4.1. Hydrodynamic Coefficients

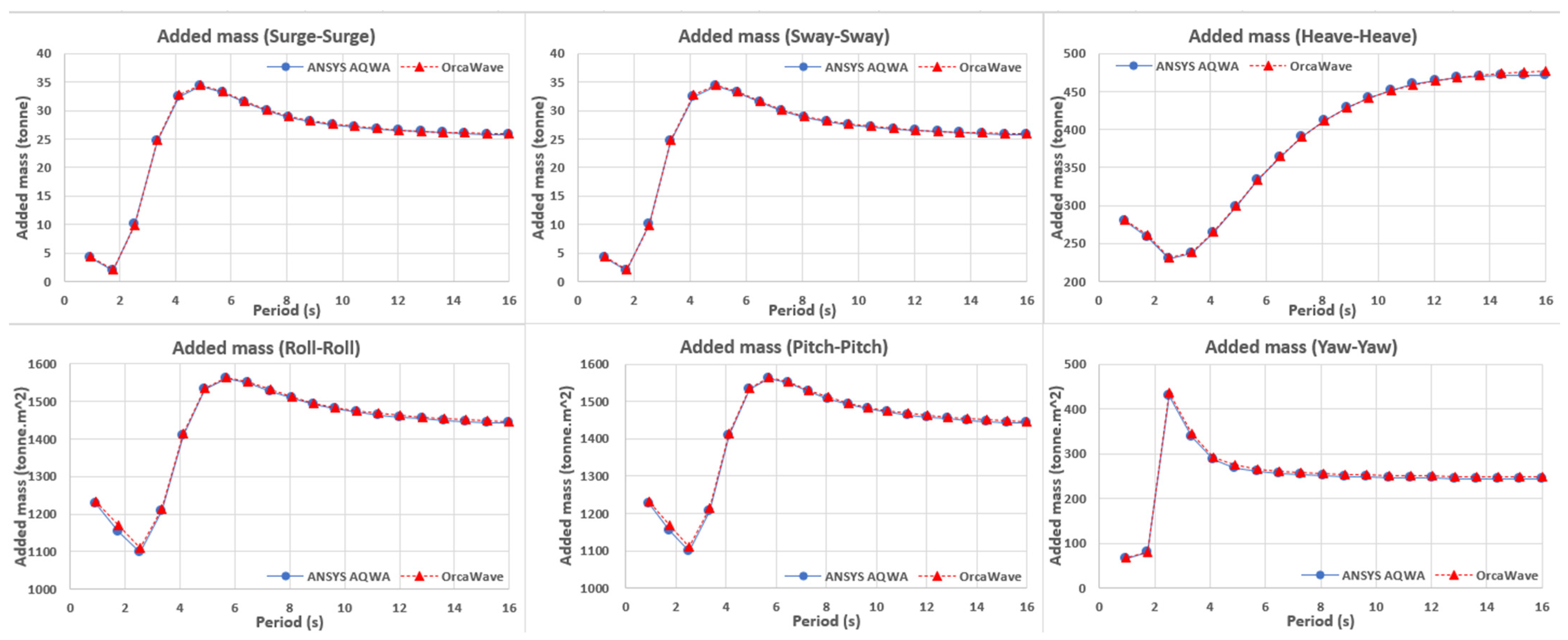

To compare the hydrodynamic coefficients, the structure designed by ANSYS AQWA was input directly into OrcaWave and analyzed. The analysis results are shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. The six-degree-of-freedom added mass/moment of inertia calculated under 0 deg incidence conditions were nearly identical in shape and magnitude across the entire periodic range between the two solvers (AQWA and OrcaWave). Surge and sway exhibited typical behavior, with equivalent short-period values, a gentle plateau around 4~5 (s), and then a very gradual decrease in the longer-period range. Heave increased monotonically with increasing period and tended to converge at the long-period limit. Roll and pitch peaked at

after a low point in the short-period range and then converged thereafter. Yaw exhibited a rapid decrease in damping after a rapid change in short-period values, and overall, no significant differences were observed in any case.

Continuously, radiation damping also showed high similarity across all cases, with the peak period, long-period limit, and curve shape consistently reproduced in both software, ensuring interoperability in this study. Therefore, the differences that appear in the subsequent comparison of regular and irregular waves in the time domain are unlikely to stem from the frequency-domain hydrodynamic coefficients within the tested range, and are more plausibly attributed to mooring nonlinearity and time-integration settings.

Quantitative comparisons of the hydrodynamic coefficients are summarized in

Appendix H, where the corresponding numerical indicators have been explicitly included for clarity. The relative deviations between AQWA and OrcaWave are very small across all degrees of freedom, with added-mass errors below 1.0%, radiation-damping errors below 0.5%, and displacement and load RAO deviations generally within 0.1–1.0%. These very small differences confirm that the two solvers produce numerically consistent frequency-domain hydrodynamic coefficients.

