Abstract

The purpose of this study is to test the moderating effect of gender on the relationship between the Big Five personality traits of agriculture and food science senior students and their entrepreneurial intention. For this purpose, the study employed an online survey, which was directed to senior students in the agriculture and food science program at four public universities in Saudi Arabia. Out of the 450 forms distributed, 410 provided usable responses for analysis. This process yielded an answer ratio of 91%. The findings of PLS-SEM showed that the Big Five personality traits have a significant positive influence on students’ intent toward entrepreneurship, except for neuroticism, which was found to have a negative but insignificant influence. The results of moderating effect analysis showed no significant moderating influences of gender on the link between two traits, i.e., agreeableness and neuroticism and entrepreneurship intention. On the other side, gender was found to have a significant moderating role in the relationship between the four other traits, extraversion, conscientiousness, openness to experiences, and entrepreneurial intention. Male students have a more moderating influence in relation to extraversion and conscientiousness than females do on entrepreneurial intention, whereas female students have a more moderating influence regarding openness to experiences than males on entrepreneurship intention. The results confirm that to ensure a sustainable agriculture ecosystem, each gender should receive appropriate development programs to strengthen their personal traits to stimulate entrepreneurial intention.

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship has recently drawn the attention of researchers and policymakers due to its several positive impacts, e.g., economic growth, job creation, and social development [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Therefore, it gained attention from academics and policymakers over the last few decades. Governments around the world have acknowledged the importance of entrepreneurship, and most governments are prioritizing supporting these small enterprises for resilience. They are continually increasing entrepreneurship activities and investing in entrepreneurial-minded programs in order to enhance socio-economic growth [8,9,10]. The government of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) added entrepreneurship to the national agenda as one of the national priorities. Saudi Vision 2030 encourages Saudi youth, whether male or female, to engage in entrepreneurship activities and pursue entrepreneurship as a career [11]. Historically, the KSA has been categorized as a “gender-segregated” nation, which means that the isolation of women is a major feature of Saudi society [12,13]. Nevertheless, Saudi Vision 2030 has implemented a unified strategy of gender equality in numerous fields by expanding women’s privileges and empowering them significantly. Hence, the leadership is keen to empower women politically, economically, socially, and psychologically [11,14].

Recent research by Khalaf et al. [15] showed that 42% of women in Saudi Arabia intended to become entrepreneurs before the COVID-19 pandemic. More female entrepreneurs in Saudi Arabia means more job opportunities and a diverse economy. The government formed a special authority known as “Monsha’at” to support small businesses by encouraging entrepreneurship and innovation, especially amid- and post-COVID-19 pandemic, where most small enterprises are suffering from the crisis. Saudi Arabia rated number 6 on the GEI “Global Entrepreneurship Index” because of investment in small businesses, especially in the food industry [11]. Yet, the SCDSI “Saudi Central Department of Statistics and Information” announced that the unemployment rate is expected to be more than 12.9% in 2022, whereas 1,590,878 undergraduate students enrolled in higher education institutions [11]. However, the Saudi labor market is unable to absorb this number of graduates on an annual basis. Hence, the Saudi government has invested in higher education institutions around the country to foster entrepreneurial education and spread the investment culture among college students [16,17,18]. Universities, in particular, have played a crucial role in inspiring and supporting students to engage in entrepreneurship activities [19,20,21].

Regarding the link between entrepreneurship intention and personality traits, Zhao et al. [22] stated that personality traits are important to be examined since they could affect entrepreneurship intention and the sustainability of the industry. The decision to choose entrepreneurship as a career path is influenced by i traits [23,24,25,26]. It has long been assumed that students’ entrepreneurial intentions are predicted by their characteristics [27]. In that sense, Holland [28] confirmed that personality is a significant factor in the selection of occupation. As a result, it is critical for policymakers, economists, and academics to understand the personality traits of potential entrepreneurs. There is a large body of literature attempting to determine the personality traits of individuals; for example, Cattell [29] listed 16 personality traits, whereas Allport [30] reported 4000 personality traits. Scholars have frequently explained how these traits influence the intention of entrepreneurship using the “Big Five” framework [22,31,32,33]. The “Big Five Trait Taxonomy” theory was developed as a list of adjectives to understand individuals’ personalities [34]. The theory was originally launched by Fiske [35]. The traits are also known as OCEAN and are considered an effective tool for understanding the different individual personalities in dissimilar situations [36]. The theory has served as the foundation for the current study.

According to a literature review [37,38,39], gender has a close relationship to the character of an entrepreneur. Therefore, earlier studies conducted by Al-Dajani and Marlow [40], as well as Jamali [41], indicated that gender as personal characteristic impacts on the intention of becoming an entrepreneur. Studies such as those by De Bruin et al. [42], Gupta et al. [43], Nowiński et al. [44], and Zhao et al. [32] argued that males have a higher intention of entrepreneurship than females. Likewise, Kelley et al. [45] proposed that male students are more willing to engage in entrepreneurial activities compared to female students. However, Smith et al. [46] argued that the entrepreneurial intentions of men and women are similar. Kee and Abdul Rahman [47] indicated that depending on many aspects like nations, cultures, and certain business stages, gender preferences may vary. On the other hand, Kumar et al. [48] confirmed limited studies on the gender role in the relationship between entrepreneurial intention and orientation. Therefore, there was a call for further studies in this aspect [49,50]. In particular, Lopez-Núnez et al. [51] argued that further studies are required for a better understanding of gender–personal traits’ entrepreneurial intention relationship. This research is an attempt to adress this gap in knowledge in relation to the role of gender in the link between the personality traits and entrepenurial intention.

The purpose of this research is to investigate the moderating effect of gender on the personality traits–digital entrepreneurial intention relationship in the Saudi food industry. Digital entrepreneurship has created great opportunities for digital natives to develop their businesses, which could be of great value for solving Saudi food insecurity [9]. In particular, the current research investigates the role of gender in the interrelationship between senior agriculture and food science students’ personality traits (“openness to experiences, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism”) and entrepreneurial intention. The study has two objectives. Firstly, the study investigates direct influences of personality traits on graduates’ digital entrepreneurial intention, post-COVID-19 pandemic. Secondly, it explores the moderation role of gender on the link between personality traits and digital entrepreneurship intention among agriculture and food science senior students. Hence, the current research answer the following research questions: (1) What are the influnces of Big Five personality traits on the enterpreneurial intention of agriculture and food science senior students? (2) What is the effect of gender on the relationship between Big Five personality traits on the enterpreneurial intention of agriculture and food science senior students? How could policy makers stimulate enterpreneurial intention of agriculture and food science senior students in the KSA?

