Abstract

Background: Manual wheelchairs (MWCs) are critical assistive devices for individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) and other mobility impairments. However, inconsistencies exist in evaluating usability across different manual wheelchair designs. Usability evaluation methods are essential to ensure optimal design and function. Methods: A systematic review following PRISMA guidelines was conducted. Databases searched included PubMed, ScienceDirect, and DBpia. A comprehensive search was completed up to April 2024. Keywords combined concepts such as “spinal cord injury”, “manual wheelchair”, and “usability evaluation” using Boolean operators (AND, OR) and truncation strategies. Results: From 2134 initial records, 30 studies met the inclusion criteria. Studies included individuals with SCI as the primary population, but also incorporated able-bodied participants when necessary to simulate conditions not feasible for SCI users. Evaluation methods included objective assessments (e.g., kinematics, kinetics, electromyography) and subjective measures (e.g., System Usability Scale, user interviews). Conclusions: This review highlights methodological trends in MWC usability testing and identifies key metrics to guide future research and design improvements. While the primary focus was on individuals with SCI, studies involving healthy participants were included where ethically or practically justified.

1. Introduction

Manual wheelchair (MWC) use is often regarded as a physically demanding and inefficient form of mobility, particularly for individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI), due to its association with repetitive upper limb strain and long-term musculoskeletal complications [1,2]. The upper limbs, which are essential for propulsion via hand rims, are highly vulnerable to discomfort and injury. Numerous studies have reported a high prevalence of shoulder pain and overuse injuries among MWC users [3,4,5], especially among individuals with SCI, resulting in decreased independence and quality of life [6]. These complications not only impair mobility but also restrict other daily living activities involving upper limb function.

In response to these challenges, various alternative propulsion mechanisms have been developed. For example, pushrim-activated power-assist wheelchairs (PAPAWs) incorporate motorized components that support propulsion through battery-powered systems [7], targeting users with SCI, upper limb pain, or general muscle weakness [8]. However, such models typically increase the weight of the wheelchair and limit maneuverability. Lever-propelled wheelchairs provide biomechanically favorable propulsion movements and are effective for outdoor use, yet their restricted hand path and reduced efficiency pose limitations [9,10,11,12]. However, similar to PAPAWs, they restrict hand movement to a fixed trajectory and reportedly exhibit lower propulsion efficiency [13,14,15].

To address these issues comprehensively, usability evaluation has emerged as a central criterion for developing and refining manual wheelchair systems. According to ISO 9241-11 [16], usability is “the extent to which specified users can use a product to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction in a specified context of use”. This review adopts that framework to evaluate usability testing methodologies in MWCs, emphasizing user-centered outcomes.

While individuals with SCI represent this review’s core population of interest, several included studies used able-bodied participants. These participants were typically involved in simulations where experimental risks, ethical limitations, or technical constraints made direct inclusion of SCI users difficult. Therefore, their inclusion was justified in cases where the usability dimension, such as propulsion effort or device handling, could be objectively assessed through analogous tasks.

This study aims to systematically categorize and analyze existing usability evaluation methods for manual wheelchairs, examining their application across different wheelchair designs and user groups. By reviewing both conventional and novel MWC types, the study seeks to (1) identify key usability evaluation tools, (2) uncover practical user demands based on experimental outcomes, and (3) provide strategic guidance for the future development of effective, user-responsive manual wheelchairs, particularly for individuals with SCI. Although this review primarily focused on individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI), several studies involving able-bodied participants were included when safety concerns or feasibility issues precluded direct testing with SCI individuals. These inclusions were carefully justified to ensure relevance and applicability to the SCI population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This systematic review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

The PICOS framework was used during the study design phase to establish the criteria for selecting relevant studies (Table 1). P (participants) was individuals with SCI; C (comparison) was the control group for randomized controlled trials; and S (study design) was the experimental studies. Among groups of individuals that use MWC, individuals with SCI were selected as the study population because of their reliance on wheelchairs for daily activities and mobility. Moreover, prolonged wheelchair use in this population imposes repetitive loads on the upper limbs, often resulting in shoulder joint damage, pain, and various associated conditions [17]. I (intervention) was not applicable to this study, as the focus was to review the results of usability testing for MWCs. O (outcome) was not specified to allow for a broad examination of the methods and results of the usability testing.

