Abstract

Tangible, material objects sold in tourism contexts are often seen as problematic examples of commercialization, especially when they are marketed as examples of intangible Indigenous cultural heritages, representing Indigenous religion or spirituality. Taking the in situ presentations of examples of Sámi souvenirs connected to religious contexts in souvenir shops as a point of departure, this analysis investigates the complex relations these elements enter, with reference to religion, to the past, to the arts or crafts field, and to questions of ownership. The main theoretical focus is on how these souvenirs are adjusted to general, Western tourism imaginaries. One of the examples of such souvenirs are replicas in different sizes and qualities of the Sámi noaidi’s drum, while other examples discuss the use of the symbols on the drum applied to souvenir products, such as jewelry or other design products. Points of departure are the material souvenirs themselves, contextualized with in situ presentations in shops, on the net, and in social media, and linked to tourism imaginaries. The article tries to show how this in turn is related to still prevailing, general Western understandings of Indigenous Sámi religion and spiritualty.

1. Introduction

Visiting any significant tourist destination will convince the accidental visitor, as well as the experienced and dedicated tourist, that souvenirs remain an important part of the tourism industry. Souvenir shops are always at the center of the tourism businesses, or very strategically located at tourist sites, and it is obvious that they form an important part of the tourism economy. This impression was strengthened when I, in the late spring of 2019, together with tourism studies colleagues, travelled through the northernmost areas of Finland and Norway, with the intention to visit souvenir shops when their products offered for sale were at their most complete, just before the hectic summer tourism season started. The trip took us to some of the most popular tourist destinations in this greater transnational area also referred to as Sápmi, such as Roavvenjárga/Rovaniemi, Anár/Inari, and Ohcejohka/Utsjoki in Finnish Lapland, and Guovdageidnu/Kautokeino, Kárášjohka/Karasjok, and Deatnu/Tana1 in Norwegian Finnmark. Going by car, this of course also brought our group to many of the smaller (and certainly also bigger!) souvenir shops that suddenly would pop up along the road in these northern areas. Even if we travelled in remote areas, we were obviously on a beaten tourist track. Our primary aim was to study how ethnic and national minorities, and especially the Indigenous Sámi populations, were presented in the assortment and retail of souvenirs and handicraft in Sápmi.

The methodological approach of this paper is informed by cultural studies in anthropology, folklore, and tourism studies. The field method for documentation was at this first stage purely observational, looking at souvenir products with reference to Sámi culture in souvenir shops, and to some degree, this also involved a contextualization of the retail venues in relation to the larger attractions, businesses, theme parks, or museums that they were a part of. Documentation was also based on photography and film. In cases where photographing was explicitly forbidden, additional support for context was at a later stage found on companies’ and shops’ homepages on the net. An in situ understanding of what the tourist would encounter when they visited these shops was the initial and primary objective. In the analysis phase, however, further historical contextualization was needed and was sought in text and literature studies where relevant. The focus on tourism imaginaries demands knowledge of the history of Sámi religion, as well as knowledge of ethnic relations in the area. My present study focuses on the use of specific Sámi religious and spiritual symbols in these tourism souvenirs.

The selection of souvenirs in an area often primarily covers what is associated with the specific tourist destination in question and their main attraction(s), but often souvenirs also cover all kinds of elements connected to a broader geographical area, or any cultural elements connected to that context. For Sápmi, it is a given that the Indigenous Sámi culture is a main attraction in the area, and in that sense, it is also this culture that offers raw material for a very wide range of the souvenirs offered for sale, although the imagery of Sámi culture in tourism often is a very stereotypical version. Kjell Olsen has aptly called this version the “emblematic Sámi” (Olsen 2004). What is complicating the understanding here is, however, that souvenirs are not only mementos of tourists’ travels. Many of the souvenirs offered for sale create meaningful links to other phenomena, such as history, identity, and religion—and generally, these meaningful links are connected to the past (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1998; Graburn 1984). This means that the sale of souvenirs to tourists in different ways interferes with peoples’ cultures, heritages, and identities. Where Indigenous people are the producers of souvenirs, they are motivated by an urge to demonstrate their existence and uniqueness and resist oblivion (Graburn 1976, p. 26). Or, they are left with the options of “distinction” or “extinction” (Comaroff and Comaroff 2009, p. 10). For both producers and consumers, “heritage production” (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1998) and claims of “authenticity” (MacCannell 1976) become important standards. They are, however, easily transformed and transported by market interests, and many of the souvenirs are also produced outside the Indigenous communities.

While major touristic attractions in this area would typically cover nature and natural phenomena such as the Midnight Sun (in the light summer season) and the Northern Lights (in the dark winter season), other or additional attractions would be mythical beings supposed to inhabit the area (Santa Claus and his reindeer, in Santa Claus Theme Park in Roavvenjárga/Rovaniemi), and not least the Indigenous population, the Sámi (with their reindeer and their spiritual traditions, to be found everywhere in the area, but “condensed” in Sápmi Park, Kárášjohka/Karasjok). However, great local handicraft traditions related to Sámi heritage are also attractions (for example, Juhls’ Silversmith in Guovdageidnu/Kautokeino, and Tana Gull og Sølvsmie AS (n.d.) in Deatnu/Tana). Many of these businesses rely heavily on tourism in the area to survive, while some of the handicraft businesses also serve an important local market for jewelry meant for folk costumes.

