Abstract

The aim of this study was to gain a better understanding of the effects of oats, with and without hulls, on the histomorphometry parameters of the jejunum and ileum, the viscosity of the jejunal content and the ileal microbiota composition of broilers. A floor pen trial was carried out with 576 one-day-old Ross 308 broilers. Aside from a maize–soybean-based control diet (C), the two other treatments contained whole oats (WO) or dehulled oats (DO) in the starter (10%), grower (10%) and finisher (20%) phases. On day 39, eight chickens per treatment were slaughtered, and gut samples were collected for histology, jejunal chymus viscosity and ileal chymus microbiota analysis. Feeding the WO and DO diets increased the thickness of lamina propria in the jejunum, without affecting villus height and crypt depth. WO increased, while DO decreased, villus height in the ileum, and both forms of oats decreased crypt depth. The oat treatments failed to result in significant changes in the jejunal viscosity, although DO tended to increase this parameter. As a result of WO and DO treatments, the Lactococcus genus showed a decreasing tendency in the ileum. In conclusion, feeding WO and DO to broiler chickens results only in slight changes in the small intestine.

1. Introduction

Oats (Avena sativa) is among the 10 most produced cereal crops in the world, according to FAOSTAT data []. Climate change will challenge crop production globally, and the availability of locally suitable crop varieties will help farmers to prepare and respond to the challenges []. Increasing tendencies of extreme weather events could be unfavourable for certain crops like maize []. Oats have been a favourite cereal for humans, ruminants and horses for a long time, but it has not been used widely in poultry nutrition, because of its comparatively high fibre and low energy content []. Many studies have demonstrated that moderate amounts of structural fibres, like oat hulls, improve gizzard function []. Frølich and Nyman [] examined the dietary fibre fractions of oats. The total dietary fibre content of the hull-less oat (pericarp, dough, germ, aleurone, endosperm) is around 11.5%, of which 23% is the soluble fibre fraction, mainly β-glucan. The hulls take around 20–22% of the weight of the grain containing high dietary fibre (83.9%), mainly arabinoxylans, mixed-linked β-glucans (1.3–1.4), and cellulose []. Concerning the different fibre fractions of oats, particular interest has been dedicated to the soluble fibre components, mainly β-glucans []. Its concentration in the whole grain is around 3.6–5.7% [,]. β-glucans are mainly found in the subaleuron layer and in the cell wall of the endosperm []. According to the recent research results, the β-glucan content of the hulls is low (1.2 mg/g) []. Németh et al. [] found great differences also in the fibre composition of hull-less oat varieties, especially in the soluble dietary fibre and β-glucan contents, which were 2.89–4.98% and 3.60–6.32%, respectively. The β-glucans of cereal grains can increase the viscosity of the gut content but play also as prebiotics and have positive effects on gut health.

It is well known that oat hulls is an efficient gizzard stimulator in birds [,,,]. On the other hand, the effects of oat’s soluble β-glucan content in the poultry have not been clarified yet. The feed industry uses exogenous β-glucanase routinely, which certainly decreases gut viscosity [] but since the soluble fibre fractions are not measured routinely, there is no information on what happens in the gut after the enzymatic degradation of the soluble β-glucan fractions. Soluble arabinoxylans are degraded by exogenous xylanase to xylan oligosaccharides, which increase the butyrate produced in the ceca []. No such information exists on oat β-glucans. Most of the studies on oat feeding report positive results when appropriate exogenous enzyme supplementation is used, but the responses are dependent on species, inclusion rate and age [,,]. In our previous trial [], we demonstrated that the dehulled oat-based diets significantly increased the weight gain and resulted in lower FCR compared to the control diet without oats. The higher fibre content of whole oat diets did not compromise the production traits in comparison with the control diet. Dehulled oat treatment resulted in increased interleukin-1beta (IL-1β), whereas the whole oat decreased interleukin-8 (IL-8) concentration of the blood serum on day 37. It suggests that similarly to β-glucans of yeast and fungi, oat β-glucans can also be recognised by the Dectin-1 receptors of the immune cells. The exposure of β-(1,3) linkages after β-glucanase digestion can enhance this immune system stimulation [].

The aim of this study was to focus on the small intestine of chickens this time and to evaluate separately the structural (hulls) and soluble fibre (mainly soluble β-glucans) contents of the grain on the histomorphometry of jejunum and ileum parameters and on the viscosity of the jejunal content. As far as the authors know, no published results are available on how oats can modify the bacteriota in the ileal contents of broiler chickens.

2. Materials and Methods

The animal trial was carried out in 2020 at the experimental farm of the Institute of Physiology and Nutrition, at the Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences (Georgikon Campus, Keszthely, Hungary). The trial was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (Animal Welfare Committee, Georgikon Campus, Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences) with the number MÁB-1/2020.

