Abstract

Benthic δ18O and δ13C values, as well as the mean grain size (MS) of sortable silt (SS), were used to construct the records of deep-water ventilation during the last 300 ka, at core GC02. This core is located at 4430 m water depth on the Madagascar basin near the Southwest Indian Ocean mid-ridge (SWIR). Decreased values of MS of SS reveal a weakened Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW) in the glacial periods, while increased values indicate enhanced AABW in the interglacial periods. The MS of SS record in GC02 exhibited a particularly good synchronization with a record based on the δ13C gradient between the North Atlantic and tropical Pacific Ocean, indicating that AABW is dominated by the overturning strength of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC), and showed a higher generation rate in the early stages of the glacial periods. A rapid reduction in δ13C occurred in MIS 2, 4, and 6; the MS values in GC02 and winter sea ice (WSI) also exhibited significant decreases and increases, respectively. By controlling the transport of ventilated water mass to deep waters and polar heat transport, in the Indian Ocean, both the change in AABW intensity and the Southern Ocean ice volume result from changes in the AMOC under the orbital modulation background. In the Southwest Indian Ocean, AMOC has a larger effect on ice volume during glacial periods, while its effect on AABW is relatively strong during interglacial periods.

1. Introduction

During the Quaternary period, oceanic thermohaline circulation (THC) played an important role in global climate [1]. THC is characterized by two main deep-water production sites. The first of these is found in the Greenland, Iceland, Norwegian, and Labrador seas, where North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW) is produced [2,3]. The second is located in the Weddell Sea [4,5], where the majority of Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW) is formed. Together, these two bottom currents account for a large proportion of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) and bypass the Cape of Good Hope, contributing to deep water circulation in the Southwest Indian Ocean. Ultimately, Antarctic surface water processes and deep water ventilation rates influence atmospheric CO2 concentration, and these processes may affect climate change [6].

The southwest Indian Ocean is an important passage way that connects the Indian Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean. The transmission of the bottom current is hindered by the Southwest Indian Ridge [7]. The patterns and causes of climate and current variability in the Southwest Indian Ocean during the late Quaternary period are affected by multiple water masses from the two oceans, and are the subject of significant debate [8]. While previous research has mainly focused on the changes to the NADW during glacial–interglacial periods [9,10], our understanding of variations in the AABW remains limited. The core location for the present study is near the interface where the NADW and AABW mix in the Southern Ocean, enabling the reconstruction of the timing and amplitude of changes in the southward advection of AABW and the Southern Ocean THC.

To assess changes in deep bottom flow in the Madagascar Basin near the southwestern Indian Ocean (SIO) during the last 300 ka, we used benthic foraminiferal δ18O (a proxy of the overall composition of the deep water and the bottom water), benthic foraminiferal δ13C (a proxy of NADW/AABW composition of deep water) and mean main sensitive grain size (a proxy for the flow speed of the bottom water mass) to assess changes in deep bottom flow in the Madagascar Basin near the southwestern Indian Ocean during the last 300 ka. Our focus was on identifying the phasing between changes in ice volume, deep ventilation, and near-bottom flow speeds over this period.

2. Study Area

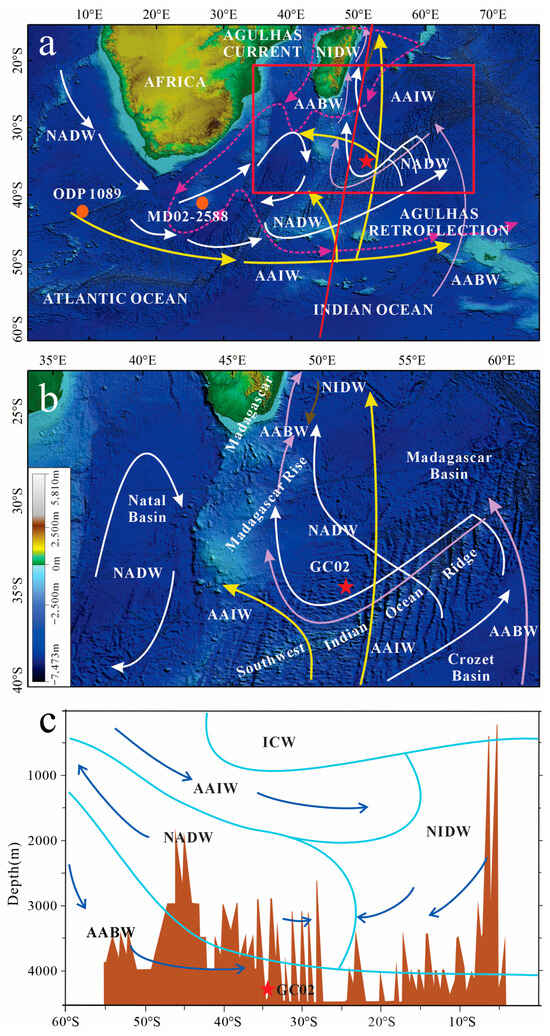

Core GC02 was taken from the southeast slope of the Madagascar Basin, with the Madagascar uplift to the east and the Southwest Indian Ocean mid-ridge to the southeast (Figure 1). The modern bottom currents of the Madagascar Basin mainly originate from the Antarctic Circumpolar Current and are influenced by Antarctic glacier activity. There is much evidence in surface sediments and bottom waters that proves the origin of the currents and records the effects of ice ages and other climate and environmental changes. The SS mean grain-size represents the characteristics of the bottom 1000 m-thick layer of seawater and reflects the source of the Agulhas Plateau. Deep-ocean variability can be reconstructed using this index, which shows changes in the amount of ancient bottom currents [11]. Krueger et al. used benthic δ13C values, kaolinite/chlorite ratios, and SS in sediments from an abyssal Agulhas Basin core to record the varying impact of NADW and AABW. They found that the influence of NADW decreased during glacial periods and increased during interglacial periods, in concert with global climatic changes of the late Quaternary [12]. The detrital sediments in the southern part of the Madagascar Basin are partly derived from aeolian deposits, forming mainly through seabed erosion and transportation [13,14]. Deepwater circulation is characterized primarily by the interaction between southward-propagating NADW and northward-flowing Southern Component Waters (SCW), notably AABW and Antarctic Intermediate Water (AAIW) (Figure 1) [11,13]. The inter-ocean exchange of NADW into the South Indian Ocean occurs directly through the Agulhas Gateway, which is located between the southern tip of Africa and the northern Agulhas Plateau (Figure 1a). Subsequently, the NADW moves northward along the southern edge of the SWIR, turns around 30° S, and then moves south along the SWIR near the core GC02. The northern branch of the AAIW diverges near core GC02 and flows into the Natal Basin, while the northern AABW flows along the SWIR and across the edge of the Madagascar Basin. It is the unique geographical features at this location that cause the complicated stratification of ocean currents in the study area.

