Abstract

This article presents a new model of consolation that identifies five key themes: (1) an appeal to the inner strength of the consoland; (2) the regulation of emotion; (3) the attempt to preserve, re-write, and perfect the life of the deceased or, more generally, a person undergoing a radical psycho-social transition; (4) a ‘healing’ worldview, in which death has a legitimate place; and (5) reconnection with the community at the different levels of, for instance, family, society and humanity. The study is based on the Western tradition of written consolations. It partially confirms—and also supersedes—earlier studies of consolation based on different methods and smaller ranges of material. The article explores the applicability of the framework beyond the consolatory tradition by analyzing two versions of the Roman Catholic rite of anointing the sick. It argues for the heuristic usefulness of the model in the field of ritual studies, both by demonstrating the limitations of prevalent typologies of ritual and by suggesting a fresh look at ritual efficacy.

1. Introduction

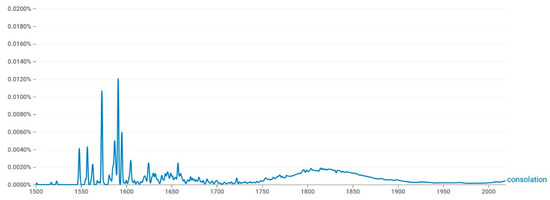

To many contemporaries, the word ‘consolation’ seems to suggest a questionable religious cultural baggage and a lack of valued attributes, such as activity and resilience. It is little wonder that other concepts, such as ‘coping’, are now used far more often to prescribe ways of dealing with loss. This impression can be confirmed by using quantitative research tools such as Google’s Ngram viewer: other than in standard locutions, such as in ‘consolation prize’, consolation is a word that we tend to avoid nowadays. As the peaks around 1550–1600 and the rise around 1750–1850 show, consolation is a word from the past far more than the present (Figure 1).1

Figure 1.

N-gram for “consolation”, English corpus 1500–2019, case-sensitive, no smoothing (https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=consolation&year_start=1500&year_end=2019&corpus=26&smoothing=0#, last accessed on 20 November 2020).

A certain uneasiness is discernible even in theological texts, which tend to denounce a ‘cheap’ and ‘insincere’ consolation, which is apparently tied to traditional consolatory motifs, from genuine solace. This contrast is particularly salient in German theology, with the easy availability of the contrasting words ‘Trost’ (genuine consolation) and ‘Vertröstung’ (insincere soothing); it appears to stem from theologians’ response to 19th and 20th critiques of religion (by Marx, Nietzsche, Freud, et al.) as a matter of illusion and compensation (see, e.g., Weyhofen 1983; Weymann 1989; Schneider-Harpprecht 1989; Langenhorst 2000; Schnelzer 2005; Schäfer 2012).

On the other hand, as opposed to the word ‘consolation’, the phenomenon has continued to matter. Recent work in the field of cultural geography has mined the philosophical and theological literature of consolation (see Jedan et al. 2019), and the medical professions continue to allude to the traditional adage “La médecine c’est guérir parfois, soulager souvent, consoler toujours” ([Medicine sometimes cures, often alleviates, always consoles], see, e.g., Keizer 2016).

However, in spite, or perhaps even because, of its ambivalent character, there have been a few notable efforts to conceptualize consolation. In recent decades, four such attempts stand out.

(1) At the end of the 1970s, in The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, Donald F. Duclow (1979) analyzed Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy (edition: Tester 1973). He interpreted (Boethian) consolation against the background of Frankl’s logotherapy. Consolation is a form of therapy that results in embracing the divine perspective on the world, “a majestic integral vision” (Duclow 1979, p. 340) that is beyond any limited perspective. From that divine perspective, one is led “to an introspective acceptance” (Duclow 1979, p. 342) of one’s situation, even if the external conditions remain unchanged.

(2) In 1983, Hans Theo Weyhofen published his study Trost: Modelle des religiösen und philosophischen Trostes und ihre Beurteilung durch die Religionskritik [Consolation: Models of religious and philosophical consolation and their assessment in the critique of religion]. Even if Weyhofen was unaware of Duclow’s (1979) article, he reached a similar conclusion: suffering results from a contradiction between the individual and the world. On one side, we find the interests, wishes and goals of the individual; on the other side, there is the world, which does not comply with those interests, wishes and goals. Consolation is the answer to the suffering that is caused by that contradiction. The goal of consolation is to eliminate the difference and to produce a reconciling identity. According to Weyhofen, the difference can be removed in two ways: first, by altering one’s interests, wishes and goals—whether by aligning them with ‘the world’ as it is (the Stoic solution) or, more radically, by a mystical renunciation of all interests, wishes and goals; and, second, by hoping for an eschatological transformation of the world when, later—perhaps in an afterlife—the world will finally be congruent with one’s wishes (Weyhofen 1983, pp. 249–52).

(3) In 2001, a team from Umeå University’s Department of Nursing, led by Astrid Norberg, published ‘A Model of Consolation’ (Norberg et al. 2001). The authors quote Duclow (1979), but seem unaware of Weyhofen (1983). According to Norberg et al., suffering is an existential loneliness, an alienation of the suffering individuals “from themselves, from other people, from the world, and from their transcendent source of meaning” (Norberg et al. 2001, p. 544). Consolation involves the reconstitution of communion, “a changed perception of the world in suffering persons” (Norberg et al. 2001, p. 544) in which the suffering Other is “acknowledged as a presence” (Norberg et al. 2001, p. 551). This can happen in silence, but an important role is attributed to a dialogue in which the individual can express their suffering and share it with someone else. Norberg et al. based their analysis on interviews, but it is clear that they relied ultimately on etic categories: the talk of “a changed perception” is clearly indebted to Duclow; in addition, with the concepts of ‘alienation’ and ‘communion’, the authors based their analysis on the work of the religious existentialist Gabriel Marcel. For his part, Marcel postulated “that deep in human beings there is a universal brotherhood that is revealed through a global feeling of a ‘we’ (communion)” (Marcel, quoted Norberg et al. 2001, p. 550).

(4) At the beginning of the 2010s, the psychologist and anthropologist of religion Dennis Klass published a series of articles in which he identified three key elements of consolation (e.g., Klass 2006, 2013, 2014; in what follows, I focus on Klass 2013):

With the element of community, Klass harked back to Norberg et al.’s (2001) analysis. His own empirical material was primarily the focused ethnography of a branch of a bereaved parents’ organization (Klass 1993). On the basis of his three key elements, Klass proposed a diagram of seven interlinked ‘aspects’ that constitutes the most detailed model of consolation so far: (1) “How the Universe works”; (2) “Place and power of the self”; (3) “Bond with the transcendent”; (4) “Meaning of death”; (5) “Family, community, cultural membership”; (6) “Meaning of the survivor’s life”; and finally (7) “Bond with the deceased” (Klass 2013, p. 133).The first element, encounter or merger with transcendent reality, is our bond with the transcendent reality (God in Western traditions) that is often connected with our bond or continuing bond with the dead person. The second element, a worldview, that is, a higher intelligence, purpose, or order that gives meaning to the events and relationships in our lives, is expressed in our assumptions of how the world works and what place and power we have in the universe. The third element is our membership in a community.(Klass 2013, p. 133)

It is noteworthy that the four conceptualizations (or models) of consolation rely on very different types of material. Whilst Duclow and Weyhofen study historical consolations, they do not envisage that the writing of consolations is a tradition that continues into the present day. By contrast, Norberg et al. and Klass rely on interviews and fieldwork, but do not connect their empirical research to the history of consolation before the twentieth century.

What is needed in this situation is a new, comprehensive study that focuses on the longue durée of consolatory texts up to the present day, and engages with the results of the empirical research undertaken by Norberg et al. and by Klass, as well as extensive literature on empirically-informed grief theory and therapy. In what follows, I will present a new conceptualization of consolation based on such work: the ‘Five-Axis Model’ of consolation.2

2. Corpus and Method

The approach taken by this study was inspired by the qualitative research methods developed in the social sciences, which is not usually applied to the analysis of historical material. More specifically, the study takes its cue from suggestions for textual data analysis (Hennink et al. 2011). As those authors emphasise, textual data analysis should be understood as a cyclical process, in which the tasks of code development, comparison, categorization, conceptualization, and theory development are closely interlinked. “Not only are they conducted in a circular manner whereby tasks are repeated during data analysis, but they are also often conducted simultaneously at different points in the analysis” (Hennink et al. 2011, p. 237). Another way of presenting this approach is to highlight its combination of the two movements in the ‘analytic spiral’ of developing theory (originally proposed by Dey 1993): working inductively from data to explanation, and grounding the emerging theory in the research material (Hennink et al. 2011, p. 238). Hennink et al. took their inspiration from a Grounded Theory Approach (for a recent summary see, e.g., Engler 2011), and in that respect, too, I have built on their suggestions.