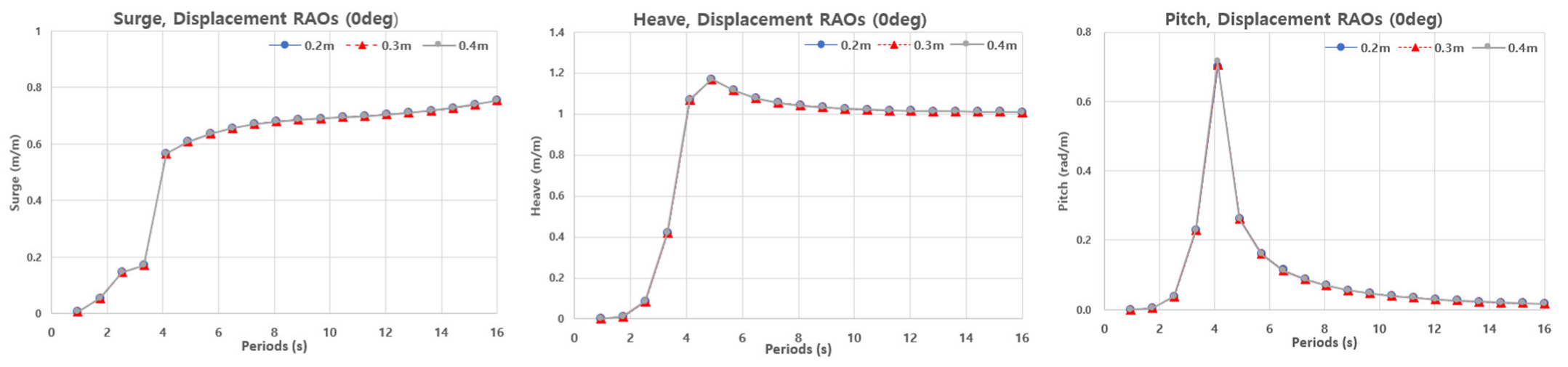

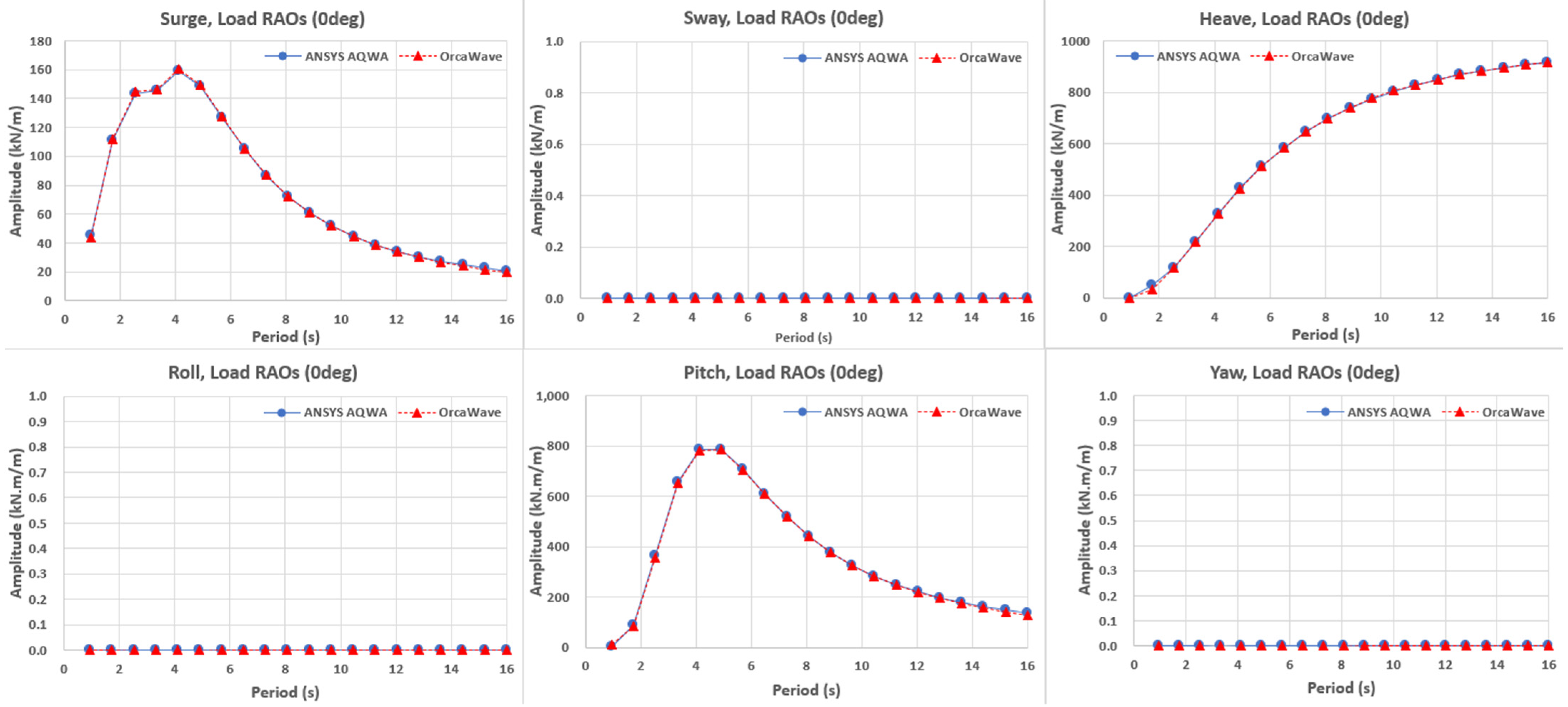

The corresponding RAO curves including displacements and loads under 0 deg heading are presented in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. Displacement RAOs calculated at 0 deg frontal incidence showed virtually identical results across the entire period between the two programs, which is expected given the identical conditions. Surge increased progressively in short periods, reaching a gentle plateau after

, while AQWA showed only a slight additional increase in long periods. Sway, roll, and yaw remained near zero due to the symmetry of frontal incidence. Heave peaked around

and then steadily converged, decreasing slightly over long periods. Pitch peaked around

