Abstract

The nutritional potential of Opuntia forage is limited by its low crude protein (CP) content. Urea supplementation enhances low-quality forages, but its application in Opuntia silage and its influence on ruminal degradability are limited. This study evaluated the effects of urea addition (0, 20, 40, 60, or 80 g/kg of dry matter (DM)) and ensiling duration (0, 4, 8, 16, 24, or 28 d) on the silage pH and in situ DM degradability of four Opuntia species. Silage pH was influenced by both species and urea level, with greater values observed in silages treated with urea at 80 g/kg DM. The effective degradability of DM (EDDM) was influenced by Opuntia species and was reduced at the highest urea level. In contrast, the ensiling period beyond 12 d did not affect EDDM, and pH stabilized for all treatments after this point. Urea supplementation increases CP content and modifies silage pH but does not improve ruminal degradability. It is recommended that the addition of urea in Opuntia silages should not exceed 60 g/kg DM to avoid reduced fermentative quality. A study limitation is the absence of fermentation end-product data, which would offer a more complete quality assessment.

1. Introduction

Drylands (including semi-arid, arid, and dry subhumid zones) occupy approximately 41% of the Earth’s land area and support more than 2 billion people (UNCCD, 2024) [1]. The arid and semiarid regions are mainly used as rangelands and are characterized by scarcity of rainfall and soils susceptible to erosion [2,3]. Cactus is widely recognized as a valuable source of fodder and water for livestock production in semiarid regions [4,5,6]. Beyond its role as a feed source, cactus supplementation acts as a strategic hydrating fodder, significantly reducing voluntary water intake while maintaining nutrient digestibility, offering a crucial adaptation for sustainable livestock production in water-scarce, semiarid regions [7,8].

Plants of the genus Opuntia present a viable option for reforestation in arid and semiarid rangelands due to their resistance to livestock grazing and harsh environmental conditions [9]. Many species of Opuntia are suitable for use as forage plants and have the potential to enhance livestock productivity in arid environments [10]. Opuntia ficus-indica (OFI) is an important alternative forage in arid and semiarid regions due to its rapid growth, ease of harvesting, and spineless nature. However, it is also susceptible to pests, frost, and grazing, and is therefore successfully used as a fodder bank but not as a reforestation species [11]. In contrast, some wild species, such as O. leucotrichia (OL), O. robusta (OR), and O. streptacantha (OS), have lower growth potential; however, they are more resilient to cold, drought, and diseases compared to OFI. Moreover, these species are part of the native vegetation found in the rangelands of north-central Mexico [12].

Despite their potential as a forage resource in semi-arid regions, the use of Opuntia species is constrained not only by their low crude protein content, which limits rumen microbial activity during the dry season, but also by their high mineral (ash) levels and distinctive fiber characteristics that affect overall feeding value [10,13,14]. Supplementation with non-protein nitrogen (NPN), particularly urea, has been widely applied to improve the nutritive value of low-quality forages [15,16,17,18,19,20]. The ruminal microbiota converts NPN into ammoniacal nitrogen (NH3-N), which supports microbial protein synthesis and enhances fermentation efficiency. However, excessive NPN intake can disrupt microbial balance, reduce fermentation efficiency, and lead to toxicity and nitrogen losses to the environment [21].

Although the benefits of urea supplementation are well documented for grasses and crop residues [16,22], information regarding its effects on cactus silages remains scarce. Previous studies have examined a single Opuntia species or have not fully examined the interaction between urea addition, ensiling duration, and ruminal degradability [23]. This represents a significant knowledge gap, as the ensiling process may modulate nitrogen availability and fermentation dynamics in ways that are unique to cactus forages.

Therefore, this study aimed to (i) compare the fermentation characteristics and nutritive value of four Opuntia species ensiled with increasing urea levels, and (ii) assess the in situ ruminal degradability kinetics. We hypothesized that urea supplementation would increase crude protein content without negatively affecting the inherent dry matter degradability of the silages.

2. Materials and Methods

The research protocol (protocol # 2022/11/10) received approval from the Animal Welfare Committee at the Unidad Académica de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia at the Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas (UAMVZ-UAZ). The handling and management of the animals strictly adhered to the Official Mexican Standard NOM-062-ZOO-1999, Humane care and welfare of experimental animals.

2.1. Collection Sites and Harvest Procedure

Data collection was conducted in September 2023. Opuntia species were obtained from three municipalities located in the same physiographic and agroclimatic area within the state of Zacatecas, Mexico: Enrique Estrada (22°58′37″ N, 102°43′20″ W), Vetagrande (22°49′10″ N, 102°34′36″ W), and Villa de Cos (23°32′43″ N, 102°15′7″ W). These sites were selected based on the simultaneous availability of all target Opuntia species and their proximity to the experimental area at the university facilities, which facilitated both transportation and processing of the specimens. The collection area is characterized by an elevation range of 1750 to 2400 m above sea level (masl), mean annual temperatures of 14 to 19 °C and annual rainfall between 375 and 430 mm [24].

Intermediate mature cladodes were selected visually by a combination of phenological stage, color, position, and structure (age > 150 d, cladodes with rigid structure and dark green color, located in the middle part of the plant [25,26]) and harvested from the four Opuntia species (OFI, OL, OS, and OR) used in this study, with a minimum of 50 plants sampled per species to ensure representative genetic diversity. Cladodes were manually detached at the junction with the plant using a sharp knife. All harvests were conducted between 06:00 and 08:00 h. Immediately following detachment, spines were removed by briefly passing a propane torch over the cladode surface to burn them off. The sampling yielded approximately 300 kg of cladode per species (1200 kg in total).

2.2. Opuntia Process and Silage

Prior to ensiling, proximate chemical composition was determined. Initial (pre-ensiling) pH of Opuntia cladodes was not recorded; however, all species were harvested at comparable maturity, chopped under identical conditions, and immediately packed to standardize pre-ensiling handling and minimize baseline variability. Since no significant effects of site (p > 0.05) or site × species interaction (p > 0.05) were detected, representative subsamples of comparable mass were randomly collected and homogenized to produce a composite sample. This procedure ensured the preparation of a uniform batch of plant material for the subsequent ensiling trial. The proximate chemical composition of cladodes from the four Opuntia species collected is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Proximate chemical composition (g/kg fresh matter) of cladodes from four Opuntia species collected (Day 0, prior to ensiling).

