Abstract

The Twin Hybrid Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (THAUV) is an underwater monitoring system consisting of a twin buoyant body and a fixed wing mounted between them. It is equipped with two propeller thrusters and a pair of elevators at the aft end. As a new type of underwater vehicle, it combines the long endurance of an underwater glider (UG), the high-speed maneuverability of an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV), and the ability to carry larger payloads. In this paper, the motion equations of the THAUV are established, and its simulation model is developed using SIMULINK. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) is further employed to identify hydrodynamic parameters under different elevator size conditions. A case study is conducted to analyze the effects of three different widths of elevators on glide performance, including gliding speed, pitching angle, and gliding trajectory. CFD results show that when the elevator deflection angle is zero, the hydrodynamic forces acting on the THAUV increase as the elevator width increases under identical angle of attack and velocity conditions. Under CFD conditions with fixed angle of attack and flow velocity, the sensitivity of the hydrodynamic characteristics to elevator deflection became significantly more pronounced. Increasing the elevator deflection angle led to substantial growth in the generated hydrodynamic forces. Motion simulations further show that increasing the elevator deflection angle enhances the THAUV’s gliding performance. Comparative results also reveal that glide performance improves with larger elevator width.

1. Introduction

The underwater glider (UG) is a specialized platform for subsurface monitoring and investigation, diving and ascending by regulating buoyancy via an internal engine [1]. Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) are commonly utilized across marine geosciences and play critical roles in scientific research, military operations, commercial activities, and policy development [2]. The twin hybrid autonomous underwater vehicle (THAUV) combines the low-energy, long-endurance gliding of a UG with the high-speed maneuverability of a thruster-driven AUV [3]. By alternately switching between UG and AUV modes, the THAUV can perform underwater data acquisition and seabed monitoring missions over larger areas. Its twin-body architecture also accommodates larger payload capacity, enabling it to carry more energy storage or sensor equipment, thereby significantly enhancing its operational endurance and mission range. A six-degree-of-freedom (DOF) nonlinear kinematic and dynamic model of a Hybrid Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (HAUV) has been developed to describe both propulsion-driven and gliding locomotion [4]. The UG typically performs reciprocating diving and floating motions, while its pitch attitude is controlled by adjusting a movable mass block inside the vehicle [5,6,7,8,9,10]. Beyond internal mass adjustment, attitude control can also be achieved using external control surfaces. By altering the orientation of these surfaces during motion, the hydrodynamic forces act on the vehicle change, thereby regulating its attitude. For example, ref. [11] investigates the motion control and guidance of an X-rudder AUV propelled by a single thruster. The X-rudder configuration enables maneuvering in all directions, offering improved maneuverability and safety compared to conventional rudder systems. Because developing underwater vehicles is costly and time-consuming, numerical simulation has become indispensable in design and analysis. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), in particular, is widely used to calculate hydrodynamic parameters due to its advantages of low cost, high accuracy, and rapid results. For instance, refs. [12,13,14,15] applied CFD methods to estimate the hydrodynamic characteristics of underwater vehicles. In references [16,17], the spatial equations of motion for underwater vehicles are derived in detail.

External control surfaces, such as fixed wings, rudders, and elevators, are fundamental to both the gliding performance and attitude control of underwater vehicles. In this study, the THAUV employs a pair of tail-mounted elevators to regulate and control its pitch attitude. Working in coordination with the buoyancy engine, the THAUV achieves cyclic diving and surfacing motions in gliding mode. The kinematic equations of the THAUV in space are established, and Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) is applied to acquire the hydrodynamic parameters of its underwater motion. In the motion simulations, variations in buoyancy and elevator deflection angle are prescribed as inputs, enabling an intuitive assessment of elevator’s effects on gliding behavior. This study analyzes and compares the motion parameters of the vehicle in the vertical plane—such as pitching angle, gliding speed, and depth—under different elevator configurations. The comparison shows that increasing elevator width enhances the gliding performance of the THAUV.

2. Structure Design of THAUV

As a novel type of underwater intelligent monitoring equipment, the THAUV exhibits distinctive structural features compared to conventional underwater gliders. A conventional single-body underwater glider typically comprises a buoyant body and a pair of fixed wings. In contrast, the THAUV integrates two buoyant bodies connected by an intermediate section. This interconnecting section acts as a fixed wing, generating the lift required for forward gliding. The twin-body architecture offers several advantages: it enables larger buoyancy excursion and greater payload capacity, thereby enhancing the maneuverability, endurance, and overall operational capability of the THAUV.

