Abstract

The aim of this study is to conduct a scoping review of the literature on the marketing environment and Fair Trade in the coffee industry, identifying its contribution to organizations and society. Quantitative studies were selected from databases such as Web of Science and Scopus, following a selection process aligned with the PRISMA methodological guidelines and establishing eligibility criteria for articles using the PICOS strategy. To understand the effects of macromarketing, strategic marketing, and operational marketing on the development of the Fair Trade coffee market, the results demonstrate that marketing plays a significant role in the market’s growth. Specifically, marketing is crucial in communicating the value of Fair Trade, raising consumer awareness, and supporting the economic well-being of coffee producers. Ethical consumption and branding strategies are essential for positioning Fair Trade coffee in competitive markets. However, further studies are needed to corroborate these findings and provide more up-to-date perspectives.

1. Introduction

Fair Trade has established itself as a disruptive approach to market development, balancing traditional trade dynamics by promoting fairer conditions for small producers and fostering social and environmental sustainability [1,2,3]. This model challenges conventional trade structures by ensuring fair prices, reducing economic inequality, and improving labor conditions in sectors such as coffee [4,5]. Its impact has generated greater global awareness of fairness in supply chains, where consumers are willing to pay a higher premium for ethical products. Fair trade International reported [6] that more than two million farmers and workers in 68 countries have improved their livelihoods in a sustainable way, addressing issues such as human rights and gender equity [6]. In this context, marketing plays a crucial role in connecting Fair Trade values with consumers, making it possible to communicate the added value of these products and differentiate them from conventional ones [7]. This relationship is key because marketing not only positions Fair Trade products in the market but also educates consumers about the positive impacts of their purchases, incentivizing ethical consumption [8,9]. In addition, marketing helps to bridge the gap between the intentions and actual actions of ethical consumers, who require clear information to opt for sustainable products [10,11]. To analyze this relationship, three dimensions need to be addressed: Macromarketing (MM), strategic marketing (SM), and operational marketing (OM).

1.1. Macromarketing

Macromarketing focuses on analyzing systems in a broad context, considering how marketing decisions impact society, the environment, and the global economy [12,13]. Unlike micromarketing, which focuses on specific tactics implemented by organizations and studies consumer behaviors, macromarketing addresses more complex issues, such as sustainability and social welfare [14,15,16]. This approach promotes more ethical marketing by considering the impact of business decisions not only on companies but also on communities and the environment [17,18]. In Fair Trade, macromarketing addresses global inequalities by regulating social, environmental, and economic aspects in international markets [4]. In Latin America, one of the main industries that has incorporated this way of articulating business is the coffee industry [19]. Fair Trade initiatives in the coffee industry have improved the welfare of producers by offering more equitable trading conditions, guaranteeing a minimum price to producers. This additional income has improved living conditions in farming communities and, in some cases, has allowed them to resist pressure from large industries that threaten their land [19]. One example is the case of Peru, where Fair Trade-certified farmers have increased their income thanks to better prices on the international market, which has allowed their children to have greater access to education. In Mexico, additional income has also facilitated school attendance, although educational attainment depends on local infrastructure, and in Nicaragua, although improvements in health have been limited, Fair Trade has provided certain economic benefits that improve living conditions and access to education [20]. However, other studies have shown that much of the value generated in the supply chain remains with retailers and processors in consuming countries, reducing the direct economic impact on producers [21].

1.2. Strategic Marketing

Strategic marketing refers to the set of integrated decisions that an organization makes in terms of products, markets, and marketing resources to generate and deliver value to customers, which is essential to achieve its objectives [22]. Although there are different approaches to its classification and functions, there is consensus that from the organizational focus centered on marketing decisions, its function encompasses understanding consumer behavior, segmentation and targeting strategies, branding strategy decisions, analysis of the environment and competition, and ensuring the organization’s strategic compliance [22,23]. Its role is key for Fair Trade organizations, as it facilitates market segmentation, allowing the identification of consumers who value ethical and sustainable products [7,24,25]. Coffee companies involved in Fair Trade target ethical consumers, motivated by moral and environmental reasons [10,26]. Studies such as [27] analyze how ethical values influence the purchase of Fair Trade coffee, while research by authors [28] features the use of authenticity as a positioning strategy in the competitive coffee market. In addition, ref. [19] examines how personal values impact the willingness to pay more for ethical products in the coffee industry, connecting strategic marketing with ethical consumer behavior. Another important factor in companies related to Fair Trade is differentiation, which is fundamental to positioning themselves in areas of sustainability, as has occurred massively in Western Europe, where Fair Trade labeling has promoted an increase in ethical consumption [29].

1.3. Operational Marketing

Operational marketing, based on the 7P’s (price, promotion, product place, people, processes, and physical evidence), refers to the tactics to be executed to achieve the proposed objectives of the organization [30]. In the case of product tactics, they must meet the expected quality standards and communicate their contribution to sustainability [31]. Price tactics should reflect the added value that consumers are willing to pay for improving the welfare of producers [32,33], Considering relevant cultural aspects, such as the tension between individualism and communitarianism, they significantly influence consumption decisions, particularly in the evaluation of ethical products that aim to generate a positive social impact [33]. Place tactics should ensure product accessibility, while promotion should effectively communicate the benefits derived from Fair Trade. Physical evidence, such as labeling, should build trust by ensuring ethical standards [30]. The process is key to transparency in the supply chain, and people, both employees and consumers, are critical to maintaining trust in the brand [34]. In the coffee industry, these elements have proven to be crucial in aligning ethical products with consumer expectations. Communication campaigns and labeling have reinforced consumer trust in fair products [35,36], while packaging and the organization of collective actions have been essential in highlighting the transparency and sustainability of brands [19,27], Highlighting that consumers may place greater value on distribution strategies and the credibility of the label issuer when making purchase decisions for ethical products, with fair trade labels being the most preferred [37].

What are the main thematic areas addressed by marketing (macromarketing, strategic marketing, and operational marketing) in the literature on Fair Trade in the coffee industry? How do these areas contribute to the development of organizations and society? And what is the geographical scope of the reported cases, considering the distinction between core and peripheral countries in terms of development? The aim of this study is to conduct a scoping review of the literature on marketing (macromarketing, strategic marketing, and operational marketing) in the context of Fair Trade in the coffee industry, to identify its contribution to the development of organizations and society, and to analyze the geographical scope of the reported cases, considering the distinction between core and peripheral countries in terms of development.

