Abstract

A comprehensive two-year investigation (2024–2025) was conducted across Northeast China’s crucial grain production base to assess the status of maize diseases. Field surveys spanning three provinces and Inner Mongolia revealed a significant shift in the regional disease profile, with diagnosis performed by experienced personnel based on characteristic field symptoms. The results demonstrated that maize white spot (MWS) has emerged as a severe new threat, recording remarkably high disease severity indices exceeding 80 at multiple locations (e.g., LDD25-1: 86.83). Concurrently, gray leaf spot (GLS) was confirmed as the most prevalent foliar disease, forming stable areas of high severity in the eastern mountainous regions where its disease indices consistently surpassed 60 (e.g., LFS25-1: 65.26), thereby exceeding the impact of northern corn leaf blight. In contrast, stalk rot (SR) maintained a low field incidence rate below 10%, while other diseases such as Curvularia leaf spot and maize eyespot were only observed locally or were absent during the 2025 survey period. These findings underscore the emergence of MWS as a critical threat and affirm the dominant status of GLS, offering a scientific foundation for prioritizing disease management strategies in the region.

1. Introduction

Maize (Zea mays L.) serves as a fundamental component of global agriculture, providing essential resources for food, feed, and industrial applications. In China, it represents the most extensively cultivated cereal crop. Recent statistical data indicate that the national maize planting area reached 44.74 million hectares in 2024, with a total production of 294.92 million tons, accounting for 37.49% of the country’s total grain cultivation area [1]. Northeast China, recognized as a primary spring maize production zone, substantially contributes to this output, with an estimated cultivation area of 14 million hectares and an annual production of 117.27 million tons, representing approximately one-third and two-fifths of national totals, respectively [2]. However, the agricultural productivity of this vital region faces persistent challenges from various foliar and systemic diseases that can lead to substantial yield reduction and quality deterioration.

Among the significant foliar diseases, gray leaf spot (GLS) represents a major concern. Caused by Cercospora zeae-maydis and Cercospora zeina, GLS ranks among the most destructive foliar diseases affecting maize production globally [3,4]. Since its initial documentation in China’s Liaoning Province in 1991, GLS has become widely distributed across the Northeast, Northwest, and Southwest regions [5,6]. Although both pathogenic species were initially identified in Southwest China, C. zeina has emerged as the dominant pathogen and has progressively expanded northward, with disease outbreaks attributed to this species being increasingly reported throughout Northeast China [4,5,6,7].

Northern corn leaf blight (NCLB), induced by the fungal pathogen Exserohilum turcicum, represents another foliar disease of worldwide significance. The pathogen typically initiates infection in lower leaves, producing characteristic spindle-shaped lesions that can progress to affect the entire plant. This extensive colonization severely compromises photosynthetic efficiency and nutrient accumulation, resulting in kernel deformation and yield losses [8]. As an airborne disease favored by moderate temperatures and elevated humidity conditions, NCLB typically causes yield reductions of 15–20%, with pre-silking infections potentially leading to losses exceeding 40–50% [8].

Curvularia leaf spot (CLS), caused by Curvularia lunata, constitutes a widespread fungal disease with global distribution [9]. In China, the disease was first observed in Shandong Province during the late 1970s. By the 1990s, CLS had become established as the third most significant leaf disease following NCLB and southern leaf blight, causing substantial production losses in multiple regions [10]. While the extensive adoption of CLS-resistant cultivars subsequently reduced disease incidence and severity, recent investigations have documented a resurgence of CLS with elevated disease severity indices across several provinces, indicating renewed threats to maize production systems [11,12].

Maize eyespot (ME), caused by Kabatiella zeae, has emerged as a yield-limiting factor of increasing importance in Northeast China’s maize production belt. The cultivation of susceptible hybrids combined with continuous monoculture practices has contributed to disease proliferation, particularly under cool, moist environmental conditions [13,14].

Concurrent with these established foliar diseases, the emergence of novel pathogens requires ongoing surveillance. Maize white spot (MWS) has rapidly developed into a devastating foliar disease throughout Chinese maize production areas. Initially reported in Yunnan Province in 2020, MWS has demonstrated remarkably rapid dissemination, causing yield losses ranging from 10% to 50%, with severe cases experiencing losses up to 70% in southwestern production regions [15,16]. By 2024, the disease had extended northward, being confirmed in Shandong Province and a limited number of cities within Liaoning Province in Northeast China [17,18]. The etiology of MWS demonstrates considerable complexity and regional variation. While Phaeosphaeria maydis and Pantoea ananatis have been identified as primary pathogens in international contexts, recent Chinese investigations have established Epicoccum species (including E. latusicollum and E. sorghinum) and Setophoma zeae-maydis as predominant pathogens [18]. This dynamic and evolving pathogen profile emphasizes the continuously changing nature of disease threats and the associated challenges for accurate diagnosis and implementation of effective management strategies.

Beyond foliar pathologies, stalk rot (SR) caused by multiple Fusarium species presents dual threats through direct yield reduction and contamination of grains with hazardous mycotoxins. Stalk rot ranks among the most destructive maize diseases worldwide, inducing stalk lodging and typically reducing yields by 10%, with severe episodes potentially causing losses of 30–50% [19]. The disease has become widespread throughout Northeast China and has triggered significant epidemics in other major production zones, including the Huang-Huai-Hai region [19,20,21]. Pathogen composition demonstrates considerable complexity, involving species such as F. verticillioides, F. graminearum, and F. moniliforme, with specific prevalence influenced by local environmental and climatic conditions [22].

