Abstract

The International Maritime Organization (IMO)’s Maritime Safety Committee (MSC), at its 101st session (5 to 14 June 2019), adopted Resolution MSC.467(101) on the guidance on the definition and harmonization of the format and structure of maritime services in the context of e-Navigation and agreed to consolidate the descriptions of maritime services and to consider them together with all involved international organizations and interested member states, in order to harmonize the provision and exchange of maritime information and data. In doing so, the MSC also approved the initial descriptions of maritime services in the context of e-Navigation (IMO MSC.1/Circ.1610), which had been prepared by the Sub-Committee on Navigation, Communications and Search and Rescue, at its sixth session (16 to 25 January 2019). The information contained in this paper constitutes the descriptions of two selected examples of maritime services, an initial contribution for the harmonization of the formats and structures of pilotage and tug services. The initial description of each of maritime services is expected to be next periodically updated, taking into account developments and related work on international harmonization.

Keywords:

marine navigation; safety at sea; maritime services; e-Navigation; IMO; MSC; NCSR; pilotage service; tug service 1. Background

The present situation in international shipping is characterized by fast technological development, affecting basic concepts of ship operation and even changing traditional paradigms of ship control. The e-Navigation concept developed by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and the International Association of Marine Aids to Navigation and Lighthouse Authorities (IALA) focuses on better and more comprehensive support of human operators. However, modern information and communication technologies (ICT) not only are the core to the implementation of the e-Navigation strategy, but provide good foundation for automation of systems. The progressing digitalization further presses ahead application of integrated and automated systems to steer even large sea-going ships. The manifold abilities of these technologies and companies looking for more cost-effective solutions present autonomous navigation and unmanned shipping as soon to come. Taking this for granted, it will not happen that all ships will be unmanned and autonomous immediately. It is assumed that there will be a transition period, not necessarily short, in which unmanned vessels will operate together with either unmanned autonomous or unmanned remote-controlled vessels. Mixed traffic scenarios appear to be particularly difficult in terms of ship traffic safety and efficiency [1,2].

2. Introduction

The majority of accidents in the maritime domain are caused by human errors. One of the measures to reduce human-related marine accidents was proposed to implement the e-Navigation concept according to the IMO strategy implementation plan (SIP) [3,4,5]. e-Navigation is defined as the "harmonized collection, integration, exchange, presentation and analysis of marine information on board and ashore by electronic means to enhance berth to berth navigation and related services for safety and security at sea and protection of the marine environment”. To achieve this, the introduction of electronic means, including state-of-the-art ICT, is the key to support ship operators on board as well as ashore. Considering the fact that around 50% of accidents occurring at sea are attributed to navigational challenges, a systematic maritime traffic management seems to be necessary. On the other hand, modern ship operations rely on a small number of crew, whose responsibilities for safe and efficient navigation are increasingly high. Without operational support from the shore, using a reliable technology-based system, it would be challenging to reduce marine accidents. e-Navigation provides a great potential to help mitigate incidents such as collisions [6], grounding problems, oil spills, and piracy. It also allows, for certain, utilizing both new and existing technologies, which are acceptable within operating standards.

The Maritime Safety Committee (MSC), at its 101st session (5 to 14 June 2019), approved the guidance on the definition and harmonization of the formats and structures of maritime services (MSs) in the context of e-Navigation [7] and agreed to consolidate the descriptions of MSs and to consider them together with all involved international organizations and interested member states, in order to harmonize the provision and exchange of maritime information and data. In doing so, the MSC also approved the initial descriptions of MSs in the context of e-Navigation, which had been prepared by the Sub-Committee on Navigation, Communications and Search and Rescue, at its sixth session (16 to 25 January 2019) [8]. The author was a member of the IMO expert group that developed documents regarding the guidance on the definition and harmonization of the formats and structures of MSs in the context of e-Navigation (IMO MSC.467(101) [7]). He was also involved in the IMO MSC.1/Circ.1610 [8] regarding the initial descriptions of MSs in the context of e-Navigation.

The present times have witnessed fast technology development/implementation in the shipping industry. Concepts like e-Navigation are focused on better and more comprehensive support of human operators. Automation, modernizing information, and communication systems are the future in ship operation. Several companies are already talking about unmanned and autonomous ships. These technologies developed in shipping industry contribute to safer, more efficient and sustainable operations at sea, both in containers and human transportation.

Considering that most maritime accidents are due to human errors, one of the actions is to implement e-Navigation to reduce human-based sea accidents. e-Navigation intends to enhance navigation and related services for safety and security at sea and protection of the marine environment. The development of new technologies and their implementation for e-Navigation can implement systematic maritime traffic management and therefore reduce marine accidents.

