Abstract

Birth is the beginning of a new life and therefore a unique life event. In this paper, I want to study birth as a fundamental human transition in relation to existential and spiritual questions. Birth takes place within a social and cultural context. A new member of society is entering the community, which also leads to feelings of ambiguity and uncertainty. Rituals are traditionally ways of giving structure to important life events, but in contemporary Western, secular contexts, traditional birth rituals have been decreasing. In this article, I will theoretically explore the meaning of birth from the perspectives of philosophy, religious and ritual studies. New ritual fields will serve as concrete examples. What kind of meanings and notions of spirituality can be discovered in emerging rituals, such as mother’s blessings or humanist naming ceremonies? Ritualizing pregnancy and birth in contemporary, secular society shows that the coming of a new life is related to embodied, social and cultural negotiations of meaning making. More attention is needed in the study of ritualizing pregnancy and birth as they reveal pluralistic spiritualities within secular contexts, as well as deeper cultural issues surrounding these strategies of meaning making.

“Childbirth is one site at which personhood gets negotiated and enacted.”(Kaufman and Morgan 2005, p. 322)

1. Introduction

Birth is the first transition in every human life. Birth is, first of all, a biological process. The baby develops throughout pregnancy in a female body. During birth the baby is transitioning into an organism out in the world. However, birth is not just a biological act. It is surrounded by many social and cultural meanings as well. Giving a name to the baby, for instance, is the social acknowledgement of that new living “thing” as a person. Though we cannot remember our own birth, those who were present at our birth can share their memories and stories about our beginning. Birth is a socio-cultural life-passage, which means that by the coming of a new child, not only the baby transitions into a new state, but also the mother, father, brothers, sisters, grandparents, uncles, aunts, and so on, transition into a new social role.

The coming of a new human being is related to expectations and meanings from society. While it is a unique individual who comes into to the world, the newcomer is also a new member of society. Similar to other life passages (such as adulthood, marriage or death), considering birth as a social transition means that the pre-status or social order is temporally in a state of liminality (Turner 1969; Van Gennep 1960). The social order is in a state of temporal anti-structure or chaos. Parents-to-be are preparing mentally, materially or even spiritually for the coming of their child and the transition into becoming parents. Family members and friends are searching for their new roles in the life of this new human being. Experiencing the birth of a baby can be related to feelings of happiness and joy, as well as ambiguity and uncertainty. The coming of a new member of society has been traditionally marked by rituals. Birth is therefore understood as the first rite of passage in a human life (Van Gennep 1960).

A literature review of previous research has shown that pregnancy and birth reveal many existential questions and notions of spirituality (Prinds et al. 2014). Recently, research has increasingly been focusing on spirituality at the start of life (Crowther and Hall 2018; Crowther et al. 2014a, 2020; Wojtkowiak and Crowther 2018; Prinds et al. 2016). In line with Davis-Floyd (1992), many authors have been contributing to the understanding that pregnancy and birth are highly ritualized in Western, secular contexts (e.g., giving a name to the baby, keeping the sonogram as a memorial object, sending a birth card) (Burns 2014, 2015; Cheyney 2011; van Gysgem 2017; Freedman 2011; Prates et al. 2018; Reed et al. 2016). Interestingly, there is, however, not one collectively shared ritual or ceremony that acknowledges the transition into new life in Western secular societies. At the other end of life’s spectrum, death, a funeral is held for everyone who dies, whether one is religious or not. Atheists and the religiously non-affiliated are buried or cremated and the event is accompanied by a collective ritual. At birth, we do not see the same ritual significance in Western society. We do observe, however, the emergence of new, alternative ceremonies at the start of life, such as a “blessingway ceremony” or “mother’s blessing”1 (Burns 2015) and humanist or secular naming ceremonies for babies (Gordon-Lennox 2017; Wojtkowiak et al. 2018). In this article, I will study meaning making and spiritualty at the start of life from a ritual perspective. I will study notions of spirituality at the start of life and explore new ritual fields, such as these emerging ceremonies.

The research question is: what can we learn from ritualizing pregnancy and birth about notions of spirituality at the start of life in contemporary Western, secular contexts? The focus is explicitly on secular or semi-secular contexts, and not on religious rituals (such as baptism) in order to reveal new cultural tendencies and strategies of meaning making. The method to answer the research question is an explorative, theoretical review of existing literature on spirituality, birth and ritual. The literature comes mainly from philosophy, sociology and ritual and religious studies. Two examples of new ceremonies will be described in order to illustrate how rituals reveal strategies of meaning at the start of life. The first example, the mother’s blessing (Burns 2015), is a re-invented social ritual for pregnancy. The second example, humanist naming ceremonies for newborns, ritualizes the birth of a baby. Both rituals are re-invented from traditional ritual and have been re-discovered in secular societies.

In order to answer the main question, first, I will start by discussing some philosophical perspectives on pregnancy and birth and focus on the concept of natality and embodiment. Both are meaningful at the start of life and shed new light on understanding existential and spiritual questioning at the start of life. Second, I will describe the changing ritual and social contexts of birth in Western, secular societies. Then, I will unravel the term “spirituality” in relation to birth. Fourth, I will describe two examples of emerging rituals: the mother’s blessing and humanist naming ceremonies. Finally, the article will end with discussing the insights from this analysis on ritualizing pregnancy and birth and notions spirituality at the start of life.

2. Philosophical Perspectives on Pregnancy and Birth

Birth and death are both fundamental human experiences. Every living being is born and will die. However, only about 50% of the population gives birth. Only women or people with a female biological reproductive system can be pregnant and give birth to a baby. This biological fundament excludes male bodies from the experience of carrying a child in their bodies. Nevertheless, both women and men are always in relation to their own birth. Everybody is born. Then, most people experience the meaning of the birth of a child, when they become parents, aunts or uncles or grandparents. The biological reality of birth is always related to social and cultural meanings. What is more, as I want to argue here in this article, birth also leads to existential and spiritual questioning. Birth is a fundamental life passage, which means that it is meaningful for the individual and community. A new member enters community and is welcomed and introduced.