To systematically assess the occurrence and severity of major maize diseases in this critical production region, comprehensive field surveys were conducted during the maize maturity stage in September 2024, followed by subsequent investigations in September 2025. Our assessment was based on foliar symptom evaluation—an experience-dependent approach that is relatively suitable and convenient for large-scale surveys. The survey covered the three northeastern provinces of China (Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang), and in the 2025 survey cycle, two townships in Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, were additionally included to enhance geographical representation. Disease assessment focused on the severity of gray leaf spot (GLS), northern corn leaf blight (NCLB), Curvularia leaf spot (CLS), maize eyespot (ME), stalk rot (SR), and maize white spot (MWS). Notably, the 2024 survey documented the first confirmed occurrence of MWS in Liaoning, and the 2025 survey verified its northward expansion, establishing its emerging status throughout the region. This study aims to provide a preliminary and timely analysis of disease severity and geographical distribution, with particular emphasis on the emerging threat posed by MWS and the persistent challenges presented by other major diseases. The findings will establish a crucial scientific foundation for refining integrated disease management strategies and guiding breeding initiatives aimed at protecting maize yield and quality, thereby contributing to the safeguarding of production in one of China’s most significant agricultural regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Time and Location

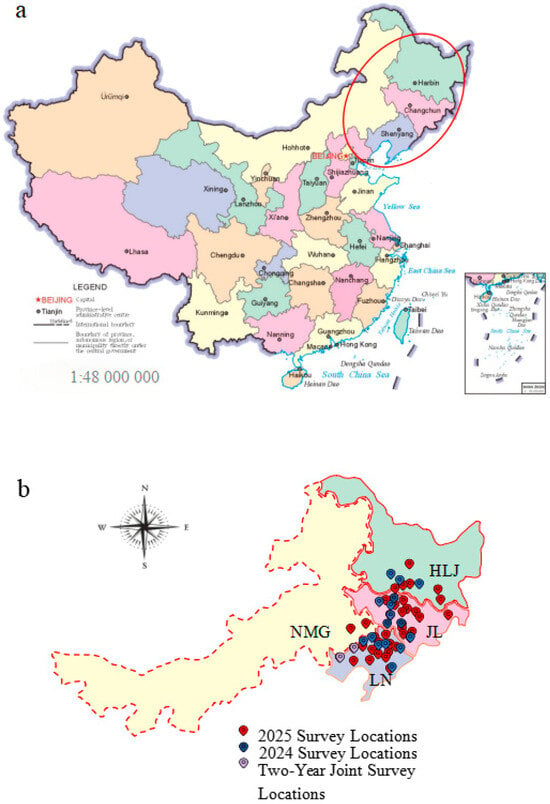

Surveys were conducted across 18 townships in Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning provinces in 2024. The scope was expanded in 2025 to cover 37 townships across Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning provinces, as well as the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. To simplify the presentation, the townships surveyed were assigned unique codes to avoid excessively lengthy listings of geographical names. Within each county (or district/city), one plot ranging from 5 to 8 hectares was randomly selected. The specific locations and geographical coordinates of these plots are provided in Figure 1 and Table 1.

Each plot was sampled using a five-point sampling method, with points located at the four corners and the center. To avoid edge effects, the five outermost rows of maize plants within each plot were excluded from sampling. Approximately 20 plants were investigated at each sampling point, ensuring a minimum of 100 plants surveyed per plot. For leaf spot diseases, lesions on the three leaves adjacent to the ear were examined [21,22].

2.2. Methods for Assessing Disease Severity

Since disease diagnosis in this survey was symptom-based and did not distinguish specific pathogens, the severity of diseases (e.g., NCLB, GLS, CLS, ME, MWS) was classified according to Table 2, while disease indices were calculated using the formulas below [23,24].

SR was assessed based on the softening of the stem tissue at the base near the soil surface. Disease incidence (%) was calculated using the formula provided. The assessment method for white spot disease followed the protocols established for gray leaf spot and northern corn leaf blight [23,24].

Disease Incidence (%) = (Number of infected plants/Total number of plants investigated) × 100

Disease Index = [∑(Number of leaves at each severity grade × Numerical value of the grade)/(Total number of leaves investigated × The highest severity value)] × 100

Table 1.

Survey location and location number.

Table 1.

Survey location and location number.

| Province | City | Township, County | Site Number * | Longitude and Latitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liaoning | Shenyang | Xiaochengzi Town, Kangping | LSY24-1 | 123.21055° E, 42.89163° N |

| Yemaotai Town, Faku | LSY24-2 | 122.88440° E, 42.32818° N | ||

| Kangping Town, Kangping | LSY25-1 | 123.37088° E, 42.74223° N | ||

| Mengjia Town, Faku | LSY25-2 | 123.43004° E, 42.54735° N | ||

| Panjiabao Town, Liaozhong | LSY25-3 | 122.71312° E,41.53120° N | ||

| Anshan | Sanglin Town, Tai’an | LAS25-1 | 122.36774° E, 41.41730° N | |

| Fushun | Dasuhe Township, Qingyuan | LFS24-1 | 124.96054° E, 41.92268° N | |

| Dagujia Town, Qingyuan | LFS24-2 | 124.84962° E, 42.37895° N | ||

| Beisanjia Town, Qingyuan | LFS25-1 | 124.71825° E, 42.04836° N | ||

| Ying’emen Town, Qingyuan | LFS25-2 | 125.09244° E, 42.17609° N | ||

| Muqi Town, Xinbin | LFS25-3 | 124.62694° E, 41.77315° N | ||

| Benxi | Xiaoshi Town, Benxi | LBX25-1 | 124.12398° E, 41.29566° N | |

| Dandong | Qingchengzi Town, Fengcheng | LDD24-1 | 123.62217° E, 40.73389° N | |

| Tongyuanpu Town, Fengcheng | LDD25-1 | 123.89957° E, 40.78595° N | ||

| Panjin | Gaoshengzi Town, Panshan | LPJ25-1 | 121.99650° E, 41.24287° N | |

| Jinzhou | Xinmin Subdistrict, Taihe | LJZ25-1 | 121.10444° E, 41.06848° N | |

| Xinzhuangzi Town, Linghai | LJZ25-2 | 121.37970° E, 41.07871° N | ||

| Fuxin | Zhanggutai Town, Fuxin | LFX24-1 | 122.48891° E, 42.71071° N | |

| Taoli Town, Fuxin | LFX25-1 | 122.36801° E, 42.40763° N | ||

| Chaoyang | Qidaoling Town, Chaoyang | LCY24-1 | 120.59289° E, 41.33547° N | |

| Liangshuihe Town, Beipiao | LCY24-2 | 120.78771° E, 41.75930° N | ||

| Qidaoling Town, Chaoyang | LCY25-1 | 120.59289° E, 41.33547° N | ||

| Liangshuihe Town, Beipiao | LCY25-2 | 120.78771° E, 41.75930° N | ||

| Jilin | Changchun | Wanbao Town, Kuancheng | JCC24-1 | 125.35452° E, 44.14364° N |