For the present study, this means inter alia that the research did not start out from the existing models of consolation presented in Section 1; those models came into view only later, and then largely for testing purposes. At the same time, I did not deliberately avoid taking note of them; neither did I avoid looking at the secondary literature on the texts in my analysis. This is in line with recent developments of Grounded Theory, where practitioners today are far less worried—or even positive—about the inclusion of secondary literature than the founders of the theory (Glaser and Strauss [1967] 2009) were (see, e.g., Bryant and Charmaz 2019, especially the contributions by Kelle (2019), Gilgun (2019), Thornberg and Dunne (2019), and Martin (2019), all of whom distanced themselves from Glaser and Strauss with regard to the use of the literature). Moreover, the secondary literature played an important role in aiding my understanding of the texts, and the identification and confirmation of important themes and thematic linkages (see below).

The key attraction in venturing beyond customary strategies of interpreting historical texts in the humanities becomes obvious once we focus on two diametrically opposed ways in which (humanities-style) thematic analyses of texts are conducted. There is a stalemate between ‘historicist’ and ‘presentist’ approaches. On the one hand, proponents of historicist approaches argue the uniqueness of their sources’ problems and concerns (for the classic statement, see Skinner 1969), but it is unclear how ‘emic’ concepts and categories internal to the historical sources could ever be sufficiently useful to deserve the interest of a later time (leaving to one side the unresolvable problem that one can hardly operate in the terms of one’s sources, anyway). On the other hand, there is the opposite extreme of a rampant ‘presentism’ that looks at the past solely with an eye to solve today’s problems (much of the history-writing in analytical philosophy comes to mind). Sensible research practices tend to settle for a middle position between the two extremes (see, e.g., Rorty et al. 1984), but the question of the justification of the key concepts that feed into a thematic analysis remains unanswered (see Jedan 2019b). At this point, an approach inspired by social scientific research traditions might help. The circular research strategy, coupled with an expanding corpus, maintains a clear connection between the material that is brought in at different stages of the investigation; emerging categories can therefore justifiably take on an overlay of later (‘anachronistic’) terminologies because, and insofar as, a rationale can be given for the inclusion of later texts as relevant sources that are then allowed to modify the conceptualization. In this way, the approach can solve a problem that “traditional” thematic analyses in the humanities tend to downplay; namely, how to ensure that key terms or categories in a thematic analysis strike the difficult balance between being either too close to a specific source, or too general and anachronistic.

An account of the numerous stages in the analysis is beyond the scope of the present article, which is concerned primarily with the presentation and evaluation of the resultant model. Instead, in the next section, I will use a verification strategy that Hennink et al. (2011, p. 264) term a “return to data”, showing how the model thus developed fits and has a “strong foothold” in the data by analysing two historically and, in terms of culture, diametrically-opposed cases: a first century ce non-Christian consolation, and a Roman Catholic consolation from the late 20th century.

In the present context, I should also comment in more detail on the research corpus (i.e., the ‘data set’). The sample grew from an initial selection of eight Greco-Roman consolations along an historical vector (identifying important later consolations), but it also grew along a thematic vector. The analysis followed up on the important topics identified in the corpus, so that literature in other genres was included on the basis of thematic links, if those links were independently supported by the secondary literature. To give an example: the identification of emotional management as an important aspect of ancient consolations was confirmed by remarks in the secondary literature on those texts (see, e.g., Baltussen 2013), which also noted that such consolations are strikingly similar to modern grief therapy. Moreover, in the secondary literature, the suggestion is made that some currents of modern grief therapy might even have been directly inspired by ancient Stoicism. This led to an investigation of modern grief theory and therapy texts, and thus to an extension of the corpus beyond the consolations to include grief theoretic and therapeutic literature. In the circular manner advocated by Hennink et al., the concepts encountered in the analysis of modern grief theory were checked as to their suitability for the interpretation of older historical material, leading to the correction and fine-tuning of some codes. For instance, it turned out that not only modern theorists but even some ancient consolations speculate about a positive ‘function’ of grief or mourning (a point not seized upon by the secondary literature on the ancient texts); for the ancient authors, this justified a (limited) expression of grief. The phrase ‘policing grief’ was found to be eminently useful to denote the social aspect of the regulation of grief envisaged in many pre-modern texts. Additionally, concepts such as ‘symbolic immortality’ and ‘continuing bonds’ were found to be good codes for what is going on in a considerable subset (but not all) of the corpus (see Section 4, below).

At the end of the investigation, the corpus consisted of more than 200 primary texts of diverse backgrounds and literary forms. Among the earliest were consolatory and ‘metaconsolatory’ (Scourfield 2013) Greco-Roman philosophical texts from the fourth century bce onwards. To give a few examples: Seneca’s Ad Marciam (c. 40 ce; edition: Basore 1932) deserves pride of place, since it is the first sustained consolation (as opposed to shorter letters of condolence) that is extant. It represents the perspective of the Stoic school, which was founded during the Hellenistic period, and was highly influential during the early Roman Empire. Plutarch’s Ad Uxorem (c. 100 ce; edition: De Lacy and Einarson 1959) is, as the title suggests, a consolation written for his wife on the loss of their two-year-old daughter; it represents the perspective of Platonism. A third consolation is Pseudo-Plutarch’s Ad Apollonium, which might have been written as late as the turn of the fourth century ce (edition: Babbitt 1928). It is notable for offering a wealth of material, and for this reason, it has often been used to hypothesize the content of consolations from the Hellenistic era that are now lost. Plato’s Apology and Phaedo (fourth century bce, edition: Emlyn-Jones and Preddy 2017), even though they are in dialogue form and not dedicated exclusively to consolation, were an important reference point, both in ancient consolations and in the secondary literature, for the presentation of the model of a wise philosopher who is confronted by an unjust death sentence but manages to accept his fate, and even tries to console his friends and companions for the grief occasioned by his impending death. Also included were Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations, with a special focus on books 1 and 3 (c. 45 bce; edition: King 1927), which are not a generic consolation, but a text in which Cicero reflects on a consolation that he had written for himself on the loss of his daughter. Two texts were included from the Epicurean philosophical school, which provide arguments that appear to have circulated widely: Epicurus’ Letter to Menoikeus (c. 300 ce; edition: Hicks 1925) and Lucretius, De rerum natura, book 3 (c. 55 bce; edition: Rouse and Smith 1924).

From the writings of the New Testament, the corpus included Paul’s Letters to the Philippians and the Gospel of John. The corpus also included Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy (6th century ce; edition: Tester 1973), which was the eponymous text of the genre of consolations, despite being highly unusual in its prosimetric literary form. Also included were medieval and early modern texts that present confessional standpoints vis-à-vis consolation (e.g., Luther [1519] 1990, [1520] 1891; Erasmus 1539).

The corpus also contained modern and contemporary consolatory texts, such Henry Nouwen’s (1982) Roman Catholic consolation, a Christian grief memoir (Wolterstorff 1987), and a contemporary neo-Stoic grief memoir (Havermans 2019).

As I have stated above, the corpus extended beyond consolatory texts in the narrow sense3 by including other genres, for instance, rhetorical handbooks that advise on the composition of a consolation (e.g., Race 2019), biographies that thematize what defines an individual’s legacy (e.g., Boswell [1791] 2008), texts that ridicule consolations—e.g., Lucian, De luctu (2nd century ce; edition: Harmon (1925)) or Jane Austen’s novel Pride and Prejudice (Austen [1813] 1998)—, and texts such as essays that combine reflection upon, and personal reminiscences about, consolation (e.g., Boomsma 2014). The corpus also included texts that are based on the empirical investigation of grief and its therapeutic regulation, i.e., key texts of the 20th century, and contemporary grief theory and therapy, from Freud ([1917] 1957) onwards up to, inter alia, Worden ([1982] 2018; Machin 2009).