The SW Indian Ocean contains at least four layers of water masses with different sources: (1) deep Antarctic waters (Lower Circumpolar Deep Water), which flow northwards; (2) midwater North Indian Deep Water, which flows southwards; (3) Upper Circumpolar Deep Water, which also flows northwards; and (4) meridional convergence of intermediate waters at 500~1500 m and the shallow South Equatorial Current, which flows westwards [13]. The southward-flowing surface current, the Indian Central Water (ICW), is a north-south trending vertical section of water-column stratification reaching to 45° S (Figure 1c). The Antarctic Intermediate Water (AAIW), which lies between the NADW and ICW, is found at mid-depths and slopes downward to the north. Meanwhile, the deep areas (>4000 m) are filled with AABW [15]. Core GC02 is positioned at a depth of 4430 m and is predominantly bathed in AABW, but with a substantial contribution of NADW. Thus, the site offers the possibility of monitoring past variations in NADW and the northward spread of AABW.

Figure 1.

(a) Map of ocean current schematic; (b) sampling location; (c) the schematic representation of water masses and their movement in the Southwest Indian Ocean. The seabed topography data is adapted from the GEBCO_2024 Grid [16], and the ocean current data is adapted from [11,13,17] and [18]. In the upper map, the red rectangle is the Area of map (b), and the red line is the profile of map (c). The purple dash arrows represent ocean currents, mainly the Agulhas Current and Agulhas Retroflection [17]. The yellow, dark purple, dark blue, and gray arrows represent Antarctic Intermediate Water (AAIW), Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW), North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW), and North Indian Deep Water (NIDW), respectively [11,13]. The red star is the location of GC02, and the orange dots are MD02-2588 and ODP 1089; their location is shown in Table 1. ICW, Indian Central Water.

Table 1.

Station information of cores used in this study.

Table 1.

Station information of cores used in this study.

| Core | Latitude | Longitude | Depth, m |

|---|---|---|---|

| GC02 | 33°59.514′ S | 50°54.605′ E | 4430 |

| MD02-2588 [19] | 41°19.9′ S | 25°49.7′ E | 2907 |

| ODP1089 [20] | 40°56.2′ S | 9°53.6′ E | 4621 |

3. Materials and Methods

The samples in our study are push core samples collected from the western slope of the Southwest Indian Ocean mid-ridge (approximately 200 km from the ridge’s midpoint; Lat. 33°59.514′ S, Lon. 50°54.605′ E; water depth: 4430 m; Figure 1b). The 240 cm core was mainly red muddy soil with stratification and some clumping. Samples were taken at 2 cm intervals for stable isotope and grain-size analysis. No structures indicating turbidity deposition or block collapse re-deposition were observed. In most layers, visible foraminifera shells exceeding 0.5 mm in particle size were present. No visible turbidite or ash layer was found, and only minor bioturbation was observed in the core.

The sample was found within the carbonate solution layer and exhibited a certain degree of corrosion. To ensure uniformity across each layer, we selected well-preserved subsurface foraminifera from the genus Globigerina, known for their thick and corrosion-resistant shell walls [21]. Since intact benthic foraminifera were not present in every layer, we opted for a combination of species that were consistently found throughout. Using binoculars, we chose 20 clean and intact subsurface foraminifera of the species Globigerina inflata, along with a selection of benthic foraminifera exceeding 250 µm in size. These specimens were then crushed with a steel needle to ensure the compartments were opened and placed into a clean glass tube. An appropriate amount of 3% H2O2 solution was added, and the sample was soaked for 30 min. Subsequently, the samples were ultrasonically shaken in acetone for 30 s, after which the upper suspension was suctioned out, and finally dried at 50 °C.

Stable carbon and oxygen isotopes were analyzed at the Key Laboratory of Submarine Science, Ministry of Natural Resources, China, using a stable isotope mass spectrometer (ISN:002508) and the online phosphoric acid method. During the pretreatment, the sample pool was kept at 72 °C. The phosphoric acid reaction time lasted for 1.2 h, and each sample was analyzed 9 times, with the results presented as averages. The standard deviation across the 9 tests was <0.008‰. The laboratory’s cylinder C2 was calibrated against the international standard (NBS19) and the Chinese calcium carbonate standard (GBW4406). The carbon and oxygen isotopes followed Pee Dee Belemnite (PDB) international standards, and the test results were converted into PDB ratios. The δ13C of benthic foraminifera is considered a good representative of the δ13CDIC of bottom water [22,23]. The δ13C signal in the southern branch of NADW is less than 1‰ [11], whereas AABW exhibits a negative value. Therefore, an increase in the benthic δ13C value in the South Atlantic indicates a rise in NADW, while a decrease signifies a shift toward the AABW water mass [12,24]. Additionally, benthic δ18O reflects the stratification of the water column and captures regional climate change.

