1. Introduction

With the increasing deployment of long-endurance autonomous underwater platforms, there is a growing demand for reliable, controllable, and efficient underwater release systems to support tasks such as deep-sea observation equipment deployment, mooring buoy release, and payload jettison from underwater vehicles. Among various actuation methods, high-pressure gas driven ejection offers a compact, energy-dense, and precisely controllable solution for underwater operations under extreme hydrostatic conditions. Understanding the complex hydrodynamic and cavitation phenomena involved in such processes is crucial for ensuring the stability, safety, and performance of release mechanisms. In this context, the investigation of underwater spherical ejection driven by high-pressure gas provides fundamental insights into unsteady flow dynamics and cavitation evolution.

The high-speed motion of underwater objects can lead to a local drop in fluid pressure. When the pressure falls below the vapor pressure of water, the liquid water transforms into vapor—a phenomenon known as cavitation (Shi et al., 2023) [

1]. Cavitation typically involves three stages: inception, development, and collapse (Wang et al., 2025) [

2]. This process is characterized by strong nonlinearity and instability and is often accompanied by complex issues such as multiphase flow, turbulence, and mass transfer. Cavitation tends to occur in high-velocity regions such as hydrofoils (Ji et al., 2015) [

3], marine propellers (Bensow and Bark, 2010) [

4], and underwater high-speed vehicles (Zhao et al., 2022) [

5]. The occurrence of cavitation is primarily governed by a dimensionless number known as the cavitation number, defined as

, in which

is the reference pressure of the surrounding fluid,

is the vapor pressure of the fluid at the corresponding temperature,

is the fluid density, and

is the characteristic velocity of the flow. During the underwater high-speed motion of an object, the motion state directly influences the development of cavitation and the evolution of the surrounding flow field (Shi et al., 2023) [

6]. Compared with conventional underwater motion, the flow during the ejection from an launch tube is more complex and exhibits stronger nonlinear characteristics (Lin et al., 2023) [

7]. Therefore, studying the ejection of a rotating sphere under such conditions can complement existing research and provide critical insights.

Currently, many researchers have focused on the flow field, cavity dynamics, and motion characteristics during the high-speed underwater ejection of objects. Research in this area is mainly divided into two aspects: one focuses on analyzing the mechanisms of cavity evolution, shedding, and collapse during the process; the other concentrates on the vortex structures and vortex shedding at the rear of the body.

Xu et al. (2019) [

8] and Lu et al. (2022) [

9] conducted numerical and experimental studies, respectively, on two successively ejected projectiles, analyzing the influence of the wake vortex from the leading projectile on the following one. Gao et al. (2022) [

10] performed numerical simulations of projectile ejection under different Froude numbers and transverse flow velocities, revealing how launch speed and crossflow affect the wake vortex. Wang et al. (2024) [

11] conducted experiments on vertical motion under ventilated conditions, analyzing the coupling between the wake cavity and jet and uncovering the mechanisms behind cavity evolution. Gao et al. (2025) [

12] conducted numerical simulations of continuous underwater projectile launches, investigating transient cavitation structures and motion characteristics. They also compared different projectile axial spacing and found that the trailing projectile’s cavity experienced large-scale collapse due to the leading projectile’s wake, yet maintained stable motion. Wang et al. (2016) [

13] carried out a typical experiment on vertical underwater launch, analyzing the evolution of cavitation modes, cavity collapse, and the resulting strong re-entrant jet, revealing the collapse mechanism within the cavity and conducting corresponding numerical simulations. Gan et al. (2022) [

14] experimentally studied the dynamic characteristics of vertically moving objects under ventilation, identifying three motion modes of ventilated bubbles. Cao et al. (2012) [

15] used numerical simulations to study the underwater projectile launch process, finding pressure and cavity volume oscillations at the tail and analyzing their causes, thereby revealing the influence on projectile trajectory. Ren et al. (2024) [

16] conducted numerical simulations of vertical launch processes, analyzing tail cavity oscillations under different Froude numbers. They observed four tail cavity flow modes and found that higher Froude numbers increased cavity volume and the proportion of irregular regions. Liu et al. (2023) [

17] performed numerical simulations of rigid projectile launches, establishing a multi-field coupling model for underwater ejection. They focused on the evolution of the multiphase flow field, bubble development mechanisms at the muzzle, and load response of projectile trajectories.

Secondly, this study investigates the underwater launch process of a rotating sphere. In terms of the sphere’s underwater motion and flow characteristics, many scholars have conducted extensive research through both experiments and numerical simulations.

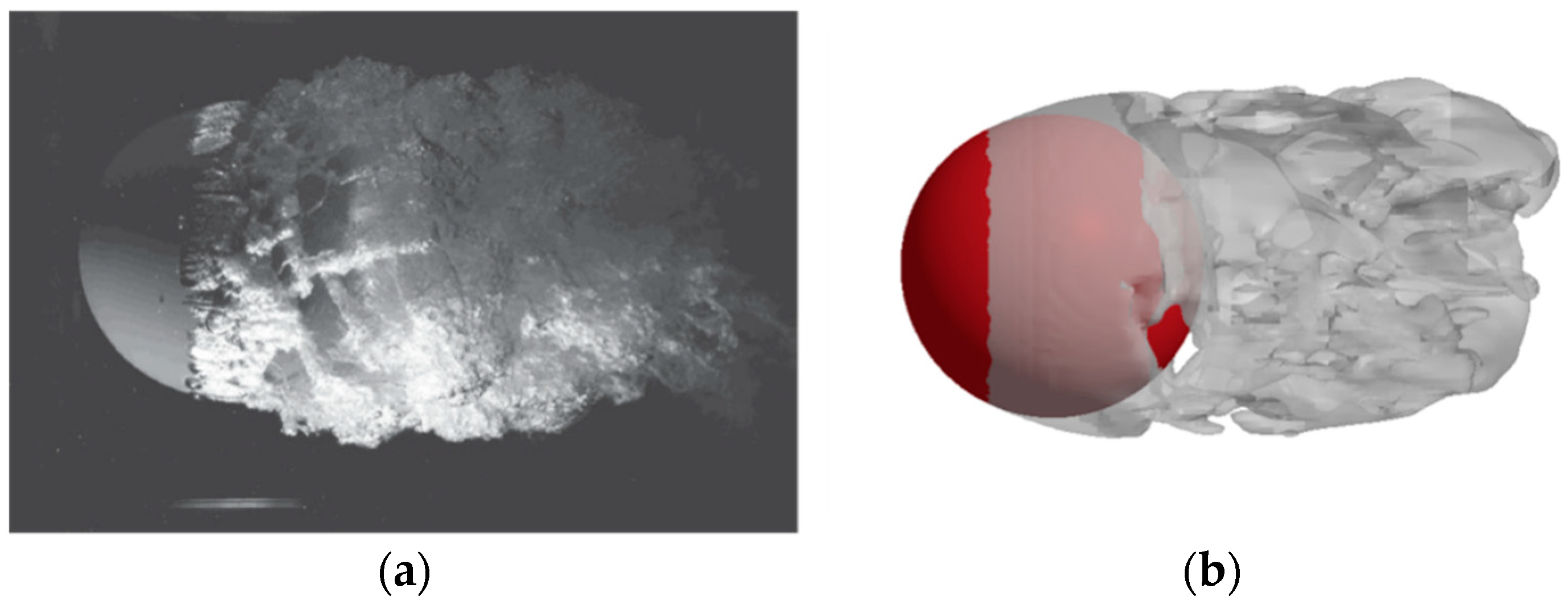

Brandner et al. (2010) [

18] analyzed the cavitation phenomenon of a sphere under high-speed flow conditions via experiments and simulations. Their study revealed the formation of cavitation nuclei and cavity shedding mechanisms, and found that changes in the cavitation number affect the formation of cavitation nuclei, gas–liquid interface instability, as well as the shedding and collapse of the cavity. Pendar and Roohi (2018) [

19] carried out numerical simulations of both cavitating and non-cavitating flows around a sphere, revealing the mechanical characteristics of cavitating flow and investigating its influence on the turbulent structures in the wake. Cheng et al. (2019) [

20] conducted numerical simulations of cavitating flow around a sphere under different cavitation numbers using the Spalart–Allmaras Detached Eddy Simulation (SA DDES) model. They identified single- and dual-frequency modes of flow instability and analyzed the causes of the dual-frequency behavior. Their study demonstrates the effectiveness of hybrid RANS-LES approaches in capturing unsteady cavitating flows, which inspired the present work to adopt the SST IDDES model for improved prediction of turbulent and cavitation structures. Long et al. (2020) [

21] performed numerical simulations of turbulent cavitating flow around a sphere, studying the relationship between cavity evolution and vortex structure development. Their work revealed the dominant flow structures under different cavitation states. Constantinescu and Squires (2004) [

22] numerically investigated the flow field around a sphere in a uniform stream, analyzing vortex structure characteristics in subcritical (laminar separation) and supercritical (turbulent separation) regimes. Kolahan et al. (2019) [

23] conducted numerical simulations of cavitating flow around a sphere, analyzing the periodic oscillations in pressure and kinetic energy. Using wavelet transforms, they investigated the origins and effects of oscillation frequencies in cavitating flows.

Finally, unsteady cavitation flow around underwater objects remains a prominent topic in the study of water exit dynamics. In this regard, Chen et al. (2021) [

24] conducted numerical simulations on projectile cavitation during water exit and revealed that bubble detachment is primarily driven by the rupture of the gas–liquid contact line. They also observed that the presence of a cavity suppresses the formation of hairpin vortices and instead induces T-S wave-like vortex structures due to interfacial shear. Sun et al. (2021) [

25] found through experiments that the evolution of unsteady natural cloud cavitation can be divided into three stages: growth, detachment, and collapse. The collapse phase is accompanied by pressure fluctuations, whose frequency and amplitude are influenced by changes in the cavitation number. Shao et al. (2018) [

26] investigated supercavitation behavior around hydrofoils, identifying five distinct cavity states: stable, wavy, pulsation mode I, pulsation mode II, and collapse. Increased flow instability led to transitions toward cavity collapse, while higher ventilation coefficients and larger cavitator sizes were found to suppress cavity collapse. Guo et al. (2011) [

27] compared ventilated cavitation and natural cavitation in high-speed underwater projectiles, finding that both the ventilated cavitation number and drag coefficient are influenced by natural cavitation characteristics and ventilation flow rate. Pendar and Roohi (2016) [

28] used various turbulence and mass transfer models to simulate cavitation around hemispherical-head bodies with conical cavitators at different cavitation numbers. Sun et al. (2021) [

29] also carried out both experimental and numerical studies on the high-speed water-entry process of rotating bodies under different angles of attack, analyzing the evolution of cavitation and hydrodynamic loads and their interrelation. Liu et al. (2023) [

30] conducted experiments on bubble size distribution (BSD) in cloud cavitation over hydrofoils, revealing mechanisms by which turbulence influences bubble dynamics. Tian et al. (2024) [

31] investigated cavitation flows around highly skewed propellers, identifying three distinct cavitation regimes and their corresponding mechanisms for inducing pressure pulsations. Wang et al. (2024) [

32] developed a novel Euler–Lagrange method for simulating unsteady cavitation around blunt bodies, which demonstrated improved accuracy over traditional Euler-Euler approaches. Cheng et al. (2020) [

33] performed numerical simulations on tip-leakage cavitation over hydrofoils, analyzing flow evolution and its influence on local turbulence.

In previous studies, Novikov and Shmel’Tser (1982) [

34] investigated the Kirchhoff equations for rigid body motion in an ideal incompressible fluid using topological and variational methods, focusing on the existence of periodic solutions, the number of orbits, and their symmetry properties. Ershkov et al. (2020) [

35] proposed an analytical approximation method, transforming the momentum equations of the Kelvin–Kirchhoff equations into a system of first-order linear ordinary differential equations and further relating it to the corresponding homogeneous system and Riccati equations. Although this approach yielded concise particular solutions, it could not provide general analytical solutions under typical fluid forces. Miloh and Landweber (1981) [

36] extended the classical Kelvin–Kirchhoff equations to account for fixed boundary conditions, deriving generalized three-dimensional motion equations and revealing new relationships between the direction cosines of the body axis and the kinematic parameters of angular motion.

Chashechkin (2022) [

37] investigated wake structures behind spheres in stratified fluids using shadowgraphy and electrolytic precipitation. He found that low Froude numbers produce prismatic wakes with discrete symmetry due to buoyancy, while high Froude numbers yield axisymmetric wakes dominated by inertia and nonlinear effects. Interfacial ligaments were shown to play a key role in stratification effects and vortex evolution. Chashechkin and Levitskiy (2003) [

38] Levitskiy examined neutrally buoyant spheres oscillating near their buoyancy plane using shadowgraph visualization. The flow featured wakes, boundary layers, and internal waves, with high-energy secondary jets forming near trajectory turning points. These jets grow with oscillation cycles and reduce the decay rate of the sphere’s oscillation amplitude.

