Abstract

In 2012, the Manitoba Museum began the development of an exhibit called “We Are All Treaty People”. Mindful of recent scholarship on animacy and the ontological turn in museum ethnography, this paper examines how this exhibit reversed decades of practice regarding ceremonial artefacts. Twelve pipes, formerly removed from view because of their ceremonial status, have now, as celebrated animate entities, become teachers in a collaboratively developed exhibit about treaties. They will work to educate thousands of visitors, many of them Indigenous children who visit the museum annually. The exhibit was imagined, shaped, and made possible by the Elders Council of the Association of Manitoba Chiefs and the Treaty Relations Commission of Manitoba who treat the pipes as active social partners and, from the outset, intended that the pipes would boldly instantiate Indigenous agency in treaty making. The relational world of the pipes has increased exponentially since they have become public actors in the museum, and more importantly, they have formed deep bonds with the school children and Elders of the community of Roseau River First Nation. They go to the school yearly to be celebrated, sung to, feasted, smoked, and honoured and return to the museum restored and ready for their newfound educational and diplomatic work.

1. Relational Obligations

One of the most productive theoretical paths for museum anthropologists is a comparatively new application of anthropology’s “ontological turn” (Holbraad and Pederson 2017) which takes account of the social role of objects. From Alfred Gell’s Art and Agency1 through Tim Ingold’s Perceptions of the Environment (2000) to the actor–network theory of Bruno Latour (2005) and the activist stance of Martin Holbraad and Morten Axel Pederson in The Ontological Turn: An Anthropological Exposition (2017), anthropologists are finding a vocabulary to interrogate the role and import of objects in modern lives. Museums are, in a sense, a material expression of these ideas—we would not have museums if we did not believe that objects speak—and museums offer fertile ground for examining the role of objects, especially when the relational obligations of collections bring the world views of Indigenous peoples to bear on museums and their practices.

This paper, like the exhibits to which we refer, is the product of a collaborative relationship between the Manitoba Museum’s Curator of Cultural Anthropology, Dr. Maureen Matthews, three Commissioners of the Manitoba Treaty Relations Commission, Elder Dennis White Bird, James Wilson, and Loretta Ross, and their excellent staff, and, very importantly, Dr. Harry Bone, Chair of the Elders Councils of both the Treaty Relations Commission and the Association of Manitoba Chiefs, who, along with the other members of the Elders Council, has guided the process of creating treaty exhibits at the Manitoba Museum from 2012 to 2021. This paper explains how treaty-related museum collections and new collections from First Nations communities have challenged the Manitoba Museum’s foundational paradigms and affected what in Anishinaabemowin you would call meshkwajisewin, a shift in the way we imagine possibilities, a paradigm shift. The process of incorporating demanding artefacts into new treaty exhibits brings colonial legacies into view and re-establishes the agency and generosity of First Nations treaty makers. The Manitoba Museum now has a total of five different treaty exhibits, each one, in its own way, undermining the colonial narrative, instigating change, and providing models for respectful postcolonial relationships.

The history of the Museum’s Numbered2 Treaty exhibits offers an opportunity to explore the importance of meshkwajisewin in rethinking, reframing museum practice. A history of nasty betrayal followed the making of the Numbered Treaties in the 1870s, and people who visit the museum often ask why, given these bitter memories, First Nations people wish to commemorate treaties which have not achieved their promise. The Elders answer that making the treaties was not a surrender of land and not the end of negotiation, but that it was the beginning of an agreement about sharing land and sharing a future, that it marked the start of an ongoing relationship based on principles of caring, respect, and mutual obligation. They argue that as long as these respectful relationships are remembered, there is reason to believe that we will return to the mutually beneficial conversation initiated by First Nations leaders and representatives of the Crown in the late 19th century.

2. The Berens Family Collection

It was in the context of seeking mutually beneficial relationships that the museum began to discuss an exhibit centered in the story of the signing of Treaty Five at Berens River, Manitoba. In 2011, a member of the Berens family approached the Manitoba Museum and offered the original silver Treaty No. 5 medal and the original red Chief’s jacket. The Berens family had been tending these important historic artefacts for over 136 years—ever since they were presented to Chief Jacob Berens, Naawigiizhigweyaash, on the day the treaty was negotiated, 20 September 1875 (Morris 1890). These historic objects, along with a silver 1901 commemorative medal given to Chief Berens by the Prince of Wales and his wife, the future King George V and Queen Mary, on the first royal visit to Western Canada, and a 1940s Chief’s coat given to Jacob’s son Chief William Berens, Tabasigizikweas, had been kept in a trunk in the family home. Over their lives, these pieces had been cared for by three women, Mary (McKay) Berens, wife of Chief Jacob Berens, Nancy (Everett) Berens, wife of Chief William Berens Sr., and Mary Rose Berens, wife of Chief Bill Berens Jr. The collection was brought to the museum in 2011 by another Bill Berens, a great-great-grandson of Jacob Berens, who asked that we use the artefacts to explain the importance of Treaty No. 5, and to tell the history of the Berens family who were Chiefs at Berens for 90 years.

Such a gift needed to be celebrated, so the museum organized a New Acquisitions Exhibit to welcome the collection. The exhibit reunited the coats and medals with portraits of Chief Jacob Berens and William Berens painted by Marion Nelson Hooker and stored at the Archives of Manitoba and the Winnipeg Art Gallery (See Figure 1). In organizing the opening event, we had the help of five energetic Berens cousins: Margaret Simmons, Myra and Jean Tait, Carrie Prystupa, and Myrna Kostiuk. Rather than inviting well-heeled donors for a fundraiser, we decided to keep the opening a family event. As a very new curator, I was asked how many people would come. I had sent 75 invitations and was told that, for these opening-type events, only 1/3 of the people you invite actually come, so we could expect about 25 people. On the night of the opening, over 150 Berens family members came, the largest Indigenous gathering the museum had ever had. Family came from as far away as BC and Ontario, brought together in new and renewed relationships by a couple of medals and a very well-kept red Chief’s coat.

Figure 1.

(Left) Berens Collection New Acquisitions case. 2012. Image Manitoba Museum; (middle): Berens Collection New Acquisitions case. 2012. Image Manitoba Museum; (right): Berens Family Event. 2012. Image Manitoba Museum.

Before Bill Berens’ donation, the museum did have one artefact in its collection associated with the Berens family, a beautifully embroidered moose hide jacket made by Nancy Berens, the wife of Chief William Berens (see Figure 2 and Figure 3). This jacket followed the familiar trajectory shared by many works of Indigenous wearable art. It was made in 1912 for the Methodist missionary Percy Jones, a good friend of the Berens family at the time.3 The jacket does not appear to have been worn much, and in 1980, it was donated to the museum by the Jones family, having been preserved for all those years because of its beauty, and because it carries fond memories of a warm Anishinaabe friendship.

Figure 2.

Silk embroidered jacket H4-11-12. Artist: Nancy Berens. Image Manitoba Museum.

Figure 3.

Silk embroidered jacket H4-11-12. Artist: Nancy Berens. Image Manitoba Museum.

This is the story of many Indigenous artefacts in the museum. They were preserved by non-Indigenous peoples as a remembrance of relationships and personal histories and then donated to the Museum as a material mnemonic of a former life both for the donor and the people they once knew. These trajectories may be the long tail of a public version of “salvage ethnography”, first practiced by anthropologists in the early 20th century, and more recently by missionaries, teachers, and nurses who spend part of their career in the north. The underlying idea of “salvage” collecting, that Indigenous cultures are fading, diminishing, or otherwise becoming inauthentic, has long since been rejected by museum anthropologists, but it has been a common motivation for donors and has resulted in the preservation of many important artefacts. It is probable that large Indigenous collections in many museums are gifts of this sort, originating with well-intentioned donors (Farrell Racette 2008). In the case of Nancy’s jacket, the relationship was rooted in admiration, and Nancy’s authorship as an artist was preserved along with the artefact which is not always the case. However, it is interesting to reflect on the fact that the Berens family themselves did not collect Nancy’s embroidered or beaded jackets, mitts, and moccasins, for which she was justly famous, and which so strongly signify Indigenous artistry. Simply put, they knew she could make more. It was the practice, rather than the work, which was preserved by the family. Through her own relationships, Nancy passed these skills, her skills, on to her daughters, and the museum now has wonderful, beaded gloves made by her daughter Rosie (Berens) Bittern in our collection, thanks to Rosie’s son Bill who insisted they join Nancy’s jacket at the museum as a testament to the family’s ongoing artistry. Through these networks of relationships, these beautiful works have now joined the rest of the collection, challenging the colonial museum paradigm which suggests that Indigenous authenticity lies in the past.