| Kaoshan Town, Nong’an | JCC24-2 | 125.65902° E, 44.77975° N | ||

| Xiangshui Town, Gongzhuling | JCC24-3 | 125.17240° E, 43.66601° N | ||

| Shanghewan Town, Jiutai | JCC25-1 | 125.83957° E, 44.15174° N | ||

| Lu Town, Shuangyang | JCC25-2 | 125.66466° E, 43.52531° N | ||

| Dehui Road, Dehui | JCC25-3 | 125.69097° E, 44.5576° N | ||

| Biangang Township, Dehui | JCC25-4 | 125.6867° E, 44.6252° N | ||

| Qingshankou Township, Nong’an | JCC25-5 | 125.59731° E, 44.85059° N | ||

| Xiangshui Town, Gongzhuling | JCC25-6 | 125.17240° E, 43.66601° N | ||

| Siping | Shiling Town, Tiedong | JSP24-1 | 124.70854° E, 43.09763° N | |

| Yingchengzi Town, Yitong | JSP24-2 | 125.51013° E, 43.18520° N | ||

| Dongyingzi Town, Yitong | JSP25-1 | 125.55156° E, 43.15795° N | ||

| Liaoyuan | Shahe Town, Dongfeng | JLY24-1 | 125.62574° E, 42.99135° N | |

| Shoushan Town, Longshan | JLY25-1 | 125.19617° E, 42.91603° N | ||

| Quantai Town, Dongliao | JLY25-2 | 124.87526° E, 42.97463° N | ||

| Santai Township, Dongfeng | JLY25-3 | 125.64119° E, 42.57649° N | ||

| Yanbian | Sandaowan Town, Yanji | JYB25-1 | 126.06152° E, 44.98842° N | |

| Songyuan | Changshan Town, Qianguo | JSY24-1 | 124.47633° E, 45.31322° N | |

| Sanchagou Town, Fuyu | JSY25-1 | 126.06152° E, 44.98842° N | ||

| Jilin City | Wanchang Town, Yongji | JJL25-1 | 125.89697° E, 43.74085° N | |

| Heilongjiang | Harbin | Minzhu Town, Daowai | HHR24-1 | 126.81672° E, 45.85549° N |

| Kangjin Street, Hulan | HHR25-1 | 126.8015° E, 46.19102° N | ||

| Mudanjiang | Dongjingcheng Town, Ning’an | HMD25-1 | 129.20941° E, 44.10302° N | |

| Wen Chun Town, Xi’an District | HMD25-2 | 129.41734° E, 44.55745° N | ||

| Suihua | Xiangyang Township, Zhaodong | HSH24-1 | 125.96181° E, 46.05113° N | |

| Qianjin Town, Hailun | HSH25-1 | 126.81922° E, 47.39938° N | ||

| Daqing | Gulong Town, Zhaoyuan | HDQ25-1 | 124.22313° E, 45.85038° N | |

| Inner Mongolia | Tongliao | Qinghe Town, Horqin | ITL25-1 | 121.94919° E, 43.71763° N |

| Mulitu Town, Horqin | ITL25-2 | 122.20765° E, 43.45362° N |

* The first character in the Site Number: “L”, “J”, “H”, and “I” represent Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang, and Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, respectively. The second and third characters represent the surveyed city. “24” or “25” represents the 2024 or 2025 survey data. The numbers following the hyphen represent the township code.

Figure 1.

Location of the study area. (a) Standard map of China with the study region highlighted by a red ellipse (base map source: Ministry of Natural Resources, China). (b) Enlarged view of the Northeast China study region, showing sampling sites for different years (see legend).

Table 2.

Disease Severity Scale.

Table 2.

Disease Severity Scale.

| Severity Grade | Symptom Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Lesions sporadically appear on the leaves, with the affected area accounting for ≤5% of the leaf surface. |

| 3 | A small number of lesions are present on the leaves, with the affected area accounting for 6–10% of the leaf surface. |

| 5 | Numerous lesions are present on the leaves, with the affected area accounting for 11–30% of the leaf surface. |

| 7 | Abundant lesions are present on the leaves, often coalescing, with the affected area accounting for 31–70% of the leaf surface. |

| 9 | The leaf is almost entirely covered by lesions, leading to leaf death. |

3. Results

3.1. Gray Leaf Spot and Northern Leaf Blight Were Prevalent Across the Corn Region of Northeast China

A systematic investigation of major maize diseases in Northeast China from 2024 to 2025 revealed that GLS and NCLB were prevalent across the region. Data from 2025 (Table 3) clearly indicated a high-severity area in the eastern mountainous regions of Liaoning Province. Specifically, multiple survey sites in Fushun City showed disease indices exceeding 60, including Beisanjia Town (LFS25-1) with a disease index of 65.26 ± 0.63, Yingemen Town (LFS25-2) at 65.16 ± 0.35, and Muqi Town (LFS25-3) at 62.18 ± 4.92. Additionally, Shoushan Town, Liaoyuan City, Jilin Province (JLY25-1) at 65.06 ± 1.50 and Shancheng Town, Meihekou City, Tonghua City, Jilin Province (JTH25-1) at 58.10 ± 4.67 were also high-severity areas. The disease index in Tongyuanpu Town, Fengcheng City, Dandong City, Liaoning Province (LDD25-1) was 58.24 ± 3.58. This high occurrence trend was consistent with the 2024 survey results (Table 3), where Dagujia Town (LFS24-1), Fushun City and Qingchengzi Town (LDD24-1), Dandong City also showed high disease levels. In contrast, western Liaoning, central Jilin, most parts of Heilongjiang Province, and Tongliao City in Inner Mongolia generally had low disease indices, mostly below 25 in both years, classifying them as minimally affected areas.

NCLB was widespread in the survey area, but the overall disease level was relatively mild. In 2025 (Table 3), areas with higher disease indices were sporadically distributed, including Xinmin Subdistrict, Taihe District, Jinzhou City, Liaoning Province (LJZ25-1) with a disease index of 58.56 ± 4.73, Liangshuihe Town, Beipiao City, Liaoning Province (LCY25-2) at 34.29 ± 0.32, and Dongyingzi Town, Yitong Manchu Autonomous County, Siping City, Jilin Province (JSP25-1) at 36.66 ± 2.19. Data from 2024 (Table 3) also recorded localized moderate to high severity. Nevertheless, over the two years, the vast majority of survey sites in the four northeastern provinces/regions had disease indices concentrated in the lower range of 11–34, not constituting widespread serious damage.

