Abstract

A pressing task is to develop a mathematical model and calculation method that most accurately describes the radiant component of heat exchange between an animal and its environment. This will help determine the optimal design parameters and temperature conditions for infrared (IR) heaters in livestock premises. The mathematical models considered describe the animal’s heat exchange with the environment during IR heating. However, they do not take into account the hidden surface temperature of the premises’ enclosing structures and their emissivity factor, or the relationship between animal thermal comfort and the IR heater surface temperature. The proposed radiant heat exchange mathematical model is applicable to diffusely absorbing and radiating isothermic surface system typical of pigsties. It takes into account the emissivity factors of all of the enclosing structures’ surfaces and determines the effective (apparent) premises temperature value tef, corresponding to the thermal comfort conditions. The IR heater surface temperature’s dependence on the emissivity of the pigsty’s enclosing structures (walls, ceiling, and floor) is given, calculated using three methods. As the emissivity of the premises’ enclosing structures decreases, the difference between the results obtained via methods 1, 2, and 3 increases significantly and reaches 50…60% at ε = 0.8. The IR heater radiating surface temperature range is defined in order to create suitable thermal conditions on premises designed for keeping 1- to 4-week-old newborn piglets depending on the enclosing structure temperature and emissivity, taking into account hidden heat exchange surfaces.

1. Introduction

Managing animals of different age grades (i.e., pigs and suckling piglets) on the same premises within the pork industry, as well as in animal transport situations, requires the adoption of specific and differentiated thermal conditions infrared (IR) heating [1,2]. Thus, the air temperature for breeding pigs must be maintained in the range of 16 °C to 20 °C, while in areas where piglets are kept, it has to be between 32 °C and 34 °C, decreasing to 24 °C by the 26-day point, the moment of their weaning. By the end of the first month, the ambient air temperature must be about 23 °C, and it can be reduced to 21 °C by the age of two months [3,4]. This presents a complex challenge, particularly in light of the demands posed by global climate change.

Creating different localized temperature zones in animal housing areas, particularly in those where young animals are kept, has always been and remains a standard solution to the task set above. Various technical means can be applied today for heating young animals in a localized manner, including heated floor panels and mats, brooders, underfloor heating, and IR heaters (lamps, panels, films, etc.) [5]. Modern heating installations in farrowing houses feature unique designs, and their heating systems make it possible to satisfy the required thermal demand for breeding pigs, newborn piglets, and post-weaning pigs simultaneously with a fair degree of accuracy.

In engineering practice, simplified techniques are commonly used for calculating local heaters. The reason for this is that animals are able to adapt their metabolic reactions to changes in various thermal environments in a certain temperature range [6]. But in the very first hours and days of their life, the biological thermoregulation mechanism of young animals is still in the formative stage. Therefore, the thermal parameters of systems affecting the level of heat flows in areas where animals are housed must be varied within a rather narrow specific range. Therefore, calculation methods for local heaters designed for young animals, particularly newborn piglets, must account for the functional interrelations among all elements of the biotechnical system to the fullest extent possible [4,5,7].

1.1. Current Research Analysis

Boltyanska [8] studied a great number of possible heating system options for pig-breeding farms. She reported statistical values for the share of electricity and fuel costs associated with heat provision on pig-breeding premises as a part of the total energy and fuel consumption costs. She also defined the major factors that have to be taken into account while selecting heating and ventilation systems for a pig-breeding farm. She gave an analysis of the major advantages and drawbacks of infrared heating systems, heated floors, and electric heat exchangers.

Vasdal et al. [4,9] carried out a series of experimental studies on the thermoregulatory behavior of newborn (one-day-old) suckling piglets while being heated with the help of infrared heater lamps in the temperature range of 26 °C to 42 °C. In addition, they observed lying poses and a huddling-together tendency for 1- to 3-week-old piglets depending on the temperature deviation in the ranges of ±4 °C and ±8 °C from standard temperature values for the corresponding ages (34 °C, 27 °C, and 25 °C). Experimental studies of the influence of various local devices designed for heating piglets on their weight gain and survival indicators have been performed. The values of temperature in the kennel and absolute and average daily liveweight gain were compared for three local heating system types: electrically heated floors, infrared heater lamps, and the combination of the first two methods. The best indicators were observed for a combined local heating system with infrared heater lamps and heated floors [10,11]. Komarov and Fain [12] calculated the energy-related parameters for local electric heating and performed a comparative economic assessment for local heating appliances per year with and without the account of liveweight gain, for suckling piglets.

The basic principles for analytical evaluation of the temperature felt by animals while being heated with the use of infrared heater lamps, as well as those for their body surface, have been considered. Conditions of heat emission by animals exposed to external heat sources in standing and lying positions have been studied. A thermal balance calculation scheme has been presented with a piglet as an example. Provisions for determining thermal comfort conditions have been defined for young animals while using radiant heaters, along with the necessary and sufficient conditions that have to be applied for comparing various heating installations in the process of selecting a particular animal heating method [13,14]. A two-dimensional thermophysical model of piglet heat exchange in combined heating conditions for a floor-mounted environment has been presented, forming the basis for developing a mathematical model making it possible to calculate the thermal condition parameters in areas for heating piglets [15]. An analysis of studies on piglets’ thermal state and local heating is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of piglet thermal state research and the effectiveness of local heating methods.

1.2. Problem Analysis, Research Goal, and Objectives

Current research analysis (see Table 1) reveals significant limitations in existing mathematical models of piglet heat exchange during IR heating. These models fail to account for the hidden surface temperature of the premises’ enclosing structures and their emissivity factor. Furthermore, these studies overlook the relationship between piglets’ thermal comfort, the IR heater’s surface temperature, and the effective temperature in the premises. In all the reviewed studies (except [18,20]), radiant heat transfer is calculated primarily using the Stefan–Boltzmann equation in its most general form, ignoring the effects of temperature and the emissivity of the premises’ enclosing structures. In this model, the radiant component of heat transfer is calculated similarly to the convective heat transfer component [20]. The extended Effective Environment Temperature (EET) index is used, which takes into account convection, radiation, and additionally thermal conductivity and piglet mass. Radiative heat transfer calculations are also presented in a simplified form [18].

The proposed calculation model allows us to describe the dependence of piglets’ thermal state on the thermophysical parameters set (radiation temperature and enclosing structure materials’ emissivity factor, air temperature). The supplemented calculation model describes the animal radiant heat exchange in a system of diffusely absorbing and radiating isothermic bodies, typical for pigsties. This model will provide a more comprehensive description of the heat exchange processes that occur during IR heating of piglets. The expansion of existing radiant heat exchange models to include the effects of diffusely absorbing and radiating bodies in a closed system will help substantiate the design and thermal parameters, as well as the operating modes, of IR heaters.

