Sensitivity of Soil Moisture Simulations to Noah-MP Parameterization Schemes in a Semi-Arid Inland River Basin, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

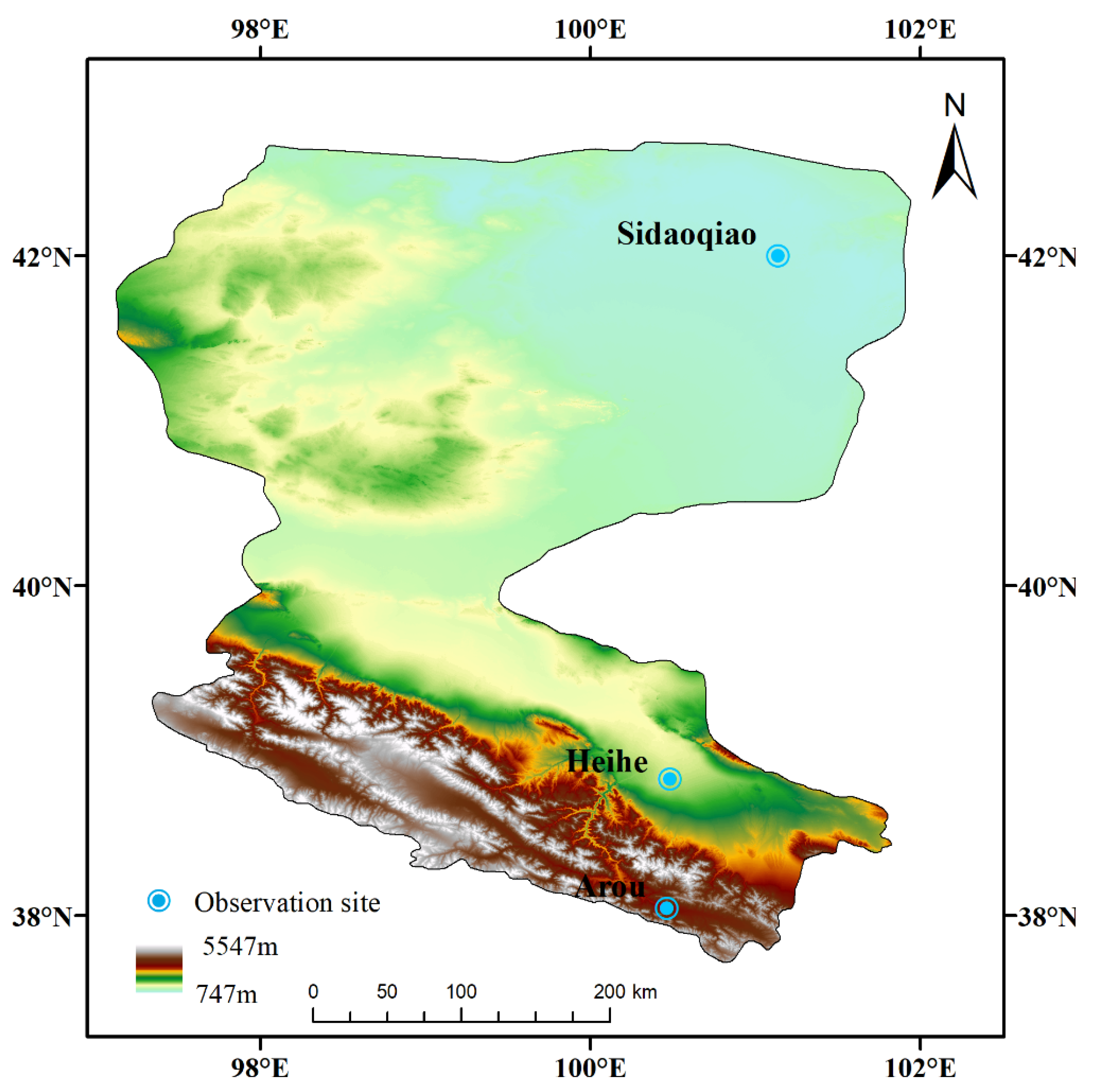

2.1. Study Sites and Data

2.2. Noah-MP Default Parameterization and Physics Ensemble Numerical Experiment

2.3. Analysis and Evaluation Methods

3. Results

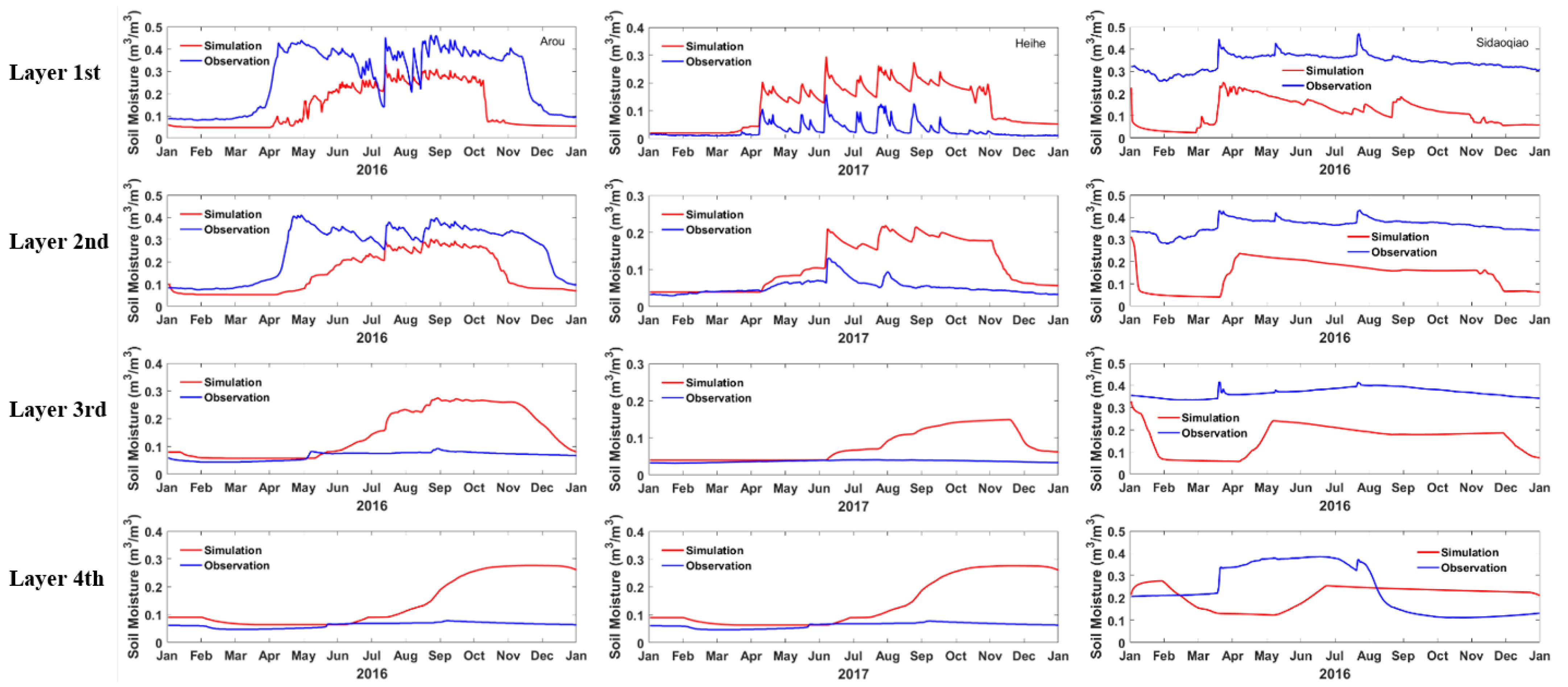

3.1. Soil Moisture Simulated by Default Parameterization Combination

3.2. Sensitivities of Physical Parameterization Schemes

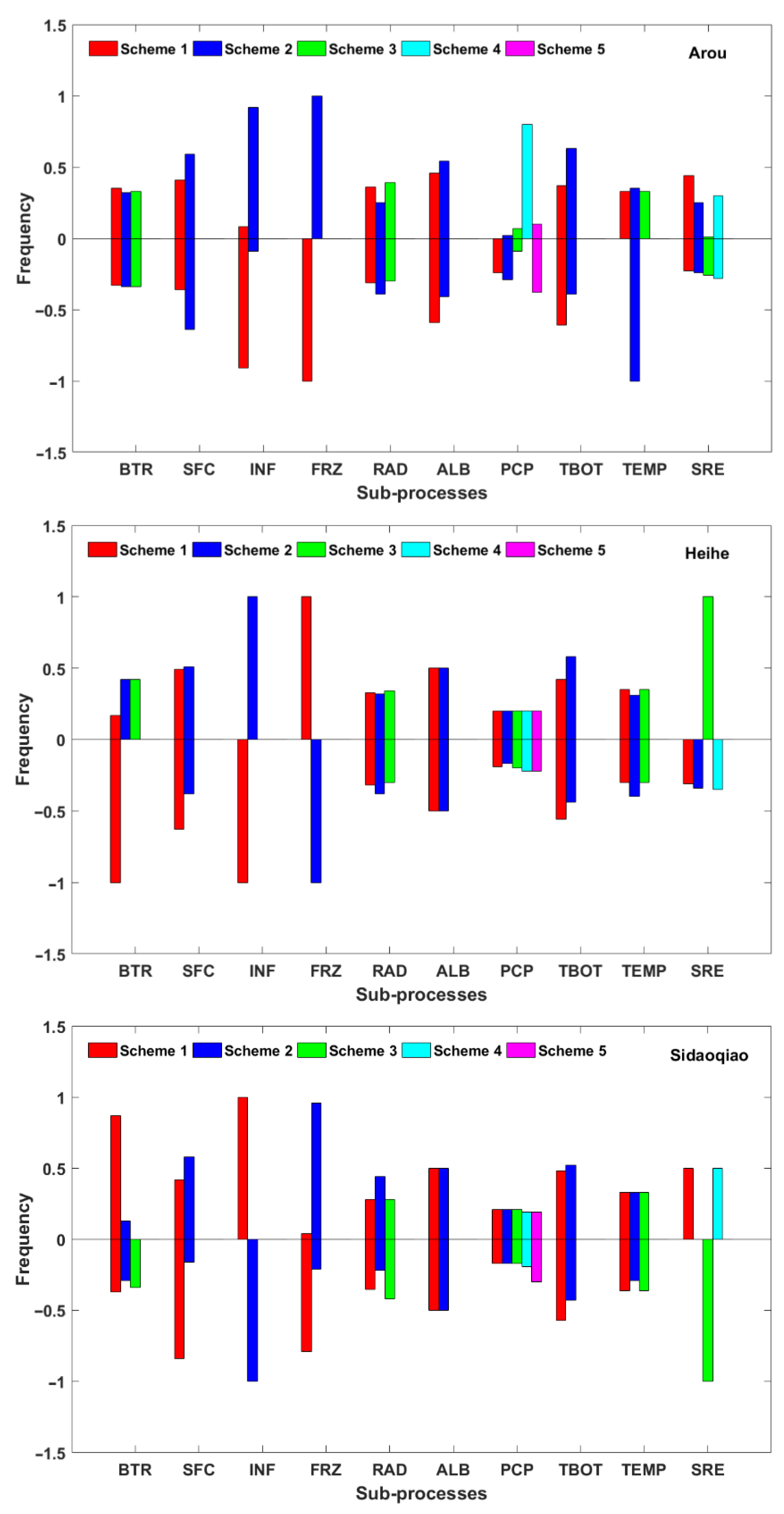

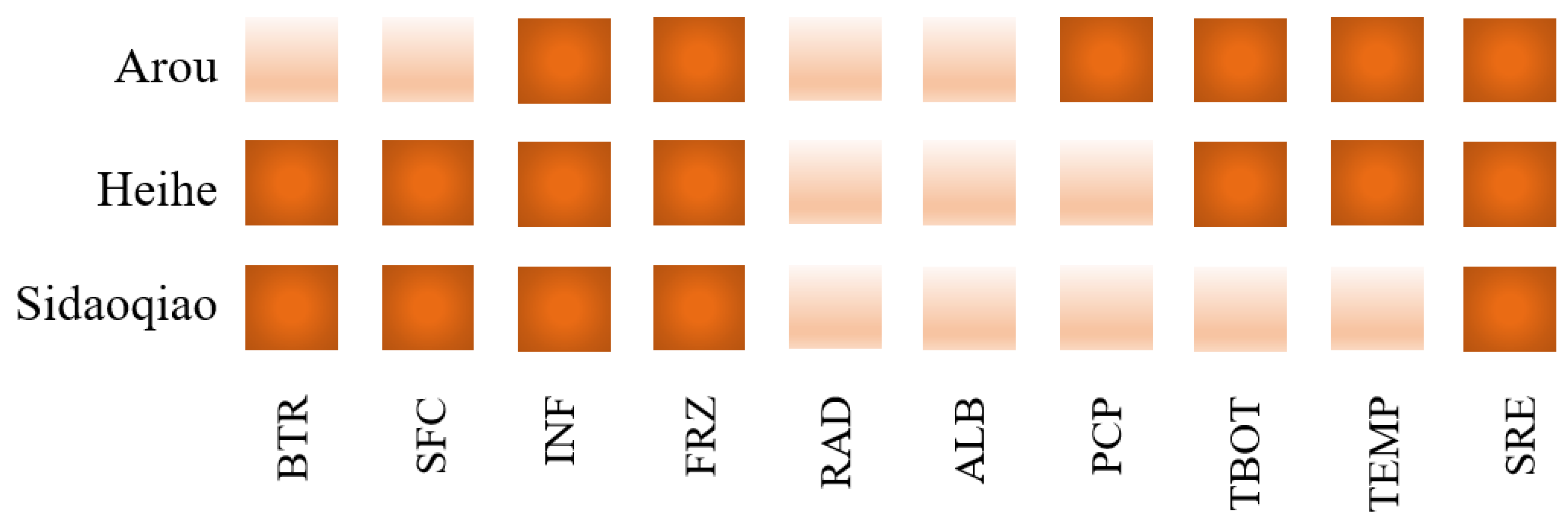

