Abstract

This study addresses deviations between observed nonstationary tides and physical-model results caused by multiple indirectly observed factors. The S_TIDE framework performs well in estuaries by introducing time-varying nonequilibrium physical factors to represent tidal characteristics and is applicable to diverse nonstationary regimes. However, S_TIDE remains limited: even combined with the Enhanced Harmonic Analysis (EHA) scheme, which improves extraction of characteristic tidal levels, it still fails to capture differences between observed and harmonically analyzed tides driven by regional nonlinear processes, so tidal errors remain large. We develop a hybrid scheme coupling S_TIDE with an ensemble-learning model. The physically computed tide provides a constrained backbone; the observed–physical difference is formulated as a residual series, and the PELM ensemble learns regional tidal characteristics encoded in these residuals to provide targeted corrections. Using research-grade records from 528 tide-gauge stations of the University of Hawaii Sea Level Center (UHSLC), PELM increases tidal-simulation accuracy, yielding an average error-reduction of 45.63% across all stations; 66.10% of sites improve by more than 40%, and stations with large initial physical-tide errors improve on average by more than 65%. These results demonstrate that the Physics-Constrained Ensemble-Learning Method (PELM) scheme is highly effective and generalizable for extracting characteristic tidal levels and reducing tidal-simulation errors at the global scale.

1. Introduction

Classical harmonic analysis (CHA), one of the most widely used methods in tidal sea-level studies, estimates constituent amplitudes and phases by ordinary least squares at a set of a priori frequencies prescribed by astronomical and hydrodynamic theory. CHA originally assumes that water levels are influenced solely by tides and that the tide is strictly stationary, i.e., purely driven by celestial forcing [1]. However, all tidal time series are theoretically nonstationary. Nontidal disturbances such as wind, waves, storm surges, and sea-ice cover introduce nonstationary components into the observations. At a coarse level, the nonstationary component is small in most coastal tide-gauge records, so tides can be approximated as stationary and CHA typically performs well, with fewer than about 150 constituents explaining more than 95% of the variance. In many tidal regimes that are strongly affected by nontidal forcing, however, such as estuarine tides, internal tides, and tides in ice-covered embayments, nonstationarity becomes pronounced [2]. The performance of CHA then deteriorates markedly because its stationarity assumption is strongly violated. For example, in estuaries, hindcast and forecast water levels obtained from CHA can differ from observations by several meters [1]. For strongly nonstationary tidal records, CHA can only provide mean properties of the time-varying tide and cannot resolve interactions between tidal and nontidal processes. To investigate the internal dynamics of nonstationary tides, a variety of methods have been proposed [3], including complex demodulation (CD), the continuous wavelet transform (CWT), and short-time harmonic analysis. These approaches can represent time-varying amplitudes in both the time and frequency domains to reflect the influence of nontidal processes, but their resolution of closely spaced constituents within the same tidal band is limited [4], and they cannot adequately describe important subtidal oscillations embedded in nonstationary tides, such as estuarine tides [4].

Matte et al. [5], building on the work of Kukulka & Jay [6,7] and Jay et al. [8], proposed a tide–river flow model and modified T_TIDE [9] to develop NS_TIDE, a nonstationary analysis tool for estuarine tides. Compared with classical CHA, NS_TIDE performs markedly better in estuaries and achieves higher constituent resolution within a tidal band than CWT. It uses robust regression and directly embeds nontidal nonstationary forcings such as river discharge and offshore tidal range into the CHA basis functions [10]. As a result, NS_TIDE can quantitatively elucidate the influence of river flow and tidal forcing on the mean water level (MWL), as well as the temporal evolution of constituent amplitudes and phases. Despite its strong predictive skill, NS_TIDE still has notable limitations: its application is constrained by the availability of accurate river-discharge data and it is not readily applicable to nonstationary tides driven by other dynamical mechanisms.

Jin et al. [11] proposed Enhanced Harmonic Analysis (EHA), based on an independent point (IP) scheme and cubic-spline interpolation, and applied it to internal tides in the South China Sea to estimate time-varying harmonic parameters. However, internal-tide dynamics are highly complex and related observations are extremely sparse, which restricts the performance of EHA. Consequently, Jin et al. did not provide a clear criterion for selecting the number of IPs and were unable to explain the physical drivers of the time-varying features observed in moored current records [11]. Pan et al. [12] further used EHA, together with the widely used T_TIDE package, to develop a new tool, S_TIDE, for nonstationary tides. By analyzing hourly water-level observations at multiple stations along the Columbia River, they demonstrated that S_TIDE performs well. Unlike NS_TIDE, which is tailored to estuarine tides, EHA does not depend on explicit dynamical formulations and only assumes that tidal frequencies are known. Therefore, in principle, S_TIDE can be applied to a broad range of nonstationary tidal regimes.

In recent years, machine-learning approaches have been widely adopted in many fields [13,14,15]. For example, long short-term memory (LSTM) networks can alleviate the vanishing- and exploding-gradient problems encountered in conventional recurrent neural networks during long training sequences [16]. Machine-learning models such as Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) can also provide feature-importance diagnostics and represent complex nonlinear relationships. However, machine learning has intrinsic limitations: its application typically requires large amounts of in situ training data; moreover, such models struggle to represent real physical processes in an interpretable manner and often perform poorly for out-of-sample conditions [17,18]. Coupling machine-learning methods with physically guided hydrological–hydrodynamic models can partially mitigate the weaknesses of both classes of approaches. Hydrological and hydrodynamic models can supply valuable information and inputs to machine-learning algorithms. Physically guided models do not rely on dense, high-quality observations and can generate extreme scenarios that have not occurred in the historical record, thereby enriching the training space. In this way, the coupled framework can incorporate regional characteristics of the study area and enhance the generalization ability of machine-learning methods [19,20].

Motivated by this complementarity between physical and machine-learning approaches, the present study uses S_TIDE as a physically based tool for tidal harmonic analysis to construct physically modeled tides at 528 global tide-gauge stations from the UHSLC dataset. Three classical ensemble-learning methods are then trained on observed tides over a given period and used to correct the physical tide. On this basis, we summarize and evaluate the improvements and remaining limitations of a Physics-Constrained Ensemble-Learning Method (PELM) for extracting characteristic tidal signals and enhancing harmonic analysis.