3. The Five-Axis Model of Consolation

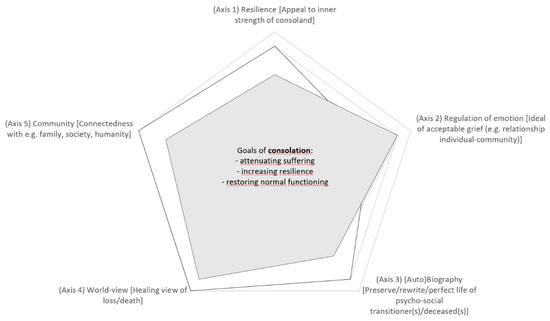

Five main categories have emerged from the analysis, and these can be described as the principal themes of consolation. The resultant model can be diagrammed as a radar chart with five thematic axes (hence, the ‘Five-Axis Model’). In the following, I will first present the Five-Axis Model to give readers an overview, after which I will explain the different components of the model and the considerations that led to the choice of a radar chart. Since it would be impossible to offer, in the limited space of an article, the series of conceptualizations that have resulted in the final model, I will instead illustrate the fit between the final model and the material by presenting the ways in which the categories fit two very different consolatory texts: Seneca’s Ad Marciam (which is, as noted above, the earliest extant sustained consolation), and Nouwen’s Letter of Consolation. If the model can be shown to fit such different texts as a first century ce Stoic consolation and a late-20th century Roman Catholic consolation, it might be fair to claim that the model can boast a good fit with the research material.

To begin with the overview, the resultant model can be depicted as follows (Figure 2):

Figure 2.

The Five-Axis Model of Consolation.

It should be noted that the model aspires to be a general model of consolation, covering different types of loss. This is consistent with the corpus, from the ancient Greco-Roman philosophical consolatory texts onwards. As Cicero had indicated, as early as the first century bce, the book market was replete with consolations for different topics such as poverty, the lack of social distinction, exile, political crises, slavery, infirmity, blindness and “every accident upon which the term disaster can be fixed” (Cicero, Tusculan Disputations 3.81–2 (King 1927, p. 323)), and all appear to have used comparable consolatory strategies. In many ways, the loss of life—either of a loved other or of oneself4—can be considered a ‘maximal’ loss, and thus a natural focus of consolation, but we should bear in mind that consolation is applicable beyond the sphere of death. Since Cicero, the point has been made frequently, most forcefully, perhaps, by Parkes and Prigerson (2010), who identify as the cause of grief radical “psycho-social transitions” [PST] that challenge our “assumptive world”. Again, death is one—albeit salient—representative of an array of challenges to our deeply-rooted assumptions. The Five-Axis Model signals its ambition as a general model by invoking Parkes and Prigerson’s fortuitous contemporary expression of Cicero’s observation with the coinage “psycho-social transitioner”. Used in juxtaposition to the “deceased”, the term allows for any form of loss, as well as for consolation directed at oneself (cf. the label “(Auto)biography” for axis 3).

To proceed with the illustration of, and argument for, the model, I will discuss, in turn, the five thematic axes:

(1) Consolations appeal to reservoirs of inner strength that the person to be consoled (the ‘consoland’) might possess; in so doing, consolations attempt to increase the consoland’s resilience. A typical strategy is to remind the consoland of how well they dealt with loss in the past, and to remind them of previous actions confirming their possession of important virtues, such as courage. If those virtues are applied in the current situation, the consoland can rise above the loss. Let me illustrate the ways in which the theme is present in our two exemplary texts. In the Ad Marciam, Seneca begins, in the very first paragraph, to emphasize that Marcia, his consoland, has a (now untapped) reservoir of psychological strength. He begins his letter by saying “If I did not know, Marcia, that … your character was looked upon as a model of ancient virtue, I should not dare to assail your grief” (Ad Marciam 1.1 (Basore 1932, p. 3)), and thus highlights her virtue and her strength. This is more than merely a literary convention; it serves a psychological, consolatory purpose. Seneca continues by referring to an important episode in Marcia’s life, when she acted courageously after her father’s forced suicide. Seneca sees this as confirming that she has the necessary courage to deal with her current loss: “But your strength of mind (robur animi) has been already so tested and your courage (virtus tua), after a severe trial, so approved that they have given me confidence” (Ad Marciam 1.1 (Basore 1932, p. 3)), and he returns to Marcia’s dealing with past loss again with the virtue term “the greatness of your mind” (magnitudo animi tui: Ad Marciam 1.5 (Basore 1932, p. 7)).

In his Letter of Consolation, Nouwen reminds his father time and again of his inner strength, and indicates, at the same time, how he must re-evaluate (and, indeed, already seems to have begun to re-evaluate) his sources of inner strength to cope with the loss of his wife. For instance:

Nouwen goes on: “Mother’s death opened up for you a dimension of life in which the key word is not autonomy, but surrender. … I am not saying that mother’s death made your autonomy and independence less valuable, but only that it put them into a new framework, the framework of life as a process of detachment” (Nouwen 1982, pp. 47–48).Father, you are a man with a strong personality, a powerful will, and a convincing sense of self. … One of your most often repeated remarks to me and to my brothers and sister was, ‘Be sure not to become dependent on the power, influence, or money of others. Your freedom to make your own decisions is your greatest possession. Do not ever give that up.’ This attitude—an attitude greatly admired by mother and all of us in the family—explains why anything that reminded you of death threatened you.(Nouwen 1982, pp. 46–47)

(2) Consolations attempt to regulate the consoland’s emotions. Consolations tend to presuppose a negative view, either of grief in general or of excessive, unchecked grief; against such unchecked grief they set an ideal of acceptable grief—a form of grief with which all, both consoland and their social context, can live. In Ad Marciam, Seneca recommends that Marcia restrain her grieving, because her excessive grief has made it overly difficult for her friends and family to share with her their positive memories of Metilius. However, those positive memories will help her to stay connected to the memory of her son. In this context, Seneca adduces numerous examples of well-known, even iconic figures in Greco-Roman culture, who represent either the ideal of extreme grief or the ideal of restrained grieving, and Marcia is asked to choose between the two grieving styles. A case in point is the (former) empress Livia, whom Marcia appears to have admired:

Similarly, Nouwen opposes, in A Letter of Consolation, unsuccessful and successful grieving styles. For instance:…yet as soon as she had placed him [Drusus] in the tomb, along with her son she laid away her sorrow, and grieved no more than was respectful to Caesar or fair to Tiberius, seeing that they were alive. And lastly, she never ceased from proclaiming the name of her dear Drusus. She had him pictured everywhere, in private and in public places, and it was her greatest pleasure to talk about him and to listen to the talk of others—she lived with his memory. But no one can cherish and cling to a memory that he has rendered an affliction to himself.(Ad Marciam 3.2 (Basore 1932, pp. 13–15))

Nouwen praises his father’s attempts to lead his life actively, and to take over roles in the family that had previously been fulfilled by the deceased (Nouwen 1982, pp. 21–23).The death of husband, wife, child, or friend can cause people to stop living toward the unknown future and make them withdraw into the familiar past. …. They start to live as if they were thinking, ‘For me it is all over. There is nothing more to expect from life.’ As you can see, here the opposite of detachment is taking place; here is a re-attachment that makes life stale and takes all vitality out of existence. It is a life in which hope no longer exists. … I think there is a much more human option. It is the option to re-evaluate the past as a continuing challenge to surrender ourselves to an unknown future. It is the option to understand our experience of powerlessness as an experience of being guided, even when we do not know exactly where.(Nouwen 1982, pp. 50–51)