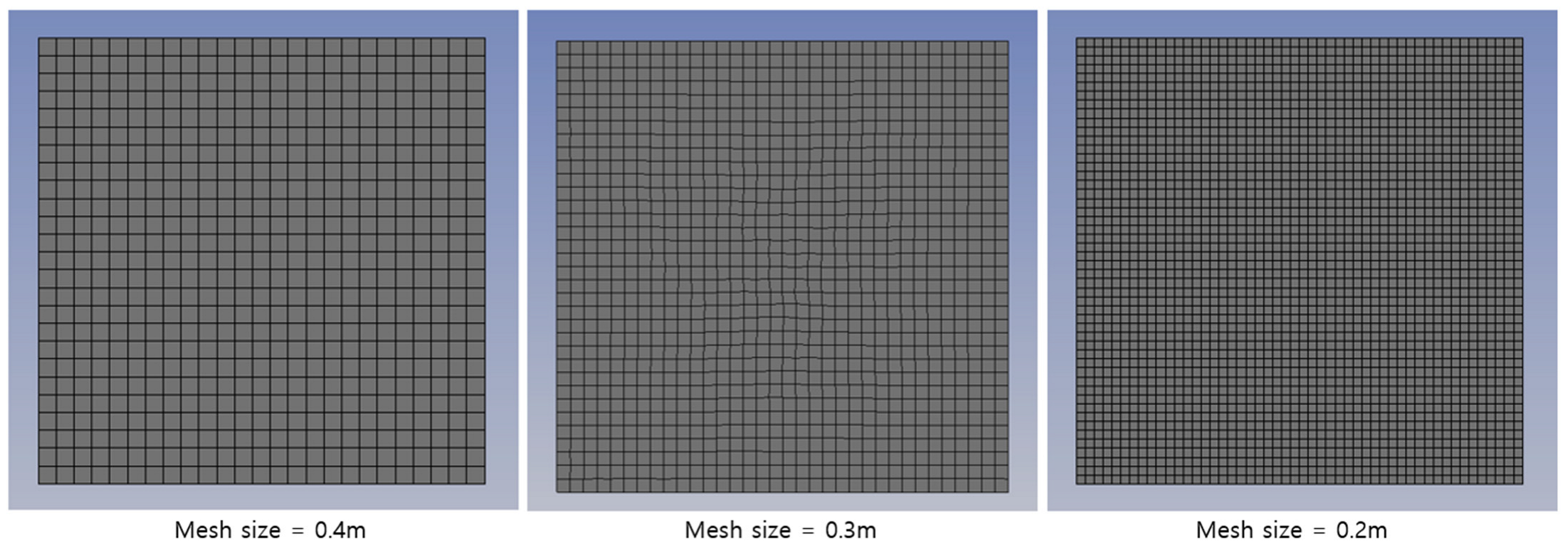

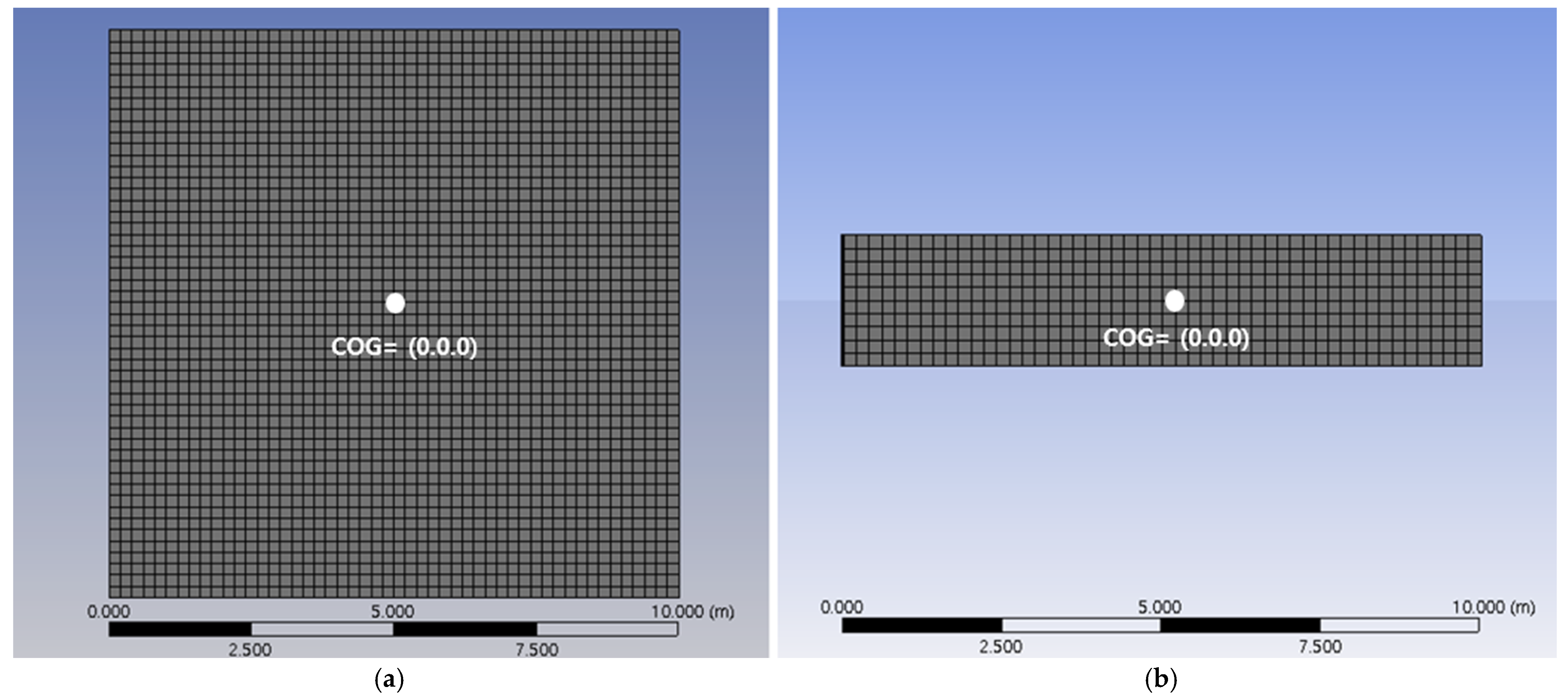

and then rapidly decreased. This trend indicates that only surge, heave, and pitch significantly reflect physical characteristics at frontal incidence. Consequently, the RAO results between the two software programs are nearly identical. Quantitatively, the deviation in RAO magnitude between AQWA and OrcaWave remained below 1% for all principal motion modes (surge, heave, and pitch) across the entire frequency range. These very small differences indicate that the frequency-domain hydrodynamic responses of both solvers are effectively identical under the unified modeling conditions. This demonstrates the compatibility of frequency-domain hydrodynamic coefficients computation, as wave normalization (half-amplitude), phase, COG (Center of Gravity), coordinate/sign, and heading definitions are identical. In addition to these definitions, further measures were taken to minimize numerical discrepancies arising from modeling choices. First, the hydrodynamic coefficients were evaluated at identical discrete wave frequencies in both AQWA and OrcaWave, ensuring that the added mass, radiation damping, and RAOs were compared without interpolation errors or sampling mismatches. Second, a mesh refinement study using panel sizes of 0.4 m, 0.3 m, and 0.2 m confirmed that the hydrodynamic results were mesh-independent, with RAO variations below 1%. These steps collectively minimized frequency sampling, mesh resolution, and postprocessing errors, enabling a fair and direct comparison of the hydrodynamic responses.

Before comparing the results between ANSYS AQWA and OrcaWave/OrcaFlex, the reliability of the present hydrodynamic model was examined using previously published experimental data. In the study [

27], the heave motion and excitation forces of a rectangular box were measured under regular and irregular waves and compared with linear potential-flow predictions. Their results showed that the heave RAO agreed well with linear theory across most frequencies, whereas noticeable deviations occurred near resonance due to additional viscous damping effects. Furthermore, the first-harmonic vertical excitation forces were reported to be approximately 10–15% lower than theoretical predictions, representing the typical level of discrepancy between experiments and potential-flow models. Since both ANSYS AQWA and OrcaWave employ the same linear potential-flow formulation, the small RAO differences observed in this study are consistent with this experimentally established accuracy range and reflect numerical differences rather than theoretical inconsistency.

4.2. Regular and Irregular Wave Effect

In this section, we aim to compare the dynamic behavior and mooring line tension for regular and irregular waves. All environmental heading conditions were set to 0 deg, the simulation time was 120 s, and the time step was set to 0.1 s, except for the 10 s transient response. Since the purpose was to compare the differences between the two programs, the simulation lengths were set to the same even in irregular wave conditions. To ensure the same wave settings for both programs, wave surface elevations were extracted from ANSYS AQWA at first and input into OrcaFlex again for both regular and irregular waves. This procedure was adopted because the default wave conventions of AQWA and OrcaFlex are not identical: AQWA defines wave height as crest-to-trough and uses a global phase origin, whereas OrcaFlex employs half-amplitude normalization and a COG-based phase reference [

22,

28]. Directly re-using the AQWA generated η(t) time history therefore ensures that both solvers are driven by an identical wave signal, eliminating inconsistencies in amplitude definition, phase, and heading. Through this process, absolute consistency in the environmental loading was achieved, which is essential for fair comparison of time-domain responses. All wind and current conditions were set identically for comparison for both programs. The JONSWAP spectrum properties were used to reflect the design of the substructure in the OrcaFlex example structure, and a peak enhancement factor of 3.3 was applied [