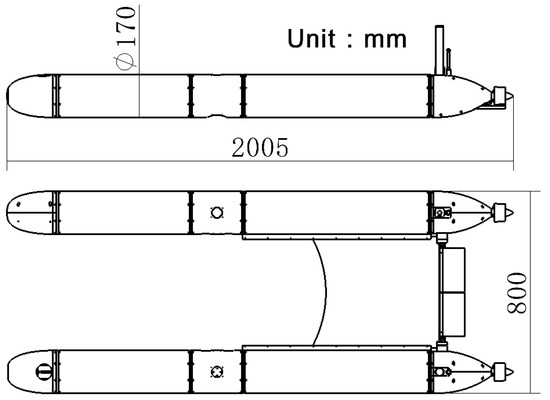

The THAUV is equipped with a wide range of underwater inspection instruments and sensors, including an underwater camera, Doppler Velocity Logger (DVL), altimeter, Ultra-Short Baseline (USBL) positioning system, Conductivity-Temperature-Depth (CTD) sensor, data transmission antenna, seafloor mapping instrument, and Optical Communication System (OCS). As an integrated platform with multiple data acquisition devices, the THAUV can perform diverse ocean data collection tasks in a single deployment, thereby reducing the costs associated with multiple launches of conventional single-body underwater gliders. The structural configuration of the THAUV is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of THAUV.

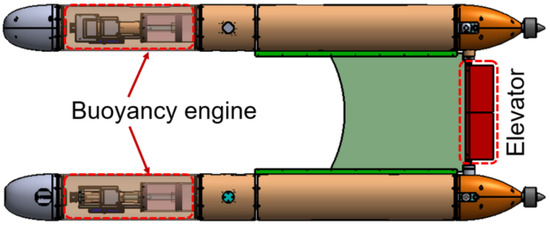

The THAUV is equipped with two independent piston-driven buoyancy engines, each housed in a sealed compartment located in the forward section of the twin buoyant bodies. By translating the pistons, the displaced volume of the vehicle is adjusted, causing it to either sink or rise. Aft, a pair of elevators controls pitch. During descent, the elevators deflect downward, altering the hydrodynamic forces on the THAUV and generating the required nose-down pitching moment; during ascent, the elevators deflect upward to produce the opposite effect. The configuration of the buoyancy engines and elevators is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Configuration of buoyancy engine and elevator.

3. Mathematic Model of THAUV

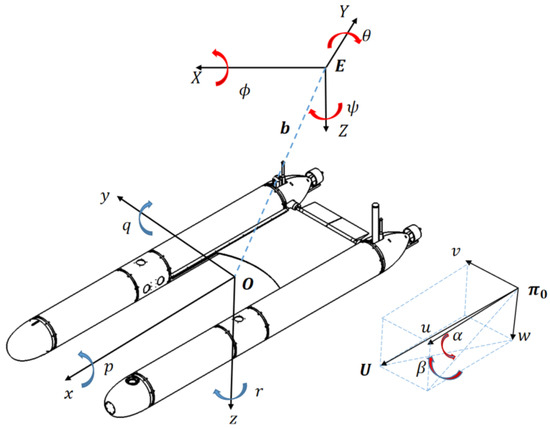

The motion of a rigid body in space is commonly described using two relative coordinate systems [18]. Figure 3 illustrates the two coordinate systems adopted for the THAUV: the reference frame E-XYZ and the body frame O-xyz. The reference frame E-XYZ has its origin E at an arbitrary point, with the EZ-axis pointing vertically downward along gravity, the EX-axis lying horizontally, and the EY-axis determined by the right-hand rule. The body frame O-xyz has its origin O at the buoyancy center of the vehicle. In this system, the Ox-axis coincides with the vehicle’s longitudinal axis, while the Oz-axis is taken parallel to the EZ-axis of the reference frame.

Figure 3.

The coordinate of THAUV.

The position of the vehicle in the reference frame can be denoted as the vector . In the reference frame, the linear and angular velocities of the THAUV are expressed as vectors and , respectively.

The vehicle’s position relative to the reference frame is assigned by the rotation matrix R. The matrix R is parameterized by corresponding to roll, pitch, and yaw. The transformation matrix from the body-fixed frame O-xyz to the reference frame E-XYZ is expressed as Equation (1) [18].

For a vector , the skew-symmetric matrix is expressed as Equation (2) [16]:

For any vector , the vector product of and is expressed as

The kinematics of the vehicle can be denoted as

and denote the overall linear and rotational momentum of the THAUV within the stationary Earth frame; , , and denote the linear momentum of the pistons and rollers on the right and left sides, respectively [16].

Consider as a unit vector oriented towards the gravitational force, while is the external force applied to the glider system, and is the external torque applied to the system. The vector specifies the location where the external force is applied in relation to the reference frame. Forces and act upon the left and right pistons originating from the glider body, and and represent the forces exerted by the glider body on the right and left rotary rollers.

signifies the overall linear momentum of the glider-fluid system as observed in the body frame. represents the aggregate angular momentum about the origin of the body frame. and are designated to express the momentum of the right and left pistons, respectively, and and correspond to the momentum of the right and left rotary rollers within the body frame.