2.1. Animal Experiment and Treatments

A total of 576 one-day-old Ross 308 broiler cockerels were purchased from a commercial hatchery (Gallus Ltd. Devecser, Hungary) and placed into 24 floor pens. The chickens were selected for similar body weight in the hatchery (43 ± 3 g) and arranged randomly into transfer boxes, marked with treatment and replicate signs. Randomised block design was used for the assignment of the pens. The one-day-old chickens were vaccinated against infectious bronchitis (CEVAC BRON), Newcastle disease (CEVAC VITAPEST) and infectious bursal disease (IBD) (CEVAC TRANSMUNE) in the hatchery. Chopped wheat straw was used as litter material. The net surface of pens was 1.7 m2. The bird number per pen was 24, which meant 14 chickens per m2 stocking density. The climatic conditions and light programme were computer-controlled, identical for all pens, and based on the breeder’s guidelines (Aviagen Ross Broiler Management Handbook, 2018) []. The room temperature was set to 34 °C on day 0 and reduced gradually to 24 °C at 18 days of age. The light intensity was 30 lux in the first week and 10 lux thereafter, with a constant day length of 23 h from day 0 to day 7 and 20 h light and 4 h dark period thereafter. Three phases of fattening were used. The starter diets (0–10 days) were fed in mash, and the grower (11–24 days) and finisher feeds (25–39 days) in pelleted form. Aside from a maize–soybean-based control diet (C), the two other treatments contained whole oats (WO) or dehulled oats (DO) in the starter (10%), grower (10%) and finisher (20%) phases. Feed and water were available ad libitum. Diets were formulated to be isoenergetic and isonitrogenous, and their nutrient content met the breeder’s recommendations (Nutrition specifications of Ross 308 broiler chickens, 2019) []. The nutrient content of WO and DO and the composition of the experimental diets are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. The measured nutrient content of the diets is presented in Table 3.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of whole oats and dehulled oats (%).

Table 2.

Composition of experimental diets (g/kg).

Table 3.

The measured nutrient contents of the experimental diets (%).

The main difference between the two oats was that WO contained more structural fibre and less protein and fat than DO (Table 1). On the other hand, DO contained more β-glucan, both the soluble and insoluble fractions.

Oats have been incorporated into diets at the expense of corn, and its lower energy content was compensated with increased ratio of sunflower oil (Table 2). Therefore, the WO- and DO-containing diets had not only increased fibre, but also had higher crude fat content than the control. On the other hand, the WO and DO diets had less starch. The highest soluble precipitable dietary fibre content was in the DO diets. The crude protein content of the diets was higher than the calculated values. The measured amino acid contents were, in all cases, close to the predicted values and above the requirements of the chickens (Table 3).

2.2. Sampling

On day 39, 1 chicken per pen (8 replicates/treatment), with live weight close to the average, were selected, euthanised by CO2 and slaughtered. The abdominal cavity of birds was opened immediately after slaughtering, and ileal and jejunal gut samples were collected for histology analysis. The jejunal samples were taken from 5 cm away from the Meckel’s diverticulum, while the ileal sample from 10 cm before the ileocecal junction. The tissue samples were fixed and stored in 5% phosphate-buffered formalin. In addition, about 2 g digesta was collected from the jejunum, about 10 cm before the Meckel’s diverticulum for viscosity measurement. The gut content was frozen immediately and stored −20 °C. Ileal chymus content samples were also collected with sterile cell spreaders from the middle part of ileum and put into sterile containers. It was immediately snap-frozen and stored at −80 °C until the evaluation of the bacteriota composition by next-generation sequencing.

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. Feed Analyses

The nutrient content of the diets and the two oat samples was determined with the official analytical methods. The insoluble dietary fibre (IDF) and soluble dietary fibre precipitable (SDFP) were measured with a Megazyme kit, according to the AOAC Official Method (AOAC Method 991.43, 1995). The total and soluble β-glucans were measured also by Megazyme kits according to the McCleary method (AOAC Method 995.16, 2005).

2.3.2. Mortality of Birds

To assist in the evaluation of histomorphological results, the mortality of animals was registered daily and evaluated for each feeding phase.

2.3.3. Histomorphological Analysis

Processing consisted of serial dehydration, clearing, paraffin liquid tissue stabilisation and wax impregnation. After forming the wax block of samples, tissue sections were cut in 5 µm thicknesses (2 cross-sections) from each of the 8 replicate pens per treatment. The sections were cut by a Microm HM 360 rotary microtome (Microm International GmbH, Robert-Bosch str. 49. Walldorf, Germany) and fixed on slides. A routine staining procedure was carried out with haematoxylin and eosin. The completed slides were examined under a Olympus BX43 Microscope fitted with an Olympus DP26 digital video camera (Olympus Corporation, Tokio, Japan) at 20× (40 × 0.5) magnifications. Images were analysed with ImageJ software (version 1.47) developed by the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA). A total of 10 intact, well-oriented villus–crypt units were selected in duplicate from each intestinal cross-section. The villus height from the apical end of the villus to the lamina muscularis mucosae and the crypt depth from the onset of crypt to the lamina muscularis mucosae were measured; furthermore, the muscular layer thickness was also measured. For each section, the ratio of villus height to crypt depth (VH/CD) was then determined, based on 10 well-oriented villi.

2.3.4. Viscosity Measurements

After thawing, the digesta samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 G. Using 0.5 mL supernatant, the viscosity was measured using a Brookfield DV II+ viscometer (Brookfield Engineering Laboratories, Stoughton, MA, USA) at 25 °C with a CP40 cone and shear rate of 60–600 s−1. Viscosity measurements were expressed in centipoise (cPs) unit (1 cPs = 1/100 dyne sec/cm2 = 1 mPa.s) prior to statistical analysis.

