Abstract

Submesoscale dynamics are critical modulators of upper-ocean biogeochemistry, yet their net influence on chlorophyll concentrations across seasonal to interannual timescales, particularly within productive regions like the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME), remains poorly understood. This study quantifies these complex relationships by analyzing 22 years (2001–2022) of physical and biological data. We examined the link between surface chlorophyll (CHL) and key physical drivers: sea level anomaly (SLA) and submesoscale intensity, quantified by the Rossby number (Ro). Using both cross-correlation analysis and Generalized Linear Models (GLMs), our analyses reveal a multi-scale set of spatially dependent and time-lagged biogeochemical responses. At the basin scale, a key finding from cross-correlation is a significant positive correlation where high SLA precedes a rise in CHL by approximately six months, indicating a delayed ecosystem response to large-scale physical forcing. At the event scale, GLMs show the specific impact of eddies is critical: short-lived cyclonic eddies correlate with a significant increase in CHL (~4.6%) in the southern zone, while anticyclonic eddies are associated with a pronounced decrease in CHL (~97.7%) in the central zone during the austral winter. These findings demonstrate that both large-scale preconditions and localized submesoscale features are essential drivers of vertical nutrient transport and the distribution of primary productivity within the BCLME.

1. Introduction

The Benguela Current System (BCS) is one of the four major Eastern Boundary Upwelling Systems (EBUS) and ranks among the most productive marine ecosystems on Earth [1]. This high productivity, which sustains a rich food web and vital economic activities such as fisheries, is driven by phytoplankton biomass, for which sea surface chlorophyll (CHL) serves as a primary indicator. However, the spatio-temporal distribution of CHL exhibits significant variability across multiple scales, and its controlling mechanisms, particularly the role of submesoscale processes, remain incompletely understood [2,3,4,5].

The fundamental dynamics of the BCS, extending along the southwestern coast of Africa, are governed by intense coastal upwelling. This process, primarily forced by prevailing equatorward, alongshore winds, brings cold, nutrient-rich deep water to the euphotic zone, thereby fueling primary production [6,7,8]. This productivity is neither spatially uniform nor temporally constant; it is strongly modulated by a mosaic of physical processes. Among these, mesoscale and submesoscale features, such as eddies and fronts, play a critical role in structuring the distribution of nutrients and phytoplankton [9,10].

Key physical indicators allow us to diagnose these dynamics. Sea Level Anomaly (SLA) reveals the presence of mesoscale structures, where negative anomalies are typically associated with nutrient-rich, high-CHL upwelling cells, and positive anomalies mark warmer, oligotrophic waters [9,11]. At finer scales, the Rossby number (Ro)—a dimensionless parameter quantifying the ratio of inertial to Coriolis forces—serves as a proxy for submesoscale activity. High Ro values are linked to flow instabilities that enhance vertical mixing, nutrient redistribution, and, consequently, greater CHL variability [12,13].

The biological impact of eddies is complex and depends on their polarity. In the Southern Hemisphere, cyclonic eddies induce Ekman pumping at their core, uplifting the thermocline and injecting nutrients into the surface layer, which can locally increase CHL concentrations by 30–50% relative to surrounding waters [14]. Conversely, anticyclonic eddies, characterized by surface convergence and a deepened thermocline, have traditionally been viewed as biological deserts. However, recent work has revealed that they can also enhance productivity, either by horizontally transporting productive coastal waters offshore or by stimulating production at their peripheries [5]. This functional duality of eddies remains an active area of research. Despite these advances, a quantitative and integrated understanding of how these different physical processes interact across scales to regulate phytoplankton biomass in the BCS is still lacking.

This study aims to fill this gap by analyzing physical and biological data over a 22-year period (2001–2022). Using high-resolution reanalysis data (GREP), we specifically investigate how mesoscale features and submesoscale activity, proxied by the Rossby number, influence CHL variability. Our objectives are to (1) characterize the coupled seasonal regimes of SLA, Ro, and CHL, and (2) statistically quantify the distinct influence of cyclonic and anticyclonic features on chlorophyll biomass. By clarifying these mechanisms, our work will contribute to a more fundamental understanding of the drivers of productivity in this vital ecosystem.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

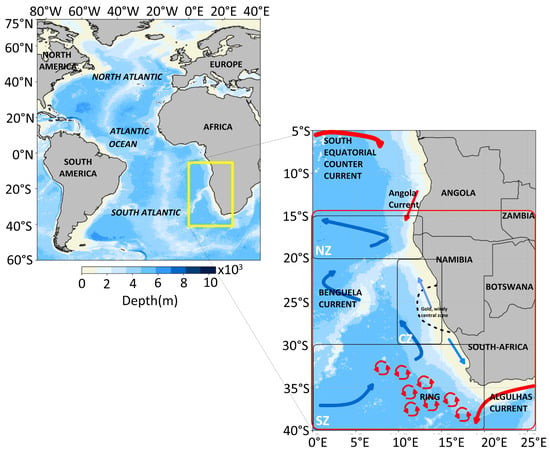

Our study was conducted in the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME), located off the southwestern coast of Africa (Figure 1). The study domain was defined by the coordinates 0° E to 20° E longitude and 15° S to 40° S latitude. This region fully encompasses the Benguela Upwelling System, from the Angola-Benguela Front in the north to its confluence with the Agulhas Current in the south. The area includes the system’s core upwelling cells, primary productivity zones, and high eddy activity, making it an ideal natural laboratory for this investigation.

Figure 1.

Study area delimited by the outputs of the submesoscale motions in the BCLME (red box). The yellow box represents the area around the BCLME, and the red box represents the focal point of the study, submesoscale motions. The black boxes represent, respectively, the northern zone (NZ [15–20° S; 0–13° E]), the central zone (CZ [20–30° S; 10–15° E]), and the southern zone (SZ [30–40° S; 0–20° E]). The solid blue line symbolizes the Benguela Current, and the solid red line symbolizes the Agulhas Current in the south and the Angola Current in the north.

2.2. Datasets

All data were processed for the 22-year period from January 2001 to December 2022 and gridded to a monthly, 0.25° × 0.25° resolution to ensure spatio-temporal consistency.

2.2.1. Biogeochemical Data (Chlorophyll-A)

Surface chlorophyll-a concentrations (CHL, in mg/m3), a proxy for phytoplankton biomass, were obtained from the CMEMS observation-based gridded product (MULTIOBS_GLO_BIO_BGC_3D_REP_015_010). This product synthesizes global in situ observations (e.g., BGC-Argo floats) into a complete 3D field. For this study, we extracted data from the surface layer (0–5 m depth).

