Abstract

Although Tibetan rainmaking rituals speak of important aspects of both history and religion, scholars thus far have paid only biased attention to the rituals and performative aspects rather than the abundant textual materials available. To address that issue, this article analyzes a single textual manual on Tibetan rainmaking rituals to learn the significance of rainmaking in late Imperial Chinese history. The article begins with a historical overview of the importance of Tibetan rainmaking activities for the polities of China proper and clearly demonstrates the potential for studying these ritual activities using textual analysis. Then it focuses on one Tibetan rainmaking manual from the 18th century and its author, Sumpa Khenpo, to illustrate that potential. In addition to the author’s autobiographical accounts of the prominence of weather rituals in the Inner Asian territory of Qing China, a detailed outline of Sumpa Khenpo’s rainmaking manual indicates that the developmental aspects of popular weather rituals closely agreed with the successful dissemination of Tibetan Buddhism in regions where Tibetan Buddhist clerics were active. As an indicator of late Imperial Chinese history, this function of Tibetan rainmaking rituals is a good barometer of the successful operation of a cosmopolitan empire, a facilitator of which was Tibetan Buddhism, in the 18th century during the High Qing era.

1. Introduction

On occasions when rainmaking was needed in the past, although the instructions based on the drawing of Garuḍa mentioned in Cakrasaṃvara Tantra often produced excellent rain, they (the instructions) were somewhat crude. Now, since many opportune circumstances related to composing the new nāga ritual have appeared all on their own, it will probably be of help to others hereafter. Recently some are using the rainmaking method of setting up rain stones. However, because it is a heathen religious tradition, it is not right for those who have taken refuge in the Precious Jewels to practice it. If, having confidence in our Precious Jewels, we put into practice whatever instructions we know that come from sūtra, mantra, or oral instruction, it will rain. If it does not rain, given that it is the result of karma that sentient beings share in common, what recourse could there be? This is why there are stories of many years of drought even during the Buddha’s lifetime. Even if one only ostensibly resorts to a heathen method of rainmaking, it is a sign that one lacks faith in the Precious Jewels and karma(Thu’u bkwan III [1794] 1989, pp. 496–97).1

In the Fire-Dog year (1766 CE), a severe drought hit many parts of the Qing empire. There appeared a number of self-proclaimed rainmaking experts, but no one was successful in causing even a single drop of rain to fall. Eventually, people turned to Changkya Rölpé Dorjé (Lcang skya Rol pa’i rdo rje, 1717–1786), the state preceptor of Tibetan Buddhism for the Qing court, for help.2 Progressing in fits and starts through a process of trial and error, at last Changkya produced an instructive manual called Great Ocean of Happiness and Benefit,3 written around a nāga-centered ritual cycle. When the ritual was performed on the lakeside of Doloon Nuur in Inner Mongolia, Changkya and his disciples could claim success in healing the scorched lands (Thu’u bkwan III [1794] 1989, p. 496).4

The quote that opens this article is Changkya’s own advice regarding how to properly choose a rainmaking ritual, as shaped by his own trial and error on that occasion. Two things seem noteworthy about this story: that Changkya was a last resort for the people of the empire when it came to seeking relief from drought, and that Changkya, a cleric of the highest religious authority, was not ingenious enough to resolve the drought straight away, but had to work out for himself how it could be done through a process of trial and error. Irrespective of the authenticity of the details of the story, it seems that during the Qing times, Tibetan Buddhist leaders like Changkya did on occasion become agents to relieve environmental calamities in Qing territories. In addition to that, the measures that these religious leaders adopted reveal the complexity of the various religious and cultural traditions related to weather rituals, as shown in the aforementioned account.

This article is an attempt to seek out and examine any historical and religious meanings in the development of this “Tibetan” tradition of weather rituals during the Qing dynasty. This article argues, by examining the importance of weather rituals and investigating an example of one, that the pragmatic side of Tibetan Buddhist ritual had its own peculiar development at the time and that the reformulation of it eventually contributed to the popularization of Tibetan Buddhism in the area where it undertook evangelical activities. As a result, the role of Tibetan Buddhist clerics patronized by the Qing court as the officiants of such weather rituals became an important indicator, among others, of the cosmopolitan features of the Qing empire.

2. Qing Cosmopolitanism and Tibetan Clerics’ Roles Therein

In a basic sense, cosmopolitanism literally means “the idea that all human beings, regardless of their political affiliation, are (or can and should be) citizens in a single community” (Kleingeld and Brown 2019). However, there can be many different layers to cosmopolitanism and the idea can be used in various situations, such as when limiting the boundary of a single closed community, as in an empire or nation, or when designating a specific thematic condition, such as ideology or religion. In terms of Chinese history, cosmopolitanism can also have a number of different connotations. A good resource for recent discussions of the issue is Cosmopolitanism in China, 1600–1950, which demonstrates that a variety of cosmopolitanisms have emerged, such as Confucian cosmopolitanism or the cosmopolitan vision of the classical world shared by Chinese intellectuals in modern China (Hu and Elverskog 2016). For another example, cosmopolitanism is suggested also as an alternative conciliatory theme for a new understanding of modern China in order to break from the conventional history centered on continuous revolutions (Lu 2017). For this essay’s purpose, the focus will be on the type of Qing cosmopolitanism suggested by Johan Elverskog, a scholar of Mongolian Buddhism and its history—namely, the cosmopolitanism maintained and developed by religious and cultural connections throughout Inner Asia. The common experience and memory of Tibetan Buddhists were core elements in forming this type of cosmopolitanism for diverse people in the Qing Empire (Elverskog 2011; Elverskog 2013).5 The understanding of these elements is important to the history of both the Qing dynasty and Tibetan Buddhism because it is key to comprehending not only how the Qing maintained its dominion over Tibet and Mongolia, but also why Tibetan Buddhism was so successful in its evangelical activities during the Qing dynasty and afterwards.

Although we know of many cases wherein Tibetan Buddhism played some role in the cosmopolitan Qing empire, studies to date of the role or roles it played still leave a lot of room for investigation. Previous scholarly attentions to the role that Tibetan Buddhism played have been imbalanced to some extent by focusing more on relations between Tibetan clerics and the higher echelons of Qing dynasty, namely small numbers within the ruling class, such as emperors.6 With the development of new approaches in Qing studies and the increased availability of firsthand sources in Tibetan language, some scholars have begun to give their attention to Tibetan Buddhist literature and to address the roles that Tibetan Buddhist clerics played from a more Tibetan perspective (Ishihama 2011; Schwieger 2014; Oidtmann 2018). This approach can shed new light on what those clerics were actually doing at the various sites in the cosmopolitan empire in which they lived and worked. Nevertheless, these sources are also limited by choosing as their sites for consideration those that ostensibly have some connection with the imperial presence.

Prominent examples are activities at Beijing, Jehol, Doloon Nuur, and Mount Wutai.7 In his discussion of Qing cosmopolitanism, Elverskog looks at Mount Wutai and the Tibetan Buddhist clerics there, seeing the latter as players in Qing cosmopolitanism from marginal areas. It seems that scholars tend to assume too easily that the mere existence of these Tibetan clerics is evidence enough that they were agents in the cosmopolitan empire. For example, some scholars have introduced such religious figures as interlocutors who, given their multilingual abilities, mediated encounters between Tibeto–Mongol and Chinese Buddhists at Mount Wutai (Charleux 2015, p. 155). However, in some cases the accounts provided from the Tibetan side do not mention any direct contact with Chinese/Manchu religious or lay figures during their visits to Mount Wutai, and the stated purposes for the visits from their own perspective were simple pilgrimages to holy sites (Kim 2018, p. 273, n. 673). From the opposite direction, there is evidence that Qing elites outside the imperial circle possessed only a tangential understanding of Tibetan clerics, even though they were present at those sites.8

However, Tibetan silence and sparse evidence from Qing elites does not necessarily mean that Tibetan clerics did not have some functional role in Qing cosmopolitanism; questions about what role they played are still tenable. Evidence about the types of ventures that Tibetan clerics undertook in Qing areas might be found in their own accounts of their evangelical activities there, especially in relation to local chieftains and their subjects. Such Tibetan cleric visits to local elders are as important as gatherings of Tibetan clerics at a small number of imperial pilgrimage sites, because it shows that the dissemination of Tibetan Buddhism throughout the Qing territory went beyond those imperial sites. It is important that we look into what it was like for local people when they met with Tibetan Buddhist clerics, how they experienced them, and how much they maintained connections with them with respect to their religious and political activities. Among other things, the weather rituals that Tibetan clerics performed were not only demonstrable skills with which they appealed to emperors, they were also a means for making inroads among the peoples of Inner Asia.