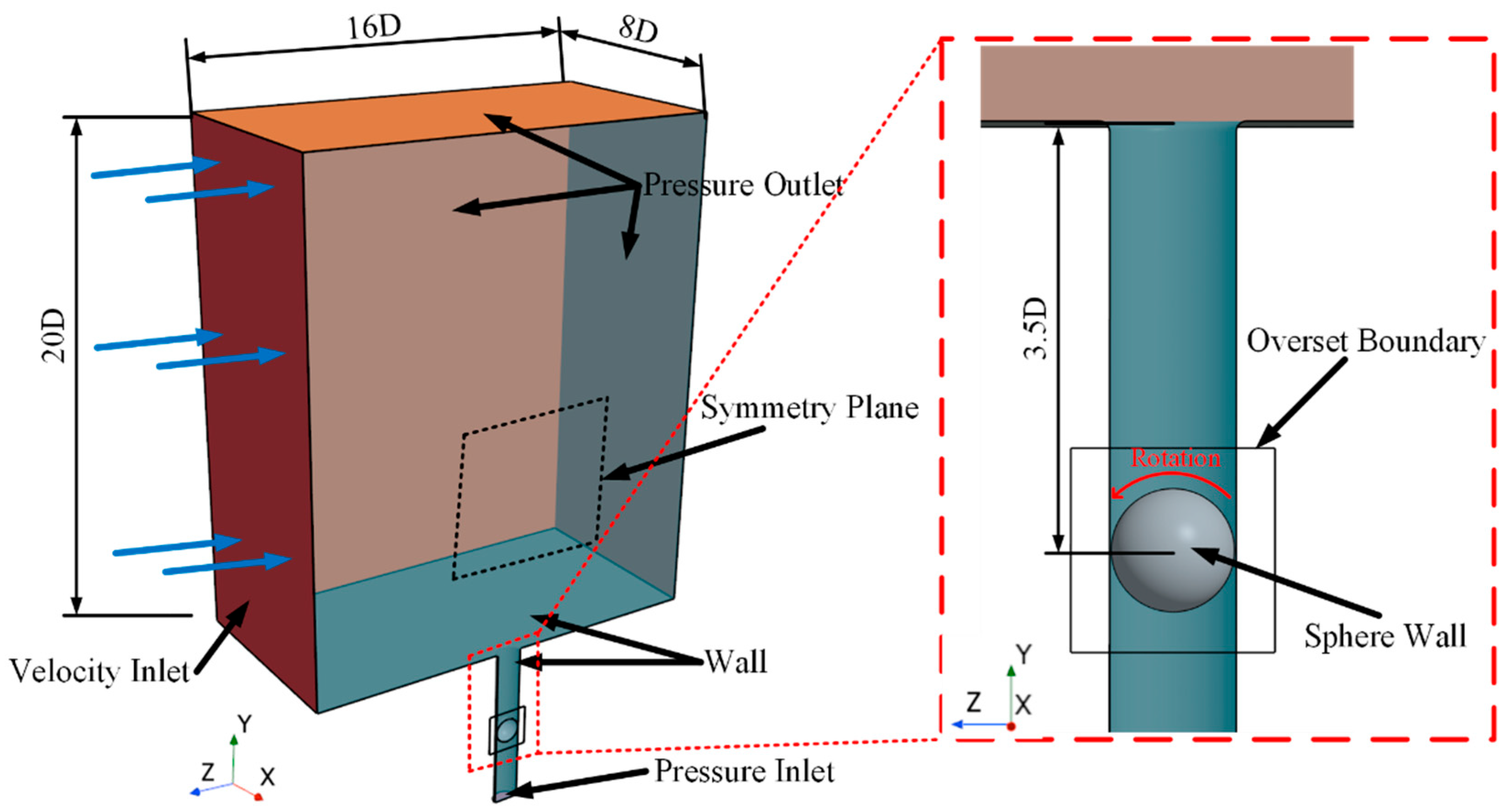

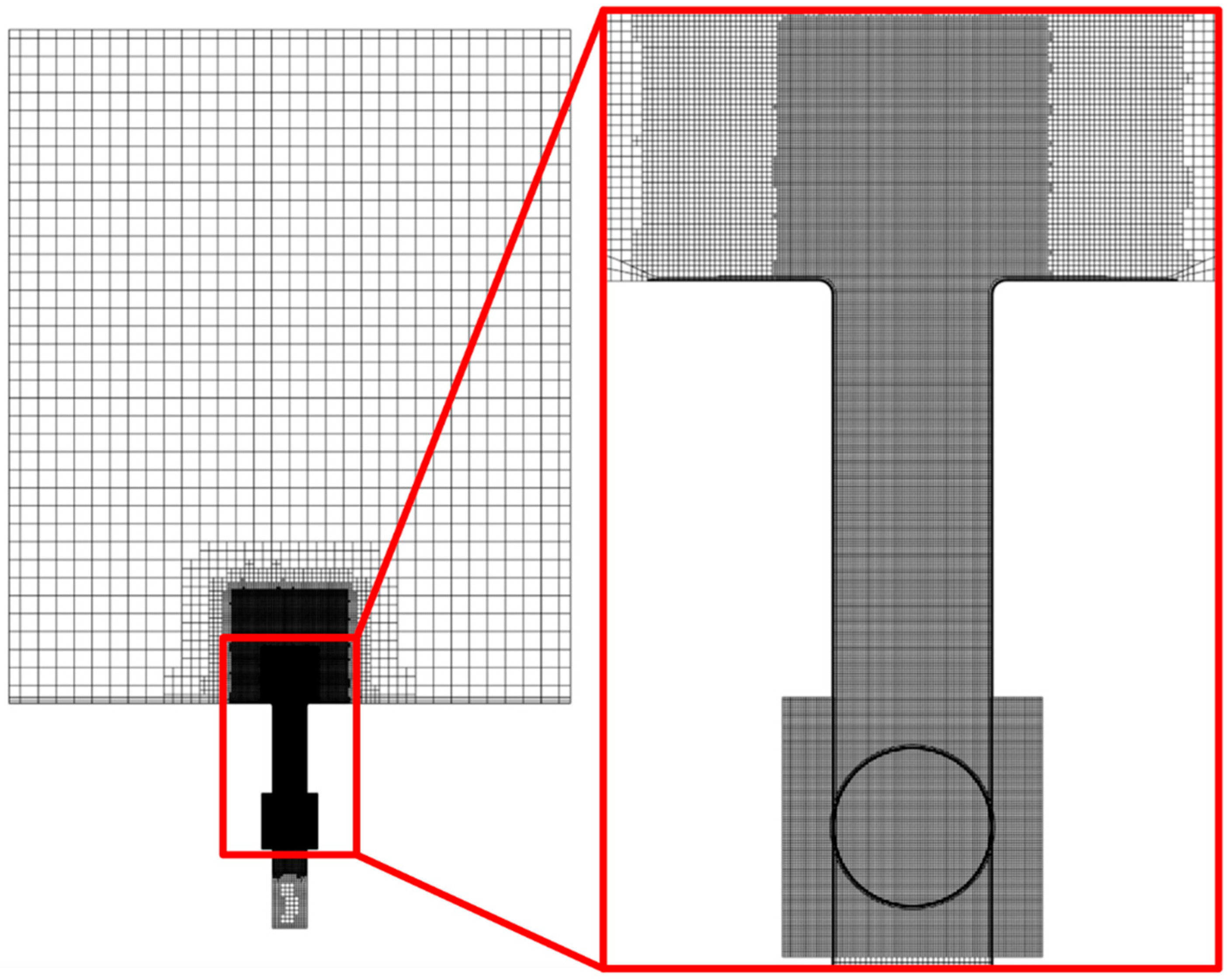

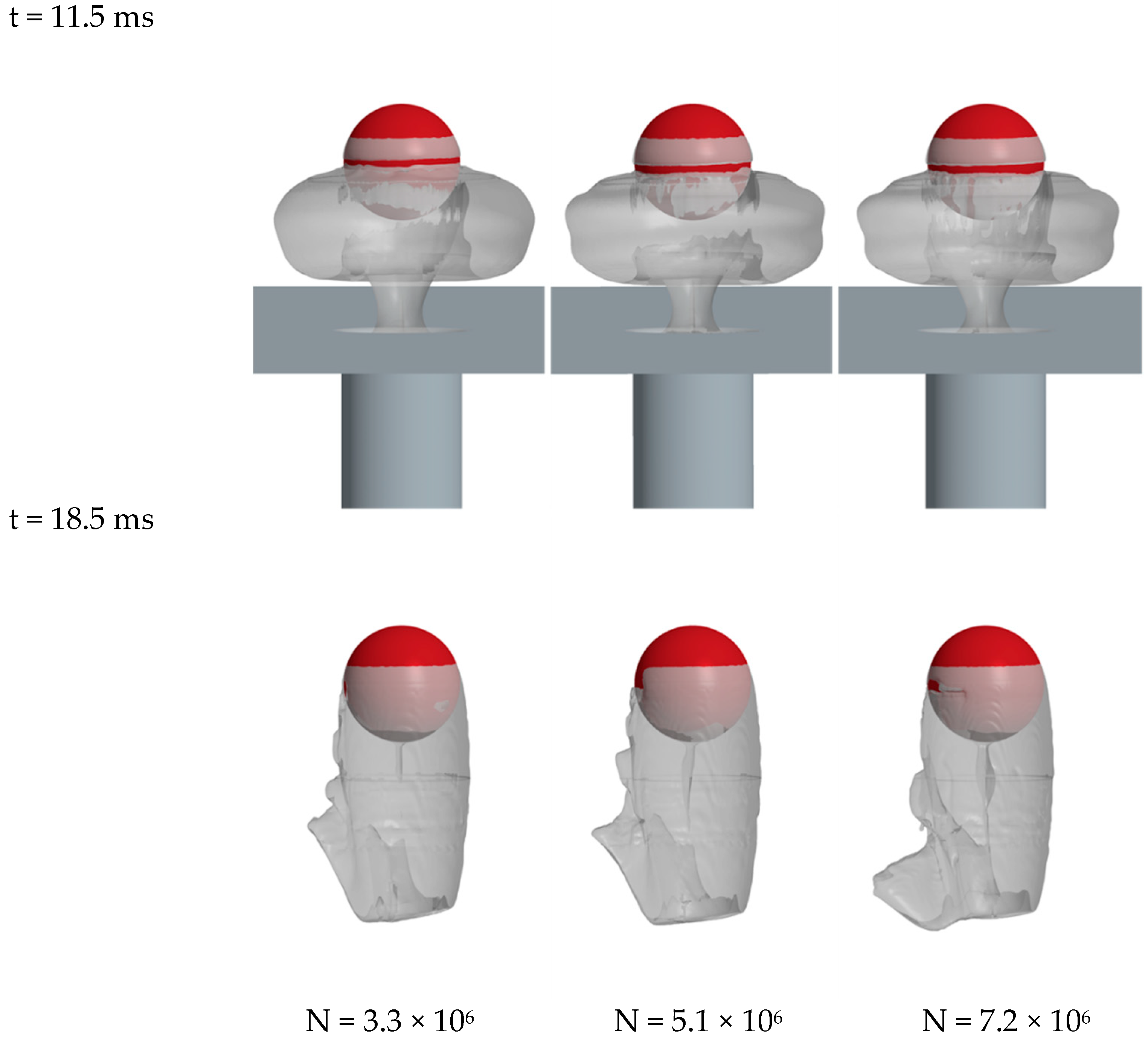

Notably, these studies primarily focus on analytical methods and theoretical extensions, or on idealized conditions with high symmetry. The dynamics of rigid bodies in complex, realistic fluid environments—particularly the nonlinear response of a sphere during underwater rotational launch—remain insufficiently explored through systematic numerical simulation. To address this gap, the present study employs a CFD-based numerical approach implemented in STAR-CCM+ v2302, incorporating six-degree-of-freedom rigid body motion equations and turbulence models to simulate fluid–structure interactions during the rotational launch of a sphere. This method not only captures transient mechanical features of the rotational motion but also allows analysis of the evolution of detailed flow structures, providing numerical validation for theoretical analyses.

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Flow Evolution and Loading on the Sphere

In this section, we conduct a comparative analysis of the sphere’s ejection process under stationary ejection (SE) and rotating ejection (RE) conditions, where the angular velocity in the RE case is set to .

As illustrated in

Figure 7, the sphere initially undergoes a confined in-tube motion stage, during which it remains entirely inside the launch tube and has not yet entered the external water domain. In this phase, the sphere continuously accelerates, and in the rotating case, its angular velocity increases accordingly.

It is first observed that near the rear region of the sphere, adjacent to the tube wall, the presence of a wall-normal velocity component on the sphere’s surface—opposing the direction of the surrounding fluid—induces liquid stretching and results in a local pressure drop below the vapor pressure of water. This triggers cavitation, forming a two-phase structure characterized by a gas region near the tube wall and a liquid core at the center.

Under SE conditions, this cavity structure maintains approximate front-rear symmetry during its development. In contrast, under RE conditions, shear induced by the rotating sphere surface disrupts the symmetric distribution, causing the structure to deflect toward the rear side in the direction of rotation. Additionally, the liquid near the upper surface of the sphere is compressed by its motion and is ejected at high speed along the tube wall. This high-speed outflow generates a ring-shaped vortex cavitation (VC) structure at the tube exit. As the sphere approaches this cavitation ring, the VC is further disturbed by the advancing sphere under RE conditions.

Subsequently, the sphere reaches the tube exit and enters the out-of-tube stage. During this stage, the presence of VC at the nozzle causes the sphere to immediately pass through the cavitation region upon exiting the tube. In other words, the sphere penetrates directly through the annular VC located at the nozzle. In this process, it is observed that due to the sphere’s rotation, the VC at the rear evolves differently under the influence of the sphere’s surface motion.

