Abstract

To investigate the spatiotemporal dynamics and wall shear stress patterns of a PVC (precessing vortex core) within a bounded swirling flow for agricultural irrigation, LES (Large Eddy Simulation) simulations based on a guide-vane hydro-cyclone were conducted and validated by physical experiments. Coherent structures were extracted through flow modal decomposition, and a reduced-order model was established. The modal analysis of the flow reveals the following: A modal pairing phenomenon exists in the swirling flow, starting from the swirling section downstream of the guide-vane. The flow converts from a basic pipe flow to swirling flow. Compared to the vane section, the composite PVC in the swirling section exhibits mutual momentum exchange, leading to increasingly fragmented evolution of the vortex core over time and space. The application of vortex identification criteria to the reconstructed reduced-order model reveal that the precessing vortex core exhibits a tendency to spiral downstream along the guide-vane twist direction, with its rotation direction perfectly aligned with the guide-vane twist. As the Reynolds number of the bounded swirling flow increases, the circumferential precession of the PVC exhibits a linear weakening trend. As the relative length l/d of the guide-vane to the pipe increases, the circumferential precession of the PVC shows a linear strengthening trend. The wall shear stress analysis results indicate that the stress coefficient magnitude near the downstream location of the guide-vane is approximately zero, representing the lowest value across the entire flow. The region exhibits a rotational precession trend downstream. The stress coefficient magnitude between guide-vanes is relatively high, about 0.1 times dynamic pressure of approaching flow, and this trend also develops downstream with a rotational precession tendency.

1. Introduction

Siltation and blockage in agricultural irrigation pipelines are the primary factors limiting irrigation efficiency and increasing irrigation costs [1,2]. These issues may stem from the deposition of sand and gravel from irrigation water within the pipelines [3,4] or from the crystallization and subsequent blockage caused by water–fertilizer integrated irrigation systems [5,6]. Severely silted irrigation pipelines often become unusable for normal irrigation, necessitating extensive replacement of affected sections. This practice, however, contradicts sustainable agricultural development goals. The flow mechanism behind sedimentation blockage in conventional irrigation pipes involves gravel accumulating downward within the pipe flow field due to gravity. Alternatively, fertilizer concentration gradients formed under gravity cause uneven distribution across the cross-section, facilitating crystal precipitation on pipe walls where concentrations are relatively higher. A feasible and sustainable solution involves installing vane swirl devices at critical points within irrigation pipelines [7]. These devices generate secondary flow along the circumferential and radial directions, creating a swirling flow field in addition to the axial flow. This swirling flow field lifts sand and gravel particles, while the secondary circumferential and tangential flows promote more uniform fertilizer concentration distribution across the entire cross-section. This effectively manages potential sedimentation materials, thereby mitigating siltation and blockage issues in agricultural irrigation pipelines. Existing research has conducted detailed studies on multiple aspects such as its swirling efficiency and transport concentration [8,9,10]. However, the flow mechanism generated by the swirl within the guide-vane hydro-cyclone and the study of its solid wall shear stress remain incomplete, which limits the application of the guide-vane hydro-cyclone in agricultural irrigation problems.

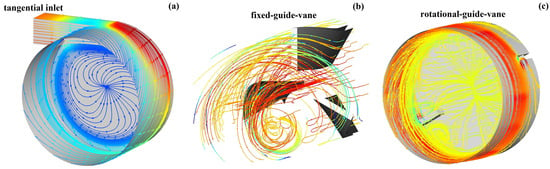

The flow mechanism of the guide-vane hydro-cyclone in irrigation pipelines may originate from the vortex core structure. The precessing vortex core (PVC) [11] is a large-scale coherent structure with helical spatial characteristics and stable dominant periodic time–frequency features, existing in flow with strong rotational effects. It influences the efficiency and stability of processes such as hydro-cyclone separation [12], hydro-cyclone mixing [13], and hydro-cyclone transport [14]. Bounded swirling flow also exhibits strong rotational effects and can be categorized into three types based on the rotational drive mechanism (shown in Figure 1): tangential inflow [15,16], fixed-guide-vane [17], and rotating-guide-vane [18]. Tangential inflow swirling flows are primarily applied in hydraulic conveying problems such as the screw conveying of sediment. Fixed-guide-vane swirling flow is also utilized in engineering applications such as sediment and particle transportation, chemical reaction stirring, and mixing. Rotating-guide-vane swirling flows are widely present in various hydraulic machines, including pipeline impeller pumps [19], propellers [20], and water turbines [21]. Consequently, studying swirling vortex cores facilitates the optimization of structural parameters and operating conditions for these applications.

Figure 1.

Schematic of rotational drive mechanism: (a) schematic of tangential inflow; (b) schematic of fixed-guide-vane; (c) schematic of rotating-guide-vane.

Regarding tangential inflow swirling flow, vortex eccentricity and vortex-core processing remain central research focuses. Yazdabadi et al. [22] discovered and analyzed vortex eccentricity, which reveals that the vortex core center exhibits both deviation from the geometric center of the circular cross-section and precession relative to the geometric center. Wang et al. [23], Wei et al. [24], and Zhao et al. [25] further considered that vortex eccentricity primarily arises from the spatially asymmetric characteristics of tangential inflow conditions, subsequently proposing improvements to these inflow conditions. Research indicates that the improved symmetric tangential inflow condition not only significantly reduces vortex eccentricity but also enhances hydro-cyclone separation efficiency. Regarding the spatiotemporal evolution of vortex cores, Derksen et al. [26] characterized the spatial position of advancing vortex cores using the minimum pressure value in the flow cross-section, Dong et al. [27] combined the Liutex core line identification with POD to study the wake field of a supersonic micro-vortex generator (MVG), revealing the physical significance of POD modes in various flows. Chen et al. [28] investigated the rotating vortex core using flow modal analysis, identifying the dominant modal structure driving the rotational evolution and its corresponding time period. The spatiotemporal evolution of precessing vortex cores inevitably involves fluctuations in angular velocity and pressure fields. Kumar et al. [29] analyzed the velocity spectrum, turbulent kinetic energy spectrum, and pressure spectrum at various spatial locations within precessing vortex cores. The results indicate no significant correlation between the dominant frequency of precessing vortex cores and Reynolds number.

Research on PVCs in rotating-guide-vane induced swirling flow primarily focuses on axial-flow hydraulic machinery. The rotation of the internal impeller drives high-speed fluid swirling, forming a bounded swirling flow within the downstream duct. Such vortex cores, formed through the interaction of residual swirl and non-uniform complex flow, exhibit intense pressure pulsations that readily trigger flow-induced vibration damage. Furthermore, the low-pressure property of the vortex core itself is prone to causing cavitation damage. Patel et al. [30] employed Large Eddy Simulation (LES) to investigate the spatial distribution of vortex cores, revealing that flow structures such as PVCs and vortex breakup cause axial asymmetry in the flow. Zhang et al. [31] employed LES to investigate non-reaction flow at different Swirl numbers, capturing PVCs, vortex separation, and instability at the trailing edge of the blunt body recirculation zone. Power spectral density analysis at monitoring points revealed precession characteristics in the flow, with precession motion gradually attenuating along the flow direction.