2. Materials and Methods

Thermal sensation for a certain animal activity level is a function of the organism’s thermal balance. Thermal comfort is the heat exchange balance in conditions of minimum physiological activity, that is, the state when all of the metabolic heat is dissipated into the environment without considerable negative physiological reactions (such as shivering, high respiratory rate, and so on). Suitable thermal conditions are characterized by an effective temperature value tef that is optimal with regard to the physiological demand of the organism to achieve the maximum productivity (survival ability) for a reasonable feed consumption rate (economically optimal productivity) under the stipulation that animals are not exposed to either overheating or excessive cold in areas where they are located. The temperature value tap corresponds to that of an idealized homogeneous environment having a uniform temperature of both the system shell and gaseous medium, provided that the animal organism’s heat exchange in this idealized environment is identical to that in real conditions [7,14].

A biotechnical system is a complex of technical equipment interacting with the animal organism and having a certain impact on the thermal conditions within the environment area under consideration.

2.1. Comparative Analysis of Calculation Methods for Young Animal Heating with the Use of Radiant Heater Panels

Early age piglets (up to one month old) are most sensitive to the ambient temperature variations [24,25]. Animals’ thermal balance is strongly influenced by radiant heat energy in the process of heat exchange with the enclosing structures of the premises where they are kept. Therefore, it is essential to create an artificial environment with thermophysical parameters in a certain value range to ensure suitable conditions for managing animals [26,27]. Selecting mathematical models that most adequately describe all physical links and their interaction within the “animal–environment” biotechnical system makes it possible to define the infrared heater’s parameters and operation modes to provide the required thermal conditions in areas where young animals have to be kept.

An animal’s heat emission rate depends on the temperature of the enclosing structure surfaces as well as on its position and size. Suitable environments can only be implemented in a system where the thermal equilibrium is achieved and where there is no organism stress in the process of its thermoregulation [1,28].

One universally accepted mathematical representation of such conditions for industrial and residential premises has the following form [27]:

where Qanr-con is aggregate radiant, convective, and conductive animal heat emission into the environment (W); Fr is animal surface area (m2) participating in radiant heat transfer; C is reduced radiation coefficient (4.65 W·m−2·K−4) [29]; φi is angular coefficient for irradiance from the elementary animal surface towards the i-th surface; bi is a corrective factor; Fcon is the animal surface area (m2) participating in convective thermal transfer; αcon is the convective heat transfer rate (W∙m−2∙K−1); Fcond is the animal surface area (m2) participating in conductive heat transfer; Kan-f is the heat transfer rate from the animal body surface towards the floor (W∙m−2∙K−1); ti is the temperature of the i-th surface (°C); tan, ta, and tf are the temperatures of the animal skin, ambient air, and floor (°C), respectively; and U is the heat exchange rate in the area of the animal’s major heat exchange (W) [26,27].

Evaporative heat exchange in the piglet’s heat balance is of significant importance under hyperthermia (overheating) conditions. Under thermal conditions close to comfortable, the animal’s heart rate and pulse are normal, so the vaporization latent heat during breathing is not taken into account (it can be neglected).

The average specific value of the heat emission from the elementary animal surface area equals

where Fan is the animal surface area (m2).

It follows from relationships (1) and (2) that

where qr is a specific value or radiant heat emission from the animal’s elementary surface area (W/m2), Qsen.min…Qsen.max is the sensible heat emission Qsen range for animals of a particular species and age in thermal comfort conditions in the areas of their major heat exchange U (W).

If animals are located close to heated or cooled surfaces, the rate of the radiant heat exchange over the body surface area most sensitive to radiation will be a determining factor.

The radiant heat exchange equation for heat emission from the animal’s elementary surface area in a system of radiating surfaces has the following form [29]:

where φi is the angular coefficient of irradiance from the animal’s elementary surface towards the i-th surface, ban-i = 0.81 + 0.01τmed.i is the temperature corrective factor, τcpi = 0.5 (tan + ti), ti is the temperature of the i-surface (°C), ban-es = 0.81 + 0.01τmed.es is the temperature corrective factor (°C), τmed.es = 0.5 (tan + tes) (°C), and tes is the average temperature of the premises’ enclosing structure (°C).

Values of sensible heat emission Qsen and those of heat production for a particular animal Qhp as well as surface temperature tan have to correspond to the major heat exchange area U [1,28].

The value of specific heat flow qr, transferred by the premises enclosure to the elementary animal surface is defined from the following formula [22,29,30]:

where Cred-i = С0 (1/εan + 1/εi − 1) and Cred = С0 (1/εan + 1/εs.sh − 1) are reduced radiation rates; С0 is the blackbody coefficient (W∙m−2∙K−4); εan, εi, and εs.sh are the emissivity factors of the animal surface, i-th surface, and system shell, respectively; Tan is the animal surface temperature (K); Ti is the temperature of the i-surface (K); and Ts.sh is the temperature of the system shell (K).

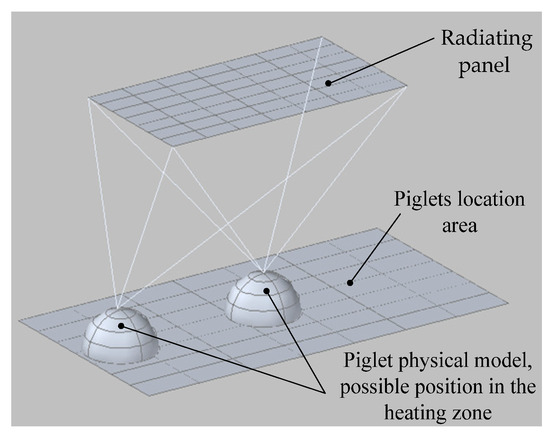

Let us consider the generalized model for animal heat exchange with a radiator panel (see Figure 1). Based on expression (4), the radiant heat exchange equation will be written for this case as follows:

where ban-rp and ban-s.sh are temperature coefficients, trp is the temperature of the IR radiator panel surface (°C), and φrp is the angular coefficient for irradiance from the animal elementary surface towards the radiator panel surface.

Figure 1.

Model for animal heat exchange with radiating panel.

Formula (6) describes the heat exchange for an elementary surface area on the animal’s surface with a radiating panel. This expression is based on the literature [29] (Figure 1).