(3) Consolations focus on the biography of the consoland. In some cases, where the consolation is directed at the author (e.g., Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy), the focus is the author’s autobiography. Grief and dejection highlight the incompleteness of the life lost and all that might have been; consolation, by contrast, aims to preserve the biography of the consoland, and highlights the ways in which the deceased’s life can be thought of as fulfilled and complete. Consolations regularly go to great lengths in ‘perfecting’ the life of the deceased. The message is that the life of the deceased has mattered, and continues to matter to the survivors. In the Ad Marciam, Seneca uses—as is characteristic of his time—the concept of virtue to show how the life of Metilius, in spite of his having died very young, can be re-evaluated so as to highlight the perfection, the completion that is manifest in it. Through his virtue, Metilius had achieved the best there was to life, he had “exhausted” life: “Whatever has reached perfection is near its end. … Undertake to estimate him by his virtues, not by his years, and you will see he lived long enough” (Ad Marciam 23.3—24.1 (Basore 1932, p. 85)). It is also significant to notice that, in his attempt to ‘perfect’ Metilius’ life, Seneca deviates from prevalent cultural norms. Whilst a military or political career should have been a natural focus of Metilius’ ambition, Seneca turns Metilius’ refusal of a public career into a virtue that allowed him to maintain close contact with his mother:

Similarly, Nouwen evokes, in A Letter of Consolation, the virtues of his mother. For instance:Your son was never removed from your sight; with an ability that was outstanding and would have made him the rival of his grandfather had he not been hampered by modesty, which in the case of many men checks their advancement by silence, he shaped all his studies beneath your eyes.(Ad Marciam 24.2 (Basore 1932, p. 87))

She is also presented as a devout Roman Catholic (e.g., Nouwen 1982, p. 64). Nouwen derives from his mother’s virtues the lesson to “accept her death as a death for us, a death that is not meant to paralyze us, make us totally dependent, or provide an excuse for all sorts of complaints, but a death that should make us stronger, freer and more mature” (Nouwen 1982, p. 57).Let me start with your own observation, which you have often made since mother’s death, namely, that she lived her life for others. … I too am increasingly impressed by her attentiveness to the needs of others. This attitude was so much a part of her that it hardly seems remarkable. Only now can we see its full power and beauty.(Nouwen 1982, pp. 54–55)

(4) Consolations elaborate a worldview in which death has a legitimate place. Death, for all its destructive power, is no tragedy in the grander scheme of things. Death can be accepted in spite of all the grief it causes. This provides a general framework in which to locate the specific death. In the Ad Marciam, Seneca underscores the unparalleled privilege of life. Being born is like travelling to a beautiful city. Just as travelling has its share of dangers and negative experiences but is valuable overall, so is life valuable overall and something for which to be grateful. A connected line of thinking is that death is part of nature, and not an evil (Ad Marciam 10.5 (Basore 1932, pp. 31–33)). In fact, the prospect of death intensifies life: “O Life, by the favour of Death I hold thee dear!” (Ad Marciam 20.3 (Basore 1932, pp. 69–71)). Perhaps an afterlife is possible for Metilius, but this would not be an eternal afterlife as in Christian theology; it would be for a limited time, until the cosmos is separated into its constituent elements and created anew. The evidence of that creative power in nature is a cause for joy, even if it entails a limitation of the individual’s lifespan: “Happy, Marcia, is your son, who already knows these mysteries!” (Ad Marciam 26.7 (Basore 1932, p. 97)).

In A Letter of Consolation, it is not a Stoic but a Christian worldview that is invoked by Nouwen, although equally present is the consolatory role of worldview that gives death a legitimate place in the grander scheme of things. In this vein, Nouwen claims that “our first task is to befriend death. … Befriending death seems to be the basis of all other forms of befriending” (Nouwen 1982, pp. 29–30). This intensification of life is reminiscent of Seneca. There is no parallel, of course, in the specifically Christian ingredients of the worldview, such as when Nouwen interprets the death of his mother in the light of the death of Jesus of Nazareth:

What strikes me most in all that is read and said during these days [the liturgy during the Holy Week] is that Jesus of Nazareth did not die for himself, but for us, and that in following him we too are called to make our death a death for others. … It is because of the liberating death of Christ that I dare say to you that mother’s death is not simply an absurd end to a beautiful, altruistic life. Rather, her death is an event that allows her altruism to yield a rich harvest.(Nouwen 1982, pp. 59–60)

(5) The fifth main theme in consolations is community. Consolations aim to ‘reweave’ disrupted ties with community. Community comes at different levels: this might be the family, society or nation state, or humanity as a whole. Seneca’s Ad Marciam tries to reconnect his consoland at all of the aforementioned levels: Marcia is called upon to cease neglecting her surviving children and her grandchildren, two of whom are the daughters of Metilius (Basore 1932). Marcia’s deceased father, Cremutius Cordus, is given an important role as a spokesperson in Seneca’s Stoic consolation, which ends in a prosopopoeia of Cremutius (Ad Marciam 26.1–7 (Basore 1932, pp. 91–97)). Passages such as the presentation of the (former) empress Livia (mentioned above), other women in Greco-Roman history, and important male politicians, emperors, and others, bring in the level of society, and passages that present exposure to loss as a common human condition seek to reconnect Marcia to humanity at large, and to make her realize that her loss is unexceptional and does not separate her from others. In Nouwen’s Letter of Consolation, the importance of connecting oneself to a community is similarly emphasized. Nouwen stresses the importance and novel quality that the relationship between himself and his father has acquired, paradoxically, because of their physical distance; a relationship that could supplement his father’s relationship to his other children and their families:

We have seen above that a sense of community is perceived at different levels, and this is also the case in A Letter of Consolation. The ultimate community, the community of Christian faith, is evoked in a transcendent vision: “During Eucharist, I prayed for you, for mother, and for all who are dear to us. I felt that the risen Christ brought us all together, bridging not only the distance between Holland and the United States but also that between life and death” (Nouwen 1982, p. 95).Physical and spiritual closeness are two quite different things, and they can—although they do not always—inhibit each other. The great distance between us may be enabling us to develop a relationship that you might not be able to develop with your other children and their families who live so close to you.(Nouwen 1982, p. 21)

To draw an interim conclusion, we see how both texts, Seneca’s Ad Marciam and Nouwen’s Letter of Consolation—rooted as they are in very different historical contexts and religio-cultural commitments—occupy the same categories in their consolatory effort.

So far, we have talked about consolations as consolatory acts in a written form. I can point ahead a little, and suggest that consolations are instances of a larger class of consolatory acts (as I will elaborate below, in Section 4, in an application of the Five-Axis Model to a type of ritual). That broader class includes gestures, rituals, oral communication, and so forth. We might then propose a more general definition of consolation as emerging from those themes; namely, that consolation is a family of practices and interventions (comforting gestures, rituals, oral or written communication, etc.) that (1) aim to reduce the distress produced by the experience of the limitations of human existence; (2) aim to foster resilience in the face of past, and (unspecified) future, losses; and (3) aim to restore normal human functioning as much as possible.

Of course, the proposed model, including the above definitions, should also be able to account for turns of phrase such as ‘finding consolation’. Finding consolation has the phenomenological quality of a gift. I suggest that such utterances should be viewed as an extended or metaphorical use of ‘consolation’ in the sense outlined above. In a sentence such as “He finds consolation in the forests around his home town where he used to take long walks with his wife”, the continuation of a joint important activity or the experience of a specific landscape are presented as if they were agents; it is as if a specific landscape had tried to reduce our distress with its splendor, or as if an activity we undertake was purposefully increasing our resilience. If this is correct, it would be possible to apply the model of consolation presented here to a wide range of phenomena, such as rituals or funerary art.

To continue the explanation of the Five-Axis Model, it needs to be acknowledged that the themes identified above are present to differing degrees in specific consolations (and, if my suggestion above is correct, in various other practices and interventions). For instance, a text such as Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations—which foregrounds reflection upon consolation—will probably contain fewer remarks about personal circumstances than a text that takes the literary form of a personal letter. However, remarks about personal circumstances need by no means be absent from the former. We can best think of the five categories or themes as ‘variables’ that continue to take significant (positive) values over time. The best means of depicting the five categories or themes is then by way of a radar chart, with the five categories or themes as axes. In this way we could characterize the specific profile of a consolation, and compare different consolations on the basis of pre-established criteria, e.g., counting and comparing the number of occurrences of categories, giving points to the intensity and specificity with which certain categories occur. For instance, the generic reference to the importance of biographical circumstances might count for less than the actual detailing of specific life-histories, character traits, and so on. A letter of consolation addressed to a specific individual might thus score higher on Axis 3 than a general treatise about consolation that merely gestures towards the importance of biography. Clearly, the ways in which to make such comparisons would need further discussion, but it is equally clear that the Five-Axis Model could be used to chart different consolatory ‘profiles’. The Five-Axis Model could serve as a heuristically useful tool, in that it invites researchers to realize specific consolatory profiles, and invites them to analyze why particular scores occur in relation to various axes.

