Abstract

Background/Objectives: Evidence-based recommendations are vital in healthcare to standardize care, reduce variability, and improve patient outcomes. In children, anaphylaxis, allergy to antibiotics, and hymenoptera venom allergy are among the commonest reasons for allergological evaluation. This work was intended to optimize the prescriptions for allergological evaluation and for the related diagnostic tests with the aim of improving the management of children with allergic diseases and promoting resource efficiency. Methods: A systematic literature review of the literature was performed to formulate recommendations on the diagnostic management of children with anaphylaxis, drug allergy, and hymenoptera venom allergy. Results: Effective management of anaphylaxis involves rapid assessment and specialist follow-up to identify triggers, prevent recurrence, and ensure patients and caregivers are educated and equipped with an adrenaline auto-injector. Integrating skin testing, specific serological assays, and oral provocation tests into the diagnostic process for children with suspected beta-lactam allergy enhances diagnostic accuracy and minimizes unnecessary avoidance of first-line antibiotics. Children and adolescents with systemic reactions to hymenopteran stings should be referred to an allergy specialist for diagnosis, risk assessment, management education, and adrenaline prescription. Conclusions: These recommendations may enhance care quality, minimize inappropriate prescriptions, and support standardized methods of diagnosis of allergological diseases in children.

1. Introduction

The appropriateness of prescriptions for clinical and instrumental tests plays a role in managing waiting lists and provides consistency and equity in access to care. Conversely, inappropriateness results in waste of time and resources for patients and their families and in unnecessary burden for specialists and the healthcare system. For this reason, the production of clear, shared recommendations based on the best available scientific evidence can be instrumental for improving the quality of care and optimizing the use of resources, ultimately contributing to the sustainability of the National Health Service [1]. Due to the significant burden in pediatric age subjects, Good Clinical Practice Recommendations (GCPR) may be of substantial significance in the specific setting of pediatric allergology, particularly when dealing with conditions associated with potentially life-threatening conditions such as anaphylaxis, including the specific subtheme of hymenoptera venom allergy (HVA), and drug allergy (DA) [2,3,4,5]. The global prevalence of anaphylaxis in children ranges from 0.04% to 1.8% depending on countries [6]. Considering the emergency department (ED) visits, the median hospitalization rate is 3.5% [7]. Anaphylaxis caused by hymenoptera venom affects between 0.3% and 8.9% of individuals who are stung. Nevertheless, it remains the leading cause of anaphylaxis and is responsible for 20% of all fatal cases of anaphylaxis [8,9,10]. In children the prevalence of drug hypersensitivity reactions ranges from 1% to 10.2% and 4–9% of these reported cases are confirmed as true allergic [11].

The challenging task of designing up-to-date and effective GPCS, four main principles must be preliminarily fulfilled: (1) clarity in the definition of each attribute; (2) compatibility of each attribute and its definition with professional usage; (3) clear rationales and justifications for the selection of each attribute, and the (4) sensitivity to practical issues in using the attribute to assess actual sets of practice guidelines (i.e., “accessibility”). In turn, when properly defined, aforementioned attributes should guarantee validity (i.e., when followed, GCPR lead to the projected health and costs outcomes), reliability/reproducibility, clinical applicability, clinical flexibility, clarity, and—finally yet importantly—multidisciplinarity of all newly designed GCPR.

The aim of the work was the creation of shared recommendations for Italian pediatricians based on the best available evidence to reduce variability of prescriptions, harmonize medical practices at a national level, improve equity in access to health services, on the following themes: diagnostic management of anaphylaxis, DA, and HVA among children and adolescents.

2. Methods

2.1. Working Group and Panel of Experts

The present document is the result of the joint work of a multidisciplinary panel, which includes representatives of pediatrics scientific societies (Italian Society of Pediatricians [Società Italiana Medici Pediatri, in Italian; SIMPE], Italian Society of Pediatrics [Società Italiana di Pediatria, in Italian; SIP], Italian Society of Pediatric Allergology and Immunology [Società Italiana di Allergologia e Immunologia Pediatrica, in Italian; SIAIP], Italian Society for Childhood Respiratory Diseases [Società Italiana per le Malattie Respiratorie Infantili, in Italian, SIMRI], Italian Society of Pediatric Emergency Medicine [Società Italiana di Medicina di Emergenza e Urgenza Pediatrica, in Italian; SIMEUP], Italian Society of Pediatric Primary Care [Società Italiana delle Cure Primarie Pediatriche, in Italian; SICuPP]); representatives of scientific societies of specialists involved in the care of allergic children (Italian Society of Pediatric Dermatology [Società Italiana di Dermatologia Pediatrica, in Italian; SIDerP], Italian Association of Local and Hospital Allergists and Immunologists [Associazione Allergologi Immunologi Italiani Territoriali e Ospedalieri, AAITO]), as well as experts in legal medicine from the Legal and Insurance Medicine (Società Italiana di Medicina Legale e delle Assicurazioni, in Italian; SIMLA), and in telemedicine from Italian Telemedicine Society, (Società Italiana di Telemedicina, in Italian; SIT).

In order to guarantee the multidisciplinarity of GCPR on the topics of anaphylaxis, HVA, and DA, a multi-professional working group was designed and included pediatric allergologists, general pediatricians, general practitioners, clinical immunologists, otolaryngologists, dermatologists, clinical pharmacologists, psychologists, and pediatric nurses. The group also had methodologists and representatives of patient associations to respond to the concrete needs of the families. This study was part of a broader initiative aimed at producing evidence-based GCPR for prescriptions in pediatric patients with allergic diseases convened under the Italian Superior Institute of Health (Istituto Superiore di Sanità, in Italian; ISS).

2.2. Formulation of Clinical Questions

As a preliminary step, research questions on the topics of diagnostic management of anaphylaxis, DA, and HVA among children and adolescents were discussed and then developed by the working group according to the model population/patient (P), intervention (I), comparator (C), outcome (O), or PICO [12,13]. Each member of the working group was invited to share a total of five PICOs for each assessed topic for a total of 15 PICOs. All PICOs were then gathered and scored by experts through a LIKERT scale (0–3 not agreeing, 4–6 moderately agreeing, 7–9 strongly agreeing): only PICOs with an average score > 7 were eventually included into the subsequent analyses.

2.3. Systematic Review

To answer the research questions eventually approved by participating experts, a series of systematic review of the literature was performed. Three different databases (Medline, Embase, and Cochrane) were searched, exploring specific keywords such as “allergy,” “atopy,” “allergic disease,” and additional keywords for each considered condition (the complete search strings are available in the Table A1). Inclusion criteria were the following ones:

- Design of the source studies: only randomized controlled trials (RCTs), observational cohort studies with a comparator, case–control studies were included; regarding secondary sources, systematic reviews with and without meta-analyses and guidelines were initially retrieved and then assessed for obtaining additional entries through a snowball approach. Conversely, case reports, letters to the editor, brief reports, and conference abstracts were excluded;

- Age groups, only studies reporting on subjects aged 0–18 years were considered;

- Language and timeframe: the search was arbitrarily limited to results in English, published between January 2015 and January 2025.

According to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [12,13], suitable articles were initially pooled together. After the removal of duplicates, two researchers conducted title and abstract screening independently and blindly. Articles fulfilling inclusion criteria were then similarly blindly reviewed by two researchers. Conflicts in each state of the systematic review were resolved through discussion with a third researcher (see Prisma Checklist as Supplementary Materials Table S1).

Risk of bias of observational studies was assessed by means of the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS, potential range from 0 to 9 points). NOS has been extensively recommended by Cochrane Collaboration for the qualitative assessment of source studies to be implemented into systematic reviews [14]. The NOS scale consists of four domains of risk of bias assessment: (1) selection bias; (2) performance bias; (3) detection bias; and (4) information bias. All of them have been specifically tailored for case–control and cohort studies, while no specific recommendation was originally identified for cross-sectional studies. However, as cross-sectional studies and cohort studies share a similar structure, except for the timing of the measurement for exposures and outcomes (i.e., at the same time, or cross-sectionally, for cross-sectional studies; after the exposure for cohort studies) [15] we opted to apply the cohort studies scale also to cross-sectional ones. According to the current indications and the study protocols, two investigators independently rated all suitable articles and provided a summary of their potential shortcomings. Potential disagreements were primarily resolved by consensus between the two reviewers; input from a third investigator was requested and obtained when consensus was not possible. Predefined thresholds were defined as follows: 0–3 low quality, 4–6 moderate quality, 7–9 high quality. In order to gather the largest available sample of studies, we tentatively included into the analyses all studies fulfilling inclusion criteria despite their eventual quality.

