptacji Skali Pocieszenia i Napięcia Religijnego [Factorial structure of the Polish adaptation of the Religious Comfort and Strain Scale]. Roczniki Psychologiczne 17: 683–96. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Nan, and Guangyu Zhou. 2020. Social Media Use and Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Moderator Role of Disaster Stressor and Mediator Role of Negative Affect. Applied psychology. Health and Well-Being 12: 1019–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmer, Zachary, Carol Jagger, Chi-Tsun Chiu, Mary Beth Ofstedal, Florencia Rojo, and Yasuhiko Saito. 2016. Spirituality, religiosity, aging and health in global perspective: A review. SSM - Population Health 2: 373–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwingmann, Christian, Markus Wirtz, Claudia Müller, Jürgen Körber, and Sebastian Murken. 2006. Positive and negative religious coping in German breast cancer patients. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 29: 533–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | Caused by various factors, e.g., physical illnesses, addictions, etc. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).