2.2.2. Altimetry and Eddy Tracking Data (SLA, Ro1, Ro2)

Sea Level Anomaly (SLA) data were sourced from the CMEMS Level-4 gridded altimetry product (SEALEVEL_GLO_PHY_CLIMATE_L4_MY_008_057). To specifically analyze short-lived eddies, we used the Mesoscale Eddy Trajectory Atlas product from AVISO (META3.2_DT) (Aviso User Service CLS/DOS, 11 rue Hermès, Parc Technologique du Canal F-31520 Ramonville St-Agne, France). This dataset provides daily tracks and properties of individual cyclonic and anticyclonic eddies, including their characteristic rotation velocity (U, in m/s) and length scale (L, in m). These parameters were used exclusively for calculating the eddy-specific Rossby numbers, Ro1 (for cyclonic eddies) and Ro2 (for anticyclonic eddies).

2.2.3. Ocean Model Reanalysis Data (Velocities for Ro)

To characterize the general submesoscale field independent of tracked eddies, surface zonal (u) and meridional (v) velocities, and sea surface height (SSH) were obtained from the GREP (Global Reanalysis multi-model Ensemble Product) high-resolution (1/12°) model simulation (GLOBAL_MULTIYEAR_PHY_001_030). These model outputs were used exclusively for calculating the background flow Rossby number, Ro.

2.3. Calculation of Submesoscale Indices

Three distinct Rossby numbers were calculated to represent different aspects of submesoscale motion:

- Background Flow Rossby Number (Ro): This index represents the intensity of submesoscale motions in the general oceanic flow. It was calculated from the GREP model velocities as the normalized relative vorticity. Using the methods of Li et al. (2022) [15], we can determine the Rossby number in the BCLME for an oceanic flow; it can be approximated by Equation (1):

Ro = |ζ|/|f|

- Eddy-Specific Rossby Numbers (Ro1 and Ro2): To characterize the intensity of individual short-lived eddies, Rossby numbers were calculated for each identified cyclonic (Ro1) and anticyclonic (Ro2) feature using data from the AVISO eddy atlas:

Ro1 = U1/(f ×L1)

Ro2 = U2/(f ×L2)

In this context, U1 and U2 represent the rotation velocities of the eddy, while L1 and L2 denote its characteristic length scales for cyclonic and anticyclonic motions, respectively.

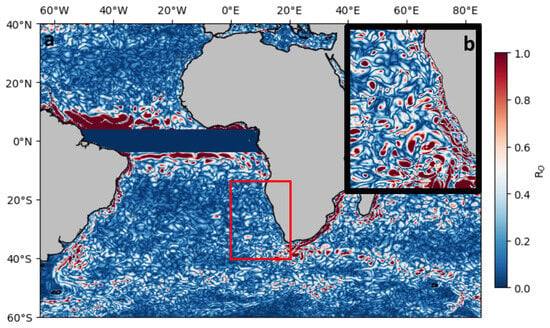

The modeling of the relative vorticity (ζ) takes into account the zonal (u) and meridional (v) velocities of the currents (measured in m/s) within the location (longitude: 0° E to 20° E, latitude: 15° S to 40° S) red box at the associated depth (Figure 2). In this context, u and v are the zonal and meridional velocities in m/s, respectively. We performed the Rossby number estimation using a time series of (u and v) data from 2001 to 2022, encompassing 0–5 m depth in the BCLME (Figure 2). Velocities (u) and (v) from the GREP model [16] were used to explore submesoscale (Ro) motions in this study. To represent these processes, GREP applied one-directional nesting to boost the accuracy of the main computational grid. The outer domain includes the Northwest Atlantic and Northeast Pacific Oceans (Figure 2a) with reduced horizontal detail (LR) of 1/4°, while the inner domain encompasses the BCLME (Figure 2b) with increased detail (HR) of 1/12° (approximately 8 km).

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of Rossby number |Ro| values at 5 m depth, contrasting results from (a) the lower resolution model and (b) the higher resolution simulation. The target investigation zone is marked with a black rectangular boundary labeled as box (b).

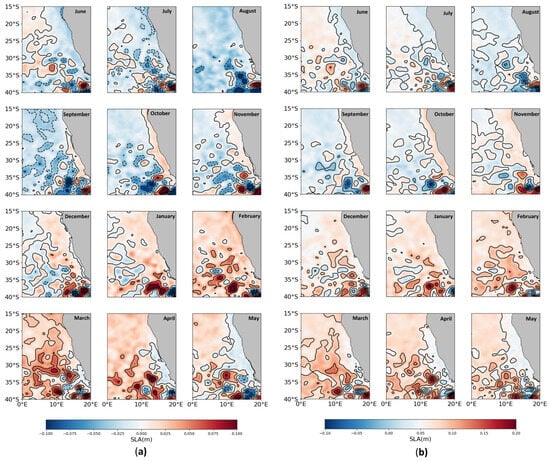

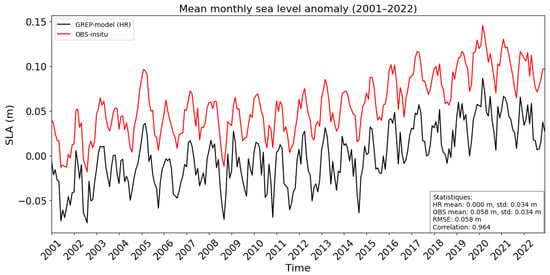

Submesoscale movements are correlated with SSH anomalies in this area (Figure S1). The monthly mean SLA is compared between GREP HR (2001–2022) and AVISO + CMEMS (2001–2022) in Figure 3a and Figure 3b, respectively. Both results show that low SLA waters develop faster in the austral winter (Figure 3). Overall, the monthly SLA variation in GREP is consistent with the in situ observation (AVISO + CMEMS) results, illustrating the model’s simulation skill (Figure 4). It is noteworthy that the simulated SLA is milder than that of AVISO + CMEMS, which could be explained by the differences between the initial SLA of the model and that of AVISO. As we focused on seasonal variations, this difference in SLA had less impact on the results of our study. To represent the anomaly SSH, we use SLA, calculated from SSH and MSS with Equation (4).

where MSS is the mean sea surface level.

SLA = SSH − MSS

Figure 3.

Monthly mean SSH anomalies from the Global Reanalysis multi-model Ensemble Product higher resolution (1/12°) (a) and from observation (AVISO + CMEMS) (b).

Figure 4.

Sea Level Anomaly for 2001–2022, evolution of monthly mean value from in situ observation (red line), and GREP-model higher resolution simulation (black line).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Our statistical methodology aimed to quantify the relationship between the physical predictors (SLA, Ro, Ro1 and Ro2) and the biological response variable (CHL).

First, an exploratory data analysis was conducted to generate summary statistics (mean, standard deviation, median, etc.) for each variable, stratified by season (Table 1). The exploratory statistical evaluation generated fundamental summary metrics, including averages, dispersion measures, and distribution characteristics such as mean values, standard deviations (SD), and percentiles (from 25% through maximum values of 100%) for each variable, stratified by subzone (Supplementary Tables S1–S5). Second, we analyzed the SSH-CHL cross-correlation. To minimize multicollinearity and variable redundancy, a Pearson rank correlation analysis was performed on the predictor variables [17] (Figure S2). In cases of strong correlation (Pearson coefficient > 0.7), only one variable from the pair was retained for subsequent modeling [18].

