Equal Opportunity Beliefs beyond Black and White American Christianity

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Revising the Racial Order

1.2. Colorblind Racism and the Narrative of Equal Opportunity

1.3. Colorblind Racism and American Evangelical Cultural Scripts

1.4. Religio-Racial Consolidation or Generational Cleavage?

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Dependent Variable: Need for Equal Opportunity

“Our society should do whatever is necessary to make sure that everyone has an equal opportunity to succeed.”

“If people were treated more fairly in this country, we would have fewer problems.”

“One of the big problems in this country is that we don’t give everyone an equal chance.”

2.2. Primary Independent Variable: Racial/Ethnic, Generational, Religious Identities

2.3. Controls

2.4. Method of Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion and Future Directions

4.1. New Religio-Racial Solidarities and Cleavages

4.2. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alcoff, Linda Martin. 2003. Latinos, Asian Americans, and the Black-White Binary. The Journal of Ethics 7: 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobo, Lawrence D. 2011. Somewhere between Jim Crow & Post-Racialism: Reflections on the Racial Divide in America Today. Daedalus 140: 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bobo, Lawrence, and James R. Kluegel. 1993. Opposition to Race-Targeting: Self-Interest, Stratification Ideology, or Racial Attitudes? American Sociological Review 58: 443–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. 2004. From Bi-Racial to Tri-Racial: Towards a New System of Racial Stratification in the USA. Ethnic and Racial Studies 27: 931–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. 2010. Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States, 3rd ed. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. 2015. The Structure of Racism in Color-Blind, ‘Post-Racial’ America. American Behavioral Scientist 59: 1358–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodkin, Karen. 1998. How Jews Became White Folks and What That Says about Race in America. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R. Khari. 2009. Denominational Differences in Support for Race-Based Policies among White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian Americans. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 48: 604–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, Richard, and Jean Stefancic. 2012. Critical Race Theory: An Introduction, 2nd ed. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Doane, Ashley W., Jr. 1997. Dominant Group Ethnic Identity in the United States: The Role of ‘Hidden’ Ethnicity in Intergroup Relations. The Sociological Quarterly 38: 375–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgell, Penny, and Eric Tranby. 2007. Religious Influences on Understandings of Racial Inequality in the United States. Social Problems 54: 263–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, Michael O., and Christian Smith. 2000. Divided by Faith: Evangelical Religion and the Problem of Race in America. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, Michael O., Christian Smith, and David Sikkink. 1999. Equal in Christ, but Not in the World: White Conservative Protestants and Explanations of Black-White Inequality. Social Problems 46: 398–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, Cary, Luis Lugo, Alan Cooperman, Gregory A. Smith, Jessica Hamar Martinez, Besheer Mohamed, Neha Sahgal, Noble Kuriakose, and Elizabeth Podrebarac. 2012. Asian Americans: A Mosaic of Faiths. July 19. Available online: https://www.pewforum.org/2012/07/19/asian-americans-a-mosaic-of-faiths-overview/ (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Golland, David Hamilton. 2011. Conclusion: Affirmative Action and Equal Employment Opportunity. In Constructing Affirmative Action. The Struggle for Equal Employment Opportunity. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, pp. 171–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, Milton. 1964. Assimilation in American Life: The Role of Race, Religion, and National Origins. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hinojosa, Victor J., and Jerry Z. Park. 2004. Religion and the Paradox of Racial Inequality Attitudes. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 43: 229–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, Juliana Menasce, Anna Brown, and Kiana Cox. 2019. Race in America 2019: Public Has Negative Views of the Country’s Racial Progress; More than Half Say Trump Has Made Race Relations Worse. Washington: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, Matthew O. 1996. The Individual, Society, or Both? A Comparison of Black, Latino, and White Beliefs about the Causes of Poverty. Social Forces 75: 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, Matthew O. 2007. African American, Hispanic, and White Beliefs about Black/White Inequality, 1977–2004. American Sociological Review 72: 390–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatiev, Noel. 1995. How the Irish Became White. Routledge Classics. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Claire Jean. 1999. The Racial Triangulation of Asian Americans. Politics & Society 27: 105–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Nadia Y. 2008. Imperial Citizens: Koreans and Race from Seoul to LA. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jennifer, and Frank D Bean. 2012. The Diversity Paradox: Immigration and the Color Line in Twenty-First Century America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Taeku, and Efrén O. Pérez. 