Abstract

Despite the increasing number of foreign seafarers working in the Korean shipping industry and the growing concern for psycho-emotional stress due to discrimination in the maritime sector, few studies have focused on the working environment of foreign seafarers on South Korean vessels. This study aimed to determine whether foreign seafarers perceived discrimination in the Korean shipping industry and if so, the types of discrimination they faced and how they responded to this challenge. A survey was conducted to assess foreign seafarers’ experiences of discrimination, understanding of their own human rights, and level of satisfaction in working with Korean seafarers as well as identifying positive factors. The main positive findings included the kindness of colleagues, and excellent welfare facilities and benefits; whilst the most frequently reported negative factors related to language barriers and food types. These findings can be used to identify and share best practices and help determine priority areas for action. However, as the number of participants was small due to difficulties in contacting foreign seafarers during COVID-19 restrictions, further research is necessary to understand and improve the working environment of foreign seafarers on South Korean vessels.

1. Introduction

The shipping industry performs an important role in South Korea’s trade. A recent statistical report showed that more than 90% of export–import goods in South Korea are handled through seaports [1]. Notwithstanding the importance of this industry, there has been a constant decline in the number of Korean seafarers, from 38,906 in 2012 to 33,565 in 2020 [2], due to negative perceptions of working at sea (e.g., working at sea is dirty, difficult, dangerous, and lonely) [3,4]. In response, the South Korean government has permitted foreign seafarers to work on Korean vessels, and consequently, multicultural crew vessels have become increasingly common in South Korea in the last 10 years.

As of 2018, there were 26,321 foreign seafarers in South Korea, accounting for approximately 43% of the total 61,072 seafarer population [5]; by 2020, this number increased to 26,775 [2]. In terms of nationality, South Korea reported 10,669 (40.0%) of its foreign seafarers as being from Indonesia, 5464 (20.4%) from the Philippines, 5025 (18.8%) from Vietnam, 4376 (16.3%) from Myanmar, and 1211 (4.5%) from other countries in 2020. It is worth noting that seafarers’ wages differ by country [6], and Korean seafarers’ wages are generally higher compared with seafarers from other Asian countries such as Indonesia, Vietnam, and Myanmar [7]. The number of foreign seafarers continues to increase with shipping companies’ efforts to enhance market competitiveness by reducing the labour cost of the crew [8].

According to Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights [9]”. However, the exclusion or discrimination of minorities occurs in various areas, and has emerged as a major social problem in South Korea [10]. For example, foreign workers in South Korea face conflicts with employers or colleagues due to food preferences and requirements, religious activities, and wage issues [11]. Foreign workers have also been subjected to inadequate treatment, such as abusive language, from their Korean colleagues and employers [12]. In addition, an analysis of accidents on a multicultural crew vessel found that the safety rules onboard were written only in Korean, without considering foreign seafarers’ Korean language ability [13].

The shipping industry is associated with a high level of fatalities [14,15]. Individual workers have different levels of vulnerability to stress, which is related to various factors such as work conditions, responsibility, and psychosocial factors [16]. Occupational fatigue is also a serious issue in the maritime industry [17,18] and encompasses physical, mental, or emotional exertion [19]. It is a hazard that can impair alertness and the ability to manage safe operation of a ship [19,20]. Seafarers’ fatigue can impact their own health and safety as well as the safety of the vessel [21,22] and other seafarers. Furthermore, seafaring is associated with mental health risks [23,24]. While mental stress is a known risk factor for working at sea [24], various other factors such as loneliness, lack of shore leave, fatigue, and cultural problems also affect seafarers’ mental health [25]. Poor mental health can have fatal consequences for seafarers who face many challenges, such as restricted social contact and isolation from family and friends, especially given that they work and live in a confined environment [26]. Moreover, recent travel restrictions due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic have not only isolated seafarers physically and socially, but also alienated them from medical services, negatively affecting their ability to access mental health support [27].