Compared to tangential inflow vortex flows like those found in hydro-cyclone separators, vane-type vortex separators focus more on the dominant frequency of the vortex core and the pulsation frequency of the surrounding flow. For example, Wang et al. [32] employed LES to capture the evolution characteristics of the PVC in a hydro-cyclone. They then compared the pressure pulsation spectral characteristics of the vortex generator with and without a Venturi tube configuration using Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) and Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT) methods. The results indicate that the presence of a Venturi tube significantly enhances the vortex intensity of the vortex generator, thereby influencing its precessing vortex core characteristics.

Current research on fixed-guide-vane swirling flow primarily focuses on time-averaged flow patterns, inductive analysis of swirling flow structures, and complex relationships between operating parameters and physical quantities such as Swirl number, rotational kinetic energy, and pressure drop. For example, experiments by Li et al. [7], Song et al. [8], and others revealed the evolution patterns of flow downstream of guide-vane-type cyclones. The results indicate that the guide-vane torsion angle exhibits a negative correlation with axial flow velocity, while radial and tangential velocity components show a significant upward trend with increasing torsion angle. Systematic studies by Tao et al. [9], Wei et al. [10], and Zhang et al. [33] indicate that a helical flow pattern with enhanced flow intensity and improved stability forms when the ratio of guide-vane height to cyclone inner diameter ranges between 0.5 and 0.7. The circumferential velocity peaks when the guide-vane height is 30 mm (height-to-diameter ratio of approximately 0.6). Existing research on fixed-guide-vane swirling flows has paid limited attention to their spatiotemporal evolution characteristics. Discussions on the flow mechanisms have not sufficiently explored the intrinsic relationship between flow structures like vortex cores and the spectral characteristics of the flow.

In summary, among various studies on bounded swirling flows driven by different mechanisms, research on tangential inflow and rotating-guide-vanes has established intrinsic coupling mechanisms and rational explanations for the spatial flow characteristics and time–frequency characteristics through PVC structures. However, studies on fixed-guide-vane swirl fields lack a comprehensive spatiotemporal coupling model to deeply explore flow mechanisms, hindering further optimization of fixed vane parameters and improvements in hydraulic conveying efficiency. Moreover, swirling flow exerts intense wall shear stresses on solid surfaces during interaction, and the form of wall shear stress in fixed-guide-vane swirling flow remains unclear. Therefore, this study investigates the PVC structure and wall shear stress of the flow based on the bounded swirling field of the guide-vane hydro-cyclone. This is achieved through numerical LESs and physical PIV experiments. The modal decomposition method is applied to extract the spatiotemporal evolution dynamics of the PVC structure. Characteristic forms of wall shear stress under various operating conditions are presented. The complex evolutionary characteristics of the composite PVC structure in reduced-order models of swirling flow are explored, enriching the theoretical framework concerning coherent structures in bounded swirling flow. The composite PVC structure of a guide-vane swirling flow is incorporated into the research system of swirling flows.

2. Flow Sample Acquisition and Testing

2.1. Research Condition Setup

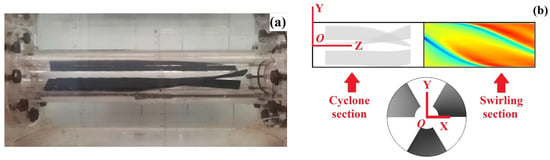

This study employs a vane-type hydro-cyclone, which induces swirling flow by imposing boundary conditions through fixed vanes, thereby generating a bounded swirling flow within the pipeline [7]. Guide-vane hydro-cyclone is primarily used in hydraulic conveying systems, where vanes force axial flow in pressurized pipelines to produce stable tangential velocity components. A photograph of the guide-vane hydro-cyclone is shown in Figure 2a. The guide-vanes are fixed inside a circular pipe. The vanes are made of PMMA and have been given a matte finish to minimize refraction of the laser beam [8]. The hydro-cyclone connects to the pressurized pipeline system with an inner diameter of d = 0.1 m. The key geometric parameters of the guide-vanes in this study are as follows: The axial projection length of the guide-vanes varies between 0.3 m and 0.5 m. Each guide-vane consists of a straight section and a curved section, with the straight section fixed at 0.1 m in length. The lb/l ratio (lb: the curved segment length; l: the total guide-vane length) is set to 2/3, 5/7, 3/4, 7/9, and 4/5. The height of a single guide-vane is 35 mm (0.035 m), with a thickness of 5 mm (0.005 m). The curved section design was achieved through curvature control, specifically rotating the guide-vane by 1° every 20 mm along its length. At the assembly level, three guide-vanes were employed, evenly spaced at 120° intervals around the circumference. The pipe section housing the guide-vane is termed the vane section (0.5 m long), while the immediately downstream pipe section is designated as the swirling section. This study normalizes the remaining length parameters using the pipe diameter as the characteristic length for the flow domain. The overall structural parameters of the guide-vane hydro-cyclone model and its coordinate establishment method are shown in Figure 2b. The flow condition parameters were selected based on previous relevant studies. The Reynolds number Re was defined as Re = ρud/μ, with Re = 140,000 and Re = 210,000 chosen as flow condition parameters. The study was conducted at a constant temperature of 20 °C. The final research conditions are shown in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Structure and coordinate establishment of the guide-vane hydro-cyclone. (a) Photograph of the guide-vane hydro-cyclone; (b) structural parameters and coordinates.

Table 1.

Specific information of research case setup.

2.2. Numerical Simulation Setup

The numerical simulation process of this study was completed in 2025 at the graphics workstation located in Shanxi Key Laboratory of Collaborative Utilization of River Basin Water Resources and Taiyuan University of Technology. This study investigates the homogenized flow characteristics and spatiotemporal evolution of a bounded swirling flow. Therefore, LES-type turbulence models are applied to analyze the large-scale vortex structures of the flow in spatiotemporal dimensions; the temporal and spatial scales of the flow samples obtained from numerical simulations are standardized. This simulation employs Ansys Fluent® (v19.0), utilizing the RNG k-ε turbulence model for accelerated convergence of the initial flow iteration. Subsequently, the WMLES model is applied to analyze the transient unsteady flow, capturing the generation, development, and dissipation of large-scale vortex structures. The flow sampling requirements can be referenced from the authors’ previous studies [34,35]. The governing equations applied are

is the fluid velocity after filtering through the physical space; is the fluid pressure after physical space filtration; ρ is the fluid medium density, considered constant for an incompressible flow (ρ = 998.2 kg·m−3); ν is the fluid medium friction coefficient ν = μ/ρ, with the dynamic friction coefficient as a constant (μ = 0.001003 Pa·s); fi represents the total force acting on a fluid particle, primarily accounting for gravity (local gravitational acceleration g = −9.797 m·s−2); τij denotes the sublattice stress; μt is the eddy viscosity coefficient; is the strain rate tensor; τkk represents the isotropic component of the sublattice stress, incorporated into the pressure term; K is the Karman constant; dwall is the wall distance; CSmag is the Smagorinsky constant; Δ is the grid characteristic length; S is the strain rate; and y+ is the wall Distance Estimation.