2. Materials and Methods

This work about marketing components in Fair Trade coffee studies uses the scoping review, a specific typology within review studies [38]. A Scoping Review is a systematic review that maps the scope and nature of the literature on a particular topic, aiming to identify knowledge gaps and areas that require further research. While it does not conduct an exhaustive assessment of study quality, it provides a general evaluation of the studies’ quality to offer a preliminary overview. It is useful in the early stages of a project to understand the broader context and determine whether a more in-depth review or additional studies are needed. Key characteristics include identifying the relevant literature, defining inclusion and exclusion criteria, and including a wide range of studies without a detailed analysis of methodological quality [38]. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [39], in particular PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR), Provide specific guidelines for conducting and reporting scoping reviews, its main characteristics include the following: a clear definition of the review’s objective, the identification of research questions, the selection of relevant studies using inclusion and exclusion criteria, a description of the methodology used for data collection, and a general evaluation of the quality of the included studies. Additionally, it focuses on presenting the results transparently, describing the key characteristics and findings of the studies, without conducting a thorough assessment of methodological quality [40], and the PICOS (Participants, Interventions, Comparators, Outcomes, and Study Design) strategy to establish eligibility criteria for articles. This methodology is a structured approach used to define eligibility criteria for studies in systematic reviews, particularly in health-related research. The acronym stands for Participants, Interventions, Comparators, Outcomes, and Study Design. It helps to clarify key aspects of the studies to include the following: the characteristics of the participants, the interventions being assessed, the comparators or control groups, the outcomes measured, and the types of study designs considered. This framework ensures that the review focuses on relevant and specific research, facilitating the comparison of findings across studies [41], whose protocol has been registered in Zenodo [42], under the modified PROSPERO format recommended by Tricco et al. [40]. On the other hand, we have used the MMAT (Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool), an evaluation tool designed to assess the quality of studies that employ both qualitative and quantitative methods in research. This tool is specifically designed for studies that combine qualitative and quantitative methods, providing a framework to evaluate the quality of the different components of the study in an integrated manner. The MMAT assesses aspects such as the coherence and validity of the methods used, the representativeness of the sample, the adequacy of the data collection techniques, and the integration of the results. It is particularly useful in systematic reviews of studies that employ qualitative and quantitative methods, as it allows for a more comprehensive evaluation of the quality of the research [43].

According to the current checklist of the PRISMA-ScR guidelines [40], the following quality steps for systematic reviews were verified according to these items: (1) title, (2) structured summary, (3) rationale, (4) objectives, (5) protocol and registration, (6) eligibility criteria, (7) information sources, (8) search, (9) selection of sources of evidence, (10) data charting process, (11) data items, (12) critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence, (13) synthesis of results, (14) selection of sources of evidence, (15) characteristics of sources of evidence, (16) critical appraisal within sources of evidence, (17) results of individual sources of evidence, (18) synthesis of results, (19) summary of evidence, (20) limitations, (21) conclusions, and (22) funding. The initial search for articles was performed using bibliometric procedures [44].

2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

We used a set of articles from two databases, with equivalent search vectors and without additional restrictions (such as period of years or types of documents), reporting double indexing and both report citations, relying on the Web of Science—Core Collection (WoSCC) [45] and Scopus [46], selecting articles published in journals indexed in these databases, from a search vector on Fair Trade Coffee in WoSCC: {TS = (Fair NEAR/0 Trade NEAR/0 Coffee)}, and Scopus: {TITLE-ABS-KEY (Fair W/0 Trade W/0 Coffee)}. We used the thematic search tag TS (searching simultaneously on title, abstract, author keywords, and Keywords Plus®), and the word proximity operator (NEAR/0) that simultaneously incorporates contiguous words that make up the concept of Fair Trade coffee. Equivalently in Scopus, we searched in Title, Source title, Author Keywords, and Index Keywords, and we used the word proximity operator (W/0). Providing coverage for the PRESS 2015 guideline statement [47].

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The selection of articles was based on the following eligibility criteria: target population (participants), interventions (methodological techniques), elements of comparison of these studies, outcomes of these studies, and study designs. In this context, the coffee consumers, coffee farmers, coffee traders, and communities near coffee plantations were selected, with a focus on the theoretical beneficiaries of Fair Trade coffee. These groups are directly impacted by Fair Trade practices and marketing decisions in the coffee industry, which allows for an analysis of their behavior, needs, and benefits. Questionnaires and quantitative methods were applied, following standard procedures under the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool, enabling the collection of measurable, comparable, and objective data on the effects of marketing on various stakeholders in the coffee industry, thus facilitating the identification of patterns and trends at a large scale. The focus was placed on Macromarketing (MM), Strategic Marketing (SM), and Operational Marketing (OM), as well as the research methods used, to compare different marketing strategies at the macro, strategic, and operational levels, providing an integrated view of how marketing practices affect coffee markets and helping to understand the impact of Fair Trade. The results of SM, OM, and MM, such as consumer behavior, segmentation strategies, brand decisions, business environment analysis, pricing, promotion, product placement, and SDG classification, allow for a detailed evaluation of marketing effects on the coffee industry from a strategic and operational perspective, linking the study to global sustainability objectives. Finally, quantitative studies were included, and evaluated with the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool, as they provide accurate and comparable data on marketing effects, facilitating comparisons between different interventions and their impact on the coffee industry. Although qualitative studies are valuable for exploring perceptions and experiences, especially when subjectivity is permitted by the underlying research paradigms, in the context of this analysis, which aims to provide a preliminary approach and comparison between studies, the decision was made to focus on quantitative studies. This choice is justified by the ability of quantitative studies to generate more objective, measurable, and comparable data, enabling a more generalizable evaluation. Since this is a preliminary investigation, the need to establish clear comparisons and obtain replicable results requires an approach that can provide a solid foundation for generalizing conclusions on a broader scale, something that quantitative studies, through their numerical structure and statistical analysis, facilitate more efficiently. This approach ensures that the studies selected align with the research objectives and provide comparable and measurable data, which is essential for drawing general conclusions applicable to the Fair Trade coffee industry. (the criteria of the PICOS strategy as shown in Table 1).

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria using.

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

As a first step, according to the search strategy, a first extraction of documents from WoSCC and Scopus databases was carried out on 27 August 2024.

Then, duplicates were manually removed. Then, the titles and abstracts of articles were checked for relevance by two researchers (A.V.-M., and N.C.-B.). Subsequently, they independently reviewed the full texts of potentially eligible articles. Any disagreements were discussed with a third researcher (J.M.-L.) until a consensus was reached.

According to the eligibility criteria declared in Table 1, we then excluded letters, editorial materials, reviews, and documents containing only abstracts. Articles that were not related to the concepts of marketing components in Fair Trade coffee were excluded (this process was repeated in the full document detail review). In addition, articles not written in English were non-excluded (other full-length documents written in French and Spanish).