Social isolation can lead to psychological problems, such as depression [22], and mental stress can significantly affect sleep [28], which is an important factor in psychological well-being [22]. In addition to these challenges, multi-nationality is an important stressor among seafarers on multicultural crew vessels [28], because each worker may have a different attitude toward crew members of differing nationalities [23]. The cultural distance among seafarers is a significant stressor that can affect social relationships among members onboard [29]. Foreign workers’ stress is often negatively correlated with social and religious activities; the less social activity, including gatherings with friends and religious group gatherings, the more stress they experience [30]. In this regard, studies have shown that cumulative exposure to racial or religious discrimination can negatively affect mental health [31], and that racial microaggressions can negatively impact individuals’ self-esteem and well-being [32].

Despite the increasing number of foreign seafarers in the Korean shipping industry and the growing concern about their psycho-emotional stress due to discrimination in the maritime sector, few studies have explored the prevalence of discrimination against foreign seafarers on South Korean vessels and identified any associated coping strategies or employer protection measures that have been initiated. Shipping companies must increasingly avoid financial performance-centric management methods and adopt sustainability-based environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance evaluation required by diverse stakeholders such as the state, society, shippers, and seafarers. To address this issue, the purpose of this study was to determine whether foreign seafarers experience discrimination in the Korean shipping industry and if so, to identify the types of discrimination and the methods used by foreign seafarers to deal with such challenges. We also focused on seafarers’ experiences of positive factors associated with working on multicultural vessels. The main findings are expected to help determine priority areas for addressing discriminatory behaviour and mitigating against such conduct as well as identifying areas of best practice which can be built upon in the industry. There are five sections including this introductory section. The second section provides the research methodology including survey questions and data processing. Section three presents findings across three categories: (1) experience of discrimination, (2) responses to discrimination, and (3) opinion on working with Korean seafarers. The final two sections discuss the key findings of the survey before concluding with recommendations to improve the working environment of foreign seafarers in the Korean merchant shipping industry.

2. Materials and Methods

This study used a descriptive cross-sectional survey design to collect data on discrimination experienced by foreign seafarers in the shipping industry. The study targeted foreign seafarers working on merchant vessels, such as bulk carriers, container ships, and liquefied natural gas (LNG) bunkering vessels of four shipping companies in South Korea. Restrictions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic limited the scope and scale of the research.

As the basis for statistical analysis, of the 114 foreign seafarers who were approached to participate in the survey, from November 2020 to April 2021, 94 agreed to participate; of these, 2 were excluded from the analysis due to the omission of answers to more than 30% of the questions. The characteristics of the survey participants are summarized in Table 1. All the participants were males of various nationalities, mainly Indonesian (36; 39.1%), Filipino (32; 34.8%), and Myanmarese (24; 36.1%). Regarding the working department, 56 (60.9%) were ratings including the deck crew, engine crew, and stewards, and 36 (39.1%) were officers including deck officers and engine officers. Participants’ experience of working with Korean seafarers varied from less than 3 years to more than 12 years. Their self-rated Korean language ability was mostly below the intermediate level (78; 84.8%). The fleet size of the surveyed companies varied from less than 10 to more than 51 vessels.

Table 1.

Characteristics of foreign seafarers working in South Korea (n = 92).

The study used a questionnaire to gather information about discrimination experienced by foreign seafarers working with Korean seafarers. The term ‘discrimination’ used in the survey was defined as a discriminatory act violating the equal right under Article 2 (definition) of the National Human Rights Commission Act in South Korea and was explained to the participants in the survey in advance. The discriminatory acts violating the equal right refer to “any of the following acts, without reasonable grounds, on the grounds of sex, religion, disability, age, social status, region of origin (referring to a place of birth, place of registration, principal area of residence before coming of age, etc.), state of origin, ethnic origin, physical condition such as features, marital status such as single, separated, divorced, widowed, remarried, married de facto, or pregnancy or childbirth, types or forms of family, race, skin colour, ideology or political opinion, record of crime whose effect of punishment has been extinguished, sexual orientation, academic career, medical history, etc.,: (a) An act of favourably treating, excluding, discriminating against or unfavourably treating a particular person regarding employment (including recruitment, appointment, education, posting, promotion, payment of wage and any other money or valuables, financing, age limit, retirement, dismissal, etc.); (b) An act of favourably treating, excluding, discriminating against or unfavourably treating a particular person regarding the supply or use of goods, services, means of transportation, commercial facilities, land and residential facilities; (c) An act of favourably treating, excluding, discriminating against or unfavourably treating a particular person regarding education and training at educational facilities or institutions for workplace skill development, or the use thereof; (d) An act of sexual harassment”.

