Abstract

Delayed sowing has become a key constraint on winter wheat production in the Guanzhong Plain, Shaanxi Province, China, due to the widespread adoption of late-maturing maize and the delayed harvest of preceding crops. A two-year field experiment was conducted on the Guanzhong Plain to elucidate the physiological mechanisms behind yield reduction under delayed sowing and to explore potential mitigation strategies. The study examined the effects of sowing time (normal, 10-day delay, and 20-day delay) and plastic film mulching on yield components, crop development, and water and nitrogen uptake and use in winter wheat. Compared to normal sowing, delayed sowing significantly reduced grain yield (7.64–17.19%), spike number (11.65–21.3%), 1000-grain weight (5.2–9.05%), growth duration (7–16 d), dry matter accumulation (21.79–58.07%), and partial factor productivity of nitrogen fertilizer (7.64–17.2%). Late sowing slowed overall growth and development, shortened the growth cycle, and suppressed root system expansion and plant height, particularly under the 20-day delay. However, plastic film mulching under delayed sowing improved seedling emergence, root growth, tiller number (8.42–51.23%), water use efficiency (10.15–18.15%), and nitrogen productivity, thereby mitigating the adverse effects of delayed sowing on resource capture. Mulching enabled wheat sown with a 10-day delay to achieve yields comparable to normal-sown crops and alleviated 9.1–10.3% of the yield loss under a 20-day delay, although it did not fully restore yields to the non-delayed level. These findings provide practical insights for managing winter wheat under delayed sowing conditions.

1. Introduction

Common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is a globally cultivated staple crop, grown on approximately 215 million hectares and serving as a primary caloric source for over 35% of the global population [1]. With a nutritional value of 1320 kilocalories per 100 g of dry weight, wheat contributes about 20% of the world’s dietary calories and protein [2]. China is a major wheat producer, accounting for roughly 17% of global production and producing 136 million tons annually. Within China, winter wheat (T. aestivum subsp. aestivum) dominates, contributing 94% of the nation’s total wheat yield [3].

In the Guanzhong Plain, the typical intensive farming system involves annual wheat-maize rotation [4]. The prevalent delay in winter wheat sowing is driven by multiple interrelated factors. To maximize maize productivity in double-cropping systems, farmers often delay maize harvest and use late-maturing varieties, thereby shortening the critical window for timely wheat sowing [5]. This challenge is further exacerbated by climate-related factors, such as prolonged, heavy pre-sowing rainfall that leads to excessive soil moisture and waterlogging, impeding field preparation and sowing operations. Broader trends, including global warming and socioeconomic constraints such as labor shortages and limited access to machinery, also contribute to delayed sowing [6]. Consequently, late-sown winter wheat is increasingly prevalent [7,8].

Delayed sowing reduces tiller formation due to lower early-season temperatures and exposes crops to heat stress during reproductive development, leading to floral organ abortion and shortening the grain-filling period, ultimately reducing yield [9]. It also disrupts nitrogen metabolism, which is crucial for yield formation. A shortened and thermally suboptimal vegetative phase limits root development, thereby impairing soil nitrogen acquisition [10,11]. Later reproductive stages often coincide with terminal heat stress, inhibiting key enzymes involved in nitrogen assimilation and remobilization, such as nitrate reductase and glutamine synthetase [12]. This combination of reduced nitrogen uptake and compromised internal N-use efficiency substantially limits grain nitrogen accumulation [13], forming the physiological basis for yield loss under late sowing. Understanding these integrated constraints, particularly those related to nitrogen metabolism, is essential for developing strategies to stabilize yields under delayed sowing.

Plastic film mulching is a core agronomic practice that regulates soil temperature and moisture. It improves the soil’s hydrothermal environment, enhances surface soil temperature and moisture retention [14,15,16], ensures better soil water supply during critical growth stages [17], promotes nutrient cycling, improves the microenvironment, increases seedling establishment rates, and ultimately enhances plant growth [18,19,20] and grain yield [21]. However, most existing studies have focused on the effects of mulching under normal sowing conditions. The potential of mulching to counteract the adverse effects of delayed sowing—through enhanced thermal time accumulation and improved nitrogen use efficiency—remains underexplored. The effects of mulching on nitrogen uptake, root system traits, and crop phenology in delayed-sown winter wheat remain largely unquantified in the literature. Importantly, interactions between sowing time and mulching may reshape resource allocation during key growth stages, offering a novel approach to managing climate-induced yield variability.

This study presents a two-year field experiment designed to evaluate the effects of sowing date (normal, 10-day delay, and 20-day delay) and plastic film mulching on winter wheat yield. We hypothesize that (1) delayed sowing shortens the growing season, disrupts nitrogen and water uptake and utilization, and reduces yield, and (2) plastic film mulching mitigates these effects by accelerating early development and modifying growth stage distribution. The specific objectives of this study were to (1) identify and quantify the key factors responsible for yield loss under delayed sowing conditions, (2) evaluate the effects of plastic film mulching on crop phenology, water use efficiency, and nitrogen utilization, and (3) propose evidence-based cultivation strategies for managing late-sown wheat. This study addresses the knowledge gap regarding the quantitative mechanisms by which mulching mitigates the negative effects of delayed sowing, aiming to stabilize wheat yields within the regionally constrained sowing window established by the preceding maize crop.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

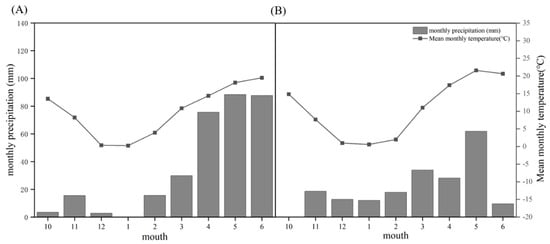

The field experiment was conducted from 2022 to 2024 at the Caoxinzhuang Experimental Farm (34°31′ N, 108°10′ E) in Yangling District, Xianyang City, Shaanxi Province, China. The site—affiliated with Northwest A&F University—has an average elevation of 530 m, an annual sunshine duration of 2163.8 h, a frost-free period of approximately 211 days, a mean annual temperature of 12.9 °C, annual evaporation of 1400 mm, and average annual precipitation of 637.6 mm. The soil type is Lou soil (typical cultivated loessial soil), with the topsoil (0–20 cm) characterized by a pH of 7.7, organic matter content of 14.1 g/kg, total nitrogen of 1.2 g/kg, available phosphorus of 17.2 mg/kg, and available potassium of 165.3 mg/kg. Monthly mean temperature and precipitation data for the winter wheat growing seasons (October to June in 2022–2023 and 2023–2024) are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Monthly mean rainfall and mean temperatures during the (A) 2022–2023 and (B) 2023–2024 winter wheat growing seasons at the experimental site.

