Abstract

Background: This study aimed to identify the baseline characteristics predictive of Psoriasis Area and Sensitivity Index (PASI) 90 response to guselkumab and assess treatment effectiveness outcomes for PASI 90 responders and PASI 90 non-responders. Methods: This post hoc analysis used data from a prospective, multicenter, observational study of guselkumab in Korean patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis conducted between February 2019 and March 2022. Stepwise logistic regression analysis was used to identify baseline characteristics predictive of PASI 90 response. Results: Of 339 patients, 245 (72.3%) week-28 PASI 90 responders and 94 (27.7%) non-responders were identified. Baseline characteristics significantly predictive of PASI 90 response in multivariate logistic regression were absence of family history of psoriasis (odds ratio [OR]: 0.35; p = 0.0266), higher PASI score (OR: 1.22; p = 0.0006), higher body surface area of psoriasis involvement (OR: 0.95; p = 0.0127), prior phototherapy use (OR: 2.44; p = 0.0108), and reduced concomitant topical agent use (OR: 0.41; p = 0.0044). More PASI 90 responders versus non-responders achieved absolute PASI score ≤ 2 by week 44 (95.8% vs. 67.5%) and Dermatology Life Quality Index scores of 0 or 1 by week 28 (72.2% vs. 34.0%). Conclusions: Guselkumab PASI 90 responders had unique baseline characteristics that may predict positive treatment outcomes.

1. Introduction

Plaque psoriasis is a chronic immune-mediated disease that causes excessive keratinocyte proliferation, resulting in erythematous, pruritic, and/or painful scaly skin lesions that can significantly impact patient quality of life (QoL) [1,2,3,4,5]. The introduction of biologic agents that target the aberrant proinflammatory cytokine signaling pathways driving the clinical features of plaque psoriasis has improved both skin clearance and QoL outcomes for patients [6,7,8,9,10,11].

Guselkumab (TREMFYA®) is a fully human immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody that binds the p19 subunit of interleukin-23 (IL-23). Guselkumab-mediated inactivation of the IL-23 receptor inhibits the downstream signaling pathways and expansion and survival of T helper 17 cells and other immune cells that express IL-23 receptor; consequently, release of proinflammatory cytokines that promote inflammation and keratinocyte proliferation is suppressed [7,8,12]. Additionally, the native Fc region of guselkumab binds to CD64, a receptor expressed on IL-23-producing myeloid cells, and thereby guselkumab neutralizes IL-23 at the source of production and removes IL-23 from the inflamed tissue microenvironment [13,14]. Two multicenter phase 3 trials (VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2) in moderate-to-severe psoriasis demonstrated that guselkumab was well tolerated, had superior efficacy versus adalimumab, and significantly improved patient-reported outcomes, including QoL [7,8]. The VOYAGE studies supported regulatory approval of guselkumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in multiple countries across North America, Europe, and Asia [15,16,17,18].

While most patients treated with guselkumab demonstrate substantial improvements in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score from baseline with long-term therapy, a proportion of individuals achieve ≥90% improvement in symptoms (PASI 90 response) at week 28 of guselkumab treatment [2,19,20]. Identification of baseline demographics or clinical characteristics that are associated with PASI 90 response to guselkumab may be informative for therapeutic decision-making and allow healthcare professionals to tailor treatment strategies for specific patients [2]. In addition, the overall prevalence of plaque psoriasis in Asian populations is lower than that in European or North American populations [21], suggesting that Asian patients may have unique genetic, demographic, or clinical characteristics driving disease pathogenesis [22], which may impact response to guselkumab treatment.

A recent post-marketing surveillance study evaluating the safety and efficacy of guselkumab in Korean patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis offers an overview of the effectiveness of guselkumab in Asian patients in a representative real-world setting [23]. This post hoc analysis aimed to identify baseline characteristics predictive of PASI 90 response to guselkumab and assess treatment effectiveness outcomes for PASI 90 responder and PASI 90 non-responder cohorts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients

A prospective, multicenter, observational, post-marketing surveillance study was conducted at 44 clinical centers in South Korea between 25 February 2019 and 25 March 2022, to assess the safety and efficacy of guselkumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis [23]. Eligible patients were those who met requirements for biologic treatment of plaque psoriasis in South Korea and received guselkumab according to the product label during routine clinical practice [16]. Participating centers enrolled patients consecutively during routine clinic visits to minimize selection bias. Guselkumab was administered by subcutaneous injection at the recommended dose of 100 mg at weeks 0 and 4, followed by 100 mg every 8 weeks thereafter [16]. Patients were followed through 44 weeks for evaluation of treatment effectiveness. Here, we report results from a post hoc comparative analysis.

2.2. Data Sources and Data Collection

The primary data sources were the medical records for each individual participating in the study. All data were entered into case report forms. The frequency and timing of patient clinical assessments were in accordance with clinical guidelines. Demographic and clinical characteristics, including disease history, presence of comorbidities, and prior treatments, were collected at baseline (week 0). Guselkumab administration status, concomitant medications, measures of treatment effectiveness (PASI score, body surface area [BSA], Investigator’s Global Assessment [IGA] score), and patient-reported outcome measures (Dermatology Life Quality Index [DLQI]) were collected at baseline (week 0), week 4, and approximately every 8 weeks thereafter (weeks 12–44).

