A Reinforcement Learning Method for Automated Guided Vehicle Dispatching and Path Planning Considering Charging and Path Conflicts at an Automated Container Terminal

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- The AGV dispatching and path planning problem under a horizontal yard layout is formulated as a Markov decision process (MDP), aiming to improve the transporting efficiency at transshipment container terminals. A general simulator for an AGV real-time scheduling system is developed to capture the dynamic and diverse operational states of AGVs. The framework explicitly incorporates charging constraints as well as multiple types of path conflicts.

- (2)

- A multi-agent learning framework is proposed to separately control the AGV dispatching and AGV path planning according to different state representations. The dispatching and path planning policies are shared among all homogeneous AGVs to ensure consistency and scalability. Furthermore, an integrated global–local reward mechanism is tailored to balance individual exploration with cooperative behavior, thereby enhancing both the efficiency of single-agent decisions and the coordination among multiple agents.

- (3)

- The proposed approach is trained using the multi-agent proximal policy optimization (MAPPO) algorithm and evaluated across comprehensive numerical experiments. The results demonstrate that the MAPPO-based RL approach outperforms conventional rule-based benchmarks while achieving real-time solution efficiency at the operational level. In addition, application analyses based on a large-scale ACT scenario are further conducted to provide managerial insights into system configurations and operational strategies.

2. Related Work

2.1. AGV Scheduling Problem

| Citation | Yard Layout | Decisions | Constraints | Solution Method | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | V | D | P | C1 | C2 | ||

| Xu et al. [17] | √ | - | √ | - | - | MIP + HBM | |

| Yue and Fan [15] | √ | - | √ | - | - | MIP + HBM | |

| Wang and Zeng [20] | √ | √ | √ | - | √ | MIP + EM | |

| Gao et al. [6] | √ | √ | - | - | √ | MDP + RL | |

| Xing et al. [8] | √ | √ | - | - | - | MIP + HBM | |

| Duan et al. [7] | √ | √ | - | - | - | MIP + HBM | |

| Li et al. [5] | √ | √ | - | - | - | MIP + HBM | |

| Hu et al. [13] | √ | - | √ | - | √ | MDP + RL | |

| Zhang et al. [9] | √ | √ | - | √ | - | MIP + HBM | |

| Xing et al. [10] | √ | √ | - | √ | - | MIP + HBM | |

| Liu et al. [24] | √ | √ | √ | - | √ | MIP + HBM | |

| Lou et al. [23] | √ | √ | √ | - | √ | MIP + RBM | |

| Liang et al. [22] | √ | √ | √ | - | √ | MIP + HBM | |

| Li et al. [21] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | MDP + RL | |

| Tang et al. [16] | √ | - | √ | - | √ | MIP + HBM | |

| Wu et al. [14] | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | MIP + HBM | |

| Chen et al. [18] | √ | - | √ | - | √ | MIP + HBM | |

| Wang et al. [11] | √ | √ | - | √ | - | MIP + HBM | |

| This paper | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | MDP + RL | |

