Abstract

The rectangular truss aquaculture cage platform is considered the main solution for modern deep-sea aquaculture equipment in the future due to its excellent wind and wave resistance, as well as its mechanization and automation capabilities. The underwater noise generated during the application of large-scale aquaculture platforms is an important basis for evaluating their impact on the underwater acoustic environment and developing intelligent aquaculture in the future. This article conducts experimental research on the rectangular truss aquaculture net cage platform “HENGYI 1” and conducts noise measurement and analysis based on the characteristics of the aquaculture platform’s operating sea area, operating process, and equipment configuration. Research has shown that the overall underwater noise of the aquaculture net cage platform is mainly distributed in the mid to low frequency range below 1000 Hz. Compared to the two sides of the platform, the underwater noise in the platform net cage is less affected by tides, and the intensity of underwater noise on the left and right sides of the net cage alternates with tides. Diesel generators are the main source of noise in truss-style aquaculture cages. When the generator is in operation, the peak power spectral density level of the noise is around 25 Hz. The results of the article can provide a reference for the study of noise in offshore aquaculture platforms.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of modern socio-economy, human consumption of various resources has increased significantly, leading to severe encroachment on mariculture space by other industries. Issues such as excessive mariculture density, environmental degradation, and frequent disease outbreaks have become increasingly prominent [1,2,3,4]. The drawbacks of traditional mariculture methods have gradually become apparent, making it increasingly difficult to meet the current sustainable development needs of humanity [5,6]. To mitigate the impact of aquaculture on coastal areas, expand farming space, and achieve sustainable development of the mariculture industry, the advancement of deep-sea aquaculture is imperative [7,8,9]. Deep-sea aquaculture employs advanced farming technologies and equipment tailored to the characteristics of cultured species and marine conditions, making full use of high-quality seawater resources in deep-sea areas [10]. While protecting the marine environment, it addresses the challenges of long-term survival in deep-sea conditions, effectively expanding the space for marine fishery aquaculture [11,12].

With the continuous commissioning of large-scale intelligent aquaculture platforms, while providing new space for aquaculture, they also introduce new anthropogenic underwater noise, which may adversely affect surrounding marine life and farmed fish through interference with biological communication, altered behavioral patterns, auditory damage, or stress responses [13,14]. Simultaneously, numerous acoustic technologies are increasingly being applied in intelligent aquaculture, such as using acoustic methods to monitor fish escape behavior, feeding activities, and biomass estimation [15,16,17,18]. The application of these technologies requires consideration of acoustic compatibility issues with the platforms [19,20]. Therefore, conducting underwater noise measurement and research on large-scale deep-sea aquaculture platforms is of significant importance. Currently, the assessment of underwater noise impacts generated during platform operation remains notably insufficient worldwide, primarily due to the lack of operational noise measurement data monitoring. This paper focuses on experimental research regarding the measurement and analysis of aquaculture platform noise, aiming to study the fundamental characteristics and patterns of underwater noise during platform operation. Understanding the basic principles and features of aquaculture platform noise can, based on these research findings, contribute to future platform precision farming, ecological effect monitoring, and adaptive platform modifications, thereby promoting the economic viability, safety, and environmental friendliness of deep-sea aquaculture.

2. Measurement Experimental Scheme

2.1. Analysis of Aquaculture Cage Noise Sources

Aquaculture platforms can be structurally categorized into two types [21,22]. The first type is open-net cages, which are typically deployed at fixed locations in predetermined sea areas for cultivation. The second type is closed aquaculture vessels, which operate by cruising to identify optimal farming zones. Comparatively, aquaculture vessels offer greater flexibility and can effectively mitigate disease risks. However, their construction costs are higher, and currently, the number of operational aquaculture vessels remains limited. Open-net cages, with their cost-effectiveness, still dominate the aquaculture platform market. Among these, rectangular truss-type aquaculture cages are regarded as a primary solution for future modernized deep-sea farming equipment due to their superior wave resistance and automation capabilities [23,24]. Rectangular truss-type cage platforms have been widely deployed and are considered representative and typical of standard designs, making them suitable subjects for this study. Given existing conditions, in this paper, the operational rectangular truss-type aquaculture platform “HENGYI 1” in the waters administered by Zhanjiang City, Guangdong Province, China, is selected as a case study. The research encompasses a detailed investigation of potential noise sources on the platform, followed by underwater noise measurements to analyze its acoustic characteristics.

Figure 1 shows an aerial view of “HENGYI 1” aquaculture cage; “HENGYI 1” is a rectangular truss-type aquaculture platform designed and developed by Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhanjiang). With an aquaculture water volume of 60,000 m3, it is located approximately 10 km offshore southwest of Donghai Island in Zhanjiang. The platform measures 101 m in length, 47.5 m in width, and 27.5 m in total height, situated in waters with a depth of about 24–30 m and designed for an aquaculture draft of 15 m. The platform is divided into six aquaculture zones, where Seriola dumerili (The commonly known names: amberjack) and Trachinotus ovatus (The commonly known names: pompano) are co-cultured. The superstructure of the platform is arranged overhead. It is equipped with photovoltaic power generation facilities to meet the daily electricity demands of aquaculture operations and personnel living, while also featuring a shipboard diesel generator for backup power supply.