For RCT, ROB tool from the National Toxicology Program (NTP)’s Office of Health Assessment and Translation (OHAT) (now the Health Assessment and Translation (HAT) group) was implemented [16,17]. OHAT ROB provides a 4-point scale rating (from “definitely low”, “probably low”, and “probably high” to “definitely high”) on the following potential sources of bias: participant selection (D1), confounding factors (D2), attrition/exclusion (D3), detection (D4), and selective reporting (D5), as well as other sources of bias (D6). OHAT ROB was prioritized over other instruments for ROB assessment, as it does not provide an overall rating for each study, nor does it require that studies affected by a certain degree of ROB be removed from the pooled analyses [17].

2.4. Data Extraction

Articles meeting all inclusion criteria were then selected for data extraction, including title, authors, journal, and year of publication, target population (by disease and age), type of intervention and comparator, and results. Where available, numerical data were extracted for possible meta-analysis; if unavailable, results were reported narratively.

2.5. Meta-Analysis

When at least five studies evaluated the same type of intervention in the same population and reported the same outcome, a meta-analysis was conducted. For dichotomous data, if derived from randomized controlled trials, Relative Risk with a 95% confidence interval was used; for observational studies, Odds Ratio with a 95% confidence interval was used. For continuous variables, the mean difference or standardized mean difference was used if different scores were used to evaluate the same outcome. These analyses were conducted when the mean, standard deviation, and sample size of each group were available. If the mean and standard deviation were not directly available but other data, such as the confidence interval, were available, the standard deviation was imputed from the available data. If data were not available, an email was sent to the corresponding author requesting the data to include the study in the meta-analysis.

The meta-analysis was conducted by means of R (version 4.3.1) [18] and Rstudio (version 2023.06.0 Build 421; Rstudio, PBC; Boston, MA, USA) software by means of the packages meta (version 7.0) and fmsb (version 0.7.5).

2.6. GRADE and GRADE Framework

To assess the quality of the evidence found, the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) method was applied. For each PICO, the different outcomes considered were evaluated by dividing them into subgroups based on the type of intervention. For each outcome, the quality of the evidence found was assessed, considering the type of study included, the evaluation of biases, the lack of reproducibility of results, the lack of generalizability, imprecision, and the presence of any additional considerations related to possible publication biases. For each intervention for each PICO, different aspects were evaluated: the magnitude of the problem, the desired effect, the undesired effect, the certainty of the evidence, the value of the studies found, the benefit-risk balance, the resources required, the certainty of the evidence for the resources required, the cost–benefit balance, equity, acceptability, and sustainability.

2.7. Consensus Panel for the Strength of Recommendations

To reach a consensus on the strength of the recommendations, a consensus was conducted among the expert panel through a survey. Once the recommendations were formulated, a survey was sent to each member of the panel. Using a Likert scale from 0 to 9, each expert was asked to express their opinion on the strength of the recommendation (0–3 low strength, 4–6 moderate, 7–9 strong) and on sustainability (0–3 not sustainable, 4–6 probably sustainable, 7–9 certainly sustainable). The average scores given by each expert were then used to define the strength of the recommendations. In case of highly contradictory responses, the survey results were discussed among the expert panel.

The development process of the recommendations was in accordance with the standards defined by the document “Methodological guidelines for drafting recommendations for good clinical and care practices”.

3. Results

The risk of bias assessment of each study has been reported in Table A2 and Table A3, while the detailed description of the included studies is reported in Table A4, Table A5, Table A6, Table A7, Table A8, Table A9 and Table A10. The quality of evidence, evaluated with GRADE methods, within the GRADE Framework, is summarized by the end of each of the following sections.

3.1. Anaphylaxis

3.1.1. Summary of Literature Search

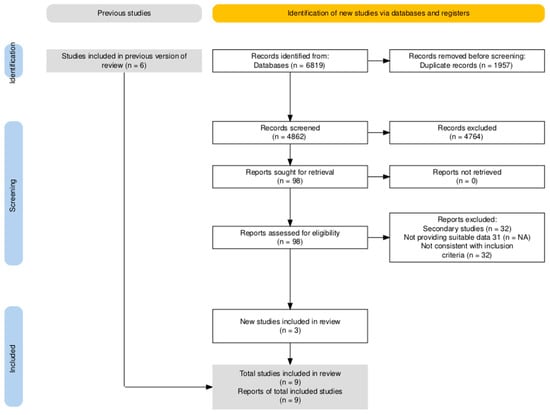

The research on three databases (Embase, Medline, Cochrane) identified a total of 6819 articles. Study selection process is presented in the PRISMA flow diagram reported in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart for anaphylaxis of included studies.

Briefly, after the removal of duplicates across included databases (n = 1957; 28.7% of initial sample), remaining 4862 studies were title and abstract screened. Most of the articles were considered as not consistent with the inclusion criteria: 4764 articles (69.9% of the original sample) were therefore removed from the analyses, with 98 studies (1.4%) considered as suitable for being full-text screened. In accord with the expert opinion, 6 additional articles were then included outside the original database search, bringing the total number of assessed entries to 104. Nine articles were ultimately included in the final analyses: five of them were observational studies, and 4 were RCTs (Table A3, Table A4 and Table A5).

3.1.2. Clinical Questions for Anaphylaxis

PICO 1

For children and adolescents suspected of having anaphylaxis (P), is a deferred-urgency allergy evaluation recommended in order to identify the triggering factor, prescribe an adrenaline auto-injector (AAI) with appropriate training in its use and provide strategies for preventing and managing recurrences, (I), rather than routine follow-up with a primary care pediatrician (C), thereby reducing the risk of recurrence and emergency department visits (O)?

According to the specific P.I.C.O. question, the main outcomes considered included:

- The diagnostic accuracy of allergy tests in identifying the causal agent and initiating a specific management pathway.

- The risk of recurrent anaphylactic episodes.

Evidence (Quantitative analysis): Due to the heterogenous design of retrieved studies, both in terms of targeted population and included outcomes, no quantitative summary of evidence was ultimately performed by means of a meta-analytical approach.

Evidence (Narrative report): The World Allergy Organization (WAO) Anaphylaxis Committee defines anaphylaxis as a severe, systemic hypersensitivity reaction which usually develops rapidly and may be fatal. The most critical presentations involve a life-threatening compromise of the airway, breathing, and/or circulation. This can occur even when there are no typical skin symptoms or circulatory shock [2]. The first-line treatment for anaphylaxis is intramuscular (IM) adrenaline, which is administered into the anterolateral thigh. If the clinical response is inadequate, a second dose may be administered after 5–10 min; most reactions resolve following one or two injections [19,20].

The 2021 update of the Resuscitation Council United Kingdom (RCUK) guidelines highlighted persistent deficiencies in the recognition, treatment and follow-up of anaphylaxis. IM adrenaline was not administered in approximately 50% of reported cases, primarily due to failure to recognize anaphylaxis [21].

Diagnosis can be particularly challenging in children due to the variable and sometimes non-specific clinical presentation, ranging from mild to severe, potentially life-threatening reactions [22]. Among patients with anaphylaxis of unknown etiology, only 56% were referred to an allergologist, who subsequently identified the causative agent in 38% of cases [17].

Referral to a tertiary allergy centre and structured long-term follow-up are essential for identifying individual risk factors, implementing allergen avoidance strategies, preventing recurrences and providing targeted patient education. Furthermore, referral to an allergologist is associated with higher rates of AAI prescription [23].

This approach is particularly important for patients deemed to be at increased risk of recurrence, including those with a history of severe reactions, known triggers (e.g., peanuts or tree nuts), or coexisting asthma [22,24].

Both the WAO and the RCUK guidelines recommend the prompt and specialized management of anaphylaxis. A specialist evaluation by a qualified allergologist is required to identify the trigger, prescribe an AAI, provide training on its correct use, and establish a comprehensive prevention plan [2,21].

Education on the adrenaline self-administration is a key component of anaphylaxis management. In a randomized controlled trial, Umasunthar et al. demonstrated a high rate of correct AAI use six weeks after training, with correct technique still being retained after one year without further training. However, when a different device model was provided without additional training, success rates decreased significantly [25].

There are several adrenaline delivery devices available. The most common of these are auto-injectors, which are single-use, pre-dosed devices that can be stored at room temperature and used safely by non-medical individuals. In settings where auto-injectors are unavailable, prefilled syringes are an acceptable alternative [26].

Structured education and hands-on training in the auto-injector use improve patients’ quality of life by reducing anxiety and increasing confidence in managing future reactions [27]. Evidence from epidemiological studies, animal models, and small-scale human studies suggests that the timely use of AAI may prevent fatal outcomes [28].

However, various concerns identified by parents may prevent or delay the utilization of AIA, including reluctance to carry the device, apprehension regarding needles, and insufficient training [29]. Recently, epinephrine nasal spray (neffy) was approved as the first needle-free epinephrine option for the treatment of anaphylaxis for adults and children >15 kg [30,31]. The diffusion of this device in the community of patients may have a positive impact on the management of anaphylaxis, particularly in pediatric age, overcoming the barrier of needle-phobia and promoting early administration. Despite clear recommendations, anaphylaxis remains under-recognized and under-treated, with patients not being referred for specialist follow-up care as often as they should be. Greater specialist involvement is required to improve clinical outcomes and reduce recurrence risk [2,21].