3.2.1. Natural Selection Results

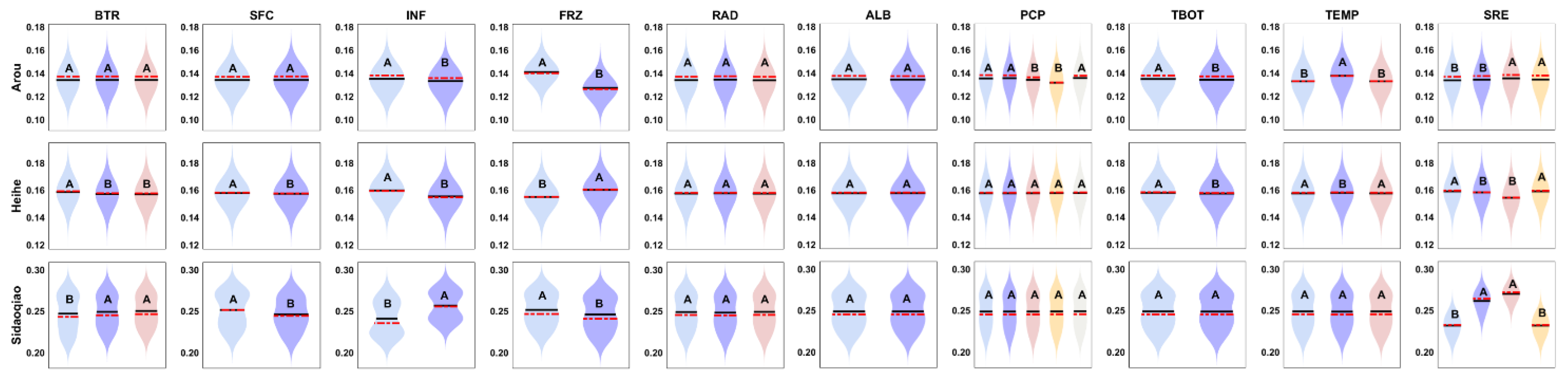

3.2.2. Tukey Test Results

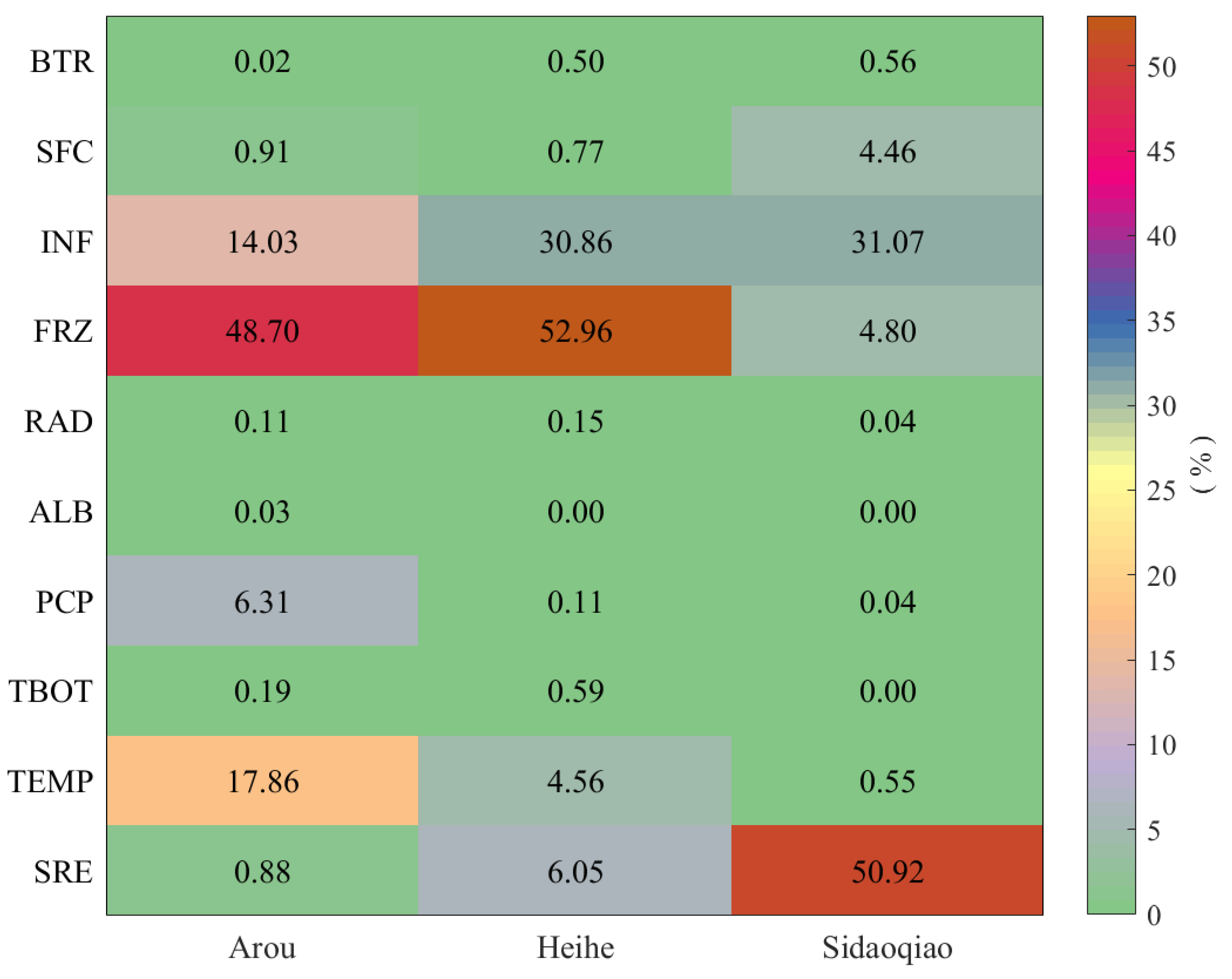

3.3. Uncertainty Contribution Analysis of Physical Options

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sepulcre-Canto, G.; Horion, S.; Singleton, A.; Carrao, H.; Vogt, J. Development of a Combined Drought Indicator to detect agricultural drought in Europe. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 12, 3519–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.V.; Peters-Lidard, C.D.; Santanello, J.A.; Reichle, R.H.; Draper, C.S.; Koster, R.D.; Nearing, G.; Jasinski, M.F. Evaluating