Figure 1.

“HENGYI 1” Aquaculture Cage.

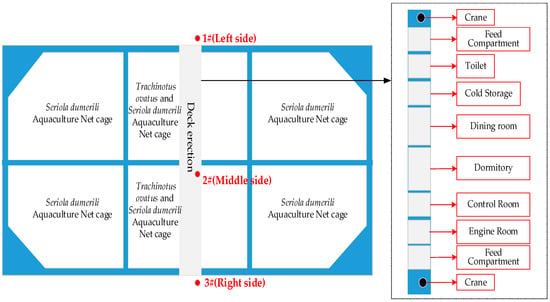

The potential noise sources of aquaculture platforms can be primarily categorized into two types: mechanical noise generated by platform equipment operation and biological noise produced by fish activities on the platform. Figure 2 is a plan view of the platform, from which it can be seen that the main mechanical equipment of the platform is concentrated in the upper structure of the central deck of the platform. Among the mechanical noise sources of aquaculture platforms, diesel generators contribute most significantly to underwater noise. While photovoltaic power generation typically meets platform operational demands during summer with sufficient sunlight, diesel generators frequently operate in winter and spring due to overcast and rainy weather, becoming the primary source of underwater noise from the platform. During operation, other noise sources on the platform have relatively minor impacts on the underwater environment. Noise generated by personnel working and living on the platform (including related mechanical noise) is relatively low in intensity and mostly occurs intermittently for short durations. Cranes, being electrically driven equipment, also produce relatively low noise and are not in constant operation, resulting in limited impact. Intelligent feeding equipment is expected to generate some underwater noise during operation, but since such devices are closely tied to fish feed applications and are currently rarely deployed on platforms, they are not considered here. In current aquaculture practices, frozen trash fish serve as the primary feed source, necessitating continuous operation of refrigeration compressors. However, the noise generated by these compressors is comparatively lower than that of diesel generators. In summary, although the aquaculture platform has multiple sources of mechanical noise, most of the noise is intermittent and has minimal environmental impact. Therefore, this study will primarily focus on the noise impact of diesel generator sets [25,26,27,28].

Figure 2.

The plan view of “HENGYI 1” Aquaculture Cage Platform.

In terms of biological noise, the primary focus is on the physiological sounds produced by farmed fish populations and the noise generated by their group activities. Due to the large population scale of farmed fish species, current research coverage on their acoustic characteristics remains relatively limited. Fish species currently known to exhibit significant sound-producing characteristics include those from the Sciaenidae, Gadidae, and Lutjanidae families. For example, the acoustic signals of Trachinotus ovatus span a frequency range of approximately 100–1500 Hz with a peak sound pressure level of about 96 dB, while groupers produce sounds within a frequency range of roughly 50–500 Hz and a peak sound pressure level of around 80 dB. For other fish species reared in aquaculture platforms, no relevant studies on their sound production have been reported to date [29,30,31]. Additionally, during group behaviors such as feeding or stress responses, fish may generate certain noise by splashing water, with Seriola dumerili demonstrating particularly notable performance in this regard.

2.2. Experimental Arrangement

Based on the comprehensive investigation results of noise sources, platform structure, standards and specifications, and marine environmental conditions, the test scheme was designed [32]. As shown in Table 1, the measurement system consists of equipment such as sound level meter, self-contained hydrophones, accelerometers, tide meter and current meter. The tests involved measuring the airborne noise on the aquaculture platform deck using a sound level meter; underwater noise from the aquaculture platform using self-contained hydrophones; vibration noise by deploying accelerometers on the surface of the generator in the engine room and the outer bulkhead of the central deck; real-time monitoring of tidal level changes in the test sea area using a tide meter; and monitoring of flow velocity using a current meter.

Table 1.

The type of instruments used for the measurements.

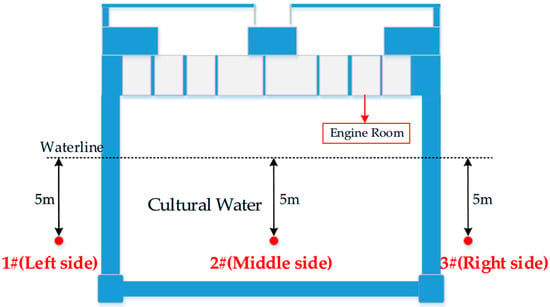

The cage culture chamber contains multiple bottom nets that obstruct the deployment of hydrophones along the depth. Under the coupling effect of ocean currents and structures, complex flow fields such as turbulence and vortices are prone to form at the longitudinal ends of the platform, posing a risk of entanglement with the netting. Taking these factors into account, the side mid-columns on both external sides of the platform were chosen as monitoring locations for this experiment. These columns are directly connected to the platform’s superstructure, where the main noise sources are concentrated. This area represents a critical and sensitive location for underwater noise from the platform, capable of reflecting the platform’s underwater noise conditions to the greatest extent. Additionally, a hydrophone was deployed within the aquaculture cage to monitor internal noise variations. Figure 3 is a schematic diagram of the deployment of underwater noise measurement hydrophones. All three measurement point hydrophones were positioned at a depth of 5 m underwater. Due to the asymmetric arrangement of platform noise sources, this measurement setup also allows for exploring the influence of noise source locations. During the experiment, environmental background noise measurements were also required. Based on acoustic signal attenuation estimates under shallow-sea conditions and relevant measurement experience, a location approximately 1500 m from the platform center was selected as the background noise measurement point.