Next to the joy and happiness felt at birth (Crowther et al. 2014a), giving birth is related to physical pain. The pain is necessary for the baby to be able to be born. What is more, birth opens up possibilities, which also means that birth is the beginning of endless uncertainties (Arendt 1958). Carrying a baby in one’s body is on the one hand the most intimate experience imaginable and at the same time it is a stranger and yet unknown person who is living inside one’s body (Naka 2016). It is not clear yet who this person is and will be. How will she look like and behave? As Naka (2016) writes, “reproduction consists of giving birth to another being, it is inherently a relation to the Other” (Naka 2016, p. 120). Pregnancy and childbirth, next to the joy, celebration and happiness, also bring forward ambiguous and uncertain feelings (Wojtkowiak and Crowther 2018), such as ‘what kind of mother or father will I be?’, ‘what kind of person will my child become?‘, ‘will I be a good parent?’ or ‘do I want this child to be born?’. These types of profound questions that parents (to be) might ask themselves reveal moral and existential questioning. In other words, these are questions of meaning.

In Western philosophy, understanding, analyzing and theorizing pregnancy and birth as existential fundament have, especially compared to death, been largely neglected (Prinds et al. 2014; Wojtkowiak and Crowther 2018; Schües 2008; Hennessey 2019). Hennessey (2019) published a book on birth, imagery and ritual and discusses the lack of theoretical foundations of understanding birth as an existential transition. Hennessey (2019) compares the biggest academic publishers and journals in the field of philosophy and religion (e.g., Cambridge University Press, Oxford University Press, Journal of Religion, History of Religions) and found that the term “birth” only constitutes about 25–50% of the number of publications compared to death (p. 10). The term “childbirth” is even less represented with about 1–3% (p. 10). Schües (2008) argues that the lack of philosophical attention towards the subject of birth is related to the societal, everyday understanding of birth (p. 15). This lack of theoretical foundations is striking, considering the fact that every human being is born and therefore has a beginning, in the same sense that every human life has an end. Recently, philosophical studies on the existential meaning of pregnancy and birth have been emerging, unraveling fundamental meanings of this transition (Bornemark and Smith 2016; Hennessey 2019; Schües 2008). It is, therefore, of great importance to reflect on the meaning of pregnancy and birth from an existential and spiritual perspective. What does it mean to be born? And what does it mean to give birth? Studying rituals around pregnancy and childbirth can shed some light on the existential and spiritual negotiations at birth and how humans make meaning of this biological act.

Arendt was one of the first authors who saw birth as existential beginning by referring to the concept of natality, which was originally discussed in her book The Human Condition in 1958. Arendt has put birth at the center of a meaning perspective. Being born means, according to Arendt, not only having a beginning, but being a new beginning. Being a new beginning means that one is able to politically act in the world. Humans are natal beings; they can initiate and influence the world. Birth is thus a biological fact that directly influences one’s identity and meaning in life. Arendt was one of the first thinkers who gave a more positive outlook on birth. Previously, in classical philosophical literature, birth was seen as an unfortunate coincidence (Schües 2008, p. 31ff). The eternal soul was seen as being trapped in a mortal body (which manifests at birth) or birth was only seen as meaningful in terms of the birth of one’s ego or ratio. Natality, which manifests at our biological birth, focuses on the human potential for action and the possibility to change the world. Arendt makes her point clear in relation to death: “Action, with all its uncertainties, is like an ever-present reminder that men, though they must die, are not born in order to die, but to begin something new” (Arendt 1958, p. 246). The beginning of a new human being is grounded in the relation. We are always in relation to our own birth and therefore to the person who gave us life.

This is why the study of rituals surrounding birth is of great interest. In rituals, natality and the relationship between the newborn and her parents, family or community are re-negotiated. In rites of passage, the social transition is marked by the use of ritual symbols and language. In Western, secular societies, we see a new interest in ritualizing birth, such as the baby shower, gender reveal or “baby-party” (when family and friends are all invited to visit the baby for the first time). However, these ritualizations are, first of all, a personal choice, hence not a collective obligation. It is not clear yet to what extend these forms of ritualizing address a deeper layer of meaning or even spirituality. A baby shower or gender reveal are probably meaningful to the parents and those involved, however, the question is: to what extend do new forms of ritualizing, such as a baby shower, differ from a “party”2?

Johnson (2008) argues throughout his book The Meaning of the Body that there has been a lack of theoretical reflection on embodied meaning making in Western philosophy. Johnson discusses, among others, thinkers such as Dewey and Merleau-Ponty in order to develop a perspective on meaning making that does not separate the body from mind but connects them. According to this view, we should rather speak of an “embodied mind” or “phenomenological body” for the understanding of how humans make meaning in the world (Johnson 2008). He furthermore argues that philosophical thinking needs to acknowledge aesthetics as a way of thinking and making meaning in the world, instead of setting aesthetics apart into solely the field of arts and culture.

Rituals are by all means embodied enactments of meaning and therefore most interesting as examples of meaning making and embodied spirituality. What is more, rituals aesthetically translate reality into symbolic form (Wojtkowiak 2018). Rituals create a reality that is at aesthetic distance to the actual experience. Rituals give room to feel emotions and identify with the experience, but at the same time create some distance to the actual experience through symbolic enactment. Rituals thus do not represent the world as it presents itself to us, but as we imagine it. In a ritual we can imagine a world, which through symbolic actions becomes temporally our actual world (Geertz 1973). Furthermore, Crossley (2004) argues that rituals are a “form of what Marcel Mauss (1979) has termed “body techniques”” (p. 33), defined as “(culturally) specific uses of the body” (p. 33). Crossley explains that body techniques does not mean that the body is used as an object in the world, but, in line with Merleau-Ponty, inhabits the world. Embodied experience is seen as a “practical and pre-reflective knowledge and understanding” (Crossley 2004, p. 37). This means, similar to what Johnson (2008) states, our bodies are a source of knowledge and understanding of the world. Studying rituals at the start of life, thus, teaches us about how we give meaning to the world, including the role of the body in meaning making. In pregnancy and birth, the embodied reality of carrying and birthing a child is very prominent.