2. Methodology

For purely data-driven machine-learning algorithms, incorporating prior physical constraints can effectively ensure the correctness of data fitting [21]. In this study, we construct a physically based tidal model on the basis of equilibrium tide theory using the EHA scheme and the S_TIDE framework [12], thereby providing a physics-based tidal-motion backbone for subsequent ensemble learning. The ensemble-learning methods are then trained to learn the residual variations between observed and physically modeled tides, yielding simulations that more closely approximate the actual tide and thereby satisfy the requirements of tidal computation.

2.1. CHA Principle

In the CHA model, the tidal elevation can be expressed as a linear superposition of multiple tidal constituents [22]:

where denotes the water level at time t; , and are the frequency, amplitude, and phase of the j-th tidal constituent, respectively; and is the mean water level (MWL). The above expression can be rewritten in linearized form as

where

2.2. S_TIDE Principle

In the EHA scheme adopted in S_TIDE [12], , , and are allowed to vary with time, so Equation (2) can be rewritten in a time-dependent form as

Unlike NS_TIDE, which solves the above equations using the classical scheme, S_TIDE adopts an independent-points (IP) strategy [23,24,25,26]. The basic idea of the IP approach is as follows. The harmonic parameters are assumed to vary with time, and is defined as the time index set. A subset is first selected as the index set of IPs, representing the parameter space, and the harmonic parameters at the IPs are computed using a specific algorithm. The harmonic parameters at all other times are then obtained by interpolating between the IPs [11]. These points are termed independent points because the parameter values at all other times are derived from the interpolated results at the IPs and therefore depend on the parameters at the IP locations [27].

The core idea of the EHA scheme is as follows. A set of independent points is uniformly distributed in the time domain, and the MWL and constituent coefficients at these IPs are treated as independent parameters. The MWL and constituent coefficients at all other times are then obtained by interpolation based on the IP scheme. Therefore, the time-varying MWL and constituent coefficients can be expressed as

Here, is the interpolation weight of the i-th IP at time t, which depends on the specific interpolation scheme; Ms and M denote the numbers of IPs associated with MWL and with the tidal constituents, respectively. The values of , , and are not known a priori, but, through interpolation, the time-varying MWL and constituent coefficients in the above expression can be represented as linear combinations of , , and . Substituting Equation (6) into Equation (5) then gives:

Because cubic-spline interpolation is stable, convergent, and smooth [27,28,29], S_TIDE adopts this interpolation method for data processing. Assume that observations are available at N time instants, i.e., at with corresponding measurements . The resulting system of equations to be solved in the S_TIDE scheme can then be written as

In this system, there are unknowns in total. When the number of observations N is much larger than , these unknowns can be estimated. By applying ordinary least squares (OLS) to fit and solve the system, one obtains , , and . Interpolation of these solutions then yields the time-varying MWL, amplitudes, and phases of each tidal constituent.

According to Pan et al. [12], the error-estimation algorithm can be summarized as follows [11]. First, the tidal and subtidal components estimated by EHA are removed from the original observed series to obtain the residuals. Second, 300 realizations of synthetic noise are generated by resampling the residual series. Third, the tidal and subtidal components are added back to each noise realization, and the tidal and subtidal constituents are re-estimated by least-squares fitting. Finally, confidence intervals are computed using the Student’s t-distribution. In this study, S_TIDE is implemented in MATLAB using the scripts S_TIDE_m8.m and s_construct2.m to perform tidal harmonic analysis, construct the physical tide, and generate reconstructed tidal series; key time points are further post-processed and verified using the S_TIDE graphical user interface (GUI).

2.3. Physics-Based Principles of the PELM Model

This study employs three classical ensemble-learning algorithms: Random Forests (RF), Extremely Randomized Trees (ET), and Gradient Boosting (GB) [30,31,32]. The main reason for adopting this framework is that ensemble learning can handle tidal data under conventional sample sizes, thereby avoiding the large data requirements associated with long short-term memory (LSTM) networks. Moreover, the primary objective of this study is to improve the extraction of tidal characteristics. Here, tidal characteristics are defined as regional tidal features formed jointly by astronomical tides and various persistent non-astronomical influences. To avoid overfitting in this process, the root-mean-square error (RMSE) of tidal-level predictions needs to be controlled at around 0.1 m. Therefore, three classical ensemble-learning methods are selected for processing and analysis in this study.

To incorporate nonlinear effects on top of the existing physical model, this study formulates the observed water level using Equation (9), i.e., the observed tide level is assumed to consist of the following three components:

In Equations (9) and (10), denotes the observed water level, denotes the physical tide, and is a nonlinear correction function, which in this study is approximated using three classical ensemble-learning algorithms. is random noise. The vector is a state vector representing nonlinear factors that influence the tide. , , , and denote the periods of the semidiurnal (12.42 h), diurnal (24.84 h), spring–neap (14.77 d), and annual (365.24 d) components, respectively.

Therefore, by substituting the corresponding terms into each component of Equation (9), we obtain the final physical expressions for the methods used in this study. The physical-tide term corresponds to the S_TIDE-based physical tide reconstruction. The nonlinear state function represents regionally periodic, non-astronomical state variables and can be regarded here as the correction function learned by the various ensemble-learning methods. The remaining term corresponds to noise. It should be emphasized, however, that Equation (9) is intended primarily as a conceptual physical model: ensemble-learning and related approaches are data-driven learning methods, and this does not imply that arbitrary data can always be transformed into an exact governing equation.

The key point of this study is to address the incompleteness of physical factors represented in conventional physical theories. Traditional physically based approaches largely omit non-astronomical forcing components, even though these influences can be non-negligible in nearshore tidal processes. Motivated by this gap, we use the physical theory as a constrained backbone and impose additional constraints on the machine-learning component. Specifically, we introduce the dominant tidal constituent periods as physically meaningful bounds (an outer envelope) to further reinforce the physical framework, thereby guiding the machine-learning model to extract the nonlinear, non-astronomical components embedded in the observed–physical discrepancy—components that are persistent, stable over long timescales, and practically significant. This is also why the nonlinear correction function can be viewed as the output of the prediction function learned by the chosen ensemble-learning method: the predicted correction is applied to adjust the physical tide, thereby compensating for the non-astronomical forcing components.