Table 1.

PICOS.

2.2. Literature Search

Academic journal publications (excluding theses and abstracts) were included in this systematic review. Searches were conducted over seven days in two rounds: from March 27 to April 1, 2024 (first round) and April 24 to 26, 2024 (second round), to ensure comprehensive coverage of recently published studies. The literature was retrieved using PubMed and ScienceDirect for international articles, and DBpia for Korean language publications. A comprehensive search was conducted across PubMed, ScienceDirect, and DBpia up to April 2024. No additional updated search was performed after this period.

Keyword combinations included “spinal cord injury”, “manual wheelchair”, and “usability evaluation”, with Boolean operators and truncation strategies applied. The Advanced Research option was used for ScienceDirect, with all keywords entered into the “Find articles with these terms” field and re-entered under “Title, abstract, or author-specified keywords”. The Advanced Search feature was employed for PubMed with all keywords entered simultaneously. On DBpia, a combination of one or more keywords was used to yield diverse results, including the following:

(1) “Spinal cord, injury, manual, wheelchair, usability”;

(2) “Manual, wheelchair, usability”.

While the original PICOS criteria focused on individuals with SCI, several studies involving able-bodied participants were also included where appropriate, in order to simulate usability conditions that were not feasible or ethically suitable for direct testing with SCI participants.

2.3. Literature Selection and Classification

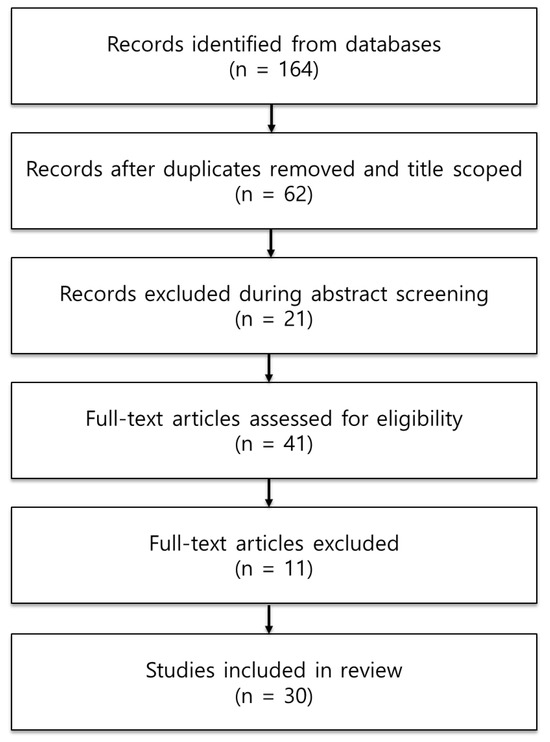

The selection and classification process adhered to the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews, which includes only databases and registers (Figure 1). During the first screening stage, the titles of retrieved articles were reviewed, and duplicates were removed. Abstracts were then evaluated to determine their relevance based on the PICOS framework. In the second screening stage, abstracts were reassessed, and articles were excluded based on the following criteria: (1) studies categorized as literature reviews or meta-analyses; (2) studies not involving individuals with SCI (e.g., usability tests using tasks unsafe for individuals with SCI or involving participants without wheelchair experience); and (3) studies not focused on MWCs (e.g., studies on powered wheelchairs, wheelchair-accessible vehicles, or wheelchair kiosks). After the screening, full texts were reviewed, and the following exclusion criteria were applied: (1) unavailable full text, (2) literature reviews and meta-analyses, (3) studies that did not involve individuals with SCI (excluding some studies), and (4) studies that did not involve MWCs. Automation tools were not used for the screening process. One researcher independently performed the classifications, and a second researcher comprehensively reviewed the results for appropriateness and completeness. A total of 30 studies were selected, comprising one Korean study (Table 2) and 29 international studies (Table 3).

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews, including searches of databases and registers alone.

Table 2.

Data extracted from the Korean literature.

Table 3.

Data extracted from the international literature.

