Abstract

Bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) are an important species in the Arctic ecosystem, but their conservation is challenged by environmental noise from shipping and climate change. Effective monitoring of Bowhead whale vocalizations is essential for their conservation, yet traditional acoustic methods face limitations in detecting weak and non-stationary signals amidst complex background noise. In this study, we propose a novel method, Local Maximum Simultaneous Extraction of Generalized S-Transforms (LMSEGST), to enhance the feature extraction of Bowhead whale calls. The LMSEGST method integrates generalized S-transforms with local maximum extraction, improving time-frequency resolution and noise immunity. We compare the performance of LMSEGST with traditional methods (STFT, GST, and LMSST) using synthetic and real-world datasets. The results show that LMSEGST outperforms the other methods, with a 28.32% reduction in Rayleigh entropy compared to STFT at 5 dB SNR and a 28.24% reduction compared to LMSST at 10 dB SNR. Additionally, LMSEGST maintained higher SNR values, demonstrating superior noise resistance. These findings suggest that LMSEGST offers a more robust solution for acoustic monitoring of Bowhead whales, particularly in noisy, Arctic environments, contributing to more effective conservation strategies for this species.

1. Introduction

Bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) are a critical species in the Arctic ecosystem, playing a key role in the region’s biodiversity and food web [1]. However, these whales are facing increasing threats due to the combined effects of climate change and human activities. The rapid melting of sea ice due to global warming has altered their migratory paths and foraging ecology, while the expansion of Arctic shipping lanes has introduced new risks, such as ship noise, oil pollution, and potential collisions [2,3,4]. The conservation of Bowhead whales has become a priority, and efficient monitoring of their populations is essential to inform conservation strategies.

Traditional methods of monitoring marine mammals, such as visual observations and tagging, are often limited by environmental conditions, cost, and scalability. In contrast, Passive Acoustic Monitoring (PAM) offers a non-invasive, scalable approach to studying cetacean populations by detecting their vocalizations [5]. However, acoustic monitoring of Bowhead whales is particularly challenging due to the non-stationary nature of their vocalizations and the complex background noise in the Arctic environment, such as ship noise and ice cracking. These challenges result in ambiguous time-frequency representations, which can make signal extraction difficult.

Recent advances in acoustic signal processing methods have sought to address these challenges. Time-frequency analysis techniques, such as Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) and Wavelet Transforms (WT), have been widely used to analyze cetacean vocalizations [6,7,8]. While STFT is effective for stationary signals, its fixed time-frequency resolution limits its performance for non-stationary signals like those of Bowhead whales. Similarly, although WT and Synchrosqueezing Transforms (SST) improve time-frequency concentration, they still struggle with noise leakage and resolution, especially under low-frequency conditions relevant to Bowhead whale calls.

To overcome these limitations, Local Maximum Synchrosqueezing Transform (LMSST) was introduced as an enhancement to SST, focusing on preserving local extrema and improving resolution [9,10,11,12]. However, LMSST still faces the issue of noise interference from out-of-band signals, particularly in noisy environments like the Arctic. Building on these advancements, we propose a novel approach known as Local Maximum Simultaneous Extraction of Generalized S-Transforms (LMSEGST), which integrates a dynamic windowing mechanism with local maximum extraction. This method allows for adaptive frequency window adjustments, resulting in improved time-frequency resolution and reduced noise interference. The LMSEGST method is designed to provide a more accurate and robust tool for the acoustic monitoring of Bowhead whale vocalizations, even in challenging, noisy environments.

The novelty of this study lies in the combination of the generalized S-transform (GST) with the local maximum extraction technique from LMSST, which addresses the limitations of previous methods by improving feature extraction in non-stationary and noisy signals. This paper demonstrates the potential of LMSEGST by evaluating its performance against traditional methods such as STFT, GST, and LMSST, using Rayleigh entropy as a measure of time-frequency energy aggregation. Additionally, we test the method under varying noise conditions, including white Gaussian noise (WGN) and non-Gaussian noise, to evaluate its robustness in real-world applications.

This work contributes to the growing body of research aimed at enhancing the efficiency and accuracy of acoustic monitoring systems for marine mammals, particularly in the face of environmental changes and increasing human activities in the Arctic region.

2. Literature Review

The study of Bowhead whale vocalizations has become increasingly important in understanding the species’ behavior, migration patterns, and response to environmental stressors. Acoustic monitoring techniques, particularly Passive Acoustic Monitoring (PAM), have proven effective for long-term monitoring of marine mammal populations. However, extracting meaningful features from Bowhead whale calls remains challenging due to the complexity of their vocalizations, the non-stationary nature of their signals, and the presence of ambient noise such as ship traffic, ice cracking, and other oceanic sounds.

Various acoustic signal processing techniques have been employed to address the challenges associated with non-stationary whale calls [13,14]. One widely used method is the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT), which splits a signal into overlapping segments and performs a Fourier transform on each segment [6]. However, STFT has inherent limitations in time-frequency resolution due to the fixed window size, making it difficult to capture transient features of complex and non-stationary signals like those of Bowhead whales.

To overcome the limitations of STFT, Wavelet Transforms (WT) have been introduced as an alternative [7,8]. WT offers better time-frequency localization and is more adaptable to the non-stationary nature of whale calls. The Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT), for example, is used to decompose a signal into components at various scales, making it more effective at capturing transient events. However, WT still has limitations in terms of frequency resolution when dealing with signals that contain multiple components with overlapping frequency ranges.

