Abstract

Shui Wei Sheng Niang (水尾圣娘) Temple is located within a united temple at 109a, Hougang Avenue 5, Singapore. Shui Wei Sheng Niang is a Hainanese goddess, the worship of whom is widespread in Hainanese communities in South East Asia. This paper examines a specific Hainanese temple and how its rituals reflect the history of Hainanese immigration to Singapore. The birthday rites of the goddess (Lantern Festival Celebration) are held on the 4th and 14th of the first lunar month. This paper also introduces the life history and ritual practices of a Hainanese Daoist master and a Hainanese theater actress.

1. Introduction

Although the original Hainan village of Hougang no longer exists in Singapore due to the urbanization and renovation of Singapore, people of that Hainanese community still gather together to celebrate the Lantern Festival and worship the goddess Shui Wei Sheng Niang (水尾圣娘), who originated from Hainan Island. This shows how Hainanese descendants still have the autonomy to maintain their cultural, religious, and dialect-based identity. The traditional Keepers of the Incense Burners and Village Heads of Ritual are still selected each New Year before celebrations begin. This indicates that the customary institutions of decision-making within the Hainanese community are still alive. As Kenneth Dean proposed in his article Parallel Universes (Dean 2015), increasing control over society by colonial and post-colonial secular governments has not completely eliminated dialect-based cultural identity, and rituals remain a key element in how people exercise their local autonomy.

Hainan Island has China’s third-largest emigrant community living in Southeast Asia. Seven million people live on the whole island, and three million Hainanese live overseas (Zhao 1998). According to The History of Hainanese Coming to the South to Earn Their Livings (琼州人南来沧桑史) by S. Han (1996), emigration from Hainan Island occurred in four phases. The first peak was during the Opium Wars (1839–1842, 1856–1858), after the Qing Empire abolished its bans on overseas trade. In 1854, the Hainan Mazu Temple (琼州天后宫), together with the Hainan Guild Hall (海南会馆), was established in Singapore. By 1881, 8300 Hainanese people lived in Singapore. The second peak occurred in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when Hainanese flocked to the old colonial empire to work in the Dutch rubber industry and the tin mining industry in Southeast Asia. The third peak was in the 1920s and 1930s. The fourth peak was after the Japanese army invaded and occupied Hainan Island in 1939. Nowadays, up to 250,000 Hainanese people dwell in Singapore, and about 300,000 Hainanese migrants and their descendants reside in Malaysia.

Hainanese people form the fifth-largest dialect group in the Singapore and Malaysia area, following the Cantonese, Hokkien, Hakka, and Teochew groups. Relatively speaking, as they are the smallest dialect group in Singapore, academic research on the Hainanese is not as abundant as it is on other dialect groups. The excellent and systematic master’s thesis written by M. G. Han (2012) stands out.1 However, the status of communal religions (Dean 2003) of the Hainanese dialect groups is not highlighted. This article strives to provide a detailed case study of one of the Hainanese temples in Singapore, aiming to discuss the following issues: What is the history of Hainanese communal temples? How do the Hainanese communal temples survive, and how are they managed? What kind of ritual practices are performed in these temples, and what are the life stories of the ritual agents? Furthermore, in the future, the article hopes to further the study of Hainanese immigrations in South East Asia.

Shui Wei Sheng Niang Temple in Hougang is one temple unit within a shared “united temple” in Singapore. United temples are large structures that can contain over a dozen temple units, often reduced to a single altar-table set against a wall with the statues of the deities of the original temple at one end (Hue 2013). The Shui Wei Sheng Niang Temple is currently located at 109a, Hougang Avenue 5. Before moving to Hougang, the temple was in the Hougang Hainanese village for over 80 years. The legends of Shui Wei Sheng Niang and temples are widespread among Hainanese communities in South East Asia. This study is one case to show the autonomy of the community.

2. Versions of Legends of Shui Wei Sheng Niang

Shui Wei Sheng Niang is a marine goddess brought by the Hainanese immigrants when they first moved to South East Asia and it has been passed down to present day. She is worshiped for her legends and her efficacy. In addition, multiple versions of her legends show the different understandings of the goddess within the community that make the goddess integrated as one image. Such autonomous belief makes the legends both diverse and unified.

