Abstract

Main shaft bearings are among the critical rotating components of subsea drilling rigs, and their health status directly affects the efficiency and reliability of the drilling system. However, in the high-pressure liquid environment of the deep sea, with intense noise, the vibration signals of the bearings attenuate rapidly. As a result, fault-related features have a low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), which poses a challenge for bearing health monitoring. In recent years, Deep Neural Network (DNN)-based fault diagnosis methods for subsea drilling rig bearings have become a research hotspot in the field due to their strong potential for deep fault feature mining. Nevertheless, their reliance on high-power-consumption computational resources restricts their widespread application in subsea monitoring scenarios. To address the above issues, this paper proposes a fault diagnosis method for the main-spindle bearings of subsea drilling rigs that combines population coding with an adaptive-threshold k-winner-take-all (k-WTA) mechanism. The method exploits the noise robustness of population coding and the sparse activation induced by the adaptive k-WTA mechanism, achieving a noise-robust and energy-efficient fault diagnosis scheme for the main-spindle bearings of subsea drilling rigs. The experimental results confirm the effectiveness of the proposed method. In accuracy and generalization experiments on the CWRU benchmark dataset, the proposed method achieves good diagnostic accuracy that is not inferior to other SOTA methods, indicating relatively strong generalization and robustness. On the Paderborn real-bearing benchmark dataset, the results highlight the importance of selecting features that are adapted to specific operating conditions. Additionally, in the noise robustness and energy efficiency experiments, the proposed method shows advantages in both noise resistance and energy efficiency.

1. Introduction

With the increasing depletion of terrestrial resources worldwide, the ocean has become a vital strategic field for resource exploration and development in the 21st century [1,2]. As core pieces of equipment for the exploitation of marine oil and gas resources, subsea drilling rigs operate for long periods of time in extreme environments characterized by high deep-sea pressure, intense corrosion, and variable loads. This poses extremely high demands on the equipment’s safety and reliability. On subsea drilling rigs, main shaft bearings are critical rotating components that transmit power and receive the shock loads from drilling. Consequently, their health condition directly influences the equipment’s operational reliability and working efficiency.

Unlike land-based equipment, the operating environment for subsea drilling rig bearings is harsh. The strong damping effect of the deep-sea liquid medium causes the vibration signals generated by bearing faults to rapidly attenuate. Concurrently, drilling operations, ocean currents, and marine biological activity all generate significant background noise. This results in the collected bearing vibration signals generally exhibiting characteristics of a low Signal-to-Noise Ratio and weak fault features. Furthermore, the scarcity of energy resources in offshore and deep-sea environments imposes stringent requirements on the power consumption of the diagnostic system. Therefore, researching a diagnostic method that can accurately and reliably identify subsea drilling rig main shaft bearing faults against a strong noise background while also ensuring low energy consumption is of practical significance for guaranteeing the safety of marine engineering equipment and improving resource extraction efficiency.

Methodologies for bearing fault diagnosis are typically bifurcated into model-driven and data-driven categories. Model-driven techniques depend heavily on detailed physical models and expert-level domain knowledge, which complicates the creation of precise models for harsh operational settings, such as deep-sea conditions. In contrast, data-driven methodologies leverage bearing fault training data to model the intricate, non-linear mapping from raw sensory input to the fault dimension, reducing the dependency on a priori knowledge. These methodologies are generally categorized into Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) branches. Classic ML approaches, like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [3,4,5], Support Vector Machine (SVM) [6,7,8,9], and k-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) [10,11,12], are adept at identifying lower-level patterns from the data. Their performance, however, is contingent upon the quality of hand-crafted feature extraction. For these methods, it remains difficult to accurately characterize and differentiate weak, highly-distorted fault features, especially within the complex high-pressure, high-noise environments.

Deep Learning methods, through complex network architectures, can adaptively represent the internal correlations of the data and extract deep and robust hidden details from raw data, effectively bypassing the strong reliance of traditional methods on manual expertise. For example, Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) [13,14,15,16] excel in feature extraction, while Long Short-Term Memory network (LSTM) [17,18,19] are proficient at capturing the temporal dependencies of vibration signals. Furthermore, Autoencoders (AE) [20,21,22,23] and Deep Belief Networks (DBN) [24,25,26] are also frequently used for feature dimensionality reduction and deep learning.

Building on these advances, and in view of the specific characteristics of underwater environments, existing studies have optimized deep learning models. For example, CNN with multisensor feature fusion have been employed to diagnose faults in autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) [27,28] or thruster blades [29], and other studies have integrated convolutional Kolmogorov–Arnold networks (CKANs) with Squeeze-and-Excitation networks (SENets) to address the diagnosis of bearings in deep-sea propulsion systems [30]. Although these deep-learning-based methods can achieve high diagnostic accuracy, they often rely on powerful computing resources. This dependence conflicts with the very limited hardware capabilities and power supply of deep-sea edge devices, which restricts their practical application in deep-sea engineering scenarios.

As a third-generation neural network model, the spiking neural network, with its event-driven computation paradigm and ability to process complex spatiotemporal information, has been widely used in bearing fault diagnosis and has demonstrated competitive accuracy on benchmark datasets [31,32]. Thanks to the feature of emitting spikes only when the membrane potential exceeds a threshold, SNNs naturally enjoy sparse computation, strong noise robustness, and low power consumption. However, existing SNN-based diagnostic methods are mainly developed for onshore operating conditions and overlook the stringent energy-efficiency requirements of deep-sea environments. These models typically adopt a non-spiking “readout layer” at the output, causing membrane voltage amplitudes to substantially exceed the effective thresholds required for classification decisions. Such “over-confident representations” imply that the model continues to perform redundant computations even after the diagnostic outcome has become certain, thereby incurring unnecessary energy consumption. Therefore, this paper focuses on the main-shaft bearings of subsea drilling rigs and proposes a bearing fault diagnosis method that combines an adaptive-threshold k-winner-take-all (k-WTA) mechanism with population coding. In contrast to existing SNNs that adopt generic fixed-threshold encoding schemes, we introduce an adaptive-threshold k-WTA strategy which, through lateral competition, actively sparsifies spike firing and constrains membrane voltage amplitudes without compromising information integrity, thereby fundamentally reducing the power wasted by computational redundancy.

We conducted comprehensive experimental validation of the proposed method on two types of dataset: one consists of publicly available land-based benchmark datasets (including CWRU and Paderborn University dataset), and the other consists of a self-developed deep-sea drilling platform bearing fault dataset, which simulates real-world operating conditions. In terms of diagnostic accuracy and generalization ability, the method achieves state-of-the-art (SOTA) levels of high accuracy on the CWRU benchmark, while its differentiated performance on the PU dataset emphasizes the critical importance of feature selection tailored to specific operating conditions. Regarding noise robustness, the method significantly outperforms baseline models on artificially noise-augmented datasets, and more importantly, it maintains high diagnostic accuracy on the self-collected deep-sea testbed dataset, which inherently contains strong noise and signal attenuation, demonstrating its robustness in real-world harsh environments. Finally, in terms of energy efficiency, the proposed method shows a clear advantage over other deep learning approaches on the CWRU dataset, highlighting its potential for low-power monitoring applications in deep-sea environments.Based on the existing research, the main contributions of this paper are concentrated in the following three aspects:

- Targeted Methodological Application: This work tailors and optimizes a spiking neural network–based fault diagnosis scheme specifically for the challenges faced by main-spindle bearings of subsea drilling rigs under deep-sea operating conditions.

- Technical Contribution: We propose a novel encoding strategy that integrates Gaussian Receptive Field-based encoding with the adaptive-threshold k-Winner-Takes-All mechanism in SNN. This innovative combination effectively optimizes energy efficiency by reducing pulse amplitude and frequency without compromising the transmission of information.

- Validation and Proof: Through extensive experiments on both publicly available benchmark datasets (CWRU and PU) and a self-developed testbed dataset, we systematically validate the performance of the proposed method across three core metrics: diagnostic accuracy, noise robustness, and energy efficiency. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method offers a comprehensive advantage in terms of accuracy, robustness, and power consumption, showcasing its potential for low-power monitoring applications in deep-sea environments.