If the Berens family did not hold on to the objects Nancy Berens created, the Berens women did preserve, as family memory objects, the treaty coats and medals that represented the relationships brought about by treaties. For over 130 years, these women placed very great importance on these objects of European manufacture. They privileged them as material evidence of their family’s leadership role in what was a profoundly important event in their community’s history, the making of Treaty No. 5. They looked after them fondly, like old friends. They kept the moths at bay, kept them clean, sewed the buttons back on, brushed them, mended small tears, and stored the coats and medals in a special trunk that moved with them as they travelled. This is an important point because, as Greg Dening has observed, the survival of these objects is not an accident of history, “it is only the destruction of these relics which is accidental. Their preservation is cultural… They gain meaning out of every social moment they survive” (Dening 1996, p. 43).

By considering these Chief’s coats as having social roles and an active type of personhood, they can be situated in an ongoing relational object biography (Peers 1999; Appadurai 1986), and one can pay attention to the additional meanings, as Dening suggests, that accrue with their new relationships. They may have begun life in a context of European manufacture and colonial intentions, but they acquire additional meanings as they become imbricated in Indigenous relationships, bound by Indigenous protocols, cared for by Indigenous hands, and brought forward to tell Indigenous histories. They come to the museum with the dignity of experienced diplomats who have honoured an Anishinaabe protocol; one that transforms gifts of clothing into a guarantor of treaty promises. More than fifty years before Treaty No. 5 was negotiated, as historian Bruce White illustrates, there was an established protocol around the exchange of clothing between Anishinaabe leaders and the Dakota which meant that “each [person] renounced his own self-interest. In the process they ceased being enemies and became brothers or friends” (White 1982, p. 65). On one occasion, William Johnston, a trader at Leech Lake, observed a group of Anishinaabe hunters. “While hunting they had met the Sioux, who came up, and extended the hand of friendship: and to ratify it, as is their custom they exchanged all there[sic] articles of clothing”.4 In 1833, Johnson wrote that when “the Ojibwa leader Okeemakeequid exchanged clothing with a Dakota, a potential enemy became a “brother”. In the same way, the European trader became “kin” when he exchanged his clothing, cloth and blankets for the captains’ furs”.5 For the Berens family, these Chief’s coats and medals constitute material proof of Canada’s obligations to Anishinaabe people through Treaty No. 5; their new role is to remind museum visitors that promises made between the Crown and the leaders of the Lake Winnipeg Anishinaabe are personal obligations and they are not forgotten (Farrell Racette 2004).

However, if the Berens Family Collection reminds the people who visit the museum of the ongoing relationships created by the 1875 Treaty, it also continues to generate new meanings as it engages with the museum and its publics. This collection brings to the museum not one meaning but many. The Chief’s coats, juxtaposed with the impressive paintings of Jacob and William Berens, support a growing public perception of Indigenous agency in treaty making. Nancy’s jacket and her daughter’s mitts contextualize other Indigenous art/artefacts by providing material and aesthetic comparisons and keeping the role of women and their artistic influences in mind.6 They embody ideas about how other similar artefacts might have been made, viewed, or used, thus increasing the historical and interpretive value of the rest of the collection to Indigenous communities. All of these artefacts have the capacity to upend conventional museum power relationships, especially when expertise related to their meaning, provenance, and physical care resides in the Indigenous community. They open museums to shared understandings and have the power to force institutions to concede authority. It is impossible to overstate the importance of contributions such as those of the Berens family to educating the Manitoba Museum about its relational obligations.

I have written elsewhere about Anishinaabe understandings of ceremonial objects (Matthews 2016, chp. 3, 5), that these Anishinaabe other-than-human persons have the capacity to act in the world, and that, given the right social environment, this can happen in museums. I have argued that they have the power to maintain or resume their place in families and, given the opportunity, can create new relationships in museums and between museums and communities. The Manitoba Museum has over 25,000 artefacts that once belonged to First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples. Many of these items came to the museum under some level of duress and suffered the loss of most of their Indigenous provenance, and unlike the Berens coats and medals, most of them have long been estranged from their original families and communities. Thus, these contributions from First Nations families such as the Berens family to the Manitoba Museum are incredibly important. Their provenance is profoundly Indigenous. These objects embody their family’s sense of history and instantiate their personal connection to the treaties. They bring Indigenous histories, Indigenous protocols, and Indigenous family connections with them into the museum. The museum is a complex relational environment, and colonial legacies are often dominant, but these artefacts, as diplomatic and political interventions by Indigenous families, challenge the museum. James Clifford spoke of the museum as a “contact zone” characterized by “copresence, interactions, interlocking understandings and practice, often within radically asymmetrical relations of power” (Pratt 1992, pp. 6–7; quoted in Clifford 1997, p. 192). The Manitoba Museum, as a “contact zone”, remains a place of intersecting intentions, asymmetries of power, and conflicting attributions of agency. However, the relational obligations embedded in the museum’s Indigenous collections combined with the museum’s educational obligations to Indigenous communities have the potential to cause a paradigm shift that pushes back at the colonial inequities that remain part of the legacy of Canadian museums (Clifford 1997, p. 213; Matthews 2016, p. 242; Cf. Task Force 1992, Report on Museums and First Peoples).

3. The Gaagige-Binesi Photograph

For the Manitoba Museum, these stories of relationship and transformative potential embodied in treaty artefacts do not end here. A year after the Berens donation, Ted and Rachel Mann of Sagkeeng First Nation brought to the museum the 1901 commemorative Chief’s medal that once belonged to Chief Gaagige-Binesi (Forever Thunderbird), Chief William Mann Sr. (also known as William Pennefether or Kakekapenais).7 Ted Mann told Dr. Matthews that his father once had a large, framed photograph, a framed original silver halide image from the 1870s of his distinguished ancestor Gaagige-Binesi who was one of the negotiators of the first Numbered Treaty, Treaty No. 1 (See Figure 4). Ted’s father had loaned the photo in its big wooden frame to a student at the University of Manitoba twenty years before, and it had never been returned. He asked for help in finding it. Inquiries at the university turned up nothing at first, and then, in a chance meeting at the grocery store, the head of the Native Studies Department told us they had been cleaning out a bookshelf and found this incredibly dusty old photo on top. They would not have known that it was the 1870s photo of Gaagige-Binesi, or that the family were looking for it, had we not asked. The photo was returned to Ted and Rachel Mann, but after a few months they asked that we use it at the museum to tell the story of their famous ancestor’s role in making Treaty No. 1. This gift is not just a photo. As with the Berens Collection, it brings with it the relationships, with families and others, that follow such gifts into the museum, enriching exhibits and collections, building connections to other Indigenous researchers, curators, and visitors, and challenging harmful stereotypes.

Figure 4.

(Left): Chief Gaagige-Binesi, Forever Thunderbird. Image Manitoba Museum; (middle): Rachel and Ted Mann. Image Manitoba Museum; (right): Mann family 1901 commemorative medal. H4-2-318. Image Manitoba Museum.

Every museum is different in mandate, scope, and affordances. The Manitoba Museum is fortunate that so many Indigenous people have a relatively positive view of the institution. As with the Berens and Mann families, they see the provincial museum as an institution which can tell their stories while helping them to address the challenges posed by protecting and preserving precious histories. The museum has an enviably broad mandate to conduct research, collect artefacts and specimens, and prepare exhibits related to Manitoba, its lands, and peoples—a concise geographical focus. There are currently seven curators whose disciplines include human sciences: anthropology, archaeology, and history; and natural sciences: botany, zoology, and paleontology. The Manitoba Museum has much the same colonial baggage and most of the same structural limitations as other Canadian provincial museums, including a horrifying colonial legacy of artefacts obtained from First Nations and Métis peoples when they were at their most vulnerable, and a rigid taxonomical cataloguing system for Indigenous artefacts that provides no room for acknowledging Indigenous cultural and community relationships (Greene 2016). There are also unavoidable moments of friction when museum rules must be set aside in favour of Indigenous imperatives. The unconditional commitment to consultation is not always easy to achieve in a museum institution. The institutional willingness to take direction from others within an exhibit development process is often hard won. Surrendering the final edit to a community must occasionally be strongly defended within the museum’s exhibit development processes. Permitting and even encouraging hands-on engagement with museum artefacts by community members—from children, through artists and Elders, to ceremonial experts—requires the wholehearted surrender of museum authority. To allow for the relational bonds between communities and artefacts to reassert themselves, these obstacles have to be overcome.

