Abstract

The increasing complexity of marine operations has intensified the need for intelligent robotic systems to support ocean observation, exploration, and resource management. Underwater swarm robotics offers a promising framework that extends the capabilities of individual autonomous platforms through collective coordination. Inspired by natural systems, such as fish schools and insect colonies, bio-inspired swarm approaches enable distributed decision-making, adaptability, and resilience under challenging marine conditions. Yet research in this field remains fragmented, with limited integration across algorithmic, communication, and hardware design perspectives. This review synthesises bio-inspired coordination mechanisms, communication strategies, and system design considerations for underwater swarm robotics. It examines key marine-specific algorithms, including the Artificial Fish Swarm Algorithm, Whale Optimisation Algorithm, Coral Reef Optimisation, and Marine Predators Algorithm, highlighting their applications in formation control, task allocation, and environmental interaction. The review also analyses communication constraints unique to the underwater domain and emerging acoustic, optical, and hybrid solutions that support cooperative operation. Additionally, it examines hardware and system design advances that enhance system efficiency and scalability. A multi-dimensional classification framework evaluates existing approaches across communication dependency, environmental adaptability, energy efficiency, and swarm scalability. Through this integrated analysis, the review unifies bio-inspired coordination algorithms, communication modalities, and system design approaches. It also identifies converging trends, key challenges, and future research directions for real-world deployment of underwater swarm systems.

1. Introduction

The sustainable management of marine resources remains one of the most pressing global challenges, requiring effective monitoring and exploration of ocean environments [1,2]. Over recent decades, Marine Robotic Systems (MRSs), including Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs), Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs), and Unmanned Surface Vessels (USVs) have revolutionised ocean observation and exploration [3,4]. A significant trend has been the move from single-vehicle autonomy to collective autonomy, where multiple vehicles cooperate to enhance spatial coverage, robustness, and mission adaptability.

Underwater robotic systems have evolved from early tethered Remotely Operated Vehicles used for inspection and intervention to increasingly autonomous platforms capable of long-duration sensing and decision-making. Today, AUVs, ROVs, and USVs are deployed across a wide range of missions, including seabed mapping, habitat and water-quality monitoring, offshore infrastructure inspection, search-and-recovery, and operations in remote environments such as under-ice and deep-sea regions. This progression towards higher autonomy and broader deployment has naturally motivated research into multi-robot and swarm systems, where cooperation can improve coverage, redundancy, and mission resilience in challenging ocean conditions [3,4].

Swarm robotics draws inspiration from natural collective behaviours observed in fish schools, bird flocks, and insect colonies, achieving complex coordination through simple local interactions [5]. Applying these principles to underwater domains introduces distinctive challenges including constrained communication bandwidth, acoustic delay, and limited power capacity, but it also creates opportunities for innovation [6,7]. Bio-inspired strategies are particularly relevant in marine environments, as aquatic organisms have evolved to thrive under precisely the constraints that limit robotic systems: restricted communication, positional uncertainty, and energy scarcity [4]. Fish schools, for instance, maintain formation through local perception rather than global positioning [8], providing direct insight into efficient coordination for robotic swarms.

Despite notable progress in individual marine robotic platforms, the field of underwater swarm robotics remains conceptually and methodologically fragmented. Extensive research has addressed aspects of swarm coordination, communication, and bio-inspired design, yet no unified framework integrates these dimensions into a coherent body of knowledge [7,9].

This review addresses this gap through four contributions. First, it unifies underwater swarm robotics across three coupled layers: bio-inspired coordination and optimisation, underwater communication constraints, and system architecture, so that algorithms are discussed alongside the physical and networking limitations that shape real deployments. Second, it focuses on marine-grounded bio-inspired methods and their underwater adaptations, using representative exemplars including AFSA, WOA, CRO, and MPA to illustrate common design patterns and evaluation considerations. Third, it introduces a four-dimensional classification framework based on communication dependency, environmental adaptability, energy efficiency, and swarm scalability, to position and compare approaches consistently. Fourth, it synthesises recurring evaluation gaps and open challenges to support more reproducible benchmarking and more informed algorithm selection. In contrast to many existing surveys that treat bio-inspired algorithms broadly across general robotics and to surveys that concentrate on narrower subsets of underwater coordination techniques, this survey is explicitly underwater-specific and integrates algorithms, communications, and architecture into a single comparative framework.

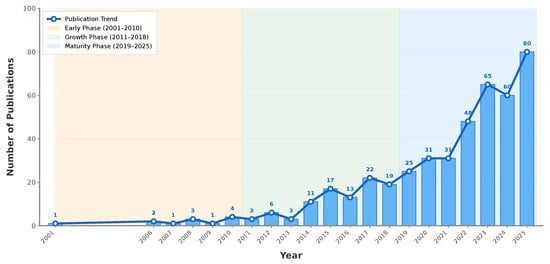

To contextualise the scope and evolution of this field, Figure 1 presents the publication trend for underwater swarm robotics research from 2001 to 2025.

Figure 1.

Publication trend for underwater swarm robotics research (2001 to 2025). The analysis includes 446 research articles from major databases, demonstrating exponential growth in the field. Search keywords included: marine swarm robotics, AUV swarm robotics, underwater swarm robotics, and related terms.

Review Methodology

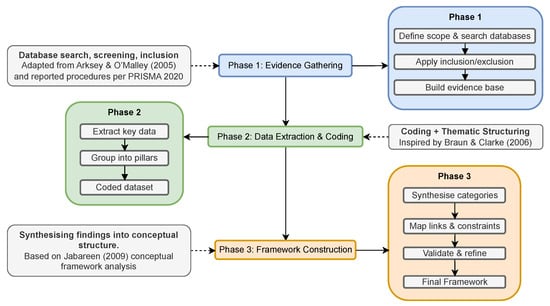

This study adopts a structured narrative review design guided by a transparent and replicable search and screening process. Figure 2 illustrates the three-phase methodological approach, which combines scoping review principles, thematic analysis, and conceptual framework development.

Figure 2.

Three-phase research methodology for synthesising the literature on bio-inspired underwater swarm robotics. The methodology integrates evidence gathering [10], systematic data extraction and coding [11], and integrated synthesis [12] to consolidate findings across algorithmic, communication, and system design domains.

Bibliographic records were collected from seven major scholarly databases (MDPI, OpenAlex, Scopus, Springer, ScienceDirect, IEEE, and Google Scholar) using combinations of keywords related to underwater swarm robotics and marine multi-robot systems. These databases were chosen because they are widely used indexing sources spanning robotics, marine engineering, and communications; however, we do not claim a precise percentage coverage of all relevant publications due to overlap and variability in indexing across venues. Keyword searches employed Boolean logic combining terms such as (“underwater” OR “marine”) AND (“swarm” OR “multi-robot” OR “multi-AUV”) AND (“robotics” OR “coordination” OR “cooperation”), along with specific phrases including “marine swarm robotics”, “AUV swarm robotics”, “underwater swarm robotics”, and related terms. All searches were restricted to English-language publications. The search window spanned publications from 2001 to 2025. Only peer-reviewed research articles were included; review papers, conference proceedings, theses, and non-peer-reviewed sources were excluded.

Records were screened to remove duplicates using DOI matching and title comparison, and to retain only studies that addressed underwater or marine swarm robotics, multi-AUV cooperation, or closely related multi-vehicle coordination problems in aquatic environments. Approximately 65% of the papers from the original sources were excluded during the filtering and consolidation process, which removed review papers, conference papers, and duplicate publications.

The final corpus comprises 446 peer-reviewed research articles. Titles, abstracts, and, where necessary, full texts were examined to confirm relevance and to assign each article to one or more thematic categories reflecting its primary contribution: bio-inspired coordination and control algorithms, underwater communication and networking strategies, and system design and implementation (including platforms, sensing, energy management, and validation). This thematic coding underpins the organisation of the review: Section 2 introduces the foundational context, Section 3, Section 4 and Section 5 synthesise coordination, communication, and system design themes, and Section 6 presents an integrative classification that links algorithmic, communication, and hardware perspectives across the corpus. It is important to acknowledge limitations: the dataset may have gaps as some journals and sources may have been missed, and the search strategy may not capture all relevant publications using alternative terminology.