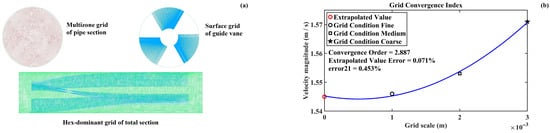

Regarding the computational domain and mesh configuration for the bounded swirling flow, we first consider the computational domain boundary conditions. We reserve a region upstream of the vane section equivalent to 10 times the pipe characteristic length to allow the flow to fully develop. The length of the downstream swirling section is set to 50 times the pipe characteristic length. The computational domain inlet is configured as a velocity inlet with initial velocity input, the outlet as a pressure outlet serving as the pressure reference, and the remaining regions as fixed walls with wall roughness based on measured acrylic values. Next, both the steady-state RNG k-ε turbulence model using the Standard Wall Function and the transient WMLES turbulence model require the first wall-adjacent grid layer to satisfy y+ ≈ 30~100. Therefore, a fully unstructured hexahedral mesh is directly generated for the entire flow domain. Based on prior research findings [9,10], a grid spatial characteristic length of 0.002 m was directly selected for meshing. The final computational domain and mesh configuration are illustrated in Figure 3a.

Regarding the numerical simulation’s discretization scheme settings, the Coupled Pressure–Velocity Coupling Scheme was employed. For spatial discretization, the 2nd Order Upwind Scheme was used for pressure discretization, the Least Squares Cell-Based Algorithm was used for gradient discretization, and the Bounded Central Differencing Scheme was applied for momentum discretization. The time discretization format employs Bounded 2nd Order Implicit.

The explicit relaxation factors for momentum and pressure were set to 0.5. Regarding the convergence condition, the continuous residuals were set to 1 × 10−5, the residuals for the flow velocity in all directions were set to 1 × 10−7, and the residuals for turbulent kinetic energy and specific dissipation rate were set to 1 × 10−7. The transient WMLES simulation was conducted after the steady-state RNG k-ε simulation met the convergence condition.

CFD numerical simulation necessitates the evaluation of computational grid convergence to eliminate potential impacts on computational results stemming from the grid division of the corresponding computational domain. As illustrated in Figure 3b, under the condition of a Reynolds number Re = 140,000, comparative models with grid sizes of 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0 mm, and a guide-vane length of 0.40 m, were established to systematically verify the influence of grid size on the average flow velocity amplitude along various measurement lines in Figure 4c of the follow subsection. The numerical simulation results indicate that when the grid cell size is 2.0 mm, the error in average flow velocity amplitude compared to the 1.0 mm model is less than 0.5%. Therefore, 2.0 mm was ultimately selected as the standard grid parameter for subsequent fluid numerical simulations.

Figure 3.

Schematic of calculation domain and meshing condition: (a) schematic of grid condition; (b) Grid Convergence Index analysis.

2.3. Testing Through Numerical Simulation

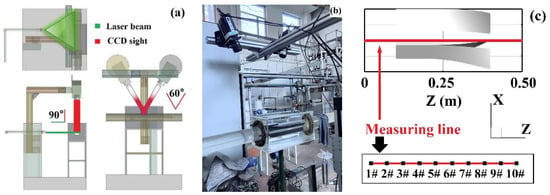

The physical experiment data for Particle Image Velocimetry (Dantec Dynamics A/S., Copenhagen, DK) in this study was collected and processed in 2024, and the particle image velocimetry system was sourced from Shanxi Key Laboratory of Collaborative Utilization of River Basin Water Resources and Taiyuan University of Technology. We validated the numerical simulation results using a particle image velocimetry (PIV) system. Physical experiments were conducted employing a 2D3C-PIV velocity measurement system (2Dimension and 3Cartisan-Particle Image Velocimetry) within a pipeline circulation system. This optical method measured the velocities in a swirling flow. The experimental setup and PIV apparatus are shown in Figure 4a. In the physical experiment, multiple measurement points were arranged at the target cross-section inside the guide-vane hydro-cyclone using a calibration device. Laser illumination was then applied to the target cross-section to reflect light off the tracer particles dispersed in the flow. Two high-speed CCD cameras captured images, which were subsequently processed through cross-correlation calculations and other methods to obtain the flow velocity results at the measurement points. The photograph taken during the imaging process is shown in Figure 4b, while the cross-section and measurement points are shown in Figure 4c. All parameters of PIV setup for flow sample acquirement are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Specific information and parameters of PIV setup.

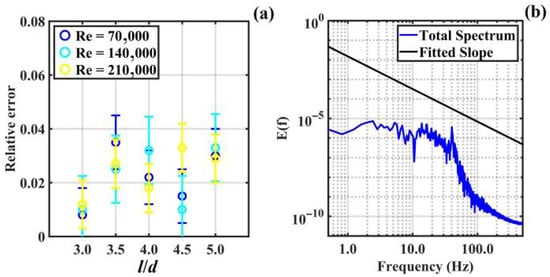

Figure 5a shows the verification of the measured flow velocity results from the physical test against the corresponding numerical simulation results. The relative error between numerical simulation results and physical test results generally ranges from 1.00% to 3.00%, with an average not exceeding 2.50%. Combined with the uncertainty analysis of the physical tests [35], the error bars are also shown in Figure 5a, indicating that the overall uncertainty of the numerical simulation is less than 5.00%. LES typically requires capturing large-scale turbulent oscillations, i.e., analyzing vortices in the energy-bearing scale region alongside those in the inertial sub-region. Therefore, comparing the turbulent oscillation spectrum with the Kolmogorov−5/3 power law confirms the feasibility of LESs. The energy spectrum measured at the study site is shown in Figure 5b. The relative error between the spectral slope of the inertial sub-scale region and the −5/3 power law straight line is less than 2.00%. Furthermore, considering the relative error and uncertainty between the numerical simulation results in Figure 5a and the physical test results, the overall uncertainty of the numerical simulation results in this study is generally less than 5.00%. Therefore, the numerical LES in this study is considered effectual.

Figure 4.

PIV setup: deployment of physical particle image velocimetry experiment: (a) schematic of PIV system; (b) photograph of PIV system; (c) deployment of measuring lines.

Figure 5.

Verification of simulation error and LES testification: (a) verification of simulation error; (b) LES testification.

2.4. Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD) Process

This study employs the POD method to analyze the mean flow characteristics and spatiotemporal evolution patterns of swirling flows. The numerical simulation results for the internal flow in hydro-cyclone devices with varying guide-vane lengths serve as flow samples for processing the swirling flow samples. The current POD process is based on the energy basis of turbulence fluctuations. The theoretical basis for establishing the reduced-order model via the Galerkin method is presented as follows [34,35]:

The differential equations governing fluid motion are described as

where F(·) represents spatial differentiation or integration operations present in the fluid motion equations. We assume that the linear algebraic equation system transformed from (2) is

Then, the inner product uTu of the exact solution uT = {u1, u2, …, un} to the linear algebraic system in (3) defines an n × n inner product space L2.