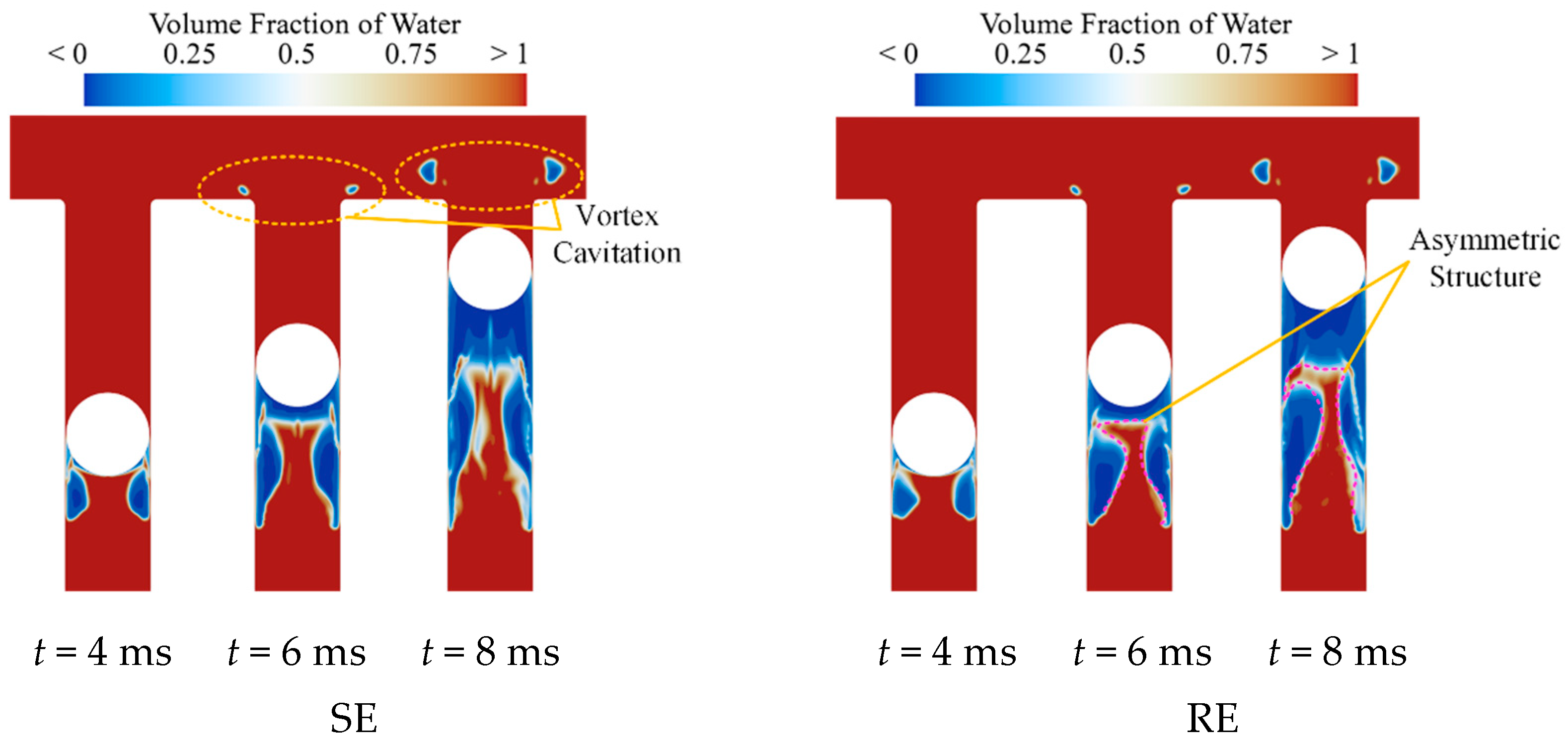

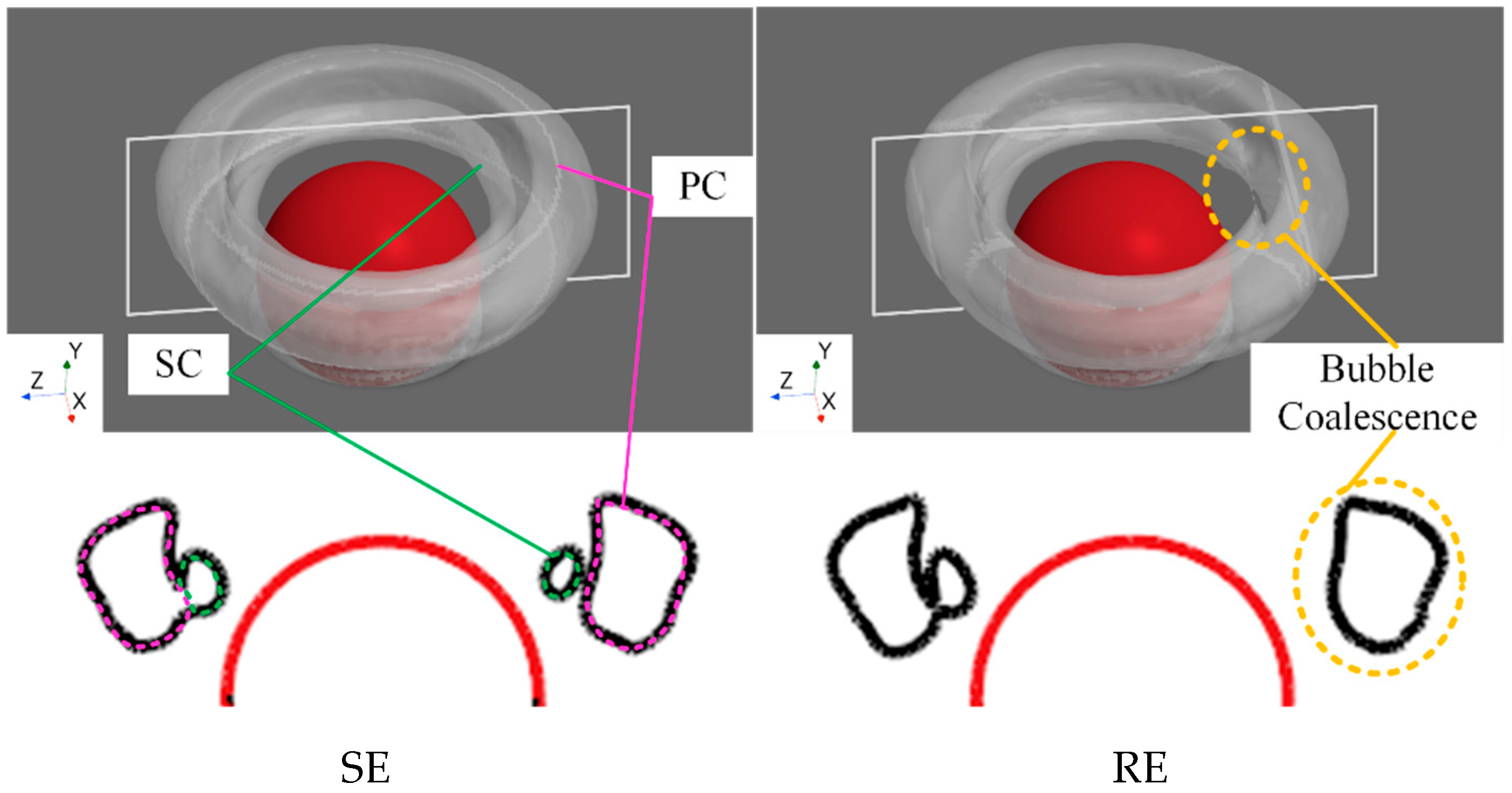

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 presents the cavity contour along the central cross-section through the sphere at

t = 9.5 ms, just before exiting the tube, along with the vortex structure at the nozzle indicated by the Q-criterion (

Q = 100/s).

The

-criterion is used to identify vortex structures in a flow and is defined as

where

is the antisymmetric part of the velocity gradient tensor, representing the local rotation rate of the fluid, and

is the symmetric part, representing the local rate of strain.

From the figure, it can be seen that the annular cavity at the tube exit is composed of a large primary cavity (PC) and several subsequently generated smaller secondary cavities (SC). These SC progressively merge with the PC to form the overall vortex cavity structure. At the observed moment, compared to the approximately symmetric PC–SC configuration under SE conditions, the PC and SC under RE conditions exhibit clear asymmetry. Specifically, some SCs on the rear side merge directly with the PC during development. This phenomenon arises because the annular cavity at the nozzle is induced by vortex cavitation, with corresponding primary vortices (PV) and secondary vortices (SV) associated with the PC and SC, respectively. Under RE conditions, the flow on the front side of the sphere is opposite to the direction of the sphere’s rotation, while the flow on the rear side aligns with it. This results in an increased flow velocity near the rear side of the sphere, promoting earlier vortex merging. Consequently, the cavitation induced by the SV fuses with that of the PV at an earlier stage. The profile of the cavity intuitively shows the difference between the SE and RE.

Figure 10 shows the gas–liquid two-phase distribution at t = 11.2 ms, when the sphere has just passed through the annular cavity at the nozzle and is about to experience cavitation on its surface. Compared to the SE case, the interface between the sphere surface and the annular cavity under RE conditions is no longer perfectly symmetric. Due to the sphere’s rotation, the flow on the front side of the sphere moves downward, causing water to adhere to the sphere and flow into the sphere–cavity interface region from above. This interaction forms a concave structure at the interface. In contrast, on the rear side of the sphere, the fluid is carried upward by the rotating surface, lifting the cavity upward and forming a convex structure.

In addition, at this moment, the tail cavity (TC) of the sphere has not yet fully merged with the annular cavity at the nozzle. Under SE conditions, a clear liquid layer remains between the two cavities. Owing to the initial crossflow, the annular cavity at the nozzle slightly shifts toward the rear side, resulting in a thicker liquid layer on that side. Under RE conditions, however, the high-speed shear effect induced by the rotating sphere surface disturbs the liquid layer, preventing its stable presence. Instead, the liquid shows a tendency to spread and drift in the direction of sphere rotation, indicating the destabilization and redistribution of the intermediate liquid layer due to rotational influence.

The differences at the gas–liquid interface between the cavity and the sphere surface result in distinct cavitation developments after onset.

Figure 11 presents the phase distributions at

t = 11.7 ms, when cavitation first appears on the sphere surface, and at

t = 12.4 ms, when the surface cavity merges with the annular VC near the nozzle.

It is observed that, under RE, cavitation initiates on the rear side of the sphere where the convex gas–liquid interface is already influenced by upward-moving water vapor carried by rotation. This causes the shoulder cavitation (SC) on the rear side to merge earlier with the VC. In contrast, on the front side, the SC remains clearly separated from the VC. As the process evolves, the concave interface at the front becomes increasingly pronounced, resulting in delayed merging between the SC and the VC. Additionally, at the bottom of the sphere, necking and detachment occur between the TC attached to the sphere’s tail and the cavity inside the tube. The TC subsequently merges with the VC at the nozzle.

Eventually, as the ejection process continues, the cavity undergoes successive cycles of collapse and re-expansion, forming a pattern of oscillations with gradually decreasing amplitude.

Figure 12 illustrates the evolution of cavity volume during the launch, showing that the sphere experiences multiple cavitation–collapse–re-cavitation cycles throughout its motion. It can be observed that the effect of rotation becomes more pronounced during the second and subsequent cavitation-collapse events. As discussed earlier, rotation alters the development of the backward jet flow near the sphere’s bottom. This variation in jet flow directly affects the behavior of the TC, causing discrepancies in the location and timing of cavity collapse at the bottom. Consequently, this leads to differences in the volume and evolution of the secondary and tertiary cavitation events between SE and RE conditions.

During the ejection process, the forces acting on the sphere and its motion are also influenced by both the sphere’s rotation and the differences in cavity evolution induced by this rotation.

Figure 13 presents the pressure distribution on the sphere’s surface throughout the launch. In the early stage of cavitating flow, the impact of rotation on the pressure distribution is not yet significant. This is because the primary pressure variation across the sphere is caused by the high-pressure stagnation point at the top and the low-pressure cavitating region, which are both mainly governed by the translational motion of the sphere. As noted previously, before the initial cavity collapse, rotation has limited influence on cavitation, and thus the pressure distribution under SE and RE conditions remains similar during this phase.

Subsequently, at

t = 19 ms, a high-pressure region appears at the front side of the sphere. For the SE case, this high-pressure region results primarily from the early wetting of the front surface, as described earlier, and is mostly distributed around the 0° latitude area. In contrast, for the RE case, the high pressure is mainly caused by the direct impact of the re-entrant jet on the sphere surface. Consequently, the high-pressure zone shifts downward, primarily located below 0° latitude.

Figure 13 illustrates the pressure distribution at this moment, where extensive high-pressure regions emerge over the surface, especially concentrated near the bottom, the front side, and the original cavitation generation site. A comparison of the pressure distributions under SE and RE conditions reveals distinct differences, which are primarily attributed to the previously described disparities in cavity morphology. These morphological differences lead to varying pressure patterns on the sphere surface during subsequent cavity collapses.

Figure 14 shows the pressure distribution along the circumference of the sphere’s cross-section on the symmetric plane at

t = 14 ms and

t = 45 ms, comparing the front and back sides of the surface. It can be observed that during the cavitating flow stage, the rotation of the sphere has no significant effect on the pressure distribution along its surface. On both the front and back sides, the surface pressure consistently transitions from a high-pressure region near the sphere’s nose to a low-pressure region near the shoulder. The pressure reaches its minimum at the cavitation onset location. Within the cavity, the pressure remains nearly uniform, and the pressure profiles under both SE and RE conditions are nearly identical.

However, during the non-cavitating flow stage, distinct differences arise in surface pressure distribution. Under SE conditions, the pressure on both sides of the upper portion of the sphere remains largely symmetrical. Toward the tail, pressure differences and fluctuations begin to emerge due to the collapse of the previous cavity and the development of an asymmetric vortex structure near the TC. Under RE conditions, asymmetry appears even in the upper region of the sphere. Specifically, the pressure on the back side is higher than on the front side, which results from the relative motion between the rotating sphere surface and the surrounding flow—on the back side, the surface moves opposite to the ambient flow, generating higher pressure due to the reverse-flow interaction. Near the bottom region of the sphere, the effects of previous cavity collapse and the shedding of tail vortex structures also introduce significant pressure fluctuations, leading to notable differences in pressure distribution between the two sides.

