Abstract

This paper reports two newly discovered species of Tricoma (Tricoma)—T. (T.) discrepans sp. nov. and T. (T.) parasetosa sp. nov.—obtained from the subtidal sediments at a depth of 13 m around Jindo Island, Korea. Tricoma (T.) discrepans sp. nov. differs from its congeners in possessing 40–41 main rings, an uncovered first main ring, large vesicular amphidial fovea, and a distinctly thickened tail cuticle that is densely covered with secretions and adhering particles. Somatic setae in males exhibit pronounced sexual dimorphism, with the subventral setae more than twice as thick as the subdorsal setae, a morphological feature documented here for the first time within the subgenus Tricoma (Tricoma). Tricoma (T.) parasetosa sp. nov. can be recognized by 31 (rarely 32) main rings, two pairs of long, thick posterior somatic setae inserted on massive peduncles, a vesicular amphidial fovea extending to the second main ring, and a gubernaculum proximal end gently curved ventrally. Although the labial region is indistinct, the species bears two conspicuous lateral labial projections and a prominent cephalic concretion. Together, these results broaden the current understanding of Tricoma diversity in the northwestern Pacific and emphasize additional morphological variation within Desmoscolecida based on detailed Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) and Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) analyses.

1. Introduction

The order Desmoscolecida Filipjev, 1929 represents a comparatively small assemblage of free-living marine nematodes that inhabit a wide range of benthic habitats, from intertidal areas to deep-sea environments [1,2,3,4]. Most members of this order possess distinct body annulations, and their cuticle is covered with mineral particles embedded within a mucilaginous layer [5]. These structures are dynamically produced through undulatory body movements and represent morphological adaptations to sedimentary habitats [3,5].

Within this order, the subgenus Tricoma Cobb, 1894 is one of the most species-rich groups, with approximately 95 valid species currently recognized [6,7,8,9,10,11]. Species of Tricoma are characterized by smooth interzones between annuli, triangular or rounded desmen, the absence of abrupt inversion rings, and a generally triangular head [3]. Since its establishment by Cobb (1894), the genus has undergone several taxonomic revisions [1,6,12,13,14]. However, many early descriptions were based on single individuals or poorly preserved material, resulting in uncertainty regarding species boundaries and intraspecific variability [7,11]. Advances in light microscopy and scanning electron microscopy have greatly improved knowledge of Tricoma morphology [8,9,15], and numerous new species have been described from the Indian Ocean, the Andaman Islands, and the northwestern Pacific, highlighting the group’s high diversity and broad biogeographic range [8,10,11].

Taxonomic studies on Tricoma in Korea began with Lim and Chang (2005), who first described Tricoma (Quadricoma) jindoensis from the coastal sediments of Jindo Island [16]. Additional species have since been reported from the East Sea and from areas surrounding Ulleungdo Island [7,9]. Jindo Island, situated at the junction of the Yellow Sea and the South Sea of Korea, acts as a biogeographic transition zone shaped by contrasting hydrographic conditions. The region hosts high marine biodiversity and includes a variety of subtidal sedimentary habitats suitable for meiofaunal assemblages, particularly free-living nematodes [17,18]. Such environmental heterogeneity suggests that this area may be important for understanding morphological diversity within the group.

The present study describes two new species of Tricoma Cobb, 1894 from coastal sediments of Jindo Island, Korea. Using detailed observations from light and scanning electron microscopy, we document their morphological traits, provide diagnostic characters, and discuss their taxonomic relationships. The results expand current knowledge of Desmoscolecidae diversity and its biogeographic distribution in the northwestern Pacific.

2. Materials and Methods

Sediment intended for meiofaunal analysis was collected from a subtidal locality near Jindo Island at approximately 13 m depth. Sampling was conducted using a Van Veen grab deployed from a small research vessel. After each deployment, the uppermost 0–10 cm of the grab contents was gently subsampled with a hand shovel and placed in polyethylene bags for transport to shore. To extract meiofaunal organisms, the sediment was briefly exposed to freshwater in the field to induce osmotic stress, and the resulting mixture was passed through a 63 µm mesh. Material retained on the sieve was immediately fixed with buffered formaldehyde (final concentration 5%).

The fixed samples were processed in the laboratory using the Ludox HS40 density-gradient flotation procedure, which involved two sequential centrifugation steps [19]. The floating layer was poured through a 63 µm mesh and thoroughly rinsed with filtered water. Individual nematodes were picked under a Leica M205 C stereomicroscope and transferred to small droplets of 3% glycerol. Specimens were slowly dehydrated at room temperature for approximately ten days and subsequently mounted permanently in anhydrous glycerin using the paraffin wax-ring method [20].

Morphological examinations were performed using an Olympus BX53 compound microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with Differential Interference Contrast (DIC), and measurements were obtained with the accompanying cellSens Standard 1.16 software. High-resolution photomicrographs were captured with a Leica DM2500 LED microscope fitted with a K5C CMOS camera (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany), and minor image adjustments were made in Adobe Photoshop 2023. Line drawings were prepared using a camera lucida attached to the DM2500 LED microscope and digitally refined in Adobe Illustrator 2023.

For Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), specimens originally preserved in 5% buffered formalin were rinsed three times in distilled water for 10 min each to remove residual fixative. The specimens were then transferred to a small amount of distilled water in a glass vial and freeze-dried using an EYELA FDU-1200 freeze dryer (EYELA, Tokyo, Japan). Freeze-dried individuals were mounted on aluminum stubs with carbon tape using a fine dissecting needle, sputter-coated with gold–palladium using a CT-1000 ion sputter coater, and examined with an IM 300S SEM (ETS Co., Ltd., Hwaseong, Republic of Korea) at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV.

3. Results

3.1. Tricoma (Tricoma) discrepans sp. nov. (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5, Table 1)

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:2178930E-8875-4E38-8045-D8E6C883ECE1

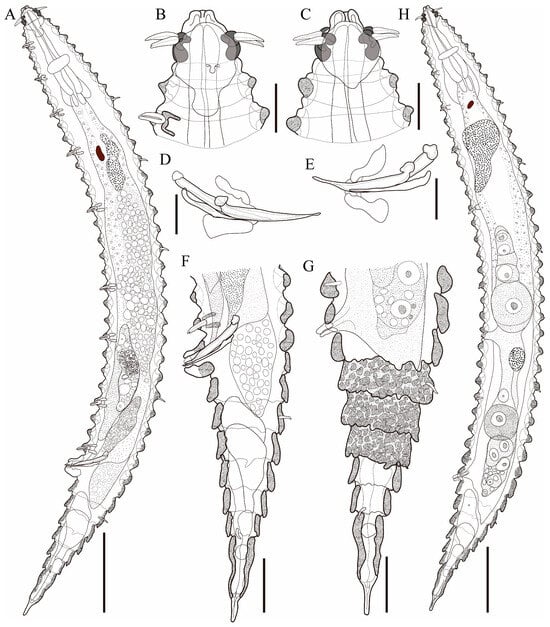

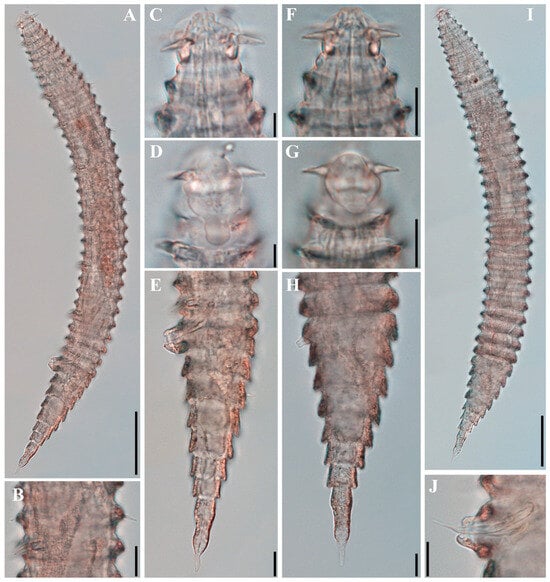

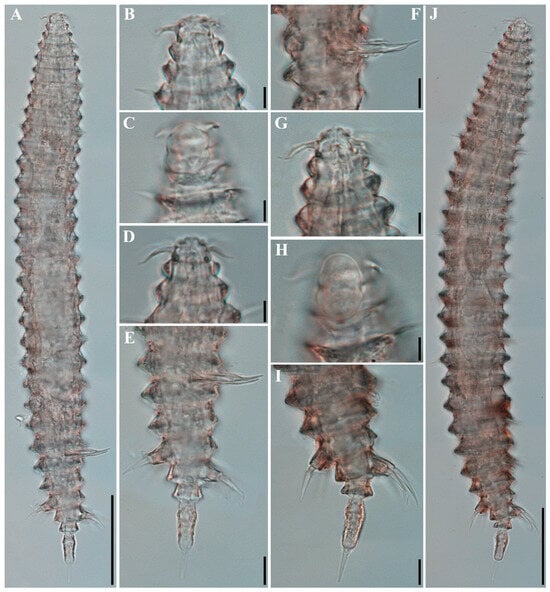

Figure 1.