2014. The Persistent Connection Between Language-of-Interview and Latino Political Opinion. Political Behavior 36: 401–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jennifer, and Van Tran. 2019. The Mere Mention of Asians in Affirmative Action. Sociological Science 6: 551–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, William Ming. 2017. White Male Power and Privilege: The Relationship between White Supremacy and Social Class. Journal of Counseling Psychology 64: 349–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, Alex, Douglas Hartmann, and Joseph Gerteis. 2015. Colorblindness in Black and White: An Analysis of Core Tenets, Configurations, and Complexities. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 1: 532–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noonan, Allan S., Hector Eduardo Velasco-Mondragon, and Fernando A. 2016. Wagner. Improving the Health of African Americans in the USA: An Overdue Opportunity for Social Justice. Public Health Reviews 37: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, Peter J. 1985. The Social Teaching of the Black Churches. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Jerry Z., Kevin D. Dougherty, and Mitchell J. Neubert. 2016. Work, Occupations, and Entrepreneurship. In Handbook of Religion and Society. Edited by D. Yamane. Switzerland: Springer, pp. 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Pattillo-McCoy, Mary. 1998. Church Culture as a Strategy of Action in the Black Community. American Sociological Review 63: 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea, Juan F. 1997. The Black/White Binary Paradigm of Race: The ‘Normal Science’ of American Racial Thought. California Law Review 85: 1213–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, Alejandro, and Min Zhou. 1993. The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and Its Variants Among Post-1965 Immigrant Youth. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 530: 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, Karthick, Jennifer Lee, Taeku Lee, and Janelle Wong. 2018. National Asian American Survey (NAAS) 2016 Post-Election Survey. Riverside: NAAS. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, Clara E. 2018. America, As Seen on TV: How Television Shapes Immigrant Expectations around the Globe. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom, Susan Rakosi, and Niobe Way. 2004. Experiences of Discrimination Among African American, Asian American, and Latino Adolescents in an Urban High School. Youth and Society 35: 420–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewell, William. 1992. A Theory of Structure: Duality, Agency, and Transformation. American Journal of Sociology 98: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, Jason E., and Michael O. Emerson. 2012. Blacks and Whites in Christian America: How Racial Discrimination Shapes Religious Convictions. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Gregory A., Alan Cooperman, Jessica Martinez, Elizabeth Sciupac, Conrad Hackett, Besheer Mohamed, Becka Alper, Claire Gecewicz, and Juan Carlos Esparza Ochoa. 2015. America’s Changing Religious Landscape. May 12. Available online: https://www.pewforum.org/2015/05/12/americas-changing-religious-landscape/ (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Steensland, Brian, Jerry Z. Park, Mark D. Regnerus, Lynn D. Robinson, W. Bradford Wilcox, and Robert D. Woodberry. 2000. The Measure of American Religion: Toward Improving the State of the Art. Social Forces 79: 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swidler, Ann. 1986. Culture in Action: Symbols and Strategies. American Sociological Review 51: 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Marylee C., and Stephen M. Merino. 2011. Race, Religion, and Beliefs about Racial Inequality. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 634: 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Paul, Mark Hugo Lopez, Jessica Martinez, and Gabriel Velasco. 2012. When Labels Don’t Fit: Hispanics and Their Views of Identity. In Pew Research Center Hispanic Trends. Washington: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Western, Bruce, and Becky Pettit. 2005. Black-White Wage Inequality, Employment Rates, and Incarceration. American Journal of Sociology 111: 553–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, Melissa J. 2018. Complex Religion: Interrogating Assumptions of Independence in the Study of Religion. Sociology of Religion 79: 287–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, Melissa J., and Lindsay Glassman. 2016. How Complex Religion Can Improve Our Understanding of American Politics. Annual Review of Sociology 42: 407–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Bradley R. E., Michael Wallace, Annie Scola Wisnesky, Christopher M. Donnelly, Stacy Missari, and Christine Zozula. 2015. Religion, Race, and Discrimination: A Field Experiment of How American Churches Welcome Newcomers. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 54: 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yancey, George A. 2004. Who Is White? Latinos, Asians, and the New Black/Nonblack Divide. Boulder: Rienner. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Min. 1997. Segmented Assimilation: Issues, Controversies, and Recent Research on the New Second Generation. International Migration Review 31: 975–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Frequency | Mean or Percent | Range | Frequency | Percent | Range | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Age | <35 years | 487 | 16.4 | 0–1 | |||