Figure 3.

Underwater noise measurement hydrophone deployment schematic.

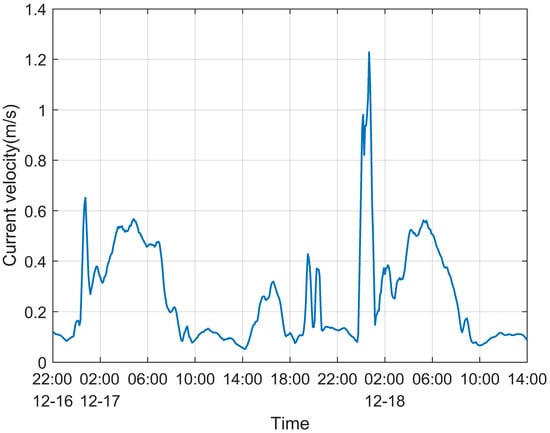

As shown in Table 2, the measurement will start at 22:00 on 16 December 2024 and end at 14:00 on 18 December 2024. During the experiment, the sea condition was at level 2. To clearly analyze the influence of external excitation on noise signals during the measurement process, events that may affect the noise signals during noise measurement are tracked and recorded (Figure 4).

Table 2.

Key Event Log of Measurement Process.

Figure 4.

Flow current variation curve during the experiment.

2.3. Experimental Data Processing

Underwater noise has the characteristics of random signals, and short-time Fourier transform (STFT) is commonly used for frequency domain data analysis of underwater noise, which can comprehensively analyze the time-frequency characteristics of signals. The definition of short-time Fourier transform for discrete signals is as follows [33]:

where is the input signal sequence, is the sliding window function, and N is the window length.

In acoustics, it is necessary to perform 1/3 octave band frequency spectrum analysis to obtain the corresponding 1/3 octave band sound pressure level .

In Equation (2), represents 1/3 octave band bandwidth sound pressure. represents the sound pressure at 1 m from the center of the equivalent sound source, and represents the reference sound pressure, usually taken as 1 μPa in water, and 20 μPa in air.

The noise power spectral density level (PSD) is:

where i is the serial number of the 1/3 oct, n is the number of 1/3 octs within the specified frequency band, is the center frequency of the first 1/3 oct, and represents the effective bandwidth of bandpass filter.

After determining the frequency range, the broadband sound pressure level, which is the total sound level, can be calculated based on the sound pressure levels of each 1/3 octave band. Specifically, the formula for calculating the broadband sound pressure level of a specified frequency band from the 1/3 oct band sound pressure level (SPL) is:

3. Analysis of Experimental Results

3.1. Underwater Noise Characteristics

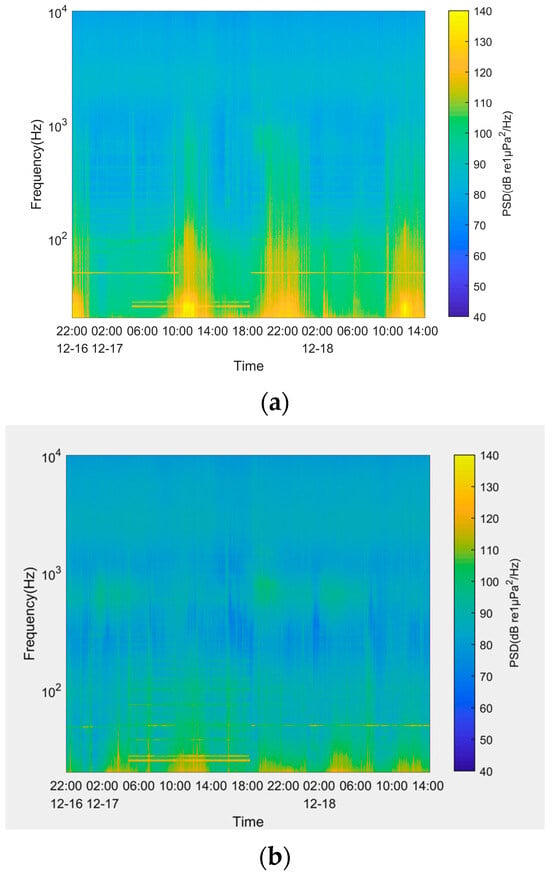

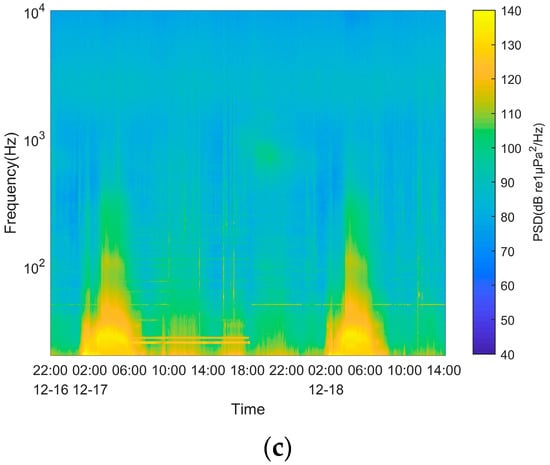

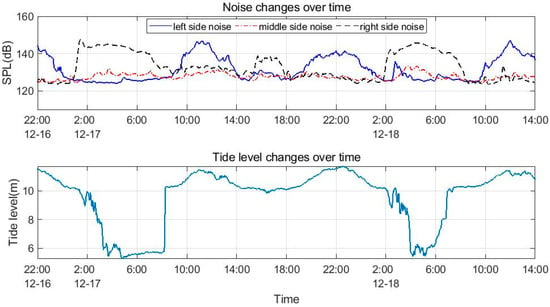

The data collected from hydrophones #1, #2, and #3 located on the left, inside, and right sides of the aquaculture net cage were processed, and the results are shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6. Figure 5 shows the PSD plot of underwater noise, and Figure 6 shows the variation in total underwater noise pressure level and tidal level over time. It can be seen that:

Figure 5.

Underwater noise PSD diagram of aquaculture platform: (a) Left side noise; (b) Middle side noise; (c) Right side noise.

Figure 6.

Underwater noise and tidal level variations in aquaculture platforms over time.

- From 4:50 to 18:10 on 17 December, the generators of the aquaculture platform operated continuously, during which spectral lines were observed around 25 Hz in the noise;

- Inside the net cages of the aquaculture platform, noise may be less affected by tides and diurnal cycles compared to the outer areas, possibly due to the platform’s structural influence;

- The aquaculture platform is fixed at the bottom by pile foundations and connected as a whole at the top through truss structures, causing the noise intensity on both sides to alternate with tidal changes. Specifically, during low tide, the noise intensity on the left side of the platform is significantly higher than on the right side, and during high tide, the noise intensity on the right side of the platform is significantly higher than on the left side.

To identify the main noise sources of the aquaculture platform and analyze the variations in underwater noise under different working conditions, data from hydrophone #2 inside the aquaculture platform cage were selected. A comparative analysis was conducted on the changes in underwater noise before and after the events recorded in Table 1, including crane operation, compressor operation, and generator operation. This article uses the Welch method to process the data and obtain the PSD of the noise signal. The data were processed with a Hanning window and underwater noise signal length is 180 s, NFFT point count is 65,536, and overlap rate is 50%.

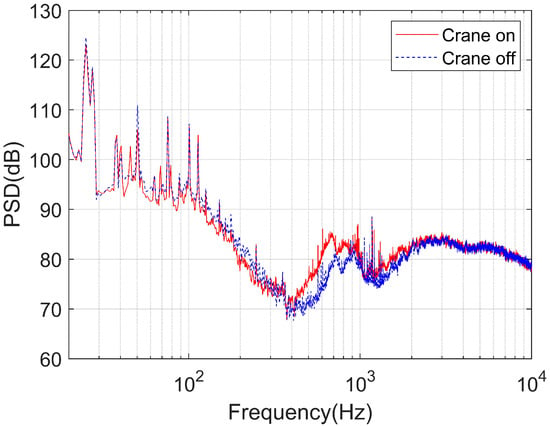

We selected hydrophone data from 15:25–15:28 on 17 December and 15:31–15:38 on 17 December as the underwater noise data before and after the platform crane operation. Figure 7 shows the comparison of underwater noise from the aquaculture platform before and after crane activation. As can be seen from the figure, there was no significant change in underwater noise during crane operation on the aquaculture platform.

Figure 7.

Comparison of underwater platform noise before and after crane operation.