Tricoma (Tricoma) discrepans sp. nov. (A) entire body, holotype male; (B) lateral view of anterior region, holotype male; (C) lateral view of anterior region, paratype female (KIOST NEM-1-2864); (D) spicules and gubernaculum, paratype male (KIOST NEM-1-2853); (E) spicules and gubernaculum, paratype male (KIOST NEM-1-2855); (F) lateral view of posterior region, holotype male; (G) lateral view of posterior region, paratype female (KIOST NEM-1-2864); (H) entire body, paratype female (KIOST NEM-1-2864). Scale bars: (A,H) = 50 µm; (B–E) =10 µm; (F,G) = 20 µm.

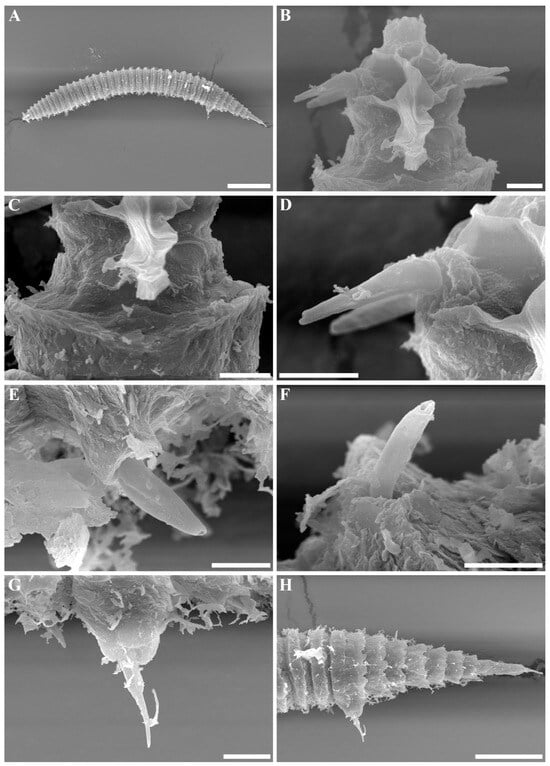

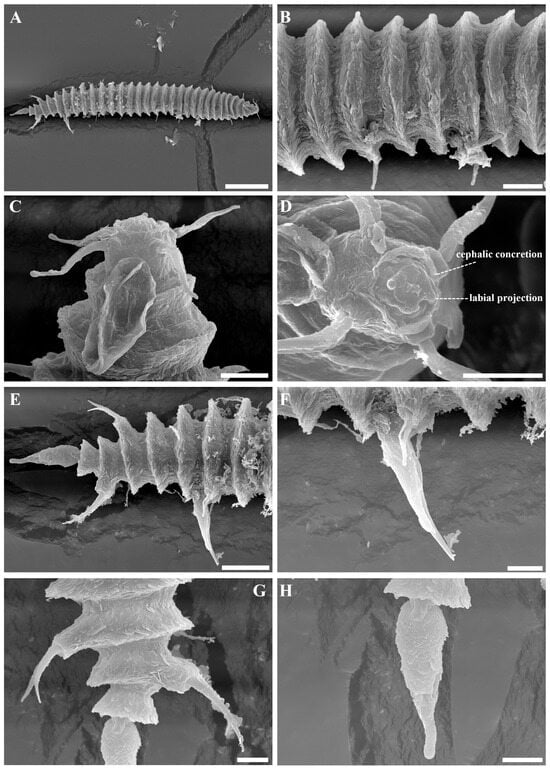

Figure 2.

Tricoma (Tricoma) discrepans sp. nov. SEM micrographs, male 1. (A) Entire body; (B) head region showing amphideal fovea; (C) uncovered first main ring; (D) distal structure of cephalic setae with stepped tip; (E) subventral setae inserted on a relatively high peduncle; (F) subdorsal setae inserted on a lower peduncle; (G) pointed spicule region protruding beyond the cloacal opening; (H) thickened tail cuticle obscuring secondary annulation. Scale bars: (A) =100 µm; (B–F) = 5 µm; (G) = 10 µm; (H) = 50 µm.

Figure 3.

Tricoma (Tricoma) discrepans sp. nov. SEM micrographs, males. (A) entire body (Male 2); (B) midbody showing contrast in somatic seta thickness (Male 2); (C) head region with amphidial fovea (Male 2); (D) very thickly developed tail cuticle (Male 2); (E) everted labial region in lateral view with visible labial sensillum (Male 1); (F) en face view of labial region with oral opening, showing a concentric double circle structure (Male 3); (G) lateral view of the head showing a contracted labial region (Male 4); (H) oblique en face view of labial region with oral aperture closed, showing three concentric circle structure (Male 4). Scale bars: (A) = 100 µm; (B,D) = 50 µm; (C,G) = 10 µm; (E) = 5 µm; (F,H) = 3 µm.

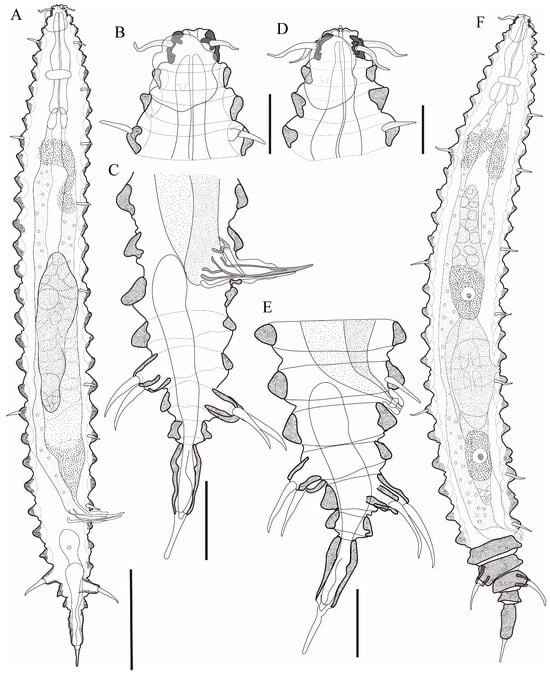

Figure 4.

Tricoma (Tricoma) discrepans sp. nov. SEM micrographs, female. (A) entire body; (B) subdorsal and subventral setae on the midbody cuticle showing no difference in thickness; (C) head region; (D) oblique en face view of labial region with oral aperture closed, showing three concentric circle structure; (E) subventral setae; (F) subdorsal setae; (G) very thickly developed tail cuticle covering the secondary annulation; (H) terminal ring region. Scale bars: (A) = 100 µm; (B,G) = 50 µm; (C,H) = 10 µm; (D–F) = 5 µm.

Figure 5.

Tricoma (Tricoma) discrepans sp. nov. DIC photomicrographs. (A) entire body, holotype male; (B) difference between subdorsal and subventral setae, holotype male; (C) head region showing the uncovered first main ring, holotype male; (D) amphideal fovea elongated ventrally in a cylindrical shape, holotype male; (E) posterior body region showing spicules and gubernaculum, holotype male; (F) head region, paratype female (KIOST NEM-1-2864); (G) slightly elongated amphideal fovea, paratype female (KIOST NEM-1-2864); (H) posterior region with strongly developed cuticle appearing rectangular profile in lateral view, paratype female (KIOST NEM-1-2864); (I) entire body, paratype female (KIOST NEM-1-2864); (J) spicule and gubernaculum after lactic acid treatment dissolving surrounding materials (KIOST NEM-1-2855). Scale bars: (A,I) = 50 µm; (B,E–H,J) = 10 µm; (C,D) = 5 µm.