The mean grain size of sortable silt (10~63 µm) serves as an indicator of paleo-ocean current, and variations in its size can reflect hydrodynamic changes [25,26]. The lognormal distribution function was used to identify, fit, and segment the particle size components of a single multimodal distribution [27] to separate the effects of different handling media or modes. Meanwhile, the grain size standard deviation method uses the proportions of different grain size layers to derive the environmental sensitivity factor associated with the environmentally sensitive grain size. Here, the peak value indicates the most significant change in grain size across the various layers. For our analysis, we selected the mean grain size range of the main sensitive SS as an indicator of the bottom layer’s sensitivity. The grain size measurements were conducted at the Test Center of the Key Laboratory of Marine Sedimentation and Environmental Geology of the Ministry of Natural Resources, First Institute of Oceanography, China, using a Mastersizer-2000 laser particle size analyzer with a test range of 0.02~2000 µm and a repeat error margin of <3%. We prepared 0.5 g of the selected samples in a beaker, adding 5~10 mL of HCl solution. The samples were left to sit for 12 h, followed by centrifugation, ultrasonic cleaning, and subsequent measurement.

4. Results

4.1. Chronology of GC02

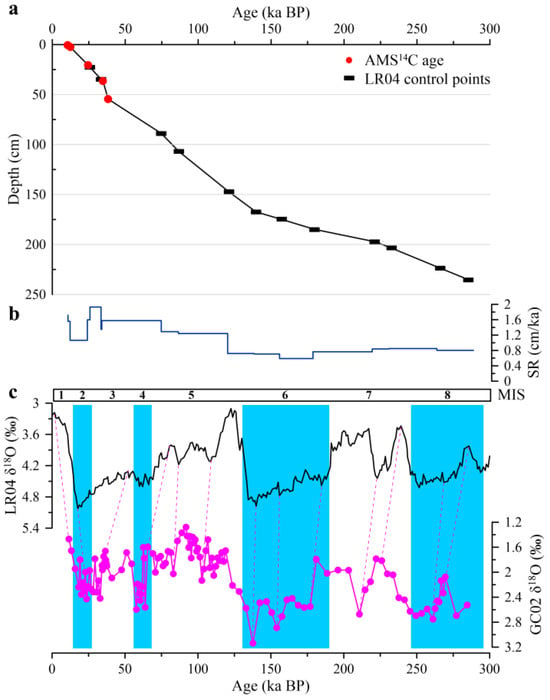

The five layers from GC02 selected for accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) 14C dating samples are detailed in Table 2, with the AMS 14C dating process conducted at the Beta laboratory in the United States. As the age of the AMS 14C dating increases, the accuracy requirements for the tests become more stringent, and a larger number of samples is necessary [28]. The general reliability of carbon dating is 35 ka; however, since the fifth dating result is 38 ka—older than this threshold, and based on a single sample—we chose not to include this last dating point due to the inherent uncertainties (Figure 2). To construct the age model of the core, we used the control points derived from the LR04 stack [29] alongside the AMS 14C dating results. We identified peak and valley points that correspond to the GC02 δ18O curve according to the trends observed in the LR04 stack, allowing for corresponding interpolations to establish the age framework. The δ18O record was analyzed using planktonic foraminifera Globigerina inflata. The oxygen isotope curve, along with the four planktonic foraminifera 14C dating points (Table 2), was correlated to the LR04 stack to obtain 13 δ18O age control points. Following this, we conducted equidistant interpolation for the age-depth distribution to establish a columnar age framework (Figure 2).

Table 2.

The 14C AMS Ages on subsurface planktonic foraminifera and Calibrated Ages for Core GC02.

Figure 2.

(a) Age model of core GC02; (b) sediment rates (SR); and (c) subsurface planktonic foraminifera δ18O record of core GC02 and LR04 [29]. The red dotted lines are control points of the core GC02 δ18O carve corresponding to the LR04 curve.

Table 2 presents the AMS 14C data calibrated values generated using the Calib 8.0 software [30] and δ18O dating correlated to the LR04 stack [29]. We constructed an age model for the sediment core by plotting age versus depth and using the stratigraphically consistent calibrated ages. Through AMS 14C dating and interpolation based on the LR04 curve (Figure 2a), we determined that the chronological sequence of core GC02 spans from 10.53–295.62 ka BP, with MIS1~8 divided according to δ18O values. In this classification, glacial periods correspond to intervals 2, 4, 6, and 8 (Figure 2). It is important to note that the top layer of core GC02 is absent, a situation similarly observed in nearby waters. Eight columnar samples from the Madagascar Ridge and the Mozambique Basin also indicate surface ages ranging from 3.8~7.2 ka [31]. Based on the dating and interpolation points, we calculated the sedimentation rate for GC02 to be between 0.45~1.98 cm/ka, with an average of 1.01 cm/ka. In comparison to the interglacial period, sedimentation rates were higher during the glacial periods, aligning with increased δ18O values, which suggest that high productivity may have been a key factor driving the higher sedimentation rates (Figure 2).

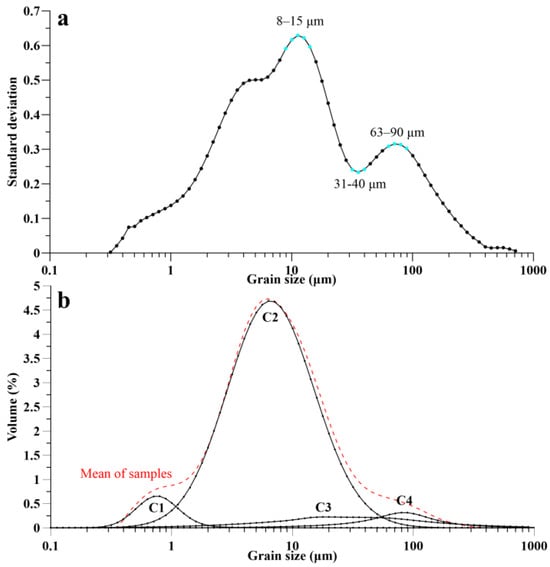

4.2. Main Sensitive Grain Mean Size of Sortable Silt

The grain size range of 1~63 μm accounted for 85.40% of the total sediments, with SS dominating the composition, indicating a significant influence from bottom flow transport.