A survey questionnaire was constructed to cover details of any type of discrimination experienced, workers’ understanding of their own human rights, and their level of satisfaction in working with Korean seafarers including positive aspects. The survey questions were based on the literature [11,12,13,31], and explored the following categories: problems according to individual characteristics; problems between individuals; and problems between individuals and organizations. Considering that the foreign seafarers land on shore intermittently for the handling of administrative affairs related to boarding a ship such as customs, immigration, quarantine, and onshore training, the question of whether foreign seafarers have experienced discrimination in public institutions or public places in South Korea was also asked. The list of questions asked in the survey is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

List of questions.

The survey was conducted both online and offline. In the case of seafarers who had an internet connection, Google’s online survey platform was used by sending the link to the participants’ email, and for those who could not connect to the internet, hard copy questionnaires were distributed and collected with the help of an officer who managed foreign seafarers at each participating company. Since visits were restricted due to the companies’ COVID-19 prevention policies, this necessitated questionnaire distribution via company staff.

The purpose and contents of the survey were explained in English to the foreign seafarers in advance. The participants were also informed that the data collected would be strictly managed in accordance with Article 33 (Protection of Secrets) of the Statistics Act in South Korea and would not be used other than for research purposes as stated on the questionnaire. The participants were asked to fill out the survey honestly and seal it in the envelope provided to prevent data manipulation. The survey was conducted voluntarily and anonymously in a private space, without any intervention by the company staff. Company staff only performed a role in distributing and collecting questionnaires, and the sealed state of the delivered questionnaire was confirmed by the lead researcher.

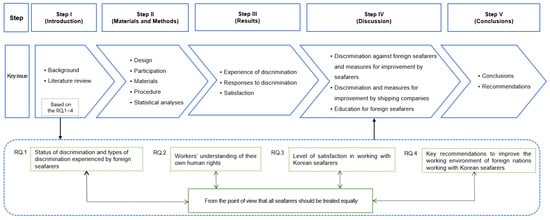

All analyses were run in IBM SPSS version 27. Descriptive statistics were used to understand the status of discrimination experienced by foreign seafarers working with Korean seafarers; the Mann–Whitney U test was used to identify whether there was a statistically significant difference in satisfaction between foreign officers and ratings; and Kendall’s W was calculated to discover if priorities are meaningful when selecting an area for improvement. The study design is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study Design and Process.

3. Results

3.1. Experience of Discrimination

Overall, 10 (10.9%) foreign seafarers reported that they experienced discrimination by Korean seafarers. More than half of the participants (49, 53.3%) agreed that Korean seafarers treated foreign seafarers equally, but 36 (39.1%) were neutral and 7 (7.6%) disagreed.

The participants were asked to report any acts of discrimination against foreign seafarers onboard that violated equal rights as presented in Article 2, No. 3 of the National Human Rights Commission Act [33]. The participants selected all applicable discriminatory acts among the options, with 166 responses in total. They reported discrimination related to academic career (n = 22; 13.3%), criminal record (n = 21; 12.7%), social status (n = 20; 12.0%), medical history (n = 19; 11.4%), sexual orientation (n = 18; 10.8%), race (n = 14; 8.4%), religion (n = 12; 7.2%), state of origin (n = 8; 4.8%), physical condition (n = 7; 4.2%), region of origin (n = 5; 3.0%), skin colour (n = 5; 3.0%), types or forms of family (n = 4; 2.4%), gender (n = 3; 1.8%), disability (n = 3; 1.8%), ideology or political opinion (n = 3; 1.8%), and ethnic origin (n = 2; 1.2%).

Table 3 presents the experiences of reported discrimination based on the nationality of the survey participants. No foreign seafarers have faced discrimination in government offices, public institutions, or banks in South Korea. However, foreign seafarers experienced discrimination onboard. The majority of the participants reported discrimination related to wages, including low wages for the same work as Korean seafarers and no payment for overtime work, followed by verbal insults, such as being emotionally abused for eating habits and being insulted with regard to their country of origin.

Table 3.

Forms of discrimination experienced by foreign seafarers by nationality.