2.2. Experimental Design

The experiment evaluated five treatment combinations involving sowing dates and mulching practices, with the winter wheat cultivar ‘Xiaoyan 22’ (weak winter type) sown at a density of 3.5 million seeds per hectare. The treatments were as follows:

- (1)

- CK (Control): Normal sowing date (20 October) without plastic film mulching (bare soil).

- (2)

- T1: First delayed sowing date (30 October) without mulching.

- (3)

- T1F: First delayed sowing date (30 October) with plastic film mulching (F).

- (4)

- T2: Second delayed sowing date (9 November) without mulching.

- (5)

- T2F: Second delayed sowing date (9 November) with plastic film mulching (F).

These five treatments were arranged in a randomized complete block design and replicated three times, resulting in a total of 15 experimental plots (Table 1). Notably, the normal sowing date (20 October) was only tested under the non-mulched condition.

Table 1.

Experimental treatments.

Each plot measured 24 m2 (4 m × 6 m). Bare soil plots were sown using a flat furrow method with 25 cm row spacing. Mulched plots had a ridge-furrow system, with 25 cm-wide ridges and furrows and 15 cm ridge height. Transparent plastic film (low-density polyethylene, LDPE; non-degradable; 80 cm wide, 0.01 mm thickness) covered ridges and remained in place throughout the growing season. Two rows were sown per furrow at 25 cm row spacing, with seeds manually dibbled at 4–5 cm depth. Pre-sowing fertilization included 220 kg N/ha, 90 kg P/ha, and 120 kg K/ha. All fertilizer ws applied pre-sowing. All field management followed local high-yield practices.

2.3. Measurements and Calculations

2.3.1. Phenological Development

Key growth stages (sowing, emergence, jointing, heading, flowering, and maturity) were recorded in accordance with the GB/T 37804-2019 [22] issued by the National Standardization Administration. A developmental stage was considered reached when more than 50% of the plants in the field had reached that stage.

2.3.2. Stem and Tiller Dynamics

Stem and tiller density were recorded at overwintering, stem elongation, jointing, flowering, and maturity stages. Uniform sections within each plot were selected, and tiller counts were recorded from three 1 m row sections per plot.

2.3.3. Plant Height

Plant height was measured at stem elongation, jointing, flowering, grain filling, and maturity stages. Five uniformly growing main stems per plot were selected to measure their total aboveground lengths (excluding awns). The average height per plot was used for analysis.

2.3.4. Aboveground Dry Biomass Accumulation

At stem elongation, jointing, flowering, and maturity stages, aboveground biomass was sampled from three 1 m row sections per plot. Roots were carefully removed, retaining only aboveground material. Samples were initially de-enzymed at 105 °C for 30 min, then oven-dried at 80 °C to constant weight. Aboveground dry matter accumulation per unit area was calculated from these measurements.

2.3.5. Soil Temperature

Soil temperatures at 5 cm, 10 cm, and 15 cm depths were recorded using a digital probe thermometer (RC-4HC, Jiangsu Jingchuang Electric Co., Ltd., Xuzhou, China, −20–40 °C range, ±0.5 °C accuracy) at overwintering, stem elongation, jointing, and flowering stages. Measurements were taken on three consecutive days at three times daily (8:00, 12:00, and 18:00) from three points per plot. Stage-specific mean values were calculated from daily averages.

2.3.6. Soil Moisture Content

Soil samples were collected pre-sowing and post-harvest from between rows at 20 cm intervals to a depth of 1 m using a hand-operated soil auger (40 mm diameter; Yangling Zhizao Shuibao Instrument Equipment Processing Factory, Yangling, China). Samples were immediately placed in pre-weighed aluminum boxes (40 mm diameter × 25 mm height) to prevent moisture loss. Gravimetric soil moisture content was determined using the standard oven-drying method [23,24]. Fresh mass was recorded, samples were oven-dried at 105 °C to constant weight (typically 24–48 h), and dry mass was recorded. Moisture content (W, %) was calculated as:

where M1 is wet soil mass (g), M2 is dry soil mass (g), and M is the mass of aluminum box (g).

W = [(M1 − M2)/(M2 − M)] × 100%

Water use efficiency (WUE, kg/ha/mm) was calculated as [25]:

where GY is grain yield (kg/ha), and ETa is crop evapotranspiration (mm).

WUE = GY/ETa

Crop evapotranspiration during the growing season (ETa) was estimated via soil water balance [26]:

where U is upward groundwater recharge (mm), I is irrigation amount (mm), P is effective precipitation (mm) (Figure 1), F is deep percolation loss (mm), R is surface runoff (mm), and ΔSW is the change in soil water storage (mm). Based on site-specific conditions (flat terrain, negligible R; deep groundwater table, negligible U; no irrigation, I = 0; soil profile monitored to 1 m, which is shallower than the observed maximum infiltration depth of ≤2 m, negligible F; [26,27], the equation simplifies to:

ETa = U + I + P − F − R + ΔSW

ETa = P + ∆SW

The change in soil water storage (ΔSW) was calculated as:

where SW1 is soil water storage pre-sowing (mm), and SW2 is soil water storage post-harvest (mm).

∆SW = SW1 − SW2

Soil water storage (SW) was calculated as [28]:

where h is soil layer depth (cm), p is soil bulk density (g/cm3), and b% is gravimetric water content (%).

SW = h × p × b% × 10

2.3.7. Root Dry Weight and Architecture Parameters

Root samples were collected at the jointing and flowering stages using a 80 mm diameter root auger (Yangling Zhizao Shuibao Instrument Equipment Processing Factory, China). Six cores per plot (three inter-row and three in-row) were averaged. Sampling depths were 0–20 cm, 20–40 cm, and 40–60 cm. After transporting to the laboratory, roots were manually separated, washed, scanned with an HP Scanjet 8200 flatbed scanner (Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, CA, USA) at 600 dpi, and analyzed using WinRHIZO 2019 software for length and surface area before oven-drying at 80 °C to constant weight.

Root density metrics were calculated as:

where RLD is root length density (cm/cm3) and RSAD is root surface area density (cm2/cm3).

RLD = Root length/Soil volume

RSAD = Root surface area/Soil volume

2.3.8. Yield and Yield Components

At maturity, three uniform 0.5 m2 areas per plot were selected to count spikes. Thirty spikes per plot were sampled for grain counts. Plants from three uniform 1 m2 areas per plot were harvested, threshed, sun-dried, and adjusted to 13% moisture content to determine grain yield per unit area. The 1000-grain weight was obtained by weighing three replicates of 1000 kernels per plot.