To enhance the methodological rigor of the review, all 30 included studies were appraised using a modified version of the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) checklist. Each study was evaluated across five domains: (1) clarity of study objectives, (2) adequacy of participant description, (3) validity of outcome measures, (4) transparency of usability testing procedures, and (5) appropriateness of statistical analysis. These criteria categorized studies as high, moderate, or low quality (Supplementary Table S1).

To improve the transparency of the selection process, we clarified the rationale for inclusion and exclusion based on usability testing approaches. Specifically, studies were included if they conducted structured usability evaluations involving either subjective user assessments (e.g., SUS, QUEST 2.0) or objective physiological/kinematic measurements (e.g., EMG, SMARTWheel). Studies were excluded if they (1) did not include empirical usability testing, (2) evaluated only general satisfaction or preferences without linking them to performance metrics, or (3) examined automated or powered wheelchair systems without any manual propulsion component. Additionally, while the primary focus was on individuals with SCI, some studies involving able-bodied participants were included. These cases were justified when simulations were used to replicate usability conditions, such as high-speed propulsion or high-risk maneuvering, and were not feasible or ethical for direct testing with individuals with SCI.

2.4. Data Extraction

A full-text review was conducted for the 30 selected studies, and detailed data were extracted according to the study objectives and PICOS framework. The extracted data were organized into the following categories: primary author (year of publication), participants, MWC characteristics, experimental protocol, outcome measures and results, and conclusion.

The participants in the selected studies were predominantly individuals with SCI, as defined by the PICOS framework. However, a few studies included participants with other conditions, such as multiple sclerosis. Additionally, some studies involved individuals without disabilities when tasks in the usability tests were unsuitable or unsafe for individuals with SCI or when participants lacked prior wheelchair experience. Some of these studies were included to provide a comprehensive analysis of various findings related to MWC usability that align with the objectives of the review.

For the experimental protocol, details such as the experimental conditions for MWC use, utilization of motion analysis systems, and inclusion of electromyography (EMG) sensors were separately categorized and documented. The sequence of the experimental procedures was recorded based on the tasks performed by the participants.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

The demographic data of the participants included various SCI-related characteristics, including duration of injury, level and grade of impairment, complete/incomplete injury, and location of the spinal cord lesion. Most participants with SCI had prior experience with MWCs or had used MWCs as their primary mobility aid. Among four studies that involved individuals without disabilities [15,30,36,41], two included participants with no prior wheelchair experience. Pain assessments or questions were administered in 18 studies, with 7 utilizing the Wheelchair User’s Shoulder Pain Index (WUSPI) or its variant, PC-WUSPI, at baseline.

3.2. Characteristics of MWCs Used in the Experiment

The MWCs used in the experiments fell into three broad categories: (1) MWCs previously used by the participants, (2) PAPAWs, and (3) MWCs with new features or propulsion mechanisms. Seven studies compared standard MWCs with PAPAWs, which are equipped with DC motors installed in the rear wheel hubs to supplement propulsion based on the user’s pushrim input. PAPAWs have shown great potential for improving MWC usability among individuals with SCI [8,37,46]. Six studies evaluated MWCs with new features or propulsion systems, including (1) two-speed MWCs utilizing planetary gear trains [19,20], (2) MWCs equipped with two types of anti-rollback devices [22], (3) MWCs featuring a pulley–cable propulsion system utilizing a rowing gesture [30], (4) MWCs employing an ergonomic hand drive mechanism (EHDM) with a cam-pawl and ratchet system [32], and (5) MWCs with 12 configurations combining three seat heights and four antero-posterior axle positions [8]. Three of the six studies (50%) focused on developing and evaluating the usability of new propulsion systems for MWCs, highlighting the importance of developing advanced propulsion mechanisms to improve usability and prevent injuries.

In 12 studies, specialized wheels (SMARTWheel, Intelliwheel, and Propulsiometer) were attached to MWCs to measure kinetic data, including force and torque. Additionally, three studies utilized strain-gauge force transducers; one used a Hall sensor, and another employed a six-degree-of-freedom force transducer. Three studies [31,36,42] analyzed stroke patterns rather than the mechanical properties of MWCs.