Table 1.

Descriptive statistical analysis of CHL, SSH, Ro, Ro1 and Ro2.

The core of the analysis was the application of Generalized Linear Models (GLM) to investigate the relationships [19,20]. Given the log-normal distribution often observed in CHL data, the following model forms were tested:

Log10(CHL) ~ Ro

Log10(CHL) ~ Ro1

Log10(CHL) ~ Ro2

The GLM uses a Gaussian distribution with an identity link function, making it similar to a standard linear regression but within the more flexible framework of GLMs. The model explains the variations in the logarithm of chlorophyll (log10(CHL)) using explanatory variables (Ro1, Ro2, and Ro) across seasons and subzones. During the main austral winter period, the model used the predictor variable Ro1 in the southern zone (SZ), the predictor variable Ro2 in the central zone (CZ), and Ro for the three regions (SZ, CZ and NZ). Prior investigations have confirmed the efficacy of this analytical model in comparable contexts, emphasizing its capacity to identify and represent intricate correlations and interactions within the dataset [21,22,23]. All data processing, calculations, and statistical analyses were performed using custom Python3.11.9 scripts utilizing libraries such as matplotlib, corrplot, and statsmodels.

3. Results

3.1. Nonlinearity Variability of SSH Anomalies

The monthly SSH anomaly fields (Figure 3b) produced by merging measurements from two altimeter satellites (AVISO and Global Ocean Gridded L4 Sea Surface Heights and Derived Variables Reprocessed Copernicus Climate Service) (https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00145) and the high-resolution monthly SLA fields produced by the GREP model (Figure 3a) reveal propagating structures. Earlier identified as Rossby waves, the phenomena are in fact nonlinear rotation systems (“mesoscale eddies”) having radii of approximately 50 km [24]. Since these mesoscale features propagate northwestward at a speed approximately equal to that of long Rossby waves [25], for individual altimeter observations with a low SSH anomalies field, these phenomena can be confused with Rossby waves. The Rossby number of a mesoscale phenomenon (U/(fL)) is defined as the ratio between the fluid rotation velocity U and the inertial and Coriolis forces (f) of the characteristic. When U/(fL) << 1, Coriolis forces dominate and the motion tends to be geostrophic. When U/(fL) = (0.4–0.5), the vertical and horizontal mixing capacity is substantially increased, which intensifies nutrient exchange; eddies can induce large vertical motions and contribute significantly to the exchange between surface and deep waters; and nonlinear effects become important enough to modify their trajectory compared to the simple propagation of Rossby waves [10,24,26]. South of 30° S, 75% of short-lived cyclonic eddies monitored for ≥4 days have a U/(fL) ≥ 0.51 (Table S1). In the center region, 10–15° E to 20–30° S, 75% of short-lived cyclonic eddies have a U/(fL) ≥ 0.41 (Table S2). However, even between 15° and 40° S latitude, 75% of submesoscale motion (high resolution) has a Ro ≥ 0.46 (Tables S3, S5 and S6).

3.2. Relationship Between Sea Level Anomaly and Chlorophyll

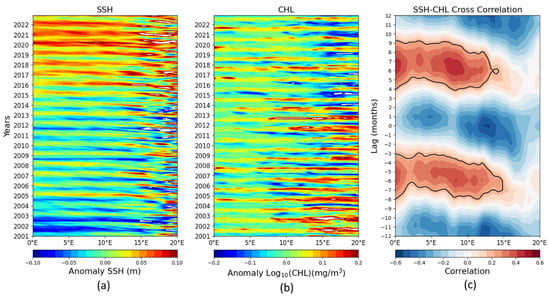

The opposing seasonal cycles of SLA and CHL suggest a strong physical control on biological productivity. Correlations between SSH and chlorophyll are particularly interesting because they can indicate how the physical structure of the ocean (represented by SSH) influences biological productivity (chlorophyll). A high SSH anomaly can indicate warmer, stratified waters, potentially poor in nutrients. A low SSH anomaly can indicate nutrient-rich upwelling promoting phytoplankton growth (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

SSH anomalies and CHL in the BCLME to illustrate the annual cycle. Spatial and temporal variability of filtered SSH and log10(CHL) observations along 15–40° S between 0° E and 20° E. The time-longitude sections of the westward propagation of the period 2001–2022 analyzed here are presented for (a) SSH, (b) log10(CHL), and (c) SSH-CHL cross-correlation. The vertical axis represents time lags (“lag months”), ranging from approximately −12 to +12 months. Red areas surrounded by black outlines (around +6 months and −6 months) indicate a significant positive correlation, suggesting that an increase in SSH is associated with an increase in CHL approximately 6 months later, and vice versa. Blue areas (around 0 and ±12 months) indicate a negative correlation, suggesting that an increase in SSH is associated with a decrease in CHL at these time lags.

The alternating correlation bands visible in the plot of Figure 5c likely suggest areas where these relationships change depending on the specific ocean dynamics of the study region. The positive lag (top panel) indicates that anomaly SSH changes precede CHL changes; the negative lag (bottom panel) indicates that CHL changes precede SSH changes; and zero lag (center) shows the instantaneous correlation, with no time lag.

Overall, both sea level anomaly (SLA) and chlorophyll concentration exhibit significant seasonal variations. This reflects their large-scale temporal changes, which represent the dominant mode of variability. There is a strong correspondence between SLA and chlorophyll, with the maximum correlation coefficient observed at a six-month lag.

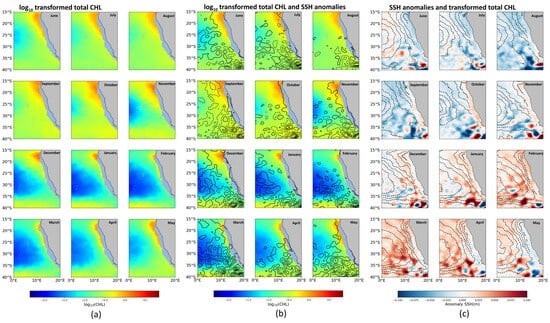

3.3. Monthly Spatial-Temporal Variability of CHL and Anomaly SSH

The distribution of CHL values at an average depth of 0 to 5 m between 2001 and 2022 in the BCLME region shows that the months of June, July, August, September, October, and November systematically have higher CHL than December, January, February, March, April, and May (Figure 6a). We used a logarithmic scale log10(CHL) to better visualize the CHL distributions (Figure 6b). Specifically, average CHL in June, July, August, and September shows an increase, ranging from ~0.26 to 0.38 mg/m3; while the months of October, November, December, January, February, and March show a significant decrease, ranging from ~0.31 to 0.13 mg/m3. In April and May it shows a slight increase ranging from ~0.17 to 0.22 mg/m3 (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Spatial distribution of monthly average (2001–2022) of observed CHL and SSH in the BCLME: (a) 22-year monthly average of log10(CHL) for CHL, expressed in mg/m3, with a contour interval of log10(CHL) = 0.1, increasing northward and southward; (b) map showing log10(CHL) in color, with contours of positive and negative SSH anomalies (solid and dashed lines, respectively) at 0.025 m intervals, excluding the zero contour; and (c) same as (b), except that the SSH anomaly is shown in color with contours of log10(CHL) at the same interval as in (a).