There exists an infinite-dimensional set of basis functions φ = {φ1, φ2, …, φn, …}. A linear combination of these basis functions φ can linearly represent u(x, t):

In Equation (4), a(t) represents the time coefficients determined by the linear system of equations under initial and boundary conditions. The basis functions φj(x) satisfy orthogonality in the inner product space:

In Equation (5), m and n belong to the set j = 1, 2, ……, J.

Introducing the Galerkin method, the trial function and time coefficients are combined into a linear combination. The original infinite-dimensional linear combination is truncated at a certain point, yielding a finite reduced-order linear combination:

In Equation (6), u^(x, t) represents the approximate solution of u(x, t), and i = 1, 2, ……, I denotes the finite values. The error between this approximate solution u^(x, t) and the exact solution u(x, t) is given by

This error e represents the residual in the weighted residual method.

3. Results

3.1. Precessing Vortex Cores’ Spatial–Temporal Evolution in Vane Section

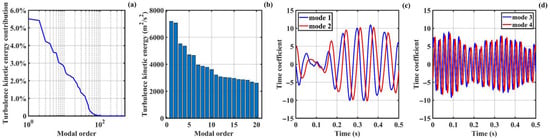

Considering that the PVC structure of the swirling field within the guide-vane hydro-cyclone exhibits only quantitative differences rather than qualitative variations under different conditions. The increasing of Reynolds number primarily alters the rotational effect of the PVC structures, which is quantified as an increase in the amplitude of vorticity as a physical indicator. Meanwhile, the length of the guide-vane quantitatively changes the spatial position of the PVC structures. The analysis focuses solely on the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of the PVC structure under the operating conditions of guide-vane length l = 0.3 m and Reynolds number Re = 140,000. The vane section was selected as the computational domain, capturing 500 spatial flow snapshots (0.001 s integration). The snapshot method with POD was applied to extract flow modes. The contribution of the top 500 modes to the turbulent kinetic energy in the vane section is shown in Figure 6a. The horizontal axis represents the mode order of the top 500 modes decomposed by the POD method, while the vertical axis indicates the ratio of turbulent kinetic energy contribution for these modes to the total turbulent kinetic energy. Overall, the dominant modes in the vane section flow are relatively concentrated. The truncation error for the first 50 modes is 4.94%, the truncation error for the first 100 modes is 0.15%. Beyond the 100th mode, the contribution of each subsequent mode to the turbulent kinetic energy is less than 0.1%. This indicates that the turbulence pulsations in the vortex-generating flow exhibit relatively low randomness, with strong quasi-periodicity and directional dominance. The first and second modes contribute 5.52% and 5.42% of the turbulent kinetic energy, respectively. The third and fourth modes account for 4.24% and 4.11%, while the fifth and sixth modes contribute 3.61% and 3.58%. The turbulent kinetic energy contributions of every two consecutive modes in the vane section are approximately equal. Furthermore, selecting the top 20 modes as shown in Figure 6b, the relative magnitudes of the turbulent kinetic energy between adjacent modes are 101.77%, 103.04%, 100.89%, 102.30%, 104.8%, 104.32%, 100.94%, 102.72%, 101.32%, and 102.96%. The trend of nearly equal relative turbulent kinetic energy between adjacent modes persists throughout, suggesting the potential existence of mode-pairing phenomena in a bounded swirling flow. Consequently, further analysis considering mode pairing is presented in Figure 6c,d, where adjacent modes appear in pairs with identical harmonic forms and similar amplitudes. Mode 2 lags behind Mode 1 by approximately 0.02 s, while Mode 4 lags behind Mode 3 by approximately 0.01 s. The paired POD modes represent transient flow phenomena at the same frequency, essentially reflecting the spatial evolution of the same flow pattern. This indicates that the POD modes of the bounded swirling flow studied here exhibit a pairing phenomenon. Each pair of modes is complementary to each other, containing similar energy and flow structures, but with a certain phase difference.

Figure 6.

Turbulence kinetic energy and time coefficient in vane section: (a) TKE contribution curve; (b) TKE of 1st 20 modes; (c) time coefficient of Modes 1 and 2; (d) time coefficient of Modes 3 and 4.

The flow structures corresponding to Modes 1 to 4 are further illustrated in Figure 7a. Vortex cores are represented by the magnitude of axial swirling, distinguished by their rotational directions at different spatial locations. The corresponding FFT spectra for these modes are shown in Figure 7b. As illustrated in Figure 7a, the first and second modes exhibit the following characteristics: Within the vane section, the vortices of the swirling flow are spatially arranged along the guide-vanes, distributed sequentially in the flow direction with alternating positive and negative rotation. This forms three columns of helically precessing vortices rotating at 120° azimuthal intervals within this zone. The spectra corresponding to the first and second modes are shown in Figure 7b. The dominant frequencies of Modes 1 and 2 are identical at 14 Hz, with nearly identical spectral shapes but a relative peak difference of 9.42%. Given the background flow fundamental frequency of u/d = 14 Hz, it is evident that the dominant frequencies of these two modes are approximately equal to the flow fundamental frequency. Therefore, these modes are considered to represent the background flow mode, embodying the fundamental pulsation component of the bounded flow. As shown in Figure 7a, for the third and fourth modes, according to Reference 18, the coherent structures corresponding to Modes 3 and 4 represent the precessing vortex core modes of a swirling flow. Positive and negative precessing vortex cores develop upstream along the flow direction, with adjacent vortex cores intertwining and precessing downstream. The advancing vortex cores exhibit relative continuity, with the spatial positions of the positive and negative cores in Modes 3 and 4 being opposite. The spectra corresponding to Modes 3 and 4 are shown in Figure 7b. Both modes share a dominant frequency of 40 Hz, exhibit nearly identical spectral shapes, and display a relative peak difference of only 2.64%.

Figure 7.

Coherent structure in vane section: (a) counter by yellow iso-surface ωz = 0.5 s−1, indigo iso-surface ωz = −0.5 s−1; (b) frequency spectrum.