The data items in phase one correspond to 174 fields per record in WoSCC and 158 fields per record in Scopus, as detailed below. WoSCC: (1) Authors, (2) Book Authors, (3) Book Editors, (4) Book Group Authors, (5) Author Full Names, (6) Book Author Full Names, (7) Group Authors, (8) Article Title, (9) Source Title, (10) Book Series Title, (11) Language, (12) Document Type, (13) Conference Title, (14) Conference Date, (15) Conference Location, (16) Conference Sponsor, (17) Conference Host, (18) Author Keywords, (19) Keywords Plus, (20) Abstract, (21) Addresses, (22) Affiliations, (23) Reprint Addresses, (24) Email Addresses, (25) Researcher Ids, (26) ORCIDs, (27) Funding Orgs, (28) Funding Name Preferred, (29) Funding Text, (30) Cited Reference Count, (31) Times Cited, WoS Core, (32) Times Cited, All Databases, (33) 180 Day Usage Count, (34) Since 2013 Usage Count, (35) Publisher, (36) Publisher City, (37) Publisher Address, (38) ISSN, (39) eISSN, (40) ISBN, (41) Journal Abbreviation, (42) Journal ISO Abbreviation, (43) Publication Date, (44) Publication Year, (45) Volume, (46) Issue, (47) Special Issue, (48) Start Page, (49) End Page, (50) Article Number, (51) DOI, (52) DOI Link, (53) Book DOI, (54) Early Access Date, (55) Number of Pages, (56) WoS Categories, (57) Web of Science Index, (58) Research Areas, (59) IDS Number, (60) Pubmed Id, (61) Open Access Designations, (62) Date of Export, (63) UT (Unique WOS ID), and (64) Web of Science Record [45]. Additionally, Scopus: (1) Authors, (2) Author full names, (3) Author(s) ID, (4) Title, (5) Year, (6) Source title, (7) Volume, (8) Issue, (9) Art. No., (10) Page start, (11) Page end, (12) Page count, (13) Cited by, (14) DOI, (15) Link, (16) Affiliations, (17) Authors with affiliations, (18) Abstract, (19) Author Keywords, (20) Index Keywords, (21) Molecular Sequence Numbers, (22) Chemicals/CAS, (23) Tradenames, (24) Manufacturers, (25) Funding Details, (26) Funding Texts, (27) References, (28) Correspondence Address, (29) Editors, (30) Publisher, (31) Sponsors, (32) Conference name, (33) Conference date, (34) Conference location, (35) Conference code, (36) ISSN, (37) ISBN, (38) CODEN, (39) PubMed ID, (40) Language of Original Document, (41) Abbreviated Source Title (42) Document Type, (43) Publication Stage, (44) Open Access, (45) Source, and (46) EID [46].

2.4. Quality Assessment, Risk of Bias, and Results Synthesis

In the first phase of quality assurance, a critical evaluation of the articles included was carried out, using the focus on marketing components in Fair Trade coffee as a discriminant comparator, being an outcome of interest to observe the diversity of the thematic categories selected.

The risk of bias in the included studies will be assessed according to Methley et al. [41] in the case of theoretical articles and the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) scale will be used for quantitative, qualitative, and mixed studies [48]. The MMAT scale is a valid measure of the methodological quality of the article. Two authors will review the studies independently, and a third author will be incorporated to settle tiebreakers.

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), a checklist used in systematic reviews based on synthesis of qualitative and quantitative evidence, includes criteria for the evaluation of mixed studies; it defines the study category, and 7 items are applied according to a score from zero to one, to obtain a final percentage mean. Studies are considered as high quality >75%, moderate quality 50–74%, and low quality <49%. Studies with values below 50% were excluded from the category analysis and discussion [49].

As a synthesis of the results, we have used comparative elements of the selected articles, contributing to the process of establishing categories of study on the marketing components of Fair Trade coffee. As outcomes, we have focused on the constructs studied and the items that compose or disaggregate these constructs.

3. Results

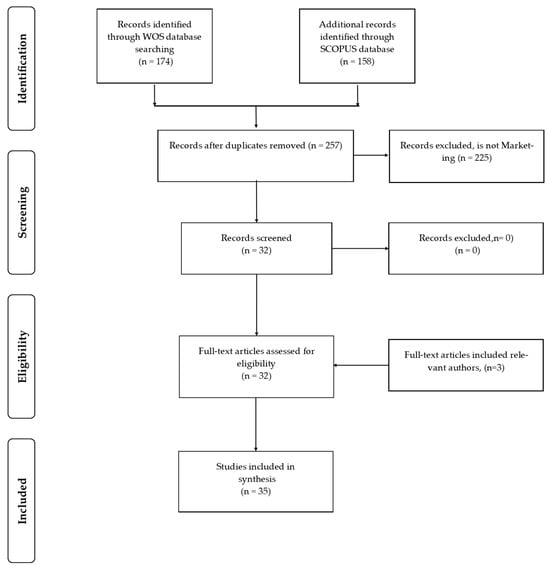

Firstly, the result of the PRISMA analysis summary provided a total of 174 records identified through the Web of Science (WOS) database and 158 additional records obtained from the SCOPUS database, resulting in 257 unique records after duplicates were removed. During the screening process, 225 records were excluded for not being related to marketing and fair trade coffee, leaving a total of 32 records for further evaluation. Subsequently, 32 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, and we included three articles that, although they were not in our database, were relevant to the analysis. Then, we applied the MMAT review methodology to all the articles to ensure the quality of the studies, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).

3.1. Results of the Quantitative Criteria in the MMAT Evaluation

The 35 articles were assessed using criteria to ensure transparency in their methodological development for quantitative studies. Initially, two general questions were addressed. S1. Are the research questions clearly defined? S2. Does the collected data allow for addressing research questions? Following this, the questions for Quantitative Non-randomized studies were applied—3.1. Are the participants representative of the target population? 3.2. Are the measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)? 3.3. Are the outcome data complete? 3.4. Are confounders accounted for in the design and analysis? 3.5. Was the intervention (or exposure) administered as intended during the study period? For Quantitative Descriptive studies, the following questions were applied—4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? This approach ensures a comprehensive and rigorous evaluation of the studies, meeting necessary methodological standards. The results of the MMAT application can be observed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Application of the MMAT methodology and Criteria.

3.2. Results from the Description of the Selected Articles

The 35 selected articles span a publication range from 2005 to 2023, reflecting the growing academic interest in the impact of Fair Trade in the coffee industry. Published in high-impact journals such as Food Research International, Sustainability, and Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, these studies stand out for their interdisciplinary focus. They address topics such as consumer preferences for specialty coffee [50], personal values and willingness to pay for Fair Trade coffee in South Africa [51], ethical consumer motivations [52], and the subjective quality of life of producers in Latin America [20,54]. Additionally, they include research on the benefits of Fair Trade on producers’ income, education, and health [20] and the engagement of producers with cooperatives in Mexico [58].