In this paper, the author studied the operational use of the proposed e-Navigation concept in terms of its requirements and implementation plans as well as potential limitations and benefits around the concept in selected sectors. The information contained in this paper constitutes the initial descriptions of two chosen examples of MSs, an initial contribution for the harmonization of the formats and structures of pilotage and tug services. The initial description of each of MSs is expected to be next periodically updated, taking into account developments and related work on international harmonization.

The majority of the paper is intentionally directly prescribed from the IMO MSC 1/Circ. 1610 [8]. Although this document is referenced several times in the text, which parts of the text are actually direct copies is not clear. The author decided that this must be clarified. Therefore, it was done graphically by using italics in the text. It should be clear that the author took part in writing the initial IMO document and the IMO documents that Circ. 1610 are based on. The development of a maritime service portfolio (MSP) is necessary for the success of e-Navigation. However, one may ask why the author thought that it was necessary to write a paper supporting something that had already been published by the IMO. The main reasons are political, which make such academic support useful and of course have to be confirmed.

3. MSPs

An MSP in the context of e-Navigation can be defined as a set of operational MSs and associated technical services provided in a unified, digital format. Hence, an MSP may also be construed as a set of “products” provided by a stakeholder in a given sea area, waterway, or port as appropriate. Such marine information has been termed “maritime services”, and this guidance envisages harmonizing the structures and formats of digitally transmitted data and information and to display them in a harmonized way on a ship’s bridge or shore-based facilities broadcasting and receiving marine information.

3.1. MSP Definition

Before the work on the development on the definition and harmonization of the formats and structures of MSPs commenced, the IMO Secretariat considered that a clear understanding of MSPs is indispensable. A definition of MSP can be found in [9,10], that is, an MSP defines and describes a set of operational and technical services and levels of services provided by a stakeholder in a given sea area, waterway, or port as appropriate.

The SIP [7] identified 16 MSPs, including the type of service provided by each MSP, as well as the associated responsible service provider. It is evident that the services (MSPs) vary significantly, ranging from, for example, vessel traffic service (VTS) information to a ship, medical information and instructions provided by doctors to the ship’s crew responsible for medical care to ice navigation, route information, search and rescue coordinates and many more. The sets of data, instructions, and information are very different in nature and could take numerical values, geographical coordinates, medical terminology, courses to steer, waypoint coordinates, communication channels, and many more.

As outlined in later IMO documents regarding the e-Navigation output on harmonized MSPs, MSPs are considered to form a framework for the electronic provision of information related to MSs in a harmonized way between the shore and ships. It is therefore necessary to harmonize the format, structure, and communication channels used to exchange [11,12]. It was also argued that a lack of coordination in the provision of information related to MSs among organizations responsible for the provision of MSPs may lead to duplication of efforts, development of regional solutions, use of different communication systems, and the provision of superfluous or noninteroperable information.

It was further acknowledged that the content of MSPs will be developed by different international organizations, and thus coordination among these organizations is a priority to ensure harmonization of scope, format, structure, display on board, and communication systems used to transmit information electronically. While the work on contents of MSPs is currently undertaken by the IALA, the IMO Secretariat considers that the HGDM (IMO/IHO Harmonization Group on Data Modelling) should be tasked to work on the harmonization as outlined above. This interpretation concurs that a “general guidance” should be developed but should not define the detailed content of a particular MSP or aim at harmonizing the service itself. This is the responsibility of relevant data and service providers [13].

Reference [14] reports on the outcome of an informal meeting of member states and international organizations acting as domain-coordinating bodies for the further development of descriptions of MSs in the context of e-Navigation, held at IALA Headquarters on 9 October 2019 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Maritime service portfolios with responsible service providers [9,15].

3.2. Responsible Service Providers

In each country, there are authorities responsible for providing information services (INSs). Table 1 below offers examples of authorities responsible in each case, which can be different between countries. Responsible authorities may require service providers to deliver operational services.

The following six sea areas have been preliminarily identified for the delivery of MSPs:

- port areas and approaches;

- coastal waters and confined or restricted areas;

- open sea and open areas;

- areas with offshore and/or infrastructure developments;

- polar areas;

- other remote areas.

4. MS 1—VTS INS

The submitting organization is the IALA; the coordinating bodies are the IMO and IALA [8].

4.1. Description of MS 1

IALA Guideline 1089 on Provision of Vessel Traffic Services (INS, TOS, and NAS) provides guidances on the deliveries of three different types of services provided by a VTS: INS, traffic organization service (TOS), and navigational assistance service (NAS).

