Abstract

Offshore pipelines are commonly used for the transportation of oil and gas from offshore to near-shore facilities in the oil and gas industry. In ocean environments, the wave- and current- induced pore-water pressure within the seabed, and the associated seabed liquefaction and local scour around pipelines, are widely recognised as among the key factors in the design of offshore pipelines. In this paper, a series of wave flume experiments were carried out on the three-dimensional (3D) scouring around a pipeline. In the experiment, in addition to the measurement of hydrodynamic characteristics and local scour, the pore-water pressure within a sandy seabed was measured. Both waves and currents were considered with different incident angles to the pipeline. This study focuses on the relationship between the variation in pore-water pressure and the development of the scouring process around the pipeline, as well as the evolution of the 3D scouring morphology near the pipeline. The experimental results show that the pore-water pressure exhibits significant changes (up to 12.5% of ) in the beginning stage of the scouring process, especially in the area below the pipeline, where the influence of scouring on pore-water pressure is most obvious.

1. Introduction

The stability of submarine pipelines is a critical concern in offshore oil and gas engineering, particularly in complex seabed topographies and under hydrodynamic conditions. As reported in the literature, pipeline failures, such as pipeline sinking or floatation, structural buckling, and subsequent hydrocarbon leakage [,], can occur due to severe marine loading and foundation instability. In addition to the stability of a submarine pipeline, leakage of the pipeline is another critical issue in the operation of the project. The techniques (transient-test-based techniques) have been used for detecting pipeline leakage. These have been tested in the laboratory and refined in real pipe systems [,,,,]. These real-life incidents underscore the necessity of ensuring the long-term stability of sub-sea pipelines to ensure both environmental protection and sustainable energy development.

Scour is a prevalent phenomenon in coastal and ocean engineering that can significantly undermine the stability of sub-sea infrastructures. It is a complex, multi-phase physical process governed by the interactions among fluids, seabed soils, and structures. When ocean waves and current propagate over a pipeline, boundary layer separation generates vortices that sharply increase bed shear stress. Once the critical threshold for sediment motion is exceeded, sediment particles are entrained and local scour begins. Progressive scour can lead to pipeline suspension and complete loss of seabed support, resulting in sagging, vortex-induced vibrations, and fatigue failure. As the suspended section under the pipeline develops, the vortex intensity increases non-linearly, further accelerating the scouring process [,]. Therefore, understanding the characteristics of the flow field and local scour mechanisms around pipelines during the design process is of great significance in enhancing their stability and protection.

Early studies of pipeline scour relied mainly on two-dimensional flume experiments, which measured local scour profiles on a plane perpendicular to the pipe axis, without considering the lateral variation characteristics of the scour beneath the pipe. These studies have provided valuable information on the onset of scouring, scouring mechanisms, scouring depth, and the time scale of local scouring through both physical and numerical modelling [,,,,]. For instance, Van Beek and Wind [] established a mathematical model for local scouring around submarine pipelines. Liang and Cheng [] proposed a numerical model for riverbed scouring to predict the scouring of offshore seabed pipelines. Zhang et al. [] investigated the scour characteristics of free-spanning pipelines in silty and sandy seabeds through two-dimensional regular wave experiments. However, 2D models inherently fail to capture the non-uniform scour development along the pipeline length, limiting their applicability to real marine conditions. This limitation has prompted a gradual shift in the research paradigm from a two-dimensional to a three-dimensional space to more thoroughly reveal the complex mechanisms of pipeline scour.

In reality, the scour beneath the pipelines develops in a fully three-dimensional manner [,]. Scouring progresses not only vertically but also laterally along the pipeline, and the scour rate often differs on either side, producing a free span that increases stress on the arch shoulders. The propagation rate of these shoulders is a critical parameter for assessing the stability of the pipeline. Several physical and numerical investigations have examined the three-dimensional characteristics of pipeline scouring. Frame and Cheng [] analysed the development of three-dimensional scour beneath rigid pipelines under wave action through physical model tests, including the temporal and spatial evolution of scour depth, width, and morphology. Cheng et al. [] conducted three-dimensional scouring tests under steady flow conditions below pipelines, studying the development rate and depth of the scour pits. Wu and Chiew [] investigated the experimental results of three-dimensional scouring of submarine pipelines under unidirectional flow in clear water conditions. Later, Zang et al. [] further explored the relationship between local scour development and the onset of vortex-induced vibrations for pipelines embedded in silty seabeds under steady flow conditions. Furthermore, Cheng et al. [], Zhu et al. [] and Sui et al. [,] systematically examined the evolutionary processes and lateral shoulder migration features of three-dimensional scour around pipelines under steady flow, wave action, and combined loading conditions. In the above studies, the pore-water pressure and the associate seabed seepage were not considered. Despite these efforts, the mechanisms that govern the coupled fluid–sediment–structure interactions remain incompletely understood.

In addition to the local scour around pipelines, the response of seabed soil—especially wave- and current-induced pore pressures and the potential seabed liquefaction in the vicinity of a pipeline—plays a vital role in pipeline stability. To date, extensive studies have been conducted on the response of soil around pipelines caused by waves and its influence on liquefaction around pipelines [,]. Among these, Teh et al. [] reported the experimental results for the stability of a pipeline in a liquefied seabed using conventional wave flume tests. Zhao et al. [] examined wave-induced pore-water pressure around a pipeline. However, the interaction between local scour and the dynamic pore-water pressure field has received limited attention. Recently, Yang et al. [], Gao et al. [], Xu et al. [], Chen et al. [], and Sun et al. [] focused on the dynamic response of pore water pressure within the wave–seabed–pipeline interaction system, yet they did not fully incorporate the temporal evolution of the scour process.

During the scouring process around submarine pipelines, the coupled deformation of the soil skeleton and pore-water alters the seepage field, producing high-pressure gradients near the scour hole edges []. Currently, only limited studies have considered the influence of seepage on sediment transport and scouring [,]. Recently, ref. [] proposed an integrated OpenFOAM model (PORO-FSSI-SCOUR-FOAM) by including seabed seepage in the scour model and demonstrated the impact of soil response on the development of the scour process. These studies were limited to numerical simulation, yet experimental validation remains scarce. The relationship between pore-water pressure and local scour around pipelines remains unclear and requires verification and clarification through reliable experimental data. In summary, existing experimental studies on scour evolution and pore-water pressure response remain largely isolated.

To date, a comprehensive and systematic framework integrating these two phenomena (pore-water pressure and scour) around pipelines has not been established. Therefore, further in-depth research is required to elucidate the coupled mechanisms between local scour and pore water pressure dynamics.

Table 1 summarises the previous experimental studies for wave- snd current-induced pore pressures and local scour around pipelines. The table includes a comparison between the previous studies and the present work. To fill in the research gaps, this study specifically aims to cover the following areas:

Table 1.

Comparison between the present work and previous studies.

- (1)

- This study investigates the evolutionary characteristics of the three-dimensional scouring morphology in the vicinity of a submarine pipeline under the combined action of waves and currents. Specifically, it focuses on the longitudinal expansion process of scour holes and their spatial evolution laws under the condition of oblique incoming flow.

- (2)

- This study investigates the relationship between the development of the local scour process beneath the pipeline and the dynamic pore-water pressure, along with the specific characteristics of the pore-water pressure at different stages of scour.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows: the experimental design including the facility, setting, and procedure, is outlined in Section 2. The results and discussions—accounting for hydrodynamics, scour profiles, pore-water pressure variations, and the relationship between pore-water pressure and local scour profile—are provided in Section 3. Finally, the key findings and limitations of the work are summarised in Section 4.

2. Experiment Design

2.1. Experimental Facility and Setup

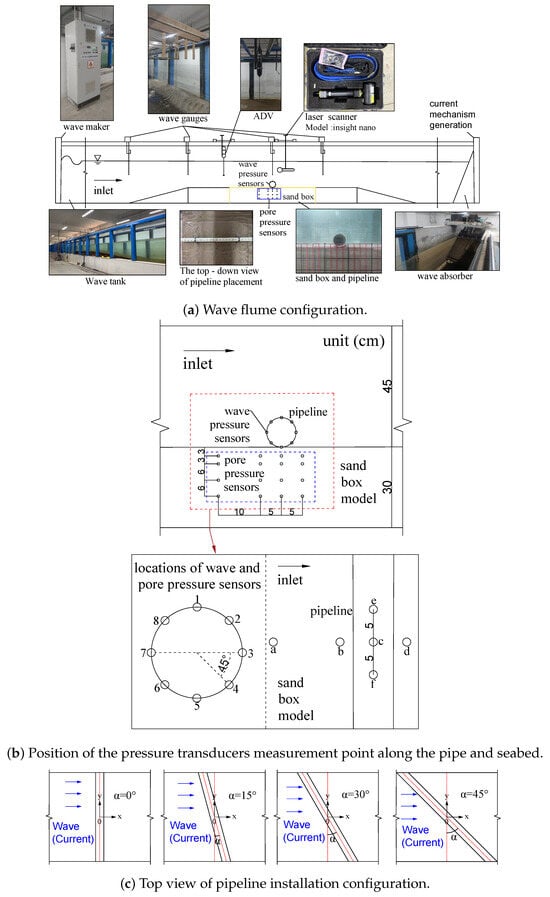

In this study, physical model experiments on three-dimensional (3D) scouring beneath a pipeline were carried out in the wave flume at the Shandong Jiaotong University Port and Navigation Hydrodynamics Laboratory. The flume is 50 m long, 1.2 m wide, and 1.3 m deep, as shown in Figure 1. The bottom of the wave flume is made of rigid impermeable materials, and transparent acrylic observation panels are installed on both sides to monitor the experimental process. At the upstream end of the flume, a piston-type wave generator is equipped, and its control system adopts the TD-BL10 wave and current control device developed by Tianjin University (China), which can generate regular waves and random waves with a period of 1.0∼4.0 s and a maximum amplitude of 0.25 m. To effectively absorb the energy of incident waves and minimise wave reflection, a porous plastic pad inclined wave absorber is installed at the downstream end of the flume. To ensure that the reflected waves from the right-hand-side of the wave flume (Figure 1a) can be ignored in the working area, several pre-tests were performed. Both two-probe and three-probe methods [,,,] were used. Similar pre-tests were performed for the lateral walls. In addition, to minimise lateral wave reflection effects, a significantly reduced pipeline diameter is adopted. This design maintains a pipe-to-flume-width ratio of 0.0525, and a pipe-to-flume-length ratio of 0.00126, effectively reducing direct wall interference with the flow and wave fields surrounding the pipeline.