By integrating (4) and (5), the differentiations for both sides of Equations (12)–(17) are derived as shown below:

The ensuing kinematic equations are formulated within the body frame, as detailed below:

Here, and denote the internal forces exerted on the right and left pistons, respectively, expressed in the body frame; and denote the internal forces exerted on the right and left rotary rollers in the body-fixed frame.

Let

The cumulative kinetic energy for the glider-fluid system is computed, with the kinetic energies associated with the fixed mass, pistons, and rollers detailed subsequently:

The kinetic energy of a solid object submerged in a perfect fluid can be formulated as follows:

In this context, represents the added mass matrix, denotes the added inertia matrix, and signifies the added cross term matrix. These matrices are derived based on the body’s geometry and the fluid density. The overall kinetic energy of the glider-fluid system is expressed as follows:

In this instance, the inertia of the entire system is expressed as

Therefore, , , , and can be derived in the manner described below:

For computational convenience, the THAUV design assumes symmetry in three planes, where and are diagonal matrices, and . Let and .

In this instance, the inertia matrix is expressed as

From Equations (3)–(50), we obtain

The inverse of the inertia matrix is denoted as

To summarize, the equations governing the motion of the THAUV in three-dimensional underwater space are formulated as presented below:

The comprehensive moment and force are expressed as follows:

Here, contains the hydrodynamic forces and the thrust of the propellers; contains the hydrodynamic moment and the propeller torque.

To summarize, the equations that govern the dynamics of the THAUV in three-dimensional underwater space are outlined below.

Table 1 provides an extensive explanation of the symbols utilized in the aforementioned equations.

Table 1.

Descriptions of symbols of the above equations.

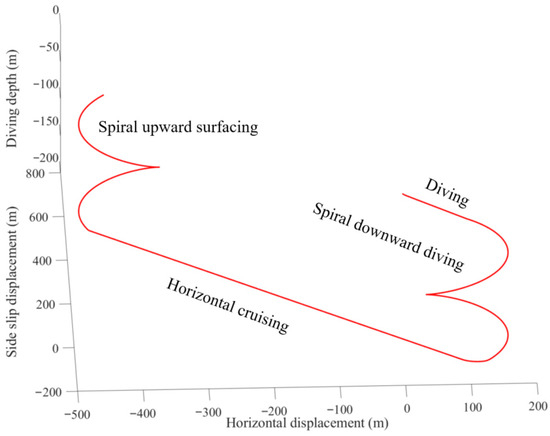

The motion mode of the THAUV in this study involves the coordinated use of the buoyancy engines, rotary rollers, elevators, and thrusters to achieve various preset objectives. Figure 4 shows the trajectory of the THAUV in space. The motion process is divided into four stages: Stage 1: The buoyancy engines draw in water, reducing the buoyancy force acting on the vehicle, which enables downward motion within the vertical plane. Stage 2: The rotary rollers are activated in coordination with the left thruster, generating a downward spiral motion. Stage 3: The buoyancy engines and rotary rollers return to their initial positions, the right thruster is activated, and the elevator deflection is adjusted to achieve horizontal-plane cruise. Stage 4: The buoyancy engines expel water to increase the buoyancy force, while the right thruster is switched off to produce a spiral upward motion.

Figure 4.

Space motion trajectory of THAUV.

The THAUV operates in two primary modes: gliding motion driven by its buoyancy engines, and horizontal cruising or steering motion powered by its thrusters. The combined action of the buoyancy engines and elevators enables the vehicle to dive and surface in the vertical plane. Additionally, by coordinating the buoyancy engines, elevators, and thrusters, the vehicle can maintain a fixed-depth cruise or adjust its heading for directional control.

In this paper, the gliding motion of THAUV in the vertical plane is mainly taken as the research model, and its kinematic equations in the vertical plane can be obtained by simplifying the above equations of motion in space as follows:

4. Hydrodynamic Analysis

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) is widely used in the development of underwater vehicles due to its low cost, high accuracy, and rapid computation. As an external control surface, the elevator plays a critical role in regulating the motion attitude of an underwater glider. By adjusting the elevator’s deflection angle, the hydrodynamic forces acting on the vehicle can be modulated, enabling precise control of underwater motion.