The Synchrosqueezing Transform (SST) is a more recent method that provides improved time-frequency resolution by focusing on the local extrema of the time-frequency representation. SST has been particularly successful in enhancing the time-frequency distribution of non-stationary signals and has been applied to several marine mammal vocalizations. For example, Yu et al. (2019) [10] utilized SST for the analysis of cetacean vocalizations, showing significant improvements in time-frequency representation when compared to STFT and WT. However, SST still suffers from energy leakage, particularly in the presence of strong background noise, which can reduce the clarity of weak signals, such as those of Bowhead whales.

Despite the advantages of SST and WT, there remain challenges in monitoring Bowhead whale calls in the Arctic where noise from shipping, ice-cracking, and weather conditions often masks the vocalizations. Traditional methods like STFT and WT often fail to separate the signal of interest from noise, especially when the signal contains overlapping frequency components or when background noise is significant.

In this context, LMSST (Local Maximum Synchrosqueezing Transform) has been introduced to address the issue of energy leakage [10,11]. LMSST refines the time-frequency representation by preserving the local maxima in the time-frequency plane, improving the separation of overlapping components. However, LMSST still faces challenges in highly noisy environments where background interference is high.

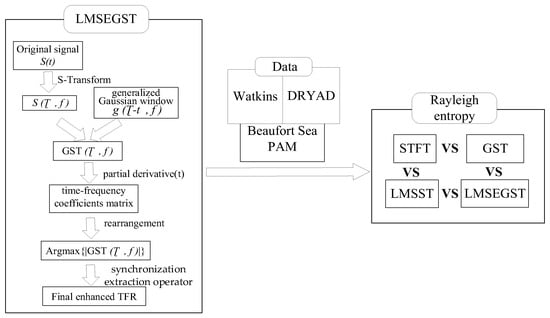

The Local Maximum Simultaneous Extraction of Generalized S-Transforms (LMSEGST) method, which is introduced in this study, represents a significant advancement in the field of acoustic signal processing for cetaceans. By combining the generalized S-transform (GST), which adjusts the window dynamically based on frequency content, with local maximum extraction, LMSEGST provides a higher resolution in time-frequency representations compared to STFT, GST, and LMSST. This dual approach enables adaptive time-frequency windowing, allowing for better detection of weak and overlapping signals in the presence of noise. Figure 1 presents a graphical overview of the proposed LMSEGST framework. The main contribution of this paper is the development of the LMSEGST method for the feature extraction of Bowhead whale calls, providing a novel approach for improving time-frequency resolution and noise immunity in acoustic signal analysis. This work is positioned within the broader field of acoustic signal enhancement for marine life monitoring, contributing to the development of more efficient tools for passive monitoring in noisy and dynamic environments.

Figure 1.

The graphical framework of the research.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources and Pre-Processing

The original sound recordings of Bowhead whales were obtained from the Watkins Marine Mammal Sound Database and the DRYAD database. In the Watkins database, we selected 60 WAV format Bowhead whale sound clips, with a size of 8.66 MB. Among them, 5 sound files were recorded in the Bering Strait, 6 sound files were recorded in Barrow, Alaska, and 49 sound files were recorded in the Beaufort Sea, Bailey Islands. The length of these recordings ranged from approximately 2 to 7 s. Table 1 describes the information on the Bowhead whale sounds in the Watkins database, including the sampling frequency and frequency range of the sounds. In addition, the Dryad database provides 184 MP3 format Bowhead whale singing files recorded by Stafford, Kathleen M. et al. [15] in the Fram Strait over three consecutive winters, with a size of 253 MB. Among them, 39 vocal files were recorded in 2010–2011, 69 vocal files were recorded in 2012–2013, and 76 vocal files were recorded in 2013–2014. Due to the differences in sampling frequency and audio format of the recordings from different databases, in order to ensure consistency and comparability in the subsequent processing, this paper converts all the Bowhead whale recordings to 10 KHz sampling frequency and WAV audio format.

Table 1.

Information from the Watkins database.

Erbs et al. [13] found 13 Bowhead whale singing groups with similar hierarchical structure and units in an unstudied wintering site in northeastern Greenland during the winter of 2013–2014, which provided theoretical support for the feature labeling of the Deep Learning Network dataset in this paper. Erbs et al.’s study summarized the nine unit types of Bowhead whales [15] as shown in Table 2. Based on these basic features, this paper uses Adobe Audition 2022 (Version 22.6) to label the actual acquired Bowhead whale recordings. Through careful processing, the more obvious features of Bowhead whale signals in the recordings were selected as learning training materials and their labels were set to 1. Accordingly, for non-Bowhead whale signals, their labels were set to 0. This acoustic feature-based classification method provides a reasonable basis for this study.

Table 2.

The main acoustic characteristics of Bowhead whales summarized by Erbs F. et al. [13].

Table 2 presents a summary of the key acoustic characteristics of 9 unit types of Bowhead whale songs. The abbreviations used in the “Unit sub-type” column are referenced from Erbs F’s article [13], which represents different types of subunits. The subcategories in this table refer to different types of vocalizations identified within the Bowhead whale calls. These include male song vocalizations (MSG1, MSG5), non-song vocalizations (NSG11), mating vocalizations (Mo), short-range vocalizations (S), and rhythmic vocalizations (Short R, Long R), among others.

In this paper, the enframe function in MATLAB (R2021b) software is used to process the acquired recording data into frames. Referring to the sub-frame length used by Bu Rinran et al. [16] to classify Killer whales and Long-finned pilot whales using convolutional neural networks, in this paper, the frame length is set to one-fourth of the frequency, and the value of the frame shift is consistent with the frame length. A total of 5782 data points were obtained in the final training set, including 4345 data points of Bowhead whale sounds and 1437 data points of background noise.