As this was a real-world study, treatment administration and patient visits may not have occurred precisely at every 4- or 8-week interval as per guselkumab label guidance. Despite this, most patients received treatment and were clinically assessed by healthcare professionals within ±2 weeks of the label-defined treatment intervals.

2.3. Post Hoc Study Population and Definitions

In this post hoc analysis, patients with PASI scores recorded at baseline and week 28 were selected from the overall study population (N = 339). Two patient cohorts were identified: guselkumab PASI 90 responders and PASI 90 non-responders, based on assessment at week 28 of treatment.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

This study analyzed all collected variables using descriptive statistics, without a specific hypothesis. Descriptive statistics for continuous variables are presented as mean with standard deviation or median values, and categorical variables are presented as percentage of occurrence within the patient sample. Baseline demographics (patient sex, age at study entry, and body mass index [BMI]), medical history including comorbidities (smoker status; alcohol use; and presence of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, impaired glucose regulation, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, autoimmune thyroiditis/hypothyroidism/hyperthyroidism, inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune rheumatic disease, uveitis, malignancy, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, psychiatric disorders, and palmoplantar pustulosis), and disease characteristics (family history of psoriasis, disease duration, PASI score, total BSA and body areas impacted, IGA score, presence of psoriatic arthropathy, number and type of prior treatments, and concomitant treatments) were compared between the PASI 90 responder and PASI 90 non-responder cohorts. Treatment effectiveness outcomes over the 44-week study period, including the proportion of patients achieving an absolute PASI score ≤ 2 (aPASI2), a DLQI score of 0 or 1 (DLQI 0/1), PASI 75, PASI 90, PASI 100, and an absolute PASI score ≤ 1 (aPASI1), were compared between the PASI 90 responder and PASI 90 non-responder cohorts. Additionally, the time to absolute PASI score of 0 (aPASI0) was analyzed by Kaplan–Meier for both guselkumab PASI 90 responder and PASI 90 non-responder cohorts.

In an exploratory statistical comparison, continuous variables were analyzed, where appropriate, using the Wilcoxon rank sum and t-test, while categorical variables were assessed using Pearson’s chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test. Imputation of missing data was not performed. In addition, logistic regression analysis was conducted to investigate potential baseline variables affecting achievement of PASI 90 at week 28. Variables with a p-value < 0.1 from the univariate logistic regression analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis. For exploratory purposes, all statistical analyses were performed using 2-sided tests and results with p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using the statistical software package SAS 9.4 (Statistical Analysis System, SAS-Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

2.5. Ethical Considerations

This observational study was conducted in accordance with the International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices. The protocol and patient informed consent form were approved by the local institutional review board at all participating clinical sites (Supplemental Table S1). All patients provided written informed consent before participation in the study and could withdraw at any time.

3. Results

3.1. Patients

A total of 339 patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis treated with guselkumab were included in this post hoc analysis. Among them, 245 (72.3%) were PASI 90 responders, and 94 (27.7%) were PASI 90 non-responders at week 28. The median duration of guselkumab treatment was 316 days for both cohorts.

3.2. Baseline Demographics, Medical History, and Disease Characteristics

Baseline demographics and medical history for guselkumab PASI 90 responders and PASI 90 non-responders are shown in Table 1. PASI 90 non-responders were slightly older than PASI 90 responders (44.5 years vs. 42.0 years); however, this difference was not statistically significant. While median BMI did not significantly differ between cohorts, PASI 90 non-responders had a marginally higher BMI at baseline (26.2 kg/m2 vs. 25.3 kg/m2). A significant difference was observed between cohorts for smoking status, with a higher proportion of PASI 90 responders reporting that they had never smoked (p = 0.042). Alcohol use and other baseline characteristics were comparable between PASI 90 responders and PASI 90 non-responders.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and medical history of PASI 90 responders and PASI 90 non-responders.

PASI 90 non-responders presented with more comorbid conditions at baseline than PASI 90 responders (Table 1). Notably, the prevalence of diabetes mellitus (10.6% vs. 4.1%, p = 0.0218) and hypertension (17.0% vs. 8.6%, p = 0.0255) was significantly higher among PASI 90 non-responders. Although not statistically significant, PASI 90 non-responders also had higher incidences of cardiovascular disease (2.1% vs. 0.8%, p = 0.3081), rheumatic autoimmune disease (12.8% vs. 9.4%, p = 0.3601), non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (1.1% vs. 0%, p = 0.2773), and psychiatric disorders (3.2% vs. 0.4%, p = 0.0664) than PASI 90 responders. The incidence of other comorbidities was not significantly different between the cohorts.