3. Data Source

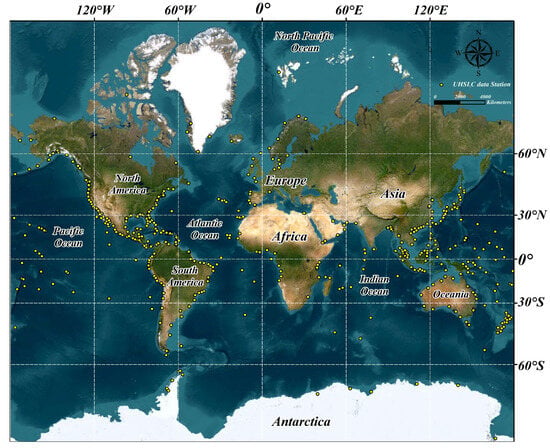

The University of Hawaii Sea Level Center (UHSLC) was established in the 1970s by Prof. Klaus Wyrtki to investigate El Niño and has since become an important component of the Global Sea Level Observing System (GLOSS) [33]. UHSLC provides research-quality hourly sea-level records and applies standardized processing, including removal of benchmark drift and correction of clock errors, to ensure the accuracy of the data for long-term climate studies. In this study, we use the research-quality datasets provided by UHSLC, which are further processed and then used as input to the ensemble-learning framework. After data screening and organization, records from 528 tide-gauge stations worldwide are retained; the locations of these stations are shown in Figure 1. The UHSLC data were obtained from: https://uhslc.soest.hawaii.edu/data (accessed on 30 September 2025).

Figure 1.

Selected UHSLC tide-gauge stations.

4. Result

4.1. Extraction of PELM Data and Model Input

In this study, a 4320 h (180 day) segment is randomly extracted for each of the 528 selected stations. The first 744 h of each segment are used as the computation window: S_TIDE is driven by these 744 h to construct the subsequent tide up to 4320 h, which is taken as the physical tide at that station. The same initial 744 h of observed tide are used to pre-train the ensemble-learning (EL) model, with a prescribed validation-split ratio defining the proportion reserved for validation, thereby yielding an EL model that has learned the regional tidal characteristics. Finally, the physical tide constructed by S_TIDE is fed into the trained EL model as input to obtain the final PELM tide.

The 31-day window adopted in this study represents the minimum data requirement commonly used in methods developed from the Classical Harmonic Analysis (CHA) framework; using records longer than this generally yields more accurate harmonic analysis results. In other words, it serves as a baseline duration for extracting regionally representative physical tidal characteristics. From first principles, tides are fundamentally periodic sea-level variations driven by astronomical motions, and a 31-day span is sufficient to capture the major periodic dynamical variations. Over this period, the Moon completes approximately one cycle relative to the Earth, allowing the principal tidal characteristics to be expressed. By contrast, the ensemble-learning component is intended to learn the persistent, medium-to-long-term non-astronomical influences at a site, compensating for the nonlinear factors missing between the physically reconstructed tide from classical theory and the observed tide. For these reasons, we adopted a 31-day window as the baseline time span in this study.

All EL models in this study are implemented in Python and run in the PyCharm integrated development environment (IDE). The tree-based ensemble models are built using the scikit-learn library. The partition between training and validation data is controlled by the hyperparameter “Validation split,” which specifies the fraction of training samples used for internal validation; based on experimental testing, an empirical suitable range for this value is 0.05–0.30. For the base learners in the ensembles, the main hyperparameters are set as follows: the number of trees is (M = 100) for RF and (M = 200) for ET; the random seed is fixed at 42; and the number of parallel threads for RF and ET is set to −1. All other key hyperparameters (e.g., max_features, min_samples_leaf, min_samples_split) follow the default settings of the respective library. In this study, we consider that for RF and ET, setting the hyperparameter M to 100 and 200, respectively, is sufficient for the needs of this scenario. Moreover, according to the original literature on these algorithms, (M) can be increased accordingly as the data volume grows. However, this does not imply that, under the data conditions of this study, increasing M would lead to a transformative or game-changing improvement in performance.

In this study, the hyperparameter “Validation split” controls how the training data are partitioned into a training subset and a validation subset. For example, a validation split of 0.15 means that, for the 744 h training record, 85% of the data are used for model training and the remaining 15% are used for validation after training. Based on repeated experiments, we found that for most stations the optimal performance is achieved when this value is set between 0.10 and 0.20.

4.2. Overall Enhancement Status of UHSLC Data

For the 528 selected stations, random data segments were extracted, and the physical tides computed by S_TIDE were compared with the PELM-corrected tides; the overall results are summarized in Table 1. The results show that at 60% of the tide-gauge stations, the improvement in tidal-fit performance after applying PELM exceeds 40%. In total, 490 stations (92.8%) exhibit improvements greater than 20%. Overall, across all 528 stations, the mean improvement is 45.63%, and the median improvement is 48.47%.

Table 1.

Summary of performance improvements at UHSLC stations.

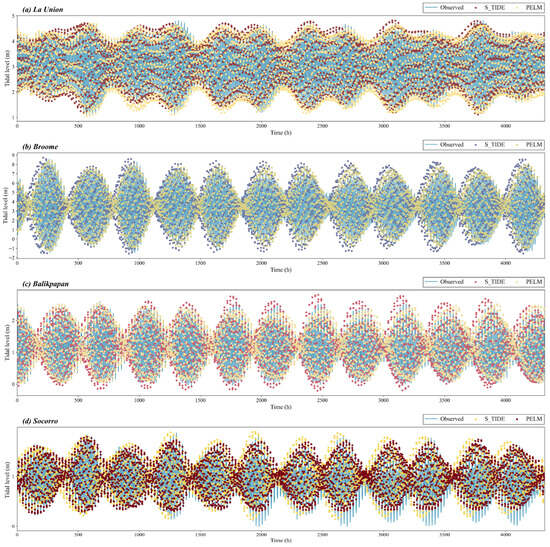

Considering that the root-mean-square error (RMSE) between the physical tide constructed by S_TIDE and the observed tide differs across stations, we compile station-wise statistics for both the physical tide and the PELM-corrected tide; the results are given in Table 2. Example comparisons of tidal elevations at selected stations with different levels of improvement are shown in Figure 2. For the physical tide produced by S_TIDE, the RMSE is mainly concentrated in the range 0.15–0.45 m, whereas after PELM correction the mean improvement is about 40%. The RMSE interval distribution of the PELM tide across all stations is summarized in Table 3. Based on the PELM results, 90% of the stations achieve an RMSE below 0.3 m, compared with 48.86% for the physical tide alone. In this study, we quantify performance using the RMSE difference (ΔRMSE) between the physical tide, the PELM tide, and the observed tide; the detailed statistics are given in Table 4. For most tide-gauge stations, ΔRMSE is positive: among all selected sites, 99.24% have ΔRMSE > 0, whereas only 0.76% have ΔRMSE < 0. Across all experimental stations, only four sites exhibit an increased error after PELM correction. The most pronounced deterioration occurs at Rockport, TX, where the RMSE of the physical tide is 0.1506 m, but the PELM tide yields an RMSE of 0.2311 m, corresponding to a degradation of about 53%; at the other three stations, the degradation is within 0–3%. As shown in Table 4, the overall improvement mainly lies in the range 0.05–0.30 m; 64.59% of the stations have ΔRMSE > 0.1 m, and 32.39% have ΔRMSE > 0.2 m.