The cladodes were mechanically chopped into 1 to 3 cm3 pieces using a 13 hp helicoidal chopper (Swissmex, model 610610 Turbo Fresh, Lagos de Moreno, Jalisco, Mexico). For each species, the chopped material was divided into five 60 kg portions on fresh biomass basis. Before the urea mixing process, the DM content of the freshly chopped cladodes was determined by drying a representative sample at 105 °C for 24 h. The resulting DM values, which ranged from 10.44% to 11.6%, were used to calculate the required urea addition for the experimental treatments. Urea was applied as a dry powder.

A stainless-steel, 1 hp horizontal paddle mixer with a 100 kg capacity (Lenin Manufactures, San Luis Potosí, Mexico) was used to thoroughly mix each portion with urea at one of five inclusion levels: 0, 20, 40, 60, or 80 g per kg of dry matter. The mixtures were then ensiled in PVC micro-silages of 6.3 cm diameter × 50 cm length. The micro-silages consisted of PVC tubes with tight-fitting lids equipped with rubber O-rings and PVC sealing tape to ensure anaerobiosis. Each micro-silages had a capacity of 1.5 L and a wall thickness of 1.6 mm. A total of 21 micro-silages were prepared per treatment; each filled with 1000 g of the mixture and compacted manually to a density of 700 kg of fresh material per m3 (equivalent to 700 g/L), reaching approximately 1 kg per silo.

2.3. Treatments

The experiment used a factorial design (Opuntia species × urea levels × ensiling period) with repeated measurements (periods) evaluating four Opuntia species and five urea levels (20 treatments total). The silages were assessed at seven ensiling periods (0, 4, 8, 12, 16, 24, and 28 days). Each treatment-period combination was replicated three times, resulting in a total of 420 experimental units (20 treatments × 7 periods × 3 replicates).

2.4. Sampling and Sample Preparations

On days 0, 4, 8, 12, 16, 24, and 28, three micro-silages per treatment were destructively sampled. The pH of the silage was measured immediately after opening, at room temperature (approximately 20 °C), using a Hanna HI98161 pH meter equipped with a conical tip electrode for semi-solid samples (FC2023, Hanna Instruments, Woonsocket, RI, USA). The samples were then dried in a forced-air oven (Felisa FE-291A, Zapopan, Jalisco, Mexico) at 65 °C for 60 h. The dried samples were ground through a 2 mm screen in a Wiley mill (Thomas Scientific, Swedesboro, NJ, USA) and stored in sealed plastic bags for subsequent in situ digestibility and chemical composition analysis.

2.5. In Situ Digestibility Measurements

At 0, 4, 8, 12, 16, 24, and 28 d ensiling periods, the rate and extent of dry matter (DM) loss were determined using the nylon bag technique [27]. Twelve rumen-cannulated Rambouillet × Friesian rams (48 ± 5.5 kg) were used for the incubations. Nylon bags (5 × 10 cm; 53 μm pore size) were filled with 3 g of ground samples from the different treatments and placed in the rumen. Throughout the trial, the rams were fed a basal diet of alfalfa hay ad libitum. The average ruminal pH of the cannulated animals, measured just before the morning feeding during the trial period, was 6.4 ± 0.3, ensuring a stable rumen environment for the incubations.” Prior to the incubations, the cannulated rams were adapted to an alfalfa hay diet for 14 days. During the trial, they were fed twice daily at 08:00 and 16:00. Nylon bags containing the samples were inserted into the rumen immediately after the morning feeding. Each treatment sample (3 g DM) was incubated in duplicate bags per animal, and all treatments were randomly distributed across the 12 animals to account for animal variability. Blank bags (without sample) were also incubated and washed to correct for particle loss and microbial contamination.

Bags were retrieved at incubation times of 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h (time 0 samples were not incubated in the rumen). After removal, each bag was manually rinsed individually under running water at approximately 20 °C until the rinse water, collected by hand-squeezing into a transparent 100 mL glass cup, appeared clear and free of particles against a white background. Bags were then dried at 55 °C for 48 h. Chemical composition was analyzed on samples from day 0 and day 28 to characterize the initial and final state of the silages.

Dry matter disappearance at each incubation time was calculated by weight difference and expressed as a coefficient. Digestion kinetics were estimated using the equations proposed by Ørskov and McDonald (1979) [28]:

where:

- p = DM disappearance at time t

- a = soluble fraction. The DM solubilized at the beginning of incubation (time 0)

- b = potentially degradable fraction of DM, degraded slowly in the rumen

- c = degradation rate constant of fraction b

- t = incubation time

The EDDM was calculated according to the formula:

where:

- k = rumen outflow rate

- LT = lag time prior to microbial degradation

The nonlinear parameters a, b, c, and the EDDM were calculated assuming a passage rate of 0.03 h−1. Calculations were performed using the Neway computer program [27].

2.6. Chemical Composition Analyses

Chemical composition analyses were conducted from all silage treatments at 28 d of ensiling. Dry matter (DM; method 934.01), ash (method 942.05), ether extract (EE; method 920.39), and crude protein (CP; method 990.03) were determined according to AOAC procedures (AOAC, 2006). Neutral detergent fiber (NDF) and acid detergent fiber (ADF) concentrations were determined using an Ankom 200 fiber analyzer (Ankom Technology, Fairport, NY, USA) following the procedures of Van Soest [29], with sodium sulfite included in the NDF analysis.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using the SAS statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) via SAS® OnDemand for Academics (SAS Studio, Release 9.4). A Shapiro–Wilk test was conducted to test for data normality. Data were analyzed as a factorial design (Opuntia species × urea levels × ensiling period) with repeated measurements (periods) using the MIXED procedure of SAS [30]. The model included the fixed effects of species, urea level, ensiling period, and all their interactions. The random effect was the experimental unit (micro-silage). The covariance structure between the different sampling times (periods) was defined in the model as being compound symmetry after verification of Akaike and Schwarz-Bayesian criteria [28]. Comparisons were established by the PDIFF instruction. In addition, the urea level and ensiling period effects were analyzed using linear and quadratic contrasts. The contrasts were performed with the LSMEANS and ESTIMATE statements in SAS. In instances where quadratic polynomials exhibited significance, quadratic equations were computed utilizing the REG procedure. The effects were considered significant when p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Silage pH Dynamics During Ensiling

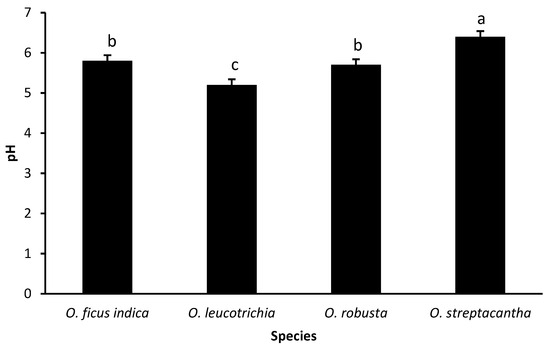

The pH of the Opuntia silage showed differences (p < 0.01). The highest value was observed in OS (6.4), which was significantly greater (p < 0.05) than that of OL (5.2). Silages OFI (5.8) and OR (5.7) displayed intermediate values that were not different (p > 0.05) from each other (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Main effect of specie on pH of Opuntia spp. ensiled with urea. Bars without a common letter (a, b, c) differ (p < 0.05). Error bars indicate standard error.

