Explainable Predictive Maintenance of Marine Engines Using a Hybrid BiLSTM-Attention-Kolmogorov Arnold Network

Abstract

1. Introduction

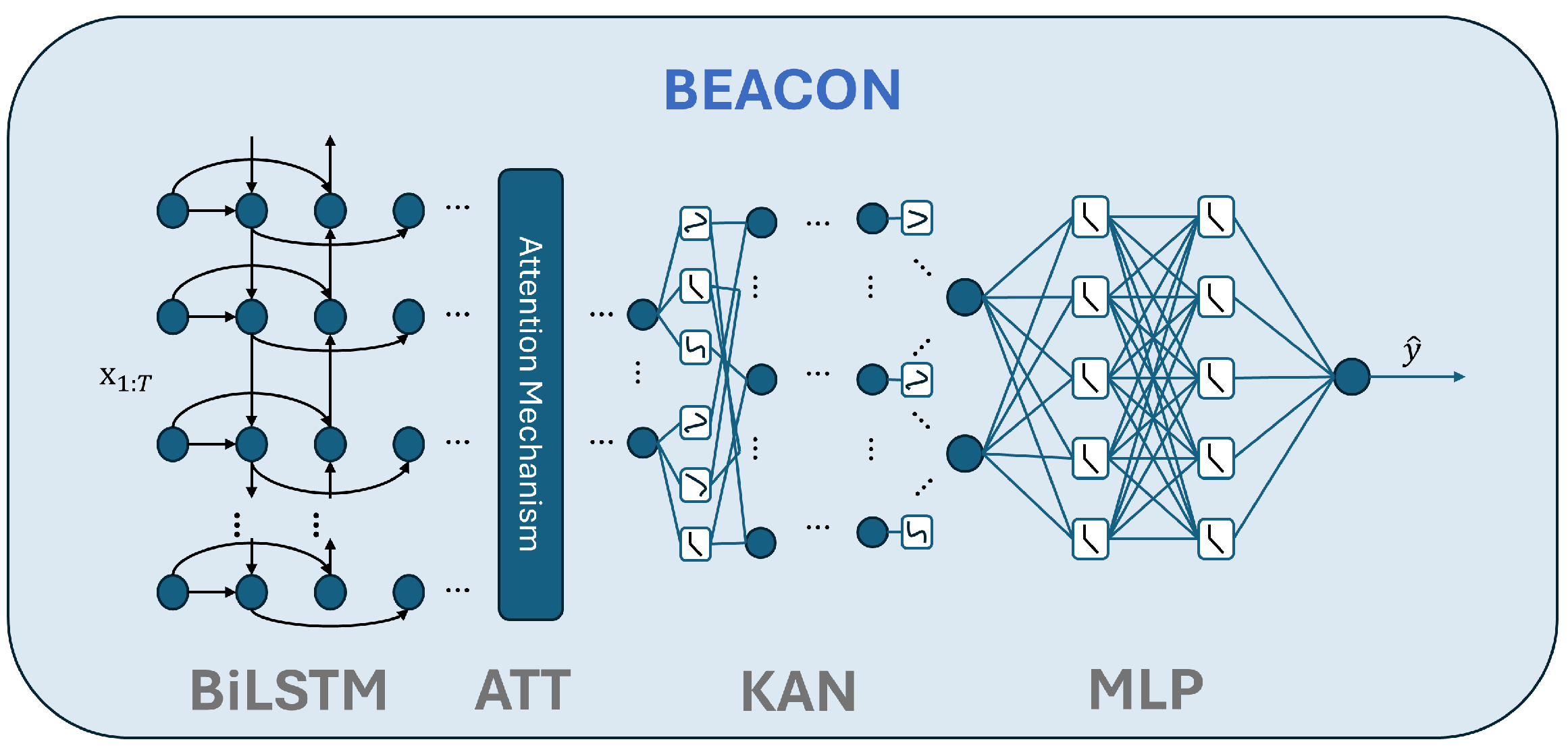

- We introduce BEACON, a hybrid BiLSTM-Att-KAN-MLP architecture tailored to cylinder-level EGT forecasting for marine engines;