Table 2.

RMSE distribution of physical tides at UHSLC stations.

Figure 2.

Tidal-elevation comparisons at selected example stations. From top to bottom, the panels correspond to La Union, Broome, Balikpapan, and Socorro. After PELM correction, the RMSE improvements are 74%, 60%, 50%, and 40%, respectively.

Table 3.

RMSE distribution of PELM-corrected tides at UHSLC stations.

Table 4.

Statistics of ΔRMSE for the two tidal estimates at UHSLC stations.

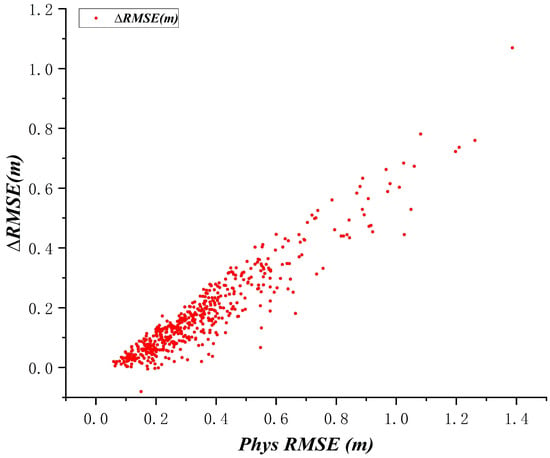

In this study, the Pearson correlation coefficient between the physical-tide RMSE and ΔRMSE is computed for all tide-gauge stations [34]. The relationship between physical RMSE and ΔRMSE for all stations is shown in Figure 3. The Pearson correlation coefficient is defined in this study as

Figure 3.

Relationship between physical-tide RMSE and ΔRMSE.

In the above equation, n is the number of stations; and denote the physical-tide RMSE at station i and the overall mean RMSE, respectively; and denote the ΔRMSE at station i and the overall mean ΔRMSE, respectively. The result r ≈ 0.94 indicates a highly linear relationship between the two variables.

4.3. Diebold–Mariano Test of Tidal Levels at Each Station

In this study, we employ the classical Diebold–Mariano test to quantitatively compare the predictive accuracy of the two models considered [35]. The time-by-time forecast errors of the S_TIDE tide and the PELM tide relative to the observed tide are computed, and the loss function L and loss-differential series dt are constructed as follows:

The loss function L is defined as the mean squared error (MSE) between the modeled tide and the observed tide. The sequence dt denotes the loss differentials, is the sample autocovariance, and is the Bartlett-weighted spectral estimator (with bandwidth q). The DM statistic is denoted by DM. If the resulting DM value is negative, this indicates that, under the chosen loss function, the PELM scheme outperforms the pure S_TIDE scheme. In this study, we regard DM < 0 with a p-value < 0.05 as evidence that PELM performs significantly better, whereas DM > 0 with a p-value < 0.05 is taken to indicate that the pure S_TIDE scheme is significantly better. When the p-value exceeds 0.05, the two schemes are considered statistically indistinguishable. The DM test was conducted at the 95% confidence level.

Based on the DM test results for all tide-gauge stations, summarized in Table 5, the proposed PELM exhibits a clear advantage at the majority of sites. Among the stations where PELM performs strongly, the mean improvement rate reaches 69%, with an average DM statistic of approximately −17. For the stations in Table 5 where no statistically significant difference is detected, three sites show a degradation in observational agreement after PELM correction, while six sites exhibit only marginal improvements (improvement rate < 10%). Only the Rockport, Texas, station yields a DM test outcome indicating that the pure S_TIDE scheme outperforms PELM. This result clearly indicates that, for most stations, the proposed PELM framework has broad applicability and is not limited to a single region or a specific local setting. A detailed analysis of this station is provided in the Section 5.

Table 5.

Summary of Diebold–Mariano test results for tides at UHSLC stations.

4.4. Results from Selected UHSLC Stations

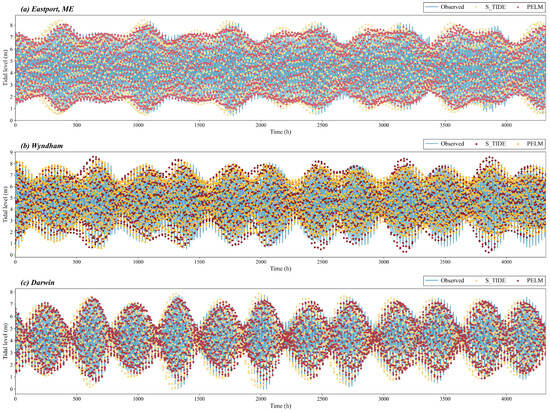

For the 56 stations where the physical-tide RMSE exceeds 0.6 m, the statistics are summarized in Table 6. All of these stations exhibit positive improvement, with a maximum improvement of 77% and a minimum of at least 27%. The table shows that stations with pronounced improvement (improvement ≥ 65%) share two characteristics: (1) the physical-tide errors are large, with a mean physical-tide RMSE of about 0.89 m; and (2) while substantially reducing the errors, the PELM tide also avoids overfitting, yielding a mean PELM RMSE of 0.25 m. Across the 56 stations, ΔRMSE ranges from 0.36 to 0.82 m, and most improvement ratios fall in the range 55–65%. Example comparisons of tidal elevations at a subset of these stations are shown in Figure 4, where stations with physical-tide RMSE > 0.6 m but different improvement levels are selected for illustration.

Table 6.

Statistics of physical tide RMSE > 0.6 m in the UHSLC dataset.

Figure 4.

Tidal-elevation comparisons at stations with model failure. From top to bottom, the panels correspond to Eastport, ME, Wyndham, and Darwin. The RMSEs of the physical tide at these stations are 1.3866 m, 1.2096 m, and 1.0492 m, respectively; after PELM correction, the RMSEs are reduced by 77%, 60%, and 50%, respectively.