The current study provides suggestions for researchers, educators, and decision-makers, particularly in a KSA context, on the promotion of sustainable agriculture and ecosystem for entrepreneurship to support government priorities. The results provide a better understanding of the role of gender in the relationship between Big Five personality traits and the enterpreneurial intention of agriculture and food science senior students. The results would enable policymakers to encourage women’s involvement in business ventures, particularly in the food and agriculture sector, in nations where their participation is unequal compared to men, such as the KSA [11]. In the following sections, the research continues conceptual analysis regarding the personal traits-digital entrepreneurship intention relationship. Subsequently, Section 3 and Section 4 present the research methods and findings respectively. Finally, Section 5 and Section 6 discuss the findings and highlight the conclusion as well as the limitation of the research.

2. Hypothesis Development

2.1. Personality Traits and Entrepreneurial Intention

Although academic interest in the psychological traits of entrepreneurs and the entrepreneurial process has increased [32,52], more studies are required to address this issue [53,54]. Durand et al. [55] argued that the driver of individual behavior is personality. Previous research such as Durand et al. [56] and Sarwar et al. [23] showed that personality traits influence individuals’ decisions regarding their involvement in entrepreneurship. In the same context, Fietze and Boyd [57] indicated that personal traits have been closely linked to entrepreneurial intention and successful entrepreneurship. Likewise, Ajzen [58] emphasized that individual traits can influence personal attitudes, intentions, and, ultimately, behaviors. In that sense, Yeh et al. [59], stated that the Big Five are usually cited as a significant dimension of character influencing individuals’ drive for entrepreneurship. Several empirical research has studied the association of personal traits and entrepreneurship [60,61]. The next paragraphs elaborate on the conclusions of these investigations.

Neuroticism is defined as having undesirable feelings and reactions regularly, including anxiety, fear, and low confidence [31]. Therefore, highly neurotic people have destructive emotions, e.g., anxiety, hostility, depression, and vulnerability [22], whereas people with lower levels of neuroticism are confident, quiet, and equable [33,62]. According to Zhao and Seiber [22], entrepreneurship as a career path is laden with psychological stress since entrepreneurs are often an unstructured environment that requires long hours and frequently lacks distinctions between work and personal life. This is because entrepreneurs have full responsibility for all their ventures’ features. As a result, entrepreneurship as a career path requires a high level of self-confidence [63]. Hence, neuroticism was found to have a link to negative behavior [64]. However, Jain et al. [65] proposed that neuroticism did not have a negative influence on entrepreneurship intention. Laouiti et al. [27] confirmed that students’ entrepreneurial intent has developed emotional steadiness and lesser degrees of neuroticism.

Extraversion is one of the Big Five traits that refers to the amount to which an individual is forceful, domineering, motivated, and enthusiastic [66]. Highly extraverted persons are joyful and appreciate teams, whereas less extraverted individuals are likely to work individually and independently [32]. Hence, people with a lower level of extraversion are not likely to engage in entrepreneurship activities [53]. This is due to the continual need for entrepreneurs to create and maintain relationship with other people. Therefore, Laouiti et al. [27] suggested that extraversion is positively correlated with students’ intention of entrepreneurship. Likewise, Jain et al. [65] evidenced that extraversion had a significant influence on entrepreneurship intent.

Agreeableness is referred to as kindness and friendliness. Caliendo et al. [33] describe agreeableness as a trusting nature and a forgiving established by altruism and flexibility. Jain et al. [65] noted that agreeableness plays a positive substantial effect on entrepreneurial intention. An agreeable individual has a low probability of starting their businesses because of a strong aptitude to adapt to rules and processes [53]. Likewise, Orhan and Scott (2016) [50] argued that agreeableness did not indicate an intention of entrepreneurship. Additionally, agreeableness was found to have a negative affect on people’s performance [64]. Laouiti et al. [27] suggested that students’ entrepreneurial intent is likely to be negatively associated with agreeableness.

Openness to experience is also called imagination. Zhao et al. [31] defined it as a person’s rational interest and propensity to pursue innovative ideas. Openness to experiences is reflected in creativity, transformation, and a robust drive to discover original concepts, which is the core of entrepreneurship [32,67]. Therefore, openness to experience may be a key driver in launching an entrepreneurial career for students because it has a positive relationship with graduates’ intention of entrepreneurship. According to Zhao et al. [32], individuals who engage in entrepreneurship often challenge the constraints and think about the future. Therefore, Jain et al. [65] have proven that openness to new experiences is best interpreter of students’ intention to entrepreneurship and has a favorable impact on it. Openness to experiences may be a key asset for students to launch an entrepreneurial career because openness is strongly connected with students’ entrepreneurial intent [27].

Conscientiousness refers to a person’s desire to undertake task well and to make one’s work well and seriously; hence, such individuals are efficient and careful [32]. Various aspects of conscientiousness are identified, as Zhao and Seibert [22] acknowledged two categories of accomplishment enthusiasm and steadiness. Likewise, Van Ness and Seifert [62] asserted that conscientiousness consists of two aspects: the desire for success and the ability to work hard. According to Ferreira et al. [68], those who have a greater demand for success have a greater intention of entrepreneurship. In that sense, Durand et al. [56] asserted that individuals with conscientious personalities have a favorable relationship with their trading behavior. However, it was argued that conscientiousness has no substantial connection with entrepreneurial intention [65]. Furthermore, individuals who have high level of conscientiousness are less tolerant to risk compared to those with high level of openness to experiences and extroversion [69]. Laouiti et al. [27] indicated that conscientiousness is essential for pursuing entrepreneurship activity. According to the preceding discussion, pursuing entrepreneurship activity is connected with greater ranks of three traits, i.e., “extraversion, conscientiousness, and openness” [54]. Hence, we could hypothesise that:

H1.

Neuroticism negatively affects agriculture and food graduates’ digital entrepreneurial intentions.

H2.

Extraversion positively affects agriculture and food graduates’ digital entrepreneurial intentions.

H3.

Agreeableness positively influences agriculture and food graduates’ digital entrepreneurial intentions.

H4.

Openness positively affects agriculture and food graduates’ digital entrepreneurial intentions.

H5.

Conscientiousness positively affects agriculture and food graduates’ digital entrepreneurial intentions.