2.3.9. Nitrogen Content

At maturity, for each plot, 30 plants were collected. The seeds and stems were separated, plant samples were oven-dried, ground, sieved (60-mesh), and stored for later analysis. Total nitrogen was determined by Kjeldahl digestion and an AA3 continuous flow analyzer. Nitrogen use metrics were calculated as follows:

where PFPN is partial factor productivity of nitrogen (kg/kg), NUE is nitrogen utilization efficiency (kg/kg), ANA is aboveground nitrogen accumulation (kg/ha), and GNA is grain nitrogen accumulation (kg/ha).

PFPN = Grain yield/N fertilizer input

GNA = Grain nitrogen content × Grain yield

NUE = Grain yield × ANA

ANA = aboveground dry biomass nitrogen content × aboveground dry biomass

NHI% = GNA/ANA

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were processed using Microsoft Excel 2016. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). All data were analyzed separately for each growing season (2022–2023 and 2023–2024).

Given the absence of the “normal sowing with mulching” treatment combination, the experimental design was an incomplete factorial. Consequently, a formal two-way ANOVA to test the interaction between sowing date and mulching was not feasible. To assess treatment effects, the five treatment combinations were treated as levels of a single factor and analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

The statistical model for this analysis is specified as:

where Y_{ij} is the observed value for the *j*-th replicate under the *i*-th treatment, μ is the overall population mean, α_i is the fixed effect of the *i*-th treatment (*i* = 1, 2, …, 5), corresponding to: (1) Normal sowing date (October 20) without plastic film mulching, (2) First delayed sowing date (30 October) without mulching, (3) First delayed sowing date (30 October) with plastic film mulching, (4) Second delayed sowing date (9 November) without mulching, and (5) Second delayed sowing date (9 November) with plastic film mulching, and ε_{ij} is the random error associated with each observation, assumed to be independently and identically distributed as ε_{ij}~N(0, σ2).

Y_{ij} = μ + α_i + ε_{ij}

When the one-way ANOVA indicated a significant overall treatment effect (p < 0.05), pairwise comparisons between specific treatment means of interest were performed using the Least Significant Difference (LSD) method. This approach allowed us to separately evaluate: (a) the effect of delayed sowing (by comparing treatments 2 & 4 against treatment 1), and (b) the effect of mulching within each delayed sowing date (by comparing treatment 3 with treatment 2, and treatment 5 with treatment 4). Figures were produced using OriginPro 2025 (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Yield and Yield Components

Over the two-year study period, delayed sowing significantly reduced grain yield, spike number per unit area, and 1000-grain weight in winter wheat, with greater reductions observed as sowing was further delayed (Table 2). No significant differences in grains per spike were detected among treatments. Compared to 10-day and 20-day delayed sowing without mulching, plastic film mulching increased yield by 6.7–12.4% (p < 0.05), spike number by 10.75–15.15% (p < 0.05), and grains per spike by 6.5–14.2% (p > 0.05), while decreasing 1000-grain weight by 5.1–5.85% (p < 0.05). Notably, wheat sown with a 10-day delay and mulching exhibited no statistically significant differences in yield or yield components compared to normal-sown wheat.

Table 2.

Effect of different treatments on yield and yield components of late-sown winter wheat.

3.2. Phenological Stages and Soil Temperature

Compared to CK, delayed sowing treatments T1 and T2 shortened the total growing period by an average of 7 and 16 days, respectively (Table 3). Specifically, the sowing-to-emergence (S–E) phase was extended by 7.5 days while the emergence-to-jointing (E–J) phase was shortened by 12 days in delayed treatments. Post-jointing phases (jointing-to-heading, heading-to-flowering, flowering-to-maturity) were each shortened by 1–2 days compared to CK. Plastic film mulching (T1F, T2F) accelerated emergence and advanced subsequent phenological stages, although the overall reduction in growth duration remained similar to bare soil treatments (7.5 and 16 days for T1F and T2F, respectively).

Table 3.

Effect of different treatments on growth-stage duration of late-sown winter wheat.

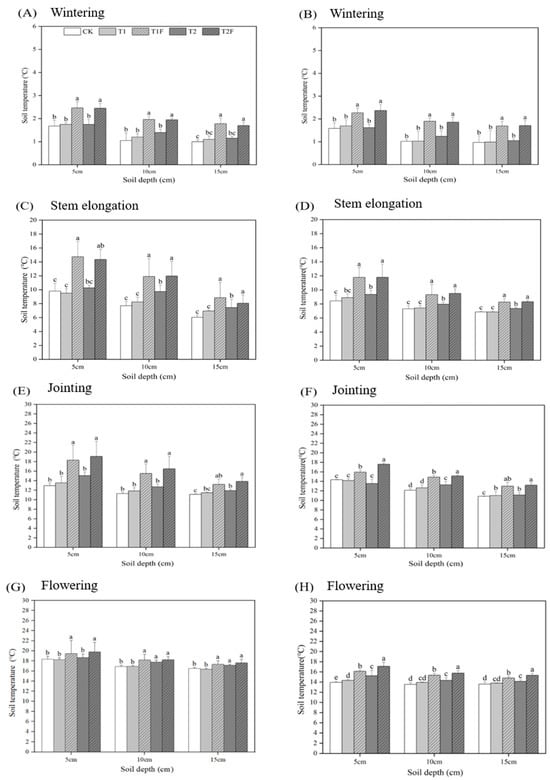

Sowing date did not significantly affect soil temperature. However, plastic film mulching significantly increased soil temperatures during pre-flowering stages (p < 0.05), with the warming effect diminishing as the season progressed (Figure 2). The greatest increase in soil temperature occurred during the overwintering stage, where mulching raised soil temperatures in the 5–15 cm layer by 47.7–54.6%. By the flowering stage, the warming effect had declined to 7.0–7.7%.

Figure 2.

Effect of different treatments on soil temperature in different soil layers (5, 15 and 20 cm) during the (A,C,E,G) 2022–2023 and (B,D,F,H) 2023–2024 winter wheat growing seasons. Error bars are standard errors. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05). Letters are for comparison among treatments within the same year only. CK, T1, and T2 refer to normal sowing, 10-day late sowing, and 20-day late sowing without mulching, respectively. T1F and T2F represent 10- and 20-day late sowing with film mulching, respectively.

3.3. Stem–Tiller Dynamics and Plant Height

Delayed sowing progressively decreased stem and tiller density across all growth stages, with the lowest tiller numbers observed in the 20-day delayed treatment (T2) (Table 4). Plastic film mulching significantly enhanced tiller regeneration. Compared to their non-mulched counterparts, T1F increased tiller density by 13.7%, 51.2%, 9.9%, 25.3%, and 12.2% during the overwintering, stem elongation, jointing, flowering, and maturity stages, respectively. Similarly, T2F increased tiller density by 8.4%, 43.4%, 36.4%, 10.5%, and 11.9% compared to T2.