Table 1.

Morphometric measurements of Tricoma (Tricoma) discrepans sp. nov. (µm).

Table 1.

Morphometric measurements of Tricoma (Tricoma) discrepans sp. nov. (µm).

| Males | Females | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Holotype | Paratypes (n = 11) | Paratypes (n = 6) | |

| Body length | 462 | 429.6 ± 23.4 (396–466) | 497.1 ± 23.6 (466–532) |

| Body ring count | 40 | 40.3 ± 0.4 (40–41) | 40.2 ± 0.4 (40–41) |

| a | 11.4 | 9.3 ± 1.0 (9.2–11.1) | 10.2 ± 0.5 (9.5–10.9) |

| b | 7.7 | 7.2 ± 0.4 (6.6–8.0) | 8.2 ± 0.7 (7.3–9.1) |

| c | 5.0 | 4.6 ± 0.1 (4.2–4.8) | 4.7 ± 0.1 (4.5–4.9) |

| C′ | 2.4 | 2.4 ± 0.1 (2.2–2.5) | 2.4 ± 0.1 (2.2–2.6) |

| Head diameter at cephalic setae level | 13 | 12.5 ± 0.7 (12–14) | 12.5 ± 0.5 (12–13) |

| Head length | 11 | 10.6 ± 1.0 (9–12) | 11.1 ± 0.7 (10–12) |

| Body diameterat the level of cardia | 35 | 37.6 ± 1.6 (35–40) | 39.5 ± 1.0 (38–41) |

| Maximum body diameter | 41 | 46.7 ± 5.5 (41–61) | 48.5 ± 1.0 (47–50) |

| Cephalic setae length | 6 | 6.6 ± 0.5 (6–7) | 7.1 ± 0.5 (6–8) |

| Amphidial fovea length | 19 | 16.3 ± 2.3 (13–20) | 13.4 ± 0.7 (12–14) |

| Ocelli diameter | 3 | 4.4 ± 1.1 (3–6) | 4.5 ± 1.1 (3–6) |

| Ocelli length | 9 | 6.6 ± 3.7 (3–15) | 3.8 ± 0.7 (3–5) |

| Distance from anterior end to ocelli | 101 | 102.9 ± 10.8 (82–127) | 81.6 ± 4.4 (77–90) |

| Pharynx length | 60 | 59.8 ± 3.1 (56–68) | 61.3 ± 4.1 (57–69) |

| Subventral setae count (right side) | 10 | 9.9 ± 0.3 (9–10) | 8.7 ± 0.5 (8–9) |

| Subventral setae count (left side) | 10 | 9.9 ± 0.3 (9–10) | 8.5 ± 0.5 (8–9) |

| Maximum subventral setae length | 7 | 9.3 ± 0.8 (8–11) | 6.9 ± 0.5 (6–8) |

| Minimum subventral setae length | 4 | 4.0 ± 0.6 (3–5) | 4.3 ± 0.2 (4–5) |

| Subdorsal setae count (right side) | 5 | 3.9 ± 0.5 (3–5) | 3.7 ± 0.5 (3–4) |

| Subdorsal setae count (left side) | 4 | 5.1 ± 0.3 (5–6) | 5.0 ± 0.0 (5–5) |

| Maximum subdorsal setae length | 5 | 5.7 ± 0.5 (5–6) | 6.2 ± 0.5 (6–7) |

| Minimum subdorsal setae length | 4 | 3.9 ± 0.5 (3–5) | 4.4 ± 0.5 (3–5) |

| Spicule length | 27 | 26.0 ± 1.1 (24–28) | – |

| Gubernaculum length | 22 | 22.7 ± 1.5 (21–27) | – |

| Distance from anterior end to vulva | – | – | 270.2 ± 15.5 (246–288) |

| Body diameter at vulval level | – | – | 42.6 ± 1.2 (41–44) |

| Vulval position (V%) | – | – | 54.3 ± 1.2 (53–56) |

| Anal body diameter | 40 | 39.8 ± 2.0 (36–43) | 43.6 ± 1.7 (40–45) |

| Tail length | 93 | 93.5 ± 5.9 (85–104) | 106.8 ± 6.2 (100–115) |

| Tail ring count | 7 | 7.3 ± 0.4 (7–8) | 7.2 ± 0.4 (7–8) |

| Terminal ring length | 32 | 30.3 ± 2.3 (27–36) | 33.7 ± 2.0 (31–36) |

| Terminal ring width | 9 | 8.0 ± 0.6 (8–9) | 10.0 ± 0.8 (8–11) |

| Spinneret length | 8 | 8.3 ± 0.8 (7–10) | 8.2 ± 0.7 (7–8) |

3.1.1. Systematics

Class Chromadorea Inglis, 1983

Order Desmoscolecida Filipjev, 1929

Superfamily Desmoscolecoidea Shipley, 1896

Family Desmoscolecidae Shipley, 1896

Subfamily Tricominae Lorenzen, 1969

Genus Tricoma Cobb, 1894

Subgenus Tricoma Cobb, 1894

3.1.2. Material Examined

The holotype male (MABIK NA00158850), mounted on an HS glycerin slide, is deposited in the Marine Biodiversity Institute of Korea (MABIK), Seocheon. The remaining type material consists of eleven male paratypes (KIOST NEM-1-2851–2861) and six female paratypes (KIOST NEM-1-2862–2867), all of which are curated in the Bio-Resources Bank of Marine Nematodes (BRBMN) at the East Sea Research Institute, KIOST.

3.1.3. Type Locality and Habitat

All type material was obtained on 20 May 2025 from a subtidal muddy habitat at Site 1 near Jindo Island, Korea (34°21′9.22″ N, 126°14′47.78″ E), using a Van Veen grab at a depth of 13 m. The sediment was dominated by fine mud with moderate organic content, accompanied by scattered shell debris. During sampling, bottom-water temperature ranged from 14.4 to 14.6 °C, and salinity varied between 33.3 and 33.4‰.

3.1.4. Etymology

The epithet discrepans is derived from Latin “differing,” referring to the marked variation in the thickness of the subdorsal and subventral somatic setae.

3.1.5. Measurements

Morphometric data for the examined specimens are summarized in Table 1.

3.1.6. Diagnosis

Tricoma (Tricoma) discrepans sp. nov. is set apart from other species of the subgenus by distinctive morphological characters: (1) a small, slender body, with 40–41 main rings; (2) a first main ring lacking desmos; (3) a triangular head with truncate anterior margin; (4) labial region with six distinct lips, each bearing a centrally positioned labial sensillum surrounded by a circular labial ridge; (5) large vesicular amphidial fovea extending to the first or second main ring; (6) a somatic setae pattern of 3–6 subdorsal and 9–10 subventral setae on each side; (7) marked sexual dimorphism in somatic setae—males exhibit subventral setae nearly twice as thick and more strongly developed than subdorsal setae, inserted on relatively high peduncles, whereas females possess subventral and subdorsal setae of nearly equal length and thickness; (8) slightly arched spicules with a small capitulum and gubernaculum slightly widened at approximal third, with a sclerotized anteriorly directed apophysis; and (9) a tail with 7–8 main rings, whose markedly thickened posterior margins extend over the anterior margins of the following rings, obscuring the secondary annulations and giving the tail a nearly rectangular profile.

3.1.7. Description

Males: The body is slender, with the holotype bearing 40 main rings and the paratypes bearing 40–41 rings, the dorsal and ventral counts being identical (Figure 1A, Figure 2A, Figure 3A and Figure 5A). Each ring is marked by subtle secondary annulations and a coating of secretions and adhering particles (Figure 3B), which become progressively denser toward the tail (Figure 2H and Figure 3D). The first main ring lacks desmos and forms a conspicuous gap from the head region (Figure 2C and Figure 5C). In several paratypes, the uncovered first ring takes on a more constricted appearance (Figure 4C). Quadricomoid ring patterns are expressed anteriorly and posteriorly, while the midbody displays tricomoid ring configurations (Figure 2A, Figure 3A and Figure 5A).