2.2. The Moderating Effect of Gender

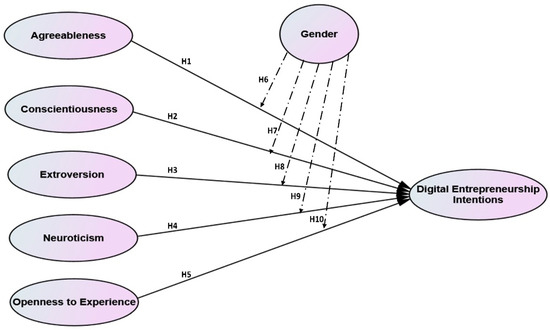

In studying human behavior, the available literature has given gender variations in personal traits a lot of attention [66]. However, investigations have shown contradictory results in relation to the effect of this on becoming entrepreneurs [27]. In general, women reported high levels in the negative affectivity scale and can change their moods more quickly than men from a psychological point of view [70]. Vedel [71] conducted a meta-analysis on gender variances in relation to personality traits and found that women reported higher levels of conscientiousness, agreeableness, and neuroticism but no significant differences regarding openness and extraversion. Other researchers have found that women tend to be more agreeable than men, have higher levels of neuroticism [72,73], are more extroverted [70,74], and are more open to experiences [74]. However, men have also been discovered to be more conscientious [74] and open to experiences than females [49]. Women scored higher in agreeableness and conscientiousness than men [75]. Similarly, Bajwa et al. [66] indicated that the difference between men and women in terms of the influence of various personality traits on cognitive adaptation is mostly related to two personality factors, namely extraversion and neuroticism. However, other researchers [43,76] did not distinguish personal traits based on gender in the field of entrepreneurial intention, believing that possibilities of success are not based on gender. Laouiti et al. [27] argued that female students want a combination of attributes with lower degrees of agreeableness and neuroticism to control predominance of such traits if they are willing to engage in entrepreneurial activity. This reasoning supports research that indicates that low agreeableness and low neuroticism remain essential indicators of entrepreneurship intent. A recent study on the effects of role models and gender on freshman students’ entrepreneurial intention in KSA [77] showed that females are more infunced by subhective norms and perceived behavioral control than males. Hence, gender was found to moderate the effect of subjective norms and perceived behavioral control on entrepreneurial intention of senior students in KSA. The current study intended to examine whether gender moderates personality traits and student intention to become entrepreneural links (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The theoretical model.

The study takes the first attempt to test the moderating role of gender in personal traits-digital intent of entrepreneurship link. Therefore, we can argue that:

H6.

Gender moderates the influence of neuroticism on the digital entrepreneurship intention of agriculture and food graduates.

H7.

Gender moderates the influence of extroversion on the digital entrepreneurship intention of agriculture and food graduates.

H8.

Gender moderates the influence of agreeableness on digital entrepreneurship intention of agriculture and food graduates.

H9.

Gender moderates the influence of openness to experiences on the digital entrepreneurship intention of agriculture and food graduates.

H10.

Gender moderates the influence of conscientiousness on the digital entrepreneurship intention of agriculture and food graduates.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Measures

The study questionnaire has three sections. Section One proposed study goals and questionnaire guidelines. In the second section, respondents were asked to provide some demographic data. Section Three presents the study’s main questions using a Likert scale from 1 to 5 points, where 1 means strongly disagree and 5 means strongly agree. Digital entrepreneurial intent was operationalized using three factors adapted from Lee et al. [78]. The three factors were adjusted to be acceptable for use in our research. All factors had excellent reliability (a = 0.955). Spence et al. [79] asserted that the Big Five taxonomy had gained a good reputation in the field of personality research. Research on personality traits has been conducted across a variety of times, cultural contexts, and geographical settings [80]. The “NEO Five-Factor Inventory” (NEO–FFI) was the source from which we derived the personality traits scale that we used in our research [70,78]. According to Teng et al.’s [81] argument, little factors have the potential to cut down on the costs associated with research, boost the number of participants, and make it easier to administer surveys. Table 1 outlines both the dimensions and the items that construct the personality traits. The five dimensions of personality traits that were used demonstrated a level of internal consistency reliability that was deemed satisfactory: agreeableness (a = 0.901), extroversion (a = 0.903), conscientiousness (a= 0.979), openness to experiences (a = 0.919), and neuroticism (a = 0.969).

Table 1.

Respondents’ characteristics.

No modifications were made to the content of the questionnaire that was used after the instrument was tested by fourteen university academics and fourteen graduates to certify consistency, clarity, as well as simplicity. We have protected the privacy of the respondents and confirmed that their responses are strictly confidential. Because research questionnaires was the primary method of data collection, the CMV “likelihood of common method” variance became an issue [82]. Hence, we conducted Harman’s single-factor analysis through the EFA “exploratory factor analysis” technique to detect any probable CMV. The results confirmed CMV was not an issue since a single item explained 37% of the variance in the endogenous variables, which was less than 50% as suggested by [83].

3.2. Participants and Data Collection

Our study randomly surveyed graduate students at KSA public universities. The research team sent an electronic survey to four public higher education institutions in the kingdom. These four public universities cover the main province in the KSA: King Faisal University, Al-Hofuf, Saudi Arabia (Eastern Province), Imam Mohammad ibn Saud Islamic University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (Riyadh Province), Umm Al-Qura University Mecca, Saudi Arabia (Mecca Province), and King Khaled University, Abha, Saudi Arabia (Asir province). The research team utilized their extensive personal connections with professors and lecturers at the targeted universities (agriculture and food science faculities) to disseminate the online questionnaire through university email and various social media platforms such as WhatsApp groups. The participation was completely voluntary, and the purpose of the survey, as well as the strict confidentiality of any gathered information, was clearly stated in the introduction of the questionnaire.

We asked agriculture and food science senior students to fill out the survey because they may be interested in starting their own businesses. The designated participants received the survey during the months of February and March in 2022. Out of 450 forms distributed, 410 provided usable responses for analysis. This process yielded an answer ratio of 91%. We had no problem with late answers. T-test results showed no statistical major variances (p > 0.05) in the means, confirming no bias in the response of respondents [84]. Nunnally [82] cautions that relying solely on self-report questionnaires as a data collection method in a study may result in “common method variance” (CMV). To mitigate this, the researchers in the present study employed Harman’s single-factor analysis, where all extracted factors are set to 1.0. They also conducted an exploratory factor analysis using SPSS and the non-rotational method, which revealed a unidimensional structure with a single factor accounting for 37% of the variance. This indicates that CMV may not be a major concern in the study as the single factor accounted for less than half of the variance.

3.3. Data Analysis Techniques

In our study, we have used PLS-SEM “partial least squares structural equation modeling” method to examine the collected data with the SmartPLS vs 4 software program. PLS-SEM is a non-parametric method that exploits the explained variance in latent dimensions that cannot be observed directly. PLS-SEM is broadly employed in management science and is said to produce reliable results [85]. Smart PLS-SEM has often been adopted for examining inter-relationships between various variables. Following Leguina’s [86] recommendation, proposed theoretical model was evaluated in two steps: first for convergent and discriminant validity, then for hypotheses validation.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Participants’ Demographic

The targeted students were nearly evenly divided between males (52%) and females (48%). The vast majority (94%) were between 17 and 25 years of age. A total of 30% of the respondents were from King Faisal University, 25% from Mohammad ibn Saud Islamic University, 25% from Umm Al-Qura University, and 20% from King Khaled University (See Table 1). The mean scores of the respondents varied between 2.31 and 4.61. The standard deviation varied between 0.881 and 1.55, which shows that the answers are more spread out and not clustered near the mean [84]. According to Nunnally [82], neither the skewness nor the kurtosis have any values that are more than −2 or +2, indicating a normal distribution. In addition, the value of the VIF “variance inflation factor” was found to be less than 0.5 for study items (as shown in Table 1), indicating that multicollinearity is not an issue [87].