Table 4.

Effect of different treatments on tiller number of late-sown winter wheat.

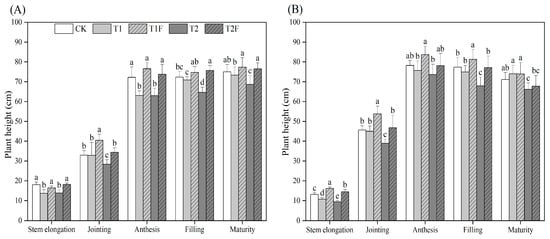

Across both years, plant height followed a consistent trend: CK > T1 > T2 (Figure 3). However, statistical significance of plant height varied by growth stage. At stem elongation, CK, T1F, and T2F were significantly taller than T1 and T2. At jointing, T1F was significantly taller than all other treatments. At anthesis, T1F was significantly taller than T1 and T2. At grain filling, both T1F and T2F were significantly taller than T1 and T2. At maturity, only T2 remained significantly shorter than all other treatments, with no significant differences among CK, T1, T1F, and T2F. Film mulching under delayed sowing significantly improved plant height, with mulched treatments exhibiting greater plant height than corresponding non-mulched treatments.

Figure 3.

Effect of different treatments on plant height dynamics in winter wheat during (A) 2022–2023 and (B) 2023–2024. Error bars are standard errors. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05). Letters are for comparison among treatments within the same year only. CK, T1, and T2 refer to normal sowing, 10-day late sowing, and 20-day late sowing without mulching, respectively. T1F and T2F represent 10- and 20-day late sowing with film mulching, respectively.

3.4. Aboveground Biomass and Root Characteristics

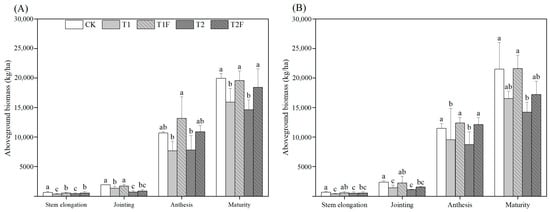

Compared to CK, T1 reduced aboveground biomass by 40.9%, 34.7%, 22.4%, and 21.8% at the stem elongation, jointing, anthesis, and maturity stages, respectively. T2 resulted in even greater reductions—30.3%, 58.1%, 25.4%, and 30.3% at the same stages. Plastic film mulching effectively mitigated these reductions: T1F increased biomass by 44.4%, 42.4%, 50.7%, and 27.0% compared to T1, while T2F increased biomass by 19.6%, 32.0%, 39.3%, and 23.5% over T2. T1F restored biomass to CK levels across all stages, whereas T2F, while significantly improved, remained statistically lower than CK (p < 0.05) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of different treatments on dry matter accumulation at various winter wheat growth stages in (A) 2022–2023 and (B) 2023–2024. Error bars are standard errors. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05). Letters are for comparison among treatments within the same year only. CK, T1, and T2 refer to normal sowing, 10-day late sowing, and 20-day late sowing without mulching, respectively. T1F and T2F represent 10- and 20-day late sowing with film mulching, respectively.

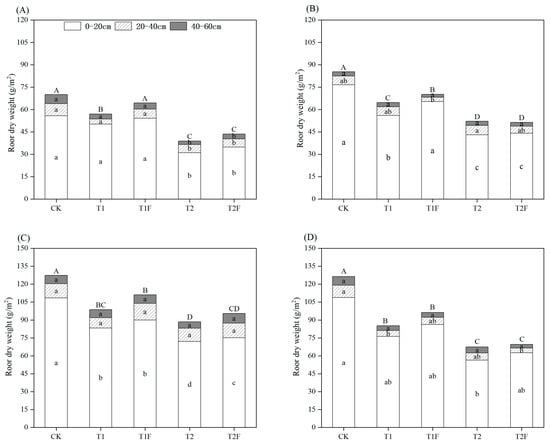

At the jointing stage, root dry weight declined with increasing sowing delay under bare soil. Compared to CK, T1 and T2 reduced root dry weight by 16.85 and 32.20 g/m2, respectively (p < 0.05). Plastic film mulching improved root development under delayed sowing: T1F increased root dry weight by 6.60 g/m2 (10.9%) over T1, and T2F by 2.90 g/m2 (6.6%) over T2. These differences widened by the flowering stage (Figure 5): T1 and T2 exhibited reductions of 35.00 and 48.90 g/m2, respectively (p < 0.05), while T1F and T2F improved root dry weight by 11.80 g/m2 (12.8%) and 4.60 g/m2 (5.9%) relative to non-mulched treatments.

Figure 5.

Effect of different treatments on root dry weight in different soil layers (0–20, 20–40, and 40–60 cm) during the (A,C) 2022–2023 and (B,D) 2023–2024 winter wheat growing seasons at the (A,B) jointing and (C,D) flowering stages. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences in individual soil layers (0–20, 20–40, and 40–60 cm); capital letters indicate differences in total root dry weight (0–60 cm) (p < 0.05). Letters are for comparison among treatments within the same year only. CK, T1, and T2 refer to normal sowing, 10-day late sowing, and 20-day late sowing without mulching, respectively. T1F and T2F represent 10- and 20-day late sowing with film mulching, respectively.