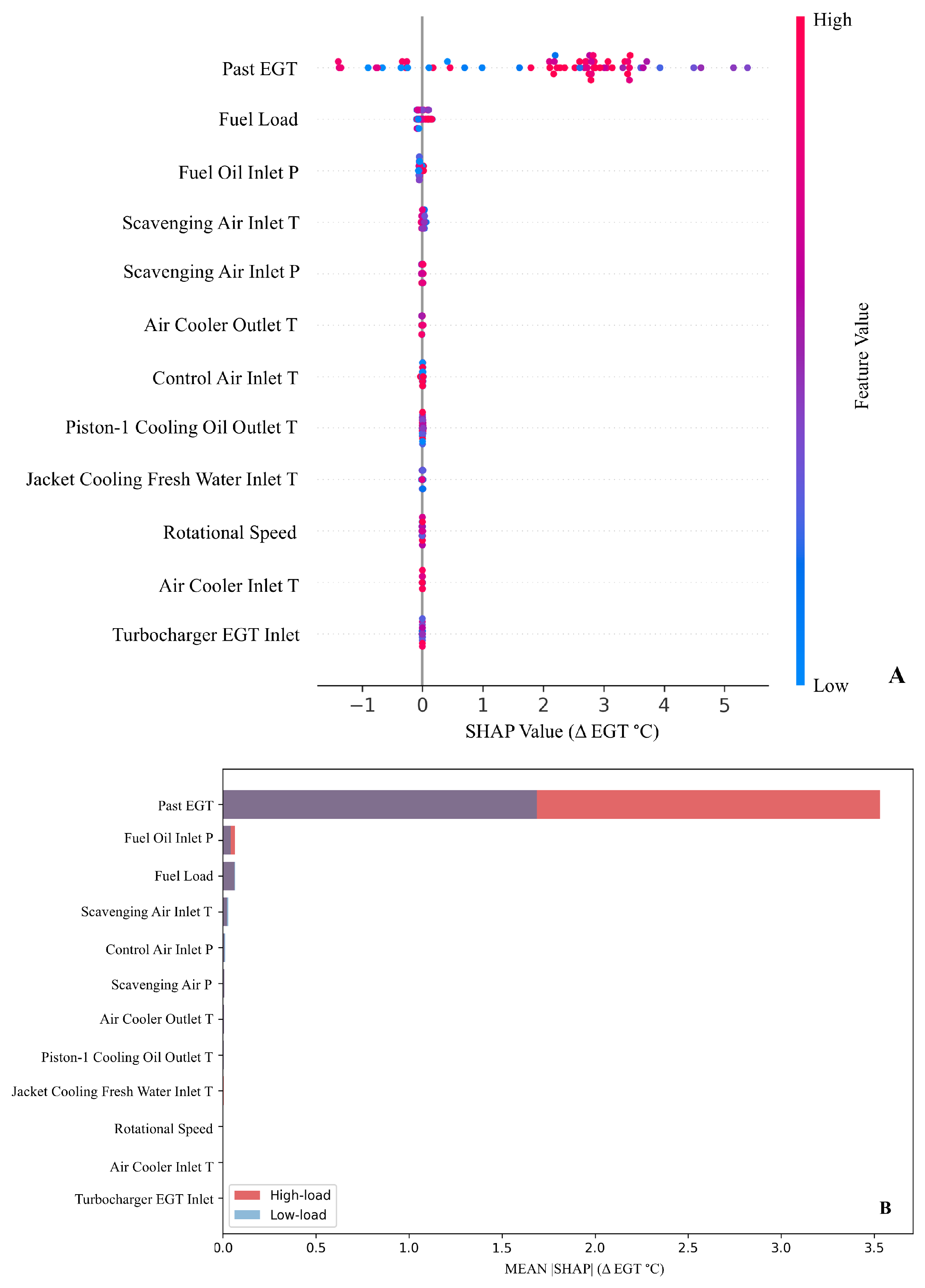

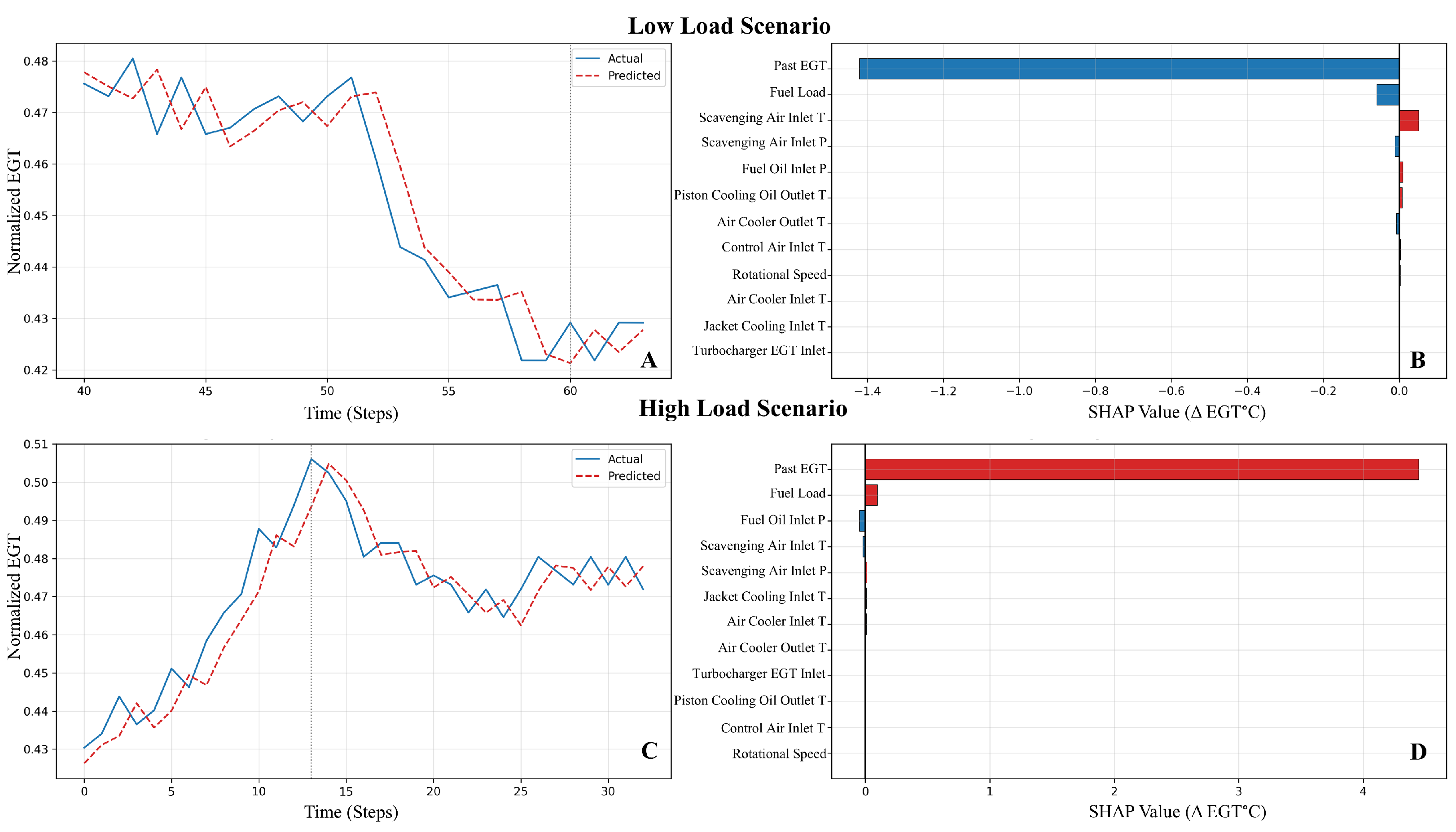

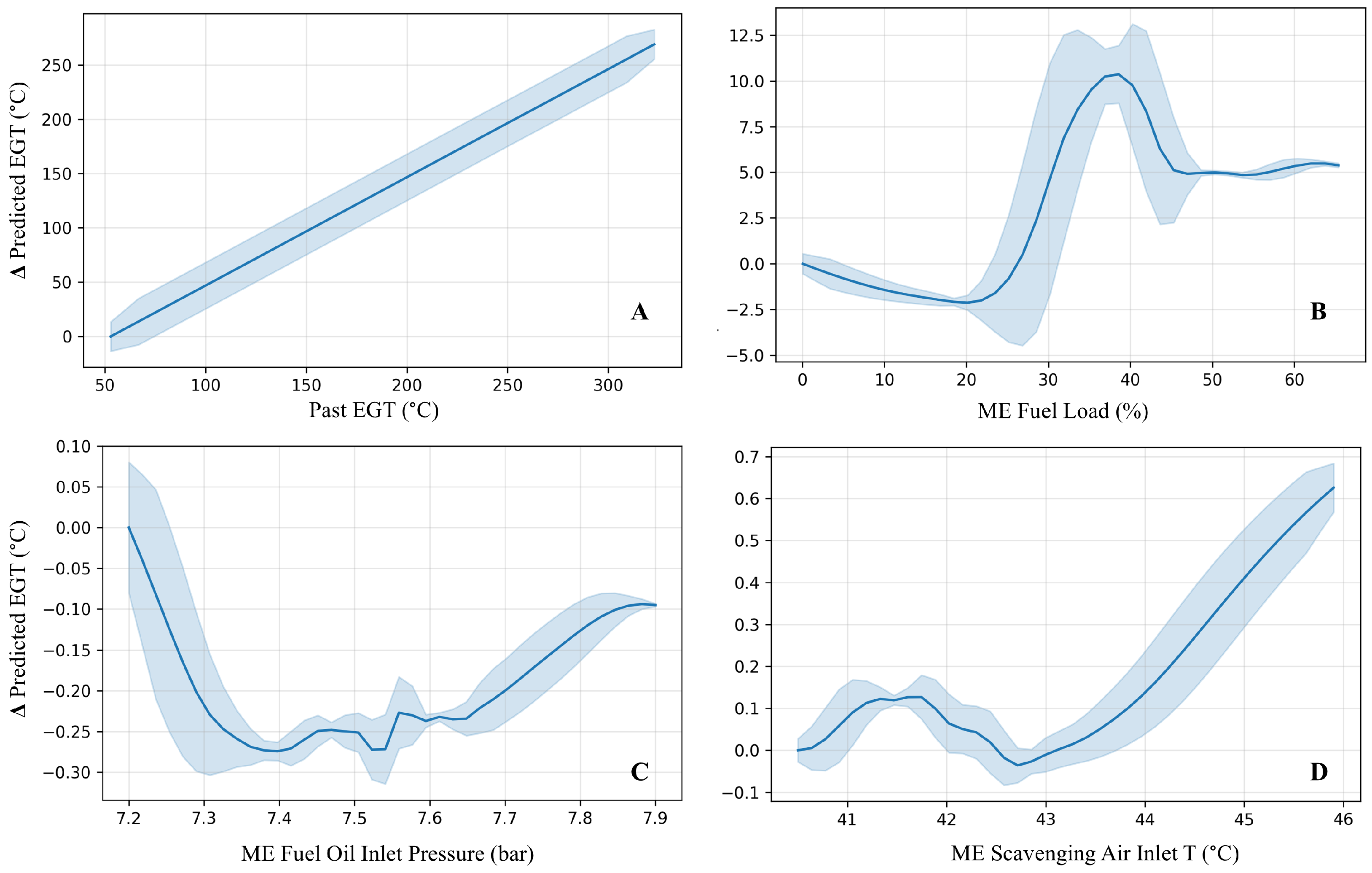

- Using operational main engine data from a bulk carrier, we demonstrate that BEACON produces interpretable partial dependence curves built from the spline functions between latent features and EGT, consistent with known thermodynamic and operational relations, providing a “glass-box” view that complements SHAP-based feature attributions;