2. Foundations of Marine Swarm Robotics

Underwater swarm robotics operates within a uniquely challenging domain that differs fundamentally from terrestrial and aerial environments. Understanding these challenges, the governing principles of swarm intelligence, and the relevance of bio-inspired design is essential for developing effective and sustainable Marine Robotic Systems. This foundational context establishes the environmental and conceptual constraints within which bio-inspired coordination, communication, and system design approaches must operate.

2.1. Characteristics and Challenges of the Underwater Environment

The underwater environment imposes physical, acoustic, and operational constraints that significantly influence the design and behaviour of swarm robotic systems. Unlike terrestrial or aerial systems, underwater platforms must operate in a medium that limits communication, localisation, sensing, and energy management.

A primary challenge is navigation. Global Positioning System (GPS) signals do not propagate underwater, forcing AUVs to rely on alternative methods such as Inertial Navigation Systems (INSs), dead reckoning, and acoustic positioning arrays [7,13]. State-estimation filters, particularly (extended) Kalman filtering and invariant EKF variants, are widely used to fuse noisy measurements and reduce drift in underwater navigation [14,15]. INS accumulates drift over time, while dead reckoning suffers from bias and integration errors. Acoustic positioning systems, including Long Baseline (LBL) and Ultra-Short Baseline (USBL) methods, provide absolute fixes but are constrained by propagation delays, multipath interference, and the need for pre-deployed infrastructure. These uncertainties complicate formation control and coordinated behaviours, as individual agents may hold inconsistent estimates of position relative to their neighbours.

Communication represents another fundamental limitation. Underwater environments preclude the use of conventional Radio Frequency channels. Instead, communication relies primarily on acoustic, optical, or low-frequency electromagnetic modalities, each with trade-offs in range, bandwidth, and reliability. For example, Awan et al. reviewed system-level constraints and networking challenges in underwater wireless systems [16], Saeed et al. surveyed underwater optical wireless communications and localisation [17], and Alahmad et al. experimentally evaluated underwater RF/EM transmission for AUV applications [18]. Acoustic links offer long range but suffer from low data rates, latency, and ambient noise; optical communication enables high throughput over short distances but is sensitive to turbidity; and electromagnetic transmission is restricted to a few metres due to rapid attenuation in seawater. These limitations necessitate swarm control architectures that tolerate sparse, delayed, and intermittent connectivity.

Environmental variability further compounds these challenges. Variations in temperature, salinity, and current affect vehicle dynamics, sensing performance, and communication range. High pressures at depth require robust pressure-rated housings, while saltwater corrosion demands protective materials and coatings. Energy management remains a persistent constraint, as finite battery capacity limits endurance and dictates careful trade-offs among propulsion, sensing, computation, and communication.

Collectively, the absence of global positioning, constrained communication, environmental uncertainty, and limited energy define a complex design space for marine swarm robotics. These factors motivate decentralised, adaptive, and energy-aware coordination approaches capable of operating reliably with partial and delayed information.

2.2. Principles of Swarm Intelligence

Swarm intelligence examines how complex collective behaviours emerge from local interactions among many simple agents [6]. Natural examples include fish schools, bird flocks, and insect colonies, where individuals follow local behavioural rules based on neighbour perception and environmental cues [5]. Without any central controller, such collectives achieve tasks including exploration, foraging, migration, and defence.

Key principles of swarm intelligence include decentralisation, scalability, robustness, and emergence. In decentralised systems, each agent acts autonomously based on local information, reducing dependency on global knowledge and central coordination. Scalability arises when identical rules can govern both small and large groups without structural modification. Robustness stems from redundancy, where loss or malfunction of individual agents has minimal effect on collective performance. Emergence describes the spontaneous formation of complex, adaptive behaviours from simple rules of interaction.

In robotic applications, these principles translate into algorithms that govern local perception, control, and decision-making. Agents modify their movements and roles according to the states of nearby neighbours, producing emergent phenomena such as formation control, aggregation, and exploration. Examples include robotic fish that exploit hydrodynamic interactions to conserve energy [19], decentralised binary decision-making strategies that enable collective motion through local perception [20], and pheromone-inspired coordination mechanisms for distributed exploration [21,22].

These properties are particularly suited to underwater environments. Communication limitations naturally encourage local interactions, while uncertain conditions require adaptive, fault-tolerant behaviours. Swarm intelligence thus provides the conceptual foundation for designing cooperative Marine Robotic Systems that can function effectively with minimal communication and incomplete environmental awareness.

2.3. Relevance of Bio-Inspired Design in Marine Systems

Bio-inspired design offers a powerful framework for developing underwater swarm robotics, as marine organisms have evolved to operate efficiently under the same constraints that challenge robotic systems: restricted communication, positional uncertainty, and limited energy availability [4]. By emulating natural coordination and sensing strategies, robotic systems can achieve resilient, low-energy, and adaptive behaviours suited to underwater conditions.

Marine organisms exemplify efficient coordination mechanisms that require minimal communication. Fish schools maintain cohesive formations through local alignment and spacing rather than global control [8], while hydrodynamic coupling between individuals can reduce overall energy expenditure by more than 50% compared with solitary swimming [19]. These naturally evolved mechanisms demonstrate how energy-efficient cooperation and adaptive formation control can emerge without continuous data exchange and absolute positioning.

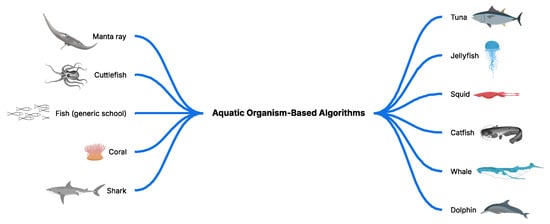

Several marine-specific bio-inspired algorithms capture such biological strategies in computational form. The Artificial Fish Swarm Algorithm (AFSA) models visual perception, swarming, and following behaviours [23]; the Whale Optimisation Algorithm (WOA) draws from bubble-net hunting patterns of humpback whales [24]; the Coral Reef Optimisation (CRO) algorithm simulates coral reproduction and depredation dynamics [25]; and the Marine Predators Algorithm (MPA) represents predator–prey interactions across distinct velocity phases [4]. These algorithms are inherently compatible with underwater constraints, requiring limited communication, operating effectively under positional uncertainty, and promoting energy-efficient exploration and cooperation. Recent developments have further addressed specific underwater challenges, such as hydrodynamic constraints and irreversible settlement behaviours in strong current environments [26]. A wide variety of nature-inspired optimisation algorithms has been proposed [27]. Figure 3 shows several aquatic organism-based algorithms inspired by marine species.

Figure 3.

Aquatic organisms that underpin many bio-inspired optimisation algorithms, illustrating representative marine species used as the biological basis for these methods.

Beyond optimisation-based bio-inspired algorithms, neural-inspired control paradigms offer complementary approaches. Spinal neural system models have been applied to heterogeneous AUV cooperative hunting [28], while bio-inspired neural networks have enabled decision-making and motor control in differential robots [29]. Reinforcement learning approaches, such as neural network-based Q-learning for path planning in unknown environments [30], further extend the scope of bio-inspired methods to learning-based coordination.

Bio-inspired strategies have been applied to improve communication topologies, formation control, task allocation, and environmental interaction within underwater swarm robotics. They promote robustness, scalability, and adaptability, qualities essential for long-duration missions in unpredictable marine environments [31]. Despite growing adoption, systematic guidance for integrating these algorithms with communication protocols and hardware architectures remains limited. This review addresses that gap by synthesising bio-inspired coordination, communication, and design approaches into a coherent framework for future intelligent marine robotic systems.

3. Bio-Inspired Coordination Mechanisms

Bio-inspired coordination mechanisms form the core of underwater swarm robotics, enabling multiple autonomous agents to achieve collective objectives through local interactions and distributed decision-making. This section examines the principal coordination strategies derived from marine biological systems. It focuses on how local interactions enable decentralised control, how formation control supports collective motion, how task allocation distributes responsibilities, and how collective decision-making emerges from individual behaviours. Throughout, the emphasis remains on how biologically inspired rules translate into concrete coordination algorithms suitable for communication-limited, energy-constrained underwater swarms.

3.1. Local Interaction and Decentralised Control

Decentralised control represents a fundamental principle of swarm robotics, where coordination emerges from local interactions rather than centralised command. This approach is particularly suited to underwater environments, where communication constraints and intermittent connectivity make global coordination impractical.

