Abstract

Designed to mitigate the significant low-frequency vibration and noise inherent in conventional marine centrifugal pump systems, the magnetic levitation pump constitutes a novel form of centrifugal pump employing active magnetic bearing technology. While this fully levitated design effectively enhances vibration and noise performance, it results in the complete immersion of the rotor within a confined fluid domain, which contains narrow fluid clearances. This poses significant challenges for the accurate computation of rotor wet modes, which is crucial for the structural design of the rotor system to avoid the resonance induced by flow. Despite exerting a substantially greater influence on rotor wet modal characteristics than unconfined domains, the analysis of rotors under confined fluid conditions has received comparatively little research attention. This study focuses on two types of magnetic levitation pump rotors. From the perspective of analytical modeling, an improved analytical method for wet modal computation based on added mass correction is proposed. The validation of this method included examining two distinct computational approaches for the added mass, the thickening treatment for axially elongated disk components, and the methodology for implementing disk equivalent density. Based on this foundation, wet modal analysis was performed on both rotors utilizing the proposed analytical method, alongside acoustic fluid–structure interaction simulations. The results indicate that for the first bending mode, the errors between the analytical and experimental values are 1.2% and 4.1%, respectively, while the discrepancies between the simulated and experimental values are 0.1% and 3.2%. Finally, regularity analysis was conducted on the wet modal characteristics of the rotor under confined water, considering various fluid clearances. The results reveal that the first three bending modes generally exhibit an increasing trend with the enlargement of the fluid clearance, with a triple-size annulus serving as a transition point. However, increasing the annulus size does not always elevate the modal frequencies above their initial values. This study contributes to understanding the influence mechanisms of confined water on the wet modal properties of magnetic levitation pump rotors. Furthermore, the proposed analytical method improved computational efficiency for the early design stages of water-immersed rotors, alongside a model of greater accuracy essential for magnetic bearing control.

1. Introduction

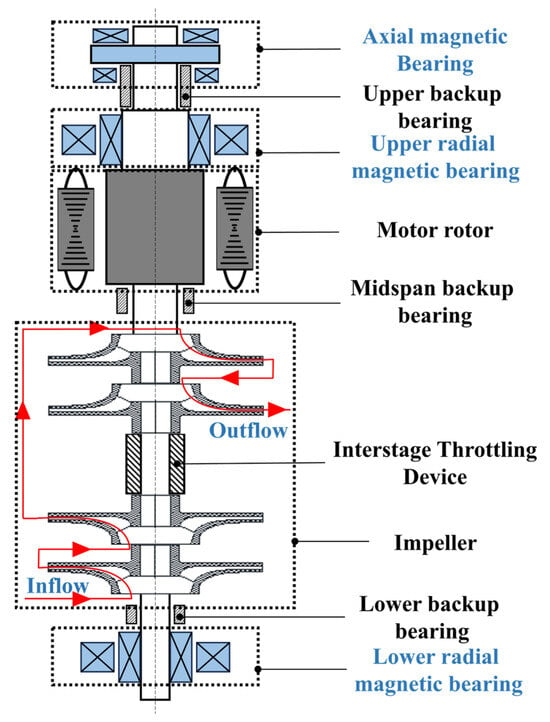

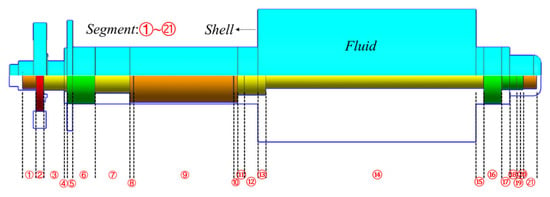

Marine centrifugal pumps are critical components for energy conversion and fluid transportation [1,2], with broad applications in ship and ocean engineering. However, as one of the primary sources of low-frequency vibration and noise aboard ships, the low-frequency vibration and acoustic issues associated with traditional marine pump units not only significantly impair their operational efficiency and reliability, but also adversely affect the overall acoustic radiation characteristics of the vessel [3,4,5]. However, traditional passive vibration and noise reduction measures (e.g., vibration isolators) have approached their performance limits. It is therefore necessary to address vibration and noise at the source. In this context, the magnetic levitation pump has emerged as a novel type of centrifugal pump. Its rotor features an integrated motor-pump design and is fully supported by non-contact active magnetic bearings, enabling complete rotor levitation under controlled conditions (Figure 1). A high-bandwidth active vibration control algorithm, derived from a model of the rotor-magnetic bearing system, enables the bearings to produce controllable electromagnetic forces within the mid-to-low frequency spectrum, thereby mitigating vibration and noise at their source.

Figure 1.

Structural topology of a typical multistage vertical magnetic levitation pump.

However, the highly integrated and fully levitated design of the rotor results in its complete immersion in a confined water environment, surrounded by the pump casing with multiple extremely narrow annular fluid clearances. The presence of this confined domain makes it challenging to accurately calculate the rotor’s modal properties. Consequently, a large safety margin often must be reserved during the initial design stage of magnetic levitation pump rotors to avoid resonance points, which is detrimental to optimal structural design. Therefore, the accurate identification of modal parameters for submerged rotors is crucial for preventing flow-induced resonance and for optimizing rotor design. Conventionally, analytical methods are frequently employed in the early design phase to rapidly assess modal characteristics and determine optimization directions. Similarly, the implementation of active vibration control in magnetic bearings relies on a precise analytical model of the rotor-bearing system. However, traditional analytical methods exhibit significant errors in predicting rotor wet modes, primarily due to difficulties in accurately calculating the added mass of the water-immersed structure. Therefore, the precise identification of rotor modal characteristics under confined fluid conditions and the development of a corresponding rotor dynamic analytical model suitable for submerged conditions are of critical importance. They are crucial for addressing the challenge of predicting wet modal response, enabling early-stage optimization of submerged rotor design, and achieving high-precision magnetic bearing control.

Therefore, this paper first conducts, from an analytical perspective, a review of the literature concerning the calculation methods for added mass, a parameter of paramount importance in rotor wet modal analysis. As a typical fluid–structure interaction problem, the analytical modeling of rotor wet modes must account for the influence of the surrounding fluid, in addition to the conditions in the dry mode conditions. This influence is primarily manifested through added mass, added damping, and added stiffness, which significantly affect the rotor’s dynamic response [6,7,8,9]. The concept of added mass, as initially introduced by Du Buat [10], pertains to the mass of fluid accelerated by the motion of the structure. It is evident that, amongst the aforementioned effects, added mass exerts the most significant influence on wet modal characteristics. The calculation of added mass is primarily achieved through the utilization of analytical formula, computational fluid dynamics (CFD), and experimental techniques. Analytical formulas derived from potential flow theory are typically applicable to simple geometries. Extensive research exists in this area, representative studies include: T. Sarpkaya et al. [11,12] combined boundary layer and potential flow theories to derive inertial and drag coefficients for a two-dimensional cylinder in constant accelerating flow. S.S. Chen et al. [13] established formulas for the added mass and damping of a cylinder enclosed in a concentric cylindrical shell containing viscous fluid, based on assumptions of infinite length and small amplitude, and further provided simplified expressions for four special cases. P. Villaggio [14] extended the conventional added mass model for rigid cylinders in infinite fluid to the case of flexible cylinders, showing that added mass depends on the pressure distribution rather than remaining constant. S. Kaneko et al. [15] systematically compiled added mass coefficients for a range of two- and three-dimensional simple shapes in inviscid and incompressible flows. R. Lagrange et al. [16] introduced a theoretical formula for the modal added mass matrix of a vibrating flexible cylinder of finite length with classical boundary conditions, confined within a rigid outer cylindrical shell under a small annulus assumption. The Computational fluid dynamics method determines the fluid-added mass by solving for the added mass force. This objective is typically realized through the implementation of either sinusoidal oscillation or uniform translational acceleration on the fully submerged structure. The total force exerted in the direction of motion, comprising both drag and added mass force, is calculated using CFD simulation. The added mass is then obtained by isolating the inertial force component proportional to acceleration. Representative research includes the work by S. Fackrell [17], who developed a numerical model to determine the hydrodynamic forces on a cylindrical structure. Using CFD simulations, forces acting on the cylinder were analyzed under both zero and non-zero initial velocity conditions. The study further introduced two distinct methodologies for decomposing the total force into unsteady drag and added mass force; and E. Javanmard et al. [18] proposed a pioneering CFD-based methodology for evaluating the translational added mass of submerged bodies. This technique employs a multi-phase motion profile, comprising constant velocity, constant acceleration, constant velocity, and constant deceleration stages, to accurately isolate the added mass-induced inertial force, thus offering a refined alternative to conventional uniform acceleration methods. X. Wang et al. [19] proposed a numerical method for calculating the added mass force on irregularly shaped bodies undergoing accelerated motion in water, determining relevant parameters such as the added mass force through regression analysis and parameter separation analysis. Experimental methods are categorized into direct and indirect force measurement. The fundamental principle of the indirect method [20,21] is to calculate the added mass force acting on a submerged object indirectly by measuring certain physical quantities in the flow field, such as pressure difference, head loss, or velocity distribution. This method proves particularly useful in specific scenarios, for example, when measuring the added mass of irregularly shaped bodies under high blockage conditions. Direct methods [22,23], the most commonly used experimental techniques, involve measuring the total force on the moving object and decomposing it into drag and added mass force. In summary, analytical methods are straightforward and efficient but are limited to simple geometries and lack accuracy under complex conditions. Experimental techniques offer high accuracy but require stringent conditions and involve high cost and complexity. CFD methods provide a versatile and practical balance, delivering high accuracy across various geometries and conditions, albeit at higher computational time and resource costs.