4. Discussion

After presenting the Five-Axis Model, it is appropriate to pause and compare the new model to previous models of consolation. In this way, we can reflect on the specific profile of the results so far.

Klass’s model, which is the most detailed prior attempt, will serve as the main comparandum. To recapitulate: in its most elaborate form, Klass’s model distinguishes seven interlinked aspects of consolation: (1) “How the Universe works”, (2) “Place and power of the self”, (3) “Bond with transcendent”, (4) “Meaning of the death”, (5) “Family, community, cultural membership”, (6) “Meaning of the survivor’s life”, and finally (7) “Bond with the deceased” (Klass 2013, p. 133).

The Five-Axis Model suggests that some of the aspects listed by Klass have a lower degree of importance, and function not in isolation but in a wider thematic context. Perhaps most importantly, the theme of the ‘Bond with the deceased’ echoes Klass’s important work on continuing bonds (Klass et al. 1996). Klass was and is absolutely right that the topic of continuing bonds was unjustifiably ignored by Freudian psychoanalysis, and that the Freudian emphasis on breaking bonds with the deceased is a minority position, both in the longue durée of ‘western’ culture and in ‘non-western’ cultures today. However, the isolation of the theme of continuing bonds in the way that Klass does can threaten to turn into a universal criterion what is subject to a more limited consensus and is, moreover, regularly integrated in other themes. Although the recognition of continuing bonds is certainly widespread, there are authors in the history of consolation who are convinced that a resolute breaking of bonds with the deceased may be the best strategy.5 Furthermore, for many authors, continuing bonds are an important aspect of the presentation of an ideal of acceptable grief (axis 2). The passages from Seneca and Nouwen pertaining to axis 2 are two good examples of that. Of course, the topic of continuing bonds might receive additional support through other axes: a consoler might want to elaborate on the legacy of the deceased to which the consoland should relate (axis 3); a consoler might want to offer a worldview that explains the ontological status of the deceased, so that the latter can become an object of continuing bonds (axis 4), and might want to point to a community that can be instrumental for, or strengthened by, keeping alive the memory of the deceased (axis 5). All of this goes towards showing that the axes might be, in a highly-developed consolation, interconnected. It does not show, however, that continuing bonds must be a separate and universal ingredient of consolations.

Similarly, the Five-Axis Model suggests that other aspects which are isolated in Klass’s model should be viewed as parts of a larger theme. The aspects of the ‘Place and power of the self’ and the ‘Meaning of the survivor’s life’ do not have independent status; instead, ideas about the place and power of the survivor and the meaning of their life are regularly offered as parts of a normative view on grief, i.e., an ideal of acceptable grief (axis 2).

The Five-Axis Model also challenges the status and independence of the aspect ‘How the Universe works’. Consolations do not generally provide theories of the functioning of the universe. What they do offer is more specific: a ‘healing’ worldview that shows how death may be a legitimate part in the grander scheme of things (axis 4). Religious motifs may or may not be part of that worldview and can therefore include what is isolated in Klass’s model as the aspect “Bond with transcendent.” However, a bond with the transcendent is not a general feature of consolations; some consolations conceive of the divine as immanent and/or actively deny the possibility of transcendence. Seneca’s Ad Marciam is a relevant example. Seen from the perspective of the Five-Axis Model, Klass’s aspect “Meaning of the death” aggregates two different theme. On the one hand, this can be taken to allude to a worldview that attempts to give death a legitimate place in the grander scheme of things. In this understanding, the aspect is part of axis 4 in the new model. On the other hand, the ‘meaning of the death’ can refer to the specific circumstances of the loss that occasions the consolation. In the Five-Axis Model, this is part of axis 3 ((auto)biography), as an attempt to evoke the completion and perfection of a life. However, it is worth noting that specificity on this point is not a universal trait of consolations. Again, let me refer to the example of Seneca’s Ad Marciam: in its forty or more pages, there is no single mention of the specific circumstances of Metilius’ death. Being specific about the circumstances of the death is relevant for certain types of consolation, and may be particularly important today. Klass’s case-study material (a chapter of a bereaved parents’ organization) is an appropriate illustration.

Finally, the Five-Axis Model suggests a new category or theme that has not been identified in the earlier models: the attempt to regulate the emotions of the consoland by offering a normative view or ‘ideal of acceptable grief’ (axis 2).

If we take a step back, it is significant that the five axes of the new model—resilience, regulation of emotion, (auto)biography, worldview and community—offer a view of consolation that might be characterized (and critiqued) as ‘cognitivist’ or ‘intellectualist’. The cognitivist thrust of the model became particularly visible when I suggested (in Section 3) that the gift-like phenomenological quality of ‘finding consolation’ might be accounted for in terms of an ‘ideational’ link between the experience of consolation and the five axes (‘as if’). One might consider this cognitivist or intellectualist thrust of the model a disadvantage. However, I would like to point out that this approach does not put the Five-Axis Model at a disadvantage compared to the previous models. Duclos, Weyhofen, Norberg et al., and Klass all offered a thematic analysis of consolation.

Moreover, the Five-Axis Model does not, through its intellectualist thrust, systematically exclude certain phenomena. On the contrary, just as Norberg et al. (communion) and Klass (family, community and cultural membership) each acknowledged, so the Five-Axis Model recognizes consolation as a ‘relational’ phenomenon (community at different levels). In line with the history of consolations, in which authors from the ancient Stoics onwards have emphasized that grief and soothing grief are embodied phenomena, the Five-Axis Model does not exclude the aspect of ‘embodied cognition’.6

5. Applying the Five-Axis Model: Ritual

So far, I have presented the Five-Axis Model as the outcome of a thematic analysis of consolatory texts, and have discussed its specific profile vis-à-vis other available concepts or models of consolation. It remains for us to explore the ways in which the model might be applied. I propose to focus on a phenomenon that would normally be studied in the field of ritual or liturgical studies: the Roman Catholic sacrament of anointing the sick.

This area of application is, for a number of reasons, a logical continuation of our argument: (1) I commented, in the previous section, on the cognitive thrust of the Five-Axis Model. At the same time, I noted that, from the Greco-Roman philosophical discourses onwards, consolation was regularly claimed to involve the body. Using ritual as an area of application will help to give further detail on this, since rites are seen as a form of “embodied cognition” (Sax 2010, p. 8). (2) Specifically, the sacrament of anointing the sick is an interesting case: whilst it is a rite that has been associated for a long time with the end of life (so that a nexus of loss, death and consolation may be expected), its interpretation as consolatory is not conclusive.7 (3) The theological interpretation and performance of the rite of anointing the sick has undergone significant changes. In particular, the Vatican Council II has led to a radical re-interpretation (with more on this below). The changes are documented in detailed ritual prescriptions and interpretations, allowing us to illustrate the value of the Five-Axis Model as a tool for comparison.

What I will do in what follows is to compare the rite of anointing of the sick in two translations of the Rituale Romanum [Roman Ritual]: Weller (1948) and the vernacular editio typica produced by the International Commission on English in the Liturgy (ICEL 1990). For ease of reading, I will refer in the running text to Weller’s (1948) translation as ‘the old version’ or ‘the old rite’, and to ICEL (1990) as ‘the new version’ or ‘the new rite’. Moreover, I introduce the term ‘anointee’ for the person to be anointed.

5.1. Historical Background

As indicated above, the performance and theological interpretation of the rite of anointing has undergone marked changes. In the New Testament, James 5:14 (NIV) exhorts those who are ill to call on the elders of the church to pray over them and to anoint them with oil, suggesting the performance of a healing ritual directed at any form of illness. During the Middle Ages, the rite gained an unprecedented focus on those who are at the end of their lives and in immediate danger of death. From this period stems the characterization of the rite as an ‘extreme unction’ or ‘last unction’, which is still widespread today.8 The old version (promulgated by Pope Pius XI in 1925 and translated by Weller (1948)) is a good representation of the tradition before the Second Vatican Council. The old version puts great emphasis on the preparation of the ritual space and the production, transportation and disposal of the ritual objects. For instance, it presents as realistic the scenario that the priest may have to travel a long distance on horseback, and gives rules for such cases. The five sensory organs (eyes, ears, nose, mouth, and hands) are anointed, as well as (unless specific circumstances obtain) the feet. Each anointing is accompanied by a dedicated formula (Weller 1948, §§8–10).