Figure 1.

Experimental setup: (a) wave flume configuration; (b) position of pressure transducers; and (c) pipeline installation configuration (top view for 3D).

In general, using a 2D wave flume to simulate a 3D problem is a challenge task because of the reflection from the wall. For the ratios of pipe-to-flume-length (width), base on numerous pre-tests, it is found that the effects of lateral wall can be reduced when we focus on the centre part of the pipe. This is one of the limitations of the present work.

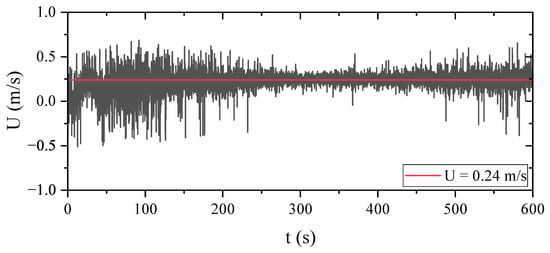

As shown in Figure 1a, the system is also equipped with a current generation device, which can generate a stable bidirectional current with a maximum velocity of 0.70 m/s at a water depth of 0.45 m above the sand tank. The current generation system controls the direction of the flow by adjusting the forward and reverse rotation of the water pump and precisely controlling the flow velocity through frequency regulation. This is performed in order to ensure the stability of current generation. One set of flow velocity variation curves is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Time-averaged velocity profile at 26 cm above the seabed surface ( 0.24 m/s).

The objectives of this paper are to explore the 3D scour around pipelines and the relationship between pore-water pressure and the local scour process. To simplify the problem and obtain fundamental information, only regular wave load is considered in this study, although irregular wave loads can better represent the realistic wave load. For the case of irregular wave loads, the readers can refer to Xu et al. [] for pore-water pressure around two pipelines and Sui et al. [,] for local scour around pipelines.

A sand tank (3.6 m × 1.2 m × 0.3 m) was placed in the middle section of the flume, as shown in Figure 1a. An uniform sand with a median grain size of mm was used to construct the seabed model. On both sides of the sand tank, a horizontal platform of 3.15 m in length and a slope of 1:10 were cast with cement, respectively, as shown in Figure 1a. The pipeline model was made of opaque PVC material with an outer diameter of 0.063 m and a wall thickness of 0.3 mm and laid on the surface of the seabed. In this experiment, the angle between the pipe and the wave/current, denoted as , varied between , , and to simulate different flow attack angles, as shown in Figure 1c. Furthermore, the pipeline was fixed on the seabed surface by means of two supports buried within the seabed. The water depth in the test section was maintained at 0.45 m, and the seabed thickness was kept constant at 0.3 m for all tests. Thus, the hydrostatic pressure () is 4.4 kPa.

To investigate the hydrodynamic loading on the pipeline, eight wave pressure sensors (W1–W8) were circumferentially placed along the surface of the pipeline at intervals of during the experiment. Specifically, the wave pressure transducer (W1) located at the azimuth was used to monitor the variations in dynamic wave pressure in the region directly above the pipeline. Meanwhile, the transducer (W5) positioned at azimuth was used to capture the dynamic wave pressure changes at the interface where the bottom of the pipeline comes into contact with the seabed.

A high-precision underwater three-dimensional laser scanner (model—Insight Nano by Voyis company Canada; scanning range— 0.13–1.0 m, accuracy—0.3 mm in the x- and y-directions, respectively, 0.1 mm in the z-direction, when the water depth is less than 0.5 m) and micro-pore-water pressure sensor arrays are used to synchronously monitor the morphological evolution of the scouring pit and the dynamic response of pore-water pressure. Among these, the laser scanner was used to scan the the topography of the seabed during the scour process. Four flow direction angle conditions from to are designed in the experiment, and the entire scouring process is recorded in real time by a camera. Four wave gauges (G1–G4, Model—YWH203-D by Nanjing Intelligent Technology Co., Ltd. Nanjing, China; with a range—0 to 0.60 m, accuracy—±0.15%) were installed to monitor free-surface fluctuations. Gauges G1 and G2 were placed at the front slope and platform area, respectively, to measure incident waves; G3 was positioned directly above the pipeline to capture wave–structure interactions; and G4 was located 1.3 m downstream of the pipeline to record the wave field in the wake region (see Figure 1a). In addition, an ADV (Acoustic Doppler Velocimeter, by Nortek AS, Norway; range—±1.4 m/s, accuracy—±0.5% of the measured value plus ±1 mm/s) is installed 1.3 m in front of the pipeline to measure changes in flow velocity, with its probe 0.3 m above the seabed surface.

In the experiment, as shown in Figure 1b, 16 pore-pressure transducers (; Model—CY303 by Chengdu Keda Shengying Technology Co., Ltd., China; range —0–30 kPa, accuracy—±0.1%) were embedded in the seabed at depths of 3 cm, 6 cm, 12 cm, and 18 cm below the surface, extending from the region upstream of the pipeline to directly beneath it. All pore pressure transducers were fixed on a custom-designed rigid frame to prevent displacement. Additionally, eight (8) wave pressure transducers (Model—CY302 by Chengdu Keda Shengying Technology Co., Ltd., China; range —0–20 kPa, accuracy—±0.1%) were evenly distributed along the pipeline circumference at its midsection to measure the dynamic pressures acting on the surface of the pipe, with transducer No. 5 located at the seabed level. The 3D laser scanner was used after each test to capture the post-scour seabed topography with a scanning range of 0.13–1.0 m.

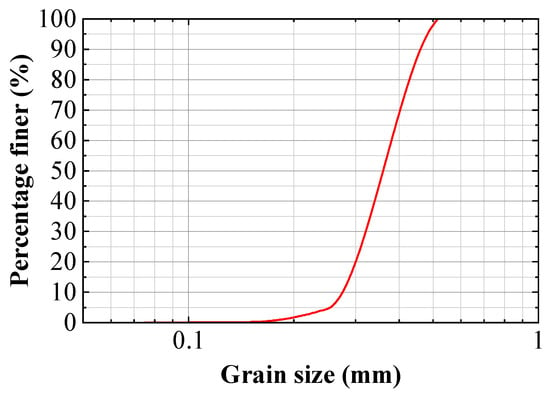

2.2. Soil Sample

Before the experiment, the soil samples were sieved and analysed to determine their particle size distribution curve (see Figure 3), where represents the median particle size, is the uniformity coefficient, and is the curvature coefficient. Subsequently, the soil was filled into the sand tank and water was injected into the water tank to saturate the soil. The soil was consolidated and reached a fully saturated state. As in wave-flume studies, the prototype soil stress levels of the field seabed could not be reproduced. This similarity of soil stress can only be achieved through centrifuge modelling in a higher acceleration environment []. Therefore, in this study, the scaling law of soil particles was not applied. This is the limitation of the wave flume tests for scour process and wave–soil–structure interaction system.

Figure 3.

The grain size distribution of the soil sample: = 0.37 mm, = 0.26 mm, = 0.32 mm, = 0.40 mm, = 1.52, and = 0.96.

In this study, the dry density () and the specific gravity () are determined in the standard soil laboratory. The permeability coefficient () was obtained through a constant head permeability test facility. The elastic modulus (E) was measured using a triaxial test apparatus. Based on empirical values, the Poisson ratio () of the soil sample was set at 0.3. Consequently, the shear modulus (G) was calculated using the formula . The maximum and minimum void ratios of the soil sample were determined using a relative density test, from which the relative density () was determined. Before the experiment began, a small amount of sand sample was taken and its porosity (n) was measured using the density method. The void ratio was then calculated using the formula . The detailed soil parameters are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Properties of soil sample.

2.3. Experimental Conditions

Regular waves were adopted as input waveforms. The wave height (H) was increased in increments of 0.02 m, starting from 0.06 m and gradually increasing to 0.12 m. The wave period (T) was set at intervals of 0.2 s, specifically 1.4 s, 1.6 s and 1.8 s. Both co-directional and counter-directional steady currents were considered, with current velocity (U) ranging from −0.24 m/s to 0.24 m/s. A total of 40 experimental conditions were performed. To improve the reliability and statistical validity of the experimental data, each test was repeated at least twice to ensure that the obtained results have good repeatability and representativeness.

Since this study focusses only on the fundamental understanding of the physical process in a mild-scale wave flume, we did not consider dismissal of the real situation. The choice of wave and current conditions is based on typical environmental loads and the capacity of the facility. Overall, the selected wave–current condition is 1/20 scale to most nearshore environments.