4. The Relational Obligations of Collections

All museums share these frictions because of the unavoidable “asymmetries of power” Clifford identifies, but the Manitoba Museum also has a unique set of affordances that provide opportunities for improving relationships between Indigenous communities and their collections with a minimum of institutional resistance. The most important structural difference between the Manitoba Museum and other provincial museums is that, at the Manitoba Museum, most research and exhibitions are organized around the idea of “biomes”—natural areas of the province which provide the ecological field upon which human and natural history takes place. In these parts of the Manitoba Museum, humans have ecologies, and nature has history. When we talk about the loss of over 90% of native prairie habitat, it is a shared disaster. Throughout the museum, Indigenous and non-Indigenous histories are interwoven and share the same time frame. At no point was there ever a separate exhibit space at the Manitoba Museum for the “timeless” Indigenous culture exhibit, the harmful exhibit that ignores the idea of Indigenous histories and political activism and situates Indigenous peoples and their “lost” cultural identity in the timeless “Indigenous ethnographic present” (Clifford 1983, p. 125). Additionally, as a relatively small museum, the curators at the Manitoba Museum who deal with Indigenous communities are the same individuals who conceive the exhibits, manage their development, select artefacts, and write exhibit text. This means that communities deal with curators and museum management who are in a position to honour requests made in consultation. The other gift that the Manitoba Museum has is its immediate visitor communities. These include many school children and their families from Indigenous, settler, and more recent immigrant communities, and although it is hard to be sure, the curators use a working assumption that 30% of the school kids who will come to the museum in the next few years will have Indigenous family connections.8 The museum’s claim to be “the province’s biggest classroom” and our mandate to serve these Indigenous children place a welcome obligation on the museum to direct programming and exhibits to the needs of this important audience segment. We have stopped writing exhibit text that refers to “they” and “them” because we are now well aware that Indigenous visitors reading this text may be thinking of “me” and “mine”.

Due to this relational imperative, the Manitoba Museum has been a leader in conversations with First Nations peoples about representation. There is a long history of personal connections between Indigenous community leaders and curators. For the last 35 years, there have been no exhibits about First Nations or Métis people which did not involve substantial community engagement. Exhibit development is informed by the values of respect, of making sure that community members are seen and can see themselves in the stories as they are presented. For example, a recent exhibit tells the story of the Métis community of Ste. Madeleine. There, in 1938, with little warning, thirty-five houses, the store, and the community’s school were burnt to the ground while the people were away working. The land was expropriated without meaningful compensation to create a big pasture for cows. At the museum, the story of Ste. Madeleine is told in Michif, with six Métis voices. Creating this exhibit involved substantial engagement between Ste. Madeleine community members and museum staff.9 On opening day, two hundred Métis came to celebrate the exhibit, and five members of the Manitoba Metis Federation Cabinet spoke about the importance of this exhibit to them. At the end of his presentation, Elder George Fleury, who witnessed the tragedy as a child, turned to us and said, “I think at last we have been heard”.10

The museum has also had a leading role in exploring, innovating, creating, and sustaining relationships with Indigenous communities. For the last 20 years, the museum has maintained a “keeping place”, commonly called the Sacred Storage area, cared for by a respected Elder, where Indigenous individuals, communities, and institutions can temporarily place precious objects for safe keeping.11 There is no expectation that the museum will acquire these objects or hold them permanently. Access protocols and care instructions are specified by the owners or the community Elders. There is a slow but steady stream of requests to place important historical and ceremonial objects in this “keeping place”. At present, the museum is caring for objects needing this type of specialized care that include the Tommy Prince medals12, the Pauingassi Collection which was recently repatriated from another Manitoba institution (Matthews 2016), and special ceremonial or sacred objects collected by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.13

5. A Paradigm Shift

However, despite all of this, the Manitoba Museum is also a product of its colonial past. As with other institutions with colonial roots, the museum has not always found it easy to move away from a structural legacy—the far from congenial organizing principle of “cultural evolutionism” or “cultural Darwinism”—and the paradigm that cultures evolve over time on a single trajectory with Indigenous people and other “Stone Age peoples” at the bottom and modern educated Canada at the top has informed museum exhibit strategies and public education for a long time (Stocking 1965). This stigmatizing paradigm specifically disadvantages Indigenous people who appear on this ladder next to Stone Age hunters, as living examples of the primitive past. As a theory, the idea of “cultural evolutionism” or “cultural Darwinism” was discredited by anthropologists more than 120 years ago. As professionals, anthropologists have long since accorded the peoples with whom they work the respect they deserve for finding ways to live meaningful, technically complex, and happy lives in every corner of the world. Franz Boas, the father of modern North American anthropology, wrote in 1896 that anthropologists must “renounce the vain endeavour to construct a uniform systematic history of the evolution of human culture” (Boas 1896, p. 908; Stocking 1966, p. 880; Greenhouse 2010, p. 5).14 The Manitoba Museum’s Orientation Gallery, which opened in 1970 and remained unchanged for 45 years, proposed a cultural Darwinist view of Manitoba history. For years before its closure, museum staff were aware of the problematic nature of this gallery. The Indigenous components of the exhibits had offensive labels and inappropriate photos, but financial constraints and long museum planning cycles meant that in January 2015, this racist and colonial paradigm was still part of visitors’ introduction to the museum.

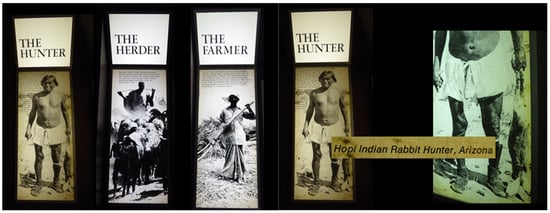

In this introductory exhibit (See Figure 5), three panels exemplified the steps of the cultural Darwinist paradigm. The first image, “Man the Hunter”,15 was followed by “Man the Herder” and then “Man the Farmer”. The unspoken assumption was that farming was a sophisticated technical achievement involving the latest intellectual and economic advances.

Figure 5.

Orientation Gallery panel, Manitoba Museum 2014/08/18. Image Manitoba Museum 2014/08/18.

In this triptych, the panel relating to hunting featured a bare-chested Hopi man with a dead hare in one hand and a wooden club in the other.16 The panel offered no explanation as to why a Hopi hunter in a state of partial undress, whose home was over 2000 km from Manitoba, should be featured in the introductory exhibit to the Manitoba Museum. However, the implication was clear. An Indigenous hunter is an example of the most primitive cultural form; he is our past in the present. As I have mentioned earlier, this idea was rejected by anthropologists more than a century ago. At the time that the museum was built, it was already offensive and out-of-date science. Its presence and persistence in an otherwise sympathetic museum have everything to do with the power of racist stereotypes that have informed Canadian ideas and beliefs about First Nations people more generally. When this panel with its cultural Darwinian paradigm was juxtaposed with the first temporary treaty exhibit in a nearby hall, with paintings and photographs of the thoughtful, suit-wearing First Nations treaty negotiators, its offensiveness became so apparent that it could not be avoided any longer. Within months, a curtain went up across the exhibit, and soon it was gone for good.