3.2. Feature Extraction Methods

In order to improve the concentration, Daubechies et al. [17] proposed Synchrosqueezed wavelet transform (SWT), which is based on WT and effectively improves the concentration of time-frequency energy by squeezing the energy around the time-frequency. Oberlin et al. [9] used STFT instead of WT to form a synchrosqueezing transform (SST) on the basis of SWT. Oberlin et al. [9] used STFT instead of WT to form the Synchrosqueezing transform (SST) based on STFT. In 2017, Yu et al. proposed the Synchro Extracting Transform (SET) [18] by drawing on the SST algorithm. In addition, Yu et al. [10] further proposed Multi-synchrosqueezing transform (MSST) based on SST, which effectively improves the aggregation of time-frequency energy through multiple compression transforms. Recently, Yu et al. [12] proposed a Local Maximum Synchrosqueezing transform (LMSST) method, which achieves higher time-frequency resolution by preserving the modal extrema of the time-frequency coefficients within a window in the frequency direction. However, LMSST is essentially an improvement of SST and suffers from the problem of squeezing out-of-band noise interference into the instantaneous frequency location, which affects its time-frequency aggregation. In addition, since LMSST is an STFT-based method, it suffers from the fixed STFT window function. In order to solve the above problems, a new Local Maximum Synchroextracting Generalized S-Transform (LMSEGST) method is proposed in this paper by combining GST [19] with Local Maximum Synchroextracting Transform (LMSST).

Assuming that S(t) is a non-stationary signal, take the signal shown in Equation (1) for example.

where and are the amplitude and phase of the signal, respectively. The S-transform is first applied to and the result is shown in Equations (2) and (3) is the selected Gaussian window.

where is the frequency, is the time, and is the time axis displacement parameter.

The generalized S-transform uses a generalized Gaussian window with the expression shown in Equations (2)–(4). The coefficient parameter p and power parameter q control the window width and time-frequency resolution, respectively. Unlike the traditional S-transform, the generalized S-transform allows the window width to be dynamically adjusted according to the local frequency characteristics of the signal, which makes it possible to better adapt to the time-frequency variations in the signal when analyzing non-stationary signals.

Substituting Equation (4) into the S-transform result Equation (2), i.e., convolving the signal with a Gaussian window, the result of the generalized S-transform (GST) can be obtained, and the specific expression is shown in Equation (5).

For the pre-processing generalized S-transform results takes partial derivatives with respect to time to obtain the time-frequency coefficients matrix, and the results are shown in Equation (6).

When performing the rearrangement of the time-frequency coefficients matrix, since is used as the row number of the time-frequency coefficients, it needs to be rounded up and down by Equation (7) to ensure that the integer part is obtained.

Subsequently, a sliding window is constructed and only the instantaneous frequency corresponding to the time-frequency coefficients modulo the maximum value of the time-frequency coefficients within the window is retained as shown in Equation (8).

where ∆ is the frequency band range and {∙} denotes the value of f corresponding to when the value or function in parentheses is taken to its maximum value.

Finally, the synchronization extraction operator is used to extract the time-frequency coefficients that are similar to the instantaneous frequency, and the result is shown in Equation (9).

where denotes the center of the squeezed interval , {∙} is the Dirac function.

While conventional methods usually emphasize only the global extremes, LMSEGST focuses on the maximum values in a local range. This local focus makes LMSEGST more suitable for analyzing non-stationary signals. By emphasizing local maxima, LMSEGST is able to provide higher time-frequency resolution and better accommodate the time-varying nature of the signal. This approach provides a more sensitive analytical tool for capturing transient characteristics and short-term variations in Bowhead whale signals.

Researchers found that when the spectral function under each moment of the time-frequency representation is regarded as a probability density function, the larger the value of information entropy is, the lower the concentration of the distribution of the time-frequency representation is [20]. On this basis, Baraniuk [21] proposed the use of Rayleigh entropy to evaluate the aggregation of the time-frequency representation by effectively combining the information entropy and the time-frequency representation. Therefore, in this paper, we use Rayleigh entropy to measure the degree of time-frequency energy aggregation, which is embodied as the pseudo probability density function of time-frequency energy [22]. According to the value of Rayleigh entropy, the time-frequency aggregation can be measured simply and effectively. α-order Rayleigh entropy is defined as Equation (10):

where is a function not equal to 0. The smaller the value of Rayleigh entropy, the higher the degree of aggregation of the function. Applying Equations (2)–(10) to the evaluation of the time-frequency representation, the α-order Rayleigh entropy in the time-frequency distribution can be defined as:

where denotes the time-frequency distribution of the signal, and is a constant satisfying . represents the frequency of the analyzed signal. When , Rayleigh entropy degenerates into Shannon. The smaller the Rayleigh entropy value, the better the clustering of the time-frequency representation.

The core of this methodology lies in feature extraction using the LMSEGST method, which integrates the generalized S-transform (GST) and local maximum extraction. In this study, the MATLAB scripts used for feature extraction were custom-designed and follow the general steps outlined below. Generalized S-Transform (GST): The GST was applied to the segmented signal to generate a time-frequency representation. The MATLAB script used for GST applies a dynamic window that adjusts according to the frequency content, providing an adaptive time-frequency resolution. This was implemented using the gst( ) function available in MATLAB, with a window size of 512 samples and 50% overlap. A Gaussian window function was applied which dynamic width control based on the frequency characteristics of the signal. Local Maximum Extraction: The local maximum extraction procedure was applied to the time-frequency representation obtained from the GST. The local_max( ) function in MATLAB was developed to identify local maxima in the time-frequency matrix, which are assumed to correspond to key features of the whale calls. LMSEGST Combination: Finally, the LMSEGST method was developed by combining the local maximum extraction with dynamic frequency window adjustments. The script applies a simultaneous extraction of local maxima across different frequency bands, improving the clarity of the extracted features. The adaptive windowing mechanism enables better resolution in the frequency domain for non-stationary signals.