Local interaction mechanisms enable agents to coordinate through simple behavioural rules based on neighbour perception and environmental sensing. In biological swarms, individual organisms respond to nearby neighbours’ positions and velocities, producing emergent collective patterns without any central controller [5]. Robotic swarms replicate these mechanisms by implementing local control policies that govern perception, movement, and decision-making, allowing distributed coordination that scales efficiently with swarm size.

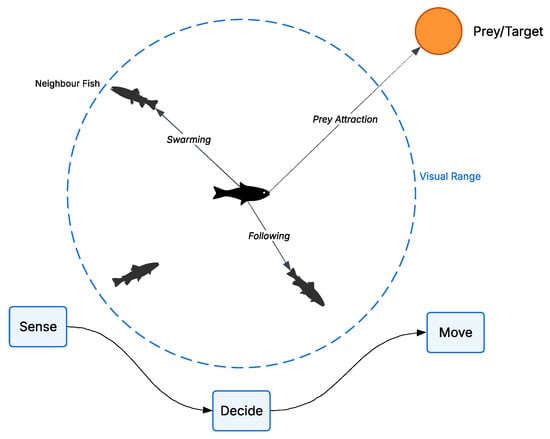

The Artificial Fish Swarm Algorithm (AFSA) exemplifies local interaction through its visual perception model, where artificial fish respond to neighbours within a defined visual range. Adeli provided an early review of AFSA methods and applications [32], Pourpanah et al. summarised more recent AFSA variants and application directions [33], and Peraza et al. presented an AFSA-based approach in a computational-intelligence setting [34]. Each agent adjusts its position based on local stimuli such as prey attraction, swarming, and following behaviours. This mechanism enables coordination through environmental sensing rather than explicit message exchange, making AFSA highly compatible with low-bandwidth acoustic communication environments.

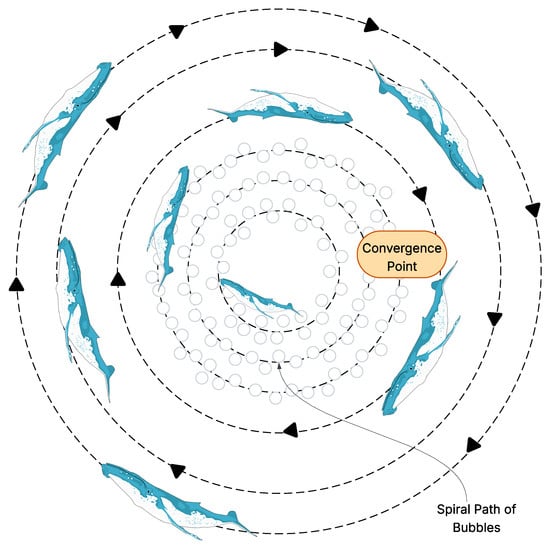

Figure 4 presents a conceptual illustration of the AFSA visual perception and behaviour selection mechanism, showing how artificial fish perceive nearby individuals and environmental stimuli to dynamically select between prey attraction, swarming, and following behaviours.

Figure 4.

Visual perception and behaviour selection in the Artificial Fish Swarm Algorithm (AFSA). The central artificial fish perceives neighbouring agents and environmental stimuli within its visual range and dynamically selects between prey attraction, swarming, and following behaviours based on local sensory input. Coordination emerges from environmental perception rather than direct communication.

Decentralised control architectures eliminate single points of failure and enhance resilience. Adaptive coordination strategies allow vehicles to adjust parameters in response to varying communication quality, enabling continuity despite packet loss and latency. Minimalistic binary coordination strategies also exemplify effective decentralisation: agents make binary rotation decisions (for example, left or right) based solely on neighbour headings [20]. Such strategies achieve coherent collective motion through local perception, requiring no explicit synchronisation or global positioning.

Local interaction mechanisms thus provide robustness, scalability, and adaptability. As swarm size increases, the same local rules govern behaviour without structural modification, allowing the swarm to maintain coordination performance across a wide range of operational scales.

3.2. Formation Control and Collective Motion

Formation control enables underwater swarms to maintain desired spatial configurations while navigating dynamic marine environments. Bio-inspired formation control strategies draw directly from natural collective behaviours, particularly those observed in fish schools, where individuals sustain relative positions through local alignment and spacing [8].

Fish schooling provides a natural template for energy-efficient collective motion. Experiments demonstrate that fish reduce energy expenditure per tail beat by more than 50% compared with solitary individuals, benefiting from hydrodynamic interactions [19]. These mechanisms illustrate how coordinated motion can emerge without continuous data exchange and precise global positioning, providing models for underwater swarm formation control.

WOA models the cooperative bubble-net feeding behaviour of humpback whales, in which individuals encircle and herd prey through coordinated movement patterns [24,35]. This strategy underpins the algorithm’s encircling mechanism, representing agents that maintain adaptive relative positions within the search space, while the spiral bubble-net model guides convergence towards promising regions, analogous to coordinated manoeuvring observed in nature. Rana et al. [36] further analysed these dynamics, highlighting the balance between exploration and exploitation achieved through such collective strategies. The algorithmic abstraction of this behaviour is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Bubble-net feeding behaviour of humpback whales illustrating the search mechanism of the Whale Optimisation Algorithm (WOA).

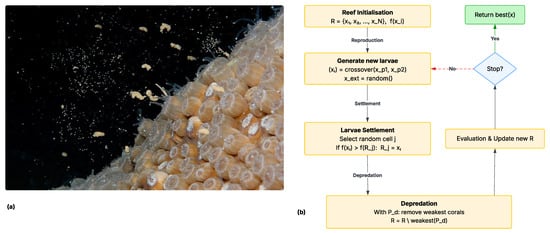

CRO provides an alternative bio-inspired optimisation framework grounded in the competitive dynamics of coral reefs, where individual corals occupy spatial positions and interact through spawning and larvae settlement [37]. The algorithm models the ecological processes of reproduction, settlement, and depredation on a discretised reef grid, balancing exploration and exploitation through spatial competition. This distributed mechanism promotes redundancy and resilience against individual failure, enabling adaptive population evolution over time. The biological inspiration and algorithmic process of CRO are illustrated in Figure 6. Figure 6b summarises the CRO iteration on a discretised reef, where denotes reef cells storing candidate solutions and is the objective (fitness) to be maximised. New larvae are generated from parent solutions (e.g., via crossover and random injection for exploration), then a larva attempts to settle into a randomly chosen cell j. If it improves the resident solution, i.e., , it replaces it, implementing local competition for space. Periodically, depredation removes a fraction of the weakest corals with probability , preventing stagnation and promoting exploration; the loop repeats until a stopping criterion is met and the best coral is returned. Minimalistic formation-control approaches based on binary interactions and local decision rules likewise demonstrate cohesive group motion under limited communication: each AUV responds to neighbour headings with simple binary decisions (e.g., rotate left or right by a fixed angle), enabling emergent coherent collective motion without predefined global targets [20].

Figure 6.

Coral Reef Optimisation (CRO) algorithm: (a) coral spawning illustrating the biological inspiration; (b) flowchart of the CRO process showing reef initialisation, larvae generation and settlement, evaluation, and depredation steps.

Underwater formation control must accommodate GPS denial and positional uncertainty. Algorithms based on relative positioning naturally address these challenges, mirroring biological systems that rely on neighbour-relative cues rather than absolute global references. Consequently, relative localisation and neighbour-awareness form the foundation of practical marine swarm formation strategies.

3.3. Task Allocation and Role Differentiation

Task allocation distributes mission responsibilities among swarm members to maximise efficiency and exploit heterogeneity in agent capability. Bio-inspired task allocation draws from natural systems in which individuals assume roles according to local context and resource availability.

The Coral Reef Optimisation algorithm embodies adaptive task allocation through competitive reef dynamics, where corals vie for space based on fitness values [25,37]. Its depredation mechanism removes weaker solutions, creating natural role differentiation as stronger agents assume more critical responsibilities while others are replaced and reassigned. This dynamic reassignment provides inherent fault tolerance and adaptability to changing conditions.