According to Resolution A.857(20) on Guidelines for Vessel Traffic Services, an INS provided by a VTS is defined as “a service to ensure that essential information becomes available in time for onboard navigational decision-making”. Resolution A.857(20) also states that “the information service is provided by broadcasting information at fixed times and intervals or when deemed necessary by the VTS or at the request of a vessel, and may include for example reports on the position, identity and intentions of other traffic, waterway conditions, weather, hazards, or any other factors that may influence the vessel’s transit”.

Examples of the types of information provided by a VTS to operate an INS are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Examples of the types of information that may be provided by a VTS to operate an INS (IALA Guideline 1089) [8,9].

4.2. Purpose

The purpose of this MS is to provide data in a digital format to support a VTS INS and to create a means to reduce administrative burden and information overload, reduce miscommunication due to external interference, simplify work procedures, promote sustainable shipping and increase navigational safety.

Information provided in a digital format could complement and/or replace verbal/voice communications. The steps to achieve this transition to digital information exchange may vary in different areas and for different types of vessels. Details about digital information exchange should be published by VTS authorities.

4.3. Operational Approach

The digitalization of information will diversify communication means between shore authorities and vessels and will affect VTS procedures regarding provision of information.

Not all vessels are capable of receiving information in a digital format. Provisions should, therefore, be made to ensure that less capable vessels are receiving information they require. VTSs should remain the primary contact with vessels for urgent and important messages and to ensure communications with mariners.

4.4. Relations to Other MSs

MS 1 has relationships with other MSs, making it affect VTSs. Examples may be different depending on coastal state arrangements.

Examples of information are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Relations to other maritime services [8].

5. MS 6—Pilotage Service

The submitting organization is the IMPA; the coordinating bodies are the IMO and IMPA [8].

5.1. Description of MS 6

Ships proceeding or leaving a port or a specific area should have easy access to information regarding the pilotage service provided. Information, such as local regulations, contact, notices, means of boarding, boarding point, limitations, or pilot booking procedures, could be accessible by electronic means, where available.

The information provided through this service is not piloting information, as pilotage is a service physically performed on board ships by duly qualified and certificated or licensed maritime pilots.

5.2. Purpose—Information to Be Provided

This MS is limited to information provided to ships regarding a pilotage service in a given geographic area. It does not address the act of piloting, which is provided by a pilot on the bridge of a ship.

The purpose of this MS is to provide information related to a pilotage service when planning an operation before a pilot boards a vessel by using modern technology and common standards.

5.3. Operational Approach

Pilot organizations providing pilotage services in an area could provide information to ships about the pilotage services in a digital and easy accessible way. The information could be, as an example, portrayed as a layer on the ECDIS or in a graphical display. This information could include, for inbound ships, the location(s) of pilot station(s) or boarding point(s) in latitude/longitude or distances and bearings from a location, or an aid to navigation. In addition, the transmitted information could include VHF channels to contact the pilot or pilot boat. Typically, the pilotage service information will not be provided by the pilot, but rather by the pilot organization, because the pilot must be engaged in the actual performance of his/her pilotage duties.

In Reference [14], it is recalled that the initial description of MS 6 was drafted by the International Maritime Pilots’ Association (IMPA). The IMPA indicated that it was satisfied with the level of description provided so far and that no further work was required. The IMPA expressed its concern that trying to harmonize pilot booking services through MSs, as discussed in the IMO Facilitation Committee (FAL) Correspondence Group, might not be consistent with pilotage services around the world.

Examples of information are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Examples of information in MS 6 [8].

5.4. User Needs and Relations to Other MSs

Ships are concerned by this service and need to know the pilot boarding/disembarking position, the pilot request procedures, local and special regulations, and the compulsory use of tugs.

MS 6 has relationships with other MSs, so that it affects the pilot boarding operation and contributes to safe and efficient operations.

6. MS 7—Tug Service

The submitting organization is Norway; the coordinating bodies are the IMO and Norway [8].

6.1. Description of MS 7

This MS ranges from small vessels with limited capacity and service in ports and rivers to ocean-going vessels built for complex operations and salvage. This service contributes to the safety of navigation, protection of the marine environment, and efficiency of marine transportation by conducting different types of operations, such as:

- transportation (personnel and staff between ports and anchorages);

- ship assistance (e.g., mooring);

- salvage (grounded ships or structures);

- shore;

- towage (harbour/ocean);

- escort; and

- oil spill response.

The needs of tug services differ from port to port and varied for different types of vessel and cargo. In some cases, information about a tug service capacity and/or availability may be difficult to obtain due to communication deficiencies. This MS is intended to improve information availability of tug services.