Significant differences in several baseline disease characteristics were noted between cohorts (Table 2). Compared with PASI 90 non-responders, PASI 90 responders had significantly shorter median disease duration (85.3 months vs. 125.4 months; p = 0.0162) and were significantly more likely to have no family history of plaque psoriasis (93.3% vs. 84.9%, p = 0.0182). Interestingly, PASI 90 responders exhibited significantly higher mean baseline PASI scores (16.7 vs. 13.8, p < 0.0001) and greater total BSA of psoriasis involvement (22.4% vs. 19.3%, p = 0.0108) compared with PASI 90 non-responders. Based on IGA score, a higher proportion of PASI 90 responders had moderate disease at baseline than PASI 90 non-responders (59.5% vs. 31.4%, p = 0.0034).

Table 2.

Baseline disease characteristics of PASI 90 responders and PASI 90 non-responders.

Regarding prior treatments, PASI 90 responders had higher usage rates of topical agents, phototherapy, and systemic oral agents than PASI 90 non-responders. Significant differences were noted for topical agents (67.3% vs. 50.0%, p = 0.0031) and methotrexate (50.2% vs. 36.2%, p = 0.0204). Although not statistically significant, a lower proportion of PASI 90 responders had previous exposure to biologics (16.7% vs. 20.2%, p = 0.4526) compared with PASI 90 non-responders. Concomitant treatment use was generally similar between cohorts; however, significantly fewer PASI 90 responders reported concomitant use of topical agents during guselkumab treatment (36.3% vs. 66.0%, p < 0.0001).

3.3. Predictors of PASI 90 Response to Guselkumab at Week 28

The demographic, medical history, and disease characteristics found to be significant in the univariate analysis (such as female sex; age; smoking status; family history of psoriasis; psoriasis disease duration; psoriasis of the back of the foot; comorbidities including presence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and psychiatric disorders; as well as baseline PASI and BSA scores; prior phototherapy or topical agent use; and concomitant topical agent use) were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 3). In the multivariate analysis, significant predictors of PASI 90 response to guselkumab included absence of family history of psoriasis (odds ratio [OR]: 0.35; 95% confidence interval [95% CI]: 0.135–0.884; p = 0.0266), higher baseline PASI score (OR: 1.22; 95% CI: 1.089–1.367; p = 0.0006), higher baseline BSA of psoriasis involvement (OR: 0.95; 95% CI: 0.908–0.989; p = 0.0127), prior phototherapy use (OR: 2.44; 95% CI: 1.229–4.858; p = 0.0108), and reduced concomitant topical agent use (OR: 0.41; 95% CI: 0.222–0.756; p = 0.0044) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses identifying baseline characteristics predictive of PASI 90 response to guselkumab.