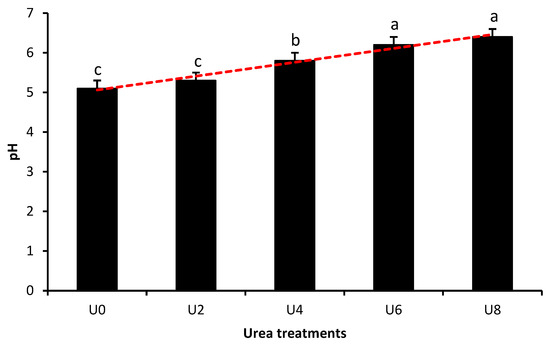

The overall effect of urea supplementation level on the pH of ensiled Opuntia spp. is shown in Figure 2. pH values increased linearly with increasing urea level (y = 5.06 + 0.18x, p < 0.001). The control (U0) and the U2 treatment had the lesser pH values (5.1 and 5.3, respectively), which were not significantly different from each other (p > 0.05). The U4 treatment displayed an intermediate pH value of 5.8, while the greatest pH values were observed in the U6 and U8 treatments (6.2 and 6.4, respectively), which were not significantly different from each other.

Figure 2.

Effect of urea supplementation level on the pH of ensiled Opuntia spp. Silage was treated with urea at 0 (U0), 2 (U2), 4 (U4), 6 (U6), or 8% (U8) of dry matter. pH values increased linearly with increasing urea level (red trend line; y = 5.06 + 0.18x, p < 0.001). Bars not sharing a common letter (a, b, c) differ significantly (p < 0.05). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

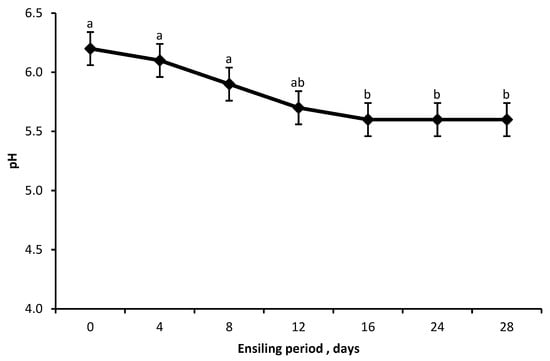

The pH of silages decreased in a quadratic trend (p < 0.001) as the duration of storage (ensiling periods) increased, beginning on d 0 at 6.2, remaining around 6.0 for the first 8 d of silage, and stabilizing at 5.6 from d 12 to 28 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of ensiling period on pH of ensiled Opuntia spp. The pH value decreased quadratically as the ensiling period increased (y = 6.2473 − 0.05776x + 0.001241x2, p < 0.001, minimum point x ≈ 23.3 days). Bars without a common letter (a, b) differ (p < 0.05). Error bars indicate standard error.

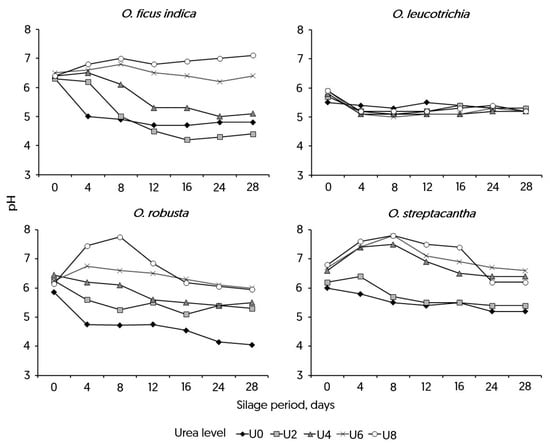

The interactions between Opuntia species and the ensiling period (p < 0.001), as well as the species and urea level (p < 0.001), were significant (see Figure 4). In the silage of OFI, the initial pH values were similar across different urea levels (p > 0.05). However, treatments U6 and U8 maintained alkaline conditions (approximately 6.5–7.0) throughout the study. The U4 treatment started around pH 6.0 but declined to below 5.5 after 12 d. In contrast, U2 dropped from above 6.0 at day 0 to 4.5 by day 12. U0 remained consistently acidic, ranging between approximately 5.0 and 4.8 during the period. For the OL species, the pH of the silage remained stable around 5.4, regardless of the urea level added. In the silage of OR, treatments U6 and U8 stayed above pH 6.0, while U4 declined from 6.5 at day 0 to below 5.5 after day 12. U2 remained below 5.5, and U0 stayed below 5.0. When urea was added to OS at levels U4 through U8, the pH curves were similar, rising beyond 6.2 by d 4 to 16 and then staying above that level. On the other hand, U0 and U2 stayed lower and followed similar patterns. In general, high urea levels (U6–U8) kept the pH level high, while low levels (U0–U2) the low levels could not sustain or increase the pH. U4 showed responses that were in between those of the other species.

Figure 4.

Effect of urea level and ensiling period on pH of four species of Opuntia spp. Urea was added to the silage at levels of 0 (U0), 2 (U2), 4 (U4), 6 (U6), or 8% (U8). Opuntia specie × ensiling period (p < 0.001) and Opuntia specie × urea level interactions were significant (p < 0.001).

3.2. In Situ Degradability Results

Degradability characteristics of the DM from the different species of Opuntia are shown in Table 2. A significant species effect (p < 0.05) was observed on the rapidly degradable fraction (a). OFI had the greatest value (0.492 g/g), which was significantly superior than that of OR (0.387 g/g). The values for OL (0.445 g/g) and OS (0.423 g/g) were intermediate and not statistically different from each other.

Table 2.

In situ digestibility coefficients and effective degradability of dry matter in Opuntia silages.