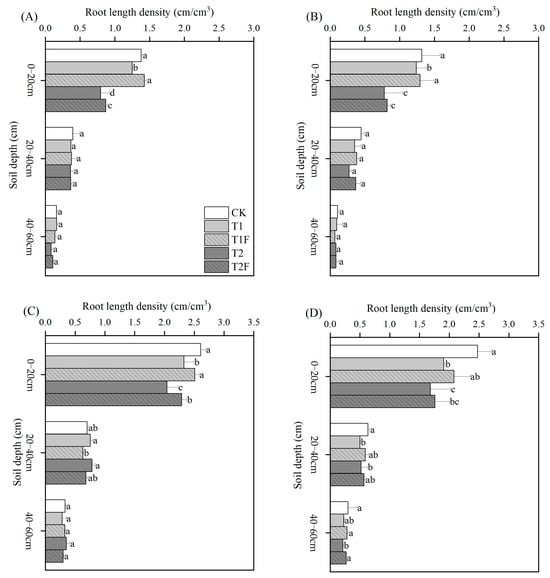

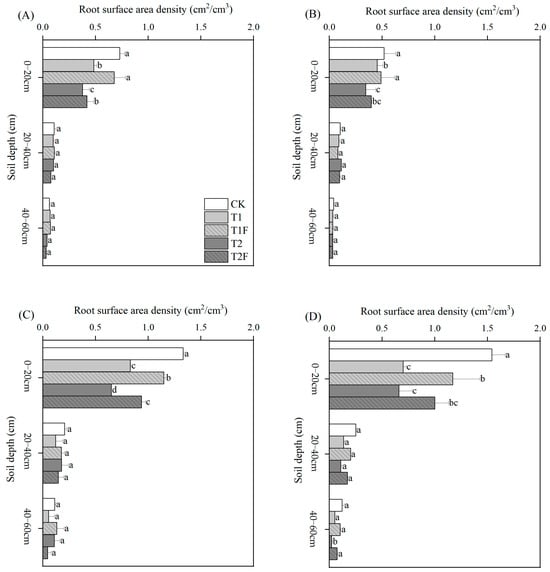

Delayed sowing significantly decreased RLD and RSAD in the 0–60 cm soil layer (Figure 6 and Figure 7). Plastic film mulching under delayed sowing conditions enhanced RLD and RSAD, with differences most evident in the 0–20 cm soil layer. No significant differences were observed in the 20–60 cm soil layers (p > 0.05).

Figure 6.

Effect of different treatments on root length density in different soil layers (0–20, 20–40, and 40–60 cm) during the (A,C) 2022–2023 and (B,D) 2023–2024 winter wheat growing seasons at the (A,B) jointing and (C,D) flowering stages. Error bars are standard errors. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05). Letters are for comparison among treatments within the same year only. CK, T1, and T2 refer to normal sowing, 10-day late sowing, and 20-day late sowing without mulching, respectively. T1F and T2F represent 10- and 20-day late sowing with film mulching, respectively.

Figure 7.

Effect of different treatments on root surface area density of different soil layers (0–20, 20–40, and 40–60 cm) during the (A,C) 2022–2023 and (B,D) 2023–2024 winter wheat growing seasons at the (A,B) jointing and (C,D) flowering stages. Error bars are standard errors. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05). Letters are for comparison among treatments within the same year only. CK, T1, and T2 refer to normal sowing, 10-day late sowing, and 20-day late sowing without mulching, respectively. T1F and T2F represent 10- and 20-day late sowing with film mulching, respectively.

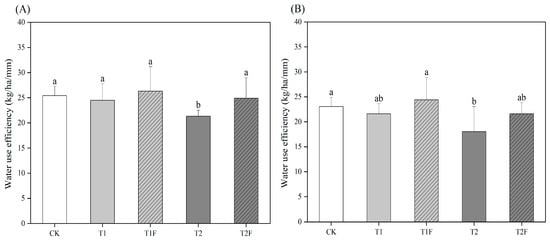

3.5. Water and Nitrogen Use Efficiency

Delayed sowing reduced WUE in winter wheat (Figure 8). Compared to CK, T1 decreased WUE by 1.18 kg/ha/mm (p > 0.05), while T2 significantly reduced WUE by 4.55 kg/ha/mm (p < 0.05). Plastic film mulching significantly improved WUE under 10-day and 20-day sowing delays, restoring it to levels comparable to those of normal sowing.

Figure 8.

Effect of different treatments on water use efficiency during the (A) 2022–2023 and (B) 2023–2024 winter wheat growing seasons. Error bars are standard errors. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05). Letters are for comparison among treatments within the same year only. CK, T1, and T2 refer to normal sowing, 10-day late sowing, and 20-day late sowing without mulching, respectively. T1F and T2F represent 10- and 20-day late sowing with film mulching, respectively.

Delayed sowing reduced GNA, ANA, and PFPN (Table 5). Although T1 showed reductions, these were not statistically significant compared to CK. In contrast, T2 significantly reduced all three parameters. Plastic film mulching improved all three parameters under delayed sowing, restoring them to levels comparable to those of CK. NUE and NHI remained stable across all treatments, showing no significant differences from CK (p > 0.05).

Table 5.

Effect of different treatments on nitrogen utilization of late sown winter wheat.

4. Discussion

4.1. Impacts of Delayed Sowing with and Without Mulching on Winter Wheat Yield and Population Development

According to the dynamic equilibrium theory of yield components—spike number × grains per spike × 1000-grain weight [29]—this study found that delayed sowing in the Guanzhong Plain reduced winter wheat grain yield by 7.1–17.9%. This reduction was associated with simultaneous declines in effective spike number (11.2–23.0%) and 1000-grain weight (4.3–9.6%) (Table 2). The observed yield losses aligned with constrained crop growth dynamics, as wheat yield is largely determined by post-anthesis biomass accumulation and pre-anthesis dry matter remobilization [30]. Consistent with established phenological principles, delayed sowing shortens the vegetative growth period by reducing effective accumulated temperature before winter [31], compromising early crop establishment. Correspondingly, delayed sowing significantly reduced key growth indicators—including tiller density, aboveground biomass, plant height, and root biomass—with the magnitude of reduction increasing with the delay. These declines collectively indicate impaired seedling establishment and vegetative development under late-sowing conditions, ultimately limiting biomass accumulation and yield.

Plastic film mulching is a well-established agronomic practice that improves yields by regulating the soil microclimate [32,33,34]. By enhancing soil temperature and moisture, mulching promotes germination, seedling emergence, and tillering, thereby increasing the number of effective spikes—a primary determinant of yield [35,36,37,38]. In this study, mulching under delayed sowing significantly improved soil hydrothermal conditions and WUE, mitigating yield losses. For the 10-day delay (T1F), mulching restored grain yield to a level comparable to the normal-sown control (CK). For the 20-day delay (T2F), mulching increased yield relative to T2, though yields remained slightly below CK.

Analysis of yield components reveals the mechanism underlying this mitigation. The gains were primarily driven by substantial increases in spike number and moderate increases in grains per spike. A slight trade-off in 1000-grain weight was observed, with a decrease of 5.1–5.85% in mulched treatments (T1F, T2F) compared to unmulched counterparts (T1, T2). This reduction likely reflects a source–sink adjustment: enhanced tillering and spike formation under mulching increased sink capacity (more grains) [39,40], potentially diluting assimilates per grain during filling or prioritizing grain number over individual grain size. Importantly, the positive effects on spike number and grains per spike outweighed the modest decline in 1000-grain weight, resulting in a net increase in yield. These results indicate that, under delayed sowing conditions in the Guanzhong Plain, mulching effectively mitigates yield penalties by maintaining spike formation and grain setting, despite minor reductions in individual grain weight, thereby stabilizing yield component architecture.