2.2. Application of Reinforcement Learning Approach on AGV Scheduling Problem

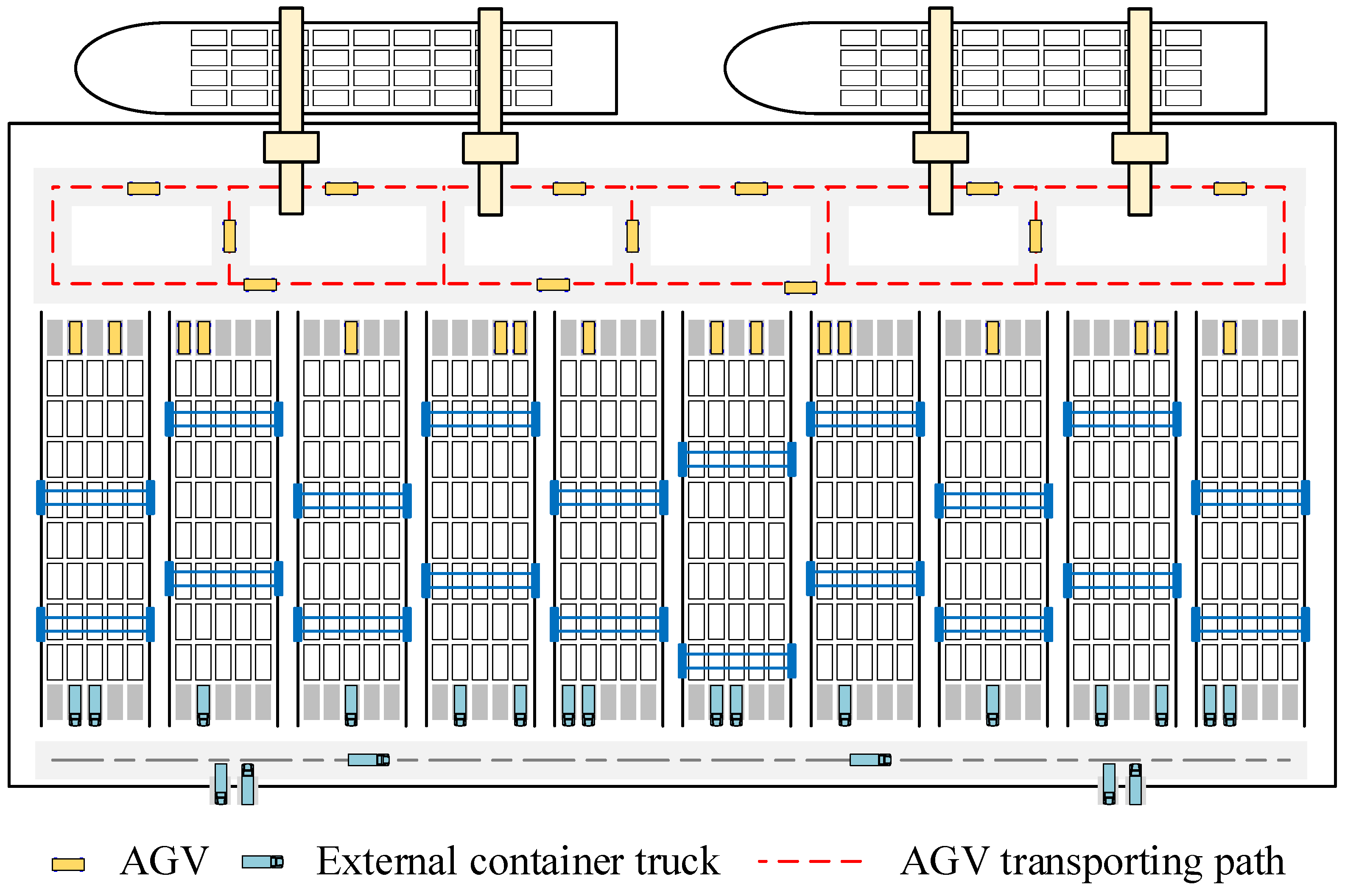

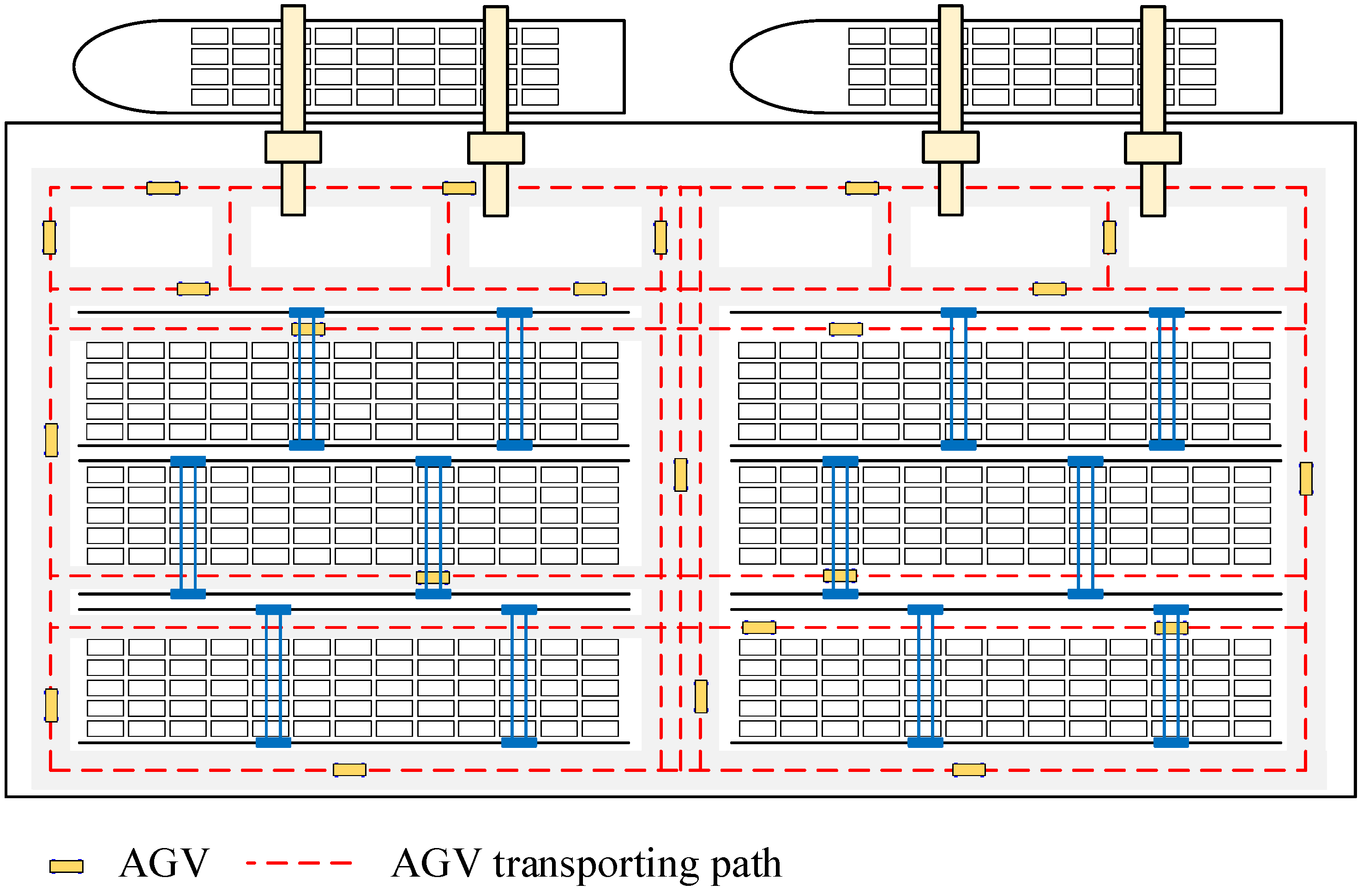

