Abstract

A sand-laden vortex is a common phenomenon in marine engineering, particularly in coastal near-bed water intake and pumping facilities, and is widely recognized as an unfavorable factor affecting the safe and efficient operation of hydraulic machinery. The purpose of this study is to explore the energy characteristics of the development process of a sediment-laden vortex in the inlet pool. The research method is to use the V3V (Three-Dimensional Velocity Measurement System) to measure the three-dimensional velocity field of a sand-laden vortex, and analyze the energy characteristics of the evolution process of a sand-laden vortex in combination with energy gradient theory. The results indicate that in the early stage of vortex development, the turbulent kinetic energy of the sand-laden vortex gradually increases with time. After reaching its maximum value, the turbulent kinetic energy of the sediment-laden vortex continues to develop for about 0.4 s, then sharply decreases and completely dissipates within 0.3 s. The axial development speed of the vortex is closely related to the distance from the pump impeller. The energy gradient during the vortex evolution process indicates that the energy around the sand-laden vortex at different stages accumulates and dissipates as the vortex evolves. The research results of this article provide mechanistic insights into the evolution of a sand-laden vortex and offer theoretical support for sediment control and hydraulic optimization in marine and coastal pumping systems.

1. Introduction

Sand-laden pumping systems are widely encountered in marine and coastal engineering, such as seawater intake and discharge facilities for desalination plants, offshore platforms, coastal pumping stations, and other near-bed hydraulic infrastructures. These systems play an essential role in marine resource utilization, environmental protection, and the safe operation of coastal and offshore engineering facilities [1,2,3]. The stability and reliability of hydraulic machinery operating under sediment-laden conditions are therefore of great importance to marine engineering safety and operational efficiency. However, in marine and coastal intake systems, complex flow phenomena such as free-surface vortex and bottom-attached vortex frequently occur in inlet channels and intake pools. When these vortex structures interact with suspended sediments, particularly in sandy seabed or nearshore environments, more severe vortex–sediment coupling effects may arise compared to in clear-water conditions [4,5]. These coupled phenomena can significantly intensify hydraulic instability, sediment entrainment, and mechanical wear, thereby posing serious challenges to the design, operation, and maintenance of marine and coastal pumping systems.

The harmfulness of a vortex is reflected on multiple levels, and its essence lies in the disruption of stable and uniform inflow conditions. Firstly, from the perspective of hydraulic performance, a vortex can introduce strong pre-swirl and turbulence, leading to a significant decrease in the efficiency of pumps or turbines, and causing unit vibration and noise, affecting operational quality [6,7]. Secondly, what is even more serious is its physical destructive effect. A strong vortex can carry air deep underwater and into the flow channel, causing cavitation during unit operation and generating huge instantaneous impact forces on the blade surface, resulting in material fatigue and erosion, known as cavitation damage. At the same time, in the sediment-laden water flow, the vortex acts as an efficient “conveyor”, concentrating high concentrations of sediment particles and directing them towards the surface of the flow passage components. This interaction with cavitation promotes a synergistic and amplified erosion effect, greatly accelerating the damage process of key components such as the impeller, guide vanes, and volute. The combined effect of cavitation and abrasion can cause metal materials to be lost at an alarming rate, not only significantly increasing maintenance costs and downtime, but also potentially causing structural failures such as wheel cracks and bearing damage, ultimately leading to catastrophic unit accidents. Therefore, in-depth research on the generation mechanism, evolution law, and prevention and control strategies of vortex at the inlet of sediment pumping stations and hydropower stations is a core issue to ensure the long-term safe, stable, and efficient operation of the project, with clear engineering urgency and theoretical value [8].

Faced with the complex problem of water–sand–air multiphase flow, researchers at home and abroad have constructed a research system based on physical model experimental testing and computational fluid dynamics numerical simulation as the two pillars, which complement each other and jointly promote the deepening of understanding of this problem [9,10,11,12,13,14].

In terms of experimental testing and research, scaled physical models based on similarity criteria such as the Froude criterion for gravity similarity and resistance similarity are the most direct and reliable means of observing and quantifying vortex phenomena [15,16]. The current status of research indicates that experimental work mainly focuses on the following aspects. The first is systematic observation. By using advanced measurement methods such as high-speed cameras, particle image velocimetry, and ultrasonic Doppler velocimetry, the types, locations, core structures, vortex intensity frequencies, and spatiotemporal evolution laws of a vortex can be accurately captured under different inlet geometries (such as cantilever height, rear wall distance, horn tube inlet shape), inflow conditions (inlet flow rate, water level, Froude number), and sediment characteristics (sediment concentration, particle size distribution, density). Based on a large amount of experimental data, the academic and engineering communities have established vortex intensity classification standards, such as those proposed by Andreas, providing a basis for engineering risk assessment [17]. The second aspect is mechanism exploration. The experiment measures the pressure distribution, flow velocity field, and aeration concentration of the vortex core to deeply analyze its energy dissipation mechanism and suction mechanism. For sediment conditions, the experiment focuses on observing the transport and sorting laws of sediment under the action of a vortex, revealing the influence of the vortex on local bed surface erosion and sediment entrainment. The third research aspect is measurement verification. The physical model is the best platform to test the effectiveness of various vortex elimination measures, such as setting vortex elimination beams, diversion piers, breast wall openings, ventilation curtains, etc. By comparing the improvement of flow state and the degree of vortex strength reduction before and after the implementation of the measures, it provides a direct basis for engineering optimization design.