3. Tibetan Clerics’ Weather Rituals and Sumpa Khenpo

Since the beginning of their priest–patron relationship,9 the rainmaking activities of Tibetan Buddhist clerics had been assumed to be an important virtuosity that helped build their relationship with the imperial authorities of China proper. The earliest relevant example of the importance of this skill to the relationship can be found in the presence of Tibetan and Kashmiri meteorological sorcerers at Qubilai’s Yuan court (Polo 1903, p. 301). Despite the obscurity of their religious identity, Tibetan sorcerers were specified as players who could provide black magic services to Qubilai. A similar case of the priest-emperor relations can be found in the early period of Ming dynasty. According to a Tibetan source, Langkar Sanggyé Trashi (Glang dkar Sangs rgyas bkra shis, d. 1413), the founder of Drotsang (Gro tshang) monastery (Ch. Qutansi 瞿曇寺) at the Sino-Tibetan border, performed a rainmaking miracle by throwing a wine container towards the direction where a big fire broke out when he visited the Hongwu emperor (1328–1398) of Ming dynasty (Brag dgon zhabs drung [1865] 1982, p. 171).10 In the story’s context, the feat was Sanggyé Trashi’s means of displaying virtuosity to his disparagers. At least the Tibetans assumed that performing such a miracle is a significant means of solidifying a cleric’s position at the imperial court.11 There are more Qing period witnesses of such activities by Tibetan Buddhist clerics who visited emperors. For example, the First Lamo Sertri Ngawang Lodrö Gyatso (La mo gser khri Ngag dbang blo gros rgya mtsho, 1635–1688) officiated a Miktsema Prayer-based rainmaking ritual for the capital city when he visited there in 1687 at the invitation of Kangxi emperor (1654–1722) (Lcang skya II 19C, folio 6a).12 The Second Gungtang Ngawang Tenpé Gyeltsen (Gung thang Ngag dbang bstan pa’i rgyal mtshan, 1727–1759) was also known for inducing rain upon drought-stricken Beijing when he visited there at the invitation of Qianlong emperor in 1759 (Bstan pa bstan ‘dzin 2003, vol. 1, p. 262).13 As mentioned above, Changkya Rölpé Dorjé, the state preceptor and Qianlong emperor’s trusted cleric, also conducted a rainmaking ritual, with specific modification to its protocols, on behalf of the empire at Doloon Nuur. No matter whether all these ritual activities mentioned in such stories truly happened or not, the telling of them demonstrates that the clerics’ virtuosity in such weather-related magics bore some weight with respect to the priest-patron relations between Tibetan Buddhists and political entities in China proper.

Now, turning a critical mind toward the imbalance in the focus of research discussed above, one may ask about Tibetan Buddhist clerics’ relationships with the emperors’ subjects in the same matter. The Tibetan clerics of the highest position who shared imperial connections may have been Dalai Lamas and Panchen Lamas, two prominent hierarchs of the Gelug school. A few of them did have contact with local leaders and their subordinates when they made trips to the Qing capital city. If we limit ourselves to the early Qing era, the Fifth Dalai Lama (1617–1682) and the Sixth Panchen Lama (1738–1780) did have such experiences. However, their travels were one-time events and encounters with local leaders were merely passing-through in nature.14 We need to examine a broader pool of Tibetan clerics which includes those who maintained close and continuous relationships not only with imperial authorities but also with their subjects.

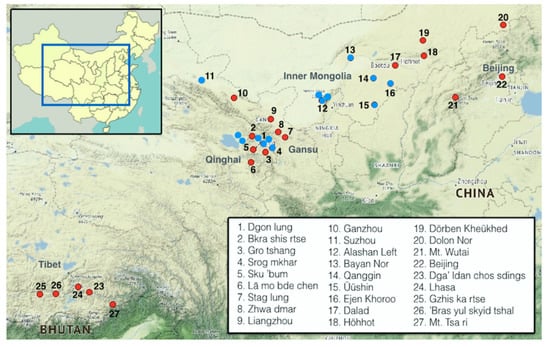

Among many candidates who had active evangelical ventures, one 18th century figure looms large for his rainmaking texts and performances: Sumpa Khenpo Yeshe Penjor (Sum pa mkhan po Ye shes dpal ‘byor, 1704–1788), a Gelug school incarnate cleric and a polymath of the period. In addition to the wide spectrum of his scholarly achievements,15 he was physically active in a large swath of the Qing territory during the High Qing era as shown in Figure 1. Whereas his activities in Central Tibet mostly had to do with his education during his 20s, his frequent sojourns in Qinghai, Gansu, and Inner Mongolia were undertaken upon invitations from local chieftains when Sumpa Khenpo was recognized as a senior religious figure later in his life. In particular, Sumpa Khenpo traveled to Mongolian territories at the invitation of the highest Mongolian political leaders—or at least religious figures subordinate to them. This shows that the 18th-century revival of Buddhism among the Mongols was materialized in the names of their most prominent political figures, who were all endorsed and registered by the Qing court as their highest authority. That is why the titles and names in Sumpa Khenpo’s accounts correspond perfectly to the Qing registration of the titles and ranks of Mongols, as attested by a comparison between Sumpa Khenpo’s autobiography and contemporary sources such as Menggu hui fu wanggong biaozhuan.16 For this reason, we can say that Sumpa Khenpo’s religious activities in these areas happened within the larger infrastructure constructed by the Qing cosmopolitan empire, although no direct presence of Qing authority is found in Sumpa Khenpo’s own accounts.17

Figure 1.

Main sites of Sumpa Khenpo’s activities. Blue dots indicate the sites where Sumpa Khenpo performed his rainmaking rituals. Generated by QGIS 2.18 (© Hanung Kim).

One of the reasons Sumpa Khenpo was popular among local people of these areas was his skill at rainmaking rituals. When remarking upon his popularity with respect to rainmaking, Sumpa Khenpo makes two assertions regarding his own rainmaking ritual. First, he says that his way of performing the ritual works better than that of other Buddhist or non-Buddhist wizards. Sumpa Khenpo had in fact competed with others in rainmaking and finally overcame other’s claims that his ritual was ineffective by producing successful results. Ultimately, Sumpa Khenpo claimed that his own method worked best.

Even all other Chinese, Tibetan and Mongolian monks and laymen, Buddhists and non-Buddhists, and even barbarians who possessed old texts or scrolls of rainmaking rituals exerted themselves for rainmaking. However, it was not easy work (for them) to make timely rain when common sentient beings are suffering due to their collective karma.(Sum pa mkhan po [1788] 1975–1979c, folio 150a)18

Second, Sumpa Khenpo was critical of learned scholars of both Inner Topics (i.e., Buddhist studies) and conventional sciences who were not capable of rainmaking and did not count rainmaking as one of their capacities (yon tan). Explaining that being able to produce timely rain is important not only for gaining temporal benefits but also for ultimate well-being, Sumpa Khenpo counts the yon tan of rainmaking among those that the learned should possess. In this way, Sumpa Khenpo extended the scope of a scholar’s trade by including a very practical and commoner-friendly skill.

Even though geshes of philosophy and those who are learned in several non-Buddhist topics achieved the higher capacities by training and eventually became beneficial (to sentient beings), such scholars (mostly) are not capable of rainmaking. (It is because) they do not count the knowledge of rainmaking as one of the capacities (they should grasp). However, the principal measure for activities of religions, politics and livelihood of all works of lives in the society is prosperity of plants and harvest. …… (And what makes it possible is) none other than timely rain.(Sum pa mkhan po [1788] 1975–1979c, folio 150b)19

Sumpa Khenpo’s Collected Works includes a work on rituals to avert natural disasters, which includes a rainmaking ritual as its penultimate work in the whole list.20 More than anything else, however, Sumpa Khenpo performed rainmaking rituals, mostly upon requests from local chieftains, and the times and places of his performances of rainmaking rituals are as follows (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sumpa Khenpo’s sites for his rainmaking rituals.

4. Tibetan Rainmaking Rituals and Their Observations

What makes Sumpa Khenpo an exemplary case is his composition of an extensive manual for weather rituals including rainmaking service. Before we begin a detailed examination of his manual, however, it might be helpful to provide general review of studies of Tibetan weather and rainmaking rituals, focusing on observations about textual manuals of the practice.

As Nicolas Sihlé recently explained, previous observations of Tibetan rituals—of which weather rituals are one important component—have mainly been on-the-spot investigations rather than textual studies (Sihlé 2010, pp. 35–36).21 The unique characteristics of weather rituals, such as its folk-oriented quality or its orality in transmission, may have pushed researchers in this direction (Cabezón 2010, p. 29, n. 3)22 and we see this as a trend quite clearly in studies of weather rituals of the previous generation. Toni Huber and Poul Pedersen catalog a number of these observations in a note in their 1997 article on Tibetan meteorological knowledge (Huber and Pedersen 1997, p. 592, n. 22).23 Among the more than a dozen observational records of “traditional Tibetan weather-making and weather-makers” they identify in the note, none delve seriously into any textual analysis of Tibetan weather ritual manuals; most are simple sketches of the performance of such rituals or their implication in the agriculture-centered Tibetan economy.24 Three among them—the works of Bell, Nebesky-Wojkowitz, and Woolf and Blanc—contain relatively detailed accounts about rainmaking activities, but their focus is neither exclusively on textual sources nor selectively on the historical or local diversity in rainmaking rituals.25

Many studies in Indian Buddhism have focused on weather rituals or related issues. A few of these connect their discussions to Tibetan cases. These are significant because they provide the origin and background for concepts used in Tibetan weather rituals, important not only for their external performative aspects but also for their inner philosophy and mindset.26 Others provide evidence of canonical connections for ritual manuals from Sanskrit to Tibetan (Bendall 1880; Hidas 2019). Although these works can be useful in attaining a general background knowledge for Tibetan cases, they can also be problematic if we use them to bind two remote cultures under the single rubric “Buddhism” and taking for granted that Tibetan cases are derivative of what Indians did.