However, the economic benefits of the trade in souvenirs are not the subject of the present discussion. Not because it is insignificant, but because the souvenir business raises other very interesting questions, related to their meaning-bearing capacities. Swanson and Timothy (2012) state that “…from a marketing perspective, it is important to commoditize the intangible meanings of souvenirs, and turn them into a tangible, consumable product for sale by destination merchants” (p. 493). It is therefore a central concern in this paper to have a closer look at souvenirs that have an explicit or more implicit linkage to Sámi Indigenous spirituality and religion.

Various discourses have lately emerged related to Sámi spirituality, Indigenous heritage, and ownership, and souvenirs and cultural appropriation. Just some of these questions are investigated here, but the cases show some of the complexities hidden in objects. The cases can tell us something about ethnic identifications, questions of ownership, and questions of how ethnic cultural elements should be represented, and by whom. The contexts where souvenirs are sold and bought might at first glance look very similar, stereotypical, and standardized, leaving an impression of homogeneity. A closer investigation of these contexts shows that this first impression might be superficial, and that production, exhibition strategies, and identity relations are much more complicated and heterogeneous. It is exactly in these kinds of commercialized touristic contexts where a heterogeneous group of tourists, representing diverse values, buy the souvenir products. They buy the things they find appealing, pretty, or exotic, irrespective of the producers’ intentions (that could also be multifaceted).

2. Souvenirs as Mementos of Imaginaries and Past Spiritualties

In his seminal and groundbreaking book on the tourist from 1976, Dean MacCannell in more than one sense set the stage for much of future tourism research in the social sciences and humanities. He set out to do an ethnography of the modern tourist, to “…try to understand the place of the tourist in the modern world…” (MacCannell 1976, p. 2). The way MacCannell saw this at the time of his investigation, the tourists were: “…sightseers, mainly middle-class, who are at this moment deployed throughout the entire world in search of experience.” (ibid., p. 1). One might add that these tourist were at that time most probably also Western middle-class persons (Graburn and Barthel-Bouchier 2001, p. 149). These tourists were, according to MacCannell, persons who felt their life in present-day, modern society was fragmented, divided, and alienated, lacking the alleged more holistic and genuine experiences of past and pre-modern societies. In short, tourists were on the search for this kind of more “authentic experiences” when they visited other countries and other cultures. As MacCannell pointed to, this search was most often doomed to be futile, because the visiting tourists together with the commercialization following the tourism encounter called for an arranged staging, in itself turning the performed version of the past into a kind of “staged authenticity” (MacCannell 1976, p. 91ff). Visits to souvenir shops can sometimes work against the feeling of authenticity, just because the commercial arragements are so blatant (see Figure 1), however, it is also possible to find elements that bring associations of a more exotic reality.

Figure 1.

‘Sámi magic drum’ with dolls in Sámi dresses, and other souvenir items in countryside souvenir shop in Alatalo, Finland, June 2019. Photo by the author.

Later tourism research has tried to understand this search for cultural authenticity in connection with the existence of widespread imaginaries, narratives, and fantasies about people and their cultures that eventually impels a constant search for meaningful experiences. Authors state that these “seductive images and discourses about peoples and places are so predominant that without them there probably would be little tourism, if any at all” (Salazar and Graburn 2014, p. 1), and tourism imaginaries and their promise to generate a large experience tourism industry have of course long been realized by marketing businesses. These imaginaries are, however, to be found nearly everywhere, in books, movies, media, and popular culture. However, they often end up in tourism marketing, demonstrating concrete examples of how dreams, fantasies, and imaginaries could be made real if you just order this trip or visit that place.

Another important element in these imaginaries is tied to cultures and traditions that are disappearing, from one point of view because they belong to the past, from another because they are threatened by external forces, which could be anything from colonialism to general modernizing processes, or even tourism itself, as MacCannell pointed out (MacCannell 1976, p. 91). This sort of nostalgia for the past creates spaces for heritage production in tourism (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1998, p. 153; Hafstein 2018, p. 85), or “staged authenticity” in MacCannell’s terms (ibid.). When this is linked with the brute influence from outside forces, with colonialism and imperialism (which is most often the case with Indigenous peoples and other ethnic minorities), Renato Rosaldo’s concept of “imperialist nostalgia” describes this process perfectly: “people mourn the passing of what they themselves have transformed” (Rosaldo 1989, p. 108).

Some such disappearing elements of culture are of course also religious and spiritual activities and beliefs. When modern tourism caught the interest of cultural research and anthropology, one very soon saw examples of trying to see tourism in relation to religious activities. One very obvious connection was to compare the old religious pilgrimages to modern tourism (Turner and Turner 1978); another analytical angel was to understand tourism in relation to ritual theory as presented by van Gennep ([1909] 1960), and later developed by Victor Turner (1969) and Edmund Leach (1976). This relation to modern tourism was most explicitly developed by Nelson Graburn when he in 1977 published his article, “Tourism: The Sacred Journey”. Here, he proposes to observe similarities between religious rituals, such as the rite de passage, and tourism. In passage rites, individuals move between profane and sacred stages. Graburn claims it has a heuristic function to understand the touristic journey as something that in a similar vein transports the tourist from the stage of work and everyday life, to a stage of holiday and leisure (and eventually back again). Being a tourist represents an extraordinary status, in contrast to ordinary life and work (Graburn 1977, p. 24ff). This perspective also explains tourism’s general interest in the exotic and in “the Other”, something to be found in what tourism companies in their promotional material would call “exotic cultures”.