The potentially degradable fraction (b) differed (p < 0.05) among Opuntia species. The coefficient was greatest for OR (0.465) and lesser for OFI (0.375). OL (0.417) and OS (0.425) exhibited intermediate values that were not significantly different from each other. The potential degradability (a + b) of dry matter (DM) was greater (p < 0.05) for OL and OFI (0.862 and 0.867 g/g, respectively) than for OR and OS (0.852 and 0.848 g/g, respectively). The degradation rate (c) was significantly higher (p < 0.05) for OFI (0.094 h−1) than for OL, OS, and OR (0.078, 0.077, and 0.072 h−1, respectively), which were statistically similar. The EDDM at a ruminal outflow rate of 0.03% h−1 was greater her (p < 0.01) for OFI and OL (0.749 and 0.740, respectively) than for OS and OR (0.725 and 0.713, respectively).

Degradability characteristics of the DM of the Opuntia silage at different urea levels are shown in Table 3. The rapidly degradable fraction (a) was greater (p < 0.05) in the control (U0) than in any other urea treatment. For the potentially degradable fraction (b), the U2 level was significantly greater (p < 0.05) than the U0 control. The U4, U6, and U8 levels showed intermediate and statistically similar values. The potential degradability (a + b) was greatest and similar for the U0 and U2 treatments. The U4 and U6 treatments had intermediate values that were not significantly different from each other, while the U8 treatment had the least value. Furthermore, the a + b fraction decreased linearly with increasing urea level (y = 0.87 − 0.005x, p = 0.0107).

Table 3.

Coefficients of In Situ digestibility parameters and effective degradability of dry matter of Opuntia silage added with different levels of urea.

Fraction c was greater in treatments with urea at levels of U2, U4, and U6 compared with levels of U0 and U8. The EDDM at a ruminal outflow rate of 0.03 h−1 was similar for U0, U2, U4, and U6 of urea addition, but were greater than U8 urea level.

Degradability parameters of dry matter across ensiling periods are shown in Table 4. Fractions a and b did not differ (p > 0.05). among periods. Potential degradability (a + b) was greater (p < 0.05) at day 0 than at subsequent incubation periods. Conversely, the degradation rate (fraction c) was lower (p < 0.05) at day 0 than in later periods. The EDDM at a ruminal outflow rate of 0.03 h−1 did not differ among incubation periods (p > 0.05). Both the degradation rate (c) and EDDM showed a quadratic increase (p < 0.05) over time, reaching their maximum values at 16.5 days (y = 0.0687 + 0.0033x − 0.0001x2) and 19.8 days (y = 0.7263 + 0.001x − 0.00003x2), respectively. Overall, the potentially degradable fraction decreased after ensiling, while microbial activity (as indicated by c) became more efficient, thereby stabilizing the effective degradability.

Table 4.

Coefficients of In Situ digestibility parameters and effective degradability of dry matter of Opuntia silage at different ensiling periods.

3.3. Chemical Composition Outcomes

The values of the chemical composition are shown in Table 5. There were no differences (p > 0.05) or tendencies (p > 0.05) in DM, Ash, EE, NDF, and ADF among Opuntia silages treated with urea levels. The crude protein (CP) content of all four Opuntia varieties exhibited significant linear and quadratic responses (p < 0.01 for both) to increasing urea levels. The resulting quadratic equations were: y = 48.8 + 2.29x + 0.005x2 for OFI; y = 10.6 + 4.045x − 0.0113x2 for OL; y = 43.37 + 2.578x + 0.002x2 for OR; and y = 48.029 + 2.052x + 0.008x2 for OS. The maximum theorical values were −229 for OFI, 179.0 for OL, −644 for OR, and −128 for OS.

Table 5.

Chemical composition of silage from four Opuntia species supplemented with different urea levels.

4. Discussion

4.1. Silage pH Responses

Silage pH is an essential indicator of the acidity and overall effectiveness of the conservation process. In this study, baseline pH prior to ensiling was not measured. Therefore, interpretations of pH dynamics rely on post-ensiling measurements. While ideal fermentation is achieved at a pH below 4.2, a value below 5.5 is often considered acceptable, as it significantly reduces the activity of spoilage bacteria, such as clostridia and enterobacteria [31]. Few studies have reported the pH in Opuntia silage. In this study, the stabilization of silage pH after approximately 12 d (Figure 3 and Figure 4) across all Opuntia species indicates that fermentation was effective, even though absolute pH values remained higher than the conventional threshold (<4.2) expected in grass or maize silages. This finding is consistent with earlier reports that attribute the relatively high pH of cactus silages to their buffering capacity and chemical composition [32,33,34].

This balance between pH and ammonification can be explained by the interaction between lactic acid production and ammonification derived from urea hydrolysis. When urea is added to silage, urease enzymes rapidly hydrolyze it into ammonia and carbon dioxide, increasing the buffering capacity and tending to elevate pH [35]. In most cases, moderate urea addition can be offset by sufficient lactic acid production, maintaining fermentation stability, whereas excessive ammonification can hinder acidification and delay stabilization [36]. In Opuntia silages, this balance is particularly important because the naturally high moisture content and low lignin concentration lead to a unique fermentation profile compared with traditional fibrous forages [37,38].

These results support the idea that Opuntia silages follow a distinct fermentation pattern, driven by their intrinsic chemical properties and the interaction with added urea. As a result, fermentation can be considered effective at slightly higher pH values than the conventional threshold, provided ammonification does not exceed the acidification capacity. This explains why the greatest pH values were recorded in the U8 treatment across species (Figure 2 and Figure 4). This alkaline environment not only affects the conservation quality of the silage but also correlates with the reduced degradability observed at this level, as it suggests a less favorable substrate for ruminal microbial colonization and activity. This reinforces the need to account for species-specific responses and appropriate urea inclusion levels when formulating cactus-based silages [39].

It is important to note that the interpretation of pH dynamics and the adverse effects of high urea levels is limited by the absence of data on organic acids, ammonia-N, and water-soluble carbohydrates. Therefore, the explanations presented should be regarded as plausible hypotheses rather than definitive conclusions.

4.2. In Situ Degradability Findings

The study of the in situ degradability of dry matter (DM) was developed by Ørskov and McDonald and is widely adopted to characterize the forage quality by identifying rapidly (fraction a) and slowly (fraction b) degradable components, which are indicative of its nutritional potential [28]. However, studies about ruminal degradability and kinetic parameters for the Opuntia genus plants are limited.