There are various versions of the legend of Shui Wei Sheng Niang, the Saintly Lady at the Tail of the Sea. One of the versions, told to the author by a Daoist master, Wang Xiaoxiang, is that the Secondary Madam of Shui Wei Sheng Niang (水尾圣娘二婆) reveals herself to help fisherman find their fish. One story about the fisherman says they caught an uncarved wooden block and worshiped the block as the goddess. In a student group report from the National University of Singapore for the Singapore Historical GIS project (see Yan et al. 2020), it is also recorded that Shui Wei Sheng Niang was a wooden block before becoming a goddess.

Yan Kit Village Chinese Temple (寅吉村华人庙) is the first Shuiwei Sheng Niang Temple built in Singapore:

However, this version of the story is not the same as the one transmitted in Hainan Island. According to local gazetteers, the Shuiwei Temple is dedicated to the worship of Madam Nantian (南天夫人, Lady of the Southern Heavens), who is the goddess of thunder. The temple in Qianglan, Wenchang, was built between the years 1506 and 1521, in the middle of the Ming Dynasty. During the Jiaqing period (1796–1820) of the Qing Dynasty, the temple was officially listed in the Record of Sacrifices, and the goddess was promoted and enfeoffed as the Saintly Lady at the Tail of the Ocean Who Responds with Fire and Thunder and Shoots Lightning Out of the Southern Heavens (Nantian Shui Wei Sheng Niang, 南天闪电感应火雷水尾圣娘)There has been a saying by the Hainanese that the founding of the temple and its goddess was a result of a supernatural experience. In the past, there was a fisherman named Pan Jian, who lived in Wenchang County of Hainan Island. On one fishing encounter, a wooden block landed in his fishing net multiple time consecutively. Suspecting that the wooden block might have supernatural powers, he promised to carve the wood into a statue and build a temple to worship it if his wish for a good catch [were] fulfilled. Pan did gain a good catch afterward; however, he left the wooden block aside. Subsequently, his crops started failing and dying. The villagers suspected that the strange phenomenon was a result of his [having reneged on his vows]. Hence, they raised funds and built a temple. This temple was the origin of this one, the first temple built for the [goddess] in the Hainan Island.(Leong et al. 2017, p. 1)

In another legend, Shui Wei Sheng Niang is a missing female ancestor who is said to have been chosen by the Jade Emperor and thereupon became a saint. Moreover, her story changes as it takes place not in a seaside village but in an inland village in Dingan County. Shui Wei Sheng Niang, also known as Madam Nantian (Lady of the Southern Heavens), or as Madam Mo (Lady of the Sacred Edicts Who Responds Within the Clouds at the Tail of the Waters, 水尾云感圣旨莫氏夫人), is the sister of the Mohu (莫瑚), the first-generation ancestor of the Mo clan of Shuiwei Village in Ding’an County, Hainan Island. Their decedents respected her as the Goddess of the Sacred Edict (圣旨婆祖) and built temples to worship her. The Mo clan believes that the name of the Goddess of the Sacred Edict is Liniang, and her surname is Mo. She was born in the early Ming Dynasty in the village of Meilong, Malong Village, Ding’an County (now Shuiweitian Village, Lingkou Town, Ding’an County, Hainan Province). Her father, Mo Su (莫素), was a 14th generation descendant of the Mo lineage, and her mother was named Liu Mei. At the age of 16, Mo Liniang went to work on a particular day and never returned. It is said that the Jade Emperor chose her, and her flesh returned to heaven and she became a saint with divine power. Thus, she was publicly worshiped during the Jiaqing period (1796–1820) of the Qing Dynasty (Mo 2004).

There is considerable controversy as to whether Madam Mo is identical to Shui Wei Sheng Niang. However, it is evident that the Hainanese in Singapore did not accept this version of the goddess’ origins. One of the reasons for this may be that most of the Singaporean Hainanese originated from Wenchang; very few are from the inland villages like Ding’an County.

The versions of legends are quite different, which indicates that the immigrants of Hainanese Singaporean have another collective memory of the goddess. After 80 years, they still keep the legends, which shows their autonomy is still visible.