In the field of numerical simulation research, with the rapid development of computer technology, CFD has become an indispensable and powerful tool for studying this problem [18,19,20]. Its advantage lies in the ability to break through the scale limitations and measurement blind spots of physical models and obtain detailed information on all variables in the entire flow field. The current research status shows that numerical simulation techniques have evolved from early single water phase, steady-state Reynolds averaged simulations to complex transient simulations capable of handling water sand gas multiphase flows. Researchers generally use the VOF method to track free interfaces, combined with mixture or Eulerian multiphase flow models to describe the distribution and motion of sediment and air phases, and choose turbulence models such as SST k-ω for Reynolds-averaged simulation, or further use large eddy simulation or even direct numerical simulation to analyze large-scale vortex structures. Through these high-fidelity numerical models, researchers can “visualize” and quantify the complete transient process of vortex generation, development, and shedding; accurately analyze the pressure field, velocity field, and vorticity field inside the vortex core; and thus understand the instability mechanism of vortex and their interaction dynamics with sediment particles at a deeper level. Numerical simulation greatly expands the parameter space of research, allowing for fast and low-cost virtual experiments and optimization comparisons of multiple design schemes, forming an effective complementary and verification relationship with physical experiments [21,22,23].

In summary, although extensive experimental investigations and numerical simulations have advanced our understanding of vortex-related hazards in sediment-laden flows and have inspired various mitigation measures in engineering practice, several key aspects remain insufficiently resolved. In particular, prior studies have mostly focused on either clear-water vortices or macroscopic vortex suppression performance, while the stage-resolved evolution of sand-laden vortices and the associated instability mechanism—including how sediment presence modifies the vortex core development, turbulent energy distribution, and the spatial–temporal characteristics of flow instability—remains inadequately quantified. Moreover, a physically interpretable indicator that can be directly linked to vortex initiation, growth, and decay under sediment-laden conditions is still lacking for intake environments [24,25,26]. Therefore, the objective of this study is to quantify the evolution (development–maintenance–decay) and interpret the onset and dissipation of vortex-induced instability using the energy gradient theory framework.

In this paper, we use a high-precision 3D velocity field V3V testing system to study the motion characteristics of sand-laden vortex in the pump sump representative of intake basins used in coastal and marine pumping/intake facilities. The research results of this paper can provide a clearer mechanistic understanding and practical guidance for vortex risk assessment and mitigation in marine/coastal intake and pumping systems.

2. Test Device and Equipment

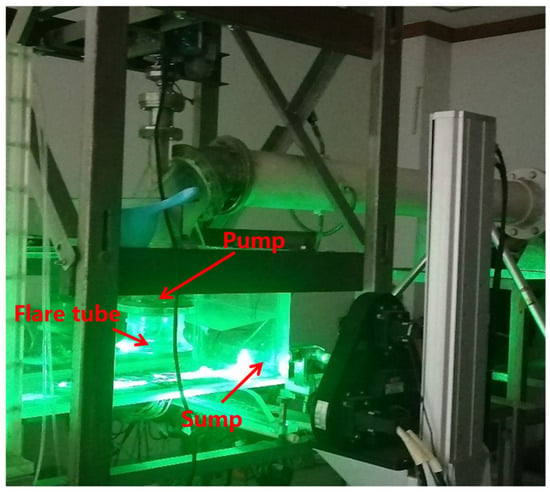

In this study, the test bench consists of an open-top water tank. The test subject is the bottom-bound vortex formed beneath an axial flow pump, with the test flow being water containing solid particles. The testing instrumentation comprises a 3D velocity testing system, V3V, which employs three-dimensional laser testing to capture the vortex’s three-dimensional spatial flow field. The test bench and test conditions are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

V3V laser testing in the pump sump.

The 3D velocity testing system V3V extracts the three-dimensional positions of particles directly from captured images through pattern search algorithms. This measurement method is completely different from traditional stereo vision photogrammetry methods. Compared with traditional 3D PIV measurement systems, the V3V measurement system can more reliably achieve flow field measurement in high-density particle velocity measurement. The V3V system used volume self-calibration to minimize errors in velocity measurements. The V3V system enables the complete measurement of instantaneous 3D velocity fields within a real fluid cubic volume. The system’s maximum measurable volume can reach 140 mm × 140 mm × 100 mm. The temporal resolution was set to 10 Hz, and 100 image pairs were collected per vortex cycle. The uncertainty in velocity was found to be 0.2% based on repeatability tests.