The importance of the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) for the championing of the use of vernacular languages in the Roman liturgy is widely-known. In our context, a further change is important: the Second Vatican Council was key in nudging the interpretation and practice of the anointing away from its association with death, and in aligning it more closely with the New Testament sense of a healing ritual at times of illness (see e.g., ICEL 1990, p. 773; Kasza 2015). Vatican II resulted in new liturgic prescriptions, initially published in separate volumes for the different topics (tituli) and later brought together in a single collection. The ritual prescriptions surrounding the anointing of the sick were promulgated in 1972 under the title Ordo Unctionis infirmorum eorumque pastoralis curae. Following the Council’s stance on vernacular languages, officially recognized translations of the Latin version were considered as vernacular editiones typicae. The official English translation ‘Pastoral Care of the Sick: Rites of Anointing and Viaticum’ was canonically approved by the National Conference of Catholic Bishops in 1982, and was first published in 1983. A notable difference to the old version is that the new version gives far less attention to the preparation of the ritual space and the ritual objects. Furthermore, the anointing procedure itself is more contracted: there is a single anointing formula, which is enunciated during the anointing of the forehead and hands. The new version does allow for the anointing of additional parts of the body, but this is not accompanied by a dedicated formula, as was the case in the old version. Whilst the old version regulates that the oil should be wiped off with six pellets that must be disposed of in a specific way (Weller 1948, §1), the new version instructs the priest that “there should be a generous use of oil … it is not desirable to wipe off the oil after the anointing” (ICEL 1990, §107). Overall, there is more attention for the specific circumstances of the anointee. In that vein, different use cases are distinguished: anointing outside mass, within mass, and in a hospital or an institution. Likewise, the priest is offered different formulae for prayers and blessings to adjust the rite to specific cases (e.g., sick children, a person undergoing a major operation, etc.). All in all, there is a far greater role for the priest, the anointee, and his or her relations to shape the form that the ritual takes. In its most elaborate form, the actual anointing is the middle of a five-step ritual sequence. After (1) a series of introductory rites (greeting, sprinkling with Holy Water, an instruction, and either an individual penance (confession) or a collective penitential rite), there is (2) a ‘liturgy of the word’ that may combine the reading of a bible text with a short exegesis. (3) The anointing is, again, a multi-step procedure, beginning with a litany, the laying on of hands; followed by either a prayer over the oil or its ritual blessing in situ depending on the circumstances; then the anointing itself; and finally a prayer after the anointing. For the prayer after the anointing ritual, the new version presents a variety of options, depending on the specific circumstances of the sick person. (4) The anointing is followed by holy communion. Again, the new version offers different options for prayers. The ritual sequence is concluded with a blessing, for which—once again—different options are offered. For the purposes of our comparison, I will focus, in the new version, on the case of anointing outside mass, since this seems the best parallel to the old version.

5.2. Comparison

Let us proceed with a comparison of the old and new versions against the backdrop of the Five-Axis Model. I will also include a few pointers to differences between the authors of the old and new rites of anointing and a non-Christian author, i.e., Seneca, in understanding the five axes.

Regarding the first axis, resilience, we should note that the rites are undergirded by a specifically Christian understanding of inner strength. In line with the main thrust of Christian theology, inner strength must ultimately come, as it were, from the outside; it must derive from the divine being, and can be bestowed through the sacrament. This is different from, for instance, Stoic philosophy, where human autonomy is a far more prominent theme. Against this background, I would like to highlight, in the old rite, the call for “a good angel as a guardian” to protect the anointee and their family (Weller 1948, §5). §12 invokes God as a “tower of strength.” The anointing of the eyes, ears, nose, mouth, and hands, as well as the feet, is performed with dedicated formulae, all expressing the forgiveness of sins in the name of the Lord (Weller 1948, §§8–10). In the new rite, the first axis is dealt with in less detail than in the old version. We find references to the Godhead: in the litany, God is asked to “strengthen” the anointee (ICEL 1990, §121), a motif that is repeated a number of times. The forgiveness of sins through the anointing is expressed with a single formula that accompanies the anointing of forehead and hands (ICEL 1990, §124). In an optional part, “the experience of your [God’s] saving power” is invoked (ICEL 1990, §129A).

Concerning the second axis, the regulation of emotion, the message conveyed in the anointing is that human life is—compared to one’s spiritual welfare—only a limited good. There are more important losses and gains than one’s own life. There is, therefore, no space for dejection; the focus of the prayer is to continue in God’s service. Importantly, that attitude is, again, the result of divine intervention and help, whereas, for instance, a Stoic—such as Seneca—would attribute ultimate responsibility to the individual consoland. The old version uses the formula “free from all anxiety and distress” (Weller 1948, §5). The new version seems to use the word-field of consolation to indicate the called-for attitude. This becomes apparent in the description of the readings to be chosen for the liturgy of the word (ICEL 1990, §119B: “peace and consolation”). In §123, the word-field of consolation is used to characterize the divine origin of the needed attitude (God [the Father] as consoler and the Holy Spirit as Consoler). In optional parts, emphasis can be put on the attitude and virtues to be bestowed by God: courage, patience, hope and peace (ICEL 1990, §125A, §130C), and on the “confidence” with which the attendees may pray (ICEL 1990, §126B). An optional prayer reads: “keep us single-minded in your [God’s] service” (ICEL 1990, §129B).

Concerning the third axis, (auto)biography, the theme is present in both versions already through the sacramental symbolism of anointing that echoes baptism and confirmation (Weller 1948, p. 325; CCC 2019, §1523). The anointing thus underscores the continuity and “completion” or “perfection” of a life as a disciple of Jesus Christ and as a member of the church. The theme is thus closely aligned to the theme of community. In addition, in a more piecemeal fashion, both private confession and public penance serve to assist recall of one’s shortcomings, and to show how they are overcome through divine forgiveness, the intercession of the community of saints, and so forth. The emphasis on one’s shortcomings, on one’s sinfulness as being overcome, fits Christian theology’s overall more skeptical attitude towards human beings’ possibilities for autonomously perfecting their lives. In comparison, Seneca’s Stoicism exudes optimism that human beings can, out of their own resources, become fully virtuous, and in this sense become like God (ὁμοίωσις θεῷ).9 We should also bear in mind the literary character of the texts we are analyzing here, which offer a general liturgical template, not a consolatory text authored for a specific person. Nonetheless, the new version involves an autobiographical rehearsal taking place in a confession, or a reflection upon one’s shortcomings during a communal rite of penance. More specifically, the new version explicitly instructs the priest to “inquire about the physical and spiritual condition of the sick person”, to become acquainted with the family and friends of the anointee in addition to other attendees, and to involve the anointee and others in planning the celebration, “for example by choosing the readings and prayers” (all ICEL 1990, §100, repeated §112). When private confession is to be part of the rite, the priest is instructed to give “suitable counsel; he should make sure that such counsel is adapted to the circumstances” (ICEL 1990, §302). In sum, the new version attempts to involve the anointee and their social context in the adaption of the rite to their individual situation and needs. The old version offers no comparable possibility of adjusting the rite to individual circumstances; there is only a suggestion of (auto)biographical specificity in the instruction that the priest “adds words of encouragement” (Weller 1948, §4). However, we should bear in mind that, in the old version, the penitential rite is considered to be independent of the sacrament of anointing, whereas it is an integral part of the new version.