The ANA-PED study revealed persistent shortcomings in the management of pediatric anaphylaxis in emergency departments. Notably, only 17% of children were administered adrenaline during their visit, while 28.1% were prescribed an AAI upon discharge. Furthermore, only 57.1% were referred for specialist allergy follow-up [32].

Recommendation (Table 1): Due to the moderate quality of evidence, a consensus-based recommendation rather than an evidence based was framed. The management of anaphylaxis requires both prompt assessment of the acute episode and a long-term allergy evaluation. Specialist consultation is essential to identify the causative triggers, implement effective allergen avoidance strategies, provide education to patients and caregivers on prevention of future reactions and prescribe AAI.

Table 1.

Summary of evidence and main recommendations on the role of deferred-urgency allergy evaluation for identifying the triggering factor, prescribe an adrenaline auto-injector (AAI) with appropriate training in its use, and provide strategies for preventing and managing recurrences, compared to the routine follow-up with a primary care pediatrician.

PICO 2

For children and adolescents suspected of having anaphylaxis (P), is measuring of serum tryptase (from 30 min to 4 h after onset of the reaction) and baseline tryptase (after complete resolution of symptoms, at least 24 h later) (I) recommended over clinical follow-up alone (C), to facilitate diagnosis, stratify risk (e.g., identify underlying conditions such as systemic mastocytosis or predisposition to more severe reactions) and improve long-term management (preventing new episodes)? (O)

Evidence (Quantitative analysis): Due to the heterogenous design of retrieved studies, both in terms of targeted population and included outcomes, no quantitative summary of evidence was ultimately performed by means of a meta-analytical approach.

Evidence (Narrative report): In a study involving 965 children with anaphylaxis, serum tryptase levels were measured within 2 h of symptom onset in 203 cases, and 19.2% of these showed elevated levels (≥11.4 μg/L). This finding was significantly associated with severe reactions. The same study compared tryptase concentrations during the acute phase and after recovery. It demonstrated a mean difference of 6.3 μg/L, indicating that tryptase levels in the blood were significantly higher during the acute episode than at baseline. These results reinforce the use of tryptase as a mast cell activation biomarker and confirm its value in diagnosing atypical or uncertain cases of anaphylaxis [33]. Conversely, the study by Cavkaytar et al. [34], which involved 345 children suspected of having drug-induced anaphylaxis, found that baseline serum tryptase levels were similar in those with confirmed drug hypersensitivity (n = 106) and in healthy controls. While these contrasting findings suggest that serum tryptase is a poor predictive biomarker, the 2020 WAO anaphylaxis guidelines [2] nevertheless recommend measuring serum tryptase levels in cases of anaphylaxis. A significant elevation in serum tryptase levels can support the diagnosis, particularly in cases with atypical presentations or absent cutaneous manifestations. Comparing serum tryptase levels immediately after an anaphylactic episode with baseline levels may help to identify predisposing conditions, such as systemic mastocytosis or other mast cell disorders, which increase the risk of severe or treatment-resistant reactions [35]. Children with cutaneous mastocytosis have been shown to exhibit elevated baseline serum tryptase levels and may be at increased risk of anaphylaxis, especially when skin involvement is extensive [36]. Furthermore, elevated levels of serum tryptase are found in hereditary α-tryptasemia (HαT), a genetic trait caused by increased α-tryptase-encoding Tryptase-α/β1 (TPSAB1) copy number. This condition is a known genetic risk factor for mast cell activation and severe anaphylaxis episodes [37].

However, tryptase levels should not be used as the sole criterion for diagnosis, but rather as part of a comprehensive allergological assessment that takes into account clinical findings and the patient’s medical history [36].

Recommendation (Table 2): Due to the moderate quality of evidence, a consensus-based recommendation rather than an evidence based was framed. Measuring serum tryptase levels during an anaphylactic episode and at baseline is particularly valuable in cases where the diagnosis of anaphylaxis is uncertain or atypical. It can help to confirm a diagnosis of anaphylaxis and to identify underlying conditions, such as systemic mastocytosis.

Table 2.

Summary of evidence and main recommendations on the role of measurement of serum tryptase over clinical follow-up alone, to facilitate diagnosis, stratify risk (e.g., identify underlying conditions such as systemic mastocytosis or predisposition to more severe reactions) and improve long-term management (i.e., preventing new episodes).

PICO 3

In children and adolescents with suspected food allergy–related anaphylaxis (P), is performing skin prick testing (SPT) with both commercial extracts and fresh foods (I) recommended over clinical follow-up alone (C) to prevent new episodes, improve diagnostic accuracy, avoid unnecessary elimination diets, and enhance quality of life (O)?

Evidence (Quantitative analysis): Due to the heterogenous design of retrieved studies, both in terms of targeted population and included outcomes, no quantitative summary of evidence was ultimately performed by means of a meta-analytical approach.

Evidence (Narrative report): SPT is recommended for identifying allergens responsible for anaphylactic reactions [2]. However, the current guidelines emphasize that SPT results should always be interpreted alongside a detailed clinical history, since Immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated sensitization does not necessarily indicate a clinically significant allergic response.

Food-induced anaphylaxis presents with variable clinical features, and SPT plays a central role in identifying common triggers such as peanuts, tree nuts, and shellfish [38]. Although SPT is generally considered safe, the WAO guidelines [2] recommend that testing is performed in settings equipped with emergency facilities and staffed by personnel trained to recognize and manage anaphylaxis and other adverse reactions. Patients should be monitored for an appropriate observation period following testing to detect potential systemic responses. When SPT results are inconclusive or inconsistent with the clinical history, additional diagnostic investigations, such as serum-specific IgE measurement or an oral food challenge, may be required to establish a definitive diagnosis of anaphylaxis. Diagnostic assessment of food allergy and anaphylaxis should always begin with a comprehensive clinical history, followed by targeted testing, including SPT, measurement of specific IgE, and, in selected cases, the basophil activation test (BAT) [39,40]. Specific IgE may be useful when skin testing is unavailable, when standardized extracts do not exist, or when longitudinal monitoring is needed as children outgrow food allergies. However, The oral food challenge remains the gold standard for diagnostic confirmation [38], but it should only be performed in specialized clinical settings due to the potential risk of inducing systemic reactions [3,40]. Children with confirmed food allergies should undergo regular re-evaluation, using repeat allergy testing and/or oral food challenges, to assess whether they have developed a natural tolerance and to support the safe reintroduction of previously excluded foods [3]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors for severe allergic reactions to foods demonstrated that, while traditional diagnostic tools such as SPT and specific IgE testing are valuable for identifying sensitization and supporting diagnosis, they have no predictive value for assessing the severity of allergic reactions [41].

Recommendation (Table 3): Due to the moderate quality of evidence, a consensus-based recommendation rather than an evidence based was framed. SPT represents the first-step diagnostic tool for identifying allergen sensitization in patients suspected of having food-induced anaphylaxis. The oral food challenge remains the gold standard for definitive diagnosis.

Table 3.

Summary of evidence and main recommendations on the role of skin prick testing (SPT) with both commercial extracts and fresh foods recommended over clinical follow-up alone (C) to prevent new episodes, improve diagnostic accuracy, avoid unnecessary elimination diets, and enhance quality of life among children and adolescents with suspected food allergy–related anaphylaxis.

PICO 4

In children and adolescents suspected of having anaphylaxis (P), is it recommended that specific IgE is measured by means of component-resolved diagnostics (CRD) (I), rather than relying solely on clinical follow-up (C), in order to identify individual risk profiles, personalize prevention strategies, and prevent new episodes (O)?

Evidence (Quantitative analysis): Due to the heterogenous design of retrieved studies, both in terms of targeted population and included outcomes, no quantitative summary of evidence was ultimately performed by means of a meta-analytical approach.