Based on relationship (5), we can write the following radiant heat exchange equation for the variant under consideration:

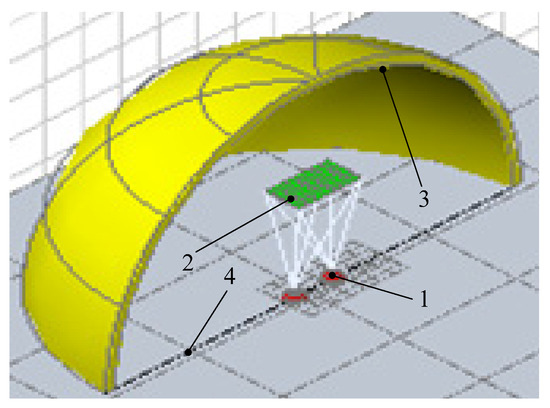

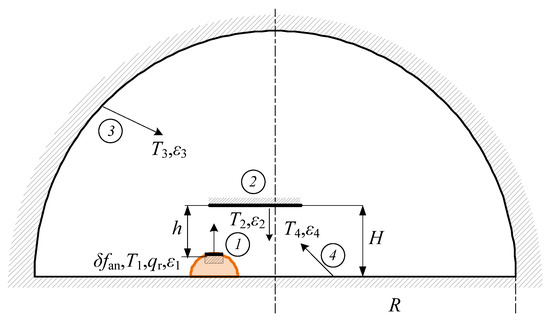

The radiant heat exchange model based on relationships (4) to (7) is applicable only to the radiant heat transfer flows for “apparent” surfaces, but it does not take into account the diffuse component of radiant heat flux from hidden surfaces that is typical for diffusely absorbing and radiating bodies. Therefore, the above radiant heat exchange model has to be extended to involve diffusely absorbing and radiating isothermic bodies in the system, which will make it possible to obtain a much more complete description of the thermophysical processes (see Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Heat exchange physical model in the system of diffusely absorbing and radiating isothermic surfaces: 1—animal body elementary surface; 2—radiating panel; 3—enclosing structure surface; 4—floor surface.

Figure 3.

Thermophysical model for radiant heat exchange between various surfaces: 1—elementary animal surface area δfan, T1 (t1) is surface temperature, qr is total radiation rate from elementary surface, ε1 is its emissivity factor; 2—radiating panel, T2 (trp) is its surface temperature, ε2 is its emissivity factor; 3—premises’ enclosing structure surface (ceiling, walls), T3 (t3) is enclosure temperature, ε3 is enclosure emissivity factor; 4—floor surface, T4 (t4) is floor temperature, ε4 is floor emissivity factor, H is radiator suspension height, h is radiator suspension height above the animal surface δfan, R is premises’ generalized dimension.

An animal’s thermal comfort depends substantially on the radiant heat component in its entire thermal balance with the environment. In this context, radiant heat exchange of animals located close to heated or cooled surfaces (particularly, the radiant heat balance of the animal body surface area most unfavorably located in relation to the radiation sources) shall be regarded as a decisive factor. For any biological system, there exist the maximum permitted values of the radiant heat exchange rate between an organism’s surface and that of a radiation source [31,32]. That is why it is necessary to control the intensity of the radiant heat exchange in areas where animals are managed wherever infrared heating has to be applied. In this regard, an essential task is to study technical environments having their thermophysical parameters in accordance with expression (3) to set the borders of the animals’ major heat exchange area. This refers to the equilibrium between the heat production and heat emission by an animal organism in the process of its interaction with the radiating panel surface in areas where it is located.

The thermal exchange physical–mathematical problem for radiations in a system of isolated gray surfaces can be considered as a complete one provided that the temperature values for some of these surfaces are defined while values of thermal flows are known for the other surfaces. The reference condition is either a specified animal thermal state or that of its model representation, i.e., the effective temperature value and those of the following parameters corresponding to this value: sensible heat emissions Qsen, model surface temperature tsm, and surface area fan.

The heat exchange model for an isolated thermodynamic system composed of N finite-dimensional surfaces (see Figure 3) has to be built with consideration of the following assumptions [33]: each surface is isothermic, each system surface is gray, radiation reflected from surfaces is distributed diffusely in space, radiation emitted by each surface is distributed diffusely in semi-space, effective radiation flow surface density is uniform in all points of each system surface, and angular coefficients do not depend on the value and surface distribution of radiation flows. We consider the case where the temperatures on all N system surfaces are given and it is necessary to determine the corresponding heat fluxes of the resulting radiation.

For an arbitrary i-surface, total radiation flow density can be defined for the specified values of system surface temperatures based on research [34] on the expression:

where δij is the Kronecker index, δij = 1 for I = j, δij = 0 for I ≠ j, and Qi is the total radiation flow from surface Fi (W).

The coefficients ψij included in Equation (8) are determined based on the inverse matrix calculation ψ = χ−1 [34]:

where φij is the angular coefficient of irradiance from surface i to surface j.

Expression 8 is the general equation for calculating the IR radiating panel surface temperature. The coefficients ψij included in Equation (8) are determined using expression (9). Expression (9) includes the angular coefficients φij.

In the model under consideration, angular coefficients can be calculated on the basis of the reciprocity and congruence theorem [33,35].

The following definition and assumptions were introduced: the premises’ generalized size will be expressed with use of the parameter R = (ΣFst/3π)0.5 where ΣFst is the aggregate surface area of the walls, ceiling, and floor; linear dimensions of surfaces 1 and 2 are substantially smaller compared to those of surfaces 3 and 4 of the system shell; and the shield effect on the IR flows between the system shell surfaces can be neglected (see Figure 3).

Analytical calculations can be substantially simplified by considering an isolated system composed of only N = 4 finite-size gray surfaces (floor, walls–ceiling, animal, radiant IR heater). Nevertheless, such a model can be regarded as a generalizing structure for livestock premises that vary widely in their geometry and size (see Figure 3). Increasing the number of surfaces (5 or more) significantly complicates the calculations. However, this has virtually no effect on the accuracy of the obtained results, such as the IR radiating panel temperature trp.

The angular radiation coefficients φij between the interacting surfaces are expressed by the following relations (10):

where X = a/c, Y = b/c, a and b are dimensions of rectangular radiating surface (m), c is distance between the radiating surface end-face and the animal’s elementary surface δfan (m), δfan is the elementary animal surface area, F31 is the “apparent” surface F3 having elementary area δfan, H is the radiator suspension height (m), h is the radiator suspension height above the animal elementary surface δfan (m).

The above relationships serve as a basis for determining the required surface temperature of the IR radiating panel and thermal energy emission. They can also be applied to perform a comparative evaluation of the calculation results for the methods under consideration. Further on, we will assume that expressions (5), (6), and (8) represent calculation methods 1 to 3, respectively (see Table 2).

Table 2.

A comparison of the calculation methods (calculation models) for radiant heat exchange between an animal and the environment.