Furthermore, the acoustic fluid–structure interaction method based on finite element numerical simulation is currently the mainstream approach for rotor wet modal analysis [24]. Recognized for its broad applicability and high precision, this method can comprehensively account for complex boundary conditions and influencing factors, including added mass, gyroscopic effects, spin softening, stress stiffening, prestress, and bearing stiffness. However, for large and complex geometries, it demands substantial computational time and resources. Representative studies include: M. Zhang et al. [25] conducted a numerical study on the added mass effects of a simplified blade disk structure in static water. Utilizing acoustic fluid–structure interaction techniques, they compared the strain energy percentage of the disk in both water and air under varying material densities, revealing that different parts of the submerged structure experience distinct average added mass factors. G. Peng et al. [26] conducted a series of modal analyses on a sump pump rotor, incorporating the effects of shaft length and pre-stress conditions. The results of the study indicated that stress stiffening becomes more pronounced in higher-order modes. D. Hu et al. [27] developed a model of a pump turbine runner with surrounding fluid gaps and employed acoustic fluid–structure interaction methods to evaluate how upper and lower gap fluids affect modal frequencies and mode shapes. Furthermore, a relationship was established between frequency reduction rate and added mass coefficient. Based on rotor dynamics theory and the finite element method, L. Wang et al. [28] analyzed the dry and wet modal characteristics of a variable-speed pump-turbine rotor system. J. Cao et al. [29,30] investigated the rotor of a bulb turbine unit. The research examined the contributions of gyroscopic effects, spin softening, and acoustic fluid–structure interaction across different modal orders. This research led to the proposal of a transformation matrix that incorporates gyroscopic effects for converting between dry and wet natural frequencies:

Furthermore, J. Cao et al. [31] reviewed the manifestation of fluid added mass effects in hydro-turbine rotor systems. Focusing on the runner, they specifically analyzed the influences of steady flow, clearance effects, and cavitation on the added mass. Their results indicate that the gap size between the runner and the rigid wall significantly affects the added mass, and that cavitation alters the fluid density and speed of sound, thereby impacting the added mass. Subsequently, a numerical theoretical method incorporating both added mass and gyroscopic effects for wet modal analysis was developed by the researchers based on a pump-turbine rotor system. The influence of added mass, gyroscopic moments, and bearing stiffness on rotor dynamics was analyzed.

In summary, current research on rotor wet modal characteristics under confined fluid conditions remains relatively scarce, particularly concerning scenarios with extremely narrow fluid clearances. Furthermore, constrained by limitations in accurately solving for the added mass, traditional analytical methods struggle to meet the requirements for precise wet modal calculation. Therefore, this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the theoretical foundations, including a review of calculation methods for the added mass required in analytical approaches. Subsequently, an improved analytical method for wet modal computation based on added mass correction is proposed. The theoretical foundation of the mainstream Acoustic Fluid–Structure Interaction (AFSI) method for wet modal analysis is also reviewed. Building on this, Section 3 validates the proposed methods using simple 2D and 3D models. The validation encompasses the two added mass calculation methods and the improved analytical method. Section 4 then applies both the improved analytical method and the AFSI method to analyze the wet modal characteristics of two practical magnetic levitation pump rotor. The accuracy of both computational methods is verified through experimental modal testing using magnetic bearing-based frequency sweep excitation. Finally, a regularity analysis of the wet modal characteristics of the magnetic levitation pump rotor in a confined water environment was conducted, focusing on various types of annular fluid clearance. This study aims to elucidate the influence mechanisms of confined fluid domains on the wet modal characteristics of magnetic levitation pump rotors, provide a rapid analytical calculation method for the early-stage design of submerged rotors, and deliver a more precise analytical model for magnetic bearing control.

2. Theoretical Foundations

In this section, a theoretical examination is conducted on the two approaches introduced earlier for wet modal analysis of the rotor—namely, the analytical method and the AFSI method.

2.1. Theoretical Analysis of Rotor Wet Mode via an Added Mass-Based Analytical Method

2.1.1. Analysis of Added Mass Effects

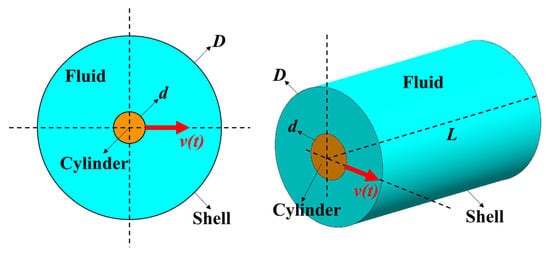

In the analytical formula, the magnetic levitation pump rotor can be modeled as a stepped shaft with attached mass disks fully submerged in a confined annular fluid domain. The added mass for each shaft segment can therefore be evaluated using the formula provided in Reference [13]. Figure 2 is a schematic showing the added mass calculation for simple models.

where represents the ratio of the inner diameter to the outer diameter of the circular ring-confined water area.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the added mass calculation for simple models.

Equation (1) is derived under the assumptions of infinite length (L/d >> 1) and inviscid flow(υ = 0). For cases that deviate from these assumptions, particularly those involving shaft segments with small aspect ratios (the ratio of the axial length to the diameter of the circular cross-section for a three-dimensional cylindrical structure, i.e., L/d), direct application of this formula tends to result in a significant overestimation of the added mass. The applicable range of the formula was therefore subsequently determined, and a CFD-based correction method was employed to refine the added mass values for shaft segments falling outside this range.

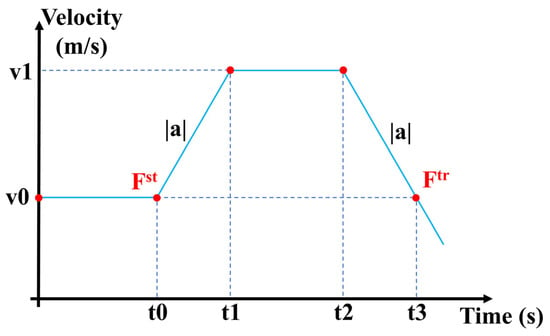

The core principle of the CFD method lies in determining the inertial component of the added mass force acting on a submerged moving body. In reference [18], a multi-stage motion profile comprising constant velocity, constant acceleration, constant velocity, and constant deceleration was imposed based on an inflow methodology (Figure 3), leading to a CFD-based formula for calculating the added mass, which can be expressed as:

where denotes the drag force acting on the object when moving at the initial velocity v0, while represents the total force exerted on the object during uniform deceleration to velocity v0. The difference between these two values corresponds to the inertial force due to added mass. Furthermore, refers to the mass of water displaced by the object, and denotes the magnitude of acceleration during the phases of both constant acceleration and deceleration.

Figure 3.

Principle schematic of the CFD method for calculating added mass.

However, for the transverse motion of a cylinder within a confined annular fluid domain, the conventional inflow methodology is not applicable. Therefore, this study employs a dynamic mesh technique, maintaining a stationary fluid domain while imposing motion on the object, to derive a formula for calculating the added mass under a multi-phase motion profile consisting of constant velocity, constant acceleration, constant velocity, and constant deceleration.

The discrepancy between the two formulas is equal to , which is the mass of water displaced by the object. This disparity primarily originates from the fact that, in the inflow methodology, the cylinder is subjected not only to the added mass force—resulting from impeding the acceleration of the surrounding fluid—but also to an additional buoyancy force equivalent to the mass of the displaced fluid, stemming from the accelerated flow field in which the cylinder is stationary.

2.1.2. Analysis of the Wet Modal Analytical Method

Starting from the analytical computation of rotor’s dry mode, the finite element-based analytical method provides superior accuracy and avoids the numerical instabilities associated with the transfer matrix method [32]. This technique discretizes the continuous rotor system into multiple mass disks, elastic shaft segments, and bearing units, interconnected through nodal points. The global equation of motion for the entire system is assembled from the nodal force-displacement relationships—the equations of motion of each element—and solved accordingly.

The equations of motion for each element type and the fully assembled system are presented below; detailed derivations are available in Reference [32].

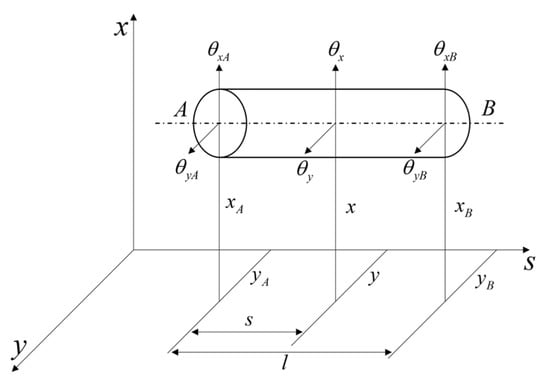

(1) Elastic shaft segments

Define as the mass per unit length of the shaft segment, E as the elastic modulus, and I as the cross-sectional moment of inertia. A schematic diagram is provided in Figure 4, where l is the length of the shaft segment element, and r is the radius of its circular cross-section.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of an elastic shaft segment.