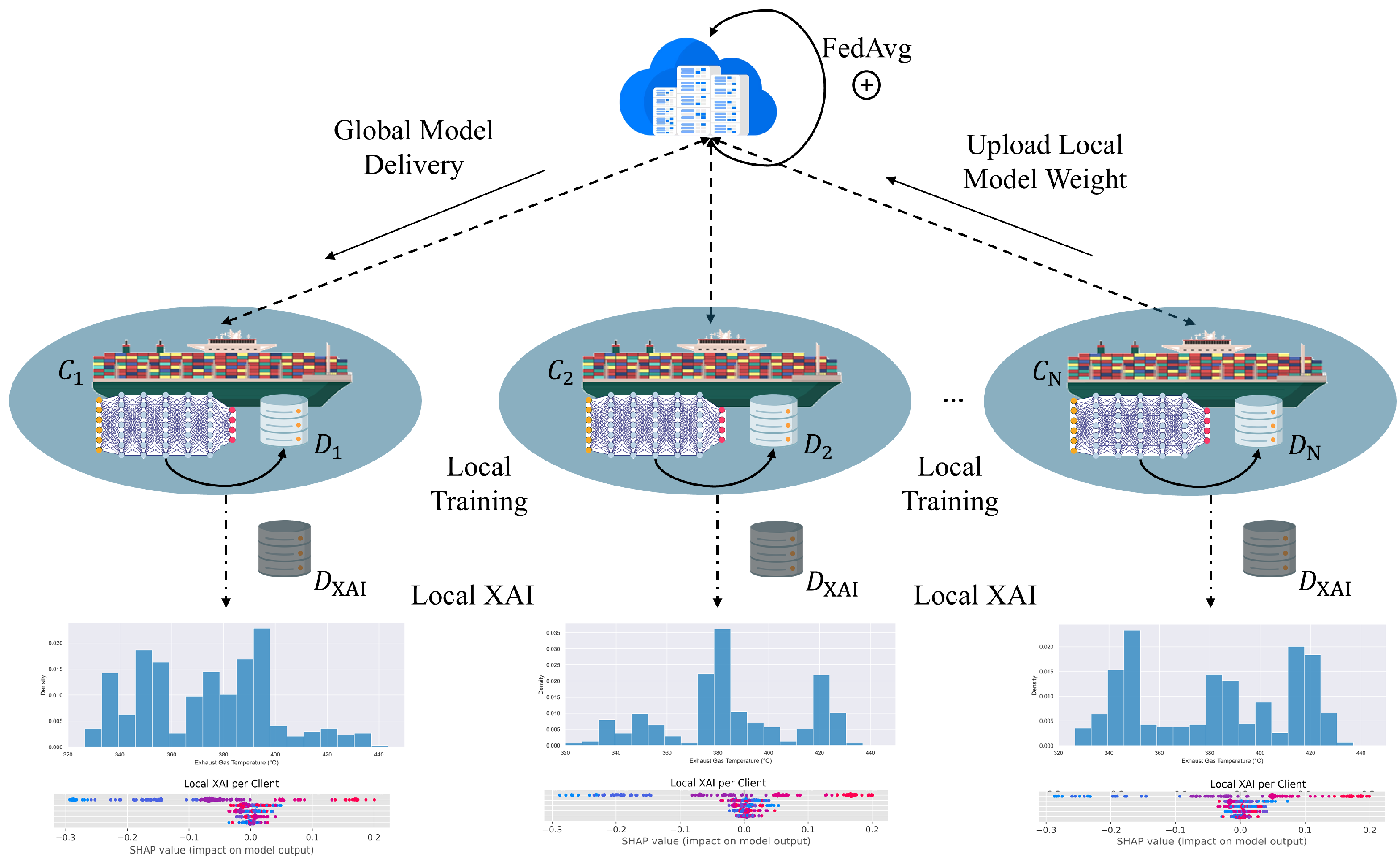

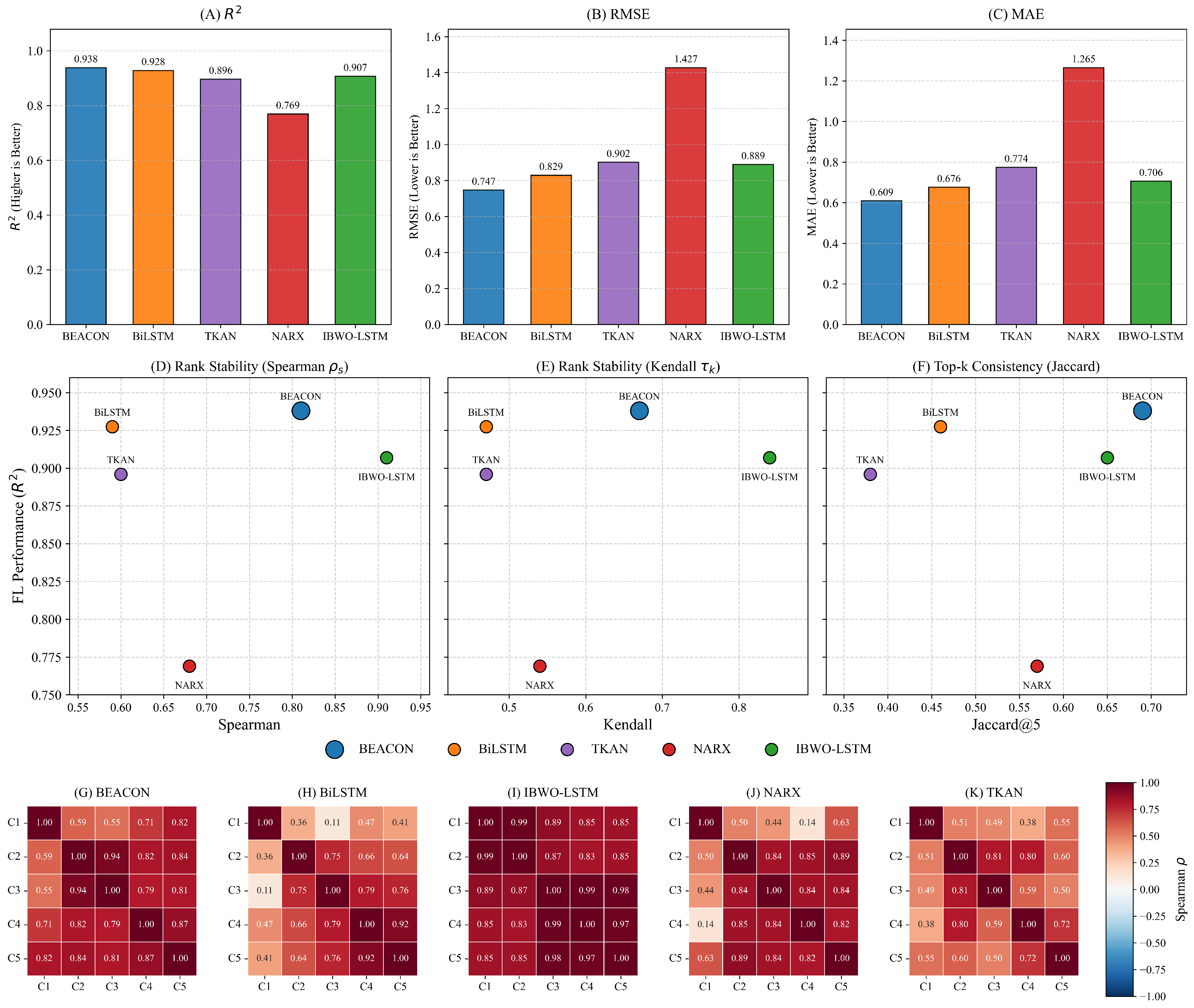

- We benchmark BEACON against state-of-the-art PdM models in both centralized and federated settings under realistic moderate non-IID partitioning;

- We study SHAP-based feature rankings across FL clients to show that explanation stability offers a complementary axis for comparing models in safety-critical applications such as in maritime maintenance (i.e., accuracy-interpretability trade-off).