The in situ DM degradability values (a, b, a + b, c, and EDDM) obtained here were elevated across all species (Table 2), confirming the well-known digestibility of Opuntia cladodes due to their high content of soluble carbohydrates and low lignin levels [40,41,42]. A key novel finding of this study is that urea supplementation, although effective in increasing CP (p < 0.01), did not enhance degradability (p > 0.05). Although the quadratic models predicted (p < 0.01) a continuous increase in crude protein (CP) with urea addition, the theoretical maximum for all Opuntia species (Table 5), the vertex theorical values were −229 for OFI, 179.0 for OL, −644 for OR, and −128 for OS) was outside the tested range and beyond practical application. Furthermore, at the highest inclusion level (80 g/kg DM), a reduction (p < 0.05) in degradability was observed, indicating that excessive urea could negatively impact ruminal fermentation balance. This response differs from studies where urea treatment typically improves the digestibility of forages [43], likely because Opuntia silages already have inherently low NDF and ADF contents. Therefore, despite the greatest (p < 0.01) measured CP content occurring at 80 g/kg DM, this level is not recommended due to the associated decline in fermentative quality.

Opuntia species contain substantial amounts of non-fiber carbohydrates (NFCs) (approximately 500 g/kg DM), water-soluble carbohydrates (WSCs) (150 g/kg), and total carbohydrates (TCs) (617–711 g/kg) [8,9]. However, their low concentrations of NDF (approximately 250 g/kg) and crude protein (CP) (33–44 g/kg) [8] limit their use as a sole roughage source in ruminant diets. Consequently, it is often necessary to combine Opuntia with other feed components to address these nutritional limitations and achieve a balanced ration.

The urea addition on cactus diets has been evaluated previously by [23]. They reported that nitrogen supplementation of cactus-based diets with urea-treated straw or Atriplex foliage improved (p < 0.05) the feeding value of these diets. In addition, Mixing spineless cactus with fiber- or protein-rich plants can compensate for its low dry matter content and enhance its suitability for ensiling—a common preservation technique used to store surplus forage produced during the rainy season for use during periods of scarcity [9]. Godoi et al. [38] evaluated a mixed silage composed of spineless cactus and tropical forage plants (pornuça and gliricidia) in a 60:40 dry matter ratio for feeding sheep. This combination improved (p < 0.05) nutrient intake and digestibility compared to cactus silage alone, which had an NFC content exceeding recommended levels for ruminant diets and was associated with reduced CP digestibility.

Regarding in situ degradability and its potential impact on ruminal microorganisms, the results can be explained by the parameter c (rate of dry matter degradation). The slowest (p < 0.05) degradation rate at U0 suggesting a positive effect on ruminal microbial activity (Table 3). In contrast, the reduction (p < 0.05) in degradability at the maximum urea level (U8) can be attributed to several plausible mechanisms [44,45], listed in order of likelihood: (i) Inhibition of fibrolytic microbes: Excess ruminal ammonia can directly inhibit the growth and activity of cellulolytic bacteria, crucial for fiber degradation. (ii) Asynchronous fermentation: A rapid release of ammonia may not be synchronized with the availability of fermentable energy from the soluble carbohydrates, leading to inefficient microbial protein synthesis and overall fermentation. (iii) Osmotic effects: The high osmolarity in the silage and subsequently in the rumen from high urea and mineral content could negatively impact microbial colonization of the feed particle.

The relationship between dietary NPN and DM degradability is well-known. The NPN supplementation typically promotes rumen microbial growth and increases degradability [22]. However, in this study, urea addition did not markedly affect EDDM, likely Opuntia silages are low in NDF content, as forages with high NDF content typically show a more pronounced response to urea treatment [46,47].

Although percentage increases in CP differed among species (e.g., O. robusta ≈ +495% vs. O. leucotrichia ≈ +424% at U8), these contrasts primarily reflect baseline CP differences prior to ensiling (Table 1). At U8, the absolute CP increment was similar across species (≈ +214–219 g kg−1 FM; Table 5), consistent with analytical incorporation of urea-N rather than species-specific enhancement of true protein synthesis. Species factors (e.g., urease activity, moisture/ash buffering, and pH profiles) may modulate ammonia retention, but they did not translate into higher EDDM.

Thus, the role of urea in cactus silages appears to be nutritional enrichment (as a nitrogen source) rather than structural modification of the fiber matrix. The inherently low fiber content of Opuntia may have made it particularly susceptible to this negative balance, where the benefit of extra nitrogen was outweighed by the detrimental shift in fermentation conditions. The integration of urea-treated Opuntia silage can serve as a critical strategic supplement, particularly in production systems or rangelands where animals consume diets deficient in CP and high in NDF [11,12].

4.3. Chemical Composition Changes

The CP content of Opuntia species varies widely among species and regions, influenced by soil, management, and climate [42]. Reported values range from less than 40 g/kg in some OFI varieties [40] to nearly 200 g/kg in hydroponically grown cladodes [43]. Our results fall within this broad range and confirm previous findings that OFI generally contains more CP than other species, such as OR [48,49].

As expected, urea supplementation increased (p < 0.01) CP across all species, reflecting the incorporation of non-protein nitrogen during ensiling [50,51]. Similar responses have been reported in other low-protein forages [52]. Nevertheless, even with supplementation, the native CP levels of Opuntia remain too low to sustain optimal rumen microbial activity, confirming that cactus silages should be used as part of balanced rations rather than as a sole feed.

Ash concentrations in our study were relatively elevated (Table 5), consistent with earlier reports for both wild and cultivated Opuntia [48,53,54], though minor values have been documented in certain varieties [43]. Such variation is largely explained by mineral availability in the soil and plant maturity [54]. Furthermore, the elevated ash content observed, while contributing to the buffering capacity of the silage [55], also has implications for mineral nutrition and electrolyte balance. Furthermore, Opuntia species are known to contain oxalates that bind calcium, thereby reducing its bioavailability [56,57,58,59]. A detailed mineral profile including oxalate content was beyond the scope of this study but is recommended for future work to fully assess the nutritional value and limitations of Opuntia silages.

The EE content in animal feeds represents the lipid or fat fraction of the forage (fats, fatty acid esters and fat-soluble vitamins, waxes, and pigments soluble in ether) and are often referred to as crude fat [60]. The ether extract (EE) fraction averaged about 25 g/kg (Table 4), which is typical for forages [61]. These results agree with values reported for OFI silages [62] and are slightly above the range observed in wild Opuntia species [42].