The governing equation of motion for the elastic shaft segment is [32]:

where is the consistent mass matrix, is the translational inertia matrix, is the rotational inertia matrix, denotes the rotational angular velocity, is the gyroscopic matrix, is the stiffness matrix, and are generalized force matrices.

(2) Mass disks

Define m as the disk mass, Jp as the polar moment of inertia, and Jd as the diametral moment of inertia. The governing equation of motion for the mass disk is [32]:

where represents the disk inertia matrix, denotes the gyroscopic matrix, and and are generalized force matrices.

(3) Bearing units

Define and as the coordinates of the journal center. Assuming the bearing housing foundation is sufficiently rigid and neglecting damping effects in the bearing, the governing equation of motion for the bearing unit can be simplified to [32]:

where and represent the generalized force matrices of the bearing unit, and kx and ky denote the stiffness coefficients.

(4) The governing equation of motion for the system

By assembling the equations of all individual elements, the governing equation of motion for the system is [32]:

where , , and represent the global mass matrix, gyroscopic matrix, and stiffness matrix, respectively, and and denote the system displacement vectors.

As demonstrated by Equation (5), the analytical method accounts solely for the mass inertia effect of the disk, while neglecting its contribution to the overall stiffness. Consequently, its applicability is restricted to disk components with short axial extensions. In the case of elongated disks or components comprising multiple disks distributed continuously along the axis, the neglect of stiffness effects can lead to a significant underestimation of the modal frequencies. In the specific context of the magnetic levitation pump rotor, this study proposes a correction method for the elongated motor rotor and the continuously distributed five-stage impeller. The method involves local thickening of the corresponding shaft segments to incorporate their contribution to the global rotor stiffness. The effectiveness of this correction approach was subsequently validated.

The effect of fluid-added mass, categorized as shaft segment-added mass and disk-added mass, is incorporated through the utilization of the equivalent density method. The additional mass of a shaft segment is regarded as an integral component of the segment itself, while the additional mass of a disk is considered part of the combined disk and its corresponding shaft segment. The distribution of added mass within the rotor structure is addressed using the shaft segment equivalent density method (SSED) and the disk equivalent density method (DED), respectively. Consequently, the system equation of motion for the rotor wet modes, accounting for fluid-added mass, is derived.

2.2. Theoretical Analysis of Rotor Wet Mode via the AFSI Method

The Acoustic Fluid–Structure Interaction (AFSI) method, developed based on acoustic-structural theory, serves as a crucial tool for addressing fluid–structure interaction problems, enabling the simulation of coupled behavior between fluids and structures. Its core principle treats the fluid (e.g., water, air) as an acoustic medium, which possesses only pressure related to volumetric strain and lacks shear stress. The governing equation for the fluid domain is the acoustic wave equation, with pressure as its degree of freedom. Consequently, acoustic elements used to model the flow field (except those at the fluid–structure interface) typically possess only pressure degrees of freedom and no displacement degrees of freedom. In contrast, the governing equation for the solid domain is the equation of structural dynamics, with displacement as its degree of freedom. Coupling between the solid and fluid domains is achieved at their interface through displacement and pressure continuity conditions, thereby solving for the structural dynamic characteristics under the influence of the flow field. Unlike general FSI methods that require the full form of the Navier–Stokes equations, this method employs the acoustic wave equation derived from the linearized continuity and linearized Navier–Stokes equations. This approach not only maintains high computational accuracy but also significantly reduces computational resource consumption.

Based on the governing equations of structural dynamics, the rotor dynamic equation incorporating gyroscopic effects is derived and presented as Equation (8) [29]. Where , , and are the structural mass, damping, and stiffness matrices, respectively, and , , and represent the acceleration, velocity, and displacement vectors.

By linearizing the continuity and Navier–Stokes equations, the acoustic wave equation is derived as given in Equation (9). Where denotes the speed of sound in the fluid (K being the fluid bulk modulus), is the mean fluid density, is the dynamic viscosity, and is the acoustic pressure [30].

Equation (9) is to be discretized and reorganized into a form analogous to the structural dynamic equation [30]:

where , , , , , and represent the acoustic fluid mass matrix, damping matrix, stiffness matrix, boundary matrix, load vector, and mass density function, respectively.

By introducing the fluid pressure load into Equation (8) and coupling it with Equation (10), the overall governing equation for the AFSI problem is obtained [29,30]:

Furthermore, focusing on the rotor wet mode and setting , , and , the following Equation (12) is derived.

where is defined as the added mass matrix incorporating AFSI effects, denotes the total structural damping matrix accounting for gyroscopic effects, and represents the total structural stiffness matrix. To further include rotational damping and spin softening effects, the rotational damping matrix and the spin softening matrix must be introduced. Subsequently, the total structural stiffness matrix is modified and denoted as .

3. Computational Model and Method Validation

3.1. Model Description and Material Properties

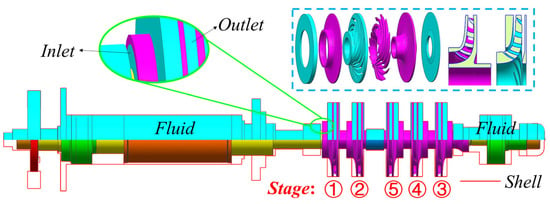

The present study investigates two categories of subjects. The first comprises simplified geometric models for method validation. The second involves practical magnetic levitation pump rotors, including both impeller-excluded and impeller-included configurations, as illustrated in Figure 5 and Figure 6. The impeller-excluded rotor assembly consists of a shaft, a thrust disk, an upper end cap, a lower end cap, an upper radial magnetic bearing, a lower radial magnetic bearing, and a motor rotor (including the core, permanent magnets, retention sleeve, and potting compound). The impeller-included configuration incorporates additional components, including a five-stage impeller, a diffuser ring, and a throttle valve. It is imperative to note that both rotor types are fully immersed in a fluid domain, the outer boundary of which is defined by the stationary pump casing.

Figure 5.

Schematic of the magnetic levitation pump rotor (without impeller).

Figure 6.

Schematic of the magnetic levitation pump rotor (with impeller).

The fluid medium is water, characterized by a density of 1000 kg/m3, a sound speed of 1500 m/s, and a dynamic viscosity of 0.001003 kg/(m·s). The structural components, incorporating the simplified models and magnetic levitation pump rotors, are principally composed of structural steel, with a density of 7850 kg/m3, a Young’s modulus of 210 GPa, and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.28, with the exception of the permanent magnets, retention sleeve, and potting compound within the motor rotor. The material properties for these exceptions are assigned as follows:

- Permanent magnets: density = 8400 kg/m3, Young’s modulus = 120 GPa, Poisson’s ratio = 0.27;

- Retention sleeve: density = 8900 kg/m3, Young’s modulus = 210 GPa, Poisson’s ratio = 0.28;

- Potting compound: density = 2400 kg/m3, Young’s modulus = 0.5 GPa, Poisson’s ratio = 0.36.

3.2. Validation of the Added Mass Calculation Method

Based on the schematic of the magnetic levitation pump rotor shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6, the segmented rotor structure can be broadly categorized into two types. The first is the cylindrical shaft segment, which corresponds to an annular confined flow domain. The second is the complex impeller structure (including blades), which corresponds to a complex impeller confined flow domain. Due to the influence of fixed domain boundary conditions, the relative inflow method is not applicable in the CFD-based calculation of added mass. Therefore, the dynamic mesh method based on User-Defined Functions (UDF) is employed. However, as the dynamic mesh method involves transient flow field computation and grid reconstruction, it demands substantial time and computational resources for domains with the complex geometry of the impeller. Nevertheless, the added mass effect of the water-immersed impeller is crucial for analyzing the overall modal and dynamic characteristics of the rotor, particularly for lateral rotor dynamics. Consequently, this study adopts the Blevins equivalent mass method to account for the impeller’s added mass. This method approximates it as the sum of the fluid mass within the impeller cavity and the fluid mass corresponding to the impeller’s swept volume. The accuracy of this method has been experimentally validated in the literature [33].

Therefore, this subsection first evaluates the accuracy of the two added mass calculation methods, using the annular confined domain corresponding to the shaft segment as the analysis object. Initially, under the conditions satisfying the infinite length and inviscid flow assumptions, the accuracy of the CFD method is validated against the results obtained from the analytical formula, given that the accuracy of the analytical method under these idealized assumptions has been extensively verified in numerous studies. Secondly, departing from the practical conditions of finite length and viscous flow, the limitations of the analytical formula are analyzed using the CFD method, and consequently, the applicable range of the analytical formula is delineated.

(1) 2D model

Given that a two-dimensional model inherently exhibits infinite axial length, a 2D cylindrical model (r = 5 mm) was selected for inviscid fluid simulations to satisfy the infinite length and inviscid flow assumptions. To account for scenarios involving confined fluid domains with narrow clearance and to accentuate the effect of added mass inertia, two segmented motion profiles combining low initial velocities and high acceleration phases were adopted:

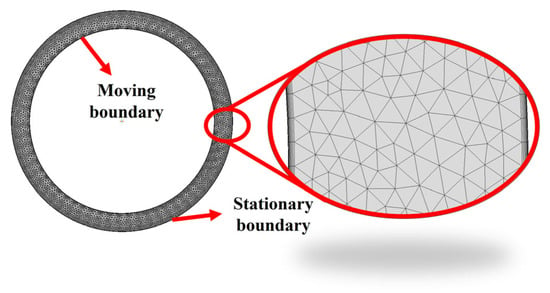

Herein, Motion profile 2 was specifically designed for conditions with extremely confined fluid domains.

