Abstract

Climate change and increasingly severe weather pose dual pressures on agriculture: to reduce carbon emissions and to manage climate risk. These pressures challenge the transition to green, low-carbon development. On the basis of panel data from 31 provinces in China from 2003 to 2023—a period selected for data continuity and to capture the implementation of major national agricultural and environmental policies—in this study, an evaluation index system for agricultural green and low-carbon development (GAC) was established. This study aims to analyze the impact of climate change risks (CPRI) on GAC, focusing on the moderating role of agricultural insurance (INS) and spatial spillover effects. Specifically, it seeks to answer the following questions: (1) What is the direction and magnitude of CPRI’s effect on GAC? (2) Can INS mitigate this effect? (3) Does CPRI exhibit spatial spillover effects on GAC? Using data from the NOAA and Chinese statistical yearbooks, by employing a model with two-way fixed effects, moderating effect analysis, and the spatial Durbin model, the mechanisms underlying the spatial spillover effects of CPRI and regional heterogeneity were examined, as well as the moderating function of INS. CPRI was found to significantly inhibit GAC, as extreme weather events triggered short-term decision-making among farmers and constrained investment in green technologies. These events reduced the capacity of the soil to sequester carbon. This inhibitory effect was greater in nonmajor grain-producing regions and in eastern China. INS helped reduce negative impacts by providing effective risk transfer mechanisms. Furthermore, CPRI was found to exert harmful spillover effects across different regions, with greater indirect effects than direct effects. In conclusion, CPRI significantly hinders agricultural green transition, a process moderated by insurance and characterized by spatial spillovers. On the basis of these observations, we recommend several policies, including the development of regionally tailored adaptation strategies, the achievement of innovation in agricultural insurance products, and the establishment of collaborative governance frameworks that span regions to address these challenges.

1. Introduction

The transformation of global climate patterns is significantly altering the natural environment, which is vital to human survival. The Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) states that the Earth’s average surface temperature has risen by approximately 1.1 °C since the preindustrial era [1]. As a typical climate-sensitive industry, agriculture faces dual constraints, namely, climate change risks and green and low-carbon transformation. From a long-term technological perspective, green and low-carbon transformation may be constrained by technology lock-in. Zhao et al. argue that technological innovation is the key force enabling breakthrough pathways in global energy mix transformation, thereby reshaping long-run low-carbon transition trajectories [2]. On one hand, the agri–food system accounts for approximately one-third of global anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions and is under severe emission reduction pressure imposed by the constraints of dual carbon targets [3]; on the other hand, most of China’s agricultural production regions are located in climate-sensitive zones, where extremely high temperatures, heavy rain and other disasters have occurred frequently in recent years, directly threatening food security [4]. Although China initially built an agrometeorological disaster monitoring network, which has alleviated the adverse effects of severe weather on crop yield to a certain extent, the environmentally friendly and low-emission shift in agriculture is still highly dependent on the natural adaptive capacity of ecosystems [5,6].

Two core strands of research have focused on the interaction between climate change and agriculture in academia: one focuses on risk impacts and is based on experimental observations and empirical modeling, revealing that extreme weather can inhibit crop growth and damage soil ecological function at the physiological level, thus affecting agricultural output efficiency as well as income [7,8,9]. The other category focuses on the path toward sustainable agriculture and low-emission advancement. It aims to explore the role of measures such as green technology adoption, green financial support, production agglomeration, and carbon efficiency optimization in reducing agricultural pollution and carbon emissions [10,11,12]. However, the cited studies aim to analyze either the intensity of climate risk impacts or the strategy for adopting green and low-carbon transformation in isolation; thus, few achievements incorporate both categories of research into a cohesive framework to systematically investigate the behavioral logic of agricultural green and low-carbon transformation under constraints imposed by climate-related risks. Policy environments further shape green innovation incentives. Zhao et al. show that energy restructuring under climate policy uncertainty significantly affects green technology innovation, suggesting that uncertainty in climate-related policies can alter the dynamics of low-carbon transition [13]. A significant gap persists as these two bodies of literature often proceed in isolation; few studies integrate the analysis of climate pressures and green transition strategies into a unified framework. This separation limits a systematic understanding of agricultural systems under dual constraints.

Specifically, this study reveals three areas for improvement following an analysis of the research gaps. First, the buffer mechanism of agricultural insurance (INS) remains underexplored. The literature discusses disaster reduction and income growth, but lacks targeted empirical evidence on INS mitigating climate shocks and inhibiting agricultural green transformation. Second, spatial correlation has been neglected. Climate change risk (CPRI) and agricultural green low-carbon development (GAC) have regional linkages; however, research remains local and fails to reveal transregional spillover mechanisms through spatial analysis. Third, the analytical framework lacks integration. Most of the literature focuses on a single subject or area of research, making it difficult to explain complex agricultural systems while accounting for both green transformation and carbon emission reduction.

In response to these gaps, this study focuses on the following three research questions: (1) What are the direction and magnitude of the effects of the CPRI on GAC? (2) Does INS (farmers’ insurance against climate-related losses) mitigate the inhibitory effects of these risks by stabilizing farmers’ expectations and adjustment costs (the costs and uncertainties faced by farmers when changing practices in response to new risks)? (3) Are there cross-regional spatial spillover effects (impacts that spread from one region to another) between the CPRI and GAC? To address these interconnected questions, the primary objective of this research is to construct and empirically test a unified framework that elucidates how climate change risks influence agricultural green and low-carbon development, while specifically evaluating the potential moderating role of agricultural insurance and assessing the presence of spatial spillover effects. An integrated framework of risk impacts, insurance regulation, and spatial coordination connects climate risk, adaptation through insurance, and regional interactions. In this paper, panel data at the provincial level and econometric models are employed to analyze the specific influence paths and mitigation mechanisms. The theoretical goal is to improve the cross-study of the CPRI and GAC, and the practical goal is to guide the design of the agro-climate governance system.

The remainder of this study is structured as follows: Section 2 presents a review of the existing research, the points of consensus and controversies are analyzed, and the core limitations are outlined. Section 3 clarifies how the CPRI impedes GAC. It reveals three direct transmission channels, namely, farmers’ behavior distortion, technology investment inhibition, and ecological function degradation, and presents research hypotheses. In Section 4, fixed effects, moderating effects, and spatial Durbin models are constructed, and variable definitions, measurement methods, and data processing procedures are provided. Section 5 presents the empirical test, the instrumental variable method, and the robustness test, which are used to enhance reliability, and the moderating effect of INS and the spatial spillover mechanism of the CPRI are examined. Section 6 provides an explanation of the empirical results with reference to the literature and theory, thereby analyzing the inhibitory mechanism, moderating paths, and causes. Section 7 offers a summary of the core findings and presents suggested strategies for regional differentiation, insurance innovation, and cross-regional collaborative governance.

2. Literature Review

Climate change and sustainable low-carbon agricultural development are vital to global sustainability. The literature is reviewed across the following four areas: climate risk impact, drivers of green and low-carbon transformation, insurance regulatory mechanisms, and spatial collaborative governance. It identifies gaps and thus lays a theoretical foundation for future research.