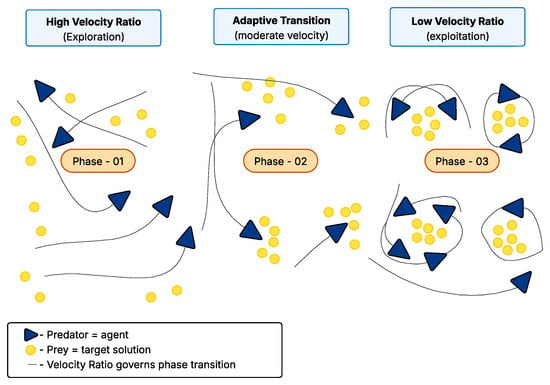

The Marine Predators Algorithm (MPA) models cooperative predator–prey interactions governed by relative velocity ratios [38,39]. Agents alternate between exploration and exploitation phases, acting as explorers at high-velocity ratios and as refiners at low-velocity ratios. This phase-based transition enables adaptive task allocation that responds dynamically to mission progress and environmental complexity. Improved modelling of velocity ratio adaptation and foraging dynamics has further enhanced the algorithm’s search balance [40]. The overall three-phase optimisation process is illustrated conceptually in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Conceptual illustration of the Marine Predators Algorithm (MPA) showing the three-phase optimisation process governed by predator–prey velocity ratios. The schematic depicts the transition from high-velocity exploration to low-velocity exploitation, capturing the algorithm’s adaptive search dynamics.

AFSA supports task allocation through local perception, where each agent selects targets based on local environmental information rather than central assignment [23]. This method aligns well with underwater conditions, allowing distributed agents to self-select tasks based on sensory input and spatial proximity.

Role differentiation can also be extended to heterogeneous swarms, where agents with different sensing and mobility capabilities assume complementary functions. Behaviour-driven frameworks enable dynamic alliance formation based on task needs and agent attributes [41]. Such frameworks integrate global mission objectives with local autonomy, ensuring coordination even under uncertainty and communication delays.

3.4. Collective Decision-Making and Learning

Collective decision-making allows underwater swarms to achieve consensus and coordinated action through local interaction and distributed information exchange. Bio-inspired collective decisions emerge without explicit global control, relying instead on gradual convergence of local preferences.

The Marine Predators Algorithm demonstrates distributed decision-making through its three-phase optimisation process, where agents collectively transition between exploration and exploitation [38]. The algorithm’s dynamics enable agents to identify promising areas cooperatively and converge towards shared targets. Similarly, the Whale Optimisation Algorithm achieves collective consensus as agents synchronise their movement towards the globally best position through its encircling behaviour [35,36].

Learning mechanisms further enhance collective coordination by enabling adaptation based on environmental feedback. While most marine-specific bio-inspired algorithms employ fixed behavioural rules, hybrid approaches that integrate reinforcement learning and adaptive parameter tuning could yield improved responsiveness and autonomy [4]. Neural network-based Q-learning has been demonstrated for robot path planning in unknown environments [30], and spinal neural system approaches have enabled coordinated hunting behaviours among heterogeneous AUVs [28]. Recent work on neuromodulation for motor control further illustrates the potential of bio-inspired neural architectures for robotic decision-making [29]. These adaptive extensions would allow swarms to evolve coordination strategies in response to environmental variability, communication degradation, and mission progress.

Underwater collective decision-making must function under delayed, limited communication. Algorithms that propagate decisions through local neighbour interactions, rather than global synchronisation, offer a robust solution. Such distributed learning and consensus mechanisms represent a key direction for improving the adaptability of future marine robotic swarms.

3.5. Hybrid Coordination Approaches

Recent research has explored hybrid coordination algorithms that integrate multiple algorithmic principles to overcome limitations of single-paradigm systems. Table 1 summarises representative hybrid methods applied in underwater swarm robotics, combining swarm intelligence, graph-based reasoning, and control-theoretic approaches. A comprehensive comparative evaluation of marine-specific algorithms is presented in Section 6.

Table 1.

Recent hybrid algorithms applied in underwater swarm robotics.

4. Underwater Communication Strategies

Underwater communication systems form the backbone of swarm coordination, enabling information exchange among autonomous agents operating in complex and variable marine environments. Unlike terrestrial or aerial systems, underwater communication must contend with physical constraints that severely limit bandwidth, range, and reliability. This section reviews the principal communication modalities used in Marine Robotic Systems, examines network topologies that support swarm connectivity, explores bio-inspired communication protocols, and discusses mechanisms for delay tolerance, fault handling, and synchronisation. These communication layers provide the physical substrate and performance envelope within which bio-inspired coordination and signalling schemes must be implemented in practice.

4.1. Acoustic, Optical, and Hybrid Communication Modalities

Underwater communication primarily employs three physical modalities (acoustic, optical, and electromagnetic), each with distinct performance characteristics governed by signal propagation in seawater. Acoustic communication remains the dominant technology due to its long range and broad applicability for Marine Robotic Systems [48]. Acoustic waves propagate at approximately 1500 m/s, enabling links from tens of metres to several kilometres, but with limited bandwidth and strong susceptibility to multipath, Doppler, and environmental noise [49]. Table 2 summarises the comparative characteristics of these technologies; for electromagnetic links in water, propagation speed is approximated as with representative seawater [50]. Note that both optical and RF are electromagnetic communications operating at different frequency ranges; optical uses blue–green wavelengths (450–550 nm), while RF uses lower frequencies (kHz–GHz).

Table 2.

Comparative characteristics of underwater communication technologies.

Recent developments in underwater wireless communication have expanded AUV swarm capabilities, but the aquatic environment still imposes severe constraints. Acoustic communication is the dominant long-range modality for AUV swarms [48], enabling essential functions like localisation and information sharing. However, acoustic channels are limited to roughly 10 kbaud data rates [49] and suffer from high latency and noise, making coordination challenging in large swarms [55].

As a complement to acoustics, optical and RF methods are being explored. Optical systems can achieve extremely high data rates (exceeding 1 Gbit/s in laboratory conditions) but require strict line-of-sight and are quickly attenuated by water [17,49]. Tests show that clear ocean water allows ranges from 60 to 70 m, while turbid water reduces it below 10 m. Optical links consume far less energy per bit than acoustics, making them attractive for short-range high-data-rate tasks such as docking or sensor payload transmission. RF communication in water is generally confined to very shallow or short-range use due to seawater conductivity, so RF is typically limited to intra-vehicle links or surface-to-underwater communication [49].

Magnetic Induction (MI) communication offers another short-range alternative, using time-varying magnetic fields with negligible propagation delay and stable channel characteristics [56]. Although limited to short distances (under 2 m), MI channels are promising for local coordination due to their low sensitivity to water properties.

To balance these trade-offs, hybrid acoustic–optical–MI networks have been proposed [49,56]. In such multi-modal schemes, long-range acoustic links maintain connectivity while optical or MI links provide high-speed local exchange. Adaptive switching protocols select appropriate channels based on environmental conditions and data priority [51]. Control data requiring robustness may be routed acoustically or magnetically, while sensor data streams can exploit optical channels when available. These architectures aim to deliver resilience and flexibility for mission-critical swarm behaviour. For bio-inspired underwater swarms, these physical communication modalities define the bandwidth, latency, and range constraints under which biologically inspired coordination algorithms (such as AFSA, WOA, CRO, and MPA) and signalling schemes must operate, directly shaping feasible neighbourhood sizes, update rates, and degrees of decentralisation.

In the classification framework introduced in Section 6, these choices of physical communication modality and hybrid architecture primarily influence the communication-dependency and energy-efficiency dimensions by constraining how often and how far agents can exchange information.

4.2. Network Topologies for Swarm Connectivity

Underwater swarm networks must operate under high latency, intermittent connectivity, and dynamic node positioning. Conventional terrestrial networking paradigms are not directly applicable due to the slow speed of sound and time-varying link quality [55,57]. Adaptive and opportunistic routing techniques have thus been developed for underwater conditions.

Opportunistic routing protocols utilise the broadcast nature of acoustic communication, allowing multiple candidate forwarders to compete and cooperate in relaying messages [49]. This avoids fixed paths and supports dynamic adaptation. Geographic routing methods transmit data towards destination coordinates, assuming nodes have relative positioning capabilities. In three-dimensional underwater environments, depth-based routing can be effective, with vertical position as the primary metric [58]. Adaptive multi-zone protocols integrate geographic and depth-aware strategies, selecting routes based on node density and link quality.