2. Related Work

2.1. Maritime Predictive Maintenance and EGT Modelling

2.2. Kolmogorov Arnold Networks and Temporal Feature Extraction

2.3. Explainable AI, Federated Learning and Explanation Stability

2.4. Positioning of This Work

3. Model Architecture

3.1. Problem Setup and Notation

3.2. Temporal Bidirectional LSTM Encoder

3.3. Deterministic Attention Pooling

3.4. Kolmogorov Arnold Network

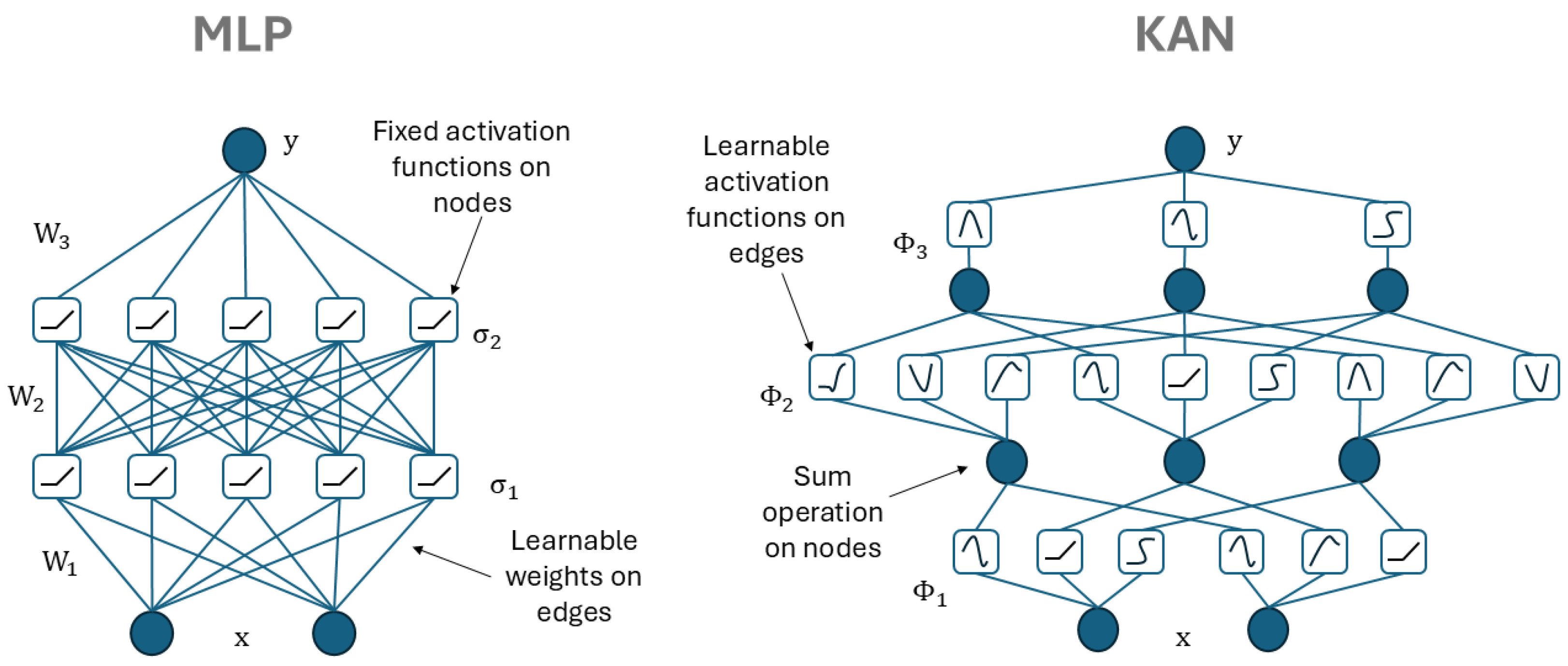

3.4.1. Comparison with a Multilayer Perceptron

3.4.2. B-Spline Basis for 1D Functions

3.4.3. Single KAN Layer

3.5. Training Objective

| Algorithm 1 BEACON forward pass for a single window |

|

| Algorithm 2 BEACON training with mini batch SGD and spline regularization |

|

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. Dataset

4.2. Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

4.3. Baseline PdM Models, Training Setup and Evaluation Metrics

4.3.1. Baseline Predictive Models

4.3.2. Federated Learning Setup

4.3.3. Evaluation Metrics

5. Results

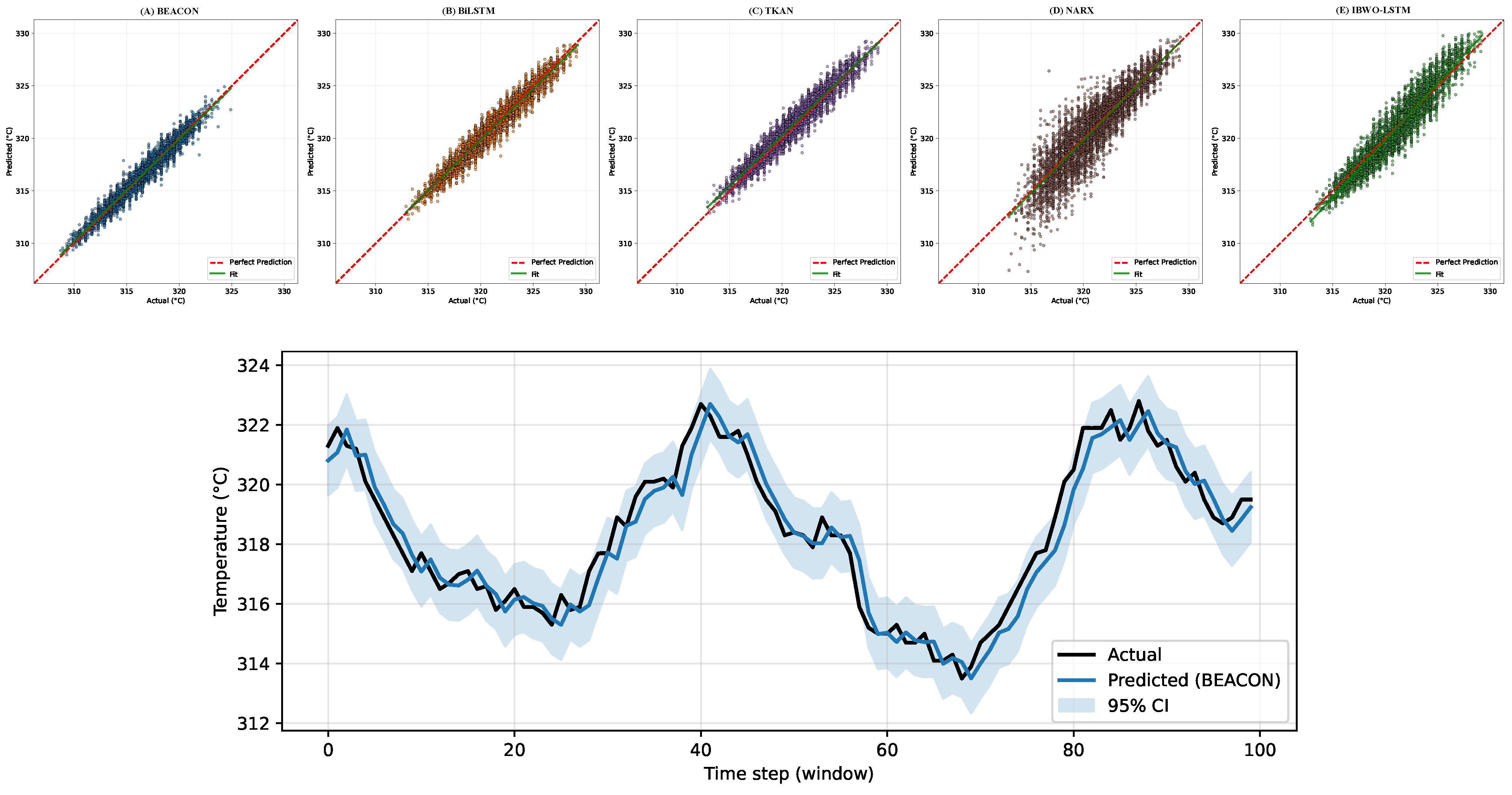

5.1. Centralized Performance Evaluation

5.2. Federated Learning Evaluation

5.3. Ablation Analysis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BiLSTM | Bidirectional long short-term memory network |

| EGT | Exhaust gas temperature |

| FedAvg | Federated averaging |

| FL | Federated learning |

| IBWO-LSTM | LSTM tuned with Improved Binary Whale Optimization |

| Jaccard index on the top five ranked features | |

| K | Number of B-spline basis functions per KAN map |

| KAN | Kolmogorov Arnold network |

| L | Number of BiLSTM layers |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

| ME | Main engine |

| N | Number of samples in an evaluation set |

| NARX | Nonlinear autoregressive model with exogenous inputs |

| PdM | Predictive maintenance |

| Coefficient of determination | |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| SHAP | Shapley Additive Explanations |

| T | Sequence length (time steps per input window) |

| TKAN | Temporal Kolmogorov Arnold network |

| XAI | Explainable artificial intelligence |

| Dirichlet concentration parameter for client partitioning | |

| d | Number of input features |

| h | Hidden size per LSTM direction |

| Mean and standard deviation of EGT in the training set | |

| Multivariate input window at decision time t | |

| Physical EGT target at time | |

| Spearman rank correlation between SHAP rankings | |