In this context, Graburn considered the souvenir as the tangible evidence of this aspect of touristic experiences of having been at the outside of ordinary, everyday life. Talking about cultural tourists seeking experiences among ethnic groups, he writes: “The Ethnic tourist rarely has the opportunity to bring home the “whole Primitive” but is content with arts or crafts, particularly if they were made by the ethnic for his/her own (preferably sacred) use” (Graburn 1977, p. 33). Imaginaries connected to Indigenous peoples could of course represent a wide range of ideas and understandings, ranging from the most banal stereotypes to deep respect and knowledge of historical and cultural transformations that these peoples have experienced—and the same is true when it comes to souvenirs, covering the whole spectrum from genuine works of art by renowned Indigenous artists, to mass produced series of items with clichéd motives and references to a people and their culture (Graburn 1976, 1984). Usually, this also ranges from expensive to cheap products. The relationship between souvenirs and religion becomes even more complicated when religious symbols are associated with the inexpensive and serialized material versions of Indigenous spirituality.

Nonetheless, it is important to understand that there also are connections between the finer arts and the more commercial mass production for a souvenir market. Buying more expensive art and handicraft products brings with it a higher status for the consumer. These products are seen as more “authentic” than the cheaper ones. However, for tourists, one of the main issues with souvenirs might be that they bring proof of visiting societies, where a spirituality from the common human past is still “alive”. In the words of Beverly Gordon: “Handicraft products associated with people supposedly living in ‘another time’, also marks the traveler as someone who has really visited something out of the ordinary.” (Gordon 1986, p. 143). Therefore, it is important not only to focus on prices when looking at souvenirs, because other values are located in intangible imaginaries and in tangible souvenirs. Placing material objects such as relatively inexpensive tourist souvenirs at the center of analysis could also give a better understanding of the other values at play when Indigenous souvenirs are exchanging ownership in these tourism contexts.

3. Imaginaries of the Past: The Sámi Noaidi and His Govadas

Even in the oldest travelogues from travelers to the north of Europe, there are references to the magic activities of the peoples inhabiting this area (for an overview, see Moyne 1981). The Sámi Noaidi (a North Sámi word for a religious specialist) and his goavdiss (a North Sámi word for the drum this specialist used in his rituals) has been an important part of this imaginary for centuries, and the drum has a central place on many frontispieces on travelogues from the North. The production of this vital magic instrument travelled a long and complicated road from magic experts, to museums and collectors, to artful copies for exhibitions and art galleries, and then to mass-produced drums in various sizes for the tourism market today (Mathisen 2015; Joy 2018). In the same way, the users of the drums transformed from old descriptions of weird and heathen “sorcerers” to contemporary New Age shamans, and performers in the tourism business (Fonneland 2012). They have moved from an outlawed instrument for “heathen” doings to an interesting and respectful crafts product in souvenir shops. However, the development from a dangerous Noaidi’s instrument of evil (in the eyes of colonizers and Christian missionaries) to a legitimate object in the souvenir shops has taken place only during the last 20 years or so.

I remember some 30 years ago making a phone call to one of the larger crafts and souvenir shops in Sápmi, asking if they had any “Sámi shaman drums” for sale. The owner denied this, but also sounded very skeptical, asked what my purpose with this drum would be, and what I wanted to use it for. I most probably referred to my interest in the object as a folklorist, or I might have said that I wanted to use it as a gift. I cannot remember the details anymore, but the main thing I experienced from this conversation was that there was no possibility for buying such an item in their shop, and that even asking for a possible purchase was a bit suspicious.

When the tourist theme park Sápmi Park opened in the village of Kárášjohka/Karasjok in the year of 2000, with its “Sápmi Magical Theatre” (named “Stálubákti” in North Sámi), this was the first ever effort in Norway to put to stage and performance parts of the Sámi spiritual world view (for a more detailed description and discussion of this performance, see Mathisen (2010, p. 62ff) and Mathisen (2015, p. 205f)). The effort seemed innovative and daring at the same time. Putting intangible heritage, such as world views, religious understandings, and Indigenous spirituality, up for display or performance is not always easy, especially in a commodified setting like a touristic theme park. However, when the Sápmi Theme Park decided to establish this, they contacted a well-established international company, BRC (n.d.) Imagination Arts2, specializing in experience design and production. For support, some of the most prominent Sámi artists, authors, and filmmakers were contacted for cooperation (overview in the lobby of Sápmi Magic Theatre). The result was a multimedia production with technical solutions that, at least at the time, pushed boundaries and represented something new and never previously experienced in Sápmi. However, if the technology was brand new, the content was both old and well known. The old imaginaries of the Sámi as mythologized guardians of an ancient spirituality, in close contact with nature, which also made them potential ecological guardians for a future where humankind could still live in harmony with nature. What was related in this creative combination of old mythologies and modern ideas of environmentalism with the help of modern visual and media technologies was therefore simultaneously an old and a new narrative. The old narrative of a “noble savage” had been turned into a contemporary narrative of the “ecological Indigenous Sámi”. The new narrative, however, was caught in the same colonializing constructions from where it had originated. Even if it in many ways was a positive image of Indigenous thinking and spirituality, it still placed “the Other” in a static and immobile position, where all development and transformation would be negative (Mathisen 2004). Additionally, in this case, the similarities between different depictions of other Indigenous populations all over the world are striking. In many ways, Indigenous religions and spirituality have become parts of a global narrative and imaginary.