Figure 7.

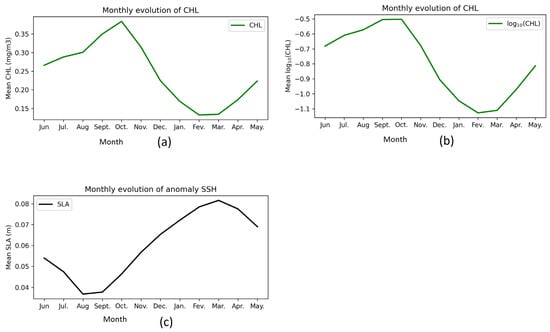

Seasonal variation of: (a) monthly evolution of mean chlorophyll concentration at 0–5 m depth from 2001 to 2022 in the BCLME; (b) monthly evolution of average log-transformed chlorophyll (log10(CHL)); and (c) monthly evolution of mean sea level anomaly (SLA) from 2001 to 2022 in the BCLME.

The average values of SSH anomalies in the BCLME from 2001 to 2022 indicate that the months of December, January, February, March, April, and May systematically present a higher SSH anomaly than the months of June, July, August, September, October, and November (Figure 6c). Specifically, the average SSH anomaly in June, July, August, and September shows a decrease ranging from ~0.053 to 0.037 m; while in the months of October, November, December, January, February, and March, there is a significant increase ranging from ~0.047 to 0.081 m. In April and May it shows a slight decrease from 0.77 to 0.006 m (Figure 7).

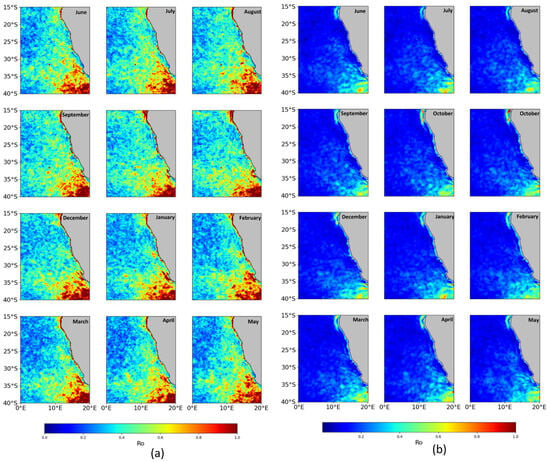

3.4. Horizontal Distribution of Submesoscale Motions

Submesoscale currents are defined by their Rossby number (Ro = ζ/f), indicating that their relative vorticity (ζ = ∂v/∂x − ∂u/∂y) approaches equivalence with Coriolis forces (f) [11,15]. Elevated Ro configurations, appearing as elongated filament structures, are evident in spatiotemporal mapping sequences, suggesting that submesoscale motions occur with greater frequency and distribution in the southern BCLME (Figure 8). Compared to higher resolution (HR) (Figure 8a), submesoscale motions (Ro) are largely underestimated in low resolution (LR) (Figure 8b), and other submesoscale movements occupy the domain.

Figure 8.

Spatial distribution monthly of Rossby number |Ro| from GREP simulation (2001–2022) at 0–5 m depth, higher resolution (a), and lower resolution (b).

Using the methods of Chelton and Schlax (2011) [24,25], we can determine the Rossby number in the BCLME for short-lived mesoscale eddies by (Ro = U/(fL)); it can be approximated by Ro1 (Rossby number for short-lived cyclonic eddies) and Ro2 (Rossby number for short-lived anticyclonic eddies).

The monthly distribution of Ro at the 0–5 m depth in the BCLME between 2001 and 2022 does not show significant monthly differences (Figure 8a). The distribution of Ro1 and Ro2 in the BCLME between 2001 and 2022 not show significant monthly differences (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

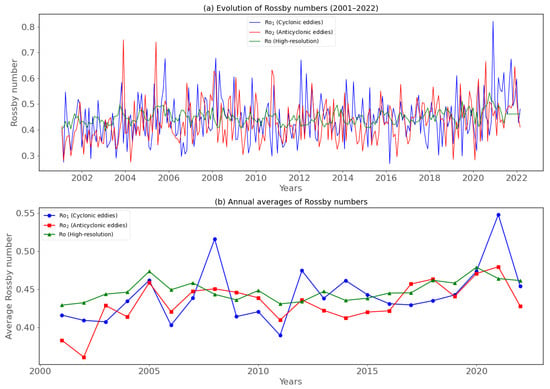

Temporal monthly evolution of the Rossby number (2001–2022). (a) Evolution of raw Rossby numbers; and (b) annual averages of Rossby numbers. Where Ro1 is the Rossby number generated by short-lived cyclonic eddies (blue line), Ro2 is the Rossby number generated by short-lived anticyclonic eddies (red line), and Ro is the Rossby number (HR) (green line) from the GREP model.

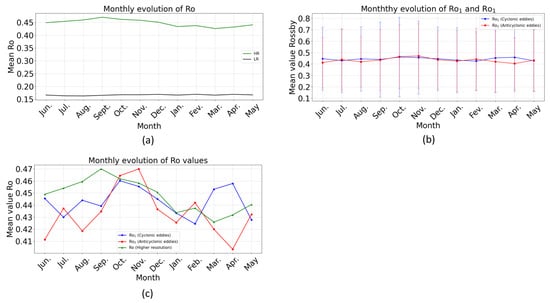

In June, July, August, September, October, and November, the Ro (high resolution) in the BCLME ranges from ~0.44 to 0.47. In December, January, February, March, and April, it ranges from ~0.43 to 0.45 (Figure 10a). In June, July, August, September, October, and November, the value of Rossby Ro1 (generated by short cyclonic) in the BCLME ranges from ~0.18 to 0.82. In December, January, February, March, and April, it ranges from ~0.16 to 0.77 (Figure 10b). The average distribution of Ro in the BCLME between 2001 and 2022 displays consistently moderate monthly fluctuations, varying between ~0.4 and 0.544 depending on the seasons (Figure 10c). The average Ro1 distribution in the BCLME between 2001 and 2022 displays consistently moderate monthly fluctuations, varying between ~0.43 and 0.46 depending on the season (Figure 10c).