However, it is a much bigger job to get rid of this idea in the minds of our visitors. If the paradigm of cultural Darwinism seems familiar, it is. The Manitoba Social Studies and History school curriculums, and I strongly suspect most Canadian school curriculums, are still organized around this paradigm. School children throughout the province, and probably in many other jurisdictions, learn about social history by following the trajectory of the cultural Darwinian paradigm. They start with the Stone Age, and then First Nations people and First Nations culture. They then learn the story of the ascent of humanity as a single-track history traced through the Middle East and Europe from Mesopotamia, and the invention of agriculture and writing through the Egyptians, the Romans, the Dark ages, the Renaissance, etc., up to the present. Students will climb this intellectual ladder at least three times before they are out of high school. Before they arrive at the museum, our visitors’ brains are fully furnished with the cultural Darwinian paradigm and the ideas that flow from it. The celebration of the triumph of European technical and academic achievement which sits at the heart of this racist structure frames Indigenous lifeways as an anachronism.17

Not surprisingly, this insidious paradigm has profoundly negative consequences for Indigenous people. It establishes a story about European cultural superiority and the inevitability of European political dominance. It normalizes the idea that resistance to the brutality of colonization is futile, and that no credible resistance can be mounted. Additionally, it places First Nations cultural authenticity in the past. However, sympathetically, Indigenous cultures may be taught in schools, their anachronistic otherness and their former, but now lost, perfection implicit and unchallenged. In this frame, successful Indigenous people today are hopelessly contaminated by modernity. They can be either culturally whole but part of the past, and therefore irrelevant, or they can be competent in the present but inauthentic. This framing makes First Nations people vulnerable to the judgement of others who use stereotypes about this imagined “authentic past” to criticize the authenticity of successful Indigenous members of society, without considering the impact of one hundred years of intentional cultural genocide under the Indian Act and through the Indian Residential School System. Their current “issues” are constructed as the natural consequence of an inability to be culturally whole in the present.18 When the histories of successful First Nations peoples are told, they are told as exceptions and framed by an assumption of cultural loss. When stories of resistance are told, they are framed by a sense of inevitable failure; the triumph of colonialism and Indigenous powerlessness to cope in the present is assumed. Stories of First Nations struggles are boxed in by the presumption that “their” “issues” are related to categorical Indigenous cultural and personal fragility.

It is this racist and colonial paradigm that the Berens Collection and its strong community relationships challenge (See Figure 6). The coats and medals presented the museum with an opportunity to develop a new exhibit incorporating the latest First Nations thinking about treaties: to turn visitors away from the idea of a treaty as a forced, once-and-done property transaction and toward the idea of the Numbered Treaties as instances of successful First Nations diplomacy.19 Over seven years, one temporary exhibit called “We Are All Treaty People” grew into five permanent exhibits including the introductory exhibit visitors now see when they enter the museum. Throughout, the exhibits were imagined, shaped, and made possible by the Elders Council of the Treaty Relations Commission and the Association of Manitoba Chiefs who looked to the museum’s collection of pipes as socially active allies. From the outset, they intended that the pipes would boldly instantiate Indigenous agency in treaty making.

Figure 6.

(Left): Berens Family Collection/Treaty No. 5 exhibit.; (right): Berens Family Collection, Treaty No. 5 medal H4-2-212 A, B, and 1901 commemorative medal H4-2-213. Image Manitoba Museum.

The discussion between the Manitoba Museum’s Curator of Cultural Anthropology and the Elders Council about how to create an exhibit that would emphasize First Nations agency in treaty making was an opportunity to explore the relationships the treaties set in motion. The Elders Council visited the museum to see the galleries, and Dr. Matthews was a guest at many Elders Council meetings. They felt that the best idea was to match every one of the treaty medals that stood for treaties in Manitoba, Zaagaakwa’on, with a peace pipe, Opwaagan, and pipe bag, Opwaagani-mashkimod. The medals would signify Canada’s treaty promises; the pipes would signify First Nations treaty promises and remind everyone of the sacred nature of the agreement. Beaded pipe bags for each of the pipes would represent the social and spiritual wealth of First Nations people at the time of treaty making and, not incidentally, the artistic and political contributions of First Nations women. The discussions, many of which took place in Anishinaabemowin, ranged from the appropriateness of the display of pipes at all, to the role of a female curator, the wemitigoozhiikwe, because the care and handling of these types of Anishinaabe pipes is conventionally the task of an Oshkaabewis. Ultimately, the discussion turned on the role that the pipes could play in educating First Nations children about their own treaty history. After a lively Anishinaabemowin debate, Elder Dr. Harry Bone carried the day when he said to the others, “If we don’t put these pipes on display, our children will never see them”.

The Elders Council insisted on an exhibit that highlighted First Nations concepts about treaty making. They wanted the respectful long-term relationship that was initiated at the time of treaty making to be explained in First Nations terms, with reference to First Nations protocols, and they wanted visitors to understand that the treaties signed with Canada were neither treaties of conquest, nor land transactions. They were agreements about First Nations’ willingness to share traditional ancestral lands with newcomers as part of an anticipated long-term respectful relationship. The Elders encouraged the museum to use the title, We are All Treaty People, because it contains within it the main ideas about treaties: that all Canadians benefit from the ongoing respectful relationships made in treaty, and that the making of those treaties can provide a valuable model for rethinking obligations and creating future respectful, sharing relationships with First Nations people.

The Elders Council also wanted to introduce visitors to the idea that First Nations negotiators of the Numbered Treaties brought to treaty making a lifetime of experience with settlers, that they had, for the previous 150 years, capably initiated and maintained trading relationships on their own terms. During the fur trade era, trade Chiefs called Odaawaagani-ogimaakaan negotiated “Wiidaakonige’iding, trade treaties”. These annual discussions ordered diplomatic and exchange relationships with newcomers as they had done between First Nations trading partners before ships arrived. In the presence of the “ancestors, Aadizookaanag”, and “spirit guides, Manidoog”, “pipes, opwaaganag”, were smoked, feasts were shared, and gifts were exchanged. First Nations expectations about treaty making were framed by their experience with these ongoing trade relationships. In the context of the Manitoba Museum’s exhibits, both Chief Jacob Berens, Naawigiizhigweyaash, and Chief William Mann, Gaagige-Binesi, were trade captains negotiating with the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) before they entered into treaty negotiations with the Crown (Brown 1998; Berens 2009, p. 207, fn. 23).

The fact that there is no one word for the Numbered Treaties in Anishinaabemowin reflects the novelty and significance of these treaties initiated by the new country of Canada as well as the scope, importance, and even polite scepticism with which they were viewed by Anishinaabe people at the time. Linguists speak about the talents of a language, and while English is prized for its complex sentences, what they say of Anishinaabemowin is that there is no end to the words that can be constructed, and that the words are full of meaning as “tiny imagist poems” (Sapir 1921, p. 244). The language also reveals a tendency to withhold judgement until more is known so the names given to the Numbered Treaties reflect both astute Anishinaabe observation and the nature of the promises made at the time (Cf. Black 1977). Many speakers formally call them Zagaswe’idiwin or Agwi’idiwin—literally, to make a relationship by smoking a pipe, the words imply oversight by the Aadizookaanag in whose presence one would never speak falsely. Additionally, to show that this was not always the case, an American treaty is often called Adaandiwin, a sale or contract, indicating a secular transaction and the idea that money changes hands. In Northwestern Ontario, the words used for treaty specifically reference the idea that it was concluded by writing, either as “Ozhibii’igewin, something that is written”, or as “Nakobii’igan, a written agreement which is endorsed by two parties”. This idea of endorsing something already written is also part of the word for signing an adhesion to an existing treaty, “Nakwebii’igan”. In the southwest corner of Manitoba, the word for the Numbered Treaties, Onashowe’idim, is based on a very old morpheme and refers to a new relationship “brought into being” by the agreement. Others use Maajiseg agwi’idiwin, which means that the treaty is comprehensive and will provide for all eventualities, that it “covers everything, like the snow covers the ground in a snowstorm”.20 These words all contain the hope and expectation that the promises made will be honoured because a pipe was asked to witness events. In all of these instances, the exchange of clothing and the role of pipes in concluding a treaty would have been taken for granted.