When I was a visiting professor in 2015–2016 at the Anthropology department at the University of California, Berkeley, I gave a lecture in The Forms of Folklore class, where I, among other subjects, also talked about this Sápmi Magic Theater performance at Sápmi Park. After the lecture, one of the GSIs (Teacher Assistants) approached me and said that what I had just told (and showed pictures from) reminded him very much of something he had witnessed close to his home in Los Angeles, California. At Knott’s Berry Farm in Buena Park, there was a show called Mystery Lodge. The staging and the design was very similar to what I had presented, only the peoples portrayed there were Native Americans, not Sámi. I asked him if he could find the name of the company which made that show. It turned out that the same company was behind the show in Kárášjohka/Karasjok and the one in Knott’s Berry Farm. This partly explains the similarities in the two presentations; however, this also shows that some of the myths told about the spirituality of Indigenous peoples are very similar, and that they might easily be interchanged, and hence immediately appreciated and understood by a global as well as a local audience.

Some of the same observations can be seen in relation to souvenir sales. In many of the souvenir shops we visited, cultural items associated with different Indigenous peoples could be found side by side on display. Sámi Noaidi’s drums were, for example, exhibited together with Native American dreamcatchers in a souvenir shop in Roavvenjárga/Rovaniemi. They fit into and belonged to the same narrative on the spiritualties of Indigenous peoples. This is also partly a tendency where companies offering Sámi experiences for tourists are anxious to include aspects of Indigenous spiritual, most often pre-Christian, elements and symbols (Fonneland 2013), and the Noaidi’s drum has a prominent place in the visualizing process.

The Sámi Noaidi’s drum has in recent years made its entry in quite many museums in the Sápmi area, both as original drums because of repatriation processes, and as artful copies made by talented Sámi craftspeople (Äikäs 2019). In that capacity, many drums have entered art galleries and art collections, now understood as original artworks. The drums have become elements in the imagery of theme parks, and they have eventually entered the shelves of both museum shops and souvenir shops. One very popular and recurrent product comes from the company Lappituote (n.d.) Oy in Kemi, Finland, which offers “shaman’s drums” (in Finnish: noitarummut) in various sizes, ranging from small ones, to one near “full size”3. These can be found both in souvenir shops and in museum shops all over the Sápmi area.

When our group in 2019 made a stop in Anár/Inari, we spent the night at the Hotel Inari, and I was anxious to see if the picture I had seen in an earlier visit to the hotel, in 2013, was still there (see Mathisen 2015, p. 192). The reproduced picture of a painting from 2006 made by the Sámi artist Merja Aletta Rauttila from the nearby town of Gáregasnjárga/Kargasniemi showed a little Sámi boy, a child Noaidi, leaning over his goavddis, more than half his own size, and with the drum hammer in his hand. It turned out that this picture decorated nearly every room occupied by us in the hotel, and the motive was also available as a postcard. What caught my attention now was that the figures painted on the drum skin had started to move out of the drum, as if they were set out to act, or going on a travel.

This made me think of something I had just observed the day before, when we were visiting souvenir shops in Santa Claus Theme Park in Roavvenjárga/Rovaniemi. The images that could be found on the old Noaidi’s drums still to be found in museums were now available as decorations on nearly every souvenir product you could think of. They were very visible in enlarged versions printed on from every kind of home decoration, pillow, bedding, rug, and curtain to every kind of kitchen utensil, cup, napkin, and tablecloth—not to mention different clothing products, especially t-shirts with printed images of the Noaidi’s drum, of course. What is striking here, as with the souvenir Noaidi’s drums themselves, is that they are exhibited in the shop as serialities, and not as unique items. The supply of items seems endless, and there seem to be no limits to the use of the figures associated with the Noaidi’s drum (see Figure 2 for some examples of this). Still, it is the association with Indigenous spirituality that is the selling point, and they are now attached to products that anyone might find useful in one way or another. In the souvenir industry, this would not necessarily be the case for the Noaidi’s drum itself, which would only serve its purpose as decoration, or for some kind of exhibition.

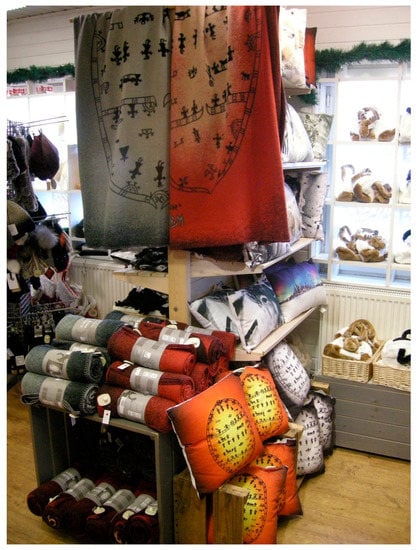

Figure 2.