The signal detection process was based on the identification of key features in the time-frequency domain.

Step 1: Feature Extraction: For each windowed segment, the Rayleigh entropy was computed to quantify the concentration of energy in the time-frequency representation. A low Rayleigh entropy value indicates a more compact time-frequency distribution. The feature extraction script implemented in MATLAB used the rayleigh_entropy( ) function to calculate this value.

Step 2: Manual Validation: A subset of the detected signals was manually verified by marine mammal experts to ensure that the identified features corresponded to known Bowhead whale vocalization patterns. These manual labels were used to build a training dataset for further automated classification.

Step 3: Automated Classification: For automated classification, a support vector machine (SVM) classifier was trained on the extracted features (including frequency band and duration). The SVM classifier was implemented using the fitcsvm( ) function in MATLAB, with a radial basis function (RBF) kernel. This classifier was trained using a subset of labeled whale calls, and its performance was evaluated using cross-validation techniques.

All experiments were performed on a workstation with an Intel Core i7 processor, 32 GB RAM, and Windows 10 (64-bit). The algorithms were implemented in MATLAB R2021b using the Signal Processing Toolbox. No GPU hardware was used during the evaluation.

4. Results

Comparison of Feature Enhancement Methods

The goal of this section is to validate the effectiveness and accuracy of the LMSEGST method in Bowhead whale acoustic signal processing. Therefore, in this paper, two measured signals, Fram2010-5 and Fram2010-17, were selected from Dryad database and a portion of each was taken as the object of study and analyzed by applying a set of parameters.

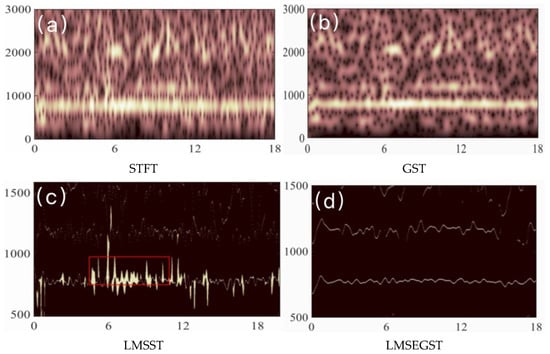

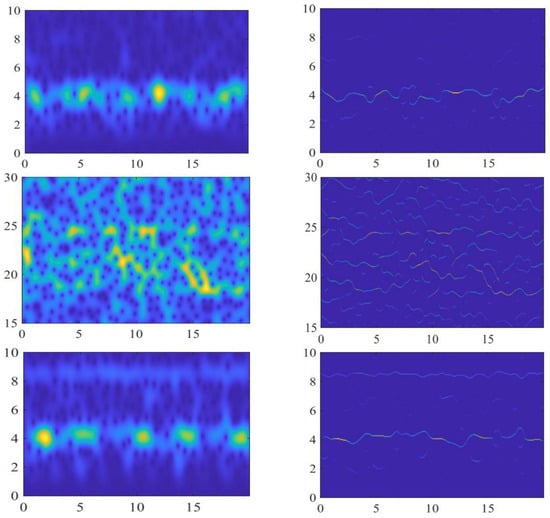

Considering the Fram2010-5 signal in Dryad database, STFT, GST, LMSST, LMSEGST are used to enhance the features of some of the signals, and the results are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Results of STFT, GST, LMSST and LMSEGST on Fram2010-5, respectively.

Figure 2 shows the comparison of time-frequency representations for Bowhead whale calls using different methods (STFT, GST, LMSST, and LMSEGST). The LMSEGST method clearly provides a higher resolution in both time and frequency compared to STFT, GST, and LMSST, especially in distinguishing weak calls from background noise.

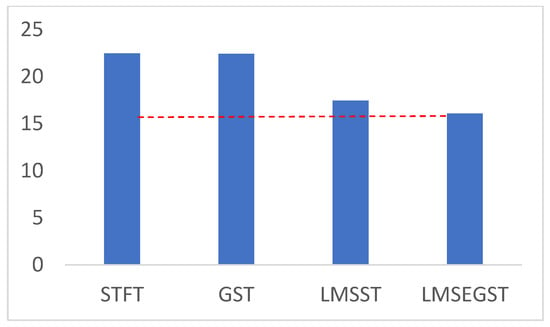

To more intuitively highlight the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm, the coordinate range was narrowed. The red dashed line in Figure 3 helps to compare the results of the four methods. As shown in Figure 3, the Rayleigh entropy value of LMSEGST is significantly smaller, which is consistent with the results in Figure 2. Furthermore, Figure 2 also shows that LMSST identifies a frequency band with energy leakage (shown in the red box), while the frequency band energy identified by LMSEGST is relatively more concentrated.

Figure 3.

Comparison of Rayleigh entropy for STFT, GST, LMSST and LMSEGST on Fram2010-5.