As to the fourth axis, namely worldview, both versions of the anointing rely on the (Augustinian) understanding of the sacraments as visible signs of invisible, inward grace. The old version, however, is more explicit than the new one about the theological background: the dualism between the Godhead as the source of good in opposition to the evil forces of the devil. In this vein, we find mention of “all spirits of evil” (Weller 1948, §5) and “all power of the devil” (Weller 1948, §7), opposed by the Lord’s “holy angel” of peace (Weller 1948, §5). God is presented as creator (Weller 1948, §5), as almighty and eternal (Weller 1948, §5), and as redeemer (Weller 1948, §12). The grace of the Holy Spirit is invoked (Weller 1948, §12). The new version highlights the Godhead as the source of good, but is silent about the other side of the dualism. This results in fewer motifs on this axis: the Trinity is invoked with God the Father, characterized as “almighty”, Jesus Christ as “the only begotten Son”, and the Holy Spirit as “the Consoler” (ICEL 1990, §123). The humanity of Jesus Christ is mentioned (ICEL 1990, §123), and—in an optional part—reference is made to the “paschal mystery” (ICEL 1990, §118C).

Concerning the fifth and final axis, the liturgical prescriptions in both versions show the attempt to produce and evoke a community of faith, and to locate the life of the anointee in the community of the church. In effect, the sickroom is transformed into a church, and the people in attendance merge into a congregation. In the old version, the preparation of the sickroom for the ritual is prescribed in great detail (Weller 1948, §1). Bystanders are sprinkled with holy water and thus drawn into the rite (Weller 1948, §4). The anointee’s home and “all who dwell herein” are invoked (Weller 1948, §3). The fact that the anointee is a member of the church community and profits from its reservoir of grace is detailed: in addition to Mary and Joseph, “all the holy angels, archangels, patriarchs, prophets, apostles, martyrs, confessors, virgins, and all the other saints” are invoked (Weller 1948, §7). The new version, too, emphasizes the importance of community right from the preparation of the ritual. For instance, it highlights the importance of the sick person, their family, and the priest having become “accustomed to praying together” prior to the anointing (ICEL 1990, §100). In the introductory rite all present to be “gathered here in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ who is present among us” (ICEL 1990, §117). The laying on of hands on the head of the sick person is also important before the anointing: “with this gesture the priest indicates that this particular person is the object of the Church’s prayer of faith” (ICEL 1990, §106). Other invocations of community are relegated to optional parts of the liturgy. The officiant can thus, but need not, select the greeting “Peace be with you (this house) and with all who live here” (ICEL 1990, §81B), and can select a prayer in which the anointee “when alone” is assured “of the support of your holy people” (ICEL 1990, §125A). There are also mutually exclusive instantiations of the fifth axis: if a communal penitential rite is performed, a formula can be used by which “blessed Mary, ever virgin, all the angels and saints, and you, my brothers and sisters” are bound up into a single community (ICEL 1990, §118A); if a private confession is heard, the priest is directed to instruct the anointee about the “social aspect” of sin and forgiveness, as well as “the important role the sick have in praying with and for the rest of the community” (ICEL 1990, §303).

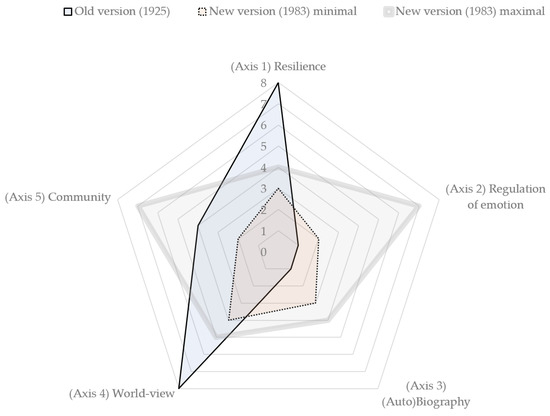

The above analysis suggests that the Five-Axis Model is a viable tool for the interpretation and comparison of rites. We should now try to use the model in a diagram to show the distinct “consolatory profiles” of the versions of the anointing. Of course, this would need more discussion than I can provide in the present context. In principle, we need agreed-upon criteria for the adequate separation of individual motifs, and for ways to ‘count’ them. We should ensure, perhaps through coding by different readers, that biases are counteracted, and that the overall analysis is complete. In the case at hand, we should also discuss ways of dealing convincingly with the large reservoir of optional texts in the new version. How should they be counted? Whilst questions such as these are evidently important, in our present context, where the application of the Five-Axis Model is performed with the goal of illustrating its analytical potential, we may perhaps gloss over them. Let us assume for the purpose of this illustration that the above analysis has been exhaustive and unbiased. Let me stipulate, then, that we count—on the basis of the above analysis—the occurrence of different motifs, leaving repetitions of the same motif out of consideration. Let me stipulate, further, that we ascribe one point for every mention of a motif or visible sign of it. As to dealing with the existence of optional parts in the new version, let us distinguish a ‘minimal’ version and a ‘maximal’ version of the new rite (the latter to be a version in which I seek to maximise the occurrence of motifs by choosing relevant optional texts, thus building the largest consistent set of consolatory motifs). The resulting diagram might look as follows (Figure 3):

Figure 3.

Consolatory profile of the anointing of the sick.

The figure gives us an intuitively-plausible picture of the old versus the new versions that can illustrate how, in spite of evident theological continuities, the rite of anointing has undergone marked changes in the wake of the Second Vatican Council. The old version of the rite focused specifically on the axes of resilience (with the performance of the physical signs of anointing) and worldview (by offering a detailed dogmatic–theological background). The old version did not pay much attention to the axis of (auto)biography; this is, in part, to do with the independent status of the penitential rite, but it would also suggest a predominant focus on the correct performance of a rite that is unvarying. The new version, by contrast, is highly flexible, and can be adapted to suit different circumstances and to highlight different consolatory themes. As a result, the minimal and maximal shapes of the new rite are starkly different. Concerning the themes of resilience and worldview, the new rite does not reach the detail of the old version. However, it can go above and beyond the old version in relation to the themes of the regulation of emotion, (auto)biography, and community.

5.3. Implications for Taxonomies and Accounts of Ritual Efficacy

I hope that this analysis of the old and new versions of the anointing of the sick can illustrate the ways in which the Five-Axis Model might applicable beyond the sphere of written consolations and similar literature. The analysis confirms the consolatory content of the liturgy for the rite of anointing.

We should therefore reconsider Weller’s claim that anointing the sick is “the sacrament of Christian consolation.” Arguably, a category of ‘consolation rites’ would fill an important lacuna in the prevalent taxonomies of ritual. In turn, the addition of a (new) category might lead us to a more fine-grained understanding of ritual efficacy. Subsuming a rite under a pre-existing category guides expectations about the possible efficacy of that rite.

To illustrate the nexus between taxonomies and efficacy, let me present the example of Erhard Weiher’s (2007) analysis of the anointing the sick. Weiher, a Roman Catholic priest and expert on end-of-life spiritual care, comments:

In this context, he also refers to the period of severe or terminal illness as “time in a lift-lock” (Schleusenzeit).The anointing of the sick, which in this case became an extreme unction (the same holds for the ‘viaticum’ as final sacrament) means, speaking ecclesiastically-theologically, that the seriously ill person is ‘transformed’ into one who is foreseeably dying, not without the hope, however, that the railroad switches have not been irrevocably thrown and that the course towards survival is still possible.(Weiher 2007, p. 174, my translation)10

It is striking to observe the ways in which Weiher appears to take over, as a matter of course, the conceptual framework of ‘rites of passage’ for his interpretation. It suggests that the efficacy of the rite lies in a transformation of the social status of the anointee. However, by Weiher’s own admission, a change of social status is not the point of the ritual. We could describe the underlying attitude, rather, as one of acceptance, of “que sera, sera”. There is still, in Weiher’s words, “the hope that the railroad switches have not been irrevocably thrown”, and, therefore—to draw out the obvious conclusion—that the ritual might not be effective after all. We could discuss further aspects of rites of passage that appear not to fit the anointing: for instance, there is no temporarily-disruptive dynamic, no sense of anomic “communitas” (Turner 1969); if the ritual sequence underscores anything, it is—as we have seen—continuity. Hospital personnel, family and others are called upon to carry on with their duties towards the patient. The axis of (auto)biography shows that the completion or perfection of a biography is envisaged within the familiar ecclesiastical setting of a community of faith.

Weiher’s interpretation illustrates the way in which the categorization of a rite steers expectations of ritual efficacy. It matters, then, if prevalent taxonomies do not closely fit the rite of anointing. The difficulty for any taxonomy vis-à-vis the new form of the rite of anointing is twofold: first, the sacrament of anointing is a complex sequence: existing taxonomies have a hard time capturing the common purpose of the different elements. Second, the theological background of the sacrament of anointing is the belief that death or survival are in God’s hands and cannot be predicted or influenced with certainty through a rite; therefore, the rite cannot ensure an observable outcome in terms of biological or social status (see again Weiher 2007, quoted above).