Tug services would encompass all kinds of tugs, such as:

- conventional tugs;

- azimuth stern drives;

- tractors; and

- rotors.

Examples of information are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Examples of information shared in a tug service [8].

6.2. Purpose—Information to Be Exchanged

This MS aims to facilitate access to all necessary tug-related information required by ships heading to ports, in order to optimize transit times and promote efficient movements of goods and persons by using modern technology and common standards.

Effective communications and exchanges of information between relevant stakeholders would contribute to efficient tug services. Electronic exchange of information would significantly contribute to the improvement of this service. For example, notifying a ship officer in advance about tug availability in a port could lead the ship to adapt its speed accordingly. In some cases, this may prevent a requirement to anchor the ship. The types of information, which can be exchanged, include:

- ETA (Estimated Time of Arrival) request;

- confirmation requests;

- updates on transit status and tug availability;

- updates among stakeholders; and

- standardized messages to overcome language barriers.

6.3. Operational Approach

Tugs operations are a key element of the marine transportation chain, and well-coordinated procedures and communication means should be in place to ensure fluid movement of ships.

Like the port support service, this service can be significantly improved by utilization of a common platform to exchange information electronically and keep users updated on a regular basis about the status of operations, for both ships’ operators and tug owners. The tug service aims mainly to improve communications involved in a ship request, rather than altering current operational procedures. Some of these communications may include:

- ship’s size;

- number of tugs required;

- time, when the service is required;

- time, when the tug may be on site;

- estimated duration of operations; and

- end of operations.

Access to this information electronically would enhance the awareness of a ship’s timestamp. Increased connectivity, through sharing of harmonized digital information regarding tug operations in ports, rivers, or deep sea, will enhance efficiency through just-in-time services. It will also reduce human factor errors, such as language barriers or outdated information in publications, enhancing efficiency and access to information in a fast and easy-to-use manner.

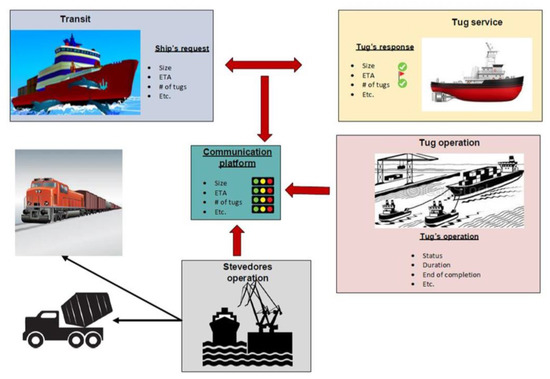

Example of an electronic communication platform for all actors involved in tug operations is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Example of an electronic communication platform for all actors involved in tug operations [8].

6.4. User Needs

Easy and timely access to tug service information is crucial to ensure fluidity in the transportation chain. The information required from this service is mainly related to:

- capacity;

- availability;

- time of response;

- status of operations; and

- durations of operations.

In return, tug services should be regularly updated on the ship’s ETA/ATA (Estimated Time of Arrival/Actual Time of Arrival) to plan their operations accordingly. In the event of an unanticipated change, ship officers should be able to communicate tug services easily with each other to keep both parties informed about the evolving situation and allow for proper decision-making. An easy communication link should be part of user needs, and this communication link would also benefit all other actors.

6.5. Relations to Other MSs

Relations to other MS are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Relation to other maritime services [8].

7. Conclusions

This paper supports the IMO guidance on the definition and harmonization of the formats and structures of MSs in the context of e-Navigation and decisions to consolidate the descriptions of MSs and consider them together with all involved international organizations and interested member states, in order to harmonize the provision and exchange of maritime information and data. The paper strongly supports the initial descriptions of MSs in the context of e-Navigation approved by the MSC. The information contained in this paper constitutes the descriptions of two selected examples of MSs, an initial contribution to the harmonization of the formats and structures of pilotage and tug services.

This document shows a reasonable understanding of new developments in new technologies and e-Navigation for the maritime industry. The work has a good theoretical base, using useful references and important and updated IMO resolutions. It presents and studies the operational use of the e-Navigation concept in terms of requirements, implementation plans, and potential benefits/limitations in the maritime sector. It is possible to remotely operate several ships from land and over large geographical areas. The technology is used in different ways on vessels to show that the solutions can be applied widely. The marine scientific and engineering community aims to test and further develop key technologies linked to fully autonomous navigation systems, intelligent machinery systems, self-diagnostics, prognostics, and operation scheduling, as well as communication technologies enabling a prominent level of cybersecurity and integrating vessels into upgraded e-infrastructures.