4.2. Impacts of Delayed Sowing with and Without Mulching on Winter Wheat Phenology

Soil temperature and moisture dynamics strongly influence plant development [41,42]. This study showed that delayed sowing extended the time from sowing to emergence in winter wheat. This delay is due to reduced daily temperatures, which slow the accumulation of thermal time required for germination, thereby impeding crop emergence and causing early developmental delays [43]. As the plants progressed through their growth stages, the phenological gap between delayed and normal-sown wheat gradually narrowed, with only a 2–3-day difference in maturity. Delayed sowing also shortened the overall growth period, consistent with the findings of [9], highlighting wheat’s adaptability, which can accelerate its development post-emergence to compensate for initial delays.

Plastic film mulching promotes earlier emergence and enhances seedling establishment by modifying the thermal environment of the seedbed [42]. These positive effects are evident from the early growth stages onward [20,44], largely due to elevated soil temperatures [45] that accelerate thermal accumulation. This partial compensation for the thermal deficit caused by late sowing facilitates morphogenesis and development [46,47], directly explaining the patterns observed in our data (Table 3). The substantial prolongation of the sowing-to-emergence (S–E) period under delayed sowing primarily reflects the lower soil temperatures encountered by late-sown seeds. While mulching significantly increases soil temperature, its warming effect is constrained by physical and biological limits; it cannot fully replicate the thermal conditions of seeds sown at the optimal date. As a result, thermal accumulation improves relative to the unmulched late sowing but remains below normal sowing levels. Consequently, emergence occurs faster than in unmulched delayed sowing (reducing the S–E period) but does not completely return to the baseline duration.

Additional constraints associated with late sowing—such as lower soil moisture in the shallow seedbed or inherent physiological thresholds for germination—may not be fully alleviated by temperature increases alone [48]. Therefore, although mulching did not significantly affect the total growth period, it effectively redistributed the duration of specific developmental stages, particularly by shortening the critical S–E phase. This advancement in early phenology helps partially recover the developmental timeline lost due to delayed sowing, ultimately reshaping the subsequent growth rhythm of winter wheat.

4.3. Impacts of Delayed Sowing with and Without Mulching on Root Dynamics in Winter Wheat

Roots are crucial for water and nutrient uptake and synthesizing physiologically active compounds. Their function is linked directly to soil conditions and spatial distribution, and they are fundamental for aboveground growth and grain yield [36,49]. This study found that delayed sowing inhibited root development, reducing surface root biomass, RLD, and RSAD at the jointing and flowering stages. These reductions were primarily due to low temperatures following sowing, which hampered root growth. Plastic film mulching improves root development by increasing soil moisture, elevating soil temperature, and enhancing nutrient cycling [20,50]. In this study, mulching alleviated the adverse effects of delayed sowing on root growth, supporting aboveground biomass production and yield formation. Compared to bare soil cultivation, mulching significantly increased root biomass in the 0–60 cm soil layer and RLD and RSAD in the 0–20 cm surface layer. Enhanced root parameters in the upper soil profile improve the plant’s capacity to access water and nutrients efficiently [35].

4.4. Impacts of Delayed Sowing with and Without Mulching on Water and Nitrogen Utilization in Winter Wheat

Delayed sowing reduced WUE in winter wheat, with longer delays causing more pronounced reductions. This effect is primarily due to lower post-sowing temperatures, which limit thermal accumulation, suppress root growth, and constrain dry matter accumulation [51]. Similarly, delayed sowing decreased NUE, as the shortened vegetative and reproductive phases restricted biomass production and grain yield [52], resulting in significant declines in GNA and ANA (Table 5). Reduced crop productivity and nitrogen uptake also contributed to higher nitrogen losses and soil nitrogen surplus, increasing the risk of groundwater contamination and environmental degradation [53].

Plastic film mulching improves topsoil hydrothermal conditions, which is fundamental for enhancing WUE [54]. This improved rhizosphere environment directly stimulates root growth, producing a more extensive and active root system [35]. Enhanced root development has a dual benefit: it allows more efficient exploration and uptake of soil water and nutrients and strengthens the plant’s physiological capacity for assimilation. Consequently, mulching under delayed sowing increased soil moisture retention and WUE, not only reducing unproductive evaporation and increasing productive transpiration [55,56], but also by supporting a larger root network that sustained higher transpirational demand and biomass production.

Similarly, the observed increases in ANA and PFPN under mulching can be attributed both to reduced nitrate leaching—through decreased surface runoff [57]—and to improved nitrogen uptake efficiency facilitated by enhanced root growth. These improvements in WUE and nitrogen productivity are thus intrinsically linked to the positive modifications in root properties. However, the potential environmental trade-off of plastic residue accumulation (“white pollution”) must be considered [58]. Future research and practice should balance these immediate agronomic benefits against long-term sustainability, potentially through improved film recovery techniques or the development of alternative materials.

5. Conclusions

Within the winter wheat–summer maize cropping system of the Guanzhong Plain, this study showed that delayed sowing shortened the total growth duration and prolonged the winter wheat emergence period, while also inhibiting tiller development, root growth, and aboveground biomass accumulation. Plastic film mulching effectively alleviated these adverse effects by accelerating seedling emergence, promoting tiller formation, and optimizing the temporal allocation across growth stages—ultimately improving yields under delayed sowing conditions. Yield losses were fully compensated with mulching under 10-day sowing delays. However, despite notable improvements, yields under 20-day sowing delays remained below those achieved under normal sowing, indicating that mulching alone cannot fully offset yield losses from prolonged sowing delays. These findings suggest that while mulching is a valuable tool, maintaining yield stability under extended sowing delays will require integrated approaches that include tailored genotype selection, effective water and fertilizer management, and complementary agronomic practices.