| …we don’t give everyone an equal chance | 2969 | 3.389 | 1–5 | >34 years | 2482 | 83.7 | 0–1 | |

| …fewer problems if people treated equally | 2969 | 4.096 | 1–5 | |||||

| …make sure everyone has equal opportunity | 2969 | 4.442 | 1–5 | Gender | Women | 1661 | 55.9 | 0–1 |

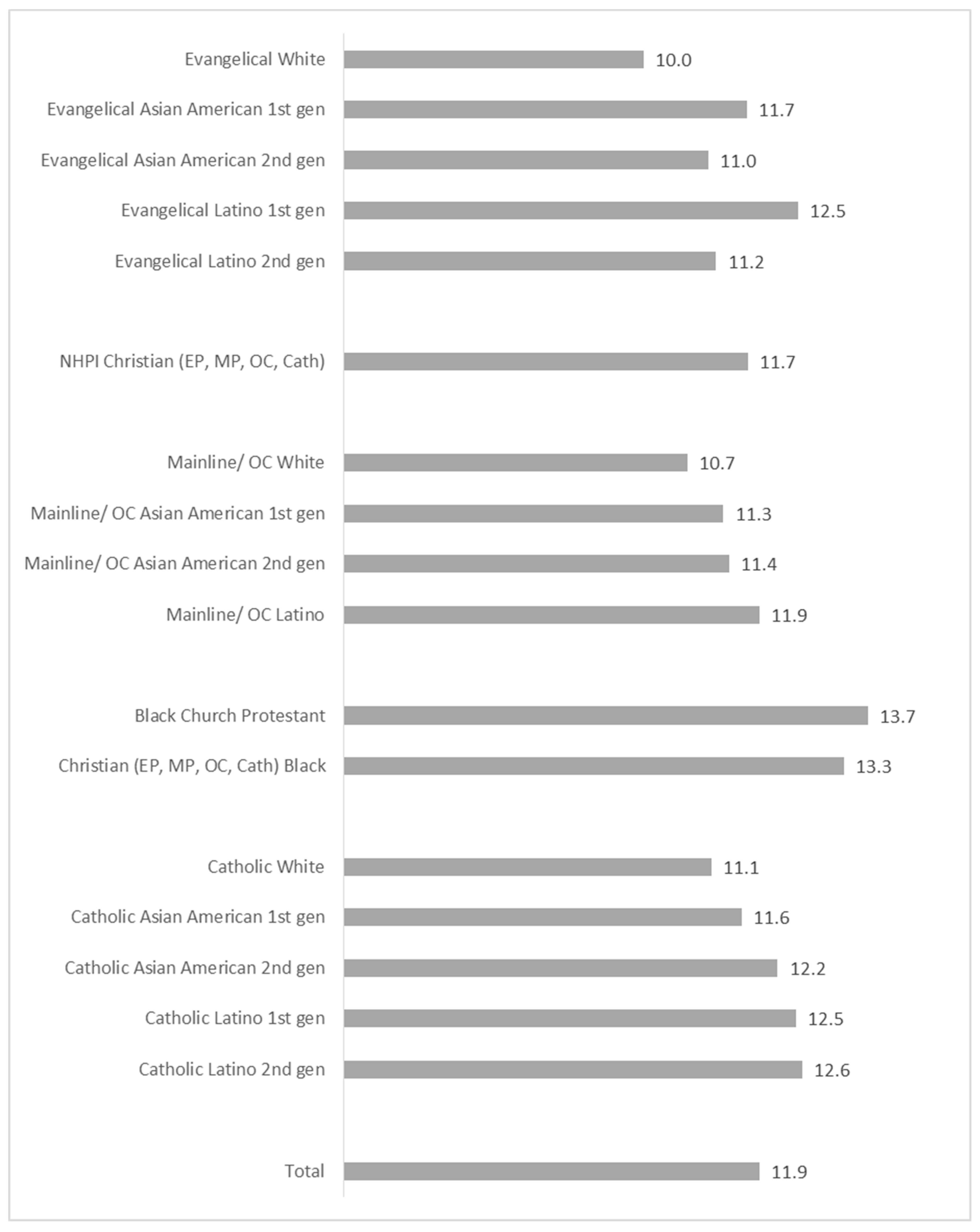

| Sum scale (“Need Equal Opportunity”) | 2969 | 11.927 | 3–15 | Men | 1308 | 44.1 | 0–1 | |

| Religio-Racial Identities | Educational Attainment | No schooling | 121 | 4.1 | 0–1 | |||

| Evangelical White | 90 | 3.0 | 0–1 | No GED | 351 | 11.8 | 0–1 | |

| Evangelical Asian American 1st gen | 326 | 11.0 | 0–1 | High school degree | 622 | 20.9 | 0–1 | |

| Evangelical Asian American 2nd gen | 153 | 5.2 | 0–1 | Some college | 524 | 17.6 | 0–1 | |

| NHPI Christian (EP, MP, OC, Cath) | 79 | 2.7 | 0–1 | College degree | 945 | 31.8 | 0–1 | |

| Evangelical Latino 1st gen | 58 | 2.0 | 0–1 | Graduate degree | 406 | 13.7 | 0–1 | |

| Evangelical Latino 2nd gen | 83 | 2.8 | 0–1 | |||||

| Mainline/OC White | 104 | 3.5 | 0–1 | Region | South | 658 | 22.2 | 0–1 |

| Mainline/OC Asian American 1st gen | 188 | 6.3 | 0–1 | Northeast | 287 | 9.7 | 0–1 | |