29,

30]. The JONSWAP spectrum with γ = 3.3 was adopted because it corresponds to the default irregular wave condition used in the OrcaFlex example model and represents a typical North Sea state commonly used for validation purposes. Since the objective of the irregular wave analysis is to provide a consistent input for comparing the numerical behavior of the two solvers, the results are primarily influenced by mooring line nonlinearity rather than small variations in the spectral peak enhancement factor. Thus, using γ = 3.3 does not materially affect the comparative conclusions of this study. All environmental conditions are summarized in

Table 2. The mooring lines were modeled as 145 m studlink R4 chains, and their mechanical and hydrodynamic properties are listed in

Table 3. Each line had an equivalent diameter of 0.05 m, an axial stiffness (EA) of

kN, a unit submerged mass of 54.75 kg/m, and was attached to a seabed anchor located at a 50 m water depth. The R4 studlink chain type was selected because it represents an industry-standard chain class widely used for barge-type and rectangular floating structures. Its mechanical stiffness, mass properties, and hydrodynamic drag characteristics provide a realistic and practically relevant baseline for catenary mooring behavior, ensuring that the comparison between the two solvers is conducted under representative offshore design conditions.

During both the static and dynamic analyses, the lines exhibited intermittent seabed contact. In OrcaFlex, seabed interaction is modeled using a linear elastic foundation, with only normal reaction forces applied when a segment touches the seabed (with friction set to zero). In contrast, ANSYS AQWA accounts for touchdown analytically through its quasi-static catenary formulation. A frictionless seabed was applied in both solvers to avoid introducing solver-dependent variability, ensuring that any differences observed originate solely from the hydrodynamic and mooring line dynamic formulations rather than from seabed-interaction effects. Furthermore, the static equilibrium configuration and pretension levels are summarized in

Appendix E. Identical material properties and boundary definitions were applied in both solvers to ensure consistent initial conditions for the subsequent dynamic simulation.

To compare the dynamic behaviors under regular and irregular waves, statistical analysis results were presented as mean, maximum, minimum, and standard deviation. To ensure fairness in comparison, the absolute difference

was reported first for the mean, maximum, minimum, and standard deviation. The absolute relative error for each was defined as

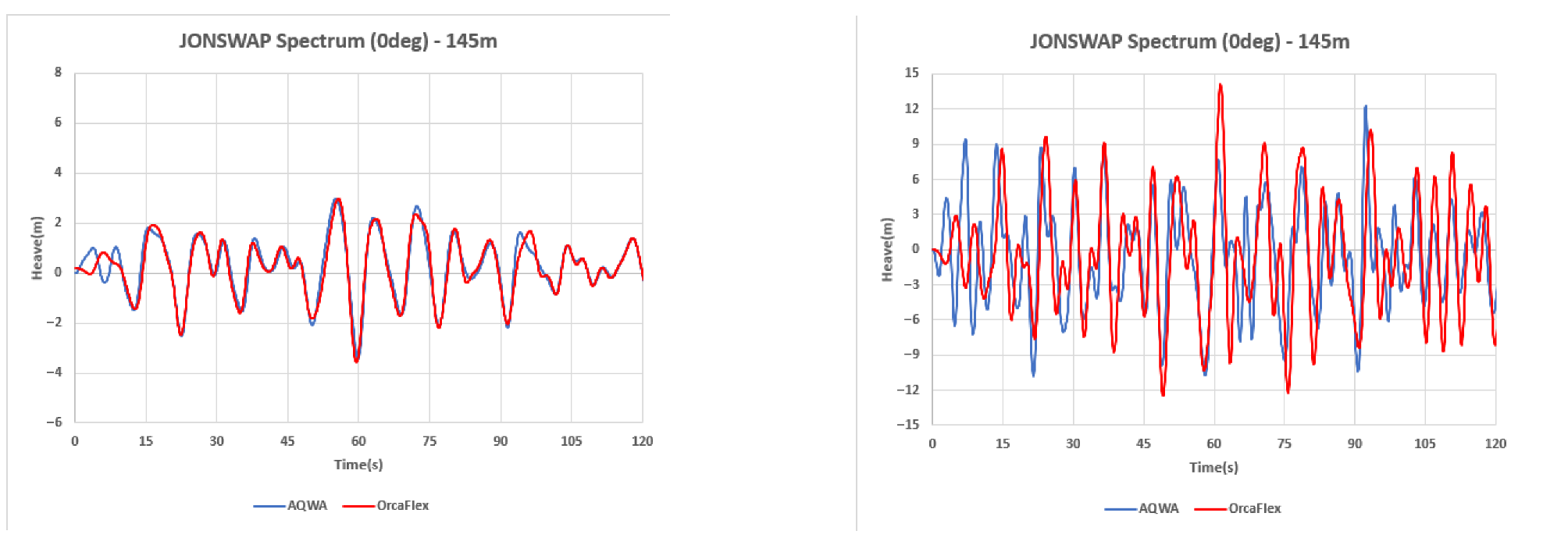

. Furthermore, the dynamic behavior of the floater was compared only for surge, which is most significantly affected by environmental conditions. As previously explained, the mooring line tensions were compared for Lines 1 and 2. Because the environmental heading is 0 deg, surge is the dominant degree of freedom excited by incident waves and horizontal-mooring-restoring forces. For completeness, the corresponding heave and pitch responses are presented in

Appendix C, where only minor differences were observed due to their hydrostatic-dominated behavior.