The details of the tests performed are tabulated in Table 3. In the table, The maximum combined wave–current velocity () is determined by

where is the orbital velocity, which was determined by the second-order wave theory []; d is still water depth (0.45 m in this study); and is the near-bed velocity under combined wave and current loads at 0.01 m above the bed, estimated using the empirical 1/7th power law as [,].

Table 3.

Hydrodynamic conditions for tests.

In Table 3, is the Reynolds number and is the kinematic viscosity of the fluid, with a value of . The Keulegan-Carpenter number (KC) [,] is defined by

where D is the diameter of the pipe, which is 0.063 m in this study.

In Table 3, and are Shields number and critical Shields numbers, respectively. In general, two categories of scour have been classified: the clear-water scour and the lived-bed scour []. This classification is based on the shield number, which is defined as the following [,].

where is the bottom shear stress; is the density of water; f is friction coefficient among grains; and are the draft and lift coefficients, respectively; can be found in (Chien and Wan [] Figure 8.6); g is the gravity acceleration; is specific gravity. The critical Shields parameter () is an important dimensionless index in determining whether sediment particles start to move under the action of water flow, and it is widely applied in the research of sediment transport and bed scouring. When , clear-water scour is occurring, and the sediment will not move away. On the other hand, when , lived-bed scour is occurring, and the sediment was moved away and a scour hole will be formed. The critical Shields number () is determined by the empirical formula [,], as follows.

where g is the gravitational acceleration, with a value of 9.8 m/s2. From (3) and (4), it can be known that the critical Shields parameter of the sand samples in this experiment is 0.034.

Recently, several studies discussed the impact of wave-induced seabed seepage on local scour around offshore pipelines [,,]. In this study, we measured the pore-water pressure and local scour at the same time and attempted to establish the relationship between the pore-water pressure and local scour. This will be discussed in Section 3.4.

In Table 3, the maximum depth of scour (S) varies between zero and 2.5 cm.

2.4. Experimental Process

Prior to testing, the sand was uniformly levelled to a height of 0.3 m above the flume bottom and saturated by water injection for 24 h. The pore-water pressure sensors were soaked in a calibration tank for 48 h before being installed on the custom steel frame. The wave pressure gauges were fixed on the surface of the pipe model according to the experimental design. The wave height gauges, ADV and underwater 3D laser scanner were positioned at their designated locations within the flume. The ADV was calibrated first to determine the frequency range corresponding to the experimental flow velocity.

After completing all preparations, the tests were conducted sequentially under the prescribed hydrodynamic conditions. The current-generation system was activated first. Once the ADV indicated that the flow velocity had stabilised, the wave generator was started to produce the target wave conditions. Subsequently, all data acquisition systems-—including the pressure transducers, wave gauges, and ADV–were simultaneously triggered to begin data recording.

The total scouring duration is set to 1 h. Within this period, the scouring depth tends to stabilise, indicating that the scouring process has reached a balanced state. Therefore, the maximum scouring time in the experiment is controlled at 1 h. Under the sampling rate of 0.01 s, to prevent incomplete wave dissipation due to long-term wave generation from interfering with the flow field, the maximum duration of each wave generation is set at 15 min. According to the experimental requirements, wave generation is continuously carried out until the time required to reach the scouring equilibrium is reached. Specifically, in the first half hour, wave generation is conducted every 10 min, for a total of 3 times; in the second half hour, wave generation is conducted every 15 min, for a total of 2 times. After each wave generation, it is necessary to wait for the water surface to return to stability and then slowly enter the water at a speed that does not disturb the scouring terrain. The entry stops when it reaches a height of approximately 14 cm from the seabed surface. When the depth of the water is greater than the diameter of the pipe, the entry process will not affect the original terrain. To minimise the impact of entry on the terrain, this experiment selects a water depth greater than twice the diameter of the pipe as the operating condition. Then, we entered the flume, carefully remove the pipe, take photos for records, and finally use a terrain scanner to precisely scan the terrain after scouring.

3. Results and Discussions

This section presents a systematic analysis of the experimental results, including the evolution of the seabed scour morphology around the pipeline, the wave profile characteristics, the dynamic wave pressure on the pipe surface, and the response of pore-water pressure in the soil under the action of regular waves (or currents) at different incident angles (, , , ). Since variations in the near-bed flow and dynamic wave pressure strongly affect the soil response, particular attention is given to the temporal and spatial evolution of pore-water pressure within the scoured region. Through this approach, the mechanisms governing the development of pore-water pressure during scour formation are revealed.

The positive x-direction is defined as along the wave propagation direction, and the positive z-direction is vertically upward from the seabed surface. Here, S represents the maximum scouring depth, D is the diameter of the pipe, indicates the water surface elevation, represents the dynamic water pressure, and is its maximum value. The pore-water pressure () represents pressure response induced by dynamic wave loading, with the initial hydrostatic pressure () subtracted.

3.1. Hydrodynamics Around the Pipeline

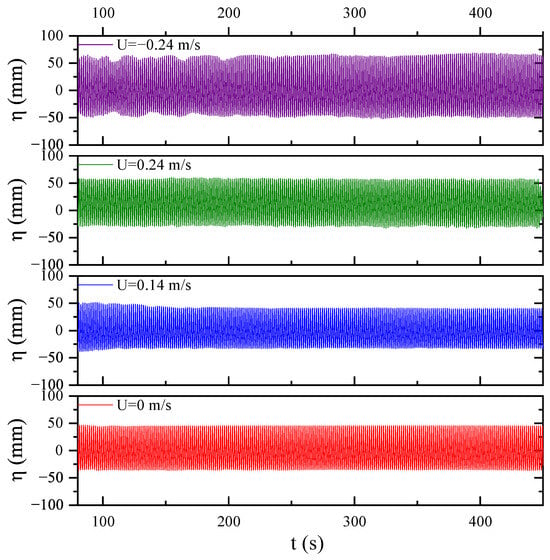

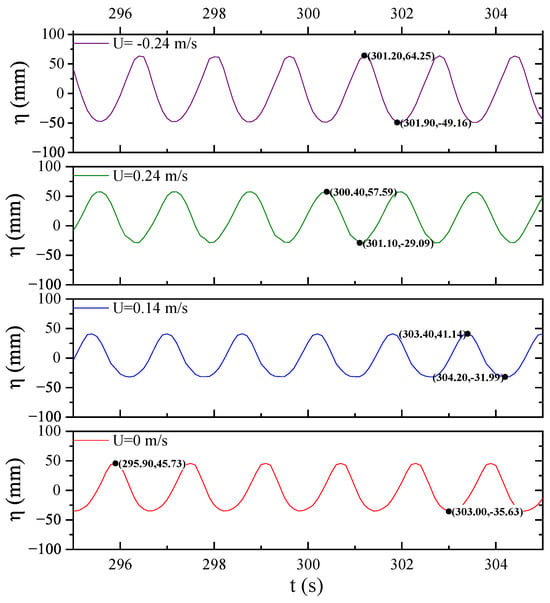

The variations in the wave surface directly above the pipeline were continuously monitored using the wave gauge G3. Figure 4 depicts the wave profile directly above the pipeline over a certain period under different flow velocity conditions. It can be observed that the wave surface configuration has approached a stable state within this time frame.

Figure 4.

Time-series of wave profiles directly above the pipeline under different flow velocity conditions (H = 9 cm, T = 1.6 s, ).

As is evident from Figure 5, when a forwarded current is introduced, the propagation velocity of the waves increases remarkably. In contrast, when a revised current is imposed, the propagation of the waves is impeded, and the wave amplitude increases substantially. Specifically, under the condition of pure waves without current (), the wave fluctuation range was within [−3.6 cm, 4.6 cm]. Note that the wave height at gauge 3 is less than the incoming wave height ( 9 cm) due to the disturbance of the pipe. When a forwarded current of m/s is included, the fluctuation range changes to [−3.2 cm, 4.1 cm]. When the current velocity increases to 0.24 m/s, the fluctuation range became [−2.9 cm, 5.8 cm]. When a revised current is introduced, the change in wave fluctuations is the most prominent, reaching [−4.9 cm, 6.4 cm], which represents a 39.4% increase compared to the case without flow (as depicted in Figure 5). The experimental findings indicate that the backflow has a profound impact on the wave propagation characteristics and cannot be overlooked in relevant research.

Figure 5.

Wave profile above the pipe under the action of pure wave and wave plus current (H = 9 cm, T = 1.6 s, ; the maximum and minimum values and the corresponding times are marked in the figure).