| Mainline/OC Asian American 2nd gen | 198 | 6.7 | 0–1 | Midwest | 323 | 10.9 | 0–1 | |

| Mainline/OC Latino | 75 | 2.5 | 0–1 | West (excl. CA) | 563 | 19.0 | 0–1 | |

| Black Church Protestant | 272 | 9.2 | 0–1 | CA | 1138 | 38.3 | 0–1 | |

| Christian (EP, MP, OC, Cath) Black | 43 | 1.4 | 0–1 | |||||

| Catholic White | 91 | 3.1 | 0–1 | Employment Status | Employed | 1422 | 47.9 | 0–1 |

| Catholic Asian American 1st gen | 376 | 12.7 | 0–1 | Not Employed | 1547 | 52.1 | 0–1 | |

| Catholic Asian American 2nd gen | 191 | 6.4 | 0–1 | |||||

| Catholic Latino 1st gen | 358 | 12.1 | 0–1 | Political Affiliation | Republican | 807 | 27.2 | 0–1 |

| Catholic Latino 2nd gen | 284 | 9.6 | 0–1 | Independent | 485 | 16.3 | 0–1 | |

| Total | 2969 | Democrat | 1677 | 56.5 | 0–1 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstd. Beta | S.E. | Sig. | Unstd. Beta | S.E. | Sig. | Unstd. Beta | S.E. | Sig. | ||

| Religio-Racial Identities | ||||||||||

| Evangelical White (M2 contrast) | −3.288 | 0.314 | *** | |||||||

| Evangelical Asian American 1st gen | 1.614 | 0.305 | *** | −1.674 | 0.213 | *** | ||||