Figure 10.

Monthly evolution of submesoscale motion (2001–2022) in BCLME. (a) Temporal sequence of the spatially averaged |Ro| at 0–5 m depth calculated across the entire domain from higher resolution (HR) (green line) and lower resolution (LR) (black line) simulation. (b) Monthly evolution of Ro1 (blue line) and Ro2 (red line). (c) Average monthly evolution of Rossby numbers Ro1 (blue line), Ro2 (red line), and Ro (green line).

In June, July, August, September, October, and November, the Rossby number Ro2 (generated by short anticyclonics) in the BCLME ranges from ~0.17 to 0.75. In December, January, February, March, and April, it varies from ~0.19 to 0.71 (Figure 10b). The average Ro2 distribution in the BCLME between 2001 and 2022 displays consistently moderate monthly fluctuations, varying between ~0.43 and 0.47 depending on the season (Figure 10c).

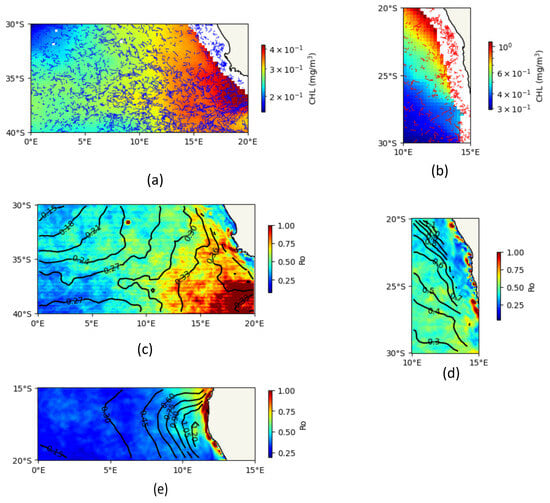

3.5. Seasonal Spatial–Temporal Variability of CHL, SLA and Ro

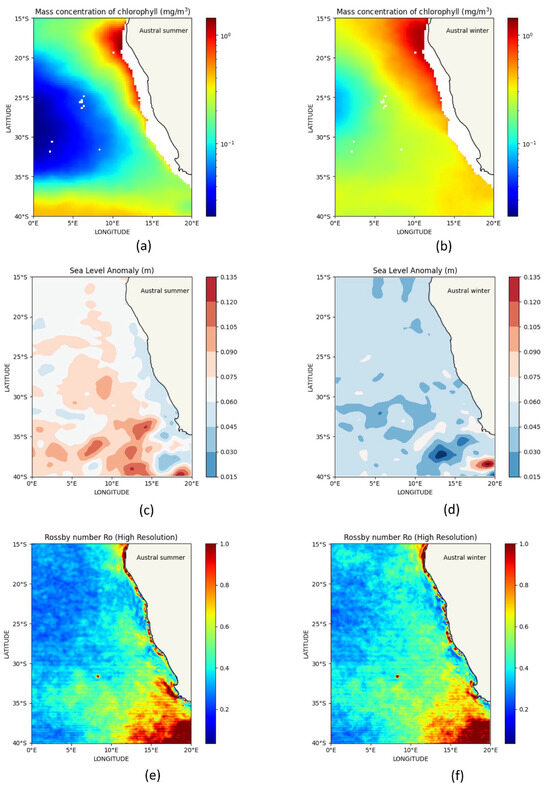

The average spatial distribution from 2001 to 2022, at an average depth of 0 to 5 m, shows that in the BCLME, average CHL varies from ~0.10 mg/m3 to 0.18 mg/m3 during the austral summer (Figure 11a), while during the austral winter, it ranges from ~0.30 mg/m3 to 0.32 mg/m3 (Figure 11b). Average SSH anomaly varies from ~0.067 m to 0.074 m during the austral summer (Figure 11c), while during the austral winter it varies from ~0.043 m to about 0.046 m (Figure 11d). The average Rossby number Ro varies from ~0.41 to 0.43 during the austral summer (Figure 11e), while during the austral winter it ranges from ~0.42 to 0.46 (Figure 11f).

Figure 11.

Spatial distribution of seasonal average (2001–2022) from 0 to 5 m depth in the BCLME and around the Southern Africa–Southeast Atlantic Ocean. (a) CHL distribution in austral summer, (b) CHL distribution in austral winter, (c) SLA distribution in austral summer, (d) SLA distribution in austral winter, (e) Ro distribution in austral summer, and (f) Ro distribution in austral winter.

3.6. Quantifying the Impact of Submesoscale Motions on Chlorophyll

To isolate the specific influence of submesoscale motions, we applied Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) to quantify the relationship between the different Rossby number indices and CHL concentration.

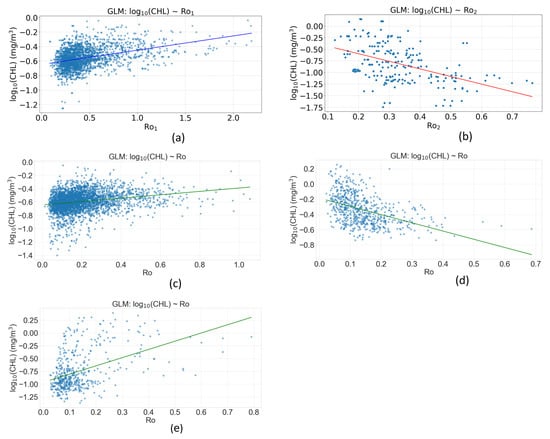

3.6.1. Short-Lived Mesoscale Eddies (Ro1 and Ro2) Influence on CHL

The GLM uses a Gaussian distribution with an identity link function (Figure 12a), making it similar to a standard linear regression, but within the more flexible framework of GLMs. The model explains the variations in the logarithm of chlorophyll (log10(CHL)) using an explanatory variable (Ro1), during the main austral-winter period in the southern zone (0–20° E, 30–40° S). Both coefficients (constant and Ro1) are highly significant with p-values < 0.001, indicating that these parameters are different from zero with very high statistical certainty. The constant (0.0188) represents the estimated mean value of log10(CHL) when Ro1 is equal to zero. The coefficient of Ro1 (0.0195) indicates that a one-unit increase in Ro1 is associated with an average increase of 0.0195 units in log10(CHL), all other things being equal. Since the dependent variable is in logarithmic (log10) scale, this implies that each one-unit increase in Ro1 multiplies the original (untransformed) chlorophyll by about 100.0195 ≈ 1.046 mg/m3, an increase of about 4.6%. The pseudo R2 of 0.1602 suggests that the model explains about 16% of the variance in the data, which is relatively modest. The model converged in only 3 iterations, indicating good numerical stability (Table 2).

Figure 12.