2.1. Dual Stresses of the CPRI on Agricultural Systems

Climate change exerts multidimensional pressure on agricultural systems through extreme temperatures, drought, floods, and other events. Via the use of control experiments, Li et al. [14] compared the physiological responses of heat-resistant and heat-sensitive maize inbred lines at the grain-filling stage and reported that high-temperature stress significantly reduced the grain weight, seed production rate, and grain maturation rate of maize, explaining the internal path of heat-sensitive crop yield reduction at the molecular and physiological levels. Jarin et al. [15] systematically reviewed the effects of water scarcity on the morphological, physiological, and biochemical attributes of rice, emphasizing the key roles of water use efficiency, photosynthesis regulation, antioxidant mechanisms, and osmoregulatory substances. On the basis of historical flood data, Rupngam and Messiga [16] revealed that floods caused by extreme rainfall reduced agricultural productivity through their impact on soil physical structure, chemical properties, and biological activity. Additionally, Han et al. [17] integrated the spatiotemporal characteristics of temperature fluctuations in China and the production data of agricultural areas to measure the role of temperature fluctuations in shaping the frequency of severe weather phenomena and confirmed that climate instability exacerbated the risk of crop production. The existing research has three limitations: first, it focuses on short-term economic output, ignoring the long-term inhibition of the capability for transformation in GAC; second, the evaluation indicators are not fully included in the green and low-carbon transition variables; and third, there is no thorough evaluation of compound climate risks, leaving research space for subsequent discussion on the interaction between risks and transition.

2.2. Driving Mechanism for GAC

The literature discusses driving mechanisms from the viewpoints of monetary assistance, technological innovation, industrial organization optimization, and digital application. At the production stage, mechanization services are also an important driver of green transformation. Li and Guan show that agricultural mechanization services significantly promote agricultural green transformation by improving factor allocation efficiency and reducing energy intensity [18]. Cao and Gao [19] empirically analyzed the influence of sustainable finance on greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture and nonpoint source contamination and analyzed the internal workings of sustainable finance to promote a decrease in agricultural pollution as well as a reduction in carbon emissions by optimizing resource allocation, deepening technology penetration, and strengthening policy coordination. On the basis of the data of grain production functional zones, Lu et al. [20] used the super-efficiency DEA model to show that the production agglomeration level significantly promoted GAC by expanding the moderate-scale operation of cultivated land and promoting the impact of agricultural technology beyond its initial application. To confirm the significant promoting effect of the advancement of the digital economy in rural areas on agricultural carbon emission reduction, Su et al. [21] adopted the fixed effect model and instrumental variable approach and emphasized that the intermediary mechanism and regional heterogeneity of environmentally friendly technological innovation are the key paths to achieving emission reduction targets. Beyond environmental performance, the rural digital economy also generates inclusive development effects. Lu et al. provide evidence from China showing that the development of the rural digital economy significantly promotes shared prosperity among farmers, indicating that digital-driven green transformation yields both environmental and socioeconomic benefits [22]. Using provincial-level data from China, Fu et al. further confirm that digitalization significantly promotes agricultural green development, mainly by improving production efficiency and optimizing resource allocation [23]. At the provincial level, digitalization has been empirically confirmed as an important driver of agricultural green development. Fu et al. find that improvements in digital infrastructure and digital governance significantly promote agricultural green development in China, mainly by enhancing technological efficiency and optimizing resource allocation. Jin et al. [24] used the entropy method, spatial Durbin model, and panel threshold model to determine that a digital economic system in the countryside can assist in reducing carbon emissions from agriculture and the importance of digital technology to rural sustainable energy transformation and green agricultural cultivation. However, most existing studies assume climate stability and do not account for the CPRI that disturbs the transition path. Institutional arrangements related to land use also interact with green agricultural outcomes. Xu et al. find that land transfer significantly affects food security, and that environmental regulation and green technology innovation play important mediating roles in this process, highlighting the linkage between land systems and green agricultural development [25]. There is a lack of empirical evidence on high-risk scenarios, creating a research gap and limiting prior risk research.

2.3. Regulatory Function of INS

The role of INS in reducing disasters and stabilizing income has been widely verified. However, it has not been fully integrated with the transformation of GAC. Recent empirical evidence links agricultural insurance directly to carbon reduction outcomes. Jiang et al. find that agricultural insurance significantly reduces agricultural carbon emissions in China, and that low-carbon technology innovation plays a mediating role, indicating that insurance can guide green production behavior beyond its traditional risk-compensation function [26]. Recent evidence from China further indicates that agricultural insurance contributes to agricultural carbon emission reduction not only through risk compensation but also by stimulating low-carbon technology innovation. Jiang et al. show that agricultural insurance significantly lowers agricultural carbon emissions, and that low-carbon technological innovation plays a mediating role in this process, highlighting the potential of insurance to guide green production behavior. On the basis of provincial panel data and a fixed effects model, Lin and Wang [27] reported that INS could effectively buffer the effects of natural disasters on agricultural economic growth and significantly reduce output fluctuations and economic losses. Li et al. [28] noted that INS has a dual mechanism: it not only directly encourages farmers to adopt green production technology and produce high-value-added agricultural products but also promotes the advancement of sustainable agriculture through the optimal distribution of agricultural production factors. Cai et al. [29] improved the production function of harm reduction and reported, based on the endogenous treatment effect model, that the degree of pesticide overuse among insured farms was significantly lower, indicating that INS can optimize pesticide use behavior and guide green production, which is positively related to GAC. Zhou et al. [30] applied functional decomposition to analyze the multidimensional functions of INS and demonstrated its positive impact on rural revitalization through empirical analysis. The following three gaps exist in existing research: first, it ignores the regulatory function within the connection between the CPRI and GAC; second, it lacks a macroregional and multitool synergy perspective; and third, the INS mechanism is not included in the overall governance framework, which provides an entry point to compensate for the gaps in previous research.

2.4. Importance of Spatial Spillovers in Agro-Climate Governance

Spatial econometric methods have advanced regional association research, but the cross-regional transmission mechanism remains underdeveloped. From the perspective of financial geography, Quan and Quan demonstrate that financial agglomeration exerts a significant spatial spillover effect on green low-carbon development, suggesting that regional financial clustering can transmit green development momentum across space [31]. Karahasan and Pinar [32] emphasized that in areas with significant geographical heterogeneity, ignoring spatial correlation leads to the overall failure of climate adaptation policies, and identifying the spillover effect of policies through spatial econometric methods is essential for improving the accuracy of agro-climate governance and preventing overall efficiency loss. Xu and Lu [33] systematically analyzed the spatial characteristics of China’s GAC and reported that there were apparent spatial spillover effects between the whole country and different economic regions, that the effects of various influencing factors on green development were significantly heterogeneous across regions, and that cross-regional coordination was key to agricultural green transformation. Focusing on green technology innovation, Liu et al. find that the development of a low-carbon economy exhibits significant spatial spillover effects across Chinese provinces, and that green technology innovation plays a central role in shaping these spatiotemporal disparities [34]. Liu et al. [35] used a spatial lag model to analyze carbon emissions from agriculture in the Beibu Gulf urban agglomeration and reported that emissions exhibited high–high and low–low aggregation characteristics, reflecting regional linkage. Malaekeh et al. [36] constructed a spatial panel model to evaluate the long-term impact of the CPRI on Iran’s agricultural economy and reported that ignoring spatial spillovers would lead to errors in the model setting, predicting that the regional difference in the decline in net farmland income in the middle and late centuries would reach 8% to 51%. Although research has specifically examined the importance of spatial factors in understanding various phenomena, the cross-regional transmission mechanism of risk and transformation remains underdeveloped, and a differentiated governance strategy needs to be further explored to address this research gap.

In summary, the current research has made important progress, but it still exhibits several limitations. First, there is a binary separation of perspectives, and the microlevel risk impact and macrolevel transformation mechanisms are not integrated into a unified framework; thus, revealing the internal mechanism through which the CPRI inhibits GAC is difficult to determine. Second, the regulatory role of INS has not been examined sufficiently, and its synergistic value in mitigating the inhibitory effect of the CPRI on GAC has not been verified. Third, the spatial spillover effect is neglected, and the transregional transmission mechanism is not precise. Fourth, most existing studies are based on the climate steady-state hypothesis, and dynamic analysis is insufficient.