| Evangelical Asian American 2nd gen | 0.730 | 0.345 | * | −2.558 | 0.267 | *** | ||||

| NHPI Christian (EP, MP, OC, Cath) | 1.349 | 0.404 | *** | −1.939 | 0.341 | *** | ||||

| Evangelical Latino 1st gen | 2.343 | 0.433 | *** | −0.945 | 0.371 | * | ||||

| Evangelical Latino 2nd gen | 0.918 | 0.393 | * | −2.371 | 0.323 | *** | ||||

| Mainline/OC White | 0.574 | 0.368 | −2.715 | 0.297 | *** | |||||

| Mainline/OC Asian American 1st gen | 1.049 | 0.329 | *** | −2.240 | 0.245 | *** | ||||

| Mainline/OC Asian American 2nd gen | 1.146 | 0.331 | *** | −2.142 | 0.250 | *** | ||||

| Mainline/OC Latino | 1.625 | 0.402 | *** | −1.663 | 0.335 | *** | ||||

| Black Church Protestant (M3 Contrast) | 3.288 | 0.314 | *** | |||||||

| Christian (EP, MP, OC, Cath) Black | 2.880 | 0.473 | *** | −0.409 | 0.417 | |||||

| Catholic White | 0.913 | 0.379 | * | −2.375 | 0.311 | *** | ||||

| Catholic Asian American 1st gen | 1.552 | 0.303 | *** | −1.736 | 0.209 | *** | ||||

| Catholic Asian American 2nd gen | 1.723 | 0.338 | *** | −1.565 | 0.252 | *** | ||||

| Catholic Latino 1st gen | 2.155 | 0.313 | *** | −1.133 | 0.215 | *** | ||||

| Catholic Latino 2nd gen | 2.184 | 0.315 | *** | −1.105 | 0.219 | *** | ||||

| Age | Over 34 y.o. | −0.688 | 0.137 | *** | −0.765 | 0.143 | *** | -0.765 | 0.143 | *** |

| Gender | Female | 0.449 | 0.098 | *** | 0.385 | 0.096 | *** | 0.385 | 0.096 | *** |

| Region | Northeast | 0.220 | 0.186 | 0.428 | 0.182 | * | 0.428 | 0.182 | * | |

| Midwest | −0.007 | 0.180 | 0.446 | 0.177 | * | 0.446 | 0.177 | * | ||

| West (except CA) | −0.200 | 0.151 | 0.268 | 0.156 | 0.268 | 0.156 | ||||

| California | 0.007 | 0.130 | 0.144 | 0.129 | 0.144 | 0.129 | ||||

| Educational Attainment | −0.187 | 0.036 | *** | −0.103 | 0.038 | ** | -0.103 | 0.038 | ** | |

| Currently Employed | −0.105 | 0.102 | −0.157 | 0.099 | -0.157 | 0.099 | ||||

| Political Affiliation | Democrat | 1.402 | 0.113 | *** | 1.097 | 0.112 | *** | 1.097 | 0.112 | *** |

| Independent | 0.700 | 0.152 | *** | 0.596 | 0.149 | *** | 0.596 | 0.149 | *** | |

| (Constant) | 12.850 | 0.353 | *** | 11.018 | 0.443 | *** | 14.307 | 0.379 | *** | |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.075 | 0.139 | 0.139 | |||||||

| N | 2968 | 2968 | 2968 | |||||||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, J.Z.; Chang, J.C.; Davidson, J.C. Equal Opportunity Beliefs beyond Black and White American Christianity. Religions 2020, 11, 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11070348

Park JZ, Chang JC, Davidson JC. Equal Opportunity Beliefs beyond Black and White American Christianity. Religions. 2020; 11(7):348. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11070348

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Jerry Z., Joyce C. Chang, and James C. Davidson. 2020. "Equal Opportunity Beliefs beyond Black and White American Christianity" Religions 11, no. 7: 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11070348

APA StylePark, J. Z., Chang, J. C., & Davidson, J. C. (2020). Equal Opportunity Beliefs beyond Black and White American Christianity. Religions, 11(7), 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11070348