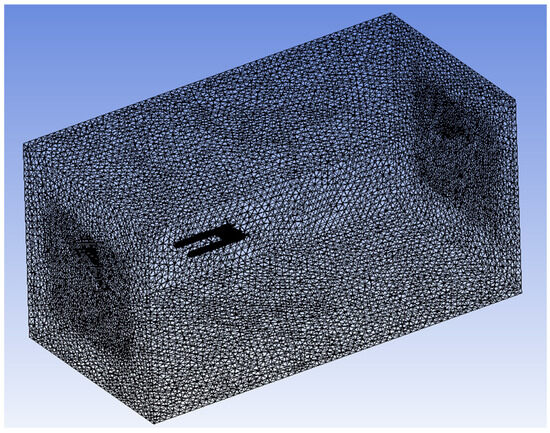

The computational fluid domain is a rectangular volume measuring 14 m in length and 6 m in both width and height, with the inlet boundary positioned 5 m from the THAUV’s center of buoyancy. The k–ω shear stress transport (SST) model was employed as the turbulence model in the CFD simulations [19], an approach widely adopted for submerged vehicle analysis. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) provides an efficient and rapid simulation method, allowing complex experimental processes to be completed in minimal time and at reduced cost, thereby accelerating research progress. The simulation results were used to investigate the flow field distribution around the HTAUV. Given the complex geometry of the HTAUV, an unstructured mesh was generated for the CFD domain, consisting of approximately 3,790,000 grid elements, with the near-wall region refined to maintain Y+ < 1. The CFD simulation conditions are as follows: the inlet velocity ranges from 0.5 m/s; the angle of attack varies from –20° to +20° in 2° intervals; and the elevator deflection angle ranges from –20° to +20°, also in 2° intervals. The computational domain, featuring an unstructured grid, is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The computational fluid domain and mesh.

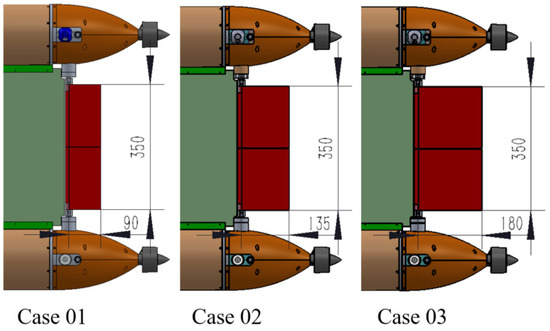

This study evaluates the effect of elevator size on the hydrodynamic forces acting on the THAUV and assesses the resulting impact on underwater motion through comparative analyses. Figure 6 shows the elevator geometries: Case 01 has a width of 90 mm, Case 02 has 135 mm, and Case 03 has 180 mm, while the total elevator length remains constant at 350 mm.

Figure 6.

Dimensions of elevators.

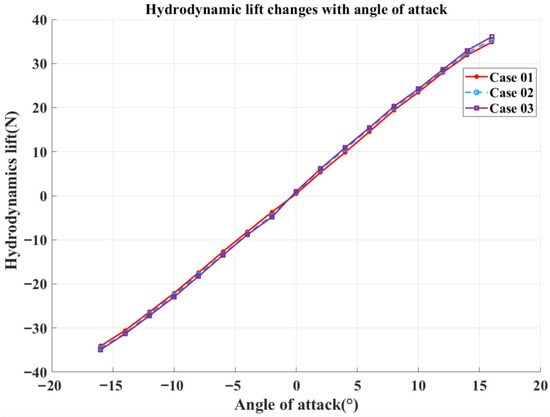

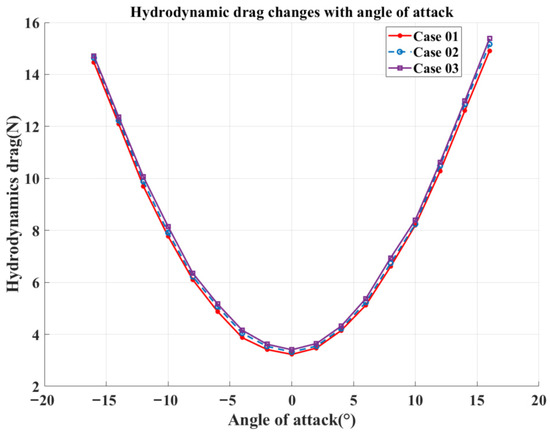

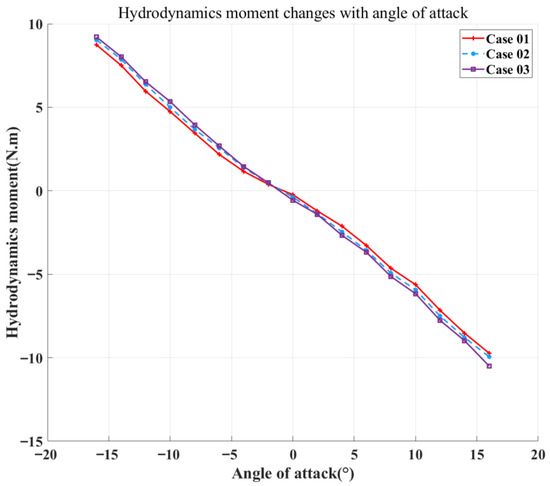

At a fixed elevator deflection angle and inlet velocity, both hydrodynamic moment and lift vary linearly with the angle of attack. Figure 7 compares the hydrodynamic lift for Case 01, Case 02, and Case 03. Figure 8 presents the corresponding hydrodynamic drag, and Figure 9 shows the hydrodynamic moment for the three cases. The simulations were conducted with an elevator deflection angle of 0° and a velocity of 0.5 m/s. Since variations in elevator width produce only minor changes in the THAUV’s total wetted surface area, the resulting hydrodynamic differences among the three cases are insignificant when the elevator deflection angle is set to zero.