Given the above gaps, this paper aims to provide the following contributions: at the theoretical level, an analytical framework integrating risk shocks, insurance regulation, and spatial correlation is constructed. At the empirical level, multidimensional risk indicators and spatial econometric methods are used to determine CPRI regional heterogeneity and the buffering effect of INS. At the policy level, suggestions for regional governance and coordination are proposed to provide a basis for transforming agro-climate governance from a one-size-fits-all approach to precise actions.

2.5. Conceptual Framework

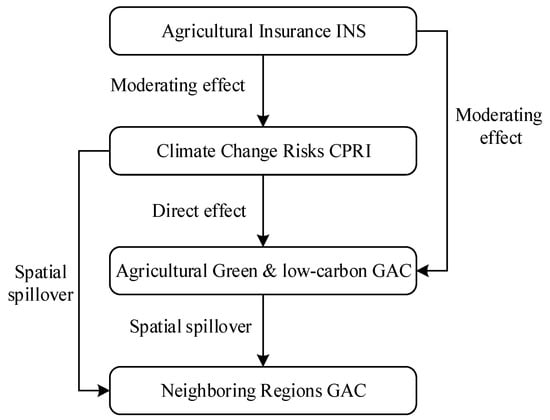

Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework integrating the key variables examined in this study: CPRI, GAC, INS, and their spatial interdependencies. The framework illustrates three core relationships: the direct influence of CPRI on GAC, the moderating role of INS, and spatial spillover effects across regions. This integrated perspective provides the theoretical foundation for the empirical analysis. The framework addresses the literature gaps by simultaneously considering risks impact, insurance mechanisms, and spatial interdependencies, offering a coherent basis for subsequent empirical testing.

Figure 1.

Core Relationships Between INS, CPRI, and GAC.

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. Direct Inhibition Mechanism of the CPRI on GAC in China

The goal of GAC is to reduce emissions, gain efficiency, and achieve ecological sustainability through technological innovation, the transformation of industrial models, and changes in behavior among business entities. As a key exogenous shock, the CPRI directly hinders the development of farmers by interfering with their behavior, inhibiting the adoption of green technology, and weakening the agricultural ecological foundation [37,38,39]. First, short-term adjustments in farmers’ production behavior lead to negative ecological externalities. Climatic disasters disrupt agricultural production. The increase in crop diseases and pest incidents has prompted farmers to apply more pesticides [40]. Moreover, to increase current yields and compensate for disaster losses, farmers in rotation areas often significantly increase fertilizer intensity. Although this behavior can temporarily maintain output, it increases the carbon intensity per unit of output, creating the dilemma of stable production but emission increases, which directly hinders the transition to GAC. Second, risk reduction promotes green technology adoption. Agricultural green technology typically requires a significant initial investment, an extended return period, and income uncertainty [41]. Extreme temperatures and floods not only reduce farmers’ current planting income but also increase production and maintenance costs. Finally, the inclination to embrace green technology is restrained, which prompts a switch to a low-cost, extensive production mode, leading to the failure to adopt green technology and the formation of a climate-risk green technology trap [42]. Third, the degradation of ecosystem functions reduces the basic capacity of carbon sinks. Agricultural carbon sinks depend on the following two primary processes: photosynthesis in crops and the sequestration of carbon in the soil. However, extreme climate can inhibit crop growth, reduce photosynthetic efficiency, and reduce transpiration, thereby affecting the relationships among crops, microorganisms, and pathogens and undermining agricultural productivity [43]. Climate fluctuations also exacerbate soil erosion, soil compaction, and soil health degradation, thereby increasing soil salinization, reducing the carbon storage potential of soil, restricting the sustainability of agricultural carbon sinks at the source, and restricting GAC [44].

In summary, the CPRI has a considerably adverse effect on threats to GAC via three direct transmission routes: by distorting farmers’ behavior, inhibiting technology adoption, and destroying the ecological foundation.

Hypothesis H1:

The CPRI negatively affects GAC.

3.2. Moderating Effect of INS in China

In light of increasing global climate risks, agricultural producers encounter the dual challenges of heightened output volatility and reduced income stability [45]. INS alleviates the inhibitory effect of the CPRI on GAC by transferring risk, empowering resources, and guiding behavior. First, stable earnings forecasts reduce loss compensation technology investment risk. INS transfers some climate risk losses from farmers to insurance institutions, alleviating the pressure of poverty caused by disasters or plummeting income and improving the stability of farmers’ production income, which studies in the Chinese context have shown to be crucial for enhancing their confidence in adopting green technologies [46,47]. Second, the improvement in credit availability alleviates green investment constraints. Research focusing on China indicates that, as credit collateral, insurance policies can reduce information asymmetry between farmers and financial institutions, alleviate loan difficulties, and help farmers expand their business scale and increase investment in green technology [48]. In addition, behavioral incentives guide green production, creating a positive feedback loop. The risk buffer offered by INS motivates farmers to implement more environmentally friendly manufacturing approaches, such as organic farming practices, and environmentally friendly technologies, and reduce the application of polluting chemicals [49,50]. Evidence from China suggests that differentiated premium pricing and compensation rules link production behaviors to risk costs, thereby creating positive incentives for low-carbon agricultural behaviors [51,52]. This incentive-compatible mechanism encourages farmers to choose low-carbon technologies [53]. Finally, additional services reinforce risk response capabilities to underpin long-term willingness. In the underwriting process, insurance institutions often provide meteorological warnings, disaster prevention and mitigation technical guidance, and other services to help farmers identify climate risks and take adaptation measures, which, according to analyses of Chinese practices, not only reduces temporary losses but also enhances willingness to adopt low-carbon practices in the long term by improving risk perception and management ability [54].

In terms of the global climate, INS helps sustain the enthusiasm of agricultural producers through its stabilizing effect, creates a buffer for adopting sustainable, low-carbon technologies, and weakens the inhibitory effect of the CPRI.

Hypothesis H2:

INS exerts an adverse moderating effect on the impact of the CPRI on China’s GAC.

3.3. CPRI Exerts Spatial Spillover Effects on GAC in China

The first law of geography states that there is spatial correlation among geographical objects, and the closer the proximity is, the more significant the interaction is [55]. Natural geographical factors, such as cultivated land quality, regional climate background, and ecosystem service functions, which are closely linked to GAC, exhibit significant spatial autocorrelation [56]. Although administrative boundaries divide regions with similar natural geographies into different management units, resulting in a spatial pattern of natural continuity and administrative separation, they cannot block the transregional spillover of the CPRI [57]. First, cross-domain flows of natural factors strengthen spatial correlation; geographical location defines the natural environmental constraints faced by agricultural production, and adjacent areas share similar agricultural production environments and influence each other through the continuity of natural processes [58]. The CPRI transmits shocks to adjacent areas through the mobility of natural elements such as precipitation and wind fields. The division of administrative boundaries disrupts natural geographical continuity. If the impact of the CPRI is examined only locally, then the cross-regional transmission mechanism will be ignored, leading to an underestimation or misjudgment of the overall effect. Extreme weather events, regional ecological disasters, and long-term climate trend changes driven by CPRI exhibit apparent spatial diffusion and transboundary transmission characteristics, with linkage effects on surrounding areas [59]. Previous studies have indicated that the impact of the CPRI on agriculture varies significantly across different regions and over time [60]. For example, the spatial distribution of agricultural indicators, such as grain yield, is strongly correlated with climatic conditions in neighboring areas [61]. Third, the linkage of the industrial chain increases the scope of spillover. The CPRI directly affects agricultural production and the entire agricultural industrial chain, including the upstream and downstream sectors [62]. GAC involves the supply, production, processing, sales, and other links of agricultural materials. Moreover, the CPRI can affect upstream or downstream sectors and an entire region through the industrial chain.