2.2. Piglet Heat Exchange Physical Model

The physical model for piglet heat exchange with an environment comprises the relationships presented below. Piglet body surface area and weight (age) correlate in accordance with the following experimental expression:

where fan is the animal surface area (m2), m is the animal weight (kg), and rd is a corrective factor (rd = 0.0998 [36], rd = 0.09 [18], rd = 0.092 [37]). According to other sources, fan = 0.097m0.633 [38].

Piglet geometric parameters are as follows:

where d is chest girth (m) and l is barrel length (m) [36].

In regulatory documents, as well as in some zoohygienic study reports, the values of sensible heat Qsen for animals in standing posture are specified as a function of a limited number of parameters [7]. In accordance with the statement above, the piglet thermophysical calculation model has to be based on the standardized data for heat production Qst and sensible heat emission into the environment Qsen. For the equilibrium state Qst = Qsen, Qsen depends on the animal weight (age) and effective tef in premises. Various representations of this dependence have been reported in the literature [18]. One of such representations is based on the following power polynomial approximation of initial data [28]:

where kt (tef) is the conversion factor for various effective temperature values in premises and tef is the effective temperature in premises (°C).

2.3. Mathematical Description of the Piglet Heat Exchange Model

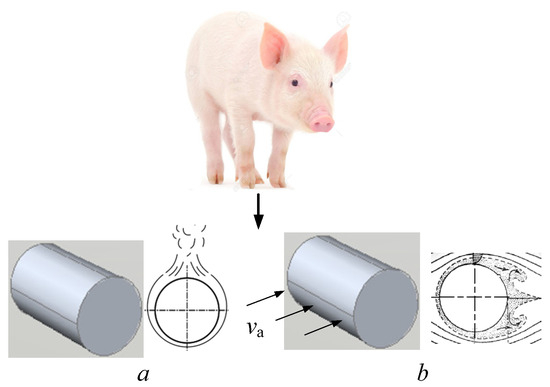

Modeling animal heat exchange with the environment is performed with the help of analogies in which the real animal body geometric shape is normally represented in the form of a cylinder, a solid sphere, or another form [39,40] invariant with respect to the variables fan (m), Qsen (m,tef), l (m), and d (m) integrated into the thermophysical model.

The mathematical description of the piglet model heat exchange (Figure 4) in a homogeneous environment system with temperature tef can be represented by the following equation with consideration of the deduced expressions and criterial relationships determining convective and radiant heat emission conditions:

where Qsen is the piglet’s sensible heat emission (W), fan is the piglet model’s surface area (m2), m is the piglet weight (kg), τ is the piglet age (days), αcon is the average coefficient of convective heat emission from the piglet body surface (W·m−2·°K−1), λ is the air’s thermal conductivity (W·m−1·°K−1), tsm is the piglet physical model’s surface temperature (°C), φen is the rate of mutual irradiance between the organism and the external enclosure, εred is the reduced emissivity factor for the animal surface and the enclosure’s internal surfaces, C0 is the blackbody coefficient (W·m−2·K−4), Nu is the Nusselt number.

Figure 4.

Physical model for piglet heat exchange with the environment: (a) natural convection, (b) forced convection, νan—air flow velocity (air speed in the area where piglets are kept).

Depending on the air medium circulation mode in premises, either natural or forced convection heat transfer conditions may occur in areas where animals are managed. These can be represented by the following criterial equations [41,42]:

- -

- For natural convection mode,

- -

- For forced convection mode (laminar air motion 2 × 103 ≤ Re ≤ 1 × 104),

where Re, Gr, and Pr are Reynolds, Grashof, and Prandtl numbers, respectively; εt = (Prliq/Prw)0.25 is corrective value that takes the dependence of the air’s physical properties on temperature into account; Prliq corresponds to a certain air temperature; the PrW value has to correspond to a particular medium and given wall temperature; εφ is a corrective value taking account of incident flow angle (angle φ between the air velocity vector and cylinder axis); either expression εφ = 1 − 0.54cos2φ or εφ = (sinφ)0.5 can be applied to calculate εφ.

The values of heat emission from the animal surface depend on the particular medium’s thermal properties and on air flow velocity:

where tr is the radiant temperature in the premises (area-averaged temperature of internal surfaces) (°C), tf is the floor temperature (°C), ta is the air temperature (°C), νa is the air flow velocity (m/s), and Qinput is heat gain from other sources (W).

Thermal conditions will correspond to actual values of effective temperature tef when equation Qsen (m,tef) = Qloss (tr,tf,ta,νa,Qinput) is valid, in the thermodynamic equilibrium state.

The thermodynamic state of a real animal as well as that of its physical model can be described by a certain complex of parameters.

For a real animal,

where Utan is the temperature field distribution over the animal skin surface (°C).

For an animal model,

where Qhpm is heat production (W) and Qsenm is model heat loss (W).

For Qhp = Qsen = Qhpm = Qsenm, the real animal’s thermal state can be expressed with the use of model temperature parameters tsm and tef for various external thermal states of the environment.

3. Results and Discussion

The general formulation of the calculation problem for heating areas intended for managing young animals is defined by the system of equations for total heat exchange in premises and by the thermal comfort conditions. The radiant temperature situation in premises is governed by the following major surface groups: heating, cooling, and neutral surfaces. The radiant heat transfer flows in premises have to be calculated with the consideration of the enclosure’s internal surface temperature. In this case, the mathematical description for calculating the heating surface areas and temperatures may be substantially simplified. One specific feature of composing relationships for the above different surface groups relates to defining the values of coefficients for irradiance between the interacting surfaces, values of averaged coefficients for the reduced radiation, effective radiation flows, and other process parameters.

Solutions for complete systems composed of a number of equations may be rather complicated. That is why we will apply simplified calculation procedures. For this purpose, we will determine the temperatures of both internal enclosures and external ones facing the interior space of the premises. Therefore, either the temperature or the surface area of the heating IR radiator will be a target value. Such an approach to solving this problem enables us to replace the entire heat exchange equation system for premises with just one single equation.

A radiation field in a system of arbitrarily assigned configuration of surfaces having various sizes and separated from each other by a diathermic medium represents the function of temperature fields and optical constants on the system borders. A local system configuration is typical. It is normally an area within the entire system comprising an infrared radiation source (see Figure 2) [43]. Livestock-dedicated premises are characterized by a rather wide size range and configuration variety (from small farms to large livestock complexes). Therefore, there is a reason to reduce this diversity of objects’ geometric shapes to one single generalized parameter R representing the size of particular premises (see Figure 3).

With this background, the problem has to be set as follows:

- -

- Determining radiating surface temperature (or surface area) in an isolated system composed of diffusely radiating bodies; in addition, temperature and total radiation from the elementary animal surface δfan have to be maintained in the ranges t1⊂ (t1min…t1max) and qr⊂ (qrmin…qrmax);

- -

- Defining variation intervals for calculated parameter values depending on the corresponding variables: enclosure and floor temperatures, emissivity factor of surfaces;

- -

- Evaluating interacting bodies’ emissivity factor;

- -

- Setting limiting conditions for calculation models’ validity.