3.3. Methods of Evaluation

The experimental conditions (driving conditions) were categorized as follows: (1) flat surfaces, such as tiles, carpets, and track fields, as well as ramps and curbs (6 studies); (2) rollers and ergometers (dynamometers) (16 studies); (3) treadmills (5 studies); (4) course driving (2 studies); and (5) wheelchair skill tests (WSTs) (1 study). For the two studies on course driving, Guillon et al. [27] developed indoor and outdoor driving courses to evaluate the participants’ wheelchair-handling abilities under diverse terrain conditions, whereas Algood et al. [40] designed a multi-obstacle course that incorporated indoor and outdoor environments to assess the practicality of wheelchair use. The details of the courses are provided in Table 4. Wheelchair driving speeds were categorized into three settings: (1) self-selected speed, (2) predefined steady-state speeds, and (3) maximal acceleration conditions (acceleration trials). More than half of the studies (16 studies) adopted the self-selected speed approach. The conditions in the predefined steady-state speed included 0.56 m/s, 0.83 m/s (3 km/h), 0.9 m/s (2 mph), and 1.8 m/s (4 mph). One study [36] used a metronome to ensure steady-state driving. The usability evaluation methods employed in each study—including evaluation type, tool, and setting—are summarized in Table 4. This table categorizes studies by subjective/objective design, assessment tools, and evaluation conditions. Driving course details—including indoor and outdoor conditions used in usability assessments—are listed in Table 5. These environments helped simulate real-world use conditions.

Table 4.

Usability evaluation methods by study.

Table 5.

Experimental conditions (driving conditions)–course driving.

3.4. Outcome Measures and Results

Seventeen studies employed motion analysis systems, whereas six utilized EMG sensors. Five studies combined motion analysis systems and EMG sensors in their experiments. The anatomical landmarks and sensor placement locations based on these systems are summarized in Table 5. Studies that collected data from either the dominant or non-dominant side of participants provided specific justifications for their selection: The dominant side was chosen to simulate a painful region [26], whereas the non-dominant side was selected owing to its potential impact on curb-climbing tasks [21]. Seven studies included physiological measurements, including heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen consumption and ventilation, VO2 efficiency, and energy cost (L/m). Six studies, including a Korean study, employed the usability test tools for participants’ subjective assessments. The tools included SUS, Borg RPE Scale, a custom-designed functional rating scale [22], QUEST 2.0 (Quebec User Evaluation of Satisfaction with assistive Technology), satisfaction evaluations using the visual analog scale [27], obstacle completion difficulty and ergonomic evaluation using the visual analog scale [40], WST, WheelConP-SF, WheelCon-M-SF, and NASA-TLX. Although most studies measured and statistically analyzed variables, such as velocity, range of motion (ROM), force, and moment to determine outcomes, some uniquely focused on spinal curvature, shoulder pathology, and nerve conduction data to explore their associations with physical changes related to MWC use. Additional outcome measures included the number of stops or collisions during tasks, time to complete tasks, self-reported discomfort or pain, and number of participants requiring assistance to complete tasks. Table 6 provides a side-by-side comparison of subjective and objective usability outcomes. It summarizes the tools used and key results, revealing consistencies and divergences in user perception versus biomechanical data. The sensor placement locations for motion and biomechanical analysis are presented in Table 7, which identifies anatomical and wheelchair landmarks used for data collection.

Table 6.

Comparison of subjective and objective usability outcomes.

Table 7.

Motion analysis data—sensor placement.

To enhance interpretability, we synthesized the results across propulsion technology types and summarized their respective strengths and limitations in a new comparative table (Table 8). This table integrates both objective and subjective findings, helping to clarify which technologies demonstrated superior usability outcomes in terms of biomechanical performance and user satisfaction. Such classification aids clinicians and designers in identifying the most promising design directions.

Table 8.

Comparative summary of propulsion technologies.

4. Discussion

This systematic review aimed to categorize and evaluate the usability assessment methods employed in manual wheelchair (MWC) studies across diverse user groups, focusing on individuals with spinal cord injuries (SCI). The primary objective was to determine how usability is evaluated—subjectively and objectively—and to identify trends in testing environments, propulsion mechanisms, and outcome metrics.