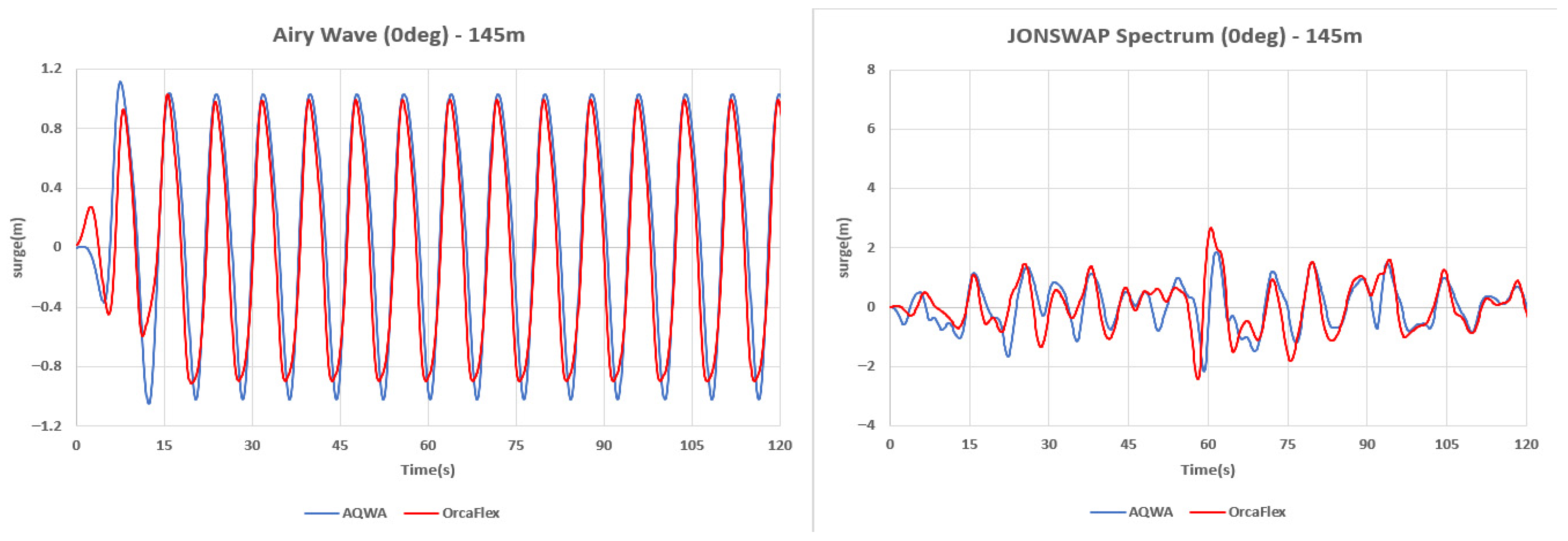

In the regular wave case, the two time series nearly overlapped as shown in

Figure 8. However, there was a slight error with respect to the mean value. In reality, the mean differed by approximately 0.12 m, indicating good agreement. The absolute errors of maximum, minimum, and standard deviation, which reflect the dynamic characteristics, were 7.6%, 13.2%, and 6.0%, respectively, showing good agreement. On the other hand, in irregular waves, although the overall trend was maintained, differences can be observed at some local peaks. The relative error of the mean was large, and the difference was amplified in the variance and peak point, showing a large difference in the absolute errors of maximum, minimum, and standard deviation, at 43.8%, 12.5%, and 11.5%, respectively. This is interpreted as being because, although the frequency-domain coefficients and RAO were almost identical, differences occurred in the time domain, such as mooring nonlinearity and differences in the integration process, causing the peak to be sensitively amplified. The corresponding numerical comparison results are presented in

Figure 8 and

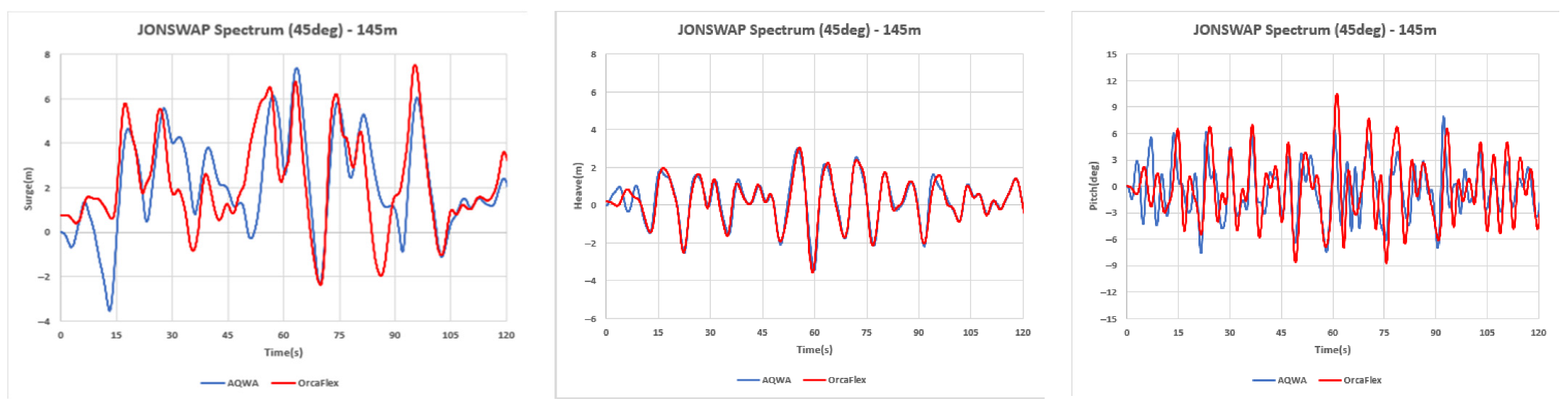

Table 4. To further assess the directional sensitivity of the platform motion, an additional case with 45 deg wave incidence was evaluated for the 145 m mooring configuration. Compared with the 0 deg condition, the heave response remains almost unchanged, whereas the low-frequency surge motion becomes slightly larger under oblique incidence. In contrast, the pitch response exhibits greater amplitudes under 0 deg frontal waves, where symmetric head sea loading generates a stronger overturning moment, while 45 deg incidence redistributes a portion of this excitation into sway, roll, and yaw. The full RAO and time series comparisons for the 45 deg heading are provided in

Appendix A and

Appendix B, and the reference 0 deg heave and pitch responses are shown in

Appendix C.

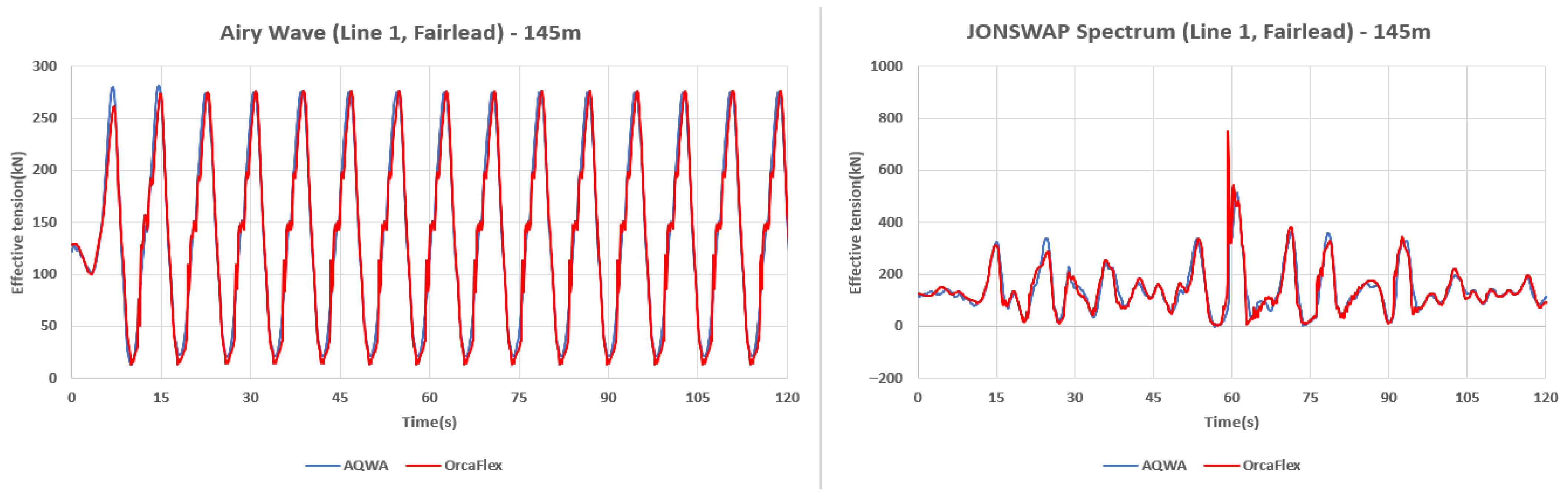

Continuously, in this section, mooring line tension at the fairlead point is compared for both regular and irregular waves. As previously explained, Line 1 is positioned in the direction of the environmental load (upwind), while Line 2 is positioned in the opposite direction (downwind).