GLM-derived effects of the submesoscale motions on log10(CHL), from models constructed for (a) Ro1 in the southern zone; (b) Ro2 in the central zone; (c) Ro in the southern zone; (d) Ro in the central zone; and (e) Ro in the northern zone. Average Ro1 with the blue line, average Ro1 with the red line, and average Ro with the green line.

Table 2.

GLM result log10(CHL) ~ Ro1. Winter (July–October)—Southern zone (0–20° E to 30–40° S)—short-lived cyclonic-eddies.

Figure 12b presents a Gaussian-distributed GLM with identity link function exploring the relationship between the logarithm of chlorophyll (log10(CHL)) and the explanatory variable Ro2, during the main period of the austral winter observed in the central zone (20–30° E, 10–15° S). The sample size is substantial (4140 observations). Both coefficients (constant and Ro2) are extremely significant with p-values close to zero and very high z-statistics in absolute value (−16.1 and −34.7), indicating that these parameters are different from zero with very high statistical certainty. The constant (−0.269) represents the estimated mean value of log10(CHL) when Ro2 is equal to zero. This negative value indicates that, when Ro2 = 0, the chlorophyll concentration is about 10−0.269 ≈ 0.54 mg/m3 (returning to the original scale). The coefficient of Ro2 (−1.639) shows a strong negative relationship: for every one-unit increase in Ro2, log10(CHL) decreases by an average of 1.639 units. In terms of the original (non-logarithmic) scale, this means that every one-unit increase in Ro2 multiplies chlorophyll by about 10−1.639 ≈ 0.023 mg/m3, or about a 97.7% reduction in chlorophyll concentration. The pseudo R2 of 0.2533 suggests that the model explains about 25.33% of the variance in the data. The high negative log-likelihood (−1746.6) and high deviance (563.61) suggest that, despite the significance of the coefficients, the overall model fit could be improved (Table 3).

Table 3.

GLM result log10(CHL) ~ Ro2. Winter (July–October)—Central zone (20–30° E to 10–15° S)—short-lived anticyclonic eddies.

3.6.2. Impact of Background Submesoscale Flow (Ro)

The influence of the background submesoscale flow (Ro) on CHL is spatially and seasonally dependent (Figure 12c–e).

During the austral winter in the southern zone, a positive relationship is observed between Ro and CHL (Figure 12c). The Generalized Linear Model (GLM) revealed a significant positive effect of the Ro parameter on chlorophyll-a concentration (log10_chl) (β = 0.254, p < 0.001; Table 4). The 95% confidence interval for this coefficient [0.216–0.291] excluded zero, confirming the robustness of this relationship. However, the model’s pseudo R2 was 0.053, indicating that the Ro parameter alone explained a modest portion of the total chlorophyll variance in the study region.

Table 4.

GLM result log10(CHL) ~ Ro2. Winter (July–October)—Central zone (20–30° E to 10–15° S)—Submesoscale Flow (Ro).

Conversely, in the central zone during winter and the northern zone during summer, the GLM revealed a negative or poorly defined trend between the Rossby number (Ro) and log-transformed chlorophyll-a concentration (log10_chl) (Figure 12d,e). This may indicate regions where increased stratification associated with higher Ro values (less rotational influence) limits nutrient supply or where other processes dominate chlorophyll variability.

4. Discussion

This study provides a quantitative, long-term analysis of the distinct roles that mesoscale and submesoscale features play in modulating phytoplankton biomass in the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem. Our results demonstrate that beyond the primary seasonal cycle of upwelling, these dynamic features create a complex mosaic of biological productivity. The key findings are (1) the opposing, seasonally dependent impacts of cyclonic and anticyclonic eddies and (2) the spatially variable influence of the background submesoscale flow on chlorophyll concentrations.

4.1. The Duality of Eddies: Nutrient Pumps vs. Biological Deserts

Our analysis quantitatively confirms the opposing biogeochemical signatures of cyclonic and anticyclonic eddies during the main austral-winter period (July–October). In the southern BCLME (0–20° E to 30–40° S) (Figure 13a), we found a significant positive relationship between the cyclonic Rossby number (Ro1) and CHL, with a 4.6% increase in biomass per unit increase in Ro1. This discovery is consistent with established theories of eddy dynamics. The moderate Ro1 values observed (often ≥ 0.5) indicate a regime where inertial forces are significant, favoring strong upwelling at the cyclone’s core [27]. As shown by Zhang and McGillicuddy (2023), such dynamics induce efficient vertical nutrient pumping, which can enhance chlorophyll concentrations by 35–40% compared to ambient waters [28,29]. Our more modest value of 4.6% likely reflects the monthly temporal averaging of our data but nonetheless confirms that these cyclones act as persistent, localized nutrient pumps that stimulate primary production and can favor the development of diatom-dominated phytoplankton assemblages [30].

Figure 13.

Relationships between CHL and submesoscale motion between 2001 and 2022. (a) Spatial distribution of trajectories of short-lived cyclonic eddies (blue scatter) superimposed on monthly upper-ocean chlorophyll (in color) in the southern zone (0–20° E to 30–40° S) during austral winter. (b) Spatial distribution of trajectories of short-lived anticyclonic eddies (red scatter) superimposed on monthly upper-ocean chlorophyll (in color) in the central area (10–15° E to 20–30° S) during austral winter. (c) Spatial distribution of monthly CHL (solid black contour) superimposed on monthly Ro (in color) in the southern zone (0–20° E to 30–40° S) during the austral winter. (d) Spatial distribution of monthly CHL (solid black contour) superimposed on monthly Ro (in color) in the central area (10–15° E to 20–30° S) during austral winter. (e) Spatial distribution of monthly CHL (solid black contour) superimposed on monthly Ro (in color) in the northern zone (0–13° E to 15–20° S) during austral summer.

Conversely, our results show a dramatic negative impact of anticyclonic eddies (Ro2) on CHL in the central zone (10–15° E to 20–30° S) (Figure 13b), with a ~97.7% reduction in biomass. This powerful suppression of productivity confirms their classical characterization as biological deserts. The low Ro2 values (≤0.41) are indicative of a rotationally dominated regime with pronounced downwelling at the core, which deepens the nutricline and leads to oligotrophic surface conditions [31]. It is important to note, however, that this result likely captures the dynamics of the eddy core. Other studies have highlighted that some anticyclones with moderate Ro2 can develop high CHL at their peripheries due to horizontal advection or frontogenesis [32]. Our findings, focused on the eddy’s intrinsic rotational intensity, emphasize the profoundly nutrient-depleted nature of their centers, a condition that favors dinoflagellates and coccolithophorids adapted to stratified environments [33].

4.2. The Context-Dependent Role of the Background Submesoscale Flow

The influence of the background submesoscale field (Ro), which includes fronts and filaments, was found to be highly dependent on the geographic region and season. In the southern BCLME during winter, higher Ro was associated with higher CHL (Figure 13c). This region is dynamically active, and our results suggest that high Ro values (often ≥0.61) are indicative of pronounced fronts and filaments. According to Ruiz et al. (2019) and Chaitanya et al. (2021), such features intensify primary productivity by injecting nutrients into the euphotic zone via secondary circulation [31,33]. Our findings support this, showing that in this energetic part of the system, submesoscale turbulence acts as a net driver of nutrient supply.