Other studies analyze ethical consumption from niche to mainstream [78], value capture through market disintermediation [59], and market efficiency in Sweden [75]. There are also studies on willingness to pay for organic and Fair Trade coffee in Belgium [74].

Other articles explore ethical product demand from different perspectives, such as an analysis of young consumers’ preference for Fair Trade coffee [72], motivational factors for purchasing Fair Trade products [65], comparative efficiency of specialty coffee retailers [66], and the impact of Fair Trade on smallholder vulnerability in Nicaragua [67]. Local market issues are also addressed, such as consumer preference for locally grown coffee in Taiwan [68], and the effectiveness of Fair Trade certifications in Sweden [75].

Additionally, studies on willingness to pay for Fair Trade coffee in China [80], consumer preferences for ethically labeled product marketing [37], and demand for ethical products based on cultural worldviews [33] are included in this body of research. Other studies, such as the one on the effectiveness of Fair Trade in stabilizing agricultural commodity markets in the Czech Republic [77], complement the discussion on the impact of Fair Trade in the coffee industry.

This overview reflects the shift from a focus on benefits for producers to a more consumer-oriented analysis, promoting ethical values. The evolution of these studies highlights the importance of understanding both market dynamics and consumer motivations in the context of Fair Trade products. A preliminary description of the selected articles can be seen in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characterization of thirty-five selected articles according to PRISMA-ScR guidelines and MMAT.

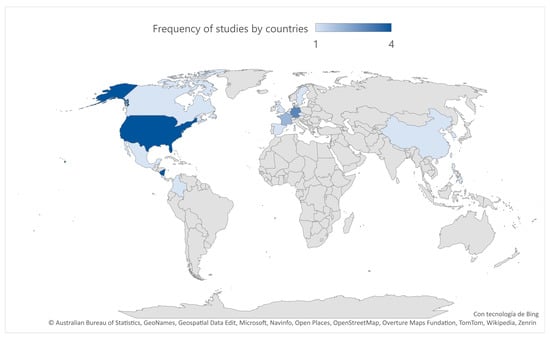

The geographic distribution of studies reveals a concentration of research in specific countries, reflecting the focal points of Fair Trade coffee’s impact and consumer behavior. The United States stands out with the highest frequency of studies, highlighting its significant role as a consumer market and its emphasis on ethical consumption and sustainability in coffee production. Latin America, particularly Nicaragua, Peru, and Guatemala, is another key region, with multiple studies addressing the socioeconomic effects of Fair Trade on coffee producers. These countries are pivotal due to their central role in global coffee production and their reliance on Fair Trade systems to improve producer outcomes. Additionally, countries such as Costa Rica, Honduras, and the Philippines contribute to the understanding of the market’s efficiency, sustainability, and social capital dynamics among producers.

The map visually represents the frequency of studies conducted in each country, with varying shades of blue indicating the concentration of research. Lighter shades represent countries with a single study, such as Germany, South Korea, Belgium, and the Czech Republic, reflecting emerging or specialized research areas. These studies primarily focus on consumer preferences, ethical considerations, and market behaviors in non-coffee-producing countries. Darker shades highlight countries with higher frequencies of studies, such as the United States and the combined regions of Nicaragua, Peru, and Guatemala, which together account for five studies. This gradient illustrates the intensity of academic focus on regions, emphasizing the dual importance of consumer markets in developed countries and production regions in developing nations.

Furthermore, countries like South Africa, Mexico, New Zealand, and Taiwan contribute to the diversity of perspectives, focusing on unique consumer motivations and market strategies. South Africa, for instance, explores willingness to pay for Fair Trade coffee in a different consumer context, while New Zealand focuses on adding value in cafes through Fair Trade coffee. This geographic distribution demonstrates both the global reach of Fair Trade coffee research and the need for more extensive exploration in underrepresented regions, such as countries in Africa or Southeast Asia, to gain a comprehensive understanding of its impact, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Countries studies in selected articles.

3.3. Results Studies Macromarketing

Three studies were conducted by [20,54,60] in the coffee-producing countries of Nicaragua, Peru, and Guatemala. One additional study, by [58], was conducted in Mexico. These studies focused on quantitative descriptive methods, using self-report questionnaires to assess the perception of improvements in quality of life across various dimensions. Arnould et al. [20], and Geiger-Oneto et al. [54] analyzed the impact of Fair Trade on the quality of life for coffee producers in Nicaragua, Peru, and Guatemala, highlighting the role of cooperatives in enhancing producers’ well-being and examining the broader social and economic effects on global relationships between producers and consumers. Their findings revealed that farmers in Fair Trade cooperatives reported a higher quality of life, improved income, and a more optimistic outlook for their families’ future [20] explored whether Fair Trade fulfills its core value proposition by improving the income, education, and health of small coffee producers in these same countries, further examining its social and economic impact and connecting consumers and producers within a global ethical trade system [58] studied the factors influencing coffee producers’ engagement with cooperatives in Mexico, using fractional probit regression to analyze variables such as price uncertainty, trust, education, and relational commitment. Their results demonstrated that engagement with cooperatives positively impacts producer outcomes and income stability, showcasing the crucial role of cooperatives in enhancing the financial security and development of producers.

3.4. Results Studies Strategic Marketing

The research included in the strategic marketing category addresses various factors such as consumer behavior, positioning strategies, and the role of values in the decision-making process for Fair Trade coffee [50,51] emphasizing that personality traits like conscientiousness and extraversion significantly influence consumers’ willingness to pay higher prices for sustainable and Fair Trade products. According to the findings of [55], the primary motivations for purchasing Fair Trade coffee include the improvement of workers’ and farmers’ wages and working conditions. Furthermore, Hwang et al. [57] argue that moral emotions and self-fulfillment, driven by empathy or narcissism, are key motivations for ethical consumers, with the emotional drive often leading to greater satisfaction.

In addition, Cailleba et al. [71] focus on how personal values, particularly humanitarianism, influence consumer preferences for Fair Trade coffee. They found that individuals with higher humanitarian values were more willing to pay a premium for Fair Trade products. Moreover, studies by Sepúlveda et al. [69], and Lee et al. [70] highlight that consumers’ ethical values, particularly the importance of environmental and social concerns, significantly impact their purchasing decisions. This is especially true in contexts where Fair Trade certifications are prominently displayed and communicated effectively, influencing consumer trust and perception of value.

In terms of market segmentation, Robichaud et al. [72] point out that young consumers, particularly Gen Z, show different purchase intentions compared to older generations. They suggest that the role of social media and peer influence contributes to their motivations for buying Fair Trade coffee, as these factors align with their self-image and social identity [78] also discuss the importance of market positioning strategies in attracting these younger consumers, noting that Fair Trade certifications and the story behind the product play a crucial role in shaping perceptions and willingness to pay.