2.3.5. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification of the 16S rRNA Genes and Illumina MiSeq Sequencing

The method of DNA extraction, 16S rRNA gene amplification and Illumina MiSeq Sequencing were implemented based on the description of Such et al. [].

2.3.6. Bioinformatic Analysis

The microbiome analysis was performed using the Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology 2 (QIIME2—version 2020.2) software []. Sequences were filtered based on quality scores and the presence of ambiguous base calls using the quality-filter q-score options (QIIME2 default setting). Representative sequences were prepared using a 16S reference as a positive filter, as implemented in the Deblur denoise-16S method []. The sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) using the VSEARCH centroid-based algorithm. The SILVA database release (ver. 132) was used as a reference for taxonomic assignment at a similarity level of 97% []. Alpha and beta diversity were estimated using the QIIME2 diversity plugin and MicrobiomeAnalyst 2.0 (https://www.microbiomeanalyst.ca/, accessed on 1 August 2024) online software after the data were rarefied to 10,000 sequences/sample []. Raw sequence data of 16S rRNA metagenomics analysis were deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive under the BioProject identifier PRJNA1168431.

2.3.7. Statistical Analyses

The histomorphology and viscosity results were analysed with one-way ANOVA using the SPSS 29.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Welch test was used when the homogeneity condition of data was not met. Differences were considered significant at a level of p < 0.05, and as trends in the interval of 0.1 > p ≥ 0.05. In the case of mortality, chi-square tests were used for the evaluation of the results.

The microbiota analysis was performed with MicrobiomeAnalyst web-based tools filtered for low abundance sequences (<0) based on the mean abundance of OTUs, and for low variability (<10%) using interquartile range assessment. After being filtered, OTU abundances were not rarefied and transformed. Rarefaction was applied before the examination within-sample diversity. Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson α-diversity indices were calculated. To investigate differences in the structure of microbial communities, the principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was performed, based on the β-diversity index using PERMANOVA (permutational analysis of variance), based on the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrix and Unweighted Unifrac Distance. To verify the differences between bacterial communities, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used, with a Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate-adjusted p-value less than 0.05 considered as statistically significant. The FDR correction was applied on taxonomic levels. Abundances of microbial taxa were expressed as percentages of total 16S rRNA gene sequences.

3. Results

3.1. Histomorphometry

The histomorphometry analysis of the jejunum and ileum revealed that the WO and DO supplementation of diets altered the architecture of the small intestine, but the change was more pronounced in the ileum (Table 4). Neither WO nor DO feeding affected the jejunal villus height and crypt depth, but both oat treatments significantly increased the thickness of jejunal lamina propria. The WO diet resulted in increased ileal villus height (p = 0.000), whereas DO supplementation had negative effects on this parameter. Furthermore, both treatments significantly decreased the crypt depth in the ileum (p = 0.013). Similarly to the jejunum in tendency, both oat forms increased (p = 0.069) thickness of the ileal lamina propria in the ileum. Furthermore, WO increased not only the villus height, but also the villus height to crypt depth ratio (p = 0.000).

Table 4.

Histomorphometry indices of jejunum and ileum (%).

3.2. Mortality

The mortality of animals was 3.6, 5.7 and 4.7% in the C, WO and DO groups, respectively. None of the treatments resulted in differences in the mortality values (p = 0.627).

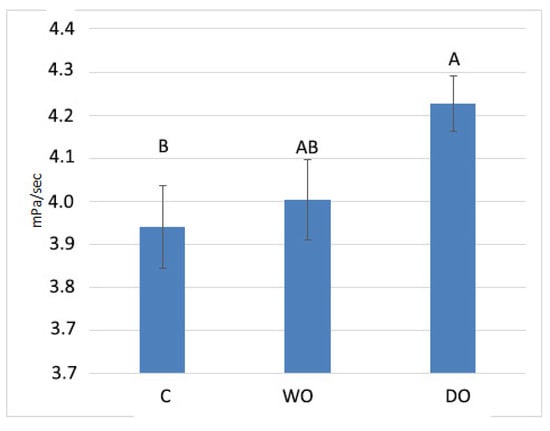

3.3. Viscosity

The effects of dietary treatments on the jejunal viscosity values are presented in Figure 1. The analysis of variance showed a trend in jejunal viscosity (p = 0.073). The DO treatment increased this parameter in comparison with the control.

Figure 1.

The effect of treatments on the viscosity of the jejunal gut content. C—control; WO—whole oat-based diet; DO—dehulled oat-based diet. The data were compared using one-way ANOVA, using the treatments as the main factors. A,B the averages with different letter marks show tendencies (p = 0.073).

3.4. Microbiota Analysis

In this study, a total of 470,603 high-quality 16S rRNA reads from all 36 samples were available for analysis after quality screening. The average sequence number in the ileal content was 13,072 (min: 7672; max: 18,287). These sequences were assigned to 559 OTUs with 97% similarity using the open approach. Similar species richness for the three dietary treatment groups has been found. The Chao1, Shannon and Simpson diversity indices of the bacteriota in the ileal contents did not demonstrate differences in the alpha diversity at day 39 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Alpha diversity indices of the ileum chymus of broiler chickens on day 39.