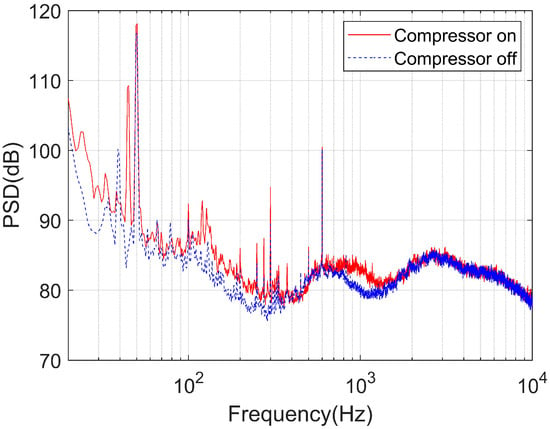

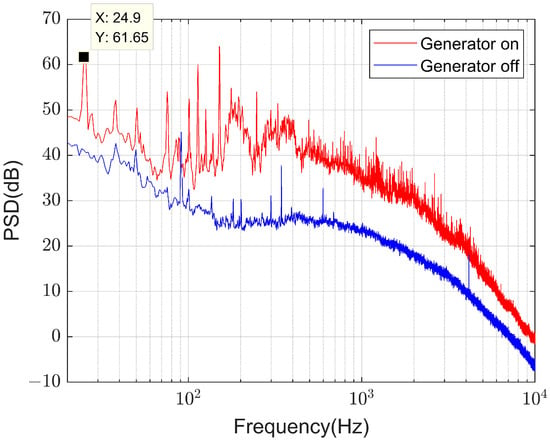

We selected hydrophone data from 06:55–06:58 on 18 December and 07:03–07:06 on 18 December as the underwater noise data before and after the platform crane operation. Figure 8 shows the changes in underwater noise levels of the platform before and after activating the cold storage compressor. From the figure, it can be seen that when the cold storage compressor is running, the underwater noise level in the aquaculture net cage changes relatively little. Significant differences were observed below 50 Hz. In addition, a difference of approximately 5 decibels can be observed within the range of 100 to 300 Hz.

Figure 8.

Comparison of underwater platform noise before and after compressor activation.

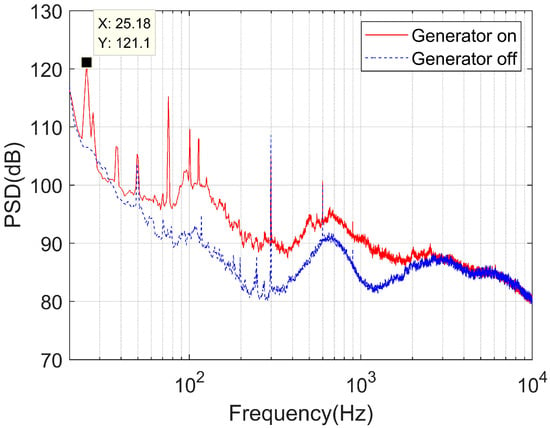

We selected hydrophone data from 04:45–04:48 on 17 December and 04:53–04:56 on 17 December as the underwater noise data before and after the platform generator operation. Figure 9 shows the comparison of underwater noise from the aquaculture platform before and after the generator is turned on. It can be observed that when the generator is operating, multiple line spectra are formed at frequencies below 200 Hz. The peak power spectral density level occurs around 25 Hz, which aligns with the time-frequency analysis results shown in Figure 4. Additionally, the mid-frequency spectrum level below 1000 Hz significantly increases, with an overall rise of approximately 10 dB in the 90–300 Hz range. The influence of the generator on the sound levels over 2000 Hz is relatively minor.

Figure 9.

Comparison of underwater platform noise before and after generator activation.

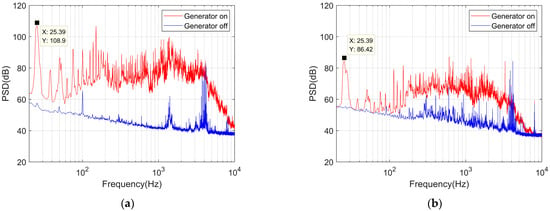

The accelerometer is distributed on the surface of the diesel generator and on the outer bulkhead of the first deck of the upper structure in the center of the platform, and the sound level meter is also placed on the upper deck in the center of the platform. We selected vibration data and air noise data at the same time during the generator working phase. A comparison of vibration noise and airborne noise before and after the generator operation is shown in Figure 10 and Figure 11. As can be seen from the figures, when the generator on the aquaculture platform is turned on, the vibration amplitude of the generator significantly increases, with its dominant frequency around 25 Hz. The generator’s vibration drives the entire platform structure to vibrate together. When the structural vibration propagates to the central deck of the platform, the spectral level of its 25 Hz dominant frequency vibration decreases by approximately 30 dB. During generator operation, the peak spectral level of airborne noise above the platform deck also occurs around 25 Hz.

Figure 10.

Changes in vibration before and after generator startup: (a) Generator surface vibration; (b) Platform central deck vibration.

Figure 11.

Changes in air noise before and after generator activation.

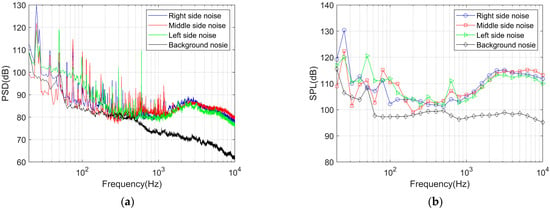

We selected four hydrophones data from 08:00–08:03 on 17 December as the underwater noise data at different positions of the aquaculture platform. Figure 12 shows the comparison of underwater noise at different positions of the aquaculture platform during generator operation. It can be observed that the overall underwater noise of the aquaculture platform is 10 dB higher than the background noise, with multiple spectral lines present in the mid-to-low frequency range below 500 Hz. Among different positions on the platform, the underwater noise intensity is highest on the right side, followed by inside the platform net cage, while the noise level on the left side of the platform is slightly lower than that inside the net cage. The higher noise level on the right side of the aquaculture platform may be attributed to the main noise source—the generator—being located in this area, causing significant structural vibration due to the operation of mechanical equipment such as the generator.