Furthermore, studies like those by Schollenberg [75], and De Ferran [79] explore how the integration of ethical considerations into marketing strategies can enhance the marketability of Fair Trade coffee. However, they note challenges related to price sensitivity and the need for clear communication of the social and environmental benefits associated with these products. This emphasizes the necessity for businesses to balance ethical messaging with practical considerations such as price and product quality to meet consumer expectations.

These findings emphasize the critical role of understanding consumer behavior, segmentation strategies, and the influence of ethical values on purchasing decisions. However, they also point out the gaps in connecting the strategic narratives used in marketing campaigns with the actual impacts on the communities involved in Fair Trade systems, suggesting a need for more comprehensive research in this area.

3.5. Results Studies Operating Marketing

Studies within the operational marketing field examine how promotional tactics, pricing strategies, and efficiency impact consumer decisions regarding Fair Trade coffee. Chen et al. [62] found a significant positive relationship between the attractiveness and reliability of celebrity endorsements and consumers’ willingness to purchase Fair Trade coffee. However, they also observed that promotional tactics like “buy one, get one free” coupons were more effective at increasing purchase intentions than celebrity endorsements, brochures, or packaging [65] used a theoretical model to assess how market conditions influence the welfare of coffee farmers in Fair Trade systems. Their results indicated that while Fair Trade improves the welfare of farmers, it still falls short of the welfare that could be achieved under perfect competition [66] applied data envelopment analysis (DEA) to evaluate the efficiency of seven specialty coffee retailers, revealing that those committed to socially responsible practices, like Fair Trade, performed significantly better than those that were not. Interestingly, their research found that higher purchase prices for Fair Trade coffee did not harm retailer efficiency; rather, the increased revenue from the positive brand image associated with social responsibility helped offset the higher costs.

In Sweden, Schollenberg [75] found that consumers were willing to pay a premium of up to 38% for Fair Trade-certified coffee, showing a strong public awareness of Fair Trade labels. However, the study pointed out that much of the price premium ended up benefiting roasters and supermarkets rather than the coffee producers themselves [76] also emphasized the importance of product information, noting that consumers placed greater value on general information over specific product details. Price, as well as the quality of organic certifications, were key drivers in the purchasing decisions for Fair Trade coffee. This underscores the importance of effective communication strategies for coffee marketers, ensuring that consumers are well-informed about both the product quality and the ethical values it represents.

These findings underline how essential strategic marketing elements, such as pricing, promotions, and understanding consumer behavior, are to the success of Fair Trade coffee in various markets. However, they also highlight the ongoing challenge of aligning marketing strategies with actual impacts on producer communities, pointing to the need for a more equitable distribution of value across the supply chain. This systematized information can be seen in Table 4.

Table 4.

Outcomes of thirty-five selected articles according to PRISMA-ScR guidelines.

Table 5 presents studies organized by specific marketing subcategories related to Fair Trade coffee, including consumer behavior, market segmentation, positioning, operational efficiency, and quality of life. Each subcategory is linked to specific methodologies and samples, which influence the findings and practical applications.

Table 5.

Results, Study Application, and Research Limitations/Implications of Studies.

In consumer behavior, studies explore how factors such as personality, ethical values, and knowledge about Fair Trade influence consumers’ willingness to pay a premium for these products [50,51] The studies show that consumers motivated by humanitarian values and sustainability are more likely to support Fair Trade products. In market segmentation, distinct consumer segments are identified, such as eco-conscious youth or those prioritizing social status [64]. As a result, marketing strategies focus on personalizing communication based on the target audience’s characteristics.

In positioning, studies emphasize how ethical brands can differentiate themselves in saturated markets by highlighting attributes such as organic certification and direct trade, which are decisive factors for consumers [78]. In operational efficiency, the studies analyze pricing and promotion practices, highlighting that strategies such as coupons can have a greater impact on purchase intentions than traditional advertising campaigns, signaling the effectiveness of economic promotions over ethical attributes in some cases [63].

The practical applications of these studies include implementing marketing strategies tailored to different consumer segments, focusing on emphasizing ethical values and transparency in Fair Trade production. This can improve brand positioning and increase consumers’ willingness to pay. Additionally, cooperatives and public policies can benefit from the findings on how to improve the social and economic conditions of producers, promoting better health, education, and quality of life [54].

However, the main limitations include the small sample sizes, which make it difficult to generalize the findings to a broader audience. Furthermore, many studies present a self-report bias, which may affect the accuracy of responses about consumers’ ethical motivations. Additionally, the lack of longitudinal studies that track the long-term effects of Fair Trade on both consumers and producers is noted. Therefore, future research should address these limitations by expanding sample sizes and evaluating the sustained impact of Fair Trade over time. The specific details of each study are presented in the table below.

3.6. Concentric Studies in Peripheral and Central Areas

In central countries, such as the United States, Canada, France, Germany, Sweden, Taiwan, South Korea, Spain, and China, research is concentrated on strategic and operational marketing, with a focus on enhancing the positioning of Fair Trade products, consumer knowledge, and pricing strategies. These studies explore the dynamics of consumer behavior, particularly the willingness to pay a premium for ethically sourced products, and the role of marketing strategies in driving consumer engagement. The United States, for example, is a key player in both strategic and operational marketing, with research examining how consumer knowledge and ethical values shape purchasing decisions. Similarly, Canada, Germany, and Sweden also explore both strategic and operational aspects, with a strong emphasis on integrating Fair Trade products into the broader market.

In peripheral countries, such as Nicaragua, Peru, Guatemala, Mexico, Costa Rica, Uganda, Tanzania, Colombia, Philippines, Czech Republic, and Belgium, the focus shifts to macromarketing and strategic marketing. Studies in these regions explore cooperativism, quality of life, and the socioeconomic impacts of Fair Trade, especially on health, education, and income levels. Nicaragua, Peru, and Guatemala stand out for their emphasis on the developmental aspects of Fair Trade, with research looking into the benefits of cooperative models in improving the livelihoods of coffee producers. Costa Rica, while showing a strong presence in macromarketing and operational marketing, also offers insights into the operationalization of Fair Trade in agricultural supply chains. Furthermore, Uganda and Tanzania contribute to strategic marketing research, analyzing consumer motivations and the adoption of Fair Trade products in these emerging markets (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Cross-matrix with respect to concentric studies in peripheral and central areas.

4. Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive review of the literature on Fair Trade marketing within the coffee industry, focusing on macromarketing, strategic marketing, and operational marketing. It emphasizes the contributions of these areas to the development of organizations and society while analyzing the geographical scope of reported cases, highlighting distinctions between core and peripheral regions. The findings reveal key patterns and notable gaps in the scope and focus of current research.