As Tibetan studies continue to develop and grow, new scholarship has appeared that focuses on the topic of Tibetan weather rituals. One line along which this scholarship has run is the study of hail-protection rituals. Although they have hinted at some possible transmission of ritual manuals, earlier studies, such as the work of Klein and Khetsun, have yet to delve deep enough into the manual texts themselves (Klein and Khetsun 1997; Rdo rje don grub 2012; Klein 2018).27 So far the only monograph on the Tibetan rainmaking activities is the biographical account of Ngagpa Yeshe Dorje, a Nyingma rainmaking practitioner who was active in the Tibetan exile community (Woolf and Blanc 1994).28 Birtalan published an anthropological observation mainly of rain-averting rituals in northwest Mongolia that highlights the Mongolian appropriation of Tibetan weather rituals (Birtalan 2001). In another context, Molnár once gave a detailed historical and linguistic survey of “rain stone”-centered weather rituals throughout Inner Asia, but this work does not pay much attention to Tibetan or Buddhist traditions of weather ritual (Molnár 1994).

Another new research trend appears in the transition from studying the religious or philosophical studies of preeminent personages to studying their works on magic or sorcery. The study of Ju Mipham (‘Ju Mi pham, 1846–1912), whose “magic” instruction books (be’u bum) include some weather rituals, shows an example of this (Cuevas 2010, pp. 177–79).29 Another recent study takes as its subject Tsongkhapa (Tsong kha pa, 1357–1419), one of the most famous religious figures in Tibetan history, and a prayer to him used in magic rituals—Miktsema Prayer (Berounsky 2015).30 As we will see in the case of Sumpa Khenpo, a cycle of weather rituals based on Miktsema Prayer became well-known in northeast Tibet and Mongolia during the Qing era.31

More than anything else, the most pressing question for producing a thorough study of this topic should be how many “manuals” of Tibetan rainmaking rituals are actually available. Comprehensively locating literatures on the topic is beyond the scope of this article and will require long-term efforts, but we are not without promising indicators for potential future research on the topic. First, one of the biggest digital archives of Tibetan materials leads the way. The Buddhist Digital Resource Center (BDRC hereafter), a digital database of the nonprofit organization, allows topical sorting in its website database, and “rain making rituals (char ‘bebs cho ga; BDRC reference number T872)” is one of the categories they have helpfully provided.32 There are currently 63 works altogether within this category, and the number is continuously increasing. The BDRC’s collection of rainmaking rituals is certainly far less comprehensive than what really exist out there.33 But it is growing, and the data that they make available gives us a springboard for further inquiry and research. Second, interest in this sort of water-related ritual comes not only from etic cultural observers, but also from emic perspectives as well. Recently, the Golok Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture-based Nyanpo Yutse Conservation Association (Gnyan po g.yu rtse’i skye khams khor yug srung skyob tshogs pa) has compiled an anthology of Tibetan water-related works (Bkra shis bzang po 2014). Although the scope of the compilation is limited and the rationale behind it is interspersed with somewhat chauvinistic utopianism towards their own culture, this publication indicates that at least there is at present some indigenous desire to see these weather rituals.34

Even though observers have revealed their interest in Tibetan weather rituals, and in rainmaking rituals in particular, a paucity of attention has been paid to the textual materials related to them. Luckily, we have a long history of such materials existing in Tibetan literature.35 Now we will turn to one such text as an exemplar of Tibetan Buddhist weather rituals, taking one step towards a more comprehensive understanding of this type of ritual.

5. Highlights of Sumpa Khenpo’s Manual of Rainmaking Rituals

The title of the manual is Kha char ‘beb srung sogs kyi gdams pa gnam sa’i mdzes rgyan, meaning “A beautiful ornament of the heaven and earth: an instruction on summoning and averting snow or rain and other activities.” Although the title of the work indicates that the manual will cover a variety of meteorological-agricultural rituals, a number of aspects indicate that Sumpa Khenpo’s central interest is on rainmaking rituals. In the catalog of his Collected Works, Sumpa Khenpo refers to the same work as an abridged title Rituals of Rain Summoning and Others (Char ‘bebs sogs kyi cho ga), which indicates two facts that, first, Sumpa Khenpo himself puts rainmaking first among others and, second, he considers what he is instructing about is rituals (cho ga) (Sum pa mkhan po [1777] 1975–1979b, folio 9a).36 In Sumpa Khenpo’s Collected Works, this ritual manual is included as the sixth work in volume eight, having 38 folios (75 pages) in the traditional Tibetan book format (see Figure 2). As explained above, this manual of meteorological–agricultural rituals exists as the very last work of his Collected Works, the finale in the progressively sequential order of study subjects for Buddhist practitioners.37

Figure 2.

The beginning folios of Sumpa Khenpo’s weather ritual manual. Copies preserved in the Inner Mongolian Academy of Social Sciences at Höhhot, Inner Mongolia, China (© Hanung Kim).

The manual is comprised of four main parts. Their subdivisions are as follows:

- Introductory verses of praise (mchod brjod) and introduction (1b–4b, 4 folios)

- Rainmaking rituals (25 folios total)

- 2.1.

- Guhyasamāja Tantra (4b–12b)

- 2.2.

- Cakrasaṃvara Tantra (12b–13b)

- 2.3.

- Ways to depend on other deities (13b–23b)

- 2.4.

- Miktsema Prayer and Mahāmegha (23b–28b)

- Disaster averting rituals (10 folios total)

- 3.1.

- Deluge of rain (28b–30b)

- 3.2.

- Lightning and Hail (30b–35a)

- 3.3.

- Frost (35a–35b)

- 3.4.

- Blight and Insects (35b–37b)

- Colophon (37b–38a, 2 folios)

Although the length of each part does not necessarily indicate its magnitude, the number of folios allocated for each part shows that the rainmaking part takes up two and a half times the space as other topics. Only the rainmaking section is subdivided into subtopics to be discussed, whereas some of the other weather-related rituals are even lumped together into a single section. We can take these facts as evidence for rainmaking’s supremacy over other activities in the author’s mind. What follows are highlights from the introduction and the section on rainmaking rituals.38

5.1. Introductory verses of praise and Introduction

After its title, as most Tibetan literary works do, the manual begins with introductory verses of praise. The full translation of the verses is as follows:

I pay homage to the lamas and deities who propagate well-beingand increase the harvest that is the happiness and benefitof all beings by sprinkling raindrops of all desirablesfrom the cloud that is the maturation of their two stores (of merit and wisdom).

Because growing, maintaining, and increasing the store of resourcesOver the entire expanse of the earth depends on timely rain,Having risen in the eastern mountains, the full moon of noblest intentGlows and radiates limpid beams of advice for making rain.

Its power dispels the devil of torrential rain and the torment of heat,And fills the surface of the earth with flowers and ripe fruit.What else will all beings do than pass their time in amusementTasting this wholesome feast?(Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folio 1b)39

After the verses of praise, the main parts of the introduction begin. Sumpa Khenpo starts by juxtaposing soteriological and this-worldly pursuers as the beneficiaries of the good harvest that results from inducement of timely rain and prevention of other natural calamities (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folio 1b).40 Then he quotes passages from Mātr̥ceṭa’s Kaliyugaparikathā41 to explain the kinds of sins people have been perpetrating in this apocalyptic era of Kali-yuga42 and how these in turn bring about a series of natural disasters. At the center of such sinful acts lies disregard for Buddhist monks on account of heretical beliefs. That is to say, beyond the typical sinful acts associated with all life, the degeneration of Buddhist faith is the most serious cause of such calamities (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folios 1b–2b). Sumpa Khenpo then cites Bhāviveka’s Tarkajvālā to the effect that even though bodhisattvas produce the plenty of rain for people, those same people will not benefit from it unless they accumulate virtuous roots (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folio 2b).43 In this way, he exhorts his readers to take up active merit-making efforts and opines that having been struck by disasters is not an inevitable situation, but one that can be overcome with effort. However, Sumpa Khenpo also acknowledges that karmic roots might be too deep for even the Buddha himself to overcome them.44 He points out, for example, that there were several spells of severe drought even during Buddha’s time (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folios 2b–3a).45 Since even Buddha did not have power to avert shared karmic consequences, it might not be so strange that we have endured so many instances of natural calamity in this sin-stricken Kali-yuga. Sumpa Khenpo then goes on to enumerate other sinful acts prevalent in this Kali-yuga, such as losing faith in the Buddhist teachings, boasting that one is a high-level practitioner, or breaking vows (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folio 3a).