3.2. Stalk Rot, Curvularia Leaf Spot, and Maize Eyespot Occurred Locally or Were Mild

Stalk rot was generally at a low incidence level in Northeast China. 2025 data (Table 3) indicated that Liaoning Province had relatively higher incidence rates, with the highest recorded in Xinmin Subdistrict, Taihe District, Jinzhou City (LJZ25-1) at 9.23 ± 5.59%, followed by Sanglin Town, Tai’an County, Anshan City (LAS25-1) at 6.61 ± 2.41% and several townships in Fushun City with incidence rates between 5.21 ± 2.21% to 5.64 ± 1.16%. Compared with 2024 data (Table 3), higher incidence rates were observed in some locations, indicating interannual fluctuations of the disease in localized areas. However, in the vast areas of Jilin Province, Heilongjiang Province, and Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, the incidence rate of stalk rot was generally below 2% in both years, with many survey points reporting no diseased plants (incidence rate 0).

CLS occurrence was more limited and unstable. In 2025 (Table 3), significant disease levels were monitored only in a few areas of Liaoning Province, such as Taoli Town, Fuxin County (LFX25-1), with a disease index of 38.59 ± 4.54 and Panjiabao Town, Liaozhong District (LSY25-3) at 34.98 ± 3.74. Data from 2024 (Table 3) also showed this disease occurred only sporadically in Liaoning and Jilin. In the vast majority of sampling sites in Jilin, Heilongjiang, and Inner Mongolia, the disease was either undetected or had very low disease indices in both years.

ME had the most restricted occurrence range and showed significant annual variation. This disease was only recorded at individual survey points in 2024 (Table 3), primarily occurring in Heilongjiang Province. Notably, no ME was found at any sampling point during the comprehensive 2025 survey (Table 3).

Table 3.

Survey on the Occurrence of Major Maize Diseases in Northeast China in 2024 and 2025.

Table 3.

Survey on the Occurrence of Major Maize Diseases in Northeast China in 2024 and 2025.

| Province | Site Number | GLS a | NCLB a | CLS a | MWS a | ME a | SR b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liaoning | LSY24-1 | 12.83 ± 1.97 | 12.91 ± 2.46 | 0 | 14.81 ± 6.42 | 0 | 0 |

| LSY24-2 | 26.97 ± 16.73 | 13.26 ± 3.93 | 12.79 ± 4.24 | 0 | 0 | 14.26 ± 5.38 | |

| LSY25-1 | 18.07 ± 3.78 | 13.89 ± 0.88 | 11.48 ± 0.67 | 23.26 ± 4.61 | 0 | 0 | |

| LSY25-2 | 25.99 ± 0.88 | 12.26 ± 1.15 | 11.68 ± 0.99 | 25.06 ± 4.52 | 0 | 1.53 ± 0.53 | |

| LSY25-3 | 34.58 ± 1.29 | 0 | 34.98 ± 3.74 | 82.35 ± 0.83 | 0 | 4.84 ± 0.96 | |

| LAS25-1 | 33.71 ± 2.10 | 11.54 ± 0.17 | 0 | 71.42 ± 2.14 | 0 | 6.61 ± 2.41 | |

| LFS24-1 | 44.53 ± 10.52 | 24.65 ± 5.83 | 44.53 ± 10.52 | 13.58 ± 4.28 | 0 | 21.25 ± 3.77 | |

| LFS24-2 | 76.61 ± 14.57 | 41.66 ± 7.72 | 76.61 ± 14.57 | 14.81 ± 6.42 | 0 | 19.42 ± 9.14 | |

| LFS25-1 | 65.26 ± 0.63 | 13.96 ± 0.89 | 0 | 49.94 ± 10.46 | 0 | 5.21 ± 2.21 | |

| LFS25-2 | 65.16 ± 0.35 | 13.79 ± 2.37 | 0 | 43.49 ± 1.67 | 0 | 5.64 ± 1.16 | |

| LFS25-3 | 62.18 ± 4.92 | 20.37 ± 2.62 | 0 | 57.80 ± 21.87 | 0 | 2.47 ± 0.87 | |

| LBX25-1 | 34.22 ± 2.86 | 20.25 ± 1.61 | 0 | 62.58 ± 3.04 | 0 | 4.64 ± 1.96 | |

| LDD24-1 | 46.26 ± 9.47 | 33.42 ± 6.29 | 0 | 61.20 ± 5.57 | 0 | 8.27 ± 3.32 | |

| LDD25-1 | 58.24 ± 3.58 | 18.75 ± 1.88 | 0 | 86.83 ± 4.58 | 0 | 5.65 ± 3.28 | |

| LJZ25-1 | 26.68 ± 4.02 | 58.56 ± 4.73 | 0 | 14.55 ± 0.37 | 0 | 9.23 ± 5.59 | |

| LJZ25-2 | 39.27 ± 3.20 | 21.69 ± 3.16 | 12.73 ± 1.31 | 11.83 ± 0.15 | 0 | 1.10 ± 0.96 | |

| LFX24-1 | 33.42 ± 3.19 | 37.82 ± 4.58 | 33.42 ± 3.19 | 0 | 0 | 12.95 ± 3.25 | |

| LFX25-1 | 18.52 ± 12.83 | 12.07 ± 0.54 | 38.59 ± 4.54 | 11.73 ± 1.31 | 0 | 3.37 ± 1.23 | |

| LPJ25-1 | 12.92 ± 1.83 | 15.28 ± 0.95 | 11.96 ± 0.75 | 79.70 ± 6.08 | 0 | 2.27 ± 1.97 | |

| LTL25-1 | 12.87 ± 0.26 | 12.70 ± 2.24 | 0 | 12.62 ± 0.04 | 0 | 3.54 ± 2.17 | |

| LCY24-1 | 66.96 ± 8.84 | 61.75 ± 3.65 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.82 ± 3.22 | |

| LCY24-2 | 15.69 ± 4.59 | 51.12 ± 4.54 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7.26 ± 3.30 | |

| LCY25-1 | 14.57 ± 1.82 | 14.51 ± 1.73 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.06 ± 0.03 | |

| LCY25-2 | 0 | 34.29 ± 0.32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.78 ± 1.72 | |

| Jilin | JCC24-1 | 12.13 ± 2.15 | 13.26 ± 1.29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.95 ± 2.05 |

| JCC24-2 | 24.85 ± 4.85 | 15.51 ± 6.67 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.00 ± 2.25 | |

| JCC24-3 | 27.81 ± 6.65 | 15.18 ± 6.76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8.74 ± 3.66 | |