Figure 15 illustrates the motion characteristics of the sphere throughout the entire ejection process. In

Figure 15a, the post-ejection trajectory of the sphere is shown. Overall, the sphere deviates toward the back side after exiting the launch tube due to disturbances caused by the initial crossflow. As previously discussed, under RE conditions, the front side of the sphere is affected by the re-entrant flow earlier, which leads to an earlier detachment and collapse of the cavity. This results in a more pronounced force asymmetry between the front and back sides of the sphere compared to SE conditions, thereby causing a more significant deflection in the trajectory.

Figure 15b presents the time histories of the sphere’s velocity and acceleration during the ejection process. It is evident that the sphere undergoes two major accelerative phases, each corresponding to the collapse of a cavity as shown in

Figure 15. These collapses, particularly at the TC, generate instantaneous high-pressure zones that induce a sudden upward impact force on the sphere. Comparing the SE and RE cases, a significant difference in acceleration profiles is observed. This discrepancy is primarily attributed to the previously described differences in cavity evolution. However, After the first cavitation collapse, the velocity profiles of the two cases gradually diverge, with the velocity under RE conditions decreasing below that of the SE case and the difference progressively increasing. At the time of the second collapse, the velocities in both cases return to a similar level. Subsequently, the velocity under RE conditions decreases more rapidly again, and the difference with the SE case further widens.

4.2. Reentrant Jet and Flow Separation

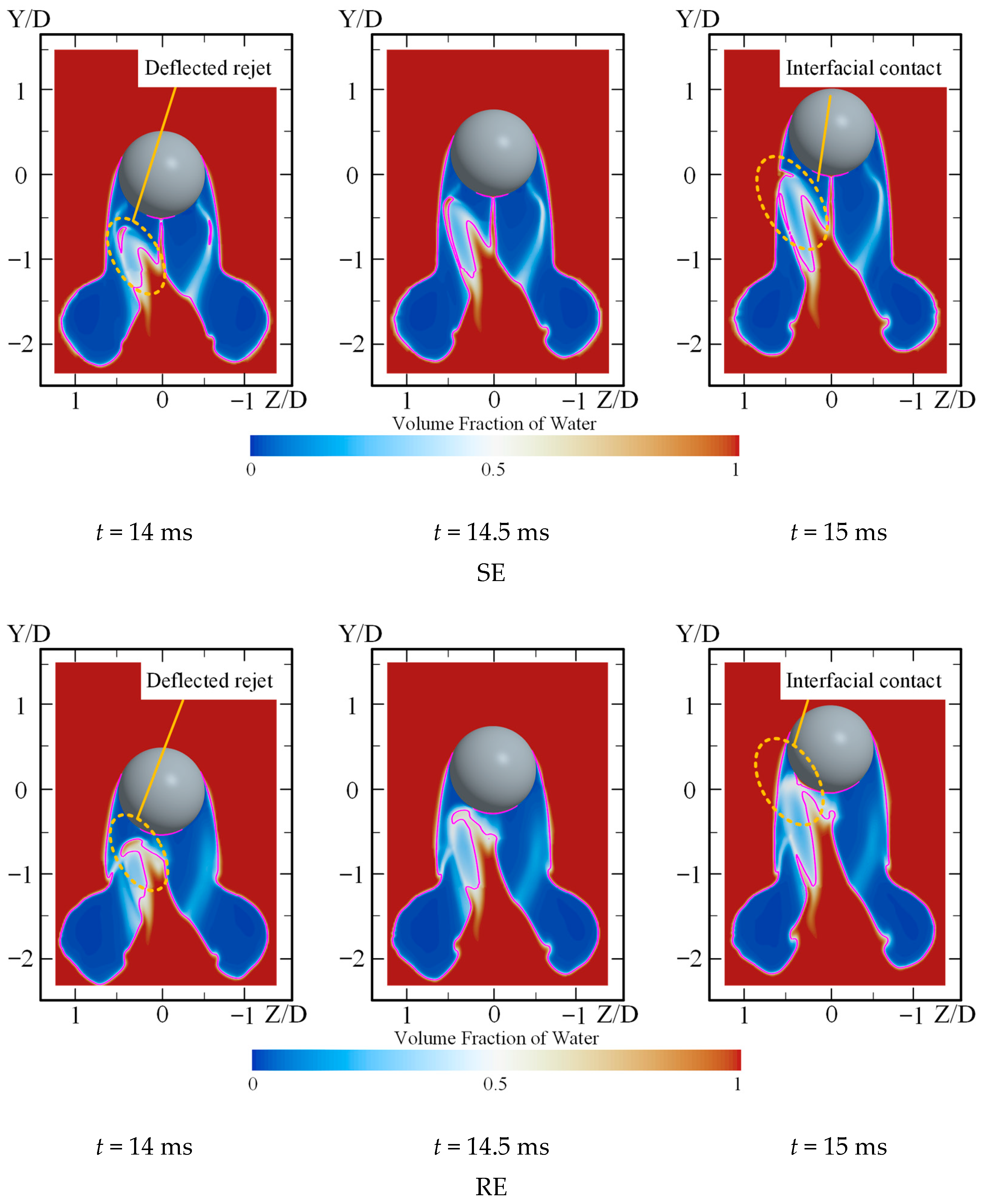

Figure 16 illustrates the moment at

t = 13.5 ms, when the sphere passes through the annular cavity at the nozzle and enters the underwater cavitating navigation stage. During this phase, cavitation and flow separation begin to occur on the sphere surface. It is observed that the cavitation onset location on the sphere surface differs from the point of flow separation. Specifically, the flow separation point appears downstream of the cavitation initiation location. By comparing the cavitation and separation locations under SE and RE conditions, it is found that the rotational motion of the sphere has little influence on the cavitation onset location. However, the position of the flow separation point exhibits a significant difference. When the sphere rotates, due to viscous effects, the surrounding fluid is entrained by the sphere surface at the same angular velocity. As a result, on the rear side of the sphere, the circumferential velocity adds to the freestream velocity, accelerating the local flow. On the front side, the circumferential velocity opposes the freestream, leading to a reduced total flow velocity. This velocity distribution causes the flow separation point on the front side to shift significantly downward, while the rear-side separation point experiences only a slight upward shift due to the influence of the gas–liquid interface.

The underwater motion of the sphere is a dynamic process that involves several distinct flow regimes, including cavitating flow, cavity collapse, secondary cavity expansion, and fully wetted flow. Each stage possesses unique flow characteristics. Particularly during cavity collapse and subsequent expansion, which involve violent phase transitions, the rapid pressure fluctuations can unpredictably disturb the local flow field.

Furthermore, due to the gradual variation in cross-sectional radius along the rotational axis of the sphere, the surface velocity is not uniform under a constant angular velocity, resulting in spatial differences in flow speed and distribution across the sphere surface.

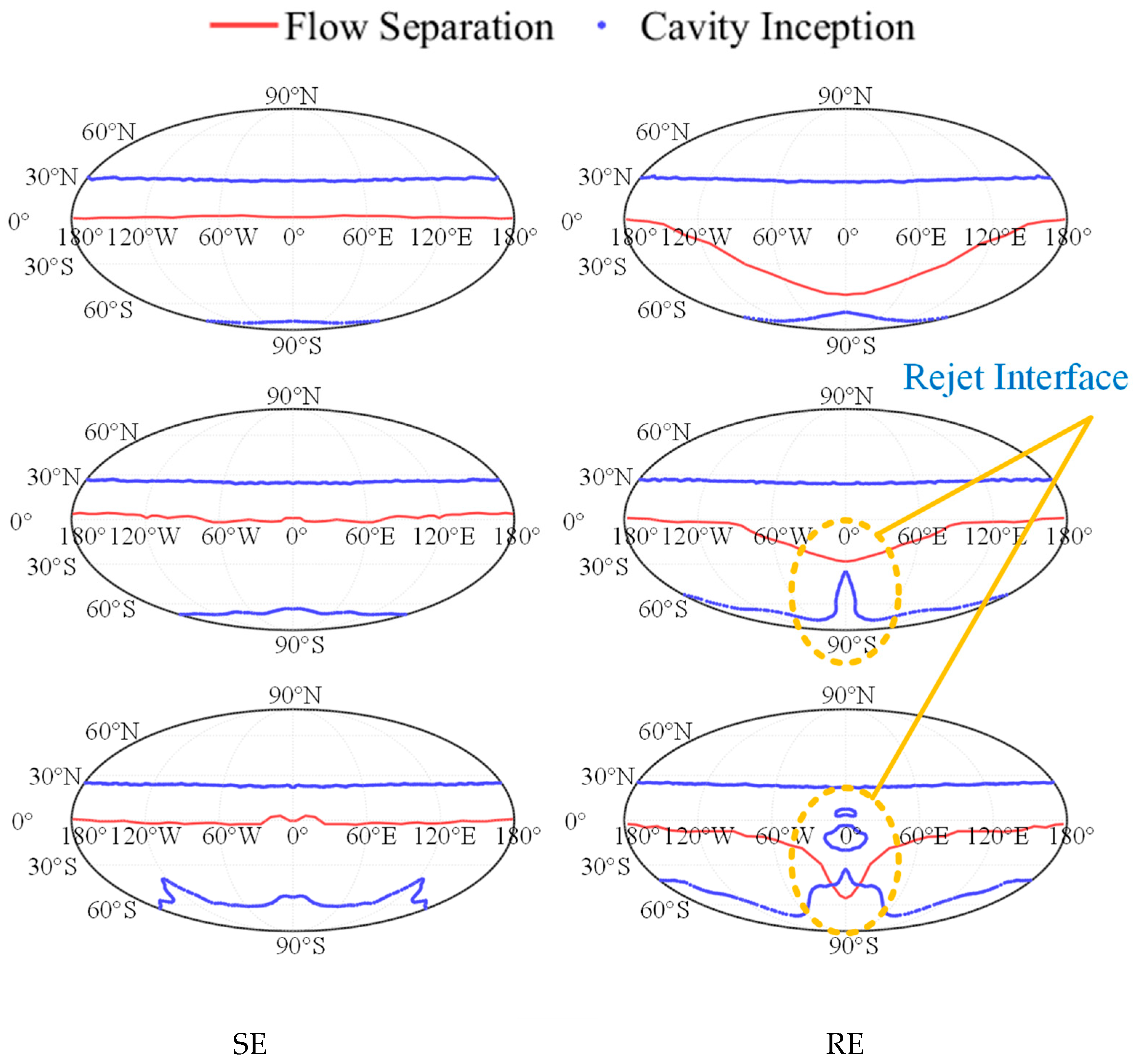

Figure 17 shows the spatial distribution of cavitation inception and flow separation points on the sphere surface under SE and RE conditions during the cavitating phase. Analysis at

t = 14 ms and

t = 14.5 ms (representing the cavitating flow stage) reveals that the cavitation inception consistently occurs at approximately 28°, regardless of rotation. This indicates that rotation has minimal influence on the cavitation onset location on the sphere surface.

In contrast, the flow separation behavior is notably affected by rotation. Under SE conditions, the separation point location remains relatively uniform across the surface. However, in the RE case, the separation point on the front side of the sphere shifts significantly downward, while the lateral displacement of the separation point gradually decreases toward the rear side, eventually aligning with the SE condition. At t = 15 ms, as discussed in the previous section, the re-entrant jet originating from the cavity collapse under RE conditions impinges on the gas–liquid interface near the front side of the sphere. This interaction perturbs the local flow field, making the separation point on the front side difficult to accurately identify. In contrast, under SE conditions, the front-side separation remains stable and exhibits a distribution similar to that observed at time instants A and B.