At that point, Sumpa Khenpo switches topics, moving from discussing the causes and recognition of calamities to measures for alleviating calamities, with a special focus on rituals for making rain. First, he admits that there have been successful cases of rainmaking based on true belief in Buddha’s teaching, but asserts that there are also many self-acclaimed experts who bring harm to deities or who resort to non-Buddhist practices like burning turtles or snakes alive and throwing rainmaking stones into ponds.46 Even though such heretical methods are by chance occasionally successful in rainmaking, they cannot be trusted.47 Sumpa Khenpo indicates as a danger associated with these unorthodox measures, the harming local deities and nāgas by using harmful substances or mantra texts, which might in turn induce further natural disasters. He singles out Nyingma, Bon, and other barbarian non-Buddhists (kla klo phyi rol ba) for making this mistake (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folio 3b).

Sumpa Khenpo then turns to the social aspects of relieving disasters. Political leaders are responsible for the effectiveness of rainmaking efforts: only when the king rules his subjects properly in conformity with Buddhist teachings, will it rain at the proper time and the harvest be good.48 Religious practitioners earnestly upholding their vows and lay people properly respecting those practitioners are also important conditions for successful rainmaking, as is the altruistic attitude (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folios 3b–4a). Finally, quoting the Buddha’s words from Ārya-Mahāmegha, Sumpa Khenpo again emphasizes that the proper attitude to have towards nāgas and local deities is not a posture of coercion, but one of love (byams pa) (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folio 4a).49

To close his introduction, Sumpa Khenpo again quotes passages from Kaliyugaparikathā to emphasize how important it is to cherish the Dharma and maintain morality for favorable weather conditions:

If, in this Kali-yuga, Dharma is abandoned and iniquity is cherished,(even) where the Lord causes rain to fall, few flowers and fruits will appear on the branches of fruit trees.Harvests will ripen in lands that have moist, fertile soil,Which is all due to the power of morality, observance, self-control, and piety (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folio 4b).50

Now Sumpa Khenpo has provided the religious and conceptual background for weather calamities and has suggested a fundamental solution for them, even for those of us who live in the apocalyptic Kali-yuga. Noting that no matter how well we follow his religious advice, temporary obstructions such as unfavorable alignments of planets and stars are bound to cause some such calamities. Sumpa Khenpo maintains that, in the end, his ritual manual is meant for those inevitable occasions (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folio 4b).

5.2. Manual for Rainmaking

Sumpa Khenpo enumerates eight causes to which rainfalls can be attributed: 1. nāga (klu), 2. yakśa (gnod sbyin), 3. kumbhāṇḍa (grul bum), 4. deity (lha), 5. power of people (mi rnams kyi mthu), 6. offering and giving (mchod sbyin), 7. magical illusion (rdzu ‘phrul), and 8. truth (bden pa).51 Sumpa Khenpo’s discussion of rainmaking is mostly with regard to the first topic—namely nāgas—and he divides the discussion into four subtopics: 1. Guhyasamāja Tantra; 2. Cakrasaṃvara Tantra; 3. ways of depending on other deities; 4. Miktsema Prayer, and Mahāmegha Sūtra (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folio 4b).

5.2.1. Guhyasamāja Tantra

Sumpa Khenpo begins the part with a quotation from the Root Tantra of Guhyasamāja:

namaḥ samantakāyabāktsittabadzrāṇām oṃ hūṃ hūṃ hūṃ phaṭ phaṭ phaṭ ugraśūlapāṇi hūṃ hūṃ hūṃ phaṭ phaṭ phaṭ oṃ dzyotinirnāda hūṃ hūṃ hūṃ phaṭ phaṭ phaṭ oṃ mahābalāya svāhā. As soon as this was said, all of Mahābala’s serpents, terrified and afraid in their hearts, contemplated the Three Vajra Bodies. Accomplish all actions and make rain fall in time of drought simply by means of chanting the mantra.(Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folios 4b–5a)52

Sumpa Khenpo divides the procedure into three parts in a way that he notes is similar to Tsongkhapa’s method: i. Preliminary (sngon ‘gro); ii. Actual (ritual) (dngos gzhi); iii. Closure (mjug).

Preliminary

First, Sumpa Khenpo details the prerequisite conditions for the ritual. The officiant should recite the mantra of wrathful Mahābala (Stobs po che) 400,000 times, or at least 100,000 times. Then follow other conditions for the officiant: they must have specific words in their names, be a holder of vows, abstain from consuming musk, fetid vegetables, tobacco, liquor, etc., and must not be disabled.

Next, the astrological timing for the ritual must be right (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folio 5a).53

Then the officiant must locate a proper location on the shore of a body of water and must properly equip the place: cairns must be built in the four cardinal directions and blue silk cloth with mantras and names of Buddhas and bodhisattvas written on it installed there. The mantras and names provided are from Ārya-Mahāmegha.

Next, Sumpa Khenpo describes the visualization of the vajra protection circle produced from the Wrathful Blue Mahābala and Water God. The officiant must then have an eight-petaled lotus wheel drawn in blue as a circle diagram at the shore with substances from a clay bowl. After that, clay bowls, altars, and a blue canopy, all with blue-petaled lotuses painted on them, must be set up. Then the officiant must prepare blue vessels to be filled with blue nāga-medicine compounded with diverse ingredients including blue flowers. Sumpa Khenpo has it that this last part is based on Vijaydata’s commentary to Guhyasamāja Tantra54 and also that it is the same as what is in Ārya-Mahāmegha and Catuhpitha (Gdan bzhi) (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folios 5b–6a).

Actual (Ritual)

Sumpa Khenpo opens his explanation of the actual ritual by stating that, for the most part, mantra-successors keep this section secret. His explanation of the main activities is as follows: after taking refuge and meditating for water-deities and local deities, the officiant must visualize themself as the Wrathful Blue Mahābala. Sumpa Khenpo provides a very detailed description of the Wrathful Blue Mahābala for this visualization,55 ending it with praise for the deity himself (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folios 6a–6b).

The officiant must then visualize maṇḍalas of the elements, and then Varuṇa56 and the eight nāga kings in each direction to their fore, then dissolve themselves into Varuṇa and the eight nāga kings. Then, clay bowls with open lids and other substances must be arranged and blessed, after which the lids of the bowls must be closed and the bowls placed in the pond. Meditating with love and bodhicitta and trusting that every phenomenon is illusory, the officiant must use mantra recitation to order Varuṇa and the nāgas of the maṇḍala and clay bowls to cause rain to fall. By doing so, snow or rain will fall right away by order of Vajradhāra (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folios 6b–7a).

Closure

After the snow or rain stops, the officiant must arrange nāga-torma and bless them with mantra and mudrā. They must also offer thanks, praise, and dedication prayers with mantra. That is how Tsongkhapa explained the rainmaking ritual based on Mahābala (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folios 7a–7b).57

Addendum to Guhyasamāja Tantra

Sumpa Khenpo adds to this explanation of the ritual further details drawn from commentaries on tantra. The contents of his expansion are as follows: how to produce the wheel weapon diagrams that are meant to fill the clay bowls and how to arrange them; details on nāga wheel diagrams and how they differ depending on the season; details on nine offering pots and their substitutes (nāga-torma or nāga-medicine); an explanation of external and inner offerings for self-generation in front of the altar; details on clay wheel purification; the arrangement of the eight nāga kings by direction and letters on the wheel’s spokes; generation of element maṇḍalas and Varuṇa; the prayers for the clay bowls and maṇḍala; purification of tormas other than the nāga torma; the invitation of recipients for torma offerings, the dedication of divine cakes, and the request that rain fall and that the deities return to their own residences; purification of nāga torma offerings and the contents of the vases; and how to bless offering items with mudrā (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folios 7b–9b).

In closing this addendum to the rite, Sumpa Khenpo explains that these elements accord with the opinion of Buton Rinchen Drup (Bu ston Rin chen grub, 1290–1364), although other paṇḍitas have expressed different opinions in their commentaries on tantras.58

Sumpa Khenpo then adds remarks on a few miscellaneous topics related to rainmaking: on the effectiveness of using the Three Syllables (‘bru gsum, namely oṃ, āh, and hūṃ); on using other syllables for purification; on two different types of dedication, when busy and when not busy; on making daily torma offerings at designated times; on using the soft mantra from commentaries rather than harsh mantra from the root tantra in cases of great drought; on using mudrā when reciting mantra; on continuously repeating five mantras even if rain does not fall; on the dangers of using harsh measures if soft ones are not successful; on the mantra and sūtra recitation for gathering clouds used by inner and outer recluses; on measures to take when clouds fail to gather due to lack of wind; in detail on measures to take to control the winds to gather clouds in reliance on Hayagrīva and Acala; on measures to block strong winds, and its visualization and mudrā (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folios 10a–12b).

Lastly, Sumpa Khenpo again discusses the conclusion of the ritual, repeating his explanation of thanksgiving and dedication with torma offerings. He adds that the officiant must now dissolve Vajradhāra into themself and request that Varuṇa return to his own residence.