Evidence (Narrative report): CRD enables the identification and quantification of IgE antibodies directed against individual allergenic protein components, offering greater molecular specificity than conventional assays, which measure IgE reactivity to whole allergen extracts [42]. CRD is particularly valuable in complex clinical contexts, such as idiopathic anaphylaxis, where it may help detect causal allergens that are not easily identified through traditional testing. It also facilitates the distinction between true clinical allergy and cross-reactivity, for example, in cases involving hazelnut or peanut allergy [43]. CRD should be regarded as a complementary diagnostic tool rather than a standalone method. Its results should always be interpreted within the framework of a comprehensive clinical assessment [2]. However, CRD has certain limitations, such as lower sensitivity compared to extract-based diagnostics and variability in performance depending on the studied population and the routes of sensitization [42]. Consequently, CRD should be employed as an adjunct to conventional diagnostics, with its clinical relevance evaluated on an individual basis. Furthermore, the lack of standardized diagnostic thresholds and the limited availability of CRD in certain clinical settings currently restricts its wider implementation. SPTs and specific serum IgE measurements are unreliable indicators of the severity of a reaction or the risk of anaphylaxis during oral food challenges. Conversely, allergenic components identified through CRD can provide information about the risk of severe reactions, especially when combined with other clinical markers. For instance, monosensitization to Arachis hypogaea (Ara h) 8 in peanut allergy is linked to a reduced likelihood of anaphylaxis and frequently indicates pollen–food allergy syndrome (PFAS). In contrast, sensitization to proteins such as Prunus persica (Pru p) 3 (peach) and 2S albumins in tree nut allergies has been linked to an increased risk of systemic reactions [41]. The 2023 European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) Guidelines support the use of CRD in the evaluation of sensitization to specific foods, including peanuts, hazelnuts and cashews. Measurement of IgE to allergen components such as Ara h 2, Corylus avellana (Cor a) 14, and Anacardium occidentale (Ana o) 3 can enhance diagnostic accuracy, particularly in patients with concomitant pollen sensitization [3]. In this context, the study by Kukkonen et al. provides further evidence supporting the use of CRD in peanut allergy. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge involving children and adolescents, the authors found that sensitization to Ara h 2 and Ara h 6 was strongly associated with moderate to severe allergic reactions. Moreover, the combined measurement of IgE to Ara h 2 and Ara h 6 accurately identified all individuals who experienced severe reactions at low allergen doses. By contrast, IgE to Ara h 8 did not correlate with clinically relevant reactions, thus confirming its limited prognostic value in severe peanut allergy [44]. Similarly, other research has shown that although CRD improves the differentiation between allergic and non-allergic children to peanuts, IgE levels to individual components, including Ara h 2 and Ara h 8, do not consistently correlate with reaction severity or eliciting dose during oral food challenges. These findings underscore the current limitations of CRD as a prognostic tool [45]. These findings suggest that the detection of specific IgE, particularly to Ara h 6, may provide significant prognostic information, potentially reducing the need for oral food challenges in selected patients and contributing to risk stratification [44].

Recommendation (Table 4): Due to the low to moderate quality of evidence, a consensus-based recommendation rather than an evidence based was framed When used by allergologists in an appropriate clinical context, CRD is an advanced tool that can improve the management of food-induced anaphylaxis. Evidence supports its role in evaluating the risk of severe allergic reactions in patients with specific sensitization profiles and allergen types.

Table 4.

Summary of evidence and main recommendations on the role of measurement of specific IgE by means of component-resolved diagnostics (CRD), rather than relying solely on clinical follow-up, in order to identify individual risk profiles, personalize prevention strategies, and prevent new episodes among children and adolescents suspected of having anaphylaxis.

3.2. Drug Allergy

3.2.1. Summary of Literature Research

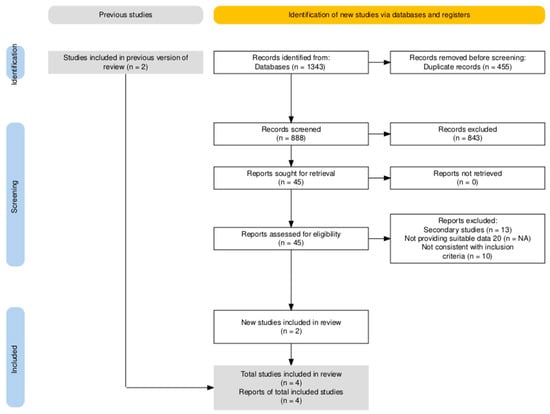

Study selection process is presented in the PRISMA flow diagram reported in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flowchart for included studies on drug allergy.

The systematic search across three databases (Embase, Medline, Cochrane) identified 1343 entries: after the removal of duplicates and articles not suitable with the aims of the literature search (n = 1298, 96.6%), 45 studies were full-text screened (3.4%): two additional articles not included in the search result were added based on expert opinion. A total of 13 articles were therefore identified. Of them, only four were included into the final analyses as observational studies: no RCTs were retrieved, and all of the remaining articles were secondary studies, i.e., meta-analyses, literature reviews, and guidelines/recommendations.

The outcomes considered, according to the P.I.C.O. framework, mainly concerned:

- The diagnostic accuracy of allergy tests to identify the causal agent;

- The inappropriate use of antibiotics.

3.2.2. Clinical Questions on Drug Allergy

PICO 1

In children and adolescents suspected of having a beta-lactam antibiotic allergy (P), does using skin tests, oral provocation tests (OPT) and specific serological assays (I) improve diagnostic accuracy, reduce misdiagnoses and decrease the use of less effective alternative treatments (O), compared with a diagnosis based solely on clinical history (C)?

Evidence (Quantitative analysis): Due to the heterogenous design of retrieved studies, both in terms of targeted population and included outcomes, no quantitative summary of evidence was ultimately performed by means of a meta-analytical approach.

Evidence (Narrative report). The diagnosis of a beta-lactam allergy in children and adolescents should not be based solely on the patient’s medical history, as this approach carries a high risk of overdiagnosis and may lead to the unnecessary avoidance of first-line antibiotics [4,46,47,48]. Incorporating structured diagnostic tools, such as skin tests, specific IgE assays, and OPT, has been shown to significantly improve diagnostic accuracy, reduce false-positive results, and limit the use of less effective alternative antibiotics [4,46,47,48]. There have been conflicting results reported regarding OPT. Goh et al. [49] found that the majority of children undergoing OPT experienced negative results. Conversely, other studies [50,51] have highlighted the high safety and diagnostic yield of OPT, particularly in children presenting with mild or delayed cutaneous reactions. Although skin tests are less definitive, they are still useful for identifying children who are at a higher risk of immediate hypersensitivity. However, they are not very sensitive or specific, which reinforces the need to proceed with oral provocation testing [52]. The combined use of detailed clinical history, skin testing, and OPT markedly improves overall diagnostic reliability. In selected cases, repeating tests may be warranted when initial results are inconclusive [46,53]. By accurately identifying patients with genuine allergies, clinicians can safely prescribe first-line beta-lactam antibiotics to most children who are not allergic. This supports a more rational and evidence-based approach to antibiotic stewardship [54,55].

Recommendation (Table 5): Due to the moderate quality of evidence, a consensus-based recommendation rather than an evidence based was framed. Integrating skin testing, specific serological assays and oral OPT into the diagnostic pathway for children and adolescents suspected of having a beta-lactam allergy improves diagnostic accuracy and reduces the unnecessary avoidance of effective first-line antibiotics.

Table 5.

Summary of evidence and main recommendations on the role of skin tests, oral provocation tests (OPT) and specific serological assays for improving diagnostic accuracy, reducing misdiagnoses and decreasing the use of less effective alternative treatments, compared with a diagnosis based solely on clinical history, among children and adolescents suspected of having a beta-lactam antibiotic allergy.

PICO 2

In children and adolescents suspected of having an antibiotic allergy (P), does using a targeted diagnostic pathway before prescribing alternative antibiotics (I) reduce the inappropriate use of second-line agents (O), compared with empirically prescribing unrelated antibiotics (C)?

Evidence (Quantitative analysis): Due to the heterogenous design of retrieved studies, both in terms of targeted population and included outcomes, no quantitative summary of evidence was ultimately performed by means of a meta-analytical approach.

Evidence (Narrative report): In children and adolescents with suspected beta-lactam allergy, a targeted diagnostic pathway may substantially reduce the inappropriate use of second-line antibiotics, thereby improve patient safety and support antimicrobial stewardship [46,48,50]. Many reported penicillin allergies are not true IgE-mediated reactions but are often based on historical information or non-allergic adverse effects. Studies suggest that up to 90% of people who think they are allergic to penicillin can safely take the drug following appropriate allergy re-evaluation [47,56]. Consequently, empirical avoidance of beta-lactam antibiotics often results in unnecessary use of broader-spectrum or second-line agents, increasing the risk of adverse events and contributing to the development of antimicrobial resistance [52]. The implementation of a structured diagnostic algorithm, including skin testing and stepwise OPT, may enable an accurate identification of true allergic reactions. For instance, one study showed that direct OPT is both safe and effective in diagnosing beta-lactam allergy in low-risk children with mild skin symptoms [54]. Furthermore, negative skin test results can facilitate the safe reintroduction of beta-lactam antibiotics, thereby reducing the requirement for alternative second-line alternatives [4]. Guidelines from the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC), the EAACI Position Paper, and the SIAIP Position Paper all emphasize the importance of confirming suspected antibiotic allergies using the correct diagnostic procedures before prescribing alternative therapies. This strategy ensures more effective treatments and is aligned with the principles of antimicrobial stewardship, helping to preserve the efficacy of first-line antibiotics [4,47,48,57].