The remainder of this article is rolled out as follows. Section 2 provides a detailed description of the proposed method, including signal preprocessing and feature extraction techniques tailored to the characteristics of deep-sea environments, the core spike encoding mechanism, the SNN neuron model, and the model’s training strategy. Section 3 presents the experimental study, which focuses on three core dimensions: diagnostic accuracy, noise robustness, and energy efficiency. Finally, Section 4 briefly summarizes the research findings and discusses future practical engineering applications.

2. Methodology

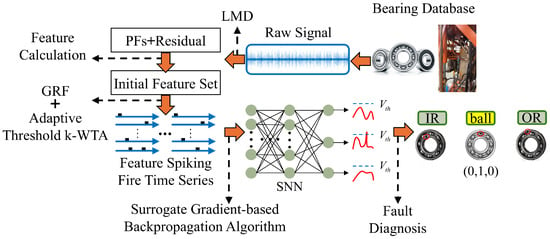

The proposed diagnostic procedure for bearing faults is outlined in Figure 1. First, the raw vibration signal of the subsea drilling rig main shaft bearing is collected via an accelerometer. Second, to extract high-quality input fault features, the Local Mean Decomposition (LMD) method is applied to the raw vibration signal, decomposing it into a linear combination of a series of Product Functions (PFs). Third, the extracted features are transformed into stable, high-information-content, and low-amplitude spike information through Gaussian Receptive Field Population Encoding combined with the Adaptive Threshold k-WTA mechanism. Subsequently, the SNN is trained using the Surrogate Gradient-based Backpropagation (BP) algorithm. Fourth, the encoded features are input into the trained SNN model to achieve the final bearing fault diagnosis. The key technical aspects are detailed in the subsequent sections.

Figure 1.

The proposed bearing fault diagnosis framework.

2.1. LMD-Based Feature Extraction

The complexity of stratum drilling, rolling element skidding, and faults generating multiple shocks, all overlaid by the complex background noise of the subsea drilling rig, results in the main shaft bearing fault vibration signals having complex and overlapping frequency bands. To minimize the influence of non-linear factors and meet the subsequent requirements for stability and linearity of the input signal, preprocessing the raw vibration signal with a suitable signal processing algorithm is necessary. A variety of signal processing techniques are prevalent in the literature for bearing fault diagnosis, including established methods like Fourier Transform (FT), Wavelet Transform (WT), Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD), and LMD. Nonetheless, these algorithms exhibit certain inadequacies when applied to the highly complex vibration signals originating from subsea main shaft bearings. As an example, the FT, while capable of intuitively presenting the frequency makeup of a signal, is inherently ill-suited to processing non-stationary signals. Given that subsea drilling rigs operate in complex geological strata, with continuous changes in shock, vibration, and load during the drilling process, the signals lack the required statistical properties of stationary signals. The WT is capable of scale contraction, allowing it to analyze local features of a signal in both time and frequency, making it suitable for non-stationary signals. Nevertheless, the empirical nature of selecting the wavelet basis function and the complex computation of the Continuous Wavelet Transform limit its application in real-time scenarios. The EMD often suffers from the problem of mode mixing when dealing with pulse interference and strong noise in the vibration signals of subsea drilling rig bearings, which can render the analysis results unusable. The LMD method can decompose non-linear signals with multiple superimposed vibration modes into a series of single-component signals, each possessing an instantaneous amplitude and instantaneous frequency. These components are s, which can be represented in the form of an Amplitude Modulation (AM) signal multiplied by a Frequency Modulation (FM) signal. By adopting a more localized and robust decomposition strategy, LMD generally proves advantageous in processing complex signals. Therefore, this paper will process the raw subsea drilling rig bearing vibration signal using LMD and extract the fault features from the resulting Product Functions. The brief implementation procedure is described below.

- For a given signal , the first step is to identify all its local extreme points . Based on these extreme points, two numerical values are constructed: the local mean and the local envelope :where i denotes the index of the PF, j denotes the iteration number during the decomposition process and k denotes the index of the extreme value.

- Using the moving average method to generate the local mean function and the envelope function , and subtracting the local mean function from the signal , yields a detrended signal :

- Normalize the detrended signal by dividing it by the local envelope function to obtain an ideal purely Frequency-Modulated signal :

- If does not satisfy the criterion for a purely FM signal, then is taken as the new input signal, and the aforementioned Steps 1–3 are repeated until the convergence condition is met. If the iteration converges, the final purely FM signal is multiplied by the product of all local envelope functions obtained during all iteration steps. The result is the final Product Function :where l refers to the maximum number of iterations.

- Subtract the extracted from the original signal to obtain the residue signal :

- Take as the new input signal, and repeat the entire aforementioned procedure to extract the next PF component, until the final residue signal becomes a monotonic function and can no longer be decomposed. The original signal will then be decomposed as:

To ensure the reproducibility of the LMD decomposition process, the detailed parameter settings used in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key Parameter Settings of the LMD Decomposition Used in This Study.

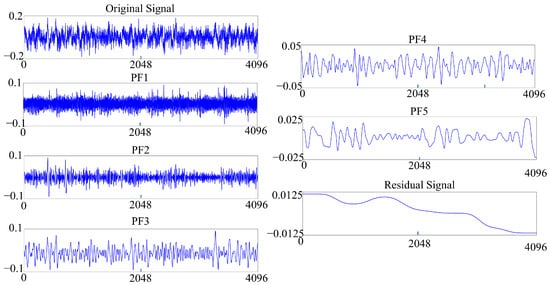

The key parameters listed in Table 1 control the behavior and stopping criteria of the LMD decomposition. First, to mitigate edge effects, the signal endpoints are treated as pseudo-extrema, enabling a stable estimation of the local envelope and mean near the boundaries. Within the inner sifting process, a maximum of smoothing iterations and envelope iterations are permitted for each PF. To prevent excessive computation without significant quality gain, the sifting terminates early if the variations in the envelope and modulation signal fall below the tolerances and , respectively. Globally, the decomposition depth is capped at , ensuring that only a finite number of physically meaningful oscillatory modes are extracted. For the subsequent feature extraction, only the first five components (PF1–PF5) and the final residual are retained, as shown in Figure 2. This selection is justified because these initial components capture the majority of the vibration energy and fault-related modulation signatures, whereas the discarded higher-order PFs primarily represent slowly varying trends with negligible diagnostic value.

Figure 2.

LMD extracted PFs and residual signal from CWRU data.

In the high-pressure fluid environment of the deep sea, the high-density fluid acts as a damping medium, leading to significant attenuation of bearing vibration energy. The associated fluid–structure interaction also modifies the time-varying stiffness and modal characteristics of the system. Therefore, when constructing the feature set, we give priority to dimensionless statistical descriptors that characterize the intrinsic waveform shape and periodicity of the PF components and are invariant to uniform scaling of the vibration amplitude, namely kurtosis, crest factor, impulse factor and spectral kurtosis. In addition, we include spectral energy as a complementary feature to retain information about the absolute vibration energy in the frequency domain under strong attenuation. Consequently, five features are extracted from each PF component and the residual signal—kurtosis, crest factor, impulse factor, spectral energy and spectral kurtosis—as summarized in Table 2. These five raw features are not used directly. Before being fed to the SNN coding unit, each feature dimension is min–max normalized so that its values lie in the range . see Equation (9) for the exact normalization formula.

Table 2.

The Statistical Features Derived from Each PF Component.

The variables used in Table 2 are defined as follows. N is the total number of sampling points in the signal segment. is the discrete time-domain vibration signal of the PF component or residual, measured as bearing acceleration in units of m/s2. is the mean value of , and is its root-mean-square (RMS) value, both sharing the same unit as . denotes the maximum absolute value (peak amplitude) of the vibration signal . denotes the one-sided discrete Fourier transform (DFT) coefficient of at the k-th frequency bin (), with units of m/s2. is the corresponding power spectrum magnitude with units of (m/s2)2, and denotes its mean value over all frequency bins.

2.2. SNN Configuration for Subsea Diagnosis

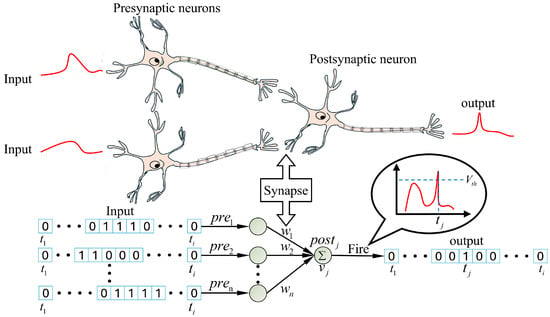

The computation of the Spiking Neural Network (SNN) is based on discrete action potentials rather than continuous values, simulating the behavior patterns of biological neurons. In the SNN, information is transmitted in the form of spikes from presynaptic neurons to postsynaptic neurons. The logical core lies in the dynamic change of the membrane potential.