3.1. Calculating IR Radiating Panel Surface Temperature, Accounting for Enclosing Surface Emissivity Factor and Premises’ Size

The following design and technological parameters of thermophysical systems were selected as the initial data with respect to technological design standards for farrowing houses [44]:

- -

- The radiating panel’s dimensions are 0.5 m wide and 1 m long, and its suspension height h over the surface δfan is 1 m;

- -

- The total radiation rate from the elementary surface is δf qr = 18 W/m2, for body surface temperature t1 = 33 °C;

- -

- The emissivity factor of the radiating system varies in the ranges of εi = 0.80 to 0.96, i = 1 to 4, and temperatures of thermally homogeneous surfaces 3 and 4 range within the limits of t3 = 10 °C to 25 °C and t4 = 5 °C to 25 °C, respectively.

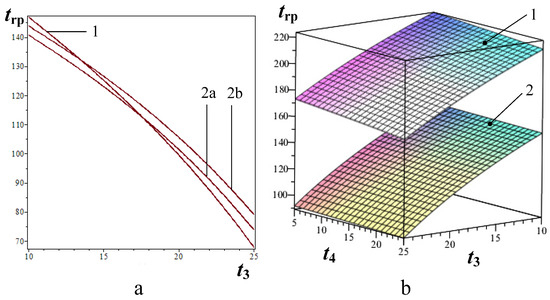

The dependences of radiating panel surface temperature trp on the temperature of the enclosure t3 (wall and ceiling temperature) calculated with the application of the first and the second methods do not practically differ from one another, and the corresponding enclosure temperature values’ variation does not exceed 10% for the specified temperature range (see Figure 5a). For surfaces 1 and 2, method 3 has to be applied within the trp variation range limited by the interval ε = ε1 = ε2 = ε3 = ε4 = 0.80 to 0.96 (see Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Dependence of panel surface temperature trp (°C) on the temperature of the enclosure (walls and ceiling) surface t3 in premises (а): 1—for calculation method 1; 2a and 2b—for calculation method 2 (ε3 = 0.96 and ε3 = 0.80, respectively). The value range for panel surface temperature trp (°C) depending on t3 (temperature of ceiling and walls) and t4 (floor temperature) (b): 1—for ε1 = ε2 = ε3 = ε4 = 0.80; 2—for ε1 = ε2 = ε3 = ε4 = 0.96.

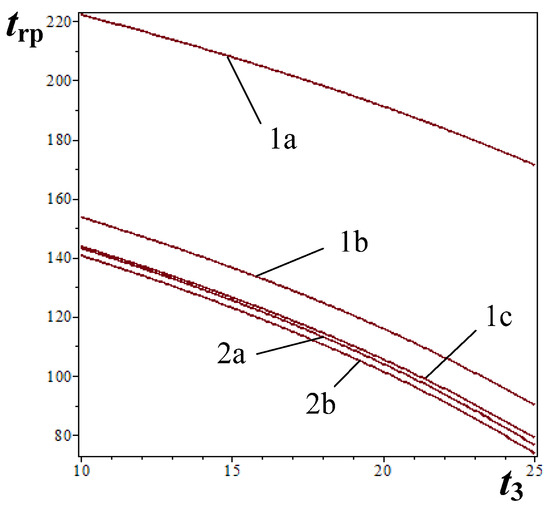

For total radiation qr from animal body elementary surface δfan and its temperature t1, specified in mathematical models, the values of the radiating panel surface temperature calculated by methods 2 and 3 differ significantly (the difference amounts to 50% to 60%) as a result of the effect of reflected diffused thermal flows and interacting surfaces’ emissivity factor (see Figure 6). Given that emissivity factor values of the system shell are close to those of the absolute black body (ε ≈ 1), temperature values trp calculated using methods 2 and 3 are in close agreement (3% to 5%) (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Dependence of radiating panel surface temperature trp (°C) on the temperature of the enclosure t3: 1a and 1b—in accordance with method 3 for the following values of parameters involved in the calculation model: ε1 = ε2 = ε3 = ε4 = 0.80 (t4 = 10 °C, R = 15 m) and ε1 = ε2 = ε3 = ε4 = 0.96, respectively; curves 2a and 2b apply to method 2 for ε3 = 0.96 and ε3 = 0.80, respectively: curve 1с applies to method 3 for t4 = 20 °C, R = 15 m, and ε1 = ε2 = ε3 = ε4 → 1.

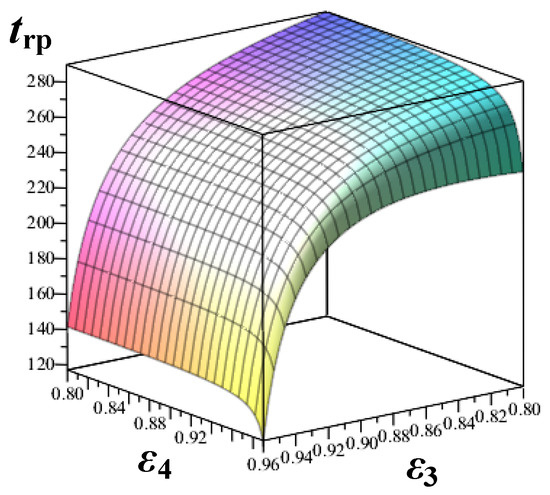

The calculated dependence of radiating panel surface temperature trp on the system shell emissivity in accordance with relationship (7) (see Figure 7) indicated the essential influence of the system shell emissivity factor on the thermal environment in areas where animals are located.

Figure 7.

Dependence of radiating panel surface temperature trp on the system shell emissivity factor: ε3 is the enclosure emissivity factor (that of ceiling and walls); ε4 is the floor emissivity factor.

As ε decreases to values ≤ 0.9, a significant portion of the radiant heat fluxes reflected from hidden surfaces interacts with the animal’s body. Accordingly, as ε increases, the magnitude of the reflected heat fluxes decreases significantly, and the influence of hidden surfaces is reduced by a factor of several. Therefore, at ε ≥ 0.95, traditional methods for calculating radiant heat exchange between the animal and the environment can be used (Equations (4)–(7)).

A relationship between the IR heating panel temperature (trp) and the emissivity of the enclosing structures has been established. A decrease in the emissivity of the enclosing structures (εi ≤ 0.9) significantly influences the increase in trp. For ε ≈ 1, the trp values calculated using the proposed methodology and established methods are in close agreement, with a difference of ≤5% (see Figure 7).