In the lateral view, the head is triangular with a truncated anterior margin, tapering from the base of the cephalic setae (Figure 1B, Figure 2B and Figure 5C). Based on SEM observations, the labial region is distinctly differentiated and structurally organized into concentric elements. When the lips are everted and the oral aperture is open, the labial region forms a concentric double-circle structure in en face view (Figure 3F). The inner circle is composed of an oral ridge surrounding the oral aperture, whereas the outer circle consists of six distinct lips. Each lip bears a centrally positioned labial sensillum encircled by a circular labial ridge (Figure 3F). In lateral view under this condition, the oral region protrudes from the cephalic region, showing a rounded, tube-like profile (Figure 2B and Figure 3E).

When the lips contract and the oral aperture is closed, in en face view the labial region is organized into three concentric circles (Figure 3H). The innermost circle is oral ridge, which closes the oral aperture. The second circle corresponds to the labial sensilla, each of which retracts inward within its respective labial ridge (Figure 3H). The outermost circle is represented by a distinct cephalic concretion ridge, which is formed as the entire labial region becomes depressed into the cephalic region under this condition. In lateral view, the oral region retracts completely, rendering the cephalic region flattened (Figure 3C,G). A heavily sclerotized cephalic rim surrounds the head, excluding the labial region (Figure 1B and Figure 5C). Cephalic setae are approximately half the head width in length and are inserted on short peduncles located posterior to the head margin. The setae taper distally to a perforated tip and are entirely enveloped by a thin membrane. SEM observations further reveal that the distal ends of the cephalic setae are stepped (Figure 2D and Figure 3C).

The amphidial fovea are large, vesicular structures occupying lateral surfaces of the head (Figure 1B, Figure 3C and Figure 5D). In the holotype, they form elongated, cylindrical vesicles at the base, whereas in some paratypes, the vesicular region is less extended. They extend anteriorly to the labial region and posteriorly to the second, or occasionally the first main ring (Figure 2B).

The stoma is cylindrical and minute, measuring 2–3 µm in length. The pharynx is also cylindrical, comprising 13–15% of total body length and slightly expanding posteriorly (Figure 1A). The pharyngo-intestinal junction lies near main ring 8 (7–9 in paratypes). The nerve ring encircles the pharynx around main rings 5–6 in the holotype (4–6 in paratypes). The cardia is small, occasionally projecting into the intestinal lumen (Figure 1A). Ocelli are reddish-brown, 3–6 µm wide and 3–15 µm long, and are situated opposite rings 12–13 (10–14 in paratypes). The intestine begins as a narrow tube with fine granules and widens posteriorly, containing spherical inclusions.

Somatic setae occur in two subdorsal and two subventral longitudinal rows. Subdorsal setae are slender (1.0–1.4 µm thick) and inserted directly into the cuticle or onto low peduncles, whereas subventral setae are more robust (2.2–2.8 µm thick) and borne on comparatively higher peduncles (Figure 3B and Figure 5B). The terminal subventral seta at ring 39 is slightly lateral, shorter, and thinner, resembling subdorsal setae (Figure 1F and Figure 3D). The longest subventral seta, situated just anterior to the cloacal opening, measures 8–11 µm; others range from 3 to 7 µm. Subdorsal setae measure 3–6 µm and show little variation. Under light microscopy, setae appear bifid distally (Figure 5B), whereas SEM imaging reveals curved tips (Figure 2E,F). On each side, 3–6 subdorsal and 9–10 subventral setae are present, though some are broken or absent.

For the holotype male, the somatic setae pattern is summarized below:

| subdorsal | left side: | 10,14,19,25,35 | =5 |

| right side: | 9,14,21,32 | =4 | |

| subventral | left side: | 3,6,9,12,16,21,24,28,31,39 | =10 |

| right side: | 3,6,9,12,16,20,24,28,31,39 | =10 |

For the paratype males, the somatic setae pattern is likewise summarized below, with bracketed numbers indicating positional variation:

| subdorsal | left side: | 10,14(15),19(20),(23),28(27),35(34) | =5(6) |

| right side: | 8(7,9),14(15,16),21,28,35(33,34) | =5(3,4) | |

| subventral | left side: | 3,6(5),9,12(13),16(17),21(20,22),24(25,26),28,31,39(38) | =10(9) |

| right side: | 3,6,9,12(11),16(17),21(20,22),24(25),28,31(30),39 | =10 |

The reproductive system is diorchic with two testes. The spicules are slightly arched, and taper distally to a pointed tip, bearing a small proximal capitulum (Figure 1F and Figure 2G). The slender gubernaculum runs nearly parallel to the spicules, slightly widened at its proximal third, bearing a sclerotized, anteriorly directed apophysis (Figure 1D,E and Figure 5J). The cloacal tube is large and well developed, measuring 5–8 µm in length (Figure 2G).

The tail consists of 7–8 main rings whose posterior margin are markedly thickened and extend anteriorly over the following ring, thereby obscuring the secondary annulations (Figure 1F, Figure 2H, Figure 3D and Figure 5E). In lateral view, the strongly developed posterior margins create nearly perpendicular and borders and give the tail a rectangular profile (Figure 1F and Figure 5E). The tail cuticle is markedly thickened and densely covered with secretions and coarse adhering particles, contrasting sharply with the rest of the body. The terminal ring is conical to cylindrical, with slightly thickened cuticle except at the spinneret (Figure 2H and Figure 3D). Phasmata (2.1–3.5 µm) lie 3–7 µm beneath the terminal ring and are often indistinct.

Females: Females resemble males in general habitus, body annulation, head morphology, and tail structure, including the nearly rectangular cuticle of the tail region (Figure 1C,G,H, Figure 4A–H and Figure 5F–I). The cuticle is composed of 40 main rings in most individuals and 41 in one paratype, each covered with fine secretions and particles. Amphids are large, vesicular, and extend from the labial region to the first or second ring (Figure 1C and Figure 5G). Ocelli are small, dark reddish-brown, 3–6 µm wide and 3–5 µm long, and positioned between rings 8–10. Somatic setae are arranged in two subdorsal and two subventral rows, consisting of 3–5 subdorsal and 8–9 subventral setae, respectively. Both somatic setae are nearly identical in thickness (1–2 µm) and similar in length, with subdorsal setae measuring 3–7 µm and subventral setae 4–8 µm (Figure 4B). The setae are slender and taper distally to fine tips, inserted either directly into the cuticle or on low peduncles (Figure 4E,F).

For the paratype females, the somatic setae pattern is likewise summarized below, with bracketed numbers indicating alternative positions:

| subdorsal | left side: | 10,14(13,15,17),19(20),27,35(33,34) | =5 |

| right side: | 8,14,21,34(33,35,36) | =4(3) | |

| subventral | left side: | 6(7),9(10),12(11,13),16(17),21(20),24,28(27),32(31),39 | =9(8) |

| right side: | 6(5),9(10),12(11),16(15),21(19,20),24(25),28(27,29),32(31),39 | =9(8) |

The reproductive system is didelphic with opposing branches. The vulva lies between rings 23–24 (or 24–25 in some paratypes) (Figure 1H). The anal tube (4–6 µm) projects from the ventral wall near ring 33 (Figure 5H). The tail consists of seven main rings in most females, whereas the specimen bearing 41 body rings possesses eight. These rings are closely arranged, giving the tail a nearly rectangular appearance similar to that of the male (Figure 4G). The terminal ring is conical to cylindrical with an elongated spinneret (7–9 µm) (Figure 4H). Phasmata (2–4 µm) lie within the terminal-ring desmos and may be indistinct (Figure 1G).

3.1.8. Differential Diagnosis and Relationship

Tricoma (Tricoma) discrepans sp. nov. characterized by 40–41 main rings, belongs to the group of species possessing 30–49 main rings according to the comparative framework proposed by Decraemer (1978) for the subgenus Tricoma (Tricoma) [6]. In this context, the present study provides a comparative table (Table 2) highlighting key diagnostic characters derived from original species descriptions, thereby clarifying species limits and morphological affinities within this subset of the subgenus.

Table 2.

Comparative summary of diagnostic morphological traits for species of the subgenus Tricoma possessing 30–49 main rings. Morphometric values are rounded; unavailable entries are marked with an en dash (–). Species possessing an uncovered first main ring are indicated by an asterisk (*).