When a postsynaptic neuron receives any incoming spike, its membrane potential increases accordingly. The function of this membrane potential is the continuous accumulation and integration of all received signals over time. Once the neuron’s membrane potential reaches and surpasses a predetermined firing threshold, it immediately responds by emitting a new output spike. Immediately thereafter, the neuron’s membrane potential is reset to its resting potential state in preparation for the next round of information processing. The architectural design of the SNN and this event-driven spike generation and reset mechanism are illustrated in detail in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Spiking neuron information transfer process.The red curve in the enlarged part represents the simulated membrane potential, and the blue dashed line denotes the firing threshold.

2.2.1. Proposed Encoding Mechanism

Unlike the continuous floating-point activation value transmission mode of an Artificial Neural Network (ANN), the SNN utilizes discrete spike emissions occurring at precise time points to transmit complex information. This event-driven computational style and spike sparsity allow SNN to reduce computational activity, achieving the advantages of low power consumption and high efficiency. Therefore, for classifying subsea drilling rig bearing faults using the SNN, an appropriate encoding scheme is required to convert the aforementioned feature information into spike sequences.

Current spike encoding methods are mainly categorized into Rate Coding, Temporal Coding, and Population Coding. Rate Coding expresses information through the average spiking activity but does not rely on precise spike timing, offering strong robustness. However, it requires prolonged integration and statistics collection, leading to high latency, and the frequent spiking activity results in higher computational power consumption.Temporal Coding utilizes the precise time of spike firing to encode information. It can transmit information with the minimum number of spikes, achieving extremely low computational power consumption and ultra-low latency response speeds. Nevertheless, the limitation of Temporal Coding is its reliance on precise spike timing, making it more sensitive to noise caused by the environment or hardware, and typically requiring more complex architectures and algorithms for processing. Population Coding represents information through the coordinated activity of a group of neurons, achieving strong robustness against random noise and perturbations, as well as accurate representation of feature values. When combined with sparse representation, it can also bring about significant low-power consumption advantages.

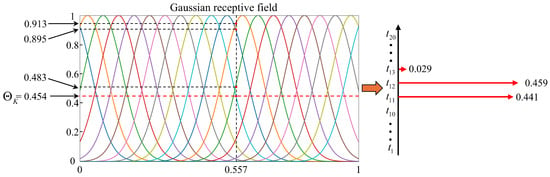

Therefore, we propose a spike encoding method based on Gaussian Receptive Fields combined with an Adaptive Threshold k-Winner-Take-All (k-WTA) mechanism. This method skillfully utilizes the feature redundancy of Population Coding and the activation sparsity of the Adaptive k-WTA mechanism to simultaneously satisfy the dual requirements of anti-noise capability and low power consumption in the deep-sea edge computing environment. The implementation steps are as follows:

First, to map features of different scales to a unified range, the entire dataset must be scaled globally, as follows:

where and are the minimum and maximum values in the extracted feature set, respectively.

Set the encoding population to consist of N neurons, where each neuron defines a unique Gaussian tuning curve T. The center position and the Gaussian receptive field width for the i-th neuron are defined as:

where is a hyperparameter.

Substitute into the receptive field defined by N Gaussian tuning curves to calculate the raw activation intensity for each neuron:

where is the maximum activation intensity, which is usually set to 1.

Perform Adaptive Threshold k-WTA screening on the activation values to retain the K neurons with the highest activation intensity in the set .

Define the K-th highest activation intensity as the adaptive threshold . The final output intensity is then derived through a comparison operation with the adaptive threshold :

The final feature F is then encoded into a spike sequence . For instance, a normalized real-valued feature of is encoded within a Gaussian receptive field consisting of neurons. Subsequently, the activation values are sparsely filtered using the Adaptive Threshold mechanism and the k-WTA competitive strategy, yielding a sparse output vector (). This encoding and competition process is detailed in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Real-valued feature encoding process. The curves of different colors represent the Gaussian tuning curves of individual neurons.

2.2.2. AdEx Neuron Model

This paper adopts the Adaptive Exponential Integrate-and-Fire (AdEx) [33] model as the neuron model for the SNN, as this model strikes a good balance between dynamical richness and computational complexity. The AdEx model functions as a hybrid dynamical system, where its behavior is collectively defined by continuous threshold dynamics and discrete spike firing events. The formula for the discrete-time update of the membrane voltage of the j-th postsynaptic AdEx neuron is defined as:

where is the leak conductance, is the resting potential, is spike sharpness, is the effective threshold potential, is the synaptic weight between the i-th presynaptic neuron and the j-th postsynaptic neuron, is the spike sequence output of the i-th presynaptic neuron and is the adaptation variable, defined as follows:

where is the time step, is the adaptation time constant, and b is a hyperparameter.

The triggering condition for the AdEx neuron’s spike firing event is when the membrane potential exceeds a set peak voltage . The instantaneous reset rules are as follows:

where is the output value of the j-th postsynaptic neuron at time step , is the resting voltage, and a is a hyperparameter.

2.2.3. Model Training Strategy

Currently, there are three main types of mainstream training algorithms for Spiking Neural Networks: the bio-inspired Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity (STDP) [34], the indirect ANN-SNN Conversion method [35], and the direct training approach of Surrogate Gradient Descent [36]. The STDP algorithm boasts high biological plausibility but often suffers from limited diagnostic accuracy, making it difficult to satisfy the requirements of industrial scenarios. While the ANN-SNN conversion method can inherit the high accuracy of the source ANN, its drawback is that the converted SNN often requires consuming many time steps during inference to precisely approximate the source network’s performance. This dependency leads to high latency in model inference.

Given the practical demands for real-time performance and low power consumption in subsea drilling rig fault diagnosis, the Surrogate Gradient Descent method—as a direct training approach—is able to achieve high diagnostic accuracy while constructing low-latency, high-energy-efficiency diagnostic models. This makes it the optimal choice for simultaneously addressing the performance and edge deployment efficiency requirements for subsea bearing fault diagnosis.Therefore, this paper will adopt Surrogate Gradient Descent as the training method for the Spiking Neural Network. A brief introduction to the SNN training method based on Surrogate Gradient Descent is presented below.

For multiclass classification tasks like bearing fault diagnosis, the most commonly used and robust choice is the combination of Cross-Entropy Loss and Softmax. Their definitions are as follows:

where is the one-hot encoding of the true label, is the probability of class j given by the Softmax function, and is the total number of spikes emitted by the output neuron of class i.

The complete gradient formula for the hidden layer weights is expressed as:

where is the connection weight between the i-th neuron in the -th layer and the j-th neuron in the l-th layer, is the error signal of the k-th neuron in the -th layer at time step t, is the membrane voltage of the j-th neuron in the l-th layer at time step t, is the firing threshold voltage, is the spike output of the i-th neuron in the -th layer at time step t, and is the Arctangent Surrogate Gradient Function, defined by the derivative as:

In the above expression, represents the membrane potential relative to the threshold, while , the adjustable parameter controlling the gradient steepness, is set to 25.

The update formula for the connection weight is as follows:

where is the learning rate.

3. Experiment

To systematically evaluate the performance of the bearing fault diagnosis method proposed in this paper, a series of diagnostic experiments were conducted and are described in this section. Given the current lack of a recognized public benchmark dataset for deep-sea operating conditions, and to ensure experimental objectivity and comparability, we introduce two public terrestrial benchmark datasets (CWRU and Paderborn) to test the model’s fundamental effectiveness and generalization capability. Secondly, to examine the model’s actual performance and practical value under the target operating conditions, this study also utilizes a bearing dataset collected from the “Subsea Drilling Rig Main Spindle Condition Simulation Test Rig,” which was built by our research team, to verify the model’s true performance in the final target application scenario.

The content of this chapter is organized as follows: Section 3.1 introduces the datasets, Section 3.2 details the experimental design, and Section 3.3 compares and analyzes the experimental results. All experiments were conducted on a Windows 11 (64-bit) operating system. The hardware configuration was an Intel® Core™ i9-13980HX CPU with 16.0 GB of RAM, and the software environment was implemented based on Anaconda Navigator 2.5.0 and PyCharm 2023.3.7 (Community Edition).