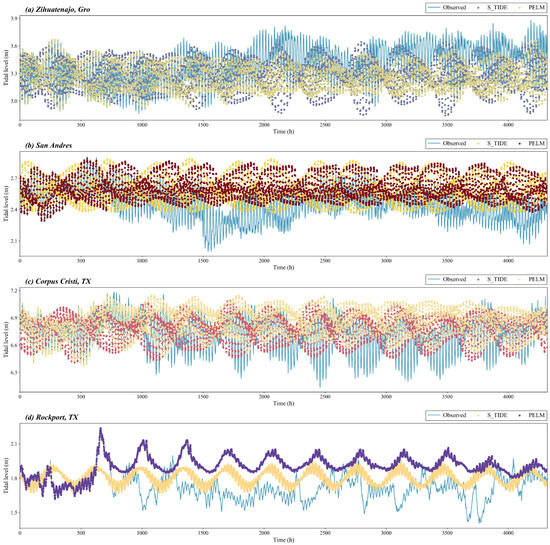

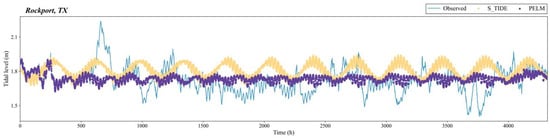

For the four stations where improvement fails, the statistics are summarized in Table 7 and Figure 5. These stations share the following characteristics: the observed tidal range is small, generally not exceeding 1 m; moreover, the physical tide already lies within an error range that is acceptable for avoiding overfitting. Under the present scheme, PELM slightly degrades tidal accuracy at these four stations; however, the model as a whole still effectively prevents overfitting and does not introduce any substantial distortion of the absolute tidal signal.

Table 7.

UHSLC stations where PELM fails to improve performance.

Figure 5.

Tidal-elevation comparisons at stations with model failure. From top to bottom, the panels correspond to Zihuatanejo, Gro; San Andres; Corpus Christi, TX; and Rockport, TX. After PELM correction, the performance deteriorates by 0.6%, 1.5%, 2.9%, and 53.5%, respectively.

5. Discussion

5.1. Analysis of PELM’s Advantages and Mechanism

The physics-constrained ensemble-learning method (PELM) proposed in this study is essentially a hybrid modeling paradigm that combines physically driven and data-driven approaches, with the aim of integrating the strong constraints of physical theory and the nonlinear approximation capability of machine learning. The total error in characteristic tidal levels can be decomposed into a systematic physical error and a stochastic residual noise component, and PELM is explicitly designed on the basis of this error-decomposition concept. The physical error prior provides the foundation and constraints: Classical Harmonic Analysis has an irreplaceable physical basis and interpretability for describing ocean sea-level characteristics [1].

Three classical ensemble-learning algorithms are employed in this study: RF, ET, and GB. Among these, RF and ET adopt parallel ensemble strategies based on bagging or randomization; by sampling training data and randomly selecting features, they reduce variance and enhance model generalization, thereby ensuring the robustness and reliability of the tidal estimates [36]. In contrast, GB uses a serial boosting strategy, whose core mechanism is to iteratively fit the negative gradient of the loss from the previous model so as to accurately and efficiently reduce the systematic bias of the model [30]. According to the statistical results, at stations with large physical RMSE, GB is often selected as the optimal model, achieving improvements exceeding 60% and substantially reducing the mean RMSE, which fully demonstrates its effectiveness in error correction [31]. It should be emphasized, however, that for the three ensemble methods used in this study, the differences in performance at a given station are in fact small; no single method is uniformly superior to the others, and the performance gap among the three schemes at the same site is on the order of 10%.

As the physical constraint backbone, CHA typically explains more than 95% of the variance in tidal time series and captures the basic linear dynamics of tidal-wave propagation and evolution, whereas S_TIDE, via EHA, further focuses on resolving nonstationary behavior under nontidal forcings such as river discharge [12]. Using the physical tide extracted by S_TIDE as a prior feature for the ensemble-learning models has two key advantages: (1) Reducing model complexity and simplifying the learning target of the data-driven component. The machine-learning model does not need to learn tidal periodicity, linear components, and primary amplitudes from scratch; it only needs to fit the residual series, thereby avoiding difficulties in representing the fundamental physical processes [37]. (2) Ensuring model robustness and credibility. Through the coupling between physical constraints and ensemble learning, the basic structure of the final tidal signal is determined by the physical model. Even under sparse training data or out-of-distribution tidal scenarios, PELM can preserve the essential tidal characteristics, thus avoiding physically unacceptable errors that may occur in purely data-driven models and improving generalization and robustness.

We argue that the approximately linear relationship observed between physical-tide RMSE and ΔRMSE (Figure 3), revealed by the Pearson correlation analysis, arises from both objective physical reasons and the modeling procedure. Physically, at typical tide-gauge stations, S_TIDE can capture the dominant tidal features; however, at stations with large tidal ranges, the physical-tide RMSE is unavoidably larger than at small-range sites, although the physical laws extracted by S_TIDE remain accurate and effective. As a result, the ensemble-learning algorithms can achieve much larger improvements at these stations, leading to relatively large ΔRMSE values and, hence, an approximately linear relationship between the two metrics.

It should also be emphasized that the residual series mainly contains the unexplained, non-astronomical components, including storm surges, upstream river discharge, sea-ice effects, and other nonlinear interactions between tidal and nontidal processes [38,39]. These nontidal disturbances are highly nonstationary, nonlinear, and stochastic, and are difficult to describe accurately using traditional analytical or linear methods, whereas ensemble-learning schemes have proven effective for this class of problems in an increasing number of applications [40,41]. As illustrated by the PELM experiments in this study (Figure 4), the behavior of PELM in residual correction precisely reflects the advantages and working mechanism of ensemble learning: it provides accurate nonlinear mapping and bias correction, effectively suppresses high variance and overfitting risks to ensure generalization, and enables targeted correction at stations with large baseline errors.

In this study, we performed (i) a hyperparameter-distribution analysis for “Validation split” under a fixed value setting and (ii) an analysis of the same parameter under different training-data lengths. The results indicate that, for the vast majority of stations, when using a 744 h record, the optimal value should be kept within 0.15. This suggests that, for tidal prediction, ensemble-learning models require a sufficiently large amount of training data to reliably capture region-specific nonlinear features; under the current data volume, more data are generally needed for training. When examining the same parameter under different data volumes, an apparent performance improvement is observed, primarily attributable to the increased training data length.