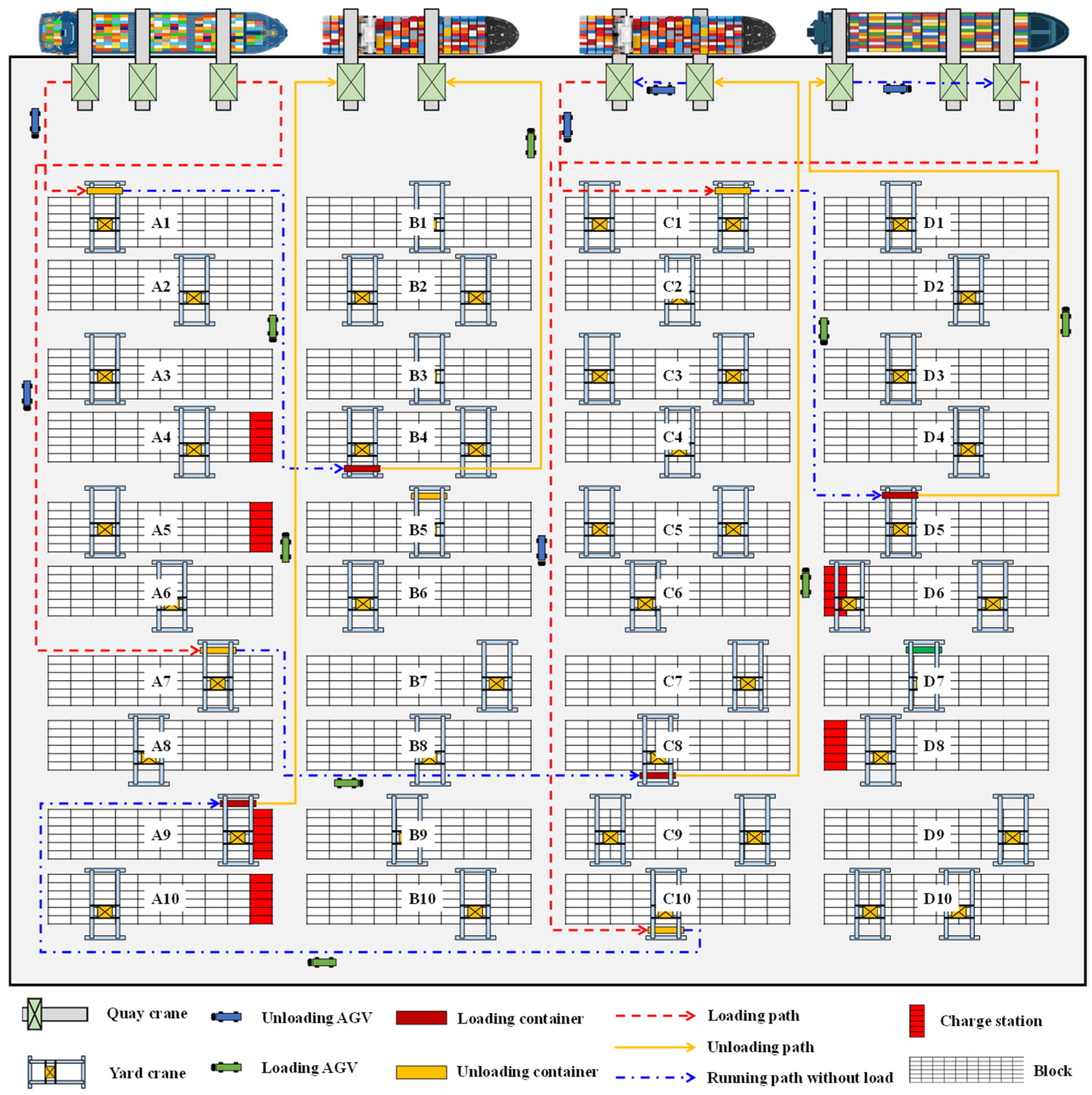

3. Development of the AGV Scheduling System

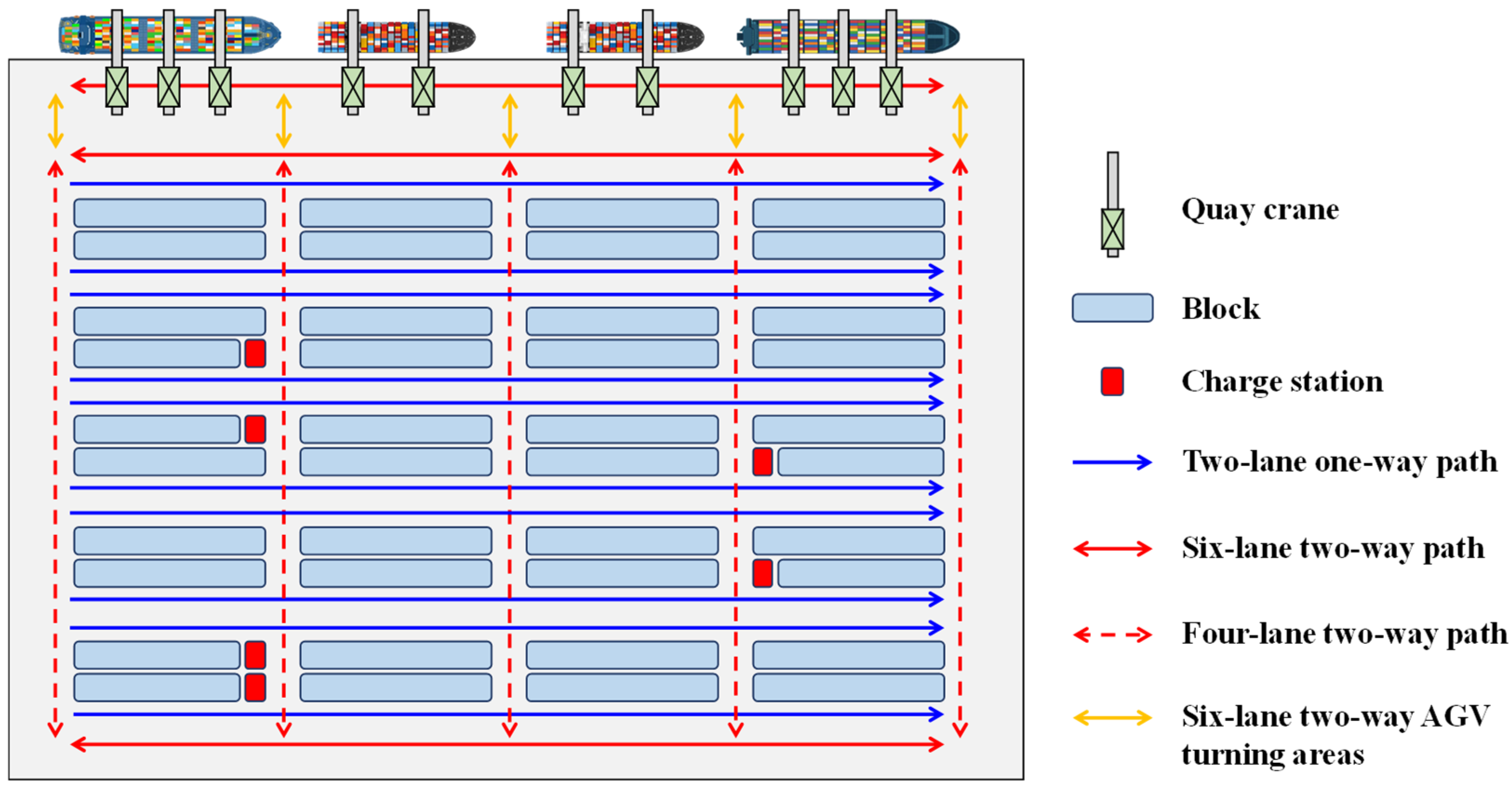

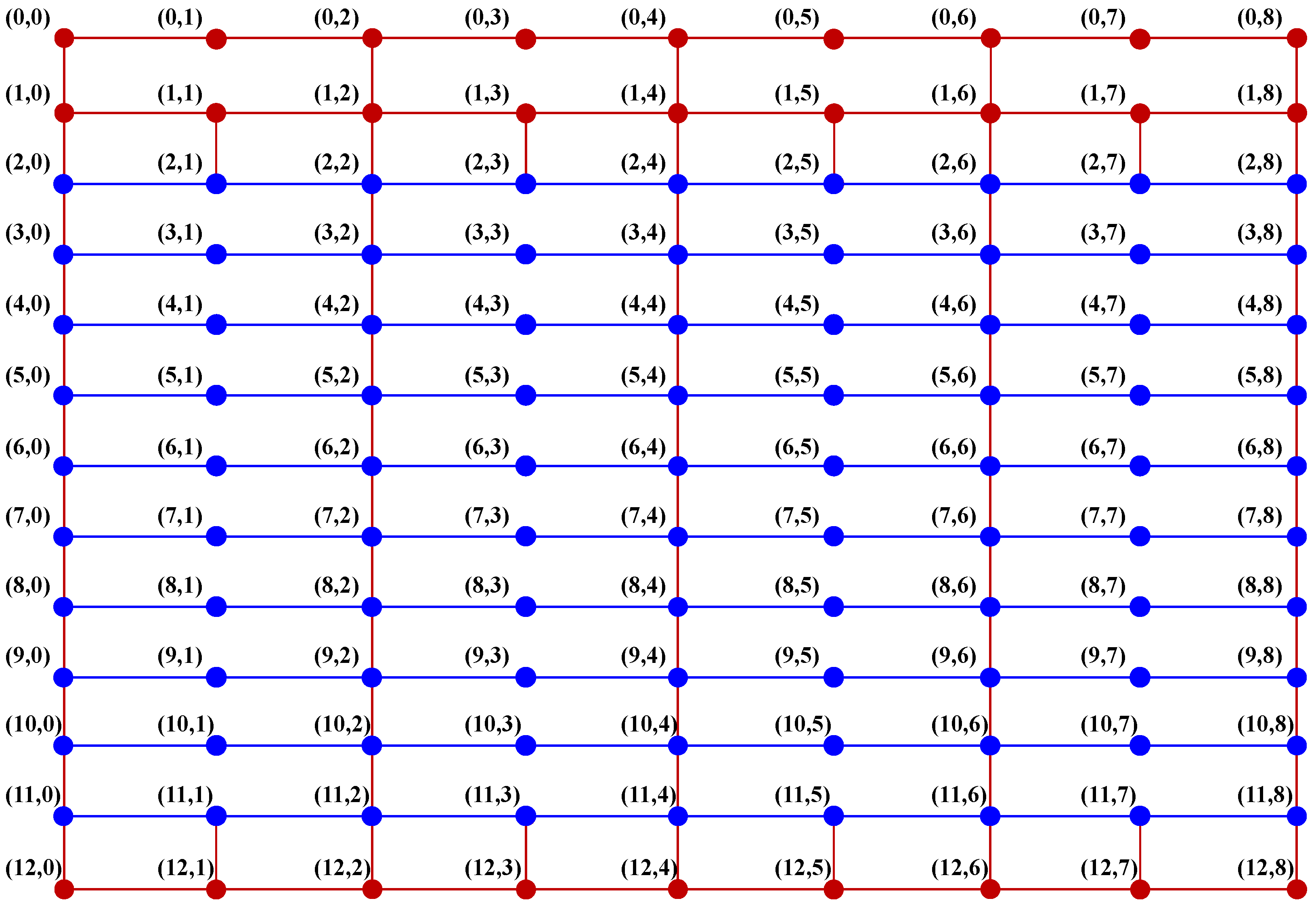

3.1. Problem Statement

- (1)

