Abstract

Conventional cereal production in coastal saline–alkali drylands is constrained by low productivity and soil degradation. While diversified cropping and biochar application have each been shown to enhance soil quality, the effects of their short-term integration into continuous cereal systems remain unclear, particularly regarding crop yield, soil health, and economic returns. A field experiment was conducted to compare a continuous wheat–maize rotation (W) with systems where one cycle of that was replaced by an alfalfa–sweetpotato (A) or rapeseed–soybean (R) rotation, under biochar-amended and non-amended conditions. Diversified rotations increased subsequent wheat yields by 6.6–16.2%. System A achieved 216% and 439% higher cumulative equivalent yield and economic benefit than System W, respectively. Even without biochar, A and R systems increased soil organic matter content, aggregate stability, and fungal richness by 16.3–21.0%, 20.6–26.5%, and 8.60–10.2%, respectively, compared to W. Biochar further enhanced crop yields by 6.36–16.3% and integrated fertility score by 7.78–9.01%, but its initial cost reduced profitability. Comprehensive evaluation conducted via a weighted model indicated that system A, combined with biochar, achieved the optimal balance among productivity, soil fertility, economics, and microbial diversity. These findings demonstrate that integrating “green” (diversified cropping) and “black” (biochar) strategies offers synergistic benefits for sustainable production in coastal saline–alkali drylands.

1. Introduction

Ensuring global food security remains a challenge in the face of climate change, land degradation, and population growth [,]. As one of the most widespread soil constraints, saline–alkali land covers approximately 0.83–1.17 billion hectares worldwide [], with China possessing nearly 100 million hectares thereof []. The utilization and remediation of these marginal lands are therefore critical to safeguarding sustainable agricultural production and national food sovereignty []. However, achieving this potential is hindered by the inherent limitations of these fragile ecosystems, such as salinity stress and low soil fertility, especially in rainfed drylands where soil organic carbon (SOC) is more easily decomposed [], and water scarcity prevents traditional leaching-based reclamation [].

Coastal saline–alkali lands represent a particularly challenging area for remediation due to the complexities of seawater intrusion and the dynamic interplay of soil water and salt conditions []. Conventional cereal production in the drylands of coastal saline–alkali areas in China is dominated by the winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)–summer maize (Zea mays L.) rotation. However, even at low to medium salinity levels, the high productivity of wheat and maize relies heavily on rigorous management, high soil fertility, and favorable environmental conditions []. Owing to the limited labor availability, vulnerable soil health stability, and climate variability [,], the reported wheat and maize yields in these regions (3.89–4.40 t ha−1; [,]) were only about 60% of the national average []. Moreover, studies have reported that continuous cereal monocultures would further accelerate soil degradation, reduce microbial diversity, and diminish system resilience [,]. These limitations underscore the urgent need for developing strategies that restore productivity and ecological function.

Biochar, a carbon (C)-rich amendment produced from pyrolyzed biomass, has gained recognition for its ability to rapidly enhance soil organic matter (SOM), improve nutrient retention, and ameliorate soil structure [,,], and modify bacterial community structure in saline soils [,]. For example, a recent study conducted in a coastal saline soil reported 78.1% and 82.2% increments in the contents of soil available nitrogen (N) and organic C, respectively, compared with the control []. However, despite these soil fertility benefits, biochar’s additional costs and limited enhancement in yield gains prevent significant short-term economic returns [,].

Diversified cropping has been widely reported to improve soil health [,,]. It has also been demonstrated that incorporating diversified crops into an existing cropping system can benefit the productivity of subsequent crops []. For example, a five-year field study indicated that the cultivation of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) resulted in 31% higher yield of subsequent maize []; a meta-analysis also revealed that including legumes in rotation provided a 9–27% increase in the subsequent wheat yield []. Considering that the cultivation of diversified crops such as legumes and oilseeds often generates higher economic returns compared to cereal cropping [], replacing one year of the wheat–maize cycle with a diversified rotation might provide a solution for simultaneously sustaining cereal output while improving soil health and farm profitability in coastal saline–alkali soil.

Alfalfa, sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas Lam.), rapeseed (Brassica napus L.), and soybean (Glycine max (Linn.) Merr.) are each associated with traits such as N fixation, salt and barren tolerance, and economic efficiency. For instance, alfalfa exhibits strong osmotic regulation and ion homeostasis capabilities [], while sweetpotato reduces surface evaporation, thus mitigating salt accumulation [] and utilizes potassium (K) efficiently [], a trait advantageous in K-rich coastal soils. Additionally, soybean and rapeseed contribute biological N fixation and diverse root exudates, respectively [,]. Given the heterogeneity in nutrient demand and other physiological traits across diverse crops, management strategies, including fertilization regimens, necessitate divergent approaches. Nevertheless, it remains elusive whether an agronomically and economically viable cropping system centered on these crops can be established in coastal saline–alkaline soils.

Combining biochar application with diversified cropping systems may further enhance soil health and boost short-term productivity in coastal saline–alkali soils. However, most studies focus exclusively on either biochar application or diversified cropping alone. Systematic evaluations of their combined effects, particularly multi-dimensional impacts on crop yield, soil fertility, economic benefits, and soil biodiversity in these environments, remain scarce.

Therefore, this study conducted a field experiment aiming to evaluate the integrated effects of introducing one-year diversified rotations, i.e., alfalfa–sweetpotato and rapeseed–soybean, into a conventional wheat–maize system, with and without biochar application, on crop productivity, soil fertility, economic benefits, and microbial diversity in a coastal saline–alkali dryland. The hypotheses of the study are as follows: (1) short-term incorporation of crop diversification improves soil fertility, microbial diversity indices, and system profitability while increasing subsequent cereal yields; and (2) the combination with biochar leads to greater short-term improvements in soil fertility and productivity. The outcomes of the study are expected to inform policy and practice for resilient farming in marginal environments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

The study was conducted in Dongtai County, Jiangsu Province, China (32°50′52″ N, 120°57′53″ E). This site is situated on the western coast of the Yellow Sea and is characterized as a typical coastal saline–alkali region. The climate of this region is subtropical marine monsoonal. The region has a mean annual temperature of 15 °C, with the lowest and highest monthly means being 2 °C in January and 32 °C in July, respectively. The mean annual precipitation is 1060 mm, and the interannual variation ranges from 980 to 1100 mm. The site practices rainfed agriculture with a winter wheat–summer maize cropping system before the establishment of our study. The soil in this site is classified as Solonchaks (salic Inceptisols) with a sandy loam texture (sand 70.5%; silt 24.4%; clay 5.1%). The basic physicochemical properties (0–20 cm) prior to the experiment were as follows: pH 8.76, SOM content 11.64 g kg−1, available K (AK) content 417 mg kg−1, available phosphorus (AP) content 18.94 mg kg−1, alkali-hydrolyzable N (AN) content 43.02 mg kg−1, and total soluble salt (TDS) content 2.4 g kg−1. Pre-experiment soil analysis confirmed uniform physicochemical properties across the experimental area, which satisfied statistical requirements for treatment effect evaluation.

2.2. Experimental Design and Setup

The field study utilized a two-factor split-plot design. The main-plot factor was the cropping system, which included continuous winter wheat–summer maize cropping (wheat–maize–wheat system; W), and replaced one cycle of wheat–maize cropping with winter alfalfa–summer sweetpotato (alfalfa–sweetpotato–wheat system; A), and winter rapeseed–summer soybean rotations (rapeseed–soybean–wheat system; R). The sub-plot factor was the biochar application, which included the non-biochar (CK) and biochar (BC) applications. A 3 × 2 factorial design was employed, combining the two factors, resulting in six treatments (Table 1). Each treatment was replicated three times, and the plot area was 30 m2 (5 m × 6 m).

Table 1.

Details of cropping systems and biochar application for different treatments in the study.

The study involved three cropping seasons. The first cropping season (wheat, alfalfa, or rapeseed) was conducted from October 2023 to June 2024; the second cropping season (maize, sweetpotato, and soybean) was conducted from June 2024 to October 2024; and the third cropping season (wheat) was conducted from November 2024 to June 2025. The seeding rates were 30 kg seed ha−1 for maize [], 300 kg seed ha−1 for wheat [], 17 kg seed ha−1 for alfalfa [], 60,000 plant ha−1 for sweetpotato [], 4.5 kg seed ha−1 for rapeseed [], and 90 kg seed ha−1 for soybean [].

The biochar used in this experiment was acid-modified with a pH of 7.12, and contained 384 g kg−1 of C and 7.76 g kg−1 of N. The biochar was applied once at a rate of 15 Mg ha−1 [] to the biochar-involved treatment before the sowing of the first cropping season. Synthetic fertilizers were applied manually across all plots. N, phosphorus (P), and K were applied as urea, superphosphate, and potassium sulphate, respectively. The N application rates for wheat, maize, alfalfa, sweetpotato, rapeseed, and soybean were 300, 300, 225, 120, 150, and 330 kg ha−1 season−1, respectively. The detailed P and K application rates are listed in Table S1. These application rates followed crop-specific fertilization guidelines from the local agricultural authority, which comprehensively accounted for soil nutrient supply, crop nutrient demand, and crop residue cycling. No secondary or micronutrients were applied, as soil levels of these elements in the region were evaluated as medium or higher, and no visible micronutrient deficiency symptoms were documented in historical records.