Comparing the relative error (%) of Line 1, the average value remains largely unchanged at 2.5% for regular waves and 0.8% for irregular waves. However, the absolute errors of the maximum, minimum, and standard deviation are 1.7%, 3.6%, and 1.2%, respectively, for regular waves, and 45.8%, 41.3%, and 5.0% for irregular waves, showing a significant increase in error for irregular waves. As shown in

Figure 9, under irregular wave conditions, OrcaFlex exhibits a larger peak. This is interpreted as being due to OrcaFlex’s greater sensitivity to snap loading, which occurs when entering slack and then rapidly re-tensioning.

Line 2 also showed a similar relative error in average tension, at 3.0% for regular waves and 1.1% for irregular waves. However, the differences in maximum, minimum, and standard deviation were 3.3%, 4.4%, and 0.6% for regular waves, and 3.9%, 52.1%, and 7.0% for irregular waves, significantly increasing in irregular waves. This also stems from the difference in sensitivity to snap loading. The standard deviation of Line 2, in particular, is significantly larger than that of Line 1, as it is located on the opposite side (downwind) of the environmental load, making it more sensitive to slack generation. Quantitatively, the mean fairlead tensions from both solvers agreed within ≤3% for both Lines 1 and 2 under regular and irregular waves. Under irregular waves, the extremes diverged asymmetrically for Line 1—the maximum and minimum tensions differed by 45.8% and 41.3%, respectively; for Line 2 the maximum differed by only 3.9%, whereas the minimum differed by 52.1%. This pattern indicates that the windward line experiences much larger re-tension peaks, while the leeward line exhibits more pronounced slack-induced minima. The average loads remain nearly identical, but the extremes diverge due to differences in line dynamics and slack-to-taut re-tension modeling.

In summary, OrcaFlex models the line as a multi-degree-of-freedom lumped-mass system, directly integrating axial wave propagation, Morison nonlinear resistance, and the stick–slip and slack–taut transitions of seabed contact and friction in the time domain. This better preserves the high-frequency components and peaks of snap loading that occur during re-tension after slack, resulting in a relatively larger estimate compared to ANSYS AQWA under the same conditions [

31,

32]. These differences stem from the fundamentally different numerical formulations employed by the two solvers. OrcaFlex uses a multi-degree-of-freedom lumped-mass approach that explicitly integrates inertia, axial-wave propagation, and dynamic strain energy release in time, allowing the short-duration force spikes generated during slack–taut re-tension to be fully resolved. In contrast, ANSYS AQWA computes mooring loads using a quasi-static catenary equilibrium solution, which assumes instantaneous force balance and therefore filters out the transient elastic and inertial components responsible for peak amplification. Consequently, the two solvers show good agreement in mean tensions but diverge in short-duration extremes under irregular waves. These snap loading discrepancies can be mitigated by increasing the mooring pretension or avoiding excessively soft mooring configurations, which reduce slack–taut cycles. Additional damping or drag on the mooring lines can also limit the severity of transient peaks. Conversely, ANSYS AQWA may exhibit lower conservativeness due to partial mitigation of high-frequency peaks due to differences in the line model, numerical attenuation, and output smoothing. The corresponding comparison results are presented in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 and