3.2. Responses to Discrimination

Of the 92 participants, 74 (80.4%) answered that they were aware of the Korean law on the rights of seafarers. They selected the following options as sources of awareness of the law: “I was trained before boarding a Korean vessel” (n = 65; 70.7%), “I heard about it from my countrymen who worked here” (n = 4; 4.3%), “I got this information during on-the-job training” (n = 3; 3.3%), “I got information from public organizations in Korea” (n = 2; 2.2%), and others (e.g., searching the internet and obtaining information from inspectors visiting the vessel) (n = 5; 5.4%). However, although many of them were aware of the laws concerning seafarers’ rights, only 36 (39.1%) foreign seafarers had heard of the National Human Rights Commission Act.

Table 4 depicts the various responses of foreign seafarers to human rights violations or acts of discrimination. Human rights refer to any human dignity and worth, liberty, and rights that are guaranteed in South Korea as defined in Article 2, No. 1 of the National Human Rights Commission Act. When faced with human rights violation or discrimination, most participants chose to handle the situation indirectly, as reflected by their most common responses to “seek help from the captain or the chief engineer of the vessel” and “consult a crew agent.” Only 18 participants (15.5%) complained directly to the discriminator.

Table 4.

Foreign seafarers’ responses to human rights violations or discrimination (multiple choice; n = 116).

3.3. Opinion on Working with Korean Seafarers

A questionnaire focused on satisfaction with working onboard with Korean seafarers. We used the following categories on a Likert scale: very satisfied, satisfied, neutral, dissatisfied, and very dissatisfied. In terms of satisfaction in working with Korean seafarers, 21 (22.8%) foreign seafarers were very satisfied, 47 (51.1%) were satisfied, 23 (25%) were neutral, and 1 (1.1%) was dissatisfied. The Mann–Whitney U test showed that there was no statistically significant difference in satisfaction with working with Korean seafarers between foreign officers and ratings (U = 881.0, p = 0.267).

Table 5 shows the details of the positive and negative factors related to working with Korean seafarers at Korean shipping companies. The positive factors reported by foreign seafarers were as follows: excellent welfare facilities and benefits (48; 32.4%), kindness of company colleagues (28; 18.9%), and high wages (20; 13.5%). The negative factors were as follows: language barrier (49; 42.2%), food (21; 18.1%), and wage discrimination (13; 11.2%).

Table 5.

Positive and negative factors related to working with Korean seafarers (multiple choices).

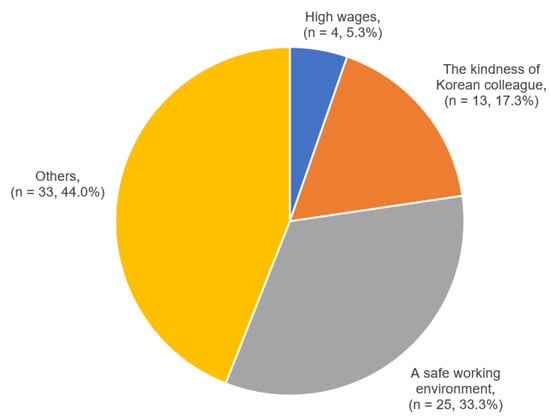

When asked about their intention to recommend working for a Korean shipping company to their friends, 75 (81.5%) responded “yes,” 5 (5.4%) said “no,” and 12 (13.0%) “did not know.” The reasons for willingness to recommend were in Figure 2: a safe working environment (25; 33.3%), kindness of Korean colleagues (13; 17.3%), high wages (4; 5.3%), and others (e.g., a similar culture to the country of origin and the observation that Korean shipping companies are not bad in general) (33; 44.0%). Three out of five respondents who said “no” revealed their reasons; two of them mentioned “unkindness of a Korean colleague,” and one reported “inadequate treatment on a vessel.”

Figure 2.

Chart depicting the reasons for willingness to recommend working for a Korean shipping company to their friends (n = 75).

Table 6 shows the opinions of foreign seafarers on priority areas for addressing discrimination. Priority was in the order of wage discrimination (1.87), abusive language (2.61), disregard for other cultures (3.05), disregard for other religions (3.43), and racial discrimination (4.03). Kendall’s W was calculated to be 0.269, with p < 0.001, indicating that priority was meaningful when selecting an area for improvement.