Figure 7.

Hydrodynamic lift (angle of attack).

Figure 8.

Hydrodynamic drag (angle of attack).

Figure 9.

Hydrodynamic moment (angle of attack).

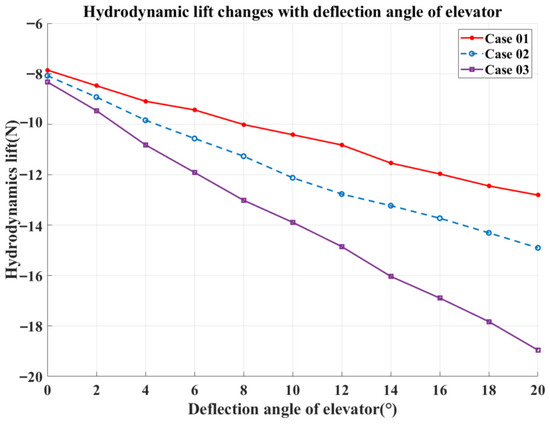

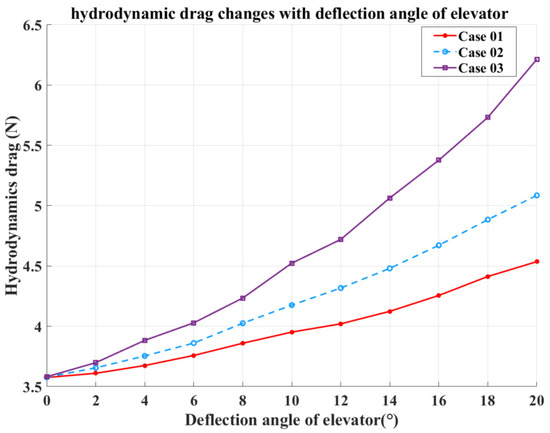

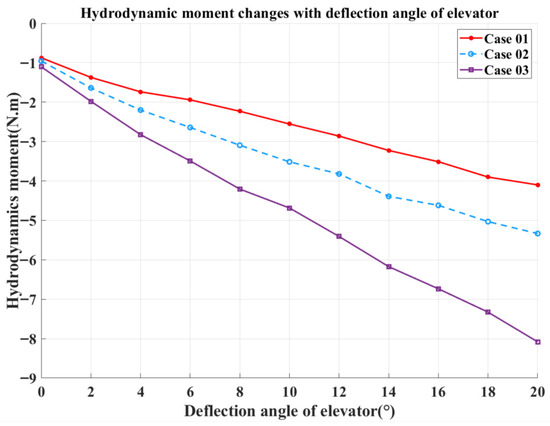

Due to the vortex wake generated by the THAUV’s fixed wing, a positive elevator deflection angle is required during diving to maintain attitude stability, while a negative deflection angle is applied during surfacing [20]. At a fixed angle of attack and inlet velocity, the hydrodynamic forces vary linearly with elevator deflection angle. Figure 10 compares the hydrodynamic lift for Case 01, Case 02, and Case 03. Figure 11 shows the corresponding hydrodynamic drag, and Figure 12 presents the hydrodynamic moment for the three cases. The simulations were conducted with an angle of attack of +4° and an inlet velocity of 0.5 m/s. In the CFD simulations, hydrodynamic forces were evaluated with respect to the THAUV’s center of buoyancy, while the elevator is positioned at the tail, far from this reference point. Consequently, elevator deflection produces a substantial and highly pronounced influence on the hydrodynamics of the THAUV.

Figure 10.

Hydrodynamic lift (deflection angle of elevator).

Figure 11.

Hydrodynamic drag (deflection angle of elevator).

Figure 12.

Hydrodynamic moment (deflection angle of elevator).

Based on the hydrodynamic responses shown in Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12, it can be concluded that as the elevator deflection angle increases, the hydrodynamic forces exhibit an approximately linear growth. Accordingly, the dependence of the hydrodynamic forces on the elevator deflection angle is formulated through the following expressions:

In these expressions, and denote the hydrodynamic lift parameters, where corresponds to the lift parameter at an angle of attack of 0; represents the component associated with the elevator deflection angle; represents the deflection angle of the elevator. Similarly, and refer to the hydrodynamic drag parameters, and indicating the drag parameter related to elevator deflection. and denote the hydrodynamic moment parameters, and is the moment parameter attributable to the elevator deflection angle.