3. History, Space, Rituals, and Networks

The Hainanese local autonomy is based on history, space, ritual, and temple networks. All these sections are run by the grassroots which consist of local people. They form a committee to phrase their history, create their space, organize and perform the rituals, and have a temple network.

3.1. History

The Hougang Shuiwei Sheng Niang Temple was originally located on Lorong Ah Soo (罗弄亚苏) Road. The original site of the temple became an elementary school in 1949. In 1981, the temple was moved under the instruction of the Singapore government to its current address in Hougang, Sengkang. At that time, the temple committee and membership raised millions of Singapore dollars to rebuild the temple.

3.2. Space

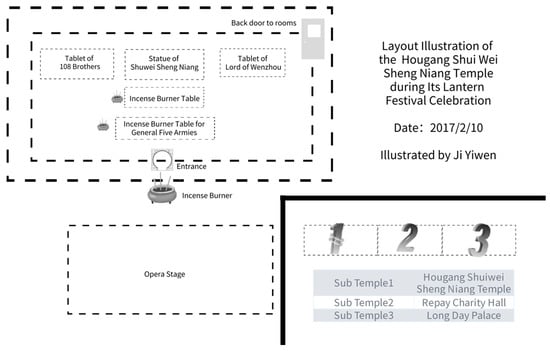

The Hougang Shuiwei Sheng Niang Temple is part of a united temple called the Saintly Hall of Heavenly Virtue (天德圣堂). It shares space with the Hall of Good Deeds for the Repayment of Virtue (报德善堂) and the Palace of the Endless Heavens (长天宫). The Hougang Shuiwei Sheng Niang Temple is on the right side of the united temple after entering the main gate (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Open area of the courtyard between the temple and the opera stage.

The Shui Wei Sheng Niang Temple holds a lease, which was extended from 2011 to 2020. The fees associated with this extension are colossal, and a fundraising announcement is prominently displayed on the wall of the hall. Over its 80-year history, the temple has survived relocation and is still running well. It faces some problems, like the imminent expiration of its 30-year lease. The temple committee has devoted much wealth to resolving the problem of their land lease. In 1981, the lease extension fees cost several million; in 2011, it was another very large amount, which the committee has been postponing paying for almost 10 years. These efforts reveal the willingness of the temple membership to make many sacrifices to preserve the temple.

The sub-temple consists of two halls and looks like a small hill from the right side. Only the front building is open to the public. Another building serves as the resting space for the temple committees. Meanwhile, there is a public space around the main gate. The celebration of the Lantern Festival is performed in the open courtyard area between the temple and the opera stage. The nearby stage is built to hold operas during festivals, as is the tradition (See Figure 1).

There are three incenses burners in the courtyard, along with two side censers for the Lord of Heaven (天公) on the walls. Two incense burner tables are in the middle of the hall. The one in front is for the Generals of the Five (Spirit Soldier) Armies (五营将军). The one behind is for the 108 Brothers (a group of heroes who are said to have drowned at sea), Shui Wei Sheng Niang, and the Lord of Wenzhou. All the deities’ names are listed on a yellow plastic plate. The tablets for the 108 Brothers and the Lord of Wenzhou are placed to the left and right of the statue of Shui Wei Sheng Niang, respectively, which is in the middle of the altar (See Figure 1).

3.3. Rituals

There are three main annual celebrations held at the Hougang Shui Wei Sheng Niang Temple: the Lantern Festival, the Hungry Ghost Festival, and the goddess’ birthday during the Lower Yuan Festival (下元节) (15th day of the 10th lunar month). The Temple Committee and the Keeper of the Incense Burners (炉主) organize all these events.2 All three annual anniversaries are presided over by Daoist Master Wang Xiaoxiang and his colleagues. The Lantern Festival is celebrated on the fourth and the 14th days of the first lunar month. On the 14th and 15th day of the seventh lunar month, the Hungry Ghost Festival is held. The goddess’ birthday during the Lower Yuan Festival is celebrated on the 14th day of the 10th lunar month. These dates were fixed by the present Daoist master’s previous generation.

As for the daily burning of incense, every visitor should burn 18 sticks of incenses: three for the censer in front of the entrance, five for the Generals of the Five Armies, and three each for Shui Wei Sheng Niang, the Lord of Wenzhou, and the 108 Brothers. Then, five more sticks of incense should be burned for Shui Wei Sheng Niang, and two should be burned for the Duke of Heaven.