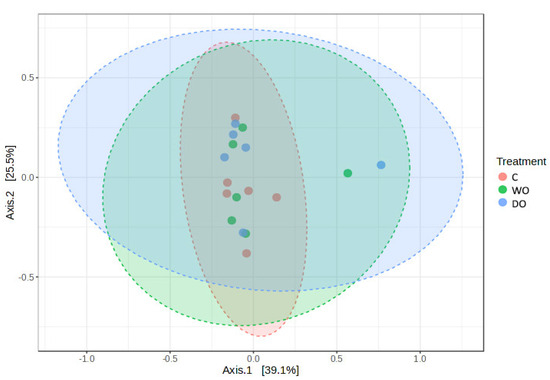

Beta diversity based on principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) ordination using the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrix (PERMANOVA R-squared = 0.097 p = 0.649) did not show a significantly different bacterial community structure between the treatments (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrix on treatments; p = 0.649. To verify the significance of the bacterial community, permutational analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was performed.

In the ileal content, Firmicutes was the main dominant phylum, accounting for about 95.6–96.7% of the total detected phyla (Table 6) followed by Actinobacteria (2.4–3.7%), Cyanobacteria (0.02–0.1%), Proteobacteria (0.02–0.6%) and Bacteroidetes (0.0–0.05%). The dietary treatments did not cause significant differences (p ≥ 0.05).

Table 6.

Effects of dietary treatments on the relative abundances (%) of bacterial phyla in the ileum (at day 39 of life).

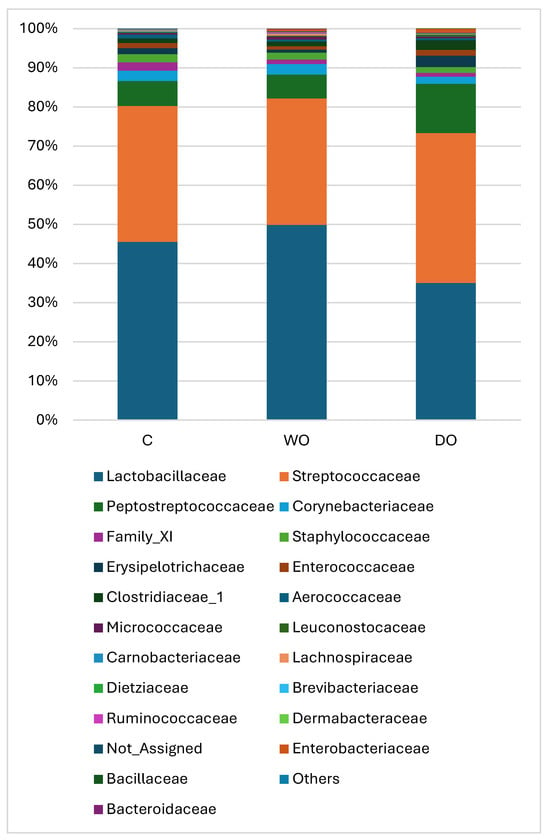

The treatments also failed to result in significant differences at class, order or family level. Figure 3 presents the ratio of the main families; among them, the dominant were the Lactobacillaceae (35.0–49.9%), Streptococcaceae (32.3–38.3%) and Peptostreptococcceae (6.0–12.5%). Although DO decreased the abundance of Lactobacillaceae and increased the ratio of Peptostreptococcceae in comparison with the two other treatments, these differences were not significant.

Figure 3.

Effects of dietary treatments on the relative abundances of bacterial families. C—control; WO—whole oat-based diet; DO—dehulled oat-based diet. The data were compared using one-way ANOVA, using the treatments as the main factors.

At genus level, the samples consisted of 48 genera, of which 10 had a relative abundance more than 1% (Table 7). These 10 genera represented the 90.5% of the total bacterial population in the control group, and 90.8 and 86.9% in the oat- and dehulled oat-supplemented groups. The lactic acid-producing Lactobacillus and Streptococcus genera were found most abundant in all groups, and their proportion did not change among the treatments. Whereas the Lactococcus genus was almost missing in the whole oat- and dehulled oat-supplemented groups, its abundance was in tendency higher in the C group (p = 0.052). No significant differences were found between the ratio of the other genera (p ≥ 0.05).

Table 7.

Relative abundances (%) of bacterial genera (>0.1%) in the ileal contents of broiler chickens (at day 39 of life).

4. Discussion

The fibrous feed ingredients have several physicochemical properties including solubility, water-holding capacity (WHC), viscosity, fermentability, and ability to bind bile acids []. On the other hand, insoluble dietary fibre sources, such as oat hulls, are known for their positive effects on the gizzard function and mucosal structure of the small intestine [,], which might improve nutrient digestibility [].