Utilizing a UDF-based dynamic mesh technique, the inner cylindrical structure was imposed with a prescribed motion profile. The inner and outer boundaries were treated as no-slip walls, with boundary layer meshing applied accordingly. Moreover, for simulations representing an infinite fluid domain, the outer boundary was set as a symmetry condition. Since mesh deformation under the dynamic mesh technique is only applicable to triangular elements in 2D and tetrahedral/prism-layer elements in 3D. Consequently, the internal fluid domain was discretized using a triangular mesh, excluding the boundary layers. The boundary layer mesh surrounding the cylinder was constrained to move in synchrony with the cylindrical boundary by means of mesh partitioning. This approach prevents the degradation of the original boundary layer mesh during remeshing, thereby preserving computational accuracy.

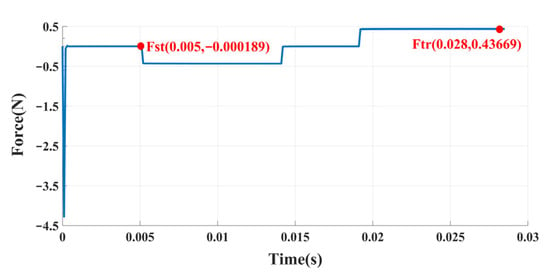

A 2D cylindrical model with a radius of 5 mm and an annular fluid gap of 1 mm is analyzed (the calculation procedure for a 3D model is analogous). As shown in the schematic of the simulation model in Figure 7, the moving boundary is defined by motion profile 1. Simulations are conducted based on an inviscid model. Consequently, the schematic diagram of the force variation on the moving boundary, shown in Figure 8, is obtained. The added mass calculated in conjunction with Equation (3) is:

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the simulation model.

Figure 8.

Diagram of the force variation on the moving boundary.

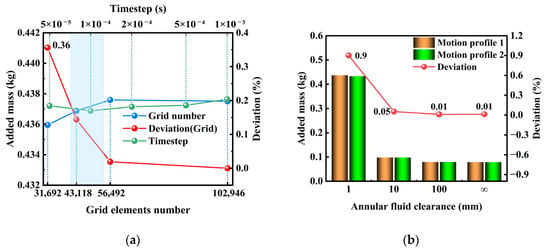

Initially, a mesh and timestep independence analysis was conducted. Figure 9a presents the results of this study for the added mass calculation of a 2D structure with a 1 mm fluid gap. The results demonstrate that the calculated added mass stabilizes when the mesh size reaches 43,118 elements, with strong agreement observed across various timestep configurations. These results validate the selected model for numerical simulation. Furthermore, an independence verification was conducted for the two motion profiles defined by Equations (13) and (14). The added mass was computed for annular fluid clearance of 1 mm, 10 mm, and 100 mm, as well as for an infinite fluid domain; the results are shown in Figure 9b. The maximum deviation between the results obtained under the two motion profiles was 0.9%, thereby confirming the independence of the added mass with respect to the specific motion profile employed.

Figure 9.

(a) Verification of grid and timestep independence (b) Validation of motion profile independence.

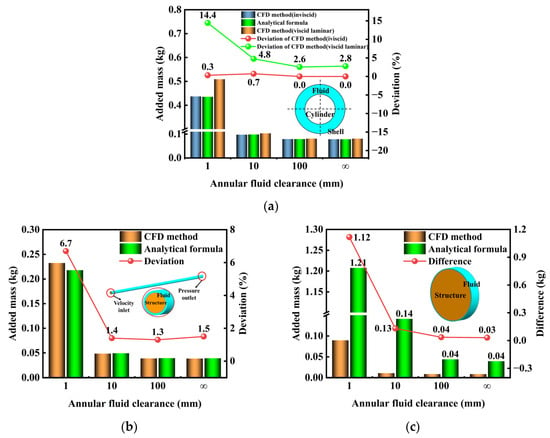

Furthermore, added mass calculations were performed for both ideal inviscid fluid and real viscous fluid utilizing an inviscid model and a viscous laminar model, respectively, across various clearance sizes. The results, presented in Figure 10a, demonstrate that: under two-dimensional conditions, the added mass values computed via the inviscid CFD model and the analytical formula are in excellent agreement, mutually validating the accuracy of both methods; however, a comparison between the results from the viscous laminar CFD model and the analytical formula reveals that fluid viscosity influences the added mass, and for this configuration, the influence of viscosity becomes more pronounced as the fluid clearance narrows. Consequently, the analytical formula introduces significant errors for practical applications involving narrow fluid clearances, necessitating correction via the CFD-based method.

Figure 10.

Added mass results for the 2D model (a); Added mass results for the 3D model (b) high aspect ratio (c) low aspect ratio.

(2) 3D model

The added mass analysis was extended to finite-length 3D structures, specifically a slender cylinder with a high aspect ratio (Model I) and a disk-like structure with a low aspect ratio (Model II). Their geometrical parameters are as follows:

- Model I: cross-sectional radius = 5 mm, length = 500 mm, aspect ratio = 50;

- Model II: cross-sectional radius = 30 mm, length = 14 mm, aspect ratio = 0.233.

To mitigate end effects, the length of the fluid domain was set to match the axial length of the structure. Zero-velocity and zero-pressure conditions were applied to the two end faces, while all structural surfaces were treated as no-slip walls. A viscous laminar model was used to compute the added mass with annular fluid clearance of 1 mm, 10 mm and 100 mm, as well as for an infinite domain. The results were compared with those obtained from the analytical formula.

As shown in Figure 10b,c, the results from the two methods are generally consistent for the high-aspect-ratio structure, with minor deviations. However, for narrow clearance, the influence of fluid viscosity becomes significant. This observation aligns with the conclusions drawn from the 2D model, indicating substantial errors in the analytical formula under these conditions. For the low-aspect-ratio structure, the analytical formula yields considerable errors regardless of the clearance size. Therefore, for applications involving either narrow fluid clearance or low-aspect-ratio structures, the results from the analytical formula must be corrected using the CFD-based method.

(3) Determination of applicable conditions for the analytical formula

Rotor shaft segments often violate the infinite-length assumption, with some even exhibiting an aspect ratio below unity. The aim of this subsection is therefore to determine the range of applicability of analytical Formula (1), identifying the segments for which the added mass must be corrected using the CFD method. To ensure generality, three distinct models were selected:

- Model III: cylinder radius = 5 mm, fluid annulus = 1 mm, initial length = 200 mm;

- Model IV: cylinder radius = 5 mm, fluid annulus = 5 mm, initial length = 200 mm.

- Model V: cylinder radius = 10 mm, fluid annulus = 10 mm, initial length = 400 mm.

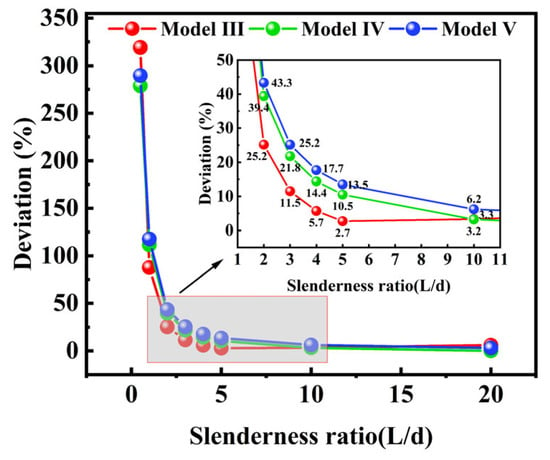

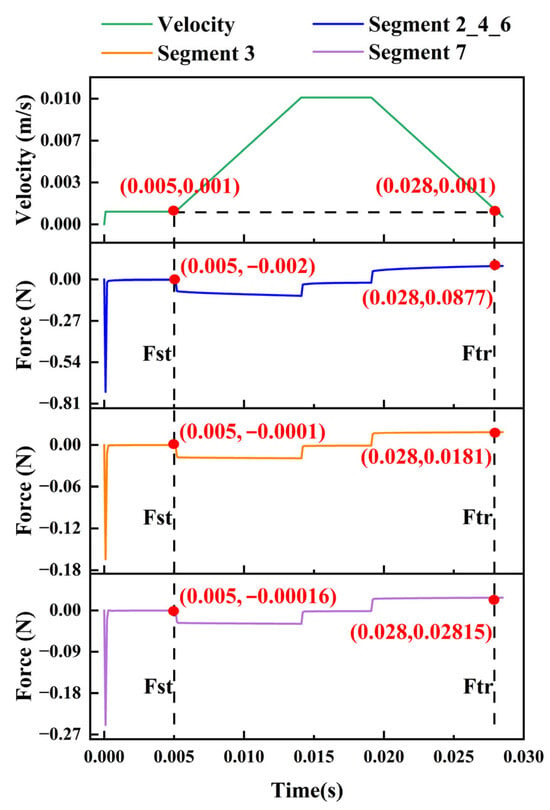

The added mass was computed using both the analytical formula method and the CFD method for aspect ratios (L/d) of 20, 10, 5, 4, 3, 2, and 1. The CFD results served as the benchmark to determine the applicability of the analytical formula with respect to the L/d ratio. The resulting deviations are presented in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Deviation in added mass calculation between two methods.