For the Lantern Festival Celebration in 2017, the activities began at 10:00 A.M. Three Daoist masters arranged the altar and the ritual space before noon. The ritual is called sending off the memorial (进表). There were 35 memorials in total, representing the 35 families who prayed for the peace of all their family members. The Daoist masters stood in the middle, led by Daoist Master Wang Xiaoxiang, wearing a black cap. The other two masters accompanying him wore red caps. In front of them was a table covered with offerings, including chicken, pork, rice, and liquor. The families present followed the movements of the Daoist masters, praying on bended knees on grass mats and bowing to the ground.

It is said there used to be a procession of the goddess, but this is no longer allowed. The rites of “crossing the fire” (越火) used to be held during the procession, especially during the leap-year months. Coals would be burned from red to blue, and then a talisman would be burned over the fire before all the participants lined up to cross the fire. Master Wang Xiaoxiang attended one such fire-crossing ritual on his father’s shoulders when he was three or four years old.

After the ritual, a Hainanese opera performed in the afternoon. The opera already performed the night before. The whole performance lasts for two days and nights. However, very few people were in the audience. The production was dedicated to the deities.

In the afternoon, after a rest, the Hainanese opera performers reapply their makeup and get dressed. That night, they performed a Hainanese opera called Two Bridal Sedan Chairs. Before the performance, they burned incense to the tablet of their theater god, Huaguang dadi (华光大帝). The god’s image was made with paper tablets and four baby dolls, laid in pairs alongside the paper tablets.

Later in the night, the organizer started to hang vegetables on a beam to welcome the Hainan Lion Dance performance. The Hainan Lion Dance performance had not been presented in Singapore for many decades. The Hainan Lion Dance troupe arrived when the Hainanese opera was still on stage. The performance by the Guangwu Martial Arts Team (光武武术团) in front of Shui Wei Sheng Niang was their first show in 40 years. After “picking up the vegetables” (采青), which is a part of the performance, they visited the other two sub-temples before starting to worship Shui Wei Sheng Niang. Two Hainan lions, which traditionally have red bodies, danced together with two other Foshan lions. The audience clapped with joy while watching the Lion Dancers peel oranges. In the end, the oranges were peeled and laid out to form the Chinese phrase “May your incense fire be abundant,” signifying prosperity for all (香火鼎盛).

3.4. Networks

As mentioned before, the goddess in the Hougang Shui Wei Sheng Niang Miao is called the Secondary Madam of Shui Wei Sheng Niang. There are two other incarnations of Shui Wei Sheng Niang: the Major Madam (水尾圣娘大婆) and the Third Madam (水尾圣娘三婆). I interviewed one Taoist and one opera actress at the temple3. They did not mention the difference between these three deities. It is said that the Third Madam is the secondary god of the Hainan Mazu Temple, while the Secondary Madam of Shui Wei Sheng Niang is also worshiped at the Yan Kit Village Chinese Temple (Leong et al. 2017, p. 1). Thus, these links between incarnations of the goddess and her god statues may reveal alliances between these important Hainanese temples.

The Hougang Shui Wei Sheng Niang Temple, like the Yan Kit Village Chinese Temple, no longer has any connection with its mother temples in China. While the Yan Kit Village retains some contact with the other Hainanese temples in Singapore, including the Hougang Shui Wei Sheng Niang Miao and the Dou Tian Gong Temple in Jurong West and the Xunxing Old Temple (淡滨尼顺兴古庙) in Tampines, it is said that all the Shui Wei Sheng Niang temples run independently and serve their own Hainanese communities. However, the Hougang Shui Wei Sheng Niang Temple is a member of the broader official network of Daoist temples in Singapore. It is an ordinary member of the Daoist Federation (Singapore).

In conclusion, although currently the Shui Wei Sheng Niang Temple is a united temple that shares a land lease together with the other temples, it still keeps his own autonomy.

4. Life History of the Hainanese Daoist Master and Hainanese Opera Singer

To better understand local autonomy, it is important to delve into the religious professional’s individual life history. One is Daoist Master, Wang Xiaoxiang, and another is Hainanese opera singer, Li Sanmei. Their life stories show how cultural identity is flowing through all their lives.