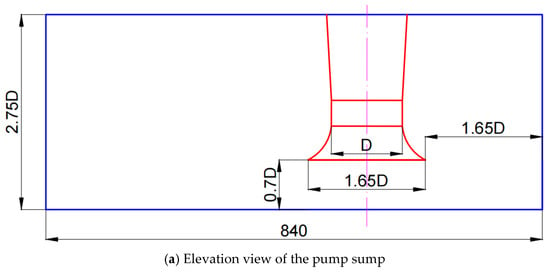

The axial-flow pump impeller has 4 blades with a hub ratio of 0.4, and an impeller diameter of 120 mm. The rotational speed was set to 2200 r/min. The detailed geometric dimensions of the pump sump are shown in Figure 2, where the sump depth, length, flare tube diameter, submergence depth, and backwall distance are defined relative to the suction pipe diameter D. The key geometric parameters of the pump sump are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 2.

The detailed geometric dimensions of the pump sump.

Table 1.

Basic parameters of pump sump.

The purpose of this experiment is to investigate the sand-laden vortex within the pump sump of an axial-flow pump unit. Therefore, it must be conducted under experimental conditions where these vortices are clearly observable. Extensive experimental observations reveal that during high-flow operating conditions, the frequency of sand-laden vortex occurrence is elevated, accompanied by noticeable unit vibration and noise. Consequently, the flow rate scheme selected for this study employs high-flow operating conditions. Specific operating parameters are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Operating condition.

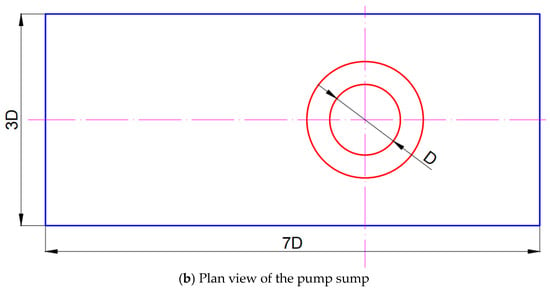

In this experiment, the water flow contained solid particles, with tracer particles used to represent the solids. The tracer particles had a characteristic diameter of 0.02 mm and were suitable for both three-dimensional laser measurement and sand-laden flow conditions, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Tracer particles for experiment.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Particle Morphology During the Development Process of Sand-Laden Vortex

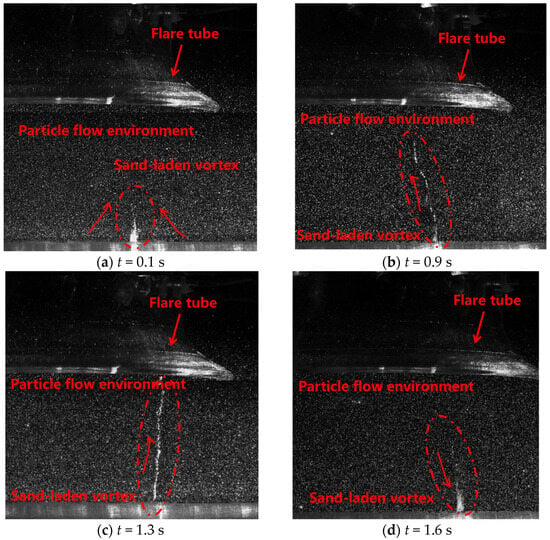

It can be seen that the vortex at the bottom gradually increases, reaches its maximum, and then remains for a short period of time before rapidly decreasing and dissipating, as shown in Figure 4. Under this condition, the evolution period of the sand-laden vortex is 1.9 s. Under the action of the pump impeller, the attached vortex is generated on the bottom plate. At the incipient stage of the vortex, the vortex appears in a budding state, and the surrounding particles gather into the vortex (Figure 4a). With the passage of time, the vortex grows upwards in the development stage, extends to the inlet direction of the impeller, and gradually enters the flare tube (Figure 4b). After the vortex reaches stability, it will continue to exist in the flare tube and enter the maintenance stage. At this time, the particles will gather in the vortex and enter the flare tube with the vortex (Figure 4c). At the decay of the vortex, the vortex will gradually subside from the flare tube, and the particles are mainly concentrated at the bottom of the vortex tube (Figure 4d). In the dissipation stage, after the rotational energy is depleted, the sediment-laden vortex rapidly disappears.

Figure 4.

V3V testing system captures bottom vortex particle images.

The vortex evolution period is approximately 1.9 s. To compare across different operating conditions, this period is non-dimensionalized using the impeller period Timp. The non-dimensional period T* is calculated as

where is the impeller rotation period (with n = 2200 r/min ) and is the vortex evolution period (with = 1.9 s ).

Under the present operating condition, the non-dimensional vortex evolution period is ≈ 69.7, indicating that one complete vortex evolution cycle spans approximately 70 impeller revolutions.