Table 6.

Priority areas for addressing discrimination (n = 92).

4. Discussion

Foreign seafarers comprise a large proportion of the workforce and perform an important role in the Korean shipping industry; therefore, it is necessary to identify and eliminate all negative factors in their working environment and to safeguard their physical and mental health. Through a survey analysis, this study investigated whether foreign seafarers experience discrimination onboard an explored the forms of discrimination they faced and their response to such discrimination. The key findings are discussed below, with recommendations to improve the working environment of foreign nationals working with Korean seafarers.

4.1. Discrimination against Foreign Seafarers and Actions for Korean Seafarers

While 10% of all the respondents felt they experienced discrimination by Korean seafarers, more than 45% disagreed or were neutral when asked whether Korean seafarers treat foreign seafarers equally, suggesting that it is necessary to examine and address some Korean seafarers’ attitudes toward their foreign colleagues. The survey revealed that several foreign seafarers faced discrimination with regard to their language, eating habits, country of origin, and religious activities. Discrimination regarding religious activities was found to occur particularly frequently among Indonesian seafarers; it may be relevant that more than 80% of Indonesian citizens are Muslims [34]. However, since the religious composition of the study sample cannot be confirmed, it cannot be concluded that differences between commonly practiced religions in Indonesia and South Korea impacted seafarers’ experience. However, we found that perceived discrimination takes place across several factors including religion, language, eating habits, and country of origin is in line with the fact that foreign seafarers were forced to adapt to Korean culture without considering that problems caused by cultural differences can be solved by mutual understanding [12]. People who experience racial discrimination are likely to suffer from depression and anxiety [35]. In addition, conflicts among seafarers on a mixed nationality crew vessel have been found to negatively affect a ship’s safety culture [3]. Therefore, it is necessary to prevent discrimination against others by providing educational opportunities for seafarers to understand cultural differences and ensuring effective investigation and sanctions for acts of discrimination, if and when they occur.

4.2. Discrimination against Foreign Seafarers and Actions for Shipping Companies

Ensuring all workers effectively enjoy basic rights to fair and just working conditions is important. According to the FRA [36], migrant workers are vulnerable to exploitation, especially people from developing countries, who are not in a position to leave their jobs whenever they want. This is because they may have few or no alternative options, and dependants or debts in their home countries.

In the 1990s, South Korea began recruiting foreign seafarers to strengthen the competitiveness of its shipping companies in the international market by easing the burden of labour costs [8]. Because companies pursue profits, there is a limit to restricting the use of relatively low-wage labour. However, foreign workers, such as Korean seafarers, should be paid on a fixed date and should not be forced to work on holidays without prior notification and consent. Foreign seafarers are also subject to the Korean Seafarers Act and the Labour Standards Act and should be protected by the law.

In this study, the most frequent form of discrimination was related to wages, which is associated with companies’ internal systems. Of the 92 participants, 31 (33.7%) were not paid overtime allowances, 11 (12.0%) were paid late, and 11 (12.0%) were forced to work overtime or work on holidays. The minimum wage for seafarers is fixed by the Korean government in accordance with Article 59 of the Seafarers Act. However, in the case of foreign seafarers the minimum wage can be determined by a collective agreement between the relevant seafarer labour organization and the owner of the ship [37,38]. Since the details of the seafarers’ employment contracts are not known, it cannot be stated whether overtime allowance should be granted or not, but late payment or forcing people to work overtime or on holidays should be addressed. Therefore, although it is important for shipping companies to voluntarily make efforts to comply with the relevant regulations, it is necessary to continuously monitor their compliance with regulations at the government level and to ensure that they take appropriate action when a breach is noted.

4.3. Education for Foreign Seafarers

While many foreign seafarers in this study were trained and well-informed about the Korean regulations on the rights of seafarers, less than half of them were aware of the National Human Rights Commission Act. This highlights the necessity of reviewing the contents of foreign seafarers’ training; through curriculum reorganization, foreign seafarers should be able to understand the relevant regulations related to their rights [39]. Moreover, workplace discrimination negatively affects outcomes such as attitudes toward the job and personal health [40]. Properly designed educational programs effectively ensure group safety by enhancing employees’ knowledge and motivation for change [41]. Therefore, taking appropriate measures against workplace discrimination and reducing foreign seafarers’ stress by educating them on how to respond to discrimination can help ensure the safety of the ship and crew.