2.3. Sampling and Analysis

2.3.1. Soil Sampling and Analysis

Soil samples were collected from the 0–20 cm soil layer using a five-point sampling approach in each plot at the harvest of the third-season crop. These samples were split into two subsamples, which were stored at −80 °C for the analysis of microbial diversity, and air-dried after removing roots and stones, then ground, sieved, and stored for the analysis of pH, SOM, AK, AN, AP, and TDS, respectively. In addition, three sample points were taken to collect undisturbed soil blocks from the 0–20 cm layer of each plot. These soil blocks were placed in plastic boxes and transported to the laboratory to measure aggregates.

Soil fertility parameters, specifically soil pH and the contents of SOM, AK, AP, AN, and TDS, were analyzed by standardized methods []. Briefly, soil pH was measured in a 1:5 (w/w) soil/water extract using a pH meter; SOM was determined by the potassium dichromate external heating method; AK was measured by ammonium acetate extraction-flame photometry method; AP was analyzed by molybdenum antimony blue colorimetry; AN was assessed by the alkali-hydrolyzable diffusion method; and TDS was determined by the gravimetric method.

The size distribution and stability of water-stable aggregates were determined using a wet-sieving method adapted from []. Briefly, 50 g of air-dried undisturbed soil was placed on the top sieve of a nested set with mesh sizes of 2, 0.25, and 0.053 mm. The sample was first gently moistened until the surface was uniformly damp. The sieve assembly was then immersed in deionized water for 5 min, followed by mechanical oscillation using a wet-sieving apparatus at a rate of 30 oscillations per minute with a 4 cm amplitude. The sieving process continued until the water passing through the sieves ran clear. The aggregates retained on each sieve were quantitatively transferred into pre-weighed aluminum containers. All fractions were oven-dried at 65 °C for 48 h and subsequently weighed.

Microbial DNA was extracted from 0.5 g of soil using the E.Z.N.A.® Soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocols. The bacterial 16S rRNA gene V3–V4 region was amplified with the primers 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′), while the fungal ITS region was amplified using primers ITS1F (5′-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA-3′) and ITS2R (5′-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3′). The process of PCR was detailed in the Supplementary Materials. OTUs were clustered at a 97% similarity threshold using UPARSE (v10.0), and alpha diversity indices were calculated in Mothur (v1.21.1) based on rarefied OTU tables.

2.3.2. Plant Sampling and Analysis

Crop yields for wheat, alfalfa, rapeseed, and soybean were measured by randomly selecting three undisturbed quadrats from each plot, with each quadrat covering an area of 1 m2 for wheat and alfalfa and 4 m2 for rapeseed and soybean. The oven-dried aboveground biomass of alfalfa, or the air-dried grains of wheat, rapeseed, and soybean within the quadrats, were weighed to assess their yields. The yields of sweetpotato and maize were measured by harvesting the entire plots. The fresh tuber yield of sweetpotato and air-dried maize grain were weighed to evaluate their yields. The aboveground biomass of alfalfa was harvested twice in our study, which was on 26 April 2024 and 6 June 2024. Samples of alfalfa (entire aboveground biomass), soybean (grain and straw), and sweetpotato (tuber and straw) were collected at harvest, oven-dried, ground, and analyzed for N, P, and K contents [].

2.4. Calculations and Statistical Analyses

Indicators of equivalent yield, protein yield, yield gain, and economic benefit were used to evaluate the crop productivity and economic performance. The equivalent yield (Mg ha−1) was calculated by converting the yields of all crops into their wheat equivalents []. The prices of the crop outputs were obtained from the National Agricultural Product Cost–Benefit Data [], and these prices were used to calculate the yield gain (103 yuan ha−1). The protein yield was calculated by multiplying the crop yield by the protein content, which was listed in Table S2. Economic benefit (103 yuan ha−1) was assessed by integrating the yield gain with agricultural input costs across the crop seasons, with the specific costs of each treatment listed in Table S1. The formulas for calculating the yields [] and economic outputs [] are presented below:

where yij denotes the yield (Mg ha−1) of treatment i in the jth season, the vij represents the market value (yuan kg−1) of the corresponding crop in that season, and vw is the market value of wheat (yuan kg−1).

where yij denotes the primal yield (Mg ha−1) of treatment i in the jth season, and pij represents the protein content (%) of the corresponding crop.

where yij denotes the crop yield (Mg ha−1) of treatment i in the jth season, the vij represents the market value (yuan kg−1) of the corresponding crop in that season.

The cumulative economic benefit (103 yuan ha−1) indicates the accumulation of economic benefit till a specific cropping season. Where yij denotes the crop yield (Mg ha−1) of treatment i in the jth season, the vij represents the market value (yuan kg−1) of the corresponding crop in that season; cij denotes the agricultural input cost (yuan ha−1) of treatment i in the jth season. The n represents the total number of cropping seasons in the rotation cycle.

The mean weight diameter (MWD; mm) and geometric mean diameter (GMD; mm) of aggregates were measured to evaluate soil structure from aggregate size distributions. The formulas were calculated as follows:

where y is the number of size fractions, the dx is the average diameter of each size class (mm), the is the weight fraction of each aggregate size relative to the total soil sample class.

Each soil fertility indicator was normalized into scores ranging from 0 to 1 [,]. The indicators belonging to the “more is better” and “less is better” scoring functions were calculated using Equations (7) and (8), respectively. For indicators having an “optimum range”, Equation (7) (applied when values are below the optimum) and Equation (8) (applied when values are above the optimum) were used to assign higher scores closer to the optimum.

where Score is the score of a specific soil fertility indicator, v is the measured value of the soil fertility indicator; vmax and vmin are the maximum and minimum values of the indicator.

Integrated soil fertility score was calculated for evaluating the overall soil fertility level, which was computed as the weighted sum of specific soil fertility scores (Equation (9); []). The weights of individual fertility scores were based on principal component analysis (PCA) of all soil fertility indicators []. The sum of the loadings derived from the principal components was used to represent the weight of each indicator. The selection of the principal components was based on the eigenvalues of >1 and cumulative variance > 80%.

where be is the score of indicator eth of one treatment. The is the weight of the eth indicator based on PCA. The f represents the number of indicators.

The calculations of alpha diversity indices of bacteria and fungi, including richness, Chao1, ACE, Shannon, Simpson, Pielou, and Faith’s PD, were referred to [,]. The calculations of the integrated microbial diversity score were calculated using the same approach as the integrated soil fertility score by weighted summing the normalized alpha diversity indexes of fungi.

A comprehensive evaluation index (CEI) was established to compare the overall benefits of different treatments. This index integrated multiple dimensions, including soil fertility score, microbial diversity score, and cumulative values of equivalent yield, protein yield, and economic benefit. The values of dimensions were normalized using Equation (10) []:

where bα is the normalized value of the αth dimension; gα is the measured value of the αth dimension, and gmax and gmin are the maximum and the minimum values of a single dimension, respectively.

The weights for these different dimensions in the CEI were also determined through PCA []. The final comprehensive score for each treatment was calculated using a similar weighted sum formula:

where λα is the weight of αth dimension based on PCA. The β represents the number of dimensions.

Two-way ANOVA for a split-plot design was conducted using SPSS 22.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). ANOVA assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances were tested with Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s tests, respectively. Post hoc Tukey’s HSD test was performed for factors or interactions where the ANOVA F-test was statistically significant (p < 0.05). PCA, Pearson correlation analysis, and random forest model were conducted using R 4.5.1. PCA suitability was confirmed through Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin sampling adequacy assessment and Bartlett’s sphericity test prior to analysis. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted to identify the direct and indirect effects of diversified cropping and biochar application on the dimensions of crop productivity, soil fertility, microbial diversity, and economic benefits. The best-fit SEM model was evaluated with AMOS 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Figures were generated using R and GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Crop Productivity and Economic Benefit

Biochar application consistently enhanced crop yields by 6.36–16.3% across all cropping systems and seasons, with significant effects observed in the wheat and soybean yield during the first and second seasons, respectively (p < 0.05; Table 2). Biochar application was also found to significantly enhance the N content in the tuber of sweetpotato and the grain of soybean (Table S3). In the third season, the A and R systems increased wheat yield by 6.60% and 16.2%, respectively, relative to the W system.

Table 2.

Crop yield (Mg ha−1) across three cropping seasons as influenced by cropping system (CS) and biochar application (BC): Values are represented as mean ± standard error (n = 3). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between biochar treatments within the same cropping system, respectively. The F-values show the results of the two-way ANOVA for CS and BC factors; ns indicates non-significance. W_CK: wheat–maize–wheat system (W) without biochar (CK); W_BC: wheat–maize–wheat system (W) with biochar (BC); A_CK: alfalfa–sweetpotato–wheat system (A) without biochar (CK); A_BC: alfalfa–sweetpotato–wheat system (A) with biochar (BC); R_CK: rapeseed–soybean–wheat system (R) without biochar (CK); R_BC: rapeseed–soybean–wheat system (R) with biochar (BC).