TDMA (Time-Division Multiple Access) schemes support collision-free communication by allocating time slots for each node. Despite the challenges of long propagation delays and clock drift, TDMA has been successfully implemented using guard intervals and adaptive synchronisation to maintain reliable timing, as demonstrated in field deployments [48].

Swarm topologies vary depending on mission goals. Linear chains are effective for pipeline inspection or relay tasks, while clustered or mesh topologies distribute connectivity for broader coverage. Decentralised networks allow robustness against node failure by distributing control and routing responsibilities, while hybrid schemes combine hierarchical control and local autonomy [55]. The optimal topology is mission-specific and must accommodate density, mobility, and environmental disruption, emphasising the importance of adaptive communication architectures. From a bio-inspired perspective, these network topologies underpin how local interaction rules are realised at system level, constraining how quickly bio-inspired behaviours such as schooling, foraging, and predator–prey dynamics can propagate through the swarm under realistic acoustic and optical connectivity.

4.3. Bio-Inspired Communication Protocols

Bio-inspired communication protocols take cues from nature, where organisms coordinate efficiently under severe sensory and communication limitations. Such protocols are inherently suited to underwater conditions, as they minimise bandwidth use while maintaining functional coordination [4,59].

Pheromone-inspired strategies enable indirect communication through persistent environmental markers, analogous to chemical trails in ant colonies [21,22]. Underwater, virtual markers and temporary data gradients can represent shared information, allowing agents to influence each other’s trajectories without direct message exchange. This indirect form of communication supports cooperative exploration and foraging while conserving bandwidth.

Acoustic mimicry provides another biologically inspired technique. By emulating the spectral patterns of marine mammal vocalisations, systems can achieve covert and environmentally integrated communication [59]. Such methods may reduce interference and detection while blending with natural acoustic backgrounds, although they trade efficiency for concealment.

Collective sensing constitutes an implicit communication approach where agents infer swarm state from neighbour movement and environmental cues rather than explicit messages. For example, AFSA’s visual perception model enables coordination through local observation of neighbours, analogous to visual alignment in fish schools [33]. These methods reduce dependence on message exchange and improve resilience to packet loss.

Bio-inspired protocols emphasise efficiency and robustness. When integrated with swarm coordination algorithms, they enable communication-constrained systems to maintain coherent group behaviour using minimal shared information, an essential property for scalable underwater operations.

4.4. Delay Tolerance, Fault Handling, and Synchronisation

The underwater communication channel imposes significant propagation delays, intermittent connectivity, and link unreliability, making delay-tolerant networking essential for swarm operation [49]. Rather than requiring continuous end-to-end connections, Delay-Tolerant Networks (DTNs) allow nodes to store, carry, and forward information when connectivity becomes available. These mechanisms enable effective cooperation even under sporadic contact conditions.

Acoustic propagation delays, often several seconds over kilometre-scale ranges, disrupt real-time coordination and synchronisation [48]. Delay-tolerant coordination leverages prediction and local autonomy to maintain functionality despite outdated information. Algorithms such as WOA and MPA, which depend primarily on local states and global trends rather than direct communication, naturally accommodate these delays [35,38].

Fault handling ensures continued swarm function despite individual agent and link failures. Decentralised designs inherently improve fault tolerance, as no single unit is mission-critical. In CRO-inspired frameworks, competitive depredation mechanisms naturally replace failed and underperforming agents with new participants [37]. Redundant routing paths and adaptive link selection further enhance reliability.

Synchronisation remains a challenge due to clock drift and long propagation delays. TDMA-based coordination schemes require guard intervals and periodic re-synchronisation. Adaptive synchronisation adjusts transmission timing based on measured delay, while asynchronous coordination eliminates dependency on shared time references by relying on local interaction cues and environmental feedback. These strategies collectively enable stable swarm coordination under uncertain temporal conditions.

Environmental variability compounds these challenges by altering sound-speed profiles, attenuation, and noise levels. Adaptive modulation, dynamic power control, and predictive environment modelling can mitigate performance degradation by preemptively adjusting communication parameters to maintain connectivity and throughput.

4.5. Cross-Layer Optimisation for Cooperative Swarms

Cross-layer optimisation integrates communication, control, and energy management to improve overall swarm performance rather than optimising each subsystem in isolation [48,60]. This holistic approach is particularly valuable in underwater robotics, where communication cost and reliability strongly influence system design and coordination strategies.

Communication is often the most energy-intensive process in an underwater robot, with transmission power dominating total energy consumption [60]. Cross-layer optimisation therefore focuses on balancing communication reliability with energy efficiency. Algorithms such as WOA and MPA, characterised by low communication dependency, are naturally suited to energy-aware operation [35,38]. AFSA and CRO, which involve frequent neighbour interactions, require additional energy management strategies for long-duration missions [33,37].

Adaptive physical-layer techniques adjust OFDM subcarrier allocation and modulation parameters based on environment feedback to optimise BER and energy use [48]. These adjustments enable swarms to maintain data integrity while reducing redundant transmission energy costs. Energy-efficient communication protocols can reduce transmission power from approximately 30 to 50% through adaptive modulation and dynamic power control, directly extending mission endurance in energy-limited swarm deployments [48].

Hybrid communication architectures further enhance cross-layer optimisation. By switching intelligently between acoustic, optical, and MI modalities, systems can allocate bandwidth and energy according to task urgency and environmental suitability [56]. Low-rate, high-reliability control data may use acoustic and magnetic channels, while high-volume sensing data employ optical links where visibility allows. This dynamic selection minimises energy consumption while sustaining mission performance.

Cross-layer integration creates synergy between communication protocols and coordination algorithms. Algorithms that exploit local sensing and indirect communication reduce network traffic, while communication strategies that support such decentralised coordination reinforce autonomy and robustness. Hardware platforms with multimodal communication interfaces enable these adaptive behaviours, allowing swarms to reconfigure communication and control strategies dynamically in response to mission and environmental demands.

Cross-layer optimisation thus represents a critical enabler of practical underwater swarm robotics. By jointly considering communication constraints, algorithmic design, and hardware capabilities, it is possible to achieve efficient, resilient, and scalable cooperation that meets mission objectives within real-world limitations.

5. System Design and Implementation

Effective underwater swarm robotics requires careful integration of hardware platforms, sensor systems, energy management, and software architectures to enable reliable operation in challenging marine environments. This section examines the principal design considerations for implementing underwater swarm systems, from hardware architectures and sensor integration to energy optimisation and experimental validation. The discussion covers both theoretical design principles and practical implementation experiences from deployed systems, providing insight into the trade-offs and constraints that shape real-world underwater swarm deployments. In the context of this review, these design choices are interpreted through a bio-inspired lens, highlighting how platform, sensing, and power decisions support or constrain biologically motivated coordination and communication strategies.

5.1. Hardware Architectures for Underwater Swarms

Underwater swarm platforms must balance trade-offs among vehicle size, endurance, communication capability, autonomy, and cost. Two benchmark implementations that have validated decentralised coordination, TDMA-based scheduling, and adaptive physical-layer strategies in real underwater environments are the COMET and NEMOSENS projects [48]. The COMET AUV (approximately 2 m in length, 40 kg) provides extended operational duration (20 h) and deep-sea capacity (300 m), featuring high-endurance acoustic communication and INS/DVL navigation systems. However, its larger size limits scalability for large swarm formations. In contrast, NemoSens (0.9 m, 9 kg) is a compact swarm-ready platform with moderate endurance (10 h), flexible modularity for communication and navigation, and Linux-based modular control. Both platforms have demonstrated effective decentralised coordination where each AUV maintains network awareness and communication order without central nodes, with TDMA successfully implemented using guard intervals and adaptive synchronisation to maintain reliable timing despite long propagation delays and clock drift. Adaptive physical-layer techniques demonstrated in these projects adjust OFDM subcarrier allocation and modulation parameters based on environment feedback to optimise BER and energy use, enabling swarms to maintain data integrity while reducing redundant transmission energy costs. These projects followed a progressive validation pipeline from simulation through laboratory testing to field verification, providing critical empirical validation of swarm coordination strategies.

Explicitly designed for swarm coordination, MONSUN II offers a small (60 cm), low-cost (4.2 kg) architecture integrating six thrusters for 5-DOF mobility, onboard sensors (IMU, depth, temperature, IR), and modular I2C/SPI expansion ports for scalable integration [61]. Its open hardware design simplifies maintenance and supports plug-and-play experimentation. These architectures prioritise robustness and rapid deployment in shallow environments.