4.1. Hainanese Daoist Master Wang

Master Wang Xiaoxiang has been a Daoist priest for 40 years. He is a third-generation descendant of a Daoist family. His grandfather and his father are also Daoist priests. They were from Zhongyuan town (中原), Qionghai city(琼海市), Hainan Island. Wang’s father was the youngest of four brothers. In 1939, when the Japanese occupied Hainan Island, Wang’s father, together with his three brothers, left his hometown and went to Singapore. At that time, Hainan was not an independent province and still belonged to Guangdong Province.

Master Wang inherited his father’s duties and became a Daoist priest after his father’s death. This process was long and complicated. Wang graduated from Zhongzheng Middle School and then became a student in the Chinese Department of Nanyang University. In 1977, after serving in the army, he moved to the Netherlands. After several years of wandering, Wang returned to Singapore. His father told him that he would burn the Daoist ritual objects and scriptures and liturgies at home if Wang refused to become a Daoist master. Wang struggled with himself for three days and nights and finally decided that he did indeed have a deep relationship with the Dao. This spiritual breakthrough was not entirely clear, but he soon became a Daoist master under his father’s guidance. He studied the writings of Zhuge Liang (诸葛亮), Daoist metaphysics (玄学), and general cultural information (通书). Moreover, he worshiped daily at a shrine dedicated to the Sanqing (三清神; Three Pure Ones), the highest emanations of the Dao, within his home.

In 1985, Wang’s father passed away on the third day of the first lunar month. That day, Wang officially began his career as a Daoist priest. His primary responsibilities are to run Daoism like one would run a business. On Wang’s business cards, it states that his business includes worshiping the heavens, holding red and white affairs (i.e., both auspicious ritual events, like the festival of a goddess, and inauspicious events, such as requiem services during a funeral), and attending to temple needs. These temples are primarily those dedicated to Shui Wei Sheng Niang and the other Hainanese temples. He says that he performs temple rituals for six of the seven or eight Shui Wei Sheng Niang temples in Singapore.

According to Master Zhang, another member of the Daoist troupe, his own father got his Daoist title from the 63rd generation Heavenly Master Zhang Enfu (1904–1969), who lived in Taiwan and visited Singapore in the 1960s. In the 1970s, Master Zhang was initiated as the Lord of the Three and Five (三五都公), an ancient Daoist title, from the 64th generation Heavenly Master residing in Taiwan.4 He received his initiation certificate through the mail and went through the same process three or four times to acquire even higher titles. At last, he attained the title of Daoist Master of the Three Caverns of Supreme Clarity (上清三洞), which is the highest-ranking Daoist title in Singapore. He claims that only three other Daoist masters in Singapore have obtained this title. Although he had already obtained his title from Taiwan, in the 1990s, Master Zhang went to Longhu Mountain in Jiangxi Province, China, to acquire additional initiation certificates there.

Master Wang expressed that he is swamped with ritual work during the first lunar month. On the fifth day, one temple worships in Mazu. On the sixth day, he has rituals at another temple in Hougang. On the ninth day, he has rituals at the Woodlands Mazu Temple. On the 10th day, he goes to one of the Shui Wei Sheng Niang temples to celebrate the Chinese New Year. On the 12th day, he goes to the Toa Payoh Shui Wei Sheng Niang Temple, and on the 14th day, he goes to the Hougang Shui Wei Sheng Niang Temple.

He has returned to his hometown on Hainan Island over 20 times. His father was married and left his first wife in Qionghai, so he still has strong connections with relatives there. When his father’s first wife died, he and the other Hainanese Daoist priests of Singapore returned to perform a funeral for her. Master Wang mentioned that there are five to six Hainanese Daoist priests in Singapore, and 10 apprentices following the funeral practices. Master Zhang, however, gave a higher number, claiming that there are 30 to 40 Hainanese Daoist priests in Singapore.

4.2. Hainanese Opera Singer Li Sanmei

Actress Li Sanmei, who is in her forties, is the youngest actress in the Singapore Hainanese opera troupe (新加坡琼剧团). The Singapore Hainanese opera troupe is one of four Hainanese opera troupes in Singapore. Currently, it is the only one that still performs Hainanese opera for the temples.