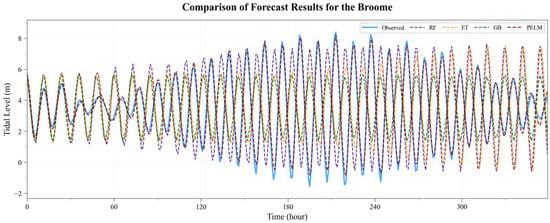

As shown in Figure 6, using the Broome station as an example, we found that when an ML-only approach is trained on the 744 h observed record and then used to forecast future tides, it cannot capture the overall tidal dynamics from data alone; once it moves beyond the training window, the predictions progressively drift and become distorted, leading to unrealistic water-level fluctuations. In contrast, PELM exhibits stronger physical consistency than both S_TIDE and the ML-only scheme, better captures the nonlinear influencing factors, and achieves an R2 of 97.94%.

Figure 6.

Comparison of tidal prediction results at the Broome station using the ML-only approach and the PELM.

5.2. Analysis of Model Failure and Limitations

The PELM proposed in this study does improve tidal accuracy over the selected set of stations, and shows particularly strong residual-correction capability at sites where the initial physical-tide RMSE is large. However, it is also necessary to acknowledge that PELM still has certain limitations and a non-negligible risk of model failure. First, from the perspective of model failure, our experiments show that at a small number of stations, the accuracy improvement is not significant and can even deteriorate slightly. These stations share the common feature of having relatively high initial physical-tide accuracy, which implies that when the physical model has already captured most of the tidal and nonstationary components, the remaining residual series is dominated by irreducible random noise and measurement errors [38]. In such cases, when an ensemble-learning or other nonlinear data-driven model attempts to fit these very small, random residual signals, it is easy for the model complexity to exceed that which is actually required by the data, thereby inducing overfitting and slightly degrading generalization performance on unseen data [42]. This mechanism is reflected in the negative ΔRMSE values at stations such as Rockport, TX. Although the overall robustness of the model is effectively controlled, this mechanism-related risk remains.

Moreover, as shown in Figure 5, the stations where improvement fails exhibit relatively unusual tidal characteristics: the tidal range is small, and the tide does not display a clear, regular pattern. We argue that in such situations, once S_TIDE becomes insufficiently accurate when constructing the physical tide, the physical model can be regarded as approximately failing. Failure here means that the physical reconstruction itself breaks down, so that the physical constraint ceases to hold and the ensemble-learning component effectively loses its constraint. When the physical model can no longer reliably capture the local tidal dynamics, subsequent ensemble learning merely acts on a misrepresented physical background and tends to amplify noise, ultimately leading to distorted tidal estimates. This is the fundamental reason why PELM fails at stations such as Rockport, TX, in our experiments.

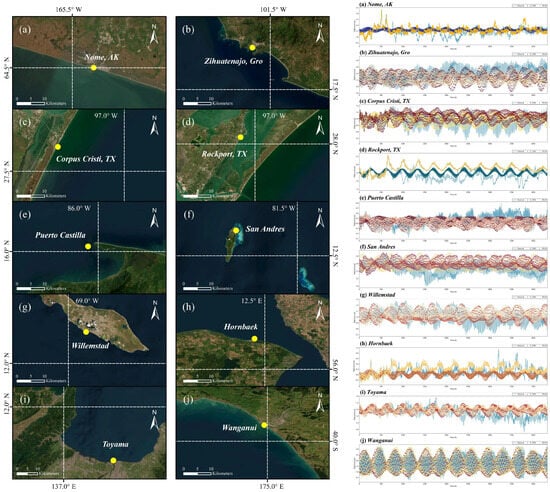

Second, PELM, as a hybrid modeling paradigm, faces the classical trade-off between accuracy and physical interpretability [37]. Although S_TIDE, as the physical core of this study, guarantees the physical basis of the tidal components, the ensemble-learning model is essentially a black-box model [39]. The residual correction learned by PELM cannot be straightforwardly and quantitatively related to specific nontidal physical processes (e.g., storm surges, river discharge, air-pressure effects). Compared with purely dynamical models, which can explicitly reveal the physical mechanisms of tide–nontide interactions through parameters or functional forms, this constitutes a limitation of PELM in terms of geophysical interpretability [4]. As can be seen from the tidal record at Rockport, TX, in Figure 5, isolated extreme values should not be included as training samples during PELM processing. After removing such noise, the results shown in Figure 7 are obtained. From an error-statistics perspective, the station exhibits a performance improvement of 28%, rather than the previously reported 53% degradation. However, this improvement is primarily statistical; because the overall tidal variability at this site is small, the final model output still does not clearly manifest the tidal characteristics. Figure 8 further shows that, at stations where the DM test cannot identify a significant advantage of PELM, the sites generally have rather special dynamical characteristics: the tidal range is not pronounced, and some stations are affected by extreme tidal fluctuations associated with non-regional, non-persistent disturbances, which cause the physical model to be nearly invalid. As a consequence, PELM has no clear advantage at these stations and may even underperform S_TIDE. We therefore conclude that the primary reason for model failure at Rockport, TX, is the presence of certain extreme influencing factors in the gauge record, which lead to failure of the S_TIDE-based tidal reconstruction at this site. Once the physical premise collapses, the subsequent ensemble-learning correction degenerates into a purely numerical adjustment lacking interpretability and physical meaning. Given the particularity of the tidal characteristics at the failure stations, PELM under a failed physical prior only induces some numerical changes and does not truly enhance the capability to extract regional tidal characteristics, and may even introduce distortions.

Figure 7.

Tidal-elevation comparison at Rockport, TX, after noise removal.

Figure 8.

Geographic locations and tidal records of stations for which the DM test does not indicate a significant advantage of PELM. In the DM test, panels (a–i) show no significant difference between the two schemes, whereas panel (j) indicates that S_TIDE performs better.