Bio-inspired miniature designs such as Bluebot enable vision-based schooling behaviour using LED-based communication and fin-like actuation for precise 3D motion in confined water columns [62]. Platforms like M-AUE take advantage of buoyancy-driven drifting with vertical mobility for submesoscale ocean dynamics tracking, providing high spatial resolution data via collective deployment [63]. Open-source MURs such as the one proposed by Mayberry et al. [64] incorporate 5-DOF propulsion, multiple cameras, and ROS-native controllers for rapid experimentation.

Table 3 compares representative swarm-capable underwater robots based on structural and functional parameters.

Table 3.

Representative underwater swarm-capable robotic platforms and their characteristics.

Distributed onboard compute is central to swarm behaviour, enabling decentralised formation control and adaptive mission execution. For instance, swarm platforms have demonstrated effective formation behaviour with each AUV running an ROS-based controller on Raspberry Pi 4 boards [65]. Architectures emphasise modular sensor integration, hot-swappable interfaces, and energy-efficient propulsion. Communication systems range from acoustic modems for deep water to WiFi and optical signalling in confined or shallow domains [66].

Together, these hardware architectures span a design spectrum ranging from robust long-endurance AUVs to bio-inspired miniature swarming agents, offering a broad toolkit for scalable underwater multi-agent systems. For bio-inspired underwater swarms, selecting along this spectrum determines how closely physical platforms can emulate the sensing, manoeuvrability, and interaction scales assumed by biological analogues such as fish schools or drifting organisms, and, thus, how faithfully bio-inspired coordination rules can be implemented in practice.

These platform decisions most directly affect swarm scalability and environmental adaptability, setting practical bounds on the number of vehicles that can be deployed and the range of ocean conditions under which bio-inspired behaviours can be reliably sustained.

5.2. Sensor Integration and Environmental Perception

Sensor integration provides the perceptual foundation for navigation, obstacle avoidance, and environmental monitoring in underwater swarms. Acoustic sensors such as sonar deliver long-range detection unaffected by turbidity, while optical sensors offer high-resolution imaging but are constrained by light attenuation and scattering [67,68].

Sensor fusion frameworks combine acoustic, optical, magnetic, and bio-inspired modalities to improve reliability in heterogeneous conditions [67]. Navigation under GPS denial relies on INS, dead reckoning, and acoustic localisation systems [13]. INS-DVL integration remains a standard method for maintaining positional accuracy between acoustic updates.

Environmental perception also supports implicit coordination through local sensing. AFSA’s visual perception model exemplifies this approach, where agents infer collective behaviour by observing neighbours’ movement patterns [33]. This perception-based coordination reduces message exchange, which is particularly beneficial under acoustic bandwidth constraints.

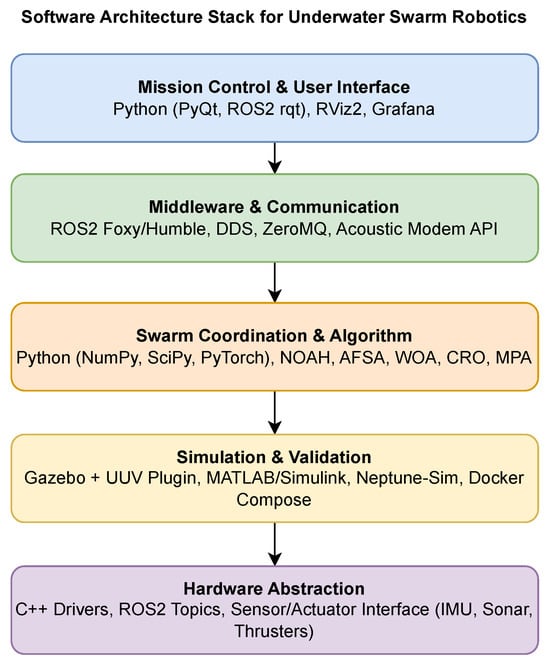

Integrating communication hardware requires balancing range, bandwidth, and power consumption. Acoustic modems provide long-range links with high latency; optical systems deliver high-speed, short-range data exchange; and hybrid configurations combine both for adaptive performance [48,49]. Payload capacity limits dictate sensor selection, necessitating modular architectures that allow mission-specific reconfiguration while maintaining overall hydrodynamic efficiency. Figure 8 illustrates the software architecture for underwater swarm robotics systems, showing the integration of distributed control, communication protocols, sensor fusion, and mission planning modules.

Figure 8.

Software architecture for underwater swarm robotics systems, illustrating the integration of distributed control, communication protocols, sensor fusion, and mission planning modules within a cohesive multi-agent platform architecture.

5.3. Energy Management and Power Optimisation

Energy management defines operational duration and mission feasibility for underwater swarms [69,70]. Communication dominates total energy use, requiring optimisation of transmission power, duty cycling, and coordination frequency [48,60].

Lithium-ion batteries remain the preferred energy source, balancing density, power output, and safety. Field deployments have demonstrated operational endurance ranging from 10 to 20 h under typical operational loads [48]. Emerging hydrogen fuel cell systems and energy harvesting from ocean currents represent potential extensions to future endurance.

Biological collectives inspire energy-efficient coordination. Bio-inspired algorithms such as WOA and MPA minimise communication overhead and motion redundancy to lower energy demand [35,38]. AFSA and CRO require tighter energy budgeting due to neighbourhood evaluation processes [33,37]. Hydrodynamic interactions and ocean current direction strongly influence power requirements during obstacle avoidance manoeuvres, underscoring the importance of strategic trajectory planning [71].

Propulsion design has a significant influence on energy use. Conventional thrusters are reliable but less efficient at low speeds; bio-inspired mechanisms such as undulating fins and oscillating foils offer enhanced efficiency and stealth [67]. Recent advances in miniature underwater robots have explored diverse actuation methods including motors, magnetic field actuation, piezoelectric actuators, and soft materials (e.g., shape memory alloys, dielectric elastomer actuators, ionic polymer-metal composites), each offering distinct trade-offs in power consumption, response speed, and motion flexibility [72]. These actuation technologies enable various locomotion modes such as fish-inspired swimming, jetting, paddling, and crawling, providing flexibility for different swarm applications and environmental conditions [72]. Energy-aware path planning further improves endurance by exploiting ocean currents for passive drift and current-assisted travel [71]. Empirical studies indicate that energy-aware path planning can reduce propulsion energy consumption by approximately 20 to 30% through strategic current exploitation and trajectory optimisation [71]. Cross-layer power management, which coordinates propulsion, sensing, and communication demands, ensures optimal use of limited energy reserves throughout a mission.

Within the classification framework, these energy management strategies directly shape the energy-efficiency dimension and indirectly support scalability by determining how mission duration and swarm size can be traded off against communication and propulsion costs.

5.4. Simulation and Experimental Platforms

Simulation and testing environments enable validation of algorithms, communication models, and control architectures before costly field trials. Effective underwater simulation must capture hydrodynamic resistance, buoyancy variation, acoustic propagation delay, and environmental noise [73,74]. Realistic three-dimensional modelling enhances predictive fidelity for formation control and coordination algorithms [31].

Robotics Software Frameworks (RSFs) and Multi-Agent System Frameworks (MASFs) provide essential middleware for distributed simulation and control [75]. These platforms abstract hardware dependencies, support inter-agent communication, and enable scalable swarm testing. Middleware must manage limited bandwidth, latency, and service discovery within dynamic underwater topologies [49]. In this review, the focus remains on these functional capabilities rather than on specific software stacks, to avoid unnecessary architectural detail and potential confusion for readers primarily interested in bio-inspired coordination, communication, and system design.

Validation through simulation-experiment integration is critical. A progressive validation pipeline from simulation through laboratory testing to field verification has been demonstrated in successful deployments [48]. Laboratory environments (tank facilities, acoustic testbeds, and optical calibration setups) offer controlled conditions to evaluate sensor reliability and subsystem performance before open-water deployment. Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL) simulation bridges software and hardware domains, providing realistic testing of sensors, communications, and control algorithms under repeatable conditions [67]. This multi-stage validation reduces development risk and improves system robustness. Table 4 presents a progressive validation framework for underwater swarm robotics testing, illustrating the structured pathway from simulation through HIL testing to controlled field trials. These simulation and validation frameworks provide the testbed in which bio-inspired swarm algorithms and communication protocols can be exercised under controlled yet realistic conditions, enabling systematic assessment of how closely biologically motivated behaviours translate into reliable underwater performance.