In contrast, the relationship was negative or weak in other regions and seasons (Figure 13d,e). This suggests that in more stratified environments, an increase in Ro (indicating a departure from geostrophy) might enhance vertical stratification, thereby limiting nutrient flux from below and suppressing productivity. This highlights that the net biogeochemical impact of submesoscale motions is not universal but is a function of the background ocean state and the dominant physical processes at play.

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

While this study provides a robust basin-scale quantification, some limitations should be acknowledged. First, our use of monthly mean data, while necessary for a long-term climatological analysis, inevitably smooths out the ephemeral, high-frequency nature of submesoscale events. Future work using daily model outputs and satellite data could reveal more extreme biological responses. Our results highlight the predominant role of sub-mesoscale dynamics. However, this influence must be considered in the context of other forcing factors. For example, in the northern part of the system, Faeron et al. (2023) showed that the SST-CHL relationship is complicated by stratification, and intrusions of Angolan water can modulate phytoplankton composition, as demonstrated by Quiatuhanga et al. (2025) [6,34]. Future studies could seek to integrate these thermodynamic and biogeographical processes into models to refine our understanding.

Second, our statistical approach identifies strong correlations but does not prove causation. The complex interactions between vertical mixing, horizontal advection, and biological uptake rates require further investigation using more mechanistic tools, such as coupled biophysical models with particle tracking simulations (e.g., Lagrangian analysis).

Finally, the dramatic ~97.7% CHL reduction in anticyclones, while statistically significant, warrants further investigation with different modeling approaches (e.g., composite analysis, nonlinear models) to confirm the magnitude of this effect and explore its spatial structure from the eddy core to its periphery.

5. Conclusions

This study sought to disentangle the complex physical drivers of chlorophyll variability in the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem. By analyzing 22 years of data, we have demonstrated that the system’s productivity is governed by a combination of processes acting on fundamentally different spatial and temporal scales. Our findings move beyond a simple, monolithic view of ocean productivity, revealing a more nuanced reality.

The primary conclusion of this work is the discovery of a dual-control mechanism. At the basin scale, we identified a slow, predictive relationship where high sea level anomalies act as a precursor to increased chlorophyll concentrations approximately six months later. Superimposed on this slow seasonal rhythm is a fast, event-driven control exerted by short-lived eddies. Our results confirm their opposing roles with unprecedented long-term statistical clarity: cyclonic eddies provide localized boosts to productivity in the southern BCLME, while anticyclonic eddies create significant biological deficits in the central zone, particularly during the austral winter.

The implications of this multi-scale control are significant. It suggests that forecasting the location and timing of productivity hotspots—a critical need for fisheries management—requires a hybrid approach that considers both the large-scale oceanic state and the immediate “weather” of the eddy field. Furthermore, our findings provide a quantitative framework for assessing the impact of climate change on the BCLME’s food web. Any future climate-driven shift in the statistics of eddy generation—for instance, a change in the frequency of cyclones versus anticyclones—can be expected to directly alter the ecosystem’s primary production capacity.

While this study provides a robust large-scale view, future research should aim to validate these findings with in situ measurements to directly quantify the vertical nutrient fluxes within these dynamic features. Nonetheless, our work establishes that the biological productivity of the BCLME is not a simple function of upwelling but an intricate patchwork shaped by the interplay of slow seasonal rhythm and rapid, localized eddy-driven injections and suppressions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jmse13122409/s1, Figure S1: Correlation between SLA and Rossby numbers (2001–2022); Figure S2: Correlation matrix between Ro (higher resolution simulate), Ro1 (short-lived cyclonic eddies) and Ro2 (short-lived anticyclonic eddies); Table S1: Descriptive statistical analysis of Ro1, log10(CHL) and SSH-anomaly in southern zone (0–20° E to 30–40° S), July–October; Table S2: Descriptive statistical analysis of Ro2, log10(CHL) and SSH-anomaly central zone (10–15° E to 20–30° S), July–October; Table S3: Descriptive statistical analysis of Ro, log10(CHL) and SSH-anomaly southern zone (0–20° E to 30–40° S), July–October; Table S4: Descriptive statistical analysis of Ro1, log10(CHL) and SSH-anomaly central zone; Table S5: Descriptive statistical analysis of Ro2, log10(CHL) and SSH-anomaly in northern zone (0–13° E to 15–20° S), March–May.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization E.E.B.A. and S.H.; methodology, E.E.B.A., E.N.N. and R.K.; software, E.E.B.A.; validation, E.E.B.A., S.H. and P.N.A.; formal analysis, E.E.B.A.; investigation, R.K.; resources, E.E.B.A. and S.H.; data curation, E.E.B.A.; writing—original draft preparation, E.E.B.A. and S.H.; writing—review and editing, E.E.B.A., S.H. and P.N.A.; visualization, E.N.N.; supervision, S.H.; project administration, S.H.; funding acquisition, S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant number 2024YFD2400602) for Song Hu (S.H.) and by the Shanghai Government Scholarship Council (SGS) scholarship for Ekoué (E.E.B.A.).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere thanks to CMEMS for providing observation data (mass concentration Chlorophyll and sea level anomaly) and ocean model data (zonal and meridional velocities). We also thank AVISO for in situ observation data (short-lived mesoscale eddy parameters and sea level anomaly).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GREP | Global Reanalysis Multi-Model Ensemble Product |