As illustrated in Figure 11: (1) Overall, the deviation of the analytical formula increases progressively as the aspect ratio decreases; (2) Comparing the results from Model IV and Model V, the analytical formula yields a significant overestimation of the added mass when L/d < 5, with deviations exceeding 10%; (3) The results from model III indicate that the deviation initially decreases and then increases as L/d decreases, reaching a minimum at L/d = 5. This behavior is attributed to the narrow fluid clearance (1 mm) in model III. Under high L/d conditions, the influence of fluid viscosity within the confined clearance becomes pronounced. As L/d increases, the effect of finite length diminishes, while viscous effects become more dominant, resulting in higher added mass values obtained via CFD compared to those from the analytical formula. Therefore, for large annular fluid clearance, the analytical formula is preliminarily determined to be applicable when L/d ≥ 5. For narrow clearance, the CFD method is recommended to account for the effects of fluid viscosity.

3.3. Validation of the Added Mass-Based Analytical Method for Wet Mode

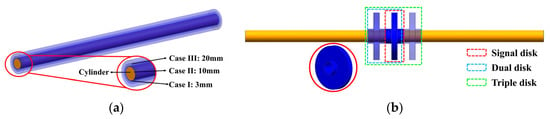

Prior to validating the wet modal analytical method, this section first verifies the treatment approach for elongated disk components along the axial direction, as discussed in Section 2.1.2. The analysis models, illustrated in Figure 12, are defined with the following parameters:

Figure 12.

Schematic of an axially extended disk component (a) Model VI; (b) Model VII.

- Model VI: A cylindrical shaft segment with a radius of 20 mm and a length of 1000 mm, assembled with three disk components of different thicknesses (3 mm, 10 mm, and 20 mm), each extending the full length of the shaft;

- Model VII: A cylindrical shaft segment with a radius of 20 mm and a length of 1000 mm, equipped with varying numbers of impeller-like disk components (single, dual, and triple disks).

Two modeling strategies were applied to these disk components:

- Method 1: Conventional lumped mass and inertia representation;

- Method 2: Treatment as a locally thickened segment of the corresponding shaft section.

For Model VII, a hybrid modeling strategy was adopted: the hub region of the disk was modeled as a thickened shaft segment, while the remaining parts were represented as lumped mass and inertia.

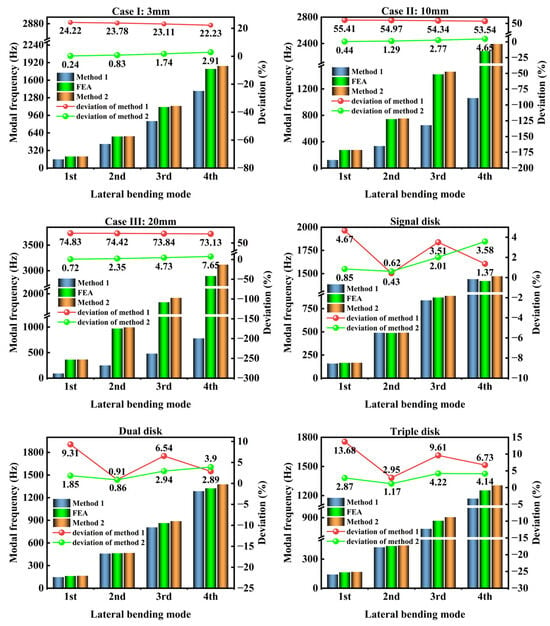

Standard frictional contact was defined at the interfaces between each disk component and the shaft segment. Under dry conditions, modal analysis was conducted for both Model VI and VII using the analytical method, and the results were compared with those from finite element simulations. As illustrated in Figure 13, the analytical results obtained using Method 2 show significantly smaller deviations from the finite element simulation results. In contrast, the conventional Method 1, which neglects stiffness effects, leads to a substantial underestimation in the analytical predictions.

Figure 13.

Comparison of different treatment methods.

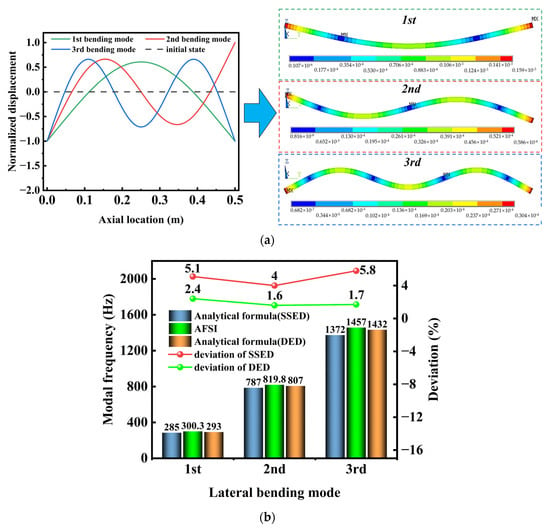

The analysis was conducted on Model I with a 1 mm annular fluid clearance. The wet modal analysis was first performed analytically. Neglecting fluid viscosity, the added mass was rapidly determined as Madd = 0.2178 kg using the analytical formula. Applying the shaft segment equivalent density (SSED) method yielded an equivalent density of 13,395 kg/m3 for the cylinder, incorporating the added mass effect. Following the theory outlined in Section 2.1.2, the cylinder was divided into 20 mm segments. The analytical solution for the cylinder’s wet mode was subsequently implemented via MATLAB 2023b programming.

Concurrently, an AFSI analysis was conducted. For spatial discretization: the cylinder was meshed with SOLID185 elements, the fluid domain with FLUID30 elements, and the outer casing with SHELL181 elements. Regarding boundary conditions: an FSI surface was defined at the cylinder-fluid interface, and an FSIN surface at the fluid-casing interface. The casing was fully constrained (u = 0), and zero pressure (P = 0) was applied at the two end sections of the fluid domain. The final results are presented in Table 1 and Figure 14a. These demonstrate excellent agreement between the wet modal analytical method and the AFSI method for the first three bending modes.

Table 1.

Comparison of modal frequencies: analytical method and AFSI.

Figure 14.

(a) Comparison of modal shapes: analytical method and AFSI; (b) Modal frequencies comparison of SSED and DED methods.

To further validate the accuracy of the wet modal analytical method, Model II was assembled onto Model I, forming a multi-disk rotor system. This configuration also served to verify the proposed disk equivalent density (DED) method. The cylindrical segment had a fluid clearance of 21 mm, while a narrow clearance of 1 mm was set at the disk to accentuate its added mass contribution. The model and its segmentation are illustrated in Figure 15. The dimensional parameters for each segment are listed in Table 2:

Figure 15.

Schematic of the multi-disk rotor model.

Table 2.

Dimensional parameters of each segment in the multi-disk rotor system.

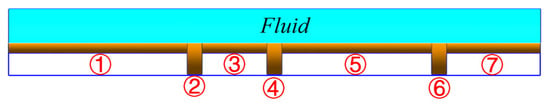

As shown in the table, the length-to-diameter ratios for Segment 1 and Segment 5 are 8.4 and 7.05, respectively. Both satisfy the applicable condition (L/d ≥ 5) for the analytical formula method. Therefore, the added mass for these two segments is calculated using the analytical formula, yielding results of 0.0649 kg and 0.0545 kg, respectively. The added mass for the remaining segments is calculated using the CFD method. Figure 16 illustrates the variation in velocity and force at the moving boundary of the remaining shaft segments. The fluid added mass is subsequently obtained as follows:

Figure 16.

Schematic of the velocity and force variation on the moving boundary.

Furthermore, the wet modal analysis for the multi-disk rotor system is conducted. For the disk section, the results were processed using both the SSED method and the DED method for comparison. The wet modal analysis was subsequently performed using both the analytical method and the AFSI method. The results, presented in Figure 14b, demonstrate that the deviation for the added mass at the disk location is significantly smaller when using the DED method compared to the SSED method. Furthermore, the DED results show excellent agreement with the AFSI benchmarks.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Wet Modal Analysis of a Magnetic Levitation Pump Rotor (Without Impeller)

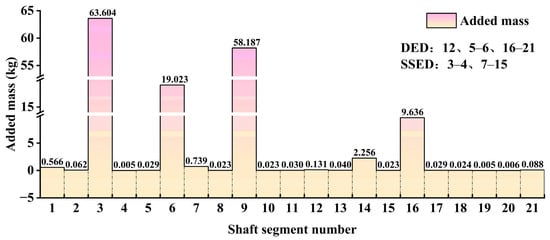

This section focuses on the magnetic levitation pump rotor without impeller. Initially, the wet modal analysis was conducted analytically based on added mass. The rotor was segmented according to the shaft radius and the width of the annular fluid clearance, as detailed in Figure 5. The added mass for each segment was computed based on this segmentation and the applicability conditions of the analytical formula. It was found that only the impeller mounting segment ⑭ satisfied the conditions for applying the analytical formula. For all other segments, the CFD method was employed to determine the added mass, ensuring computational accuracy. The results are shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Added mass results for each shaft segment.