The average particle size of GC02 was used for component separation, the results correspond to four components: C1~C4 (Figure 3a), with particle sizes corresponding to 0.9 μm (0.7~1.7 μm), 5.9 μm (4.2~9.6 μm), 31.73 μm (13.1~63.4 μm) and 81.1 μm (65.4~108.3 μm), and the corresponding component contents are 5.9% (4.2~15.3%), 85.4% (66.0~94.8%), 12.0% (1.92~24.0%) and 7.1% (1.7~20.63%), respectively. C2 is the main particle size end member of the sample, which can reflect the strength of the hydrodynamic transport capacity of the bottom layer. Core GC02 predominantly featured three sensitive grain sizes: 8~15 μm, 31~40 μm, and 63~90 μm (Figure 3b). The average proportions of these three sensitive grain sizes were 21.25%, 2.88%, and 2.20%, respectively. Among these, the 8~15 μm range emerged as the primary sensitive grain size.

Figure 3.

The standard deviation distribution (a) and grain size composition division (b) of core GC02.

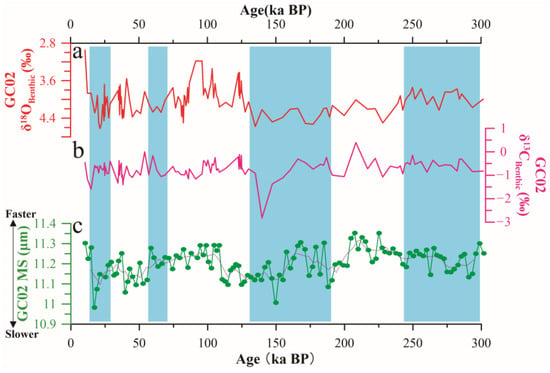

After comprehensive analysis, the 8~15 μm size range was chosen as the main sensitive grain size within the SS, to avoid the influence of fine particle aggregate deposition on the bottom hydrodynamic analysis. This also effectively reflects the movement of the bottom flow. The MS of SS showed complex variations, showing no particularly significant differences between glacial and interglacial periods (Figure 4). The MS values declined during the early phases of MIS2, 3, 8, and late MIS5, 6, while increases were observed during the early stages of MIS1, 5, 6, and 7. From the perspective of trend, the MS records displayed positive correlations on orbital timescales, while the δ13C values from GC02 exhibited an opposite trend, suggesting that enhanced physical circulation (reflected in MS) alongside improved chemical ventilation (evidenced by benthic δ13C).

Figure 4.

Benthic records of GC02 showing. (a) Benthic δ18O records; (b) benthic δ13C records; and (c) the mean main sensitive grain size of silt in GC02. The gray dashed line is a smoothing curve. Glacial phases in this study are highlighted by blue shading.

4.3. Stable Isotope

The benthic δ18O in Core GC02 varied from 2.96‰ to 4.56‰ during MIS1, 3, 5, and ranged from 3.18‰ to 4.22‰ during MIS 2, 4, 6, and 8. The glacial/interglacial shifts were approximately 0.8‰. The average benthic δ18O value for Core GC02 was approximately 3.85‰, clearly highlighting the relative difference between glacial and interglacial periods (Figure 4). In terms of δ13C, there was a decline during MIS 1, 3, 5, and 7, reaching a minimum of −2.70‰, while δ13C increased slightly during MIS 2, 4, 6, and 8. The average benthic δ13C value was −0.74‰, which closely aligns with the δ13C of AABW, indicating a significant influence from AABW. The δ13C values during interglacial periods were considerably higher than those during glacial periods, with variations during the transfer/interglacial stages approaching 0.90‰. Due to the mixed species composition used in the analyses, the consistency of δ13C variations was less pronounced than with other records; thus, combining these records was essential for quantitatively analyzing changes in bottom water.

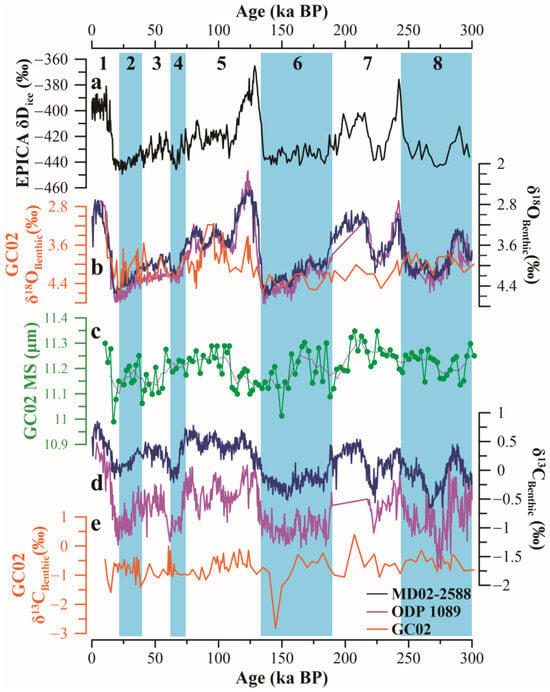

In Core GC02 and ODP1089, the δ13C value was notably low, hovering around −1‰. Conversely, the δ13C in ODP1089 was lighter than −1‰ during glacial periods and less than −0.25‰ during interglacial periods (Figure 5). Specifically, the δ13C values in GC02 ranged from −1‰ to−0.25‰ in the interglacial periods, exhibiting significant fluctuations, with the lowest recorded value nearing −1‰. The δ13C of ODP1089 fell below −1‰ during glacial periods and below −0.25‰ in interglacial periods. Overall, δ13C in Core GC02 fluctuated between −1‰ and −0.25‰ during interglacial periods and demonstrated substantial variability, reaching its lightest value close to −1‰.

Figure 5.

Southwest Indian ocean records across the last 300 ka. (a) The Antarctic European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica (EPICA) ice-core δD (gray), adapted from [32]; (b) comparison of the GC02 benthic δ18O (mixed species; orange) with ODP1089 δ18O (Cibicidoides; purple), adapted from [20,33] and MD02-2588 benthic δ18O (Cibicides wuellerstorfi; blue), adapted from [19]; (c) the main sensitive grain size mean (MS) of sortable silt in GC02 (green); (d) the MD02-2588 benthic δ13C (Cibicides wuellerstorfi; blue), adapted from [19] and the ODP1089 δ13C (Cibicidoides; purple), adapted from [20]; (e) GC02 benthic δ13C (mixed species; orange). Numbers on the top indicate the MIS period, and blue shadows represent glacial periods.