6. Pipes Are Diplomats

If the Berens Family Collection placed certain types of relational obligations on the museum with respect to telling the treaty story, the Elders’ desire to have pipes as part of the exhibits created a more challenging obligation because exhibiting pipes is contentious. The Manitoba Museum, as with many other museums, has been taking pipes off exhibit for the last thirty-five years at the request of First Nations groups for whom the casual display of pipes is offensive. They are ceremonial objects, and from an Anishinaabeg or Ininíwag perspective, pipes, when they are assembled—opawaaganag in Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe), ospwâkanak in Ininimowin (Cree)—are other-than-human persons and ought to be treated as such. In these and many other Indigenous languages, pipes are spoken of as if they were a dignified and powerful Elder with work to do. The verbs used to speak of their actions are identical to those used for a human person. Accepting an Anishinaabe perspective and according pipes their proper ceremonial place brings their Indigenous personalities, identities, and surprising relational obligations into the museum.

In this way, pipes challenge a category of object, the sacred object, that is dear to museums, and which often overpowers Anishinaabe understandings within the museum. Sacred objects make perfect sense in a Christian and European context and offer an apparently inoffensive cross-cultural category for conferring respect and cultural deference. Indeed, the Manitoba Museum, long before I came to the institution, had already named the space where pipes are kept the Sacred Storage area. The name remains because it is useful in defining a space for a class of object which museums wish to accord special treatment, involving Elders in their care and using their special status to explain the enforcement of rules about limited access. When speaking English, many Indigenous people also use the word “sacred” to refer to objects they treasure or use in ceremony, but there is no equivalent Anishinaabe category to match the Christian idea of objects which have been made “sacred” for use in a church. That would imply a pre-existing secular identity, a dichotomy which is not an idea conventionally expressed in Anishinaabemowin. The pipes and other Anishinaabe ceremonial objects are “aabajichigan(an), tools, inanimate”, and even “regalia, wawezhi’on(an)”, or the most beautiful of ceremonial decorative objects, mayagaabishin(an), remain grammatically inanimate until they are actually in ceremony or have been identified as wiikannag, ritual brothers actively participating in ceremony (Matthews 2016, p. 253; Cf. Hallowell 2010, p. 540). For instance, a pipe bowl alone, onaagan(an), is grammatically inanimate as is the “pipe stem, okij(iin)”. It is only when they are assembled and the pipe bowl is attached to the pipe stem and the pipe is ready to make smoke that the grammatical attribution changes, and as opawaaganag, pipes step up as other-than-human persons. I am reminded by my Anishinaabe linguist colleagues to be careful not to overdraw the implications of Anishinaabe grammar, and that grammatical animacy is not the straightforward guide to “sacred” status or ceremonial importance that museums might wish (Matthews 2016, p. 72).21

There is no doubt that pipes were present and playing their historic diplomatic role at the signing of the Numbered Treaties. The photograph below, taken at the Northwest Angle where Treaty No. 3 was signed (See Figure 7), shows four men standing at the center; three are wearing treaty medals and two are holding long ceremonial pipes.22 When the idea of pairing pipes and medals first came up, we consulted Elder Doreen Roulette, who looks after the needs of these ceremonial objects at the museum. She directed us to what you might call “peace pipes”. This type of pipe has a particular shape, usually a long slim t-shaped bowl of sometimes highly decorated red catlinite or black steatite pipestone. These pipes often have a very long pipe stem as in the photo below.

Figure 7.

(Left, middle): Treaty No. 3, 1873, at the Northwest Angle, Ontario. Image Manitoba Museum. (Right): Treaty pipes. Image Manitoba Museum.

These dramatic peace pipes were often given as gifts to confirm a treaty or establish a relationship. For example, when Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk visited his Red River colony in 1817, in what is now Manitoba, he made treaty with five Chiefs, including Chief Peguis, an Anishinaabe leader who played a very important role in the early history of the settlement. In 1814, well before Selkirk’s 1817 visit that resulted in a peace treaty, Chief Peguis paid a visit to Miles Macdonell, the colony’s governor. Macdonell described the visit in his diary: “Peguis came to visit me with his Flag and Pipe of Peace which he leaves with me as a token of his Friendship”.23 This gift of a pipe to honour or initiate a friendship follows Indigenous protocols related to the establishment of long-term personal relationships.24 Another journal entry, this time by fur trader Peter Fidler in 1815, shows that Peguis had sent pipe stems to England to stand in for him in negotiations and that he expected they would return once their diplomatic journey was completed.25 In 1824, Peguis sent a pipe with the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Governor George Simpson as a present to his “Friends in England”.26 In 1838, he sent a pipe to the Church Missionary Society with the explanation that “I send by you a pipe and a stem. The stem according to Indian custom, personifies [or stands in the place of] the one who sends it, and ratifies and confirms the message which accompanies it”.27

7. Pipes Are Teachers

Accepting the idea that pipes can be diplomats and represent First Nations political concerns means accepting that they can be teachers and represent First Nations perspectives in the museum. In coming to grips with this idea, the institution is tacitly recognizing that museum artefacts as other-than-human persons have the capacity to act in the world. These are objects (and relationships) that can turn museum authority on its head. Not only are they grammatically animate and spoken of as if the subject was a powerful old man, they are “wiikaanag, ritual brothers”. The pipe and those who smoke it become brothers through participation in ceremony, a foundational relationship in the context of the museum and Indigenous communities.

This idea of objects with familial relationships, ceremonial obligations, and a capacity to act in the world is not just a form of magical thinking indulged in by Indigenous people. We would not have museums if we did not, at some substantive level, believe that historical and cultural information inheres in objects: if we did not believe that these objects speak to us across time and convey cultural meaning across cultural boundaries. This way of thinking parallels a new body of anthropological theory which considers the implications of treating certain types of objects as having qualities of personhood (Strathern 1995, 2004a, 2004b; Gell 1998; Latour 2005; Ingold 2000; Bird-David 1990, 1999; Vivieros de Castro 1996; Matthews 2016),28 and that has turned to the possible personhood of objects to critique those who understate the role of objects in social relations. Museum scholars have long been aware that objects have the capacity to change understandings and reinvigorate cultures (Conaty and Janes 1997; Peers and Brown 2003; Krmpotich 2014). In this context, while these exhibits might seem, on the face of it, to be just another uneventful collaboration with Indigenous people, they are also a disruptive gesture toward respectful relationships with person-like objects that have long First Nations histories and unknowable power. When the pipes are invited to stand up for First Nations people in an exhibit and use their influence to convey the message that treaties were made in good faith, we are all obliged to honour them.

In this way, the pipes are bringing their world into the museum, and as they do this, their points of reference become ours. As I mentioned earlier, when we began thinking about the first treaty exhibit, we were given a tutorial on pipe taxonomy from our most senior Elder who looks after the objects in the “keeping room”. Elder Doreen Roulette identified the pipes which had the necessary combination of competence and public purpose to be comfortable in an exhibit (See Figure 8). As an Anishinaabe speaker, Elder Roulette’s context for the pipes and their possible role as museum performers is framed by the Anishinaabe language. Izhigaabawi is the word she uses to speak about the pipes having the appropriate social standing or status to perform a particular task. Oniibawitaan is a pipe that will stand and speak on one’s behalf or represent someone in negotiation. Zaagaswe’idim is the way that Elders “share tobacco and a pipe with one another”. As she pointed out, the pipes which have been given a role at treaty and peace negotiations in the past, witnessing, attending, and assisting, have become “wiikaanag, ritual brothers”, of those who led the negotiations. Those pipes were created with the intention of having this public persona and could therefore be used for display in the museum. She said that they were confident, even “kind of proud, wawezhi’owag”.29 These pipes are “nindoonabiitaan, ready to stand up or do what they are called upon to do”. In ceremony, you say to such a pipe as you pass it on to others, “Giigidootamishin, Speak on my behalf!” There are other types of pipes, she explained, including women’s pipes like her own, that are very personal and would not be suited to this task. Elder Roulette checked each pipe in the museum’s collection and carefully selected pipes which she judged to be in a certain “state of grace, izhigaabawi”, that they would “oniibawitaan, they would appreciate this task”.

Figure 8.

Elder Doreen Roulette and Elder Charlie Nelson at the opening of the We Are All Treaty People exhibit, 2015. Image Manitoba Museum.

What does it mean to interact with a pipe as an animate entity capable of acting in the world, a pipe that is willing to take up this teaching task, oniibawitaan? In treaty making, these types of pipes initiate communication with “Bawaaganag, spirit entities”, and in so doing, they bring the concerns and protocols related to the Bawaaganag into the museum. The pipes have been asked to make smoke, asemaa (also animate), which acts as a messenger to the world that Bawaaganag occupy, a world that shares the same geography as the world of everyday life, but which can be visited only in dreams.