4.2. Outer Model Assessment

Following the recommendations made by Hair et al. [83], Kline [88] and Kono and Sato [89], a number of criteria (indices) were employed to verify the reliability and validity of the research model. These indices contain the CR “composite reliability” value; “internal consistency reliability” (a) value; “convergent validity” index; and “discriminant validity” index.

4.2.1. Convergent Validity

The convergent validity of the employed scale was evaluated through several criteria, including Cronbach’s alpha, reliability, composite reliability, loadings, and AVE. As depicted in Table 2, all Cronbach’s alpha (a) values for the study dimensions: digital entrepreneurship intention (DEI) (a = 0.955); agreeableness (a = 0.901); conscientiousness (a = 0.901); extroversion (a = 0.903); neuroticism (a = 0.969); and openness to experiences (a = 0.903), exceeded the value of 0.7, providing evidence of a high internal reliability. Additionally, the composite reliability (CR) values for all the employed scales: digital entrepreneurship intention (CR = 0.959); agreeableness (CR = 0.923); conscientiousness (CR = 984); extroversion (CR = 0.942); neuroticism (CR = 0.956); and openness to experiences (CR = 0.982), exceeded the threshold value (0.7), further confirming an appropriate internal reliability [88].

Table 2.

Measurement Model & VIF for multicollinearity.

Additionally, each factor had SFL “standardized factor loading” values of more than 0.70, indicating that the research constructs are reliable. Moreover, convergent validity was determined by comparing AVE values to 0.5 [83]. This value represents the minimum acceptable convergent validity. Furthermore, the major indices were evaluated to test the scale discriminant validity, as recommended by Leguina [86]. These indices encompassed the “Fornell-Larcker criterion method”, the “cross-loading matrix”, and the “heterotrait-monotrait method” ratio (HTMT).

4.2.2. Discriminant Validity

The discriminant validity was checked in our study through checking the cross-loadings, Fornell-Larcker criterion, and heterotrait-monotrait ratio. Table 3 shows that each latent unobserved variable’s outer-loading (bolded) is higher than its cross-loading, which ensures discriminant validity. Secondly, Table 4 shows that diagonal AVE values are greater than the inter-variable correlation, further supporting a high discriminant validity [83]. Finally, HTMT values have to be less than 0.90, according to Leguina [86], since HTMT levels should be less than the reference value (see Table 4). Our results confirmed all of this. We then moved to examine the study’s hypotheses using the structural outer model.

Table 3.

Cross-loading for study factors.

Table 4.

Fornell-Larcker criterion, and HTMT findings.

4.3. Inner Model Assessement

The hypotheses were tested using the inner model in the SmartPLS 4. The purpose is to test the model’s ability to explain and predict the changes in endogenous latent variables caused by exogenous latent variables [83]. Furthermore, to test the goodness of model fit (GoF), we adopted the formula proposed by Chin [90], in which the GoF can be calculated by taking the square root of (the average of R2 multiplied by the average of all AVE values). The GoF test resulted in a value of 0.47, indicating a large goodness of model fit, as suggested by Wetzels et al. [91]. The value for endogenous latent variables should be at least 0.10 to confirm the GoF. Accordingly, in our study, the endogenous latent variables DEI has an R2 value of 0.250, surpassing the suggested value and indicating further that the research-suggested model satisfactorily matched the collected empirical data. Likewise, the Stone-Geisser Q2 statistics showed a value of (0.116) for DEI; this value is higher than zero, confirming the acceptable findings [92]. Additionally, the SRMR value has to be less than 0.08, and the NFI value ought to be greater than 0.90 to ensure a good model fit to the data [83,92]. The SRMR was 0.037, and the NFI value was 0.932, exceeding the recommended threshold value and approving a good of fit. Finally, the f2 values, which calculate the changes of the R2 when an exogenous variable is removed, were calculated. The results revealed the following f2 values for all the six exogenous variables impact on DEI (agreeableness, f2 = 0.008; conscientiousness, f2 = 0.023; extroversion, f2 = 0.078; neuroticism, f2 = 0.005; and openness to experiences, f2 = 0.007). These results means that any exogenous variables when removed from the model will cause a small effect (<0.15) size on the main model, as suggested by Cohen [93].

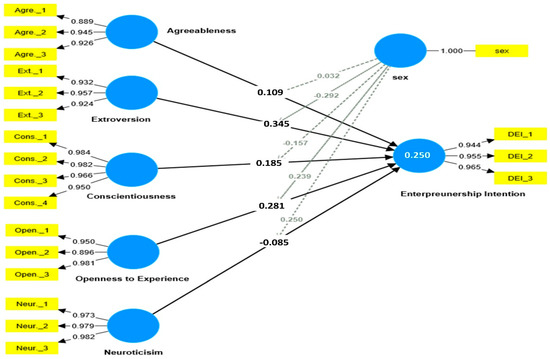

After confirming a good of fit, a bootstrapping method was conducted in smart PLS4 to decide the path coefficient and t-value for the relationships and moderating effects, as depicted in Table 5 and Figure 2. The current research paper proposed and tested ten hypotheses; 5 out of the 10 are direct relationships, and 5 are moderating. The PLS-SEM outcomes exhibited that the extroversion personality trait has the highest significant and positive impact on DEI (β = 0.345, t-value = 6.075, p < 0.001), thus supporting hypotheses H3. Similarly, openness to experiences has a positive and significant impact on DEI (β = 0.280, t-value = 3.295, p < 0.001); therefore, hypothesis H5 was supported. The results also confirmed that DEI was positive and significantly impacted by agreeableness (β = 0.109, t-value = 1.965, p < 0.001), and conscientiousness (β = 0.185, t-value = 3.595, p < 0.001), thus supporting hypotheses H1, and H2. On the other, hand neuroticism has an insignificant negative influence on DEI (β = 0.25, t-value = 5.279, p < 0.001); hence, H4 is not accepted.

Table 5.

Hypotheses Testing Results.

Figure 2.

The study models.