- Over a short rolling horizon, the quantities, operational sequences, and estimated handling durations of container tasks at each berth and block are known in advance by the terminal operating system. This is consistent with the actual operating situation. This assumption enables the proposed framework to focus on real-time operational decisions.

- (2)

- The destination blocks for unloading containers and target berths for loading containers are predetermined in a short time window. This assumption is also consistent with real-world container terminal operations. For problems with dynamic yard space allocation plans, the proposed decision-making framework may need redesign to jointly optimize block assignment and AGV scheduling or to incorporate destination updates as uncertain events in the rolling horizon execution.

- (3)

- At the real-time operational level, each AGV is assumed to run with a constant average speed on each path segment, so that the transport time between two adjacent nodes is pre-specified. Detailed acceleration/deceleration and turning effects at the vehicle control level are omitted.

- (4)

- AGVs are all powered by Li-ion batteries. To support real-time operational-level scheduling, the battery state-of-charge (SOC) dynamics are approximated by linear charging and discharging characteristics within the operational SOC range considered in this study (40–100%).

- (5)

- Quay cranes, yard cranes, and AGVs can each handle only one container at a time. This assumption is widely accepted in the area of container terminal operations.

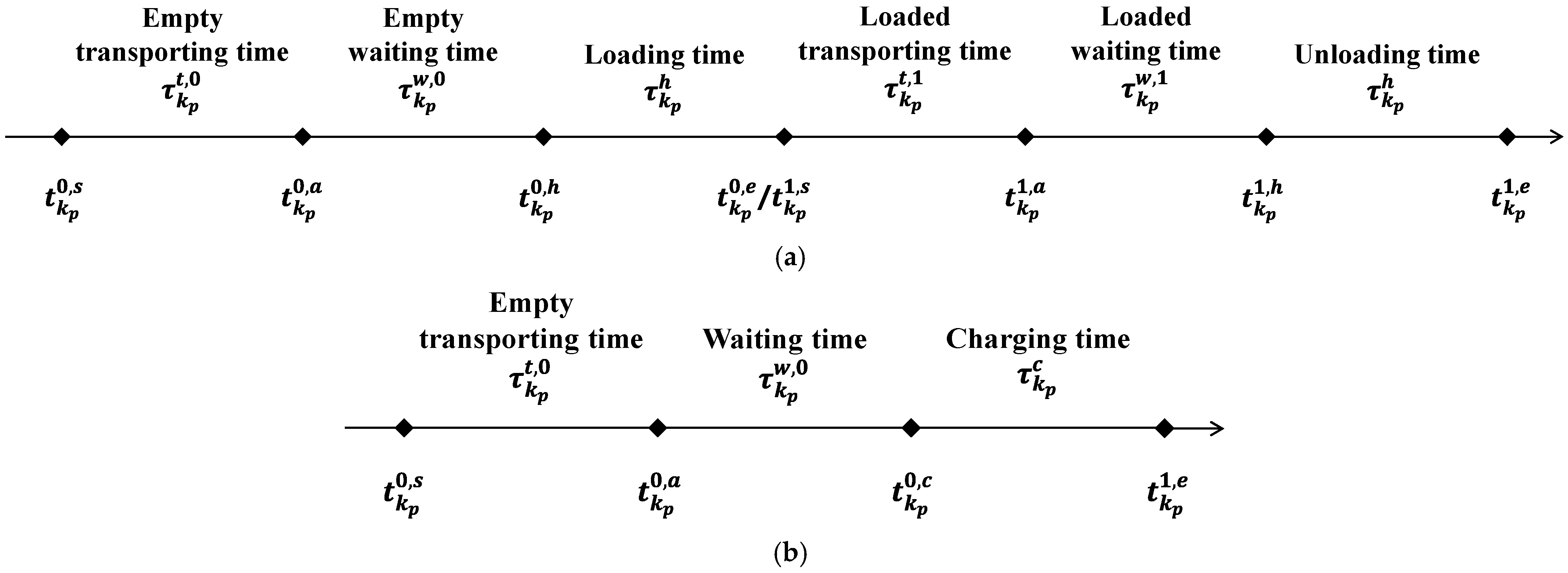

3.2. AGV Scheduling State Transition

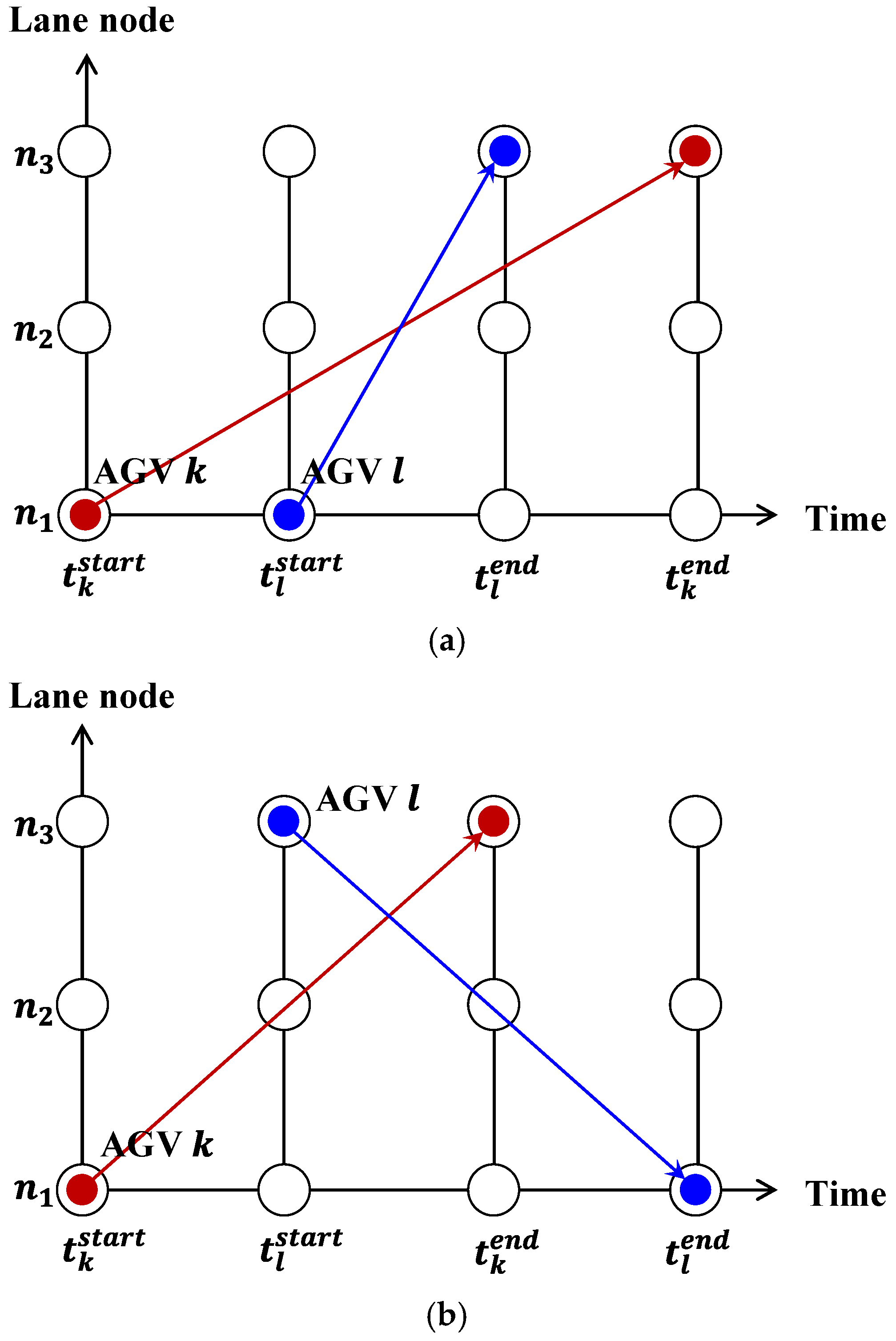

3.3. Path Conflict Detection

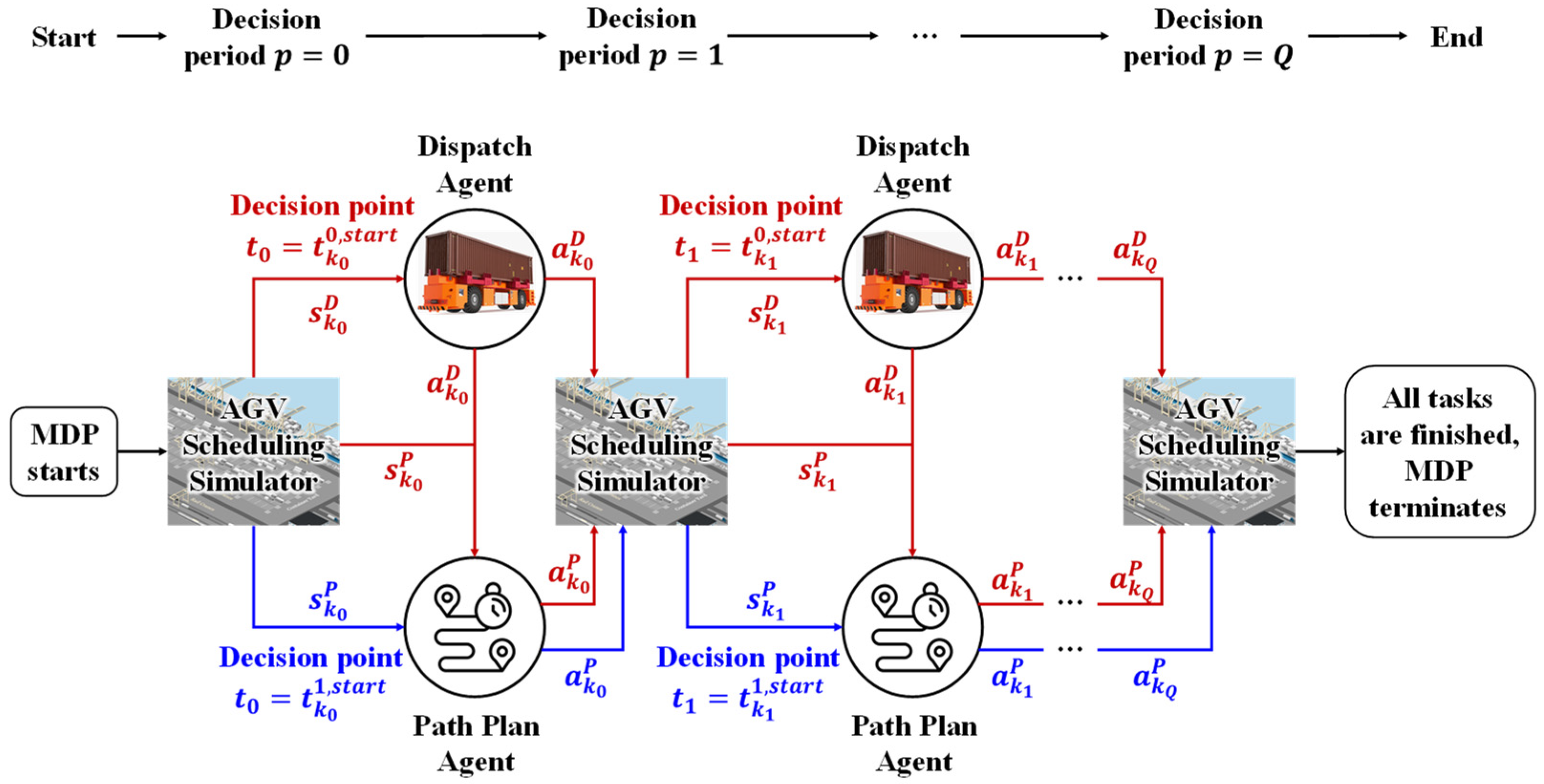

3.4. Simulator for AGV Scheduling System

| Algorithm 1 Simulation process of AGV scheduling system | |

| Initialization: loading tasks in blocks, unloading tasks at berths, AGV position and power level, decision period , . | |

| 1: | While not : |

| 2: | If any loaded AGV arrives at its destination: # No decision is needed. |

| 3: | Waiting for loading or stacking operation. |

| 4: | Execute loading or stacking operation. |

| 5: | Update the state of AGV to idle. |

| 6: | Else if any empty AGV arrives at its destination: # Path plan decision is needed. |

| 7: | Waiting for unloading or retrieving operation. |

| 8: | Execute unloading or retrieving operation. |

| 9: | Update the state of AGV to transporting, update arrive time and destination. |

| 10: | Generate transporting path, and select conflict-free path lane. |

| 11: | |

| 12: | Else: # Dispatch and path plan decisions are needed. |

| 13: | Generate assignment decision (transporting or charging) for AGV . |

| 14: | Update arrive time and destination of AGV . |

| 15: | Generate transporting path, and select conflict-free path lane. |

| 16: | If the AGV is assigned to transport: |

| 17: | Update the state of AGV to transporting. |

| 18: | Else: |

| 19: | Update the state of AGV to charging, update the charging time and charging end time. |

| 20: | End if |

| 21: | |

| 22: | End if |

| 23: | If all loading and unloading tasks are finished: |

| 24: | |

| 25: | End if |

| 26: | End while |

4. Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning Approach

4.1. Multi-Agent MDP for AGV Scheduling System

4.1.1. Agents

4.1.2. States

- (1)

- AGV dispatching state

- (2)

- Path planning state

4.1.3. Actions

4.1.4. Reward Functions

- (1)

- Global reward

- (2)