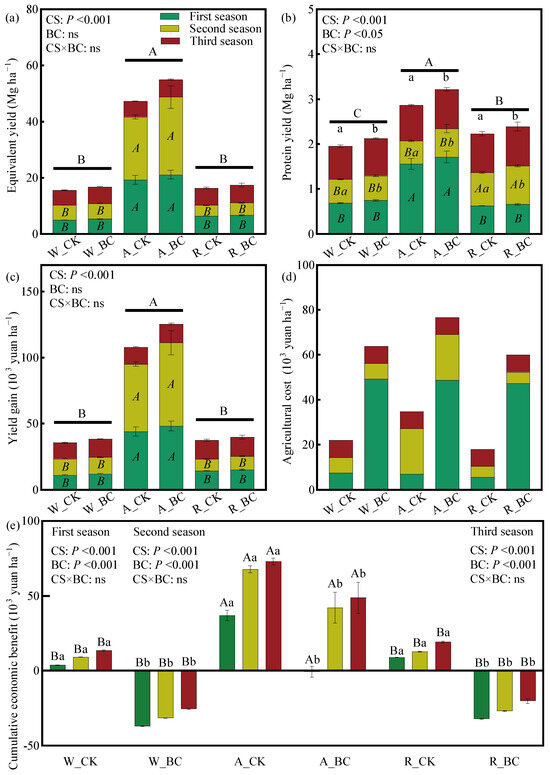

The A system achieved 216% and 202% higher cumulative equivalent yield than the W and R systems, respectively (Figure 1a). Both the cropping system and biochar application significantly influenced cumulative protein yields. R and A systems increased protein yields by 13.8–46.2% compared to the W system (p < 0.05). Although biochar showed a tendency to improve equivalent yield, protein yield, and yield gain, elevated agricultural costs (Figure 1d) reduced the net economic benefit of biochar application. Relative to the W system, the A and R systems enhanced cumulative economic benefit by 42.2–439% (Figure 1e), with first-season increases of 134–875%. The R_CK yielded the highest overall economic benefit among the treatments.

Figure 1.

(a) Equivalent yield, (b) protein yield, (c) yield gain, (d) agricultural cost, and (e) cumulative economic benefit under different cropping systems (CS) and biochar application (BC) treatments. Error bars represent the standard error (n = 3). Different uppercase and lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among cropping systems and between biochar treatments within the same cropping system, respectively. Regular and italicized letters denote the significance labels for the cumulative and season-specific values, respectively. ns indicates non-significance in the two-way ANOVA. W_CK: wheat–maize–wheat system (W) without biochar (CK); W_BC: wheat–maize–wheat system (W) with biochar (BC); A_CK: alfalfa–sweetpotato–wheat system (A) without biochar (CK); A_BC: alfalfa–sweetpotato–wheat system (A) with biochar (BC); R_CK: rapeseed–soybean–wheat system (R) without biochar (CK); R_BC: rapeseed–soybean–wheat system (R) with biochar (BC).

3.2. Soil Fertility

The cropping system significantly affected soil pH, SOM, AK, and AP, whereas biochar application primarily influenced SOM and AN (p < 0.05; Table 3); no statistically significant interactive effects on soil fertility indicators were observed. Compared to the W system, both the A and R systems increased SOM (16.3–20.0% and 17.5–21.0%, respectively) and AK (5.20–11.1% and 28.7–33.1%, respectively; p < 0.05). Within each cropping system, biochar application increased SOM by 11.9–15.5% and AN by 4.47–15.4% (p < 0.05); combining A and R systems with biochar (A_BC and R_BC) achieved a 34.2–35.6% increase in SOM compared to W_CK. However, no significant differences in TDS were detected among treatments.

Table 3.

Soil pH and soil organic matter (SOM), alkali-hydrolyzable N (AN), available phosphorus (AP), available K (AK), and total soluble salt (TDS) contents under different cropping systems (CS) and biochar application (BC) treatments. Values are represented as mean ± standard error (n = 3). Different uppercase and lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among cropping systems and between biochar treatments within the same cropping system, respectively. F-values show the results of the two-way ANOVA for CS and BC factors; * and *** represent the significance levels of p < 0.05, and p < 0.001, respectively; ns indicates non-significance. W_CK: wheat–maize–wheat system (W) without biochar (CK); W_BC: wheat–maize–wheat system (W) with biochar (BC); A_CK: alfalfa–sweetpotato–wheat system (A) without biochar (CK); A_BC: alfalfa–sweetpotato–wheat system (A) with biochar (BC); R_CK: rapeseed–soybean–wheat system (R) without biochar (CK); R_BC: rapeseed–soybean–wheat system (R) with biochar (BC).

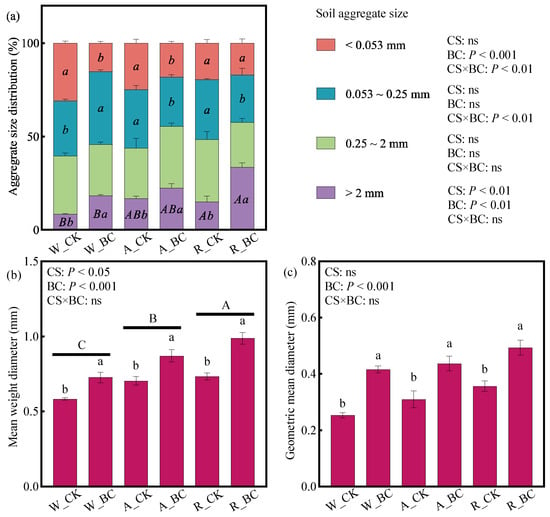

Compared with the W cropping system, the A and R systems increased the proportion of macroaggregates (0.25–2 and >2 mm) by 10.3–22.8% and 22.1–27.3%, respectively. Biochar application (BC) also increased the large macroaggregate (>2 mm) proportion by 67.0–95.6% compared with CK (p < 0.05; Figure 2a). Both cropping system and BC application significantly affected MWD (Figure 2b). MWD was significantly higher under the A and R systems than under the W system, and BC increased MWD by 24.1–34.4% compared with CK (p < 0.05). The GMD pattern was similar to that of MWD (Figure 2c); however, statistical differences in GMD were only detected between biochar amendment treatments.

Figure 2.

(a) Soil aggregate size distribution, (b) mean weight diameter of aggregates, and (c) geometric mean diameter of aggregates under different cropping systems (CS) and biochar application (BC) treatments. Error bars represent the standard error (n = 3). Different uppercase and lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among cropping systems and between biochar treatments within the same cropping system, respectively. ns indicates non-significance in the two-way ANOVA. W_CK: wheat–maize–wheat system (W) without biochar (CK); W_BC: wheat–maize–wheat system (W) with biochar (BC); A_CK: alfalfa–sweetpotato–wheat system (A) without biochar (CK); A_BC: alfalfa–sweetpotato–wheat system (A) with biochar (BC); R_CK: rapeseed–soybean–wheat system (R) without biochar (CK); R_BC: rapeseed–soybean–wheat system (R) with biochar (BC).

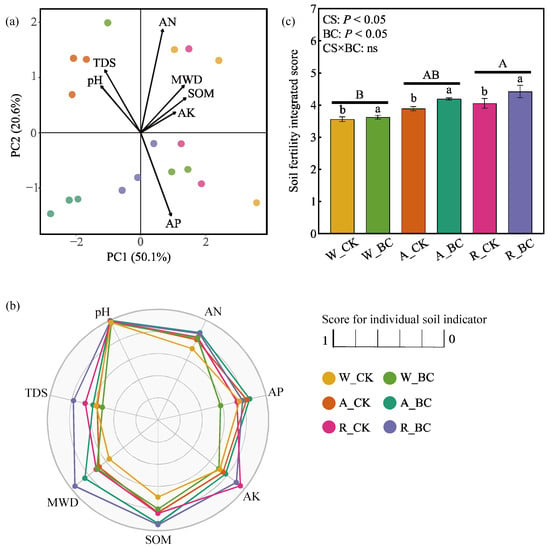

PCA identified SOM, MWD, and pH as the primary drivers of PC1, while AN and AP dominated PC2 (Figure 3a). Both PCA and Pearson correlation analysis (Figure S1) showed SOM correlated positively with MWD but negatively with pH (p < 0.05); whereas AN and AP exhibited inverse correlations (Figure 3a). The differences in scores for individual indicators were most pronounced for MWD and SOM, with R_BC achieving the highest measurements (Figure 3b). The A and R systems yielded significantly higher integrated soil fertility scores than the W system (mean increases: 0.45 and 0.64, respectively; Figure 3c). Biochar application elevated the integrated fertility score by 7.78–9.01% under A and R systems, but had no apparent effect on that under the W system.

Figure 3.

(a) Principal component analysis for the soil fertility indicators, (b) radar map of scores for soil individual indicators, and (c) integrated soil fertility score under different cropping systems (CS) and biochar application (BC) treatments. Error bars in (a) represent the standard error (n = 3). Different uppercase and lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among cropping systems and between biochar treatments within the same cropping system, respectively. ns indicates non-significance in the two-way ANOVA. W_CK: wheat–maize–wheat system (W) without biochar (CK); W_BC: wheat–maize–wheat system (W) with biochar (BC); A_CK: alfalfa–sweetpotato–wheat system (A) without biochar (CK); A_BC: alfalfa–sweetpotato–wheat system (A) with biochar (BC); R_CK: rapeseed–soybean–wheat system (R) without biochar (CK); R_BC: rapeseed–soybean–wheat system (R) with biochar (BC).