3.1. Dataset Introduction

3.1.1. CWRU Dataset

The CWRU bearing dataset, published by the university’s Bearing Data Center [37], is an internationally recognized benchmark dataset for rolling element bearing fault diagnosis. The data for this dataset was collected from a specially constructed test platform. This platform primarily consists of a 2-horsepower (HP) drive motor, a power test meter, a torque sensor, and control electronics. The experimental bearing was installed on the motor’s main shaft to support the rotor.

The CWRU dataset introduces single-point faults separately on the IR, OR, and rolling elements of the test bearings using Electro-Discharge Machining technology. Each fault location includes three different levels of damage severity, with fault diameters of 0.007 inches, 0.014 inches, and 0.021 inches, respectively. Vibration signals were acquired by accelerometers installed on the motor casings at both the drive end and the fan end. The data acquisition utilized two main sampling frequencies: 12 kHz and 48 kHz. The experiments covered four different motor load conditions, ranging from 0 to 3 horsepower, simulating the bearing’s operational status under various loads.

The CWRU dataset covers a variety of motor loads, fault locations, and fault scales. To ensure the representativeness and comparability of the experimental results, this study selected specific, typical operating conditions for model validation (detailed bearing selections are shown in Table 3).

Table 3.

Sample bearings from the CWRU dataset.

During the sample extraction phase, all vibration signals were segmented into samples with a length of 4096 sampling points. For each fault state, 100 data samples were extracted, resulting in a total of 1000 samples, to ensure a sufficient sample size for training and testing.

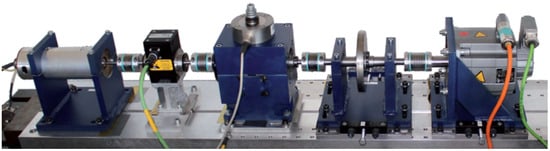

3.1.2. Paderborn University Dataset

The Paderborn University dataset dataset (PU) [38], provided by Paderborn University in Germany, is another internationally recognized benchmark for bearing fault diagnosis. Unlike the artificial EDM faults in the CWRU dataset, it primarily contains real, naturally formed faults generated through accelerated life tests. The data for this set was collected from a modular test rig, as shown in Figure 5, which is capable of simulating different rotational speeds, loads, and radial force conditions.The fault types within the dataset are diverse, including pitting caused by fatigue, plastic deformation, and indentations resulting from particle contamination. Vibration signals were captured by an accelerometer mounted on the bearing housing, while the test rig also recorded operating parameters such as motor current, speed, and temperature.

Figure 5.

The test rig used by the Paderborn University dataset [38].

Since the fault characteristics in the Paderborn University dataset more closely resemble the actual degradation states of bearings in industrial practice, their signal features are often more complex and subtle. Therefore, the core purpose of employing this dataset in our study is to test the proposed method’s generalization capability and robustness when faced with more complex, realistic fault signals. The bearing types and codes selected for this experiment are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

The samples chosen from the real damaged bearings.

3.1.3. Target Application Dataset

As outlined in the previous section, the CWRU and Paderborn datasets are benchmarks from standard terrestrial, air-based environments. They cannot replicate the unique physical challenges of deep-sea conditions, especially the rapid attenuation of vibration signals and strong ambient noise caused by high-density fluid damping. To verify the proposed method’s true performance in the target environment, this study uses a self-built Target Application Dataset.

This dataset was collected from the “Subsea drilling rig main shaft condition simulation test bench,” whose structure is shown in Figure 6, and which was built by our research team. Due to the excessive size of an actual deep-sea drilling rig, which prevents it from being placed inside a sealed chamber for testing, a simulated, scaled-down drilling rig equipped with the same QJ305M bearing as the actual equipment was used for pressurized experiments. The detailed geometric parameters of the bearing are provided in Table 5.

Figure 6.

Subsea drilling rig main shaft condition simulation test bench.

Table 5.

Geometric parameters of the bearing.

During the experiments, the mock drilling rig was mounted inside a cylindrical high-pressure chamber. According to the design specifications, the chamber has an inner diameter of 750 mm, an effective internal height of 2700 mm, and a total outer-shell length of 3200 mm. Fresh water was used as the working fluid and continuously pumped into the chamber and pressurized to 60 MPa to simulate a deep-sea pressure environment corresponding to a water depth of 6000 m. The fluid temperature was maintained at 19 ± 1 °C. Under these conditions, the platform’s hydraulic system applied an alternating radial load to the bearing. Because the test bearing was identical to the target application component, the load magnitude was selected based on the rated dynamic load of the QJ305M bearing ( = 39 kN). Specifically, the hydraulic system imposed an alternating radial load varying between 3 kN and 5 kN to reproduce the stress levels encountered in actual operations.The bearing operated at a constant speed of 3600 RPM, and vibration signals were collected by a piezoelectric accelerometer installed radially on the main bearing seat, with the sampling frequency set to 12,000 Hz.

This experiment includes four bearing health states: Normal, Inner Race fault, Outer Race fault, and Rolling Element fault. All faults were manufactured using Electrical Discharge Machining with a uniform fault size of 0.8 mm. A total of 160 data samples were extracted for each state, with each sample containing 4096 sampling points. This ultimately formed a deep-sea bearing diagnosis dataset containing 640 samples. This dataset serves as the final validation stage for this research, with its core purpose being to test the model’s true performance and practical value under the low Signal-to-Noise Ratio and strong attenuation challenges described in the introduction.

3.2. Experimental Design

To evaluate the proposed method with respect to three core indicators—good diagnostic accuracy, strong noise robustness, and low power consumption—we designed an experimental protocol along three dimensions: diagnostic accuracy and generalization verification, anti-noise performance verification, and energy-efficiency analysis. Section 3.2.1 assesses the diagnostic accuracy and generalization capability of the proposed method under standard operating conditions using land-based benchmark datasets (CWRU and PU). Section 3.2.2 evaluates the model’s robustness to noise by artificially injecting Gaussian white noise with different signal-to-noise ratios into the test sets of the land-based benchmark datasets. For the self-collected dataset, which was acquired under real operating conditions and already contains relatively strong environmental noise, we did not add additional artificial white noise; instead, we directly evaluated the model on the raw data as a supplementary verification of its anti-noise capability under real-world conditions. Section 3.2.3 further examines the advantage of the proposed adaptive-threshold k-WTA mechanism in reducing energy consumption. The detailed experimental parameter settings are provided in the subsequent subsections.

3.2.1. Diagnostic Accuracy and Generalization Verification

To ensure experimental reproducibility, this section first presents the general configuration and parameter settings of the proposed model. At the encoding level, the spike input of the SNN is obtained using a Gaussian Receptive Field (GRF)–based encoding method combined with the adaptive-threshold k-WTA mechanism (see Section 2.2.1 for details). The GRF width factor is set to 0.8, the competition parameter K to 4, and the final input dimensionality is fixed at 600.

Regarding neuronal dynamics, the model adopts the AdEx neuron as its basic unit, with the following parameters: leak conductance , resting potential , effective threshold , and spike slope factor . The adaptation parameters , a, and b are set to , 2, and , respectively, and the membrane reset potential is .

The general training hyperparameters are as follows: the optimizer is Adam, the loss function is cross-entropy, the learning rate , the temporal window length time steps, and the batch size is 32. In terms of network architecture, specific topological adjustments are made to address the diagnostic challenges of different datasets. For the CWRU dataset, the SNN adopts a fully connected structure with neuron layers configured as 600–120–60–10 (corresponding to ten fault categories), and the total number of training epochs is set to 30. For the Paderborn dataset, which contains more complex natural fault characteristics, the network is configured as 600–400–200–3 (corresponding to three fault categories), and the total number of epochs is increased to 50 to ensure sufficient convergence and the ability to distinguish subtle fault features

For the CWRU dataset, we utilized all 1000 available samples, covering 10 distinct fault classes, to evaluate the fundamental monitoring performance of the proposed SNN method. To ensure a more comprehensive and stable assessment of the model’s generalization performance and robustness, this experiment employed the k-Fold Cross-Validation method. Specifically, the entire sample set was randomly and equally partitioned into k mutually exclusive subsets. In each validation fold, one subset was designated as the test set, and the remaining subsets were input into the network for training. The model utilized the training set data from that fold to optimize the weights and biases, and its generalization performance was assessed using the test set of that fold. In this study, we set , implementing a 5-fold cross-validation. In each iteration, the data was partitioned into an training set and a test set. The overall performance of the classifier was then reported as the average accuracy across these k experiments.