Short descriptions of pilotage and tug services are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Initial descriptions of pilotage and tug services [8].

In addition, the information service MS 1—VTS INS was also described as a template of what the initial description of the service should look like. The initial description of each of MSs is expected to be next periodically updated, taking into account developments and related work on harmonization.

All opportunities should now be used to promote the existence of the guidance and encourage those involved in MSs activities to implement the content of the guidance and, in the meantime, to expand the initial descriptions provided.

In conclusion, the following points should be noted:

- –

- Emergence of new technologies and development of autonomous ships are key nowadays in the maritime industry with great contribution of the IMO;

- –

- The paper tries to explain two important IMO resolutions for e-Navigation guidance, developments, and implementation;

- –

- The paper provides a great example for tug services—key elements in marine transportation near ports, of which well-coordinated procedures assure fluid movements of ships and goods;

- –

- Modern ships most probably will use less crew, but they will have high responsibilities for safe and efficient navigation;

- –

- There is a development of better data exchanges and communications from ship to ship and ship to shore;

- –

- Tools are created to have navigations and communications more reliable and minimize human errors, especially those with a potential for loss of life, injuries, maritime collisions, oil spills, environmental damage, and commercial costs;

- –

- Automation and autonomous technologies and next-generation autonomous ships have been tested;

- –

- The concept of e-Navigation was developed for remote-operated and autonomous maritime transport;

- –

- Shipboard systems for autonomous navigation, self-diagnostics, prognostics, operation scheduling, and telecommunications are being developed, including digital MSs.

Funding

This study was financed by the Gdynia Maritime University, the research project: WN/2019/PZ/01.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Baldauf, M.; Kitada, M.; Mehdi, R.A.; Dimitrios, D. E-Navigation, Digitalization and Unmanned Ships. Challenges for Future Maritime Education and Training. In Proceedings of the 12th International Technology, Education and Development Conference INTED2018, Valencia, Spain, 5–7 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Formela, K.; Neumann, T.; Weintrit, A. Overview of Definitions of Maritime Safety, Safety at Sea, Navigational Safety and Safety in General. TransNav Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 2019, 13, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, M.; Oltmann, J.-H. IMO e-Navigation Implementation Strategy—Challenge for Data Modelling. TransNav Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 2013, 7, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintrit, A. Development of the IMO e-Navigation Concept—Common Maritime Data Structure. In Modern Transport Telematics; Mikulski, J., Ed.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 239, pp. 151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Weintrit, A. Prioritized Main Potential Solutions for the e-Navigation Concept. TransNav Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 2013, 7, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Guze, S.; Smolarek, L.; Weintrit, A. The area-dynamic approach to the assessment of the risks of ship collision in the restricted water. Sci. J. Marit. Univ. Szczec. 2016, 45, 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- IMO MSC.467(101). Guidance on the Definition and Harmonization of the Format and Structure of Maritime Services in the Context of e-Navigation; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IMO MSC.1/Circ.1610. Initial Descriptions of Maritime Services in the Context of e-Navigation; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IALA Guideline 1115. Maritime Service Portfolios: Digitising Maritime Services, 1st ed.; IALA Working Paper, ENAV-19-14.2.9; International Association of Lighthouse Authorities: Saint Germain en Laye, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Weintrit, A. The Harmonization of the Format and Structure of Maritime Service Portfolios. In Management Perspective for Transport Telematics; Mikulski, J., Ed.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 897, pp. 426–441. [Google Scholar]

- Weintrit, A. Technical Infrastructure to Support Seamless Information Exchange in e-Navigation. In Activities of Transport Telematics; Mikulski, J., Ed.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 395, pp. 188–199. [Google Scholar]

- Weintrit, A.; Zalewski, P. Guidelines for Multi-System Shipborne Radionavigation Receivers Dealing with the Harmonized Provision of PNT Data. In Smart Solutions in Today’s Transport; Mikulski, J., Ed.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 715, pp. 216–233. [Google Scholar]

- IMO Resolution, A.857(20). Guidelines for Vessel Traffic Services; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- IMO NCSR 7/8. Consideration of Descriptions of Maritime Services in the Context of e-Navigation. In Report of an Informal Meeting of Member States and International Organizations Acting as Domain Coordinating Bodies for the Further Development of Descriptions of Maritime Services in the Context of e-Navigation; Note by the Secretariat; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IALA Guideline 1089, Provision of VTS Services (INS, TOS, NAS), 1st ed.; International Association of Marine Aids to Navigation and Lighthouse Authorities: Saint Germain en Laye, France, 2012.

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).