Figure 12.

The comparison of underwater noise at different positions of the aquaculture platform: (a) Noise power spectral density level; (b) 1/3 Octave Band Sound Pressure Level.

Reference [34] provides a formula for calculating sound transmission loss (TL) in shallow waters with a water depth of less than 100 m:

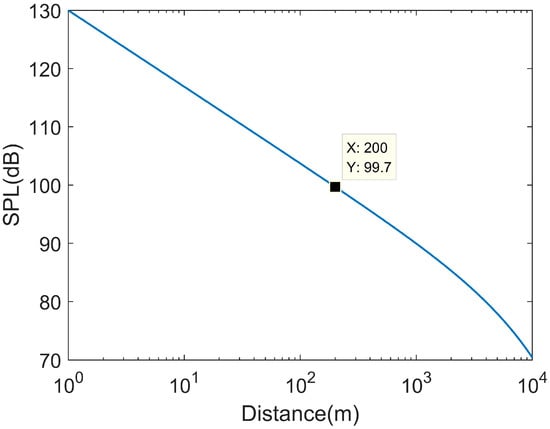

where r is sound propagation distance, Unit: km; f is noise frequency, Unit: kHz; Because the peak spectral level of underwater noise from the aquaculture platform is around 25 Hz and the main noise source being diesel generators, this study presents the attenuation curve of underwater noise transmission during the operation of the generator on the platform. As shown in Figure 13, the underwater noise of the platform generator attenuates to approximately 100 dB at 200 m and 70 dB at 10 km when the generator is working.

Figure 13.

The underwater noise attenuation curve of aquaculture platform.

3.2. Noise Impact on Fish

Based on the noise measurement results, it is necessary to further analyze the impact of noise on farmed fish. Due to limitations in equipment and technical conditions, this paper primarily conducts a preliminary assessment by combining observations on the platform, aquaculture experience, and existing research.

During this experiment, the fish school consistently maintained a quiet swimming state underwater, with no significant fish activity observed near the water surface before or after the generator was turned on. Preliminary research results indicate that neither the “HENGYI 1” platform nor surrounding platforms (such as “HAIWEI 1” and “HAIWEI 2”) exhibited observable significant changes in fish behavior due to generator operation. Notably, the “Haiwei” series aquaculture platforms even cultured Miichthys miiuy from the Sciaenidae family, a noise-sensitive species. In these aquaculture practices, no significant adverse effects (such as stress or mortality) caused by generators on farmed fish were observed.

Currently, the academic community has conducted some research on the impact of noise on fish, Zeddies and Faydemonstrated that goldfish (Carassius auratus) exhibit frequency-dependent hearing threshold shifts: exposure to a 100 Hz tone produced greater threshold shifts at lower frequencies, whereas 2000 Hz and 4000 Hz tones primarily affected higher-frequency sensitivity [35]. Winberg et al. showed that Salmonids display a startle response when subjected to very low-frequency noise (>10 Hz) at only 10–15 dB re 1 μPa, while higher-frequency stimuli failed to elicit such reactions [36]. In golden rabbitfish (Siganus guttatus), Zhang et al. found that prolonged 100–200 Hz noise exposure prompted consistent avoidance behavior, with the most pronounced increases in swimming speed and acceleration occurring at 200 Hz [37]. but there are relatively few studies specifically focused on Seriola dumerili and Trachinotus ovatus. Existing research indicates that the frequency range of vocal signals in Trachinotus ovatus is approximately 100–1500 Hz, and their juveniles exhibit certain conditioned reflexes to sound sources at 110–130 dB, showing adaptation to introduced sound sources [38]. Meanwhile, Seriola dumerili is a species that has only recently begun to be cultivated and promoted, with limited accumulated research. Related practices, such as acoustic conditioning, have been applied to the similar species Seriola quinqueradiata, but no studies have yet reported on its acoustic responses. Given this, the introduction of noise sources in aquaculture platforms may influence their behavior (e.g., swimming patterns, feeding behavior, etc.). However, under long-term farming conditions, the fish population may also adapt to the noise environment, resulting in no observable behavioral changes. This hypothesis requires further confirmation in future studies.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that the diesel generator is the primary noise source for the truss-type aquaculture cage platform. When the generator is operational, the main affected frequency range falls within the mid-low frequency band around 1000 Hz, with its peak spectral line occurring at approximately 25 Hz. The noise characteristics in both time and frequency domains exhibit variations at symmetrically measured positions on the platform. These discrepancies are closely related to the platform’s structural design and the asymmetric arrangement of noise sources, necessitating further in-depth analysis of noise propagation paths in subsequent research. Due to experimental constraints, underwater noise characteristics under various conditions such as feeding and fish activity remain incompletely covered. These issues urgently require more comprehensive experimental investigations in follow-up studies to achieve deeper understanding.