3. Ritual Meanings of Pregnancy and Birth in Western Society

Rituals are ways of giving structure to uncertainties and ambiguous feelings, while at the same time they can destabilize the status quo and existing group identities (Grimes 2014; Bell 1997). Rituals can be of guidance during existential questioning, prescribing a specific embodied and spiritual “infrastructure”. For instance, baptism guides parents with certain spiritual rules and moral values, which is experienced and strengthened through participating in a baptism ritual. The baby is blessed and welcomed into a religious community. At the same time, using Grimes’ (2002) words, a ritual, “unlike an ethical principle, can thrive on ambiguity. A rite can acknowledge the seriousness of the act […] without having to resolve the moral issues.” (p. 315). Ritual can be of moral orientation, but this does not mean that it always prescribes them explicitly. What is more, in societies where traditional rituals are not common anymore, these moral and social guidelines become more vague or pluralistic and new ways of meaning making are enculturated, for instance, the increasing interest in parenting literature. Bookstores and the internet are filled with advice on how to care for and raise a baby. While the existing and growing knowledge on care for a child is a source of guidance, it can also lead to even more insecurity, due to many contrasting pieces of advice. What is more, rational or scientific knowledge does not necessarily give answer to existential questions.

In contemporary Western societies, the context of birth has been greatly influenced by sociological and technological changes (Conrad 2007; Davis-Floyd 1992). Birth rates in Western societies (as well as other industrialized societies) have been decreasing steadily (Kiernan 2004). Fewer children are born, mothers and fathers become parents at an older age and parenthood is more or less a personal choice. The “Western way” of birthing has been mainly influenced by medicine and technology (Davis-Floyd 1992).

In Western society, pregnancy and birth were not shared publicly, in most cases not even with the father-to-be who was not allowed to be present during the birth for a long time. Only in the last 30 years or so, pregnancy and birth have become more visible in our society. The image of the nude and pregnant body of actress Demi Moore on the cover of Vanity fair in 1991 was shocking at the beginning, but started a movement and more celebrities started to show off their “baby bumps” in the media.3 Women’s fashion started to also change and maternity clothes made the pregnant belly more visible. The pregnant belly became something to be proud of and not something to hide. This new visibility of pregnancy brought new ideals of motherhood: a mother should look a certain way (Prinds et al. 2020). On the internet, birth photography and the sharing of birth stories have been trending within the last years, making pregnancy and birth more visible.

What is more, traditional religious rituals have been decreasing in Western, secular societies. Since the 1970s, baptism has been decreasing steadily in many Northern and Western European countries (Alfani 2018). To give an example: in the Netherlands, which is a strongly secularized society, approximately 21.5% of the population consider themselves Catholic.4 In 2018, 10,380 babies were baptized in the Catholic community the Netherlands, which is 6.24% of all babies born in that year. In Belgium, 45% of all newborn are baptized, significantly more than the Netherlands, but the trend shows a steady decrease between 2010 and 2016 with −34.5%.5 In Sweden, 44% of babies were baptized in 2016 and in France, between 2010–2013, an average of 37% of babies were baptized (Alfani 2018). While baptism remains common in some countries, such as Poland (100% in 2015) and also Italy (with 79% in 2015), we see that in many Northwestern European countries the percentages decrease. These statistics show us that depending on the country a baby is born, choosing this collective religious rite may be a personal choice and the trend shows a decrease. In Northwestern European countries, the majority of babies are not baptized. It is yet unclear to what extent alternative ceremonies are offered or whether parents do refrain from any. In comparison, after death, a funeral or some form of body disposal is necessary and families can choose what kind of rituals accompany the funeral. In the case of birth, there is not a direct necessity to have a social gathering or collective ceremony to announce the birth of a baby.

Grimes (2002) notices that in contemporary Western, secularized societies, birth is more a passage, rather than a rite of passage, due to the lack of collective rituals around pregnancy and birth. Davis-Floyd (1992) has contributed an important perspective to our understanding that birth in Western societies is also highly ritualized within a medical setting. In her well-known book Birth as an American Rite of Passage, she argues that medial practices in hospitals are also significant practices of ritualizing birth. Western medicine and technology have become prominent, not only in the care for the pregnant and birthing woman, but also in the way we give meaning to birth. Other authors have followed Davis-Floyd and further discussed the ritual dimension of pregnancy and childbirth (McCallum and dos Reis 2005; Cheyney 2011; Burns 2014, 2015; Jacinto and Buckey 2013; Freedman 2011; van Gysgem 2017). There are, however, different modes or densities of ritual (Grimes 2010, 2014). Daily ritualizations, the participation in a social ceremony or liturgy, represent a different ritual layer. Ritual in medical settings has ritual aspects but differs form a ceremony that is intentionally marked as a social gathering and puts attention towards a specific life-event. All ritual layers are significant in enculturation and meaning making. However, the absence of ritual ceremony at the start of life is striking and brings us to the later described two examples.

4. Spirituality at the Start of Life

Spirituality at the start of life has been gaining attention in the literature (Callister and Khalaf 2010). Crowther has written extensively within the last years on the importance of acknowledging spirituality at the start of life (Crowther and Hall 2015, 2018; Crowther et al. 2014a, 2014b, 2020). Ignoring the subject of spirituality at childbirth neglects a fundamental aspect of humanity and care practice as well. Similar to end of life care, the beginning of life also deserves focus and attention regarding questions of meaning and spirituality (Wojtkowiak and Crowther 2018). Crowther et al. (2020) define spirituality as “an aspect of our lives that brings meaning, sense of purpose, unifies our life narrative, feelings of interconnectivity and of deepening relationships with self and others (‘others’ being seen and unseen). It may be connected to religion and a belief in a quality of divinity but not necessarily. Spirituality is part of our wellbeing and includes psychological, emotional and cultural aspects of being and becoming” (Crowther et al. 2020, p. 2). McGuire (2008) writes that material bodies are linked to spirituality through “healing, sexuality, and gender, through fertility, childbirth and nursing, and a myriad other forms of embodied practices” (McGuire 2008, p. 118). Ammerman (2010) describes spirituality in pluralistic terms, not necessarily being experienced in either religious or secular terms, but often a mix of them.

Ammerman (2010) defines spiritualty in five dimensions. First, spiritualty refers to a moral dimension in terms of what people experience as the good and what is distinguished as right or wrong (Ammerman 2010). Second, spiritual experiences come forward when people feel awe, wonder and beauty in the world. This refers to majestic experiences. Third, spirituality is found in the mysterious: experiences that we cannot explain. Fourth, spirituality brings forward a connection with others that goes beyond the boundaries of one’s self (Ammerman 2010; Knoblauch 2009). A spiritual connection goes beyond the self, such as in unification or loosing oneself within the other. Finally, questions of meaning are also found in spiritual experiences: asking yourself, what is the meaning of this life event? A spiritual experience is something that we cannot grasp, that is out of the reach of rational and scientific explanations, which perhaps explains the fuzziness of the concept (Watts 2020).