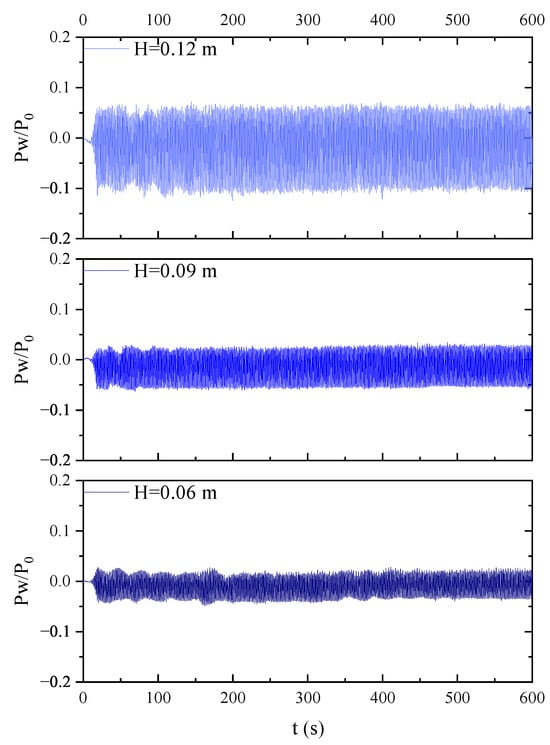

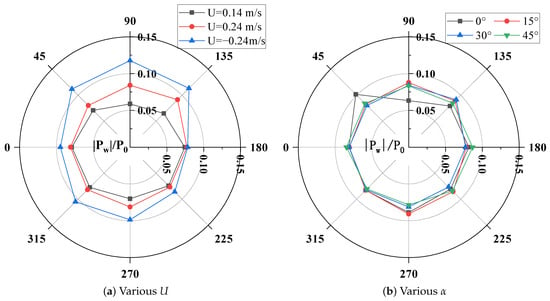

Figure 6 depicts the time-averaged trend of the dynamic wave pressure on the pipeline surface as it varies with the wave height. Evidently, the wave height exerts a notable influence on the wave pressure acting upon the pipeline surface. Figure 7 illustrates the spatial distribution of the maximum dynamic wave pressures along the pipeline surface under the action of regular waves with various wave characteristics, all occurring under the same current-velocity conditions. The coordinate in the figure represents the maximum value of the dynamic wave pressure. When the wave direction was perpendicular to the pipeline axis, the wave-facing side () experienced the highest dynamic pressure, while the leeward side () showed the lowest.

Figure 6.

The time-series of wave pressure acting on the surface of the pipeline under different wave height conditions. (T = 1.6 s, U = 0.24 m/s, ).

Figure 7.

Maximum dynamic wave pressure around the pipeline under regular waves and current conditions. (a) T = 1.6 s, U = 0.24 m/s, , and (b) H = 0.12 m, U = 0.24 m/s, .

As shown in Figure 7a, there is a positive correlation between wave pressure and wave height. That is, the higher the wave height, the higher the dynamic wave pressure generated. Due to the impediment of the pipeline in propagation of wave energy, the maximum wave pressure at the stagnation point at the bottom of the pipeline is higher than at the stagnation point at the top, with a particularly notable manifestation at the position . Figure 7b shows the influence of wave periods, the dynamic wave pressure on the wave-facing side of the pipeline generally increases as the wave period increases. However, at the seabed contact point (270°), the ratio of the maximum dynamic wave pressure to the hydrostatic pressure is 0.13 when the wave period T = 1.8 s. This value is slightly lower than the ratio of 0.14 when the wave period T = 1.6 s. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that the longer period ( s) corresponds to a longer wavelength and a more uniform pressure distribution. There is energy dissipation resulting from the seabed–water flow coupling (more efficient seabed drainage), which leads to a relatively lower dynamic wave pressure in the near-seabed region of the pipeline during this period. It is especially prominent in the shallow water transition zone (), where d is the water depth and L is the wavelength) and in conditions where shear flow is present. The values of () that correspond to ( 1.8 s) and ( 1.6 s) are (0.14) and (0.18), respectively.

Figure 8a depicts the response characteristics of the dynamic pressure on the pipeline surface under the combined action of wave and current. Evidently, when wave and current propagate in the same direction, the dynamic pressure on the pipeline surface increases as the current velocity rises, indicating that the wave–current interaction significantly enhances the flow intensity in the near-bed region. Under reverse-flow conditions, the dynamic pressure attains its maximum value, which is approximately 30–50% higher than that under co-flow conditions. This augmentation is primarily due to the fact that, when the wave and current are in opposite directions, the relative velocity of water particles increases with respect to the pipeline. Meanwhile, the wave profile becomes steeper, and the non-linear characteristics are intensified (as shown in Figure 5), thus leading to a notable increase in the dynamic pressure acting on the pipeline surface.

Figure 8.

Maximum dynamic wave pressures around the pipeline under wave and current. ((a) H = 0.09 m, T = 1.6 s, , and (b) H = 0.09 m, T = 1.6 s, U = 0.24 m/s).

Furthermore, Figure 8b further demonstrates the influence of different incoming-flow angles () on the maximum dynamic pressure of the pipeline surface under the same wave–current combination. The results indicate that, for different values of , the variation amplitude of the maximum dynamic pressure is relatively transducer at the mid-position of the pipeline. Under this setup, the change in the incoming-flow angle has a relatively minor impact on the peak value of the dynamic pressure at the measurement points.

3.2. Scour Topography

The scour morphology data were acquired by a high-precision underwater laser 3D scanner (Figure 1a). In the first half-hour of the scouring process, the scans were performed at 10-min intervals. After 1 h of the scouring process was completed, the final scoured topography was scanned again. A total of four scanning operations were performed throughout the scouring process. Since the area surrounding the pipeline is the primary zone where scouring occurs, to obtain information about the scoured topography beneath the pipeline (the key being to measure the scouring depth beneath the pipeline at each time interval and conduct comparative analyses, so as to establish the relationship between the scouring depth around the pipeline and time), the pipeline was removed prior to each scan. During this operation, every effort was made to minimise the perturbation of the topography. In the following examples, a typical condition was presented for the purpose of control variables.

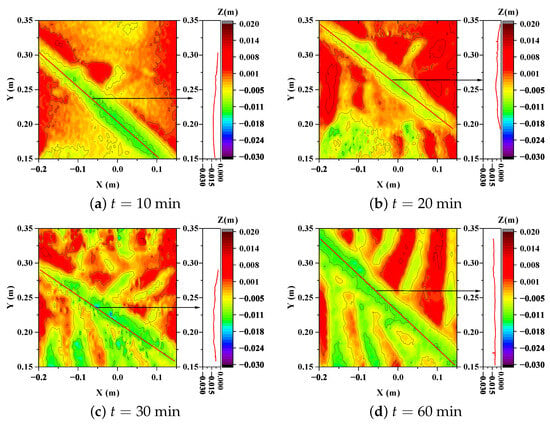

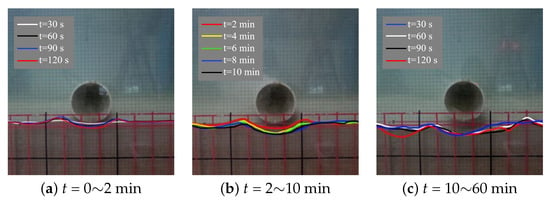

It can be seen in Figure 9 that, within 30 min, the depth of the scuff below the pipeline on the sandy seabed reached a stable state and no remarkable changes occurred thereafter. This phenomenon is in line with the experimental findings of the 2D experiments []. Furthermore, within every 10-min interval, the variations in the scour depth below the pipeline was relatively minor, and its development was rather gradual. This further suggests that the scouring process below the pipeline on the sandy seabed was predominantly concentrated within the initial 10 min and was especially intense. The scouring conditions within the first 10 min will be further demonstrated and analysed in Figure 10. Specifically, this was the case in the longitudinal direction of the pipeline. After 10 min, the longitudinal scouring below the pipeline gradually subsided and finally reached an equilibrium state of the scour depth. At this moment, the scouring effect mainly presented as a lateral expansion, that is, the topographical changes in the areas surrounding the pipeline were more prominent.

Figure 9.

Topographic contour map with accompanying longitudinal profile of scour depth beneath the pipeline. ( m, s, m/s, ).

Figure 10.

Longitudinal topographic section of the area beneath the Pipeline. ( m, s, m/s, ).

Figure 10 shows the development trend of the longitudinal scouring beneath the pipeline during the 1 h scouring process. The results reveal that the maximum scour depth of the pipeline was 0.022 m (), which consistently remained less than the scour depth at the location of the surface pore-water pressure gauge (−0.03 m, ). This suggests that, throughout the entire scouring process, the surface pore-water pressure gauge was not exposed. Furthermore, at t = 10 min, the longitudinal profile of the scour was already below the initial seabed plane (i.e., ), demonstrating that, within the first 10 min of the scouring commencement, the entire pipeline had exhibited a suspended span phenomenon.

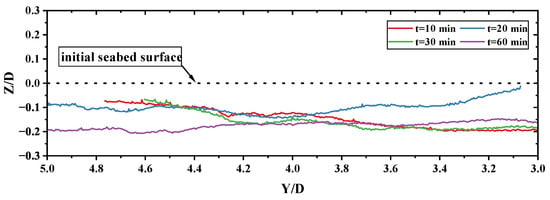

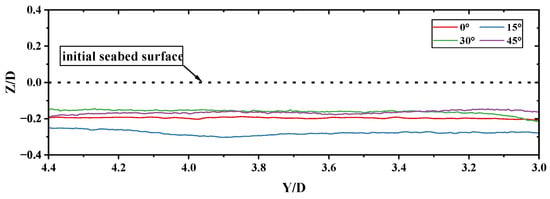

Figure 11 shows the scanned images of the final scouring topography when the pipeline is at different angles () with the direction of wave and current propagation. The results show that, for all tested angles, the most severe scour consistently develops along the pipeline, particularly within the zone directly beneath and beside the pipe. This indicates that the location of the maximum scour depth is generally insensitive to the change in . However, the overall morphological pattern are clearly affected by the relative orientation. For example, when the angle is (that is, the pipeline axis is perpendicular to the direction of wave and current), the scouring area is relatively more concentrated. When the angle gradually increases and enters the oblique inflow state, the scouring area shows a certain lateral expansion trend. The aforementioned phenomenon indicates that, despite the relatively minor influence of the relative orientation of the pipeline to the incoming flow direction on the location of the maximum scour depth, it still exerts a notable impact on the evolutionary process of the overall morphology of the scour pit.