In addition, data requirements are an inherent constraint of all data-driven hybrid models. Although ensemble learning is less data-demanding than certain deep-learning models, accurately fitting residual patterns still requires long, continuous, and high-quality time-series observations for training [43]. This limits the applicability of PELM in coastal or estuarine regions where records are sparse, lack long-term accumulation, or contain substantial data gaps [44]. Machine-learning approaches have been widely adopted in current research [45,46,47]. We argue that although PELM addresses non-stationarity to some extent, the training set for the residual model is still derived from historical data. When confronted with extreme or unprecedented nontidal forcing events, the model may lack sufficient generalization capability to accurately capture residual extremes outside the training-data distribution. This calls for future work to incorporate deeper physical information as model inputs or to design dedicated loss functions that enhance robustness to extreme events. At the same time, when applying the PELM scheme to tidal data, incidental extreme values arising from occasional extreme factors should be removed; otherwise, the ensemble-learning model will treat these extremes as training samples, leading to progressive distortion of the trained model and degradation of subsequent results.

It should be noted that the proposed PELM framework can still be applied to sparse or discontinuous tide-gauge records, provided that missing water-level observations are removed while the original time stamps (i.e., the sampling interval) are preserved. However, it is not feasible for very short records because the physical foundation of S_TIDE remains Classical Harmonic Analysis (CHA) and is therefore constrained by the Rayleigh criterion; consequently, PELM is not applicable to substantially shorter time series.

Regarding S_TIDE, although this toolbox was developed under the EHA formulation, the physical foundation of EHA still originates from Classical Harmonic Analysis (CHA). Therefore, S_TIDE can be adapted to different scenarios and applied to both stationary and nonstationary tide-gauge records, which is why we consider it suitable as a global backbone model. Accordingly, for non-estuarine regions and low-tidal-range sites, we also regard it as applicable from the perspective of classical CHA principles. In essence, S_TIDE can be viewed as an extension and generalization of CHA. Its limitation, however, is that, being rooted in harmonic/physical principles, it does not sufficiently represent region-specific processes, and many regions are influenced by nonlinear effects. Therefore, in this study we consider the main limitation of the physical model to be that it can capture the dominant tidal dynamical characteristics but cannot inherently incorporate the nonlinear factors.

6. Summary

Building on the S_TIDE physical model, this study successfully develops and validates the PELM, aiming to integrate the prior knowledge embedded in the physical model with the nonlinear fitting capability of ensemble learning to achieve a comprehensive improvement in global tidal-feature retrieval accuracy. The physical tide reconstructed by S_TIDE is used as a physics-constrained backbone, and, together with the EHA scheme, it effectively captures tidal nonstationarity, providing a solid physical foundation for the subsequent machine-learning module, whose task is then limited to accurately correcting the residual series. Validation across 528 UHSLC tide-gauge stations demonstrates that PELM is broadly applicable and highly effective in improving tidal fitting accuracy. In particular, for high-error stations with initial physical RMSE exceeding 0.6 m, PELM reduces the mean RMSE from 0.83 m to 0.25 m, achieving an improvement of more than 65%, which clearly confirms the ability of ensemble-learning algorithms to mitigate systematic biases in the physical model. Although a small number of stations show limited improvement, their errors remain within normal accuracy bounds, avoiding gross distortion of the tidal signal. The strong linear relationship between the RMSE of the physical tide and ΔRMSE, as quantified by the Pearson correlation coefficient, further demonstrates that PELM can accurately and selectively correct the initial errors. At sites where the physical model fails, however, applying ensemble-learning correction may even increase the error.

Despite the improvements in tidal-feature extraction achieved by PELM, the framework still has limitations and a risk of mechanism failure. When the physical model does not successfully reproduce the local tidal regime, applying PELM can degrade tidal accuracy and partially worsen the tidal estimate. Future work should therefore explore richer physical information as model inputs and/or introduce dedicated loss functions to enhance robustness to extreme events. If sporadic, extreme events are included in the training data, the associated extreme tidal excursions will be treated by the ensemble-learning model as characteristic samples, and the learned model will gradually become distorted, which in turn affects subsequent predictions. Nevertheless, the overall results indicate that PELM is effective for constructing tidal characteristics. In regions with complex nonequilibrium tidal forcing, where conventional tidal solutions may show signs of distortion, the proposed framework can be used to correct the physical tide within a physically consistent backbone, thereby yielding characteristic tidal levels that are both more accurate and more stable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.X.; Data Curation, Y.L. and W.D.; Formal Analysis, Y.L.; Funding Acquisition, M.X.; Investigation, W.D. and M.X.; Methodology, Y.L. and M.X.; Software, Y.L.; Supervision, M.X.; Validation, M.X.; Visualization, Y.L.; Writing—Original Draft, Y.L.; Writing—Review and Editing, Y.L. and M.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Marine Science and Technology Innovation Research of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. JSZRHYKJ202103; JSZRHYKJ202311).

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available upon request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are extended to Haidong Pan from the First Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, for providing the S_TIDE toolkit and for his assistance with the related technical details.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PELM | Physics-constrained ensemble-learning method |

| UHSLC | University of Hawaii Sea Level Center |

| CHA | Classical Harmonic Analysis |

| CD | Complex Demodulation |

| CWT | Continuous Wavelet Transform |

| EHA | Enhanced Harmonic Analysis |

| IP | Independent Point |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MWL | Mean Water Level |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| GUI | Graphical User Interface |