The analysis of marketing components in the fair trade coffee industry reveals that the three dimensions of marketing—macromarketing, strategic marketing, and operational marketing—play essential but differentiated roles in strengthening and expanding this model. Regarding macromarketing, this approach allows us to understand how marketing decisions impact not only businesses but also society, the global economy, and the environment [54]. In this context, fair trade promotes an equitable distribution of benefits between producers and intermediaries, improving the social and economic conditions of farmers in developing countries, as seen in studies by Arnould et al. [20], and Arana-Coronado [58]. However, the findings show that despite improvements in the income and well-being of producers, a significant portion of the value generated in the supply chain continues to be absorbed by retailers and processors in consumer countries, limiting the direct impact on producers [61,75]. This challenge is linked to the unequal structures of the global market, which continue to favor the most powerful actors, reflecting the critiques of inequity highlighted in various studies, such as those by Murphy et al. [59].

Despite initiatives aimed at improving conditions for producers, global market policies and structures remain imbalanced, creating a cycle of dependence where the benefits of fair trade are not always distributed equitably. This suggests that while the fair trade market is effective in certain respects, it still faces significant challenges related to the redistribution of value along the supply chain. Moreover, it can be argued that fair trade initiatives in many cases are not fully aligned with the economic realities of developing countries, which necessitates a rethinking of global trade structures to ensure a more equitable distribution of benefits. In this regard, studies by Schollenberg [75], and Durevall [76] reinforce this idea, pointing out that inequalities in the supply chain are central to understanding the limitations of fair trade, as not all parties involved receive the benefits proportionally. It is crucial for central countries, which dominate economic and trade decisions, to reconfigure their relations with peripheral countries, where the producers are located, to achieve a fairer distribution of the income generated by fair trade coffee.

Strategic marketing, for its part, has proven essential in positioning fair trade products in an increasingly competitive global market. Consumer segmentation based on ethical and social values is key to attracting an audience that values sustainability and social justice. In this sense, studies such as Ufer et al. [50], and Lappeman et al. [51] have found that personality traits such as social consciousness and extraversion are key factors in determining the willingness to pay a premium price for fair trade products. This type of marketing not only responds to ethical demand but also uses positioning strategies based on authenticity and differentiation [55]. However, significant challenges remain, such as the lack of transparency in marketing campaigns, which generates doubts about the effectiveness of fair trade certifications [78]. In this context, studies by Hindsley et al. [33] show how cultural differences can significantly influence consumer perceptions of the value of fair trade, which suggests that marketing strategies must be adapted to specific cultural contexts to maximize their impact.

Regarding operational marketing, this addresses the tactical aspects of fair trade product commercialization, such as pricing, promotional strategies, and distribution [62]. In this domain, studies such as those by Hwang et al. [57], and Joo et al. [66] have shown that pricing and promotional strategies are essential for encouraging consumption but also highlight that the premium price of fair trade products remains a significant barrier. Despite consumers’ willingness to pay more, the unequal distribution of value along the supply chain continues to be a concern, as retailers and large corporations capture a greater share of this value [75,76]. This phenomenon underscores the need to improve operational efficiency and transparency in marketing processes, as suggested by Tedeschi et al. [65], who argue that clarity in income distribution processes is critical to ensuring that benefits reach producers effectively. Furthermore, transparency of information regarding the social and environmental impact of products is one of the key areas that emerge from the analysis of operational marketing. Consumers positively value strategies for providing clear and accessible information about the sustainability of products, as indicated by Schleenbecker et al. [78], which focuses on the importance of consumer education in marketing campaigns. This approach not only increases trust in brands but also reinforces the consumer’s commitment to the ethical values associated with fair trade [65]. However, if the information provided is not sufficiently clear, marketing strategies risk becoming superficial, where consumers do not fully connect with the true value of fair trade.

5. Conclusions

This study underscores the essential role of Fair Trade marketing in advancing ethical consumption in core markets while addressing the socioeconomic challenges of producer communities in peripheral regions. Macromarketing research demonstrates that Fair Trade contributes to modest improvements in income, education, and health for producers, though these benefits are often constrained by systemic limitations. While macromarketing plays a key role in highlighting the positive social and economic impacts of Fair Trade on the communities, it also reveals that much of the value generated within the supply chain remains absorbed by intermediaries, particularly in the more developed markets, limiting the tangible benefits for the producers. Strategic marketing has successfully mobilized consumer demand through effective segmentation and positioning strategies, yet the narratives often prioritize individualistic motivations over genuine connections to producer realities. This emphasis on consumer ethics, though essential for driving demand, does not always translate into real and lasting change for the producers, as it fails to fully address the structural imbalances in the global trade system that continue to favor larger corporations over smaller, resource-constrained cooperatives. The virtual absence of operational marketing research further highlights critical gaps in understanding the practical implementation of Fair Trade principles, particularly in underrepresented regions such as Africa and Asia, where operational challenges differ significantly from those in Latin America.

By promoting more equitable trade practices, Fair Trade helps improve the income and quality of life of producers, especially in rural communities in developing countries, thereby strengthening their economic and social well-being. Additionally, Fair Trade promotes environmental sustainability by prioritizing environmentally friendly production methods, reinforcing the impact of SDG 12 (Sustainable Consumption and Production). Furthermore, the strengthening of cooperatives and community networks in these regions facilitates access to education and healthcare services, aligning with the goals of quality education (SDG 4) and ensuring healthy lives (SDG 3). Together, Fair Trade not only benefits producers and consumers but also reinforces the foundations of a more equitable and sustainable global development.

However, the systemic limitations of Fair Trade, including the unequal distribution of benefits in the supply chain, require further exploration and rectification. As Schollenberg [75], and Durevall [76] have pointed out, much of the value generated through Fair Trade remains concentrated in the hands of intermediaries and larger businesses, often leaving producers with only a small portion of the profits. This is particularly true in markets that dominate the global supply chain, where the benefits are often disproportionately distributed.

To address these limitations, future research must focus on expanding the scope of Fair Trade studies to encompass the diverse socio-economic contexts of Africa and Asia, where challenges differ significantly from those in Latin America. Operational marketing should become a priority area for research, with a focus on optimizing logistical processes, reducing certification costs, and supporting smaller, resource-constrained cooperatives. The transparency and clarity of certification processes will be essential in this regard, as Tedeschi et al. [65], and Schleenbecker et al. [78] stress that consumers increasingly demand transparency in the entire supply chain, not just at the consumer-facing level. Furthermore, strategic narratives in core markets must evolve to authentically represent the challenges and achievements of producer communities, bridging the gap between consumer expectations and producer realities. By addressing these gaps, Fair Trade can strengthen its ethical value proposition, foster deeper connections between consumers and producers, and drive meaningful socio-economic transformations in the most vulnerable contexts.