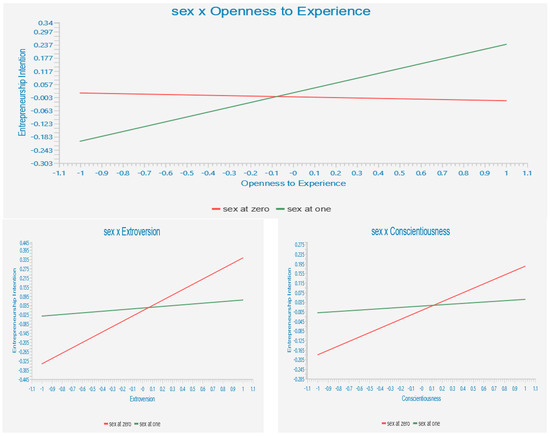

The results also provide data about the moderating effects of the categorical variable (gender; male-female) on the tested relationships. As shown in Table 5, gender had no significant moderation impact on the neuroticism-DEI link (β = 0.05, t-value = 1.084, p = 0.98); Similarly, gender showed no significant moderating effect on the connection between agreeableness and DEI (β = 0.032, t-value = 0.316, p = 0.752); thus, hypotheses H6 and H10 were not supported. On the other hand, as shown in Table 5 and Figure 2 and Figure 3, gender had a significant moderation impact on the extroversion-DEI link (β = −0.292, t-value = 2.537, p < 0.01) in which the moderating impact in the male side was higher than the moderating impact in female side (see Figure 3); thus, hypothesis H7 was supported. Similarly, gender had a significant moderation impact on the conscientiousness-DEI link (β = −0.157, t-value = 1.962, p < 0.05), where the moderation influence on the male side was higher than the moderating impact on the female side (see Figure 3); thus, hypothesis H9 was supported. Finally, gender had a significant moderation impact on openness to experiences-DEI link (β = 0.239, t-value = 2.348, p < 0.01), where the moderating influence on the female side was higher than the moderating impact on the male side (see Figure 3); thus, hypothesis H8 was supported.

Figure 3.

Simple Slope Analysis for Moderating.

5. Discussions

Due to its positive economic and social consequences, entrepreneurship has gained the attention of decision-makers as well as scholars over the last few decades. Hence, decision-makers in many countries have established supporting regulations and programs to spread entrepreneurship among university graduates as a part of the ecosystem. The current study tested the influences of the Big Five personality traits of agricultural and food science students’ on their intent of entrepreneurship, especially in the Saudi food industry. The study tested the moderation effect of gender on the above-mentioned relationship. The findings of PLS-SEM showed that agricultural and food science students with high extroversion personality traits have the highest significant and positive intentions to engage in entrepreneurship (H3). This confirms that people with high level of extraversion are more likely to engage in entrepreneurship activities [53]. This finding supports the recent work of Laouiti et al. [27] and Sobaih and Elshaer [7], who also found that extraversion is positively correlated with students’ intent toward entrepreneurship. It is also in line with the findings of Jain et al. [65], who found that extraversion has a significant influence on the intent of entrepreneurship. This confirms that when agriculture and food science food students are active and assertive, they are more likely to have high entrepreneurship intentions.

Openness to experiences was found to be the second variable that has the most significant positive impact on entrepreneurship intention (H5). This finding is inconsistent with Jain et al. [65], who argued that openness to new experiences is among the best predictors of students’ entrepreneurial intention. The current research supports the work of Elsaher and Sobaih [5], who found that when agriculture and food science students are open, they are more likely to engage in entrepreneurship intention, especially DEI [4]. This means that when agricultural and food science senior students challenge the status quo and pursue their creative ideas, they are more likely to become successful entrepreneurs [6].

The findings revealed a positive influence of the agreeableness of agricultural and food science graduates on their DEI (H1). The current study contradicts the results of previous research, which found that students’ intent of entrepreneurship is likely to be negatively associated with agreeableness [27]. It also disagrees with Pak and Mahmood [64], who found that agreeableness negatively affects persons’ risky practices; hence, agreeable people are less likely to start their own businesses [53]. The finding is not in line with the findings of Kumar et al., [48] who stated that agreeableness could not predict the intention of entrepreneurship among senior students. Moreover, the results showed a positive influence of conscientiousness on agricultural and food science students’ intent toward entrepreneurship (H2). This result is in line with Laouiti et al. [27], who indicated that conscientiousness is essential for pursuing an entrepreneurial career and connects with students’ entrepreneurial intent. However, it does not match the findings of Jain et al. [65], who found that conscientiousness has no substantial relationship with entrepreneurial intention. On the other hand, the results showed that neuroticism has a negatively insignificant impact on entrepreneurship intention (H4). The finding supports the findings of Jain et al. [65], who found that neuroticism did not have negative influence on entrepreneurship intention. Laouiti et al. [27] confirmed that students’ entrepreneurial intent is not connected lower degrees of neuroticism. The above findings confirm that pursuing digital entrepreneurship intent is connected with greater levels of extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness to experiences, albeit it is connected negatively with neuroticism.

With regard to the moderating effect of gender in the link between the Big Five personality traits and agriculture and food science food senior students’ intent of entrepreneurship, the results showed no significant moderating influence of gender on students’ neuroticism and agreeableness–entrepreneurial intention relationship (H6 and H10, respectively). The results showed that female agricultural and food science students tend to be more agreeable than male agricultural and food science students, who have higher levels of neuroticism [72,73]. However, this has no significant impact on DEI. This supports the assumption that possibilities of success in entrepreneurship are not based on gender [43,76]. Nonetheless, it is also crucial to note that female students need lower degrees of agreeableness and neuroticism to control the predominance of such traits to engage successfully in an entrepreneurial activity [27].

On the other hand, gender had a significant moderation influence on the extroversion-DEI link (H7). It was found that male students have higher the moderating impact than the females. This could be because men are dominant in the Saudi culture, so they tend to become more extroverted than women, which has influences their entrepreneurial intentions [3]. This finding contradicts the work of other researchers in other countries’ contexts, mainly in Western countries with different cultures [70,74] where women tend to be more extroverted than men. Furthermore, gender had a significant moderation influence on the conscientiousness-DEI link (H9), where the moderating impact on the male side was higher than the moderating impact on the female side. This confirms that males students have more conscientious traits than females do [74]; hence, this affects their entrepreneurial intentions. This contradicts other assumptions that women scored higher in conscientiousness than men [75].

Gender had a significant moderation influence on openness to experiences-DEI link (H8), where the moderating impact on the female students’ side was higher than the moderating impact on the male side. This contradicts the most common assumption that men are more open to new experiences than female [49]. This was not the case in the Saudi context, as women, especially in the food industry, have become more open to experiences and entrepreneurship in the last decade, especially after launching the Saudi Vision 2030 [14]. Despite Saudi Arabia being classified as a gender-segregated nation, which limited women’s access to several positions in the past, the recently inaugurated Saudi Vision 2030 has promoted gender equality in numerous fields by expanding women’s rights. Hence, the government seeks to ensure that women are empowered politically, economically, socially, and psychologically to contribute to economic and social development. This justifies the growth of women entrepreneurs, as a recent study confirmed that 42% of Saudi women are interested in becoming entrepreneurs [15].