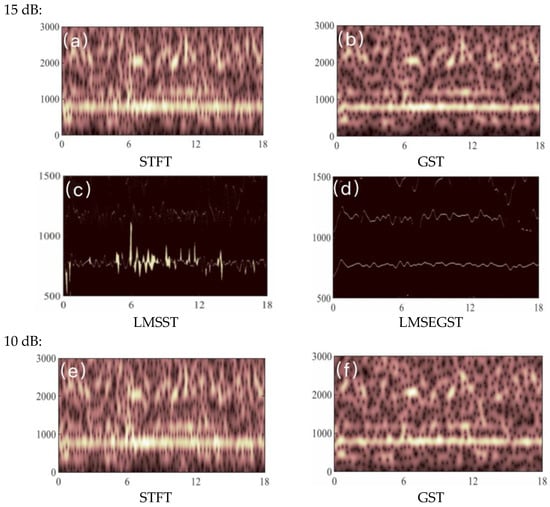

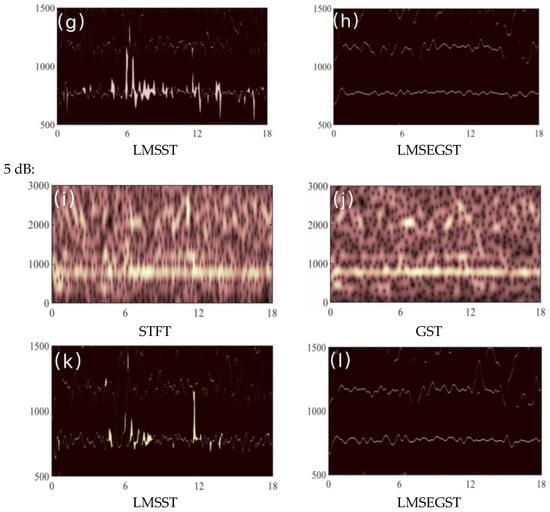

In order to verify the noise immunity of the LMSEGST algorithm, three Gaussian white noises with different signal-to-noise ratios (S/N) of 5 dB, 10 dB and 15 dB are added to the Fram2010-5 signal. The larger the signal-to-noise ratio, the smaller the noise intensity, i.e., the smaller the interference. Subsequently, STFT, GST, LMSST, and LMSEGST were then used to enhance the features of the Bowhead whale sound signals with three different signal-to-noise ratios, and the results are shown in Figure 4. Table 3 demonstrates the Rayleigh entropy values of the four kinds of methods under different signal-to-noise ratios.

Figure 4.

Results of STFT, GST, LMSST and LMSEGST after adding different signal-to-noise ratios to the Fram2010-5 signal, respectively.

Table 3.

Rayleigh entropy of four methods with different signal-to-noise ratios.

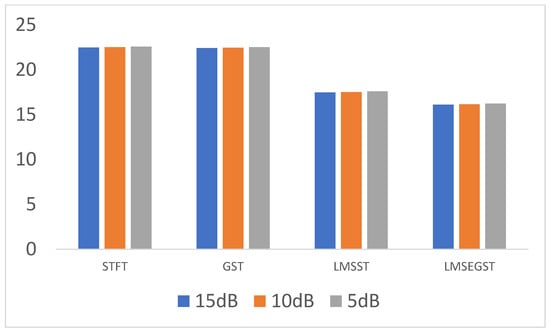

As can be seen from Table 3, at the same SNR, the Rayleigh entropy value corresponding to the LMSEGST feature enhancement method is smaller than that of the LMSST.As the noise intensity increases, the Rayleigh entropy values corresponding to the two methods also increase gradually, but the Rayleigh entropy value corresponding to the LMSEGST is always smaller than that of the LMSST result. At SNR = 5 dB, the Rayleigh entropy value for LMSEGST is 16.10, which is 28.32% lower than that of STFT (22.47), and 6.79% lower than LMSST (17.46). Similarly, the differences at SNR = 10 dB and 15 dB demonstrate that LMSEGST consistently outperforms the other methods in terms of better time-frequency resolution, particularly under noisy conditions. The Rayleigh entropy of LMSEGST relative to STFT is reduced by 28.32%, 28.24%, and 28.15% for the three different SNRs, respectively. The following bar chart (Figure 5) visually illustrates the Rayleigh entropy values for each method at different SNRs, providing a clearer interpretation of the results.

Figure 5.

Rayleigh Entropy Comparison at SNR = 5 dB, 10 dB, and 15 dB.

Obviously, LMSEGST shows better noise immunity at different signal-to-noise ratios. This result further validates the performance advantage of LMSEGST under complex background noise.

5. Application

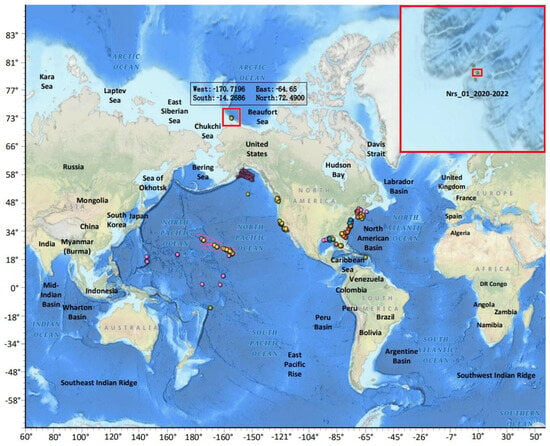

The Beaufort Sea is one of the important habitats for the Bowhead whale population, and its abundant shallow water and sea ice edge provide a suitable environment for Bowhead whales, as well as rich data resources and field observation conditions for researchers [23,24,25,26,27]. Therefore, utilizing the Beaufort Sea as a test site allows for a more comprehensive validation and improvement of Bowhead whale acoustic signal enhancement methods, thereby providing scientific support for the conservation of this rare species and the Arctic ecosystem.