‘Rugs and pillows with motifs from Sámi Noaidis divination drums in a souvenir shop in Roavvenárga/Rovaniemi, Finland June 2019. Photo by the author.

The fact that the symbols from the drums are the most important elements for this trade is visible because once they have been established as popular touristic icons, it is a tendency that they start appearing on nearly everything else that could possibly be bought as a souvenir, ranging from key holders and cups to pillows and towels. A symbol from the rune drum is printed on various objects, and they are transformed into materialized memories of a travel to a magic north, and experiences of enchanted landscapes and peoples.

4. Silver, Spirituality, and Ownership: Who Owns Beaivi (the Sun)?

Professor Yngvar Nielsen was the head of the Ethnographic Museum in Kristiania in 1877–1916. He was also chairman of Den Norske Turistforening (The Norwegian Trekking Association) in 1890–1908 and published a travel manual for tourists in Norway, popularly called “Yngvar”. On one of his travels, he visited a Sámi camp in Troms County with the intention of buying utensils carved from reindeer antlers for the museum. He wrote in a popularized article in the German journal Globus, in which he claimed that this trade would be very easy for visiting travelers, because “the lust for silver” was very great among this group of people (Nielsen 1892, p. 66). He could proudly obtain these items for small silver coins. The Sámi would then send silver to silversmiths further south in Norway, who would make silver jewelry the way Sámi people wanted them. For nomadic people like the reindeer-herding Sámi, this was the most convenient way of keeping valuables. Moreover, the silver objects were valuable in another, more religious and spiritual sense. Silver would protect the carrier from evil forces. It was common to leave a silver spoon or a silver amulet in the child’s giehkta (Sámi carrying cradle), so the children are not abducted by the gufihtarat (invisible underground people).

Later, some silversmiths established themselves permanently in Sápmi, relying on a steady market for silver products among the Sámi for their traditional Indigenous costumes, but also for a growing tourism market. Already from the outset, there was some concern over the ownership to some of the designs that had been popular among the Sámi for hundreds of years. Many of the silversmiths have solved this possible controversy by maintaining that they are doing their work “in the service of the Sámi”, and that they are copying the old Sámi designs because this is the way the Sámi want them, and therefore, they have to be faithful to the original designs. If something should be changed, then that should only happen in close cooperation with the Sámi customers.

Juhls’ (n.d.) Silver Gallery started their silver smithy in Goudageidnu/Kautokeino in 1959 and adhered to a philosophy of serving the Sámi people by supplying traditional designs. Alongside this production, they developed their own unique designs inspired by the surrounding Arctic nature and landscape. The business of course also relies on tourism; however, you would not find the typical souvenir products in their shop. When asked by our group during the visiting roundtrip in 2019, they maintained that they would not use the designs from the Sámi Noaidi’s drum on their designs. They have, however, used some design patterns inspired by ancient petroglyphs in the northern area, as well as old designs associated with other northern Indigenous populations. It seemed that one important criterion was that these designs should be very old, and not possible to connect with the post-colonializing era. This is what Juhls’ (n.d.) Silver Gallery in Gouvdageidnu/Kautokeino wrote on their webpage about one of these symbols:

“The ‘Sun cross’. This symbol comes in many different variants and are some of the oldest historical symbols—originally used by Finnish-Ugrian peoples in northern Russia. These embellished the belt but had a practical feature as well as an attachment for knifes, scissors, keys etc., as well as a “needle tent/nállugoahti” which is a container for sewing needles.”4

They have also continued to produce some of the older Catholic jewelry that used to be popular among the Sámi and describe it in this way:

“Originally an M for Virgin Mary from Catholic times in southern Scandinavia. After the reformation, this became a common merchandise further north where the Sami people were not yet Christian.”5

Juhls’ (n.d.) Silver Gallery then has in this way chosen to follow some very clear strategies to avoid conflicts with the Sámi Indigenous society. One strategy is that they promote themselves as servants to the Sámi, just reproducing their traditional designs, following the norms and demands from the Sámi people in how the design of the silver for their Indigenous costumes should be. Another strategy is to locate their inspirations for designs with spiritual connotations in a more distant past where contemporary ethnic categories are less obvious, and claims of cultural appropriation would not be voiced.

As mentioned above, inside the Santa Claus Village in Roavvenjárga/Rovaniemi, there is a sort of supermarket of souvenir shops. One of these shops belongs to the firm Taigakoru (n.d.), which specializes in silver jewelry, and many of its products are inspired by spiritual imagery. To underline this, a central part of their exhibition is a “shaman’s drum”, where the silver jewelry figures offered for sale in what is called the “shaman drum collection” are organized on the drum skin, to better demonstrate the very close connection between the jewelry and spirituality (see Figure 3). This is the way it is presented on their internet homepage:

“SHAMAN DRUM was used by the shamans of the Northern peoples in their ceremonies. Shamans were healers and predicted the future. They called on the spirits for assistance by beating a drum with a drumstick made from reindeer bone until they fell into a trance. The upper part of the drum skin represented the heavens, the middle part earth and earthly life and the lower part Tuonela, the underworld.6

Figure 3.

Silver figures, freely based on what allegedly are motifs from Sámi Noaidis’ divination drums. From Taigakoru’s souvenir shop in Santa Claus Theme Park in Roavvenárga/Rovaniemi, Finland June 2019. Photo by the author.