3.4. Guselkumab Treatment Effectiveness Outcomes

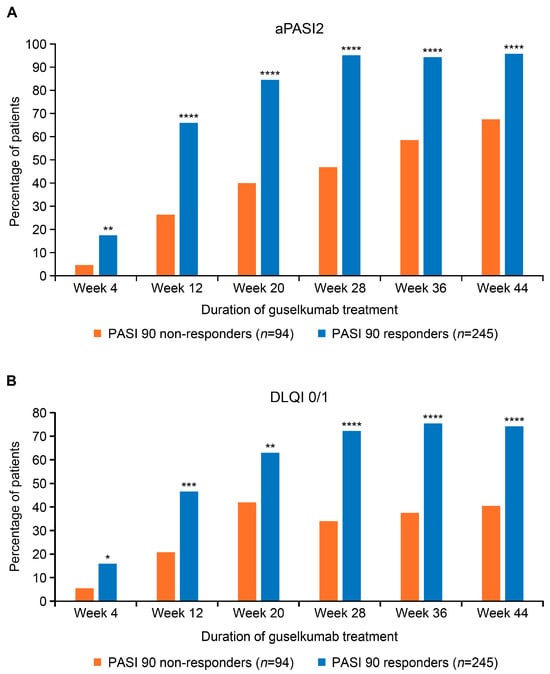

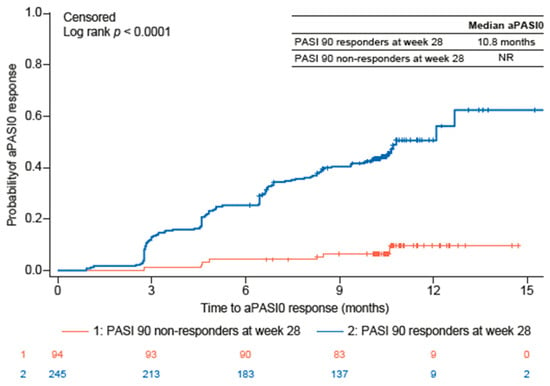

Over the 44-week study period, a significantly higher proportion of guselkumab PASI 90 responders than PASI 90 non-responders also achieved aPASI2 at all timepoints evaluated (Figure 1A). By week 4, 17.3% of PASI 90 responders and 4.6% of PASI 90 non-responders achieved aPASI2. By week 20, 84.5% of PASI 90 responders achieved aPASI2, with nearly all of these responders (95.8%) reaching aPASI2 by week 44. In contrast, only 40.0% of PASI 90 non-responders achieved aPASI2 by week 20, increasing to 67.5% by week 44. Similarly, a significantly greater proportion of PASI 90 responders attained DLQI 0/1 at all timepoints (Figure 1B). The difference was particularly notable at week 28 (72.2% vs. 34.0%, p < 0.0001), week 36 (75.4% vs. 37.5%, p < 0.0001), and week 44 (74.2% vs. 40.5%, p = 0.0001). Analyses of PASI 75, PASI 90, PASI 100, and aPASI1 over time showed a similar trend, with a greater proportion of PASI 90 responders achieving response at most timepoints than PASI 90 non-responders (Supplemental Figure S1). The median time to achieve aPASI0 was substantially shorter for PASI 90 responders (10.8 months) compared with PASI 90 non-responders, for whom the median time was not reached (Figure 2). By week 44, 45.7% of PASI 90 responders and 7.4% of PASI 90 non-responders achieved aPASI0.

Figure 1.

Proportion of guselkumab PASI 90 responders and PASI 90 non-responders achieving aPASI2 (A) and DLQI 0/1 (B) across the duration of treatment. PASI score of 0 indicates no psoriasis; PASI score > 10 is consistent with severe psoriasis. Lower DLQI scores (0–1) represent no impact on patient’s life; high scores (21–30) represent an extremely large impact on patient’s life. * Denotes p-value < 0.05; ** denotes p-value < 0.01; *** denotes p-value < 0.001; **** denotes p-value < 0.0001. aPASI2, absolute Psoriasis Activity Severity Index score of ≤2; DLQI 0/1, Dermatology Life Quality Index score of 0 or 1; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index.

Figure 2.

Time to aPASI0 for guselkumab PASI 90 responders and PASI 90 non-responders. aPASI0, absolute Psoriasis Activity Severity Index score of 0; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; NR, not reached.

4. Discussion

In this study of Korean patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis treated with guselkumab in a real-world setting, approximately 72% of patients achieved a PASI 90 response by week 28, indicating a substantial reduction in disease severity. Interestingly, PASI 90 responders were more likely to present with higher baseline PASI and BSA scores. Key baseline characteristics significantly predictive of a PASI 90 response versus a PASI 90 non-response included shorter disease duration and fewer comorbidities, underscoring the importance of early intervention and comprehensive patient assessment to optimize treatment outcomes with guselkumab. Notably, we observed that patients who were PASI 90 responders at week 28 had consistently good outcomes over the 44-week treatment period. Over 45% of PASI 90 responders achieved complete skin clearance (aPASI0) with guselkumab across the duration of treatment. PASI 90 responders maintained their therapeutic gains, with 95.8% achieving an absolute PASI score ≤ 2 by week 44, compared with 67.5% of PASI 90 non-responders. Furthermore, QoL improvements were substantial, with 72.2% of PASI 90 responders attaining a DLQI score of 0 or 1 by week 28, compared with 34.0% of PASI 90 non-responders.

Differences in treatment response observed between patients in this study are not unique to guselkumab and are evident across the spectrum of biologics used to treat psoriasis, with varying patient characteristics reported to be associated with better response depending on the biologic. Reports based on multiple real-world studies have identified factors that may be associated with, or predictive of, response to biologic treatments in patients with psoriasis; however, the variables reported as statistically significant are inconsistent between studies, likely due to differences in study design, patient populations, and treatment strategies. In line with the data presented from this analysis, several reports indicate that higher baseline PASI scores may be associated with a good response to biologics [24,25]. Findings from one Chinese study suggested that patients with a super response to adalimumab (those who achieved PASI 100 at week 12 and at either week 24 or 32) had a higher PASI score at baseline than those who achieved a non-super response, although the difference was not significant [24]. Additionally, a study conducted in Denmark indicated that the odds of achieving PASI 90 after biologic treatment for 3 or 6 months were significantly higher in biologic-naïve patients with a higher baseline PASI score [25]. Despite this, and in contrast with the results presented here, the Danish study also reported that those patients who used concomitant local treatment with their biologic had increased odds of achieving PASI 90 after 3 or 6 months of treatment; however, it was unclear what comprised local treatment (i.e., topical agents and/or phototherapy) [25]. Other studies, including the PSO-BIO-REAL study (n = 846) and the IMMerge study (n = 327), have also reported that biologic-naïve patients were more likely to achieve PASI 90 [26,27]; however, the current study found no significant differences in previous biologic use between PASI 90 responders and PASI 90 non-responders.