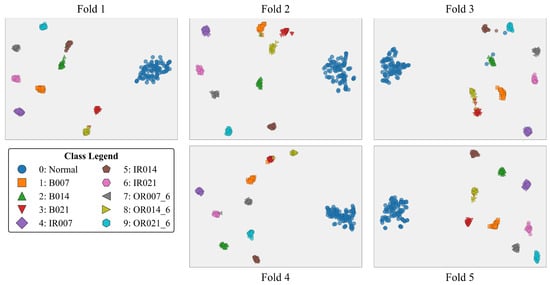

Furthermore, to visually demonstrate the network’s ability to discriminate fault features in the latent space, we also present the feature visualization result obtained using the t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) [39] method for one of the 5-folds.

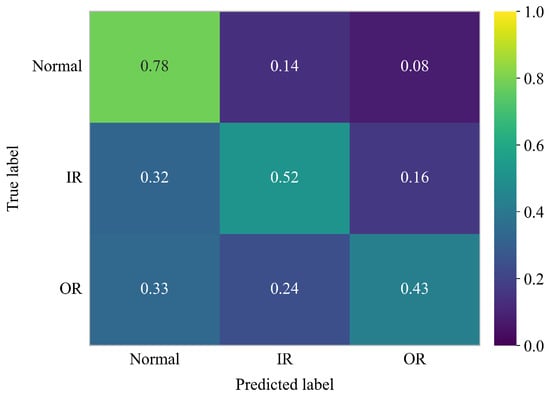

To assess the generalization performance and robustness of the proposed method under real, naturally developed faults, the Paderborn University (PU) dataset was employed. Since the PU dataset contains multiple independent bearing instances with distinct damage origins, a rigorous instance-based cross-validation strategy was adopted rather than simple random partitioning. Specifically, all samples were grouped by bearing set (each set typically containing bearings with inner-race, outer-race, and rolling-element faults from a single experimental run), and a “leave-one-set-out” k-fold protocol was used. In each fold, one complete bearing set was held out for testing, while the remaining sets were used for training, ensuring that the model was always evaluated on an entirely unseen set of physical wear characteristics. This protocol is summarized in Table 4. The overall diagnostic performance was reported as the average accuracy across all validation folds.

Furthermore, beyond average accuracy, the results were analyzed using a Confusion Matrix to quantify the specific difficulties the model encounters in discriminating between the subtle, overlapping fault signatures inherent to naturally occurring wear. We also present a feature visualization obtained using the t-SNE method for a selected fold to further illustrate the separability of the learned representations.

3.2.2. Anti-Noise Performance Verification

This experiment was designed to quantitatively assess the robustness of the proposed SNN method against noise interference, which is a critical challenge in subsea environments. The validation strategy specifically evaluates how well the model maintains its diagnostic accuracy as the SNR decreases.

Since both the CWRU and PU datasets we used were collected under low-noise laboratory conditions, we added artificial Gaussian white noise to the clean test samples to simulate different noise intensities. The noise injection process followed the standard definition of SNR, calculated as follows:

where denotes the average power of the original vibration signal and denotes the average power of the added noise.

Specifically, we tested a comprehensive range of noise conditions by varying the SNR from down to (i.e., , , …, , …, ) in uniform increments of . The models trained on the clean data (as defined in Section 3.2.2) were directly evaluated on these noisy test sets. The results are reported by plotting the diagnostic accuracy as a function of the SNR level for all comparison methods.

The subsea drilling rig dataset inherently contains strong environmental noise and signal attenuation due to its unique acquisition environment. therefore, its diagnostic result serves as direct supplementary validation of the model’s robustness under real, complex noise conditions, and no additional artificial noise is injected into this dataset.to ensure reliable performance assessment despite the limited sample size (640 samples), the entire dataset will be rigorously evaluated using the 5-fold cross-validation method. the data partitioning process and the method for reporting the average accuracy will be consistent with the k-fold protocol detailed for the cwru dataset in Section 3.2.1. Furthermore, the overall diagnostic performance will be analyzed in detail not only by average accuracy but also through the presentation of a confusion matrix. this is essential to precisely quantify the model’s discriminative ability across different fault categories under the challenging, real-world low-snr conditions. The SNN model parameters for this validation strictly follow the general configurations established at the beginning of Section 3.2.1, except that the SNN structure is adjusted to 600–200–120–4 and the training epochs are set to 30.

3.2.3. Energy-Efficiency Analysis

To fully demonstrate the energy-efficiency advantage of the proposed SNN model, we conducted a theoretical energy comparison following established neuromorphic computing methodologies [40,41]. The key objective is to verify whether the proposed adaptive-threshold k-WTA mechanism can effectively reduce power consumption.

Following the methodology in [41], the total number of operations in the ANN for the convolution and fully connected layers is given by:

where denotes the kernel width (height), the number of input (output) channels, the height (width) of the output feature map, and the number of input (output) features.

For the iso-architectural SNN, the number of operations depends on the average spike rate of each layer:

where

and denotes the total number of spikes in layer l over all timesteps divided by the number of neurons in that layer. A spike rate of 1 (every neuron firing once) implies that the number of operations for ANN and SNN is the same (though the operations are MAC in ANN and AC in SNN), while lower spike rates indicate higher sparsity and, consequently, a lower number of effective operations.

In our energy estimation, we first measure the average spike firing rate of the proposed SNN on the test set. Subsequently, the corresponding operation counts and theoretical energy consumption are computed using the formulas and per-operation costs defined above. To strictly evaluate the energy superiority of our method under the premise of high diagnostic performance, we conducted a quantitative comparison with representative state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods on the CWRU dataset. The specific quantitative results and comparative analysis are reported in the following results section.

3.3. Results Comparison and Analysis

This section, adhering to the experimental protocol defined in Section 3.2, will sequentially present and analyze the model’s experimental results in three aspects: diagnostic accuracy, noise robustness, and power consumption.

3.3.1. Diagnostic Accuracy Results

First, we present and analyze the experimental results on the CWRU benchmark dataset. We report the diagnostic performance of the proposed method under this 5-fold validation, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Diagnostic accuracy (%) across the 5-folds of the CWRU dataset.

To demonstrate the superiority of the proposed approach, we further compare the diagnostic accuracy on the CWRU benchmark with several representative state-of-the-art (SOTA) fault diagnosis methods. The results of our method and the competing approaches are summarized in Table 7. Specifically, existing advanced methods evaluated on the CWRU bearing dataset include the Diagnosisformer model based on multi-feature parallel fusion and attention mechanisms proposed in Ref. [42] (average accuracy = 99.85%), the Probabilistic Shock Response Model (PSRM) proposed in Ref. [31] (average accuracy = 99.38%), and the Variational Kernel CNN (VKCNN) proposed in Ref. [43], which achieved 100% accuracy.

Table 7.

Comparison of diagnostic accuracy on the CWRU bearing dataset.

In comparison, our proposed SNN-based method (results computed from Table 6) achieved a high mean validation accuracy of 99.75% with a low standard deviation of ±0.16% (calculated as the average of the testing accuracy across all 5 folds). Although this does not reach the perfect accuracy reported in Ref. [43], it remains highly competitive, performing on par with other SOTA methods such as PSRM (99.38%) and Diagnosisformer (99.85%). This demonstrates that the proposed method ranks among the leading diagnostic approaches, exhibiting excellent generalization and robustness in classical bearing fault diagnosis tasks.