| JCC25-1 | 13.12 ± 1.03 | 13.83 ± 2.38 | 0 | 16.67 ± 7.86 | 0 | 1.50 ± 0.71 | |

| JCC25-2 | 52.76 ± 1.07 | 0 | 12.50 ± 1.96 | 11.90 ± 1.59 | 0 | 0.95 ± 0.05 | |

| JCC25-3 | 12.36 ± 0.20 | 21.11 ± 1.57 | 0 | 16.67 ± 6.42 | 0 | 0 | |

| JCC25-4 | 11.79 ± 0.62 | 20.37 ± 2.62 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.49 ± 1.16 | |

| JCC25-5 | 13.34 ± 0.47 | 14.81 ± 6.42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.44 ± 1.26 | |

| JCC25-6 | 13.16 ± 7.56 | 12.85 ± 1.51 | 0 | 18.26 ± 5.82 | 0 | 1.38 ± 1.12 | |

| JJL25-1 | 14.55 ± 3.22 | 13.52 ± 4.50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.42 ± 1.22 | |

| JSP24-1 | 46.20 ± 12.93 | 16.01 ± 6.17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18.62 ± 3.29 | |

| JSP24-2 | 64.52 ± 6.87 | 19.44 ± 4.11 | 0 | 12.96 ± 3.21 | 0 | 20.50 ± 2.22 | |

| JSP25-1 | 18.92 ± 1.07 | 36.66 ± 2.19 | 11.36 ± 0.05 | 37.47 ± 0.89 | 0 | 1.67 ± 1.52 | |

| JLY24-1 | 57.46 ± 7.12 | 48.26 ± 14.29 | 16.67 ± 5.56 | 0 | 0 | 4.56 ± 2.00 | |

| JLY25-1 | 65.06 ± 1.50 | 14.20 ± 0.87 | 0 | 20.74 ± 7.33 | 0 | 1.12 ± 0.92 | |

| JLY25-2 | 44.56 ± 7.70 | 16.11 ± 0.79 | 13.73 ± 0.22 | 64.81 ± 7.86 | 0 | 0 | |

| JLY25-3 | 48.97 ± 0.11 | 48.97 ± 0.11 | 0 | 55.44 ± 8.01 | 0 | 0 | |

| JTH25-1 | 58.10 ± 4.67 | 30.17 ± 0.59 | 0 | 66.06 ± 16.67 | 0 | 1.83 ± 0.81 | |

| JYB25-1 | 14.56 ± 3.89 | 13.46 ± 3.12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| JSY24-1 | 16.92 ± 9.02 | 12.26 ± 5.28 | 0 | 0 | 13.69 ± 6.20 | 7.28 ± 1.51 | |

| JSY25-1 | 22.59 ± 6.32 | 17.13 ± 3.27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Heilongjiang | HHR24-1 | 14.13 ± 4.05 | 38.44 ± 10.59 | 0 | 0 | 22.27 ± 6.20 | 0 |

| HHR25-1 | 20.37 ± 5.62 | 14.81 ± 6.42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.50 ± 1.29 | |

| HMD25-1 | 17.87 ± 4.62 | 12.93 ± 3.97 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| HMD25-2 | 19.52 ± 6.55 | 13.12 ± 7.28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| HDQ25-1 | 14.42 ± 3.13 | 13.39 ± 2.58 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.54 ± 1.13 | |

| HSH24-1 | 27.09 ± 7.24 | 34.11 ± 7.17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.69 ± 3.38 | |

| HSH25-1 | 12.91 ± 1.77 | 13.28 ± 1.65 | 0 | 0 | 27.16 ± 7.17 | 0 | |

| Inner Mongolia | ITL25-1 | 13.11 ± 2.52 | 11.24 ± 0.22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.54 ± 1.10 |

| ITL25-2 | 12.65 ± 1.81 | 12.70 ± 2.24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.81 ± 1.34 |

a Disease severity of Gray leaf spot (GLS), Northern corn leaf blight (NCLB), Maize white spot (MWS), and Curvularia leaf spot (CLS) was evaluated using the disease index. b The incidence rate (%) was used to assess the occurrence of Stalk rot (SR). “0” indicates that the respective disease was not observed at the survey site.

3.3. White Spot Emerged as a Severe and Established New Disease in Parts of Northeast China

Maize white spot (MWS) showed a severe and persistent occurrence in some areas of Northeast China. The 2025 survey results (Table 3) revealed multiple extremely high-incidence centers in Liaoning Province, including Tongyuanpu Town, Fengcheng City, Dandong City (LDD25-1), with a disease index of 86.83 ± 4.58, Panjiabao Town, Liaozhong District, Shenyang City (LSY25-3) at 82.35 ± 0.83, and Gaoshengzi Town, Panshan County, Panjin City (LPJ25-1) at 79.70 ± 6.08.

Simultaneously, distinct occurrence areas were established in the southern and central parts of Jilin Province. High disease indices were recorded in Quantai Town, Dongliao County, Liaoyuan City (JLY25-2) at 64.81 ± 7.86, Shancheng Town, Meihekou City, Tonghua City (JTH25-1) at 66.06 ± 16.67, and Santai Township, Dongfeng County (JLY25-3) at 55.44 ± 8.01. The disease also showed a high incidence rate in Xiangshui Town, Gongzhuling City, Jilin Province.

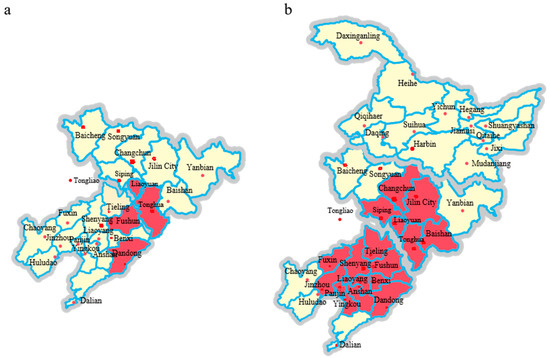

Integrating data from both years (Table 3, Figure 2), white spot disease was already observed at a relatively severe level in 2024 in some locations (Figure 2a). By 2025, its range further expanded, with continued and more severe occurrences in multiple counties and cities across Liaoning and Jilin provinces (Figure 2b). This continuous, high-level disease manifestation, combined with its clear and increasingly stable geographical distribution pattern, demonstrates that white spot disease has successfully become established in the corn production areas of Northeast China, emerging as a new disease requiring close attention.