3.2. Velocity Gradient Distribution in the Vortex Region at Different Cross-Sections and Moments

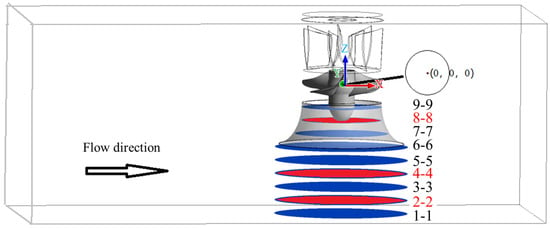

To facilitate analysis of the velocity field data in the V3V test area, the measurement zone has been divided into nine characteristic cross-sections to further examine the velocity characteristics within the entire vortex space. Cross-section 1-1 is selected 3 mm above the bottom of the intake pool. Nine characteristic cross-sections were selected every 20 mm along the vortex development direction, from the bottom of the intake pool to the inlet of the impeller, to analyze the velocity gradient distribution on different cross-sections. The locations of the characteristic cross-sections are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Location map of characteristic section.

To reduce noise amplification during gradient calculation, we applied spatial filtering before computing the velocity gradients. A sensitivity test with different filter window sizes confirmed that the high-gradient regions and key results remained unchanged. To analyze the velocity gradient intensity in the vortex-core region during the evolution of the bottom-attached vortex, the velocity gradient intensity G is defined as

—velocity gradient intensity in the x-direction;

—velocity gradient intensity in the y-direction;

—velocity in the x-direction;

—velocity in the y-direction.

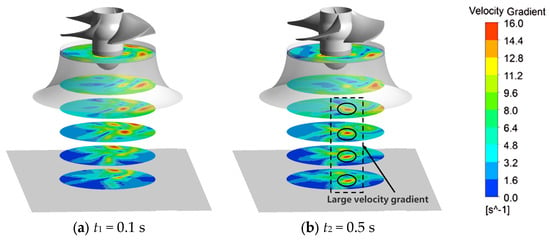

The velocity gradient distribution within the complete space of the vortex region at different time points was obtained through the V3V test, as shown in Figure 6. Due to the insignificant changes in some cross-sections, six cross-sections (1-1, 3-3, 5-5, 6-6, 7-7, and 9-9) were ultimately selected for analysis. The distribution of velocity gradient in the vortex zone below the horn tube and in the same part of the test area is consistent. The velocity gradient at the center of the vortex core is the largest, and the vortex zone is surrounded by a concentrated distribution of large velocity gradients centered around the vortex. During the time period of t3-t4 in the maintenance stage, the velocity gradient distribution on different height sections is characterized by a large velocity gradient distribution at the center of the vortex and a small velocity gradient distribution around the center of the vortex. The variation law of the high velocity gradient accumulation area in the vortex zone inside the horn tube is consistent with the distribution law of the velocity gradient in the vortex zone below the horn tube. In the incipient stage, the high velocity gradient accumulation area begins to appear and continues to develop. In the maintenance stage, the distribution range of the high velocity gradient accumulation area reaches its maximum, and then rapidly decreases and disappears. At the same time, a high velocity gradient accumulation zone gradually appears in the vortex area from bottom to top, and during the maintenance stage, there is a high velocity gradient accumulation zone from the bottom of the inlet water tank to the inlet of the impeller. Then, during the decay stage, it quickly disappears downwards from the impeller inlet.

Figure 6.

Velocity gradient distribution in the vortex area of the complete space at different times.

3.3. Changes in Vortex Dissipation Based on Energy Gradient Theory

In recent years, Dou Huashu and others have proposed a new theory based on Newtonian mechanics and compatible with the N-S equation for analyzing flow instability and transition problems—the energy gradient theory. This theory is developed within the framework of Newtonian mechanics and is fully compatible with the Navier–Stokes equations. In this context, viscous fluid flow refers to the flow of real fluids with finite viscosity, as opposed to ideal or inviscid fluids. According to the energy gradient theory, the instability of viscous flows, including both laminar and turbulent regimes, is governed by the relative magnitude of the transverse energy gain ΔE in the normal direction and the mechanical energy loss ΔH caused by friction along the streamline direction [27,28]. The relatively large energy obtained in the spanwise direction will amplify the disturbance, while the energy lost along the streamline direction will absorb the disturbance, making the flow more stable. For any given disturbance, whether the flow remains stable or becomes unstable depends on the relative magnitude of disturbance amplification (related to the transverse energy gradient) and disturbance dissipation (related to the streamwise energy loss). When this competition exceeds a critical condition (often expressed via a threshold of K), the disturbance can no longer be sufficiently damped, leading to the onset of flow instability and local intensification of turbulence. This is consistent with the theory of vortex dynamics, which states that the decisive condition for the generation of a sediment-laden vortex is the accumulation of rotational energy greater than dissipation and continuous growth of the vortex during the flow process. The appearance of a vortex is a form of flow instability, and the motion law of a vortex should theoretically follow the N-S equation. In the rapidly changing space-time, both migration acceleration and local acceleration contribute to the development of a vortex. Therefore, quantitative analysis of the energy gradient changes in different stages of sediment-laden vortices can provide a deeper understanding of the mechanism of sediment-laden vortex development. According to the energy gradient theory, the definition of the energy gradient K function is as follows [29,30]:

E—total fluid pressure;

H—loss of mechanical energy along the streamline direction;

n—normal direction of fluid flow;

s—the streamline direction of fluid flow.