Furthermore, 42.2% of the respondents mentioned the language barrier as a negative factor in working with Korean seafarers. The level of Korean language ability among foreign seafarers was reported as mostly 3 or less, on a scale of 1 to 5. The main communication method in the operation of the ship is speech, and effective communication is an essential element for safe ship operation [42]. In order for effective communication to occur, the message must be fully received and understood by the recipient, and when this does not happen, there is a possibility of miscommunication occurring [43] with serious implications for safety onboard. Language barriers can lead to misunderstanding, confrontation, and conflict, and behaviour performed in good faith can be interpreted negatively [12]. In order for foreign seafarers to board Korean ships, they must receive Korean language education in accordance with the Guidelines of Foreign Seafarers Management [44]. Since compulsory education for foreign seafarers under the current regulations has a very limited duration and there are no systematically developed educational materials [45], it is necessary to develop training contents that reflect the working circumstances of foreign seafarers and extend the training period so that Korean language education for foreign seafarers can be completed. This will help prevent grave errors that may compromise safety onboard in preparing for the expansion of state-of-the-art and high-risk vessels such as LNG-powered ships, LNG bunkering-only ships, and ammonia/hydrogen-powered ships.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated discrimination against foreign seafarers working in the Korean merchant shipping industry. The study findings reveal seafarers’ understanding of their rights and level of satisfaction in multicultural crews. These findings indicate the need for adopting appropriate actions and measures by shipping companies to protect seafarers from stress and fatigue and demonstrate increased concern for their welfare and safety.

Based on the findings, the major recommendations to prevent discrimination against foreign seafarers are as follows:

- ➀

- Provide educational opportunities for seafarers to understand and respect cultural differences;

- ➁

- Continuously monitor shipping companies’ compliance with employment-related laws, and take action when breaches are identified;

- ➂

- Develop a systematic educational curriculum and extend the training period so that Korean language education for foreign seafarers can be properly conducted.

Whilst the findings and recommendations are relevant to the current industry, the strengthening of environmental regulations in the global shipping industry, such as the International Maritime Organization’s greenhouse gas reduction strategy, the zero emission strategy of major shippers, and the demand for autonomous ships, has resulted in a paradigm shift in the shipbuilding and shipping industry [46,47] where high-tech, high-spec, eco-friendly ships, such as ESG-based LNG-powered ships, LNG bunkering-only ships, and ammonia/hydrogen-powered ships will become the norm. To ensure the safety of the fleet and those working in it, a mid- to long-term seafarer policy needs to be urgently established by prioritizing the education, training, welfare, and human rights protection of domestic and foreign seafarers to ensure the safety and well-being of all those working in these high-risk environments. Investment in the workforce must be considered alongside and with the same commitment as investment in the physical fleet.

These study findings helped in identifying the forms of discrimination against foreign seafarers working in Korea and outlined the necessary measures to prevent discrimination. This study has some limitations. Despite being able to understand many aspects of the types of discrimination that is currently experienced by respondents, the findings do not represent the full range of discrimination potentially experienced by foreign seafarers working with Korean seafarers. The extent of discrimination identified in this study should not be generalized to all foreign seafarers working in South Korea, as the number of participants was small because of limited means of contact with foreign seafarers during the pandemic. Future studies should specify strategies and policies to enhance the working conditions of foreign seafarers by identifying the difficulties and areas of improvement through a focus on sustainable maritime culture and its perception to achieve a thriving maritime business environment. Theoretical implications of empirical research revealing discrimination should also be explored.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and S.D.; methodology, J.L., S.D. and C.L.; software, J.L. and I.P.; validation, S.D. and C.L.; formal analysis, J.L.; investigation, J.L., K.K. and C.L.; resources, J.L. and S.D.; data curation, J.L. and I.P.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, S.D., I.P., M.J. and C.L.; visualization, J.L. and K.K.; supervision, C.L.; project administration, C.L. and D.J.; funding acquisition, M.J. and D.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea, grant number: NRF-2018S1A6A3A01081098; and the National R&D Project, “Development of LNG Bunkering Operation Technologies based on Operation System and Risk Assessment,” funded by the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, South Korea, grant number PMS4310.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines for securing research ethics and Article 33 (Protection of Secrets) of the Statistics Act in South Korea.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained in writing from all participants involved. Data collection was strictly managed in accordance with Article 33 (Protection of Secrets) of the Statistics Act in South Korea.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

References

- Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries. The Volume of Cargo Transported through Ports. Available online: http://www.index.go.kr/potal/main/EachDtlPageDetail.do?idx_cd=1265 (accessed on 31 January 2021).