In this paper, measured data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) PAM site in the Arctic Beaufort Sea were selected to validate the LMSEGST feature enhancement method proposed in this paper. The PAM site is located in the Beaufort Sea, with the approximate location referenced in Figure 6, and the specific selected deployment name is NRS_01_20200915- 20220925_HMD. The site recorded hydroacoustic data from 5 September 2020 to 26 September 2022, and the data were stored in flac audio file format, with each file lasting for 4 h. Considering the problem of data storage and computational volume, this paper selects the audio files with monthly date 20 from September 2020 to August 2022, and randomly intercepts 20 consecutive seconds of audio data from each file as test data. In the end, 24 audio files of all 20 s in length, in flac format, with a total size of about 9.28 MB, are obtained.

Figure 6.

Schematic of the Beaufort Sea PAM site.

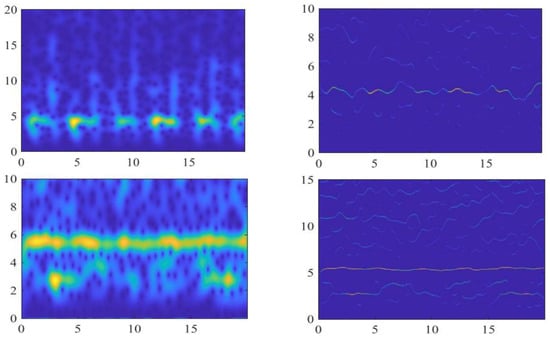

The LMSEGST algorithm proposed in this paper is utilized for feature enhancement of the measured audio from the Beaufort Sea PAM site. In order to show the effect of the proposed algorithm more clearly, this subsection downsamples the audio file to 100 Hz and then performs the time-frequency transform feature enhancement, at the same time, reduces the coordinate range and compares it with the STFT, and some of the results are shown in Figure 7, and the corresponding Rayleigh entropy results are listed in Table 4.

Figure 7.

Comparison of Signal Characterization Enhancement Effects at Beaufort Sea PAM Sites. Left: baseline TFR obtained using STFT. Right: enhanced TFR obtained using the proposed LMSEGST approach.

Table 4.

Results of Rayleigh entropy calculations.

In this study, the STFT was applied to the Bowhead whale call signals for comparison with the LMSEGST method. The STFT was implemented in MATLAB, with a Hamming window (256 samples), 25% overlap, where the recording data were divided into frames using the enframe function, with a frame length equal to one-fourth of the sampling frequency and a frame shift equal to the frame length.

The left part of Figure 7 shows the time-frequency representation of STFT, while the right part shows the output of LMSEGST for direct visual comparison.

From Figure 7, we can see that the time-frequency aggregation of the LMSEGST algorithm is better than that of STFT for the measured signals of different seasons at the Beaufort Sea PAM site. From the results in Table 4, we can see that the Rayleigh entropy of the LMSEGST algorithm proposed in this paper is smaller than that of STFT, and this quantitative result further confirms the feature enhancement effect of the LMSEGST algorithm.

6. Discussion

In this study, we proposed the Local Maximum Simultaneous Extraction of Generalized S-Transforms (LMSEGST) method for enhancing the feature extraction of Bowhead whale vocalizations in complex noise environments. Our results clearly demonstrate that LMSEGST outperforms traditional signal processing methods, such as Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT), Generalized S-Transform (GST), and Local Maximum Synchrosqueezing Transform (LMSST), in terms of time-frequency resolution, noise immunity, and signal detection accuracy.

The key findings of our study reveal that LMSEGST achieves significantly lower Rayleigh entropy values compared to the other methods, indicating better energy concentration in the time-frequency domain. This is consistent with our hypothesis that LMSEGST, with its adaptive windowing mechanism and local maximum extraction, provides a more effective time-frequency representation of Bowhead whale calls. These results align with previous studies, such as those by Yu et al. [12] and Stafford et al. [15], who noted that traditional methods like STFT struggle to resolve weak and overlapping signals in noisy environments. However, our method shows superior performance, particularly at lower Signal-to-Noise Ratios (SNRs), where noise is more prevalent.

The findings of this study hold significant implications for acoustic monitoring of Bowhead whales, particularly in noisy and complex environments like the Arctic, where Bowhead whales are often subjected to high levels of environmental noise from ship traffic, ice-cracking, and weather patterns. The superior performance of LMSEGST under these conditions suggests that it could be a valuable tool for improving the accuracy and reliability of passive acoustic monitoring systems used for marine mammal conservation.

LMSEGST not only provides an improvement in the detection and recognition of Bowhead whale calls but also has broader implications for long-term monitoring in regions where traditional methods face significant limitations. The method’s ability to maintain high SNR and low Rayleigh entropy across varying SNR levels makes it ideal for early detection of cetacean vocalizations, even under challenging conditions, such as distant ship noise or weather-induced disturbances.

Previous studies, such as those by Erbs et al. [13], and Stafford et al. [15], have explored various acoustic monitoring techniques for Bowhead whales. While these studies have contributed significantly to the field, most of the methods they employed, including STFT and GST, have limitations in resolving overlapping components and distinguishing weak signals in noisy environments. For example, Yu et al. [12] and Oberlin et al. [9] acknowledged the advantages of SST and LMSST in improving time-frequency concentration but also noted their susceptibility to energy leakage in high-noise conditions. In contrast, our study demonstrates that LMSEGST providing better time-frequency resolution, reducing energy leakage, and improving signal separation under noise conditions. The introduction of the adaptive windowing mechanism and the local maximum extraction step in LMSEGST is a major advancement, allowing the method to retain the key features of Bowhead whale calls even in noisy environments.