Recommendation (Table 6): Due to the very low quality of evidence, a consensus-based recommendation rather than an evidence based was framed A targeted diagnostic approach for suspected antibiotic allergies in pediatric patients could reduce the inappropriate use of second-line antibiotics, improve patient safety and support the broader goal of combating antimicrobial resistance.

Table 6.

Summary of evidence and main recommendations on the role of a targeted diagnostic pathway before prescribing alternative antibiotics for reducing the inappropriate use of second-line agents, compared with empirically prescribing unrelated antibiotics among children and adolescents suspected of having an antibiotic allergy.

3.3. Hymenoptera Venom Allergy

3.3.1. Summary of Literature Research

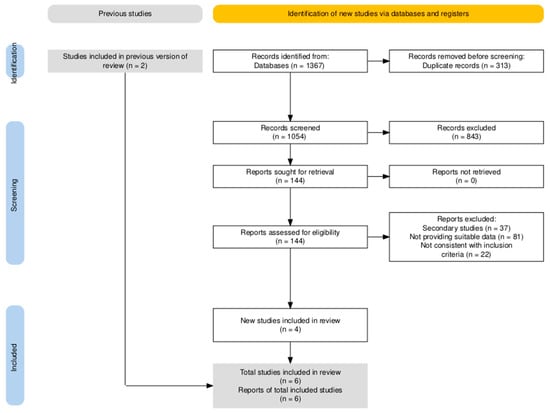

The research was performed over three databases (Embase, Medline, Cochrane) and identified a total of 1367 articles. Detailed study selection process is presented in the PRISMA flow diagram reported in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

PRISMA flowchart for included studies on hymenoptera venom allergy.

Briefly, after the removal of duplicated items (n = 313, 22.9%), remaining 1054 articles were screened by title and abstract, with the subsequent identification of 144 suitable entries (10.5% of the original sample). A total of 10 articles were then suggested by expert opinion, but only two of them were eventually consistent with the aims of the literature search. A total of six studies were eventually included into the analyses, all of them being observational studies. Included studies are reported in full details and described in Table A9 and Table A10.

Outcomes considered (depending on the PICO) mainly included:

- Risk of anaphylaxis;

- Diagnostic accuracy to initiate appropriate treatment.

3.3.2. Clinical Questions for Hymenoptera Venom Allergy

PICO 1

For children and adolescents with systemic reactions to hymenopteran stings (P), is referral to an allergy specialist (I) recommended over management by the primary care pediatrician (C) to assess the risk of anaphylaxis and initiate preventive treatment (O)?

Evidence (Quantitative analysis): Due to the heterogenous design of retrieved studies, both in terms of targeted population and included outcomes, no quantitative summary of evidence was ultimately performed by means of a meta-analytical approach.

Evidence (Narrative report): Allergic reactions to Hymenoptera stings vary widely in severity and may occasionally be fatal. HVA is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, although it is still underestimated from an epidemiological perspective due to the underreporting of many cases [8]. It is estimated that up to 94% of the adult population worldwide are stung at least once in their lifetime. Hymenoptera venom-induced anaphylaxis occurs in 0.3–8.9% of people who are stung. Nevertheless, it remains the leading cause of anaphylaxis, accounting for around 20% of all fatal reactions [8,9,10]. Although children are sensitized less frequently and generally experience milder reactions than adults, likely due to lower venom exposure and fewer comorbidities, the number of pediatric patients who develop systemic reactions remains clinically significant. Epidemiological data are primarily derived from questionnaire-based studies. The prevalence of large local reactions (LLRs) ranges from 0.9% in Italy to 11.5% in Israel, whereas the prevalence of systemic reactions (SRs) has been reported to be below 1% in an Italian study but higher in an Israeli study (6.5%) [58,59]. According to data from the European Anaphylaxis Registry, HVA is the second most common cause of severe anaphylaxis in children (20.2%), following food allergy [60]. Hypersensitivity to hymenopteran venom may result from immunological mechanisms, either IgE-mediated or non-IgE-mediated, or from non-immunological processes. Allergic reactions to Hymenoptera stings are classified into simple local reactions, LLRs, SRs (anaphylactic and non-anaphylactic), toxic reactions and atypical reactions [61]. Several classification systems have been proposed over time to assess the severity of systemic reactions to Hymenoptera stings. The Müller and Ring and Messmer classifications are the most widely adopted of these, although both present certain inherent limitations. The Müller classification does not account for the possible absence of cutaneous symptoms, nor does it consider cases in which cardiovascular shock is the only clinical manifestation. By contrast, the Ring and Messmer classification focuses primarily on cardiovascular collapse, which is considered to be more severe than respiratory involvement [61,62]. A recent literature review [63] classified risk factors for anaphylactic reactions to Hymenoptera stings into two categories: situational and long-term. Several factors in the former category have been confirmed as predictors of fatal outcomes, including delayed administration of epinephrine, being in an upright posture during anaphylaxis, physical exertion during or after being stung, consuming alcohol or acetylsalicylic acid, having concomitant infections, experiencing stress, and being in the menstrual cycle. Within the group of long-term risk factors, there is evidence to suggest an association between systemic mastocytosis and severe anaphylactic reactions. Male sex, cardiovascular comorbidities and older age (over 40 years) also play a significant role due to the higher prevalence of comorbidities and increased risk of systemic reactions compared to children. In the pediatric population, the literature reports conflicting data on the risk factors that predispose individuals to SRs. A recent systematic review highlighted that a previous history of severe SRs and the number of prior stings is significant risk factors for future SRs in children. Increased exposure to a specific allergen, which is often related to lifestyle and environmental factors, has been associated with a higher risk of sensitization and subsequent SRs. Conversely, there is no conclusive evidence of a genetic predisposition in pediatric patients. In this context, ethnicity appears to influence the risk of SRs primarily through lifestyle differences among the studied populations, rather than through true genetic determinants. With respect to sex, currently available data do not indicate a significant difference in SR risk between males and females. Regarding the presence of concomitant allergic conditions, asthma has been identified as the only potential risk factor for Hymenoptera venom–induced SRs [64]. In a cohort of adolescents aged between 13 and 14, subjects suffering from asthma, but also allergic rhinitis and/or atopic dermatitis showed a significantly higher incidence of severe SRs than their non-atopic peers (36.9% vs. 24.8%), suggesting that atopic status represents an additional risk factor [59]. Other studies have shown that only the presence and severity of asthma appear to correlate with the intensity of the systemic response [65,66]. Regarding age, several studies suggest that older children are at increased risk of developing SRs. The mean age at which children experienced anaphylactic reactions was lower among those allergic to honeybee venom. Furthermore, children with a honeybee venom allergy appear to be at a higher risk of SRs. However, the frequency of SRs did not differ significantly between wasp and honeybee allergies. Finally, one study reported that the site of the sting, particularly when it involves the head or neck, may be an additional risk factor for SRs [67]. However, this finding contrasts with observations in the adult population [63]. Depending on the severity of the SR, acute management may include the administration of H1-antihistamines and systemic glucocorticoids. If necessary, self-injectable epinephrine may also be used. These patients therefore require evaluation by allergy specialists who are adequately trained [62]. Numerous guidelines recommend a comprehensive allergological work-up in the presence of a suspected SR. This includes taking a detailed clinical history to identify risk factors for severe reactions, carrying out skin tests [such as SPTs and intradermal tests (IDTs)] and measuring specific serum IgE to identify the causative Hymenoptera species. Additional diagnostic tools may be employed in more complex cases, such as capillary-based allergen-specific immunoassay inhibition (CAP) and the BAT [8,61,62,68,69]. All patients with a history of anaphylaxis, as well as their caregivers, should be given a self-injectable epinephrine device and taught how to recognize and manage the signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis [61,62,68,69]. Children who have been prescribed a self-injectable epinephrine device should carry it with them at all times, including at school. The allergy centre must provide a medical certificate authorizing the administration of the medication during school hours [61]. Following a systemic reaction to a Hymenoptera sting, the patient should be referred to an allergologist for a diagnostic assessment, a prescription for a self-injectable epinephrine device, and an evaluation for venom-specific immunotherapy (VIT). VIT is currently the only treatment capable of altering the natural course of the disease. Studies have shown that patients undergoing VIT report a significantly better quality of life than those managed solely with epinephrine. Previous systemic reactions to hymenopteran venom have a negative impact on quality of life, particularly due to anxiety about potential future stings and fear of fatal outcomes. In children, this emotional burden naturally extends to their caregivers as well [8,61].

Recommendation (Table 7): For children and adolescents experiencing systemic reactions to hymenopteran stings, referral to an allergy specialist is recommended rather than being managed by a pediatrician alone. This allows for an accurate diagnosis, identification of risk factors for severe systemic reactions, education of patients on how to manage future stings and the prescription of self-injectable adrenaline. If indicated, it also allows for the initiation of venom-specific immunotherapy. This is the only treatment capable of altering the natural progression of the disease, thereby also improving quality of life.

Table 7.