Within this group, six species—T. (T.) apophysis Soetaert and Decraemer, 1989; T. (T.) breviseta Lee et al., 2023; T. (T.) corsicana Soetaert and Decraemer, 1989; T. (T.) donghaensis Lee et al., 2023; T. (T.) duopapillata Soetaert and Decraemer, 1989; and T. (T.) latispicula Soetaert and Decraemer, 1989—possess an uncovered first main ring [7,21]. Among these, T. (T.) apophysis most closely resembles T. (T.) discrepans sp. nov. in overall morphology, including main ring counts, the pattern of somatic setae, the structure of the male copulatory apparatus, and the counts of tail rings. Despite these similarities, the two species differ decisively in several characters. First, T. (T.) discrepans sp. nov. is substantially larger (males 396–466 µm, females 466–532 µm) than T. (T.) apophysis (males 185–245 µm, females 180–260 µm). Second, the head of the new species is triangular in lateral view, whereas T. (T.) apophysis possesses a head with nearly parallel sides and a broadly truncated anterior margin. Additionally, T. (T.) discrepans sp. nov. exhibits a unique tail morphology: the tail cuticle thickens markedly and accumulates heavy secretions and coarse particles, producing a rectangular outline in profile, a feature not recorded for T. (T.) apophysis.

A particularly notable feature of the new species is the exceptional degree of thickness contrast between the subdorsal and subventral somatic setae in males. Such an extreme form of dimorphism has not previously been reported within Tricoma (Tricoma). In several congeners, differences in somatic setae are limited to gradual changes in length toward the posterior body or minor disparities between the two longitudinal rows [6,13]. For example, in T. (T.) disparseta Lee et al., 2024 and T. (T.) coralicolla Decraemer, 1987, the subventral setae are roughly twice as long as the subdorsal setae and arise from higher peduncles—representing the clearest length-based dimorphism known to date [8,22]. Similarly, in T. (T.) bipapillata Decraemer, 1987 and T. (T.) parvaspiculata Decraemer, 1987, the subventral setae have been described as only slightly thicker than the subdorsal ones [22]. In contrast, T. (T.) discrepans sp. nov. exhibits an unprecedented degree of disparity: the subventral setae, representing the most pronounced expression of setal dimorphism recorded to date within the genus. This newly recognized condition broadens the known range of somatic seta variability in Tricoma and provides new insight into the evolutionary diversification of cuticular structures within the group.

3.2. Tricoma (Tricoma) parasetosa sp. nov. (Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9, Table 3)

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:43BAF75F-3942-453E-A468-CD0F76082D13

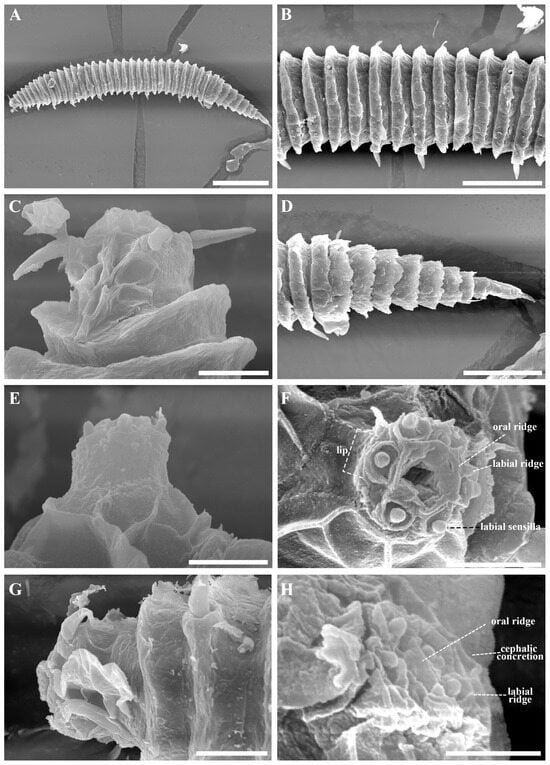

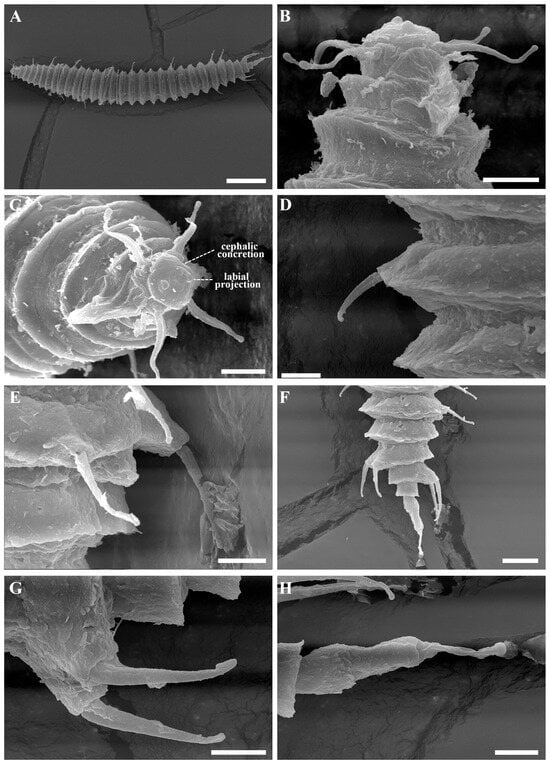

Figure 6.

Tricoma (Tricoma) parasetosa sp. nov. (A) entire body, holotype male; (B) head region, holotype male; (C) posterior region showing spicules and gubernaculum, paratype male (KIOST NEM-1-2924); (D) head region, paratype female (KIOST NEM-1-2928); (E) posterior region, paratype female (KIOST NEM-1-2928); (F) entire body, (KIOST NEM-1-2928). Scale bars: (A,F) = 50 µm; (B,D) = 10 µm; (C,E) = 20 µm.

Figure 7.

Tricoma (Tricoma) parasetosa sp. nov. SEM micrographs of the male. (A) entire body; (B) midbody cuticles; (C) head region showing amphidial fovea; (D) en face view of labial region; (E) posterior region; (F) pointed spicule projecting beyond the body wall; (G) two pairs of somatic setae inserted on the massive peduncle in the mid-tail region; (H) terminal ring. Scale bars: (A) = 50 µm; (B) = 10 µm; (C,D,F–H) = 5 µm; (E) = 15 µm.

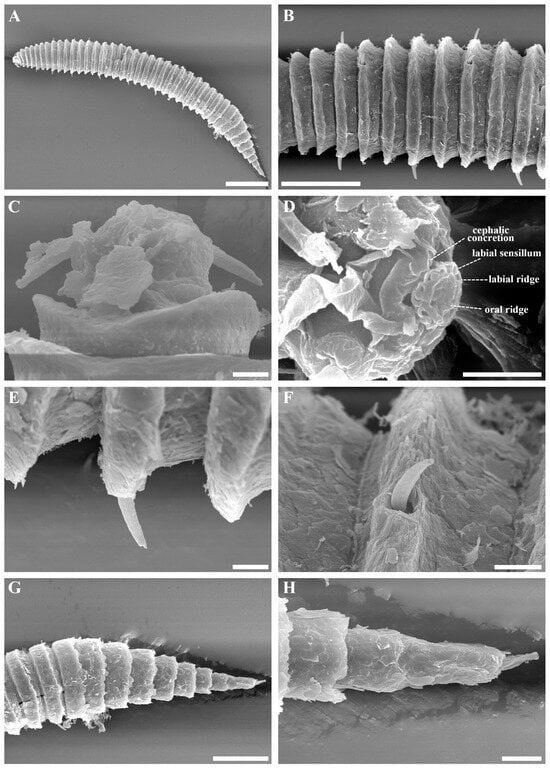

Figure 8.

Tricoma (Tricoma) parasetosa sp. nov. SEM micrographs of the female. (A) entire body; (B) head region showing amphidial fovea; (C) en face view of labial region; (D) subdorsal setae; (E) anal tube; (F) tail region; (G) two pairs of somatic setae inserted on the massive peduncle in the mid-tail region; (H) terminal ring. Scale bars: (A) = 50 µm; (B–E,G,H) = 5 µm; (F) = 15 µm.

Figure 9.