Figure 2.

Spatiotemporal survey of Maize White Spot (MWS) occurrence across prefecture-level cities in Northeast China. Red shading on the map denotes cities where the disease was confirmed through field survey in at least one township during the respective year. Panel (a) shows the surveyed distribution for the year 2024, while panel (b) presents the surveyed distribution for the year 2025, illustrating the interannual variation in the geographical extent of MWS infections.

4. Discussion

Our two-year comprehensive survey provides a critical snapshot of the current status and evolving threats posed by maize diseases in Northeast China, one of the nation’s most vital grain production bases. The most salient finding of this study is the confirmed establishment and severe manifestation of maize white spot (MWS) as a devastating new disease within the region. The rapid northward expansion of MWS from its initial report in Yunnan Province in 2020 [16] to its current widespread and severe occurrence in multiple provinces by 2025, with disease indices exceeding 80 at several locations (e.g., LDD25-1, LSY25-3), underscores its aggressive adaptability and significant yield threat. Concurrently, our results confirm that gray leaf spot (GLS) and northern corn leaf blight (NCLB) remain persistently prevalent, forming the background of foliar disease pressure, with clearly identified high-severity areas concentrated in the eastern mountainous areas of Liaoning and Jilin provinces. In contrast, other diseases such as stalk rot (SR) and Curvularia leaf spot (CLS) currently occur only locally or mildly, exhibiting considerable interannual fluctuation, while maize eyespot (ME) appears sporadic and unstable. This clear demarcation between established, emerging, and minor diseases offers strategic prioritization for future management efforts.

The establishment of MWS in Northeast China marks a significant shift in the regional disease landscape. The rapid epidemic of this disease is hypothesized to be closely linked to the anomalous summer climatic conditions observed in Northeast China in recent years. Official monitoring and forecasts indicate that the summer seasons of the survey years (2024–2025) in Northeast China, particularly in Liaoning and Jilin, were characterized by unusually “warm and humid” weather. For instance, forecasts predicted precipitation to be 30–40% above normal and temperatures 0.5–1.0 °C higher in southeastern Liaoning during midsummer 2025, while Jilin Province also anticipated above-average precipitation and slightly higher temperatures during the critical disease development period in August [25,26]. This pattern of high temperature, high humidity, and frequent rainfall is highly conducive to the occurrence and spread of maize foliar diseases. Pathogenicity studies indicate that the optimal growth temperature for primary MWS pathogens in the region, such as Epicoccum latusicollum, is 25–28 °C, aligning with summer high-temperature conditions [18]. Therefore, although this survey did not conduct a quantitative analysis of field microclimate data, it is reasonable to speculate that the anomalous “warm and humid” climatic background present in Northeast China during the summers of 2024–2025 likely created highly favorable conditions for the infection, reproduction, and dissemination of MWS pathogens, collectively contributing to the severe epidemic status documented in this investigation. Our survey documented severe outbreaks across multiple counties in Liaoning and Jilin, with disease indices showing an increasing trend during the survey period. The geographical stability of these outbreaks indicates MWS is no longer an incidental pathogen but has adapted to local agroecological conditions. Although previous studies suggested a northward expansion trend and reported sporadic occurrences in other parts of China [16,17,18], this study is the first to confirm its widespread establishment and epidemic status in the Northeast maize production area through systematic regional investigation. The etiology of MWS in China demonstrates considerable complexity and regional variation. While Phaeosphaeria maydis and Pantoea ananatis have been identified as primary pathogens in international contexts, recent Chinese investigations have established Epicoccum species (including E. latusicollum and E. sorghinum) and Setophoma zeae-maydis as predominant pathogens in Northeast China [18]. This dynamic and evolving pathogen profile emphasizes the continuously changing nature of disease threats and the associated challenges for accurate diagnosis and implementation of effective management strategies.

Survey data from 2024 to 2025 reveal a significant shift in the hierarchy of major foliar diseases in Northeast China. Historically, NCLB has long been regarded as the most prevalent foliar disease in this region [27]. However, due to persistent efforts in plant protection and a strategic shift in varietal deployment towards NCLB resistance, the severity of NCLB has shown a consistent downward trend in recent years. In contrast, GLS, previously not a dominant disease, has seen its pathogen population dynamics evolve [6,7]. Although both GLS and NCLB were prevalent across the region, GLS has emerged as the more severe and agronomically significant foliar pathogen, with its overall impact now surpassing that of NCLB. This shift can be attributed to a combination of factors: Specifically, the increasing prevalence of conducive climatic conditions—According to the National Climate Center’s monitoring reports, the summer (June-August) of 2024 in Northeast China recorded an average temperature 0.8 °C higher and precipitation 12% more than the 1991–2020 climatological average, with Jilin and eastern Liaoning experiencing particularly significant increases in both parameters. The 2025 summer continued this trend with temperatures 0.5–1.0 °C above average and precipitation 10–15% above normal in the key maize production areas of Liaoning and Jilin [28,29]—which favor GLS development [30], coupled with a historical lack of emphasis on GLS resistance in mainstream varietal selection. The disease pressure exerted by GLS was substantially higher, clearly evidenced by the establishment of multiple, stable high-incidence zones in the eastern mountainous areas of Liaoning and Jilin provinces, where disease indices consistently exceeded 60 at several sites during both survey years. In contrast, although NCLB was geographically widespread, its overall severity was much milder. The vast majority of surveyed sites recorded NCLB disease indices in the relatively low range of 11–34, with only a few sporadic locations reaching higher levels. The finding that GLS now poses a greater threat than NCLB revises earlier perceptions, which regarded NCLB as the predominant foliar disease in Northeast China [30]. This shift may be related to pathogen population dynamics and varietal resistance deployment. The progressive northward expansion and establishment of C. zeina, a causal agent of GLS, in Northeast China in recent years may be a key driver behind the increasing severity of GLS [6,7]. Concurrently, currently widely planted maize hybrids may possess effective resistance against NCLB but potentially lack robust resistance against emerging strains of GLS, which could also contribute to this changing disease dynamic.