In order to illustrate the difficulties for current taxonomies, let us consider the “Ritual Studies Codes” for the Journal of Ritual Studies and the revised “Types of Ritual” proposed by Ronald L. Grimes (2017, appendices 2 and 3), who is considered by many a founding father in the field of ritual studies. As to the Ritual Studies Codes, type code D (Purification) is said to include confession (Grimes 2017, p. 10). Even though no mention is made of anointing, one could perhaps, with some difficulty, reduce that part of the sequence to a purification rite, but it would be hardly possible to interpret communion in that light. Type code H (worship), which includes “sacraments” (Grimes 2017, p. 10), is too unspecific: this would align the anointing of the sick with quite different types of sacrament, such as baptism and marriage. Concerning the taxonomy “Types of Ritual” (Grimes 2017, pp. 13–15) we encounter similar difficulties. We might consider “rites of mobility”, which include greeting and departing (Grimes 2017, p. 13, §7A). Subsuming the anointing of the sick under this category, however, would suggest a view of ritual efficacy according to which the anointing would have failed if the seriously ill did not, in fact, die. “Consecration rites” (Grimes 2017, p. 14, §12) are restricted to inanimate objects, and “magical rites” (Grimes 2017, p. 14, §16) would again suggest a view of efficacy aligned to the survival or non-survival of the seriously or terminally ill. Given this lack of suitable categories, it is hardly surprising that Weiher resorted to the category of “rites of passage” to analyze the anointing of the sick.

In this impasse, the positing of a category of “consolation rites” might be useful. The category would fit rites the object of which is the attenuation of suffering and the increased resilience of all concerned. Such consolation rites try to help restore normal functioning, as does the anointing of the sick with calling upon those in attendance to continue fulfilling their tasks. In such cases, the point of the ritual is not to mark or produce a new social state, nor is it—by means of magic—to ensure biological survival.

Moreover, the Five-Axis Model suggests more specific questions and criteria for a concept of ritual efficacy aligned with a category of consolation rites. Of course, I cannot pretend to discuss the concept of ritual efficacy in satisfactory detail here (for an overview, see, e.g., Sørensen 2006; Sax et al. 2010; Halloy 2015; for material aspects, see Galliot 2015).11 Suffice it to say that the discussion of ritual efficacy tends to be located between two standpoints, which we can call ‘ritual realism’ on the one side, and ‘ritual representationalism’ or ‘ritual symbolism’ on the other. The first standpoint holds that rites can transform reality; the second holds that rites do not in fact change the world, but merely symbolize or represent ideas, power relations, and so on (see e.g., Sax 2010). The difference between the two positions is at play in many theological discussions; for instance, when a (conservative) Roman Catholic theologian defends the position that the effect of a sacrament—such as the anointing of the sick—is a change “in the supernatural order” (see Cessario 2019, p. 298). On the other hand, secular religious studies tend to focus on observationally-accessible change. As Halloy (2015, p. 359) writes: “We can therefore say of a ritual or ritualized action that it is effective when it actually transforms the people that take part in it, i.e., when it changes not only how they are perceived by others, but also the way they think and feel about themselves and the world.”12 It is difficult, however, to identify suitably observable changes that are recognizable to members of the ritual community in question. This is where the Five-Axis Model can help again, by suggesting fine-grained, observationally-accessible aspects of ritual efficacy in consolation rites.

In the case of consolation rites (i.e., when the effect [efficiendum] of the ritual is to be consoled) we should investigate consolatory efficacy along the five axes: to what extent does a ritual (1) increase resilience and (2) regulate emotions? (3) To what extent does it help to preserve, rewrite, and perfect the lives of the participants? (4) Does it invoke a worldview in which loss and death have a legitimate place? And, finally, (5) to what extent does the ritual succeed in building a community at different levels, such as family, faith, or society, or even of humanity as a whole? As these five questions show, the single main effect [efficiendum] of consolation might subsume several coordinated efficienda. If we want to move beyond general claims of ritual efficacy, this would be the way to proceed, and the Five-Axis Model can show us what such a fine-grained analysis might look like.

Whilst these cursory remarks would need further development, the overall gist is clear: the Five-Axis Model is not only confirmed as a model that can elucidate the consolatory content of an exemplary rite; it is also heuristically useful, in that it proposes the tweaking of existing typologies and suggests new questions in an established field.

6. Conclusions

This article presented a new model of consolation: the Five-Axis Model. The examination of an unprecedented range of texts has generated ideas of what consolation is and what it tries to achieve. With this, the study supersedes previous conceptualizations or models of consolation, but it also underscores the partial correctness of earlier attempts by acknowledging themes that remain important in the new model, most notably the importance of community.

The Five-Axis Model, however, offers a clear step forward compared to the earlier models in at least three regards:

(1) The new categories of the Five-Axis Model allow a convincing aggregation and contextualization of aspects presented in the earlier models. For instance, the aspect of “Continuing bond with the deceased” (Klass 2013) may be part of an ideal of acceptable grief, and thus part of the consolatory theme of regulating emotion (axis 2). However, the study has also argued that continuing bonds are not a universal ingredient of consolation.

(2) The new categories are, in some cases, more specific: for instance, the study argues that consolation tries to evoke the ways in which death can play a legitimate role in the grander scheme of things (axis 4). Consolation does not (normally) offer a general theory about “How the Universe works” (Klass 2013).

(3) The visual representation of the Five-Axis Model in the form of a radar chart supports the comparison of consolatory content in texts and other phenomena. This has been illustrated with the example of two versions of the Roman Catholic rite of anointing the sick. The application of the Five-Axis Model to the rite of anointing has also shown that the model is heuristically useful in suggesting an addition to prevalent typologies of ritual, and in helping to generate more specific criteria of ritual efficacy.

For all those merits, a few cautionary remarks on the likely limitations of the model are in order. The study has looked at western material related to a Greco-Roman tradition of consolation, in a number of western languages (Greek, Latin, English, Dutch, German and French). There is a good justification for this limitation in the fact that the concept of consolation originated in the ancient Greco-Roman philosophical discourse. It is not unlikely that the Five-Axis Model can help us to interpret material beyond that western tradition, but—without further research—it is hard to say where the limits of applicability might be.

Funding

At a preparatory stage, the research was supported by a fellowship from the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study in the Humanities and Social Sciences in 2016–2017.

Acknowledgments

I have presented the research project at an annual workshop of the European Network on Death Rituals, in Fribourg, March 2020. My heartfelt thanks go to all of the participants for their questions and suggestions, especially to Linda Woodhead and François Gauthier (for the gift-like quality of consolation), Michael Houseman (for the typologies of ritual) and Eric Venbrux (for literature). My thanks go also to Martin Hoondert and Andrew Irving (liturgical studies), and to the three anonymous referees for the journal.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Austen, Jane. 1998. Pride and Prejudice. Edited by James Kinsley. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. First published 1813. [Google Scholar]

- Babbitt, Frank Cole, ed. and trans. 1928. Plutarch, Moralia, Volume II: How to Profit by One’s Enemies. on Having Many Friends. Chance. Virtue and Vice. Letter of Condolence to Apollonius. Advice about Keeping Well. Advice to Bride and Groom. The Dinner of the Seven Wise Men. Superstition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baltussen, Han. 2013. Greek and Roman Consolations: Eight Studies of a Tradition and its Afterlife. Swansea: Classical Press of Wales. [Google Scholar]

- Basore, John W., ed. and trans. 1932. Seneca, Moral Essays, Volume II: De Consolatione ad Marciam. De Vita Beata. De Otio. De Tranquillitate Animi. De Brevitate Vitae. De Consolatione ad Polybium. De Consolatione ad Helviam. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boomsma, Arie. 2014. Troost. Amsterdam: Stichting CPNB. [Google Scholar]

- Boswell, James. 2008. Life of Johnson. Oxford: Oxford University Press. First published 1791. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, Antony, and Kathy Charmaz, eds. 2019. The SAGE Handbook of Current Developments in Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]