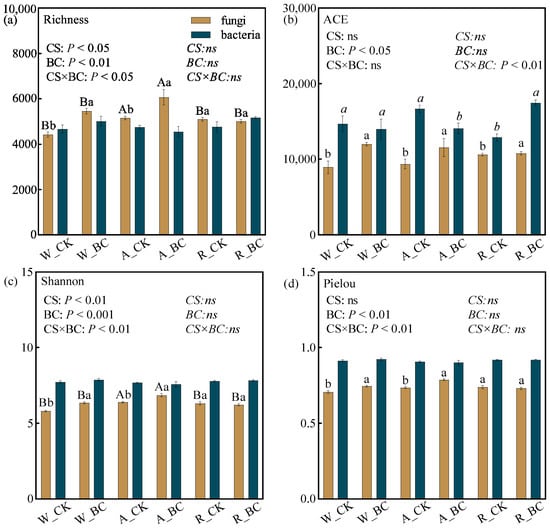

3.3. Soil Microbial Diversity

Both cropping system, biochar application, and their interaction had a significant effect on soil fungal diversity (Figure 4). System A exhibited significantly higher fungal richness and Shannon index compared to the other systems. However, no significant differences occurred in the fungal ACE and Pielou indices (Figure 4b) or in any bacterial diversity indices. Biochar application increased fungal diversity specifically in the W and A systems (p < 0.05), with richness increasing by 911.3–1035, the Shannon index increasing by 0.45–0.55, and the Pielou index increasing by 0.04–0.05. No significant difference in the indices of Simpson and Faith’s PD was observed among the treatments (Table S4).

Figure 4.

Soil microbial diversity indices of (a) Richness, (b) ACE, (c) Shannon, and (d) Pielou under different cropping systems (CS) and biochar application (BC) treatments. Error bars represent the standard error (n = 3). Different uppercase and lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among cropping systems and between biochar treatments within the same cropping system, respectively. Regular and italicized letters denote the significance labels or two-way ANOVA results for the fungi and bacteria, respectively. ns indicates non-significance in the two-way ANOVA. W_CK: wheat–maize–wheat system (W) without biochar (CK); W_BC: wheat–maize–wheat system (W) with biochar (BC); A_CK: alfalfa–sweetpotato–wheat system (A) without biochar (CK); A_BC: alfalfa–sweetpotato–wheat system (A) with biochar (BC); R_CK: rapeseed–soybean–wheat system (R) without biochar (CK); R_BC: rapeseed–soybean–wheat system (R) with biochar (BC).

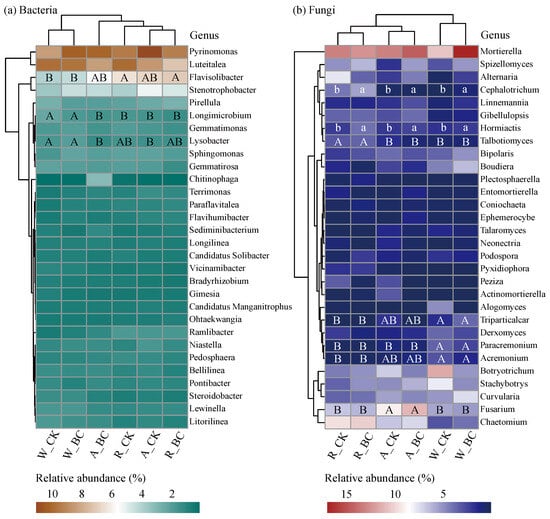

At the phyla level, Acidobacteriota, Pseudomonadota, and Planctomycetota were the dominant phyla of the bacterial community (Figure S1a). Compared with system W, systems A and R exhibited significantly reduced relative abundances of Pseudomonadota and Gemmatimonadota, while significantly increasing Bacteroidota (p < 0.05). Biochar application significantly reduced Verrucomicrobiota and increased Zoopagomycota (p < 0.05). In fungi, Ascomycota and Mucoromycota were the dominant phyla (Figure S1b). At the genus level, bacterial communities were predominantly represented by relatively high-abundance genera such as Pyrinomonas, Luteitalea, and Flavisolibacter, while fungal communities were characterized by high abundances of Mortierella, Fusarium, and Chaetomium (Figure 5). Distinct clustering patterns emerged between System W and the diversified cropping systems (A and R) for both bacterial and fungal communities. The abundance variation of Flavisolibacter (bacteria) and Fusarium (fungi) as affected by the cropping system reached statistical significance (p < 0.05). Additionally, compared with CK, biochar application generally increased the abundance of Mortierella while decreasing the abundance of Alternaria in fungal communities.

Figure 5.

Hierarchical clustering heatmaps visualizing the relative abundance of the top 20 main (a) bacterial and (b) fungal genera. Different uppercase and lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among cropping systems and between biochar treatments within the same cropping system, respectively. W_CK: wheat–maize–wheat system (W) without biochar (CK); W_BC: wheat–maize–wheat system (W) with biochar (BC); A_CK: alfalfa–sweetpotato–wheat system (A) without biochar (CK); A_BC: alfalfa–sweetpotato–wheat system (A) with biochar (BC); R_CK: rapeseed–soybean–wheat system (R) without biochar (CK); R_BC: rapeseed–soybean–wheat system (R) with biochar (BC).

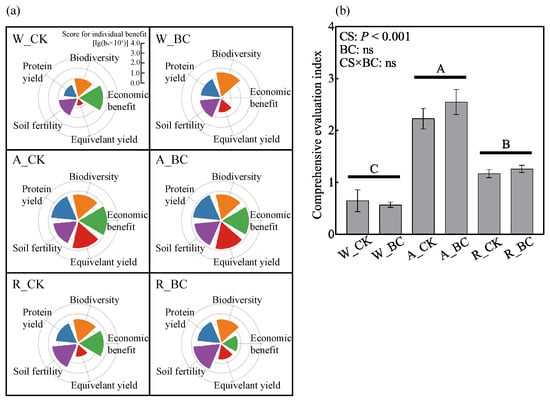

3.4. Comprehensive Evaluation

The comprehensive evaluation demonstrated that the A system achieved the highest benefits in the dimensions of equivalent yield, protein yield, economic benefit, soil fertility, and soil microbial diversity (Figure 6a), resulting in a significantly higher CEI than the other systems (Figure 6b). In contrast, the W system showed clear weaknesses across all dimensions, particularly in equivalent yield and protein yield. The R system also exhibited a significantly higher CEI than the W system, which was primarily attributed to improvements in soil fertility and protein yield. Although biochar application reduced the economic benefit across all systems due to its cost, it tended to increase the CEI under the BC treatment compared to CK in the A and R systems, owing to its positive effect on soil fertility. Overall, the highest CEI was observed under the A_BC treatment.

Figure 6.

(a) Benefit scores for dimensions of soil fertility, microbial diversity, equivalent yield, protein yield, and economic benefit, and (b) comprehensive evaluation index under different cropping systems (CS) and biochar application (BC) treatments. Error bars represent the standard error (n = 3). Different uppercase indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among cropping systems. ns indicates non-significance in the two-way ANOVA. W_CK: wheat–maize–wheat system (W) without biochar (CK); W_BC: wheat–maize–wheat system (W) with biochar (BC); A_CK: alfalfa–sweetpotato–wheat system (A) without biochar (CK); A_BC: alfalfa–sweetpotato–wheat system (A) with biochar (BC); R_CK: rapeseed–soybean–wheat system (R) without biochar (CK); R_BC: rapeseed–soybean–wheat system (R) with biochar (BC).

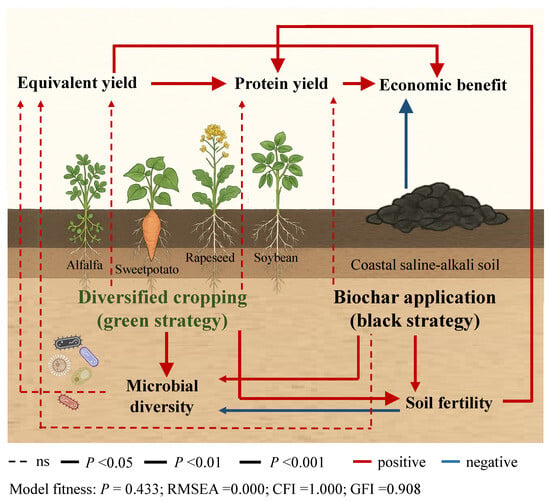

The SEM revealed that both crop diversification (the green strategy) and biochar application (the black strategy) had significant positive effects on soil fertility and microbial diversity benefits, which in turn indirectly influenced equivalent yield, protein yield, and economic benefit (Figure 7). The soil fertility benefit had a significant direct positive effect on protein yield; although, it was associated with a significant reduction in microbial diversity. Furthermore, Pearson correlation analysis indicated that SOM content exhibited significant positive relationships with both the third-season wheat yield and cumulative protein yield, whereas the Random Forest model illustrated that pH and AK serve as dominant factors for influencing cumulative equivalent yield and cumulative protein yield (Figure S2).

Figure 7.