Tricoma (Tricoma) parasetosa sp. nov. DIC photomicrographs. (A) Entire body, holotype male; (B) head region, holotype male; (C) amphideal fovea, holotype male; (D) head region, paratype male (KIOST NEM-1-2872); (E) posterior body region showing spicules and gubernaculum, holotype male; (F) spicules and gubernaculum, paratype male (KIOST NEM-1-2924); (G) head region, paratype female (KIOST NEM-1-2928); (H) amphideal fovea, paratype female (KIOST NEM-1-2928); (I) posterior body region showing massive somatic setae, paratype female (KIOST NEM-1-2928); (J) entire body, paratype female (KIOST NEM-1-2928). Scale bars: (A,J) = 50 µm; (B–D,G,H) = 5 µm; (E–J) = 10 µm.

Table 3.

Morphometric measurements of Tricoma (Tricoma) parasetosa sp. nov. (µm).

Table 3.

Morphometric measurements of Tricoma (Tricoma) parasetosa sp. nov. (µm).

| Males | Females | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Holotype | Paratypes (n = 4) | Paratypes (n = 4) | |

| Body length | 330 | 330.5 ± 9.7 (317–343) | 384.3 ± 5.4 (378–392) |

| Body ring count | 31 | 31.3 ± 0.4 (31–32) | 31.0 ± 0.0 (31–31) |

| a | 8.6 | 8.7 ± 0.2 (8.6–9.0) | 7.9 ± 0.2 (7.6–8.1) |

| b | 6.9 | 7.6 ± 1.0 (6.4–9.0) | 7.1 ± 0.4 (6.6–7.7) |

| c | 4.6 | 4.8 ± 0.2 (4.6–5.0) | 5.6 ± 0.3 (5.2–6.1) |

| c′ | 2.8 | 2.4 ± 0.3 (2.1–2.8) | 2.2 ± 0.2 (2.0–2.4) |

| Head diameter at cephalic setae level | 8 | 7.7 ± 0.7 (7–8) | 9.1 ± 0.6 (8–10) |

| Head length | 6 | 6.2 ± 1.0 (5–8) | 6.1 ± 0.5 (5–7) |

| Body diameter at cardia level | 32 | 31.1 ± 1.3 (29–33) | 36.9 ± 1.8 (34–39) |

| Maximum body diameter | 38 | 38.1 ± 1.8 (35–40) | 48.8 ± 1.4 (46–50) |

| Cephalic setae | 6 | 7.5 ± 0.8 (7–9) | 8.5 ± 0.8 (8–10) |

| Amphidial fovea length | 13 | 11.9 ± 0.2 (12–12) | 13.0 ± 1.0 (11–14) |

| Pharynx length | 48 | 43.9 ± 4.3 (38–50) | 54.0 ± 2.8 (50–58) |

| Subventral setae count (right side) | 9 | 8.8 ± 0.4 (8–9) | 8.8 ± 0.4 (8–9) |

| Subventral setae count (left side) | 9 | 8.8 ± 0.4 (8–9) | 8.5 ± 0.5 (8–9) |

| Maximum subventral setae length | 13 | 14.7 ± 0.8 (13–16) | 18.2 ± 1.2 (17–20) |

| Minimum subventral setae length | 5 | 6.7 ± 0.8 (6–7) | 6.9 ± 0.6 (6–8) |

| Subdorsal setae count (right side) | 5 | 4.8 ± 0.4 (4–5) | 5.0 ± 0.0 (5–5) |

| Subdorsal setae count (left side) | 5 | 5.0 ± 0.0 (5–5) | 5.0 ± 0.0 (5–5) |

| Maximum subdorsal setae length | 11 | 12.5 ± 0.4 (12–13) | 15.2 ± 1.6 (13–18) |

| Minimum subdorsal setae length | 5 | 6.7 ± 0.8 (6–7) | 6.7 ± 0.6 (6–8) |

| Spicule length | 30 | 25.9 ± 1.1 (24–27) | – |

| Gubernaculum length | 26 | 21.6 ± 2.6 (17–24) | – |

| Distance from anterior end to vulva | – | – | 214.2 ± 2.2 (211–217) |

| Body diameter at vulval level | – | – | 40.5 ± 1.1 (39–42) |

| Vulval position (V%) | – | – | 55.8 ± 0.3 (55–56) |

| Anal body diameter | 25 | 29.1 ± 2.1 (26–31) | 31.6 ± 0.9 (31–33) |

| Tail length | 72 | 68.7 ± 2.5 (66–72) | 68.9 ± 4.4 (62–74) |

| Tail ring count | 6 | 6.0 ± 0.0 (6–6) | 5.0 ± 0.0 (5–5) |

| Terminal ring length | 29 | 28.1 ± 2.3 (24–30) | 31.7 ± 3.1 (27–35) |

| Terminal ring width | 8 | 7.1 ± 0.5 (7–8) | 8.3 ± 0.3 (8–9) |

| Spinneret length | 8 | 9.6 ± 0.5 (9–10) | 11.2 ± 0.9 (10–12) |

3.2.1. Material Examined

The holotype male (MABIK NA00158851), prepared in glycerin on an HS slide, is housed in the Marine Biodiversity Institute of Korea (MABIK), Seocheon. The paratype series comprises four males (KIOST NEM-1-2921–2924) and four females (KIOST NEM-1-2925–2928), all of which are held in the Bio-Resources Bank of Marine Nematodes (BRBMN) at the East Sea Research Institute, Korea Institute of Ocean Science and Technology (KIOST).

3.2.2. Type Locality and Habitat

The type material derives from subtidal muddy sediments collected at Site 1 near Jindo Island, Korea (34°21′9.22″ N, 126°14′47.78″ E). Specimens were taken on 20 May 2025 using a Van Veen grab at a depth of 13 m. The substratum consisted predominantly of fine mud with moderate organic enrichment. At the time of sampling, bottom-water temperature measured 14.4–14.6 °C, and salinity was between 33.3 and 33.4‰.

3.2.3. Etymology

The name parasetosa incorporates the Greek prefix para- (“near” or “similar to”), referring to its resemblance to Tricoma (Tricoma) setosa Soetaert and Decraemer, 1989.

3.2.4. Measurements

Morphometric data are presented in Table 3.

3.2.5. Diagnosis

Tricoma (Tricoma) parasetosa sp. nov. can be recognized by the following suite of diagnostic features: (1) a small, slender body with 31 main rings (rarely 32); (2) a pentagonal head outline in lateral view, with truncated anterior end; (3) a labial region lacking distinct lips, bearing two conspicuous projections and a thick cephalic concretion; (4) long and slender cephalic setae, measuring 0.8–1.2 times the head diameter, inserted on low peduncles at mid-head level; (5) a vesicular amphidial fovea extending posteriorly to the second main ring; (6) somatic setae arranged in 4–5 subdorsal and 8–9 subventral setae on each side; (7) two posterior pairs of somatic setae at main rings 28–29 inserted on massive peduncles and strongly developed; (8) spicules with a weak proximal capitulum and a gubernaculum with an anteriorly directed apophysis; and (9) a tail consisting of six main rings in males and five in females, with a conical to cylindrical terminal ring and a slender spinneret.

3.2.6. Description

Males: The male body is slender and narrows progressively toward both extremities. All examined specimens, including the holotype, possess 31 main rings, except for a single paratype with 32 rings. Each main ring bears secondary annulation and is covered with secreted material and fine sediment particles, giving the cuticle a rounded to slightly angular appearance (Figure 6A, Figure 7A and Figure 9A).

In the lateral view, the head has a pentagonal outline, with the anterior end truncated (Figure 6B and Figure 9B,D). A thin granular layer covers most of the cephalic cuticle except the labial region (Figure 7C). The lips and labial sensilla are indistinct, and the oral aperture are not clearly distinguishable. Two prominent projections are observed within the labial region (Figure 7D). A thick cephalic concretion forms a visible ridge immediately posterior to the labial region (Figure 7C). Cephalic setae are elongated and taper from a cylindrical base to perforated distal tips, arising from short peduncles at mid-head level (Figure 9D).