While the LMSEGST method provides notable improvements over existing techniques, there are still some limitations that need to be addressed in future work.

The window size and frequency band parameters used in the GST are empirically set and may need to be adjusted for different environmental conditions or specific species. Future research could explore a more adaptive optimization framework that adjusts these parameters dynamically based on the characteristics of the recorded signal. This would make the method more flexible and suitable for a wider range of marine mammal species and acoustic environments.

The LMSEGST method, while providing excellent results, is computationally intensive. This is particularly challenging for real-time monitoring systems that require low-latency performance, such as those deployed on autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) or remote monitoring buoys. Future improvements could focus on optimizing the algorithm for faster processing, possibly by employing parallel computing techniques or simplifying certain aspects of the signal processing chain.

Although LMSEGST performed well under simulated Gaussian white noise and non-Gaussian noise conditions, real-world noise environments, such as those encountered in the Arctic, may involve more complex impulsive noise or non-stationary noise sources (e.g., ice cracking). Future studies should evaluate the performance of LMSEGST under these more realistic noise conditions to fully assess its robustness in real-world scenarios.

The LMSEGST method was validated for Bowhead whale calls in this study. However, the generalizability of this method to other cetacean species, such as Humpback whales or Fin whales, needs further investigation. The characteristics of different species’ vocalizations, as well as environmental factors specific to other habitats, could require adjustments in the feature extraction and detection procedures.

Future research should focus on the adaptive optimization of the LMSEGST parameters, making the method more versatile for various marine mammal species and acoustic environments. Additionally, the incorporation of real-time processing algorithms and the integration of multi-sensor data (e.g., environmental data such as sea ice conditions or water temperature) would enhance the applicability of LMSEGST in dynamic and complex ecosystems.

The real-time deployment of LMSEGST could be a game-changer for conservation efforts in the Arctic, providing continuous monitoring capabilities that allow for early detection of potential threats to Bowhead whales, such as ship strikes or environmental disturbances.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, an innovative Local Maximum Simultaneous Extraction Generalized S Transform (LMSEGST) method is proposed for the ambiguous time-frequency characterization of the non-smooth call signals of Arctic Bowhead whales in complex noise background. Three major breakthroughs are achieved by integrating the dynamic windowing mechanism of the generalized S-transform with the local maximum simultaneous extraction technique: (1) Significantly improved time-frequency resolution: In the Bowhead whale standard signal (Fram2010-5) processing, the Rayleigh entropy of LMSEGST is reduced by 28.32%, 28.24%, and 28.15% compared with STFT, GST, and LMSST, respectively, which solves the problem of energy diffusion of the traditional method, The key technology is to avoid the out-of-band noise squeezing defects of LMSST through the local maximum extraction mechanism, which improves the time-frequency energy aggregation; (2) Robustness verification in strong noise environment: in the simulated Arctic ship noise environment (5–15 dB Gaussian white noise), the Rayleigh entropy increase in LMSEGST is lower than that of LMSST, and in the 5 dB Gaussian white noise, the Rayleigh entropy increase in LMSEGST is lower than that of LMSST. LMSST, and still maintains the relatively lowest Rayleigh entropy value at 5 dB limit noise; (3) Field long-term monitoring universality confirmation: based on the two-year measured data at the PAM site in the Beaufort Sea, the Rayleigh entropy of LMSEGST is systematically reduced by 28–30% compared with that of STFT, and, in particular,, in the sea-ice melting period of August 2022, the entropy value is reduced to 12.79 (STFT is 18.15), proving its adaptability to seasonal environmental drastic changes, and providing key technical support for cetacean migration research in the context of climate change. The LMSEGST method provides a promising solution for the challenges faced in Bowhead whale monitoring and offers significant potential for real-time conservation efforts in the Arctic. Further research is needed to integrate LMSEGST with other environmental data sources for comprehensive monitoring systems that can support marine mammal conservation under changing climatic and anthropogenic pressures.

Author Contributions

M.Z.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Resources, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Visualization, Formal analysis, Project administration. R.F.: Data Curation, Write, Review and Editing. X.Z.: Data Curation, Write, Review and Editing. P.L.: Data Curation. B.S.: Supervision, Methodology, Data Curation, Write, Review and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the 2023 Zhuhai Industrial-University-Research Collaboration Project” Research and Application of Intelligent Document Services Based on Deep Synthesis Technology” (2320004002767); Zhuhai Industrial Core and Key Technology Research and Development Project “Research and Development of High Performance Integrated Rapid Thermal History Micro Printing SoC Chip” (2320004002531). Department of Education of Guangdong Province Key area projects (2023ZDZX1043); Guangdong Province Cross domain intelligent detection and information processing innovation team (2023KCXTD044); Guangdong Province Key Laboratory of Intelligent Detection in Complex Environment of Aerospace, Land and Sea (2022KSYS016).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Name |

| AUV | Autonomous Underwater Vehicle |

| GST | Generalized S-Transform |

| LMSEGST | Local Maximum Simultaneous Extraction of Generalized S-Transforms |

| LMSST | Local Maximum Synchrosqueezing Transform |

| MSST | Multi-synchrosqueezing Transform |

| NCEI | ational Centers for Environmental Information |

| PAM | Passive Acoustic Monitoring |

| RBF | Radial Basis Function |

| SET | Synchro Extracting Transform |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| SST | Synchrosqueezing Transform |