Table 5 and

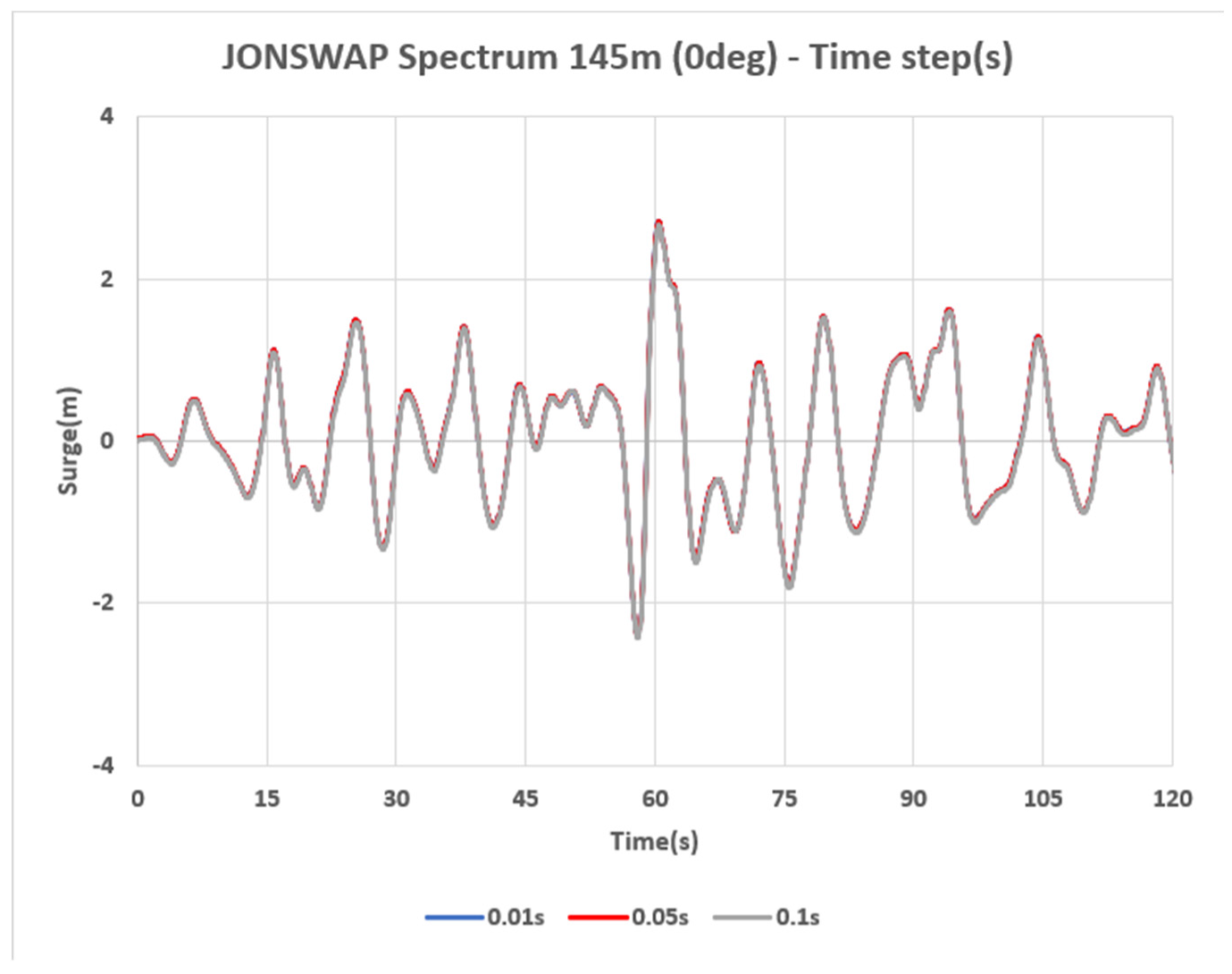

Table 6. To assess numerical stability, a time-step sensitivity study was conducted for the 145 m mooring line case, which represents the baseline configuration. Three different integration time steps, 0.1 s, 0.05 s, and 0.01 s, were tested under identical JONSWAP irregular wave conditions. As shown in

Appendix F, the resulting surge motions from all three time steps are nearly indistinguishable, and no noticeable differences were observed in the corresponding mooring line tensions. This confirms that the dynamic responses are fully converged with respect to time-step refinement, and that the default time step of 0.1 s provides numerically stable and accurate results. It should be emphasized that the present comparison is limited to operational regular and irregular wave conditions. Scenarios involving combined wave–wind–current loading or extreme storm seas were not included, as they introduce additional nonlinear interactions that may mask the isolated influence of the mooring line modeling approaches. These aspects will be explored in future work to assess whether solver-dependent differences become more pronounced under ultimate limit state conditions.

4.3. Mooring Line Length Effect

This section compares the effects of various mooring line lengths (145, 150, and 155 m) on the platform surge response (mean, maximum, minimum, and standard deviation) using ANSYS AQWA and OrcaFlex results. Only the mooring length was changed, while all other inputs remained constant as shown in

Figure 11. Only irregular wave conditions were considered. Mooring line length was selected as the primary variable because it directly governs the global restoring stiffness of the system and, more importantly, controls the occurrence of slack–taut transitions. These transitions are the dominant mechanism responsible for the differences observed between ANSYS AQWA and OrcaFlex, especially in peak tension responses. In contrast, other mooring parameters such as axial stiffness, line diameter, and anchor layout modify the system response more gradually within the operational range considered here and do not fundamentally alter the onset of re-tension or snap loading events. For this reason, these parameters were held constant to isolate the primary mechanism driving solver-to-solver discrepancies. A broader parametric study including stiffness, diameter, and anchor position will be pursued as part of our future work.

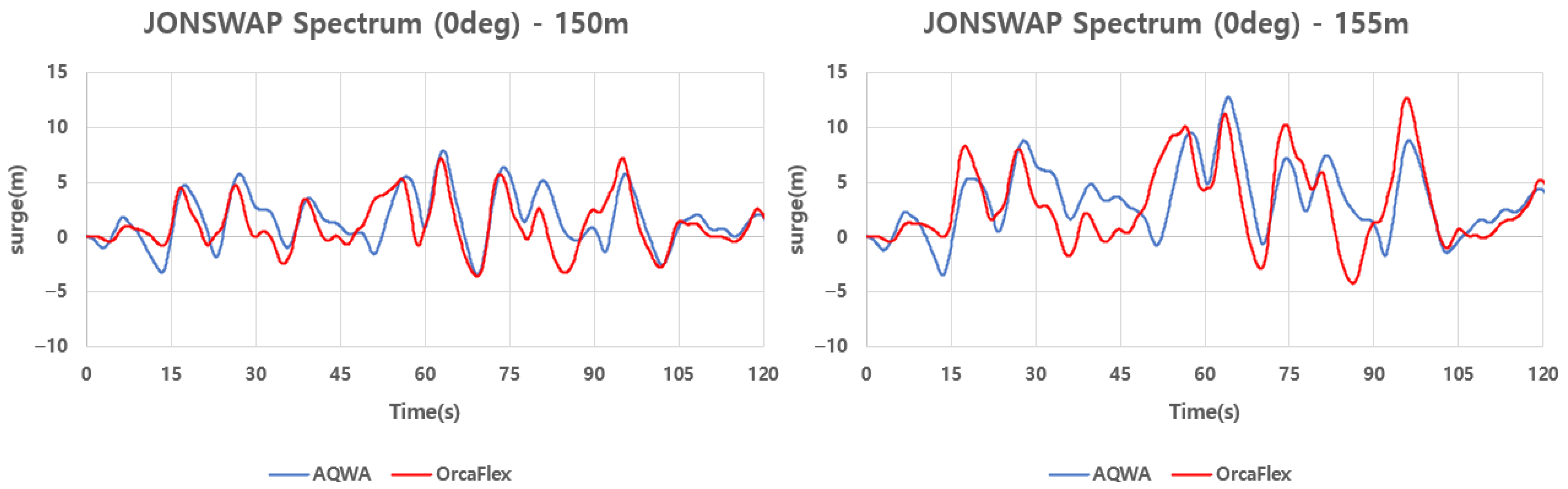

At 145 m, the mooring is relatively tight, resulting in small overall displacement. The mean absolute difference between the two codes is only 0.12 m, and the standard deviation difference is 0.04 m. The maximum value is 0.09 m, and the minimum value is 0.14 m, indicating virtually no difference.

Increasing the mooring line length to 150 m softens the restoring force, amplifying low-frequency components and reducing the minimum difference to 0.08 m. At this time, the maximum difference increases to 0.67 m, the standard deviation difference increases to 0.07 m, and the mean increases to 0.47 m. However, this difference is difficult to consider significant.

Even when the mooring line is extended to 155 m, the difference is not significant. The standard deviation difference is 0.49 m, the mean difference is 0.34 m, the maximum value is 0.06 m, and the minimum value is 0.76 m. In summary, even when the mooring line length is longer, all results show differences of less than 1 m, and it is judged that no significant difference was observed with respect to the surge motion. The corresponding comparison results are presented in

Figure 12 and

Table 7.

To clarify the physical origin of the solver-dependent differences, the absolute surge responses independent of solver mismatch were also examined. In AQWA, the standard deviation of surge increased from 0.744 m at a 145 m line length to 3.22 m at 155 m, representing a 2.48 m amplification. To support this interpretation, static analyses were performed to compute the pretension for each mooring line length, and the results are summarized in

Appendix E. The shorter lines exhibit higher pretension and consequently stronger stiffness, whereas longer lines develop lower pretension and allow larger surge excursions. This static behavior is fully consistent with the dynamic trend observed in the time-domain simulations.