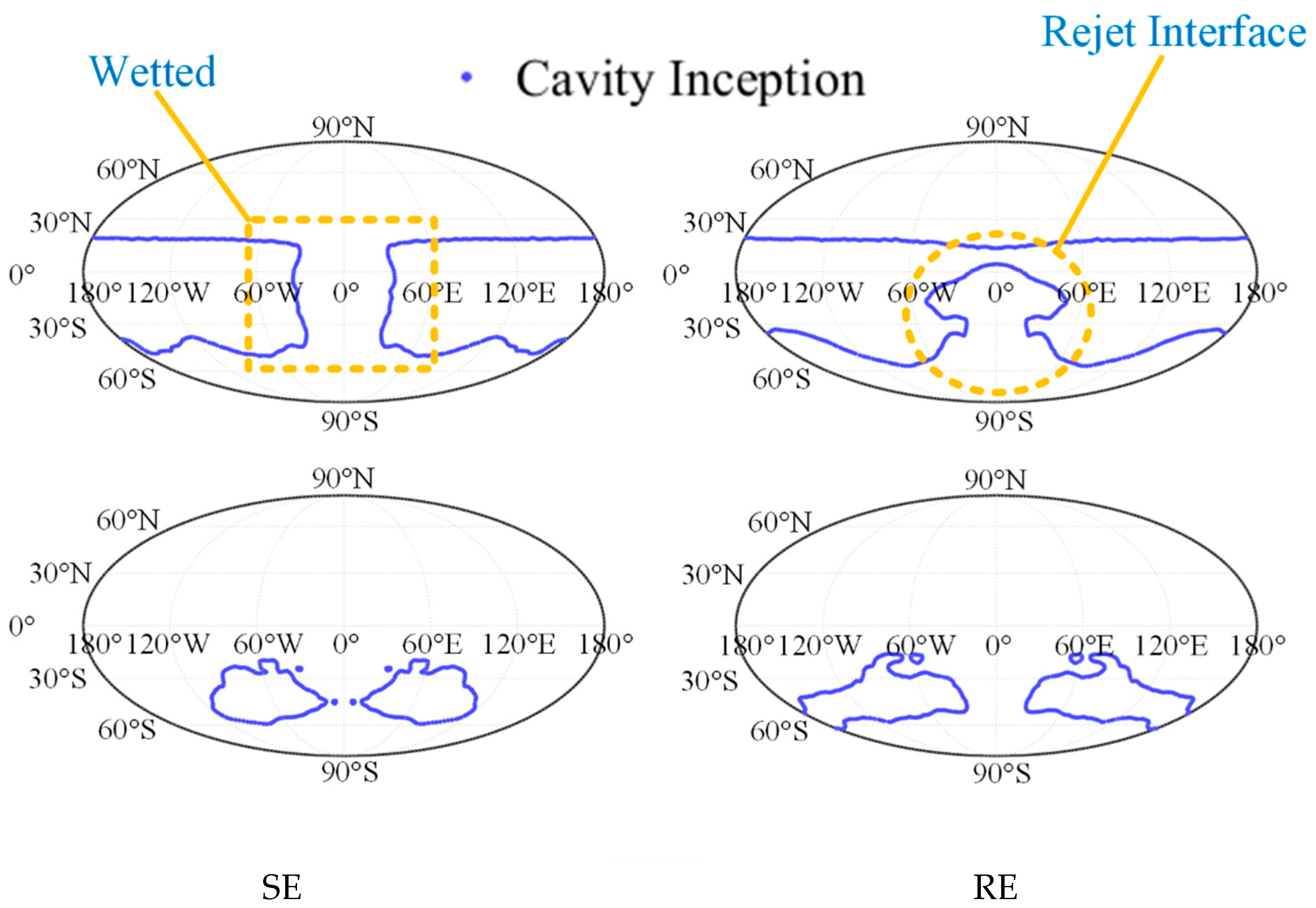

As the cavity near the sphere surface gradually collapses, the wetted area on the sphere surface undergoes significant changes. The instant of cavity collapse is typically accompanied by a sudden pressure spike, which, along with phase transition between the gas and liquid phases, leads to notable variations in the local flow velocity and direction around the sphere.

Figure 18 illustrates the distribution of the gas–liquid interface on the sphere surface during the cavity collapse and subsequent secondary expansion phases. Under SE conditions, the distribution of the wetted region on the sphere surface exhibits a relatively regular pattern: due to the influence of the re-entrant jet from the cavity collapse near the bottom of the sphere, the cavity attached to the front surface is disturbed. As the process evolves, this disturbance causes the front part of the sphere surface to rewet earlier than other regions, forming a relatively organized wetted area.

In contrast, under RE conditions, the front side of the sphere is directly impacted by the reentrant jet. The cavity in this region undergoes intense disruption, resulting in a less organized and more chaotic rewetting pattern on the sphere surface. Furthermore, both the front and rear sides of the sphere lose the clearly defined flow separation zones observed earlier, making it difficult to identify specific separation points under these conditions.

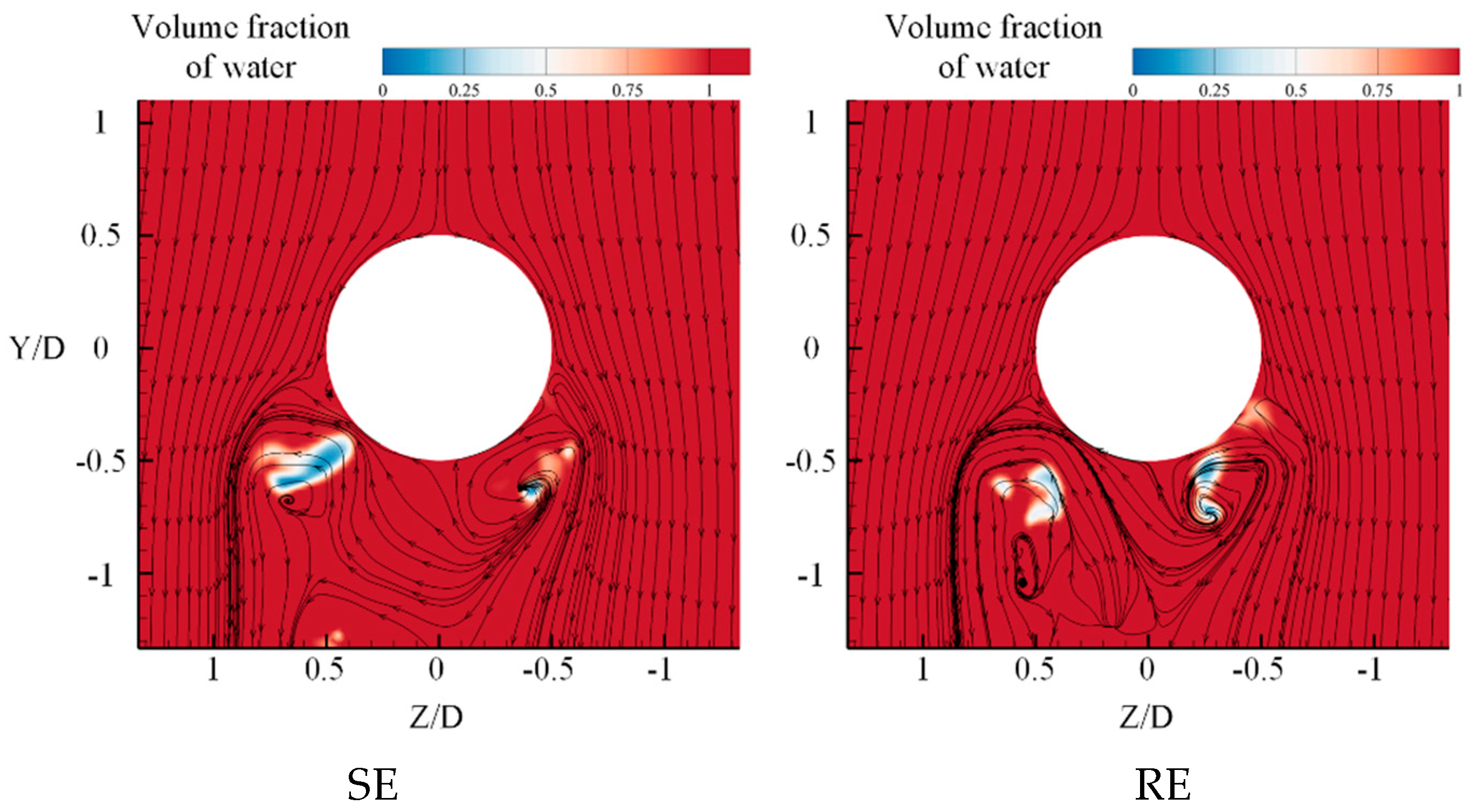

However, despite the disruption, certain phenomena in the flow field near the cross-sectional plane remain analytically significant. As shown in

Figure 19, at

t = 21 ms, a distinct rotational flow pattern emerges at the cavity collapse region under RE conditions, with evident vortex structures. Compared to the nearly symmetric flow field observed in the SE case, rotation alters the wake structure at the rear of the sphere. The vortex on the front side shifts downward along the direction of rotation.

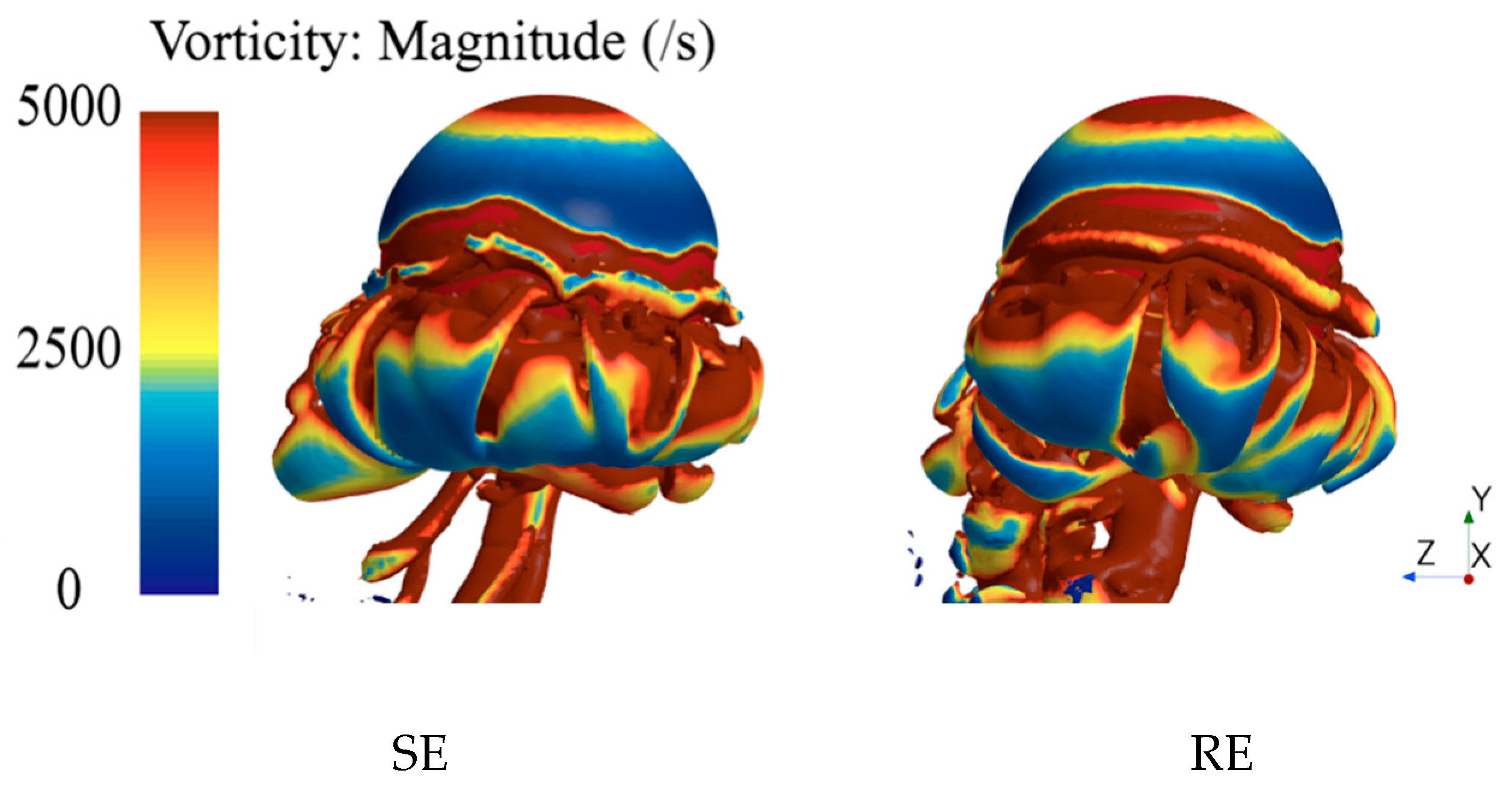

From a three-dimensional perspective (

Figure 20), unlike the relatively horizontal vortex ring seen in the SE case, the vortex ring formed under RE conditions exhibits a noticeable deformation: the front portion near the bottom of the sphere sinks, while the structure rises along the rotation axis and slightly lowers again toward the rear side, forming an asymmetric vortex ring with a left-low, right-high profile.

As the launch process progresses, the sphere moves beyond the influence of the nozzle-induced VC and enters the underwater cruising stage. During this phase, cavitation continues to develop, and the cavity elongates progressively. Collapse initiates from the TC and propagates upward, forming a jet-like structure. Simultaneously, the annular cavity near the nozzle gradually diminishes, eventually evolving into a hollow cylindrical cavity structure.