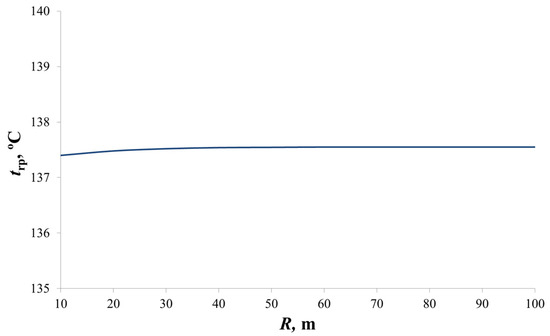

In order to ensure the required thermal conditions and irradiation levels in heated zones, one has to take into account the type and configuration of particular premises. The calculations carried out have shown that for any fixed emissivity factor values of the system surfaces integrated in calculation model (7) and their temperatures (for example, for ε1 = ε2 = ε3 = ε4 = 0.8, t3 = 15 °C, and t4 = 10 °C), the premises’ size and configuration described by generalized parameter R do not practically have an effect on radiating panel temperature trp (see Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Dependence of radiating panel surface temperature trp on parameter R.

As shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3, the actual configuration of the livestock premises is replaced by a hemisphere inscribed in these premises. The projection of the premises’ enclosing structures onto the hemisphere does not depend on the premises’ dimensions. The dimensions and configuration of the premises, characterized by the generalized parameter R, do not significantly affect the IR heater surface temperature trp, as shown in Figure 8. It follows from this that the proposed mathematical model is applicable to livestock premises of virtually any configuration and size.

Calculations for the surface temperature were performed for a particular radiating panel in a system of diffusely absorbing and radiating isothermic surfaces having the given geometry and specific value of total radiation flow from the elementary surface at a certain specified point.

3.2. Calculating IR Radiating Panel Surface Temperature for Piglets of Various Ages, Accounting for Premises’ Enclosing Structure Temperature

In engineering practice, the first two calculation methods for evaluating thermal comfort normally prevail. This is explained by the fact that animals are capable of adapting their metabolic reactions to the thermal environment change, within a certain range. Calculations performed with the use of such models can determine the thermophysical characteristics of biotechnical systems, within their permissible borders, with accuracy sufficient to define optimal parameters of IR radiators.

A vast amount of experimental data related to the maintenance conditions for piglets belonging to various age groups has been accumulated, particularly data concerning arranging location areas having specific thermal characteristics [21,22,45,46,47].

The role of an integrated parameter representing various thermal environments is played by the effective (apparent) temperature in premises, i.e., a complex parameter depending on the ambient air temperature and velocity as well as on the premises’ radiant temperature.

Within the entire range of possible effective temperature values, there exist intervals ensuring the maximum productivity for a certain animal group corresponding to the lowest possible specific reduced production cost. Such value ranges are defined by biologists and have to be treated as the standard ones for all animal species.

It is clear from the analysis of studies in which data and recommendations were reported concerning temperature conditions’ control that the optimal air temperatures may vary in a rather wide range according to a number of research results. It was reported in works [7,48] that the optimal air temperature values in areas where piglets have to be kept are in the following ranges: 26 °C to 30 °C, 24 °C to 26 °C, and 22 °C to 24 °C for the second, third, and fourth week, respectively. According to other sources, air temperature in areas where piglets are housed has to be maintained in the following intervals: 32 °C to 34 °C, 26 °C to 28 °C, 24 °C to 26 °C, 22 °C to 24 °C, and 20 °C to 22 °C, during the second, third, fourth, and fifth week, respectively [4,9].

In addition to the microclimate requirements mentioned above, it is essential to implement the heating system operation modes in correspondence with particular animal group biological rhythms, i.e., with the consideration of their cyclic metabolism intensity variations governed by natural daily alternation between the activity and rest periods. According to some sources, piglets’ metabolism reduces by 15% during their rest time.

These air temperature values as well as the experimentally obtained data on animal metabolism variations were integrated into the initial calculation model as the input parameters contributing to the calculation results. Selecting actual values of variables included in expressions (13) and (14) depends on the specific features of animal production and management technologies focused on achieving the maximum technological effect [37].

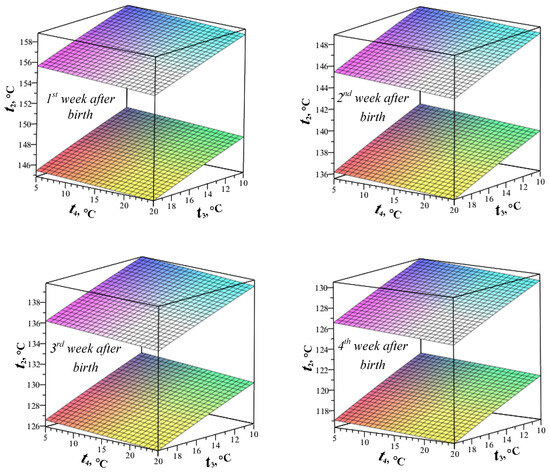

These calculations determined the dependence of the IR panel surface temperature (t2) on the temperature of the enclosing structures (ceiling, walls, and floor), which is required to ensure a comfortable thermal state for piglets of different ages at a given effective temperature tef in the heating zone (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Value range for panel surface temperature t2 depending on temperatures t3 (ceiling, walls) and t4 (floor) corresponding to the thermal comfort state in heating areas for piglets aged from 1 to 4 weeks.

The optimal effective temperature was established for different age groups: 30–26 °C for 1–7 days, 26–24 °C for 8–14 days, 24–22 °C for 15–21 days, and 22–20 °C for 22–28-day-old piglets [44]. These ranges are maintained by adjusting the infrared panel temperature (trp) in response to the surface temperatures and emissivity of the enclosure structures.