Finally, Fair Trade has the potential to catalyze not only economic improvement for producers but also a more equitable global trade system that aligns with the broader goals of social sustainability and inclusive economic growth. This vision can only be achieved through continued research, transparency in operations, and the deepening of consumer–producer relationships, ensuring that Fair Trade remains a powerful tool for global equity and sustainability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture15050465/s1, Table S1: FTC ScR data.xlsx.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.-L., A.V.-M. and N.C.-B.; methodology, J.M.-L. and G.S.-S.; validation, A.V.-M.; formal analysis, J.M.-L.; writing—original draft preparation, N.C.-B., J.M.-L.; writing—review and editing, J.M.-L., N.C.-B., A.V.-M. and G.S.-S.; supervision, A.V.-M.; project administration, J.M.-L. and N.C.-B.; funding acquisition, A.V.-M., N.C.-B. and G.S.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article has received partial funding for the article processing charge (APC), thanks to Basal Funds from the Chilean Ministry of Education, directly or via the publication incentive fund from the following Higher Education Institutions: Universidad Arturo Prat (Code: APC2025), Universidad Católica de la Santísima Concepción (Code: APC2025), Universidad Central de Chile (Code: APC2025), Universidad de Las Américas (Code: APC2025), and Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso (Code: APC2025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable; this study does not involve humans or animals.