Structural equation modeling results depicting the path model of the effects of diversified cropping and biochar application on the benefit scores of microbial diversity, soil fertility, equivalent yield, protein yield, and economic benefit. Arrows indicate the hypothesized direction of causation. Solid and dashed arrows indicate significant and insignificant relationships, respectively.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Diversified Cropping and Biochar Application on Crop Productivity and Ecosystem Benefits

Average yields of wheat and maize under continuous wheat–maize cropping (W_CK) were 20.7–30.1% lower than the national average (5.12 and 5.27 vs. 6.45 and 7.53 Mg ha−1, respectively; []). This underscores the economic vulnerability of farmers dependent on cereal production and highlights the need for cropping system optimization. Previous studies have shown that incorporating alfalfa, sweetpotato, soybean, or rapeseed into the cropping system can enhance subsequent cereal yields [,,,]. Our results confirm the feasibility of this approach in coastal saline–alkali soils: replacing one year of the wheat–maize cycle with an alfalfa–sweetpotato or rapeseed–soybean rotation increased subsequent wheat yield by 6.60% and 16.2%, respectively, compared with continuous wheat–maize cropping (Table 2). The results supported our first hypothesis. Alternative crops could enhance soil fertility through improved soil structure [], increased microbial diversity [], and enhanced nutrient cycling []. These soil health benefits, reflected in significantly higher soil fertility indices and microbial diversity in diversified systems (Figure 3 and Figure 4), were positively correlated with the equivalent yield (Figure 7). Additionally, in coastal saline–alkali soils, such crops could mitigate salinity stress for subsequent plants by reducing surface evaporation and mobilizing salts, which establishes a more favorable root environment [,].

In the absence of biochar application, incorporation of the alfalfa–sweetpotato rotation achieved the highest equivalent yield and protein yield among the treatments (p < 0.05; Figure 1a,b), and delivered the highest economic benefit compared to the other two cropping systems even in the first season (p < 0.05; Figure 1e). It was reported that, in light-to-moderate saline–alkali soil, alfalfa can maintain osmotic balance via compatible solutes, regulate ion homeostasis through selective ion absorption, enhance antioxidant capacity, and secrete root organic acids to neutralize alkaline ions [,]. Sweetpotato can mitigate secondary salinization by reducing surface evaporation through its dense canopy []. In addition, both alfalfa and sweetpotato demonstrate strong tolerance to nutrient deficiency, either through biological N fixation [] or via traits such as an extensive root system, low nutrient demands, and an efficient photosynthesis mechanism []. Notably, sweetpotato could efficiently utilize the naturally high K levels commonly found in coastal saline–alkali soils, meeting its high K demand without additional fertilizer input []. These advantages reflect the adaptability of alfalfa and sweetpotato cultivated in coastal saline–alkali soil, which supports both yield formation and economic performance. Although including the rapeseed–soybean did not produce a significantly higher equivalent yield compared with continuous wheat–maize cropping, it increased cumulative protein yield by 13.8% (Figure 1b), highlighting its potential to provide substantial protein resources for both humans and livestock [,].

Consistent with previous findings, this study demonstrated that biochar application increased crop yield by 6.36–16.3% within the same cropping system (Table 2). Among the treatments, the combination of alfalfa–sweetpotato rotation with biochar application (A_BC) achieved the highest equivalent yield and protein yield. This was probably attributed to biochar’s role in enhancing SOC content and modulating soil physical, chemical, and biological properties (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5; [,,]). Moreover, biochar application increased N content in sweetpotato and soybean compared to controls (Table S3). This suggested an enhanced N utilization, which also likely contributed to the observed yield increment. However, due to the high cost of biochar, its application resulted in negative economic returns, especially in the first season (Figure 1e). Nevertheless, the study found that a single application of biochar sustained yield improvements over all three seasons, aligning with prior reports on the long-term benefits of biochar on crop productivity [,]. Therefore, with appropriate government subsidies to offset initial costs, integrating biochar application with alternative cropping systems could offer a viable strategy for achieving sustained and economically feasible yield increases over the long term.

4.2. Effects of Diversified Cropping and Biochar Application on Soil Fertility

Increasing SOM is a cornerstone strategy for improving soil fertility, given its central role in mediating the complex network of soil interactions [,]. In China, the topsoil of saline–alkali lands holds an estimated 217 Tg of SOM, with the potential for a 30% increase through remediation []. However, achieving this in saline–alkali soils is challenging. SOM formation is often constrained by degraded soil structure, which reduces protective mechanisms for organic matter [,,], and by stimulative solubility and leaching under high-pH conditions []. This challenge is evident in our results. Under conventional wheat–maize cropping (W_CK), the SOM content was 9.94 g kg−1, markedly lower than the eastern China cropland average of 30.0 g kg−1 []. Furthermore, after three cropping seasons, the SOM under continuous wheat–maize had decreased by 1.70 g kg−1 from baseline levels. This declining trend aligns with findings by Xiang et al. [], who reported a net loss of SOC in a cereal-cropped coastal saline–alkali soil. The degradation likely occurs because substantial N fertilization in wheat–maize systems meets the stoichiometric demands for microbial decomposition of SOC [,], while the input of plant-derived C is insufficient to offset these losses.

Introducing diversified rotations offered a significant solution. Replacing continuous wheat–maize with alfalfa–sweetpotato and rapeseed–soybean rotations increased SOM content by 16.3–21.0% (Table 3). This improvement can be attributed to several mechanisms. First, these alternative systems reduced cumulative synthetic N application by 13.3–28.3% (120–255 kg N ha−1), which may have alleviated the microbial decomposition of SOC [,]. Second, the alternative crops enhanced root-C input through greater root biomass from deep root systems [] and the secretion of substantial root exudates, such as polysaccharides and amino acids [,]. Additionally, incorporating diversified rotations lowered soil pH compared to conventional cropping (Table 3), possibly due to the secretion of organic acids by the alternative crops [,]. This pH reduction could, in turn, decrease SOM solubility, thereby mitigating leaching losses [].

The benefits of diversification extended to soil structure. The alternative cropping system significantly increased the proportion of macroaggregates (>2 mm) and the MWD of water-stable aggregates (Figure 2) compared with the conventional system. Macroaggregates provide physical protection for SOC, and numerous studies have linked higher SOM content with increased MWD [,]. Our study corroborates this (Figure 3a and Figure S2), and linear regression could show that a 1 mm increase in MWD corresponded to a 7.76 g kg−1 increase in SOM (p < 0.01), indicating that diversified cropping enhances SOM levels by improving aggregate protection. This improvement in aggregation resulted from both the increased SOC acting as a binding agent [] and the physical effects of the crops themselves. The extensive root systems of alfalfa and sweetpotato entangle soil particles [,], while specific root exudates from rapeseed and soybean promote the growth of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and the production of glomalin-related soil protein, which stabilizes aggregates [,,]. Thus, even without exogenous C addition, incorporating these alternative crops presents a promising strategy for SOM enhancement.

Biochar application offers another rapid pathway for increasing SOM. Its polyaromatic structure provides a direct input of stable C [], leading to well-documented short-term SOM increases [,,]. Consistent with these findings, our study showed that biochar application increased SOM by 11.9–15.5% across all cropping systems (Table 3), which contributed to the improvements in the integrated soil fertility score (Figure 3). This rapid SOM increase also contributed to soil structure, as evidenced by a significantly higher MWD in biochar-amended soils (Figure 2b). Biochar’s highly porous structure provides sites for the physical entanglement of soil particles, fungal hyphae, and plant roots, facilitating macroaggregate formation []. While unmodified, typically alkaline biochar can exacerbate high pH in saline–alkali soils [], the acid-modified biochar used in our trial had no significant effect on soil pH (Table 3), which was supported by other studies [].

Although a lack of statistically significant interactive effects between the cropping system and biochar application, their combined application yielded the greatest benefits on soil fertility. The treatments combining alfalfa–sweetpotato and rapeseed–soybean systems with biochar (A_BC and R_BC) achieved a 34.2–35.6% increase in SOM compared to conventional cropping (W_CK; Table 3), which might be resulted from the enhanced soil physical protection mechanisms under alternative cropping [,] strengthened the SOC sequestration efficacy under biochar application. These treatments also resulted in the highest levels of soil AN, AP, and AK, as well as the highest integrated fertility score (Table 3, Figure 3). This synergy is likely due to the combined effects of root-mediated nutrient activation by the alternative crops [] and the enhanced nutrient retention capacity of biochar [,]. These results highlight the potent short-term effect of combining diversified cropping with biochar application to elevate overall soil fertility, creating a more favorable environment for subsequent crops, which was in line with our second hypothesis.

4.3. Effects of Diversified Cropping and Biochar Application on Microbial Diversity and Communities

Our results indicated that introducing diversified rotations (alfalfa–sweetpotato and rapeseed–soybean) into coastal saline–alkali soils significantly reshaped soil microbial communities, with distinct responses between fungi and bacteria (Figure 4, Figure 5, and Figure S1). These findings align with and extend previous research on how cropping systems influence soil microbiomes under salinity stress [,,]. The significant increase in fungal richness and Shannon index as affected by alternative cropping systems contrasts with the lack of response in bacterial diversity (Figure 4). This differential sensitivity is consistent with observations in intercropping systems in coastal saline–alkali soil, where fungal alpha diversity often responds more strongly than bacterial diversity to changes in root exudates and litter quality []. Fungi, particularly saprotrophic taxa, are often more responsive to shifts in C inputs and soil microenvironments created by alternative crops []. While bacteria may be less sensitive to such rotational perturbations []. The biochar application or its interactive effects with the cropping system exhibited significant effects on the richness, Pielou, and Shannon index of fungi. This highlighted that synergistic management can effectively improve the microbial diversity in coastal saline–alkali soil [].