the utility of satellite soil moisture retrievals over irrigated areas and the ability of land data assimilation methods to correct for unmodeled processes. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 19, 4463–4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massari, C.; Brocca, L.; Tarpanelli, A.; Moramarco, T. Data assimilation of satellite soil moisture into rainfall-runoff modelling: A complex recipe? Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 11403–11433. [Google Scholar]

- Azimi, S.; Dariane, A.B.; Modanesi, S.; Bauer-Marschallinger, B.; Bindlish, R.; Wagner, W.; Massari, C. Assimilation of sentinel 1 and SMAP-based satellite soil moisture retrievals into SWAT hydrological model: The impact of satellite revisit time and product spatial resolution on flood simulations in small basins. J. Hydrol. 2020, 581, 124367. [Google Scholar]

- Vereecken, H.; Huisman, J.A.; Bogena, H.; Vanderborght, J.; Vrugt, J.A.; Hopmans, J.W. On the value of soil moisture measurements in vadose zone hydrology: A review. Water Resour. Res. 2008, 44, W00D06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heathman, G.C.; Cosh, M.H.; Han, E.; Jackson, T.J.; McKee, L.; McAfee, S. Field scale spatiotemporal analysis of surface soil moisture for evaluating point-scale in situ networks. Geoderma 2012, 170, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneviratne, S.I.; Corti, T.; Davin, E.L.; Hirschi, M.; Jaeger, E.B.; Lehner, I.; Orlowsky, B.; Teuling, A.J. Investigating soil moisture-climate interactions in a changing climate: A review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2010, 99, 125–161. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Dudhia, J. Coupling an advanced land surface hydrology model with the Penn State-NCAR MM5 modeling system. Part I: Model implementation and sensitivity. Mon. Weather. Rev. 2001, 129, 569–585. [Google Scholar]