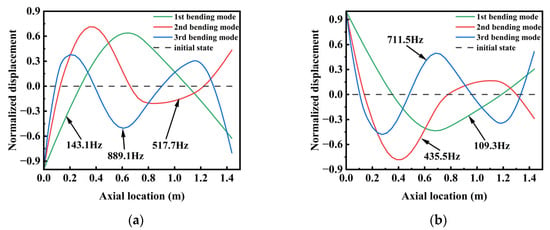

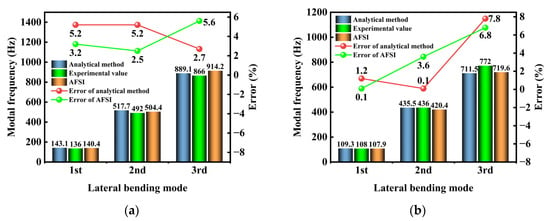

Subsequently, an analytical model of the rotor was developed. The shaft was discretized into segment elements, and all components mounted on the shaft—except for the motor rotor—were treated as lumped mass disks. This distinction arises because the motor rotor, being axially extended relative to the shaft, represents a typical elongated disk component. Simply modeling it as a lumped mass disk would neglect its contribution to the overall structural stiffness, leading to a significant underestimation of the modal frequencies. Therefore, Method 2 was employed, treating the motor rotor as an integral part of the corresponding shaft segment through local thickening. This approach facilitated the determination of the global node distribution, the spatial distribution of lumped masses and moments of inertia, and the added mass distribution across the rotor. Simultaneously, the support stiffness of the magnetic bearings was incorporated. Calculations under static levitation conditions yielded radial stiffness values of 325 N/mm for both the upper and lower radial bearings, and an axial stiffness of 1075 N/mm for the thrust bearing. The analytical modal results obtained through programmed computation are as follows:

- Dry mode: 1st bending = 143.1 Hz; 2nd bending = 517.7 Hz; 3rd bending = 889.1 Hz;

- Wet mode: 1st bending = 109.3 Hz; 2nd bending = 435.5 Hz; 3rd bending = 711.5 Hz.

The corresponding mode shapes are illustrated in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Analytical modal Shapes of the magnetic levitation pump rotor (without impeller) (a) Dry mode; (b) Wet mode.

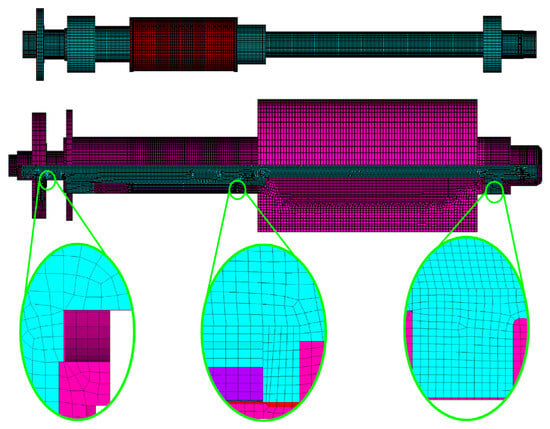

Concurrently, the wet modal analysis of the magnetic levitation pump rotor (without impeller) was performed using the AFSI method. Regarding spatial discretization: the entire rotor was meshed with SOLID185 elements, the fluid domain with FLUID30 elements, and the outer casing with SHELL181 elements. In terms of boundary conditions: the rotor was assigned free boundary conditions, while the outer casing was fully constrained. For contact definitions: standard surface-to-surface contact was defined between the shaft and the upper/lower radial magnetic bearings, as well as the motor rotor, except at welded interfaces where node sharing was applied. Within the motor rotor, node sharing and bonded contacts were employed. Node sharing was employed at the interfaces between the shaft and the upper/lower end caps and the thrust disk. A bonded contact was defined between the lower end cap and the lower radial magnetic bearing. A friction coefficient of Mu = 0.2 was assigned to all contact interfaces. For fluid–structure interaction: FSI and FSIN surfaces were defined at the interfaces between the fluid and the rotor and the fluid and the casing, respectively. As MPC cannot be applied to nodes on FSI surfaces in wet modal analysis, the magnetic bearings were modeled as equivalent multi-point supports. The axial thrust bearing was represented by a four-point support and both the upper and lower radial bearings by three-point supports. A schematic of the discretized finite element model is shown in Figure 19.

Figure 19.

Schematic of the discretized finite element model.

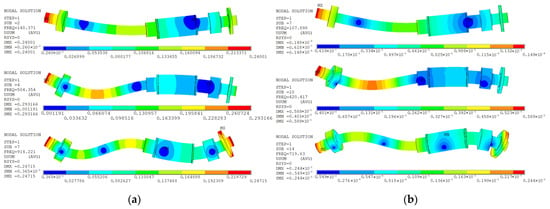

The computed modal simulation results are as follows:

- Dry mode: 1st bending = 140.4 Hz; 2nd bending = 504.4 Hz; 3rd bending = 914.2 Hz;

- Wet mode: 1st bending = 107.9 Hz; 2nd bending = 420.4 Hz; 3rd bending = 719.6 Hz.

The corresponding mode shapes are illustrated in Figure 20.

Figure 20.

AFSI-based modal shapes of the magnetic levitation pump rotor (without impeller) (a) Dry mode; (b) Wet mode.

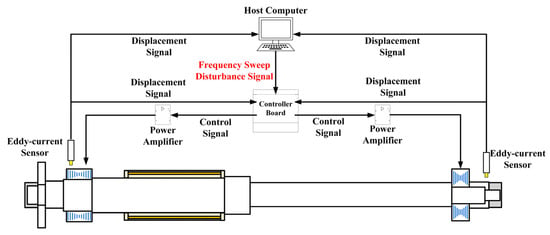

Consequently, experimental modal analysis of the rotor was conducted. For conventional pump rotors supported by mechanical bearings, the utilization of an appropriate external excitation device is imperative. However, for fully assembled centrifugal pump rotors under real wet conditions, performing wet modal testing is often challenging or even impractical. In contrast, magnetic levitation pump systems are able to capitalize on the inherent advantage of magnetic bearings. Under both dry and wet conditions, they require no external excitation device. A swept-frequency excitation signal can be directly applied through the magnetic bearings, and the resulting displacement responses are acquired via integrated displacement sensors, enabling the identification of modal parameters. The schematic diagram of this modal testing via swept-frequency excitation is shown in Figure 21.

Figure 21.

The schematic diagram of modal testing via swept-frequency excitation.

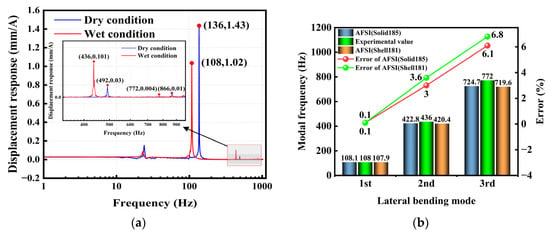

The swept-frequency modal test results are presented in Figure 22a. As shown in Figure 23, the analytical, simulated, and experimental values exhibit close agreement. The maximum deviation observed was 7.8%, which occurred for the third bending mode under wet conditions in the analytical solution; despite this, all results meet the accuracy requirements for engineering applications.

Figure 22.

(a) Modal swept-frequency experiment results; (b) Comparison of modal results under different element discretization types.

Figure 23.

Comparison of experimental modal results; (a) Dry mode; (b) Wet mode.

Furthermore, a solid model of the external pump casing was developed and discretized using SOLID185 elements. An FSI interface was defined at the boundary with the fluid domain, and a wet modal AFSI analysis was conducted. The simulation results were compared with those from a simplified model meshed with SHELL181 shell elements, as well as with experimental data, as illustrated in Figure 22b. The results indicate that both discretization approaches yield consistent predictions for the external pump casing. Therefore, both methods are suitable for rotor wet modal analysis. However, the solid element discretization requires substantially greater computational time, resource consumption, and modeling effort compared to the shell element approach.

4.2. Regularity Analysis of Rotor Wet Mode in Confined Water

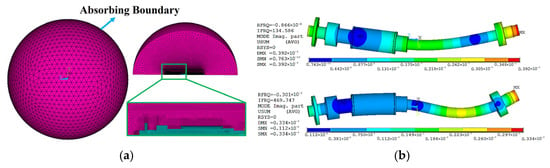

To emphasis the significant influence of confined water on rotor wet mode, this study firstly conducted a wet modal analysis of the rotor under infinite water domain conditions. Equation (15) was used to determine the minimum absorbing boundary radius as 4.4 m; to ensure accuracy, an absorbing boundary radius of 5 m was adopted in this study.

The characteristic dimension, denoted as , is defined as the radius for submerged disks or spherical shells. For the magnetic levitation pump rotor in this study, is taken as half the shaft length. The speed of sound in the fluid is represented by c, and f denotes the dominant frequency of interest.

The absorbing boundary was discretized with FLUID130 acoustic infinite elements. Figure 24 shows the finite element model of the magnetic levitation pump rotor in an unbounded fluid domain and its corresponding first two mode shapes. A comparison of the wet modal frequencies in the infinite domain with both the dry modal frequencies and the wet modal frequencies in the confined domain is summarized in Table 3. The results demonstrate that the wet modal frequencies under both fluid conditions are lower than the dry modal frequencies due to the fluid added-mass effect. Moreover, the wet modal frequencies in the confined domain are considerably lower than those in the infinite domain, indicating a stronger added-mass effect. Thus, regularity analysis into wet modal behavior in confined water is essential.

Figure 24.

(a) Diagram of the finite element model; (b) Diagram of the first two mode shapes for a magnetic levitation pump rotor in an infinite water medium.

Table 3.

Comparison of modal results for the magnetic levitation pump rotor under different water domain conditions.