Actress Li was born in Hainan, grew up in Malaysia, and has resided in Singapore for 20 years. She met her husband when she was traveling to Singapore on her own, and eventually married him and became a resident of Singapore. Her husband also helps with the affairs of the Singapore Hainanese opera troupe. Some of the actors and actresses of the troupe live in Penang and Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia. They are almost 70 to 80 years old. They travel to Singapore for the performances.

In her interview, Li mentioned that the Hainanese dialect culture is diminishing in Singapore:

At the time when I was working, someone introduced us and called me to help inherit the culture of Hainan. I worked hard to inherit the culture of Hainan. If not, our Hainanese culture will be on the way to extinction, so we are dedicated to this Hainan culture, and I mobilized the whole family, including my daughter, my son, and my son’s friends, to help the opera troupe.If I had not married in Singapore, no one would act like me to preserve Hainan culture. There were not many, very few, who work for this history and culture. The first time I came here, I [did] not even know how to do makeup. These sisters helped me and took care of me. Then I learned my way slowly. I am very grateful and honored. Because although I did not understand at first, they accompanied me. I valued this very much, and I could eat with them and help them pack up. Also, we will go to Hainan Island to perform, which will cost a lot of money.

Li explained that it is not easy to run an opera troupe. The troupe struggles to survive. If there are no performances, then the troupe makes no money.

Li also described her journey to become an actress, expressing her reasons for wanting to join the Hainanese opera:In the past 20 or 30 years, the leader of the troupe was very caring for us; even though it was not easy to make a profit. Because we must each care for our own family and lives, it is not easy to find funds to maintain the running of the opera company. This situation is different from those Hainanese opera troupes in China that have a full-time director who supports his staff members. The group leader, the male lead and the main actress are supposed to receive a regular salary here. It is hard to meet this requirement in such a multi-ethnic country. Hainanese opera will gradually go extinct. If we did not have this generation, we would already have nothing. That is to say, when my generation is finished, there will be no more Hainanese culture here.

Li had been seeking wealth since she was 16, but then she changed and tried to find inner peace through Buddhist practices. In addition to Buddhist chanting, her most important mission is to preserve Hainanese culture through participating in the Hainanese opera troupe.When I was in my teens, my father was in a Hainanese opera troupe. He did not support me. My adoptive father and my mother raised me. But my adoptive father did not help me either, so I ran to the Hainanese opera troupe to try to join it. I apprenticed for a long time. However, my father told me to go back home; even though the director had already enrolled me. In my father’s heart, when I was young, I struggled because he did not provide for my education. I grew up in a single-parent family. I had to work hard to make money. When I was 16 years old, I ran my own business. After 10 years, my business failed. Then I traveled to Singapore and met my husband. I married at the age of 30. It was quite late. Then, when I was almost 40 years old, I started to get back into preserving Hainanese culture.... I became an actress when I was not young anymore. I could not do it when I was young. I feel that every parent loves their child, but I am an exception. So, one’s path in life is inevitable because everyone will try to find their lost childhood back. My father did not educate me. Still, I have struggled to attain this position. Now I do not care how much I earn. If I am healthy and happy, everything else can be tolerated. Actors standing on the stage go through huge ups and downs, and the feelings they express are unimaginable. My life is different. I do not have a love of my father. And my mother’s love, it has gone, it is okay. My life is still better than theirs. Yes, I feel that I am living very well now, that is, there is a little regret, but there is no point in hating him. That is the most regrettable thing in life.

5. Conclusions

The Hougang Shui Wei Sheng Niang Temple has a history of over 80 years. The legends of Shui Wei Sheng Niang have multiple versions, which are transmitted differently in Singapore and Hainan Island. The relatively older version, accepted by the Hainanese Singaporeans, reveals that they migrated from Wenchang City, and have preserved the version of the legend found there.

The temple runs very routinely and has a professional committee. The committee has numerous committee members, all with generous characters. It has multiple divisions as well, such as finance and even public relations.