In summary, incorporating the concept of spatial spillover to analyze the cross-regional effects of the CPRI on GAC is essential.

Hypothesis H3:

The impact of the CPRI on China’s GAC has a significant negative spatial spillover effect.

4. Research Design

4.1. Description of the Study Area

This study examines 31 provincial-level units in mainland China as the research area. This scope is justified by three considerations. First, these units form China’s complete sub-national administrative system, collectively representing the nation’s agricultural economy. Second, provincial data provides the optimal balance between availability and reliability for longitudinal analysis. Third, this level aligns with China’s policy implementation framework, ensuring practical relevance for agricultural and environmental governance. The 2003–2023 study period captures significant climate policy developments and agricultural transformations, providing sufficient observations for robust analysis while covering key policy milestones relevant to our research questions.

4.2. Data Source and Processing

In this paper, 31 provinces in China are used as the study area, and balanced panel data from 2003 to 2023 are used for the empirical analysis. The explanatory variable CPRI refers to Du et al. and He et al. for the research [63,64], the NOAA dataset for measurements was selected. The data for the other variables are obtained from the China Population and Employment Statistical Yearbook, China Insurance Statistical Yearbook, and other statistical yearbooks.

4.3. Variable Definition, Measurement, and Descriptive Statistics

Explained variable: Green and low-carbon agricultural development (GAC). The evaluation index system of GAC is established from the four dimensions of high efficiency, modernization, green initiatives, and low carbonization, and the value of GAC is calculated by the entropy method and multiplied by 100 (it does not affect the conclusion and is helpful for data observation) [65,66,67,68].

The core explanatory variable is climate change risk (CPRI). The CPRI dataset includes four subindices: 1. days of extreme low temperature (LTD); 2. days of extreme high temperature (HTD); 3. days of extreme rainfall (ERD); 4. days of extreme drought (EED). The CPRI assesses climate-related physical risks in a country or region.

The moderating variable is the agricultural insurance level INS, which is represented by agricultural insurance premium income/agricultural employees.

Control variables: Control variables are selected with reference to the methods of Ren et al. [69], Cui et al. [70], and Wang et al. [71]. Urbanization level (urb): proportion of permanent urban residents in the total population (%); agricultural disaster rate (adr): the percentage of affected area in the crop-sown area (%); agricultural planting structure (as): the percentage of food crop-planting area in the total crop-planting area (%); and total water supply (swt): total water supply indirectly regulates the availability of agricultural water through policy channels. Theoretically, the agricultural water supply is a direct indicator of the water resource constraints of agricultural production. However, before 2015, some provinces did not independently calculate agricultural water use, and the statistical caliber was inconsistent; thus, total water supply was selected as a proxy variable. Optimization of industrial structure (cyjg): the tertiary industry’s added value/the secondary industry’s added value (Table 1).

Table 1.

Evaluation Index System of GAC.

Descriptive statistics for all variables used in the empirical analysis are provided in Table 2. The summary confirms significant variation in the data, and no extreme outliers were detected, validating the suitability of our panel data econometric models.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of the Variables.

4.4. Model Setting

To assess the impact of CPRI on China’s GAC, a fixed effect model (1) is constructed to verify H1, which can be expressed as follows:

GACit = α0 + α1CPRIit + αKCONit + λi + vt + εit

In Model (1), the subscripts i and t denote province and year, respectively; λ and v denote the fixed effects controlling for regional and time differences; CON denotes the control variables; and εis the random disturbance term.

To test the moderating role of agricultural insurance level in determining the relationship between the CPRI and GAC, the moderating effect model (2) is used to verify H2, and this model is as follows:

GACit = β0 + β1CPRIit + β2INSii + β3CPRIitINSii + βkCONit + λi + vt + εit

INS in Model (2) is the moderating variable, the level of agricultural insurance.

On the basis of research on the spatial spillover effect of climate change risk, the analysis uses a double fixed spatial Durbin model (3) after several tests:

where γ1 is the constant term; γ2 captures the local effect of CPRI; γ3 represents the spatial autoregressive coefficient of GAC, indicating spatial dependence across regions; γ4 and γ5 denote the spatial lag coefficients of control variables and CPRI in neighboring regions, respectively. W is the spatial weight matrix, while λi and vt control for region-fixed and time-fixed effects.

GACit = γ1 + γ2CPRIit + γ3WGACit + γ4WCONit + γ5WCPRIit + λi + vt + εit

4.5. Multicollinearity Diagnostics

This paper adopts the variance inflation factor test method to test the model regression. Variance inflation factor (VIF) tests were conducted to assess potential multicollinearity, with a VIF above 10 indicating severe collinearity. Table 3 presents the VIF results for the key model specifications, including analyses of the climatic sub-indicators in isolation and combination. All obtained VIFs are substantially below 2 (well below 10), confirming that severe multicollinearity is absent and the estimation results are robust.

Table 3.

Multicollinearity Test.

5. Empirical Analysis

5.1. Benchmark Regression Analysis

The data in Table 4 indicate that the CPRI significantly inhibits GAC. In both models without (Column 1) and with control variables (Column 2), the CPRI has a negative effect at the 1% level, validating H1. Additionally, disaggregated extreme weather types, such as HTD (Column 4) and LTD (Column 3), also negatively impact GAC at the 5% level. Temperature anomalies increase carbon emissions by negatively affecting crop growth cycles, inducing pests and diseases, and changing soil structure [72]. ERD (Column 5) significantly inhibits GAC at the 1% level. This result occurs because the root hypoxia, soil nutrient loss, and microbial activity decline caused by farmland water directly weaken the function of the agricultural carbon sink [73]. The coefficient of EED (Column 6) is negative but not significant, which can be explained by the effect of drought propagation time and the adaptive behavior of farmers. Geng et al. [74] reported that the average cycle of drought transmission from meteorology to agriculture in China is 4.1 months. During this window period, farmers can mitigate the impact of drought and indirectly reduce carbon emissions by adopting drought-tolerant crops and water-saving technologies [75]. Finally, the negative impact does not reach a significant level.

Table 4.

Regression Results of the Benchmark Model.

In terms of control variables, urb, swt, and as have a significant effect. For example, the traditional urbanization model ignored coordinated ecological development before 2014 and had adverse effects on GAC because it occupied cultivated land and consumed agricultural ecological resources [76]. After 2014, although new urbanization reduced the rural population, it led to a sharp increase in carbon-intensive inputs, thereby increasing agricultural carbon emissions [77]. The increase in swt indirectly promotes GAC by supporting the adoption of efficient water-saving irrigation technology, which not only reduces irrigation energy consumption but also reduces fertilizer leaching loss and directly reduces greenhouse gas emissions [78]. For as, the expansion of the cultivation zones of rice, corn, and other crops significantly increases carbon emissions [79]. In contrast, optimizing the planting structure can directly reduce emissions and improve the regional carbon balance by enhancing crop carbon absorption [80,81].