Levels of NDF (the structural cell wall fraction, cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin) and ADF (the least digestible fiber fractions, cellulose and lignin) content are critical as their amounts determine the extent of forage digestion in livestock %) [61]. The NDF and ADF values observed in the Opuntia species studied in this trial (Table 5) are consistent with previous findings [40,48,49]. This contrasts sharply with findings in grass straws [43,60], where urea treatment significantly modified the fiber profile by increasing ADF and hemicellulose while reducing NDF [63]. The low levels of NDF and ADF indicate that Opuntia silage is highly digestible, with low “rumen filling” effect. Furthermore, the analysis of protein fractions, including Neutral and Acid Detergent Insoluble Nitrogen, was not performed and should be considered in future studies to better understand nitrogen utilization.

Fiber content (NDF, ADF, etc.) often inversely relates to digestibility: greater fiber can dilute digestible starch and energy, reducing OM digestibility, while lesser fiber generally supports greater digestibility [64]. This discrepancy underscores a fundamental difference in how urea interacts with the fibrous matrix of Opuntia compared with grasses, most likely due to the naturally low lignin and high pectin content of cactus cladodes [65]. A comprehensive analysis of the fermentation profile, including organic acids and dry matter losses, was not performed but is warranted in future studies to fully characterize the ensiling process of urea-treated Opuntia.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that cladodes from Opuntia ficus-indica, O. leucotrichia, O. streptacantha, and O. robusta can be successfully ensiled, achieving stable pH values after approximately 12 d. Urea supplementation consistently increased crude protein content and altered the pH of the silages. However, the addition of urea did not enhance the effective degradability of DM, and the length of the ensiling period had no significant effect on degradability parameters. The addition of urea at 80 g/kg reduces the degradability values; therefore it is recommended that the addition of urea in Opuntia silages should not exceed 60 g/kg DM to avoid reduced fermentative quality. These results indicate that while urea supplementation is effective in improving the crude protein concentration of Opuntia silages, their inherent digestibility remains largely unaffected by either urea level or ensiling duration. Therefore, the primary contribution of urea is its role as a non-protein nitrogen source, rather than as a factor modifying fiber degradation dynamics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, all authors; methodology, F.M.-L. and J.I.A.-S.; formal analysis, M.A.L.-C.; investigation, F.M.-L. and J.I.A.-S.; resources, F.M.-L. and J.I.A.-S.; data curation, M.A.L.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, F.M.-L.; writing—review and editing J.I.A.-S. and M.A.L.-C.; visualization, J.I.A.-S.; supervision, M.A.L.-C.; project administration, F.M.-L.; funding acquisition, all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The experiment reported herein was approved of Bioethics and Animal Welfare Committee of UAMVZ-UAZ, with protocol number 2020/01. The trial was conducted at the UAMVZ-UAZ in Gral. Enrique Estrada, Zac., Mexico.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the personnel of the Animal Feed Processing Plant of the Veterinary Medicine and Zootechnics Academic Unit of the University of Zacatecas for assistance in the mixing of the diets.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification. The Global Threat of Drying Lands: Regional and Global Aridity Trends and Future Projections. In A Report of the Science-Policy Interface; United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification: Bonn, Germany, 2024; Available online: https://www.unccd.int/sites/default/files/2024-12/aridity_report.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Safriel, U.; Adeel, Z. Dryland Systems. In Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Current State and Trends; Hassan, R., Scholes, R., Ash, N., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; Volume 1, pp. 623–662. [Google Scholar]

- Fust, P.; Schlecht, E. Importance of timing: Vulnerability of semi-arid rangeland systems to increased variability in temporal distribution of rainfall events as predicted by future climate change. Ecol. Model. 2022, 468, 109961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nefzaoui, A.; Ben Salem, H.; Inglese, P. Opuntia spp. a strategic fodder and efficient tool to combat desertification in the Wana region. In Cactus (Opuntia spp.) as Forage; Mondragón-Jacobo, C., Pérez-González, S., Eds.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2001; pp. 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Louhaichi, M.; Yigezu, Y.A.T.; Hassan, S.; Naorem, A.; Meta-Gonzales, R.; Kumar, S.; Hamdeni, I.; Palsaniya, D.R.; Kauthale, V.K.; Al-Mahasneh, A.M.; et al. Characterization of cactus pear (Opuntia ficus-indica) production systems and analysis of the adoption and economic viability of spineless cactus for animal feed in four continents. Cogent Food Agric. 2025, 11, 2550493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorelli, G.; Serra, V.; Vannuccini, C.; Attard, E. Opuntia spp. as alternative fodder for sustainable livestock production. Animals 2022, 12, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.G.; Treviño, I.H.; de Medeiros, G.R.; Medeiros, A.N.; Pinto, T.F.; de Oliveira, R.L. Effects of replacing corn with cactus pear (Opuntia ficus indica Mill) on the performance of Santa Inês lambs. Small Rumin. Res. 2012, 102, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Llorente, F.; Ramirez-Lozano, R.G.; Lopez-Carlos, M.A.; Rodriguez-Frausto, H.; Arechiga-Flores, C.F.; Bonilla-Salazar, A.; Nuñez-González, A.M.; Aguilera-Soto, J.I. Performance and nutrient digestion of lambs fed incremental levels of wild cactus (Opuntia leucotrichia). J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2011, 39, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Montemayor, H.M.; Cordova-Torres, A.V.; García-Gasca, T.; Kawas, J.R. Alternative foods for small ruminants in semiarid zones, the case of Mesquite (Prosopis laevigata spp.) and Nopal (Opuntia spp.). Small Rumin. Res. 2011, 98, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista Dubeux, J.C., Jr.; Santos, M.V.F.; Cunha, M.V.; Santos, D.C.; Souza, R.T.A.; Mello, A.C.L.; Silva, M.C. Cactus (Opuntia and Nopalea) nutritive value: A review. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2021, 275, 114890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipango, N.; Ravhuhali, K.E.; Sebola, N.A.; Hawu, O.; Mabelebele, M.; Mokoboki, H.K.; Moyo, B. Prickly Pear (Opuntia spp.) as an Invasive Species and a Potential Fodder Resource for Ruminant Animals. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Soto, J.I.; Aréchiga-Flores, C.F.; Ramírez, R.G. Utilización del nopal en nutrición animal. In El Nopal en la Producción Animal; Aréchiga-Flores, C.F., Aguilera-Soto, J.I., Valdez-Cepeda, R.D., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas: Zacatecas, Mexico, 2007; p. 149. [Google Scholar]