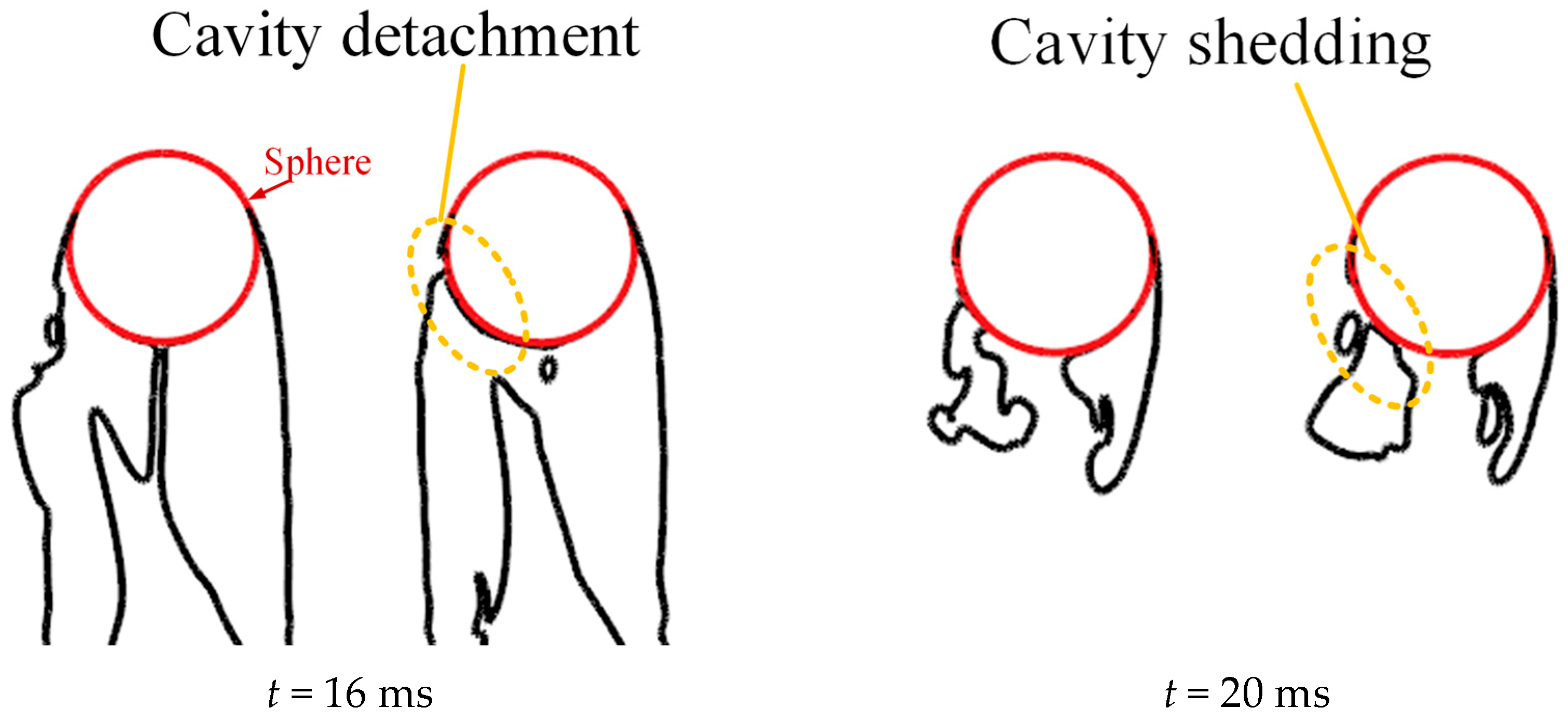

Figure 21 and

Figure 22 illustrates the evolution of the gas–liquid phase distribution during the ejection process. It can be observed that the re-entrant jet resulting from the collapse of the TC develops upward and exhibits a forward inclination trend. By

t = 15 ms, the re-entrant jet comes into contact with the cavity surface formed around the sphere, introducing disturbances to the cavity morphology.

Under SE conditions, the re-entrant jet contacts the cavity surface near the sphere’s bottom, as shown in the figure. The interaction leads to surface perturbations and slight inward deformations of the cavity but does not induce significant changes such as cavity detachment. In contrast, under RE conditions, the contact point between the re-entrant jet and the cavity shifts forward, approaching the newly formed cavity region near the front side of the sphere. This cavity is still unstable, and the impact from the re-entrant jet causes detachment between the sphere and the cavity. Moreover, due to the viscous shear generated by the rotating sphere surface, more liquid is drawn along the sphere surface into the cavity, further intensifying the separation of the front-side cavity from the sphere. Eventually, cavity detachment occurs at t = 16 ms.

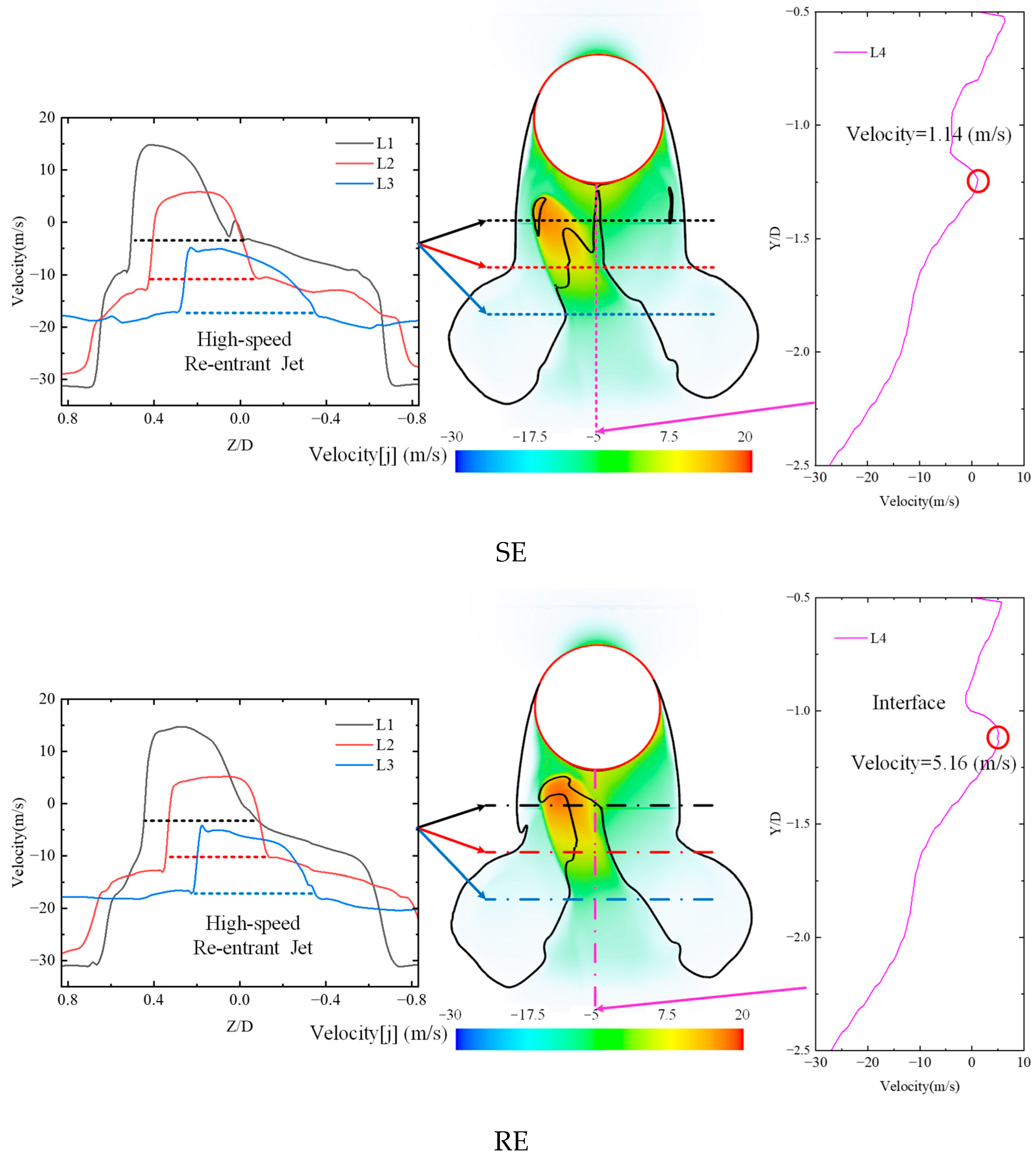

To analyze the effect of sphere rotation on the re-entrant jet near the sphere’s tail,

Figure 23 presents the vertical velocity distribution at the rear of the sphere at

t = 14 ms under both SE and RE conditions. Since the reentrant jet has not yet reached the bottom surface of the sphere at this time, the region behind the sphere contains a mixture of liquid water and water vapor. From the figure, it can be observed that the flow velocity of water vapor in the wake region decreases with increasing distance from the sphere surface. In contrast, the velocity of the reentrant liquid water is higher than that of the water vapor. As a result, the vertical velocity at the gas–liquid interface shows a local increase, which then gradually decreases with further distance from the solid surface. Comparing the two cases, it is evident that the position of the reentrant jet differs significantly between the SE and RE conditions. Under RE conditions, the vertical extent of the re-entrant jet is greater than in the SE case, and the peak velocity of the re-entrant jet is also higher, reaching 5.16 m/s compared to 1.14 m/s under SE conditions. This indicates that sphere rotation promotes a more fully developed reentrant jet, enhancing the intensity and spatial extent of the flow in the wake region.

4.3. The Influence of Rotation Rate

This chapter analyzes the effects of different rotational angular velocities on the flow field during the launch process of the sphere under rotational conditions.