What can we learn from rituals in understanding meaning and spirituality at the start of life? A survey study (n = 517) in Denmark, a secular society, revealed that 65% of first-time mothers pray during their pregnancy (Prinds et al. 2014). However, only 33% believed in God and 37% in a higher power (Prinds et al. 2016). The most common reported forms of prayer were an inner dialogue with God (46%) or an inner dialogue addressing something greater than the self (40%). Only 26% of mothers prayed in the context of a church. These descriptive statistics reveal a tendency of existential and spiritual search for meaning and contemplation among new mothers. From a literature review, we learn that in the reported empirical studies across the world, women describe many references towards meaning making and spirituality in relation to becoming a mother (Prinds et al. 2014). Mothers describe the birth of their child as the “most significant thing I have ever done” (p. 737) or a deep connection with previous generations, as well as something that goes beyond a rational understanding. Other research shows similar results referring to birth as a deep transitional experience (Crowther and Hall 2018). When linking these results to the previous description of spirituality, we recognize all of the previously described notions of spirituality emerging at childbirth.

In Table 1, the five notions of spirituality by Ammerman (2010) and others (Knoblauch 2009) are described in relation to the start of life. The different notions of spirituality, such as the moral, majestic, mysterious, unification and questions of meaning, are not necessarily separative dimensions but contemplative. For the sake of clarity, I have stated them as separate notions, but in reality, they do cross-over. The examples are meant purely as illustration, not as a complete or fixed description of spirituality at the start of life. In the next section, I will further investigate these notions from a ritual lens, by analyzing two cases.

Table 1.

Spirituality at the start of life.

5. Re-Inventing Rituals of Pregnancy and Childbirth

In the following section, two examples of emerging ceremonies will be described in order to explore the earlier notions of spirituality within more concrete examples. The first example is called the “blessingway ceremony” or “mother’s blessing”, referring to a blessing of the mother-to-be during her pregnancy (Burns 2015). The second example are secular, humanist naming ceremonies where the baby is welcomed into community. Both examples will be described from existing literature (Burns 2015; Gordon-Lennox 2017; Wojtkowiak et al. 2018) and additional information found on websites, such as blogs, newspaper articles and secular celebrant institutes across the world (US, Northwestern Europe, Australia and New Zeeland).

Both rituals would, according to Grimes’s (2010) typology, be described as ceremonies (p. 38). Grimes (2010) differentiates ceremonies from other modes of ritual, such as ritualization and decorum, as more intentional and on a larger scale6. A ceremony has an invitation and a specific date and time. The differentiation of these modes is important, according to Grimes (2014, p. 203ff), as they reveal a specific ritual density or layer. Ceremonies are enforced and declarative and thus make a social statement about what matters within a group. They ask for ritual actors to participate in the ceremony.

By describing these two examples, I aim to unravel some existential and spiritual needs surrounding pregnancy and birth in secular and pluralistic contexts. The earlier discussed philosophical and spiritual themes are meant as theoretical foundations for these case descriptions. The mother’s blessing is chosen because it tells us something about ritualizing pregnancy (the separation of the mother from her earlier social status). The naming ceremony can reveal something about integrating the newcomer into community.

5.1. Ritualizing Pregnancy: Mother’s Blessing

The mother’s blessing is inspired by the traditional Native American Navajo blessingway ceremony (Biddle 1996). Biddle conducted an ethnographic study at a Navajo reservation and interviewed 56 women of whom 14% had had a blessingway. Traditional blessingway ceremonies consist of singing, chanting and sharing stories to wish beauty, good and harmony to the mother-to-be.7 The songs and stories are shared during pregnancy and childbirth. The singer, who is a traditional medicine man, performs the songs. Biddle (1996) explains:

The songs and stories are important for the mother-to-be and shape her view of childbirth and family life. Through the chants the woman is spiritually connected to her ancestors and the past and future (Biddle 1996, p. 22).“The Blessingway relates back to the legends and therefore establishes a connection with them and with the world today […] Wyman explains the translation of the word Blessingway, “Hozhoonji”. The stem, “Hozhen”, is like the Greek “arete”, which is usually translated as excellence, but covers all forms of human excellence and implies an ideal of wholeness and harmony. The Navajo term includes everything that a Navajo thinks is good... concepts such as the words beauty, perfection, harmony, goodness, normality, success, well-being, blessedness, order, ideal do for us. The ending, “-iji”, expresses in the direction of, side, manner, way, and so we translate the name as Blessingway.”.(p. 20)

A new type of mother’s blessing has been ritualized within secular contexts. The ritual reveals pluralistic elements. It does not “demand” a specific worldview or spiritual background but has references towards different religious or cultural rituals. The name and concept have been taken from the Navajo tradition. What is more, some mother’s blessings can include an “altar” being made for the mother or Henna tattoo belly paining. Henna tattoos are traditionally used in wedding rituals in South Asian, Middle Eastern, and North African cultures.

A modern mother’s blessing is described as a “celebration of a woman’s transition into motherhood that’s rooted in Navajo culture. It is a spiritual gathering of the woman’s closest friends and family who come to nurture the mama-to-be with wise words, positivity, art and pampering.”8 During a mother’s blessing the mother is blessed by other significant women before the baby is born. Most of the time, the other participants are her mother (in law), sister(s), aunts and friends. However, variations are possible and sometimes males are also present. Although mother’s blessings still appear in the margins, they are growing in popularity, spreading around Western societies, such as the UK9, USA10, The Netherlands11, Belgium12 and Germany13.

From an Australian interview study with 30 women who had planned or underwent a mother’s blessing during pregnancy it was revealed that the ritual is seen as a conscious choice against the mainstream baby shower (Burns 2015). During a regular baby shower, material gifts are given to the mother, which are intended for the baby. The interviewed women in this study explained that they did not connect to the meaning or purpose of a mainstream baby shower and they missed a meaningful exchange. They claimed to not be looking for “just gifts” and “silly games”. Another difference is that the mother-to-be is at the center of the ceremony and not the baby. During the ceremony, symbolic gifts are given to the mother in the form of wishes, symbolized by beads, which are then threaded into a cord or string. The beads and wishes are brought in preparation of the ritual. The giving and threading of beads is the central moment of the ceremony and enacts the blessing of the mother.