- Ek, M.B.; Mitchell, K.E.; Lin, Y.; Rogers, E.; Grunmann, P.; Koren, V.; Gayno, G.; Tarpley, J.D. Implementation of Noah land surface model advances in the National Centers for Environmental Prediction operational mesoscale Eta model. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2003, 108, D22. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, G.Y.; Yang, Z.L.; Mitchell, K.E.; Chen, F.; Ek, M.B.; Barlage, M.; Kumar, A.; Manning, K.; Niyogi, D.; Rosero, E.; et al. The community Noah land surface model with 9 multi-parameterization options (Noah-MP): 1. Model description and evaluation with local-scale measurements. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2011, 116, D12109. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.L.; Niu, G.Y.; Mitchell, K.E.; Chen, F.; Ek, M.B.; Barlage, M.; Longuevergne, L.; Manning, K.; Niyogi, D.; Tewari, M.; et al. The community Noah land surface model with multiparameterization options (Noah-MP): 2. Evaluation over global river basins. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2011, 116, D12110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.H.; Li, K.; Chen, F.; Jiang, Y.; Lu, C. Assessing and improving Noah-MP land model simulations for the central Tibetan Plateau. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2015, 120, 9258–9278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Chen, F.; Gan, Y.J. Assessing uncertainties in the Noah-MP ensemble simulations of a cropland site during the Tibet Joint International Cooperation program field campaign. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2016, 121, 9576–9596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.T.; Yang, Z.L.; David, C.H.; Niu, G.-Y.; Rodell, M. Hydrological evaluation of the Noah-MP land surface model for the Mississippi River Basin. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2014, 119, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Niu, G.Y.; Xia, Y.L.; Cai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Fang, Y. A systematic evaluation of Noah-MP in simulating land-atmosphere energy, water, and carbon exchanges over the continental United States. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2017, 122, 12245–12268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuribayashi, M.; Noh, N.J.; Saitoh, T.M.; Tamagawa, I.; Wakazuki, Y.; Muraoka, H. Comparison of Snow Water Equivalent Estimated in Central Japan by High-Resolution Simulations Using Different Land-Surface Models. Meteorol. Soc. JPN. 2013, 9, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.H.; Zhang, X.N.; Niu, G.Y.; Zeng, W.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, T. Study of the Spatiotemporal Characteristics of meltwater contribution to the total runoff in the upper Changjiang river basin. Water 2017, 9, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.J.; Yang, Z.L.; Lin, P.R. Systematic hydrological evaluation of the Noah-MP land surface model over China. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2019, 36, 1171–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, C.L.; Jin, H.D.; Zhang, W.L. Lateral terrestrial water flow schemes for the Noah-MP land surface model on both natural and urban land surfaces. J. Hydrol. 2023, 620, 129410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Yang, J.T.; Zhaoye, P.H.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, G.; Wang, C. Optimization and validation of soil Frozen-Thawing parameterizations in Noah-MP. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2023, 128, e2022JD038217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, F.; Zhang, Y.; Kumar, S.V. Improved representation of vegetation soil moisture coupling enhances soil moisture data assimilation in water limited regimes: A Case Study over Texas. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR035558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J.A.; Forman, B.A.; Kumar, S.V. Soil moisture estimation in South Asia via assimilation of SMAP retrievals. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 26, 2221–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Yang, K.; He, J.; Zheng, H.; Zheng, D. Potential of mapping global soil texture type from SMAP soil moisture product: A pilot study. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4406410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechtold, M.; Modanesi, S.; Lievens, H.; Baguis, P.; Brangers, I.; Carrassi, A.; Getirana, A.; Gruber, A.; Heyvaert, Z.; Massari, C.; et al. Assimilation of Sentinel-1 Backscatter into a Land Surface Model with River Routing and Its Impact on Streamflow Simulations in Two Belgian Catchments. J. Hydrometeorol. 2023, 24, 2389–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavahi, K.; Abbaszadeh, P.; Moradkhani, H. How does precipitation data influence the land surface data assimilation for drought monitoring? Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 831, 154916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.V.; Holmes, T.R.; Bindlish, R.; de Jeu, R.; Peters-Lidard, C. Assimilation of vegetation optical depth retrievals from passive microwave radiometry. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 24, 3431–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.H.; Huang, C.L.; Hou, J.L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, G. Improving the estimation of snow depth in the Noah-MP model by combining particle filter and Bayesian model averaging. J. Hydrol. 2023, 617, 128877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.H.; Huang, C.L.; Yang, Z.L.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Gu, J. Assessing Noah-MP parameterization sensitivity and uncertainty interval across snow climates. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2020, 125, e2019JD030417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Liao, W.H.; Wang, X.M.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, W.; Wu, Z.; Hu, Z. An optimal ensemble of the Noah-MP land surface model for simulating surface heat fluxes over a typical subtropical forest in South China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 281, 107815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Miao, C.Y.; Zhang, G.; Fang, Y.-H.; Shangguan, W.; Niu, G.-Y. Global Evaluation of the Noah-MP Land Surface Model andSuggestions for Selecting Parameterization Schemes. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2022, 127, e2021JD035753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.D.; Li, X.; Shi, X.K.; Han, X.; Luo, L.; Wang, L. Dynamic downscaling of near-surface air temperature at the basin scale using WRF-a case study in the Heihe River Basin, China. Front. Earth Sci. 2012, 6, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, X.W.; Li, Z.Y.; Ma, M.; Wang, J.; Xiao, Q.; Liu, Q.; Che, T.; Chen, E.; Yan, G.; et al. Watershed Allied Telemetry Experimental Research. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2009, 114, D22103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.Y.; Yang, Z.L.; Dickinson, R.E.; Gulden, L.E.; Su, H. Development of a simple groundwater model for use in climate models and evaluation with Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment data. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2007, 112, D7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, R.E.; Shaikh, M.; Bryant, R.; Graumlich, L. Interactive canopies for a climate model. J. Clim. 1998, 11, 2823–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Huang, C.; Gu, J.; Li, H.; Hao, X.; Hou, J. Assessing snow simulation performance of typical combination schemes within Noah-MP in northern Xinjiang, China. J. Hydrol. 2020, 581, 124380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Ma, W.Q.; Yang, Z.L.; Ma, Y.; Xie, Z. Sensitivity analysis of the Noah-MP land surface model for soil hydrothermal simulations over the Tibetan Plateau. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2023, 15, e2022MS003136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Site Name | Arou | Heihe | Sidaoqiao |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latitude (N) | 38.03 | 38.83 | 42.00 |