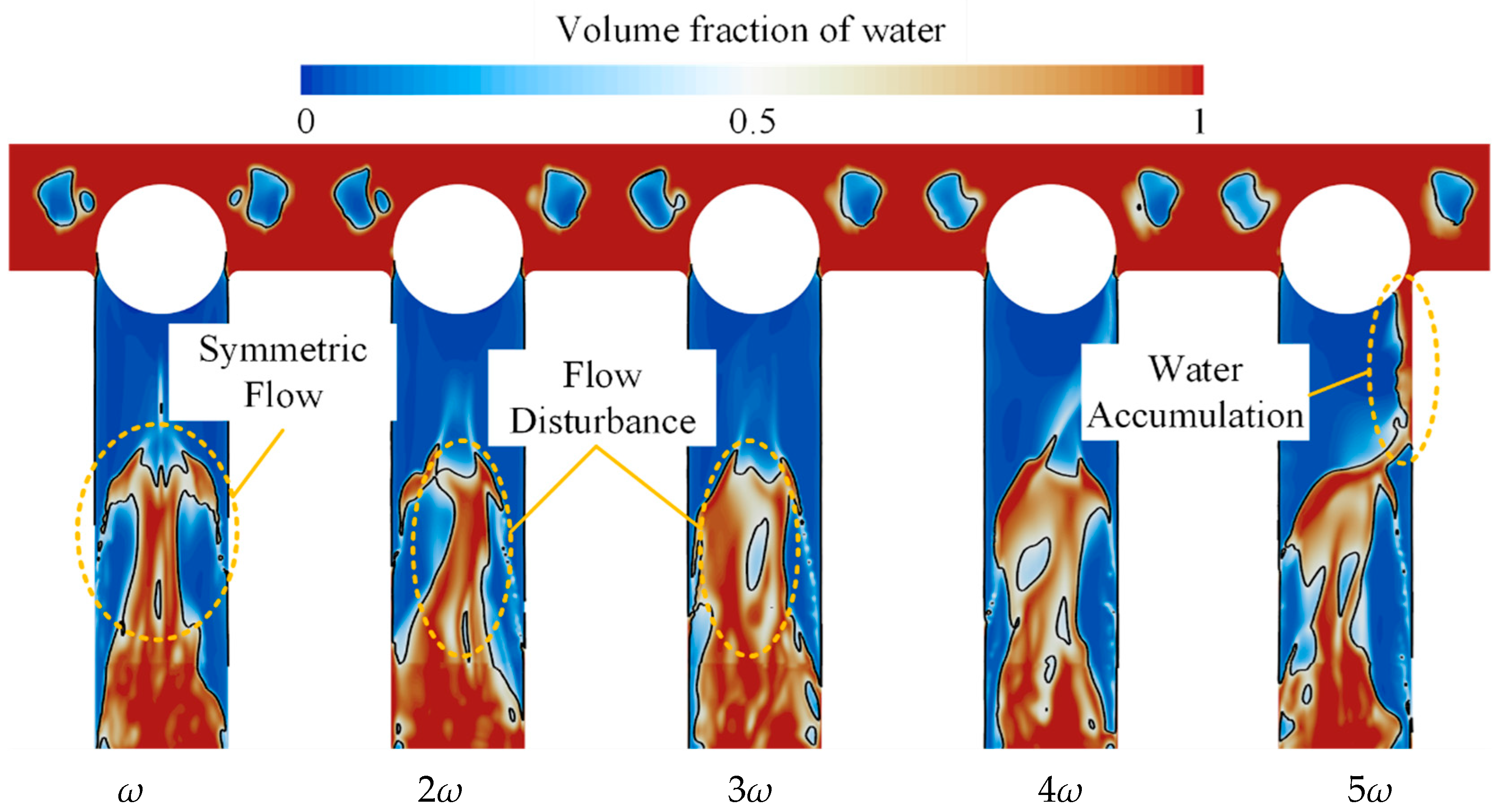

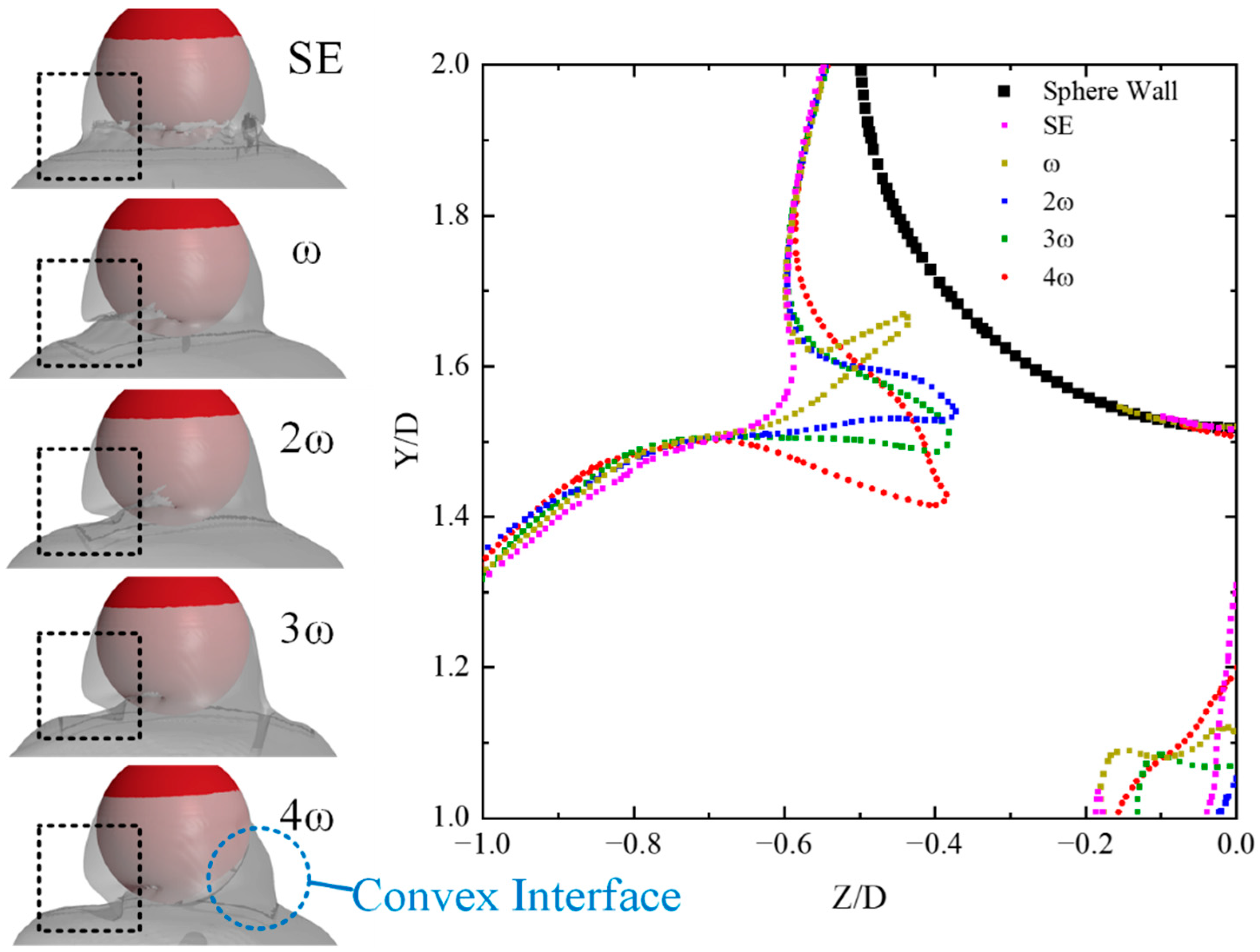

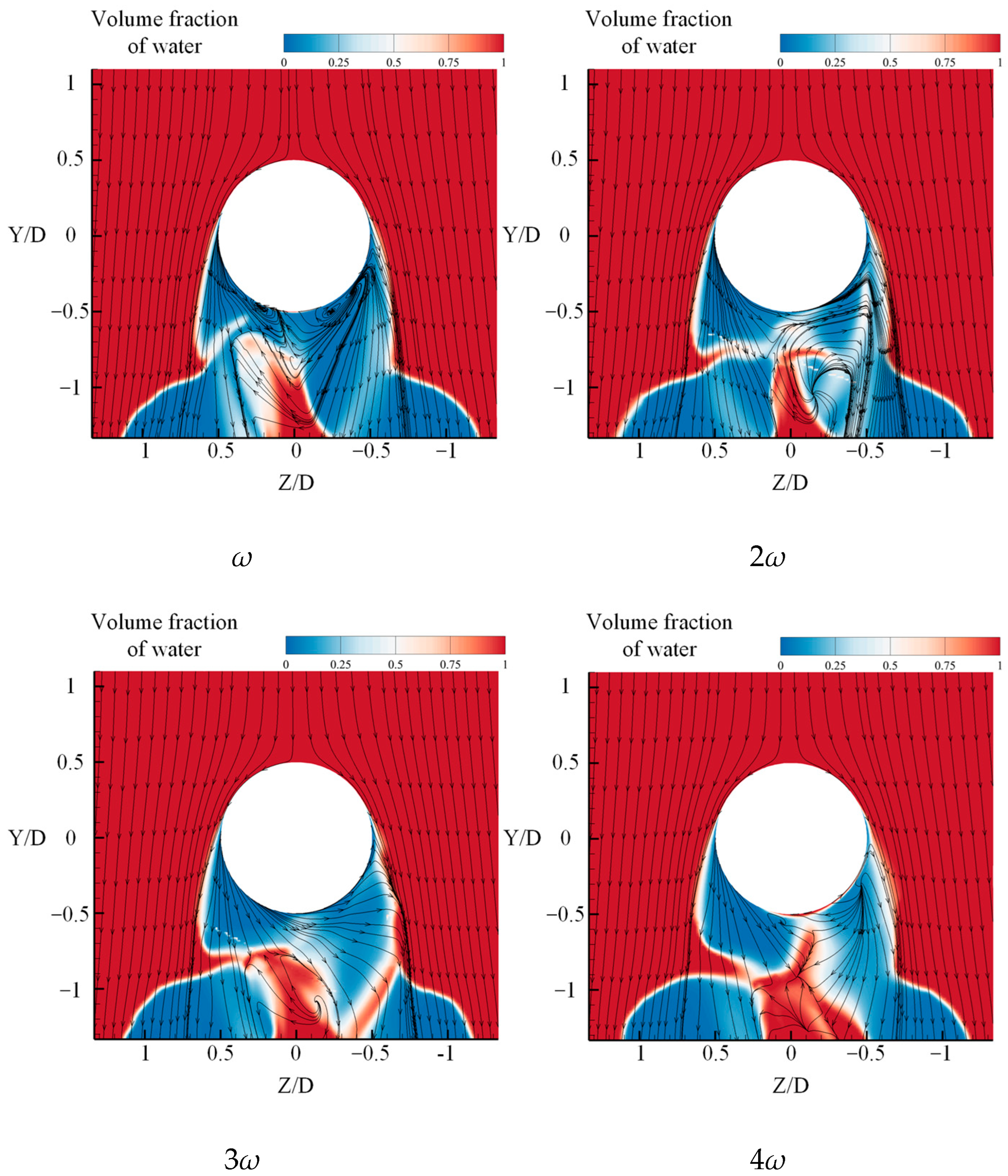

During the early stage of the launching phase, variations in rotational speed noticeably influence the cavitation behavior.

Figure 24 shows the gas–liquid phase distribution at

t = 9.5 ms under different rotational angular velocities. It can be observed that as the sphere’s rotational speed increases, the liquid inside the launch tube gradually accumulates toward the back side. When the angular speed reaches 4

ω, a significant accumulation of liquid is observed near the back side tube wall. This liquid is driven by the rotational motion toward the back wall, where it slows down upon contact with the tube wall. The resulting pressure increase in this region makes it locally higher than surrounding areas, thereby reducing the degree of phase change near this region.

Moreover, the increase in rotational angular velocity alters the development of the primary and secondary cavitation bubbles near the muzzle. As previously discussed, the nozzle cavitation bubble is formed by the merging of a primary bubble generated by the PV and a secondary bubble induced by the SV. As the rotational speed increases, the sphere’s rotation has a more pronounced effect on the vortex structures near the nozzle. At lower rotational speeds, it accelerates the merging of PC and SC on the back side. However, with further increases in rotational angular velocity, the vortex structures on both the front and rear sides become significantly disturbed, and the distinction between PV and SV becomes less apparent.

As the sphere gradually passes through the nozzle cavitation bubble,

Figure 25 illustrates the gas–liquid interface distribution at

t = 13 ms, when cavitation begins to occur on the sphere’s surface. In the previous discussion, we described how the sphere’s rotation induces a certain degree of concavity on the gas–liquid interface at the front side of the sphere. Here, we compare the concavity behavior of the interface under different rotational angular velocities. It is observed that as the rotational speed increases, the concavity at the front side of the sphere evolves accordingly. Specifically, the direction of the concave interface shifts with increasing rotational velocity. At lower angular speeds, the translational motion of the sphere dominates, causing the concave fluid to move upward along the sphere’s trajectory, resulting in a concavity biased in the direction of the sphere’s translation. However, as the rotational speed increases, the rotational velocity component becomes dominant. Consequently, the movement of the concave fluid gradually shifts from aligning with the translational motion to following the rotational direction of the sphere, causing the concave structure to deflect downward.

In addition, the rotational speed also affects the volume of the indented fluid. Higher angular velocities enhance the viscous shear effect along the sphere’s surface, driving more liquid along the rotational direction into the free surface region, thereby increasing the volume of the concave region. On the back side of the sphere, the gas phase also flows along the rotational direction due to shear effects at the wall surface. However, due to its low density and high compressibility, the gas motion has a negligible impact on the morphology of the gas–liquid interface. When the rotational speed reaches 4ω, a slight convex deformation appears at the rear-side gas–liquid interface.

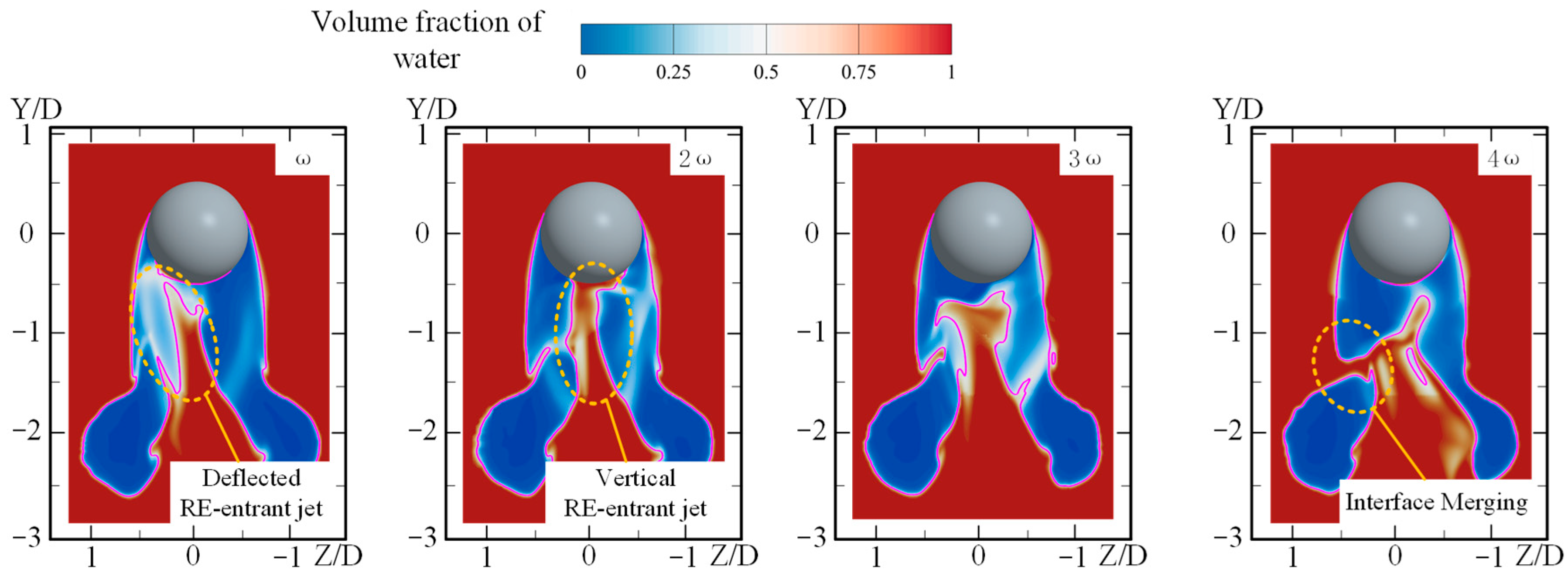

Figure 26 illustrates the variations in the morphology of the re-entrant jet at the bottom of the sphere under different rotational angular velocities. As previously discussed, the sphere’s rotation alters the deflection angle of the re-entrant jet toward the up side. In this section, we further investigate this behavior by comparing the direction of the re-entrant jet under various angular velocities to identify underlying trends.

Contrary to the initial expectation that the re-entrant jet would continue deflecting toward the rear side as the angular velocity increases, our observations reveal a more nuanced behavior. When the angular velocity increases to 2ω, the development of the re-entrant jet reaches its maximum extent, with the jet directly impinging on the bottom surface of the sphere. At this point, the re-entrant jet is most fully developed. However, as the angular velocity continues to increase beyond 2ω, the re-entrant jet becomes less developed. Analysis of the free surface evolution over time shows that this phenomenon is related to the increasingly pronounced concavity at the free surface, as discussed earlier. When the angular velocity exceeds 2ω, interactions begin to occur between the inward-flowing liquid—induced by the concave free surface—and the re-entrant jet.

At 3ω, these two flows begin to interact slightly, with the inward liquid flow interfering with the progression of the re-entrant jet, thereby reducing its development compared to the case at 2ω. When the angular velocity reaches 4ω, this interaction intensifies significantly, resulting in a direct connection between the inward liquid flow and the re-entrant jet. This leads to localized cavitation collapse near the point of interaction, which severely inhibits the further development of the re-entrant jet.