5. Discussion

5.1. Characteristics of AABW Masses near SWIR

Sortable silt serves as a measure of flow speed in the layer 20~100 m above the seabed, with higher values indicating greater flow speeds [26]. The MS of SS in core GC02 is particularly sensitive to changes in bottom flow, with high values reflecting increased flow speed. Over the last 300 ka, core GC02 has predominantly been situated in AABW. We propose that the increase in MS is a result of an increase in AABW flow speed, which may indicate the extent of the AABW’s influence. Spooner et al. [34] support this hypothesis, demonstrating that during the last glacial period, the increased SS on the eastern side was likely associated with an increase in the northward velocity of AABW in the Vema Channel. The rising MS of SS values correspond to an enhanced AABW velocity, and conversely, lower values indicate reduced flow speeds. The variation of AABW in the study area in the last 300 ka is shown in Figure 5c. The data show that the MS of SS and the oxygen isotope curve regions are consistent (Figure 5). The overall trend of AABW is weakening during glacial periods and strengthening during interglacial periods. There are several special cases during MIS 2, 6, and 8 periods (glacial periods) where AABW first strengthened and then weakened, indicating that AABW had a high generation rate in the early glacial period, which is consistent with Krueger et al. [12] and Bali et al. [35] research results. In addition, AABW did not show a significant enhancement in the MIS3 phase. This is because, although MIS3 was considered an interglacial period, it did not fully develop and was a brief transitional period between MIS4 and MIS2. This situation is consistent with the overall climate background.

Hall et al. [36] demonstrated a relationship between SS grain sizes at ODP1123 in the SW Pacific and benthic δ18O and δ13C isotopes across orbital frequencies. They identified a relationship between SS and the Pacific deep water δ13C ageing, where periods of reduced ageing indicated increased deep western boundary current (DWBC) flow speeds (physical ventilation). They concluded that these flow changes may be linked to enhanced AABW production during glacial periods, potentially influenced by Southern Ocean winds or increased sea ice formation. A similar orbital-scale relationship was observed in the GC02 records, where decreased benthic δ13C (mixed species) corresponded with increased near-bottom flow speeds. However, since the fluctuations in δ13C were minimal, we opted to use the δ13C gradient [37] between the North Atlantic and tropical Pacific Ocean to better reflect changes in physical ventilation during each period (Figure 6c). Krueger et al. [12] examined a core from the abyssal Agulhas Basin and found that the highest rates of AABW production occurred during early glacial periods. This was when increased sea ice formation and active ice shelf water (ISW) production led to the formation of substantial amounts of deep water, similar to GC02 records. During interglacial periods, including the moderate interglacial MIS 3, both brine formation and ISW production contributed to AABW formation in the Weddell Sea. As a result, AABW gradually strengthened in the early interglacial period and reached its maximum value in the middle period (Figure 5). Therefore, sea ice in the South Ocean may not be the predominant factor controlling changes in AABW in the Southwest Indian Ocean.

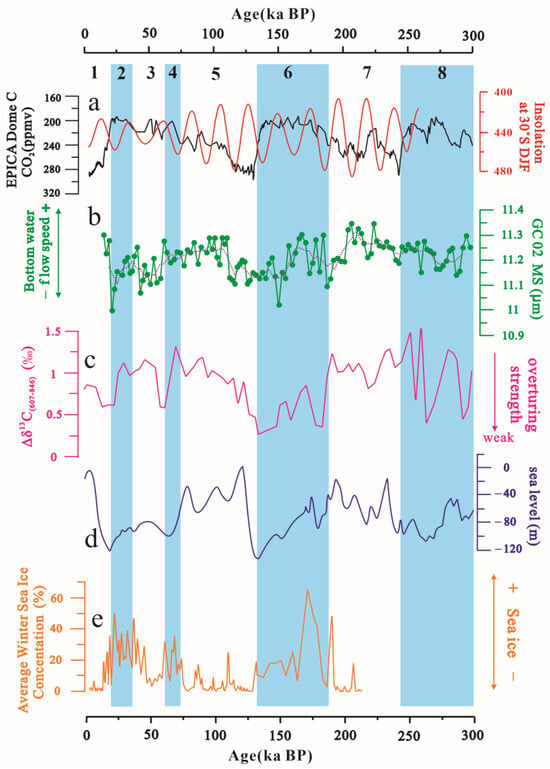

Figure 6.

(a) The EPICA Dome C CO2 record and winter (DJF) insolation at 30° S, adapted from [38]; (b) the main sensitive grain size mean (MS) of sortable silt in GC02 (green), dash line is smooth curve, arrows indicating rapid decrease of AABW flow speed; (c) a measure of overturning strength based on δ13C gradient, adapted from [37], between the North Atlantic (ODP site 607), adapted from [39] and the tropical Pacific Ocean (ODP site 846), adapted from [40]; (d) global sea level change, adapted from [41]; (e) winter sea ice concentration estimates from generalized additive model, adapted from [42].

5.2. Characteristics and Comparison of Regional Deep Water

To further investigate the deep water masses within the study area, we compared the data from core GC02 with other cores in adjacent areas, specifically MD02-2588’s δ18O Cibicidoides and benthic δ13C records (Cibicides wuellerstorfi) [19], as well as the δ18O and δ13C Cibicidoides records from ODP1089 (Cibicidoides) [20,33]. All isotopic measurements were made on benthic foraminifera. Notably, the glacial–interglacial fluctuations in benthic δ18O (ranging from 1~1.6‰) were significantly larger than the shifts associated with global ice volume (1~1.2‰) [43], indicating variations in temperature and salinity within the bottom currents.