| Longitude (E) | 100.46 | 100.48 | 101.14 |

| Elevation (m) | 3032.8 | 1560 | 873 |

| Study Period | 2016 | 2017 | 2016 |

| Climate Type | Highland Continental Climate | Temperate Continental Arid Climate | Temperate Monsoon Climate |

| Vegetation Type | Grassland | Crop | Desert |

| Soil Type | Dark Cold Calcareous Soil | Coral Sandy Soil | Mountain Shrub Meadow Soil |

| Evaluation Data | Soil Moisture | Soil Moisture | Soil Moisture |

| Physical Process | Parameterization Schemes |

|---|---|

| Soil moisture factor controlling stomatal resistance (BTR) | * 1. Noah 2. CLM 3. SSiB |

| Surface layer drag or exchange coefficient (SFC) | * 1. M-O 2. Original Noah (Chen97) |

| Frozen soil permeability (INF) | * 1. Linear effects, more permeable 2. Nonlinear effects, less permeable |

| Soil supercooled liquid water (FRZ) | * 1. No iteration 2. Koren’s iteration |

| Canopy radiation transfer (RAD) | 1. Modified two-stream 2. Two-stream applied to grid-cell (gap = 0) * 3. Two-stream applied to vegetated fraction (gap = 1-VegFrac) |

| Snow surface albedo (ALB) | * 1. BATS snow albedo 2. CLASS snow albedo |

| Partitioning precipitation into rainfall and snowfall (PCP) | * 1. Jordan (1991) 2. BATS 3. Noah 4. Use WRF microphysics output 5. Wet-bulb temperature-based |

| Lower boundary condition of soil temperature (TBOT) | 1. Zero-flux scheme * 2. Noah scheme |

| Snow or soil temperature time scheme (only layer 1) (TEMP) | * 1. Semi-implicit; flux top boundary condition 2. Full-implicit (original Noah); temperature top boundary condition 3. Same as 1, but snow cover for skin temperature calculation |

| Ground resistant to evaporation or sublimation (SRE) | * 1. Sakaguchi and Zeng, 2009 2. Sellers (1992) 3. Adjusted Sellers to decrease RSURF for wet soil 4. Option 1 for non-snow; rsurf = rsurf_snow for snow |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

You, Y.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Hao, Y.; Chen, W.; Wang, Z. Sensitivity of Soil Moisture Simulations to Noah-MP Parameterization Schemes in a Semi-Arid Inland River Basin, China. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2286. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15212286

You Y, Lu Y, Wang Y, Zhou H, Hao Y, Chen W, Wang Z. Sensitivity of Soil Moisture Simulations to Noah-MP Parameterization Schemes in a Semi-Arid Inland River Basin, China. Agriculture. 2025; 15(21):2286. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15212286

Chicago/Turabian StyleYou, Yuanhong, Yanyu Lu, Yu Wang, Houfu Zhou, Ying Hao, Weijing Chen, and Zuo Wang. 2025. "Sensitivity of Soil Moisture Simulations to Noah-MP Parameterization Schemes in a Semi-Arid Inland River Basin, China" Agriculture 15, no. 21: 2286. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15212286

APA StyleYou, Y., Lu, Y., Wang, Y., Zhou, H., Hao, Y., Chen, W., & Wang, Z. (2025). Sensitivity of Soil Moisture Simulations to Noah-MP Parameterization Schemes in a Semi-Arid Inland River Basin, China. Agriculture, 15(21), 2286. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15212286