5.2.2. Cakrasaṃvara Tantra

Just as he did in the previous section based on Guhyasamāja Tantra, Sumpa Khenpo begins this section by citing the Root Tantra of Cakrasaṃvara: “From ‘Then, basic secret mantra’s …’ up to ‘… to make rain fall and …’”59 In his commentary on the rainmaking ritual here, he uses slightly different terms for its three parts: i. Preparation (sbyor ba); ii. Actual (Ritual) (dngos); iii. After (rjes) (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folio 12b).60

Preparation

The officiant, dwelling in the pride of Heruka, must paint eight-petaled lotuses on clay bowls and locate eight nāga kings at each direction in each color. They must also write mantras on the bowls and arrange torma offerings like before.

Actual (Ritual)

The officiant must then meditate self-generation of Cakrasaṃvara in either an extensive or concise way. Following this, Sumpa Khenpo details the production of nāga-maṇḍala and the placement of clay bowls in the nāga residences. If the officiant recites various mantras while simultaneously offering nāga-torma, rain will fall. If it does not, they must rub medicines on the wheels, burn incense, and recite mantras.

After

This section is the same as given above (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folios 12b–13b).61

5.2.3. Ways to Depend on Other Deities

Sumpa Khenpo explains that, in this case, the officiant must draw the images of Varuṇa and nāgas on the altar and fashion figures of them with soil from old stūpas, mountain tops, or from underwater. After installing these figures, the officiant must begin self-generation, visualizing themselves as nāga kings bearing many symbols who rescue sentient beings, and then they should praise those nāga kings. Next, they must dissolve their visualization into rays of light emanating from mantras, radiating the rays to nāgas and sentient beings to relieve their suffering and to make them happy.

After explaining this visualization, Sumpa Khenpo provides texts of some offering-mantras for use in extensive torma offerings, which conclude with dissolving oneself into the wisdom body. He then explains how to generate and merge Varuṇa and nāga on the altar made of earth. The officiant recites the nāga king’s mantra to the nāga’s heart, and the nāga in turn recites the mantra that will be dissolved into the officiant’s heart. In this way, the officiant can induce nāgas to bring rain. After a successful rainfall, the officiant must perform a thanksgiving service with torma and power substances, such as mustard seed (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folios 13b–14b).62

Sumpa Khenpo next introduces Guhyapati (Vajrapāṇi) as a deity on which a rainmaking ritual can be based, citing relevant passages from Sarvadurgatipariśodhana Tantra (Ngan song sbyong rgyud) (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folio 14b).63 He indicates that there are diverse ways of describing Vajrapāṇi and the nāga kings, but that these differences do not matter if they have their bases in tantras or Indo–Tibetan texts of one kind or another. Sumpa Khenpo details the arrangement of the altar and other preparations for the Vajrapāṇi rainmaking ritual, in particular including the creation of nāga figures with diverse materials and clay bowls filled with nāga-medicine. After that, Sumpa Khenpo provides instruction to officiants on holding vows, prohibition of smoking, and maintaining dietary abstinence from certain foods (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folios 14b–15b).

Then comes the main part of the Vajrapāṇi ritual. It begins with visualization and then proceeds on to purification of offering substances and blessing torma. Next, in order to create an appropriate nāga-maṇḍala, the officiant must understand the status of the water and what kind of nāga resides there. Using mudrā and reciting mantra, the officiant invites the nāgas to provide rain. They must then continue the visualization, purify the offering torma with mudrā, and make offerings.64

It is also possible to make rain fall by visualizing oneself as Vajrapāṇi and purifying demonic beings’ sins by shedding lights to them. After an intermission, the officiant prepares clay bowls filled with dough balls made from nāga-medicine and milk. They then offer the clay bowls in the eight directions and recite nāgas’ names in each direction with offerings of flowers, milk, and torma. Sumpa Khenpo states that the supplication that accompanies the torma offering can be recited in Tibetan. The officiant then offers torma to the Cloud King (Sprin rgyal)65 and brandishes flags while reciting a cloud-controlling mantra, after which assistants recite Mahāmegha Sūtra and perform smoke offerings. If the officiant makes a sincere attempt at the ritual, offering torma and dough balls of nāga-medicine and milk in any body of water in an area, the strength of Buddha’s words and mantra will show itself.

Again, participants in the ritual must observe some dietary and behavioral abstinence for the duration of the ritual. As was the case with the Guhyasamāja-based ritual, during the Vajrapāṇi ritual participants should not use coercive or harmful means to induce rain, even if the rainmaking is not successful. Nor should they brag that that they are able to perform any coercive rainmaking ritual. Sumpa Khenpo offers alternatives to coercive means that are a little softer. He also notes that although mantra recitations are most effective when done in Sanskrit, the ritual will nevertheless be effective if performed with proper substances, sincere invocation of nāgas, and faith in the power of mantras. Distracted mind and impure mantras should be avoided (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folios 15b–19b).66

Sumpa Khenpo then gives a detailed explanation of the ransom (glud) ritual. He discusses the credibility of the ransom ritual at length and chides its critics as frivolous and arrogant scholars. We should not follow those who deny it, he says, but have faith in the ransom dedication, even citing a successful example of one. Sumpa Khenpo claims that this ransom ritual is different from the Yama worship of Bon practitioners. However, the chöd (gcod) practice mentioned in Miktsema Magical Activities and by Sakya Paṇḍita both gave credit to the ransom dedication. Then follows the details of how to purify and bless ransom torma in many different ways (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folios 20a–23b).

Sumpa Khenpo concludes this section of the text with very brief mentions of rainmaking rituals based on Sitatapatra Sūtra (Gdugs dkar mdo) and Avalokiteśvara (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folio 23b).67

5.2.4. Miktsema and Mahāmegha Sūtra

Sumpa Khenpo begins this section by explaining that rainmaking, the first magical activity among the Eleven Miktsema Magical Activities (Dmigs brtse ma’i las tshogs) that were compiled from one hundred activities, is now very well-known and that an extensive manual on the subject is found in the works of the former Changkya (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folio 23b).68

Secondly, he says that there is a rainmaking ritual that conforms to Ārya-Mahāmegha (Sprin chen char ‘beb) and Ārya-mahāmegha-vāyu-maṇḍala (Klu thams cad kyi snying po’i mdo) sūtras and explains its procedure. The officiant must prepare, beginning with their mental attitude, and then must clean their body and prepare a clean cushion with the names of tathāgatas on them. When these names are recited and offerings made, Sumpa Khenpo says, rain will fall. He also talks about drawing nāga kings in each direction and preparing blue-colored equipment. The reading of the sūtra as part of the ritual requires certain conditions of abstinence, such as dietary restrictions and fasting, and also requires a designated number of assistants. The officiant must also use hand-copied sūtras that must be properly decorated. During the recitation of sūtras, also, the officiant must continue to meditate relevant deities. Faith in effectiveness of these sūtras is also essential for successful rainmaking (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folios 23b–25a).

Sumpa Khenpo then considers the rainmaking stones used by Muslims and Oirats, clearly claiming that their method is different from those used by Nyingma, Bon, or non-Buddhist practitioners, which depend on ill substances or false claims.69 The rain stone that Muslims and Oirats use is basically a bezoar, but stones from musk deer, eagle, peacock, owl, and human skull should not be used. Nor should one use dry desert stones or ghost stones (‘byung po’i rdo) because they may cause harm to nāgas in water. Appropriate stones for use in rainmaking are: stones hit by lightning, abdominal pills from snakes, mouth stones from deer or donkey, brain stones from horse or sheep, stones from a wild ass, spirit stones from fog-shrouded mountain tops, or crystals that have water inside. These stones dispel nāga pain and delight them, so they will bring rain.

Sumpa Khenpo then provides the following detailed explanation of the procedures for using rain stones as follows: one must find a rain stone appropriate for the ritual; bind it with tail hairs from a blue horse and blow horse’s breath on it; prepare a crystal vessel and fill it with water from nine ponds and put the stone in it; cover the vessel’s mouth with blue flowers and leaves from nāga-tree and put the vessel near the water; put blue flowers and tree branches around it such that it cannot be seen from the sky; offer nāga-torma and white torma and request that rain be made to fall; recite mantras from Mahāmegha Sūtra and by the power of mantra rain will fall, as it would successfully fall when done with mantra substances mentioned above (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folios 25a–25b).70

5.2.5. Addendum to Manual for Rainmaking

At the conclusion of this section Sumpa Khenpo explains why he provides so many different methods for rainmaking: one should reply on the deity with whom one has formed his/her intimate relation. He takes the opportunity to once more warn that fierce and coercive measures should only be used as a last resort. The degree of softness or ferocity in the ritual can be decided depending on topographical differences between ritual sites, such as whether the site is a mountainous area, a field on a plain, a high plateau, or a low-lying area. Sumpa Khenpo also warns that rituals should not be performed to obtain wealth or reputation. Nor should officiants, out of desperation in dire situations, resort to impure traditions like putting yak horns filled with ill substances into bodies of water, etc., which are practiced by Nyingma or Bon ritualists. The wise are successful in rainmaking, he says, because they discard bad traditions and employ measures prescribed by the True Doctrine. Sumpa Khenpo reiterates that one must be assisted by people bearing certain requisite elements when dealing with nāgas. He discusses how to make nāga-torma, taboos—people who must not be allowed to approach the ritual site, such as menstruating women, and the harm of consuming tobacco. Sumpa Khenpo then explains how to create the circle diagrams for inducing the right clouds and winds and how to use them. Lastly, he advises that examining the color of clouds for rainmaking is a skill that can also be used to predict hail (Sum pa mkhan po [1758] 1975–1979a, folios 25b–28b).