Figure 11.

Pipeline terrain scanning map, with a cross-sectional view of the depth of erosion along the pipe beside it. ( m, s, m/s).

Figure 12 shows the development trend of the longitudinal scouring beneath the pipeline after continuous scouring for 1 h when the pipeline is at different angles with the direction of wave and current propagation. The results indicate that the relative position between the pipeline and the fluid flow direction has no significant impact on the maximum depth of scouring, which fluctuates between −0.02 cm and −0.025 cm (corresponding to an S/D value of approximately −0.32 to −0.4). This suggests that under experimental conditions, the change in the inflow angle does not significantly alter the final depth of the scouring below the pipeline.

Figure 12.

Longitudinal topographic profiles of the areas beneath pipelines at various ( m, s, m/s).

Figure 13 illustrates the alterations in the scour profile (photos) beneath the pipeline during various time intervals of the scouring process. In the figure, to observe the scour depth, a gird of 5 × 5 mm was added on the glass of the wave flume. This was used to compare withe the results of the laser scanning process. In the experiments, the common field condition where pipelines rest on the seabed is simulated. The contact point between the pipeline and the sand bed results in a vertical reaction force at . As is observable from the figure, within the initial 10 min of the scouring progression, the variation in the scour profile is most pronounced. Specifically, within the first 2 min, the scour depth experiences a rapid increase. At this moment, the longitudinal scouring rate beneath the pipeline reaches the peak value throughout the entire process. Although the earliest scour develops beneath the pipe, the observations show that vortex-induced bed shear stress forms rapidly within the first few cycles of wave–current action, and subsequently governs the scour evolution around the pipeline. After 2 min of scouring, the scouring rate gradually declines and the increment amplitude of the scour depth also decreases accordingly. This result is in line with the research findings of Zhang et al. [], which indicate that the scouring of sandy seabeds tends to reach a stable state after 2 min. At approximately at 4 min, the maximum scour depth beneath the pipeline approaches a stable state. That is, the longitudinal scouring process is essentially concluded and the depth of the scour pit no longer exhibits notable changes. Subsequently, the primary mode of scouring evolves into lateral expansion. That is, the scour pit gradually expands in horizontal dimension. The flow of wave–current drives the migration of sediment in the surrounding areas, thereby continuously expanding the scope of the scouring.

Figure 13.

Time evolution of scour depth (a) t = 0∼10 min, (b) t = 2∼10 min (c) t = 10∼60 min. ( m, s, m/s, ).

A further examination of Figure 13c reveals that, as time elapses, by the 30-min mark, the scouring pattern in the vicinity of the pipeline approaches a stable state. The shape and dimensions of the scour pit remain essentially constant. This suggests that, within a 30-min time span, the scouring process has completed its transition from the initial stage to the final configuration. The experimental results suggest that, under the sandy seabed conditions investigated, the scouring rate is high, and the entire scouring process can attain a stable state within 30 min. This result is consistent with the findings of previous studies [,,,]. In particular, the maximum depth of scour beneath the pipeline reaches an equilibrium state within the first 4 min, highlighting the rapid response of the sandy seabed to flow scour and its robust erosion potential. This phenomenon is of substantial significance for understanding the scouring mechanisms surrounding submarine pipelines and evaluating the stability of the pipeline. In particular, during the engineering design phase and subsequent maintenance operations, care should be taken with regard to the implications of the initial scouring stage.

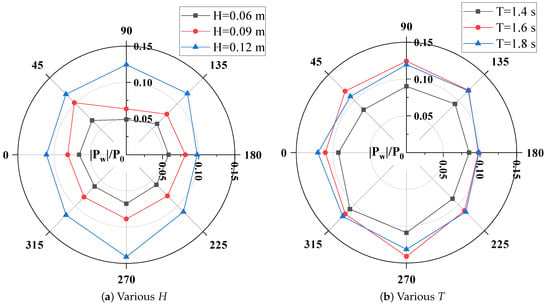

3.3. Pore-Water Pressure in Seabed Areas Around the Pipelines

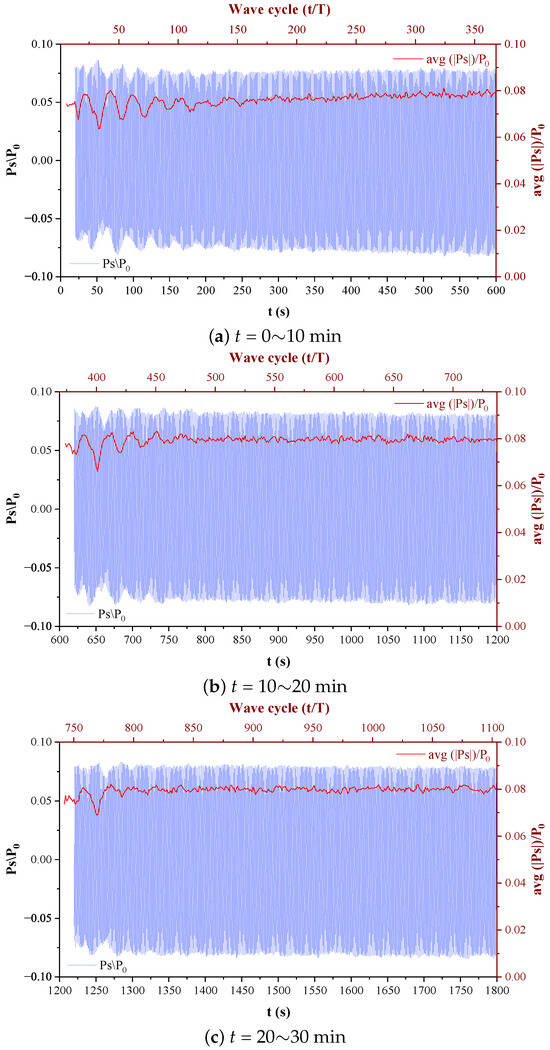

This section is primarily devoted to an in-depth study of the characteristics of pore-water pressure variations around submarine pipelines during the development of scouring under the combined influence of waves and currents. The core of this research lies in unraveling the dynamic response mechanisms of pore-water pressure within the soil surrounding submarine pipelines. Under such conditions, as the scouring phenomenon undergoes a gradual evolution, these mechanisms manifest themselves as developmental changes in pore-water pressure within the scouring pit during its formation. This enables us to identify the evolutionary characteristics of the pore-water pressure at different stages of pipeline scouring. This parameter serves to quantify the additional changes in pore-water pressure induced by external dynamic loads. During tests, the maximum pressure peak recorded during the measurement period is designated as . This is used to assess the extreme pressure response states experienced by the soil during a specific scouring stage. Furthermore, represents the hydrostatic pressure at the surface of the seabed.

In the tests, all scouring processes persisted for 1 h. However, scouring around the pipelines in the sandy seabed was predominantly carried out within the initial 10 min after the scouring began, and the scouring depth generally did not exceed 3 cm. Consequently, this study focuses on analysing the variations in pore-water pressure at a location 3 cm directly below the pipeline within the first 10 min of scouring commencement. Figure 14a shows the overall trends of the pore-water pressure and its amplitude during the first 10 min of scouring. In the figure, the average amplitude magnitude of the pore-water pressure versus wave cycle () is also included and is defined as

where and are the maximum and minimum pore-water pressure within a wave cycle, respectively.

Figure 14.

A time history diagram of pore-water pressure during scouring process: (a) t = 0∼10 min, (b) t = 20∼20 min; (c) t = 20∼30 min. ( m, s, m/s, ).

When the wave action reached directly above the pipeline (approximately 15 s), the sediment surrounding the pipeline began to mobilise, marking the start of the scouring process. When the scouring depth beneath the pipeline approached a stable state (around 4 min), the magnitude of pore-water pressure variations decreased significantly. However, its amplitude gradually fluctuated and increased from around 0.074 to around 0.079. With the subsequent decline in the scouring rate, the scouring depth beneath the pipeline tended to stabilise. The pore-water pressure amplitude remained consistently stable at around 0.079 at 20 min and 30 min (the scouring of the sandy seabed achieved a stable state after 30 min, which aligns with the finding of Xu et al. []), as illustrated in Figure 14b,c. It is noted that there is a gap at the beginning of these figures; this is because we stopped and restarted the wave generation at 600 s and 1200 s to maintain the wave profile. In general, the wave arrived the pipeline after several wave cycles when we restarted the wave generation. Therefore, we include the data from 620 s in Figure 14b and 1220 s in Figure 14c.