The results of the current study showed significant differences between male and female senior students in agricultural and food science context in KSA in the link between three main traits, extroversion, conscientiousness and openness to experiences and DEI. These results confirm a need for development programs to enhance the traits where differences among agricultural and food science students in the Saudi context may exist [20,21]. For instance, female students need more training to become more deliberate, active and assertive, whereas male students would need more training to open to new and different ideas and experiences. These devlopemnt programs should be integrated in the education programs to stimulate the DEI among agricultural and food science students, who will become the entrepreneurs of tomorrow. This ultimately impacts the sustainability of the Saudi food industry.

6. Conclusions and Implications

This study tested the influences of personality traits on agricultural and food science students’ DEI in a Saudi context. The study tested the moderating effect of gender in this relationship, which has not been examined before. The findings of PLS-SEM showed that four out of personal traits have a significantly and positively impact on agricultural and food science students’ intent toward digital entrepreneurship. The most significant predictor of entrepreneurship among agricultural and food science students’ was extraversion, followed by openness to experiences, conscientiousness, and finally agreeableness. Only neuroticism has a negative influence, though not a significant one, on agricultural and food science students’ DEI. For the first attempt, the moderating role of gender on the relationship between the traits and digital entrepreneurship intention was examined. There were no significant moderating influences of gender on the link between two traits, i.e., agreeableness and neuroticism and entrepreneurship intention. On the other hand, gender had a significant moderation role on the link between the four other traits: extraversion, conscientiousness, openness to experiences, and entrepreneurship intention. Interestingly, males have a more moderating influence in relation to extraversion and conscientiousness than females on entrepreneurship intention, which means these two traits are more prominent in male agricultural and food science students than females and allow them to engage in entrepreneurship. Nonetheless, females have a more moderating influence in relation to openness to new experiences than males on their entrepreneurship intention. This could be because women have been recently empowered in Saudi Arabia; hence, they would like to express themselves and are more open to entrepreneurship experiences than men, especially in the food industry, which is more relevant to them [94].

Furthmore, the current study provides important theoretical and practical iplications into the role that gender may play in shaping entrepreneurial intentions and the interplay between personality traits and entrepreneurial intentions. Theoretically, the results of this study contribute to the growing body of literature on gender and entrepreneurship. By demonstrating the impact of gender on entrepreneurial intentions, the study highlights the need for further research to examine the relationship between gender and entrepreneurship. Additionally, the results of this study also contribute to the literature on the relationship between personality traits and entrepreneurship. By demonstrating that certain personality traits, such as agreeableness, conscientiousness, extroversion, and openness to experiences, are positively associated with entrepreneurial intention and that this relationship may be moderated by gender, the study sheds light on the role that personality traits play in shaping entrepreneurial intentions.

Practically, the results of this study have important implications for entrepreneurial agriculture food and science education. By understanding the impact of gender and personality traits on entrepreneurial intention, educators can tailor their programs to better support and encourage students who are interested in entrepreneurship. Additionally, the results of the current study have implications for organizations that provide support for entrepreneurship. By recognizing the role of gender and personality traits in shaping entrepreneurial intentions, these organizations can better target their resources and support to those who are most likely to benefit from them. Finally, our study findings have some important policy implications, as policy-makers seek to support and encourage entrepreneurship. By understanding the impact of gender and personality traits on entrepreneurial intention, policy-makers can better target their policies and initiatives to support the development of entrepreneurship.