| Kendall rank correlation between SHAP rankings |

References

- Aslam, S.; Michaelides, M.P.; Herodotou, H. Internet of ships: A survey on architectures, emerging applications, and challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 9714–9727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalafatelis, A.S.; Nomikos, N.; Giannopoulos, A.; Trakadas, P. A Survey on Predictive Maintenance in the Maritime Industry Using Machine and Federated Learning. TechRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maione, F.; Lino, P.; Maione, G.; Giannino, G. A machine learning framework for condition-based maintenance of marine diesel engines: A case study. Algorithms 2024, 17, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). 2023 IMO Strategy on Reduction of GHG Emissions from Ships; IMO: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, E. FuelEU Maritime—Avoiding Unintended Consequences; European Community Shipowners’ Associations (ECSA): Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Flodén, J.; Zetterberg, L.; Christodoulou, A.; Parsmo, R.; Fridell, E.; Hansson, J.; Rootzén, J.; Woxenius, J. Shipping in the EU emissions trading system: Implications for mitigation, costs and modal split. Clim. Policy 2024, 24, 969–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrzljak, V.; Žarković, B.; Prpić-Oršić, J. Marine Slow Speed Two-Stroke Diesel Engine–Numerical Analysis of Efficiencies and Important Operating Parameters. Mach. Technol. Mater. 2017, 11, 481–484. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlenko, N.; Comer, B.; Zhou, Y.; Clark, N.; Rutherford, D. The Climate Implications of Using LNG as a Marine Fuel; Swedish Environmental Protection Agency: Stockholm, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, M.; Gan, H.; Cong, Y.; Wang, H. Numerical simulation of methane slip from marine dual-fuel engine based on hydrogen-blended natural gas strategy. Fuel 2024, 358, 130132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Gan, H.; Liu, H.; Lu, D. Deep learning-based research on fault warning for marine dual fuel engines. Brodogr. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean. Eng. Res. Dev. 2025, 76, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Ran, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wen, Y. A survey of predictive maintenance: Systems, purposes and approaches. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.07383. [Google Scholar]