This paper analyzes and evaluates the response of fish under platform noise conditions. Based on field observations on the platform, aquaculture experience, and relevant research findings, it is preliminarily concluded that anthropogenic noise generated by the platform does not cause significant adverse effects on farmed fish, though it may potentially alter their behavioral patterns. In this paper, the behavior of fish is mainly evaluated through visual observation. There are certain limitations and uncertainties associated with this observation method. Given the vast diversity of fish species (approximately 32,000), there exists considerable specificity in auditory physiological structures and adaptability to environmental noise [39]. During experiments, limitations in underwater optical and acoustic sensing technologies made it difficult to achieve comprehensive observation of fish school behavior or establish an ideal experimental environment. These challenges also hindered in-depth analysis of the results presented in this study. Future breakthroughs in intelligent sensing technologies for fish will enable better monitoring of noise impacts on farmed fish, thereby further supporting precision aquaculture practices.

Through this research project, a preliminary exploration has been conducted on the main noise characteristics of rectangular truss-type aquaculture cages. Based on the noise spectrum of the platform, the impact of related intelligent equipment on fish monitoring can be assessed. In certain fish farming practices, particularly for species in the Sciaenidae family, which are highly sensitive to sound, further studies are needed on how to mitigate adverse noise effects while utilizing acoustic methods to control fish behavior. This requires integrating the underwater noise characteristics of the platform to advance research and development efforts in platform vibration and noise reduction, as well as acoustic control equipment for fish schools.

5. Conclusions

This paper systematically investigates the potential noise sources of typical rectangular truss-type aquaculture platforms and conducts preliminary measurements of their underwater noise characteristics. The main conclusions are as follows:

Rectangular truss-type aquaculture platforms have multiple noise sources, including power equipment, refrigeration compressors, feeding devices, fish vocalizations, and fish movement. Among these, diesel generators are the primary noise source for truss-type aquaculture platforms, while the impact of other equipment is relatively minor. When the generator is operational, its vibrations are transmitted underwater through the steel structure of the cage, resulting in a peak noise power spectral density level around 25 Hz.

Due to the influence of the platform structure, the underwater noise inside the aquaculture platform cages is less affected by tidal changes compared to the exterior of the platform. The bottom of the aquaculture platform is fixed with pile foundations, while the top is connected as a whole through a truss structure, causing the noise intensity on both sides of the platform to alternate with the tidal cycle.