Consistent with the data presented here, many real-world studies investigating the variables associated with treatment response to biologics targeting IL-17 and IL-23 suggest limited associations between patient sex, BMI, or previous biologic exposure and achievement of PASI 90 (though, as noted previously, some studies did find that biologic-naïve patients were more likely to achieve PASI 90 response) [27,28,29,30,31,32]. Several studies have reported that patients without obesity or diabetes mellitus at baseline generally have a better treatment response [33]. It has been suggested that this may be due to patients having an overall lower systemic inflammatory burden at baseline; however, further studies are required to confirm this hypothesis. While the current study indicates that a significantly lower proportion of PASI 90 responders had diabetes mellitus at baseline versus PASI 90 non-responders, this was not found to be a significant predictor of response to guselkumab in the multivariate logistic regression analysis. Similarly, hypertension and several other baseline characteristics showed association with PASI 90 response in the univariate logistic regression but were not significant in the multivariate logistic regression. These variables likely represent potential confounders that had been adjusted for in the multivariate analysis.

Another factor that may represent a robust significant predictor of PASI 90 response to biologics is the absence of nail psoriasis [34,35,36]. Data from previous studies indicate that patients without nail psoriasis who are treated with biologics are twice as likely to achieve complete skin clearance after 12 months of treatment than those with psoriatic nail involvement [35]. Together with nail psoriasis, the absence of hypertension at baseline was also identified as a significant predictor of good treatment response to biologics [35]. In the current study, lower proportions of PASI 90 responders had nail involvement (18.8% vs. 24.5%, respectively) and hypertension (8.6% vs. 17.0%, respectively) than PASI 90 non-responders at baseline, suggesting a similar trend with other studies, although this was not a significant predictor of guselkumab response. Interestingly, patients who present with nail psoriasis also typically have a longer disease duration than those without nail involvement [34,36]. Of note, findings from our real-world study indicate that PASI 90 responders had significantly shorter disease duration at baseline than PASI 90 non-responders. These data are consistent with the GUIDE study, which reported that patients with short disease duration were more likely to be guselkumab PASI 100 responders (defined as achievement of 100% improvement in PASI score at both weeks 20 and 28 of guselkumab treatment) than those with long disease duration [36].

The real-world findings presented here differ from a post hoc analysis of pooled patient data from the VOYAGE 1 and 2 randomized controlled studies. The VOYAGE studies demonstrated that baseline factors significantly associated with guselkumab PASI 100 response were younger age, less severe disease (including the absence of nail psoriasis), lower BMI, and lower PASI and IGA scores [2]. None of these factors were significant predictors of PASI 90 response in the current study. Notably, the current study suggests that a higher baseline PASI score, rather than a lower baseline PASI score, is predictive of PASI 90 response. The differences in the results between these studies may be due to several factors. While both were post hoc analyses, the current study used data from a real-world clinical setting in Korea whereas the VOYAGE 1 and 2 studies utilized clinical trial data from a patient population subjected to strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. Additionally, patient ethnicity may represent a confounding variable for factors that may significantly predict super response; the majority (~85%) of patients in the VOYAGE trials were White [2], whereas all participants in the current study were Asian. Furthermore, the post hoc analysis of the VOYAGE studies evaluated a cohort comprised specifically of PASI 100 responders, whereas the current study analyzed patients categorized as PASI 90 responders, with PASI 100 responders included in this broader cohort. Patients who achieve PASI 100 response to guselkumab constitute a discrete population of patients and, as such, may have unique baseline characteristics that influence treatment response.

The current study has several limitations that require consideration. The non-randomized observational design of the study, with no comparator or control arm, limits the robustness of the evidence. This was a post hoc analysis of an observational study and was not specifically designed for statistical comparisons between PASI 90 responder and PASI 90 non-responder patient cohorts. Given the exploratory nature of this post hoc analysis, the results are intended to describe observed associations rather than to support formal hypothesis testing. Despite utilizing data from 44 clinical centers, the overall sample size was small, and the majority of patients included in this analysis were male. Patients with PASI scores recorded at baseline and week 28 were included, which may have resulted in selection bias towards patients who stayed well and remained on the study. Further studies using larger patient cohorts are required to examine and validate factors that may impact guselkumab treatment response. In addition, due to the observational nature of the study, data were missing for certain variables such as BMI, DLQI, and IGA in a proportion of patients, which might have had an impact on the analysis results. The results generated from the stepwise logistic regression should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating, which warrant further investigation in prospective clinical studies. No causal relationship could be made based on logistic regression analysis, and certain predictors for PASI 90 response, such prior phototherapy use and reduced concomitant topical agent use, might reflect treatment patterns in responders versus non-responders.