| CMEMS | Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service |

| AVISO | Satellite Altimetry Data |

| Eq. | Equation |

References

- Louw, D.C.; Van Der Plas, A.K.; Mohrholz, V.; Wasmund, N.; Junker, T.; Eggert, A. Seasonal and Interannual Phytoplankton Dynamics and Forcing Mechanisms in the Northern Benguela Upwelling System. J. Mar. Syst. 2016, 157, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demarcq, H.; Barlow, R.; Hutchings, L. Application of a Chlorophyll Index Derived from Satellite Data to Investigate the Variability of Phytoplankton in the Benguela Ecosystem. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 2007, 29, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerwath, S.E.; Winker, H.; Götz, A.; Attwood, C.G. Marine Protected Area Improves Yield without Disadvantaging Fishers. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, H.; Ito, S.; Sasaki, K. Dependence of Horizontal Characteristic Scale of Chlorophyll a Distribution on Eddy Activity at the Mid-Latitudes of Global Oceans. ESS Open Arch. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, T.; Barlow, R.G.; Brewin, R.J.W. Long-Term Trends in Phytoplankton Chlorophyll a and Size Structure in the Benguela Upwelling System. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2019, 124, 1170–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearon, G.; Herbette, S.; Cambon, G.; Veitch, J.; Meynecke, J.-O.; Vichi, M. The Land-Sea Breeze Influences the Oceanography of the Southern Benguela Upwelling System at Multiple Time-Scales. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1186069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shillington, F.A. The Benguela upwelling system off southwestern Africa (16, E). In The Sea: Ideas and Observations on Progress in the Study of the Seas; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ragoasha, M.N.; Herbette, S.; Veitch, J.; Cambon, G.; Reason, C.J.C.; Roy, C. Inter-Annual Variability of the Along-Shore Lagrangian Transport Success in the Southern Benguela Current Upwelling System. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2022, 127, e2020JC017114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Carrasco, I.; Orfila, A.; Rossi, V.; Garçon, V. Effect of Small Scale Transport Processes on Phytoplankton Distribution in Coastal Seas. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.N.; Tandon, A.; Mahadevan, A. Submesoscale Processes and Dynamics. In Geophysical Monograph Series; Hecht, M.W., Hasumi, H., Eds.; American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; Volume 177, pp. 17–38. ISBN 978-0-87590-442-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hardman-Mountford, N.J.; Richardson, A.J.; Agenbag, J.J.; Hagen, E.; Nykjaer, L.; Shillington, F.A.; Villacastin, C. Ocean Climate of the South East Atlantic Observed from Satellite Data and Wind Models. Prog. Oceanogr. 2003, 59, 181–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidov, D. Northwest Atlantic Regional Ocean Climatology Version 2; NOAA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halo, I.; Raj, R.P.; Korosov, A.; Penven, P.; Johannessen, J.A.; Rouault, M. Mesoscale Variability, Critical Latitude and Eddy Mean Properties in the Tropical South-East Atlantic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2023, 128, e2022JC019050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.-P.; Umlauf, L.; Dräger-Dietel, J.; North, R.P. Diurnal Variability of Frontal Dynamics, Instability, and Turbulence in a Submesoscale Upwelling Filament. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2021, 51, 2825–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Cheng, X.; Jing, Z.; Cao, H.; Feng, T. Submesoscale Motions and Their Seasonality in the Northern Bay of Bengal. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2022, 41, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lellouche, J.-M.; Bourdalle-Badie, R.; Greiner, E.; Garric, G.; Melet, A.; Bricaud, C.; Legalloudec, O.; Hamon, M.; Candela, T.; Regnier, C.; et al. The Copernicus Global 1/12° Oceanic and Sea Ice Reanalysis. In EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts; EGU: Munich, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Akoglu, H. User’s guide to correlation coefficients. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 18, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lezama-Ochoa, N.; Lopez, J.; Hall, M.; Bach, P.; Abascal, F.; Murua, H. Spatio-Temporal Distribution of Spinetail Devil Ray Mobula Mobular in the Eastern Tropical Atlantic Ocean. Endanger. Species Res. 2020, 43, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venables, W.N.; Dichmont, C.M. GLMs, GAMs and GLMMs: An Overview of Theory for Applications in Fisheries Research. Fish. Res. 2004, 70, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuur, A.F.; Mira, A.; Carvalho, F.; Ieno, E.N.; Saveliev, A.A.; Smith, G.M.; Walker, N.J. Negative Binomial GAM and GAMM to Analyse Amphibian Roadkills. In Mixed Effects Models and Extensions in Ecology with R; Statistics for Biology and Health; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 383–397. ISBN 978-0-387-87457-9. [Google Scholar]

- Roshan, S.; DeVries, T. Efficient Dissolved Organic Carbon Production and Export in the Oligotrophic Ocean. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessouri, F.; McWilliams, J.C.; Bianchi, D.; Sutula, M.; Renault, L.; Deutsch, C.; Feely, R.A.; McLaughlin, K.; Ho, M.; Howard, E.M.; et al. Coastal Eutrophication Drives Acidification, Oxygen Loss, and Ecosystem Change in a Major Oceanic Upwelling System. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2018856118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubis, M.Z.; Ghazali, M.; Simanjuntak, A.V.H.; Riama, N.F.; Pasma, G.R.; Priatna, A.; Kausarian, H.; Suryadarma, M.W.; Pujiyati, S.; Simanungkalit, F.; et al. Decadal and Seasonal Oceanographic Trends Influenced by Climate Changes in the Gulf of Thailand. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2025, 28, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelton, D.B.; Schlax, M.G.; Samelson, R.M. Global Observations of Nonlinear Mesoscale Eddies. Prog. Oceanogr. 2011, 91, 167–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelton, D.B.; Schlax, M.G.; Samelson, R.M.; De Szoeke, R.A. Global Observations of Large Oceanic Eddies. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, 2007GL030812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévy, M.; Ferrari, R.; Franks, P.J.S.; Martin, A.P.; Rivière, P. Bringing Physics to Life at the Submesoscale. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39, 2012GL052756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevan, A. The Impact of Submesoscale Physics on Primary Productivity of Plankton. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2016, 8, 161–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Ding, M.; Meng, Y.; Zheng, W.; Lin, P.; Yu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, P.; Chen, J. Forecasting Ocean Mesoscale Eddies in the Northwest Pacific in a Dynamic Ocean Forecast System. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGillicuddy, D.J. Mechanisms of Physical-Biological-Biogeochemical Interaction at the Oceanic Mesoscale. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2016, 8, 125–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousselet, L.; Doglioli, A.M.; De Verneil, A.; Pietri, A.; Della Penna, A.; Berline, L.; Marrec, P.; Grégori, G.; Thyssen, M.; Carlotti, F.; et al. Vertical Motions and Their Effects on a Biogeochemical Tracer in a Cyclonic Structure Finely Observed in the Ligurian Sea. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2019, 124, 3561–3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaitanya, A.V.S.; Vialard, J.; Lengaigne, M.; d’Ovidio, F.; Riotte, J.; Papa, F.; James, R.A. Redistribution of Riverine and Rainfall Freshwater by the Bay of Bengal Circulation. Ocean Dyn. 2021, 71, 1113–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaube, P.; Chelton, D.B.; Samelson, R.M.; Schlax, M.G.; O’Neill, L.W. Satellite Observations of Mesoscale Eddy-Induced Ekman Pumping. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2015, 45, 104–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, S.; Claret, M.; Pascual, A.; Olita, A.; Troupin, C.; Capet, A.; Tovar-Sánchez, A.; Allen, J.; Poulain, P.; Tintoré, J.; et al. Effects of Oceanic Mesoscale and Submesoscale Frontal Processes on the Vertical Transport of Phytoplankton. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2019, 124, 5999–6014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiatuhanga, D.P.A.; Morais, P.; Krug, L.A.; Teodósio, M.A. Reproduction Traits and Strategies of Two Sardinella Species off the Southwest Coast of Africa. Fishes 2025, 10, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).