| RF | Random Forests |

| ET | Extremely Randomized Trees |

| GB | Gradient Boosting |

| RMSE | Root-Mean-Square Error |

References

- Hoitink, A.J.F.; Jay, D.A. Tidal river dynamics: Implications for deltas. Rev. Geophys. 2016, 54, 240–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, D.A.; Flinchem, E.P. Interaction of fluctuating river flow with a barotropic tide: A demonstration of wavelet tidal analysis methods. J. Geophys. Res. 1997, 102, 5705–5720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, D.A.; Kukulka, T. Revising the paradigm of tidal analysis—The uses of non-stationary data. Ocean Dyn. 2003, 53, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matte, P.; Jay, D.A.; Zaron, E.D. Adaptation of classical tidal harmonic analysis to nonstationary tides, with application to river tides. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2013, 30, 569–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matte, P.; Secretan, Y.; Morin, J. Temporal and spatial variability of tidal-fluvial dynamics in the St. Lawrence fluvial estuary: An application of nonstationary tidal harmonic analysis. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2014, 119, 5724–5744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukulka, T.; Jay, D.A. Impacts of Columbia River discharge on salmonid habitat: 1. A nonstationary fluvial tide model. J. Geophys. Res. 2003, 108, 3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukulka, T.; Jay, D.A. Impacts of Columbia River discharge on salmonid habitat: 2. Changes in shallow-water habitat. J. Geophys. Res. 2003, 108, 3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, D.A.; Leffler, K.; Degens, S. Long-term evolution of Columbia River tides. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean Eng. 2011, 137, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowicz, R.; Beardsley, B.; Lentz, S. Classical tidal harmonic analysis including error estimates in MATLAB using T_TIDE. Comput. Geosci. 2002, 28, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, P.J. Robust statistical procedures. In CBMS-NSF Regional Conference Series in Applied Mathematics; Society of Industrial and Applied Mathematics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1996; Volume 68, p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, G.; Pan, H.; Zhang, Q.; Lv, X.; Zhao, W.; Gao, Y. Determination of harmonic parameters with temporal variations: An enhanced harmonic analysis algorithm and application to internal tidal currents in the South China Sea. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2018, 35, 1375–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Lv, X.; Wang, Y.; Matte, P.; Chen, H.; Jin, G. Exploration of tidal-fluvial interaction in the Columbia River estuary using S_TIDE. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2018, 123, 6598–6619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Tan, Z.; He, Q. Physics-informed neural networks of the Saint-Venant equations for downscaling a large-scale river model. Water Resour. Res. 2023, 59, e2022WR033168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y. Stock closing price prediction based on sentiment analysis and LSTM. Neural Comput. Appl. 2020, 32, 9713–9729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Luo, H.; He, J.; Cheung, R.W.M. AI-powered landslide susceptibility assessment in Hong Kong. Eng. Geol. 2021, 288, 106103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichstein, M.; Camps-Valls, G.; Stevens, B.; Jung, M.; Denzler, J.; Carvalhais, N.; Prabhat. Deep learning and process understanding for data-driven Earth system science. Nature 2019, 566, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A.Y.; Jiang, P.; Mudunuru, M.K.; Chen, X. Explore Spatio-Temporal Learning of Large Sample Hydrology Using Graph Neural Networks. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2021WR030394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Moosavi, V.; Leitão, J.P. Data-driven rapid flood prediction mapping with catchment generalizability. J. Hydrol. 2022, 609, 127726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, Z.M.; Allawi, M.F.; Yousif, A.A.; Jaafar, O.; Hamzah, F.M.; El-Shafie, A. Non-tuned machine learning approach for hydrological time series forecasting. Neural Comput. Appl. 2018, 30, 1479–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Appling, A.P.; Gentine, P.; Bandai, T.; Gupta, H.; Tartakovsky, A.; Baity-Jesi, M.; Fenicia, F.; Kifer, D.; Li, L. Differentiable modelling to unify machine learning and physical models for geosciences. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 552–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreman, M.G.G.; Henry, R.F. The harmonic analysis of tidal model time series. Adv. Water Resour. 1989, 12, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Pan, H.; Fan, W.; Lv, X. Application of surface spline interpolation in inversion of bottom friction coefficients. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2017, 34, 2021–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhang, J. Numerical study on spatially varying bottom friction coefficient of a 2D tidal model with adjoint method. Cont. Shelf Res. 2006, 26, 1905–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Guo, Z.; Lv, X. Inversion of tidal open boundary conditions of the M2 constituent in the Bohai and Yellow Seas. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2017, 34, 1661–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, X.; Wang, P.; Wang, Y.P. Study on linear and nonlinear bottom friction parameterizations for regional tidal models using data assimilation. Cont. Shelf Res. 2011, 31, 555–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Pan, H.; Cao, A.; Lv, X. A harmonic analysis method adapted to capturing slow variations of tidal amplitudes and phases. Cont. Shelf Res. 2018, 164, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.E.; Shen, Z.; Long, S.R.; Wu, M.C.; Shih, H.H.; Yen, N.; Tung, C.C.; Liu, H.H. The empirical mode decomposition and the Hilbert spectrum for nonlinear and non-stationary time series analysis. R. Soc. Publ. 1998, 454, 903–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, R.; Zhou, F.; Ceder, G. Kinetics of non-equilibrium lithium incorporation in LiFePO4. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 587–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, P.; Ernst, D.; Wehenkel, L. Extremely randomized trees. Mach. Learn. 2006, 63, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrifield, M.; Aarup, T.; Allen, A.; Aman, A.; Caldwell, P.; Bradshaw, E.; Fernandes; Hayashibara, H.; Hernandez, F.; Kilonsky, B.; et al. The global sea level observing system (GLOSS). In Proceedings of the OceanObs, Venice, Italy, 21–25 September 2009; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, K., VII. Mathematical contributions to the theory of evolution.—III. Regression, heredity, and panmixia. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Charact. 1896, 187, 253–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, F.X.; Mariano, R.S. Comparing Predictive Accuracy. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 1995, 13, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.H. Ensemble Methods: Foundations and Algorithms; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, B.; Qin, B.; Yuan, S.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y. PIRT: A physics-informed red tide deep learning forecast model considering causal-inferred predictors selection. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 1501005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahryari Nia, K.; Sharifi, M.A.; Farzaneh, S. Tidal level prediction using combined methods of harmonic analysis and deep neural networks in southern coastline of Iran. Mar. Geod. 2022, 45, 645–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monahan, T.; Tang, T.; Roberts, S.; Adcock, T. RTide: Machine learning enhanced response method for the analysis and prediction of estuarine tides and storm surge. Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willard, J.D.; Varadharajan, C. Machine learning ensembles can enhance hydrologic predictions and uncertainty quantification. J. Geophys. Res. Mach. Learn. Comput. 2025, 2, e2025JH000732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, M.M.; Pardo, D.; Alkhalifah, T. Ensemble deep learning for enhanced seismic data reconstruction. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5916311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, D.; Osborne, M.; Adcock, T. A Machine Learning Approach to the Prediction of Tidal Currents. In Proceedings of the ISOPE International Ocean and Polar Engineering Conference, Rhodes, Greece, 26 June–1 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.J.; Kim, T.Y.; Lee, S.G.; Kim, J.S.; Yun, H.S. Physics-Guided AI Tide Forecasting with Nodal Modulation: A Multi-Station Study in South Korea. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durap, A. Predicting ocean parameters with explainable machine learning: Overcoming scale and time challenges. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2025, 90, 104424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durap, A. Interpretable machine learning for coastal wind prediction: Integrating SHAP analysis and seasonal trends. J. Coast. Conserv. 2025, 29, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durap, A. Explainable machine learning for bathymetric mapping: Adaptive normalization and feature engineering in complex seabed terrains. Ocean. Sci. J. 2025, 60, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.