Cropping systems also induced marked shifts in bacterial composition (Figure 5 and Figure S1). At the phyla level, incorporating alfalfa–sweetpotato and rapeseed–soybean rotations significantly reduced the relative abundance of Pseudomonadota and Gemmatimonadota while increasing Bacteroidota (p < 0.05). This restructuring may have resulted from the altered soil C level and nutrient availability (Table 3). Similar reductions in Pseudomonadota under diversified systems have also been reported in a recent study []. The enrichment of Bacteroidota-a phylum involved in decomposing polysaccharides and exhibiting stronger salt tolerance [,], which might reflect the response of microbial composition to the root exudates from alternative crops. Notably, cropping systems significantly altered Flavisolibacter abundance at the genus level, with A and R systems increasing relative abundance by 47.1% and 62.0%, respectively, compared with W (Figure 5a). As documented by its role in organic matter decomposition and N fixation [], this enrichment likely reflects greater root exudate diversity and enhanced nutrient availability for crops. The microbial shift may further facilitate soil aggregation through extracellular polymeric substance production, which counters soil degradation []. These findings align with observed elevations of SOM, AP, and AK contents under diversified systems (Table 3), confirming that Flavisolibacter recruitment contributes to improved saline soil fertility through diversified cropping.

The fungi were dominated by the phylum Ascomycota (Figure S1b), which was in agreement with previous studies conducted in saline–alkali soil [,,]. At the genus level, system A exhibited significantly increased Fusarium abundance (Figure 5b). Although Fusarium was recognized as a plant pathogen, it had also been shown to play roles in SOM turnover and enhancing crop salt tolerance []. This duality highlights the necessity of selecting alfalfa and sweetpotato genotypes with Fusarium resistance to safeguard yield performance [].

Biochar application significantly reduced Verrucomicrobiota and increased Zoopagomycota at the phyla level (Figure S1), suggesting biochar-driven selection for specific functional guilds, possibly by improving habitat conditions [,]. At the genus level, biochar application significantly increased Mortierella abundance while decreasing Alternaria in fungal communities (Figure 5b). As a keystone taxon mediating soil physicochemical properties and producing stress-alleviating hormones [,], Mortierella likely enhances crop resilience in saline conditions. Conversely, diminished Alternaria may mitigate pathogen pressure, as this genus includes multiple crop pathogens []. This dual restructuring demonstrates biochar’s capacity to foster beneficial fungi while suppressing detrimental taxa. Moreover, the most substantial improvements in fungal diversity and soil fertility were observed under the combined treatment of alfalfa–sweetpotato rotation and biochar (A_BC). This suggests a synergistic effect where root-mediated nutrient activation by deep-rooted crops complements biochar’s ability to retain nutrients and improve the soil physicochemical properties. These findings underscore the potential of tailored crop diversification integrated with biochar application to regenerate saline–alkali soils by mediating the microbial community.

4.4. Comprehensive Evaluation and Implications

The comprehensive evaluation demonstrates that transitioning from a continuous wheat–maize cropping system to the incorporation of diversified rotations achieved synergistic improvements across agronomic, economic, and microbial diversity dimensions in coastal saline–alkali soils (Figure 6). The significantly lower comprehensive index for the conventional system (W_CK) aligns with previous studies indicating that simplified monocultures without soil amendments often degrade soil health and system sustainability [,].

Among the diversified systems, the alfalfa–sweetpotato rotation achieved the highest individual scores and the top CEI (Figure 6). Although alfalfa is a perennial, this study innovatively combined it with sweetpotato; the results confirm the effectiveness of this system in balancing productivity with ecological benefits. Furthermore, while biochar application enhanced scores for equivalent yield, protein yield, and soil fertility, the associated increase in costs reduced economic returns (Figure 6 and Figure 7). This presents a potential barrier to widespread farmer adoption. However, this challenge could be mitigated through targeted government subsidies or C credit schemes, recognizing the long-term environmental benefits and C sequestration potential of biochar-amended soils [,].

Overall, the results highlight the feasibility of an integrated strategy, i.e., “green” (crop diversification) and “black” (biochar amendment), for the amelioration and utilization of coastal saline–alkaline soil (Figure 6 and Figure 7). This approach supports the relevant national strategy of “adapting crops to the land” combined with “adapting the land to the crops” []. However, this study was constrained by its short-term duration, single-site design, and lack of supplementary fertilization. Future research should focus on the long-term stability and legacy of these systems, the feasibility of implementing this approach on broader scales, and the potential to increase crop productivity by applying secondary and micronutrients.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that strategically incorporating one rotation of diversified crops (alfalfa–sweetpotato and rapeseed–soybean) into a conventional wheat–maize system is a viable approach to synergistically enhance grain productivity, farm profitability, and ecological resilience in coastal saline–alkali dryland soils. Compared to conventional practices, this diversification approach achieved significantly higher economic returns while simultaneously increasing the yield of subsequent cereal crops. Crucially, the diversified rotations substantially improved soil fertility and structure, and enhanced soil biological diversity. The integration of acid-modified biochar with diversified cropping further amplified these benefits in soil fertility and crop productivity. However, its high initial cost remains a barrier to farmer adoption. In summary, this research indicates the potential of an integrated “green” (crop diversification) and “black” (biochar amendment) strategy, offering a practical model to support national strategies for saline–alkali dryland utilization. Future efforts should focus on the long-term stability and legacy of these systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture15232492/s1, Figure S1: Relative abundance of dominate phyla for bacteria and fungi under different cropping systems and biochar application treatments; Figure S2: Pearson correlation analysis showing relationships among soil properties and crop yields, and Random Forest model showing the importance of soil parameters for predicting third-season wheat yield, cumulative equivalent yield, and cumulative protein yield; Table S1: Agricultural cost constitution of each cropping season under different cropping systems and biochar application treatments; Table S2: Protein content for different crops; Table S3: The contents of nutrient elements (N, P, K) of the three crops; Table S4: Soil microbial diversity indices of Chao1, Simpson, and Faith’s PD under different cropping systems and biochar application treatments; Table S5: Relative abundance of dominate phyla for bacteria and fungi under different cropping systems and biochar application treatments. References [,,,,] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.X., X.Q. and J.W. (Jidong Wang); methodology, D.Y., W.L. and J.W. (Junzhe Wang); software, X.Q., J.Y. and C.J.; validation, Y.Z. and J.W. (Jidong Wang); formal analysis, X.Q., C.X., Z.Y. and D.Y.; investigation, D.Y., X.Q., J.W. (Junzhe Wang), J.Y. and C.J.; resources, Y.Z., J.W. (Jidong Wang) and C.X.; data curation, X.Q., C.X. and W.L.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Q. and C.X.; writing—review and editing, J.W. (Jidong Wang) and Y.Z.; visualization, X.Q. and C.X.; supervision, Y.Z. and J.W. (Jidong Wang); project administration, C.X., J.W. (Jidong Wang) and Y.Z.; funding acquisition, C.X., J.W. (Jidong Wang), Y.Z. and C.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Basic Research Program of Jiangsu (BK20230076 and BK20230749), the Jiangsu Agriculture Science and Technology Innovation Fund (CX(23)1019), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42477314, 42377338, and 42577335), the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-10-Sweetpotato), the National Key Research and Development Program (2023YFD1901102-04), and the Key Research and Development Project of Jiangsu Province (BE2021378).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments that significantly improved the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. The supporting source had no involvement in the submission of the report for publication.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SOM | Soil organic matter |