The reviewed studies employed a variety of usability evaluation methods. As summarized in Table 4 and Table 6, subjective evaluation tools, such as SUS, QUEST 2.0, and NASA-TLX, were used in a minority of studies. In contrast, objective assessments using motion capture, EMG, and kinetic sensors (e.g., SMARTWheel) were more frequently applied. However, only a few studies integrated both approaches. The limited use of comprehensive tools suggests a gap in evaluating usability in a manner that reflects both biomechanical performance and user satisfaction.

Alternative propulsion systems—such as gear-driven, lever-propelled, and pulley–cable mechanisms—have demonstrated potential for reducing physical strain during wheelchair use. Jahanian et al. [2,19,20] and Cavallone et al. [30] reported that these technologies improved biomechanical efficiency without compromising function. These findings align with Table 6, illustrating variations in subjective and objective outcomes depending on the propulsion type. While motion analysis and kinetic data remain central in MWC studies, user-centered evaluation remains underutilized. Only 6 of the 30 studies included subjective assessment tools, and only two incorporated in-depth interviews. As shown in Table 6, user satisfaction data—when collected—often diverged from biomechanical results, highlighting the necessity of dual-perspective evaluations. Training and adaptation protocols also emerged as a key usability factor. Mattie et al. [47] and Kim et al. [18] emphasized the role of structured learning in reducing user discomfort and increasing confidence. Incorporating such procedures in usability studies can reduce outcome variability and improve ecological validity. Moreover, the sensor placement patterns detailed in Table 7 underscore the importance of methodological consistency in motion and EMG assessments. Standardized anatomical and wheelchair landmarks can facilitate cross-study comparisons and better quantify performance outcomes.

From a clinical perspective, one of the most significant practical findings of this systematic review is that alternative propulsion technologies—such as PAPAWs, lever-drive systems, and pulley–cable mechanisms—consistently demonstrate biomechanical advantages that reduce shoulder joint stress and muscular effort. These findings have clear implications for rehabilitation specialists, occupational therapists, and assistive technology professionals tasked with recommending or customizing wheelchairs for long-term users. For instance, PAPAWs and planetary gear systems showed consistent reductions in peak propulsion forces, suggesting that these systems may delay the onset of shoulder pain or injury in high-risk users with SCI. Clinicians should consider integrating such technologies into early-stage mobility training programs to prevent musculoskeletal complications. Additionally, pulley–cable systems—by activating antagonist muscle groups—may offer therapeutic benefits for maintaining upper extremity balance and coordination. Furthermore, the heterogeneity in usability evaluation methods across studies highlights the need for developing standardized clinical protocols that integrate both biomechanical data and user feedback. This dual-approach framework would enable evidence-based selection and customization of MWCs aligned with users’ functional profiles, thereby optimizing both safety and long-term satisfaction. In practice, usability test outcomes should not remain confined to laboratory or engineering settings. Instead, they should inform clinical decision-making processes—particularly in tailoring training interventions, evaluating readiness for independent mobility, and selecting propulsion mechanisms suited to patients’ physical limitations and environmental demands.

In sum, the usability evaluation of MWCs should integrate objective performance data with subjective user experiences. This would ensure that technological improvements translate into real-world benefits for individuals with SCI. Future studies should adopt multidimensional evaluation frameworks that include (1) validated, user-centered tools, (2) structured adaptation protocols, and (3) consistent sensor methodology. Such approaches will improve the interpretability of MWC usability data and enhance the design of assistive devices that are truly responsive to user needs.

Based on the findings of this review, several specific recommendations can be made to guide future wheelchair design and usability research. First, alternative propulsion systems should be developed with careful attention to minimizing joint-specific strain, especially at the shoulder and wrist, as biomechanical analyses have shown that these joints are most vulnerable to overuse injuries. For example, pulley–cable or lever-based systems may help distribute load more evenly across muscle groups. Second, designers should consider integrating adjustable configurations—such as seat height, axle position, and propulsion handle orientation—based on users’ body size, level of injury, and propulsion technique. Studies in this review demonstrated that even subtle configuration differences can significantly affect propulsion efficiency and comfort. Third, usability testing protocols should include both subjective (e.g., SUS, QUEST 2.0, NASA-TLX) and objective (e.g., EMG, kinematic/kinetic) evaluations to ensure that designs align with both user perception and biomechanical safety. Fourth, future research should prioritize long-term usability studies that simulate real-world conditions, including obstacle navigation and transfers, which better reflect daily user experiences. Finally, interdisciplinary collaboration between engineers, clinicians, and end-users is critical to ensure that design innovations are functional, safe, and aligned with the diverse needs of manual wheelchair users. These recommendations offer a more actionable roadmap for researchers and practitioners seeking to improve manual wheelchair usability across varied user populations.