5. Simulation Results

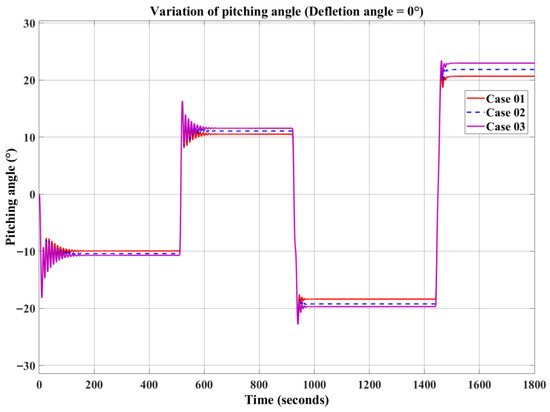

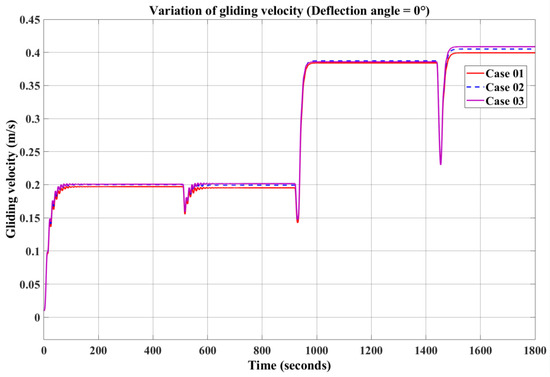

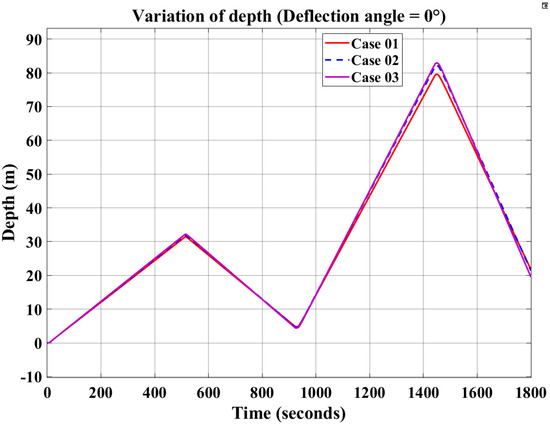

Based on the simplified gliding motion Equations (94)–(107) described above, three different cases were simulated and analyzed, using buoyancy variation and elevator deflection angle as input parameters. Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17 and Figure 18 present a comparison of the simulation results under these cases.

Figure 13.

Variation in pitching angle (deflection angle of elevator = 0°).

Figure 14.

Variation in gliding velocity (deflection angle of elevator = 0°).

Figure 15.

Variation in depth (deflection angle of elevator = 0°).

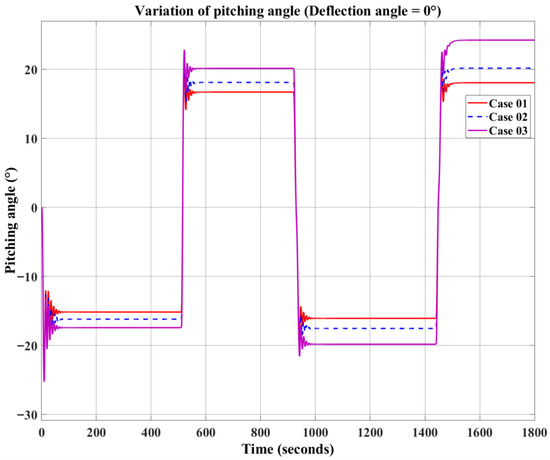

Figure 16.

Variation in pitching angle.

Figure 17.

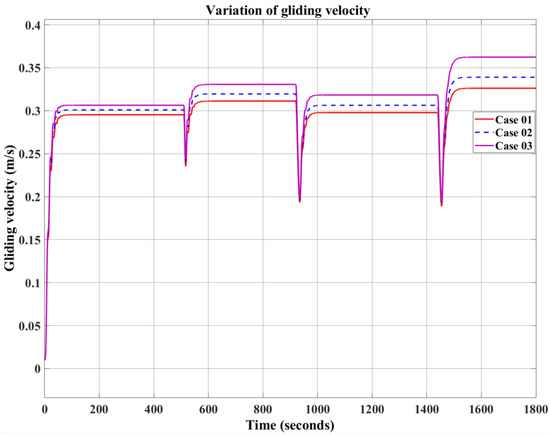

Variation in gliding velocity.

Figure 18.