The focus on female participants during a mother’s blessing stresses the importance of gender-focus in this pregnancy ritual. Although men also experience birth as a significant life passage, the biological and embodied aspect of pregnancy and birth are shared among women or persons with a female reproductive system. Perhaps this is why during this ritual the presence of other females is preferred. Excluding men from this ritual stresses the importance of a gendered, female community. McGuire (2008) quite rightly states that “spirituality involves people’s material bodies, not just their minds or spirits” (p. 97). Within the temporal space of the mother’s blessing, women’s material bodies, with the pregnant body at the center, as well as material, ritualized objects, embody “the sacredness of the divine” (McGuire 2008, p. 791). The body of the pregnant mother-to-be is ritualized in many ways, such as combing her hair, massaging her shoulders, washing her feet and belly painting.

As pregnancy is a significant and irreversible bodily transition, the woman carries the baby that is growing inside of her, the embodied meaning of pregnancy is stressed in the ritual. Burns (2015) acknowledges that she was unsure about using the term “feminist spirituality” in interpreting her data, but the interviews reveal that the presence and participation of the female group is of great importance. Statements such as “I wanted that feminine energy” (Burns 2015, p. 788), which is not seen as a reaction against male presence (“I’ve got some beautiful men in my life, but I just wanted an afternoon of feminine energy” (Burns 2015, p. 788)) stress the role of the importance of a female community.

What is more, the ritual starts with matrilineal introductions: each woman introduces herself in terms of her maternal line, such as “daughter of”, “granddaughter of”, etc. The matrilineal introductions enact the female community beyond the physically present or living female relatives and can go back to female ancestors. Beginning the ritual with this introduction round immediately states the ritual space within a transcendent, inter-generational meaning. This is in line with what Schües (2008) explores as the generative meaning of birth: every birth, although unique in itself, is related to what has come before and will come after. The baby is born into a world that already exists. It is a new beginning within an existing community. Birth is always relational.

Other rituals during the mother’s blessing are painting on the pregnant belly, belly plaster casting and wrist weaving (a ball of wood is passed along and wrapped around one’s wrist sharing some words about the symbolism of this connection). Most of these rituals are taking place sitting (on the floor in a circle), which creates an intimate space among the participating women.

During the mother’s blessing, the female participants are not passive observers, but they actively enact their relationship with the mother-to-be. The central moment of the ceremony, the symbolic gift giving and stating of wishes, points at negotiating the uncertain future of the mother-to-be. A female community is enacted through the different rituals that are part of the mother’s blessing. The blessing is an enactment of what people wish as good and beautiful to the mother.

Birth, same as death, is a mysterious event. As described earlier through the concept of natality (Arendt 1958), birth is the beginning of new possibilities. Pregnancy is a relationship with a “stranger” within one’s body. In this ritualizing, we see negotiations of what the community wishes for the mother and baby. As birth is a transition and new beginning, during this ritual the participants give a glimpse of what they wish the unknown future to be, hence the ritual being a reaction to the mysterious and unknown. Stating a wish also has a moral dimension: what you think is good is what you wish to somebody else. The entire ceremony is accompanied by food and other delicious threats, the mother-to-be, as well as the other participants, dress up, for example, using flowers as decoration in their hair. The beautiful attributes express a relation to the majestic. The wishes that can refer to beauty and positivity also refer to the majestic.

5.2. Ritualizing Birth: Secular and Humanist Naming Ceremonies

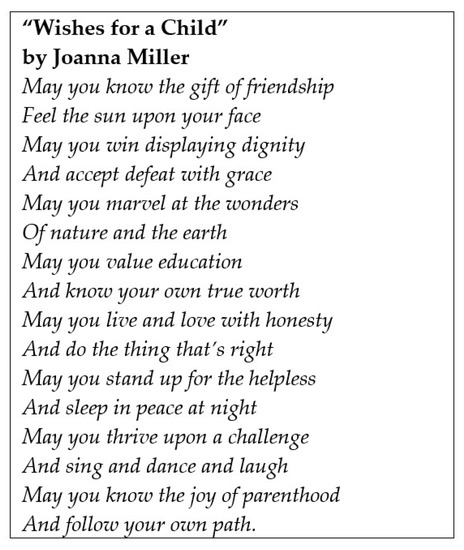

In Western contexts we also see the emergence of secular or humanist naming or welcoming ceremonies for babies. This ritual, inspired by traditional baptism, is a re-invented way of welcoming the baby into one’s community. European humanist organizations, such as Humanists UK14 or the Norwegian Humanist Association15, offer this ceremony as an alternative to a traditional, religious baptism. The motivation for a baby naming is described as “[p]eople choose to have a humanist naming ceremony because they want to bring family and friends together to celebrate one of life’s key milestones. They are ideal for families who want to mark the occasion in a way that isn’t religious.”16 The ceremony takes between 20 and 60 min and can be accompanied by a humanist or secular celebrant. In the United States, the Celebrant Institute provides celebrants across the country who can create and perform a baby naming.17 A naming ceremony is personalized and uniquely created for each family. Parents and other significant others can, for instance, state their hopes and wishes for the baby. Music and readings can also be part of the ceremony. Some physical symbol might be given to the baby, such as for guidance or something that the child can open or read later in her life. ‘Guideparents’ might be presented to the community and they can also express their wishes to the baby. As this ritual is individually crafted for each family, the location, length, content and other ritual elements are chosen for the occasion. The naming ceremony is presented as an alternative to a religious baptism or christening. On the websites of the secular and humanist celebrant institutes18 one can find ideas and examples from naming ceremonies, such as poems to choose from (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Example of a poem for a humanist naming ceremony.

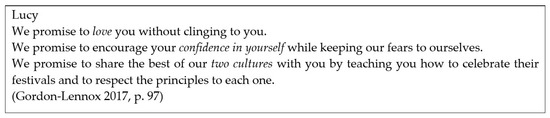

Figure 2.

Example of parents’ promise to baby.

In Norway, where humanist ceremonies are held for about 3.7% of all newborns (a total of 2248 naming ceremonies in 2015)19, the naming of babies is a collective ceremony where a group of babies are named at the same time. The babies are mostly 4 to 12 months old. The parents do not need to be a member of the Norwegian Humanist Association to name their baby in a humanist ceremony. Some parents choose the baby to wear a traditional white baptism dress, which is a reference towards traditional religious baptism, while others choose other clothing. There are no restrictions to what the baby should wear.