The δ13C signal from GC02 exhibited a strong negative correlation with those of MD02-2588 and ODP1089 (Figure 5d,e). The depth of MD2-2588 is relatively shallow (2907 m), with δ13C values typically ranging from 0 to −0.5‰ during glacial periods, and remaining below 0.5‰ during the interglacial periods. This suggests a primary influence from NADW with some partial contributions from the Lower Circumpolar Deep Water [12]. In comparison to the mid-depth Atlantic benthic δ13C stacks (the upper boundary of blue shading), the deep Atlantic benthic δ13C stacks align more closely with those of ODP1089 and GC02, indicating a stronger influence from AABW. In addition, it is noteworthy that the MS record exhibits particularly strong synchronicity with benthic δ18O in GC02. This suggests that the temperature and salinity of the bottom water were predominantly influenced by AABW within the study area. Overall, these findings indicate that the deep-water mass in the region has been primarily dominated by AABW during the last 300 ka.

Compared to ODP1089, the benthic stable isotope record from core MD02-2588 reveals a significant offset of 1.25‰ towards higher δ13C values during glacial periods, and 0.8‰ during interglacial periods. This discrepancy can be attributed to the geographical positioning of core MD02-2588 within the center of the NADW tongue, which brings a heavier δ13C signal during interglacial phases. In contrast, ODP1089 is influenced by AABW, characterized by a lighter δ13C signal. During glacial periods, the pronounced shift in δ13C values can be explained by a notable reduction in NADW export to the South Atlantic, leading to lighter δ13C values typical of AABW [12]. A similar situation occurred within the Sub-Antarctic Mode Waters (SAMW) and CDW δ13C gradient. Ziegler et al. [19] proposed an alternative interpretation for this phenomenon, suggesting that rapid and substantial changes in the Southern Ocean carbon cycle lead to distinct glacial–interglacial variations in the mid-depth δ13C gradient. During periods of full glaciation, heightened dust flux resulted in higher nutrient utilization and higher biological productivity; thus, intensifying the mid-depth δ13C gradient. Conversely, interglacial periods exhibited a reversal of these conditions. It is remarkable that the magnitude of δ13C fluctuations observed in core GC02 during glacial–interglacial transitions parallels that of MD02-2588, corroborating the findings of [11]. Diz et al. [44] propose that during glacial periods, there is an admixture of a well-ventilated water mass to the deep waters of the South Atlantic, characterized by a δ13C signature similar to the present-day NADW. This water mass could either be sourced from the glacial AAIW or a younger deep water formation of southern origin that carries a higher δ13C signal resulting from recent air–sea gas exchange [45].

The well correlation observed between the δ18O records of subsurface planktonic foraminifera and benthic samples from GC02 and the δD record from the Antarctic European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica (EPICA) [46] as well as the LR04 stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records compiled by Lisiecki and Raymo [29], suggests that variations in Antarctic ice volume significantly influence on δ18O variability (Figure 2c and Figure 5a). As discussed in the previous analysis, sea ice in the South Ocean is not the dominant factor controlling changes in AABW in the southwest Indian Ocean, but they are strongly correlated. Therefore, the δ13C gradient depicted in Figure 6c, which measures the efficiency of deep ocean ventilation and serves as an indicator of the AMOC, was chosen for further analysis as a potential mechanism.

5.3. Driving Mechanism in Climate and Water Mass

The MS of the SS recorded in GC02 correlates well with the EPICA Dome C CO2 record and winter (DJF) insolation at 30° S [38] on an orbital scale (Figure 6). This is consistent with the driving role of SS observed in other studies in the Southern Ocean, as previously discussed. Notably, the change in the MS records in GC02 exhibited a significant lag period, compared to the EPICA Dome C CO2 record (Figure 6), representing the change in surface atmospheric-seawater temperature. This situation was not apparent in surface seawater temperature (SST) records from the Southern Ocean [33]. These results suggest that deep ocean water was isolated from the surface-intermediate ocean during these periods due to weakened ocean circulation.

It often takes deep water a millennium or more to circulate through the ocean [7]. Separation from the deep ocean’s large heat reservoir would result in relatively fast thermal exchange between the lower atmosphere and the surface ocean, leading to a more rapid response of surface water temperatures to changes in insolation.

To test whether the AMOC controls the AABW in the Southwest Indian Ocean, we compared the MS of SS records in GC02 with the δ13C gradient between the North Atlantic and the tropical Pacific Ocean. This gradient is a measure of overturning strength and indicates the efficiency of deep ocean ventilation. The GC02 MS records have a broad correspondence with the δ13C gradient. The absence of a δ13C gradient could indicate drastically reduced Atlantic ventilation, or enhanced Pacific ventilation [37,47]. A decrease in δ13C values indicates a substantial decrease in AMOC ventilation, which weakens the transport of AABW, reduces polar heat transport, and amplifies the growth of northern ice sheets. Therefore, the variations in AABW indicated by the GC02 MS record are consistent with the estimates of winter sea ice concentration from the Generalized Additive Model [42] (Figure 6), as reported by Molyneux et al. [11]. Rapid reductions in δ13C occur in MIS 2, 4, and 6, and the MS and WSI values also show significant decreases and increases, respectively. These results indicate that, in the Indian Ocean, changes in AABW intensity and the Southern Ocean ice volume are due to changes in the AMOC against an orbital modulation background. In the study area, the AMOC has a more significant effect on ice volume during glacial periods, while its effect on AABW is relatively stronger during interglacial periods (Figure 6). This causes AABW to exhibit regional characteristics.

6. Conclusions

In the present study, we reconstructed changes in the influence of AABW on the composition of deep and bottom water at the Madagascar Plateau near the SWIR during the last 300 ka through the establishment of an age model, benthic foraminifera oxygen and carbon analysis, and sensitive grain analysis. Our main conclusions are as follows:

- Variations in the GC02 MS values reflect changes in the bottom water flow speed and the degree of AABW impact. Decreased MS values indicate weakened AABW during the late glacial periods. Conversely, increased MS values suggest enhanced AABW during the interglacial periods. Meanwhile, it indicates the phenomenon of strengthening during the early stages of the glacial periods.

- Except for MIS 1, the MS record is particularly synchronous with benthic δ18O in GC02, indicating that the temperature and salinity of bottom water in the Southwest Indian Ocean are mainly controlled by the AABW. In contrast to adjacent areas, our analysis indicates that the AABW exerts a significant influence on the climate of the study area during glacial–interglacial periods during the last 300 ka.