5.2. Benchmark Regression Endogeneity and Robustness Tests

Endogenous treatment. The interaction term between the standard deviation of the annual average temperature (AAT) in each province from 1971 to 2000 and the time trend is selected as the instrumental variable. The standard deviation of the annual mean temperature reflects not only historical vulnerability to provincial climate fluctuations (highly related to current climate risks) but also the exogeneity of historical data. The standard deviations of the annual mean temperature and time trend are multiplicative to generate interaction terms, which can not only introduce time-varying characteristics into the panel fixed effect model and avoid being absorbed by provincial fixed effects, but also capture the trend differentiation of different vulnerable provinces with global warming. Column (1) of Table 5 shows that the CPRI is highly positive at the 1% level, the Cragg–Donald F value is 55.954 (the critical value is 16.380), and the LM statistic’s p value is 0.000, which rejects the null hypothesis of a weak instrument, and the CPRI is significantly negative at the 5% level after endogeneity correction, confirming its robust negative impact on GAC. To improve reliability, two tests were performed: First, replacing the instrumental variable with the standard deviation of annual average precipitation (AAW) in Column (2) produced robust results; second, introducing geographical endowment (LC) alongside AAT in Column (3) resulted in the CPRI being negative at the 10% level. In summary, the benchmark regression result remains robust after controlling for endogeneity, and the significant negative impact of the CPRI on GAC is confirmed.

Table 5.

Instrumental Variables.

Robustness test. The control variable, environmental regulation intensity (lnenv, the logarithm of pollution control investment/GDP for each province), is added. This variable has the potential to diminish pollution from agriculture and lower carbon emissions through the promotion of advancements in industry and supporting technological development [82]. Columns (1) to (4) of Table 6 show that after adding this variable, the coefficients of CPRI, LTD, HTD, and ERD are still significantly negative at the 1%, 5%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively. Winsorization treatment. Columns (5) to (8) report the regression results after 1% wind-down, and the coefficients of CPRI, LTD, HTD, and ERD are significantly negative at the 1%, 1%, 10% and 1% levels, respectively. In summary, the negative impact of the CPRI on GAC is robust.

Table 6.

Robustness Test: Baseline Regression.

5.3. Moderating Effect Analysis

To test the moderating effect of INS, the results of the analysis based on Model (2) are presented in Table 7. Columns (1) to (3) include the CPRI, INS, and their interaction term CPRI × INS to test the influence of each variable on GAC. The coefficient of CPRI × INS is −0.005 and is significantly negative at the 1% level (t = −3.228). These findings indicate that INS significantly moderates the relationship between the CPRI and GAC, thereby verifying H2. On the basis of current research, the regulatory mechanism of INS can be explained from two perspectives. First, INS can effectively mitigate the effect of the CPRI on farmers’ income by providing economic compensation. This support enhances the economic resilience of agricultural production and stabilizes long-term production expectations [83]. Second, with the help of policy incentives such as premium subsidies, INS can reduce the uncertainty of the costs and benefits of adopting sustainable and low-carbon technologies and alleviate the inhibitory effect of the CPRI on GAC [84].

Table 7.

Moderating Effect Test.

5.4. Endogeneity and Robustness Tests of the Moderating Effects

Robustness test. In this study, INS is remeasured as the premium income of agricultural insurance divided by the added value of the primary industry. Table 8 shows a significant coefficient of −0.016 for CPRI × INS (t = −2.556). This result confirms the stability and reliability of INS’s moderating effect on the relationship between the CPRI and GAC.

Table 8.

Robustness Test: Moderating Effect.

Endogeneity test. Owing to the endogeneity of the CPRI, its interaction term with INS may also be endogenous. AAT, the standard deviation of the average temperature in each province from 1971 to 2000, is used as the instrumental variable for the CPRI, and AAT × INS is constructed as the instrumental variable for the interaction term. Column (1) of Table 9 shows that AAT is significantly positive at 1%, and AAT × INS is positive at 10%. The instrumental variable meets the correlation requirements, passing the weak instrumental variable test (Cragg–Donald F = 7.632 > 7.03, when the maximum allowable IV bias is 25%, the critical value is 7.03) with a p value of 0.0248 and rejecting the null hypothesis of unidentifiability. To reduce the potential endogeneity of INS, the average precipitation AW (affecting agricultural risk exposure and related insurance demand) from 2003 to 2023 and the export level of agricultural products trd (reflecting the demand for green production of economic extroversion and indirectly related insurance input) are selected as the instrumental variables of INS, and the endogeneity of the CPRI and INS are also processed. In Column (2) of Table 9, the weak instrumental variable test passes (Cragg–Donald F = 8.916), and the LM statistic’s p-value is 0.0825, rejecting the unidentifiable null hypothesis. After correcting for endogeneity, the interaction term’s coefficient is significantly negative at the 5% level, with an over-identification test p-value of 0.827, which meets the exogeneity requirements, indicating that the moderating effect of INS remains robust.

Table 9.

Endogeneity Test.

5.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

Heterogeneity analysis is conducted across grain functional areas and regions.

Heterogeneity of grain functional areas: major and nonmajor grain-producing areas. Table 10 (Columns 1 to 2) indicates that the CPRI coefficient for major grain-producing areas is not statistically significant. As the core area of national food security, this region enjoys policy support, including infrastructure efforts and the promotion of intensive production technologies, under the National High-Standard Farmland Construction Plan (2021–2030). Combined with the advantages of natural conditions, the region has a high level of food security [85]. Moreover, the carbon sink function and positive externalities make it more capable of being resilient against climate shocks and effectively buffer the impact of risks [86]. The coefficient of the CPRI in nonmajor grain-producing areas is significantly negative at the 5% level. This region failed to obtain the key support of the Pilot Work Plan for Agricultural Green Development (resources are concentrated in grain production, and the channels for low-carbon technology subsidies are limited), and the superimposed resource conditions are poor and the ability of traditional agriculture to resist risks is weak [87]; thus, it is easy to fall into a vicious cycle of increasing environmental vulnerability → sufficient investment in green technology → low ability to resist risks, and the CPRI strongly inhibits GAC.

Table 10.

Heterogeneity Test.

Regional heterogeneity: eastern, central, and western regions. The data in Columns (3) to (5) of Table 10 reveal that the inhibitory effect of the CPRI on GAC varies regionally, with a significantly negative coefficient in the eastern region at the 1% level. Despite the high level of agricultural modernization, exposure to climate risks remains high [88]. Moreover, the pressure to adjust the planting structure is caused by the scarcity of land resources under the Opinions on Preventing the Nongrain Conversion of Cultivated Land to Stabilize Grain Production [89]. The central and western regions show no significant impact. As a major traditional grain-producing area, central China benefits from the large-scale implementation and optimization of a drought-tolerant crop planting structure, as supported by the Opinions on Effectively Strengthening the Construction of High-Standard Farmland and Improving the National Food Security Guarantee Capacity, and exhibits high climate resilience [90]. Therefore, it can not only buffer the risk impact through internal resource allocation and external policy subsidies but also reserve space for investment in environmentally friendly and low-emission technology. In the western region, the coordinated development policy of ecological protection and agriculture in the 14th Five-Year Plan for the Development of the Western Region forms a natural ecological buffer mechanism, and the CPRI in this region indicates mostly slow-onset disasters. There is a lag effect in the transmission, resulting in the current period’s inhibition of GAC not reaching significance [91].

5.6. Spatial Spillover Effect

To accurately capture the spatial effect, a spatial distance matrix with high exogeneity is selected as the sovereign matrix, and robustness is assessed using the adjacency matrix. Prior to estimating the spatial econometric model, testing for spatial correlation is needed. Columns (1) to (2) of Table 11 provide the global Moran index of GAC under the two matrices, which pass the significance test (p < 0.1).

Table 11.

Global Moran’s Index of GAC.