Identification of patients who are likely to achieve PASI 90 response to guselkumab treatment, as well as those who may prove to be non-responders, may allow for optimization of treatment strategies and improve long-term patient outcomes, including complete skin clearance. The typical trial and error approach to determine whether individual patients may achieve a desirable response to biologic treatments has been shown to impact patient QoL. A recent study from Korea indicated that up to 21.6% of patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis switched from their initial biologic agent to a second biologic agent due to a lack of efficacy [37]; however, treatment switching in an attempt to improve therapeutic response was reported to pose a significant burden for patients [38]. Additionally, patients treated with therapies that demonstrate limited efficacy in terms of PASI response report poorer DLQI and mental health scores than those who achieve complete skin clearance [39,40]. These data underscore the importance of early and effective treatment interventions that are tailored to the individual patient to improve both long-term clinical and QoL outcomes.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, data from this post-marketing study of patients who received guselkumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in Korea indicate that PASI 90 responders to guselkumab have unique baseline characteristics that may predict treatment efficacy. Disease duration was significantly shorter for PASI 90 responders compared with PASI 90 non-responders, suggesting an association between early intervention and better treatment outcomes. Guselkumab treatment effectiveness outcomes were consistently good for PASI 90 responders, with most reporting substantial improvements in QoL over the 44-week treatment period. The baseline characteristics predictive of response to guselkumab identified in this study are hypothesis-generating, warranting confirmation in future studies, which may optimize treatment decision-making and facilitate selection of tailored treatment strategies to improve skin clearance outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm15020704/s1, Table S1: List of institutional review boards (IRBs); Figure S1: Proportion of guselkumab PASI 90 responders and PASI 90 non-responders achieving PASI 75 (A), PASI 90 (B), PASI 100 (C), and aPASI1 (D) across the duration of treatment.

Author Contributions

Investigation, Y.B.L., B.S.S., M.K., M.K.S., S.W.Y., J.Y.L., C.W.K., G.-Y.L., K.H.K., K.J.K., D.H.K. and S.W.S.; Writing—original draft, Y.B.L. and J.A.; Writing—review and editing, Y.B.L., B.S.S., M.K., M.K.S., S.W.Y., J.Y.L., C.W.K., G.-Y.L., K.H.K., K.J.K., D.H.K., S.W.S. and J.A.; Formal analysis, Y.K. and J.A.; Software, Y.K.; Visualization, Y.K.; Supervision, S.W.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded and supported by Janssen Korea Ltd., project number CNTO1959PSO4003.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The protocol and any amendments, and the patient informed consent form, were approved by the local institutional review board/independent ethics committee at participating sites (Supplemental Table S1).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The de-identified datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by Laura Graham, Parexel in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP) guidelines and funded by Janssen Korea Ltd.

Conflicts of Interest

J.A. and Y.K. are employees of Johnson & Johnson. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| aPASI | Absolute Psoriasis Area and Sensitivity Index |

| aPASI0 | Absolute Psoriasis Activity Severity Index score of 0 |

| aPASI1 | Absolute Psoriasis Activity Severity Index score of ≤1 |

| aPASI2 | Absolute Psoriasis Activity Severity Index score of ≤2 |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| BSA | Body surface area |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| DLQI | Dermatology Life Quality Index |

| DLQI 0/1 | Dermatology Life Quality Index score of 0 or 1 |

| IGA | Investigator’s Global Assessment |

| IL | Interleukin |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| PASI | Psoriasis Area and Sensitivity Index |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| SD | Standard deviation |