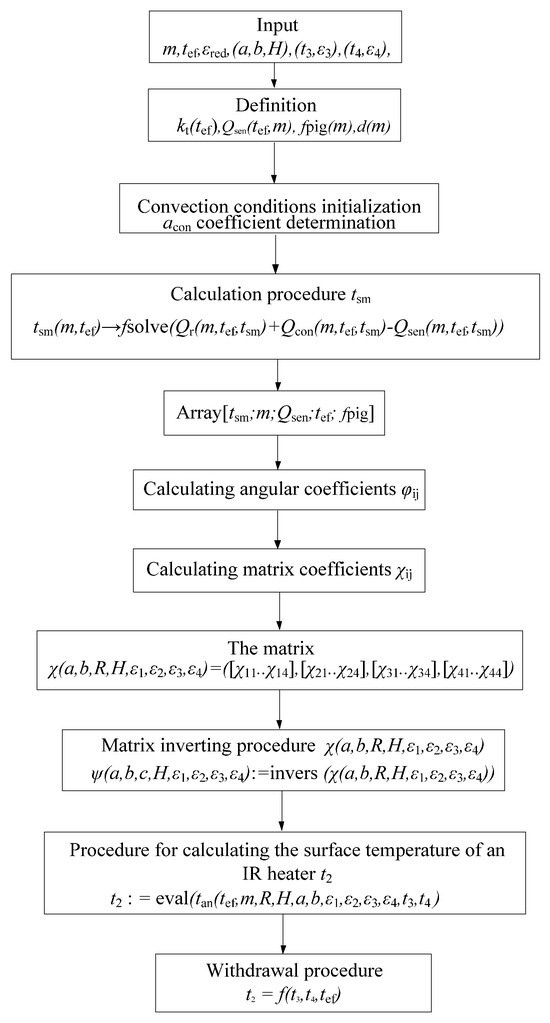

Figure 10 shows the algorithm for calculating the surface temperature of the radiating panel t2, which creates comfortable conditions in the piglet placement area with a given effective temperature tef.

Figure 10.

Algorithm for calculating the radiating panel surface temperature.

The objective of computational blocks 1–5 is to determine the surface temperature of the physical piglet model (tsm) as a function of body mass (age) and the effective temperature (tef). The objective of computational blocks 6–10 is to determine the radiating panel surface temperature required to establish comfortable conditions in the piglet occupancy zone.

The angular radiation coefficients and the IR heater surface temperature calculations were carried out using the Maple 17 software package. The primary objective is to determine the infrared radiating panel surface temperature required to maintain a comfortable effective temperature in the piglet occupancy zone. The temperature and emissivity of the enclosing structures (walls, ceiling, and floor) have a significant influence on the animals. This influence can be mitigated through the implementation of a radiant heating system utilizing panel-type IR heaters.

4. Conclusions

A mathematical model and a methodology for calculating the radiant heat exchange of young animals (using piglets as an example) in a closed system of diffusely absorbing and radiating isothermic surfaces have been developed. The model accounts for the emissivity (εi) of the enclosing structures and the interrelationship between the effective temperature tef inside the premises and the surface temperature of the animal model (tsm).

The relationship between the infrared heating panel temperature (trp) and the emissivity of the enclosing structures has been established. A decrease in the emissivity of these surfaces (εi ≤ 0.9) significantly leads to an increase in trp. For ε ≈ 1, the trp values calculated using the proposed methodology are in close agreement with those obtained by established methods (difference ≤ 5%).

It has been demonstrated that the size and configuration of the premises (generalized by the parameter R) do not significantly affect the required trp. Thus, the proposed mathematical model is applicable to livestock premises of virtually any configuration and size.

The required range for the infrared panel surface temperature (t2) has been determined based on the radiant temperature and emissivity of the enclosing structures for four age groups of piglets (from 1 to 4 weeks) at specified effective temperature (tef) values.

Applying the developed methodology allows for rationalization of the parameters, operational modes, and infrared heater design. This ensures the required thermal regime, which contributes to improved animal survival and weight gain while reducing energy consumption.