Hallowell called this geography the “unified spatiotemporal frame” of the Anishinaabeg (Hallowell [1955] 1988, p. 97). Anishinaabemowin translator Roger Roulette suggests you could say the Anishinaabe employ a sort of many-worlds quantum physics model of the universe (Everett 1957; Cruikshank 1979), in which these two parallel Anishinaabe worlds occupy the same geography: one, the everyday world of human existence, and the other, the home of the Bawaaganag. The Bawaaganag act as intermediaries between humans and the overarching power of the universe, “Gaa-dibenjiged, the owner of all”, whose powers transcend both worlds. The spirit world is rarely encountered by humans, and no one would expect to see Bawaaganag in everyday life, but what happens there affects everyday life, and this boundary is frequently crossed in dreams, during a young man’s vision quest, or in the course of a medicine man or woman’s practice. There are various indications of the demarcation between the two worlds. In stories, a narrator might step over a log, dip under the surface of a lake, or enter a magical black and white world.30 On other occasions, clouds or the morning mist would be said to indicate the proximity of unseen spirits. This is the type of experience referred to by the Anishinaabe word “manidoobaa, where the spirit exists”. An anglicized version—Manitoba—is the name of our province. Apparently, when the smoke of a peace pipe dissipates, it is said to be “going there”. It is understood to be crossing that intangible border between this world and the spirit world. The smoke carries with it a request to the spirits to observe and verify the promises being made. Roulette says of the spirits, “They like smoke, and it’s also the closest way to contact them, [from] their world to ours. Smoke is apparently enjoyed by the spirit-beings” (Matthews 1995a, p. 14; 1995b).

Having once decided to include pipes and their protocols in the exhibit, the Elders Council directed me to Charles Nelson, a respected and thoughtful Elder from Roseau River. There is, of course, no “traditional” ceremony to facilitate the presence or exhibition of a pipe in a museum. One hundred years ago, from an Anishinaabe traditional ceremonial perspective, it would have been inconceivable. What this situation required was an innovative approach: the creation of a ceremonial invitation to the pipes to perform as Anishinaabe ambassadors in a treaty exhibit, to play a diplomatic and educational role within a museum on behalf of First Nations people. Elder Nelson agreed to think about how this might be done using a combination of existing ceremonies to initiate a pipe, to honour it, and to offer it as a diplomatic gift. The ceremony for the temporary exhibit in 2012 was ground-breaking and heartfelt. It took place in a small gallery where a temporary treaty exhibit had been set up. All the case lids were removed, and the pipes were placed on bison hides on the floor of the gallery. Smoke billowed through the museum as the pipes were prayed to, sung to, and feasted. The Elders present (25 in all) read every word of exhibit text, rightly observing that they were not just addressing the pipes but endorsing the exhibit itself. A sometimes emotional discussion about the obligations of the Manitoba Museum to truth telling, especially around the issue of Residential Schools and the fate of missing and murdered Indigenous women, was followed by songs, prayers, and feasting.

In preparation for the opening of the permanent exhibit a year later, we spoke to Elder Nelson and suggested that, rather than have all of those Elders come to Winnipeg, we could bring the pipes to them in Roseau. That fall, the Treaty Pipe Feast ceremony was held in the gymnasium of Ginew School in Roseau River First Nation two hours south of Winnipeg (See Figure 9). Eight pipes, several medals, two Chief’s headdresses from the 1870s, and a 3D model of the exhibit travelled to the school.

Figure 9.

Treaty Pipe Ceremony at Roseau River First Nation. 2016 Image Treaty Relations Commission of Manitoba.

Elder Nelson’s “oshkaabewisag, his apprentices”, took possession of the pipes as soon as we arrived at the school. They took the pipes to the gym, unpacked them, and placed them on the bison hides in the middle of the gym floor. The Elders sat on low benches around the edges of the hides. The preparation of a water drum for ceremony takes about 30 min, so as the children came into the gymnasium, Elder Nelson spoke to them about the significance of the event. Songs had been sung and prayers given when Elder Nelson suggested that perhaps it was time to smoke some of the pipes. His oshkaabewis pulled out his pen knife and began to clean and prepare the stone pipe bowls. Some of these pipes had not been smoked for 125 years, and not all were completely intact, but Elder Nelson chose five working pipes and handed them out to men around the room, choosing pipes with special meanings for certain individuals. He gave the Treaty No. 5 pipe to Commissioner Wilson whose home reserve is part of that treaty. Toward the end of the ceremony, Elder Nelson observed that the pipes, now lying on a bison hide robe after they had been smoked, would be behind glass for a year, and that they would find this easier with more human connection. He invited everyone in the room to lay a hand on each one and wish them well. He touched each pipe thoughtfully and looked at me, so I followed his lead, and then a sort of impromptu reception line formed, and everyone in the room, from the Treaty Commissioner to the smallest child, knelt and touched the pipes in a gesture of community support and connection. This was a mind-changing experience, and everyone involved felt that they had been a part of something magical.

When people hear about this ceremony, they will often ask if they can attend, but this is not a show; it is not a performance. This is the ceremonial work that needs to be performed for such an exhibit to be at the museum. Its purpose is to invite other-than-human persons to perform in a museum institution on behalf of First Nations people. The museum is committed to taking part in this ceremony annually, and after seven years, it has stabilized as an event which is welcomed by the museum and the community (See Figure 10). In inviting Elders to smoke the pipes, Elder Nelson made it possible for the pipes to initiate new relationships, many of which have been sustained ever since. These pipes, with little in the way of museum history, now have new and profound First Nations relationships and a meaningful political and teaching role to fulfill.31

Figure 10.

Elder Nelson Johnson sharing a Treaty pipe with students at Roseau River First Nation. Image Josephine Hartin.

Since this first ceremony, Charlie Nelson’s sister, Josephine Hartin, the school’s vice principal, has organized the event each year. She says that the ceremony is important because “the children need to see how we care for these pipes. We want to pass on that knowledge. It is physical, the touching of the pipes. You help us to do that work when you bring the pipes. What matters is your intention, your connection to us” (Pers. Comm Feb 2021). It never fails to be a wonderful experience, but more importantly, without the work that is performed at the school each year, we could not have pipes on exhibit in the museum, and there would be no treaty exhibits.

James Clifford suggests that a museum, in welcoming a mission of “contact work” such as this, and submitting to the relational obligations of its collection and its Indigenous community, could become a museum “decentered and traversed by cultural and political negotiations that are out of any imagined community’s control—[a] museum that begin[s] to grapple with the real difficulty of dialogue, alliance, inequality and translations” (Clifford 1997, p. 213; Matthews 2016, p. 242). In welcoming the pipes in their role as teachers, the Manitoba Museum has made tentative steps in this direction. The new treaty exhibits provide a radical departure from the patronizing arrogance of the cultural Darwinist paradigm. The presence of the pipes firmly places interpretive authority outside the museum among contemporary Indigenous ceremonial experts. Their participation in the treaty exhibit has made the museum an institution dependent upon multiple Elders including Doreen Roulette for the selection of the pipes, the Elders Council of the Treaty Relations Commission for the authority to organize the exhibit, and the Elders at Roseau River for the ceremonial expertise to make the exhibit possible. Through their work, the pipes have created the possibility that the museum will become a thoughtful partner in the type of respectful long-term relationship with First Nations people which the makers of the treaties envisaged.

At about the time that the We Are All Treaty People exhibit opened, the idea of voicing a treaty land acknowledgement became an imperative throughout Canada. During a visit to the museum by the Elders Council, we asked what the next step at the museum should be, and after some thought, they said that when we were renewing the galleries, we should move the treaty exhibit up to the entrance of the museum so that it would become the first thing people see, so that the pipes and medals would stand before visitors like the treaty acknowledgement at the beginning of a meeting.

This new treaty exhibit (See Figure 11) opened in April 2021 with eight pipes and eight medals.32 Here, the eight pipes offer a declaration that before you learn anything else about Manitoba, you need to know this: You are on Treaty Land and your teachers stand before you.

Figure 11.