Thus, concludes the part of the text dedicated to rainmaking rituals, after which Sumpa Khenpo will move on to other disaster-averting rituals.71

6. Thoughts on Sumpa Khenpo’s Rainmaking Ritual Manual

First, Sumpa Khenpo’s ritual manual on rainmaking chooses a diversity of Buddhist deities and uses them in a variety of different ways. After starting out with Mahābala, Sumpa Khenpo also suggests using Heruka, Varuṇa, Vajrapāṇi, Sitatapatra and Avalokiteśvara for rainmaking activities. Not only does he detail deity-based approaches to rainmaking, he proposes nondeity methods as well, such as using rain stones or sūtras. The diversity in his instruction indicates an assumed prevalence of a breadth of knowledge about tantric deities among his intended audience. Sumpa Khenpo advises that all of the methods described in his manual can be used for the very pragmatic purpose of altering the weather. The breadth of Sumpa Khenpo’s treatment of these weather rituals seems to be unprecedented, which may explain why he felt that former paṇḍitas had ignored rainmaking as one of their capacities (yon tan).

Second, Sumpa Khenpo’s manual is obviously deeply rooted in Buddhist studies, especially in his canonical knowledge and mastery of tantras. Quotations of canonical works drawn from a broad section of Buddhist literature give weight and authority to his explanations for each method of rainmaking. Throughout the sections on rainmaking, Sumpa Khenpo’s repetitive emphasis on shunning coercive ways and performing the rituals with care and love affirms his role as an exemplary Buddhist master and an agent within an established Buddhist institutional system.

Third, in order to verify and uphold his particular institutional affiliation, Sumpa Khenpo regularly reveals his sectarian position. We can read his attacks on Nyingma and Bon practices of rainmaking in this context.72 However, Sumpa Khenpo is not exclusively a Buddhist sectarian. He is tolerant of some Inner Asian traditional elements, as in the case of the rain stones used by Oirats and Muslims. This kind of flexibility might have earned him a friendlier reception from Inner Asian subjects of the cosmopolitan Qing empire.73

Fourth, in spite of the breadth of Sumpa Khenpo’s treatment of rainmaking rituals, the manual does demonstrate some incompleteness and the author meanders within topics. His arrangement is indeed not that systematic and his discussions are often repetitive. However, this would allow subsequent Tibetan Buddhist masters to improve on this treatment and innovate further measures related to the topics discussed herein. In other words, Sumpa Khenpo was not the final integrator of weather rituals, but primed the water pump for later masters to draw a fuller measure of explanation from the well of institutional and traditional knowledge.

Finally, weather rituals were, of course, neither the only, nor most frequent, of Sumpa Khenpo’s evangelical activities. There are more instances of diverse tantric empowerments and other activities—such as teachings, medical aids, and funeral services—among his list of activities than there are performances of rainmaking rituals. However, performing weather rituals must have been a more people-friendly activity than other religious activities.74

7. Concluding Remarks

Ritual can be employed on many different religious levels in Tibetan Buddhism, ranging from purely soteriological in nature to essentially pragmatic ends. Weather rituals were certainly more immediately relevant to all walks of life than were other types of enlightenment-oriented rituals, whose meaning and availability were limited primarily to elite religious adepts. Weather rituals have undergone modification and expansion throughout their long textual history, stretching from examples found at Dunhuang down to the present. However, the 18th century witnessed a quantitative and qualitative turning point in their development. These rituals were not only preserved on paper but were actively used by Tibetan Buddhist clerics as part of their evangelical activity throughout Mongolia, a fact we find recorded in Sumpa Khenpo’s biography in particular and in records of other Tibetan Buddhist clerics.

The development of popular weather rituals dovetails fittingly with the successful dissemination of Tibetan Buddhism in areas where Tibetan Buddhist clerics were active. Although weather rituals were not the most important factor nor do they explain everything about the historical success of Tibetan Buddhism in the cosmopolitan Qing empire, we can see that they played a role in the process. By providing a detailed summary of a key text on weather rituals from the period and placing it in its proper religious and historical contexts, this article opens a new avenue for understanding the religious activity of manipulating the weather with rituals—an activity that human societies seem to have engaged in always and everywhere.

Funding

The research of this article was funded by Pony Chung Foundation and the APC was funded by the Society of Fellows in the Liberal Arts of Southern University of Science and Technology, China.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to extend his warm gratitude to Andy Francis for his excellent copyediting and kind suggestions. The author also thanks Leonard van der Kuijp for his continuous encouragement for the research project.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Bao, Wenhan, and Qi Chaoketu, eds. 1998. Menggu Hui bu Wanggong Biaozhuan, diyiji 蒙古回部王公表傳, 第一辑. Hohhot: Neimenggu daxue chubanshe. First published 1795. [Google Scholar]

- Bendall, Cecil. 1880. The Megha-sūtra. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 12: 286–311. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Patricia. 2001. Miracles in Nanjing: An Imperial Record of the Fifth Karmapa’s Visit to the Chinese Capital. In Cultural Intersections in Later Chinese Buddhism. Edited by Marsha Weidner. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 145–69. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Patricia. 2003. Empire of Emptiness: Buddhist Art and Political Authority in Qing China. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berounsky, Daniel. 2015. Tibetan ‘Magical Rituals’ (las sna tshogs) from the Power of Tsongkhapa. Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines 31: 95–111. [Google Scholar]

- Bialek, Joanna. 2019. When Mithra Came as Rain on the Tibetan Plateau: A New Interpretation of an Old Tibetan Topos. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 169: 141–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birtalan, Ágnes. 2001. The Tibetan Weather-magic Ritual of a Mongolian Shaman. Shaman 9: 119–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bkra shis bzang po, ed. 2014. Chu ‘brel bod kyi yig rnying phyogs bsgrigs. 5 vols. Mgo log: Gnyan po g.yu rtse’i skye khams khor yug srung skyob tshogs pa. [Google Scholar]

- Brag dgon zhabs drung, Dkon mchog bstan pa rab rgyas. 1982. Mdo smad chos ‘byung. Lanzhou: Kan su’u mi rigs dpe skrun khang. First published 1865. [Google Scholar]

- Bstan pa bstan ‘dzin. 2003. Chos sde chen po dpal ldan ‘bras spungs bkra shis sgo mang grwa tshang gi chos ‘byung dung g.yas su ‘khyil ba’i sgra dbyangs. 2 vols. Mundgod: Dpal ldan ‘bras spungs bkra shis sgo mang dpe mdzod khang. [Google Scholar]

- Bu ston, Rin chen grub. 1965–1971. Collected Works. New Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture. [Google Scholar]

- Cabezón, José Ignacio. 2010. Introduction. In Tibetan Ritual. Edited by José Ignacio Cabezón. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Charleux, Isabelle. 2015. Nomads on Pilgrimage: Mongols on Wutaishan (China), 1800–1940. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas, Bryan. 2010. The ‘Calf ‘s Nipple’ (Be’u bum) of Ju Mipam (‘Ju Mi pham): A Handbook of Tibetan Ritual Magic. In Tibetan Ritual. Edited by José Ignacio Cabezón. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 165–86. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, Jacob, and Sam van Schaik. 2006. Tibetan Tantric Manuscripts from Dunhuang: A Descriptive Catalogue of the Stein Collection at the British Library. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, Ronald. 2017. Studies in Dhāraṇī Literature IV: A Nāga Altar in 5th Century India. In Consecration Rituals in South Asia. Edited by István Keul. Leiden: Brill, pp. 123–70. [Google Scholar]

- De’u dmar, Bstan ‘dzin phun tshog. 2005. Shel gong shel phreng. Beijing: Mi rigs dpe skrun khang. First published 18th Century. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, Siglinde. 2000. Mātr̥ceṭas Kaliyugaparikathā. In Vividharatnakaraṇḍaka: Festgabe für Adelheid Mette. Edited by Adelheid Mette, Christine Chojnacki and Jens-Uwe Hartmann. Swisttal-Odendorf: Indica et Tibetica Verlag, pp. 173–86. [Google Scholar]

- Doniger, Wendy, ed. 1999. Merriam-Webster’s Encyclopedia of World Religions. Springfield: Merriam-Webster. [Google Scholar]

- Eckel, Malcolm. 2008. Bhavaviveka and His Buddhist Opponents: Chapters 4 and 5 of the Verses on the Heart of the Middle Way (Madhyamakahrdayakarikah) with the Commentary Entitled The Flame of Reason (Tarkajvala). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elverskog, Johan. 2011. Wutai Shan, Qing Cosmopolitanism, and the Mongols. Journal of the International Association of Tibetan Studies 6: 243–74. [Google Scholar]