The silver patterns associated with the signs on the Noaidi’s drum and represented in this collection are the sun, the bear, the black-throated loon, the crane, the moon, the salmon, the beaver, the god of hunting, the lights of the north, the reindeer, the rota7, the goddess of fertility Akka, the shaman, the wolf, the god of thunder, and the boat (ibid.; see also on the Taigakoru (n.d.) jewelry, with image, in Ridanpää (2019, p. 130f)). Notable here is that the symbols from the drum skin are explicitly associated with a more general reference to a sub-Arctic, Fenno-Ugric cultural environment, possibly to avoid questions of cultural ownership.

However, there certainly are examples of controversies over inappropriate use of Sámi spiritual and religious symbols and over the ownership to such symbols. The most recurrent and central sign on the Sámi Noaidi’s goavddis is a representation of the sun, either in a very stylized form, or pictured in a more naturalized shape, which anyone might recognize as the sun. Most early and later research into Sámi religion points to the sun as one of the highest divinities for the Sámi (for an overview, see Lundmark (1982, p. 13ff); Joy (2020b)). Just as our research group was making the trip investigating the offers of souvenirs in parts of Sápmi in the early summer of 2019, there was a substantial controversy in the area connected to one silversmith’s use of the sun symbol. The reason was that Tana Gull og Sølvsmie AS (n.d.) in 2013 had applied for a design patent and trademark for their version of the sun symbol to Patentstyret (Norwegian Industrial Property Office), a governmental office that registers trademarks, designs, and patents in Norway. The design was then registered and announced in early 2014. By this time, the product had already been for sale in different variants as a silver jewelry for some years, and this is the way it is presented at Tana Gull og Sølvsmie AS’s homepage:

“The midnightsun is an important natural phenomenon for the sami people. The sun is painted on almost every preserved sjaman drum. The sun is often stylized beyond recognition but our sun is inspired by a drawing of a drum from Aasele Lappmark/Sveden. This drum has been known since 1693 but may be much older than this.”8

The business places the sun symbol very explicitly as an important part of Sámi heritage, and this soon became a part of the controversy. Another reason was that the owners of the firm had started sending out letters of warning to other handicraft producers, claiming that they would run the risk of being accused of plagiarism if they used a similar sun symbol on their designs. This was then reported in NRK Sápmi, the Norwegian radio broadcaster (the program was later retracted, because it contained factual errors). When the owners of Tana Gull og Sølvsmie AS (n.d.) further announced their design property claims on their Facebook page9, a storm of protests broke loose. A lot of craftspeople and others engaged in Sámi design protested, and people started to put their versions of the Sámi sun on their Facebook accounts. One handicraft producer took legal action and filed a claim to Patentstyret, appealing their decision on design property and demanded it changed, as this version of the sun was a common Sámi heritage, that no single person or company could claim ownership to. Many comments also referred to the late Sámi multiartist (music, visual art, and poetry) Nils-Aslak Valkeapää, who had used an almost identical design of the sun on the cover of his famous book “The Sun, My Father” (Valkeapää 1991). Patentstyret made a new decision in late November 2019 that the design was an old Sámi sun symbol, and not a new design, and hence should be understood as a copy, not filling the demands for genuine design. It is, however, still registered as a trademark for the Tana business.

This means that questions over Indigenous design now had entered what the anthropologists John and Jean Comaroff in their book on the commodification of ethnic cultures have called a stadium of “lawfare” (Comaroff and Comaroff 2009, p. 53ff). This is according to the authors a significant change in identity politics and the fight for the cultural rights of Indigenous peoples. The struggle for general human rights for these groups has now, in a time of neoliberal market economy, also come to include the ownership of cultural and spiritual knowledge (ibid., p. 56). It has become a question of matters that can be decided not only by political means, but also by legal instruments. This development would, eventually, have both positive and negative consequences, particularly because any use of the legal system also will have to involve economic resources. Lack of resources would effectively silence those producers with little access to monetary means.

5. Tourist Souvenirs and Imaginaries

Sámi culture and religion have been at the center of attention among travelers to the Arctic North of Scandinavia ever since the first attempts to enter this area, and this takes up an important space in their writings. Olof Rudbeck the younger (1660–1740) traveled to Lapland in 1695 (Rudbeck [1695] 1987). His experiences from that travel as they appear in his journal are summed up by Koerner in her book on Linneaus: that the Sámi were already acting as tourist guides of the destruction of their own religious culture when they were showing the visiting travelers their former cult places (Koerner 1999, p. 58f). In a handwritten note, Rudbeck the younger, however, warned the visiting scientist and traveler Pierre Louis Maupertius (1698–1759) and his company when they visited Lapland in 1736 that these Sámi did not like it when the visitors laughed when they showed them the old offering places, the sieidis (Koerner 1999, pp. 59, 226; von Sydow [1695] 1987, p. 27).