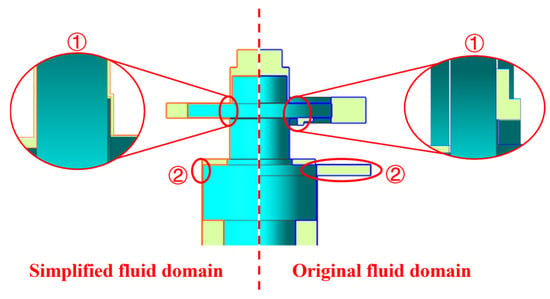

For radial annular fluid clearance, Figure 17 shows that the added mass effect is most significant at four key clearances: the upper radial backup bearing clearance (URBBC), upper radial magnetic bearing clearance (URMBC), motor rotor radial clearance (MRRC), and lower radial magnetic bearing clearance (LRMBC). These four clearances were therefore selected to analyze the influence of radial annular fluid clearance. Additionally, since the thrust disk is supported by a differentially controlled axial magnetic thrust bearing, it features bilateral axial clearances. The effect of axial fluid clearance was also examined, broadly categorized into symmetric (SAMTBC) and asymmetric (AAMTBC) axial magnetic thrust bearing clearances. This classification allows systematic evaluation of how symmetric and asymmetric variations in these clearances affect the wet modal characteristics of the magnetic levitation pump rotor. To facilitate regularity analysis, the original fluid domain was appropriately simplified, with emphasis on the thrust magnetic bearing clearance and the upper radial magnetic bearing clearance. A comparison of the configurations before and after simplification is presented in Figure 25. The computed results are as follows:

Figure 25.

Geometric comparison of original and simplified fluid domain.

- Simplified fluid domain: 1st bending = 107.97 Hz; 2nd bending = 420.15 Hz; 3rd bending = 687.05 Hz.

Compared to the original fluid domain, the wet modal results for the simplified fluid domain show general agreement, except for a certain decrease in the third bending modal frequency. Based on the simplified model, regularity analysis was performed on selected fluid clearance to examine how rotor wet mode vary with clearance size—specifically at 1 times (initial), 3 times, 6 times, 10 times, and 15 times scales.

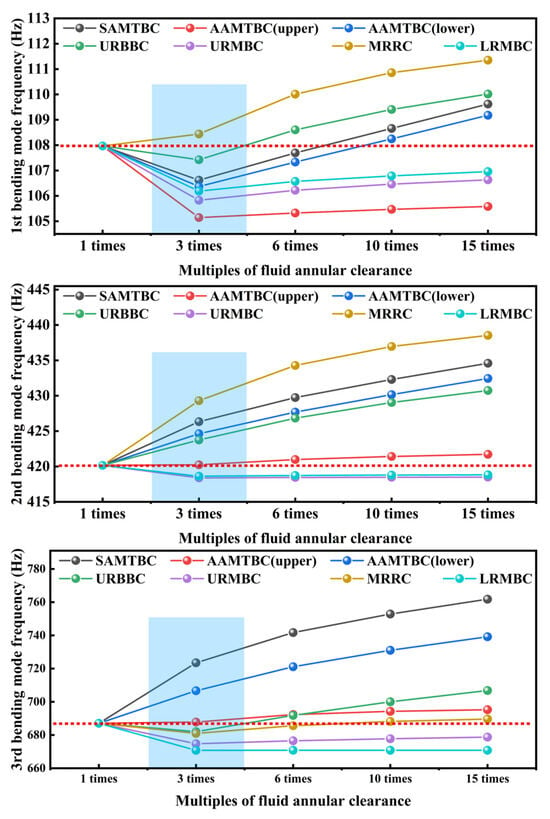

The results, presented in Figure 26, reveal the following:

Figure 26.

Regularity of wet modal in the magnetic levitation pump rotor.

- In general, the first three bending modes exhibit an overall increasing trend with the enlargement of the various fluid clearance. However, the 3 times clearance size serves as a transition point. For certain fluid clearance, a decrease in modal frequency is observed when transitioning from the 1× to the 3× size. Moreover, larger clearance sizes do not invariably yield modal frequencies higher than the initial values.

- The influence of different fluid clearance on modal behavior exhibits modal dependency, spatial specificity, and size difference. This result stems from two factors: differential changes in added mass due to clearance size variation, and the distinct sensitivity of each mode to fluid clearance, governed by mode shape. Therefore, a fluid clearance near a region of minimal modal deformation has negligible effect. For example, modifying the motor rotor radial clearance (MRRC) significantly impacts global added mass, strongly influencing the first and second bending modes, while minimally affecting the third bending mode due to negligible deformation near the MRRC.

- Both symmetric and asymmetric changes in bilateral axial fluid clearance affect all modal orders. Thus, the axial added mass effect should be considered in the analysis of practical submerged rotor systems.

4.3. Wet Modal Analysis of a Magnetic Levitation Pump Rotor (With Impeller)

This section extends the wet modal analysis to the magnetic levitation pump rotor with impeller operating under confined water conditions. Beginning with the analytical approach, the added mass treatment for individual shaft segments remains consistent with the approach outlined in Section 4.1. The key challenge involves determining the fluid-added mass at the impeller. Owing to the geometric complexity of the surrounding fluid, existing analytical formulas are inapplicable, and employing a CFD-based numerical approach to compute the added mass would be prohibitively expensive in terms of computational time and resources. Consequently, the approach introduced by Blevins is employed, wherein the added mass is equated to the sum of the fluid mass within the impeller cavity and that corresponding to the swept volume of the impeller [33]. Table 4 presents the fluid added mass for each stage impeller calculated using the Blevins method, where the fluid density is taken as 1000 kg/m3. For the overall wet modal analytical calculation, five-stage impeller and its corresponding mounting shaft section are treated using Method 2 (treatment as a locally thickened segment of the corresponding shaft section).

Table 4.

Fluid-Added Mass per Impeller Stage, Based on Blevins’ Method.

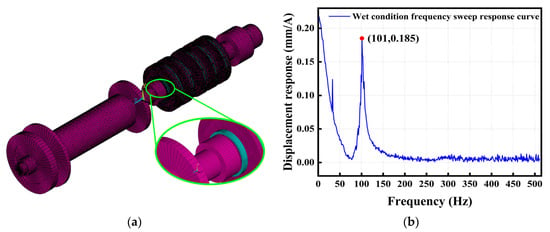

For the AFSI method, the inclusion of components such as the impeller leads to a highly complex internal fluid domain, encompassing fluid regions within the impeller passages, guide vanes, and adjacent front and rear pump chambers. Consequently, fully modeling the entire system—including the magnetic levitation pump rotor, the fluid domain, and the external pump casing—proves not only technically challenging but also computationally prohibitive, warranting appropriate simplifications. Therefore, for the complex fluid region in proximity to the impeller, a truncation approach was adopted at the inlet and outlet sections, where zero-pressure (P = 0) boundary conditions were implemented to simplify the domain. For the external pump casing, a simplified model was constructed using shell elements, with FSIN surfaces defined to capture the fluid–structure interaction interfaces. This approach maintains computational accuracy while circumventing the difficulties associated with modeling the entire system in full detail. A schematic of the finite element model for the AFSI method is shown in Figure 27a, while Figure 27b presents the corresponding swept-frequency experimental modal result.

Figure 27.

(a) Schematic of the finite element model for the AFSI method; (b) Modal swept-frequency experiment results.

The computational results for the first bending mode, the primary mode of interest, indicate a frequency of 96.83 Hz using the analytical method and 104.21 Hz via the AFSI method. A comparison with experimental values reveals deviations of 4.1% and 3.2% for these two wet modal computation methods, respectively. As both errors are within the acceptable threshold of 5%, these results further validate the accuracy of the proposed methodologies for calculating the wet mode of the magnetic levitation pump rotor in confined water.

5. Conclusions

This study addresses the practical challenge of accurately predicting the wet modal characteristics of a novel, fully submerged magnetically levitated integrated rotor under confined water conditions. An improved analytical method for wet modal computation based on added mass correction is proposed and successfully applied to predict the wet modes of two magnetic levitation pump rotors. The analytical results show good agreement with both simulation values from the Acoustic Fluid–Structure Interaction (AFSI) method and experimental data. Furthermore, compared to the AFSI method, the proposed approach not only significantly reduces computation time but also enables batch processing during the early design phase of similar submerged rotors. This substantially enhances rotor design efficiency, allowing for the rapid identification of optimal design directions, and provides a more accurate rotor dynamic model for active magnetic bearing control. Further, this paper evaluates the influence of different fluid clearances on rotor wet modal behavior through regularity analysis, aiming to elucidate the intrinsic mechanisms by which confined water affects the wet modes of magnetic levitation pump rotors. The main conclusions of this research are as follows:

- (1)

- When accounting for actual fluid viscosity, the analytical formula produces significant overestimation errors in the added mass for confined annular fluid domains featuring narrow clearances or for cylindrical structures with low aspect ratios. Under these conditions, correction through a CFD-based approach becomes necessary. Nevertheless, for large fluid clearance, the analytical formula remains applicable provided that the aspect ratio satisfies L/d ≥ 5.