This case study shows that the core of the Lantern Festival celebration is the search for peace and prosperity. The temple fairs have been abandoned. However, some elements of the larger ritual event have been preserved. This finding indicates that there are cultural and ritual continuities within the dispersed Hainanese community. Many elements still join together in the Festival of the Goddess. Thus, the Hainanese opera troupe, the Guang Wu Martial Arts Lion Dancing Team, and the Hainanese Daoist ritual troupe, join together with the temple committee, the Keeper of the Incense and the Village Ritual Heads, along with the entire Hainanese community, in the celebration.

The life histories of the Daoist masters and the Hainanese opera singer described above show that both fate and self-will are very significant in individual life trajectories. The preservation or reinvention of traditional cultural forms in a modern and secularized country is not without hardship. These individuals have to earn a living while simultaneously engaging in a quest to maintain their ideals and preserve their cultural heritage.

Although very few younger people attend these ceremonies, and the villages diminished during the urbanization and relocation of Singapore, people of the Hainanese community still gather together for their traditional communal temple activities. People still have the autonomy to maintain their dialect-based identity in a modernized and secularized Singapore.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by Hougang Shui Wei Sheng Niang Temple and my supervisor Kenneth Dean and Koh Khee-heong. Special appreciation is given to my mother Shen Hongying, who accompanied with me to visit the temple first time in 2017.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Dean, Kenneth. 2003. Local communal religion in contemporary south-east China. The China Quarterly 174: 338–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, Kenneth. 2015. Parallel Universe: The Chinese Temples of Singapore. In Handbook of Asian Cities and Religion. Edited by Peter van der Veer. Berkeley: U.C. California Press, pp. 257–89. ISBN 9780520281226. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Shanyuan. 1996. The Emigration History of Hainanese in South East Asia 琼州人南来沧桑史. In Commemorate Journal of the Singapore Hainanese Guild House for Establishment of One Hundred and Thirty Five Year 新加坡琼州会馆庆祝成立一百三十五周年纪念刊. Singapore: Singapore Kiung Chow Hwee Kuan, pp. 263–64. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Ming Guang. 2012. External and Internal Perceptions of the Hainanese Community and Identity, Past and Present. Master’s thesis, National University of Singapore, Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Hue, Yuan Thye. 2013. History and Model: Research on the spread of Taoism and Buddhism in Singapore沿革与模式: 新加坡道教和佛教传播研究. Singapore: Global Publishing, vol. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Leong, Waikhei, Lu Chang, Tee Ming Yan, and Wang Mei Hui. 2017. SSA1208/GES1005 Group Essay. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, Yun Shu. 2004. The history of Shui Wei Sheng Niang 水尾圣娘史略. Available online: http://bbs.tianya.cn/post-hn-16329-1.shtml (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Yan, Yingwei, Kenneth Dean, Feng Chen-chieh, Hue Yuan Thye, Koh Khee-heong, Lily Kong, Ong Chang Woei, Arthur Tay, Wang Yi-chen, and Xue Yiran. 2020. Chinese Temple Networks in Southeast Asia: A Web-GIS Digital Humanities platforms for the collaborative study of the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia. Religions 11: 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Kang Tai. 1998. Culture Study of Hainanese Opera琼剧文化论. Beijing: Chinese Opera Press中国戏曲出版社. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Drawing on rich historical materials, including colonial-era documents, newspapers, interviews, and internal publications, Han’s thesis explores the identity of Hainanese communities in Singapore, following changes over time from both the external and internal perspectives. In his study, both official organizations of Hainanese communities, including the Hainan Guild Hall and the Hainan Mazu Temple, are discussed. |

| 2 | The committee consists of one lawyer, four trustees, five honorary chairmen, one chairman, one general executive, one deputy executive, one financial officer, two deputy financial officers, one auditor, one deputy auditor, one public relations officer, one deputy public relations officer, one clerk, two deputy clerks, and 35 committee members. Keepers of the Incense Burners are divided into a main keeper and a deputy keeper. Moreover, there are 12 community headmen (首事) who were chosen in 2016. |

| 3 | The names of the Daoist master and the Hainanese Opera singer are pseudonyms. |

| 4 | The 63rd Celestial Master Zhang Enfu (张恩傅) passed away in 1969. Since then, the question of who should be the 64th generation Celestial Master has provoked considerable controversy. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).