- By controlling the ventilation of water masses and polar heat transport in the Indian Ocean, changes in AABW intensity and Southern Ocean ice volume result from changes in AMOC, which itself arises from orbital modulation. In the Southwest Indian Ocean, the AMOC has a more significant effect on ice volume during glacial periods, while its effect on AABW is relatively strong during interglacial periods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z. and J.Y.; methodology, M.Z. and J.Y.; software, M.Z. and G.L.; validation, M.Z. and O.A.D.; formal analysis, M.Z.; investigation, Z.L.; resources, J.Y.; data curation, J.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Z. and J.Y.; writing—review and editing, J.Y. and O.A.D.; visualization, G.L.; supervision, J.Y.; project administration, J.Y.; funding acquisition, J.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFC0309903) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41806072).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Authors have signed the statement.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this article can be obtained through the author’s email, yangjichao@sdust.edu.cn.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate everyone who assisted us in obtaining the samples. Meanwhile, we would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editor, who helped improve the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MS | mean grain size |

| SS | sortable silt |

| SWIR | Southwest Indian Ocean mid-ridge |

| AABW | Antarctic Bottom Water |

| AMOC | Atlantic meridional overturning circulation |

| WSI | winter sea ice |

| THC | Oceanic thermohaline circulation |

| NADW | North Atlantic Deep Water |

| ICW | Indian Central Water |

| AMS | accelerator mass spectrometry |

References

- Johnson, G.C. Quantifying Antarctic Bottom Water and North Atlantic Deep Water Volumes. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2008, 113, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, C.D.; Fairbanks, R.G. Evidence from Southern Ocean Sediments for the Effect of North Atlantic Deep-Water Flux on Climate. Nature 1992, 355, 416–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, R.R.; Brown, J. The Production of North Atlantic Deep Water: Sources, Rates, and Pathways. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 1994, 99, 12319–12341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jullion, L.; Garabato, A.C.N.; Bacon, S.; Meredith, M.P.; Brown, P.J.; Torres-Valdés, S.; Speer, K.G.; Holland, P.R.; Dong, J.; Bakker, D.; et al. The contribution of the Weddell Gyre to the lower limb of the Global Overturning Circulation. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2014, 119, 3357–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solodoch, A.; Stewart, A.L.; Hogg, A.M.C.; Morrison, A.K.; Kiss, A.E.; Thompson, A.F.; Purkey, S.G.; Cimoli, L. How Does Antarctic Bottom Water Cross the Southern Ocean? Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2021GL097211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.I.; Liu, Z.; Otto-Bliesner, B.L.; Kutzbach, J.E.; Vavrus, S.J. Southern Ocean Sea-Ice Control of the Glacial North Atlantic Thermohaline Circulation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2003, 30, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapter 4 Circulation and Water Masses of the Southern Ocean: A Review. In Developments in Earth and Environmental Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; Volume 8, pp. 85–114. [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, M.; Lourens, L.J.; Tuenter, E.; Hilgen, F.; Reichart, G.J.; Weber, N. Precession Phasing Offset between Indian Summer Monsoon and Arabian Sea Productivity Linked to Changes in Atlantic Overturning Circulation. Paleoceanography 2010, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, W.B.; Oppo, D.W. Glacial Water Mass Geometry and the Distribution of δ13C of ΣCO2 in the Western Atlantic Ocean. Paleoceanography 2005, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnthein, M.; Winn, K.; Jung, S.J.A.; Duplessy, J.C.; Labeyrie, L.; Erlenkeuser, H.; Ganssen, G. Changes in East Atlantic Deepwater Circulation over the Last 30,000 Years: Eight Time Slice Reconstructions. Paleoceanography 1994, 9, 209–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molyneux, E.G.; Hall, I.R.; Zahn, R.; Diz, P. Deep Water Variability on the Southern Agulhas Plateau: Interhemispheric Links over the Past 170 Ka. Paleoceanography 2007, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, S.; Leuschner, D.C.; Ehrmann, W.; Schmiedl, G.; Mackensen, A. North Atlantic Deep Water and Antarctic Bottom Water Variability during the Last 200 Ka Recorded in an Abyssal Sediment Core off South Africa. Glob. Planet. Change 2012, 80–81, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, T.; Laughton, A.S.; Flemming, N.C.; McCave, I.N.; Kiefer, T.; Thornalley, D.J.R.; Elderfield, H. Deep Flow in the Madagascar–Mascarene Basin over the Last 150000 Years. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2005, 363, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, J.L. On the Total Geostrophic Circulation of the South Atlantic Ocean: Flow Patterns, Tracers, and Transports. Prog. Oceanogr. 1989, 23, 149–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsi, A.H.; Whitworth, T.; Nowlin, W.D. On the Meridional Extent and Fronts of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 1995, 42, 641–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GEBCO Bathymetric Compilation Group. The GEBCO_2024 Grid—A Continuous Terrain Model of the Global Oceans and Land; NERC EDS British Oceanographic Data Centre NOC: Liverpool, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stramma, L.; Lutjeharms, J.R.E. The Flow Field of the Subtropical Gyre of the South Indian Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 1997, 102, 5513–5530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.L.; Henderson, G.M.; Robinson, L.F. Interpretation of the 231Pa/230Th Paleocirculation Proxy: New Water-Column Measurements from the Southwest Indian Ocean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2006, 241, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, M.; Diz, P.; Hall, I.R.; Zahn, R. Millennial-Scale Changes in Atmospheric CO2 Levels Linked to the Southern Ocean Carbon Isotope Gradient and Dust Flux. Nat. Geosci. 