References

- Bolick, N.L.; Ghamrawi, R.I.; Feldman, S.R. Management of plaque psoriasis: A review and comparison of IL-23 inhibitors. EMJ Dermatol. 2020, 8, 84–95. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, K.; Gordon, K.B.; Strober, B.; Langley, R.G.; Miller, M.; Yang, Y.W.; Shen, Y.K.; You, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Foley, P.; et al. Super-response to guselkumab treatment in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: Age, body weight, baseline Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, and baseline Investigator’s Global Assessment scores predict complete skin clearance. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, 2393–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korman, N.J.; Zhao, Y.; Pike, J.; Roberts, J.; Sullivan, E. Increased severity of itching, pain, and scaling in psoriasis patients is associated with increased disease severity, reduced quality of life, and reduced work productivity. Dermatol. Online J. 2015, 21, 13030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A.; Bohannan, B.; Mburu, S.; Alarcon, I.; Kasparek, T.; Toumi, J.; Frade, S.; Barrio, S.F.; Augustin, M. Impact of psoriatic disease on quality of life: Interim results of a global survey. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 12, 1055–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, C.E.M.; Jo, S.J.; Naldi, L.; Romiti, R.; Guevara-Sangines, E.; Howe, T.; Pietri, G.; Gilloteau, I.; Richardson, C.; Tian, H.; et al. A multidimensional assessment of the burden of psoriasis: Results from a multinational dermatologist and patient survey. Br. J. Dermatol. 2018, 179, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blauvelt, A.; Wu, J.J.; Armstrong, A.; Menter, A.; Liu, C.; Jacobson, A. Importance of complete skin clearance in psoriasis as a treatment goal: Implications for patient-reported outcomes. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2020, 19, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blauvelt, A.; Papp, K.A.; Griffiths, C.E.; Randazzo, B.; Wasfi, Y.; Shen, Y.K.; Li, S.; Kimball, A.B. Efficacy and safety of gusel-kumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the continuous treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: Results from the phase III, double-blinded, placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE 1 trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 76, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, K.; Armstrong, A.W.; Foley, P.; Song, M.; Wasfi, Y.; Randazzo, B.; Li, S.; Shen, Y.K.; Gordon, K.B. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with randomized withdrawal and retreatment: Results from the phase III, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE 2 trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 76, 418–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, C.; Langley, R.G.; Papp, K.; Tyring, S.K.; Wasel, N.; Vender, R.; Unnebrink, K.; Gupta, S.R.; Valdecantos, W.C.; Bagel, J. Adalimumab for treatment of moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis of the hands and feet: Efficacy and safety results from REACH, a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Arch. Dermatol. 2011, 147, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, K.A.; Langley, R.G.; Lebwohl, M.; Krueger, G.G.; Szapary, P.; Yeilding, N.; Guzzo, C.; Hsu, M.-C.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriasis: 52-week results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (PHOENIX 2). Lancet 2008, 371, 1675–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, R.G.; Elewski, B.E.; Lebwohl, M.; Reich, K.; Griffiths, C.E.M.; Papp, K.; Puig, L.; Nakagawa, H.; Spelman, L.; Sigurgeirsson, B.; et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis—Results of two phase 3 trials. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, Y.; Cui, L.; Shi, Y.; Guo, C. Advances in the pathogenesis of psoriasis: From keratinocyte perspective. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atreya, R.; Abreu, M.T.; Krueger, J.G.; Eyerich, K.; Sachen, K.; Greving, C.; Hammaker, D.; Bao, P.; Lacy, E.; Sarabia, I.; et al. P504 guselkumab, an IL-23p19 subunit–specific monoclonal antibody, binds CD64+ myeloid cells and potently neutralises IL-23 produced from the same cells. J. Crohns Colitis 2023, 17, i634–i635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGonagle, D.; Atreya, R.; Abreu, M.; Krueger, J.; Eyerich, K.; Sachen, K.; Greving, C.; Hammaker, D.; Bao, P.; Lacy, E.; et al. POS1531 guselkumab, an IL-23P19 subunit–specific monoclonal antibody, binds CD64+ myeloid cells and potently neutralises IL-23 produced from the same cells. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 82, 1128–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Tremfya Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/tremfya-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. Trempier Prefilled Syringe (Guselkumab, Genetically Modified). Available online: https://nedrug.mfds.go.kr/pbp/CCBBB01/getItemDetailCache?cacheSeq=201801604aupdateTs2023-12-26%2014:24:05.0b (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Tada, Y.; Sugiura, Y.; Kamishima, M.; Tanaka, Y.; Tsuchiya, H.; Masuda, J.; Yamanaka, K. Safety and effectiveness of guselkumab in Japanese patients with psoriasis: 20-week interim analysis of a postmarketing surveillance study. J. Dermatol. 2024, 51, 779–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Food and Drug Administration. TREMFYA (Guselkumab) Injection, for Subcutaneous Use. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/761061s000lbl.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Reich, K.; Gordon, K.B.; Strober, B.E.; Armstrong, A.W.; Miller, M.; Shen, Y.K.; You, Y.; Han, C.; Yang, Y.W.; Foley, P.; et al. Five-year maintenance of clinical response and health-related quality of life improvements in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis treated with guselkumab: Results from VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2. Br. J. Dermatol. 2021, 185, 1146–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Villaverde, R.; Rodriguez-Fernandez-Freire, L.; Armario-Hita, J.C.; Pérez-Gil, A.; Galán-Gutiérrez, M. Super responders to guselkumab treatment in moderate-to-severe psoriasis: A real clinical practice pilot series. Int. J. Dermatol. 2022, 61, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, R.; Iskandar, I.Y.K.; Kontopantelis, E.; Augustin, M.; Griffiths, C.E.M.; Ashcroft, D.M. National, regional, and worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis: Systematic analysis and modelling study. BMJ 2020, 369, m1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Oh, C.H.; Jeon, J.; Baek, Y.; Ahn, J.; Kim, D.J.; Lee, H.S.; Correa da Rosa, J.; Suárez-Fariñas, M.; Lowes, M.A.; et al. Molecular phenotyping small (Asian) versus large (Western) plaque psoriasis shows common activation of IL-17 pathway genes but different regulatory gene sets. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2016, 136, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, B.S.; Kim, M.; Suh, M.K.; Lee, Y.B.; Youn, S.W.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, C.W.; Lee, G.-Y.; Son, S.W.; Kim, K.H.; et al. Effectiveness and safety of guselkumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in real-world practice in Korea: A prospective, multicenter, observational, postmarketing surveillance study. J. Dermatol. 2025, 52, 1125–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, K.; Jian, L.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, M.; Kuang, Y. Comparison between super-responders and non-super-responders in psoriasis under adalimumab treatment: A real-life cohort study on the effectiveness and drug survival over one-year. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 2024, 35, 2331782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, C.W.; Loft, N.; Rasmussen, M.K.; Nissen, C.V.; Dam, T.N.; Ajgeiy, K.K.; Egeberg, A.; Skov, L. Predictors of response to biologics in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: A Danish nationwide cohort study. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2021, 101, adv00579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowley, J.J.; Langley, R.G.; Gordon, K.B.; Pinter, A.; Ferris, L.K.; Rubant, S.; Photowala, H.; Xue, Z.; Wu, T.; Zhan, T.; et al. Efficacy of risankizumab versus secukinumab in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: Subgroup analysis from the IMMerge study. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 12, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneschal, J.; Lacour, J.P.; Bewley, A.; Faurby, M.; Paul, C.; Pellacani, G.; De Simone, C.; Horne, L.; Sohrt, A.; Augustin, M.; et al. A multinational, prospective, observational study to estimate complete skin clearance in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque PSOriasis treated with BIOlogics in a REAL world setting (PSO-BIO-REAL). J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 2566–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldarola, G.; Galluzzo, M.; Bernardini, N.; Calabrese, L.; Grimaldi, M.; Moretta, G.; Pagnanelli, G.; Shumak, R.G.; Talamonti, M.; Tofani, L.; et al. Tildrakizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: A multicenter, retrospective, real-life study. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldarola, G.; Zangrilli, A.; Bernardini, N.; Bavetta, M.; De Simone, C.; Graceffa, D.; Bonifati, C.; Faleri, S.; Giordano, D.; Mariani, M.; et al. Risankizumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis: A multicenter, retrospective, 1 year real-life study. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastorino, L.; Siliquini, N.; Avallone, G.; Zenone, M.; Ortoncelli, M.; Quaglino, P.; Dapavo, P.; Ribero, S. Guselkumab shows high efficacy and maintenance in the improvement of response until week 48, a real-life study. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rompoti, N.; Politou, M.; Stefanaki, I.; Vavouli, C.; Papoutsaki, M.; Neofotistou, A.; Rigopoulos, D.; Stratigos, A.; Nicolaidou, E. Brodalumab in plaque psoriasis: Real-world data on effectiveness, safety and clinical predictive factors of initial response and drug survival over a period of 104 weeks. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrmanidou, E.; Kemanetzi, C.; Stavros, C.; Trakatelli, M.G.; Patsatsi, A.; Madia, X.; Ignatiadi, D.; Kalloniati, E.; Apalla, Z.; Lazaridou, E. A real-life 208 week single-centred, register-based retrospective study assessing secukinumab survival and long-term efficacy and safety among Greek patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, including difficult-to-treat manifestations such as genitals and scalp. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2024, 14, e2024119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastorino, L.; Susca, S.; Cariti, C.; Verrone, A.; Stroppiana, E.; Ortoncelli, M.; Dapavo, P.; Ribero, S.; Quaglino, P. “Super-responders” at biologic treatment for psoriasis: A comparative study among IL17 and IL23 inhibitors. Exp. Dermatol. 2023, 32, 2187–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, C.; Ortmann, C.E.; Vandemeulebroecke, M.; Kasparek, T.; Reich, K. Nail involvement as a predictor of differential treatment effects of secukinumab versus ustekinumab in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 12, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A.W.; Riedl, E.; Brunner, P.M.; Piaserico, S.; Visser, W.I.; Haustrup, N.; Konicek, B.W.; Kadziola, Z.; Nunez, M.; Brnabic, A.; et al. Identifying predictors of PASI100 responses up to month 12 in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis receiving biologics in the Psoriasis Study of Health Outcomes (PSoHO). Acta Derm. Venereol. 2024, 104, adv40556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäkel, K.; Reich, K.; Asadullah, K.; Pinter, A.; Jullien, D.; Weisenseel, P.; Paul, C.; Gomez, M.; Wegner, S.; Personke, Y.; et al. Early disease intervention with guselkumab in psoriasis leads to a higher rate of stable complete skin clearance (‘clinical super response’): Week 28 results from the ongoing phase IIIb randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, GUIDE study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, 2016–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.-O.; Shin, B.S.; Bae, K.-N.; Shin, K.; Kim, H.-S.; Ko, H.-C.; Kim, M.-B.; Kim, B. Review of the reasons for and effectiveness of switching biologics for psoriasis treatment in Korea. Indian. J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2023, 89, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Park, S.H.; Zhong, Y.; Sima, A.P.; Zhuo, J.; Roberts-Toler, C.; Becker, B.; Hovland, S.; Strober, B. The association between patient-reported disease burden and treatment switching in patients with plaque psoriasis treated with nonbiologic systemic therapy. Psoriasis 2024, 14, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strober, B.; Papp, K.A.; Lebwohl, M.; Reich, K.; Paul, C.; Blauvelt, A.; Gordon, K.B.; Milmont, C.E.; Viswanathan, H.N.; Li, J.; et al. Clinical meaningfulness of complete skin clearance in psoriasis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 75, 77–82.e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, S.W.; Lee, J.H.; Yu, D.Y.; Kim, Y.; Kim, B.S.; Seo, S.J.; Choe, Y.B.; Yun, S.K.; Park, J.; Kim, N.I.; et al. The relationship between clinical characteristics including presence of exposed lesions and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients with psoriasis: Analysis from the nationwide epidemiologic study for psoriasis in Korea (EPI-PSODE study). J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2018, 32, 1499–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.