Table 4.

Progressive validation framework for underwater swarm robotics testing. The framework illustrates a structured pathway from simulation through Hardware-in-the-Loop testing to controlled field trials.

5.5. Emerging Prototypes and Field Deployments

Despite increasing simulation maturity, few swarm systems have reached sustained field operation [7]. Benchmark implementations have validated decentralised coordination, TDMA-based scheduling, and adaptive physical-layer strategies in real underwater environments [48].

Field testing requires strict operational and safety protocols, encompassing environmental monitoring (temperature, salinity, turbidity, current, and noise), real-time telemetry, and recovery systems. Mission evaluation metrics include communication reliability, energy consumption, localisation accuracy, and task success rate. Safety procedures cover emergency recovery, fail-safe shutdown, and redundancy protocols for lost communication links.

Operational scenarios demonstrate practical relevance: coral reef monitoring, sub-sea pipeline inspection, search and rescue, and deep-sea exploration [4,23]. Each scenario tests algorithms under distinct environmental constraints, from shallow high-turbidity zones to high-pressure deep-sea conditions. Incremental field validation (simulation to laboratory to real environment) enables systematic fault isolation and progressive risk reduction [4,48].

5.6. Metrics for Evaluating Swarm Performance

Evaluating underwater swarm performance requires multidimensional metrics covering coordination, communication, energy efficiency, robustness, and scalability. Coordination is typically assessed through velocity correlation, nearest-neighbour distance, and coverage yield. Navigation accuracy is often measured using cross-track error and formation deviation [76]. Communication performance is quantified by Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR), end-to-end latency, and throughput. For instance, the EVA framework achieved over 96% PDR in large-scale UWSN simulations [77], while the ILAF protocol demonstrated 99% delivery reliability [78]. AQUA-GLOMO simulations recorded control delays between 0.1–0.54 s [79].

Energy metrics such as joules per metre and energy-to-completion ratios indicate mission efficiency. Hierarchical reinforcement learning-based navigation reduced formation error to below 0.7 m [76], and DSUA-based cooperative control reduced energy use by 12.6% [80]. Fault-tolerant control schemes maintain swarm coordination with under 15% performance degradation [81]. Scalability is validated by maintaining over 80% baseline performance at 400+ nodes [77]. Representative benchmark thresholds commonly reported in the literature and used for underwater swarm validation are summarised in Table 5.

Table 5.

Representative performance benchmarks for underwater swarm validation.

6. Classification and Synthesis Framework

The preceding sections have examined bio-inspired coordination mechanisms, communication strategies, and system design considerations as distinct domains. However, effective underwater swarm robotics requires systematic integration of these components to address the complex interdependencies that shape real-world system performance. This section presents a multi-dimensional classification framework that synthesises findings across algorithms, communication, and hardware domains, enabling evaluation and selection of coordination strategies based on mission requirements and operational constraints.

6.1. Dimensions of Classification: Communication, Adaptability, Energy, and Scalability

Effective classification of bio-inspired algorithms for underwater swarm robotics requires evaluation across multiple dimensions that reflect the fundamental constraints and requirements of marine environments. Drawing on characteristics identified in the underwater swarm robotics literature [4], this framework evaluates algorithms across four critical dimensions: communication dependency, environmental adaptability, energy efficiency, and swarm scalability. Conceptually, the resulting four-dimensional classification space can be visualised as a multi-dimensional matrix in which each algorithm occupies a distinct region according to its characteristics in communication dependency, environmental adaptability, energy efficiency, and swarm scalability.

Communication dependency measures the extent to which an algorithm relies on explicit message exchange or global state information for effective coordination. Algorithms with low communication dependency, such as WOA and MPA, operate effectively with minimal message exchange, making them well suited to acoustic environments characterised by bandwidth limitations and propagation delays [35,38]. Algorithms with moderate communication dependency, such as AFSA and CRO, require neighbourhood interactions or local information exchange, necessitating careful bandwidth management [33,37]. This dimension directly influences algorithm selection based on available communication infrastructure and energy constraints.

Environmental adaptability captures an algorithm’s ability to maintain performance under varying marine conditions, including currents, temperature gradients, turbidity, and pressure variations. Algorithms inspired by marine organisms that naturally adapt to environmental change, such as AFSA’s fish schooling behaviours and MPA’s predator–prey dynamics, demonstrate high adaptability [32,82]. WOA’s bubble-net hunting strategies adapt to prey motion and ocean currents, while CRO’s competitive mechanisms respond to environmental changes through reef-space dynamics [83,84]. This dimension is critical for missions operating across diverse environmental conditions.

Energy efficiency evaluates computational complexity and communication overhead, both of which affect mission duration and operational feasibility. All four marine-specific algorithms operate at complexity per iteration, as reported for WOA [35], MPA [38], AFSA [33], and CRO [37], but they differ in parameter requirements and neighbourhood computation. WOA and MPA offer efficient operation with minimal control parameters, whereas AFSA and CRO incur additional overhead due to neighbourhood evaluation and settlement processes. Communication energy costs further differentiate algorithms, with low-communication approaches naturally supporting extended mission duration.

Swarm scalability assesses algorithm performance as the number of agents increases, evaluating whether coordination mechanisms remain effective across different swarm sizes. Algorithms that rely primarily on local interactions, such as AFSA’s neighbourhood-based coordination, scale well through distributed mechanisms [33]. WOA and MPA also demonstrate good scalability through population-based optimisation that scales linearly with swarm size [85,86]. CRO’s grid-based structure provides moderate scalability, with performance dependent on grid size and reproduction parameters [37].

These four dimensions are not independent; they interact in ways that create complex trade-offs. Algorithms with low communication dependency often exhibit higher energy efficiency but may sacrifice coordination fidelity. High environmental adaptability may demand greater computational resources, reducing energy efficiency. Understanding these interdependencies enables systematic algorithm selection based on mission-specific priorities and constraints.

6.2. Mapping of Existing Bio-Inspired Algorithms

The classification framework enables systematic mapping of marine-specific bio-inspired algorithms across the four-dimensional space, revealing distinct positioning that reflects their biological inspiration and computational characteristics. This mapping provides a structured basis for understanding algorithm suitability for different mission requirements and operational constraints. Table 6 presents a comprehensive comparison of marine-specific bio-inspired algorithms for underwater swarm robotics applications.

Table 6.

Comprehensive comparison of marine-specific bio-inspired algorithms for underwater swarm robotics applications.

AFSA occupies a position characterised by moderate communication dependency, high environmental adaptability, moderate energy efficiency, and good scalability [32,33]. AFSA’s fish-schooling inspiration provides natural adaptation to marine conditions through collective behaviour, while its visual perception system enables coordination through environmental sensing rather than explicit message passing. The algorithm’s moderate communication requirements stem from neighbourhood interactions needed for swarming and following behaviours, creating a balance between coordination effectiveness and communication efficiency.

WOA demonstrates low communication dependency, high environmental adaptability, high energy efficiency, and good scalability. Mirjalili and Lewis introduced the Whale Optimisation Algorithm [35], Rana et al. reviewed subsequent applications and modifications [36], and Yan et al. demonstrated an AUV 3D path-planning formulation based on WOA [24]. WOA’s bubble-net hunting strategy requires minimal explicit communication, with coordination emerging from shared environmental cues and global best solutions. The algorithm’s streamlined optimisation process with few control parameters contributes to high energy efficiency, while its population-based structure enables effective scaling with swarm size.

CRO exhibits moderate communication dependency, moderate environmental adaptability, moderate energy efficiency, and moderate scalability. Salcedo-Sanz et al. introduced the Coral Reefs Optimisation algorithm [37], and later studies refined and applied CRO variants in broader optimisation contexts [25,89]. CRO’s reef-based competition mechanisms require moderate communication for spatial organisation and competitive interactions. The algorithm’s balanced exploration–exploitation behaviour supports moderate energy efficiency, while its grid-based structure offers scalability dependent on grid size and reproduction settings.