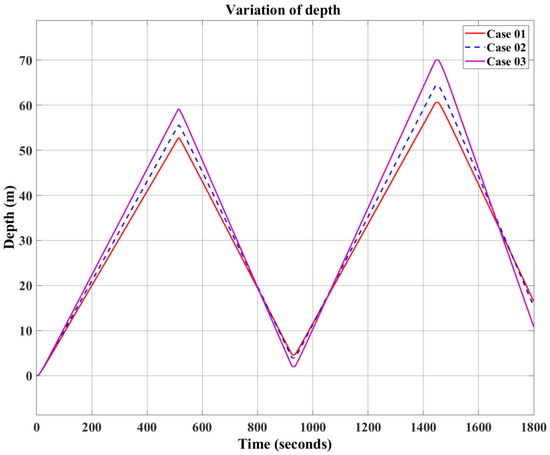

Variation in depth.

The CFD results indicate that larger elevator widths generate stronger hydrodynamic forces on the THAUV. As a result, in the motion simulations with fixed buoyancy, the THAUV exhibits improved glide performance, with all glide parameters increasing as the elevator width is enlarged. As shown in Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15, the results for pitch angle, glide speed, and glide depth are evaluated with buoyancy as the input. From the comparison curves of the three cases, it is observed that the parameters of Case 03 are significantly larger than those of Case 01. While the parameters of Case 03 are slightly larger than those of Case 02, the differences between these two cases are relatively minor.

Figure 16, Figure 17 and Figure 18 present a comparison of the simulation results for gliding parameters under the two input conditions, where both buoyancy and elevator deflection angle are varied. The simulations consider two work cycles, each with the same buoyancy, while the elevator deflection angle in the second cycle is twice that of the first. The results clearly show that elevator deflection significantly affects the gliding parameters: increasing the deflection angle leads to higher pitch angle, glide speed, and glide depth.

6. Conclusions

This study investigates a novel THAUV, an underwater monitoring vehicle equipped with two buoyancy engines, two rotary rollers, two thrusters, and a pair of elevators as its primary propulsion and control mechanisms. A full-space motion model and a simplified vertical-plane gliding model of the THAUV are developed. The effects of elevator widths on the hydrodynamic forces and gliding performance of the THAUV are analyzed.

Hydrodynamic and motion simulations are conducted using ANSYS2019 and MATLAB2020 SIMULINK, and the impact of the elevator on gliding performance is assessed through comparative analysis of the results.

In the CFD simulations, when the elevator deflection angle is 0°, the hydrodynamic forces increase with elevator width; among the three cases, Case 03 exhibits the largest hydrodynamic force, although the differences between the cases are relatively small. When the elevator deflection angle changes, the hydrodynamic forces change significantly and generally show an approximately linear relationship with the deflection angle.

Consequently, a wider elevator generates greater hydrodynamic forces, which directly translate into improved gliding performance, including increased pitch angle, glide speed.

In the motion simulation stage, the gliding motion in the vertical plane was analyzed. When the elevator deflection angle was zero, the difference between Case 03 and Case 01 was the most pronounced, while Case 02 produced results comparable to Case 03, showing no significant distinctions. However, when the elevator deflection angle was non-zero, the gliding performance improved substantially with increasing elevator width. These results indicate that enlarging the elevator can effectively enhance gliding performance.

Nonetheless, a larger elevator does not inherently ensure superior overall performance; structural limitations, energy consumption, and maneuverability must also be taken into account. Therefore, the elevator design for the THAUV requires a balanced consideration of width along with these additional factors. Future research will further investigate these influences to achieve an optimized THAUV design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H., D.-W.J. and P.H.N.A.; methodology, J.H.; software, J.H., D.-W.J., P.H.N.A. and K.Z.; validation, H.-S.C., M.T.V. and R.Z.; formal analysis, J.H. and K.Z.; investigation, J.H. and D.-W.J.; resources, J.H. and H.-S.C.; data curation, J.H., K.Z. and D.-W.J.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H.; writing—review and editing, D.-W.J., H.-S.C., M.T.V., R.Z. and P.H.N.A.; visualization, J.H. and K.Z.; supervision, D.-W.J., P.H.N.A. and H.-S.C.; project administration, J.H. and R.Z.; funding acquisition, J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by “A RESEARCH ON SMALL, HIGH-SPEED MECHANICALLY DRIVEN BIONIC ROBOTIC FISH, grant number FLKJ,2024AAG3021” and the APC was funded by “Chongqing Fuling District Science and Technology Bureau” and was also supported by the Scientific and Technological Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission for Young Scholars, “RESEARCH ON INTELLIGENT BIONIC UNDERWATER MONITORING ROBOT SYSTEM IN THE YANGTZE RIVER BASIN, grant number KJQN202501417” and by the Scientific Research Start-up Fund of Yangtze Normal University, “RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT OF UNDERWATER INTELLIGENT ROBOTIC EQUIPMENT, grant number 010730184”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all members of the Korea Maritime University Intelligent Robot & Automation Lab.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| THAUV | Twin Hybrid Autonomous Underwater Vehicle |