Summary of evidence and main recommendations on the role of the referral to an allergy specialist over management by the primary care pediatrician in order to assess the risk of anaphylaxis and initiate preventive treatment among children and adolescents with systemic reactions to hymenopteran stings.

PICO 2

For children and adolescents suspected of having a HVA with systemic reactions (P), is it more strongly recommended that specific diagnostic tests (skin testing and measurement of specific IgE) are performed (I) than clinical follow-up alone (C), in order to improve diagnostic accuracy and guide therapeutic decision-making (O)?

Evidence (Quantitative analysis): Due to the heterogenous design of retrieved studies, both in terms of targeted population and included outcomes, no quantitative summary of evidence was ultimately performed by means of a meta-analytical approach.

Evidence (Narrative report): According to the EAACI guidelines on allergen immunotherapy (AIT) for HVA, AIT is indicated for both children and adults who have experienced systemic allergic reactions extending beyond generalized cutaneous symptoms. Sensitization to the venom of the culprit Hymenoptera species must be documented and confirmed through an appropriate allergological investigation. To initiate AIT, it is essential to accurately identify the venom to which the patient is sensitized and has a clinical reaction to. The diagnostic goals are to determine the reaction type, confirm an IgE-mediated mechanism and identify the causative insect. Correct identification of the offending insect is an essential step in the diagnostic process. Bilò and Giovannini reported that combining an entomological chart with a detailed clinical history during the allergological consultation enabled the culprit insect to be accurately identified in around 73% of cases [8,70]. In a multicentre study, Baker et al. demonstrated that allergologists have significantly greater expertise in identifying insects of the order Hymenoptera than their non-allergologist colleagues [71]. Skin testing using venom extracts and measurement of sIgE, should be performed in all patients with a history of systemic reactions, as recommended by all major guidelines [8,61,62,68,69,72,73]. For patients with significant local reactions, diagnostic testing is optional and should consider the patient’s age (60% of systemic reactions in children are mild) as well as individual risk factors. These include a high likelihood of future stings; occupational exposure (e.g., beekeeping); pre-existing cardiovascular or respiratory diseases; use of beta-blockers or Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) inhibitors; the type of insect (in the Mediterranean area, the risk of potentially fatal reactions is approximately three times higher for hornet stings than for other wasps and honeybees); the location of the sting; elevated baseline serum tryptase levels; and the presence of mastocytosis [8]. European guidelines [72,73] recommend a stepwise approach to skin testing. This starts with the SPT, followed by the IDT if the SPT is negative. An IDT should also be performed if the SPT is positive in order to determine the intradermal endpoint, which is useful for follow-up in VIT. In fact, the SPT is less sensitive than the IDT. A recent study of 301 patients allergic to Vespula venom showed that the SPT alone identified 49% of cases, whereas the combination of the SPT and IDT allowed diagnosis in 94% of cases. This highlights the importance of performing both tests [74]. Skin testing should be conducted at least two weeks after the sting to minimize the risk of false-negative results due to the refractory period. It should also be repeated after one to two months if the initial results are negative despite a convincing clinical history of a systemic reaction [8]. The severity of the reaction is not correlated with skin test reactivity. Some authors [62] have suggested that skin testing may be omitted in the following circumstances: (1) when skin testing poses a significant risk; (2) when performing the test would significantly impact the patient; and (3) when a conclusive result has already been obtained through in vitro testing. However, skin tests should be performed when sIgE (specific immunoglobulin E) testing is negative, or when there is a discrepancy between the clinical history and laboratory findings. The sensitivity of serum testing with whole venom extracts is generally lower than that of skin tests. Up to 20% of patients with positive skin test results may have negative in vitro sIgE results, whereas approximately 10% of patients with negative skin test results may have positive in vitro sIgE results [61,70]. Therefore, current guidelines recommend carrying out both types of tests. Although specific IgE antibodies may be detectable shortly after the sting, the optimal timing for measurement is between one- and four-weeks post-sting. This may sometimes allow identification of the culprit insect. In cases of double positivity for sIgE but a positive IDT result for only one venom, VIT should be performed using the venom that tested positive in the IDT. This is because the IDT is not influenced by cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants (CCDs) [5]. One of the main diagnostic challenges arises when patients who have been stung by an unidentified insect show positive results for two different allergens in testing. Dual sensitization to Apis mellifera and Vespula occurs in 25–40% of cases. The availability of recombinant allergens enables molecular diagnosis and differentiation between true double sensitization and cross-reactivity. This approach helps to select the most appropriate venom for VIT and avoids the need for dual-venom treatment. In unclear cases, a BAT should also be performed. The BAT is particularly recommended for patients with a convincing clinical history but negative skin and sIgE tests, as well as in cases with inconclusive molecular allergen results and double sensitization [75]. In a recent observational study, the BAT demonstrated high sensitivity and a positive predictive value. The clinical sensitivities were 95.5% for Apis mellifera, 95.7% for sIgE and 48.4% for SPT; for Vespula vulgaris, these values were 83.3%, 100% and 33.3%, respectively. Based on these results, systemic reaction prediction was ranked as follows: sIgE > BAT > SPT. Dual sensitization was observed in 39.5% of patients using the diagnostic provocation test (DPT) and in 22% using sIgE testing; however, none showed dual sensitization with the BAT [75]. Therefore, the BAT plays a key role in guiding therapeutic decisions for patients with dual sensitization. Another method of distinguishing true dual sensitization from cross-reactivity is CAP inhibition; however, this test is expensive and can be difficult to interpret. In a recent observational study, Tischler et al. demonstrated that the presence of dominant sIgE with a ratio of 5:1 or higher in allergic patients with dual sensitization represents a reliable indicator for identifying the culprit venom. Based on these findings, the authors suggest that additional diagnostic investigations, such as the BAT and CAP inhibition tests, should be reserved for cases in which dual sensitization to whole venoms presents a ratio below 5:1 [76]. In cases of severe systemic reactions with confirmed dual positivity, VIT involving both venoms is recommended. Due to the risk of severe systemic reactions and their low negative predictive value, live hymenoptera challenges should not be performed [62,73]. Baseline serum tryptase levels should be measured in all patients who experience a systemic reaction to identify those at increased risk of severe reactions due to clonal mast cell disorders [69,72]. AIT is currently the only treatment that can modify the natural progression of the disease. If left untreated, the disease poses a life-threatening risk.

Recommendation (Table 8): Due to the moderate quality of evidence, a consensus-based recommendation rather than an evidence based was framed. For children and adolescents suspected of having a HVA and systemic reactions, specific diagnostic tests are preferred over simple clinical follow-up, as they improve diagnostic accuracy and inform therapeutic decisions.

Table 8.

Summary of evidence and main recommendations on the role of specific diagnostic tests (skin testing and measurement of specific IgE) over clinical follow-up alone, in order to improve diagnostic accuracy and guide therapeutic decision-making, among children and adolescents suspected of having a hymenoptera venom allergy with systemic reactions.

4. Discussion

This consensus document provides an updated, evidence-based framework for improving the appropriateness of diagnostic prescriptions in three key domains of pediatric allergology, anaphylaxis, drug allergy, and HVA. Across all areas, the findings underscore the need to reduce unwarranted diagnostic variation, streamline clinical pathways, and promote rational use of healthcare resources. The multidisciplinary composition of the expert panel, involving clinicians from primary care, emergency medicine, allergology, dermatology, immunology, psychology, and nursing, ensures that the recommendations reflect real-world practice needs and are aligned with the priorities of families, clinicians, and the healthcare system.

For children with suspected anaphylaxis, the evidence consistently supports the value of structured diagnostic evaluation over clinical follow-up alone. Measurement of acute and baseline serum tryptase can confirm mast-cell activation and assist in distinguishing true anaphylaxis from mimicking conditions, particularly in cases with an uncertain presentation. Although elevated tryptase is observed only in a subset of pediatric reactions, its incorporation into deferred-urgency evaluations enhances diagnostic reliability and helps identify individuals at increased risk due to underlying mast-cell disorders [2,21].

SPT using extracts and fresh foods remains a first-step tool to identify sensitization relevant to food-induced anaphylaxis. Results must, however, be interpreted alongside clinical history, as sensitization does not always reflect clinically reactive disease [2,38]. In selected cases, CRD provide additional molecular precision, supporting risk stratification and identification of specific allergenic proteins associated with more severe reactions. While CRD is not a stand-alone test and cannot precisely predict reaction severity, its use within specialist settings can meaningfully refine diagnostic and preventive strategies [42]. Ultimately, specialist referral after anaphylaxis remains essential to ensure allergen identification, prescription and training in AAI use, and formulation of individualized action plans [2].