2013, 6, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, G.; Abelmann, A.; Gersonde, R. The Last Five Glacial-Interglacial Transitions: A High-Resolution 450,000-Year Record from the Subantarctic Atlantic. Paleoceanography 2007, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, W.H.; Parker, F.L. Diversity of Planktonic Foraminifera in Deep-Sea Sediments. Science 1970, 168, 1345–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCorkle, D.C.; Keigwin, L.D. Depth Profiles of δ13C in Bottom Water and Core Top C. Wuellerstorfi on the Ontong Java Plateau and Emperor Seamounts. Paleoceanography 1994, 9, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch-Stieglitz, J.; Adkins, J.F.; Curry, W.B.; Dokken, T.; Hall, I.R.; Herguera, J.C.; Hirschi, J.J.M.; Ivanova, E.V.; Kissel, C.; Marchal, O.; et al. Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation During the Last Glacial Maximum. Science 2007, 316, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackensen, A.; Rudolph, M.; Kuhn, G. Late Pleistocene Deep-Water Circulation in the Subantarctic Eastern Atlantic. Glob. Planet. Change 2001, 30, 197–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manighetti, B.; McCave, I.N. Late Glacial and Holocene Palaeocurrents around Rockall Bank, NE Atlantic Ocean. Paleoceanography 1995, 10, 611–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCave, I.N.; Hall, I.R. Size Sorting in Marine Muds: Processes, Pitfalls, and Prospects for Paleoflow-Speed Proxies. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 2006, 7, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Chang, Z.; Si, B.; Qin, X.; Itoh, S.; Lomtatidze, Z. Partitioning of the grain-size components of Dali Lake core sediments: Evidence for lake-level changes during the Holocene. J. Paleolimnol. 2009, 42, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, J.J.; Walker, M. Reconstructing Quaternary Environments, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisiecki, L.E.; Raymo, M.E. A Pliocene-Pleistocene Stack of 57 Globally Distributed Benthic δ18O Records. Paleoceanography 2005, 20, PA1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuiver, M.; Reimer, P.J. Extended 14C Data Base and Revised CALIB 3.0 14C Age Calibration Program. Radiocarbon 1993, 35, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.J.; Piotrowski, A.M.; Galy, A.; McCave, I.N. A Boundary Exchange Influence on Deglacial Neodymium Isotope Records from the Deep Western Indian Ocean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2012, 341–344, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouzel, J.; Masson-Delmotte, V.; Cattani, O.; Dreyfus, G.; Falourd, S.; Hoffmann, G.; Minster, B.; Nouet, J.; Barnola, J.M.; Chappellaz, J.; et al. Orbital and millennial Antarctic climate variability over the past 800,000 years. Science 2007, 317, 793–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodell, D.A.; Venz, K.A.; Charles, C.D.; Ninnemann, U.S. Pleistocene Vertical Carbon Isotope and Carbonate Gradients in the South Atlantic Sector of the Southern Ocean. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 2003, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spooner, P.T.; Thornalley, D.J.R.; Ellis, P. Grain Size Constraints on Glacial Circulation in the Southwest Atlantic. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 2018, 33, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, H.; Gupta, A.K.; Joseph, S.; Kaushik, A. Exploring the deep water mass turnovers in the eastern indian ocean since the late oligocene: Significance of ocean gateways and paleoclimate. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2024, 657, 112607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, I.R.; McCave, I.N.; Shackleton, N.J.; Weedon, G.P.; Harris, S.E. Intensified Deep Pacific Inflow and Ventilation in Pleistocene Glacial Times. Nature 2001, 412, 809–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bard, E.; Rickaby, R.E.M. Migration of the Subtropical Front as a Modulator of Glacial Climate. Nature 2009, 460, 380–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.L. Long-Term Variations of Caloric Insolation Resulting from the Earth’s Orbital Elements. Quat. Res. 1978, 9, 139–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddiman, W.F.; Raymo, M.E.; Martinson, D.G.; Clement, B.M.; Backman, J. Pleistocene Evolution: Northern Hemisphere Ice Sheets and North Atlantic Ocean. Paleoceanography 1989, 4, 353–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mix, A.C.; Le, J.; Shackleton, N.J. Benthic foraminiferal stable isotope stratigraphy of site 846: 0-1.8 Ma. In Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results; Pisias, N.G., Mayer, L.A., Janecek, T.R., Palmer-Julson, A., van Andel, T.H., Eds.; Ocean Drilling Program: College Station, TX, USA, 1995; Volume 138, pp. 839–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skumryev, V.; Stoyanov, S.; Zhang, Y.; Hadjipanayis, G.; Givord, D.; Nogués, J. Beating the Superparamagnetic Limit with Exchange Bias. Nature 2003, 423, 850–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosta, X.; Sturm, A.; Armand, L.; Pichon, J.J. Late Quaternary Sea Ice History in the Indian Sector of the Southern Ocean as Recorded by Diatom Assemblages. Mar. Micropaleontol. 2004, 50, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrag, D.P.; Adkins, J.F.; McIntyre, K.; Alexander, J.L.; Hodell, D.A.; Charles, C.D.; McManus, J.F. The Oxygen Isotopic Composition of Seawater during the Last Glacial Maximum. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2002, 21, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diz, P.; Hall, I.R.; Zahn, R.; Molyneux, E.G. Paleoceanography of the Southern Agulhas Plateau during the Last 150 Ka: Inferences from Benthic Foraminiferal Assemblages and Multispecies Epifaunal Carbon Isotopes. Paleoceanography 2007, 22, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppo, D.W.; Horowitz, M. Glacial deep water geometry: South Atlantic benthic foraminiferal Cd/Ca and d13C evidence. Paleoceanography 2000, 15, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin, L.; Barbante, C.; Barnes, P.R.F.; Marc Barnola, J.; Bigler, M.; Castellano, E.; Cattani, O.; Chappellaz, J.; Dahl-Jensen, D.; Delmonte, B.; et al. Eight Glacial Cycles from an Antarctic Ice Core. Nature 2004, 429, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uemura, R.; Motoyama, H.; Masson-Delmotte, V.; Jouzel, J.; Kawamura, K.; Goto-Azuma, K.; Fujita, S.; Kuramoto, T.; Hirabayashi, M.; Miyake, T.; et al. Asynchrony between Antarctic Temperature and CO2 Associated with Obliquity over the Past 720,000 Years. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.