Swiss secular celebrant Jeltje Gordon-Lennox (2017) writes that naming ceremonies generally serve two functions: “First of all, the newcomer is publicly received into the group. Second, the group implicitly or explicitly acknowledges its responsibilities for the new person” (p. 94). Gordon-Lennox (2017) further elaborates ingredients for a meaningful ceremony, such as promises, symbolic gestures and music “that are coherent with the values of the parents [which they] want to transmit to their child” (p. 95). Moreover, she advises to include a pledge from the guideparents. She also stresses that it is important to choose material that is sincere, touches people’s emotions and is not “nice for the parents”, such as a classical music piece. Instead, parents should choose music that a child would choose. According to Gordon-Lennox, the newcomer is at the center of the naming ceremony, but in relation to her parents. The other significant people, such as aunts and uncles, grandparents and friends, stand around that relationship between parents and child. An example of parents’ promises can be found in Figure 2.

The description of wishes for Lucy shows that the parents make promises to the child (‘to love and not to cling’) and they position themselves in their intercultural context (‘to share the best of both cultures’). These promises are individually crafted for each child. The naming ceremony is an example of re-inventing a traditional ritual while giving more space for personal choice and preference. Especially when the ceremonies are crafted specifically for one family, such as in the UK or US, parents have lots of options to choose from. Having a collective naming ceremony, such as in Norway, however, underlines the communal aspects of welcoming and celebrating the arrival of a newborn together with other babies and parents. The dynamics between individualism and collectivism become visible in this ritual.

The focus of secular naming ceremonies is on unique wishes and aspects of the self. The newborn is a unique, new person. However, at the same time, the choice for a naming of the baby in a family setting acknowledges the importance of community in the baby’s life. The newcomer is acknowledged within a social group. The stating of promises of parents and guideparents are examples of how the good life is ritualized in the naming ceremony. Parents choose what kind of elements they think are meaningful, such as music, text or a physical symbol. Therefore, the naming ceremony also reveals ritualized strategies of giving meaning to birth and this new life, as well as notions of spirituality. The wishes for the baby express a search for meaning and confrontation with the mysterious, as well as moral obligations. What we consider a good life is what we wish for the baby. Furthermore, the ceremony shows the importance of responsibility in the life of the baby, also revealing one’s social bond to the baby. Becoming a guideparent gives the person a special role in the baby’s life. During the ceremony this role is enacted among family and friends. A naming ceremony is a celebration: it focuses on the joyful aspect of a child coming into the world. At the same time, there is also space for seriousness and reflection, which makes this social gathering different from a party. Having a naming ceremony, presenting the newborn to society or one’s community, is possibly a way of dealing with the unknown or mysterious aspect of spirituality at birth: the baby’s future is yet unknown. This little person is still a stranger, but by expressing one’s values and wishes for the future, giving her a name and acknowledging her relationships and status in the community, this unknown future becomes somewhat more concrete and is established in relation to others. The naming ceremony illustrates how natality (Arendt 1958) is enacted into symbolic form. The newcomer, the baby, is celebrated by her community, and the new roles in the life of the child, such as parents and guideparents, enact their roles in the life of this new member of society. The relationship with this yet unknown person is made more concrete and tangible. Parents have the opportunity to state what their wishes for her future will be and how they hope their relationship will develop.

6. Discussion

The question of this article was: what can we learn from ritualizing pregnancy and birth about notions of spirituality at the start of life? First, I discussed some philosophical perspectives on birth. Mainly, natality and embodiment were discussed in relation to meaning making and the changing ritual and social-cultural contexts of birth in Western, secular societies. A discussion of Ammerman’s (2010) notions of spirituality in relation to birth has shown that birth is related to fundamental existential and spiritual questions. The descriptions of emerging rituals, the mother’s blessing and naming ceremonies, furthermore, showed expressions of spiritual questions.

Analyzing these two cases brings forward the importance of understanding the role of embodiment in meaning making of pregnancy and birth. The here described cases of ritualizing pregnancy and childbirth show the importance of the use of body techniques in creating meaning for new life (Crossley 2004). During a mother’s blessing the body of the pregnant mother-to-be is pained on or the belly is casted. The sitting in a circle with a group of females puts the bodies of women at the center of a shared, intimate space. In order to participate in a mother’s blessing, one needs to possess specific “embodied cultural competencies” (Crossley 2004, p. 35), which means (1) having a significant bond with the mother-to-be, (2) being a female or having a female body and (3) being pregnant (in case of the central actor). During the mother’s blessing, the pregnant body is central in the ritual action. In the naming ceremony the embodied presence of the baby is also at the center: it is of importance that the baby is physically presented to the world. People want to hold the newborn, which gives them a sense of significance in their relationship with the baby. As birth is the beginning of new life, these new rituals also enact this new beginning by presenting hopes and wishes for the future, which represents the meaning of natality (Arendt 1958).

Both ceremonies are social gatherings at the start of life. One during pregnancy and the other after the baby is born. The wishes and promises that are symbolically enacted during the ceremonies show that the pregnant mother and the newborn are acknowledged by the social group. The pregnant woman and the fetus are both in a state of liminality (Turner 1969). They are in transition. The social acknowledgement of the mother and baby manifests at birth. Through ritual action this new, unstructured state is made more tangible. The mother’s blessing reveals notions of communitas: an equal, temporal, cohesive sense of togetherness (Turner 1969). The mother’s blessing focuses strongly on a specific population or group and the present women participate actively and equally during the different ritual parts of the ceremony. The sitting in a circle or the floor embodies this equal state. Research by Burns (2015) has shown that the female community is an important element in this ritual. To be able to interpret in greater depth to what extent notions of communitas and spirituality are experienced during these re-invented rituals would ask for a more in-depth interview study. In an ethnographic or interview study one can ask more specifically about the extent to which women do experience the mother’s blessing as spiritual.

An interesting, or perhaps even paradoxical, characteristic of these newly emerging ritual fields is that the social gathering is often personally chosen by the mother-to-be or the parents. This differs from traditional ritual, which is embedded and embodied in the community. These new rituals are introduced by those who are at the center. The community that is enacting the ritual needs to learn and embody the ritual, often for the first time. It would be interesting to investigate more how these new forms of ritualizing influence notions of communitas. A ceremony is an intentional social interaction, but to what extent does it ‘succeed’ within these new ritual fields?