K is a dimensionless flow field function, representing the ratio of normal energy gradient to flow energy loss. Places with higher K values are more prone to instability.

In [31,32], Dou Huashu and others explain in detail the solution methods for and , among which

U—velocity magnitude (m/s);

ρ—fluid density (kg/m3);

p—static pressure (Pa);

u—velocity component in the x-axis direction (m/s);

v—velocity component in the y-axis direction (m/s);

w—velocity component in the z-axis direction (m/s);

n—coordinate along the normal direction of the streamline (m);

μt—turbulent dynamic viscosity (Pa·s).

Uncertainty in G and K mainly arises from V3V velocity uncertainty, numerical differentiation, and assumptions in estimating and μt. We therefore report K primarily as a relative indicator and focus on robust spatial/temporal trends rather than absolute magnitude.

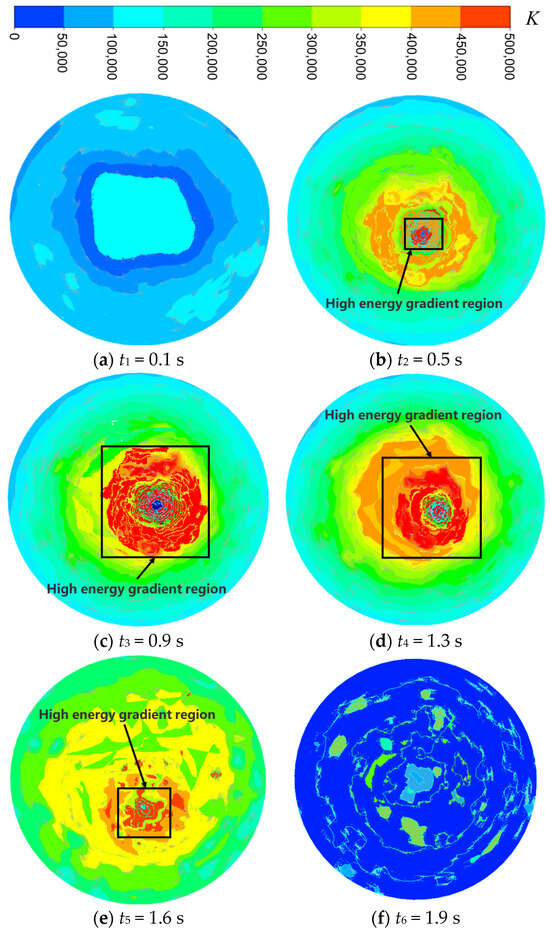

The energy gradient theory is used to analyze the results of the test. The energy gradients around the vortex at different stages of the same cross-section are analyzed. As the sediment-laden vortex gradually generates from the bottom of the pump sump, the cross-section is selected at a distance of 3 mm from the bottom of the pump sump, as shown in Figure 7. According to the energy gradient calculation method, the energy gradient distribution near the sediment-laden vortex at different stages is obtained. Figure 7 shows the K value distribution of section 1-1. The red region specifically denotes areas with relatively high K values, while the adjacent yellow and blue regions correspond to medium and low K value ranges, respectively, forming a distinct gradient distribution. The higher the K value, the greater the turbulence intensity and the more unstable the flow field.

Figure 7.

Distribution of energy gradient function K at different stages of sediment-laden vortex.

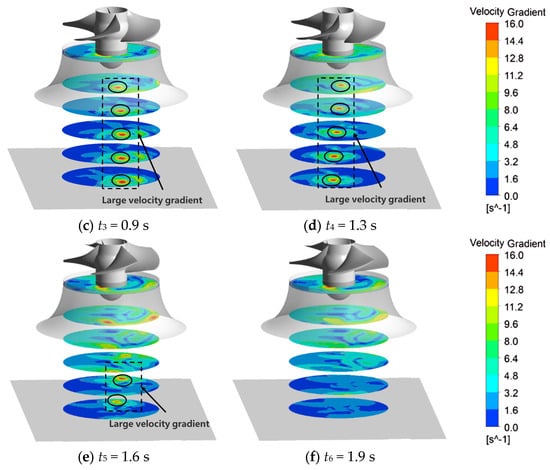

In the incipient stage, the distribution of K values is uniform, and before 0.5 s, there is no obvious energy gradient, and the area with larger K values is smaller. According to the formation principle and motion characteristics of sediment-laden vortices, the formation of a sediment-laden vortex is due to the accumulation of rotational energy. As shown in Figure 7b, the energy gradient at the center of the vortex is very small. This is because the velocity and pressure inside the vortex tube are stable, and the area with a large energy gradient distribution starts to form from a point. At 0.5 s, the area with a large K value begins to appear, indicating that the flow field at the location where the vortex occurs begins to become unstable and begins to form around the vortex.