| STFT | Short-Time Fourier Transform |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| SWT | Synchrosqueezed Wavelet Transform |

| WGN | White Gaussian Noise |

| WT | Wavelet Transform |

References

- Laidre, K.L.; Stern, H.; Kovacs, K.M.; Lowry, L.; Moore, S.E.; Regehr, E.V.; Ferguson, S.H.; Wiig, Ø.; Boveng, P.; Angliss, R.P.; et al. Arctic marine mammal population status, sea ice habitat loss, and conservation recommendations for the 21st century. Conserv. Biol. J. Soc. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 29, 724–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, R.R.; Ewins, P.J.; Agbayani, S.; Heide-Jørgensen, M.P.; Kovacs, K.M.; Lydersen, C.; Suydam, R.; Elliott, W.; Polet, G.; van Dijk, Y.; et al. Distribution of endemic cetaceans in relation to hydrocarbon development and commercial shipping in a warming Arctic. Mar. Policy 2014, 44, 44375–44389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P.O.; Reeves, R.R.; Brownell, R.L., Jr. Status of the world’s baleen whales. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2016, 32, 682–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahonen, H.; Stafford, K.M.; de Steur, L.; Lydersen, C.; Wiig, Ø.; Kovacs, K.M. The underwater soundscape in western Fram Strait: Breeding ground of Spitsbergen’s endangered Bowhead whales. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 123, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estabrook, B.J.; Bonacci-Sullivan, L.A.; Harris, D.V.; Hodge, K.B.; Rahaman, A.; Rickard, M.E.; Salisbury, D.P.; Schlesinger, M.D.; Zeh, J.M.; Parks, S.E.; et al. Passive acoustic monitoring of baleen whale seasonal presence across the New York Bight. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0314857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahoura, M.; Simard, Y. Blue whale calls classification using short-time Fourier and wavelet packet transforms and artificial neural network. Digit. Signal Process. 2009, 20, 1256–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplun, D.; Voznesensky, A.; Romanov, S.; Andreev, V.; Butusov, D. Classification of Hydroacoustic Signals Based on Harmonic Wavelets and a Deep Learning Artificial Intelligence System. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhou, B.; Yu, W. Passive CFAR detection based on continuous wavelet transform of sound signals of marine animal. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Signal Processing, Communications and Computing (ICSPCC), Xiamen, China, 22–25 October 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberlin, T.; Meignen, S.; Perrier, V. The Fourier-based synchrosqueezing transform. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Florence, Italy, 4–9 May 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 315–319. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, G.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, P. Multi-synchrosqueezing Transform. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 66, 5441–5455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, Y.U. A multisynchrosqueezing-based high-resolution time-frequency analysis tool for the analysis of non-stationary signals. J. Sound Vib. 2021, 492, 115813. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, G.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, P.; Li, Z. Local maximum synchrosqueezing transform: An energy-concentrated time-frequency analysis tool. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 117, 537–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbs, F.; van der Schaar, M.; Weissenberger, J.; Zaugg, S.; André, M. Contribution to unravel variability in Bowhead whale songs and better understand its ecological significance. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, M.K. Increasing detections of killer whales (Orcinus orca), in the Pacific Arctic. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2019, 35, 696–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, K.M.; Lydersen, C.; Wiig, Ø.; Kovacs, K.M. Data from: Extreme diversity in the songs of Spitsbergen’s Bowhead whales. Biol. Lett. 2018, 14, 20180056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bu, L.R. Study on Identification and Classification Methods of Whale Acoustic Signals between Whale Species. Master’s Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Daubechies, I.; Lu, J.; Wu, H.T. Synchrosqueezed wavelet transforms: An empirical mode decomposition-like tool. Appl. Comput. Harmon. Anal. 2011, 30, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Yu, M.J.; Xu, C.Y. Synchroextracting transform. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 8042–8054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.D.; Kossentini, F.; Ward, R.K. Generalized S Transform. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2002, 50, 2831–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.H. Research and Application of Wavelet Time-Frequency Synchronous Compression Transform Method. Master’s Thesis, Xidian University, Xi’an, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Baraniuk, R.G.; Flandrin, P.; Janssen, A.J.E.M.; Michel, O.J.J. Measuring timefrequency information content using the Renyi entropies. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2001, 47, 1391–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanković, L. A measure of some time–frequency distributions concentration. Signal Process. 2001, 81, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.C.; Clark, C.; Carroll, G.M.; Ellison, W.T. Observation on the icebreaking and ice navigation behavior of migrating Bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) near Point Barrow, Alaska, Spring 1985. Arctic 1989, 42, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, C. The Bowhead Whale. Balaena mysticetus: Biology and Human Interactions. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2021, 37, 1572–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towers, J.R.; Pilkington, J.F.; Mason, E.A.; Mason, E.V. A Bowhead whale in the eastern North Pacific. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, e8664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elizabeth Alter, S.; Rosenbaum, H.C.; Postma, L.D.; Whitridge, P.; Gaines, C.; Weber, D.; Egan, M.G.; Lindsay, M.; Amato, G.; Dueck, L.; et al. Gene flow on ice: The role of sea ice and whaling in shaping Holarctic genetic diversity and population differentiation in Bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus). Ecol. Evol. 2012, 2, 2895–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NOAA Fisheries. 2018 Marine Mammal Stock Assessment Reports by Species/Stock: Bowhead Whale. Available online: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/marine-mammal-protection/marine-mammal-stock-assessment-reports-species-stock (accessed on 24 July 2020).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).