- (2)

- Following validation of the thickening treatment for elongated disk components and the disk equivalent density (DED) method, the proposed improved analytical method for wet modal analysis—based on added mass effects—was successfully verified. Wet modal analysis was conducted on two types of magnetic levitation pump rotors using both analytical and the AFSI method. The results, compared against experimental data from swept-frequency modal tests, demonstrate good agreement with measured values. For the first bending mode—the primary mode of interest—the maximum observed error was 4.1%, thereby validating the accuracy of both computational methods in predicting the wet modal behavior of the rotor.

- (3)

- Relative to infinite or extensive open water domains, confined water markedly amplifies its influence on the wet mode of the rotor.

- (4)

- The modal frequencies generally exhibit an increasing trend with the enlargement of the fluid clearance. A fluid clearance size of three times the original serves as a transition point. However, increasing the fluid clearance size does not invariably result in modal frequencies higher than their initial values. And the sensitivity to such variations differs across modal orders, depending chiefly on the mode shape and the location of fluid clearance. Additionally, changes in the axial fluid clearance also exert a discernible influence on all modal orders.

Due to the inability of traditional analytical formulas to meet the requirement for precise added mass calculation in the improved wet modal analytical method, the computationally intensive CFD approach remains necessary for determining the added mass of submerged rotor structures. Consequently, how to rapidly obtain the added mass of submerged rotor structures based on boundary conditions and establish analytical calculation formulas with broader applicability will be an important direction for future research on the analytical and optimal design of submerged rotors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.F.; Methodology, S.F., G.C. and Y.W.; Software, S.F. and Y.W.; Writing—original draft, S.F.; Writing—review and editing, Y.W.; Visualization, G.C.; Resources, Q.L. and X.W.; Data curation, Q.L.; Supervision, X.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52201362, No. 52425701, No. 52477046).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| added mass | |

| E | elastic modulus |

| inner and outer diameters of the confined water | |

| r | radius |

| drag force acting on the object when moving at the initial velocity v0 | |

| mass per unit length of the shaft segment | |

| mean fluid density | |

| dynamic viscosity | |

| density of fluid medium | |

| inner to outer diameter ratio | |

| rotational angular velocity | |

| a | acceleration |

| total force exerted on the object during uniform deceleration to velocity v0 | |

| c | speed of sound in the fluid medium |

| K | fluid bulk modulus |

| l | length of the shaft segment element |

| I | cross-sectional moment of inertia |

| AFSI | Acoustic Fluid–Structure Interaction |

| SSED | shaft segment equivalent density method |

| DED | disk equivalent density method |

| SAMTBC | symmetric axial magnetic thrust bearing clearances |

| MRRC | motor rotor radial clearance |

| URBBC | upper radial backup bearing clearance |

| URMBC | upper radial magnetic bearing clearance |

| LRMBC | lower radial magnetic bearing clearance |

| AAMTBC | asymmetric axial magnetic thrust bearing clearances |

References

- Wu, Y.; Wu, D.; Fei, M.; Sørensen, H.; Ren, Y.; Mou, J. Application of GA-BPNN on Estimating the Flow Rate of a Centrifugal Pump. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 119, 105738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Pei, J.; Wang, W.; Gan, X. Blade Redesign Based on Inverse Design Method for Energy Performance Improvement and Hydro-Induced Vibration Suppression of a Multi-Stage Centrifugal Pump. Energy 2024, 308, 132862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Luo, J.; Liu, S.; Han, Z.; Ni, X. Hydraulic Optimization Design of Centrifugal Pumps Aiming at Low Vibration Noise. AIP Adv. 2022, 12, 95026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Wang, K.; Liu, H.; Cheng, Z. Influence of Shaft Combined Misalignment on Vibration and Noise Characteristics in a Marine Centrifugal Pump. J. Low Freq. Noise Vibr. Act. Control 2022, 41, 1286–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Liu, X.; Zeng, Y.; Zhu, B.; Hu, B.; Hua, H. Investigation of the Noise Induced by Unstable Flow in a Centrifugal Pump. Energies 2020, 13, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani Dehkharqani, A.; Cervantes, M.J.; Aidanpää, J.-O. Numerical Analysis of Fluid-Added Parameters for the Torsional Vibration of a Kaplan Turbine Model Runner. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2017, 9, 168781401773289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigrist, J.-F.; Broc, D.; Lainé, C. Dynamic Analysis of a Nuclear Reactor with Fluid–Structure Interaction. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2006, 236, 2431–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münch, C.; Ausoni, P.; Braun, O.; Farhat, M.; Avellan, F. Fluid–Structure Coupling for an Oscillating Hydrofoil. J. Fluids Struct. 2010, 26, 1018–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, C.G.; Egusquiza, E.; Escaler, X.; Liang, Q.W.; Avellan, F. Experimental Investigation of Added Mass Effects on a Francis Turbine Runner in Still Water. J. Fluids Struct. 2006, 22, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Buat, P.L.G. Principes D’hydraulique: Vérifiés Par Un Grand Nombre d’expériences Faites Par Ordre Du Gouvernement; Ouvrage Dans Lequel on Traite Du Mouvement Uniforme & Varié de l’eau Dans Les Rivières, Les Canaux, & Les Tayaux de Conduite; Imprimerie de Monsieur: Paris, France, 1786; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sarpkaya, T.; Garrison, C.J. Vortex Formation and Resistance in Unsteady Flow. J. Appl. Mech. 1963, 30, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarpkaya, T. Lift, Drag, and Added-Mass Coefficients for a Circular Cylinder Immersed in a Time-Dependent Flow. J. Appl. Mech. 1963, 30, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.S.; Wambsganss, M.W.; Jendrzejczyk, J.A. Added Mass and Damping of a Vibrating Rod in Confined Viscous Fluids. Am. Soc. Mech. Eng. 1976, 43, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaggio, P. The Added Mass of a Deformable Cylinder Moving in a Liquid. Contin. Mech. Thermodyn. 1996, 8, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, S.; Nakamura, T.; Inada, F.; Kato, M.; Ishihara, K.; Nishihara, T.; Mureithi, N.W.; Langthje, M.A. Flow-Induced Vibrations: Classifications and Lessons from Practical Experiences, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lagrange, R.; Puscas, M.A.; Piteau, P.; Delaune, X.; Antunes, J. Modal Added-Mass Matrix of an Elongated Flexible Cylinder Immersed in a Narrow Annular Fluid, Considering Various Boundary Conditions. New Theoretical Results and Numerical Validation. J. Fluids Struct. 2022, 114, 103754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fackrell, S. Study of the Added Mass of Cylinders and Spheres; University of Windsor: Windsor, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Javanmard, E.; Mansoorzadeh, S.; Mehr, J.A. A New CFD Method for Determination of Translational Added Mass Coefficients of an Underwater Vehicle. Ocean Eng. 2020, 215, 107857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xiao, S.; Wang, X.; Qi, D. Numerical Simulation and Analysis of Added Mass for the Underwater Variable Speed Motion of Small Objects. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannoura, A.A. Numerical and Experimental Modelling of Unsteady Flow in Rockfill Embankments. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Windsor, Windsor, ON, Canada, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Hannoura, A.A.; McCorquodale, J.A. Rubble Mounds: Hydraulic Conductivity Equation. J. Waterw. Port Coastal Ocean Eng. 1985, 111, 783–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noca, F. On the Evaluation of Time-Dependent Fluid-Dynamic Forces on Bluff Bodies; California Institute of Technology: Pasadena, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Noca, F.; Shiels, D.; Jeon, D. Measuring Instantaneous Fluid Dynamic Forces on Bodies, Using Only Velocity Fields and Their Derivatives. J. Fluids Struct. 1997, 11, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Dynamics Modeling and Modal Analysis for the Rotor in Water Medium. Master’s Thesis, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, Q. Numerical Investigation of the Added Mass Effect of Submerged Blade Disk Structures: From Simplified Models to Francis Turbine Runners. Alexandria Eng. J. 2022, 61, 3013–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.; Zhang, Z.; Bai, L. Wet Modal Analyses of Various Length Coaxial Sump Pump Rotors with Acoustic-solid Coupling. Shock Vib. 2021, 2021, 8823150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Wang, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z. Study on the Influence of Gap Water Body on the Modal Characteristics of Pump Turbine Runner. In Proceedings of the 2021 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Advanced Manufacture (AIAM), Manchester, UK, 23–25 October 2021; pp. 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Yu, S.; Wang, Z. Modal Characteristics Analysis of a Variable-Speed Pump-Turbine Rotor System: A Perspective of Resonance. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2854, 12084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Luo, Y.; Presas, A.; Ahn, S.-H.; Wang, Z.; Huang, X.; Liu, Y. Influence of Rotation on the Modal Characteristics of a Bulb Turbine Unit Rotor. Renew. Energy 2022, 187, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Luo, Y.; Liu, X.; Presas, A.; Deng, L.; Zhao, W.; Xia, M.; Wang, Z. Numerical Theory and Method on the Modal Behavior of a Pump-Turbine Rotor System Considering Gyro-Effect and Added Mass Effect. J. Energy Storage 2024, 85, 111064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Luo, Y.; Shi, Y.; Liu, X.; Xu, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhai, L.; Wang, Z. A Review of Hydro-Turbine Unit Rotor System Dynamic Behavior: Multi-Field Coupling of a Three-Dimensional Model. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 121304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Rotor Dynamics; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Gamarra, J. Effect of Component Interference Fit and Fluid Density on the Lateral and Torsional Natural Frequencies of Turbomachinery Rotor Systems. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth Pump Symposium, Houston, TX, USA, 30 September–3 October 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).