- Korea Seafarers’ Welfare & Employment Center. Korean Seafarers Statistical Year Book. Available online: http://www.koswec.or.kr/ (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Kim, Y.U.; Park, M.K. A study on devices of reducing foreign fishermen’s rate of deserting from coastal and offshore fishing vessels in Korea. Sci. Educ. 2012, 24, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H. A study on the conflict resolution through human resource management in mixed-nationality crew vessels—Focusing on the ocean-going vessel. Marit. Law Rev. 2019, 31, 23–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries. A Press Release from the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries. Seafarers Statistical Yearbook. 2019. Available online: http://www.mof.go.kr/article/view.do?menuKey=971&boardKey=10&articleKey=26336 (accessed on 31 October 2021).

- Marinov, E.; Maglić, L.; Bukša, J. Market competitiveness of Croatian seafarers. Pomorstvo 2015, 29, 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, Y.W.; Sin, Y.J.; Kim, T.G.; Hong, S.H.; Lee, C.H.; Joe, S.Y.; Bae, H.S.; Kim, G.S.; Ju, D.I. A Study on the Necessity and Plan of Fostering Next-Generation Maritime Professionals; Korea Marine Officers’ Association: Busan, Korea, 2020; pp. iv–ix. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, Y.; Hong, S.; Lee, C. A study on the improvement of employment system for ocean-going seafarers. Marit. Law Rev. 2019, 31, 35–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/ (accessed on 15 November 2019).

- Eun, J.Y.; Mo, K.H. The state of multicultural human rights education that appeared in Korean social studies textbooks. J. Educ. Cult. 2018, 24, 7–31. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, Y.H.; Ha, J.C. A case study on the cultural conflict in the workplace of foreign workers from Southeast Asia. J Cult. Exch. 2019, 8, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J. Cultural conflicts and responses of migrant workers—with the case of Indonesian workers. J. Korean Cult. Stud. 2008, 38, 153–184. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, D.Y. A study on the marine accidents’ prevention of Korean fishing vessel which foreign seafarers are on board. J. Korean Soc. Mar. Environ. Saf. S. Afr. 2015, 21, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, D.; Panayides, P.M. Causes of casualties and the regulation of occupational health and safety in the shipping industry. WMU J. Marit. Aff. 2005, 4, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.E.; Nielsen, D.; Kotłowski, A.; Jaremin, B. Fatal accidents and injuries among merchant seafarers worldwide. Occup. Med. 2014, 64, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jezewska, M.; Leszczyńska, I.; Jaremin, B. Work-related stress at sea self-estimation by maritime students and officers. Int. Marit. Health 2006, 57, 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S.E. Occupational mortality in British commercial fishing, 1976–1995. Occup. Environ. Med. 2004, 61, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth, E.J.K.; Allen, P.H.; Wellens, B.T.; McNamara, R.L.; Smith, A.P. Patterns of fatigue among seafarers during a tour of duty. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2006, 49, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Maritime Organization Guidelines on Fatigue; IMO Publishing: London, UK, 2019.