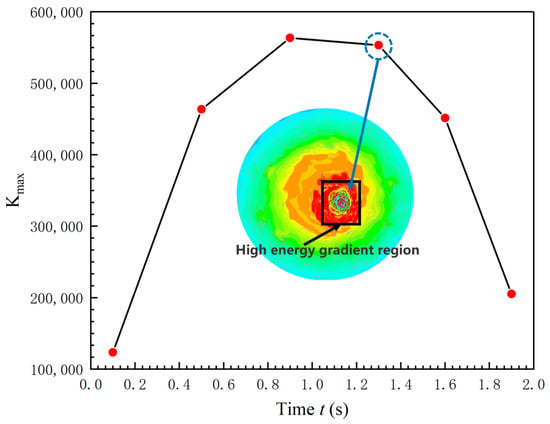

As time goes by, the energy gradient K value around the sand-containing vortex continues to increase. After 0.9 s, the area with a larger distribution of K values expands around the center of the vortex. Due to the change in the distribution of the area with a larger energy gradient K value, the energy gradient at the center of the vortex continues to move, which is consistent with the characteristics of the sand-containing vortex. As shown in Figure 8, at 0.9 s, the area with a larger K value reaches its maximum, indicating that the vortex occurs in a region of flow instability. The stronger the vortex, the more severe the flow instability, and the larger the energy gradient. The maximum energy gradient range around the sediment-laden vortex is reached between 0.9 s and 1.3 s, indicating that the strength of the sediment-laden vortex reaches its maximum during this period and the sediment-laden vortex develops stably. Due to the instability of the sand vortex and its sensitivity to the surrounding flow environment, disturbances in the surrounding environment after 1.3 s disrupt the stable distribution of energy gradient around the sand vortex. With the disappearance of the sand vortex, the energy gradient distribution around the sand vortex collapses, and the rotational energy gradually disappears. After 1.9 s, the energy gradient distribution of the cross-section tends toward 0, and there is a small difference in energy distribution. When the next sand vortex is formed, the energy gradient distribution changes repeatedly.

Figure 8.

The variation curve of Kmax inside the vortex core at different stages.

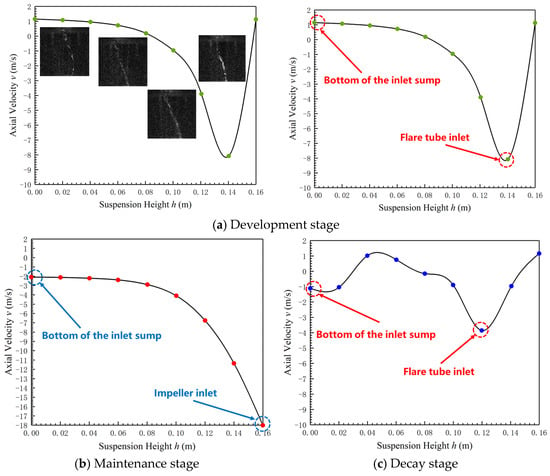

3.4. Analysis of Axial Development of Sand-Laden Vortex

By analyzing the temporal variation characteristics of the axial velocity inside the vortex core of the sand-carrying suction vortex, the variation law of the axial velocity inside the vortex core over time was obtained. The axial velocity profiles were extracted along the vortex core centerline near the impeller axis, and the negative sign indicates flow directed toward the impeller inlet. Analyzing the axial velocity changes within the vortex core at different heights also provides assistance in understanding the variation patterns of a sediment-laden suction vortex. According to the previous analysis, it can be seen that the axial velocity inside the vortex core varies greatly during the development stage, maintenance stage, and decay stage. Therefore, the focus is on analyzing the variation law of the axial velocity inside the vortex core during the development stage, maintenance stage, and decay stage with the height and position of the vortex. The results of the analysis of axial velocity variations in vortex cores across different developmental stages within the same vortex cycle are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Axial velocity variation curve inside vortex core at different stages.