Re-inventing pluralistic ritual also brings forward complex and sensitive questions about cultural exchange. Analyzing the mother’s blessing, which in many descriptions is referred to with the traditional term “blessingway ceremony” and the openness towards how it is inspired by a specific culture, the Native American Navajo (Biddle 1996), ponders to what extent we need to discuss the topic of cultural appropriation.20 One of the websites describing mother’s blessings says: “Out of respect for the Navajo I will use the name blessingway”21, but also, “The Navajo don’t approve of the name being used”.22 Another article explicitly uses the term “cultural appropriation” in discussing this new ritual: “It’s also is the perfect opportunity to engage in meaningful research and discussion on the topic of cultural appropriation. Be aware of the language you use and whom it belongs to and consider where certain rituals originate. Talk to the people whom they belong to, respect them and pay them if appropriate.”23 The author also states that already in 2004 Navajo feminists had drawn attention towards their dissatisfaction with the term being used in this new ritual context and that they rather suggest the term “mother’s blessing”. Another blogger who describes her experiences with her mother’s blessing writes that she believes it is possible to be inspired by indigenous ritual, but also that “we must never commodify it, or use it tokenistically”.24

Cultural appropriation is a complex issue, broadly defined as “the use of a culture’s symbols, artefacts, genres, rituals, or technologies by members of another culture” (Rogers 2006, p. 474). What is most important in understanding cultural appropriation is that it happens when there is a power distance or power relation. Cultural exchange, defined as “the reciprocal exchange of symbols, artifacts, rituals, genres, and/or technologies between cultures with roughly equal levels of power” (Rogers 2006, p. 477), is an ideal version of multi-cultural exchange. However, in the case of the mother’s blessing we may rather speak of cultural dominance, defined as “the use of elements of a dominant culture by members of a subordinated culture in a context in which the dominant culture has been imposed onto the subordinated culture, including appropriations that enact resistance.” (p. 477). As Native Americans have been forcefully repressed by the White dominant culture, it is striking that today these traditional rituals are re-used by the same cultural group that has been repressing the culture in the first place. The subject of cultural appropriation remains complex and might not be solved with a short statement such as “this is not allowed”, but in ritualizing and re-using and re-inventing rituals in Western societies, we need to discuss the topic of cultural appropriation more. What is ethical ritualizing? What can be used in new rituals and what requires deeper thinking and more ritualizing? Grimes argues in an interview with Gordon-Lennox to not use the foreign and exotic in new rituals but to use what you are familiar with. Grimes states: ritualize “with the stuff in your drawers” (Gordon-Lennox 2017, p. 52). I think that the topic of cultural appropriation deserves more attention in ritual studies literature, when analyzing and discussing re-inventions of existing rituals.

Finally, the here analyzed rituals question whether we should speak of secular rituals here. The rituals both reveal references towards existing, religious ritual, such as the white gown during the baby naming or the re-use of traditional elements from other cultures. These new ritual fields express negotiations between the secular and religious, as well as different cultures. We might more accurately speak of pluralistic ritualizing. Rejowska (2020) writes on humanist weddings in Poland: “even when actors try to create a performance from the very beginning, references to some previous conceptions, traditions or particular symbols, are inevitable” (Rejowska 2020, p. 5). On the one hand, secular and humanist ceremonies are a movement against traditional, religious ritual, placing a focus on the individual within a social ritual (see Rejowska 2020). On the other hand, these rituals are clearly inspired by traditional, religious (Christian or native, indigenous) ritual. As Rejowska states, “humanist ceremonies function in a given cultural context and draw inspiration mostly from the Christian tradition” (p. 12). New rituals focus on the individuality and uniqueness of a person, but at the same time they create a sense of community through this ceremonial social gathering and interaction. Ritualizing pregnancy and birth in secular societies reveals what Ammerman (2010) defines as “pragmatic plurality” (p. 156). For the sake of meaning making, people reach out to different sources, some of them secular, some religious.

7. Conclusions

Pregnancy and birth rituals celebrate natality. They enact natality: the newcomer and the new beginning are welcomed and celebrated. Spirituality at the start of life has been found in different notions, from the majestic, to the mysterious, unification and questions of meaning. The here described ceremonies enact and embody strategies of meaning making and spirituality. Birth as a new beginning is a source of embodied spirituality but it is not clear cut or finished. The discussion of ritualizing pregnancy and birth in these new ritual fields is ‘only’ at the beginning. The inter-cultural negotiations in emerging rituals are still ongoing and asking for more dialogue on the topic of ritualizing in pluralistic and secular contexts.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Alfani, Guido. 2018. Baptism and Godparenthood in Catholic Europe. In Yearbook of International Religious Demography. Leiden: Brill, vol. 5, pp. 132–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman, Nancy T. 2010. The Challenges of Pluralism: Locating Religion in a World of Diversity. Social Compass 57: 154–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, Hannah. 1958. The Human Condition. Chicago: Univerity of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Catherine. 1997. Ritual: Perspectives and Dimensions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Biddle, Jeanette M. 1996. The Blessingway: A Woman’s Birth Ritual. Master’s Thesis, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bornemark, Jonna, and Nicholas Smith, eds. 2016. Phenomenology of Pregnancy. Huddinge: Södertörn University. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Emily. 2014. More Than Clinical Waste? Placenta Rituals Among Australian Home-Birthing Women. The Journal of Perinatal Education 23: 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, Emily. 2015. The Blessingway Ceremony: Ritual, Nostalgic Imagination and Feminist Spirituality. Journal of Religion and Health 54: 783–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callister, Lynn Clark, and Inaam Khalaf. 2010. Spirituality in Childbearing Women. Journal of Perinatal Education 19: 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheyney, Melissa. 2011. Reinscribing the Birthing Body: Homebirth as Ritual Performance. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 25: 519–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrad, Peter. 2007. The Medicalizaiton of Society: On the Transformation of Human Conditions into Treatable Disorders. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crossley, Nick. 2004. Ritual, Body Technique, and (Inter)subjectivity. In Thinking through Rituals. Philosophical Perspectives. Edited by Kevin Schilbrack. New York: Routledge, pp. 31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Crowther, Susan A., Jenny Hall, Doreen Balabanoff, Barbara Baranowska, Lesley Kay, Diane Menage, and Jane Fry. 2020. Spirituality and Childbirth: An International Virtual Co-Operative Inquiry. Women and Birth. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, Susan, and Jennifer Hall. 2015. Spirituality and Spiritual Care in and around Childbirth. Women and Birth 28: 173–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowther, Susan, and Jenny Hall, eds. 2018. Soirituality and Childbirth: Meaning and Care at the Start of Life. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Crowther, Susan, Elizabeth Smythe, and Deb Spence. 2014a. The Joy at Birth: An Interpretive Hermeneutic Literature Review. Midwifery 30: e157–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowther, Susan, Liz Smythe, and Deb Spence. 2014b. Mood and Birth Experience. Women and Birth 27: 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis-Floyd, Robbie. 1992. Birth as an American Rites of Passage. Berkley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, Françoise Barbira. 2011. Changing Medical Birth Rites in Britain: 1970–2010. In Birth Rites and Rights. Edited by Fatemeh Ebtehaj, Jonathan Herring, Martin Johnson and Martin Richards. Oxford and Portland: Hart Publishing, pp. 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. New York: Basic Books, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Lennox, Jeltje. 2017. Crafting Secular Ritual: A Practical Guide. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Grimes, Ronald L. 2014. The Craft of Ritual Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grimes, Ronald L. 2010. Beginnings in Ritual Studies. Waterloo: Ritual Studies International. [Google Scholar]