MPA demonstrates low communication dependency, high environmental adaptability, high energy efficiency, and good scalability. Faramarzi et al. proposed the Marine Predators Algorithm [38], Al-Betar et al. reported improved/extended variants [39], and Bujok provided a comparative evaluation across benchmark functions [88]. MPA’s predator–prey dynamics enable effective coordination with minimal communication overhead, while its three-phase optimisation process adapts to different velocity ratios and environmental conditions. Its derivative-free formulation and limited parameter set contribute to energy efficiency, and its population-based structure supports scaling.

This mapping reveals that no single algorithm dominates across all dimensions, highlighting the importance of mission-driven selection. Algorithms cluster into distinct regions of the classification space, with WOA and MPA occupying similar regions characterised by low communication dependency and high efficiency, while AFSA and CRO occupy positions with moderate communication demands and differing adaptability and scalability characteristics.

6.3. Comparative Evaluation of Marine-Specific Algorithms (AFSA, WOA, CRO, MPA)

Systematic comparison of AFSA, WOA, CRO, and MPA reveals distinct performance characteristics that directly influence their suitability for underwater swarm robotics. A key limitation, however, is the absence of unified comparative studies that evaluate all four algorithms under consistent underwater-specific conditions, creating a gap in evidence-based algorithm selection [7]. Current insights rely on composite interpretations of separate studies that use different benchmarks, metrics, and environmental assumptions.

In terms of communication dependency, WOA and MPA exhibit low communication requirements, relying primarily on global phase transitions or implicit coordination mechanisms rather than frequent inter-agent exchanges [35,38]. In contrast, AFSA and CRO require moderate neighbourhood-level interactions to maintain swarm cohesion and support spatial competition [33,37]. This distinction is particularly critical in bandwidth-constrained acoustic communication environments.

From the standpoint of energy and computational efficiency, all four algorithms maintain a per-iteration complexity of , where N is the number of agents and D the dimensionality of the solution space. WOA and MPA benefit from minimal control parameters and simpler update mechanisms, while AFSA and CRO involve additional local decision rules and competition-based resource allocation that increase processing overhead.

Regarding convergence and scalability, WOA’s spiral bubble-net search enables fast convergence in smooth environments [35,87], while MPA’s dual-phase Lévy and Brownian motion dynamics balance exploration and exploitation [38]. AFSA maintains high population diversity through crowding factors but converges more gradually [33]. CRO strikes a balance via competitive resource settlement among reef positions [37].

In terms of adaptability, AFSA and MPA demonstrate robust responses to environmental fluctuations due to their biologically grounded foraging dynamics [32,82]. WOA has been shown to adapt well to dynamic targets and current-driven changes [24], while CRO’s ecosystem modelling supports moderate flexibility in multi-objective optimisation tasks [84].

Underwater application studies show differentiated use. AFSA has been applied to environmental monitoring, cooperative data collection, and Underwater Wireless Sensor Network routing [23,31]. WOA variants have been employed in AUV path planning and current-aware navigation [24]. MPA has been used for sensor network deployment and coverage optimisation, with emerging work in AUV control [39,88]. CRO demonstrates strong performance in general optimisation but has limited underwater-specific validation [37].

Comparative evaluations across recent benchmarks have reinforced the distinct strengths of each algorithm. Pourpanah et al. [33] reported that AFSA maintains swarm diversity and accurate local search when extended through hybrid variants incorporating task-specific heuristics. Nadimi-Shahraki et al. [87] showed that WOA achieves fast convergence with relatively simple parameter settings, outperforming several traditional optimisers on a range of benchmark optimisation tasks. Salcedo-Sanz et al. [37] demonstrated that CRO provides competitive performance in multi-objective optimisation, reliably identifying near-optimal trade-offs in constrained search spaces. Bujok [88] finds that MPA, through its phase-based movement strategies, attains highly competitive absolute ranking scores across diverse benchmark functions. This indicates robust global search capability and adaptability.

No single coordination model dominates across all performance metrics. Algorithm selection must reflect mission-specific objectives, communication limitations, and energy budgets. In this context, hybrid approaches that combine complementary algorithmic strengths represent a promising direction. For example, such approaches might integrate AFSA’s local adaptability, WOA’s global search efficiency, and MPA’s phase transitions. These integrated frameworks can offer enhanced convergence, scalability, and robustness under uncertain underwater conditions. Empirical trends support integrating algorithmic features, for example combining MPA’s Lévy-Brownian phases with AFSA’s crowding mechanism, to build hybrid coordination models capable of addressing the multi-faceted challenges present in underwater swarm robotics.

A consistent evaluation framework using shared metrics, mission profiles, and environmental models is needed to enable fair and transparent comparison, complementing the narrative synthesis of algorithm-specific strengths discussed in this section.

6.4. Integration of Algorithmic, Communication, and Hardware Perspectives

Effective underwater swarm robotics requires coherent integration of algorithms, communication strategies, and hardware capabilities. These domains are strongly interdependent and cannot be optimised independently. The classification framework provides a basis for analysing these interactions and aligning design choices with mission requirements.

Algorithm selection influences both communication and hardware requirements. Low-communication algorithms such as WOA and MPA reduce acoustic traffic and transmission energy, enabling simpler modem configurations and longer mission durations [35,38]. Algorithms with moderate communication needs, such as AFSA and CRO, may require more capable modems or hybrid acoustic–optical architectures to maintain performance [33,37].

Communication constraints shape algorithm feasibility and swarm architecture. Severe bandwidth limits favour algorithms that rely on local sensing and minimal message exchange; intermittent connectivity requires fault-tolerant coordination that remains functional during communication blackouts [7,48]. Hardware platforms must integrate suitable communication modalities and antenna designs to support these strategies, influencing size, cost, and payload allocation.

Hardware capabilities, in turn, constrain algorithm and communication choices. Compact vehicles with limited payload and power cannot support heavy sensing loads or multiple high-power modems, favouring algorithms that operate effectively with sparse sensing and low-rate communication [61,70]. Energy limitations demand algorithms and protocols that minimise communication and computation, reinforcing the importance of energy-aware design [60,69].

These interdependencies illustrate mission-dependent trade-offs. Long-duration environmental monitoring favours low-communication, energy-efficient algorithms on modest hardware. High-precision inspection tasks may prioritise formation fidelity and sensing accuracy, accepting higher communication and energy costs. Complex multi-phase missions may require adaptive systems capable of reconfiguring algorithm parameters, communication modes, and sensing policies in response to changing objectives and conditions.

Cross-layer optimisation approaches offer a way to manage these trade-offs holistically [48,60]. Adaptive physical-layer methods that tune modulation and power settings based on channel conditions exemplify coordination between communication and energy objectives. Energy-aware trajectory planning that leverages currents illustrates how hardware and environment can be exploited to satisfy algorithmic goals while minimising energy use. Such integrated designs represent a key step towards practical, large-scale underwater swarm deployment.

6.5. Summary of Key Trends and Limitations

Synthesising findings across bio-inspired coordination, communication, and system design reveals several key trends in underwater swarm robotics, along with persistent limitations that constrain current progress.

First, there is a clear trend towards marine-specific bio-inspired algorithms that align biological mechanisms with underwater constraints. AFSA, WOA, CRO, and MPA reflect increasing recognition that biologically grounded strategies can address communication limits, environmental variability, and energy constraints more naturally than generic optimisation methods.

Second, communication research has progressed from simple acoustic links to adaptive and hybrid architectures that integrate OFDM, multimodal links, and bio-inspired signalling. Field deployments have demonstrated the feasibility of adaptive physical-layer optimisation and TDMA-based scheduling in real underwater environments [48].

Third, hardware trends point towards modular, cost-effective platforms capable of supporting swarm-scale deployment. Diverse design strategies ranging from high-capability platforms to compact systems illustrate different approaches tuned to various mission profiles [48].

A critical limitation is the scarcity of real-world data and longitudinal field trials. The literature is dominated by simulation studies, with limited progression to empirical validation in representative environments [7]. This restricts understanding of how algorithms, communication strategies, and hardware behave under real ocean conditions, where uncertainty and unmodelled effects are significant.

Future research directions highlighted by this synthesis include the following: (i) empirical validation of swarm systems in realistic marine environments; (ii) development of hybrid algorithms that combine complementary strengths from AFSA, WOA, CRO, and MPA; (iii) advanced communication protocols tailored to multi-vehicle autonomy; (iv) standardised benchmarking and reporting frameworks; and (v) integrated design methodologies that explicitly account for cross-layer interdependencies.