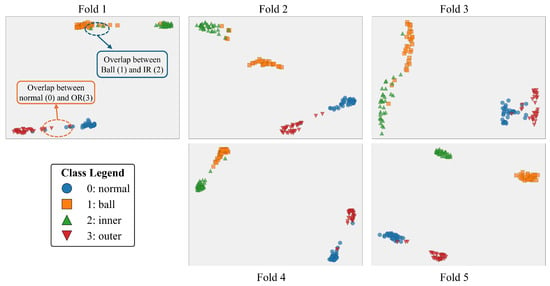

To further verify the discriminative capability of the proposed model, we apply t-SNE to the test samples of the CWRU dataset under the 5-fold cross-validation setting, as shown in Figure 7. It can be seen that the samples of different fault categories form compact and well-separated clusters in the latent feature space. This clear clustering pattern is mainly due to the physical characteristics of the faults in the CWRU dataset. Most defects are local single-point damages. During bearing rotation, these defects generate periodic, high-amplitude impact pulses. Under the relatively high signal-to-noise ratio of this test rig, these characteristic impact components are well preserved and are not masked by background noise. This allows our model to distinguish different fault types more easily and to achieve high diagnostic accuracy.

Figure 7.

T-SNE-based Fault Feature Visualization for the CWRU Dataset (Result of 5-Fold Cross-Validation).

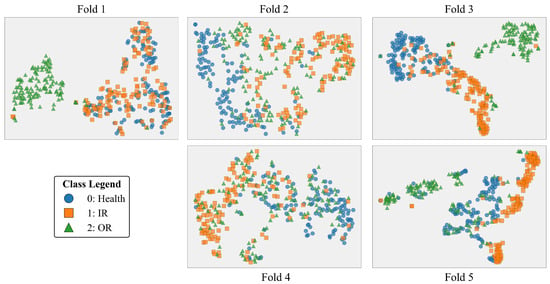

Here we present and analyze the diagnostic results achieved on the PU dataset. The overall 5-fold cross-validation results show that the average validation accuracy on this dataset is only 57.47%, with a standard deviation as high as 12.55%. Among the five folds, the highest accuracy is 73.92% in the 3rd fold, while the lowest accuracy drops to 36.02% in the 5th fold. The detailed results are given in Table 8. Such a large difference between folds highlights the challenging nature of the PU dataset.

Table 8.

Accuracy per fold on the Paderborn dataset (%).

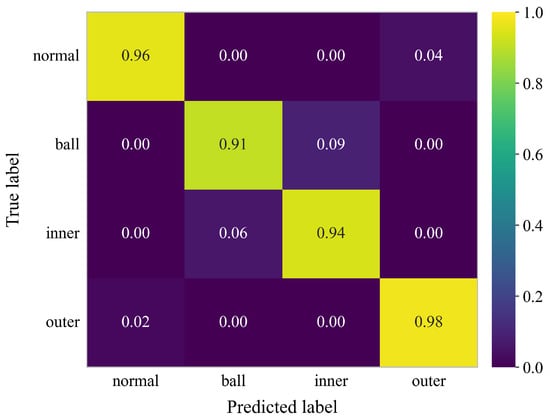

The t-SNE visualization in Figure 8 provides an intuitive confirmation of this difficulty, showing that the fault sample clusters are heavily intertwined and almost indistinguishable from the healthy baseline. The confusion matrix in Figure 9 further supports this observation from a quantitative perspective, revealing a systematic failure of the model to detect faulty conditions. Specifically, although the “normal” condition is recognized with an accuracy of 78%, a substantial portion of faulty samples are misclassified as “normal”: 32% of inner-race (IR) faults and 33% of outer-race (OR) faults are incorrectly predicted as healthy.

Figure 8.

T-SNE-based Fault Feature Visualization for the Paderborn University dataset (Result of 5-Fold Cross-Validation).

Figure 9.

Aggregated 5-fold cross-validation confusion matrix for the PU dataset.

This high false-negative rate mainly comes from a mismatch between the chosen feature set (see Table 2) and the physical characteristics of faults in the PU dataset. Most features used in this work are dimensionless indicators that are robust to damping. They were designed for deep-sea conditions with strong fluid damping, where the signal amplitude is attenuated but prominent impact components are preserved. In the Paderborn dataset, the situation is different. It contains realistic fatigue damage such as spalling and pitting. The impact energy generated by these defects is weak. It is easily masked by the complex background mechanical noise of the test rig. Because the fault signals do not exhibit clear outlier impulses, the feature statistics of true faults become very similar to those of healthy bearings. As a result, features that rely on capturing strong impulsive components fail under this low-SNR condition. This failure leads to the marked performance degradation on this dataset.

Experimental results on the PU dataset reported in Ref. [31] further support this explanation. In that study, the authors used an SNN-based diagnostic model and deliberately selected features such as the clearance factor, which are more sensitive to early and weak impacts. Their model achieved an average test accuracy of 75.97% on the PU dataset, which is 18.5% higher than our method. This performance gap suggests that the feature set needs to be adapted to the specific fault mechanisms and noise conditions of the PU dataset.

3.3.2. Noise Robustness Experimental Results

This section presents the results of the experiment described in Section 3.2.2, which aims to evaluate the robustness of the proposed method under low SNR conditions—a key challenge in subsea operating environments.

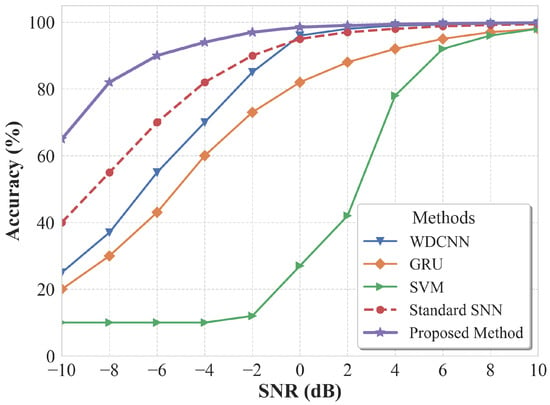

Figure 10 illustrates the accuracy–SNR curves of the proposed method and several baseline approaches on the CWRU dataset [44]. As shown, all methods maintained high diagnostic accuracy under high-SNR conditions (SNR > 4 dB). However, as noise intensity increased and SNR decreased, the performance of all models declined, albeit at different rates. Among them, SVM exhibited the highest sensitivity to noise and almost completely failed when SNR fell below 0 dB, with its accuracy dropping to approximately 10%. WDCNN and GRU performed slightly better, but their accuracies at 0 dB fell to around 82% and below 96%, respectively.

Figure 10.

Noise robustness comparison of different methods on the CWRU dataset.

In contrast, the Proposed Method achieved the best performance across all noise levels and showed remarkable stability under severe noise. At 0 dB, it still achieved 98.5% accuracy; at −4 dB, the accuracy remained at 94%, whereas the standard SNN and WDCNN dropped to approximately 82% and 70%, respectively. Even under the extremely harsh condition of −10 dB, the proposed method maintained an accuracy of about 65%. These results clearly demonstrate the strong robustness of the proposed approach under severe noise interference, confirming its ability to effectively extract and discriminate fault features that are heavily masked by noise.

For the PU dataset, additional noise injection was not conducted, as its baseline diagnostic performance was relatively limited, making further noise degradation uninformative for comparative analysis.

Following the preceding noise robustness experiments, we further validated the proposed model using our self-collected subsea drilling rig dataset. This dataset simulates a deep-sea, high-pressure environment and features a significantly lower signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) compared to the terrestrial benchmark datasets. This enables a more realistic assessment of the model’s diagnostic robustness under harsh operating conditions. The detailed experimental parameters for this section are given in Section 3.2.2. This dataset was evaluated using the same 5-fold cross-validation protocol, and the results are summarized in Table 9. The proposed model achieved a high average training accuracy of 99.48% and an average validation accuracy of 94.94%, confirming its capability to effectively isolate and identify bearing fault features even in a high-noise deep-sea environment.

Table 9.

Accuracy per fold on the self-built dataset (%).

The t-SNE visualization of the test samples from the self-collected underwater dataset under 5-fold cross-validation is shown in Figure 11. Overall, the different fault classes form clusters with relatively clear boundaries in the feature space. This indicates that the proposed model has strong class-discrimination ability. However, some clusters still overlap. This overlap reflects similarities in the vibration fault characteristics. It is mainly concentrated between class 0 (normal) and class 3 (outer race), and between class 1 (rolling element) and class 2 (inner race).

Figure 11.

T-SNE-based Fault Feature Visualization for the self-built dataset (Result of 5-Fold Cross-Validation).