3.2. Precessing Vortex Core Spatial–Temporal Evolution in Swirling Section

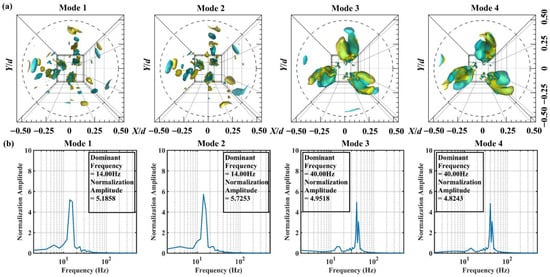

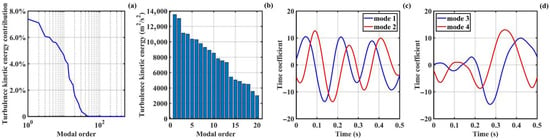

Similarly, the snapshot method with POD was applied to extract flow modes in the swirling section. The contributions of turbulent kinetic energy from the top 500 modes in the swirling section flow are shown in Figure 8a. Overall, the dominant modes in the swirling section flow are more concentrated compared to those in the vane section, with the contribution rate of turbulent kinetic energy from modes beyond the 40th order being less than 0.1%. The truncation error for the first 50 modes is less than 0.07%, and the truncation error for the first 100 modes is less than 0.01%. The swirling section flow also exhibits strong quasi-periodicity and directional dominance. The first and second modes contribute 5.52% and 5.42% of the turbulent kinetic energy, respectively, while the third and fourth modes contribute 4.24% and 4.11%, respectively. The fifth and sixth modes account for 3.61% and 3.58%, respectively. This indicates that the turbulent kinetic energy contributions of every two consecutive modes in the swirling section are also approximately equal. The top 20 modes of the swirling section are shown in Figure 8b, with relative turbulent kinetic energy ratios between adjacent modes of 103.98%, 101.22%, 100.83%, 105.43%, 104.47%, 103.56%, 134.51%, 103.48%, 101.54%, and 118.09%. The trend of nearly equal turbulent kinetic energy ratios between adjacent modes is prevalent, further indicating the modal pairing phenomenon in the bounded swirling flow. Further analysis considering modal pairing is shown in Figure 8c,d. Mode 2 lags behind Mode 1 by approximately 0.04 s, and Mode 4 lags behind Mode 3 by approximately 0.05 s. Compared to the time coefficient curves in the vane segment shown in Figure 6c,d, the time coefficient curves corresponding to the vortex segment exhibit a more gradual slope.

Figure 8.

Turbulence kinetic energy and time coefficient in swirling section: (a) TKE contribution curve; (b) TKE of 1st 20 modes; (c) time coefficient of Modes 1 and 2; (d) time coefficient of Modes 3 and 4.

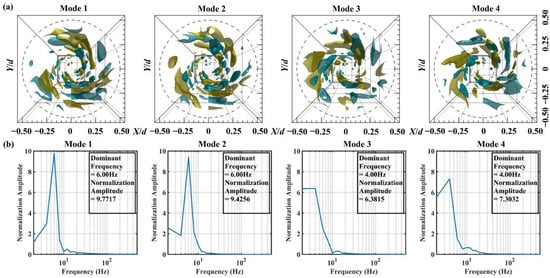

The flow structures corresponding to Modes 1 to 4 are further illustrated in Figure 9a, where the vortex cores are similarly represented by the magnitude of the axial swirling of the swirling flow. The corresponding FFT spectra for these modes are shown in Figure 9b. As depicted in Figure 9a, for the first and second modes, the vortex cores within the swirling flow are distributed sequentially along the direction of the time-averaged PVC structure’s spiral precession, with alternating positive and negative rotation. This arrangement forms three sets of composite PVC structures rotating at 120° intervals within this region. Compared to the vane section in Figure 9a, the vortex core within the vortex flow section lacks complete morphology. This indicates that momentum exchange occurs between the vortex cores during their spatiotemporal precession, leading to the fragmentation of the PVC. The spectra corresponding to the first and second modes are shown in Figure 9b. The dominant frequencies of Modes 1 and 2 are identical at 6 Hz, with a relative spectral peak difference of only 2.52%. The coherent structures of the third and fourth-order modes, as depicted in Figure 7a, exhibit morphology similar to that of the first and second modes. The spectra corresponding to Modes 3 and 4 are shown in Figure 9b. Modes 3 and 4 share an identical dominant frequency of 4 Hz, with a relative peak difference of 14.44%. Spatially, the coherent structures of these four modes represent the low-frequency helical precession of the PVC structure [18]. In terms of time–frequency characteristics, the dominant frequencies of Modes 1 to 4 are 6 Hz and 4 Hz, respectively, which are lower than the background flow fundamental frequency of 14 Hz. The fundamental frequency of the swirling flow, calculated using the guide-vane characteristic length, is about u/l = 5 Hz. The dominant frequencies of Modes 1 to 4 are similar to the fundamental frequency of the swirling flow, with their average frequency approximating the fundamental frequency of the swirling flow. Therefore, these modes are considered swirling flow modes, representing the rotational pulsation component of the bounded swirling flow. This indicates that the flow frequencies in the swirling section (4 Hz, 6 Hz) differ from the fundamental frequency (14 Hz) of the dominant mode in the bounded flow of the vane section. The swirling section has transitioned from swirling flow to become the dominant flow mode in this region.

Figure 9.

Coherent structure in swirling section: (a) counter by yellow iso-surface ωz = 0.5 s−1, indigo iso-surface ωz = −0.5 s−1; (b) frequency spectrum.

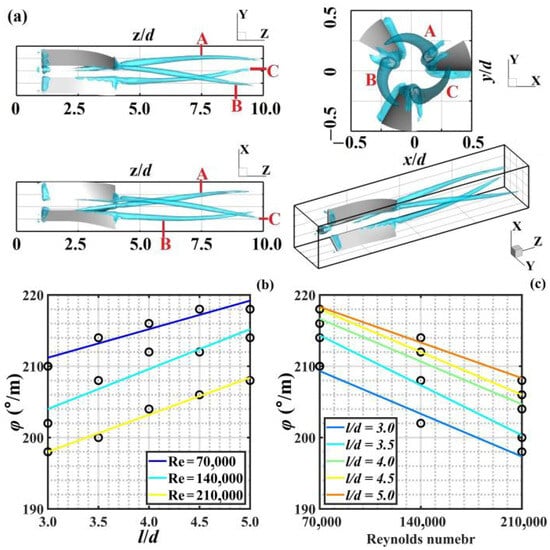

3.3. Precessing Vortex Core Identification of Reconstructed Flow

Increased Reynolds number will lead to circumferential precession of the precessing vortex core [36,37]. Considering the transient property of the precessing vortex core, a reduced-order model was established using the top 100 POD modes to reconstruct the bounded swirling flow. Further, the Q-criterion was applied to the reconstructed flow to identify the precessing vortex core of the swirling flow. Considering that the morphology of the precessing vortex core in the guide-vane hydro-cyclone exhibits qualitative similarity across different operating conditions, differing only quantitatively in spatial position and rotational intensity amplitude, the precessing vortex core morphology was demonstrated using a guide-vane length l = 0.3 m and a Reynolds number Re = 140,000 as an example, as shown in Figure 10a. Overall, the swirling flow generates three PVCs centered around three fixed-guide-vanes. These PVCs exhibit a tendency to spiral downstream along the guide-vane twist direction. The PVCs roll downstream from the flow separation point at the geometric boundary near the guide-vane tip. Within the flow cross-section, their initial spatial positions are close to the guide-vane edge along the radial direction of the circular cross-section. The rotation direction of the vortex cores is identical to the guide-vane twist direction, both being counterclockwise (observed from downstream to upstream). The rotational intensity of the vortex cores induced by each guide-vane is approximately equal, and the twist pattern exhibits 120° rotational symmetry around the circumferential direction. As the flow progresses downstream, the twist gradually propagates counterclockwise around the circumference from one guide-vane to the cross-sectional projection position of another vane. For example, in Figure 10a, the vortex core induced by guide-vane A propagates to guide-vane B at the flow position z/d = 7.5. Similarly, the vortex core induced by guide-vane B crosses over to guide-vane C at the flow position z/d = 7.5; the same applies to guide-vane C. Considering that the vortex cores induced by each guide-vane occupy specific radial positions within the cross-section and undergo helical precessing along the circumferential direction, an analysis of the circumferential helical precessing characteristics of these vortex cores is conducted. As shown in Figure 10b, the circumferential angle φ traversed per unit length during the PVC’s motion follows a linear relationship with respect to the ratio of the guide-vane length to the duct characteristic length l/d: φ = 4.0 l/d + 199.2 (Re = 70,000), φ = 5.6 l/d + 187.2 (Re = 140,000), φ = 5.2 l/d + 182.4 (Re = 210,000). As shown in Figure 10c, the circumferential advance angle φ per unit length of the vortex core also follows a linear relationship with Reynolds number: φ = −8.5714 × 10−5 Re + 215.3333 (l/d = 3.0), φ = −1.0000 × 10−4 Re + 221.3333 (l/d = 3.5), φ = −8.5714 × 10−5 Re + 222.6667 (l/d = 4.0), φ = −8.5714 × 10−5 Re + 224.0000 (l/d = 4.5), φ = −7.1429 × 10−5 Re + 223.3333 (l/d = 5.0).