5.7. Spatial Model Selection and Regression Results

To identify the spatial effect of the CPRI on GAC, the adaptive model is first screened using an LM test of the spatial lag and error terms. Columns (1) to (2) of Table 12 are based on the LM test results under the two matrices, respectively, and the SDM with fixed effects should be selected for estimation.

Table 12.

LM Test Results.

The data in Table 13 indicate that the CPRI exerts significant spatial spillover effects on GAC. In the spatial geographical distance matrix, the total effect of the CPRI is −0.3607 (p < 0.01); in the adjacency matrix, it is −0.092 (p < 0.01); and the indirect effect coefficients in the two matrices are significantly greater than the direct effect, indicating that the CPRI not only restricts local GAC but also exerts a considerable adverse effect on adjacent regions. Hypothesis H3 is therefore verified.

Table 13.

Regression Results of the SDM.

In terms of the total effect, the geographical distance matrix has a much larger absolute value than the adjacency matrix does, indicating that the impact of natural geographical associations, such as river basins and atmospheric circulation, on risk transmission is substantially greater than that of administrative boundary constraints. Owing to the network nature of the ecosystem, the CPRI spreads across domains through material and energy flows, forming regional development blocks [92]. In terms of direct effects, the CPRI changes the natural conditions of agricultural production through increasing temperature, abnormal precipitation, and extreme weather; it forms rigid constraints on the resource supply side and directly inhibits local GAC. The indirect effect highlights the dominance of geographical transmission, whose influence intensity is much greater than that of administrative proximity transmission, and the indirect effect is greater than the direct effect (interregional spillover is stronger than intraregional spillover). The impacts of the CPRI are significantly spatially correlated. Mechanisms such as pollutant diffusion and the interregional spread of diseases and pests driven by atmospheric circulation will rapidly transfer climate risks within a region to neighboring regions [93]. Simultaneously, modern agricultural regions have a close division of labor and cooperation, and the main grain-producing areas are strongly linked with processing areas and feed supply areas [94]. Fluctuations in the supply of agricultural products driven by the CPRI in a given region affect the downstream raw material supply through market transmission, increasing costs and reducing efficiency.

6. Discussion

By integrating the analysis framework of risk exposure, insurance regulation, and spatial correlation, this research examines the influence pathway and action limits of the CPRI on GAC. The core findings show that the CPRI directly exerts inhibitory effects through the following three channels: distorting production decisions, inhibiting technology adoption, and weakening ecological functions. This mechanism is consistent with existing evidence that climate change alters crop production conditions and induces risk-averse adjustments in agricultural input and management decisions [95]. Spatial econometric analysis indicates that the CPRI has a significant negative spillover effect, with its impact across regions being more intense than its local direct effect, thus challenging the traditional governance paradigm.

The study possesses notable strengths that underpin its contributions. It develops and empirically validates an integrated framework that simultaneously accounts for direct risk impacts, financial regulation via insurance, and spatial interdependencies—a combination seldom addressed in a unified manner. This approach not only provides empirical scale and specificity to theories of risk-averse behavior in the context of Chinese agriculture but also extends the theoretical motivation for designing financial instruments that serve dual goals of risk management and environmental governance. Methodologically, by capturing spatial dependence, it addresses the common limitation of analyses focusing solely on local effects, thereby offering robust evidence for regional collaborative governance theories.

The conceptual significance of this research lies in advancing the mechanistic understanding of the climate risk–green transition dilemma in agriculture. Our finding that short-term stability goals can lead to high-carbon lock-in provides empirical scale and specificity to theories of risk-averse behavior in the context of Chinese agriculture. This dilemma echoes recent findings on the uneven progress of low-carbon green agriculture across regions, where development trajectories are strongly shaped by spatial heterogeneity and structural constraints [96]. Furthermore, the conclusions reposition the policy function of INS. Moving beyond the established view of insurance for disaster reduction and income stabilization, our results demonstrate that INS acts as a positive moderator, mitigating climate risk impacts by guiding producers’ green practices through economic incentives. This finding extends the theoretical motivation for designing financial instruments that simultaneously serve risk management and environmental goals. Methodologically, by capturing the spatial dependence of CPRI, this study addresses the limitation of analyses focusing solely on local effects, thereby providing empirical evidence for regional collaborative governance theories.

At the practical level, this research provides a basis for creating differentiated policies. Heterogeneity analysis revealed that nonmajor grain-producing areas and the eastern region face more pronounced inhibitory pressure, which is closely related to differences in regional resource endowments and system resilience [97,98]. Comparable patterns have been identified in agri-food systems exposed to climate risks, where regional vulnerability and adaptive capacity jointly determine the severity of climate impacts [99]. Therefore, targeted measures are needed: high-exposure, low-resilience regions should strengthen innovation in terms of insurance instruments and the construction of climate resilience infrastructure; low-exposure, high-resilience regions should focus on ecological compensation and the promotion of green technologies. More importantly, the spatial spillover effect requires breaking through administrative boundaries and exploring ecological compensation and risk-sharing mechanisms based on natural geographical units to achieve synergy.

The findings of this study offer clear managerial implications for multiple stakeholders. For agricultural policymakers and government administrators, the results underscore the necessity of incorporating spatial spillover effects and insurance-mediated behavioral incentives into climate adaptation strategies. For insurance institutions and financial regulators, the confirmed moderating role of INS highlights the opportunity to develop innovative insurance products that are linked to green production practices, moving beyond traditional indemnity-based models. For farmers and agricultural cooperatives, the analysis of risk transmission channels (behavior distortion, technology inhibition) reveals the long-term economic and environmental benefits of adopting climate-resilient and low-carbon practices, guided by appropriate financial incentives.

Despite these contributions, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, provincial-level data cannot fully capture spatial heterogeneity at finer granularities, such as the city and county levels. Second, although the multidimensional path of insurance regulation has been proposed, it has not yet undergone empirical testing because of a lack of available data. In addition, the study focuses primarily on physical climate risks and does not fully incorporate interactions with transition risks.

Based on the findings, three policy recommendations are proposed to support agricultural green and low-carbon transformation under climate risk. First, regionally differentiated adaptation strategies should be implemented. High-risk, low-resilience regions should prioritize targeted subsidies and tax incentives for climate-resilient infrastructure—such as water-efficient irrigation systems and disaster prevention projects—and for adopting green technologies [100]. Low-risk, high-resilience areas should employ ecological compensation mechanisms to incentivize a shift toward low-carbon production. Second, agricultural insurance mechanisms should be innovated. Insurance institutions ought to develop products linked to green production practices and integrate meteorological warnings and disaster prevention services into contracts. Financial authorities can support such innovation through premium subsidies and by improving risk diversification mechanisms to advance multi-layered insurance models [101,102]. Finally, a cross-regional collaborative governance framework should be established. This includes creating a coordinated climate risk monitoring and early-warning platform based on natural geographical units such as watersheds and ecological regions, facilitated by higher-level agencies to enable data sharing and joint response [103,104]. Concurrently, promoting inter-regional ecological compensation and fiscal transfer systems, and exploring the establishment of a climate risk sharing fund, are essential to address governance fragmentation [105].

Future research can build on this work by addressing the noted limitations. Promising directions include using multiscale fusion data to reveal more detailed spatial heterogeneity, integrating micro surveys and behavioral experiments to empirically test the proposed pathways of insurance regulation, and constructing a composite assessment framework that incorporates both physical and transition risks to more comprehensively assess the combined influence of climate-related risks on agricultural systems.