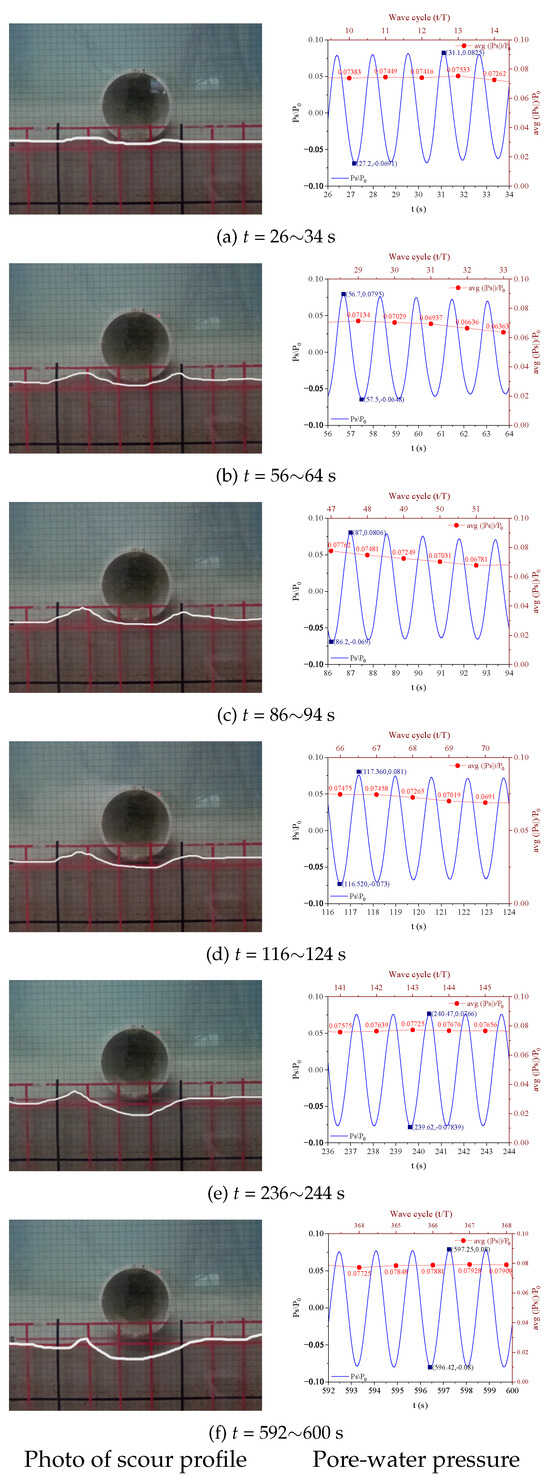

Figure 15a,b present the two–dimensional cross-sectional morphologies at 30 s and 60 s during the scouring process, respectively, together with the evolutionary characteristics of the pressure of the pore-water within two consecutive cycles ( 1.6 s). At the 30 s mark, incipient scouring phenomena become evident in the vicinity of the pipeline. Initial signs of scour pits can be observed in the surrounding area. At this instant, the maximum amplitude of the pore-water pressure reaches 0.08 at 31.1 s. The general fluctuation range is within [−0.07, 0.08], remaining at a relatively high level. This indicates that the soil surrounding the pipeline is experiencing a significant dynamic perturbation. Concurrently, the pore-water pressure exhibits a notable negative value. Its trough value of −0.07 occurs at 27.2 s, reflecting a relatively strong pore-water suction effect. This phenomenon might be attributed to the rapid expulsion of pore-water induced by the shear action of flowing water during the initial stage of scouring, which leads to a transient negative pressure state within the soil mass. Within 60 s, the form of a scour pit has taken an initial shape around the pipeline. At this time, the maximum amplitude of the pore-water pressure is 0.08 (occurring at 56.7 s), and the overall fluctuation range is [−0.07, 0.08]. This represents a significant decline compared to the situation at 30 s, suggesting that the intensity of the dynamic response of the soil around the pipeline weakens as the scouring process progresses. Simultaneously, the magnitude of the negative pore-water pressure also decreases (the lowest value of −0.07 occurs at 57.5 s). The reduction in pore-water suction implies that the pore structure of the soil is approaching stability, the pore-water pressure gradient is diminishing, and the hydrodynamic perturbation is gradually subsiding. These observations collectively indicate that the internal stress state of the soil is undergoing a gradual adjustment process.

Figure 15.

A two-dimensional sectional view of the pipe. (The dimension of one red grid is 5 mm × 5 mm); and a time history of pore-water pressure beneath the pipe during the scouring process. (a) t = 26∼34 s; (b) t = 56∼64 s; (c) t = 86∼94 s; (d) t = 116∼124 s; (e) t = 236∼244 s; and (f) t = 592∼600 s). (H = 0.12 m, s, m/s, ).

Figure 15c,d illustrate the 2D cross-sectional morphologies and the associated pore-water pressure characteristics at 90 s and 120 s during the scouring process. At 90 s, the pore-water pressure exhibits relatively pronounced fluctuations. The peak pressure amplitude reaches 0.08, occurring at 87 s. Within the 47th–51st cycle interval, the amplitude fluctuates in the range of [0.068, 0.078]. Meanwhile, the trough value of the pore-water pressure is −0.069, which appears at 86.2 s. Figure 15c,d show the morphological evolution of the scouring area during this stage. The extent of the scour pit further expands, compared to that at 60 s, and the scouring depth below the pipeline also increases. By 120 s, the peak pressure amplitude decreases to 0.081, occurring at 117 s. Within the 66th–70th wave cycle, the peak pressure amplitude demonstrates a decreasing trend, with the amplitude ranging from [0.069, 0.075]. The minimum value of the pore-water pressure is −0.0731, which is lower than the minimum value at 90 s. The cross-sectional plot reveals that the morphology of the scouring area continues to evolve. The pipeline shows an evident overhanging phenomenon, and the scouring depth beneath the pipeline is approximately 7 mm (each red grid in the cross-sectional plot measures 5 mm × 5 mm). Furthermore, the fluctuation characteristics of the pore-water pressure undergo a transformation. The rate of amplitude decline becomes more gradual and the oscillation range contracts. Overall, this indicates that, although the scouring process persists, its rate of development has decelerated.

Figure 15e,f further unveil the 2D cross-sectional morphologies and the characteristics of the pore-water pressure during the scouring process at stages of 240 s and 10 min (600 s). At the 240 s (Figure 15a), a remarkable dynamic response relationship manifests between the variations in the pore-water pressure and the progression of scouring. The pressure amplitude reaches a peak value of 0.077 at 240.47 s. Within the 141st–145th cycle interval, the amplitude values remain stable within the range of [0.076, 0.077]. Meanwhile, the pore-water pressure reaches its trough value of −0.078 at 239.62 s. The aforementioned results suggest that the water flow perturbation persists at a relatively high level. The intense fluctuations of pore-water pressure continuously drive the migration of soil particles. The cross-sectional diagrams also indicate that the scouring area continues to expand.

As shown in Figure 15a, the scouring depth beneath the pipeline has reached 1 cm, that is, the scouring process is still in a dynamic development phase at this moment. When the scouring process advances to 10 min, instead of declining, the peak pressure amplitude ascends to 0.08 at 597.25 s. Within the 364th–368th wave cycles, see Figure 15f, it exhibits an increasing trend, with an amplitude ranging from [0.07725, 0.07928]. Moreover, the negative value of the pore-water pressure further intensifies, reaching a minimum of −0.08 at 596.42 s. This implies that, as the scouring time lengthens, the interactions between hydrodynamic forces and the soil mass does not diminish. In contrast, because of the continuous evolution of the scouring area’s morphology, the fluctuations of pore-water pressure become more pronounced. Moreover, the increase in the negative pore-water pressure value reflects an enhanced drag effect of the seepage force on the soil particles. As is evident from Figure 15e, compared with the 240-s (4 min) stage, the scouring depth and extent at 10 min developed further. At this time, the depth of penetration below the pipeline is 1.7 cm and reaches 2 cm at the end of the penetration process. The relatively minor change in depth indicates that the scouring process is most intense during the initial 10 min, and the subsequent stages tend to be relatively stable.

Through a systematic comparative analysis of the scouring morphologies and the variations in pore-water pressure around the pipeline at different stages of scour development, it can be observed that the scouring process exhibits distinct characteristics. The evolution of each stage is intricately associated with the adjustment of internal stress within the soil mass and the mechanisms of water flow action. During the initial 10 min following the start of the scouring, the scouring action is most intense. This primarily manifests in the rapid expansion of the scouring hole and significant fluctuations in the pore-water pressure. Specifically, within the first 250 s, the pore-water pressure undergoes frequent changes, presenting an overall downward trend. This indicates that the water flow exerts a substantial shearing force on the soil surface, causing soil particles to detach rapidly and be transported away by the flowing water. Consequently, this leads to rapid release and redistribution of the pore-water pressure. At this stage, the longitudinal development rate of the scouring pit reaches its peak, demonstrating a pronounced vertical erosion effect. This implies that the energy of the water flow is predominantly concentrated in the area beneath the pipeline, strongly disturbing the soil structure and rising to the initial scouring pit. As shown in the figure, the variation in the average pore-water pressures, , reaches 12.5% of during the beginning stage of scour process. Once the elapsed time exceeds 250 s, the amplitude of pore-water pressure fluctuations gradually diminishes and stabilises around 0.08. This suggests that the internal stress adjustment within the soil mass approaches equilibrium; accordingly, the scouring rate decreases, marking the entry into a relatively stable scouring development phase.

At the same time, the scouring morphology transitions from the initial longitudinal deepening to lateral expansion, and the variation in the depth of the scouring pit becomes more gradual. After 10 min of scouring, the evolution of the scouring morphology is mainly characterised by an increase in the width of the scouring pit, with relatively minor changes in the longitudinal direction. This indicates that the scouring process has entered a stable stage. At this point, influenced by the geometric configuration of the scouring pit, the water flow forms recirculation or vortex structures within the pit, thus altering the local flow velocity distribution and the intensity of erosion. In conclusion, the early stage of scouring is a period of intense soil disturbance and a significant pore-water pressure response, as well as a time when the scouring hole rapidly takes shape. As the scouring process progresses, the system gradually stabilises, and the scouring morphology is mainly characterised by lateral expansion.