Across drug allergy, particularly in suspected β-lactam allergy, the consensus reinforces a fundamental clinical message: reliance on patient history alone results in substantial overdiagnosis and unnecessary restriction of first-line antibiotics. Such over-avoidance contributes to increased use of second-line agents, higher treatment costs, and the proliferation of antimicrobial resistance. Integrating skin testing, specific IgE assays, and, most importantly, OPT significantly improves diagnostic accuracy. Evidence indicates that most children labelled as allergic can safely tolerate β-lactams when evaluated using structured protocols [4,47,48].

Direct OPT in low-risk pediatric patients has demonstrated both safety and strong diagnostic yield, and when negative, allows for immediate de-labelling. Although OPT can generate apprehension among parents, its clinical benefits, long-term safety implications, and positive impact on antimicrobial stewardship are substantial. Implementing these pathways requires access to dedicated allergy services, but the long-term cost savings, through correct antibiotic use and prevention of unnecessary referrals, support their widespread adoption [4,47,48].

For children with systemic reactions to hymenopteran stings, the consensus highlights the critical role of referral to an allergy specialist. Accurate diagnosis relies on a detailed clinical history supported by SPT or intradermal testing and determination of venom-specific IgE. In selected cases with dual sensitization or uncertain results, BAT or inhibition assays may provide additional clarity, although access may be limited.

Specialist evaluation enables appropriate prescription of AAI devices, reinforces education on sting avoidance and emergency management, and, crucially, provides access to VIT. As the only intervention capable of altering the natural course of venom allergy, VIT substantially reduces the risk of future systemic reactions and has been shown to markedly improve quality of life for both patients and caregivers. Despite these benefits, disparities in access to pediatric allergy centres remain a barrier and require coordinated efforts at the health-system level [62,68,69].

Taken together, these recommendations offer a coherent and practical roadmap for standardizing diagnostic pathways in pediatric allergology. By emphasizing targeted testing, multidisciplinary evaluation, and specialist involvement when indicated, the consensus promotes a more equitable allocation of healthcare resources and helps mitigate inappropriate practice patterns. Importantly, the recommendations also address parental expectations and the high value placed on diagnostic clarity, safety, and prevention of recurrence. Broader implementation will require dissemination of training materials, strengthening of referral networks, and investment in pediatric allergy services, but the anticipated clinical and economic benefits justify these efforts.

Despite its strengths, this work has several limitations. First, although the recommendations are grounded in systematic reviews, the evidence base for some clinical questions, particularly within pediatric drug allergy and HVA, remains limited by the scarcity of randomized trials and the predominance of observational studies. This may introduce bias and restrict the certainty of some estimates. Second, heterogeneity in study design, diagnostic protocols, and outcome definitions across the included literature limited the feasibility of performing meta-analyses for included PICOs. Moreover, the limited quality of evidence resulting from the aforementioned limits forced the Authors to frame consensus-based rather than evidence-based recommendations. Third, the availability of diagnostic tools such as CRD or BAT varies considerably across centres, which may affect the generalizability and implementation of certain recommendations. Fourth, expert consensus, while valuable, may reflect context-specific practice patterns within the Italian healthcare system and may not fully represent international diversity in clinical environments. Finally, although the multidisciplinary panel ensures comprehensive perspectives, the lack of direct patient-reported outcome data within the systematic review limits the ability to quantify the psychosocial impact of different diagnostic strategies.

5. Conclusions

This consensus document provides a comprehensive, evidence-based framework to support more appropriate, consistent, and clinically effective diagnostic practices in pediatric anaphylaxis, drug allergy, and hymenoptera venom allergy. By integrating current scientific evidence with expert multidisciplinary insight, these recommendations aim to reduce unwarranted variability, improve diagnostic precision, and ensure timely access to specialist evaluation when needed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm15020678/s1, Table S1. PRISMA checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.E.; methodology, V.F., M.R., M.C., F.C., A.L., D.P. and C.C., validation, V.F., M.R. and S.E., formal analysis, V.F. and M.R.; investigation, V.F., E.V.B., R.C. and D.C., data curation, V.F., M.R., E.V.B., R.C. and D.C., writing—original draft preparation, V.F., M.R., E.V.B., R.C., D.C., C.C. and S.E., writing—review and editing, R.A., S.B., M.C., F.C., E.C., M.A.C., M.E., A.L., M.M.D.G., M.M., I.N., R.N., D.P., C.P., G.P., G.S., M.A.T., C.C. and S.E. supervision, M.C., F.C., A.L., D.P., C.C. and S.E., project administration, S.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

Elena Cinti, UOC Clinica Pediatrica, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria, Parma. Cristina Marchesi, Istituto Romagnolo per lo Studio dei Tumori (IRST) Dino Amadori IRCSS, Medola (Forlì’ Cesena), Italy. Gian Luigi Marseglia, Società Italiana di Allergologia e Immunologia Pediatrica (SIAIP), UOC Clinica Pediatrica, IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia, Italy, Claudia Borrelli, Tommaso Carretta Antonella Giudice, Roberto Grandinetti, Anna Montanari, Elisabetta Palazzolo and Arianna Rossi, Pediatric Clinic, Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Parma, Parma, Italy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Summary of search strategies.

Table A1.

Summary of search strategies.

| Topic | PICO | PubMed | Embase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anaphylaxis | 1 | (“Ambulatory Care”[Mesh] OR “Day Care, Medical”[Mesh] OR “home visit*” OR “outpatient*”) AND (“Anaphylaxis”[Mesh] OR “Hypersensitivity, Immediate”[Mesh]) AND (“Emergency Medical Services”[Mesh] OR “Self Administration”[Mesh] OR “Epinephrine”[Mesh]) AND (“Tryptases”[MeSH] OR tryptase[tiab] OR “serum tryptase”[tiab] OR “mast cell tryptase”[tiab] OR “tryptase level”[tiab] OR “baseline tryptase”[tiab] OR “acute tryptase”[tiab]) AND (“Child”[MeSH] OR “Adolescent”[MeSH] OR child*[tiab] OR pediatric*[tiab] OR pediatric*[tiab] OR adolescen*[tiab]) | (‘ambulatory care’/exp OR ‘ambulatory care’ OR ‘day care’ OR ‘home visit’ OR ‘outpatient’) AND (‘anaphylaxis’ OR ‘hypersensitivity’) AND (‘emergency health service’ OR ‘drug self administration’ OR ‘epinephrine’) AND (‘tryptase’) AND ([adolescent]/lim OR [child]/lim OR [newborn]/lim OR [preschool]/lim) |

| 2 | (“Anaphylaxis”[MeSH] OR anaphylaxis[tiab] OR anaphylactic[tiab]) AND (“Tryptases”[MeSH] OR tryptase[tiab] OR “serum tryptase”[tiab] OR “mast cell tryptase”[tiab] OR “tryptase level”[tiab] OR “baseline tryptase”[tiab] OR “acute tryptase”[tiab]) AND (“Child”[MeSH] OR “Adolescent”[MeSH] OR child*[tiab] OR pediatric*[tiab] OR pediatric*[tiab] OR adolescen*[tiab]) | (‘anaphylaxis’ OR ‘hypersensitivity’) AND (‘tryptase’ OR ‘tryptase test kit’ OR ‘tryptase blood level’) AND ([adolescent]/lim OR [child]/lim OR [newborn]/lim OR [preschool]/lim) | |

| 3 | ((“Food Hypersensitivity”[MeSH] OR “Food Hypersensitivity”[tiab] OR “food allergy”[tiab] OR “food-induced allergy”[tiab] OR “food-induced anaphylaxis”[tiab] OR “food allergy–related anaphylaxis”[tiab]) AND (“Anaphylaxis”[MeSH] OR anaphylaxis[tiab]) AND (“Skin Tests”[MeSH] OR “skin prick test”[tiab] OR “skin-prick test”[tiab] OR “SPT”[tiab] OR “prick test”[tiab]) AND (“Child”[MeSH] OR “Adolescent”[MeSH] OR child*[tiab] OR pediatric*[tiab] OR pediatric*[tiab])) | (‘food allergy’ AND (‘anaphylaxis’ OR ‘hypersensitivity’)) AND ([adolescent]/lim OR [child]/lim OR [newborn]/lim OR [preschool]/lim) AND (‘skin test’ OR ‘prick test’) | |

| 4 | (“Anaphylaxis”[MeSH] OR anaphylaxis[tiab] OR anaphylactic[tiab]) AND (“Immunoglobulin E”[MeSH] OR “specific IgE”[tiab] OR “specific IgE”[MeSH] OR “component resolved”[tiab] OR “component-resolved”[tiab] OR “component resolved diagnostics”[tiab] OR “component-resolved diagnostics”[tiab] OR CRD[tiab] OR “molecular allergology”[tiab]) AND (“Child”[MeSH] OR “Adolescent”[MeSH] OR child*[tiab] OR pediatric*[tiab] OR pediatric*[tiab] OR adolescen*[tiab]) | (‘anaphylaxis’ OR ‘hypersensitivity’) AND ([adolescent]/lim OR [child]/lim OR [newborn]/lim OR [preschool]/lim) AND (‘immunoglobulin’ OR ‘immunoglobulin e’ OR ‘component resolved diagnosis’ OR ‘component resolved diagnostics’ OR (molecular AND allergology) | |