7. Conclusions

On the basis of empirical analysis, this study reaches the following core conclusions: the CPRI poses a significant risk to GAC, directly inhibiting its progress by affecting producer behavior, technology adoption intention, and ecological background function. INS not only serves the traditional purpose of risk diversification but also positively influences the regulation of the relationship between the CPRI and GAC and can mitigate the adverse impact of the CPRI through financial compensation, credit enhancement, and behavior guidance. There is a notable variation in the impact of the CPRI across different regions. Nonmajor grain-producing regions and the eastern area encounter more challenges in adapting to climate risks because of differences in resilience. Critically, the empirical evidence confirms significant negative spatial spillover effects of CPRI, demonstrating that its impact is not confined locally but propagates across regions. This fundamental finding necessitates a paradigm shift in climate governance from fragmented, administrative-territorial management towards regionally coordinated strategies.

The integrated interpretation of these three findings provides a more systemic understanding of the climate risk–green transition dilemma in agriculture. The direct inhibitory pathways explain how climate shocks constrain transition efforts. The moderating role of INS identifies a key financial-institutional mechanism that can loosen this constraint. Finally, the evidence of spatial spillovers reveals the essential geographic dimension of the problem, demonstrating that impacts and solutions transcend local administrative boundaries. Collectively, this moves the analysis from examining isolated components to diagnosing a complex, linked system where biophysical risks, economic incentives, and geographic interdependencies interact.

In summary, this study systematically deciphers the mechanisms through which CPRI impedes GAC, validating the buffering function of insurance and the reality of cross-regional spillovers. The primary conclusion is that effectively navigating this dual challenge requires an integrated policy approach. Such an approach must simultaneously account for regional heterogeneity in risk exposure and resilience, strategically leverage and innovate financial instruments like insurance to align risk management with green incentives, and be fundamentally reoriented from fragmented, administrative-territorial management toward regionally coordinated governance strategies. Future research should build on this foundation by verifying the micro-behavioral mechanisms suggested here and by assessing the combined effects of multiple climate-related risks.

It is undeniable that the article has the following limitations. This study, based on provincial panel data for analysis, can clearly present the overall trend at the regional level, but it cannot deeply reveal the differentiated response mechanisms of different agricultural business entities within the province, such as the behavioral choice differences between small-scale farmers and new types of agricultural business entities when responding to climate risks. In addition, this study takes China as the research scenario. The relevant conclusions are drawn based on China’s unique agricultural policy environment, resource conditions, and development model. Given the differences among different countries in terms of institutional arrangements and agricultural production methods, the promotion and application of the research conclusions in other regions of the world need to be carefully considered and adaptively adjusted.

Author Contributions

Z.L.: Funding acquisition; Conceptualization; Methodology; Software; Supervision; Validation; Writing—original draft; Writing—review and editing. N.L.: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Software; Writing—original draft; Writing—review and editing. H.F.: Methodology; Formal analysis; Writing—original draft; Writing—review and editing. J.D.: Investigation; Software; Validation; Writing—original draft; Writing—review and editing. D.G.: Formal analysis; Validation; Writing—original draft; Writing—review and editing. M.X.: Data curation; Writing—original draft; Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund Project of China under Grant 23BGL203. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in FigShare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30703607.v1.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lee, H.; Calvin, K.; Dasgupta, D.; Krinner, G.; Mukherji, A.; Thorne, P.; Trisos, C.; Romero, J.; Aldunce, P.; Barrett, K. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Hunjra, A.I.; Battisti, E.; Zhu, Z. Technology lock-in or innovation breakthrough: Global energy mix transformation driven by technological innovation. Energy Econ. 2025, 149, 108817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Agrifood Systems: Global, Regional and Country Trends, 2000–2022 (FAOSTAT Analytical Brief Series No. 94); FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, B.; Wang, Y. Climate change and China’s food security. Energy 2025, 318, 134852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvam, A.P.; Al-Humairi, S.N.S. Environmental impact evaluation using smart real-time weather monitoring systems: A systematic review. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2025, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Guo, H. Development of Ecological Low-Carbon Agriculture with Chinese Characteristics in the New Era: Fea-tures, Practical Issues, and Pathways. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Shi, X.; Wang, Q. Assessing climate vulnerability in China’s industrial supply chains: A multi-region network analysis approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 490, 144718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, H.K.; Chauhan, P.K.; Seth, C.S.; Dubey, G.; Upadhyay, S.K. Mechanistic and future prospects in rhizospheric engineering for agricultural contaminants removal, soil health restoration, and management of climate change stress. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 927, 172116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terán, F.; Vives-Peris, V.; Gómez-Cadenas, A.; Pérez-Clemente, R.M. Facing climate change: Plant stress mitigation strategies in agriculture. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, N.; Zheng, X.; Han, X.; Li, X. Towards Sustainable Development: The Impact of Agricultural Productive Services on China’s Low-Carbon Agricultural Transformation. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, A.; Guo, L.; Li, H. Understanding farmer cooperatives’ intention to adopt digital technology: Mediating effect of perceived ease of use and moderating effects of internet usage and training. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2025, 23, 2464523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Xu, M.; Shi, L.; Lei, T. The criticality of environmental sustainability in agriculture: The decarbonization role of green finance in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 394, 127470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Boubaker, S.; Hunjra, A.I.; Yang, P. Impact of energy restructuring on green technology innovation in the context of climate policy uncertainty. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2025, 69, 101377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhuge, S.; Du, J.; Zhang, P.; Wang, X.; Liu, T.; Li, D.; Ma, H.; Li, X.; Nie, Y. The molecular mechanism by which heat stress during the grain filling period inhibits maize grain filling and reduces yield. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 15, 1533527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarin, A.S.; Islam, M.M.; Rahat, A.; Ahmed, S.; Ghosh, P.; Murata, Y. Drought stress tolerance in rice: Physiological and biochemical insights. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2024, 15, 692–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupngam, T.; Messiga, A.J. Unraveling the interactions between flooding dynamics and agricultural productivity in a changing climate. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Xu, J.; Zhang, X.; Pan, X. Efficiency and driving factors of agricultural carbon emissions: A study in Chinese state farms. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Guan, R. How Does Agricultural Mechanization Service Affect Agricultural Green Transformation in China? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Gao, J. The impact of green finance on agricultural pollution and carbon reduction: The case of China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Chen, Y.; Luo, J. Development of green and low-carbon agriculture through grain production agglomeration and agricultural environmental efficiency improvement in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 442, 141128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Liu, M.; Deng, N.; Cai, Z.; Zheng, R. Rural digital economy, agricultural green technology innovation, and agricultural carbon emissions—Based on panel data from 30 provinces in China between 2012 and 2021. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 33, 6347–6361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Gou, D.; Wu, Q.; Feng, H. Does the rural digital economy promote shared prosperity among farmers? Evidence from China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1649753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Min, J.; Luo, C.; Mao, X.; Liu, Z. The Impact of Digitalization on Agricultural Green Development: Evidence from China’s Provinces. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Feng, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, N.; Cao, F. Can the development of the rural digital economy reduce agricultural carbon emissions? A spatiotemporal empirical study based on China’s provinces. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 939, 173437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Lu, Z.; Wang, X.; Hou, G. The impact of land transfer on food security: The mediating role of environmental regulation and green technology innovation. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1538589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.-J.; Wang, L.; Xiang, F. The Effect of Agriculture Insurance on Agricultural Carbon Emissions in China: The Mediation Role of Low-Carbon Technology Innovation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Wang, Y. How does natural disasters affect China agricultural economic growth? Energy 2024, 296, 131096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Lu, Q. Does participation in digital supply and marketing promote smallholder farmers’ adoption of green agricultural production technologies? Land 2024, 14, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Ma, J.; Cai, S. Can crop insurance help optimize farmers’ decisions on pesticides use? Evidence from family farms in East China. J. Asian Econ. 2024, 92, 101735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Liu, J.; Wan, S.; Zheng, H.; Chen, S. Agricultural insurance and rural revitalization—An empirical analysis based on China’s provincial panel data. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1291476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, T.; Quan, T. A Study of the Spatial Mechanism of Financial Agglomeration Affecting Green Low-Carbon Development: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahasan, B.C.; Pinar, M. Climate change and spatial agricultural development in Turkey. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2023, 27, 1699–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Lu, Z. Achieving green agricultural development: Analyzing the impact of agricultural non-point source pollution on food security and the regulation effect of environmental regulation. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0324899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; He, Z.; Deng, Z.; Poddar, S. Analysis of Spatiotemporal Disparities and Spatial Spillover Effect of a Low-Carbon Economy in Chinese Provinces Under Green Technology Innovation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wu, X.; Liang, R. Study on the spatial spillover effect of agricultural carbon emissions in Beibu Gulf city cluster and its influencing factors. Econ. Manag. Innov. 2025, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaekeh, S.M.; Shiva, L.; Safaie, A. Investigating the economic impact of climate change on agriculture in Iran: Spatial spillovers matter. Agric. Econ. 2024, 55, 433–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargani, G.R.; Jiang, Y.; Joyo, M.A.; Liu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Chandio, A.A. No farmer no food, assessing farmers’ climate change mitigation and adaptation behaviors in farm production. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 100, 103035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Huang, Y. Sustainable agriculture in the face of climate change: Exploring farmers’ risk perception, low-carbon technology adoption, and productivity in the Guanzhong Plain of China. Water 2023, 15, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, U.A.; Bhatti, M.A.; Tang, H.; Syam, M.S.; Awwad, E.M.; Sharaf, M.; Ghadi, Y.Y. Global production patterns: Understanding the relationship between greenhouse gas emissions, agriculture greening, and climate variability. Environ. Res. 2024, 245, 118049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgina Menon, K.; Venkateshwar Reddy, K.; Boje Gowd, B.H.; Paul Vijay, P.; Jhansi, R. Pesticides and climate change feedback loop. In The Interplay of Pesticides and Climate Change: Environmental Dynamics and Challenges; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 129–147. [Google Scholar]