- Individual reward

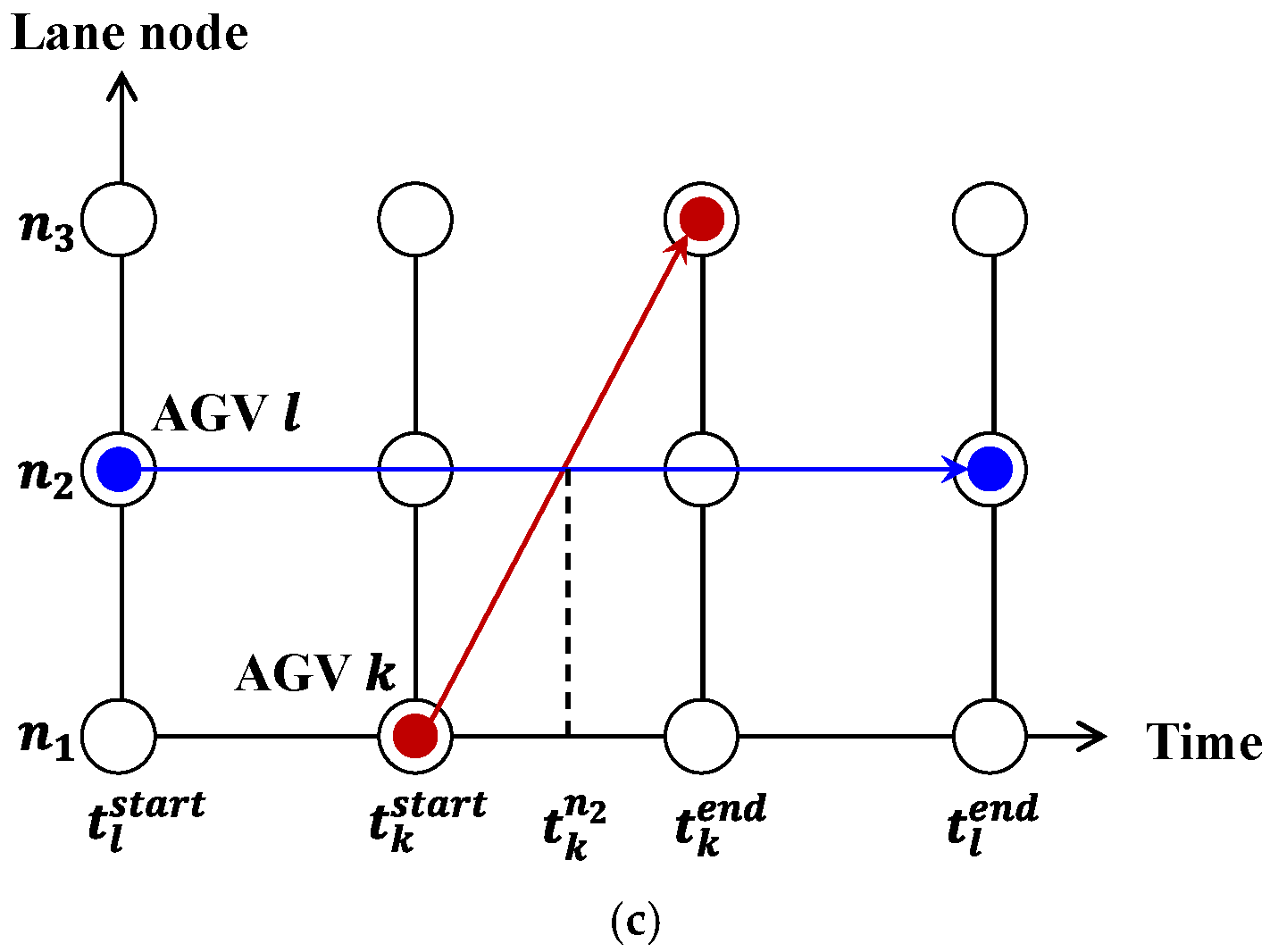

4.1.5. Multi-Agent Learning Framework

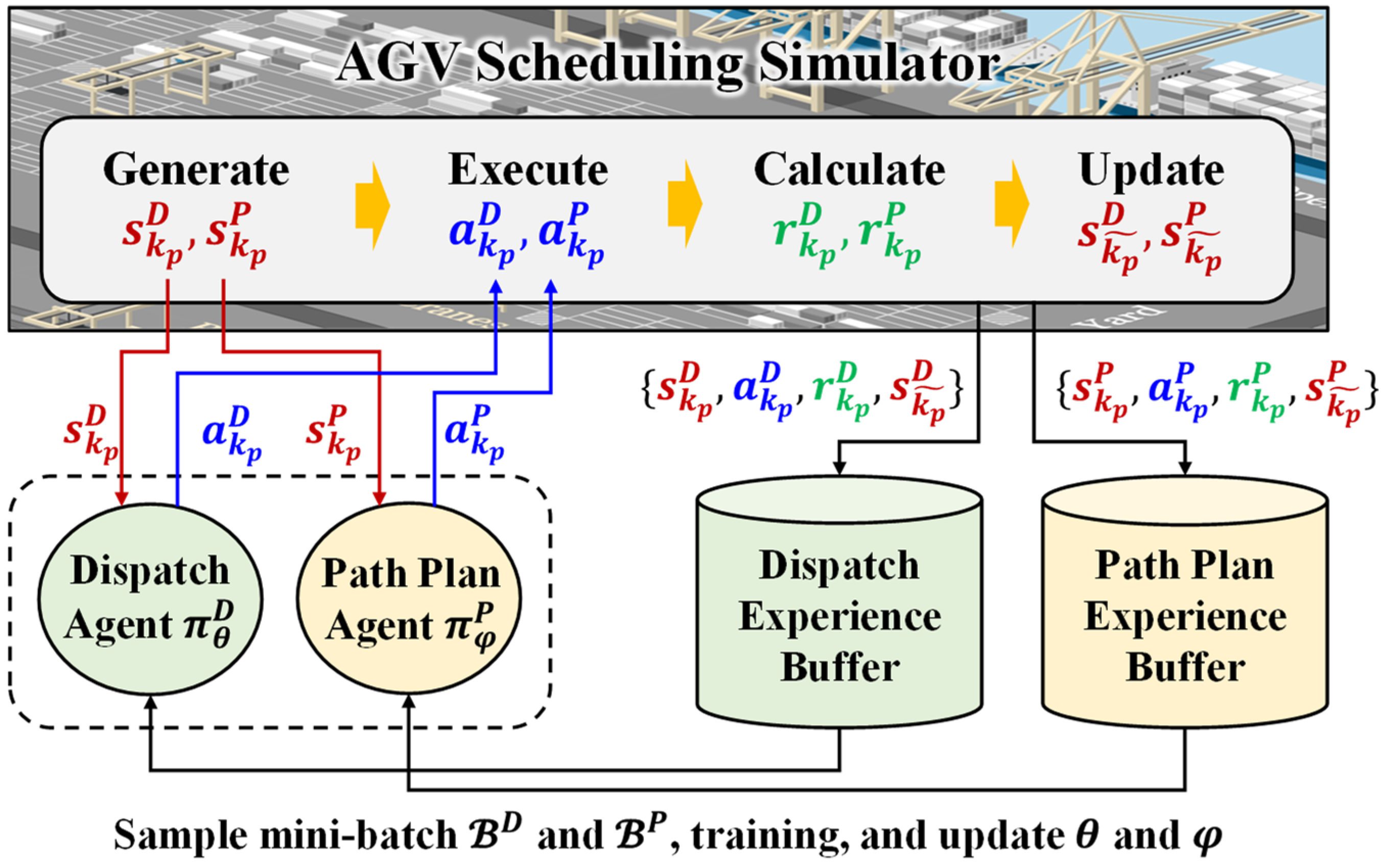

4.2. The MDP-Driven Decision-Making Framework of the AGV Scheduling System

4.3. Training Algorithm with Proximal Policy Optimization

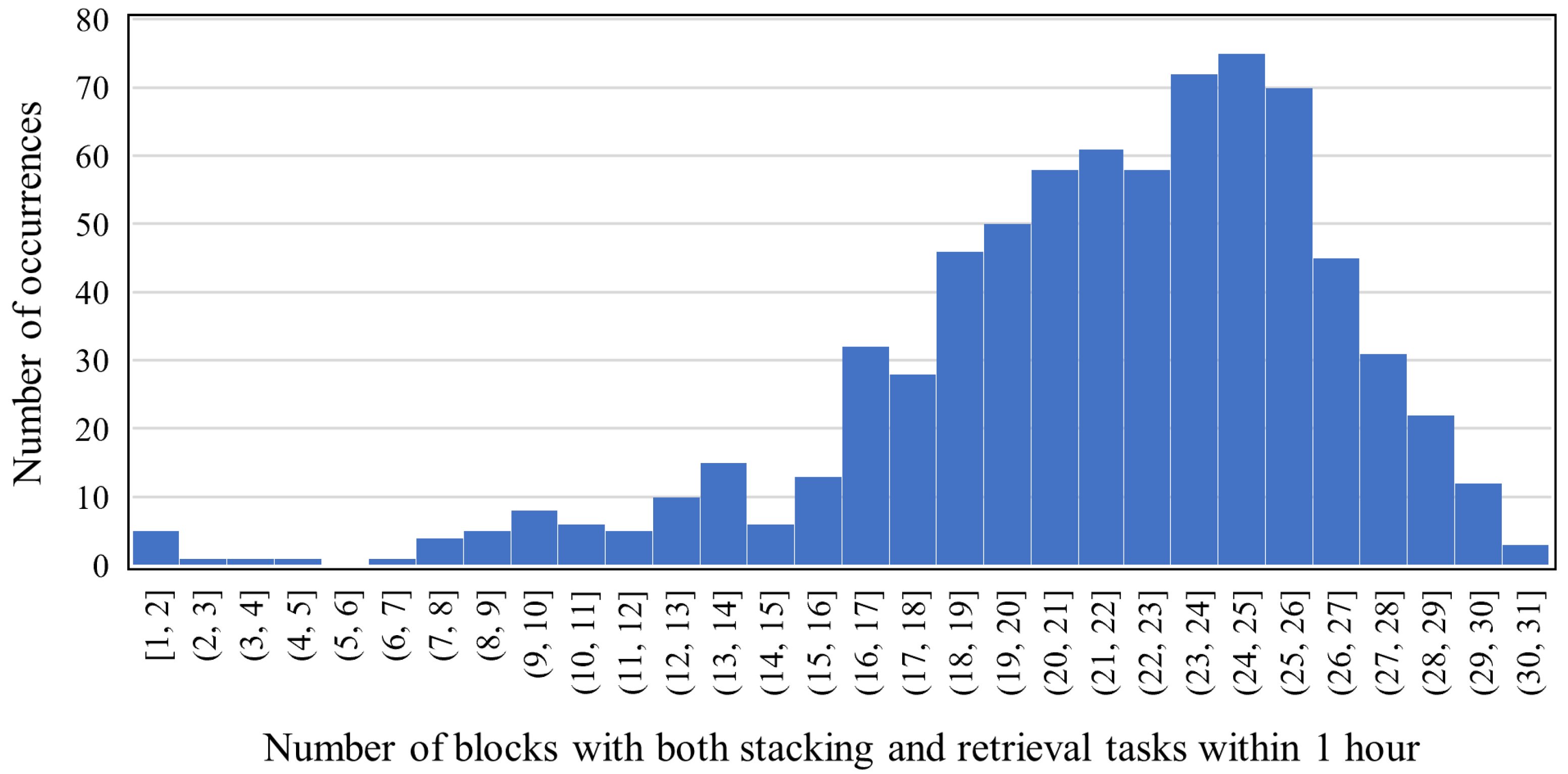

5. Numerical Experiments and Application Analyses

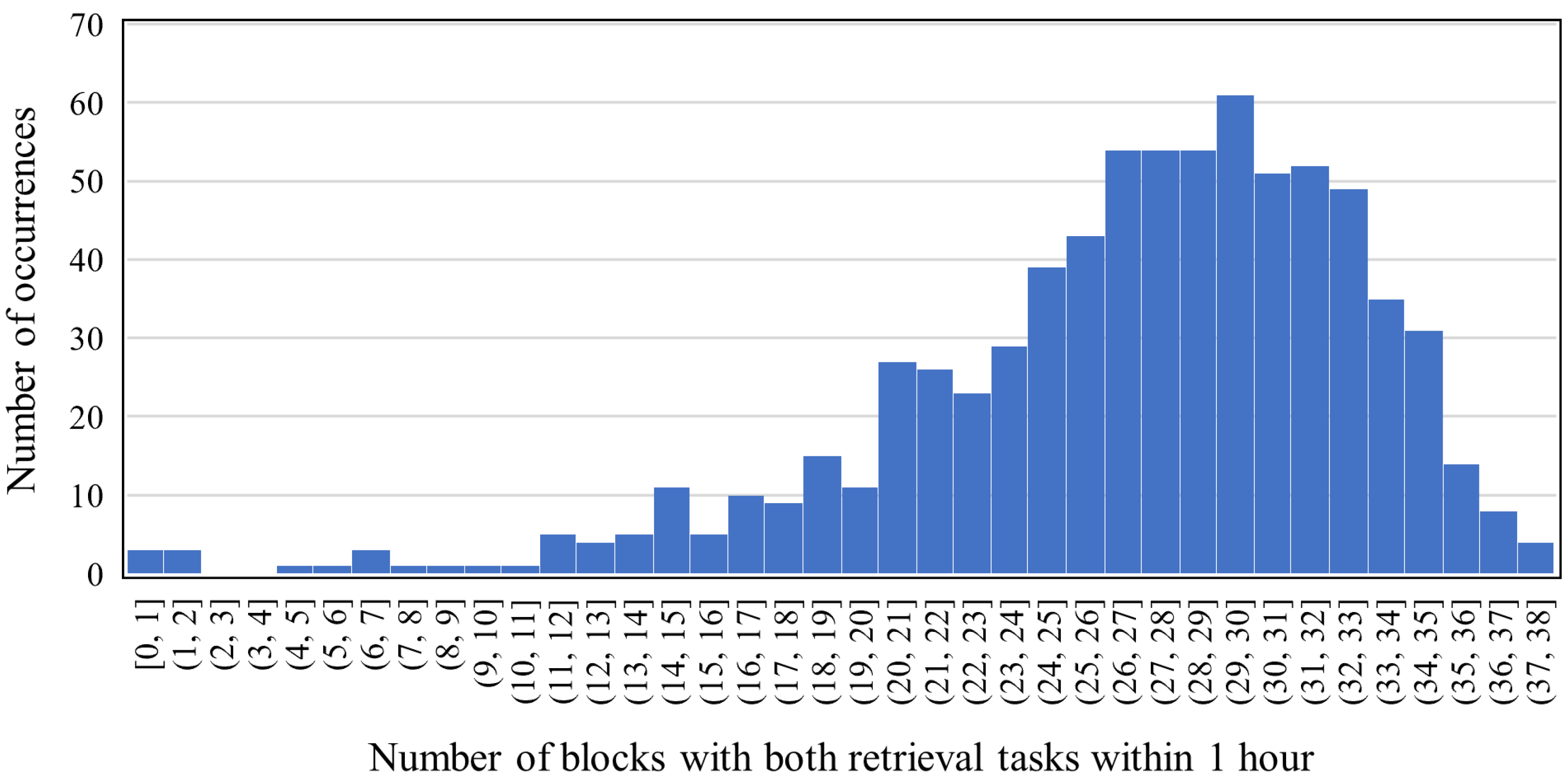

5.1. Scenarios Setting

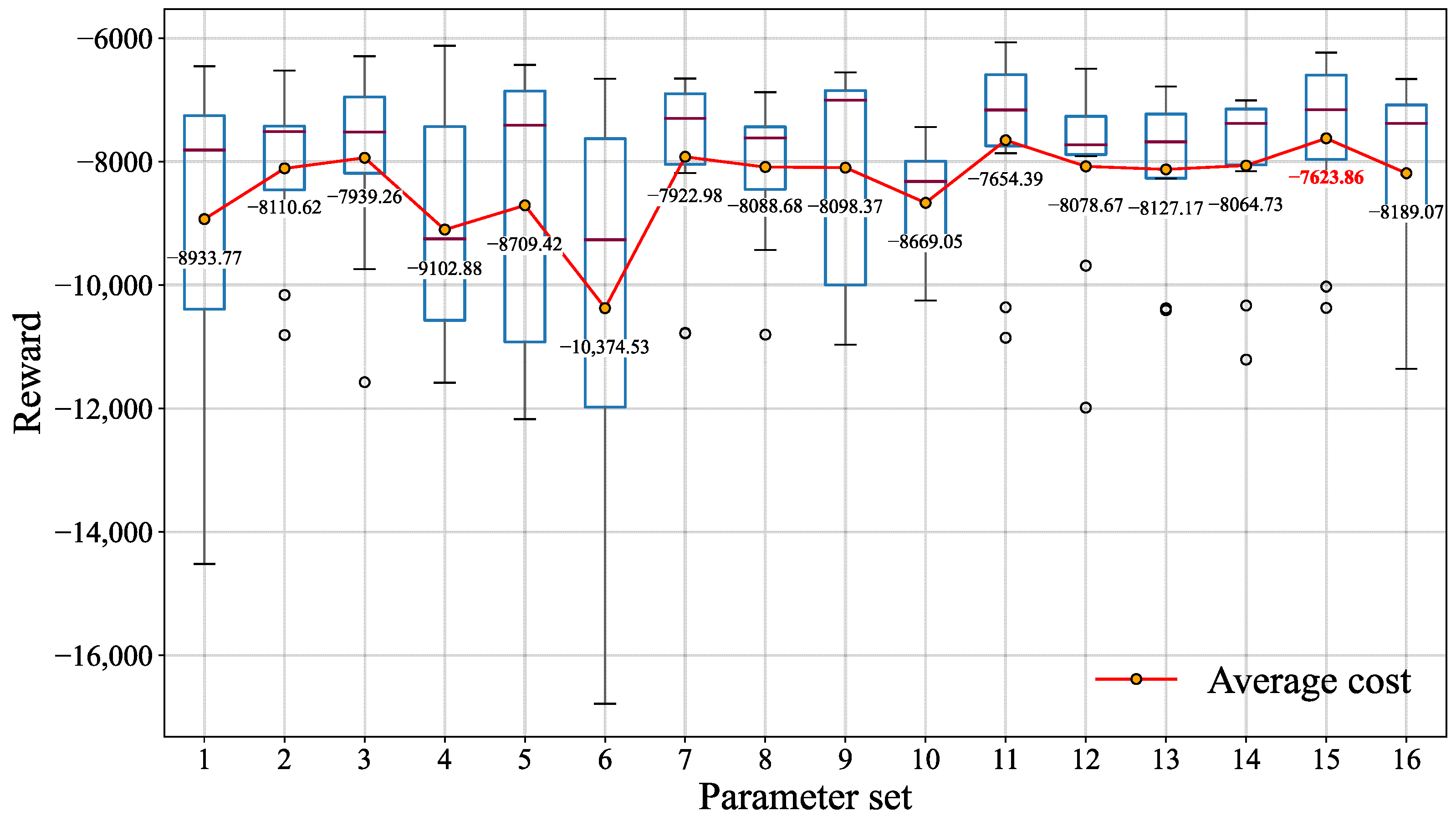

5.2. Parameter Tuning Test

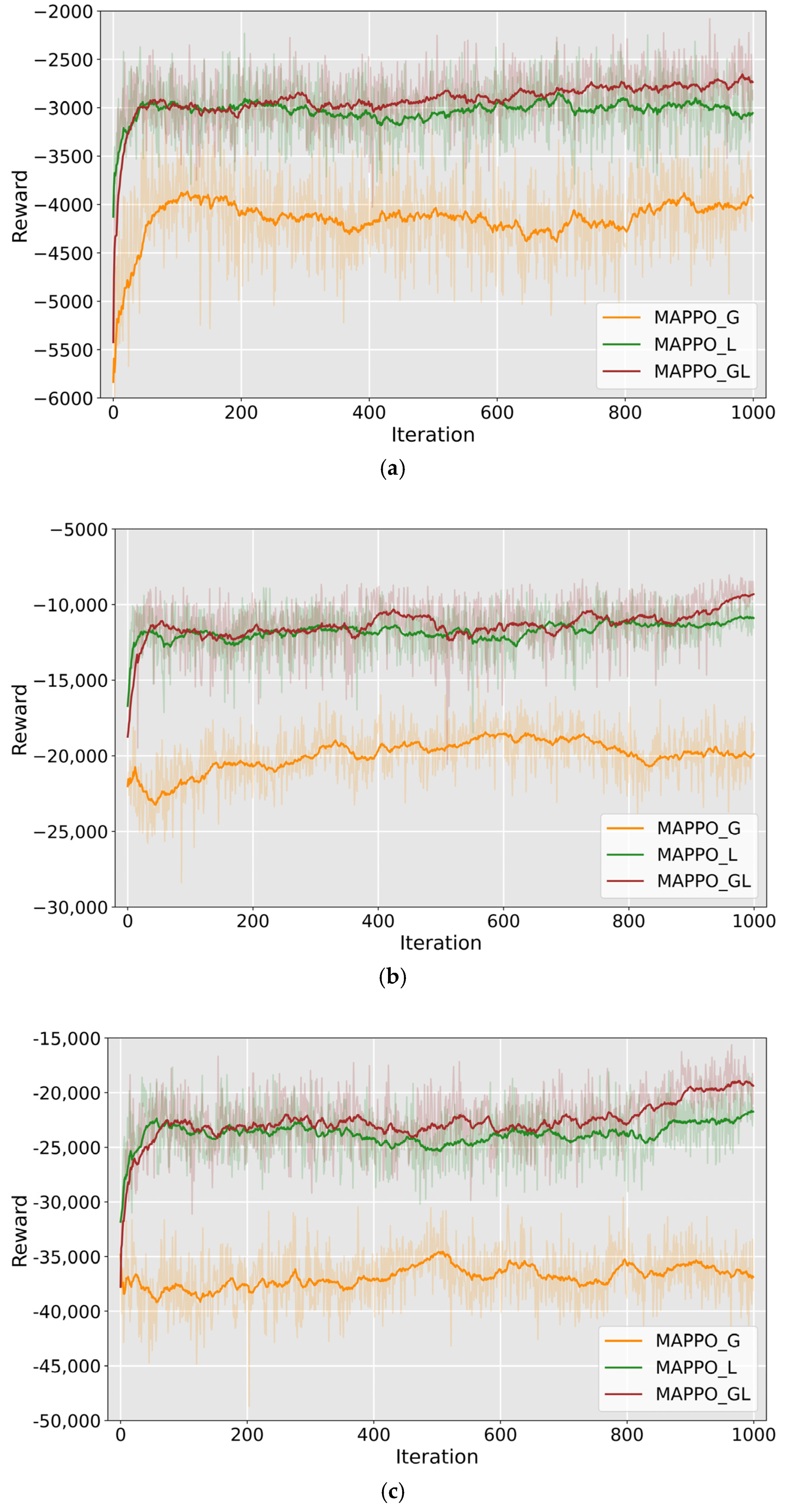

5.3. Experiment on Different Reward Function

5.4. Comparison with Benchmark Scheduling Strategies

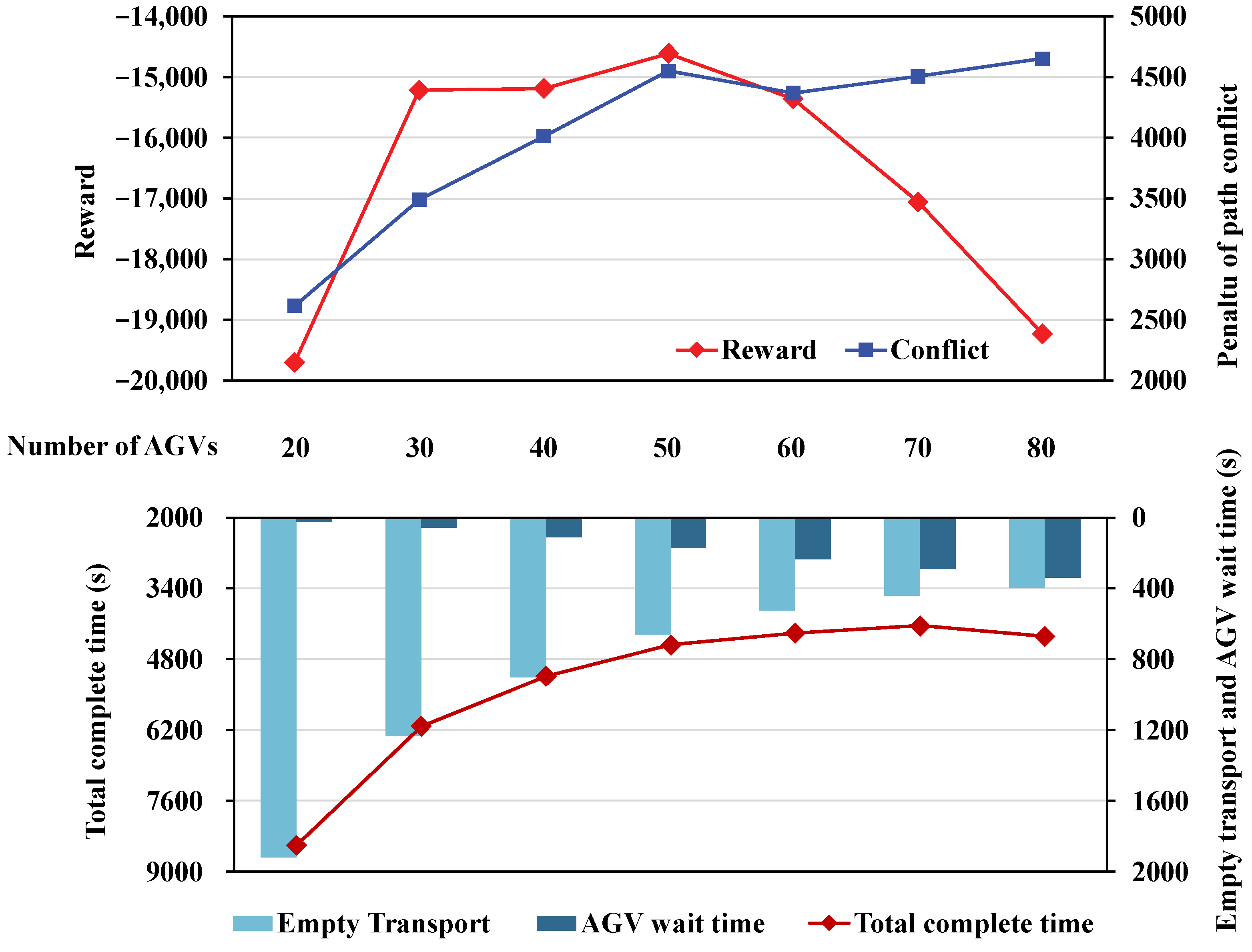

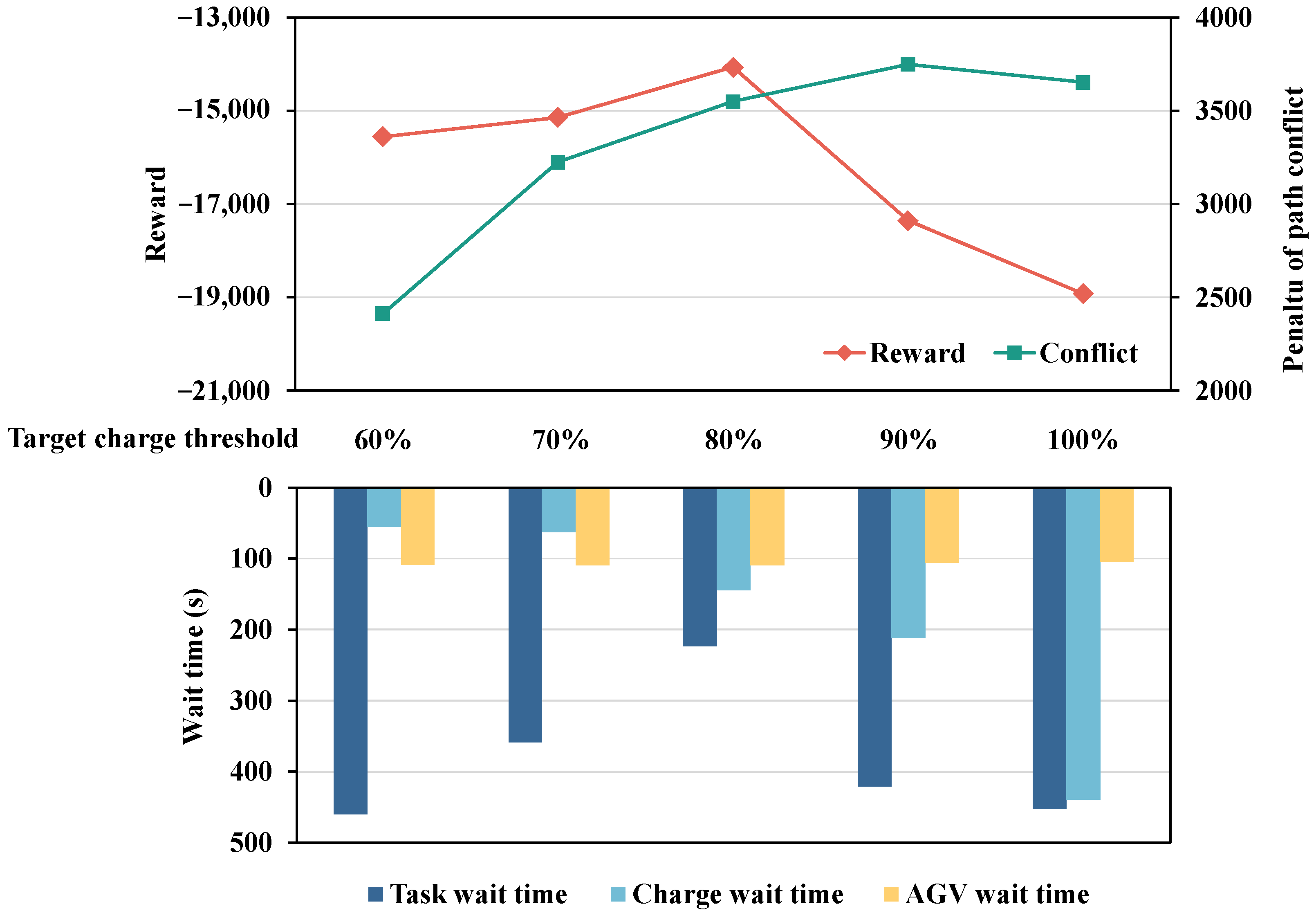

5.5. Application Analysis on AGV Configuration and Target Charge Threshold

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, J.; Ye, J.; Zhuang, C.; Qin, Q.; Shu, Y. Liner shipping alliance management: Overview and future research directions. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2022, 219, 106039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Zhou, S.; Kang, J. Knowledge mapping analysis of resilient shipping network using CiteSpace. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 244, 106775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhuang, C.; Xu, H.; Xu, L.; Ye, S.; Rangel-Buitrago, N. Collaborative management evaluation of container shipping alliance in maritime logistics industry: CKYHE case analysis. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2022, 225, 106176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, J.; Zhou, S.; Liu, A. Slot co-chartering and capacity deployment optimization of liner alliances in containerized maritime logistics industry. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2023, 56, 101986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhou, Y.; Pan, E. A Two-stage Stochastic Programming for AGV scheduling with random tasks and battery swapping in automated container terminals. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2023, 174, 103110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Chen, C.-H.; Chang, D. A machine learning-based approach for multi-agv dispatching at automated container terminals. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Ren, H.; Xu, F.; Yang, X.; Meng, Y. Bi-objective integrated scheduling of quay cranes and automated guided vehicles. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Liu, H.; Wang, T.; Chew, E.P.; Lee, L.H.; Tan, K.C. Integrated automated guided vehicle dispatching and equipment scheduling with speed optimization. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2023, 169, 102993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gu, Y.; Tian, Y. Integrated optimization of automated guided vehicles and yard cranes considering charging constraints. Eng. Optim. 2024, 56, 1748–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Liu, H.; Wang, T.; Lin, Y.H.; Chew, E.P.; Tan, K.C.; Li, H. AGV charging scheduling with capacitated charging stations at automated ports. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2025, 197, 104080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, M. Clean Energy Self-Consistent Systems for Automated Guided Vehicle (AGV) Logistics Scheduling in Automated Ports. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Hu, H.; Cheng, C. Collaborative scheduling of handling equipment in automated container terminals with limited AGV-mates considering energy consumption. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 65, 103133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Yang, X.; Xiao, S.; Wang, F. Anti-conflict AGV path planning in automated container terminals based on multi-agent reinforcement learning. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Gao, J.; Li, L.; Wang, Y. Control optimisation of automated guided vehicles in container terminal based on Petri network and dynamic path planning. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2022, 104, 108471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.; Fan, H. Dynamic scheduling and path planning of automated guided vehicles in automatic container terminal. IEEECAA J. Autom. Sin. 2022, 9, 2005–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Tang, C.; Claramunt, C.; Hu, X.; Zhou, P. Geometric A-star algorithm: An improved A-star algorithm for AGV path planning in a port environment. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 59196–59210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Qi, L.; Luan, W.; Guo, X.; Ma, H. Load-in-load-out AGV route planning in automatic container terminal. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 157081–157088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shi, S.; Chen, Z.; Wang, T.; Miao, L.; Song, H. Optimizing Port Multi-AGV Trajectory Planning through Priority Coordination: Enhancing Efficiency and Safety. Axioms 2023, 12, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Sun, S.; Xu, B. Path planning and trajectory tracking for autonomous obstacle avoidance in automated guided vehicles at automated terminals. Axioms 2023, 13, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zeng, Q. A branch-and-bound approach for AGV dispatching and routing problems in automated container terminals. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 166, 107968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Fan, L.; Jia, S. A hierarchical solution framework for dynamic and conflict-free AGV scheduling in an automated container terminal. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2024, 165, 104724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, L. A three stage optimal scheduling algorithm for AGV route planning considering collision avoidance under speed control strategy. Mathematics 2022, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, P.; Zhong, Y.; Hu, J.; Fan, C.; Chen, X. Digital-twin-driven AGV scheduling and routing in automated container terminals. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhu, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, S. Multiple equipment scheduling and AGV trajectory generation in U-shaped sea-rail intermodal automated container terminal. Measurement 2023, 206, 112262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marugan, A.P. Applications of Reinforcement Learning for maintenance of engineering systems: A review. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2023, 183, 103487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyyedabbasi, A. A reinforcement learning-based metaheuristic algorithm for solving global optimization problems. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2023, 178, 103411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syavasya, C.; Muddana, A.L. Optimization of autonomous vehicle speed control mechanisms using hybrid DDPG-SHAP-DRL-stochastic algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2022, 173, 103245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, Y. Research on intelligent dynamic scheduling algorithm for automated guided vehicles in container terminal based on deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation (ICMA), Harbin, China, 6–9 August 2023; pp. 2406–2412. [Google Scholar]

- Che, A.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, C. Multi-agent deep reinforcement learning for recharging-considered vehicle scheduling problem in container terminals. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 16855–16868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, S.; Zhao, J.; Wu, H.; Xian, J.; Montewka, J. Autonomous port management based AGV path planning and optimization via an ensemble reinforcement learning framework. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 251, 107087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Liang, C.; Wang, Y.; Shi, J.; Lim, G. Multi-AGV dynamic scheduling in an automated container terminal: A deep reinforcement learning approach. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhuo, X.; Lian, Z.; Zhou, X. A Reinforcement Learning—Based AGV Scheduling for Automated Container Terminals With Resilient Charging Strategies. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 19, e70027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Huang, Z.; Xiang, X.; Liu, X. Real-time AGV scheduling optimisation method with deep reinforcement learning for energy-efficiency in the container terminal yard. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 7722–7742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drungilas, D.; Kurmis, M.; Senulis, A.; Lukosius, Z.; Andziulis, A.; Januteniene, J.; Bogdevičius, M.; Jankunas, V.; Vozňák, M. Deep reinforcement learning based optimization of automated guided vehicle time and energy consumption in a container terminal. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 67, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Ding, P.; Bi, Y.; Qiu, J. A Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach for Multiple AGVs Scheduling in Automated Container Terminals. In Proceedings of the 2024 China Automation Congress (CAC), Qingdao, China, 1–3 November 2024; pp. 3564–3569. [Google Scholar]