Promising research directions include the experimental verification of the theoretical results, development of a prototype infrared heating panel with a uniform heat flux, integration of localized heating into an automatic climate control system, and study of animal behavioral responses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.T. and A.K. (Aleksei Khimenko); methodology, A.K. (Aleksei Kuzmichev), D.T. and A.K. (Aleksey Khimenko); validation, D.T. and A.K. (Aleksei Khimenko); formal analysis, A.K. (Aleksei Khimenko) and D.B.; investigation, D.T., A.K. (Aleksei Khimenko) and A.K. (Aleksey Kuzmichev); resources, A.K. (Aleksei Khimenko); data curation, D.T. and A.K. (Aleksei Khimenko); writing—original draft preparation, D.T. and A.K. (Aleksei Khimenko); writing—review and editing, A.K. (Aleksei Khimenko), D.T. and D.B.; visualization, A.K. (Aleksei Khimenko) and D.T.; supervision, D.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kuzmichev, A.V.; Tikhomirov, D.A. Thermal Conditions in the Areas of Piglets Placement. Electr. Technol. Electr. Equip. APK 2019, 3, 17–22. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Machado, N.A.F.; Martin, J.E.; Barbosa-Filho, J.A.D.; Dias, C.T.S.; Pinheiro, D.G.; de Oliveira, K.P.L.; Souza-Junior, J.B.F. Identification of Trailer Heat Zones and Associated Heat Stress in Weaner Pigs Transported by Road in Tropical Climates. J. Therm. Biol. 2021, 97, 102882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikhomirov, D.; Khimenko, A.; Kuzmichev, A.; Bolshev, V.; Samarin, G.; Ignatkin, I. Local Heating through the Application of a Thermoelectric Heat Pump for Prenursery Pigs. Agriculture 2023, 13, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasdal, G.; Wheeler, E.F.; Bøe, K.E. Effect of Infrared Temperature on Thermoregulatory Behaviour in Suckling Piglets. Animal 2009, 3, 1449–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trunov, S.S.; Rastimeshin, S.A. Requirements for the Thermal Condition of Livestock Buildings with Young Animals and Prerequisites for the Use of Local Heating. Bull. VIESH 2017, 2, 76–82. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Brandl, T.M.; Hayes, M.D.; Rohrer, G.A.; Eigenberg, R.A. Thermal Comfort Evaluation of Three Genetic Lines of Nursery Pigs Using Thermal Images. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 225, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastimeshin, S.A. Local Heating of Young Animals (Theory and Technical Means); Agropromizdat: Moscow, Russia, 1991. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Boltyanska, N. Justification of Choice of Heating System for Pigsty. Teka Comm. Mot. Power Ind. Agric. 2018, 18, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Vasdal, G.; Møgedal, I.; Bøe, K.E.; Kirkden, R.; Andersen, I.L. Piglet Preference for Infrared Temperature and Flooring. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2010, 122, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubina, M.V. Local Heating of Suckling Piglets with Heating Floors and Infrared Lamps. Curr. Issues Intensive Dev. Anim. Husb. 2021, 24-2, 212–218. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Medvedeva, Z.V.; Burtseva, S.V.; Klimenok, I.I. Influence of Local Heating Methods on the Growth Indicators and Safety of Piglets. Bull. Altai State Agric. Univ. 2021, 4, 87–92. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Komarov, R.S.; Fine, V.B. Comparative Economic Evaluation of Local Electric Heating Various Technical Means Suckling Piglets. Bull. Chelyabinsk State Agro-Eng. Acad. 2013, 63, 56–61. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Tikhomirov, D.A.; Rastimeshin, S.A.; Trunov, S.S.; Ukhanova, V.Y.; Kuzmichev, A. V Mathematical Modelling and Energy Accounting of Heaters for Growing Stock. Helix 2020, 10, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmichev, A.V. Determination and Evaluation of Thermal Conditions in the Young Animals Heating Zones by Infrared Heaters. Bull. VIESH 2017, 4, 26–31. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Prishchepov, M.A.; Selyuk, Y.N.; Prishchepova, E.M.; Rutkovsky, I.G. Mathematical Modeling of Heat Transfer of Sucking Piglets under Combined Heating. Agropanorama 2025, 1, 14–22. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Rong, L.; Zhang, G.; Brandt, P.; Bjerg, B.; Pedersen, P.; Granath, S.W.Y. A Two-Node Mechanistic Thermophysiological Model for Pigs Reared in Hot Climates–Part 1: Physiological Responses and Model Development. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 212, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xin, H. Modeling Heat Mat Operation for Piglet Creep Heating. Trans. Am. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2000, 43, 1261–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.C.; Ramirez, B.C.; Hoff, S.J. Modeling and Assessing Heat Transfer of Piglet Microclimates. AgriEngineering 2021, 3, 768–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fialho, F.B.; Bucklin, R.A.; Zazueta, F.S.; Myer, R.O. Theoretical Model of Heat Balance in Pigs. Anim. Sci. 2004, 79, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milan, H.F.M.; Maia, A.S.C.; Gebremedhin, K.G. Prediction of Optimum Supplemental Heat for Piglets. Trans. ASABE 2019, 62, 321–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opderbeck, S.; Keßler, B.; Gordillio, W.; Schrade, H.; Piepho, H.P.; Gallmann, E. Influence of Cooling and Heating Systems on Pen Fouling, Lying Behavior, and Performance of Rearing Piglets. Agriculture 2021, 11, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spodyniuk, N.; Zhelykh, V.; Dzeryn, O. Combined Heating Systems of Premises for Breeding of Young Pigs and Poultry. FME Trans. 2018, 46, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostov, K.; Ivanov, I.; Atanasov, K. Development and Analysis of a New Approach for Simplified Determination of the Heating and the Cooling Loads of Livestock Buildings. EUREKA Phys. Eng. 2021, 2, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, K.J.; Stalder, K.J.; Harmon, J.D.; Karriker, L.A.; Johnson, A.K. PSII-11 Comparison of Multiple Heat Sources in the Farrowing House: Effect on Production and Energy Efficiency. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97, 232–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldara, F.R.; Dos Santos, L.S.; Machado, S.T.; Moi, M.; de Alencar Nääs, I.; Foppa, L.; Garcia, R.G.; Dos Santos, R. de K.S. Piglets’ Surface Temperature Change at Different Weights at Birth. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 27, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, E.F.; Vasdal, G.; Flø, A.; Bøe, K.E. Static Space Requirements for Piglet Creep Area as Influenced by Radiant Temperature. Trans. ASABE 2008, 51, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmichev, A.V.; Lyamtsov, A.K.; Tikhomirov, D.A. Heat and Energy Performance of IR Irradiation Systems for Young Animals. Light Eng. 2015, 3, 57–58. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmichev, A.V. Description of Heat Exchange processes in the “Animal-Environment” System. Bull. VIESH 2017, 3, 33–38. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Bogoslovsky, V.N. Thermal Regime of the Building; Stroyizdat: Moscow, Russia, 1979. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Shatskov, A.O. Determining Temperature of Adiabatic Surfaces in Rooms with Radiant Heating. Therm. Eng. 2021, 68, 717–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banhidi, A.; Machkashi, L. Radiant Heating; Stroyizdat: Moscow, Russia, 1985. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Berman, A.; Horovitz, T. Radiant Heat Loss, an Unexploited Path for Heat Stress Reduction in Shaded Cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 3021–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.; Howell, D.; Khrustalev, B.A. Radiation Heat Transfer; Mir: Moscow, Russia, 1975. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow, E.M.; Sess, R.D. Radiative Heat Transfer; Energia: Leningrad, 1971. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, A.G.; Zhuravlev, Y.A.; Ryzhkov, L.N. Heat Transfer by Radiation Handbook; Energoatomizdat: Moscow, Russia, 1991. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmichev, A.V. Physical Model of Heat Exchange of Piglet with Environment. Electr. Technol. Electr. Equip. APK 2019, 1, 124–132. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Lebed, A.A. Microclimate of Livestock Premises; Kolos: Moscow, Russia, 1984. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- McCracken, K.J.; Caldwell, B.J. Studies on Diurnal Variations of Heat Production and the Effective Lower Critical Temperature of Early-Weaned Pigs Under Commercial Conditions of Feeding and Management. Br. J. Nutr. 1980, 43, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luchakov, Y.I.; Shabanov, P.D.; Nesmeyanov, A.A.; Khadartsev, A.A. The Influence of the Ratio of the Core Size and Shell on Heat Homeostasis of Some Animals. Bull. New Med. Technol. 2014, 8, 2–20. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulumbaev, E.B. Heatphysical Assessment of Thermally Neutral Zone Gomoyotermny of the Organism. Appl. Math. Phys. 2018, 50, 292–298. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikheev, M.A.; Mikheeva, I.M. Fundamentals of Heat Transfer; Energia: Moscow, Russia, 1977. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Galin, N.M.; Kirillov, P.L. Heat and Mass Transfer (in Nuclear Power); Energoatomizdat: Moscow, Russia, 1985. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Rabanillo-Herrero, M.; Padilla-Marcos, M.Á.; Feijó-Muñoz, J.; Meiss, A. Effects of the Radiant Heating System Location on Both the Airflow and Ventilation Efficiency in a Room. Indoor Built Environ. 2019, 28, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RD-APK 1.10.02.04-12; Methodological Recommendations on Technological Design of Pig Farms and Complexes. Minselkhoz RF: Moscow, Russia, 2012. (In Russian)

- Botto, Ľ.; Lendelová, J. Surface Temperature of Warm-Water Pads for Heating Piglets in Farrowing Pens. Slovak J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 49, 116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Zhelykh, V.; Dzeryn, O.; Shapoval, S.; Furdas, Y.; Piznak, B. Study of the Thermal Mode of a Barn for Piglets and a Sow, Created by Combined Heating System. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2017, 5, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Reese, M.; Buchanan, E.; Tallaksen, J.; Johnston, L. Behavior and Performance of Suckling Piglets Provided Three Supplemental Heat Sources. Animals 2020, 10, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bystritsky, D.N.; Kozhevnikova, N.F.; Lyamtsov, A.K.; Murugov, V.P. Electric Infrared Radiation Installations in Animal Husbandry; Energoizdat: Moscow, Russia, 1981. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).