| AN | Alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen |

| AP | Available phosphorus |

| AK | Available potassium |

| TDS | Total soluble salt |

| MWD | Mean weight diameter |

| GMD | Geometric mean diameter |

| CEI | Comprehensive evaluation index |

| CS | Cropping system |

| BC | Biochar application |

| W | Wheat–maize–wheat cropping system |

| A | Alfalfa–sweetpotato–wheat cropping system |

| R | Rapeseed–soybean–wheat cropping system |

References

- Muller, A.; Schader, C.; Scialabba, E.H.; Brüggemann, J.; Isensee, A.; Erb, K.H.; Smith, P.; Klocke, P.; Leiber, F.; Stolze, M. Strategies for feeding the world more sustainably with organic agriculture. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.O.; de Barros, P.R.; Schulenburg, A.N.; Tully, K.L. Coastal stressors reduce crop yields and alter soil nutrient dynamics in low-elevation farmlands. Discov. Agric. 2025, 3, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, A.; Azapagic, A.; Shokri, N. Global predictions of primary soil salinization under changing climate in the 21st century. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Z.; Leng, Y.; Xu, Z.; Tu, L.; Wang, C.; Li, S.; Wu, S.; Huang, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, J.; et al. Location-optimized remediation measures for soil multifunctionality and carbon sequestration of saline-alkali land in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 519, 146017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodur, S.; Shrestha, U.B.; Maraseni, T.N.; Deo, R.C. Environmental and economic impacts and trade-offs from simultaneous management of soil constraints, nitrogen and water. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 960–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hu, Y.; Xia, Y.; Zheng, S.; Ma, C.; Rui, Y.; He, H.; Huang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Ge, T.; et al. Contrasting pathways of carbon sequestration in paddy and upland soils. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 2478–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daliakopoulos, I.N.; Tsanis, I.K.; Koutroulis, A.; Kourgialas, N.N.; Varouchakis, A.E.; Karatzas, G.P.; Ritsema, C.J. The threat of soil salinity: A European scale review. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 573, 727–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulaiti, A.; She, D.; Liu, Z.; Sun, X.; Wang, H. Application of biochar and polyacrylamide to revitalize coastal saline soil quality to improve rice growth. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 18731–18747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, J.; Wiesenberg, G.L.B.; Hirte, J. The impact of climate and potassium nutrition on crop yields: Insights from a 30-year Swiss long-term fertilization experiment. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 372, 109100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. Regional model and mechanism of rural labor transfer response to rapid urbanization in eastern coastal China. J. Nat. Resour. 2013, 28, 1–9. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Fu, T.; Tang, S.; Liu, J. Effects of saline water irrigation on winter wheat and its safe utilization under a subsurface drainage system in coastal saline-alkali land of Hebei Province, China. Irrig. Sci. 2023, 41, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Yuan, H.; Shi, N.; Sun, Z.; Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Li, B.; Li, S.; Liu, Z. Effects of phosphate application rate on grain yield and nutrition use of summer maize under the coastal saline-alkali land. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Development and Reform Commission Price Department; Price Cost Investigation Center. National Agricultural Product Cost-Benefit Data Compilation 2021; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2021; ISBN 978-7-5037-9699-9. (In Chinese)

- Marcos-Pérez, M.; Sánchez-Navarro, V.; Martinez-Martinez, S.; Martínez-Mena, M.; García, E.; Zornoza, R. Intercropping organic melon and cowpea combined with return of crop residues increases yields and soil fertility. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 43, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xiong, J.; Du, T.; Ju, X.; Gan, Y.; Li, S.; Xia, L.; Shen, Y.; Pacenka, S.; Steenhuis, T.S.; et al. Diversifying crop rotation increases food production, reduces net greenhouse gas emissions and improves soil health. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Yu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, L.; Xu, D.; Peng, X. Biochar modification methods and mechanisms for salt-affected soil and saline-alkali soil improvement: A review. Soil Use Manag. 2024, 40, e12992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah-Antwi, C.; Kwiatkowska-Malina, J.; Thornton, S.F.; Fenton, O.; Malina, G.; Szara, E. Restoration of soil quality using biochar and brown coal waste: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 722, 137852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agegnehu, G.; Nelson, P.N.; Bird, M.I. Crop yield, plant nutrient uptake and soil physicochemical properties under organic soil amendments and nitrogen fertilization on Nitisols. Soil Tillage Res. 2016, 160, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Chen, X.; Chi, G. Fungal community is more sensitive to the short-term application of biochar in saline farmland soil than bacterial community. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 212, 106219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egamberdieva, D.; Alaylar, B.; Kistaubayeva, A.; Wirth, S.; Bellingrath-Kimura, S.D. Biochar for improving soil biological properties and mitigating salt stress in plants on salt-affected soils. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2022, 53, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijbeek, R.; Pronk, A.A.; van Ittersum, M.K.; Verhagen, A.; Ruysschaert, G.; Bijttebier, J.; Zavattaro, L.; Bechini, L.; Schlatter, N.; ten Berge, H.F.M. Use of organic inputs by arable farmers in six agro-ecological zones across Europe: Drivers and barriers. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2019, 275, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, V.; Raimondi, G.; Toffanin, A.; Maucieri, C.; Borin, M. Agronomic management strategies to increase soil organic carbon in the short-term: Evidence from on-farm experimentation in the Veneto region. Plant Soil 2023, 491, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legba, E.C.; Dossou, L.; Honfoga, J.; Pawera, L.; Srinivasan, R. Productivity and profitability of maize-mungbean and maize-chili pepper relay intercropping systems for income diversification and soil fertility in southern Benin. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, G.; van Dam, J.; Yang, X.; Ritsema, C.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Du, T.; Kang, S. Diversified crop rotations improve crop water use and subsequent cereal crop yield through soil moisture compensation. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 294, 108721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whippo, C.W.; Hendrickson, J.R.; Clemensen, A.K.; Grusak, M.A. Legacy effects of alfalfa monocultures or annual crop/alfalfa mixtures on subsequent corn yield and quality. Agrosyst. Geosci. Environ. 2025, 8, e70114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasisi, A.; Liu, K. A global meta-analysis of pulse crop effect on yield, resource use, and soil organic carbon in cereal- and oilseed-based cropping systems. Field Crops Res. 2023, 294, 108857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, C.; Tan, X.; Lou, H.; Wang, X.; Shao, D.; Ning, N.; Kuai, J.; Wang, J.; Xu, Z.; et al. Developing diversified forage cropping systems for synergistically enhancing yield, economic benefits, and soil quality in the Yangtze River Basin. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 365, 108929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-S.; Ren, H.-L.; Wei, Z.-W.; Wang, Y.-W.; Ren, W.-B. Effects of neutral salt and alkali on ion distributions in the roots, shoots, and leaves of two alfalfa cultivars with differing degrees of salt tolerance. J. Integr. Agric. 2017, 16, 1800–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, C.C.; Tejedor, M.; Díaz, F.; Rodríguez, C.M. Effectiveness of sand mulch in soil and water conservation in an arid region, Lanzarote, Canary Islands, Spain. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2005, 60, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Rahaman, E.; Asch, F. Potassium content is the main driver for salinity tolerance in sweet potato before tuber formation. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2022, 208, 645–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Li, H. Effect of nitrogen on the species and contents of organic acids in root exudates of different soybean cultivars. J. Plant Nutr. Fert. 2007, 13, 398–403. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Qu, W.; Lin, Y.; Wang, L.; Lin, G.; Zuo, Q. Response of rapeseed growth to soil salinity content and its improvement effect on coastal saline soil. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1601627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DB32/T 4518-2023; Technical Regulation for Annual Rotation of Alfalfa and Silage Maize. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2023. (In Chinese)

- NY/T 3086-2017; Code of Practice for Yangtze River Valley Sweet Potato Production. China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2017. (In Chinese)