Figure 10.

Multi-precessing vortex core analysis: (a) Q-criteria identification of reconstructed flow; (b) circumferential rotation angle curves with variation in l/d; (c) circumferential rotation angle curves with variation in Re.

Overall, as the Reynolds number of the bounded swirling flow increases, the circumferential precession of the swirling vortex core exhibits a linear weakening trend. This occurs because, for a fixed pipe characteristic length, an increase in Reynolds number signifies higher flow velocity but no change in the swirling boundary of the guide-vanes. Consequently, the swirling flow velocity decreases relative to the pipe flow velocity, leading to a relative weakening of the swirling flow effect. As the relative length l/d of the guide-vane to the pipe increases, the circumferential precession distance of the advancing vortex core exhibits a linear enhancement trend. This trend primarily arises because an increase in the relative length of the guide-vane to the pipe increases the rotational angle per unit length of the guide-vane, thereby enhancing the degree of the swirling effect generated by the boundary-forced flow.

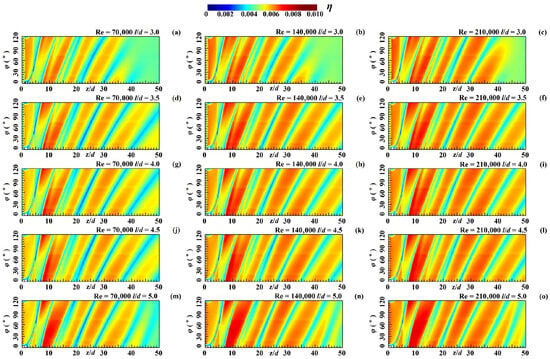

3.4. Wall Shear Stress of Bounded Swirling Flow on Pipe Boundary

The wall shear stress τ acting on the inner wall of the guide-vane hydro-cyclone under counter-rotating swirling flow conditions is analyzed. After dimensional normalization, the wall shear stress τ is referred to as the wall shear stress coefficient η = τ/q, where q = 0.5 ρu2 is the dynamic hydraulic pressure corresponding to the operating condition. Considering the hydro-cyclone’s circumferential 120° rotational symmetry, the distribution of the wall shear stress coefficient for each operating condition is shown in Figure 11. Overall, the stress coefficient amplitude near the guide-vane location (leading edge position z/d = 0, φ = 0) downstream is approximately zero, representing the lowest value across the entire field. This region with near-zero stress coefficients exhibits a rotational precession trend downstream. The stress coefficient amplitude between guide-vanes is relatively high, and this trend also develops downstream with a rotational precession tendency. Typically, the region with the maximum stress coefficient amplitude across the entire field develops at a certain distance from the trailing edge of the adjacent guide-vane, where swirling flow begins. Specifically, as the Reynolds number increases, the stress coefficient amplitude exhibits a significant upward trend. This indicates that, at higher Reynolds numbers, the dynamic hydraulic pressure of the axial flow further intensifies the rotational effect of the circumferential swirl. Furthermore, as the ratio of the guide-vane to the pipe characteristic length (l/d) increases, the stress coefficient amplitude significantly rises while the swirling jets markedly strengthen. Regions exhibiting relatively abrupt stress transitions are prone to stress fatigue and cavitation on solid surfaces. As shown in Figure 11, apart from the sharp stress transition at the guide-vane-to-wall connection angle, the downstream region with intense stress transitions extends along the flow’s circumferential precession direction. Furthermore, as the region with intense stress amplitude transitions extends downstream, the angular rotation per unit length decreases. This indicates that, as the swirling flow moves away from the guide-vane, the circumferential rotational effect of the flow undergoes decay along the flow path.

Figure 11.

Wall shear stress coefficient of 1/3 symmetric pipe boundary: (a) Re = 70,000 & l/d = 3.0; (b) Re = 140,000 & l/d = 3.0; (c) Re = 210,000 & l/d = 3.0; (d) Re = 70,000 & l/d = 3.5; (e) Re = 140,000 & l/d = 3.5; (f) Re = 210,000 & l/d = 3.5; (g) Re = 70,000 & l/d = 4.0; (h) Re = 140,000 & l/d = 4.0; (i) Re = 210,000 & l/d = 4.0; (j) Re = 70,000 & l/d = 4.5; (k) Re = 140,000 & l/d = 4.5; (l) Re = 210,000 & l/d = 4.5; (m) Re = 70,000 & l/d = 5.0; (n) Re = 140,000 & l/d = 5.0; (o) Re = 210,000 & l/d = 5.0.

4. Discussion

4.1. Precessing Vortex Core Mode Pairing and Flow Frequency

This study extracts precessing vortex core structures within the swirling flow through the modal decomposition method, revealing the modal pairing phenomenon that exists in both the vane section and the swirling section. Specifically, adjacent modes exhibit similar turbulent kinetic energy contribution rates and similar spectral characteristics, with a certain phase lag. This phenomenon indicates that in the swirling flow, the flow structure is not completely random but rather exhibits certain spatial symmetry and quasi-periodicity in time.

The phenomenon of modal pairing may be related to the vortex pairing mechanism in the swirling flow field, where adjacent vortex structures interact and form complementary flow patterns during their downstream evolution. In this study, the vortex structures within the vane section are arranged along the guide-vanes, exhibiting a 120° circumferential symmetric distribution. In the swirling section, due to the enhanced momentum exchange between vortex cores, the vortex structures gradually break down, but modal pairing still persists, indicating that even during the evolution of large-scale vortex structures, the flow maintains a certain degree of coherence and structural stability. Since the base flow is rotationally symmetric, there is no preferred direction of rotation. Any physically realizable disturbance (which must be real) can be regarded as a linear combination of these two conjugate modes. A single complex mode is not physical; its conjugate mode must exist simultaneously to combine into a real disturbance field with a definite phase relationship [38].