7. Limitation and Future Study Opportunities

The limitations of the current study offer opportunities for future research. This study was conducted with food and agriculture students from a single cultural context (KSA), and the results may not be generalizable to other cultures where the norms and values regarding entrepreneurship and gender may differ. Further research is needed to understand the cultural nuances that may impact the relationship between personality traits, gender, and entrepreneurial intention. The study only examined a limited number of personality traits and their relationship with entrepreneurial intention. There may be other personality traits that are relevant to entrepreneurship and are not captured in this study. This study only provides correlational evidence with a cross sectional survey methods and does not establish causality between personality traits, gender, and entrepreneurial intention. Further research longitudinal perspective is necessary to establish the causal relationships between these variables. Finally, this study only focuses on the impact of gender and personality traits on entrepreneurial intention and does not consider other important factors that may influence entrepreneurial intention, such as motivation, prior experience, and access to resources. These factors should be considered in future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.A.E. and A.E.E.S.; methodology, I.A.E. and A.E.E.S.; software, I.A.E.; validation, I.A.E. and A.E.E.S.; formal analysis, I.A.E.; investigation, I.A.E. and A.E.E.S.; resources, I.A.E. and A.E.E.S.; data curation, I.A.E. and A.E.E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, I.A.E. and A.E.E.S.; writing—review and editing, I.A.E. and A.E.E.S.; visualization, I.A.E. and A.E.E.S.; supervision, I.A.E. and A.E.E.S.; project administration, I.A.E. and A.E.E.S.; funding acquisition, I.A.E. and A.E.E.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia (Grant No. 2876).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the deanship of the scientific research ethical committee, King Faisal University (project number: 2876, date of approval: 1 February 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request from researchers who meet the eligibility criteria. Kindly contact the first author privately through e-mail.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aloulou, W.J. Impacts of Strategic Orientations on New Product Development and Firm Performances: Insights from Saudi Industrial Firms. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2018, 22, 257–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, D.; Aparicio, S. Entrepreneurship Capital Types and Economic Growth: International Evidence. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2016, 102, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.E.; Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.; Younis, N.S. Born Not Made: The Impact of Six Entrepreneurial Personality Dimensions on Entrepreneurial Intention: Evidence from Healthcare Higher Education Students. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Saad, S.K. Entrepreneurial Resilience and Business Continuity in the Tourism and Hospitality Industry: The Role of Adaptive Performance and Institutional Orientation. Tour. Rev. 2021; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Sobaih, A.E.E. I Think I Can, I Think I Can: Effects of Entrepreneurship Orientation on Entrepreneurship Intention of Saudi Agriculture and Food Sciences Graduates. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliedan, M.M.; Elshaer, I.A.; Alyahya, M.A.; Sobaih, A.E.E. Influences of University Education Support on Entrepreneurship Orientation and Entrepreneurship Intention: Application of Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A.E.E.; Elshaer, I.A. Personal Traits and Digital Entrepreneurship: A Mediation Model Using SmartPLS Data Analysis. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, G.A.; Hilman, H.; Gorondutse, A.H. Effect of Entrepreneurial Orientation, Market Orientation and Total Quality Management on Performance: Evidence from Saudi SMEs. Benchmarking Int. J. 2020, 27, 1503–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello-Pintado, A.; Kaufmann, R.; de Cerio, J.M.D. Firms’ Entrepreneurial Orientation and the Adoption of Quality Management Practices: Empirical Evidence from a Latin American Context. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2018, 35, 1734–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Berger, E.S.; Mpeqa, A. The More the Merrier? Economic Freedom and Entrepreneurial Activity. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1288–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almubarak, D.F.A. Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency (Sama) Board of Directors. 154. Available online: https://www.sama.gov.sa/en-us/economicreports/annualreport/5600_R_Annual_En_51_apx.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Moghadam, V.M. Modernizing Women: Gender and Social Change in the Middle East; Lynne Rienner Publishers: Boulder, CO, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Alsubaie, A.; Jones, K. An Overview of the Current State of Women’s Leadership in Higher Education in Saudi Arabia and a Proposal for Future Research Directions. Adm. Sci. 2017, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, O.H.; Sobaih, A.E.E.; Elshaer, I.A. The Impact of Women’s Empowerment on Their Entrepreneurship Intention in the Saudi Food Industry. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, H.A.; El-Hassan, W.S.; Aldossari, A.T.; Alrasheed, H.S. Toward a Female Entrepreneurship Education Curriculum in Saudi Arabia. J. Entrep. Educ. 2021, 24, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Abou-Moghli, A.A.; Al-Abdallah, G.M. A Systematic Review of Women Entrepreneurs Opportunities and Challenges in Saudi Arabia. J. Entrep. Educ. 2019, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Sobaih, A.E.E. Antecedents of Risky Financial Investment Intention among Higher Education Students: A Mediating Moderating Model Using Structural Equation Modeling. Mathematics 2023, 11, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A.E.E.; Elshaer, I.A. Risk-Taking, Financial Knowledge, and Risky Investment Intention: Expanding Theory of Planned Behavior Using a Moderating-Mediating Model. Mathematics 2023, 11, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veciana, J.M.; Aponte, M.; Urbano, D. University Students’ Attitudes Towards Entrepreneurship: A Two Countries Comparison. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2005, 2, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehtap, S.; Pellegrini, M.M.; Caputo, A.; Welsh, D.H. Entrepreneurial Intentions of Young Women in the Arab World: Socio-Cultural and Educational Barriers. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 880–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubker, O.; Naoui, K.; Ouajdouni, A.; Arroud, M. The Effect of Action-Based Entrepreneurship Education on Intention to Become an Entrepreneur. MethodsX 2022, 9, 101657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Seibert, S.E. The Big Five Personality Dimensions and Entrepreneurial Status: A Meta-Analytical Review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saewar, D.; Sarwar, B.; Raz, M.A.; Khan, H.H.; Muhammad, N.; Azhar, U.; Zaman, N.u.; Kasi, M.K. Relationship of the Big Five Personality Traits and Risk Aversion with Investment Intention of Individual Investors. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qadasi, N.; Zhang, G.; Al-Awlaqi, M.A.; Alshebami, A.S.; Aamer, A. Factors Influencing Entrepreneurial Intention of University Students in Yemen: The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehdi, S.A.; Singh, L.B. Linking Entrepreneurial Orientation Dimensions to Entrepreneurial Intention: Role of Openness to Experience as a Mediating Variable. In Transformation for Sustainable Business and Management Practices: Exploring the Spectrum of Industry 5.0; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, K.; Ghosh, A. Personal Antecedents of Entrepreneurial Intention: A Perceptual Study on Generation Z Girls. Small Enterp. Dev. Manag. Ext. J. 2023, 50, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laouiti, R.; Haddoud, M.Y.; Nakara, W.A.; Onjewu, A.-K.E. A Gender-Based Approach to the Influence of Personality Traits on Entrepreneurial Intention. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.L. Making Vocational Choices: A Theory of Vocational Personalities and Work Environments; Psychological Assessment Resources: Lutz, FL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cattell, R.B. The Description of Personality: Basic Traits Resolved into Clusters. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1943, 38, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, G.W. Personality: A Psychological Interpretation; Constable & Co. Ltd.: London, UK, 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Seibert, S.E.; Hills, G.E. The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy in the Development of Entrepreneurial Intentions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Seibert, S.E.; Lumpkin, G.T. The Relationship of Personality to Entrepreneurial Intentions and Performance: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 381–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliendo, M.; Fossen, F.; Kritikos, A.S. Personality Characteristics and the Decisions to Become and Stay Self-Employed. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 42, 787–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, O.P.; Srivastava, S. The Big-Five Trait Taxonomy: History, Measurement, and Theoretical Perspectives. In Handbook of Personality; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, D.W. Consistency of the Factorial Structures of Personality Ratings from Different Sources. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1949, 44, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digman, J.M. Personality Structure: Emergence of the Five-Factor Model. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1990, 41, 417–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basyith, A.; Idris, M. The Gender Effect on Small Business Enterprises’ Firm Performance: Evidence from Indonesia. Indian J. Econ. Bus. 2014, 13, 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Marlow, S.; McAdam, M. Gender and Entrepreneurship: Advancing Debate and Challenging Myths; Exploring the Mystery of the under-Performing Female Entrepreneur. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2013, 19, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Envick, B.R. Gender and Entrepreneurial Orientation: A Multi-Country Study. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2013, 9, 465–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dajani, H.; Marlow, S. Impact of Women’s Home-Based Enterprise on Family Dynamics: Evidence from Jordan. Int. Small Bus. J. 2010, 28, 470–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D. Constraints and Opportunities Facing Women Entrepreneurs in Developing Countries: A Relational Perspective. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2009, 24, 232–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruin, A.; Brush, C.G.; Welter, F. Advancing a Framework for Coherent Research on Women’s Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2007, 31, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Goktan, A.B.; Gunay, G. Gender Differences in Evaluation of New Business Opportunity: A Stereotype Threat Perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowiński, W.; Haddoud, M.Y.; Lančarič, D.; Egerová, D.; Czeglédi, C. The Impact of Entrepreneurship Education, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Gender on Entrepreneurial Intentions of University Students in the Visegrad Countries. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, D.; Singer, S.; Herrington, M. 16 Global Report. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor; Global Entrepreneurship Research Association: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.M.; Sardeshmukh, S.R.; Combs, G.M. Understanding Gender, Creativity, and Entrepreneurial Intentions. Educ. Train. 2016, 58, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, D.; Rahman, N. Effects of Entrepreneurial Orientation on Start-up Success: A Gender Perspective. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2018, 8, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Paray, Z.A.; Dwivedi, A.K. Student’s Entrepreneurial Orientation and Intentions: A Study across Gender, Academic Background, and Regions. High. Educ. Ski. Work. Based Learn. 2020, 11, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoncic, B. The Entrepreneur’s General Personality Traits and Technological Developments. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Eng. 2009, 53, 236–241. [Google Scholar]