Studies indicate that the severity of gray leaf spot is closely associated with temperature and humidity, with warmer and more humid conditions favoring disease development [30]. Specifically, the precipitation and average temperatures in Liaoning and Jilin are higher than those in Heilongjiang, which is primarily due to geographical factors. Heilongjiang Province is located at a higher latitude, resulting in relatively lower temperatures, and its average annual precipitation is also lower than that of Liaoning and Jilin provinces [31]. Similarly, the absence of white spots in Heilongjiang during this survey could also be attributed to climatic factors, as well as its greater distance from the hypothesized initial disease dissemination center—the Dandong area. It should be noted, however, that this remains a tentative hypothesis. Furthermore, the predominantly mountainous topography of the southeastern region—such as the Fushun area, where gray leaf spot has been consistently severe over two consecutive years—contributes to large diurnal temperature variations. This climatic feature promotes dew formation on maize leaves, creating localized high-humidity microenvironments that facilitate pathogen infection and limit the dispersal of spores and moisture, thereby exacerbating the incidence of gray leaf spot.

Regarding SR, our survey revealed its widespread presence across maize production areas in the three northeastern provinces, with average incidence rates higher in Liaoning and Jilin than in Heilongjiang. However, the incidence is generally low. Data from the 2024–2025 surveys show incidence rates below 10% across all regions. Compared to previous surveys [20,32,33], the current severity of SR has decreased significantly, which can be largely attributed to the nearly universal adoption of seed coating agents in the region, a practice that has become standard for almost all sown seeds and effectively suppresses early-stage infection. Similarly, the occurrence of CLS and ME in Northeast China exhibits localized and intermittent characteristics. Although CLS caused a large-scale epidemic in the mid-1990s in the maize-producing regions of Northeast and North China, leading to significant yield losses, it subsequently became a common disease, with recent trends indicating only localized occurrence [34]. ME shows comparable characteristics, capable of causing significant yield losses under favorable conditions but occurring only locally in recent years without developing into large-scale epidemics [35]. This study’s survey found that both diseases currently exhibit only localized occurrence in Northeast China, with limited severity. Nevertheless, such locally prevalent diseases still require continuous monitoring, particularly under conditions of suitable climate, widespread continuous cropping, and the continued cultivation of susceptible varieties.

This study has several limitations. First, with respect to spatial representativeness, although the survey covered dozens of townships across Northeast China over two consecutive years, the density and distribution of sampling points relative to the vast maize planting area could be further optimized. Establishing a denser and more spatially uniform sampling network would contribute to a more precise characterization of the fine-scale distribution patterns of diseases, particularly in marginal or transitional zones of disease occurrence. Second, the accessibility of field data posed another major constraint. As the surveys were conducted in farmers’ fields, it was not feasible to systematically obtain detailed agronomic information for each sampling point, such as the maize variety planted, exact sowing dates, and water and fertilizer management practices. This information gap hindered the analysis of the effects of varietal resistance on the severity of major diseases such as gray leaf spot (GLS) and maize white spot (MWS), and complicated the accurate assessment of the potential threat posed by stalk rot (SR) and its relationship with varietal resistance. Consequently, this limitation restricted our ability to provide precise, location-specific recommendations for the selection of resistant varieties. Furthermore, the disease assessment in this study relied entirely on the experiential diagnosis of field symptoms, without employing more accurate pathogen detection methods such as molecular assays. Given that certain diseases can be caused by multiple pathogens, the current approach did not allow for further differentiation or evaluation of the dominant pathogenic species in the region and their respective impacts, which may introduce some uncertainty in disease characterization. Nevertheless, it is important to emphasize that, under the existing conditions, the extensive primary data collected still provide evidence for the establishment and severe impact of maize white spot (MWS) in the region, the dominant role of gray leaf spot (GLS) among foliar diseases, and the widespread distribution of southern rust (SR). These core findings offer critical scientific evidence and clear research direction for subsequent work on pathogen identification, evaluation of varietal resistance, and the development of regional disease management strategies.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our systematic survey, based on the assessment of disease symptoms, delineates a dynamic and evolving maize disease profile in Northeast China. The most critical finding is the confirmed establishment of maize white spot (MWS) as a devastating new disease, posing a significant and immediate threat to regional maize production. Concurrently, gray leaf spot (GLS) has solidified its status as the predominant foliar disease, exceeding northern corn leaf blight (NCLB) in severity and impact within the region. While other diseases like stalk rot (SR), Curvularia leaf spot (CLS), and Maize eyespot (ME) currently persist at lower levels, their localized occurrence warrants continued monitoring. This study provides a clear hierarchy of disease priorities, underscoring the urgent need for focused research on the pathogenesis and control of MWS and GLS. Future efforts should be directed toward developing resistant varieties, optimizing cultural practices, and formulating targeted management strategies against these key pathogens to safeguard the productivity and sustainability of maize cultivation in this vital agricultural region.