The modal frequencies dominant in the vane section only relate to approaching flow velocity and pipe diameter. In this study the frequencies are 7 Hz, 14 Hz, and 21 Hz for different guide-vane lengths under the Reynolds number 70,000, 140,000, and 210,000. The modal frequencies dominant in the swirling section are listed in Table 3. The frequencies mainly relate to approaching flow velocity and guide-vane length.

Table 3.

Swirling flow frequencies of vane section.

This discovery holds importance for comprehending the energy transfer and vortex dynamics within the swirling flow. Future research could delve deeper into exploring the quantitative relationship between mode pairing, swirl intensity, and guide-vane geometric parameters, thereby providing a theoretical foundation for the optimal design of a guide-vane hydro-cyclone.

4.2. Local Head Loss of Swirling Flow

While swirling effect enhances particle suspension and mixing uniformity, it inevitably leads to additional head loss. This indicates that the energy consumption of the swirling flow is primarily concentrated in the strong shear zone induced by the guide-vane, while the high-efficiency region of the swirling flow is closely related to the circumferential precession path of the vortex core. As the relative length of the guide-vane l/d increases, the swirling intensity increases, which is beneficial for improving suspension and mixing efficiency. However, it is also accompanied by an increase in wall shear stress, which may lead to greater frictional losses and local energy consumption.

Therefore, in the design of practical agricultural irrigation systems, a balance needs to be struck between swirling efficiency and head loss. It is recommended to optimize the geometry of the guide-vane, adjust the installation angle of the guide-vane, or adopt gradually deforming guide-vanes to minimize energy loss while ensuring the swirl effect, thereby achieving efficient and energy-saving operation of the irrigation system. The local head loss coefficients for a guide-vane hydro-cyclone are shown in Table 4. The local head loss coefficient increases significantly with the increase in guide-vane length and decreases slightly with the increase in Reynolds number. Within the scope of this study, the local head loss coefficient generally ranges from 0.23 to 0.36.

Table 4.

Local head loss coefficient for guide-vane hydro-cyclone.

4.3. Wall Shear Stress of Guide-Vane Hydro-Cyclone

Wall shear stress is a key parameter for evaluating the impact of swirling flow on pipeline structures. The results of this study indicate that the stress distribution in the swirling flow field exhibits significant spatial heterogeneity and circumferential evolution characteristics: the stress in the near-wall region downstream of the guide-vanes is nearly zero, while stress concentration occurs in the region between the guide-vanes, and this high-stress area migrates downstream along the swirl direction. Through the analysis of wall shear stress in this study, it was found that the stress coefficient is lower in the near-wall region downstream of the guide-vane, while the stress in the region between the guide-vanes increases significantly. Furthermore, with the increase in Reynolds number and the length of the guide-vane, the stress amplitude is further enhanced.

This stress distribution pattern may have a significant impact on the long-term operational safety and durability of pipeline systems. High shear stress areas are prone to fatigue, wear, and even cavitation erosion of the wall materials, especially at the junction between the guide-vane edge and the wall, as well as in the downstream development zone. As the Reynolds number increases, the stress amplitude further rises, potentially exacerbating the risk of localized damage.

Therefore, in the design and maintenance of rotational flow irrigation pipelines, emphasis should be placed on material reinforcement and regular inspection in high-stress areas. Local stress concentration can be alleviated by optimizing the layout of guide-vanes, adding anti-erosion coatings, or adjusting operational parameters (such as flow velocity and guide-vane length), thereby extending the service life of the pipeline.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the spatiotemporal evolution of the multi precessing vortex core (PVC) and the distribution of wall shear stress within a guide-vane hydro-cyclone, employing a combined approach of numerical simulation (Large Eddy Simulation, LES) and physical experimentation (Particle Image Velocimetry, PIV). The following key conclusions, supported by quantitative data, were drawn.

Regarding vortex core structure and precession characteristics, the study revealed a significant modal pairing phenomenon within the flow field. In the vane section, modes 1 and 2 contributed 5.52% and 5.42% of the turbulent kinetic energy, respectively, while modes 3 and 4 contributed 4.24% and 4.11%. Flow frequency analysis further revealed a transition in flow state: the dominant frequency in the vane section was 14 Hz, consistent with the fundamental frequency of the incoming flow based on pipe diameter. In contrast, the dominant frequency in the downstream swirling section significantly decreased to the range of 4–6 Hz, aligning with the swirling characteristic frequency based on guide-vane length (approximately 5 Hz). This signifies a complete transition from basic pipe flow to swirling-flow dominance. Quantitative analysis of the circumferential precession of the vortex core showed a clear dependence on guide-vane geometry and flow conditions. The precession angle (φ) exhibited a linear positive correlation with the relative guide-vane length (l/d).

Concerning the distribution of wall shear stress, the study revealed its spatial heterogeneity and evolutionary characteristics. In the near-wall region downstream of the guide-vane wake, the wall shear stress coefficient approached zero, representing the lowest value in the entire field. In the region between adjacent guide-vanes, the stress coefficient increased significantly, with a magnitude approximately 0.1 times the dynamic pressure of the approaching flow (q). This high-stress region also exhibited a tendency to precessing circumferentially as the flow developed downstream. The analysis indicated that the magnitude of the wall shear stress coefficient showed a clear upward trend both with increasing Reynolds number (from 70,000 to 210,000) and with increasing relative guide-vane length l/d (from 3.0 to 5.0), suggesting that higher flow energy or longer guide-vanes intensify the shear effect on the pipe wall.

From an engineering application perspective, the study quantified the local head loss induced by the swirling flow. The local head loss coefficient ranged from 0.23 to 0.36, varying with operating conditions. For a fixed l/d, the coefficient slightly decreased with increasing Re. For a fixed Re, the coefficient increased significantly with increasing l/d. For example, at l/d = 5.0, the loss coefficient decreased from 0.3537 at Re = 70,000 to 0.3324 at Re = 210,000. Under the condition of Re = 140,000, the loss coefficient increased from 0.2439 to 0.3486 as l/d increased from 3.0 to 5.0. This provides a clear trade-off for optimizing guide-vane design: longer guide-vanes enhance swirling intensity by rotation effect of precessing vortex core, benefiting particle suspension and mixing uniformity, but also incur greater energy loss.