This sense of paying due respect to past Sámi spiritual traditions still seems also to be at the core of much of contemporary attitudes, positive or negative, when it comes to relations between past Sámi spiritual imagery and tourist souvenirs. Sámi spirituality and religion should be presented in a respectful way. The Sámi Parliament in Finland (so far as the only national Sámi Parliament) has issued their “Responsible and Ethical Principles for Sustainable Sámi Tourism” (Sámediggi 2018), a small booklet where they outline guidelines for how Sámi culture should be presented for tourists. These guidelines are as yet only available in the Finnish and Sámi languages, setting up the main principles for tourism in Sápmi, and the “dos” and “don’ts” have been illustrated using easily accessible cartoons, made by the Sámi artist Sunna Kitti (Quinn 2020). However, guidelines have not been followed by legal measures. Souvenir production based on Sámi cultural heritage is often industrial in scale and more based on economic profit than moral judgement and cultural sensitivity (Joy 2020a). Even if souvenirs might at first glance seem to be very simple and sometimes even banal objects, attempts at contextualization show both complicated historical connections, as well as intriguing implications when it comes to using these objects as the basis for a contemporary presentation of a unique Sámi cultural heritage.

The starting point for the investigation, therefore, is not only the souvenir objects in themselves, but also the tourism imaginaries they are already connected to. This makes the field of research when it comes to tourism souvenirs associated with Indigenous religion and spirituality complicated. The souvenirs serve purposes in relation to larger narratives. The tourism imaginaries of contemporary visitors to the Sápmi area have had their respectful as well as their stereotypical ideas about the area and its people formed by previous narratives and imagery. The orientation toward the past creates stereotypical imaginaries about a reindeer people living in a perfect harmony with the surrounding nature. This and similar kinds of imagery create problematic positions for Indigenous peoples throughout the world who want to make their voices heard in contemporary struggles for natural resources and rights, even when they are living as modern contemporary citizens in a developed world. Imaginaries of the past hold a value for the visiting tourists who want to visit something exotic and out of the ordinary. The souvenirs, and especially those with Indigenous spiritual connotations, serve as documentation of such visits for visiting travelers. For the Indigenous Sámi population, the souvenirs carry mixed and ambivalent messages that they will have to relate to as contemporary citizens. The tourism imaginaries’ orientation toward a mythic past tends to place Indigenous people in an ambivalent position, on one hand, as proud representatives of genuine spiritual traditions, and on the other, as exotic representatives of a past with no place in modern society (Mathisen 2004).

Questions of ownership to spiritual traditions raise similar problematic positions. Craftspeople would like to protect their products, while increased tourism and commercialization open up a path for seriality, mass production, and copying. The present situation on the tourist market will affect the communication of Indigenous identity values. Mass tourism and large theme parks seem to have an effect on the souvenir market, favoring serialized objects and mass production. This is apparent in the manner in which the symbolic figures on the Sámi Noaidi’s drum have left the drum skin and started appearing on nearly all kinds of other souvenir products. These kinds of innovations are also making the possibilities for contextualizing previous meanings of these symbols difficult. There are, however, always innovative and transformational resources in the Indigenous art and crafts field, inventing new and interesting products that hopefully will invigorate souvenir production and still communicate important Indigenous values.

Funding

The field trip was supported by a small grant from the Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education at UiT The Arctic University of Norway. The publication charges for this article have been funded by a grant from the publication fund of UiT The Arctic University of Norway.

Acknowledgments

Co-travellers on the souvenir investigation trip were Trine Kvidal-Røvik, Kjell O. K. Olsen and Gyrid Øyen, all from the Department of Tourism and Northern Studies at UiT the Arctic University of Norway, and filmmaker Kristin Nicolaysen from Nicolaysen Film. I want to thank them all for their inspirational observations and fruitful discussions on the road.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Äikäs, Tiina. 2019. Religion of the past or living heritage? Dissemination of knowledge on Sámi religion in museums in Northern Finland. Nordic Museology 3: 152–68. [Google Scholar]

- BRC. n.d. BRC Imagination Arts. Available online: https://www.brcweb.com/ (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- Comaroff, John L., and Jean Comaroff. 2009. Ethnicity, Inc. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fonneland, Trude. 2012. Spiritual Entrepreneurship in a Northern Landscape: Spirituality, tourism and Politics. Temenos 48: 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonneland, Trude A. 2013. Sami Tourism and the Signposting of Spirituality. The Case of Sami Tour: A Spiritual Entrepreneur in the Contemporary Experience Economy. Acta Borealia: A Nordic Journal of Circumpolar Societies 30: 190–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, Beverly. 1986. The Souvenir: Messenger of the Extraordinary. Journal of Popular Culture 20: 135–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graburn, Nelson H. H., ed. 1976. Ethnic and Tourist Arts. Cultural Expressions from the Forth World. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Graburn, Nelson H. H. 1977. Tourism: The Sacred Journey. In Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism. Edited by Valene Smith. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Graburn, Nelson H. H. 1984. The Evolution of Tourist Arts. Annals of Tourism Research 11: 393–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graburn, Nelson H. H., and Diane Barthel-Bouchier. 2001. Relocating the Tourist. International Sociology 16: 147–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafstein, Valdimar Tr. 2018. Making Intangible Heritage. El Condor Pasa and Other Stories from UNESCO. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Joy, Francis. 2018. Sámi Shamanism, Cosmology and Art as Systems of Embedded Knowledge. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Lapland, Rovaniemi, Finland. [Google Scholar]

- Joy, Francis. 2020a. Sámi Cultural Heritage and Tourism in Finland. In Resources, Social and Cultural Sustainabilities in the Arctic. Edited by Monica Tennberg, Hanna Lempinen and Susanna Pirnes. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Joy, Francis. 2020b. The Importance of the Sun Symbol in the Restoration of Sámi Spiritual Traditions and Healing Practice. Religions 11: 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhls. n.d. Juhls’ Silver Gallery. Available online: https://www.juhls.no/en/ (accessed on 6 February 2020).