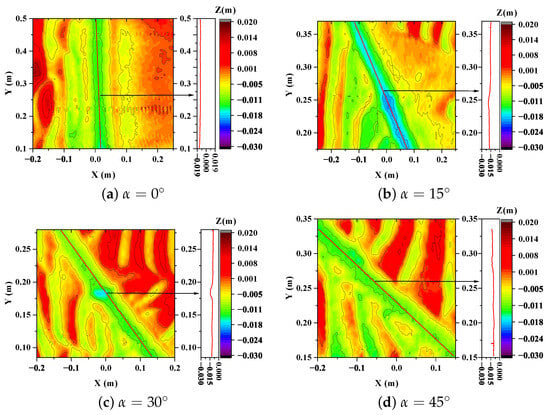

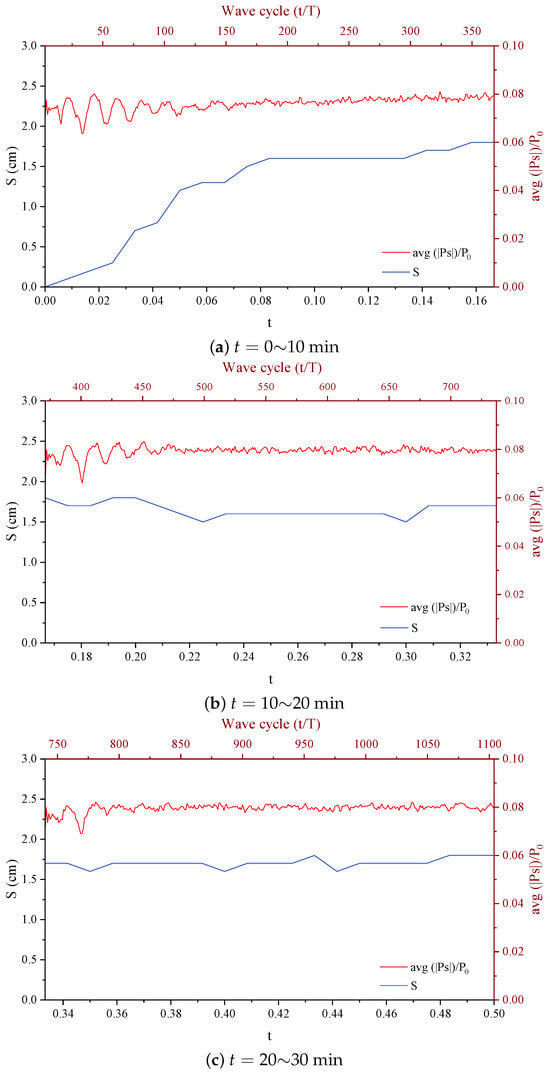

3.4. Variation of Pore-Water Pressure During Scour Process

By comparing the variation processes of the pore-water pressure amplitude () and the scour depth (S), it was found that the two exhibited significant dynamic correlation characteristics. In the tests, an analysis of the variations in these two parameters is performed every 10 min within the first 30 min before the onset of the scouring. The total scouring duration is 1 h, and stability is achieved after half an hour; thus, only the changes that occurred in the first half-hour are presented. During the initial 0–600 s phase, as illustrated in Figure 16a, the pore water pressure amplitude remains stably within the range of 0.02–0.09. High amplitudes () account for a relatively large proportion, with notable fluctuations and an overall upward trend. During the development of the scouring process, the scour depth experiences significant alterations, especially with the highest scouring rate in the first 250 s. After 250 s, the scouring rate decelerates. Although the scour depth continues to increase, the maximum scour depth remains less than 2.0 cm. This suggests that the pore-water pressure transmission within the soil mass tends to stabilise, and the external scouring action can simply induce the detachment of a minute quantity of surface particles. Collectively, these two aspects manifest an initial synergistic state with minimal dynamic changes.

Figure 16.

The time-history diagrams of pore-water pressure and scour depth during the 10 min scouring process under this wave–current condition ( m, s, m/s, ).

Entering the 600–1200-s phase (see Figure 16b), the fluctuation frequency of the pore-water pressure amplitude increases and the value range narrows to 0.01–0.08, with the peak value dropping by 0.01 compared to the previous phase. This alteration implies that the internal pore structure of the soil has undergone subtle adjustments due to previous scouring perturbations. The local pore water seepage pathways have been modified, leading to a transient instability in the transmission of the pore-water pressure. Consequently, the fluctuation amplitude of the scour depth increases significantly. This indicates that the unstable fluctuations in pore water pressure within the soil weaken the inter-particle bonding forces, rendering the external scouring more likely to trigger the detachment and transportation of surface particles. In other words, a phased erosion phenomenon occurs, and the dynamic change amplitudes of both parameters exhibit a synchronous enhancement of the synergistic effect.

In the 1200–1800-s phase (see Figure 16c), the fluctuations of the pore-water pressure amplitude further subside, stabilising within the range of 0.01–0.07. The proportion of high amplitudes decreases substantially, indicating that the internal pore structure of the soil has essentially completed its adjustment. The pore-water pressure field has re-established a stable equilibrium, and the effective stress between particles has recovered to a relatively stable level. Consequently, the fluctuation frequency of the scour depth decreases and the fluctuation amplitude contracts, eventually stabilising around 1.8 cm. This indicates that the stability of pore-water pressure within the soil provides favorable conditions for the restoration of inter-particle bonding forces. As a result, the anti-scouring capacity is enhanced and the scouring effect gradually diminishes. The dynamic changes of both the pore water pressure amplitude and the scour depth concurrently tend towards stability.

In summary, within the first h of the scouring process, both the pore-water pressure amplitude and the scour depth exhibit a pattern of “initial fluctuation–mid–term adjustment–late–stage stability”, and a certain degree of synergy exists between them. The reduction in pore water pressure amplitude coincides with the attenuation of the scour depth variation trend, indicating that the gradual stabilization of pore-water pressure within the soil facilitates the improvement of the surface anti-scouring capacity. This phenomenon also reflects that during the early stage of short-term scouring, the soil forms a stable state adaptable to the external scouring environment through the dynamic equilibrium between the adjustment of its internal pore structure and the surface erosion process. This dynamic coupling relationship not only unveils that the dominant control mechanism during the scouring process is transitioning from being governed by external fluid dynamics to being dictated by the mechanical responses of the soil, but also offers a quantifiable criterion for predicting the long-term evolution of scouring. Specifically, when both parameters enter a stable fluctuation range of and persist within this range for a certain duration, it can be concluded that the system has entered the macroscopic stable phase.

4. Conclusions

Based on wave flume experiments, this study systematically investigated the 3D scour process around pipelines under the combined action of waves and currents. Particular emphasis was placed on analysing the variations in pore-water pressure and hydrodynamic characteristics during the scour process. Through an in-depth analysis of the experimental data, the following conclusions can be drawn.

- (1)

- The scour response of the sandy seabed is rapid and exhibits short-term stability. The experimental data indicate that the scouring process in a sandy seabed around the pipelines progresses rapidly and the entire scouring process reaches a stable state in 30 min. The maximum scouring depth invariably appears directly below the pipeline and is insensitive to variations in the current direction, suggesting that the vortex structure and local shear stress at the bottom of the pipeline are the crucial dynamic mechanisms governing the development of scouring.

- (2)

- The scouring process manifests distinct stage-specific characteristics. In the initial stage (0–10 min), the destruction of the soil structure is most intense during this period. The pore-water pressure responds significantly and the vertical depth of the scour pit increases rapidly. It essentially reaches a stable state within the first 10 min, suggesting that the sandy seabed has relatively weak anti-scouring capabilities and is highly sensitive to the influence of water flow. In the later stage (10–30 min), the scouring morphology is predominantly characterised by lateral expansion. The variation in vertical scouring depth gradually becomes more gentle and the system gradually approaches a dynamic equilibrium state.

- (3)

- The dynamic variation in pore-water pressure is closely associated with the scouring progression. During the initial stage of scouring, the amplitude of pore-water pressure exhibits a non-monotonic trend of “decreasing first and then increasing”, which reflects the instantaneous disruption of the soil skeleton structure and the redistribution process of pore-water pressure. Approximately 250 s after the commencement of scouring, the amplitude of pore-water pressure stabilises, indicating that the soil–fluid interaction has attained a state of dynamic equilibrium. At this juncture, the rate of scouring development decreases significantly.

- (4)

- The evolutionary process of the scouring morphology is significantly affected by the dynamic variations of pore-water pressure. During the early stage of scouring, the intense fluctuations in pore-water pressure are closely associated with the instability of the soil mass. In the subsequent stage, once the pore-water pressure stabilises, the scour pit predominantly exhibits lateral expansion. This phenomenon suggests that the dynamic changes in pore-water pressure can serve as a crucial metric for determining the development stages of scouring. Specifically, during the initial stage of scouring (the first 10 min), pore-water pressure data can be effectively utilised to identify the acceleration phase of scouring, thereby holding significant early-warning implications.

In this study, a series of wave flume experiments for 3D scouring experiments under waves and currents has been systematically examined, with a specific focus on the relationship between pore-water pressure and scouring process. Since this study was performed in a wave flume, the 3D scour can only be considered in a small-scale condition with a specific sandy seabed. This study can provide some preliminary knowledge of the relationship between pore-water pressure and scouring process. However, it is necessary to further explore the impacts of different soil types and complex flow conditions, such as irregular waves, on the scouring process in the future.