In this trial, whole oats and dehulled oats resulted in no significant differences in the morphology of the jejunum. Adewole et al. [] obtained comparable results to ours. In their experiment, 3% oat hulls were fed with 36-day-old broiler chickens and found no effect on jejunal villus height and crypt depth. Similarly, Torki et al. [] and Jimenez-Moreno et al. [] did not detect any effect of oat hulls (5% and 2.5 and 5.0%) inclusion on the jejunal villus height of broilers. In their opinion, it seems that the negative effect of dietary fibre on intestinal villus height reported in previous studies is more related to an increase in digesta viscosity, which is usually associated with soluble fibre. In addition, Tejada et al. [] reported that not just the fibre type, but also the inclusion levels and the particle size of the fibre are key factors in the regulation of intestinal morphology, viscosity, nutrient transporters, and growth performance. According to their results, the shortest jejunal villus height was observed in the group fed 8% crude fibre from cellulose with a fine particle size (p < 0.001), and the ileal villus was highest in the groups fed the high cellulose levels regardless of the particle size (p < 0.001). This may be another explanation for why oats did not significantly affect jejunal morphology. The only morphological parameter that changed significantly in the jejunum was the lamina propria, which was thicker in both WO- and DO-supplemented diets than in the control group. It is well known that dietary fibre activates intestinal peristalsis [] and increase the muscle thickness in the small intestine [].

In this study, DO decreased, while WO increased, the ileal villus height, and both form of oats decreased crypt depth, in comparison with the control group. In tendency, the thickness of lamia propria increased in this gut segment for both oat-containing diets. These changes are related either to the modified life span of the enterocytes or to a compromised enterocyte renewal []. It has been reported that the insoluble NSP can have beneficial effects in the gastrointestinal tract, such as increasing the weight and size of the gizzard, pancreas, liver, as well as increasing the intestinal villus height and subsequently the absorption surface area [,]. These properties of the gut morphology can encourage nutrient digestion and absorption [,]. In the current study, positive change in ileal histomorphology resulted only with the WO-containing diets.

Amer et al. [] fed 1,3-beta glucan (150 mg kg−1)-supplemented diets with broiler chickens and found that β-glucan could improve the development and integrity of the intestine without compromising the growth rate of birds. Interestingly, our dehulled oat treatment failed to result in such improvements, in spite of the total β-glucan content of DO being 43g/kg, which resulted in diet level of 4.3–8.6 g/kg β-glucan. Furthermore, the dehulled oat at 10 and 20% inclusion significantly improved the performance parameters of broiler chickens []. These results confirm the conclusions of some previous works that oats can be used in broiler chicken nutrition efficiently [,,], without compromising the weight gain.

In our experiment, neither form of oats significantly affected the viscosity of jejunal contents, but the DO treatment tended to increase this parameter. Soluble β-glucans of oats can be beneficial until certain levels, and there are suggestions to formulate broiler diets for minimum soluble fibre contents, which can optimise gut health and caecal bacterial fermentation [,]. In this trial, exogenous β-glucanase was used to overcome the potential viscosity-increasing effect of soluble β-glucans. The enzymatic breakdown of β-glucans is quicker than that of arabinoxylans and the products are small oligosaccharides with different molecular weights, which can be readily used by the microbiota in the ileum [,]. The improvement of gut health and the positive changes in the fermentation patterns could also improve the performance parameters [].

The type of fibre determines which type of bacteria dominates the gut []. In the current experiment, dietary treatments did not generate differences in the bacterial diversity in the ileum. Similarly, in our previous research [], neither form of oats affected the diversity values in the small intestine. In that trial, clear differences could be found between the control and 20% oat-supplemented group only in the bacterial composition of the jejunum mucosa.

Although the difference was not significant, in both oat diets, Proteobacteria phylum was present, which was missing in the control animals. Several studies have reported that higher levels of Proteobacteria in the small intestine are associated with poorer performance in chickens []. In our previous study, we found that the proportion of Lactobacilli was inversely related to the abundance of Proteobacteria, including the Enterobacteriaceae family. The reason for changes in the Proteobacteria ratio could be the more intensive epithelial abrasion in the oat treatment groups. This increases the nitrogen content of the gut and plays a role as a substrate of Proteobacteria. The higher intestinal epithelial wear was also found in our previously published results, when isobutyric and isovaleric acids increased significantly in the caeca, when oat-containing diets were fed []. It was concluded that the substrates to produce iso-butyric and iso-valeric acids are mainly the increase in the intestinal sloughed cells, and valine and leucine are the main precursors of these two branched chain fatty acids [].

In the current study, only the Lactococcus genus showed decreased tendency as a result of oat treatments in the ileum. This genus is a member of the family Streptococcacaeae and contain lactic acid bacteria. They are considered as beneficial due to their probiotic properties. The members of Lactococcus genus are known as homofermentative bacteria and ferment hexoses almost exclusively (>85%) to lactic acid via the Embden–Meyerhof–Parnas pathway (EMP) or glycolysis [,,]. We obtained similar results in our previous research, when feeding whole oat at 10 and 20% proportions significantly reduced the abundance of the Lactococcus and Streptococcus genera in the caeca []. Further research is needed to understand the mechanism behind these changes.