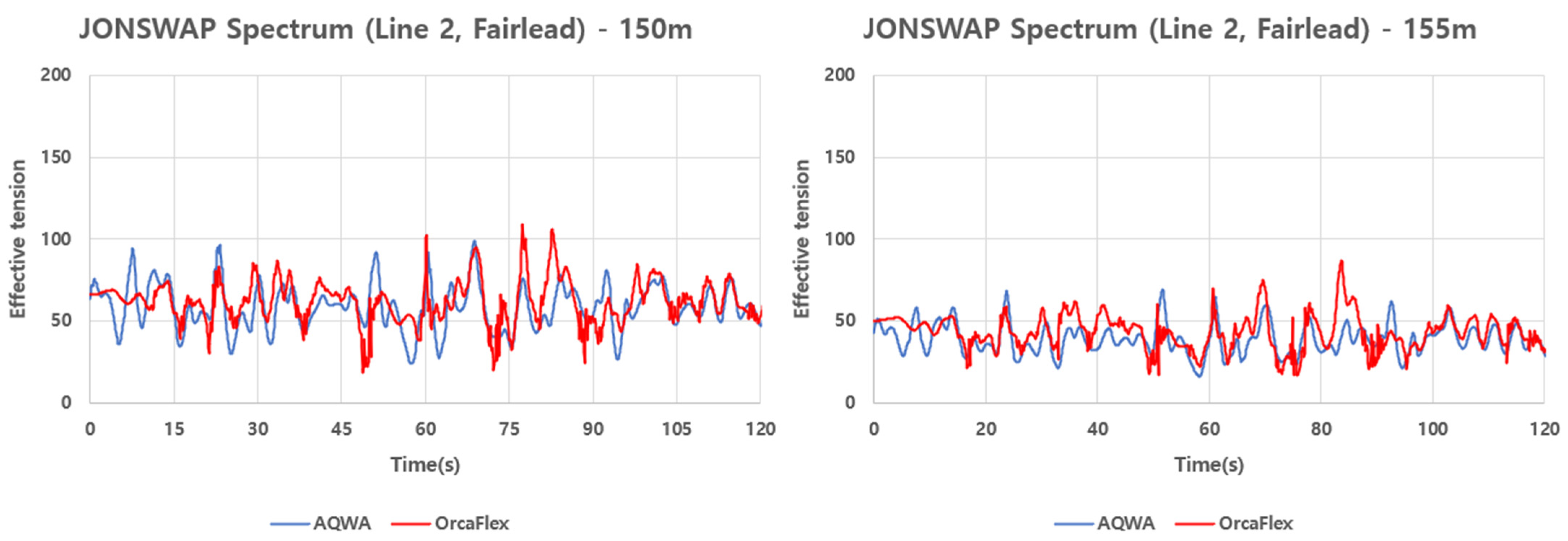

Furthermore, fairlead mooring tensions of Line 1 and 2 time series under JONSWAP conditions are shown in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14, while a numerical results comparison is tabulated in

Table 8 and

Table 9. The comparison was conducted using the previously defined indices (absolute difference, relative error). For Line 1 (windward), the average error was non-monotonic at 0.8%, 0.02%, and 9.8%, respectively, depending on the mooring line length (145, 150, and 155 m), while the standard deviation error increased to 5.0%, 7.4%, and 39.4%, respectively. In other words, the average error was smallest at 150 m and then increased significantly at 155 m. However, the decrease in average error was small when extending the length from 145 to 150 m, so the practical difference was considered limited. Line 2 (downwind) showed mean/standard deviation errors of 1.1/7.0% (145 m), 5.9/5.4% (150 m), and 11.2/15.3% (155 m), respectively. The mean error increased with increasing length, while the standard deviation error briefly decreased at 150 m before increasing significantly at 155 m. Therefore, the statement that both indices are at maximum at 155 m (catenary) is consistent with the numerical results. As the mooring line length increases, the effective horizontal restoring stiffness decreases, resulting in larger low-frequency surge excursions and an increase in standard deviation. At 155 m, the catenary becomes sufficiently soft that small variations in environmental loading generate larger fairlead displacements and more frequent slack–taut transitions. In OrcaFlex, these transitions are captured dynamically through inertia, axial elasticity, and transient snap loads, which amplify the variance and peak values. In contrast, AQWA’s quasi-static catenary formulation smooths out the transient elastic and inertial components, so the relative discrepancy becomes more pronounced at 155 m even though the absolute surge and tension differences remain small.

From a practical design perspective, the high snap load sensitivity predicted by OrcaFlex suggests the need for a dynamic mooring solver when relaxation–expansion transitions are expected. In contrast, the quasi-static formulation in ANSYS AQWA provides reliable estimates of global motions and mean- or fatigue-related loads but may underpredict short-duration snap events. Therefore, the selection of a solver should reflect the expected mooring line behavior: AQWA is suitable for global and fatigue assessments, whereas OrcaFlex is recommended when accurate snap load prediction is required.

Moreover, although the present study does not consider extreme sea states, the magnitude of the AQWA–OrcaFlex peak-tension deviation is consistent with previously reported differences between quasi-static and dynamic mooring formulations. Previous experimental work showed that quasi-static models significantly underpredict mooring loads, with extreme tensions underestimated by 10–25% and fatigue-related amplitudes by 65–75%, whereas dynamic lumped-mass models reproduce measured peak loads within approximately 10% [

25]. Similar trends were also identified in comparative analyses demonstrating that quasi-static prescreening approaches consistently underestimate maximum mooring tensions relative to fully coupled dynamic simulations under identical environmental conditions [

33].

Together, these findings explain why the quasi-static AQWA model produces substantially lower peak tensions than the fully dynamic OrcaFlex model in the present comparison. No dedicated basin or field measurements exist for the specific rectangular floater and mooring configuration considered here; therefore, a direct experimental validation of the numerical peak-tension differences is not possible. Nonetheless, the observed discrepancy aligns with the established behavior of catenary systems when quasi-static and dynamic mooring models are compared.

In addition, although the amplified low-frequency surge motion at 155 m could potentially affect fatigue accumulation or ultimate limit state (ULS) peak tensions in practical design, these consequences were not explicitly evaluated in this study. The present work focuses on quantifying the numerical differences between the solvers under operational irregular wave conditions rather than performing detailed fatigue or ULS assessments. A comprehensive investigation of these design implications is therefore recommended for future work. Overall, the results highlight that longer and more compliant mooring configurations lead to larger platform excursions, increased dynamic-tension variability, and a higher likelihood of slack–taut events. Such behavior directly affects station-keeping performance, fatigue life, and ULS safety margins. Therefore, mooring line length and pretension should be carefully selected to avoid excessive compliance that may reduce design robustness.