(Left): Exhibit panel, You are on Treaty Land. Image Manitoba Museum; (right): Exhibit case with pipes and medals. Image Manitoba Museum.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.M. and J.B.W.; methodology, M.A.M., J.B.W. and R.R.; investigation, M.A.M., R.R. and J.B.W.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.M. and R.R.; writing—review and editing, M.A.M., R.R. and J.B.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Alfred Gell argues that “[s]ince the outset of the discipline, anthropology has been signally preoccupied with a series of problems to do with ostensibly peculiar relations between persons and ‘things’ which somehow, ‘appear as’ or do duty as, persons” (Gell 1998, p. 9). |

| 2 | There are many treaties with First Nations in Canada, but the Numbered Treaties start after Canadian Confederation and are related to traditional territories of First Nations peoples from west of Lake Superior to the Rocky Mountains. Treaty No. 1 was made in 1871, and Treaty No. 11 and various adhesions were still being ratified in 1921 (Craft 2013; Foster 1979; Price 1979; Taylor 1979). |

| 3 | William and Nancy’s third son Percy Jones Berens was named after Rev. Jones who was the United Church Minster in Berens River at the time. |

| 4 | William Johnston, in Michigan Pioneer Collections, 37:186. See also William W. Warren, “History of the Ojibways, Based Upon Traditions and Oral Statements”, in Minnesota Historic al Collections, 5:268 St. Paul 1885 cited in (White 1982, p. 65) (Cf. Podruchny 1995). |

| 5 | As quoted in (White 1982, pp. 63–64) from the letters of William Johnston, 1833. |

| 6 | Nancy (Everett) Berens’ Méis grandmother was a Cree woman from Norway House married to Joseph Boucher, a French voyageur from Quebec. Nancy’s embroidery style is typical of Cree and Cree Métis women from Norway House, and although Nancy eventually became the wife of one of the most famous Anishinaabe chiefs on Lake Winnipeg and lived in Berens River most of her life, the embroidery and beading styles she passed on to her daughters were Norway House Cree/Cree Métis. |

| 7 | This is a bronze version of the silver medal belonging to Chief Jacob Berens. These bronze medals were sent to Chiefs who were unable to meet with the Prince of Wales in person. In all, over 200 medals were distributed to Western Canadian Chiefs. Ted Mann’s father gave him the medal as a wedding present 30 years earlier. Ted told us that his father also had the treaty medal at the time but later sold it to buy golf clubs. After the photograph was located, Ted and Rachel kept it at their house for several months before they decided it needed to be at the museum. In working out the provenance of the photo, I was directed by a friend to an old CTV, W5 investigative story from the 1960s about terrible housing on Sagkeeng First Nation. The reporter was interviewing people with inadequate housing, and one of them was Ted’s father, Sam, who told the audience that he did not understand why he, his wife, and seven children had to live in such a small house when his grandfather had signed Treaty No. 1. As the reporter looks on, he climbs on a bed and brings down this photo and continues the interview while stroking grandpa’s photo. W5, Air Date: 07/01/1968. Item: Native Poverty and Indian Affairs Panel Discussion—Item No. 124451634. |

| 8 | The proportion of Indigenous children in Winnipeg schools has been rising over time as First Nations families move to the city. Statistics Canada 2016 census data for Manitoba show that 28% of Manitobans under 20 self-identify as Indigenous and those under 5 years of age constitute 30% of Manitoba’s population. Please see: https://www.gov.mb.ca/healthychild/publications/hcm_2017report.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2021), p. 39. The City of Winnipeg Infrastructure Planning Office extracted census data for Winnipeg and found that 28% of Winnipeg residents under the age of 14 are Indigenous and that the proportion of Indigenous Manitobans living in the City of Winnipeg has increased from 34% to 38% over the last 20 years. “The self-identified population of Indigenous people in the City of Winnipeg’, they write, “has grown by more than 10,000 people over the past 5 years”. There is no reason to think that this has not continued. Please see: https://winnipeg.ca/cao/pdfs/IndigenousPeople-WinnipegStatistics.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2021), pp. 6–7. Coming to the museum is a favourite trip for First Nations schools so this estimate may be conservative. |

| 9 | Ste. Madeleine exhibit is called “Ni Kish Kishin, I Remember, St. Madeleine”. The exhibit text is in three languages: Michif first, English, and French. The case includes ecological information as the site of the village is now an example of the rare survival of critically endangered native prairie birds, insects, and plants and an ecological diversity hot spot—an example of museum story telling which includes natural and human histories. See also: (Paul 2019). |

| 10 | Elder George Fleury repeated this quote in an article by CBC journalist Shane Gibson (2019), “’We lost our homes’: Museum exhibit tells story of Métis village’s displacement”: CBC News Posted: 24 May 2019. 9:36 PM CT|Last Updated: 24 May 2019, accessed 7 May 2021. |

| 11 | This space is also designed to store objects that are within the museum’s collections to ensure their needs are met, they are under the proper care of an Elder, and access is restricted. |

| 12 | Tommy Prince, a member of the Brokenhead First Nation in Manitoba, was the most decorated Indigenous soldier in World War 2, and his medals were lost for a time. When they were rediscovered and purchased at auction, the owners asked the museum to keep them in our vaults. They are visited and go on outings from time to time at the request of or with the permission of the owners but otherwise remain in the museum. They have recently been put on permanent display because several copy sets have been purchased by the medal owners for use in schools and public events, but they still go out at least once a year for commemorative events. |

| 13 | Dr. Katherine Pettipas, former Curator of Ethnology at the Manitoba Museum, was one of the major contributors to the Task Force on First Nations and Museums (1993) and remains a respected advocate for repatriation and collaborative exhibit development. Dr. Leigh Syms, the former Curator of Archaeology, developed a pioneering project community archaeology project to salvage Cree gravesites inundated by floodwater on South Indian Lake. |

| 14 | Stocking explains that Boas, over a period of 30 years, developed a critique of cultural Darwinism that “involved the rejection of simplistic models of biological or racial determinism; it involved the rejection of ethno-centric standards of cultural evaluation; it involved a new appreciation of the role of unconscious social processes in the determination of human behavior; it implied a conception of man not as a rational so much as a rationalizing being (Cf. Stocking 1966. Taken as a whole, it might be said that this change involved-to appropriate the language of Thomas Kuhn-the emergence of what may be called the modern social scientific paradigm for the study of Boas and the Culture Concept”. |

| 15 | The Man in each of these panels was removed 15 years before when the museum changed its name from the Museum of Man and Nature to the Manitoba Museum. |

| 16 | Image credit: Peter Newark American Pictures/Bridgeman Image PNP246124. |

| 17 | Building community relationships is a hidden part of museum work. What the public experiences is the galleries. It is expensive and complicated to change “permanent exhibits” in galleries. In 2016, with the help of Indigenous Curatorial Assistant Amanda McLeod, we documented 92 instances of unfortunate language in the existing exhibits, including “Half Breed wives” and more than 20 “Indians”. This is not language we use, nor have we used it in a long time, but it lives on in old, outdated exhibits. The three panels mentioned here introduced the visitors’ experience for more than forty years, framing the interpretation of Indigenous stories within the museum, including photos of an “Eskimo” hunter and an artefact labelled “Indian knife”. |

| 18 | For more on the negative consequences of this idea that First Nations and Métis peoples are unable to adapt to modernity, see Mary Jane Logan McCallum (2014), on Indigenous women and work, and Evelyn Peters et al. 2018, about forced removal of Métis families to make way for a Winnipeg shopping mall. |

| 19 | The Elders were chosen for their knowledge, their history of advocacy, and the respect that others have for their wisdom. This cohesive group represents the Dakota, Ininíwak, Anishininíwak, Anishinaabeg, and Denesułine people of the province First set up in 2005, they had been meeting, commissioning research, conducting extensive community oral history interviews, and publishing books about treaties for ten years when discussions about this exhibit began. The Elders Council were ideal partners for this project because their educational mandate neatly parallels that of the museum. Some of the other famous Canadian Indigenous exhibit collaborations, such as the creation of the Blackfoot Gallery at the Glenbow (Cf. Conaty 2003; Conaty and Janes 1997). were, in large part, facilitated by the existence of a First Nations institution with the mandate and community support to confidently answer questions of culture, message, and representation. In the case of the Glenbow, it was the Mookaakin Culture and Heritage Foundation (Cf. Peers and Brown 2015; Nicks 2003). The Elders Council played this role for the Manitoba Museum with respect to treaties, and without their encouragement and firm direction, the museum would not have developed the treaty exhibits in the way that it did. |