The amphidial fovea is vesicular and occupies the lateral portion of the head, extending from the labial region to the second main ring (Figure 6B, Figure 7C and Figure 9C). The stoma is cylindrical, extremely small, and difficult to distinguish. The pharynx is cylindrical, thickened anterior to the nerve ring, constricted posterior to it, and gradually broadening toward the posterior (Figure 6A and Figure 9A). The pharyngo-intestinal junction is positioned main rings 7–8 in the holotype (5–8 in paratypes). The nerve ring encircles the pharynx around main rings 3–4 or 4–5. The cardia is relatively large, composed of cellular tissue, and protrudes slightly into the anterior part of the intestine. The intestine is broad and cylindrical, containing numerous fine granules.

Somatic setae are arranged in one subdorsal and one subventral longitudinal row on each side, with 4–5 subdorsal setae and 8–9 subventral setae. Most setae measure 5–7 µm in length and approximately 1 µm in thickness, taper distally, and are inserted directly into the desmos or onto low peduncles (Figure 7B). In contrast, two pairs of setae—located subdorsally at ring 28 and subventrally at ring 29—are more conspicuously developed, inserted on high peduncles (6–7 µm long), and measure 11–13 µm (subdorsal) and 13–16 µm (subventral) in length, with a thickness of 2–3 µm (Figure 6C, Figure 7E,G and Figure 9E). This pattern may vary slightly depending on body orientation, and some setae may be broken.

For the holotype male, the somatic setae pattern is summarized below:

| subdorsal | left side: | 9,11,16,24,28 | =5 |

| right side: | 3,9,16,21,28 | =5 | |

| subventral | left side: | 4,6,9,12,16,19,22,25,29 | =9 |

| right side: | 3,6,9,12,16,20,22,25,29 | =9 |

For the paratype males, the somatic setae pattern is likewise summarized below, with bracketed numbers indicating positional variation:

| subdorsal | left side: | 6(8,10),11(12,13),17(19),24(25),28 | =5 |

| right side: | 4(3),8(9,10),15(14,16),20(21),28 | =5(4) | |

| subventral | left side: | 3,6(7),9(8,10),12(13),15(16),19,22,25,29 | =9(8) |

| right side: | 3(4),6(5),9(8,10),11(13),15(16,17),18(19),21(22),25(26),29 | =9(8) |

The male reproductive system is diorchic, containing two testes. Spicules emerge through the ventral body wall between main rings 25–26; they are gently arched, distally tapered, and possess a faint capitulum (Figure 6C, Figure 7F and Figure 9E). The gubernaculum is long and slender, slightly shorter than the spicules, parallel to them, with a sclerotized, anteriorly directed apophysis (Figure 6C and Figure 9F).

The tail comprises six main rings arranged in relatively close succession. The two pairs of strongly developed somatic setae borne on massive peduncles are located in the mid-tail region. The terminal ring ranges from conical to cylindrical, with its cuticle slightly thickened except at the spinneret (Figure 7H). The spinneret is long and narrow, making up 29–37% of the terminal-ring length.

Females: Females resemble males in overall habitus, head shape, and tail structure, including the presence of two posterior pairs of long somatic setae on elevated peduncles (Figure 6D–F, Figure 8A–H and Figure 9G–J). All examined females possess 31 main rings, each ring showing secondary annulation and a surface layer of secreted material and fine particles. Somatic setae are arranged in two subdorsal and two subventral rows, consisting of 5 subdorsal and 8–9 subventral setae, respectively.

For the paratype females, the somatic setae pattern is likewise summarized below, with bracketed numbers indicating alternative positions:

| subdorsal | left side: | 8(7),13(11,12),18(17),25(24,26),28 | =5 |

| right side: | 4(3,5),10(8,9),15,21,28 | =5 | |

| subventral | left side: | 4(3),7(6),10(11),15(13,14),18(17),20(21),24(25),26,29 | =9(8) |

| right side: | 3(4),7(6),10(9,11),14(12),17(16,18),20(21),24,26,29 | =9(8) |

The female reproductive system is didelphic with appositely directed gonadal branches, and the vulva is situated between rings 19–20. The anal tube (5–7 µm) extends outward from the ventral body wall (Figure 8E). The female tail consists of five main rings and is slightly shorter than that of the male (Figure 6E, Figure 8F and Figure 9I). The terminal ring is conical to cylindrical with its cuticle moderately thickened except at the spinneret (Figure 8H). The spinneret is slender and elongated, occupying 34–37% of the terminal-ring length.

3.2.7. Differential Diagnosis and Relationships

Tricoma (Tricoma) parasetosa sp. nov. most closely resembles T. (T.) setosa Soetaert and Decraemer, 1989 in overall morphology. Both species share a distinctive feature: two pairs of conspicuously developed posterior somatic setae positioned on massive peduncles, forming robust and elongate structures that are unique within the genus and absent in other described congeners [21]. Despite this notable similarity, the two species can be clearly differentiated by a combination of morphological and ecological traits. Morphologically, T. (T.) parasetosa sp. nov. possesses 31 main rings (rarely 32), whereas T. (T.) setosa has 46 main rings, which constitutes a clear diagnostic distinction. Both species exhibit an anteriorly truncated head with prominent cephalic setae; however, T. (T.) parasetosa sp. nov. has a pentagonal head outline with slightly truncated upper corners, while T. (T.) setosa shows a more triangular head shape.

The amphidial fovea also differs in extension: in T. (T.) parasetosa sp. nov., the vesicular amphid extends to the second main ring, whereas in T. (T.) setosa it reaches only the first ring. The somatic setae patterns further separate the two species—T. (T.) parasetosa sp. nov. has 4–5 subdorsal and 8–9 subventral setae on each side, whereas T. (T.) setosa bears 7 and 10, respectively. Although their reproductive systems conform to the general pattern observed in the subgenus Tricoma, the gubernaculum of T. (T.) parasetosa sp. nov. bears an anteriorly directed apophysis, whereas that of T. (T.) setosa has dorsocaudally directed, meandering apophyses. The tail configuration likewise differs: T. (T.) parasetosa sp. nov. has six main rings in males and five in females, compared with nine in males of T. (T.) setosa.

Ecologically, the two species are found in markedly different habitats. Tricoma (T.) setosa originates from a deep-sea transect off Calvi, Corsica (Mediterranean), at a depth of approximately 990 m, whereas T. (T.) parasetosa sp. nov. was obtained from shallow subtidal muddy sediments near Jindo Island, Korea, at a depth of 13 m. These marked differences in depth and habitat strongly indicate ecological separation between the two species.

Although T. (T.) setosa was described from only two male specimens, limiting evaluation of intraspecific variability, species of Tricoma with fewer than 40 main rings typically show only 1–3 rings of intraspecific variation [7]. Therefore, the large differences in ring number and associated morphological traits between T. (T.) parasetosa sp. nov. and T. (T.) setosa cannot be attributed to individual variation but instead reflect true species-level distinctions.

Taken together, these morphological and ecological differences strongly support the recognition of T. (T.) parasetosa sp. nov. and T. (T.) setosa as distinct and valid species, while also suggesting a close phylogenetic affinity between them within the subgenus Tricoma (Tricoma).

4. Discussion

Tricoma (Tricoma) discrepans sp. nov. and T. (T.) parasetosa sp. nov., exhibit distinctive morphological features that clearly differentiate them from previously known congeners, particularly in the configuration of the tail rings, somatic setae pattern, and the ultrastructure of the oral region. In T. (T.) discrepans sp. nov., the cuticle is markedly thickened, and the pronounced overlap of the posterior margins of the main rings obscures the secondary annulations—an uncommon structural condition not documented in other Korean Tricoma species. Moreover, males exhibit exceptionally thick ventral somatic setae that are approximately twice as thick as the dorsal setae along corresponding body regions. This pronounced ventral–dorsal contrast represents a unique form of sexual dimorphism within the subgenus and is entirely absent in females, providing a stable diagnostic character for the species. In T. (T.) parasetosa sp. nov., two posterior pairs of somatic setae are inserted on conspicuously enlarged peduncles and are significantly more strongly developed than the remaining somatic setae. Although this character is shared only with in T. (T.) setosa Soetaert and Decraemer, 1989, the new species differs markedly in the number of main rings, head morphology, amphidial fovea extension, and somatic setae pattern, reinforcing its distinct taxonomic identity.