- Orhan, M.; Scott, D. Why Women Enter into Entrepreneurship: An Explanatory Model. Women Manag. Rev. 2001, 16, 232–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Núñez, M.I.; Rubio-Valdehita, S.; Aparicio-García, M.E.; Díaz-Ramiro, E.M. Are Entrepreneurs Born or Made? The Influence of Personality. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 154, 109699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Biemans, H.J.; Naderi Mahdei, K.; Lans, T.; Chizari, M.; Mulder, M. Testing the Relationship between Personality Characteristics, Contextual Factors and Entrepreneurial Intentions in a Developing Country. Int. J. Psychol. 2017, 52, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoncic, B.; Bratkovic Kregar, T.; Singh, G.; DeNoble, A.F. The Big Five Personality–Entrepreneurship Relationship: Evidence from Slovenia. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 819–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obschonka, M.; Schmitt-Rodermund, E.; Terracciano, A. Personality and the Gender Gap in Self-Employment: A Multi-Nation Study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, R.; Newby, R.; Tant, K.; Trepongkaruna, S. Overconfidence, Overreaction and Personality. Rev. Behav. Financ. 2013, 5, 104–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, R.B.; Newby, R.; Sanghani, J. An Intimate Portrait of the Individual Investor. J. Behav. Financ. 2008, 9, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fietze, S.; Boyd, B. Entrepreneurial Intention of Danish Students: A Correspondence Analysis. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 656–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behaviour: Reactions and Reflections. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.-H.; Wang, Y.-S.; Hsu, J.-W.; Lin, S. Predicting Individuals’ Digital Autopreneurship: Does Educational Intervention Matter? J. Bus. Res. 2020, 106, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leutner, F.; Ahmetoglu, G.; Akhtar, R.; Chamorro-Premuzic, T. The Relationship between the Entrepreneurial Personality and the Big Five Personality Traits. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2014, 63, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espíritu-Olmos, R.; Sastre-Castillo, M.A. Personality Traits versus Work Values: Comparing Psychological Theories on Entrepreneurial Intention. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1595–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ness, R.K.; Seifert, C.F. A Theoretical Analysis of the Role of Characteristics in Entrepreneurial Propensity. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2016, 10, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crant, J.M. The Proactive Personality Scale as a Predictor of Entrepreneurial Intentions. J. Small Bus. Manag. 1996, 34, 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Pak, O.; Mahmood, M. Impact of Personality on Risk Tolerance and Investment Decisions: A Study on Potential Investors of Kazakhstan. Int. J. Commer. Manag. 2015, 25, 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Sharma, D.; Behl, A.; Tiwari, A.K. Investor Personality as a Predictor of Investment Intention–Mediating Role of Overconfidence Bias and Financial Literacy. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Bajwa, S.U.; Shahzad, K.; Aslam, H. Exploring Big Five Personality Traits and Gender as Predictors of Entrepreneurs’ Cognitive Adaptability. J. Model. Manag. 2017, 12, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Venkataraman, S. The Promise of Entrepreneurship as a Field of Research. AMR 2000, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.J.; Raposo, M.L.; Rodrigues, R.G.; Dinis, A.; Do Paco, A. A Model of Entrepreneurial Intention: An Application of the Psychological and Behavioral Approaches. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2012, 19, 424–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.H.; Statman, M. Investor Personality in Investor Questionnaires. J. Invest. Consult. 2013, 14, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI); Psychological Assessment Resources: Lutz, FL, USA, 1989; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Vedel, A. Big Five Personality Group Differences across Academic Majors: A Systematic Review. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 92, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, R.; Denissen, J.J.; Allemand, M.; Penke, L. Age and Gender Differences in Motivational Manifestations of the Big Five from Age 16 to 60. Dev. Psychol. 2013, 49, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisberg, Y.J.; Deyoung, C.G.; Hirsh, J.B. Gender Differences in Personality across the Ten Aspects of the Big Five. Front. Psychol. 2011, 2, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Envick, B.R.; Langford, M. The Big-Five Personality Model: Comparing Male and Female Entrepreneurs. Acad. Entrep. J. 2003, 9, 140480863. [Google Scholar]

- Rahafar, A.; Castellana, I.; Randler, C.; Antúnez, J.M. Conscientiousness but Not Agreeableness Mediates Females’ Tendency toward Being a Morning Person. Scand. J. Psychol. 2017, 58, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olakitan, O.O.; Ayobami, A.P. An Investigation of Personality on Entrepreneurial Success. J. Emerg. Trends Econ. Manag. Sci. 2011, 2, 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Choukir, J.; Aloulou, W.J.; Ayadi, F.; Mseddi, S. Influences of Role Models and Gender on Saudi Arabian Freshman Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2019, 11, 186–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.H.; Koo, T.Y.; Wu, G.S.; Yu, T.K. Construction of the Behavioral Tendency Model of Tourist in Kinmen. J. Manag. 2004, 21, 131–151. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, R.; Owens, M.; Goodyer, I. Item Response Theory and Validity of the NEO-FFI in Adolescents. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 53, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fruyt, F.; De Bolle, M.; McCrae, R.R.; Terracciano, A.; Costa, P.T. Assessing the Universal Structure of Personality in Early Adolescence: The NEO-PI-R and NEO-PI-3 in 24 Cultures. Assessment 2009, 16, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.I.; Tseng, H.M.; Li, I.C.; Yu, C.S. International English Big-Five Mini-Markers: Development of the traditional Chinese version. J. Manag. 2011, 28, 579–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory 3E; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hair Jr, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hundleby, J.D.; Nunnally, J. Psychometric Theory 3E; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Tabri, N.; Elliott, C.M. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Can. Grad. J. Sociol. Criminol. 2012, 1, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leguina, A. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2015, 38, 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kono, S.; Sato, M. The potentials of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in leisure research. J. Leis. Res. 2022, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach to Structural Equation Modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Wetzels, M.; Odekerken-Schröder, G.; Van Oppen, C. Using PLS Path Modeling for Assessing Hierarchical Construct Models: Guidelines and Empirical Illustration. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in International Marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Gharbi, H.; Sobaih, A.E.E.; Aliane, N.; Almubarak, A. The Role of Innovation Capacities in the Relationship between Green Human Resource Management and Competitive Advantage in the Saudi Food Industry: Does Gender of Entrepreneurs Really Matter? Agriculture 2022, 12, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).