| 20 | Roger Roulette Pers.Comm. (July 2021). James Chalmers wrote an excellent student paper in 2020 on the Anishinaabe words for treaty as part of the Manitoba Museum’s Indigenous Scholars in Residence program. We thank him for gathering most of these terms together and examining their history. In his paper, he lists several other words for treaty used in other parts of Canada and the US (Chalmers 2020). |

| 21 | Anishinaabemowin speakers are well known for the distinction they make between animate and inanimate things. The meaning of this grammatical propensity is hotly debated, but there is no doubt that speakers do attribute social agency to entities such as pipes, treating these objects as responsive and sentient beings. Sometimes these attributions become grammaticalized; particular classes of entities receive special grammatical treatment and are cast as grammatical animates. This is true, for example, of many items associated with traditional religious practice and ceremony, such as “opwaagan”, “pipe”, “asemaa”, “tobacco”, and dewe’igan, “drum”. However, even in the case of the drum, there is a grammatical form which is inanimate, and using inanimates to disguise the importance of an object fits an Anishinaabemowin convention that Mary Black Rogers calls “discrete speech, waawiimaajimowin”. See (Black 1977; Matthews 2016, p. 72). |

| 22 | In the photo of a Treaty No. 3 event at the Northwest Angle (the western most tip of Ontario), you really cannot tell the Treaty Commissioners from the Chiefs. They were all wearing suits. For the most part, they knew one another well. Many of them had been involved in the fur trade together, and by the 1870s, there existed a 200 year-long history of relationships built on non-Native dependence on Indigenous skills and technologies. The canoes in the photograph are an example. The negotiator for Treaty No. 1, Weymouth Simpson, was the son of Sir George Simpson, Governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company and resident in the west for many years and Governor of the HBC from 1820 until he died in 1860. I would like to thank Anne Lindsay for pointing me to the identity of the people in this photograph. |

| 23 | He then lists a keg, blankets, and other presents he gives to Peguis and his family in exchange. In Miles Macdonell Diary, Friday, 20th May 1814, Selkirk Papers, f. 16900, Reel C-16, https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c16/414?r=0&s=2 (accessed on 6 October 2021) Library and Archives Canada. I would like to thank Anne Lindsay for directing me to this section of Macdonell’s diaries. |

| 24 | In the case of the people of Peguis First Nation and the Lord Selkirk, this relationship is still honoured. For the 200th Anniversary, the 11th Lord Selkirk, James Douglas Hamilton, came to Manitoba to personally renew the relationship with the current Chief at Peguis, Glenn Hudson. Gifts were exchanged, and whenever Peguis and Brokenhead FN Chiefs are in London, they are invited to dine with Lord Selkirk at the House of Lords (Bill Shead and former Chief Jim Bear Pers. Comm. 2017). |

| 25 | As Sarah Carter writes, “Speaking to an assembly led by Saulteaux chiefs Peguis and Yellow Legs in June, 1815, HBC surveyor Peter Fidler referred to the King as the ‘Great Father of us all’, encouraging them to believe that the British monarch had a special interest in their welfare. Fidler told them that the Governor of the HBC had gone overseas, and had taken the Cree and Saulteaux’s pipe stems with him ‘…in order that he may talk to our Great Father, that he may be charitable to you and your Friends--and we expect that when you see your Pipe stems again, you will be proud from having been the Friend to his Children in his Absence…’” (Carter 2004), http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/mb_history/48/greatmother.shtml (accessed on 6 October 2021). Thanks to Anne Lindsay for her assistance with these historical records. The text of the document can be found here: https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c17/909?r=0&s=4 (accessed on 6 October 2021). 1815, June 24th entry, f 18498–18499, in Library and Archives Canada, Selkirk Papers, Journal at Red River Settlement with the account of the Population of the Free Canadians and the three Tribes of Indians in this Quarter with a Meterological Journal and Astronomical Observations made at different places by Peter Fidler, to which is added the Astronomical Observations of Thomas and Charles Fidler 1815. |

| 26 | Letter, R.P. [Robert Parker] Pelley, June 7th, 1824, Library and Archives Canada, Selkirk Papers, f. 8302, https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c8/520?r=0&s=4 (accessed on 6 October 2021). |

| 27 | Quoted in (Podruchny 1995). Medals played a similar role in Crown/First Nations diplomacy. The medal given to Peguis by Lord Selkirk was replaced three years later by Selkirk’s estate because Peguis had used the first one to quell a disturbance. “Last spring War parties assembled to bar the road… through the Sioux country. I gave my flag and two medals to stop them and succeeded. I have now no mark of a Chief and request my father [Selkirk] to replace them. Father, I have told you the truth & I have done and remain thy dutiful son. Signed, Peguis, Colony Chief”. This letter was written 12 June 1821 to Andrew Colvile, one of the executors of the Selkirk estate on behalf of Peguis. In the topmost corner of the letter, there is a note that “Pegouise, Indian, A new flag and medal will be sent to him”. ff 7309–7310, Library and Archives Canada, Selkirk Papers, https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c7/699?r=0&s=3, accessed on 20 February 2021. |

| 28 | Alfred Gell argues that, “Since the outset of the discipline, anthropology has been signally preoccupied with a series of problems to do with ostensibly peculiar relations between persons and ‘things’ which somehow, ‘appear as’ or do duty as, persons” (Gell 1998, p. 9). |

| 29 | Wawezhi’owag means proud in a good sense, like an Elder who is sure of his gifts. See (Matthews 2016, pp. 1212–213). Roger and Doreen Roulette, May 2021. |

| 30 | It could be argued that this is a stretch, but when you consider that Vaidman describes the many worlds interpretation of quantum physics as implying that “There are many worlds existing in parallel in the Universe” and goes on to say that “in every world sentient beings feel as “real” as in any other world” and that “ In this world, all objects which the sentient being perceives have definite states, but objects that are not under observation might be in a superposition of different (classical) states”, he does seem to be describing the Anishinaabe idea of multiple worlds in a “unified spatiotemporal world” as Hallowell puts it (Hallowell 2010, p. 468; Vaidman [2002] 2021, chp. 2.1, 3.6). Vaidman laments the fact that language is insufficient to express these ideas, but for an Anishinaabemowin speaker, multiple worlds are a given and speakers are comfortable in an open-ended state of being that Mary Black Rogers describes as “percept ambiguity” (Black 1977) and at ease with a world in which possibilities are open. |

| 31 | One of the museum’s medals, a Treaty No. 6 medal, was recently repatriated to Red Pheasant First Nation in Saskatchewan. During the speeches which accompanied the repatriation, the current (2021) Treaty Relations Commissioner of Manitoba, Loretta Ross talked about the Treaty No. 6 medal in this way, telling the people that before the medal returned to them, it had been a teacher, educating the visitors to the Manitoba Museum about how we are all treaty people. July 2019. |

| 32 | The exhibit includes a medal for the Dakota who have no treaty with Canada but made treaty with the Anishinaabeg in the area. When they returned in the 1860s to reclaim former traditional territory, they presented medals to English officials that they had been given by British Army officers in the War of 1812. |

References

- Appadurai, Arjun, ed. 1986. The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berens, William. 2009. Memories, Myths and Dreams of an Ojibwe Leader: William Berens, as Told to, A. Irving Hallowell. Edited by Jennifer S. H. Brown and Susan Elaine Gray. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bird-David, Nurit. 1990. The Giving Environment: Another Perspective on the Economic System of Gatherer-Hunters. Current Anthropology 31: 189–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird-David, Nurit. 1999. “Animism” Revisited: Personhood, Environment, and Relational Epistemology [Comments]. Current Anthropology 40: S67–S91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Black, Mary B. 1977. Ojibwa Taxonomy and Percept Ambiguity. Ethos 5: 90–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boas, Franz. 1896. The limitations of the comparative method of anthropology. Science 4: 901–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]