In the development stage, the axial velocity inside the vortex core decreases first and then increases with the distance from the bottom of the pump sump. The decrease is small within 0.08 m, rapidly decreases within 0.08 m–0.14 m, and rapidly increases within 0.14 m–0.16 m. In the maintenance stage, the axial velocity inside the vortex core decreases continuously with the distance from the bottom of the inlet water tank. The decrease is small within 0.1 m and rapidly decreases after 0.1 m. This is because the suspended height of the pump device horn tube is 0.084 m. When the height from the bottom of the inlet water tank exceeds 0.08 m, the vortex enters the horn tube. Under the influence of the impeller rotation, the axial velocity inside the horn tube will sharply increase, and the decrease will be greater as it approaches the impeller inlet. This indicates that the axial velocity inside the vortex core of the sand suction vortex is closely related to the axial velocity around the vortex, and changes in the surrounding axial velocity will cause corresponding changes in the axial velocity inside the vortex tube. During the decay stage, the overall axial velocity inside the vortex core decreases first and then increases with the distance from the bottom of the pump sump, with some fluctuations. This is because during the vortex decay stage, the sand-laden suction vortex is unstable.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, we focus on investigating the motion characteristics of sand-laden vortex and their formation mechanisms. The V3V three-dimensional flow velocity testing system is used to measure the flow field before, after, and during different stages of vortex formation under the horn tube in the pump sump. The strength, kinetic energy, and energy gradient of the sediment-carrying vortex in the pump pool at different stages are analyzed.

- (1)

- Over one complete vortex cycle, the turbulent kinetic energy within the vortex region gradually increases with time, accompanied by a corresponding rotation and spatial redistribution of the high-energy region. After the energy distribution reaches its maximum spatial extent, it continues to develop for approximately 0.4 s, followed by a gradual contraction of the high-energy region, with the turbulent kinetic energy dissipating within about 0.3 s. Meanwhile, the intensity of the sand-laden vortex increases progressively during the development stage and then decreases rapidly during the decay stage, indicating a distinct stage-dependent evolution of vortex strength.

- (2)

- Energy gradient theory is employed to investigate the stage-dependent energy evolution associated with the formation and dissipation of the sand-laden vortex. The occurrence of the sand-laden vortex is accompanied by continuous variations in the energy gradient around the vortex region. With the accumulation of rotational energy in the flow field, the local energy gradient near the vortex core gradually increases, leading to the initiation and subsequent development of the vortex. High velocity gradient intensity is persistently concentrated around the vortex core and near the bottom region, indicating strong shear and momentum exchange between the rotating core and the surrounding flow. From the development stage to the maintenance stage, regions of elevated velocity gradient intensity and energy gradient function expand and reach peak values, and after stabilization, these regions remain relatively confined. As the vortex approaches collapse and dissipation, both the energy gradient function and velocity gradient intensity decrease rapidly and become spatially fragmented, reflecting the loss of vortex coherence and instability.

- (3)

- The axial development speed of the vortex is closely related to the distance from the pump impeller. The axial velocity within the vortex core exhibits distinct variation patterns during the development, maintenance, and decay stages. The axial velocity within the vortex core first decreases, then increases with suspension height during the development stage, exhibiting a steady decay trend during the maintenance stage. During the decay stage, the axial velocity becomes highly unsteady, characterized by intensified fluctuations, indicating the gradual breakdown of the coherent vortex structure.

- Limitations and practical implications

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the solid phase was represented by tracer particles for reliable V3V reconstruction; thus, the results primarily describe the carrier-flow kinematics under particle-laden visualization conditions rather than fully resolved two-phase sediment transport. Secondly, the evaluation of instability metrics (e.g., velocity gradient intensity and energy gradient function) is affected by derivative sensitivity and modeling assumptions (e.g., effective viscosity and pressure gradient estimation), and therefore we emphasize robust spatial–temporal trends instead of absolute magnitudes. Thirdly, the present findings are obtained for a representative open sump geometry and operating condition; extrapolation to other intakes should consider geometric and dynamic similarity.