- Hau, B.M.; You, S.-S.; Kim, H.-S. Efficient routing for multiple AGVs in container terminals using hybrid deep learning and metaheuristic algorithm. Ain. Shams. Eng. J. 2025, 16, 103468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhuang, Z.; Qin, W.; Fang, H.; Lan, S.; Yang, C.; Tian, Y. A reinforcement learning approach for integrated scheduling in automated container terminals. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 7–10 December 2022; pp. 1182–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Liu, S.; Li, C.; Han, B.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, J. AGV path planning and optimization with deep reinforcement learning model. In Proceedings of the 2023 7th International Conference on Transportation Information and Safety (ICTIS), Xi’an, China, 4–6 August 2023; pp. 1859–1863. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Q.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, J.; Wang, C. A self-attention-based deep reinforcement learning approach for AGV dispatching systems. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 35, 7911–7922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, R.; Gong, W. Deep reinforcement learning-based memetic algorithm for energy-aware flexible job shop scheduling with multi-AGV. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 189, 109917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadpour, M.; Allani, B.; Kelouwani, S.; Ouameur, M.A.; Zeghmi, L.; Amamou, A.; Bahmanabadi, H. Optimal charging scheduling for Indoor Autonomous Vehicles in manufacturing operations. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 62, 102804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Liu, T.; Kumar, P.R.; Han, X. A reinforcement learning-based hyper-heuristic for AGV task assignment and route planning in parts-to-picker warehouses. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2024, 185, 103518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L. A route and speed optimization model to find conflict-free routes for automated guided vehicles in large warehouses based on quick response code technology. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 52, 101604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Zhang, G.; Lu, X.; Wang, H.; Sheng, C.; Sun, L. Reinforcement learning method based on sample regularization and adaptive learning rate for AGV path planning. Neurocomputing 2025, 614, 128820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, P.-H.; Chen, S.-Y.; Feng, P.-H.; Chang, C.-W.; Huang, C.-J.; Peng, C.-C. Reinforcement learning-based fuzzy controller for autonomous guided vehicle path tracking. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 65, 103180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, X.; Gao, L. Real-time scheduling for production-logistics collaborative environment using multi-agent deep reinforcement learning. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 65, 103216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, C.; Lu, Y. Research on AGV path tracking method based on global vision and reinforcement learning. Sci. Prog. 2023, 106, 00368504231188854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, G.; Tang, Y.M.; Leung, E.K.; Tong, P. Integrated reinforcement learning of automated guided vehicles dynamic path planning for smart logistics and operations. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2025, 196, 104008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, R.; Sturtevant, N.; Felner, A.; Koenig, S.; Ma, H.; Walker, T.; Li, J.; Atzmon, D.; Cohen, L.; Kumar, T.K.; et al. Multi-agent pathfinding: Definitions, variants, and benchmarks. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Combinatorial Search, Napa, CA, USA, 16–17 July 2019; pp. 151–158. [Google Scholar]

- Sharon, G.; Stern, R.; Felner, A.; Sturtevant, N.R. Conflict-based search for optimal multi-agent pathfinding. Artif. Intel. 2015, 219, 40–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyarski, E.; Felner, A.; Stern, R.; Sharon, G.; Betzalel, O.; Tolpin, D.; Shimony, E. Icbs: The improved conflict-based search algorithm for multi-agent pathfinding. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Combinatorial Search, Ein Gedi, Israel, 11–13 June 2015; pp. 223–225. [Google Scholar]

- Surynek, P. Problem Compilation for Multi-Agent Path Finding: A Survey. In Proceedings of the Thirty-First International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vienna, Austria, 23–29 July 2022; pp. 5615–5622. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T.; Fan, W. Enhancing robustness of deep reinforcement learning based adaptive traffic signal controllers in mixed traffic environments through data fusion and multi-discrete actions. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 14196–14208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Agrawal, S. Discretizing continuous action space for on-policy optimization. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; pp. 5981–5988. [Google Scholar]

| Notation | Definition |

|---|---|

| Index of AGV. | |

| Index of decision period. | |

| Index of task. | |

| The AGV that needs to generate decisions in decision period . | |

| Index of the -th node on a given path. | |

| Arrival time at node of AGV . | |

| Empty transporting start time of AGV . | |

| Empty arrival time at block and berth of AGV . | |

| Empty handling start time at block and berth of AGV . | |

| Empty handling end time at block and berth of AGV . | |

| Arrival, charging start, and charging end time of AGV . | |

| Loaded transporting start time at block and berth of AGV . | |

| Loaded arrival time at block and berth of AGV . | |

| Loaded handling start time at block and berth of AGV . | |

| Loaded handling end time at block and berth of AGV . | |

| Required empty transporting and waiting time for AGV . | |

| Required loaded transporting and waiting time for AGV . | |

| Required loading and unloading time for AGV . | |

| Required stacking and retrieving time for AGV . | |

| Required charging time for AGV . | |

| Remaining power of AGV . | |

| Target battery level to be reached during charging. | |

| The amount of energy charged per unit time. | |

| The start node of . | |

| The direction of at start node. | |

| The target node of . | |

| The direction of at target node. | |

| The first queuing task that is assigned to at when arrives. | |

| Time when handling facility becomes idle at . | |

| The planned handling time of task . | |

| The shortest path algorithm with known start node , start direction , and target node . | |

| The shortest path of AGV for empty transporting and loaded transporting. |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of blocks | 40 |

| Number of berths | 4 |

| Number of charge stations | 6 |

| Number of charge facilities in each charge station | 2 |

| Number of lanes in handling path aside block | 2 |

| Number of lanes in handling path at berth | 6 |

| Number of lanes in transporting path between block and berth | 6 |

| Number of lanes in transporting path inner block | 4 |

| Number of AGVs | 40 |

| Horizontal transporting time of AGV between adjacent blocks (s) | 40 |

| Vertical transporting time of AGV between adjacent blocks (s) | 4 |

| Power consumption of AGV per second (%) | 0.023 |

| Charging power of AGV per second (%) | 0.042 |

| Minimum remaining power of AGV for transporting (%) | 18 |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4000 | ||

| 15 | 1000 | ||

| 1 | 10,000 | ||

| 2 | 1000 | ||

| 5 | 10 |

| Scenario | Number of Tasks in Each Block | Number of Tasks at Each Berth |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | [0, 2] | [0, 8] |

| S2 | [0, 6] | [0, 24] |

| S3 | [0, 10] | [0, 40] |

| Set | Batch Size | Mini-Batch Size | Learning Rate of Policy Network | Learning Rate of Value Network | Epsilon | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | P | D | P | D | P | D | P | ||

| 1 | 1024 | 4096 | 32 | 128 | 1 × 10−3 | 1 × 10−3 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−4 | 0.1 |

| 2 | 1024 | 4096 | 32 | 128 | 1 × 10−3 | 1 × 10−3 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−4 | 0.2 |

| 3 | 1024 | 4096 | 32 | 128 | 1 × 10−3 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−5 | 0.1 |

| 4 | 1024 | 4096 | 32 | 128 | 1 × 10−3 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−5 | 0.2 |

| 5 | 1024 | 4096 | 32 | 128 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−3 | 1 × 10−5 | 1 × 10−4 | 0.1 |

| 6 | 1024 | 4096 | 32 | 128 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−3 | 1 × 10−5 | 1 × 10−4 | 0.2 |

| 7 | 1024 | 4096 | 32 | 128 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−5 | 1 × 10−5 | 0.1 |

| 8 | 1024 | 4096 | 32 | 128 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−5 | 1 × 10−5 | 0.2 |

| 9 | 2048 | 8192 | 64 | 256 | 1 × 10−3 | 1 × 10−3 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−4 | 0.1 |

| 10 | 2048 | 8192 | 64 | 256 | 1 × 10−3 | 1 × 10−3 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−4 | 0.2 |

| 11 | 2048 | 8192 | 64 | 256 | 1 × 10−3 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−5 | 0.1 |

| 12 | 2048 | 8192 | 64 | 256 | 1 × 10−3 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−5 | 0.2 |

| 13 | 2048 | 8192 | 64 | 256 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−3 | 1 × 10−5 | 1 × 10−4 | 0.1 |

| 14 | 2048 | 8192 | 64 | 256 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−3 | 1 × 10−5 | 1 × 10−4 | 0.2 |

| 15 | 2048 | 8192 | 64 | 256 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−5 | 1 × 10−5 | 0.1 |

| 16 | 2048 | 8192 | 64 | 256 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−5 | 1 × 10−5 | 0.2 |

| MAPPO | Cl_Dn | Cl_Dl | Cr0.4_Dn | Cr0.4_Dl | Cr0.6_Dn | Cr0.6_Dl | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reward | −16,568.9 | −23,182.4 | −19,389.9 | −22,999.7 | −17,965.5 | −25,483.6 | −20,322.9 |

| Gap | \ | 39.9% | 17.0% | 38.8% | 8.4% | 53.8% | 22.7% |

| CT | 5894.0 | 5457.5 | 5820.9 | 5613 | 5816.5 | 5843.7 | 6108.7 |

| CP | 5177.5 | 6165.0 | 6785.0 | 5810.0 | 6502.5 | 6212.5 | 7320.0 |

| ET | 980.5 | 747.1 | 916.4 | 821.8 | 944.6 | 997.5 | 1138.4 |

| CW | 223.8 | 201.9 | 350.3 | 95.8 | 89.7 | 113.1 | 124.0 |

| HW | 126.4 | 126.7 | 125.5 | 101.7 | 104.0 | 76.2 | 77.5 |

| TD | 209.7 | 636.7 | 257.7 | 671.5 | 269.7 | 780.8 | 332.1 |

| CN | 22.4 | 18.1 | 22.8 | 31.2 | 32.5 | 58.2 | 64.2 |

| ST | 85.9 | 11.5 | 6.9 | 10.6 | 7.2 | 12.1 | 8.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zuo, T.; Liu, H.; Yang, S.; Wang, W.; Peng, Y.; Wang, R. A Reinforcement Learning Method for Automated Guided Vehicle Dispatching and Path Planning Considering Charging and Path Conflicts at an Automated Container Terminal. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010055

Zuo T, Liu H, Yang S, Wang W, Peng Y, Wang R. A Reinforcement Learning Method for Automated Guided Vehicle Dispatching and Path Planning Considering Charging and Path Conflicts at an Automated Container Terminal. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(1):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010055

Chicago/Turabian StyleZuo, Tianli, Huakun Liu, Shichun Yang, Wenyuan Wang, Yun Peng, and Ruchong Wang. 2026. "A Reinforcement Learning Method for Automated Guided Vehicle Dispatching and Path Planning Considering Charging and Path Conflicts at an Automated Container Terminal" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 1: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010055

APA StyleZuo, T., Liu, H., Yang, S., Wang, W., Peng, Y., & Wang, R. (2026). A Reinforcement Learning Method for Automated Guided Vehicle Dispatching and Path Planning Considering Charging and Path Conflicts at an Automated Container Terminal. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010055