- Akhtar, M.J.; Utne, I.B. Human fatigue’s effect on the risk of maritime groundings—A Bayesian network modeling approach. Saf. Sci. 2014, 62, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadsworth, E.J.K.; Allen, P.H.; McNamara, R.L.; Smith, A.P. Fatigue and health in a seafaring population. Occup. Med. 2008, 58, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hystad, S.W.; Nielsen, M.B.; Eid, J. The impact of sleep quality, fatigue and safety climate on the perceptions of accident risk among seafarers. Rev. Eur. Psychol. Appl. 2017, 67, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carotenuto, A.; Molino, I.; Fasanaro, A.M.; Amenta, F. Psychological stress in seafarers: A review. Int. Marit. Health 2012, 63, 188–194. [Google Scholar]

- Oldenburg, M.; Jensen, H.J.; Latza, U.; Baur, X. Seafaring stressors aboard merchant and passenger ships. Int. J. Public Health 2009, 54, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, R.T.B. The mental health of seafarers. Int. Marit. Health 2012, 63, 78–89. [Google Scholar]

- Hystad, S.W.; Eid, J. Sleep and fatigue among seafarers: The role of environmental stressors, duration at sea and psychological capital. Saf. Health Work 2016, 7, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, D.; Jego, C.; Jensen, O.C.; Loddé, B.; Pougnet, R.; Dewitte, J.D.; Sauvage, T.; Jegaden, D. Seafarers’ mental health in the COVID-19 era: Lost at sea? Int. Marit. Health 2021, 72, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jepsen, J.R.; Zhao, Z.; van Leeuwen, W.M.A. Seafarer fatigue: A review of risk factors, consequences for seafarers’ health and safety and options for mitigation. Int. Marit. Health 2015, 66, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellbye, A.; Carter, T. Seafarers’ depression and suicide. Int. Marit. Health 2017, 68, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ban, M.; Kim, M.S.; Lee, J. Stress of foreign workers in Korea. Korean J. Int. Migr. 2012, 3, 37–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, S.; Nazroo, J.; Bécares, L. Cumulative effect of racial discrimination on the mental health of ethnic minorities in the United Kingdom. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 1294–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cokley, K.; Smith, L.; Bernard, D.; Hurst, A.; Jackson, S.; Stone, S.; Awosogba, O.; Saucer, C.; Bailey, M.; Roberts, D. Impostor feelings as a moderator and mediator of the relationship between perceived discrimination and mental health among racial/ethnic minority college students. J. Couns. Psychol. 2017, 64, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korean Law Information Center; National Human Rights Commission. Act. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/ (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Embassy of the Republic of Indonesia. Facts & Figures. Available online: https://www.embassyofindonesia.org/ (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Lee, D.L.; Ahn, S. Racial discrimination and Asian mental health: A meta-analysis. Couns. Psychol. 2011, 39, 463–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Protecting Migrant Workers from Exploitation-FRA Opinions. Available online: https://fra.europa.eu/en/content/protecting-migrant-workers-exploitation-fra-opinions/ (accessed on 3 April 2022).

- Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries. Seafarers Minimum Wage Notice. Available online: https://www.mof.go.kr/iframe/article/view.do?articleKey=36563&boardKey=35&menuKey=402¤tPageNo=1 (accessed on 31 October 2021).

- Kim, Y.U. A comparative study on the foreign worker’s employment system of fishing vessels in Korea and Japan. Sci. Educ. 2012, 24, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lee, J.; Dhesi, S.; Phillips, I.; Jeong, M.; Lee, C. Korean maritime cadets’ onboard training environment survey. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanani, L.Y.; Beus, J.M.; Joseph, D.L. Workplace discrimination: A meta-analytic extension, critique, and future research agenda. Pers. Psychol. 2018, 71, 147–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navidian, A.; Rostami, Z.; Rozbehani, N. Effect of motivational group interviewing-based safety education on workers’ safety behaviors in glass manufacturing. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Winbow, A. The importance of effective communication. In Proceedings of the International Seminar on Maritime English, Istanbul, Turkey, 20–22 March 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmmed, R. The difficulties of maritime communication and the roles of English teachers. Bangladesh. Marit. J. 2017, 1, 22–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries. Guidelines of Foreign Seafarers Management; Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries: Sejong City, Korea, 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Park, K.E.; Park, J.S.; Ha, W.J. A study on the development of occupational purpose Korean language curriculum for foreign deck crews. J. Navig. Port Res. 2018, 42, 253–266. [Google Scholar]

- Belev, B.C.; Daskalov, S.I. Computer technologies in shipping and a new tendency in ship’s officers’ education and training. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 618, 012034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; D’agostini, E.; Kang, J. From seafarers to E-farers: Maritime cadets’ perceptions towards seafaring jobs in the industry 4.0. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).