To further describe these pairwise confusions in a quantitative way, we aggregate the confusion matrices obtained from the 5-fold cross-validation, as shown in Figure 12. We can observe that misclassifications are concentrated between class 0 and class 3, with mutual misclassification rates of 4% and 2%, and between class 1 and class 2, with mutual misclassification rates of 9% and 6%. This pairwise confusion pattern is consistent with the cluster overlaps observed in the t-SNE visualization. These fault patterns seem to be related to the kinematic properties of the bearing components and the characteristics of the deep-sea environment.

Figure 12.

Aggregated 5-fold cross-validation confusion matrix for the self-collected dataset.

First, for the confusion between “normal” and “outer race” (class 0 and class 3), the results may suggest that outer-race fault signals suffer from strong energy attenuation in the deep-sea environment. The outer race is a static component. Its impact signals are more easily suppressed by the strong damping effect of the deep-sea fluid during transmission. This attenuation may cause a significant reduction in Spectral Energy. At the same time, the impact components may be smoothed. As a result, time-domain indicators such as Kurtosis and Crest Factor may have statistical distributions that are close to the normal background noise. This makes the faults harder to distinguish.

Second, for the confusion between “rolling element” and “inner race” (class 1 and class 2), both fault types come from rotating components. In a high-pressure deep-sea environment, the high external pressure and the thick high-viscosity oil film change the contact and lubrication conditions between the rolling elements and the raceways. The rolling elements are more likely to experience local slip. This potential instability may blur or shift the characteristic frequencies of features such as Spectral Kurtosis and Impulse Factor. As a result, the signal characteristics of inner-race and rolling-element faults become more similar in the feature space. This similarity leads to misclassification by the model.

3.3.3. Energy Efficiency Assessment

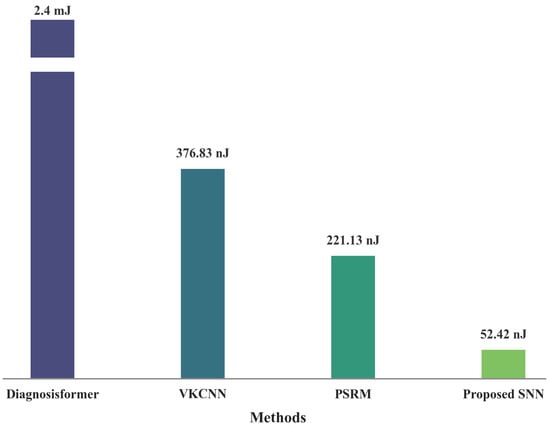

This section presents the quantitative assessment results to highlight the core low-power advantage of the proposed method. Given that the energy consumption of the population coding mechanism in the proposed SNN is complex to quantify under the standard operation counting method, we exclude this pre-processing stage from the calculation. To ensure a fair and consistent comparison of the core inference efficiency, we explicitly exclude the feature extraction components of the models (i.e., the Encoder in Diagnosisformer and the Convolutional layers in VKCNN). Following the theoretical estimation model, we derive the inference energy for each architecture.

First, for Diagnosisformer, the energy consumption is determined by the computational cost of the Decoder layers (including Self-Attention, Cross-Attention, and FFN):

In contrast, for VKCNN, the estimation focuses solely on the fully connected (FC) classifier backend:

Finally, for SNN-based methods, the energy is driven by the total synaptic operations, accumulated over the measured firing rate and time steps T:

The per-inference energy consumption of the proposed method and several SOTA methods on the CWRU dataset is compared in Figure 13. The results show that different network architectures have large differences in energy efficiency. Specifically, the Transformer-based Diagnosisformer model in Ref. [42] has the highest energy consumption, about 2.4 mJ. This is mainly because its self-attention and cross-attention modules are very computationally intensive and require many matrix multiplications. In contrast, the proposed SNN consumes only 52.42 nJ per inference. This gives about a 45,000× improvement in energy efficiency and shows the potential of SNNs for low-power applications. In addition, compared with the relatively lightweight fully connected classification back-end in VKCNN from Ref. [43], whose energy consumption is 376.83 nJ, the proposed SNN still achieves about a 7.2× reduction in energy. This suggests that, for classification tasks of similar scale, spiking neural networks implemented with 0.9 pJ accumulate (AC) operations have a clear advantage in energy efficiency over conventional artificial neural networks based on 4.6 pJ multiply–accumulate (MAC) operations. Finally, when comparing SNNs of a similar type, it is important to note that the diagnostic network architecture and the number of time steps used in the PSRM model of Ref. [31] are different from those in this work. Therefore, its reported per-inference energy consumption of 221.13 nJ is only partially comparable and is used here as a reference. To obtain a fairer baseline, we implement a conventional SNN with the same neuron count and the same time-step setting as our model (see Table 10). This baseline has an average firing rate of 53.45% and an estimated per-inference energy consumption of 71 nJ. These results show that the adaptive-threshold k-WTA mechanism in the proposed SNN increases spike sparsity and reduces activation levels, which further lowers the energy consumption to 52.42 nJ.

Figure 13.

Comparison of energy consumption among different diagnosis methods.

Table 10.

Energy comparison between the proposed SNN and a conventional SNN baseline under identical architecture and time-step settings.

4. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper focuses on the health monitoring of main-spindle bearings in subsea drilling rigs. In the deep-sea environment, with high pressure and strong noise, the vibration signals of bearings are severely attenuated and the fault features have a low SNR, which makes fault diagnosis challenging. Existing deep-neural-network-based diagnosis methods have strong feature extraction ability but rely heavily on high-power computing resources and are therefore difficult to deploy widely in subsea monitoring scenarios.

To address this problem, this paper proposes a spiking neural network fault diagnosis method that combines population coding with an adaptive-threshold k-Winner-Take-All (k-WTA) mechanism. The adaptive-threshold k-WTA is introduced into the Gaussian receptive-field population coding process. It not only sparsely selects the activation values but also improves energy efficiency by reducing the amplitude of spike emissions. In this way, the method exploits both the feature representation capability of population coding and the sparse activation provided by the k-WTA mechanism, achieving a fault diagnosis scheme for main-spindle bearings that is both noise-robust and energy-efficient. Experimental results show that the proposed method achieves high diagnostic accuracy and good generalization performance on both the CWRU benchmark dataset and the self-built deep-sea testbed dataset. Moreover, in noise-robustness and energy-efficiency evaluation experiments, the proposed method shows clear advantages over the comparison methods in terms of noise resistance and energy consumption.