- Kalafatelis, A.S.; Nomikos, N.; Giannopoulos, A.; Alexandridis, G.; Karditsa, A.; Trakadas, P. Towards predictive maintenance in the maritime industry: A component-based overview. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korczewski, Z. Exhaust gas temperature measurements in diagnostics of turbocharged marine internal combustion engines Part II dynamic measurements. Pol. Marit. Res. 2016, 23, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Srivastava, A.; Goel, N.; McMaster, J. Exhaust gas temperature data prediction by autoregressive models. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 28th Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (CCECE), Halifax, NS, Canada, 3–6 May 2015; pp. 976–981. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Z.; Gan, H.; Liu, B. A deep learning-based fault warning model for exhaust temperature prediction and fault warning of marine diesel engine. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, Z.; Yao, C.; Chen, J.; Lu, L.; Song, E. Multi-system condition monitoring of marine engines: A unified deep learning framework introducing physical prior knowledge. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2025, 17, 100698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leifsson, L.Þ.; Sævarsdóttir, H.; Sigurðsson, S.Þ.; Vésteinsson, A. Grey-box modeling of an ocean vessel for operational optimization. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2008, 16, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Noh, Y.; Kang, Y.J.; Sim, J.; Jang, M. An integrated grey-box model for accurate ship engine performance prediction under varying speed and environmental conditions. Int. J. Engine Res. 2024, 25, 1093–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, P.; He, X.; Jiang, Y. A prediction method for exhaust gas temperature of marine diesel engine based on LSTM. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Civil Aviation Safety and Information Technology (ICCASIT), Weihai, China, 14–16 October 2020; pp. 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Gan, H.; Ji, Z. Research on multi-parameter fault early warning for marine diesel engine based on PCA-CNN-BiLSTM. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhrhouj, A.; Ananou, B.; Ouladsine, M. Exploring Explainable Machine Learning for Enhanced Ship Performance Monitoring. In Machine Learning, Optimization, and Data Science; Springer: Cham, Swizterland, 2024; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Höhn, D.; Mumm, L.; Reitz, B.; Tsiroglou, C.; Hahn, A. Enabling Future Maritime Traffic Management: A Decentralized Architecture for Sharing Data in the Maritime Domain. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalafatelis, A.S.; Nikolakakis, V.; Tsoulakos, N.; Trakadas, P. Privacy-Preserving Hierarchical Federated Learning over Data Spaces. In Proceedings of the 13th IEEE International Conference on Big Data 2025 (BigData), Macau, China, 8–11 December 2025; pp. 6424–6433. [Google Scholar]

- Doulkeridis, C.; Santipantakis, G.M.; Koutroumanis, N.; Makridis, G.; Koukos, V.; Theodoropoulos, G.S.; Theodoridis, Y.; Kyriazis, D.; Kranas, P.; Burgos, D.; et al. Mobispaces: An architecture for energy-efficient data spaces for mobility data. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData), Sorrento, Italy, 15–18 December 2023; pp. 1487–1494. [Google Scholar]

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; y Arcas, B.A. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Proceedings of the 20th Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 20–22 April 2017; pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Karimireddy, S.P.; Kale, S.; Mohri, M.; Reddi, S.; Stich, S.; Suresh, A.T. Scaffold: Stochastic controlled averaging for federated learning. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning PMLR, Virtual Event, 13–18 July 2020; pp. 5132–5143. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Melis, D.; Jaakkola, T.S. On the robustness of interpretability methods. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1806.08049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossu, A.; Spinnato, F.; Guidotti, R.; Bacciu, D. Drifting explanations in continual learning. Neurocomputing 2024, 597, 127960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanova, A.; Imakura, A.; Sakurai, T. DC-SHAP method for consistent explainability in privacy-preserving distributed machine learning. Hum.-Centric Intell. Syst. 2023, 3, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Saif, S.; Islam, M.S. A novel federated learning approach for IoT botnet intrusion detection using SHAP-based knowledge distillation. Complex Intell. Syst. 2025, 11, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Vaidya, S.; Ruehle, F.; Halverson, J.; Soljačić, M.; Hou, T.Y.; Tegmark, M. Kan: Kolmogorov-arnold networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.19756. [Google Scholar]