Author Contributions

B.L. and D.L.: formal analysis, writing—original draft. L.H. and H.D.: conceptualization. K.L. and L.C.: methodology, formal analysis, investigation. L.W.: methodology, formal analysis, data curation. B.L. and P.W.: writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Basic Scientific Research Foundation of Liaoning Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Doctoral Startup Project, Grant No. 2025BS1711), the Innovation Fund of Institute of Plant Protection, Liaoning Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Grant No. 2025ZBJC003), and the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (Grant No. 2025-BS-0931).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- National Bureau of Statistics of China (NSBC). China Statistics Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, H.; Tang, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, F.; Yang, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, D.; Hao, Z.; Weng, J.; et al. Effect of Five Modified Mass Selection Cycles on Combining Ability in Two Chinese Maize Populations. Euphytica 2020, 216, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Groenewald, M.; Caldwell, P.; Braun, U.; Harrington, T.C. Species of Cercospora Associated with Grey Leaf Spot of Maize. Stud. Mycol. 2006, 55, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.J.; Xu, X.D. First Report of Gray Leaf Spot of Maize Caused by Cercospora zeina in China. Plant Dis. 2013, 97, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y. The Research Progress, Problem and Prospect of Gray Leaf Spot in Maize. Maize Sci. 2005, 13, 117–121. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, X.; Duan, C.; Long, S.; Li, X.; Li, H.; He, Y.; Jin, Q.; Wu, X.; Song, F. Occurrence Status and Future Spreading Areas of Maize Gray Leaf Spot in China. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2015, 48, 3612–3626. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Duan, C.; Zhao, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Yang, Z.; Wang, X. Dispersal Routes of Cercospora zeina Causing Maize Gray Leaf Spot in China. J. Integr. Agric. 2022, 21, 2943–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohithaswa, H.C.; Balasundara, D.C.; Mallikarjuna, M.G.; Sowmya, M.S.; Mallikarjuna, N.; Kulkarni, R.S.; Pandravada, A.S.; Bhatia, B.S. Experimental Evaluation of Effectiveness of Genomic Selection for Resistance to Northern Corn Leaf Blight in Maize. Plants 2025, 14, 3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Aroca, T.; Doyle, V.; Singh, R.; Price, T.; Collins, K. First Report of Curvularia Leaf Spot of Corn, Caused by Curvularia lunata, in the United States. Plant Health Prog. 2018, 19, 140–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, F.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Gao, W.; Huo, N.; Jin, X. Curvularia leaf spot of maize: Pathogens and varietal resistance. Acta Phytopathol. Sin. 1998, 28, 123–129. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, F.; Zhao, J.; Sun, J.; Fu, D.; Liu, K.; Chen, N.; Li, G.; Xiao, S.; Xue, C. Virulence, Molecular Diversity, and Mating Type of Curvularia lunata in China. Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 1728–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Liu, S.; Shi, J.; Guo, N.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J. A new Curvularia lunata variety discovered in Huanghuaihai Region in China. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arny, D.; Smalley, E.; Ullstrup, A.; Worf, G.; Ahrens, R. Eyespot of maize, a disease new to North America. Phytopathology 1971, 61, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, D.S.; Wise, K.A.; Sisson, A.J.; Allen, T.W.; Bergstrom, G.C.; Bosley, D.B.; Bradley, C.A.; Broders, K.D.; Byamukama, E.; Chilvers, M.I.; et al. Corn yield loss estimates due to diseases in the United States and Ontario, Canada from 2012 to 2015. Plant Health Prog. 2016, 17, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paccola-Meirelles, L.D.; Meirelles, W.F.; Parentoni, S.N.; Marriel, I.E.; Ferreira, A.S.; Casela, C.R. Reaction of maize inbred lines to the bacterium Pantoea ananas isolated from Phaeosphaeria leaf spot lesions. Crop Breed. Appl. Biotechnol. 2002, 2, 587–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Zou, C.; Zhang, Z.; Duan, L.; Huang, J.; Wang, L.; Xiao, W.; Li, W.; Yang, X.; Xiang, Y.; et al. First Report of Maize White Spot Disease Caused by Pantoea ananatis in China. Plant Dis. 2022, 107, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; He, Y.H.; Cun, H.C.; Liu, Y.; He, P.; He, P.; Wu, Y.; He, Y.; Yang, Z. Sensitivity of Pathogens Causing Maize White Spot Disease to Different Fungicides in Three Regions. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2025, 53, 165–169. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xue, C.S.; Jia, J.Q.; Li, X.L.; Li, W.; Xiao, S. Research Advances in Maize White Spot Disease. Acta Phytopathol. Sin. 2025, 55, 1001–1012. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Qu, Q.; Cao, Z.; Guo, Z.; Jia, H.; Liu, N.; Wang, Y.; Dong, J. The Relationship Analysis on Corn Stalk Rot and Ear Rot According to Fusarium Species and Fumonisin Contamination in Kernels. Toxins 2019, 11, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Xu, G.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Lu, R.; Li, C.; Wang, H.; Li, F. Analysis of the resistance to stalk rot and yield loss evaluation of 25 maize varieties. J. Maize Sci. 2015, 23, 12–17. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Saravanakumar, K.; Xia, H.; Gao, J.; Fu, K.; Sun, J.; Dou, K.; Chen, J. Occurrence and virulence of Fusarium spp. associated with stalk rot of maize in North-East China. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2017, 98, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Li, R.; Guo, C.; Pang, M.; Liu, Y.; Dong, J. Natural incidence of Fusarium species and fumonisins B1 and B2 associated with maize kernels from nine provinces in China in 2012. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2015, 32, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.L.; Madden, L.V. Introduction to Plant Disease Epidemiology; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Z.D. Methods in Plant Pathology, 3rd ed.; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 1998; pp. 50–55. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liaoning Provincial Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. Climatic Trend Prediction for Midsummer 2025 in Liaoning Province and Its Agricultural Impact Assessment. 2025. Available online: http://nync.ln.gov.cn/ (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Jilin Provincial Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. Agricultural Meteorological Monthly Report for August 2025 in Jilin Province. 2025. Available online: http://agri.jl.gov.cn/ (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Zhang, X.; Yang, S.Y.; Ren, B.Y.; Li, J.; Guo, J.J.; Wang, L.; Li, C.Y. Analysis on the occurrence, damage and control of maize diseases, pests and weeds in Northeast China from 2008 to 2019. China Plant Prot. 2021, 41, 83–90. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- National Climate Center, China Meteorological Administration. Climate Monitoring Bulletin of China (Summer 2024). 2024. Available online: https://www.ncc-cma.net/channel/news/newsid/100659 (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- National Climate Center, China Meteorological Administration. Climate Monitoring Bulletin of China (Summer 2025). 2025. Available online: http://cmdp.ncc-cma.net/cn/monitoring.htm (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Gao, Z.G.; Chen, J.; Xue, C.S.; Li, D.H.; Bi, C.W. Study on the occurrence, epidemiology and pathogenic conditions of gray leaf spot in maize. J. Shenyang Agric. Univ. 2000, 31, 460–464. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.C. Study on the variation trend of precipitation in Northeast China in recent 60 years. Northwest Hydropower 2022, 4, 12–15. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Su, Q.F.; Zhang, W.; Song, S.Y.; Jin, Q.M.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.F.; Sui, J. Investigation of major maize diseases and prediction of their occurrence trends in Jilin Province in 2007. J. Maize Sci 2008, 16, 135–137. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.J.; Chen, G.Q.; Xue, L.; Lu, H.H.; Shi, M.L.; Huang, X.L.; Hao, D.R.; Mao, Y.X. Research progress on maize stalk rot. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2013, 41, 8557–8559. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, T.C.; Wang, W.S.; Xu, X.D.; Liu, J.G.; Lv, G.Z.; Bai, J.K. Curvularia Leaf Spot of Corn in Liaoning Province. Liaoning Agric. Sci. 1996, 6, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N.; Xiao, S.; Sun, J.; He, L.; Liu, M.; Gao, W.; Xu, J.; Wang, H.; Huang, S.; Xue, C. Virulence and Molecular Diversity in the Kabatiella zeae Population Causing Maize Eyespot in China. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.