Despite these limitations, the results provide practical guidance; the instability-prone region is concentrated near the vortex core and the intake-affected shear layer, indicating that vortex suppression and sediment mitigation measures should prioritize the vicinity of the intake entrance and the near-bed region, where the bottom-attached vortex initiates and intensifies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.X.; methodology, L.X.; software, L.X.; validation, G.C.; formal analysis, G.C.; investigation, G.C.; resources, X.S.; data curation, G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.X.; writing—review and editing, L.X. and X.S.; visualization, L.X.; supervision, X.S.; project administration, X.S.; funding acquisition, X.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 52306042).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly appreciate the constructive comments of the reviewers and editor.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Khanarmuei, M.R.; Rahimzadeh, H.; Kakuei, A.R.; Sarkardeh, H. Effect of vortex formation on sediment transport at dual pipe intakes. J. Sādhanā 2016, 41, 1055–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamini, O.A.; Movahedi, A.; Mousavi, S.H.; Kavianpour, M.R.; Kyriakopoulos, G.L. Hydraulic Performance of Seawater Intake System Using CFD Modeling. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.; Lou, Y.; Yu, D.; Hong, S.; Ji, G.; Ma, L.; Chang, H. Investigation of Energy Loss Mechanism and Vortical Structures Characteristics of Marine Sediment Pump Based on the Response Surface Optimization Method. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Cheng, L.; Zhu, B.; Jiao, W.; Zhao, H.; Shen, J. Multiscale formation mechanism and instability characteristic of the submerged vortices caused by a closed pump intake. J. Ocean. Eng. 2024, 313, 119287. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Liu, C.; Wang, Z. Study on the Vortex in a Pump Sump and Its Influence on the Pump Unit. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Zhang, L. Prediction and numerical analysis for pressure pulsation of axial-flow pump. J. Drain. Irrig. Mach. Eng. 2014, 32, 393–398. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W.; Leng, H. Performance prediction and experiment for pressure pulsation of interior flow in axial-flow pump. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2011, 42, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, L.; Yu, Z.; Xu, Y. Role of blade rotational angle on energy performance and pressure pulsation of a mixed-flow pump. J. Inst. Mech. Eng. 2017, 231, 227–238. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Yuan, M.; Cheng, L.; Jiao, W.; Luo, C. Exploring the vortex structure and its dynamic behavior induced by a closed pump sump. J. Ocean. Eng. 2024, 307, 118103. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulaziz, S.A.; Zahid, H.; Saqlain, A.; Masood, R.; Asim, Z. Mitigating surface vortex formation in pump sump intakes through anti-vortex devices: A comprehensive CFD study. Front. Phys. 2024, 12, 1456256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Yao, R.; Liu, C.; Zheng, W. Study of the formation and dynamic characteristics of the vortex in the pump sump by CFD and experiment. J. Hydrodyn. 2021, 33, 1202–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Xu, K.; Li, T.; Xiao, Y.; Hu, K.; Xu, Y.; Liu, X. Investigation of Sediment Erosion of the Top Cover in the Francis Turbine Guide Vanes at the Genda Power Station. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Ye, X.; Xiao, Y.; Guo, X.; Qin, H.; Tang, M. Effect of the Vortex on the Movement Law of Sand Particles in the Hump Region of Pump-Turbine. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire Diogo, A.M.A.; Maio Moura, P.J.D. Self-cleansing velocity in upward three-phase steady pipe-flow. J. Environ. Fluid Mech. 2023, 23, 847–877. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, T.; Hassan, R.; Morteza, M. A new approach on anti-vortex devices at water intakes including a submerged water jet. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2018, 133, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieneke, B. Volume self-calibration for 3D particle image velocimetry. Exp. Fluids 2008, 45, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, H.O. Formation of a weak vortex. Nature 1965, 207, 1247–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liang, H.; Jin, Y.; Yang, F.; Chen, F.; Yang, H. PIV Measurements of Intake Flow Field in Axial-flow Pump. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2015, 46, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Chirag, T.; Peter, J.; Ole, G. Investigation of the unsteady pressure pulsations in the prototype Francis turbines-Part1: Steady state operating conditions. J. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2018, 108, 188–202. [Google Scholar]

- Ansarand, M.; Nakato, T. Experimental study of 3D pump-intake flows with and without cross flow. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2001, 127, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Jiang, W.; Chen, Y.; Sun, A. Investigation on Low Frequency Pulsating and Draft Tube Vortex of Tubular Turbine. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2018, 49, 165–171. [Google Scholar]

- David, W.; Carl, F. Minimum pump submergence to prevent surface vortex formation. J. Hydraul. Res. 2009, 47, 142–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Cheng, L.; Tang, F.; Zhou, J.; Yan, F. Numerical Simulation of Three-dimensional Turbulent Flow for Opening Pump Sump. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2002, 33, 53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Liu, C.; Yang, F.; Zha, Z.; Yan, T.; Huang, J. Experiment on characteristics of pressure fluctuation at bottom of pumping suction passage. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2017, 48, 196–203. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Liu, C.; Tang, F.; Zhou, J.; Luo, C. Analysis of hydraulic performance for vertical axial-flow pumping system with cube-type inlet passage. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2014, 30, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z. Analysis on pressure pulsation of unsteady flow in axial-flow pump. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2007, 38, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, H.; Khoo, B.C. Investigation of Turbulent Transition in Plane Couette Flows Using Energy Gradient Method. J. Adv. Appl. Math. Mech. 2011, 3, 165–180. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, B.; Lu, F.; Wei, Y.; Chen, X. Modification of Meridian Plane Profile for Return Channel of a Centrifugal Compressor Based on Energy Gradient Theory. J. Chin. Soc. Power Eng. 2017, 37, 229–236. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, H. Mechanism of flow instability and transition to turbulence. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2006, 41, 512–517. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Dou, H.; Chen, X.; Wei, Y.; Liang, J.; Sun, Y.; Lu, F.; Diao, Q. Effect of Return Channel Stagger Angle on Performance of Centrifugal Compressor Based on Energy Gradient Theory. J. Zhejiang Sci-Tech Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2017, 37, 394–401. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, H.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Cui, B.; Li, Y. Flow Instability in Centrifugal Pump Based on Energy Gradient Theory. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2014, 45, 88–92+103. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.; Dou, H.; Jiang, W.; Chen, X.; Zhu, Z.; Cui, B. Effects of Number of Blades on Stability of Centrifugal Pump Based on Energy Gradient Method. J. Zhejiang Sci-Tech Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2016, 35, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.