| AUV | Autonomous underwater vehicle |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| UG | Underwater glider |

| DOF | Degrees-of-freedom |

| HAUV | Hybrid Autonomous Underwater Vehicle |

| DVL | Doppler Velocity Logger |

| CTD | Conductivity-Temperature-Depth |

| USBL | Ultra-Short Baseline |

| OCS | Optical Communication System |

References

- Petritoli, E.; Leccese, F. Autonomous Underwater Glider: A Comprehensive Review. Drones 2025, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, R.B.; Huvenne, V.A.I.; Le Bas, T.P.; Murton, B.J.; Connelly, D.P.; Bett, B.J.; Ruhl, H.A.; Morris, K.J.; Peakall, J.; Parsons, D.R.; et al. Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs): Their past, present and future contributions to the advancement of marine geoscience. Mar. Geol. 2014, 352, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Choi, H.-S.; Jung, D.-W.; Choo, K.-B.; Cho, H.; Anh, P.H.N.; Zhang, R.; Kim, J.-Y.; Ji, D.; Park, J.-H. Analysis of a New Twin Hybrid Autonomous Underwater Vehicle. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makdah, A.A.R.A.; Daher, N.; Asmar, D.; Shammas, E. Three-dimensional trajectory tracking of a hybrid autonomous underwater vehicle in the presence of underwater current. Ocean Eng. 2019, 185, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, D.-H.; Choi, H.-S.; Kang, J.-I.; Cho, H.-J.; Joo, M.-G.; Lee, J.-H. Design and control of hybrid underwater glider. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2019, 11, 168781401984855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graver, J.G.; Leonard, N.E. Underwater glider dynamics and control. In Proceedings of the 12th International Symposium on Unmanned Untethered Submersible Technology, Durham, UK, 27 August 2001; pp. 1710–1742. Available online: https://www.princeton.edu/~naomi/UUST02_post.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Bhatta, P.; Leonard, N.E. Nonlinear gliding stability and control for vehicles with hydrodynamic forcing. Automatica 2008, 445, 1240–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, K.; Arshad, M.R. Dynamic modeling and characteristics estimation for USM underwater glider. In Proceedings of the Control and System Graduate Research Colloquium (ICSGRC), Shah Alam, Malaysia, 27–28 June 2011; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Siregar, S.; Trilaksono, B.R.; Hidayat, E.M.I.; Kartidjo, M.; Habibullah, N.; Zulkarnain, M.F.; Setiawan, H.N. Design and Construction of Hybrid Autonomous Underwater Glider for Underwater Research. Robotics 2023, 12, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Choi, H.-S.; Jung, D.-W.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, M.-J.; Choo, K.-B.; Cho, H.-J.; Jin, H.-S. Design and Motion Simulation of an Underwater Glider in the Vertical Plane. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameer, Y.; Kamal, U.; Memon, A.Y. Design of X-rudder AUV’s Motion Control using Sliding Mode Control with Optimal Rudder Allocation Technique. In Proceedings of the 2022 19th International Bhurban Conference on Applied Sciences and Technology (IBCAST), Islamabad, Pakistan, 16–20 August 2022; pp. 938–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Y.; Bhattacharyya, S.K.; Idichandy, V.G. CFD approach to modelling, hydrodynamic analysis and motion characteristics of a laboratory underwater glider with experimental results. J. Ocean Eng. Sci. 2017, 2, 90–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, D.; Song, B.; Pan, G.; Yuan, Z.; Li, J. Winglet effect on hydrodynamic performance and trajectory of a blended-wing-body underwater glider. Ocean Eng. 2019, 188, 106303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.Y.; Ovinis, M.; Hashim, F.B.M.; Maimun, A.; Ali, S.S.A.; Ahmed, S.A. Investigation on the dynamic stability of an underwater glider using CFD simulation. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Underwater System Technology: Theory and Applications (USYS), Penang, Malaysia, 13–14 December 2016; pp. 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, L.M.; Msomi, V. Hydrodynamic analysis of an underwater glider wing using ANSYS fluent as an investigation tool. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 45, 5456–5461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graver, J.G. Underwater Gliders: Dynamics, Control and Design. Ph.D. Thesis, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gören, S. Underwater Gliders: Modeling, Control and Simulation Studies 1. Master’s Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fossen, T.I. Handbook of Marine Craft Hydrodynamics and Motion Control, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-119-99149-6. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, Y.; Bhattacharyya, S.K.; Idichandy, V.G. CFD Approach to Steady State Analysis of an Underwater Glider. In Proceedings of the 2014 Oceans, St. John’s, NL, Canada, 14–19 September 2014; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J. Simulation Study on a New Hybrid Autonomous Underwater Vehicle with Elevators. Proc. Eng. Technol. Innov. 2023, 25, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).