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara. 1998. Destination Culture. Tourism, Museums, and Heritage. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koerner, Lisbet. 1999. Linnaeus: Nature and Nation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lappituote. n.d. Lappituote Oy. Available online: https://www.lappituote.fi (accessed on 6 February 2020).

- Leach, Edmund. 1976. Culture and Communication. The Logic by Which Symbols Are Connected. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lundmark, Bo. 1982. Bæi’vi Mánno Nástit. Sol- och månkult samt astrala och celesta föreställningar bland samerna. [Sun Moon Stars. Sun and Moon Cult, including Astral and Celeste Perceptions among the Sámi]. In Acta Bothniensia Occidentalis Skrifter i västerbottnisk kulturhistoria 5. Umeå: UTAB. [Google Scholar]

- MacCannell, Dean. 1976. The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class. New York: Schocken Books. [Google Scholar]

- Mathisen, Stein R. 2004. Hegemonic Representations of Sámi Culture. From Narratives of Noble Savages to Discourses on Ecological Sámi. In Creating Diversities. Folklore, Religion and the Politics of Heritage. Edited by Anna-Leena Siikala, Barbro Klein and Stein R. Mathisen. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Mathisen, Stein R. 2010. Indigenous Spirituality in the Touristic Borderzone: Virtual Performances of Sámi Shamanism in Sápmi Park. Temenos. Nordic Journal of Comparative Religion 46: 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathisen, Stein R. 2015. Contextualizing Exhibited Versions of Sámi Noaidevuotha. In Nordic Neoshamanisms. Edited by Siv Ellen Kraft, Trude Fonneland and James R. Lewis. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 191–213. [Google Scholar]

- Moyne, Ernest J. 1981. Raising the Wind. The Legend of Lapland and Finland Wizards in Literature. Newark: University of Delaware Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, Yngvar. 1892. Die Lappen im Amte Tromsö. Globus. Illustrierte Zeitschrift für Länder- und Völkerkunde 61: 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, Kjell. 2004. The Touristic Construction of the “Emblematic” Sámi. In Creating Diversities. Folklore, Religion and the Politics of Heritage. Edited by Anna-Leena Siikala, Barbro Klein and Stein R. Mathisen. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, pp. 292–305. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, Eilís. 2020. How Not to Promote Arctic Tourism. Why Finland’s Indigenous Sami Say Marketing Their Region Needs to Change. Eye on the Arctic Special Reports. Available online: https://www.rcinet.ca/eye-on-the-arctic-special-reports/how-not-to-promote-arctic-tourism-why-finlands-indigenous-sami-say-marketing-their-region-needs-to-change/ (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Ridanpää, Juha. 2019. Postcolonial Critique and the North in Geographical Imaginations. In North as a Meaning in Design and Art. Edited by Mäkikalli Maija, Holt Ysanne and Hautala-Hirvioja Tuija. Rovaniemi: Lapland University Press, pp. 123–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rosaldo, Renato. 1989. Imperialist Nostalgia. Representations 26: 107–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudbeck, Olof den yngre (the younger). 1987. Iter Lapponicum I-II. Skissbok Från Resan till Lappland 1695. Stockholm: René Coeckelberghs Bokförlag AB. First published 1695. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, Noel B., and Nelson H. H. Graburn. 2014. Tourism Imaginaries. Anthropological Approaches. New York: Berghahn. [Google Scholar]

- Sámediggi. 2018. Vastuullisen ja Eettisesti Kestävän Saamelaismatkailun Toimintaperiaatteet [Responsible and Ethical Principles for Sustainable Sámi Tourism]. Anar and Inari: The Sámi Parliament of Finland. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, Kirsten K., and Dallen J. Timothy. 2012. Souvenirs: Icons of meaning, commercialization and commoditization. Tourism Management 33: 489–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taigakoru. n.d. Available online: https://www.taigakoru.eu/ (accessed on 6 February 2020).

- Tana Gull og Sølvsmie AS. n.d. Available online: https://www.tanagullogsolv.com/en/ (accessed on 8 February 2020).

- Turner, Victor W. 1969. The Ritual Process. Chicago: Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Victor, and Edith Turner. 1978. Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture: Anthropological Perspectives. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Valkeapää, Nils-Aslak. 1991. Beaivi, Áhčážan. Guovdageaidnu and Kautokeino: DAT. [Google Scholar]

- van Gennep, Arnold. 1960. The Rites of Passage [Les rites de passage]. London: Routledge. First published 1909. [Google Scholar]

- von Sydow, Carl-Otto. 1987. Introduction till dagboken. In Iter Lapponicum II. Skissbok från Resan till Lappland 1695. Edited by Olof den yngre Rudbeck (the younger). Kommentardel and Stockholm: René Coeckelberghs Bokförlag AB, pp. 22–27. First published 1695. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Place names are written in North Sámi/Finnish or Norwegian. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | Sámi god of the underworld and death. |

| 8 | |

| 9 |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).