5. Conclusions

Feeding oats affected the gut morphology in the jejunum and ileum in a different way. In the jejunum, only the muscular layer of the gut increased after oat feeding, but in the ileum, whole oats caused positive changes such as increase in villus height and decrease in crypt depth. This result suggests that fibrous feedstuffs are probably ground in the gizzard to such fine particles that they do not cause epithelial erosion and lead to more intensive renewal of villi. From a practical point of view, our viscosity results suggest that even after using exogenous beta-glucanase, DO could increase the viscosity of the jejunal content, which could be the potential limit of its incorporation. Oats do not modify the microbiota diversities and the ratio of the main bacterial groups. In conclusion, feeding WO and DO at 10–20% inclusion rates causes only minor changes in the small intestine of broiler chickens.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.D.; methodology, K.D. and N.S.; formal analysis, N.S.; investigation, K.D., M.A.R., L.P., V.F., T.C., K.G.T. and B.K.; resources, K.D.; data curation, V.F. and N.S.; writing—original draft preparation, N.S.; writing—review and editing, K.D.; visualization, N.S.; supervision, K.D.; project administration, K.D.; funding acquisition, K.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Flagship Research Groups Programme of the Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal experiment was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (Animal Welfare Committee, Georgikon Campus, Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences) under the license number MÁB—1/2020 (approved in 2020).

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. Raw sequence data of 16S rRNA meta-genomics analysis are deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Se-quence Read Archive under the BioProject identifier PRJNA1168431.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Research Excellence Program of the Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAOSTAT. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/es/ (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Hakala, K.; Jauhiainen, L.; Rajala, A.A.; Jalli, M.; Kujala, M.; Laine, A. Different Responses to Weather Events May Change the Cultivation Balance of Spring Barley and Oats in the Future. Field Crops Res. 2020, 259, 107956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, A.; Ramzan, F.; Ramzan, Y.; Zulfiqar, F.; Ahsan, M.; Lim, K.B. Molecular Markers Improve Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Crops: A Review. Plants 2020, 9, 1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterna, V.; Zute, S.; Brunava, L. Oat Grain Composition and Its Nutrition Benefice. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2016, 8, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svihus, B. The Gizzard: Function, Influence of Diet Structure and Effects on Nutrient Availability. Worlds Poult. Sci. J. 2011, 67, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frølich, W.; Nyman, M. Minerals, Phytate and Dietary Fibre in Different Fractions of Oat-Grain. J. Cereal Sci. 1988, 7, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; De, S.; Belkheir, A. Avena Sativa (Oat), A Potential Neutraceutical and Therapeutic Agent: An Overview. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 126–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampshire, J. Variation in the Content of Nutrients in Oats and Its Relevance for the Production of Cereal Products. In Proceedings 7th International Oat Conference; Peltonen-Sainio, P., Topi-Hulmi, M., Eds.; MTT Agrifood Research Finland: Jokioinen, Finland, 2004; pp. 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Rakha, A.; Saulnier, L.; Åman, P.; Andersson, R. Enzymatic Fingerprinting of Arabinoxylan and β-Glucan in Triticale, Barley and Tritordeum Grains. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 90, 1226–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tömösközi, S.; Jaksics, E.; Bugyi, Z.; Németh, R.; Schall, E.; Langó, B.; Rakszegi, M. Screening and Use of Nutritional and Health-Related Benefits of the Minor Crops. In Developing Sustainable and Health Promoting Cereals and Pseudocereals; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 57–85. [Google Scholar]