- Elverskog, Johan. 2013. China and the New Cosmopolitanism. Sino-Platonic Papers 223: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar, David. 1960. The Ch’ing Administration of Mongolia. Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar, David. 1978. Emperor as Bodhisattva in the Governance of the Ch’ing Empire. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 38: 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forêt, Philippe. 2000. Mapping Chengde: The Qing Landscape Enterprise. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fremantle, Francesca. 1971. A Critical Study of the Guhyasamāja Tantra. Ph.D. thesis, School of Oriental and African Studies, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, Melvyn, ed. 2001. The New Tibetan-English Dictionary of Modern Tibetan. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, David. 2007. The Cakrasamvara Tantra: The Discourse of Śrī Heruka (Śrīherukābhidhāna). New York: American Institute of Buddhist Studies at Columbia University. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, Kevin. 2013. Yonghegong: Imperial Universalism and the Art and Architecture of Beijing’s ‘Lama Temple’. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Grupper, Samuel. 1984. Manchu Patronage and Tibetan Buddhism during the First Half of the Ch’ing Dynasty. The Journal of the Tibet Society 4: 47–75. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Rulin. 1982. Qinghai Youningsi ji qi mingseng (Zhangjia, Tuguan, Songba) 青海佑宁寺及其名僧. In Qiongluji. Edited by Bohan Liu. Shanghai: Shanghai Renmin Chubanshe, pp. 390–415. First published 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Hevia, James. 1993. Lamas, Emperors, and Rituals: Political Implications in Qing Imperial Ceremonies. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 16: 243–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hidas, Gergely. 2019. A Buddhist Ritual Manual on Agriculture: Vajratuṇḍasamayakalparāja—Critical Edition and Translation. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Minghui, and Johan Elverskog, eds. 2016. Cosmopolitanism in China, 1600–1950. Amherst: Cambria Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Toni, and Poul Pedersen. 1997. Meteorological Knowledge and Environmental Ideas in Traditional and Modern Societies: The Case of Tibet. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 3: 577–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illich, Marina. 2006. Selections from the Life of a Tibetan Buddhist Polymath: Chankya Rolpai Dorje (Lcang skya rol pa’i rdo rje), 1717–1786. Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ishihama, Yumiko. 2001. Chibetto Bukkyō sekai no rekishiteki kenkyū チベット仏教世界の歴史的研究. Shohan. Tōkyō: Tōhō Shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Ishihama, Yumiko. 2011. Shinchō to Chibetto Bukkyo: Bosatsu to Natta Kenryutei 清朝とチベット仏教: 菩薩となった乾隆帝. Tōkyō: Waseda Daigaku Shuppanbu. [Google Scholar]

- ‘Jam dbyangs bde ba’i rdo rje, and Chos mdzad Ngag dbang bzod pa rgya mtsho, eds. 2013. Dmigs brtse ma’i chos skor dngos grub kun ‘byung yid bzhin nor gyi bang mdzod. 3 vols. Beijing: Mi rigs dpe skrun khang. [Google Scholar]

- Kapstein, Matthew. 1989. The Purificatory Gem and Its Cleansing: A Late Tibetan polemical Discussion of Apocryphal Texts. History of Religions 28: 217–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Hanung. 2013. Manchu Folklore: Tales Told by A Bewitched Being. Available online: https://www.manchustudiesgroup.org/2013/05/06/manchu-folklore-tales-told-by-a-bewitched-being/ (accessed on 21 October 2020).

- Kim, Hanung. 2015. Another Tibet at the Heart of Qing China: Location of Tibetan Buddhism in the Mentality of the Qing Chinese Mind at Jehol. In Greater Tibet: An Examination of Borders, Ethnic Boundaries, and Cultural Areas. Edited by P. Christiaan Klieger. Lanham: Lexington Books, pp. 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hanung. 2017. Introduction to the New Publication of Sum pa Ye shes dpal ‘byor’s Collected Works. Zangxue xuekan 藏学学刊 17: 275–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hanung. 2018. Renaissance Man from Amdo: The Life and Scholarship of the Eighteenth-Century Amdo Scholar Sum pa Mkhan po Ye shes dpal ‘byor (1704–1788). Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hanung. 2019. Preliminary Notes on Lamo Dechen Monastery and Its Two Main Incarnation Lineages. Archiv Orientální suppl 11: 77–97. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hanung. 2020. Reincarnation at Work: A Case Study of the Incarnation Lineage of Sum pa mkhan po. Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines 55: 245–68. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Anne. 2018. Divining Hail: Deities, Energies, and Tantra on the Tibetan Plateau. In Coping with the Future: Theories and Practices of Divination in East Asia. Edited by Michael Lackner. Leiden: Brill, pp. 233–51. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Anne, and Sangpo Rinpoche Khetsun. 1997. Hail Protection. In Religions of Tibet in Practice. Edited by Donald S. Lopez. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 538–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kleingeld, Pauline, and Eric Brown. 2019. Cosmopolitanism. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/cosmopolitanism/#Cosm19th20thCent (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Köhle, Natalie. 2008. Why Did the Kangxi Emperor Go to Wutai Shan? Patronage, Pilgrimage, and the Place of Tibetan Buddhism at the Early Qing Court. Late Imperial China 29: 73–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krung go’i bod kyi shes rig zhib ‘jug lte gnas kyi bka’ bstan dpe sdur khang. 2006–2009. Bka’ ‘gyur dpe bsdur ma. 109 vols. Beijing: Krung go’i bod rig pa’i dpe skrun khang. [Google Scholar]

- Krung go’i bod kyi shes rig zhib ‘jug lte gnas kyi bka’ bstan dpe sdur khang. 1994–2008. Bstan ‘gyur dpe bsdur ma. 120 vols. Beijing: Krung go’i bod rig pa’i dpe skrun khang. [Google Scholar]

- Lcang skya II, Ngag dbang blo bzang chos ldan. 19th Century. Dmigs brtse ma la brten pa’i char ‘bebs kyi zur rgyan. The vol. 7 Gsung ‘bum. Beijing: [s.n.].

- Lcang skya III, Rol pa’i rdo rje. 2015. Lcang Skya Rol pa’i Rdo rje’i Gsung ‘bum. 9 vols. Lhasa: Bod ljongs mi dmangs dpe skrun khang. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Shen-yu. 2005. Tibetan Magic for Daily Life: Mi pham’s Texts on gTo-rituals. Cahiers d’Extrême-Asie 15: 107–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, Rory. 2018. Liberating Last Rites: Ritual Rescue of the Dead in Tibetan Buddhist Discourse. Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Sheldon. 2017. Cosmopolitanism and Alternative Modernity in Twentieth-century China. Telos 180: 105–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millward, James, Philippe Forêt, Mark Elliott, and Ruth W. Dunnell. 2004. New Qing Imperial History: The Making of Inner Asian Empire at Qing Chengde. London: RoutledgeCurzon. [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki, Junko. 1991. Kiinshi sanshū ‘Kintei gaihan mōko kaibu ōkō hoyden’ kō 祁韻士纂修『欽定外藩蒙古回部王公表傳』考. Tōhōgaku 81: 102–15. [Google Scholar]

- Molnár, Ádám. 1994. Weather-Magic in Inner Asia. Bloomington: Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Naquin, Susan. 2008. Peking: Temples and City Life, 1400–1900. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- de Nebesky-Wojkowitz, René. 1956. Oracles and Demons of Tibet: The Cult and Iconography of the Tibetan Protective Deities. The Hague: Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Nietupski, Paul. 2010. Labrang Monastery: A Tibetan Buddhist Community on the Inner Asian Borderlands, 1709–1958. Lanham: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, Chia. 1993. The Lifanyuan and the Inner Asia Rituals in the Early Qing (1644–1795). Late Imperial China 14: 60–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oidtmann, Max. 2018. Forging the Golden Urn: The Qing Empire and the Politics of Reincarnation in Tibet. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pan chen VI, Blo bzang dpal ldan ye shes. 1975–1978. Collected Works. New Delhi: Mongolian Lama Gurudeva. [Google Scholar]

- Polo, Marco. 1903. The Book of Ser Marco Polo, the Venetian, Concerning the Kingdoms and Marvels of the East, 1, 2, Index, 3rd ed. Translated by Henry Yule. London: John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Rdo rje don grub. 2012. Hail Prevention Rituals and Ritual Practitioners in Northeast Amdo. Asian Highlands Perspectives 21: 71–111. [Google Scholar]

- Rockhill, William Woodville. 1910. The Dalai Lamas of Lhasa and Their Relations with the Manchu Emperors of China, 1644–1908. T’oung Pao 11: 1–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruegg, David Seyfort. 1991. Mchod yon, yon chod and mchod gnas/yon gnas: On the Historiography and Semantics of a Tibetan Religio-Social and Religio-Political Concept. In Tibetan History and Language: Studies Dedicated to Géza Uray on His Seventieth Birthday. Edited by Ernst Steinkellner. Wien: Arbeitskreis fur Tibetische und Buddhistische Studien, Universitat Wien, pp. 441–54. [Google Scholar]