This review is novel in systematically integrating both objective biomechanical evaluations and subjective user-centered assessments across diverse propulsion technologies. It advances the field by clarifying which usability measures are most informative for both research and clinical practice. Furthermore, by addressing multiple user populations, the findings offer more generalizable insights applicable beyond individuals with SCI alone. For clinicians, the findings suggest evidence-based recommendations for wheelchair selection and configuration, aiming to reduce upper extremity strain and improve mobility outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review categorized and analyzed 30 studies that assessed the usability of manual wheelchairs (MWCs) across diverse user groups, including, but not limited to, individuals with spinal cord injuries (SCI). The review found that while a range of alternative propulsion systems—such as lever-crank, gear-driven, and pulley–cable mechanisms—have been developed to reduce upper limb strain, usability testing remains inconsistent across studies.

Most studies focused on objective data such as motion analysis or electromyography, while relatively few incorporated subjective tools or user feedback through interviews or questionnaires. As a result, the practical utility and perceived satisfaction with new wheelchair designs remain insufficiently explored. Furthermore, the expression of “effectiveness” varied widely across studies, and no standardized metrics were used to compare usability outcomes.

Future studies should adopt integrated evaluation frameworks that combine objective biomechanical data with subjective user experience measures to enhance the real-world impact of MWC innovations. Establishing standardized usability evaluation protocols is critical to ensuring that assistive technologies are functionally beneficial, accepted, and valued by users daily.