- Sinkovič, L.; Pipan, B.; Neji, M.; Rakszegi, M.; Meglič, V. Influence of Hulling, Cleaning and Brushing/Polishing of (Pseudo)Cereal Grains on Compositional Characteristics. Foods 2023, 12, 2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, R.; Turóczi, F.; Csernus, D.; Solymos, F.; Jaksics, E.; Tömösközi, S. Characterization of Chemical Composition and Techno-functional Properties of Oat Cultivars. Cereal Chem. 2021, 98, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetland, H.; Svihus, B. Effect of Oat Hulls on Performance, Gut Capacity and Feed Passage Time in Broiler Chickens. Br. Poult. Sci. 2001, 42, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacranie, A.; Adiya, X.; Mydland, L.T.; Svihus, B. Effect of Intermittent Feeding and Oat Hulls to Improve Phytase Efficacy and Digestive Function in Broiler Chickens. Br. Poult. Sci. 2017, 58, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Burton, E.; Scholey, D.; Alkhtib, A.; Broadberry, S. Efficacy of Oat Hulls Varying in Particle Size in Mitigating Performance Deterioration in Broilers Fed Low-Density Crude Protein Diets. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 102979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itani, K.; Apajalahti, J.; Smith, A.; Ghimire, S.; Svihus, B. The Effect of Increasing the Level of Oat Hulls, Extent of Grinding and Their Interaction on the Performance, Gizzard Characteristics and Gut Health of Broiler Chickens Fed Oat-Based Pelleted Diets. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2024, 308, 115858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford, M.R. The Evolution and Application of Enzymes in the Animal Feed Industry: The Role of Data Interpretation. Br. Poult. Sci. 2018, 59, 486–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Immerseel, F.; Vermeulen, K.; Ornust, L.; Eckhaut, V.; Ducatelle, R. Nutritional Modulation of Microbial Signals in the Distal Intestinal and How They Can Affect Broiler Health. In Proceedings of the 21st European Symposium on Poultry Nutrition, Salou/Vila-Seca, Spain, 8–11 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Scholey, D.V.; Marshall, A.; Cowan, A.A. Evaluation of Oats with Varying Hull Inclusion in Broiler Diets up to 35 Days. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 2566–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svihus, B.; Gullord, M. Effect of Chemical Content and Physical Characteristics on Nutritional Value of Wheat, Barley and Oats for Poultry. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2002, 102, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Józefiak, D.; Rutkowski, A.; Jensen, B.B.; Engberg, R.M. The Effect of SS-Glucanase Supplementation of Barley- and Oat-Based Diets on Growth Performance and Fermentation in Broiler Chicken Gastrointestinal Tract. Br. Poult. Sci. 2006, 47, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Such, N.; Rawash, M.A.; Farkas, V.; Poór, J.; Tewelde, K.G.; Pál, L.; Csitári, G.; Wágner, L.; Farkas, E.P.; Dublecz, K. Research Note: Complex Evaluation of Whole Oats and Dehulled Oats as Feedstuffs for Broiler Chickens. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 105207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J.P.; Pescatore, A.J. Barley β-Glucan in Poultry Diets. Ann. Transl. Med. 2014, 2, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Aviagen. Roos Broiler Management Handbook; Aviagen: Huntsville, AL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Aviagen. Ross Nutrition Specifications; Aviagen: Huntsville, AL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Such, N.; Schermann, K.; Pál, L.; Menyhárt, L.; Farkas, V.; Csitári, G.; Kiss, B.; Tewelde, K.G.; Dublecz, K. The Hatching Time of Broiler Chickens Modifies Not Only the Production Traits but Also the Early Bacteriota Development of the Ceca. Animals 2023, 13, 2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estaki, M.; Jiang, L.; Bokulich, N.A.; McDonald, D.; González, A.; Kosciolek, T.; Martino, C.; Zhu, Q.; Birmingham, A.; Vázquez-Baeza, Y.; et al. QIIME 2 Enables Comprehensive End-to-End Analysis of Diverse Microbiome Data and Comparative Studies with Publicly Available Data. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2020, 70, e100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, A.; McDonald, D.; Navas-Molina, J.A.; Kopylova, E.; Morton, J.T.; Zech Xu, Z.; Kightley, E.P.; Thompson, L.R.; Hyde, E.R.; Gonzalez, A.; et al. Deblur Rapidly Resolves Single-Nucleotide Community Sequence Patterns. mSystems 2017, 2, e00191-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA Ribosomal RNA Gene Database Project: Improved Data Processing and Web-Based Tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, J.; Liu, P.; Zhou, G.; Xia, J. Using MicrobiomeAnalyst for Comprehensive Statistical, Functional, and Meta-Analysis of Microbiome Data. Nat. Protoc. 2020, 15, 799–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Moreno, E.; Frikha, M.; de Coca-Sinova, A.; García, J.; Mateos, G.G. Oat Hulls and Sugar Beet Pulp in Diets for Broilers 1. Effects on Growth Performance and Nutrient Digestibility. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2013, 182, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Alvarado, J.M.; Jiménez-Moreno, E.; Valencia, D.G.; Lázaro, R.; Mateos, G.G. Effects of Fiber Source and Heat Processing of the Cereal on the Development and PH of the Gastrointestinal Tract of Broilers Fed Diets Based on Corn or Rice. Poult. Sci. 2008, 87, 1779–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacranie, A.; Svihus, B.; Denstadli, V.; Moen, B.; Iji, P.A.; Choct, M. The Effect of Insoluble Fiber and Intermittent Feeding on Gizzard Development, Gut Motility, and Performance of Broiler Chickens. Poult. Sci. 2012, 91, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetland, H.; Choct, M.; Svihus, B. Role of Insoluble Non-Starch Polysaccharides in Poultry Nutrition. Worlds Poult. Sci. J. 2004, 60, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewole, D.; MacIsaac, J.; Fraser, G.; Rathgeber, B. Effect of Oat Hulls Incorporated in the Diet or Fed as Free Choice on Growth Performance, Carcass Yield, Gut Morphology and Digesta Short Chain Fatty Acids of Broiler Chickens. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torki, M.; Schokker, D.; Duijster-Lensing, M.; Van Krimpen, M.M. Effect of Nutritional Interventions with Quercetin, Oat Hulls, β-Glucans, Lysozyme and Fish Oil on Performance and Health Status Related Parameters of Broilers Chickens. Br. Poult. Sci. 2018, 59, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Moreno, E.; González-Alvarado, J.M.; de Coca-Sinova, A.; Lázaro, R.P.; Cámara, L.; Mateos, G.G. Insoluble Fiber Sources in Mash or Pellets Diets for Young Broilers. 2. Effects on Gastrointestinal Tract Development and Nutrient Digestibility. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 2531–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejeda, O.J.; Kim, W.K. Effects of Fiber Type, Particle Size, and Inclusion Level on the Growth Performance, Digestive Organ Growth, Intestinal Morphology, Intestinal Viscosity, and Gene Expression of Broilers. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esonu, B.O.; Azubuike, J.C.; Emenalom, O.O.; Etuk, E.B.; Okoli, I.C.; Ukwu, H.; Nneji, C.S. Effect of Enzyme Supplementation on the Performance of Broiler Finisher Fed Microdesmis Puberula Leaf Meal. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2004, 3, 112–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Peebles, E.D.; Morgan, T.W.; Harkess, R.L.; Zhai, W. Protein Source and Nutrient Density in the Diets of Male Broilers from 8 to 21 d of Age: Effects on Small Intestine Morphology. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, W.A.; Ruhnau, D.; Gavrău, A.; Dublecz, K.; Hess, M. Comparing Effects of Natural Betaine and Betaine Hydrochloride on Gut Physiology in Broiler Chickens. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 102173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praes, M.; Pereira, A.; Sgavioli, S.; Duarte, K.; Alva, J.; Domingues, C. de F.; Puzzoti, M.; Junqueira, O. Small Intestine Development of Laying Hens Fed Different Fiber Sources Diets and Crude Protein Levels. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Avic. 2011, 13, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchewka, J.; Sztandarski, P.; Zdanowska-Sąsiadek, Ż.; Adamek-Urbańska, D.; Damaziak, K.; Wojciechowski, F.; Riber, A.B.; Gunnarsson, S. Gastrointestinal Tract Morphometrics and Content of Commercial and Indigenous Chicken Breeds with Differing Ranging Profiles. Animals 2021, 11, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amer, S.A.; Beheiry, R.R.; Abdel Fattah, D.M.; Roushdy, E.M.; Hassan, F.A.M.; Ismail, T.A.; Zaitoun, N.M.A.; Abo-Elmaaty, A.M.A.; Metwally, A.E. Effects of Different Feeding Regimens with Protease Supplementation on Growth, Amino Acid Digestibility, Economic Efficiency, Blood Biochemical Parameters, and Intestinal Histology in Broiler Chickens. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.A.d.; Pessotti, B.M. de S.; Zanini, S.F.; Colnago, G.L.; Rodrigues, M.R.A.; Nunes, L. de C.; Zanini, M.S.; Martins, I.V.F. Intestinal Mucosa Structure of Broiler Chickens Infected Experimentally with Eimeria Tenella and Treated with Essential Oil of Oregano. Ciência Rural. 2009, 39, 1471–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, S.A.; Attia, G.A.; Aljahmany, A.A.; Mohamed, A.K.; Ali, A.A.; Gouda, A.; Alagmy, G.N.; Megahed, H.M.; Saber, T.; Farahat, M. Effect of 1,3-Beta Glucans Dietary Addition on the Growth, Intestinal Histology, Blood Biochemical Parameters, Immune Response, and Immune Expression of CD3 and CD20 in Broiler Chickens. Animals 2022, 12, 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Bedford, M.R.; Wu, S.-B.; Morgan, N.K. Soluble Non-Starch Polysaccharide Modulates Broiler Gastrointestinal Tract Environment. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Mandal, R.K.; Bedford, M.R.; Jha, R. Xylanase Improves Growth Performance, Enhances Cecal Short-Chain Fatty Acids Production, and Increases the Relative Abundance of Fiber Fermenting Cecal Microbiota in Broilers. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2021, 277, 114956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford, M.R. Mechanism of Action and Potential Environmental Benefits from the Use of Feed Enzymes. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1995, 53, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahasrabudhe, N.M.; Tian, L.; van den Berg, M.; Bruggeman, G.; Bruininx, E.; Schols, H.A.; Faas, M.M.; de Vos, P. Endo-Glucanase Digestion of Oat β-Glucan Enhances Dectin-1 Activation in Human Dendritic Cells. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 21, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford, M.R.; Svihus, B.; Cowieson, A.J. Dietary Fibre Effects and the Interplay with Exogenous Carbohydrases in Poultry Nutrition. Anim. Nutr. 2024, 16, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejeda, J.O.; Kim, K.W. Role of Dietary Fiber in Poultry Nutrition. Animals 2021, 11, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawash, M.A.; Farkas, V.; Such, N.; Mezőlaki, Á.; Menyhárt, L.; Pál, L.; Csitári, G.; Dublecz, K. Effects of Barley- and Oat-Based Diets on Some Gut Parameters and Microbiota Composition of the Small Intestine and Ceca of Broiler Chicken. Agriculture 2023, 13, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollarcikova, M.; Kubasova, T.; Karasova, D.; Crhanova, M.; Cejkova, D.; Sisak, F.; Rychlik, I. Use of 16S RRNA Gene Sequencing for Prediction of New Opportunistic Pathogens in Chicken Ileal and Cecal Microbiota. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 2347–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, M.E.; Collinder, E.; Stern, S.; Tjellström, B.; Norin, E.; Midtvedt, T. Correlation between Faecal Iso-Butyric and Iso-Valeric Acids in Different Species. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2005, 17, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot, A.; Gitton, C.; Anglade, P.; Mistou, M. Proteomic Analysis of Lactococcus lactis, a Lactic Acid Bacterium. Proteomics 2003, 3, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvetti, E.; Torriani, S.; Felis, G.E. The Genus Lactobacillus: A Taxonomic Update. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2012, 4, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onyeaka, H.N.; Nwabor, O.F. Lactic Acid Bacteria and Bacteriocins as Biopreservatives. In Food Preservation and Safety of Natural Products; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 147–162. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).