- Grimes, Ronald L. 2002. Deeply into the Bone. Re-Inventing Rites of Passage. Berkley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hennessey, Anna M. 2019. Imagery, Ritual and Birth: Ontology between the Sacred and the Secular. Lanham: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Jacinto, George A., and Julia W. Buckey. 2013. Birth: A Rite of Passage. International Journal of Childbirth Education 28: 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Mark. 2008. The Meaning of the Body: Aethetics of Human Understanding. Chigaco: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, Sharon R., and Lynn M. Morgan. 2005. The Anthropology of the Beginnings and Ends of Life. Annual Review of Anthropology 34: 317–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiernan, Kathleen. 2004. Changing European Families: Trends and Issues. In The Blackwell Companion to the Sociology of Families. Edited by Jacqueline Scott, Judith Treas and Martin Richards. Malden: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., pp. 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Knoblauch, Hubert. 2009. Populäre Religion: Auf Dem Weg in Eine Spirituelle Gesellschaft. Frankfurt am Main: Campus. [Google Scholar]

- McCallum, Cecilia, and Ana Paula dos Reis. 2005. Childbirth as Ritual in Brazil: Young Mothers’ Experiences. Ethnos 70: 335–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, Meredith B. 2008. Lived Religion: Faith and Practice in Everyday Life. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mauss, Marcel. 1979. Body Techniques. In Sociology and Psychology Essays. London: Routledge, pp. 95–123. [Google Scholar]

- Naka, Mao. 2016. The Otherness of Reproduction: Passivity and Control. In Phenomenology of Pregnancy. Huddinge: Södertörn University. [Google Scholar]

- Prates, Lisie Alende, Marcella Simões Timm, Laís Antunes Wilhelm, Luiza Cremonese, Gabriela Oliveira, Maria Denise Schimith, and Lúcia Beatriz Ressel. 2018. Being Born at Home Is Natural: Care Rituals for Home Birth. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem 71: 1247–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prinds, Christina, Niels Christian Hvidt, Ole Mogensen, and Niels Buus. 2014. Making Existential Meaning in Transition to Motherhood—A Scoping Review. Midwifery 30: 733–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinds, Christina, Dorte Hvidtjørn, Axel Skytthe, Ole Mogensen, and Niels Christian Hvidt. 2016. Prayer and Meditation among Danish First Time Mothers—A Questionnaire Study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 16: 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prinds, Christina, Helene Nikolajsen, and Birgitte Folmann. 2020. Yummy Mummy—The Ideal of Not Looking like a Mother. Women and Birth 33: e266–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, Rachel, Jennifer Rowe, and Margaret Barnes. 2016. Midwifery Practice during Birth: Ritual Companionship. Women and Birth 29: 269–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejowska, Agata. 2020. ‘System of Collective Representations’ in Humanist Marriage Ceremonies in Poland. Social Compass, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, Richard A. 2006. From Cultural Exchange to Transculturation: A Review and Reconceptualization of Cultural Appropriation. Communication Theory 16: 474–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schües, Christina. 2008. Philisophie Des Geborenseins. Freiburg and München: Verlag Karl Alber. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Victor. 1969. The Ritual Process. New Brunswick: Aldine Transaction. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gennep, Arnold. 1960. Rites of Passage. Chigaco: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- van Gysgem, Liesbeth Duernick. 2017. Rite for the Introduction and Healing of Women after Childbirth. Currents in Theology and Mission 44: 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, Galen. 2020. Making Sense of the Study of Spirituality: Late Modernity on Trial. Religion, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtkowiak, Joanna. 2018. Towards a Psychology of Ritual: A Theoretical Framework of Ritual Transformation in a Globalising World. Culture and Psychology 24: 460–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtkowiak, Joanna, and Susan Crowther. 2018. An Existential and Spiritual Discussion about Childbirth: Contrasting Spirituality at the Beginning and End of Life. Spirituality in Clinical Practice 5: 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtkowiak, Joanna, Robin Knibbe, and Anne Goossensen. 2018. Emerging Ritual Practices in Pluralistic Society: A Comparison of Six Non-Religious European Celebrant Training Programmes. Journal for the Study of Spirituality 8: 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | I will use the term “mother’s blessing” throughout the text. |

| 2 | See for discussion of these terms: (Grimes 2014, p. 211ff). |

| 3 | The photograph taken by famous photographer Annie Leibowitz has been chosen as one of the 100 most influential images of all times by Times magazine: http://100photos.time.com/photos/annie-leibovitz-demi-moore/. |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | Ritualization is what people do unconsciously and decorum is what they think one “ought to do” (Grimes 2010, p. 37). Decorum is face-to-face between two or a distinct number, and ceremony involves large-group interaction. |

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 | |

| 11 | |

| 12 | |

| 13 | |

| 14 | |

| 15 | |

| 16 | |

| 17 | |

| 18 | |

| 19 | Norwegian Humanist Association 2015, personal communication. |

| 20 | |

| 21 | |

| 22 | Ibid. |

| 23 | |

| 24 |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).