The ultrastructure of the labial region further provides important diagnostic characters for species-level discrimination. In T. (T.) discrepans sp. nov., the oral aperture is surrounded by a distinct oral ridge, encompassed by six lips that each form a circular labial ridge bearing an inner labial papilla. When the lips open, the labial region protrudes anteriorly and forms a double concentric cuticular ring structure; when closed, the lips retract into the cephalic capsule, producing a triple concentric appearance. This condition matches the observations by Shirayama and Hope (1992) [15], who also reported three concentric cuticular rings around the oral region in Tricoma specimens with a closed mouth. In contrast, T. (T.) parasetosa sp. nov. does not display a clearly defined oral aperture or distinct labial sensilla. Instead, two prominent lateral labial projections and a well-developed cephalic concretion ridge are present. Although these features were consistently observed in the two SEM-processed specimens examined, their interpretation remains tentative due to the potential influence of adhering particles, fixation-related lip posture, or SEM preparation artifacts. Additional SEM material—particularly specimens preserved with minimal distortion—will be required to determine whether these features represent stable morphological traits.

Among Tricoma species previously reported from Korean coastal sediments, the morphology of the labial region shows clear interspecific variation, and in certain taxa its appearance differs depending on the degree of oral opening [9]. The absence of a triple concentric cuticular ring structure in some species supports earlier assertions that minute oral region structures—such as lip shape, labial sensilla configuration, and the presence or absence of concentric cuticular rings—constitute critical diagnostic features within Desmoscolecidae. The present study highlights how detailed SEM-based analyses can uncover previously unrecognized combinations of characters in Tricoma, thereby refining the comparative morphological framework for the group. Future research integrating standardized molecular markers, such as COI and 18S rRNA, will complement these morphological insights and contribute to a more robust and comprehensive approach to species delimitation.

5. Conclusions

The two new species, T. (T.) discrepans sp. nov. and T. (T.) parasetosa sp. nov., described from fine-grained subtidal sediments near Jindo Island, significantly expand the known morphological diversity of the subgenus Tricoma (Tricoma). In T. (T.) discrepans, distinctive characters include a markedly thickened and overlapping tail ring structure and a pronounced sexual dimorphism in somatic setae thickness. In T. (T.) parasetosa, the presence of conspicuously pedunculate posterior somatic setae represents a rare modification within the genus. These findings underscore the taxonomic importance of high-resolution SEM observations for accurately characterizing species-level differences within Desmoscolecidae. Continued sampling, expanded comparative morphology, and the future integration of molecular datasets will be essential for refining species boundaries and resolving phylogenetic relationships within Tricoma (Tricoma).

Author Contributions

H.J.L. conducted data curation and prepared the original manuscript draft. H.L. and S.H. carried out the investigation. H.S.R. was responsible for manuscript review and editing, as well as funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was primarily supported by the Marine Fishery Bio-resources Center Management Program (2025), funded as a major program grant by the National Marine Biodiversity Institute of Korea (MABIK) (PG54750). Additional support was provided by the Korea Institute of Ocean Science and Technology (KIOST) through the projects “Development of Original Technology to Verify Factors Influencing Barren Ground on the East Sea Coast under Climate Change (PEA0305)” and “Strengthening the Capacity to Analyze and Assess Marine Environment and Ecosystem Variability in the Waters Surrounding the Korean Peninsula (PEA0301)”.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further information is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Freudenhammer, I. Desmoscolecida aus der Iberischen Tiefsee, Zugleich Eine Revision Dieser Nematoden-Ordnung; G. Borntraeger: Berlin, Germany, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Decraemer, W.; Smol, N. Orders Chromadorida, Desmodorida and Desmoscolecida. In Freshwater Nematodes: Ecology and Taxonomy; Abebe, E.A.I., Traunspurger, W., Eds.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2006; pp. 497–573. [Google Scholar]

- Decraemer, W.; Rho, H.S. Order Desmoscolecida. In Handbook of Zoology: Gastrotricha, Cycloneuralia and Gnathifera, Volume 2: Nematoda; Schmidt-Rhaesa, A., Ed.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 351–372. [Google Scholar]

- Bezerra, T.N.; Pape, E.; Hauquier, F.; Vanreusel, A. Description and distribution of Erebussau nom. nov. pro Erebus Bussau, 1993 nec Erebus Latreille, 1810 with description of a new specie, and of Odetenema gesarae gen. nov., sp. nov. (Nematoda: Desmoscolecida) from nodule-bearing abyssal sediments in the Pacific. Zootaxa 2021, 4903, 542–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riemann, F. The enigmatic mineral particle accumulations on the cuticular rings of marine desmoscolecoid nematodes structure and significance explained with clues from live observations. Meiofauna Mar. 2010, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Decraemer, W. Morphological and taxonomic study of the genus Tricoma Cobb (Nematoda: Desmoscolecida), with the description of new species from the Great Barrier Reef of Australia. Aust. J. Zool. 1978, 26, 1–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Lee, H.; Rho, H.S. Six species of Tricoma (Nematoda, Desmoscolecida, Desmoscolecidae) from the East Sea, Korea, with a bibliographic catalog and geographic information. Korean J. Environ. Biol. 2023, 41, 570–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Lee, H.; Kihm, J.-H.; Rho, H.S. Tricoma (Tricoma) disparseta sp. nov. (Nematoda: Desmoscolecidae), a new free-living marine nematode from a seamount in the Northwest Pacific Ocean, with a new record of T. (T.) longirostris (Southern, 1914). Diversity 2024, 16, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Lee, H.; Rho, H.S. Taxonomic study of free-living marine nematodes in the subgenus Tricoma (Desmoscolecida: Desmoscolecidae) from the subtidal zone of the East Sea, Korea, with Insights into the ultrastructure of the lip region. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, K.G.M.T.; Manokaran, S.; Raja, S.; Boufahja, F. Two new species of Tricoma Cobb, 1894 (Nematoda: Desmoscolecidae) from the continental shelf of Bay of Bengal, India (Indian EEZ). J. Ocean. Univ. China 2025, 24, 1045–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afnan, N.M.; Mohan, P. Two new and an existing species of Tricoma (Nematoda: Desmoscolecidae) from the shallow subtidal zone of South Andaman Island, India. Invertebr. Zool. 2025, 22, 274–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipjev, I. Encore sur les Nematodes libres de la Mer Noire. Tr. Stavropol’skogo Sel’skokhozyaistvennogo Instituta 1922, 1, 83–184. [Google Scholar]

- Timm, R.W. A Revision of the Nematode Order Desmoscolecida Filipjev, 1929; University of California Publications in Zoology: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1970; Volume 93, pp. 1–115. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach, S.; Riemann, F. The Bremerhaven Checklist of Aquatic Nematodes. A Catalogue of Nematoda Adenophorea Excluding the Dorylaimida. Part I; Institut für Meeresforschung in Bremerhaven: Bremerhaven, Germany, 1973; Volume 4, pp. 1–404. [Google Scholar]

- Shirayama, Y.; Hope, W.D. Cephalic tubercles, a new character useful for the taxonomy of Desmoscolecidae (Nematoda). Trans. Am. Microsc. Soc. 1992, 111, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.-W.; Chang, C.-Y. Tricoma (Quadricoma) jindoensis, a new species of marine interstitial Nematoda (Desmoscolecida: Desmoscolecidae) from Jindo Island, Korea. Anim. Syst. Evol. Divers. 2005, 5, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kil, H.J.; Yoon, S.H.; Kim, W.; Choe, B.L.; Sohn, H.J.; Park, J.K. Faunistic investigation for marine mollusks in Jindo Island. Anim. Syst. Evol. Divers. 2005, 5, 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Choe, Y.; Shin, Y.; Kim, T.; Park, J.; Park, J.-K. Marine Molluscan Fauna of Jindo Island. Anim. Syst. Evol. Divers. 2016, 9, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, R. An improved protocol for separating meiofauna from sediments using colloidal silica sols. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Series 2001, 214, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirayama, Y.; Kaku, T.; Higgins, R.P. Double-sided microscopic observation of meiofauna using an HS-slide. Benthos Res. 1993, 1993, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soetaert, K.; Decraemer, W. Eight new Tricoma species (Nematoda, Desmoscolecidae) from a deep-sea transect off Calvi (Corsica, Mediterranean). Hydrobiologia 1989, 183, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decraemer, W. Tricominae (Nematoda: Desmoscolecida) from Laing Island, Papua New Guinea, with descriptions of new species. Invertebr. Taxon. 1987, 1, 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).