Author Contributions

Literature search, R.S., M.R. and F.S.; figures, X.Y.; study design, X.Y., M.Z. (Maoxue Zhang); data collection, X.Y., M.Z. (Maoxue Zhang) and R.S.; data analysis, X.Y., M.Z. (Maoxue Zhang), T.H. (Tiantian Huang), X.H., C.O.J. and T.H. (Tayyub Hussain); data interpretation, X.Y., M.Z. (Maoxue Zhang), T.H. (Tiantian Huang), P.D. and M.Z. (Miaomiao Zhang); writing, X.Y., T.H. (Tiantian Huang), P.D., X.H. and K.H.M.S.; funding, X.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32272217). National College Students Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (No. S202310712097 and No. S202210712400).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Xiaoliang Qin for his invaluable assistance in the management and smooth execution of the experimental project. We also extend our thanks to Pengfei Dang, Xiaoqing Han and Tiantian Huang, our senior colleagues, for their contributions to data analysis, curation, and writing support. Additionally, we acknowledge all friends and colleagues who contributed in various ways but are not listed as authors. This study was conducted at the Caoxinzhuang Experimental Farm in Yangling District, Xianyang City, Shaanxi Province, China.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Verma, S.K.; Chaurasia, S.K.; Pankaj, Y.K.; Kumar, R. Study on the genetic variability and pathogenicity assessment among isolates of spot blotch causing fungi (Bipolaris sorokiniana) in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Plant Physiol. Rep. 2020, 25, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattha, M.U.; Ali, H.; Chattha, M.U.; Hassan, M.U.; Chattha, M.B.; Nawaz, M.; Hussain, S. Combined Application of Distillery Spent Wash, Bio-Compost and Inorganic Fertilizers Improves Growth, Yield and Quality of Wheat. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2018, 28, 1112–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, X.; Wang, F.; Ren, W.; Hao, Z.X. Climate Change Impacts on Winter Wheat Yield in Northern China. Adv. Meteorol. 2019, 2019, 2767018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.Y.; Wu, X.H.; Wu, F.Q.; Wang, X.Q.; Tong, X.G. Life cycle evaluation of winter wheat-summer maize rotation system in Guanzhong area of Shaanxi Province. J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2015, 34, 809–816. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Gao, J.; Gao, F.; Liu, P.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, J.W. Late harvest improves yield and nitrogen utilization efficiency of summer maize. Field Crop Res. 2019, 232, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.P.; Moiwo, J.P.; Tao, F.L.; Yang, Y.H.; Shen, Y.J.; Xu, Q.H.; Liu, J.F.; Zhang, H.; Liu, F.S. Spatiotemporal variability of winter wheat phenology in response to weather and climate variability in China. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Change 2015, 20, 1191–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.L.; Zhang, H.; Jia, J.Z.; Du, L.F.; Fu, J.D.; Zhao, M. Yield Performance and Resources Use Efficiency of Winter Wheat and Summer Maize in Double Late-Cropping System. Acta Agron. Sin. 2009, 35, 1708–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.T.; Wang, Y.H.; Meng, Z.Y.; Xi, L.L.; Duan, G.H.; Wen, H.X. Effects of wheat-maize double night planting on annual yield and resource utilization. J. Wheat Crops 2012, 32, 1102–1106. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, F.; Coulter, J.A.; Ye, C.; Wu, W. Yield penalty due to delayed sowing of winter wheat and the mitigatory role of increased seeding rate. Eur. J. Agron. 2020, 119, 126120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrise, R.; Triossi, A.; Stratonovitch, P.; Bindi, M.; Martre, P. Sowing date and nitrogen fertilisation effects on dry matter and nitrogen dynamics for durum wheat: An experimental and simulation study. Field Crop Res. 2010, 117, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Liang, P.; Wu, P.; Zhu, M.; Li, C.; Zhu, X.; Gao, D.; Chen, Y.; Guo, W. Effects of drought and nitrogen on physiological traits and yield of wheat during grain filling. Field Crop Res. 2021, 270, 108210. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, Z. Root morphological traits and nitrogen uptake of wheat under different nitrogen and water supply. Plant Soil 2021, 459, 287–299. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.; Feng, H.; Liang, X.; Zhang, T.; He, J. Compensatory effects of irrigation and nitrogen application on wheat yield under late sowing conditions in the North China Plain. Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 142, 126672. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Huang, F.Y.; Jia, Z.K.; Ren, X.L.; Cai, T. Response of soil water, temperature, and maize (Zea may L.) production to different plastic film mulching patterns in semi-arid areas of northwest China. Soil Till. Res. 2017, 166, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.M.; Li, F.M.; Jin, S.L.; Song, Y.J. How two ridges and the furrow mulched with plastic film affect soil water, soil temperature and yield of maize on the semiarid Loess Plateau of China. Field Crop Res. 2009, 113, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.G.; Yang, Y.C.; Yu, K.; Feng, H. Effects of straw mulching and plastic film mulching on improving soil organic carbon and nitrogen fractions, crop yield and water use efficiency in the Loess Plateau, China. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 201, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.G.; Chai, S.X.; Chang, L.; Yang, D.L. Effects of different mulching methods on water consumption characteristics and grain yield of dry winter wheat. Agric. Sci. China 2015, 48, 661–671. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Gu, F.X.; Hao, W.P.; Mei, X.R.; Li, H.R.; Gong, D.Z.; Mao, L.L.; Zhang, Z.G. Carbon budget of a rainfed spring maize cropland with straw returning on the Loess Plateau, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 586, 1193–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.Y.; Li, Y.; Lin, H.X.; Feng, H.; Dyck, M. Effects of different mulching technologies on evapotranspiration and summer maize growth. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 201, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.Z.; Xie, B.D.; Liu, D.; Liu, J.J. Effects of mulching materials on nitrogen mineralization, nitrogen availability and poplar growth on degraded agricultural soil. New For. 2011, 41, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.K.; He, W.Q.; Yan, C.R. ‘White revolution’ to ‘white pollution’-agricultural plastic film mulch in China. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 091001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 37804-2019; Technical Specifications for Winter Wheat Growth Monitoring. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Black, C.A.; Evans, D.D.; White, J.L.; Ensminger, L.E.; Clark, F.E. (Eds.) Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 1—Physical and Mineralogical Properties, 1st ed.; American Society of Agronomy and Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1965; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Dane, J.H.; Topp, G.C.E. Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 4: Physical Methods; Soil Science Society of America Book Series; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.P.; Oweis, T.Y.; Garabet, S.; Pala, M. Water-use efficiency and transpiration efficiency of wheat under rain-fed conditions and supplemental irrigation in a Mediterranean-type environment. Plant Soil 1998, 201, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop Evapotranspiration: Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements. FAO Rome 1998, 300, D05109. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S.Z.; Zhang, L.; Liang, Y.L.; Hu, X.T.; Cai, H.J.; Gu, B.J. Effects of limited irrigation on yield and water use efficiency of winter wheat in the Loess Plateau of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2002, 55, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.R.; Zhao, S.L.; Geballe, G.T. Water use patterns and agronomic performance for some cropping systems with and without fallow crops in a semi-arid environment of northwest China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2000, 79, 129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, T.R.; Jamieson, P.D. Yield and grain number of wheat: A correlation or causal relationship? Authors’ response to “The importance of grain or kernel number in wheat: A reply to Sinclair and Jamieson” by R.A. Fischer. Field Crop Res. 2008, 105, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Deng, X.P.; Eneji, A.E.; Wang, L.L.; Xu, Y.; Cheng, Y.J. Dry-Matter Partitioning across Parts of the Wheat Internode during the Grain Filling Period as Influenced by Fertilizer and Tillage Treatments. Commun. Soil Sci. Plan 2014, 45, 1799–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.S.; Agrawal, S.B.; Agrawal, M. Ozone flux-effect relationship for early and late sown Indian wheat cultivars: Growth, biomass, and yield. Field Crop Res. 2021, 263, 108076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.Y.; Feng, H.; Zhao, Y.; Hill, R.L.; Yan, H.M.; Chen, H.X.; Hou, H.J.; Chu, X.S.; Liu, J.C.; Wang, N.J.; et al. Effects of continuous plastic mulching on crop growth in a winter wheat-summer maize rotation system on the Loess Plateau of China. Agric. Forest Meteorol. 2019, 271, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thidar, M.; Gong, D.Z.; Mei, X.R.; Gao, L.L.; Li, H.R.; Hao, W.P.; Gu, F.X. Mulching improved soil water, root distribution and yield of maize in the Loess Plateau of Northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 241, 106340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.B.; Li, Y.N.; Du, Y.D. Continuous ridges with film mulching improve soil water content, root growth, seed yield and water use efficiency of winter oilseed rape. Ind. Crop Prod. 2016, 85, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.M.; Chen, K.Y.A.; Chen, Y.Y.; Ali, S.M.; Sohail, A.; Fahad, S. Mulch covered ridges affect grain yield of maize through regulating root growth and root-bleeding sap under simulated rainfall conditions. Soil Till. Res. 2018, 175, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.A.; Jin, S.L.; Zhou, L.M.; Jia, Y.; Li, F.M.; Xiong, Y.C.; Li, X.G. Effects of plastic film mulch and tillage on maize productivity and soil parameters. Eur. J. Agron. 2009, 31, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Wang, Z.H.; Ma, X.L.; He, H.X.; Cao, H.B.; Wang, S.; Dai, J.; Luo, L.C.; Huang, M.; Malhi, S.S. Wheat Yield Affected by Soil Temperature and Water under Mulching in Dryland. Agron. J. 2017, 109, 2998–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.D.; Liu, M.Y.; Jiang, J.W.; Shi, C.H.; Wang, X.M.; Qiao, Y.Z.; Liu, Y.Y.; Zhao, Z.H.; Li, D.X.; Si, F.Y. Growth, grain yield, and water use efficiency of rain-fed spring hybrid millet (Setaria italica) in plastic-mulched and unmulched fields. Agric. Water Manag. 2014, 143, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulkes, M.J.; Sylvester-Bradley, R.; Weightman, R.; Snape, J.W. Identifying physiological traits associated with improved drought resistance in winter wheat. Field Crop Res. 2007, 103, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.C.; Zhang, J.H. Crop management techniques to enhance harvest index in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 3177–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.T.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Turner, N.C.; Li, X.G.; Niu, J.Y.; Yang, C.; Liu, L.P.; Chai, Q. Ridge-Furrow Mulching Systems-An Innovative Technique for Boosting Crop Productivity in Semiarid Rain-Fed Environments. Adv. Agron. 2013, 118, 429–476. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.A.; Siddique, K.H.M. Does Plastic Mulch Improve Crop Yield in Semiarid Farmland at High Altitude? Agron. J. 2015, 107, 1724–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreccer, M.F.; Chapman, S.C.; Rattey, A.R.; Neal, J.; Song, Y.H.; Christopher, J.T.; Reynolds, M. Developmental and growth controls of tillering and water-soluble carbohydrate accumulation in contrasting wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes: Can we dissect them? J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.K.; Li, Z.B.; Xing, Y.Y. Effects of mulching and nitrogen on soil temperature, water content, nitrate-N content and maize yield in the Loess Plateau of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2015, 161, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, P.J.; Sorensen, I.B.; Jamieson, P.D. Effect of soil temperature on phenology, canopy development, biomass and yield of maize in a cool-temperate climate. Field Crop Res. 1999, 63, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haapala, T.; Palonen, P.; Tamminen, A.; Ahokas, J. Effects of different paper mulches on soil temperature and yield of cucumber (Triticum aestivum L.) in the temperate zone. Agric. Food Sci. 2015, 24, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subrahmaniyan, K.; Veeramani, P.; Harisudan, C. Heat accumulation and soil properties as affected by transparent plastic mulch in Blackgram (Vigna mungo) doubled cropped with Groundnut (Arachis hypogaea) in sequence under rainfed conditions in Tamil Nadu, India. Field Crop Res. 2018, 219, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almansouri, M.; Kinet, J.M.; Lutts, S. Effect of salt and osmotic stresses on germination in durum wheat (Desf.). Plant Soil 2001, 231, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhu, K.L.; Dong, S.; Liu, P.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, J.W. Effects of integrated agronomic practices management on root growth and development of summer maize. Eur. J. Agron. 2017, 84, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.J.; Ma, P.H.; Wu, S.F.; Sun, B.H.; Feng, H.; Pan, X.L.; Zhang, B.B.; Chen, G.J.; Duan, C.X.; Lei, Q.; et al. Spatial-temporal distribution of winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) roots and water use efficiency under ridge-furrow dual mulching. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 240, 106301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, P.D.; Brooking, I.R.; Porter, J.R.; Wilson, D.R. Prediction of Leaf Appearance in Wheat—A Question of Temperature. Field Crop Res. 1995, 41, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.J.; Liu, K.Z.; Li, L.L.; Wei, M.M.; Yang, R.; Xue, K.Y.; Cao, Z.C.; Zhang, C.X.; Li, Y.; Wu, X.; et al. Late-sown winter wheat requires less nitrogen input but maintains high grain yield. Agron. J. 2020, 112, 1992–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.P.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, J.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Q.; Tian, Y.C.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W.X.; Liu, X.J. Optimizing nitrogen application and sowing date can improve environmental sustainability and economic benefit in wheat-rice rotation. Agric. Syst. 2023, 204, 103536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Gu, X.B.; Li, Y.N.; Chen, P.P.; Yang, J.Y.; Li, Y.P. Effects of sowing date and planting pattern on nitrogen transport and yield of winter wheat. J. Henan Agric. Sci. 2021, 50, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.L.; Zhang, X.C.; Song, S.Y. Effects of mulching methods on soil water dynamics and corn yield of rain-fed cropland in the semiarid area of China. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2011, 35, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Cui, R.M.; Jia, Z.K.; Han, Q.F.; Lu, W.T.; Hou, X.Q. Effects of different furrow-ridge mulching ways on soil moisture and water use efficiency of winter wheat. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2011, 44, 3312–3322. [Google Scholar]

- Ruidisch, M.; Bartsch, S.; Kettering, J.; Huwe, B.; Frei, S. The effect of fertilizer best management practices on nitrate leaching in a plastic mulched ridge cultivation system. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2013, 169, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.F.; Wei, Y.N.; Bo, Q.F.; Tang, A.; Song, Q.L.; Li, S.Q.; Yue, S.C. Long-term film mulching with manure amendment increases crop yield and water productivity but decreases the soil carbon and nitrogen sequestration potential in semiarid farmland. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 273, 107909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.