For future practical engineering applications, we propose the following concrete implementation guidelines for the design of the health monitoring system of subsea drilling rigs. First, in view of the severe attenuation, distortion, and even loss that fault signals may suffer during transmission over ultra-long umbilical cables, the proposed deep-sea fault diagnosis model should preferably be deployed on underwater embedded nodes for local real-time processing, thereby avoiding the communication burden and signal degradation associated with transmitting raw vibration data to the surface. Second, based on the power estimation formula in Equation (28), the choice of the time-step number in the SNN hyperparameter configuration should be carefully optimized, to avoid unnecessary energy overhead while maintaining diagnostic accuracy. Finally, following the findings of Ref. [45], we recommend deploying the proposed diagnostic method on dedicated neuromorphic chips with asynchronous, event-driven operation, so as to fully exploit their sparse-computation advantages, further reduce system-level power consumption through hardware acceleration, and improve monitoring efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H. (Jiawen Hu), J.H. (Jingbao Hou), and Z.C.; Methodology, J.H. (Jingbao Hou) and J.H. (Jiawen Hu); Software, J.H. (Jiawen Hu); Validation, J.H. (Jiawen Hu), Y.Z., and T.Y.; Formal Analysis, J.H. (Jiawen Hu); Investigation, J.H. (Jiawen Hu); Data Curation, J.H. (Jiawen Hu); Writing—Original Draft Preparation, J.H. (Jiawen Hu); Writing—Review and Editing, J.H. (Jingbao Hou) and Z.C.; Visualization, J.H. (Jiawen Hu); Supervision, J.H. (Jingbao Hou); Project Administration, J.H. (Jingbao Hou); Funding Acquisition, J.H. (Jingbao Hou). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was developed with the help of Grant 24B0434 funded by the Research Foundation of Education Bureau of Hunan Province, and Grant CX20251535 funded by the Hunan Province Graduate Student Research Innovation Project. The APC was funded by the Research Foundation of Education Bureau of Hunan Province.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Case Western Reserve University Bearing Data Center for providing the public bearing fault datasets used in this study. This research was also supported by the National-local Joint Engineering Laboratory of Marine Mineral Resources Exploration Equipment and Safety Technology, Hunan University of Science and Technology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Guo, X.; Fan, N.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Xie, X.; Jia, Y. Deep seabed mining: Frontiers in engineering geology and environment. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2023, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Abubakar, I.R.; Nunes, C.; Platje, J.; Ozuyar, P.G.; Will, M.; Nagy, G.J.; Al-Amin, A.Q.; Hunt, J.D.; Li, C. Deep seabed mining: A note on some potentials and risks to the sustainable mineral extraction from the oceans. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, K.; Qiu, G.; Gu, Y. Rolling bearing fault diagnosis using hybrid neural network with principal component analysis. Sensors 2022, 22, 8906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Xiao, J.; Li, C.; Xu, Z.; Yue, M. Fault diagnosis of rolling bearing using CNN and PCA fractal based feature extraction. Measurement 2023, 223, 113754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A.; Bappy, M.M.; Mudiyanselage, A.S.; Li, J.; Jiang, Z.; Tian, Z.; Fuller, S.; Falls, T.; Bian, L.; Tian, W. Multi-channel sensor fusion for real-time bearing fault diagnosis by frequency-domain multilinear principal component analysis. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 124, 1321–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xiao, M.; Niu, Y.; Ji, G. Rolling bearing fault diagnosis based on WGWOA-VMD-SVM. Sensors 2022, 22, 6281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Anand, R. Bearing fault diagnosis using multiple feature selection algorithms with SVM. Prog. Artif. Intell. 2024, 13, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Qiu, W.; Hu, X.; Wang, W. A rolling bearing fault diagnosis technique based on recurrence quantification analysis and Bayesian optimization SVM. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 156, 111506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Q.; Xu, H.; Li, X.; Fang, Z.; Yao, W. Rolling bearing fault diagnosis based on SVM optimized with adaptive quantum DE algorithm. Shock Vib. 2022, 2022, 8126464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaleshtori, A.E.; Aghaie, A. An enhanced statistical feature fusion approach using an improved distance evaluation algorithm and weighted K-nearest neighbor for bearing fault diagnosis. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.21219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwendra, M.A.; Salunkhe, P.S.; Patil, S.V.; Shinde, S.A.; Shinde, P.; Desavale, R.; Jadhav, P.; Dharwadkar, N.V. A novel method to classify rolling element bearing faults using K-nearest neighbor machine learning algorithm. ASCE-ASME J. Risk Uncertain. Eng. Syst. Part B Mech. Eng. 2022, 8, 031202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Upadhyaya, G. Fault diagnosis of rolling element bearing using continuous wavelet transform and K-nearest neighbour. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 92, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Cong, Y.; Song, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liang, P. A bearing fault diagnosis model based on CNN with wide convolution kernels. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2022, 13, 4041–4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Shi, C.; Sheng, H.; Li, X.; Yang, T. Lightweight CNN architecture design for rolling bearing fault diagnosis. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 126142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Peng, D.; Cheng, Z. Attention-guided joint learning CNN with noise robustness for bearing fault diagnosis and vibration signal denoising. ISA Trans. 2022, 128, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, G.; Liu, E.; Wang, X.; Ziehl, P.; Zhang, B. Enhanced discriminate feature learning deep residual CNN for multitask bearing fault diagnosis with information fusion. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 19, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Q.; Chai, Y.; Huang, X. Rolling bearing fault diagnosis method base on periodic sparse attention and LSTM. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 12044–12053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, W. An ensemble deep learning network based on 2D convolutional neural network and 1D LSTM with self-attention for bearing fault diagnosis. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 172, 112889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Kong, J.; Zhao, Y.; Qian, W.; Xu, X. A deep-learning model with improved capsule networks and LSTM filters for bearing fault diagnosis. Signal Image Video Process. 2023, 17, 1325–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Huang, X.; Wang, Y.; Luo, R.; Zhou, Q. Transfer learning based on improved stacked autoencoder for bearing fault diagnosis. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 256, 109846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Hao, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y. Novelty detection and fault diagnosis method for bearing faults based on the hybrid deep autoencoder network. Electronics 2023, 12, 2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.X.; Cao, C.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, Z.Z. A real-time bearing fault diagnosis model based on siamese convolutional autoencoder in industrial internet of things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 11, 3820–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yu, J.; Leng, H.; Du, X.; Liu, Y. Bearing fault detection by using graph autoencoder and ensemble learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Xu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Pei, Z. Rolling bearing fault diagnosis based on SSA optimized self-adaptive DBN. ISA Trans. 2022, 128, 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; He, D.; Wei, Z. Intelligent fault diagnosis of train axle box bearing based on parameter optimization VMD and improved DBN. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 110, 104713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Geng, Y.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, W. Bearing Fault diagnosis based on improved DBN combining attention mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Padua, Italy, 18–23 July 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H.; Song, Z.; Bai, X.; Zhang, K. Attention mechanism-based multisensor data fusion neural network for fault diagnosis of autonomous underwater vehicles. J. Field Robot. 2024, 41, 2401–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, A.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Zeng, Q. Fault diagnosis of autonomous underwater vehicle with missing data based on multi-channel full convolutional neural network. Machines 2023, 11, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.M.; Wang, C.S.; Chung, Y.J.; Sun, Y.D.; Perng, J.W. Multisensor fusion time–frequency analysis of thruster blade fault diagnosis based on deep learning. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 19761–19771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Liu, D.; Zong, Z.; Wang, C.; Wang, R.; Zhou, F.; Hu, X. Research on intelligent diagnosis of deep-sea submersible bearing failures based on dual adaptive modeling. AIP Adv. 2025, 15, 105026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.; Xu, F.; Zhang, C.; Xiahou, T.; Liu, Y. A multi-layer spiking neural network-based approach to bearing fault diagnosis. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 225, 108561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.; Ding, Y.; Jing, M.; Yang, K.; Chen, B.; Yu, Y. Toward end-to-end bearing fault diagnosis for industrial scenarios with spiking neural networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.11067. [Google Scholar]

- Aamir, S.A.; Müller, P.; Kiene, G.; Kriener, L.; Stradmann, Y.; Grübl, A.; Schemmel, J.; Meier, K. A mixed-signal structured AdEx neuron for accelerated neuromorphic cores. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2018, 12, 1027–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporale, N.; Dan, Y. Spike timing–dependent plasticity: A Hebbian learning rule. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 31, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, T.; Fang, W.; Ding, J.; Dai, P.; Yu, Z.; Huang, T. Optimal ANN-SNN conversion for high-accuracy and ultra-low-latency spiking neural networks. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.04347. [Google Scholar]

- Neftci, E.O.; Mostafa, H.; Zenke, F. Surrogate gradient learning in spiking neural networks: Bringing the power of gradient-based optimization to spiking neural networks. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2019, 36, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case Western Reserve University. Case Western Reserve University Bearing Data Center Website. 2024. Available online: https://engineering.case.edu/bearingdatacenter/ (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Lessmeier, C.; Kimotho, J.K.; Zimmer, D.; Sextro, W. Condition monitoring of bearing damage in electromechanical drive systems by using motor current signals of electric motors: A benchmark data set for data-driven classification. PHM Soc. Eur. Conf. 2016, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaten, L.v.d.; Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2008, 9, 2579–2605. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, M. 1.1 computing’s energy problem (and what we can do about it). In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference Digest of Technical Papers (ISSCC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 9–13 February 2014; pp. 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rathi, N.; Roy, K. Diet-snn: A low-latency spiking neural network with direct input encoding and leakage and threshold optimization. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 34, 3174–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Ma, J.; Li, T. Diagnosisformer: An efficient rolling bearing fault diagnosis method based on improved Transformer. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 124, 106507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Tang, G.; Zhu, Z. VKCNN: An interpretable variational kernel convolutional neural network for rolling bearing fault diagnosis. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 62, 102705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.; Zhu, T.; Akram, M.W.; Jin, Y.; Zhu, C. An adaptive anti-noise neural network for bearing fault diagnosis under noise and varying load conditions. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 74793–74807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.; Wild, A.; Orchard, G.; Sandamirskaya, Y.; Guerra, G.A.F.; Joshi, P.; Plank, P.; Risbud, S.R. Advancing neuromorphic computing with loihi: A survey of results and outlook. Proc. IEEE 2021, 109, 911–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).