Author Contributions

Y.X.: conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, visualization and software; Y.D.: conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, visualization and software; X.C.: methodology, writing—original draft preparation, data curation, validation, supervision; W.L.: writing—review and editing, software, investigation, and validation; Y.C.: visualization, data curation, investigation, and validation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Project of Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhanjiang).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Clavelle, T.; Lester, S.E.; Gentry, R.; Froehlich, H.E. Interactions and management for the future of marine aquaculture and capture fisheries. Fish Fish. 2019, 20, 368–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, C.; Cao, L.; Gelcich, S.; Cisneros-Mata, M.; Free, C.M.; Froehlich, H.E.; Golden, C.D.; Ishimura, G.; Maier, J.; Macadam-Somer, I. The future of food from the sea. Nature 2020, 588, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.; Yang, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, B. Spatial Distribution and Differentiation Analysis of Coastal Aquaculture in China Based on Remote Sensing Monitoring. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredheim, A.; Reve, T. Future Prospects of Marine Aquaculture. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2018 MTS/IEEE Charleston, Charleston, SC, USA, 22–25 October 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Dong, Y.; Cao, L.; Verreth, J.; Olsen, Y.; Liu, W.; Fang, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Li, L.; Li, J. Optimization of aquaculture sustainability through ecological intensification in China. Rev. Aquac. 2022, 14, 1249–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napier, J.A.; Haslam, R.P.; Olsen, R.E.; Tocher, D.R.; Betancor, M.B. Agriculture can help aquaculture become greener. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 680–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.I.; Wang, C.M.; Park, J.C.; Lader, P.F. Review of cage and containment tank designs for offshore fish farming. Aquaculture 2020, 519, 734928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, X.; Shan, J.; Han, L.; Song, H. Research on the efficacy and effect assessment of deep-sea aquaculture policies in China: Quantitative analysis of policy texts based on the period 2004–2022. Mar. Policy 2024, 160, 105963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Zhang, S.; Chen, P. Research progress and prospects on benefit assessment of marine ranching. South China Fish. Sci. 2024, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.I.; Dua, Y.; Wei, Y.; An, D.; Liu, J. Application of intelligent and unmanned equipment in aquaculture: A review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 199, 107201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, S.; Lin, J. Marine Ranching Construction and Management in East China Sea: Programs for Sustainable Fishery and Aquaculture. Water 2019, 11, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.S. Construction of marine ranching in China: Reviews and prospects. J. Fish. China 2016, 40, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slabbekoorn, H.; Bouton, N.; Opzeeland, I.V.; Coers, A.; Cate, C.T.; Popper, A.N. A noisy spring: The impact of globally rising underwater sound levels on fish. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, K.D.; Forland, T.N.; Amorim, M.C.P.; Rieucau, G.; Slabbekoorn, H.; Sivle, L.D. Predicting the effects of anthropogenic noise on fish reproduction. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2020, 30, 245–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, V.L.G.; Williamson, L.D.; Jiang, J.; Cox, S.E.; Ruffert, M. Prediction of marine mammal auditory-impact risk from Acoustic Deterrent Devices used in Scottish aquaculture. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 165, 112171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, D.; Lin, M.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, R.; Chu, S. A long-term cruise monitoring system for marine ranching based on surface docking station. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2022, Hampton Roads, VA, USA, 17–20 October 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmentier, E.; Tock, J.; Falguière, J.C.; Beauchaud, M. Sound production in Sciaenops ocellatus: Preliminary study for the development of acoustic cues in aquaculture. Aquaculture 2014, 432, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Du, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Du, L. Recent advances in acoustic technology for aquaculture: A review. Rev. Aquac. 2024, 16, 357–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Zhao, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, C.; Xu, Z. Adaptive Recognition of Bioacoustic Signals in Smart Aquaculture Engineering Based on r-Sigmoid and Higher-Order Cumulants. Sensors 2022, 22, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, X.; Peng, Y.; Zou, Z.; Su, G. Research on centralized remote monitoring system for offshore cage farm. In Proceedings of the 2012 Oceans—Yeosu, Yeosu, South Korea, 21–24 May 2012; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Yu, W.; Lu, B.; Cheng, S. Development status and prospect of Chinese deep-sea cage. J. Fish. China 2021, 45, 992–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knol-Kauffman, M.; Nielsen, K.N.; Sander, G.; Arbo, P. Sustainability conflicts in the blue economy: Planning for offshore aquaculture and offshore wind energy development in Norway. Marit. Stud. 2023, 22, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.D.; Chick, R.C.; Lorenzen, K.; Agnalt, A.L.; Leber, K.M.; Blankenship, H.L.; Haegen, G.V.; Loneragan, N.R. Fisheries enhancement and restoration in a changing world. Fish. Res. 2017, 186, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhen, X.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, H. Conceptual Design and Structural Performance Analysis of an Innovative Deep-Sea Aquaculture Platform. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, C.; Slater, M. Soundscapes in aquaculture systems. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2019, 11, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javier, R.F.; Jaime, R.; Pedro, P.; Jesus, C.; Enrique, S. Analysis of the Underwater Radiated Noise Generated by Hull Vibrations of the Ships. Sensors 2023, 23, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICS Shipping. Underwater Radiated Noise Guide, 1st ed.; ICS Shipping: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hang, S.; Zhu, X.; Ni, W. Low-frequency band noise generated by industrial recirculating aquaculture systems exhibits a greater impact on Micropterus salmoidess. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 272, 116074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Lin, J.; Yi, X.; Jiang, P. Research on band energy extraction and classification of three kinds of fishes sound signals. Technol. Acoust. 2021, 40, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladich, F.; Bass, A.H.; Farrell, A.P. Hearing and Lateral Line | Vocal Behavior of Fishes: Anatomy and Physiology. Encycl. Fish Physiol. 2011, 1, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasumyan, A.O. Sounds and sound production in fishes. J. Ichthyol. 2008, 48, 981–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/DIS 17208-3:2023; Underwater Acoustics—Quantities and Procedures for Description and Measurement of Underwater Sound from Ships—Part 3: Requirements for Measurements in Shallow Water (Draft). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- Zhang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Xv, C.; Liu, S.; Zhou, S.; Zhou, Z. Analysis of Self-noise Characteristics of Fully-Actuated Autonomous Underwater Vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2024 7th International Conference on Information Communication and Signal Processing (ICICSP), Zhoushan, China, 31 December 2024; pp. 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urick, R. Principles of Underwater Sound; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Zeddies, D.G.; Fay, R.R. Structural and functional effects of acoustic exposure in goldfish: Evidence for tonotopy in the teleost saccule. BMC Neurosci. 2011, 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winberg, S.; Thörnqvist, P.-O.; Nilsson, G.E. The Behavioral and Neurobiological Response to Sound Stress in Salmon. Brain Behav. Evol. 2023, 100, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Wang, C. Exploring Sound Frequency Detection in the Golden Rabbitfish, Siganus guttatus: A Behavioral Study. Animals 2024, 14, 2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. Analysis of Fish Acoustic Signal Analysis and Feature Extraction Based on Multi-Feature Fusion. Ph.D. Thesis, Guangdong Ocean University, Zhanjiang, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Popper, A.N.; Hawkins, A.D.; Fay, R.R.; Mann, D.A.; Bartol, S.; Carlson, T.J.; Coombs, S.; Ellison, W.T.; Gentry, R.L.; Halvorsen, M.B. ASA S3/SC1.4 TR-2014 Sound Exposure Guidelines for Fishes and Sea Turtles: A Technical Report Prepared by ANSI-Accredited Standards Committee S3/SC1 and Registered with ANSI; Springer International Publishing: Berlin, German, 2014. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).