Data Availability Statement

Data availability in Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nicholls, A.; Huybrechts, B. Sustaining inter-organizational relationships across institutional logics and power asymmetries: The case of fair trade. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairtrade International. Fairtrade and the Sustainable Development Goals: A Review of the Impact of Fairtrade. Sustainability 2020, 12, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairtrade USA. Consumer Report: Conscious Consumerism Goes Mainstream. 2022. Available online: https://www.fairtradecertified.org (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Raynolds, L.T. Fair Trade: Social regulation in global food markets. J. Rural Stud. 2012, 28, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meemken, E.M.; Sellare, J.; Kouame, C.N.; Qaim, M. Effects of Fairtrade on the livelihoods of poor rural workers. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairtrade International. Annual Report: Driving Progress Through Fairtrade. 2023. Available online: https://www.fairtrade.net (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Bezençon, V.; Blili, S. Ethical products and consumer involvement: What’s new? Eur. J. Mark. 2010, 44, 1305–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koszewska, M. A typology of Polish consumers and their behaviours in the market for sustainable textiles and clothing. International. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-De los Salmones, M.; Pérez, A. The role of brand utilities: Application to buying intention of fair trade products. J. Strateg. Mark. 2019, 27, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, M.J.; Neville, B.A.; Whitwell, G.J. Why Ethical Consumers Don’t Walk Their Talk: Towards a Framework for Understanding the Gap Between the Ethical Purchase Intentions and Actual Buying Behaviour of Ethically Minded Consumers. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzarova, M.; Dyer, C.; Falta, M. Perceptions of blockchain readiness for fairtrade programmes. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 185, 122086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layton, R.A. Marketing systems—A core macromarketing concept. J. Macromark. 2007, 27, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooliscroft, B. Macromarketing and the Systems Imperative. J. Macromark. 2020, 41, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbourne, W.E.; McDonagh, P.; Prothero, A. Sustainable Consumption and the Quality of Life: A Macromarketing Challenge to the Dominant Social Paradigm. J. Macromark. 1997, 17, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelstaedt, J.D.; Shultz, C.J.; Kilbourne, W.E.; Peterson, M. Sustainability as Megatrend: Two Schools of Macromarketing Thought. J. Macromark. 2014, 34, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J. Macromarketing Metrics of Consumer Well-Being: An Update. J. Macromark. 2020, 41, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, M.J. Assessing distributive justice in marketing: A benefit-cost approach. J. Macromark. 2007, 28, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, K.; Peattie, K. Grounded Theory as a Macromarketing Methodology: Critical Insights from Researching the Marketing Dynamics of Fairtrade Towns. J. Macromark. 2015, 36, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridell, M. Fair Trade and the international moral economy. Crit. Sociol. 2007, 33, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnould, E.; Plastina, A.; Ball, D. Does Fair Trade Deliver on Its Core Value Proposition? Effects on Income, Educational Attainment, and Health in Three Countries. J. Public Policy Mark. 2009, 28, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannessen, S.; Wilhite, H. Who Really Benefits from Fairtrade? An Analysis of Value Distribution in Fairtrade Coffee. Globalizations 2010, 7, 525–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajan, R. Customer information resources advantage, marketing strategy and business performance: A market resources based view. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 89, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintani, L.; Ridwan, R.; Kadeni, K.; Savitri, S.; Ahsan, M. Understanding marketing strategy and value creation in the era of business competition. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2023, 6, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, G.-F.; Wang, R.-Y.; Yang, H.-T. How consumer mindsets in ethnic Chinese societies affect the intention to buy Fair Trade products: The mediating and moderating roles of moral identity. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2017, 29, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konopka, R.; Wright, M.J.; Avis, M.; Feetham, P.M. If you think about it more, do you want it more? The case of fairtrade. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2556–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.S.-T.; Chou, C.-F. Norms, consumer social responsibility and fair trade product purchase intention. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2020, 49, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, I.A.; Gutsche, S. Consumer motivations for Fair Trade: Why are consumers buying Fairtrade products? J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffee, D. Fair trade standards, corporate participation, and social movement responses in the global economy. Sociol. Perspect. 2014, 57, 416–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koos, S. Moralising markets, marketizing morality. The fair trade movement, product labeling and the emergence of ethical consumerism in Europe. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2021, 33, 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukotjo, C. Marketing mix for service businesses: The 7Ps. Bus. Rev. 2010, 54, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, X. Green marketing and sustainability in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzarova, M.A.; Castka, P.; Boughen, N. Sustainability and the fair trade premium: A stakeholder approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindsley, P.; McEvoy, D.; Morgan, O. Consumer Demand for Ethical Products and the Role of Cultural Worldviews: The Case of Direct-Trade Coffee. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 177, 106776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavorata, L. Retailers’ commitment to sustainable development: A strategy to gain consumer loyalty? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 1021–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littrell, M.A.; Dickson, M.A.; Vieira, E.A. Fair Trade apparel: Consumer perceptions of social responsibility. J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lever, J.; Evans, A. Ethical food labeling and consumer trust. J. Consum. Policy 2017, 40, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pelsmacker, P.; Janssens, W.; Sterckx, E.; Mielants, C. Consumer Preferences for the Marketing of Ethically Labelled Coffee. Int. Mark. Rev. 2005, 22, 512–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Methley, A.M.; Campbell, S.; Chew-Graham, C.; McNally, R.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega-Muñoz, A.; Maradiaga-López, J.; Salazar-Sepúlveda, G.; Contreras-Barraza, N. Study Protocol for a Scoping Review About Marketing Components in Fair Trade Coffee Studies. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/14541112 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Pace, R.; Pluye, P.; Bartlett, G.; Macaulay, A.C.; Salsberg, J.; Jagosh, J.; Seller, R. Testing the Reliability and Efficiency of the Pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for Systematic Mixed Studies Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, A.L.; Kongthon, A.; Lu, J.C. Research profiling: Improving the literature review. Scientometrics 2002, 53, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarivate. Advanced Search Query Builder, Web of Science. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/advanced-search (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Scopus. Advanced Search. Available online: https://www-scopus-com.unap.idm.oclc.org/search/form.uri?display=advanced (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- McGowan, J.; Sampson, M.; Salzwedel, D.M.; Cogo, E.; Foerster, V.; Lefebvre, C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J. Clinic. Epidemiol. 2016, 75, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas-Monreal, L.; Galván-Estrada, I.G.; Dorantes-Pacheco, L.; Márquez-Serrano, M.; Medrano-Vázquez, M.; Valdez-Santiago, R.; Piña-Pozas, M. Alfabetización sanitaria y COVID-19 en países de ingreso bajo, medio y medio alto: Revisión sistemática. Global Health Promot. 2023, 30, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ufer, D.; Lin, W.; Ortega, D.L. Personality traits and preferences for specialty coffee: Results from a coffee shop field experiment. Food Res. Int. 2019, 125, 108504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappeman, J.; Orpwood, T.; Russell, M.; Zeller, T.; Jansson, J. Personal values and willingness to pay for fair trade coffee in Cape Town, South Africa. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 239, 118012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnot, C.; Boxall, P.C.; Cash, S.B. Do ethical consumers care about price? A revealed preference analysis of fair trade coffee purchases. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2006, 54, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andorfer, V.A.; Liebe, U. Do information, price, or morals influence ethical consumption? A natural field experiment and customer survey on the purchase of Fair Trade coffee. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015, 52, 330–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger-Oneto, S.; Arnould, E.J. Alternative trade organization and subjective quality of life: The case of Latin American coffee producers. J. Macromark. 2011, 31, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darian, J.C.; Tucci, L.; Newman, C.M.; Naylor, L. An analysis of consumer motivations for purchasing fair trade coffee. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2015, 27, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winchester, M.; Arding, R.; Nenycz-Thiel, M. An Exploration of Consumer Attitudes and Purchasing Patterns in Fair Trade Coffee and Tea. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2015, 21, 552–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.; Kim, H. Are Ethical Consumers Happy? Effects of Ethical Consumers’ Motivations Based on Empathy Versus Self-orientation on Their Happiness. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 579–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arana-Coronado, J.J.; Trejo-Pech, C.O.; Velandia, M.; Peralta-Jimenez, J. Factors Influencing Organic and FairTrade Coffee Growers Level of Engagement with Cooperatives: The Case of Coffee Farmers in Mexico. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2018, 31, 22–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.; Jenner-Leuthart, B. Fairly sold? Adding value with fair trade coffee in cafes. J. Consum. Mark. 2011, 287, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnould, E.J.; Plastina, A.; Ball, D. Market Disintermediation and Producer Value Capture: The Case of Fair Trade Coffee in Nicaragua, Peru, and Guatemala. Product and Market Development for Subsistence Marketplaces. Adv. Int. Manag. 2007, 20, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, P.; Jaffee, D. Tensions between firm size and sustainability goals: Fair trade coffee in the United States. Sustainability 2013, 5, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-M.; Huddleston, P. A comparison of four strategies to promote fair trade products. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2009, 37, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podhorsky, A. A positive analysis of Fairtrade certification. J. Dev. Econ. 2015, 116, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cailleba, P.; Casteran, H. A Quantitative Study on the Fair Trade Coffee Consumer. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2009, 25, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, G.A.; Carlson, J.A. Beyond the subsidy: Coyotes, credit and fair trade coffee: Beyond the subsidy. J. Int. Dev. 2013, 25, 456–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S.-J.; Min, H.; Kwon, I.-W.G.; Kwon, H. Comparative efficiencies of specialty coffee retailers from the perspectives of socially responsible global sourcing. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2010, 21, 490–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, C. Confronting the coffee crisis: Can fair trade, organic, and specialty coffees reduce small-scale farmer vulnerability in northern Nicaragua? World Dev. 2005, 33, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wann, J.-W.; Kao, C.-Y.; Yang, Y.-C. Consumer preferences of locally grown specialty crop: The case of Taiwan coffee. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, W.S.; Chekmam, L.; Maza, M.T.; Mancilla, N.O. Consumers’ preference for the origin and quality attributes associated with production of specialty coffees: Results from a cross-cultural study. Food Res. Int. 2016, 89, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Jin, Y.; Shin, H. Cosmopolitanism and ethical consumption: An extended theory of planned behavior and modeling for fair trade coffee consumers in South Korea. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 26, 822–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cailleba, P.; Casteran, H. Do ethical values work? A quantitative study of the impact of fair trade coffee on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robichaud, Z.; Yu, H. Do young consumers care about ethical consumption? Modelling Gen Z’s purchase intention towards fair trade coffee. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 2740–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, R. Dynamics of Social Capital among Fair Trade and Non-Fair Trade Coffee Farmers. DLSU Bus. Econ. Rev. 2018, 28, 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Maaya, L.; Meulders, M.; Surmont, N.; Vandebroek, M. Effect of environmental and altruistic attitudes on willing-ness-to-pay for organic and fair trade coffee in Flanders. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schollenberg, L. Estimating the hedonic price for Fair Trade coffee in Sweden. Br. Food J. 2012, 114, 428–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durevall, D. Fairtrade and market efficiency: Fairtrade-labeled coffee in the Swedish coffee market. Economies 2020, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejkrlík, J.; Mazancová, J.; Forejtová, K. How effective is Fair Trade as a tool for the stabilization of agricultural commodity markets? Case of coffee in the Czech Republic. Agric. Econ. 2013, 59, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleenbecker, R.; Hamm, U. Information needs for a purchase of Fairtrade coffee. Sustainability 2015, 7, 5944–5962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ferran, F. Les motivations des acheteurs de produits issus du commerce équitable: Des tendances différentes selon les caractéristiques de l’individu. Cah. Agric. 2010, 19, 041–049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-H.; Qing, P.; Hu, W.; Liu, Y. Using a modified payment card survey to measure Chinese consumers’ willingness to pay for fair trade coffee: Considering starting points. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2013, 61, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Jovel, K.; Sellare, J.; Damm, Y.; Dietz, T. SDGs Trade-Offs Associated with Voluntary Sustainability Standards: A Case Study from the Coffee Sector in Costa Rica. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 917–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fader, P.; Hardie, B.; Lee, K.L. “Counting Your Customers” The Easy Way: An Alternative to the Pareto/NBD Model. Mark. Sci. 2005, 24, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).