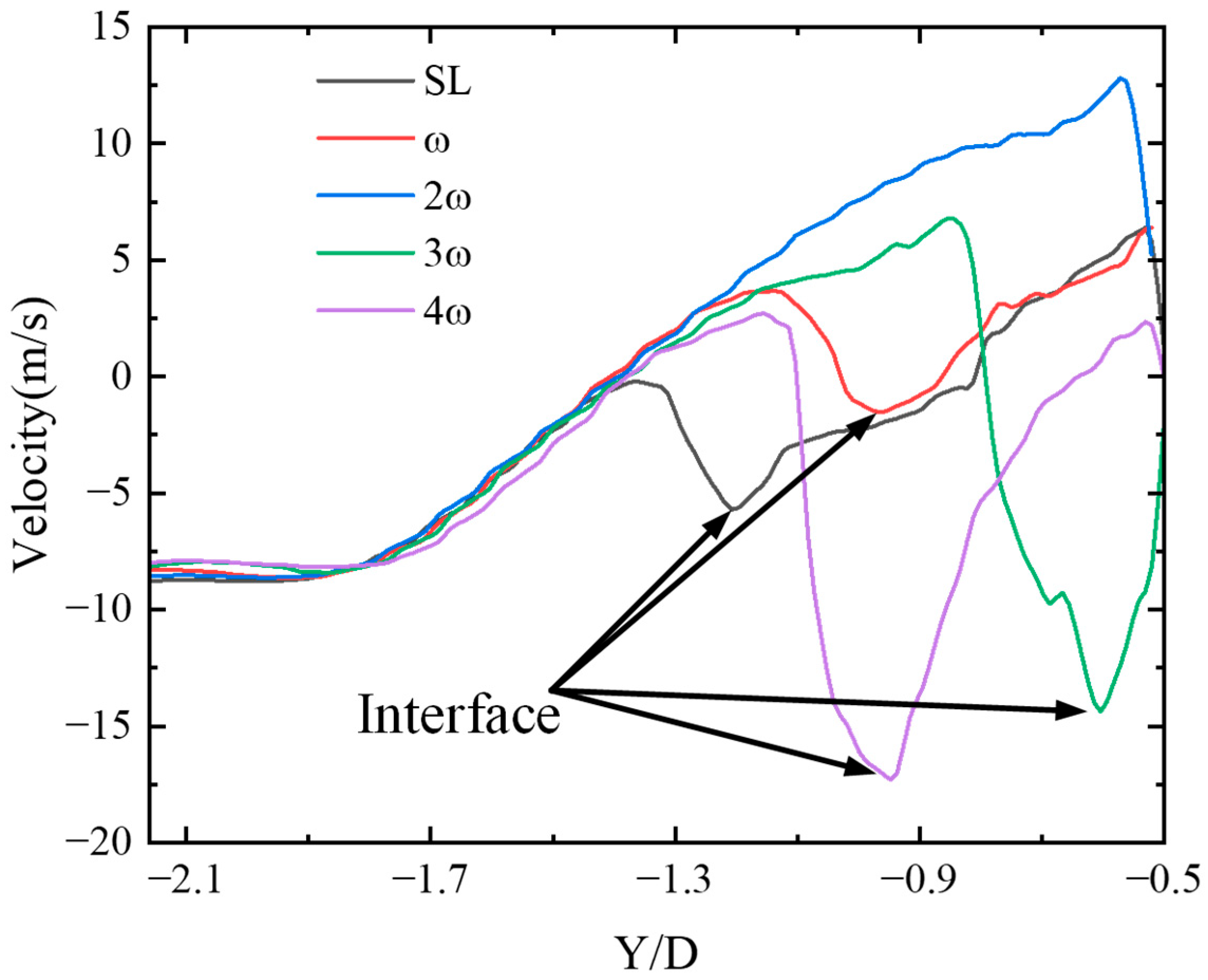

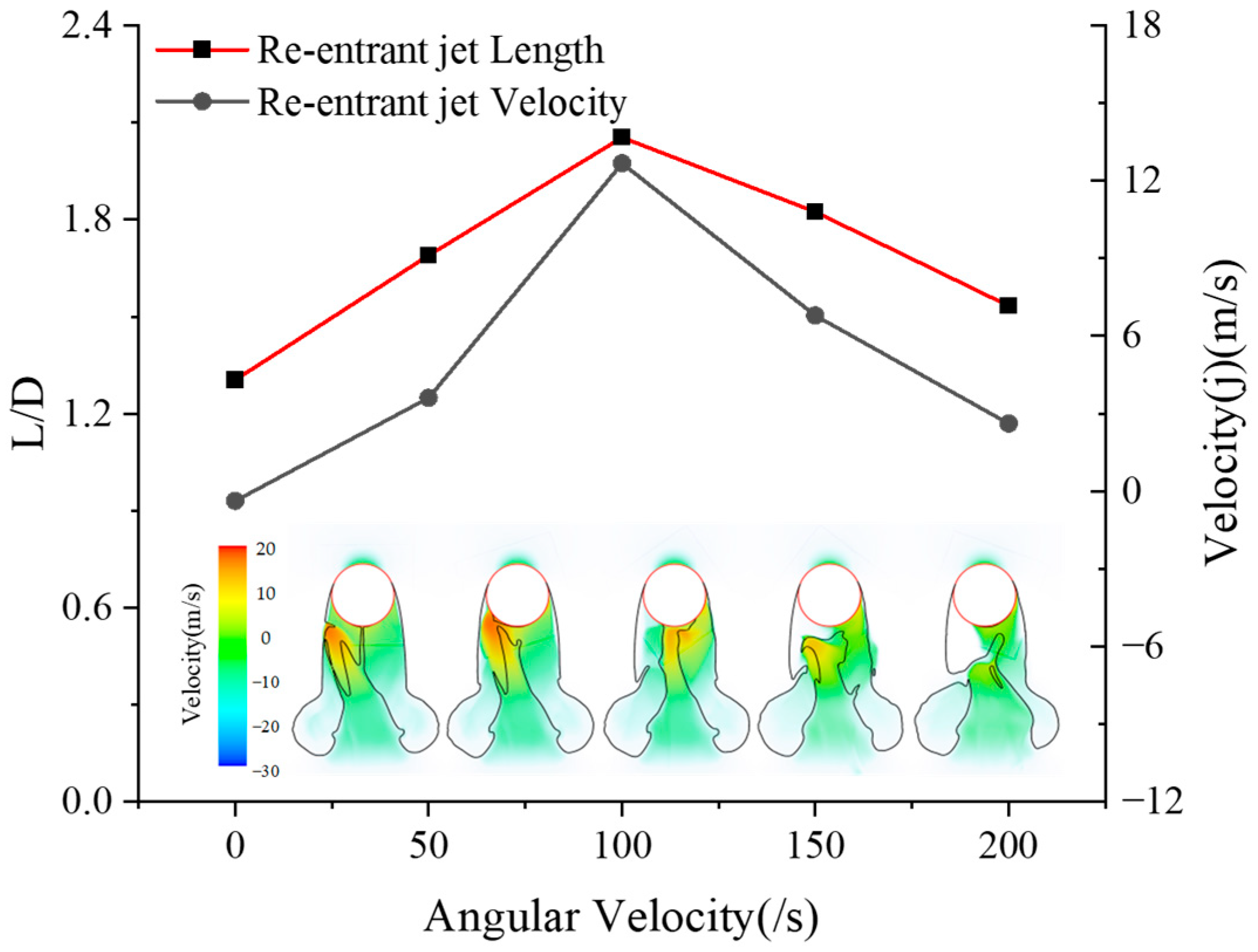

As described in the previous section, the rotational angular velocity has a significant impact on the development of the re-entrant jet.

Figure 27 presents the spatial distribution of the vertical fluid velocity directly beneath the sphere at the specified moment. Overall, the vertical velocity exhibits a consistent trend: it increases along the vertical direction from the bottom upward, reaches a maximum at the top of the re-entrant jet, then decreases as it crosses the gas–liquid interface, and subsequently rises again until it matches the velocity of the moving sphere.

Despite the general trend remaining similar, notable differences emerge under different rotational speeds. At lower angular velocities, the velocity drop occurs earlier, and the peak velocity is relatively low. As the angular velocity increases from 0 to

2ω, the onset of velocity drop is delayed, and the peak velocity rises. At

2ω, due to the well-developed re-entrant jet, no significant velocity decrease is observed before it reaches the sphere’s bottom surface. However, with further increases in angular velocity beyond

2ω, the velocity drop becomes increasingly pronounced again, and the peak velocity gradually declines.

Figure 28 illustrates the variation of the re-entrant jet’s apex distance from the bottom of the cavity and its corresponding peak velocity with respect to increasing angular velocity. It is evident that both the jet length and peak velocity reach their maximum at

2ω, indicating the most fully developed jet under this condition.

When the angular velocity does not exceed 2ω, the deflection of the jet inhibits its full development. Beyond 2ω, the inward-moving concave liquid flow directly interacts with the re-entrant jet, significantly disrupting its development and leading to a reduction in both jet length and velocity.

Figure 29 illustrates the mid-plane flow field distributions under four different rotational angular velocities. As previously discussed, the sphere’s rotation causes the flow separation point to shift along the direction of rotation. With increasing angular velocity, the streamlines near the sphere further deflect in the rotational direction. When the angular velocity exceeds

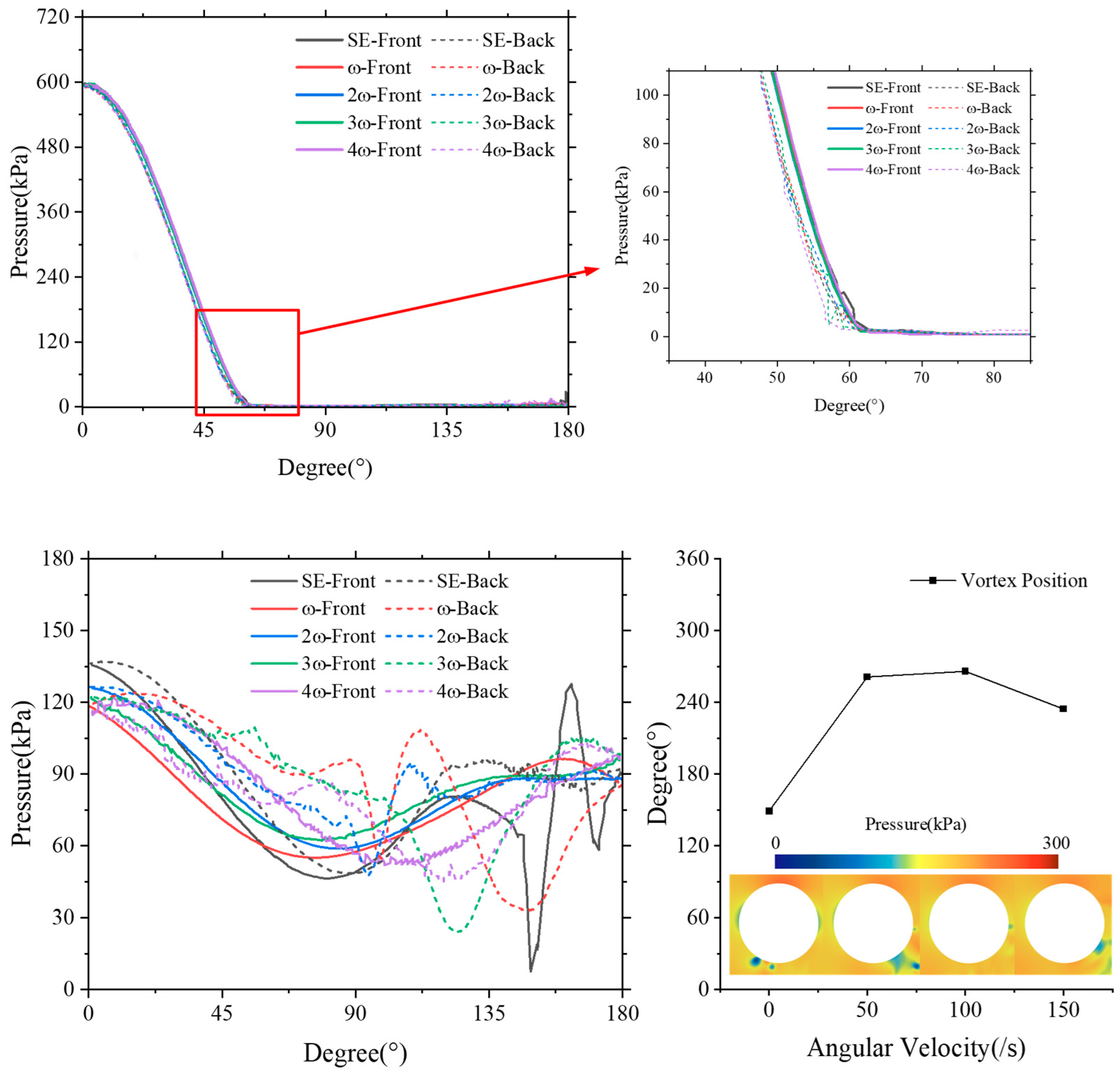

2ω, the flow separation point on the front side of the sphere becomes indistinguishable. The fluid near the sphere’s surface tends to follow the rotational path along the sphere’s contour and eventually merges with the downward flow on the rear side. This results in a transition in flow direction—from following the sphere’s surface to a pronounced downward movement. Moreover, with the further increase in angular velocity, the deflection of streamlines at the tail of the sphere becomes more prominent, indicating a stronger rotational influence on the wake structure.

Figure 30 presents the pressure distribution on the front and back surfaces of the sphere at the moment of cavitation onset (

t = 13.5 ms) and during fully wetted flow (

t = 45 ms). During the cavitation stage, the pressure distributions under different rotational angular velocities show minimal variation between the front and back surfaces. In all cases, high pressure is observed at the top of the sphere, gradually decreasing toward the bottom and reaching a minimum within the cavity. In contrast, under fully wetted conditions, the pressure distribution exhibits clear differences between the front and back surfaces of the sphere, as previously discussed. The rotation of the sphere enhances this asymmetry. It is observed that at an angular velocity of

ω, the pressure difference between the front and back surfaces reaches its maximum. However, as the rotation speed increases further (2

ω, 3

ω, and 4

ω), the difference in pressure distribution between the two sides gradually decreases, and the differences among these three cases become negligible.

Interestingly, with increasing angular velocity, more pronounced pressure fluctuations are observed on the back side of the sphere compared to the front. The locations where these fluctuations originate tend to shift along the rotational direction of the sphere. This behavior can be attributed to the fact that, on the back side, the rotational direction of the sphere is opposite to the direction of fluid flow. This counteraction may promote phenomena such as flow separation and vortex shedding to occur earlier, thereby altering the location of pressure fluctuation generation on the rear side.