- Dong, L.; Wang, J.; Shen, M.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Li, C.; Lu, C. Biochar combined with nitrogen fertilizer affects soil properties and wheat yield in medium-low-yield farmland. Soil Use Manag. 2021, 38, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R. Methods of Soil and Agro-Chemical Analysis, 3rd ed.; China Agricultural Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2000; ISBN 9787801199256. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tisdall, J.M.; Oades, J.M. Organic matter and water-stable aggregates in soils. J. Soil Sci. 1982, 33, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhuang, M.; Liang, X.; Lam, S.K.; Chen, D.; Malik, A.; Li, M.; Lenzen, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, R.; et al. Localized nitrogen management strategies can halve fertilizer use in Chinese staple crop production. Nat. Food 2024, 5, 825–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Jia, J.; Liao, W.; Amsili, J.P.; Schneider, R.L.; van Es, H.M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J. Applicability of soil health assessment for wheat-maize cropping systems in smallholders’ farmlands. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 353, 108558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idowu, O.J.; van Es, H.M.; Abawi, G.S.; Wolfe, D.W.; Ball, J.I.; Gugino, B.K.; Moebius, B.N.; Schindelbeck, R.R.; Bilgili, A.V. Farmer-oriented assessment of soil quality using field, laboratory, and VNIR spectroscopy methods. Plant Soil 2008, 307, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congreves, K.A.; Hayes, A.; Verhallen, E.A.; Van Eerd, L.L. Long-term impact of tillage and crop rotation on soil health at four temperate agroecosystems. Soil Tillage Res. 2015, 152, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faith, D.P. Conservation evaluation and phylogenetic diversity. Biol. Conserv. 1992, 61, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, J.; Hou, R.; Dungait, J.A.J.; Zhou, G.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tian, J.; Cui, Z.; Zhang, F.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M. Conservation agriculture improves soil health and sustains crop yields after long-term warming. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.L. Impact of preceding crop on alfalfa competitiveness with weeds. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2015, 32, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, R.P.; Griffin, T.S.; Honeycutt, C.W. Rotation and cover crop effects on soilborne potato diseases, tuber yield, and soil microbial communities. Plant Dis. 2010, 94, 1491–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Yuan, J.; Tang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y. Long-term organic fertilization strengthens the soil phosphorus cycle and phosphorus availability by regulating the pqqC- and phoD-harboring bacterial communities. Microb. Ecol. 2023, 86, 2716–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Dong, J.; Nie, Y.; Chang, C.; Yin, Q.; Lv, M.; Lu, Q.; Liu, Y. Alfalfa plant age (3 to 8 years) affects soil physicochemical properties and rhizosphere microbial communities in saline−alkaline soil. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarangi, S.K.; Maji, B.; Sharma, P.C.; Digar, S.; Mahanta, K.K.; Burman, D.; Mandal, U.K.; Mandal, S.; Mainuddin, M. Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) cultivation by zero tillage and paddy straw mulching in the saline soils of the Ganges Delta. Potato Res. 2020, 64, 277–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W. MsSPL12 is a positive regulator in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) salt tolerance. Plant Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamkhi, I.; Cheto, S.; Geistlinger, J.; Zeroual, Y.; Kouisni, L.; Bargaz, A.; Ghoulam, C. Legume-based intercropping systems promote beneficial rhizobacterial community and crop yield under stressing conditions. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 183, 114958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapakhova, Z.; Raissova, N.; Daurov, D.; Zhapar, K.; Daurova, A.; Zhigailov, A.; Zhambakin, K.; Shamekova, M. Sweet potato as a key crop for food security under the conditions of global climate change: A review. Plants 2023, 12, 2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon-Miquel, G.; Reckling, M.; Lampurlanés, J.; Plaza-Bonilla, D. A win-win situation—Increasing protein production and reducing synthetic N fertilizer use by integrating soybean into irrigated Mediterranean cropping systems. Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 146, 126817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Dai, W.; Chen, B.-Y.; Cai, G.; Wu, X.; Yan, G. Research progress on the effect of nitrogen on rapeseed between seed yield and oil content and its regulation mechanism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Ban, G.; Luo, Y.; Wang, J.; Peng, D.; Liang, R.; He, T.; Wang, Z. Biochar effects on aggregation and carbon-nitrogen retention in different-sized aggregates of clay and loam soils: A meta-analysis. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 247, 106365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.P.; Kammann, C.; Hagemann, N.; Leifeld, J.; Bucheli, T.D.; Sánchez Monedero, M.A.; Cayuela, M.L. Biochar in agriculture—A systematic review of 26 global meta-analyses. GCB Bioenergy 2021, 13, 1708–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalu, S.; Simojoki, A.; Karhu, K.; Tammeorg, P. Long-term effects of softwood biochar on soil physical properties, greenhouse gas emissions and crop nutrient uptake in two contrasting boreal soils. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 316, 107454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ye, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Pan, G.; Kibue, G.W.; Zheng, J.; Zheng, J. Sustainable biochar effects for low carbon crop production: A 5-crop season field experiment on a low fertility soil from Central China. Agric. Syst. 2014, 129, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Soussana, J.F.; Angers, D.; Schipper, L.; Chenu, C.; Rasse, D.P.; Batjes, N.H.; van Egmond, F.; McNeill, S.; Kuhnert, M.; et al. How to measure, report and verify soil carbon change to realise the potential of soil carbon sequestration for atmospheric greenhouse gas removal. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 26, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesmeier, M.; Urbanski, L.; Hobley, E.; Lang, B.; von Lützow, M.; Marin-Spiotta, E.; van Wesemael, B.; Rabot, E.; Ließ, M.; Garcia-Franco, N.; et al. Soil organic carbon storage as a key function of soils—A review of drivers and indicators at various scales. Geoderma 2019, 333, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emran, M.; Doni, S.; Macci, C.; Masciandaro, G.; Rashad, M.; Gispert, M. Susceptible soil organic matter, SOM, fractions to agricultural management practices in salt-affected soils. Geoderma 2020, 366, 114257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.-W.; Wang, C.; Xue, R.; Wang, L.-J. Effects of salinity on the soil microbial community and soil fertility. J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18, 1360–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarolli, P.; Luo, J.; Park, E.; Barcaccia, G.; Masin, R. Soil salinization in agriculture: Mitigation and adaptation strategies combining nature-based solutions and bioengineering. iScience 2024, 27, 108830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Mostofa, K.M.G.; Mohinuzzaman, M.; Teng, H.H.; Senesi, N.; Senesi, G.S.; Yuan, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.-L.; et al. Solubility characteristics of soil humic substances as a function of pH: Mechanisms and biogeochemical perspectives. Biogeosciences 2025, 22, 1745–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Kooch, Y.; Song, K.; Zheng, S.; Wu, D. Remote estimation of soil organic carbon under different land use types in agroecosystems of Eastern China. CATENA 2023, 231, 107369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Shi, W.; Jing, Z.; Guan, Y.; Yang, F.; Wang, G.; Sun, X.; Li, J.; Li, Q.; Zhang, H. Exogenous calcium-induced carbonate formation to increase carbon sequestration in coastal saline-alkali soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, W.; Xu, X.; Xu, C.; Ju, C.; Li, Q.; Liu, W.; Luo, Y.; Du, H.; Chen, X. Inorganic N fertilization reduces soil organic carbon in bamboo forests in China. Front. Earth Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Wan, P.; Chai, N.; Li, M.; Wei, H.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Filimonenko, E.; Almwarai Alharbi, S.; et al. Contrasting impacts of plastic film mulching and nitrogen fertilization on soil organic matter turnover. Geoderma 2023, 440, 116714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidi, P.; Vittori Antisari, L.; Marè, B.T.; Vianello, G.; Falsone, G. Effects of Alfalfa on Aggregate Stability, Aggregate Preserved-C and Nutrients in Region Mountain Agricultural Soils 1 Year After its Planting. Land Degrad. Dev. 2017, 28, 2408–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Zhao, J.; Lu, Z.; Li, M.; Yang, J.; Fullen, M.; Li, Y.; Fan, M. Maize−soybean intercropping increases soil nutrient availability and aggregate stability. Plant Soil 2023, 506, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.; Hussain, S.; Chen, J.; Hu, F.; Liu, J.; He, Y.; Yang, M. Cover crop root-derived organic carbon influences aggregate stability through soil internal forces in a clayey red soil. Geoderma 2023, 429, 116271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minemba, D.; Gleeson, D.B.; Veneklaas, E.; Ryan, M.H. Variation in morphological and physiological root traits and organic acid exudation of three sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) cultivars under seven phosphorus levels. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 256, 108572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Tang, L.; Guo, W.; Wang, D.; Sun, Y.; Guo, C. Oxalic acid secretion alleviates saline-alkali stress in alfalfa by improving photosynthetic characteristics and antioxidant activity. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 208, 108475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, J.; Wu, D.; Li, C.; Wang, L.; Ji, C.; Zhang, Y.; Ai, Y. Optimizing organic amendment applications to enhance carbon sequestration and economic benefits in an infertile sandy soil. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 303, 114129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dong, L.; Shangguan, Z. Appropriate N addition improves soil aggregate stability through AMF and glomalin-related soil proteins in a semiarid agroecosystem. Land Degrad. Dev. 2022, 34, 710–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudina, A.; Kuzyakov, Y. Dual nature of soil structure: The unity of aggregates and pores. Geoderma 2023, 434, 116478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Pang, Z.; Wang, E. Winter cover crops affect aggregate-associated carbon, nitrogen and enzyme activities from black soil cropland. Agronomy 2024, 14, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.Z.; Liu, W.J.; Yang, R.; Chang, X.X. Changes in soil aggregate, carbon, and nitrogen storages following the conversion of cropland to alfalfa forage land in the marginal oasis of northwest China. Environ. Manag. 2009, 43, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura, M.; Alberti, G.; Panzacchi, P.; Vedove, G.D.; Miglietta, F.; Tonon, G. Biochar mineralization and priming effect in a poplar short rotation coppice from a 3-year field experiment. Biol. Fert. Soils 2018, 55, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Du, Z.; Lou, Y.; He, X. A one-year short-term biochar application improved carbon accumulation in large macroaggregate fractions. CATENA 2015, 127, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Schulz, H.; Brandl, S.; Miehtke, H.; Huwe, B.; Glaser, B. Short-term effect of biochar and compost on soil fertility and water status of a Dystric Cambisol in NE Germany under field conditions. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2012, 175, 698–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaufmann, E.; Schmid, H.; Hülsbergen, K.-J. Soil carbon accrual and yield response to biochar and compost in a four-year organic field study. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2025, 131, 213–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Liu, Y.; Yan, J.; Hina, K.; Hussain, Q.; Qiu, T.; Zhu, J. Revitalizing coastal saline-alkali soil with biochar application for improved crop growth. Ecol. Eng. 2022, 179, 106594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, A.; Shahzad, S.M.; Chatterjee, N.; Arif, M.S.; Farooq, T.H.; Altaf, M.M.; Tufail, M.A.; Dar, A.A.; Mehmood, T. Nitrous oxide emission from agricultural soils: Application of animal manure or biochar? A global meta-analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 285, 112170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Kieffer, C.; Ren, W.; Hui, D. How much is soil nitrous oxide emission reduced with biochar application? An evaluation of meta-analyses. GCB Bioenergy 2022, 15, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchers, A.; Pieler, T. Programming pluripotent precursor cells derived from Xenopus embryos to generate specific tissues and organs. Genes 2010, 1, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Liu, X.; Zhu, D.; Su, H.; Guo, K.; Sun, G.; Li, X.; Sun, L. Crop diversity promotes the recovery of fungal communities in saline-alkali areas of the Western Songnen Plain. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1091117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Z. Organic amendment application influence soil organism abundance in saline alkali soil. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2013, 54, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Riaz, M.; Babar, S.; Eldesouki, Z.; Liu, B.; Xia, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Xia, X.; Jiang, C. Alterations in the composition and metabolite profiles of the saline-alkali soil microbial community through biochar application. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 352, 120033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]