| Drug Allergy | 1 | (“Hypersensitivity/drug therapy”[MeSH] OR “Drug Hypersensitivity”[MeSH] OR “beta-lactams” [tiab] OR “beta lactam”[tiab] OR “penicillin allergy”[tiab] OR “penicillin hypersensitivity”[tiab] OR “cephalosporin allergy”[tiab] OR “drug allergy”[tiab]) AND (“Skin Tests”[MeSH] OR “skin prick”[tiab] OR “prick test”[tiab] OR intradermal[tiab] OR “intradermal test”[tiab]) AND (“Drug Provocation Test”[tiab] OR “oral provocation test”[tiab] OR “oral challenge”[tiab] OR “drug challenge”[tiab]) AND (“Immunoglobulin E”[MeSH] OR “specific IgE”[tiab] OR sIgE[tiab] OR “drug-specific IgE”[tiab]) AND (diagnos*[tiab] OR “diagnostic accuracy”[tiab] OR “misdiagnosis”[tiab] OR “incorrect diagnosis”[tiab] OR “false allergy”[tiab] OR sensitivity[tiab] OR specificity[tiab] OR “alternative treatment”[tiab] OR “treatment alternatives”[tiab] OR “antibiotic stewardship”[tiab]) (“Anaphylaxis”[MeSH] OR anaphylaxis[tiab] OR anaphylactic[tiab]) AND (“Tryptases”[MeSH] OR tryptase[tiab] OR “serum tryptase”[tiab] OR “mast cell tryptase”[tiab] OR “tryptase level”[tiab] OR “baseline tryptase”[tiab] OR “acute tryptase”[tiab]) AND (“Child”[MeSH] OR “Adolescent”[MeSH] OR child*[tiab] OR pediatric*[tiab] OR pediatric*[tiab] OR adolescen*[tiab]) | “(‘drug hypersensitivity’ OR ‘penicillin allergy’ OR ‘beta lactam allergy’) AND ((‘prick test’ OR ‘immunoglobulin e’ OR ‘immunological procedures’ OR ‘anamnesis’) AND (‘follow up’ OR ‘accuracy’ OR ‘diagnostic accuracy’ OR ‘therapy’))” |

| 2 | ((“beta-Lactams”[Mesh] OR “beta Lactam Antibiotics”[Mesh] OR “beta Lactam Antibiotics” [Pharmacological Action]) OR “Penicillins”[Mesh]) AND (“Drug Hypersensitivity Syndrome”[Mesh] OR “Drug Hypersensitivity”[Mesh]) AND (“Skin Tests”[Mesh] OR “Immunoglobulin E”[Mesh] OR “Follow-Up Studies”[Mesh] OR “Medical History Taking”[Mesh]) AND (“Case Management”[Mesh] OR “Patient Care Management”[Mesh] OR “Missed Diagnosis”[Mesh] OR “Quality of Life”[Mesh]) (“Anaphylaxis”[MeSH] OR anaphylaxis[tiab] OR anaphylactic[tiab]) AND (“Tryptases”[MeSH] OR tryptase[tiab] OR “serum tryptase”[tiab] OR “mast cell tryptase”[tiab] OR “tryptase level”[tiab] OR “baseline tryptase”[tiab] OR “acute tryptase”[tiab]) AND (“Child”[MeSH] OR “Adolescent”[MeSH] OR child*[tiab] OR pediatric*[tiab] OR pediatric*[tiab] OR adolescen*[tiab]) | (‘drug hypersensitivity’ OR ‘penicillin allergy’ OR ‘beta lactam allergy’) AND ((‘prick test’ OR ‘immunoglobulin e’ OR ‘immunological procedures’ OR ‘anamnesis’) AND (‘follow up’ OR ‘accuracy’ OR ‘diagnostic accuracy’ OR ‘therapy’))” | |

| Hymenoptera Venom Allergy | 1 | (“Arthropod Venoms”[Mesh] OR “Bee Venoms”[Mesh] OR “Venom Hypersensitivity”[Mesh]) AND ((“Allergy and Immunology”[Mesh] AND (“Ambulatory Care”[Mesh] OR “Office Visits”[Mesh])) OR (“Pediatrics”[Mesh] AND (“Ambulatory Care”[Mesh] OR “Office Visits”[Mesh])) AND (“Anaphylaxis”[Mesh]) OR “Recurrence”[Mesh] OR “Immunomodulation”[Mesh] OR “Immunotherapy, Active”[Mesh]) (“Anaphylaxis”[MeSH] OR anaphylaxis[tiab] OR anaphylactic[tiab]) AND (“Tryptases”[MeSH] OR tryptase[tiab] OR “serum tryptase”[tiab] OR “mast cell tryptase”[tiab] OR “tryptase level”[tiab] OR “baseline tryptase”[tiab] OR “acute tryptase”[tiab]) AND (“Child”[MeSH] OR “Adolescent”[MeSH] OR child*[tiab] OR pediatric*[tiab] OR pediatric*[tiab] OR adolescen*[tiab]) | ((‘hymenoptera’/exp OR ‘hymenoptera’) OR ‘insect venom’ OR ‘hymenoptera venom’ OR ‘hymenoptera venom allergy’) AND (‘immunology’ AND (‘outpatient’ OR ‘ambulatory care’ OR ‘hospital visit’) OR (‘pediatrics’ AND (‘outpatient’ OR ‘ambulatory care’ OR ‘hospital visit’))) AND (‘immunomodulation’ OR ‘immunotherapy’ OR ‘anaphylaxis’ OR ‘relapse’ OR ‘recurrent disease’ OR ‘recurrence risk’) |

| 2 | (“Hymenoptera Venoms”[MeSH] OR “Insect Stings”[MeSH] OR hymenoptera[tiab] OR “insect sting”[tiab]) AND (“Skin Tests”[MeSH] OR prick[tiab] OR intradermal[tiab]) AND (“Immunoglobulin E”[MeSH] OR “specific IgE”[tiab] OR sIgE[tiab]) AND (“Basophil Activation Test”[tiab] OR BAT[tiab]) AND (diagnos*[tiab] OR “diagnostic accuracy”[tiab] OR sensitivity[tiab] OR specificity[tiab]) (“Anaphylaxis”[MeSH] OR anaphylaxis[tiab] OR anaphylactic[tiab]) AND (“Tryptases”[MeSH] OR tryptase[tiab] OR “serum tryptase”[tiab] OR “mast cell tryptase”[tiab] OR “tryptase level”[tiab] OR “baseline tryptase”[tiab] OR “acute tryptase”[tiab]) AND (“Child”[MeSH] OR “Adolescent”[MeSH] OR child*[tiab] OR pediatric*[tiab] OR pediatric*[tiab] OR adolescen*[tiab]) | (‘hymenoptera venom allergy’ OR ‘bee venom extract’ OR ‘insect allergy’) AND (‘prick test’ OR ‘immunoglobulin e’ OR ‘immunological procedures’ OR ‘anamnesis’) AND (‘follow up’ OR ‘accuracy’ OR ‘diagnostic accuracy’ OR ‘therapy’) |

Table A2.

Appraisal of the risk of Bias of observational studies according to Newcastle Ottawa Scale (range 0–9) [14,77].

Table A2.

Appraisal of the risk of Bias of observational studies according to Newcastle Ottawa Scale (range 0–9) [14,77].

| Author | Year | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | D6 | D7 | D8 | D9 | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaphylaxis | |||||||||||

| De Schryver S et al. [33] | 2016 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 7 | ||

| Cavkaytar et al. [34] | 2016 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 6 | |||

| Le M. et al. [78] | 2018 | + | + | + | + | + | 5 | ||||

| Vetander M. et al. [38] | 2016 | + | + | + | + | + | 5 | ||||

| Clark E. et al. [32] | 2023 | + | + | + | + | + | 5 | ||||

| Burrell S. et al. [27] | 2021 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 6 | |||

| Drug allergy | |||||||||||

| Moral et al. [53] | 2022 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 6 | 1 | ||

| Goh et al. [49] | 2021 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 6 | 1 | ||

| Labrosse et al. [52] | 2020 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 6 | 1 | ||

| Mill et al. [57] | 2016 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 6 | 1 | ||

| Hymenoptera Venom Allergy | |||||||||||

| Worm et al. [60] | 2014 | + | + | + | 3 | ||||||

| Quercia et al. [58] | 2014 | + | + | + | + | 4 | |||||

| Graif et al. [79] | 2009 | + | + | + | + | + | 5 | ||||

| Tischler et al. [76] | 2025 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 6 | |||

| Baker et al. [71] | 2016 | + | + | + | + | 4 | |||||

| Kokcu Karadag et al. [75] | 2024 | + | + | 2 | |||||||