- Schmithausen, Lambert. 1997. Maitrī and Magic: Aspects of the Buddhist Attitude toward the Dangerous in Nature. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Schwieger, Peter. 2014. The Dalai Lama and the Emperor of China: A Political History of the Tibetan Institution of Reincarnation. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sihlé, Nicolas. 2010. Written Texts at the Juncture of the Local and the Global: Some Anthropological Considerations on a Local Corpus of Tantric Ritual Manuals (Lower Mustang, Nepal). In Tibetan Ritual. Edited by José Ignacio Cabezón. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sperling, Elliot. 2001. Notes on the Early History of Gro-tshang Rdo-rje-’chang and its Relations with the Ming Court. Lungta 14: 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Rolf Alfred. 2010. Rolf Stein’s Tibetica Antiqua: With Additional Materials. Translated by Arthur P McKeown. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, Brenton. 2018. The Manner in which I went to Worship Mañjuśrī’s Realm, The Five-Peaked Mountain (Wutai), by Sumba Kanbo (1704–1788). Inner Asia 20: 64–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sum pa mkhan po. 1975–1979a. Kha char ‘beb srung sogs kyi gdams pa gnam sa’i mdzes rgyan. In Collected Works of Sum-Pa-Mkhan-Po. New Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture, First compiled 1758. [Google Scholar]

- Sum pa mkhan po. 1975–1979b. Sum pa mkhan po dz+nyA na shrI b+hu ti bas gzhung chen po du ma las btus pa rnam gyi dkar chag dwangs mtsho’i gzugs brnyan. In Collected Works of Sum-Pa-Mkhan-Po. New Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture, First compiled 1777. [Google Scholar]

- Sum pa mkhan po. 1975–1979c. Paṇḍita Sum pa ye shes dpal ‘byor mchog gi spyod tshul brjod pa sgra ‘dzin bcud len. In Collected Works of Sum-Pa-Mkhan-Po. New Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture, First compiled 1788. [Google Scholar]

- Thu’u bkwan III, Blo bzang chos kyi nyi ma. 1989. Lcang skya Rol pa’i rdo rje’i rnam thar. Lanzhou: Kan su’u mi rigs dpe skrun khang, First compiled 1794. [Google Scholar]

- Tuttle, Gray. 2006. A Tibetan Buddhist Mission to the East: The Fifth Dalai Lama’s Journey to Beijing, 1652–1653. In Power, Politics, and the Reinvention of Tradition: Tibet in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Edited by Bryan Cuevas and Kurtis Schaeffer. Leiden: Brill, pp. 65–87. [Google Scholar]

- van Schaik, Sam. 2020. Buddhist Magic: Divination, Healing, and Enchantment through the Ages. Boulder: Shambhala Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Waddell, Laurence Austine. 1895. The Buddhism of Tibet: Or Lamaism, with its Mystic Cults, Symbolism and Mythology, and in Its Relation to Indian Buddhism. London: W.H. Allen & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Xiangyun. 1995. Tibetan Buddhism at the Court of Qing: The Life and Work of Cang-Skya Rol- Pa’i-Rdo-Rje, 1717–1786. Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Xiangyun. 2000. The Qing Court’s Tibet Connection: Lcang skya Rol pa’i rdo rje and the Qianlong Emperor. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 60: 125–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, George. 2003. Handbook of Hindu Mythology. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. [Google Scholar]

- Woolf, Marsha, and Karen Blanc. 1994. The Rainmaker: The Life Story of Venerable Ngagpa Yeshe Dorje Rinpoche. Boston: Sigo Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | snga mo char ‘bebs dgos pa’i skabs ‘ga’ zhig tu bde mchog gi rgyud nas gsungs pa’i nam mkha’ lding gi bris sku la brten pa’i gdams pa des char bzang po yang yang phab pa yin kyang cung zad rtsub pa zhig ‘dug/ da res klu chog gsar ba de brtsams pa la rten ‘brel mang po rang ‘grig tu byung bas ‘dis slad gzhan la phan thogs pa zhig yong ba ‘dra/ deng sang mi ‘ga’ zhig gis char rdo bzhag pa’i ‘bebs thabs byed kyin ‘dug kyang/ de kla klo’i chos lugs yin pas dkon mchog la skyabs ‘gro byed mkhan tshos lag len byed mi rung/ rang re dkon mchog la blo bkal nas mdo rgyud man ngag las byung ba’i gdams pa gang shes de lag tu blangs na char babs yong/ gal te ma babs na sems can spyi mthun gyi las yin pas bya thabs ci yod/ sangs rgyas zhal bzhugs dus su yang lo mang por char ma babs pa’i gtam brgyud yod pa de yin/ char phabs pa’i ming tsam gyi ched du kla klo’i lag len yan chad byed pa dkon mchog dang las ‘bras la yid ches med pa’i rtags yin/ |

| 2 | As an incarnate lama from the Sino–Tibetan border area, Changkya Rölpé Dorjé was a chief consultant and teacher of Tibetan Buddhism for Qianlong emperor (1711–1799) of Qing dynasty. For full-scale studies on Changkya Rölpé Dorjé, see (Wang 1995; Wang 2000; Illich 2006). For Changkya in a context of being a member of clerics at the Sino–Tibetan border, see (Han [1944] 1982). |

| 3 | Great Ocean of Happiness and Benefit (Phan bde’i rgya mtsho chen po) is found in Changkya Rölpé Dorjé’s Collected Works (Lcang skya III 2015, vol. 6, pp. 183–201). Its colophon provides the same information on its composition date and site (i.e., 1766 CE and Doloon Nuur) as mentioned in his biography. |

| 4 | Doloon Nuur (Ch. Duolun nao’er 多伦诺尔) was a religious center for Mongolian Buddhists during Qing dynasty and located in present-day Duolun 多伦 County of Xiningol League, Inner Mongolia. |

| 5 | An earlier version of a similar view was suggested by Ishihama Yumiko. According to her, Tibetans, Mongols, and Manchu people in Qing empire shared a religious and linguistic commonality based on Tibetan Buddhism, which Han Chinese and other ethnic groups in the empire were not able to appreciate. Ishihama explains this commonality with the communal concept of “Tibetan Buddhist World,” instead of using the term “cosmopolitanism.” For this, see (Ishihama 2001; Ishihama 2011). |

| 6 | This inclination has existed from the very beginning of relevant scholarship, such as (Rockhill 1910). More examples are (Farquhar 1978; Grupper 1984; Hevia 1993; Ning 1993; Berger 2003). |

| 7 | Of examples of recent scholarship, for Beijing, (Naquin 2008; Greenwood 2013); For Mount Wutai, (Köhle 2008; Charleux 2015; Sullivan 2018); For Jehol, (Forêt 2000; Millward et al. 2004). Research on Doloon Nuur remains as a desideratum. |

| 8 | For a good example of Han Chinese understanding of Tibetan Buddhism at Jehol, see (Kim 2015). |

| 9 | For a historiographical and semantic discussion of the priest-patron relationship, see (Ruegg 1991). |

| 10 | For an English translation of the episode, see (Sperling 2001, pp. 79–80). |

| 11 | Another case of Tibetan cleric’s performance of miracles (but not weather-related) and its significance for cleric’s relationship with a Ming emperor, see (Berger 2001). |

| 12 | Miktsema (Dmigs brtse ma) was originally a short five-line praising prayer to Tsongkhapa, but diverse types of magical activities (las tshogs) had been devised surrounding the Miktsema Prayer among the Gelug school clerics of later generations. For a study on a history and meanings of this development, see (Berounsky 2015). For the Lamo Sertri incarnation lineage, see (Kim 2019, pp. 89–94). |

| 13 | Gungthang is the second-most prominent incarnation lineage at Labrang (Bla brang) monastery in northeast Tibet (Nietupski 2010, p. 35). |

| 14 | For the Fifth Dalai Lama’s journey, see (Tuttle 2006). For the Sixth Panchen Lama’s journey, see (Kim 2015). |

| 15 | For the scope of his scholarship, see (Kim 2017; Kim 2018). |

| 16 | Menggu hui fu wanggong biaozhuan (Bao et al. [1795] 1998) is a semi-official Qing period source that includes biographical genealogies of Tibetan and Mongolian nobles. For its authorship, outline of contents, and process of completion, see (Miyawaki 1991). |

| 17 | For the process of formation of this infrastructure and its meanings, see (Farquhar 1960). For Sumpa Khenpo’s activities throughout Mongolia, see (Kim 2018, pp. 83–114). |

| 18 | gzhan rgya bod hor gyi mi ser skya nang pa phyi pa kla klo’i rigs tshun chad char ‘beb kyi gzhung dang yig rnying dang shog ‘phyar yan chad yod pa kun gyis kyang char ‘beb la ‘bad na yang sems can spyi mthun las kyis mnar ba’i dus la babs tshe de sla ba min/ |