These specific data and patterns provide important theoretical foundations and design references for the design, performance prediction, and operational optimization of anti-clogging swirling devices in agricultural irrigation pipelines.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. (Yinghan Liu), Y.Z. and Y.L. (Yongye Li); methodology, Y.Z.; software, Y.Z. and Y.L. (Yongye Li); validation, Y.L. (Yinghan Liu) and Y.Z.; formal analysis, Y.L. (Yinghan Liu) and Y.Z.; investigation, Y.L. (Yinghan Liu), Y.Z., and Y.L. (Yongye Li); resources, Y.L. (Yongye Li); data curation, Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L. (Yinghan Liu) and Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z. and Y.L. (Yongye Li); visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, Y.L. (Yongye Li); project administration, Y.L. (Yongye Li); funding acquisition, Y.L. (Yongye Li). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51109155 & No. 51179116), the Natural Science Foundation of Shanxi Province (Grant No. 202303021211141), and the Graduate Education Innovation Project of Shanxi Province (Grant No. 2024KY178).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Shanxi Key Laboratory of Collaborative Utilization of River Basin Water Resources and Taiyuan University of Technology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, H.; Ling, G.; Hu, M.; Wang, W.; Hu, X. Physical Clogging Characteristics of Labyrinth Emitters under Low-Quality (Sand-Laden Water) Irrigation. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.T.; Li, Y.K.; Liu, Y.Z.; Jiang, Y.G. Eight emitters clogging characteristics and its suitability under on-site reclaimed water drip irrigation. Irrig. Sci. 2014, 32, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, S.L.; Wang, W.E.; H, X. Influence of the emitter with tooth-shape labyrinth flow channel on sediment deposition. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2023, 39, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.M.; Xu, X.; Yang, Q.L.; Wu, Y.; Bai, X. Influence of geometrical parameters of labyrinth passage of drip irrigation emitter on sand movement. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2017, 48, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Hu, X.; Wang, W.; Ma, X. Main influence indicators and regulatory pathways of emitter clogging under physical and chemical combination factors. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 310, 109383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Jaume, P.; Mengyao, L.; Yang, X.; Li, Q.; Li, Y. Physical, chemical and biological emitter clogging behaviors in drip irrigation systems using high-sediment loaded water. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 270, 107738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tao, S.; Song, X.; Zhao, Y. Study on Internal Flow Characteristics of Hydro-cyclone with Guide-vanes. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Sun, X.; Li, Y.; Ma, J.; Yang, X. Exploration of the Circumferential Velocity Structure Induced by Guide-vane-Type Spiral Flow Generators in a Pipe Flow. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2023, 149, 13495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Li, Y.; Song, X. Study of the Internal Cyclonic Flow Characteristics of Cyclones with Different Guide-vane Heights. Water 2022, 15, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Li, Y.; Song, X.; Tao, S. Analysis of Cyclone Spinning Effect with Different Guide-vane Heights. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syred, N. A review of oscillation mechanisms and the role of the precessing vortex core (PVC) in swirl combustion systems. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2006, 32, 93–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Prakash, O.; Brar, L.S. Analyzing the impact of inclined single and multi-inlet configurations on the turbulent flow in cyclone separators using large-eddy simulation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 376, 134111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Z.; Chen, S.; Wu, Z.; Huan, P. High mixing effectiveness lobed nozzles and mixing mechanisms. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2015, 58, 1218–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinast, D.; Kruggel-Emden, H. CFD modeling of pressure drop, pressure drop fluctuations and flow regimes in horizontal pneumatic conveying at low velocities using a two-fluid model. Powder Technol. 2025, 453, 120578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Doherty, T.; Griffiths, A.J.; Syred, N.; Bowen, P.J.; Fick, W. Experimental analysis of rotating instabilities in swirling and cyclonic flows. Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 2008, 7, 245–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.P.; Zhou, F.; Yang, D.L.; Yu, B.C.; Li, Y.Z. Effect of swirling flow on large coal particle pneumatic conveying. Powder Technol. 2020, 362, 745–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, K.; Jia, Z.; Li, P. Particle Transport and Deposition Characteristics in a Horizontal Pipe with a Swirling Flow Induced by Deflector Vane. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 083403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fava, T.C.L.; Massaro, D.; Schlatter, P.; Henningson, D.S.; Hanifi, A. Transition to turbulence on a rotating wind turbine blade at Rec = 3 × 105. J. Fluid Mech. 2024, 999, A54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Gao, A.K.; Liu, L.; Lu, X.Y.; Stevens, R.J.A.M. Evolution and instability of the tip vortices behind a yawed wind turbine. J. Fluid Mech. 2025, 1016, A20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Wang, Z.; Hu, P.; Deng, R.; Luo, W.Z.; Jiang, D.P. Wake topology and vortex structure evolution of a marine propeller with a fractured blade. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 095149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Luo, Z.; Guo, T.; Han, J. Numerical investigation of energy dissipation and vortex characteristics of a pump-turbine with splitter blades under the influence of rotating stall in the hump region. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 095155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdabadi, P.; Griffiths, A.J.; Syred, N. Investigations into the precessing vortex core phenomenon in cyclone dust separators. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 1994, 120, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Xu, D.L.; Chu, K.W.; Yu, A.B. Numerical study of gas–solid flow in a cyclone separator. Appl. Math. Model. 2006, 30, 1326–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Song, J.; Shi, M.; Zhang, H. Numerical simulation of the asymmetric gas phase flow in a volute cyclone separator. Prog. Nat. Sci. 2005, 15, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Shen, H.; Kang, Y. Development of a symmetrical spiral inlet to improve cyclone separator performance. Powder Technol. 2004, 145, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derksen, J.J.; Van den Akker, H.E.A. Simulation of vortex core precession in a reverse-flow cyclone. AIChE J. 2000, 65, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Cai, X.; Dong, Y.; Liu, C. POD analysis on vortical structures in MVG wake by Liutex core line identification. J. Hydrodyn. 2020, 32, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, R.; Huang, Z.; Li, G.; Qin, X.; Li, J.; Wu, X. Detached eddy simulation on the structure of swirling jet flow. J. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2022, 49, 929–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Vanka, S.; Banerjee, R.; Mangadoddy, N. Dominant Modes in a Gas Cyclone Flow Field Using Proper Orthogonal Decomposition. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 2562–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Menon, S. Simulation of spray–turbulence–flame interactions in a lean direct injection combustor. Combust. Flame 2008, 153, 228–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Han, S.; Liu, T.; Zhu, J.; Ma, H.Y. Research progress on aerodynamic performance simulation of combustion chamber based on very large eddy simulation. Aeroengine 2023, 49, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gong, K.; Zhao, H. Research on the influence of Venturi tube on pressure pulsation characteristics of hydro-cyclone. J. Propuls. Technol. 2025, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Sun, X.; Li, Y.; Tao, S. Hydraulic characteristics at the outlet section of a rotational flow generator with different guide-vane heights. J. Drain. Irrig. Mach. Eng. 2023, 41, 803–808+824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, Y. Proper orthogonal decomposition-Galerkin analysis of flow structure in moving-boundary annular flow. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 055129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Song, X. PIV Measurement and Proper Orthogonal Decomposition Analysis of Annular Gap Flow in a Hydraulic Machine. Machines 2022, 10, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentyabov, A.; Platonov, D.; Shtork, S.; Minakov, A. Numerical simulation of a double helix vortex structure in a tangential chamber. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2024, 107, 109398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutchenko, I.; Palkin, E.; Mullyadzhanov, R. LES study of the precessing vortex core mitigation by radial injection in a Francis turbine air model. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 578, 01018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Song, G.; Cui, J.; Gao, Q.; Wang, G.; Wu, X. POD and DMD analysis of dynamic flow structures in the recirculation region of an unconfined swirl cup. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2025, 16, 0111306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.