- Dutra, I.C.; Pires, A.J.V.; dos Santos, B.E.F.; da Silva, N.V.; Pio, L.P.; Cruz, N.T.; Sousa, M.P.; de Dutra, G.C. Forage cactus (Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Miller) f. Cactaceae as an alternative for ruminant feeding. Braz. J. Sci. 2024, 3, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniaci, G.; Ponte, M.; Giosuè, C.; Gannuscio, R.; Pipi, M.; Gaglio, R.; Busetta, G.; Di Grigoli, A.; Bonanno, A.; Alabiso, M. Cladodes of Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) as a source of bioactive compounds in dairy products. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 1887–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumadong, P.; So, S.; Cherdthong, A. The benefits of adding sulfur and urea to a concentrate mixture on the utilization of feed, rumen fermentation, and milk production in dairy cows supplemental fresh cassava root. Vet. Med. Int. 2022, 2022, 9752400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundstol, F.; Coxworth, E.M. Ammonia Treatment. In Straw and Other Fibrous By-Products as Feed; Sundstol, F., Owen, E., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1984; pp. 196–247. [Google Scholar]

- El-Zaiat, H.M.; Kholif, A.E.; Khattab, I.M.; Sallam, S.M. Slow-release urea partially replacing soybean in the diet of Holstein dairy cows: Intake, blood parameters, nutrients digestibility, energy utilization, and milk production. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2022, 22, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, S.; Wildner, V.; Schulze, J.; Richardt, W.; Greef, J.M.; Zeyner, A.; Steinhöfel, O. Chemical treatment of straw for ruminant feeding with NaOH or urea–investigative steps via practical application under current European Union conditions. Agric. Food Sci. 2022, 31, 260–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degu, A.; Melaku, S.; Berhane, G. Supplementation of isonitrogenous oil seed cakes in cactus (Opuntia ficus-indica)–tef straw (Eragrostis tef) based feeding of Tigray Highland sheep. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2009, 148, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.-W.; Faciola, A.P. Impacts of Slow-Release Urea in Ruminant Diets: A Review. Fermentation 2024, 10, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurak, D.; Kljak, K.; Aladrović, J. Metabolism and utilization of non-protein nitrogen compounds in ruminants: A review. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2023, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, S.; Rady, A.; Attia, M.F.; Elazab, M.A.; Vargas-Bello-Pérez, E.; Kholif, A.E. Different maize silage cultivars with or without urea as a feed for ruminant: Chemical composition and in vitro fermentation and nutrient degradability. Chil. J. Agric. Anim. Sci. 2024, 40, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Salem, H.; Nefzaoui, A.; Ben Salem, L. Supplementing spineless cactus (Opuntia ficus-indica f. inermis) based diets with urea-treated straw or oldman saltbush (Atriplex nummularia). Effects on intake, digestion and sheep growth. J. Agric. Sci. 2002, 138, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INIFAP. Red de Monitoreo Agroclimático del Estado de Zacatecas Boletines Mensuales; INIFAP: Zacatecas, Mexico, 2019; Available online: http://zacatecas.inifap.gob.mx/boletines.php?id=18851 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Da Silva, D.D.; De Andrade, A.P.; Da Silva, D.S.; Alves, F.A.L.; De Lima Valença, R.; Santos, D.C.D.; De Medeiros, A.N.; Araújo, F.D.S.; Lima, L.K.S.; Bruno, R.D.L.A. Nutritional Quality of Opuntia ssp. at Different Phenological Stages: Implications for Forage Purposes. J. Agric. Stud. 2021, 10, 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiuolo, J.; Nucera, S.; Serra, M.; Caminiti, R.; Oppedisano, F.; Macrì, R.; Scarano, F.; Ragusa, S.; Muscoli, C.; Palma, E.; et al. Cladodes of Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill. Possess Important Beneficial Properties Dependent on Their Different Stages of Maturity. Plants 2024, 13, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ørskov, E.R.; Hovell, F.D.; Mould, F. The use of the nylon bag technique for the evaluation of feedstuffs. Trop. Anim. Prod. 1980, 5, 195–213. Available online: https://www.cipav.org.co/TAP/TAP/TAP53/53_1.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Ørskov, E.R.; McDonald, I. The estimation of protein degradability in the rumen from incubation measurements weighted according to rate of passage. J. Agric. Sci. 1979, 92, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littell, R.C.; Henry, P.R.; Ammerman, C.B. Statistical analysis of repeated measures data using SAS procedures. J. Anim. Sci. 1998, 76, 1216–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, I. A revised model for the estimation of protein degradability in the rumen. J. Agric. Sci. 1981, 96, 251–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooke, J.A.; Hatfield, R.D. Biochemistry of ensiling. In Silage Science and Technology; Buxton, D.R., Muck, R.E., Harrison, J.H., Eds.; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 2003; pp. 95–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çürek, M.; Özen, N. Feed value of cactus and cactus silage. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2004, 28, 633–639. Available online: https://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/veterinary/vol28/iss4/1?utm_source=journals.tubitak.gov.tr%2Fveterinary%2Fvol28%2Fiss4%2F1&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Stintzing, F.C.; Carle, R. Cactus stems (Opuntia spp.): A review on their chemistry, technology, and uses. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2005, 49, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muck, R.; Nadeau, E.; McAllister, T.; Contreras-Govea, F.; Santos, M.; Kung, L., Jr. Silage review: Recent advances and future uses of silage additives. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 3980–4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmley, E. Towards improved silage quality—A review. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2001, 81, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muck, R.E. Factors Influencing Silage Quality and Their Implications for Management. J. Dairy Sci. 1988, 71, 2992–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoi, P.F.A.; Magalhães, A.L.R.; de Araújo, G.G.L.; de Melo, A.A.S.; Silva, T.S.; Gois, G.C.; dos Santos, K.C.; do Nascimento, D.B.; da Silva, P.B.; de Oliveira, J.S.; et al. Chemical Properties, Ruminal Fermentation, Gas Production and Digestibility of Silages Composed of Spineless Cactus and Tropical Forage Plants for Sheep Feeding. Animals 2024, 14, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Cervantes, M.; Ramírez, R.G.; Cerrillo-Soto, M.A.; Montoya-Escalante, R.; Nevárez-Carrasco, G.; Juarez-Reyes, A.S. Dry matter digestion of native forages consumed by range goats in North Mexico. J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 2009, 8, 408–412. Available online: https://www.makhillpublications.co/public/index.php/view-article/1680-5593/javaa.2009.408.412 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Batista, A.M.V.; Ribeironeto, A.C.; Lucena, R.B.; Santos, D.C.; Dubeux, J.C.B., Jr.; Mustafa, A.F. Chemical Composition and Ruminal Degradability of Spineless Cactus Grown in Northeastern Brazil. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 62, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, A.M.V.; Mustafa, A.F.; McAllister, T.; Wang, Y.; Soita, H.; McKinnon, J. Effects of variety on chemical composition, in situ nutrient disappearance and in vitro gas production of spineless cacti. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2003, 83, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Rodriguez, J. A comparison of the nutritional value of Opuntia and Agave plants for ruminants. J. Prof. Assoc. Cactus Dev. 1997, 2, 20–23. Available online: https://jpacd.org/jpacd/article/download/176/167/277 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Ramirez-Tobias, H.M.; Reyes-Agüero, J.A.; Pinos-Rodríguez, J.M.; Aguirre-Rivera, J.R. Efecto de la especie y madurez sobre el contenido de nutrientes de cladodios de nopal. Agrociencia 2007, 41, 619–626. Available online: https://www.agrociencia-colpos.org/index.php/agrociencia/article/view/569/569 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Castillo-González, A.R.; Burrola-Barraza, M.E.; Domínguez-Viveros, J.; Chávez-Martínez, A. Rumen microorganisms and fermentation. Arch. Med. Vet. 2014, 46, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagali, P.; Pelech, I.; Sabastian, C.; Ben Ari, J.; Tagari, H.; Mabjeesh, S.J. The Effect of Microbial Inoculum and Urea Supplements on Nutritive Value, Amino Acids Profile, Aerobic Stability and Digestibility of Wheat and Corn Silages. Animals 2023, 13, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Romero, N.; Abarca, F.; Herrera, J.; Bórquez, J.L. Efecto de la urea sobre la composición química y digestibilidad de paja de trigo. Arch. Med. Vet. 2002, 34, 91–98. Available online: https://ojs.alpa.uy/index.php/ojs_files/article/download/17/13/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Guedes, C.M.; Rodrigues, M.M.; Gomes, M.J.; Silva, S.R.; Ferreira, L.M.; Mascarenhas-Ferreira, A. Urea treatment of whole-crop triticale at four growth stages: Effects on chemical composition and on in vitro digestibility of cell wall. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2006, 86, 964–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Haliscak, J.A. Evaluación de la Productividad y Caracterización de Tres Variedades de Nopal Mejorado y Tres Criollos. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Monterrey, México, 2015. Available online: http://eprints.uanl.mx/13646/1/1080238031.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Pinos-Rodríguez, J.M.; Duque-Briones, R.; Reyes-Agüero, J.A.; Aguirre-Rivera, J.R.; García-López, J.C.; González-Muñoz, S. Effect of Species and Age on Nutrient Content and in vitro Digestibility of Opuntia spp. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2006, 30, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aregheore, E.M. Effect of Yucca schidigera saponin on the nutritive value of urea-ammoniated maize stover and its feeding value when supplemented with forage legume Calliandra calothyrsus for goats. Small Rumin. Res. 2005, 56, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fall, S. Utilisation Digestive par les Ruminants Domestiques de Ligneux Fourrages Disponibles au Senegal; Rapport ISRA-LNERV No. 59 Ahm. Nut.: Dakar, Senegal, 1988; p. 100. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, J.J.; Tarnonsky, F.; Podversich, F.; Maderal, A.; Fernandez-Marenchino, I.; Gómez-López, C.; Heredia, D.; Schulmeister, T.M.; Ruiz-Ascacibar, I.; Gonella-Diaza, A.; et al. Impact of Supplementing a Backgrounding Diet with Nonprotein Nitrogen on In Vitro Methane Production, Nutrient Digestibility, and Steer Performance. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzak, S.; Aouji, M.; Zirari, M.; Benchehida, H.; Taibi, M.; Bengueddour, R.; Wondmie, G.F.; Ibenmoussa, S.; Bin Jardan, Y.A.; Taboz, Y. Nutritional Composition, Functional and Chemical Characterization of Moroccan Opuntia ficus-indica Cladode Powder. Int. J. Food Prop. 2024, 27, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubeux, J.C.B., Jr.; Santos, M.V.F.; Lira, M.A.; Santos, D.C.; Farias, I.; Lima, L.E.; Ferreira, R.L.C. Productivity of Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Miller under different N and P fertilization and plant population in north-east Brazil. J. Arid Environ. 2006, 67, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharrery, A. The determination of buffering capacity of some ruminant feedstuffs and their cumulative effects in TMR ration. Am. J. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2007, 2, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Padilla, M.; Pérez, D.M.; Torrero, E. Evaluation of oxalates and calcium in nopal pads (Opuntia ficus-indica var. redonda) at different maturity stages. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011, 24, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Molina, I.; Ariza-Colpas, P.; Vicente, A.; Almanza, N. Characterization of calcium compounds in Opuntia ficus-indica. J. Chem. 2015, 2015, 710328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero-García, M.; Gutiérrez-Cortez, E.; Rojas-Molina, I.; Mendoza-Ávila, M.; Del Real, A.; Rubio, E.; Jiménez-Mendoza, D. Calcium Bioavailability of Opuntia ficus-indica Cladodes in an Ovariectomized Rat Model of Postmenopausal Bone Loss. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.; Ferreira, A.R.B.; de Oliveira, J.P.R.; Bedin, K.C. Physicochemical, nutritional, and medicinal properties of Opuntia species: A review. Plants 2023, 12, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nortjie, E.; Basitere, M.; Moyo, D.; Nyamukamba, P. Extraction Methods, Quantitative and Qualitative Phytochemical Screening of Medicinal Plants for Antimicrobial Textiles: A Review. Plants 2022, 11, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoch, R. Nutritional Quality Estimation of Forages. In Nutritional Quality Management of Forages in the Himalayan Region; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 263–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mciteka, H. Fermentation Characteristics and Nutritional Value of Opuntia Ficus-indica var. Fusicaulis Cladode Silage. Ph.D. Thesis, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Caneque, V.; Velasco, S.; Sancha, J.L.; Manzanares, C.; Souza, O. Effect of moisture and temperature on the degradability of fiber and on nitrogen fractions in barley straw treated with urea. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1998, 74, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukrouh, S.; Noutfia, A.; Moula, N.; Avril, C.; Louvieaux, J.; Hornick, J.; Cabaraux, J.; Chentouf, M. Ecological, morpho-agronomical, and bromatological assessment of sorghum ecotypes in Northern Morocco. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, A.; Ateeq, R.; Ismail, E.; Cheikhyoussef, N.; Cheikhyoussef, A. Opuntia spp. in Biogas Production. In Opuntia spp.: Chemistry, Bioactivity and Industrial Applications; Ramadan, M.F., Ayoub, T.E.M., Rohn, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 727–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).