Author Contributions

M.L.: Methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation; D.-S.J.: Conceptualization, methodology, resources, writing—original draft preparation, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition; Z.W.: investigation, data curation, writing—review; D.L.: data curation, writing—review; D.C.: data curation, writing—review; K.S.: Conceptualization, Methodology, supervision, writing—review; L.C.: Conceptualization, Methodology, writing—review; Z.L.: Conceptualization, Methodology, supervision, writing—review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study and the APC were funded by Shandong Provincial Overseas High-Level Talent Workstation (A2021-140).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be available upon the request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for invaluable comments of four reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Damgarrd, J.S.; Sumer, B.M.; Teh, T.C.; Palmer, A.; Foray, P.; Osorio, D. Guidelines for pipeline on-bottom stability on liquefied noncohesive seabeds. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean Eng. 2006, 132, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drumond, G.P.; Pasqualino, I.P.; Pinheiro, B.C.; Estefen, S.F. Pipelines, risers and umbilicals failures: A literature review. Ocean Eng. 2018, 148, 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Waqar, M.; Yan, H.; Louati, M.; Ghidaoui, M.S.; Lee, P.J.; Meniconi, S.; Brunone, B.; Karney, B. Pipeline leak localizationusing matched-field processing incorporating prior information of modeling error. Mechincal Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 143, 106849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meniconi, S.; Capponi, C.; Frisinghelli, M.; Brunone, B. Leak detection in a real transmission main through transient tests: Deedsand misdeeds. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2020WR027838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meniconi, S.; Brunone, B.; Tirello, L.; Rubin, A.; Cifrodelli, M.; Capponi, C. Transient tests for checking the trieste subsea pipeline: Toward field tests. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meniconi, S.; Brunone, B.; Tirello, L.; Rubin, A.; Cifrodelli, M.; Capponi, C. Transient tests for checking the trieste subsea pipeline: Diving into fault detection. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaechi, C.V.; Hosie, G.; Reda, A. Review on subsea pipeline integrity management: An operator’s perspective. Energies 2022, 16, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumer, B.M.; Fredsøe, J. The Mechanics of Scour in the Marine Environment; World Scientific: Hackensack, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredsøe, J. Pipeline-seabed interaction. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean Eng. 2016, 142, 03116002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiew, Y.M. Mechanics of local scour around submarine pipelines. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1990, 116, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumer, B.M.; Fredsøe, J. Scour below pipelines in waves. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean Eng. 1990, 116, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredsoe, J.; Sumer, B.M.; Arnskov, M.M. Time scale for wave/current scour below pipelines. In Proceedings of the First International Offshore and Polar Engineering Conference, Edinburgh, UK, 11–16 August 1992; pp. 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sumer, B.M.; Truelsen, C.; Sichmann, T.; Fredsøe, J. Onset of scour below pipelines and self-burial. Coast. Eng. 2001, 42, 313–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamoon, A.A.; Zhao, M.; Wu, H.; Keshavarzi, A.; Hu, P.; An, H. Local scour round a pipeline sleepr system under different flow directions. Coast. Eng. 2023, 183, 104335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beek, F.A.; Wind, H.G. Numerical modelling of erosion and sedimentation around offshore pipelines. Coast. Eng. 1990, 14, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.F.; Cheng, L. Numerical model for wave-induced scour below a submarine pipeline. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean Eng. 2005, 131, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, G. Seabed scour beneath an unburied pipeline under regular waves. Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. 2019, 37, 1247–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Yeow, K.; Zang, Z.; Li, F. 3D scour below pipelines under waves and combined waves and currents. Coast. Eng. 2014, 83, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frame, M.; Cheng, L. Three dimensional scour below offshore pipelines. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Asian and Pacific Coasts (APAC 2003), Singapore, 28 February–4 March 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Yeow, K.; Zhang, Z.; Teng, B. Three-dimensional scour below offshore pipelines in steady currents. Coast. Eng. 2009, 56, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chiew, Y.M. Three-dimensional scour at submarine pipelines. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2012, 138, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tian, Y.; Esteban, M.D. Experimental study on local scour and onset of VIV of a pipeline on a silty seabed under steady currents. Appl. Ocean Res. 2021, 109, 102560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xie, L.; Wong, T.; Su, T. Development of Three-Dimensional Scour below Pipelines in Regular Waves. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, T.; Staunstrup, L.H.; Carstensen, S.; Fuhrman, D.R. Span shoulder migration in three-dimensional current-induced scour beneath submerged pipelines. Coast. Eng. 2021, 164, 103776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, T.T.; Yang, Q.; Staunstrup, L.H.; Carstensen, S.; Huang, J.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, J.; Fuhrman, D.R. Wave-plus-current induced span shoulder migration in three dimensional scour around submarine pipeline. Coast. Eng. 2024, 194, 104622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumer, B.M. Liquefaction Around Marine Structures; World Scientific: Hackensack, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, T.C.; Palmer, A.C.; Damgaard, J.S. Experimental study of marine pipelines on unstable and liquefied seabed. Coast. Eng. 2003, 50, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.Y.; Liu, X.L.; Jeng, D.S.; Zheng, J.H.; Zhang, J.S.; Liang, Z.D. Numerical investigation into the vulnerability to liquefaction of an embedded pipeline exposed to ocean storms. Coast. Eng. 2022, 172, 104056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Guo, Z.; Wang, L.; Dou, Y.; Liu, Z. Experimental study on wave-induced seabed response and force on the pipeline shallowly buried in a submerged sandy slope. Ocean Eng. 2022, 251, 111153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Lin, J.; Zhang, J.S.; Guo, Y. Numerical modeling of combined wave and current-induced residual liquefaction around twin pipelines. Ocean Eng. 2022, 261, 112134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Cui, L.; Jeng, D.S.; Wang, M.Q.; Sun, K.; Chen, B. Hydrodynamic characteristics around offshore pipelines and oscillatory pore-water pressures in sand beds under combined random wave and current loading. Theor. Appl. Mech. Lett. 2025, 13, 100575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, J.; Tong, L.; Sun, K.; Guo, Y.; Wei, C. Experimental study of soil responses around a pipeline in a sandy seabed under wave-current load. Appl. Ocean Res. 2023, 103, 103409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Y.; Jeng, D.S.; Guo, Y.; Liang, Z. Laboratory experimental study of ocean waves propagating over a partially buried pipeline in a trench layer. Ocean Eng. 2019, 173, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Jeng, D.S.; Zhao, H.; Guo, W.; Wang, L. Effect of seepage flow on sediment incipient motion around a free spanning pipeline. Coast. Eng. 2019, 143, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Qi, W.G.; Li, Y.P. The role of dynamic seepage response in sediment transport and tsunami-induced scour. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2025, 130, e2024JC021084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, H.L.; Jeng, D.S. Integrated wave-seabed-scour model for local scour around a pipeline: PORO–FSSI–SCOUR–FOAM. Coast. Eng. 2024, 187, 104424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, J.S.; Chen, N.; Jeng, D.S.; Zhao, S.; Li, X. Experimental study of bimodal spectrum wave-induced dynamic responses in a silty seabed. Coast. Eng. 2025, 204, 104890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Lin, F.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, M.; Liu, X.; Han, S.; Jeng, D.S. Effect of clay content on the coupled seabed response and local scour around a free-spanning pipeline under combined waves and currents. Coast. Eng. 2025, 204, 104910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goda, Y.; Suzuki, Y. Estimation of incident and reflected waves in random wave experiments. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Coastal Engineering (ICCE1976), Honolulu, HI, USA, 11–17 July 1976; pp. 828–845. [Google Scholar]

- Mansard, E.P.D.; Funke, E.R. The measurement of incident and reflected specra using a least square method. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Coastal Engineering (ICCE1980), Sydney, Australia, 23–28 March 1980; pp. 154–172. [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson, M. Measurement of regular wave reflection. J. Waterw. Harb. Coast. Eng. Div. 1991, 117, 533–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nallayarasu, S.; Fatt, C.H.; Shankar, N.J. Estimation of incident and reflected waves in regular wave experiments. Ocean Eng. 1995, 22, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassa, S.; Sekiguchi, H. Wave-induced liquefaction of beds of sand in a centrifuge. Géotechnique 1999, 49, 621–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, R.; Dalrymple, R.A. Water Wave Mechanics for Engineers and Scientists; World Scientific: Hackensack, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Soulsby, R.L.; Whitehouse, R.J.S. Threshold of sediment motion in coastal environments. In Proceedings of the Pacific Coasts and Ports’97. Proceedings, Christchurch, New Zealand, 1 January 1997; Volume 1, pp. 149–154. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Li, G.; Dong, P.; Shi, J.; Xu, J. An experimental study of seabed responses around a marine pipeline under wave and current conditions. Ocean Eng. 2011, 38, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keulegan, G.H.; Carpenter, L.H. Forces on cylinders and plates in an oscillating fluid. J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand. 1958, 60, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumer, B.M.; Fredsøe, J. Hydrodynamics Around Cylindrical Structures; World Scientific: Hackensack, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, A. Application of Similitude Mechanics and Research on Turbulence to Bed Load Movement; Technical Report 26; Mitteilungender Preussischer Versuchsanstalt fur Wasserbau und Schiffbau: Berlin, Germany, 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Chien, N.; Wan, Z. Mechanics of Sediment Transport; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulsby, R. Dynamics of Marine Sands; Thomas Telford: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, H.; Jeng, D.S.; Z, G.; Liang, Z.D. Impact of two-dimensional seepage flow on sediment incipient motion under waves. Appl. Ocean Res. 2021, 108, 102510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, G.; Dong, P.; Shi, J. Bedform evolution around a submarine pipeline and its effects on wave-induced forces under regular waves. Ocean Eng. 2010, 37, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).