- Raptodimos, Y.; Lazakis, I. Application of NARX neural network for predicting marine engine performance parameters. Ships Offshore Struct. 2020, 15, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zeng, H.; Ye, K. Short-term exhaust gas temperature trend prediction of a marine diesel engine based on an improved slime mold algorithm-optimized bidirectional long short-term memory—Temporal pattern attention ensemble model. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chang, X. Marine diesel engine piston ring fault diagnosis based on LSTM and improved beluga whale optimization. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 109, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejanović, M.; Panić, S.; Kontrec, N.; Đošić, D.; Milojević, S. Neural Network-Based Optimization of Repair Rate Estimation in Performance-Based Logistics Systems. Information 2025, 16, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaca-Rubio, C.J.; Blanco, L.; Pereira, R.; Caus, M. Kolmogorov-arnold networks (kans) for time series analysis. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.08790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Chen, L.; Wang, S. Kolmogorov-arnold networks for time series: Bridging predictive power and interpretability. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.02496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genet, R.; Inzirillo, H. TKAN: Temporal Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2405.07344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, Z.C. The mythos of model interpretability: In machine learning, the concept of interpretability is both important and slippery. Queue 2018, 16, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi-Velez, F.; Kim, B. Towards a rigorous science of interpretable machine learning. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1702.08608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, J.; Gilmer, J.; Muelly, M.; Goodfellow, I.; Hardt, M.; Kim, B. Sanity checks for saliency maps. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Montréal, QC, Canada, 3–8 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Antariksa, G.; Handayani, M.P.; Lee, S.; Lee, J. Explainable anomaly detection framework for maritime main engine sensor data. Sensors 2021, 21, 5200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Je-Gal, H.; Park, Y.S.; Park, S.H.; Kim, J.U.; Yang, J.H.; Kim, S.; Lee, H.S. Time-series explanatory fault prediction framework for marine main engine using explainable artificial intelligence. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, R.; Peters, T.M.; Scharlau, I.; Hammer, B. Trust, distrust, and appropriate reliance in (X) AI: A conceptual clarification of user trust and survey of its empirical evaluation. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2025, 91, 101357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papenmeier, A.; Englebienne, G.; Seifert, C. How model accuracy and explanation fidelity influence user trust. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.12652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, R.K.; Hoque, K.A. Explainable predictive maintenance is not enough: Quantifying trust in remaining useful life estimation. Annu. Conf. PHM Soc. 2023, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.W.; Xiang, Y.; Lu, S.; Liu, Y. An optimized updating adaptive federated learning for pumping units collaborative diagnosis with label heterogeneity and communication redundancy. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 152, 110724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Li, Y.; Song, Y.; Qiu, M. Personalized federated learning for fault diagnosis with mixture of experts. Inf. Fusion 2025, 125, 103439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G. Interpret federated learning with shapley values. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.04519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirie, C.; Wiratunga, N.; Wijekoon, A.; Moreno-Garcia, C.F. AGREE: A feature attribution aggregation framework to address explainer disagreements with alignment metrics. In Proceedings of the CEUR Workshop Proceedings, Aberdeen, UK, 17 July 2023; Volume 3438. [Google Scholar]

- Kalafatelis, A.S.; Pitsiakou, A.; Nomikos, N.; Tsoulakos, N.; Syriopoulos, T.; Trakadas, P. FLUID: Dynamic Model-Agnostic Federated Learning with Pruning and Knowledge Distillation for Maritime Predictive Maintenance. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Gan, H.; Chen, D.; Shu, Z. Research on fault early warning of marine diesel engine based on CNN-BiGRU. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 11, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. FedPDC: Federated Learning for Public Dataset Correction. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.12503. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, S.; Toborek, V.; Beckh, K.; Jakobs, M.; Bauckhage, C.; Welke, P. An empirical evaluation of the Rashomon effect in explainable machine learning. In Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases: Research Track; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 462–478. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Huang, K.; Yang, W.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z. On the convergence of fedavg on non-iid data. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.02189. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Liang, P.P.; Xia, Y.; Wang, F.; Adeli, E.; Li, F.-F.; Rubin, D. Rethinking architecture design for tackling data heterogeneity in federated learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 10061–10071. [Google Scholar]

| Feature (Symbol) | Unit | Main Role |

|---|---|---|

| Engine speed | rpm | Indicates ME operating point and load level |

| Fuel load | % | Proxy for thermal loading and combustion demand |

| Scavenge air pressure | bar | Reflects charge air density and gas clearing |

| Piston cooling oil outlet | Local piston and liner thermal state | |

| Air cooler air inlet | Charge air temperature before the cooler | |

| Air cooler air outlet | Effectiveness of the charge air cooler | |

| Jacket water inlet | Baseline cylinder cooling level | |

| Fuel oil inlet pressure | bar | Health of the fuel supply and filtration train |

| Scavenge air inlet | Intake air temperature to the scavenging blower | |

| Turbocharger inlet EGT | Turbine inlet thermal loading and backpressure | |

| Control air pressure | bar | Availability of pneumatic pressure for engine control |

| Past Cylinder 1 EGT | Autoregressive driver for the target exhaust temperature |

| Model | RMSE | MAE | R2 | Parameters (M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BiLSTM | 0.7052 ± 0.0076 | 0.5654 ± 0.0070 | 0.9473 ± 0.0011 | 3.9315 |

| IBWO-LSTM | 1.0352 ± 0.1948 | 0.8342 ± 0.1650 | 0.8826 ± 0.0467 | 0.2832 |

| NARX | 1.3791 ± 0.2335 | 1.0621 ± 0.1687 | 0.7957 ± 0.0697 | 0.0380 |

| TKAN | 0.7839 ± 0.1703 | 0.6152 ± 0.1225 | 0.9327 ± 0.0313 | 0.3530 |

| BEACON | 0.5905 ± 0.0051 | 0.4713 ± 0.0042 | 0.9496 ± 0.0009 | 7.9253 |

| Model | RMSE | MAE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| BiLSTM-MLP | |||

| BiLSTM-KAN | |||

| KAN-MLP | |||

| BEACON |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kalafatelis, A.S.; Levis, G.; Giannopoulos, A.; Tsoulakos, N.; Trakadas, P. Explainable Predictive Maintenance of Marine Engines Using a Hybrid BiLSTM-Attention-Kolmogorov Arnold Network. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010032

Kalafatelis AS, Levis G, Giannopoulos A, Tsoulakos N, Trakadas P. Explainable Predictive Maintenance of Marine Engines Using a Hybrid BiLSTM-Attention-Kolmogorov Arnold Network. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(1):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010032

Chicago/Turabian StyleKalafatelis, Alexandros S., Georgios Levis, Anastasios Giannopoulos, Nikolaos Tsoulakos, and Panagiotis Trakadas. 2026. "Explainable Predictive Maintenance of Marine Engines Using a Hybrid BiLSTM-Attention-Kolmogorov Arnold Network" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 1: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010032

APA StyleKalafatelis, A. S., Levis, G., Giannopoulos, A., Tsoulakos, N., & Trakadas, P. (2026). Explainable Predictive Maintenance of Marine Engines Using a Hybrid BiLSTM-Attention-Kolmogorov Arnold Network. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010032