- Han, C.; Lyu, J.; Zhong, D. The impact of financial support and innovation awareness on farmers’ adoption of green production technology. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 79, 107259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Gui, Y.; Du, Y.; Wen, J. Research on the optimization of supply chain decisions for green agricultural products based on farmers’ risk preferences and disaster year subsidies. Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernacchi, C.J.; Long, S.P.; Ort, D.R. Safeguarding crop photosynthesis in a rapidly warming world. Science 2025, 388, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daunoras, J.; Kačergius, A.; Gudiukaitė, R. Role of soil microbiota enzymes in soil health and activity changes depending on climate change and the type of soil ecosystem. Biology 2024, 13, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.V.; Paramesh, V.; Arunachalam, V.; Das, B.; Ramasundaram, P.; Pramanik, M.; Sridhara, S.; Reddy, D.D.; Alataway, A.; Dewidar, A.Z. Farmers’ perception and efficacy of adaptation decisions to climate change. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xu, N.; Zhang, W.; Ning, X. Can agricultural low-carbon development benefit from urbanization? Empirical evidence from China’s new-type urbanization pilot policy. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 435, 140388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, D.; Bahinipati, C.S. Crop-insurance adoption and impact on farm households’ well-being in India: Evidence from a panel study. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2025, 30, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Jia, C.; Su, L. The impact of digital agricultural insurance on farmers’ fertilizer reduction technology adoption: Evidence from China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2025, 17, 379–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odunaiya, O.G.; Okoye, C.C.; Nwankwo, E.E.; Falaiye, T. Climate risk assessment in insurance: A USA and Africa review. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2024, 11, 2072–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Hamid, Z.; Mahboob, F.; Rehman, K.U.; Ali, M.S.E.; Senkus, P.; Wysokińska-Senkus, A.; Siemiński, P.; Skrzypek, A. Causal linkage among agricultural insurance, air pollution, and agricultural green total factor productivity in United States: Pairwise Granger causality approach. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liao, H.; Fang, L.; Guo, G. Quantitative study on agricultural premium rate and its distribution in China. Land 2023, 12, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Shu, Y.; Cao, H.; Zhou, S.; Shi, S. Fiscal policy dilemma in resolving agricultural risks: Evidence from China’s agricultural insurance subsidy pilot. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, L.; Wang, Y.; Mao, H. Does agricultural insurance drive variations in carbon emissions in China? Evidence from a quasi-experiment. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2023, 32, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.; Maher, B.; Ndlovu, Q.; Stoppa, A.; Hoveka, C. Namibia Agriculture Disaster Risk Finance and Insurance Diagnostic (English). In Equitable Growth, Finance and Institutions Insight; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tobler, W.R. A computer movie simulating urban growth in the Detroit region. Econ. Geogr. 1970, 46, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; He, D.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, Y. Analysis on the spatiotemporal patterns and driving mechanisms of China’s agricultural production efficiency from 2000 to 2015. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2020, 120, 102909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zeng, C.; Song, Y.; Guo, L.; Liu, W.; Zhang, W. The spatial effect of administrative division on land-use intensity. Land 2021, 10, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Yu, L.; Zhu, Y. Environmental effects and their causes of agricultural production: Evidence from the farming regions of China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 144, 109549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Tang, Z. Climate risk spatio-temporal evolution, spatial network structure and consequence analysis in China. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 11491–11522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, R.; Sun, D.; Sun, W. Spatiotemporal variations in grain yields and their responses to climatic factors in Northeast China during 1993–2022. Land 2025, 14, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, E.; Chen, G. Spatiotemporal variation and influencing factors of grain yield in major grain-producing counties: A comparative study of two provinces from China. Land 2023, 12, 1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Li, M.; Lenzen, M.; Fry, J.; Liyanapathirana, N.; Beyer, K.; Boylan, S.; Lee, A.; Raubenheimer, D.; Geschke, A. Impacts of climate change and extreme weather on food supply chains cascade across sectors and regions in Australia. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Bi, C.; Yan, J. Extreme climate risk and energy consumption structure. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 80, 107434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Ren, X.; Wang, Y.; Lei, X. Climate risk and corporate bond credit spreads. J. Int. Money Financ. 2025, 154, 103297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Zheng, P.; Xie, Y.; Du, Z.; Li, X. Research on the impact of climate change on green and low-carbon development in agriculture. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 170, 113090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Tian, H.; Liu, X.; You, J. Transitioning to low-carbon agriculture: The non-linear role of digital inclusive finance in China’s agricultural carbon emissions. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Han, X.; Liu, W.; Ni, C.; Wu, S. Comprehensive assessment system and spatial difference analysis on development level of green sustainable agriculture based on life cycle and SA-PP model. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 139724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Huang, M.; Bai, Y. Promoting green development of agriculture based on low-carbon policies and green preferences: An evolutionary game analysis. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 6443–6470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; He, J.; Huang, Z. Innovation, natural resources abundance, climate change, and green growth in agriculture. Resour. Policy 2023, 85, 103970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Adamowski, J.F.; Wu, M.; Zhang, P.; Yue, Q.; Cao, X. An integrated framework for improving green agricultural production sustainability in human-natural systems. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 945, 174153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Song, M.; Dou, C. Evaluation of food security in different grain functional areas in China based on the entropy weight extended matter element model. Foods 2025, 14, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreeni, K.R.; Vasudevan, N. Impact of climate fluctuations on paddy yield: A case study in Kollengode village, India. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 559, 01015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]