This review mapped the landscape of manual wheelchair usability evaluation methods, identifying critical gaps and proposing standardized approaches for future studies. While the primary focus remained on individuals with SCI, findings highlight the need to validate usability outcomes across broader user groups. Integrating objective biomechanical metrics and subjective user satisfaction measures will be crucial for advancing evidence-based wheelchair design and clinical decision-making.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm14093184/s1, Table S1: Methodological Quality Assessment of Included Studies. References [48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57] are cited in the supplementary materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P., J.K., S.-D.E. and D.K.; methodology, J.P., J.K. and D.K.; formal analysis, J.P., J.K. and D.K.; investigation, J.P., J.K. and D.K.; resources, J.P., J.K. and D.K.; data curation, J.P. and J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P., J.K. and D.K.; writing—review and editing, J.P. and D.K.; visualization, J.P., J.K. and D.K.; project administration, J.P., S.-D.E. and D.K.; funding acquisition, S.-D.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Assistive Technology Commercialize R&D Project for Independent Living for People with Disability and Older People by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: RS-2024-00398486).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (J.P.) upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the research teams involved in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Divanoglou, A.; Augutis, M.; Sveinsson, T.; Hultling, C.; Levi, R. Self-reported health problems and prioritized goals in community-dwelling individuals with spinal cord injury in Sweden. J. Rehabil. Med. 2018, 50, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahanian, O.; Van Straaten, M.G.; Goodwin, B.M.; Lennon, R.J.; Barlow, J.D.; Murthy, N.S.; Morrow, M.M.B. Shoulder magnetic resonance imaging findings in manual wheelchair users with spinal cord injury. J. Spinal Cord. Med. 2022, 45, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, K.A.; Roach, K.E.; Applegate, E.B.; Amar, T.; Benbow, C.S.; Genecco, T.D.; Gualano, J. Reliability and validity of the wheelchair user’s shoulder pain index (WUSPI). Paraplegia 1995, 33, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.A.; Boninger, M.L.; Robertson, R.N. Repetitive strain injury among manual wheelchair users. Team Rehab Rep. 1998, 9, 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mozingo, J.D.; Akbari-Shandiz, M.; Murthy, N.S.; Van Straaten, M.G.; Schueler, B.A.; Holmes III, D.R.; McCollough, C.H.; Zhao, K.D. Shoulder mechanical impingement risk associated with manual wheelchair tasks in individuals with spinal cord injury. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol) 2020, 71, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, C.; Beck, C.L.; Sosnoff, J.J. Shoulder pain and jerk during recovery phase of manual wheelchair propulsion. J. Biomech. 2015, 48, 3937–3944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmarkar, A.; Cooper, R.A.; Liu, H.Y.; Connor, S.; Puhlman, J. Evaluation of pushrim-activated power-assisted wheelchairs using ANSI/RESNA standards. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2008, 89, 1191–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, R.A.; Fitzgerald, S.G.; Boninger, M.L.; Prins, K.; Rentschler, A.J.; Arva, J.; O’Connor, T.J. Evaluation of a pushrim-activated, power-assisted wheelchair. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2001, 82, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemmer, C.L.; Flemmer, R.C. A review of manual wheelchairs. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2016, 11, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Woude, L.H.; Dallmeijer, A.J.; Janssen, T.W.; Veeger, D. Alternative modes of manual wheelchair ambulation: An overview. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2001, 80, 765–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Woude, L.H.V.; de Groot, S.; Janssen, T.W.J. Manual wheelchairs: Research and innovation in rehabilitation, sports, daily life and health. Med. Eng. Phys. 2006, 28, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lui, J.; MacGillivray, M.K.; Sheel, A.W.; Jeyasurya, J.; Sadeghi, M.; Sawatzky, B.J. Mechanical efficiency of two commercial lever-propulsion mechanisms for manual wheelchair locomotion. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2013, 50, 1363–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Woude, L.H.V.; Veeger, H.E.J.; Dallmeijer, A.J.; Janssen, T.W.J.; Rozendaal, L.A. Biomechanics and physiology in active manual wheelchair propulsion. Med. Eng. Phys. 2001, 23, 713–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groot, S.; Veeger, H.E.; Hollander, A.P.; van der Woude, L.H. Effect of wheelchair stroke pattern on mechanical efficiency. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2004, 83, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bregman, D.J.J.; Van Drongelen, S.; Veeger, H.E.J. Is effective force application in handrim wheelchair propulsion also efficient? Clin. Biomech. (Bristol) 2009, 24, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 9241-11; Ergonomics of Human-System Interaction—Part 11: Usability: Definitions and Concepts. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Cratsenberg, K.A.; Deitrick, C.E.; Harrington, T.K.; Kopecky, N.R.; Matthews, B.D.; Ott, L.M.; Coeytaux, R.R. Effectiveness of exercise programs for management of shoulder pain in manual wheelchair users with spinal cord injury. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2015, 39, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, A.J.; Kweon, O.S.; Jung, D.H. A case study on user research for manual wheelchair use of people with spinal cord injuries. J. Korean Soc. Cult. 2018, 24, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanian, O.; Gaglio, A.; Cho, C.C.; Muqeet, V.; Smith, R.; Morrow, M.M.B.; Hsiao-Wecksler, E.T.; Slavens, B.A. Hand-rim biomechanics during geared manual wheelchair propulsion over different ground conditions in individuals with spinal cord injury. J. Biomech. 2022, 142, 111235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanian, O.; Schnorenberg, A.J.; Muqeet, V.; Hsiao-Wecksler, E.T.; Slavens, B.A. Glenohumeral joint dynamics and shoulder muscle activity during geared manual wheelchair propulsion on carpeted floor in individuals with spinal cord injury. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2022, 62, 102318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalumiere, M.; Gagnon, D.H.; Hassan, J.; Desroches, G.; Zory, R.; Pradon, D. Ascending curbs of progressively higher height increases forward trunk flexion along with upper extremity mechanical and muscular demands in manual wheelchair users with a spinal cord injury. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2013, 23, 1434–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deems-Dluhy, S.L.; Jayaraman, C.; Green, S.; Albert, M.V.; Jayaraman, A. Evaluating the functionality and usability of two novel wheelchair anti-rollback devices for ramp ascent in manual wheelchair users with spinal cord injury. PMR 2017, 9, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Agudo, A.; Del Ama-Espinosa, A.; Pérez-Rizo, E.; Pérez-Nombela, S.; Pablo Rodríguez-Rodríguez, L.P. Upper limb joint kinetics during manual wheelchair propulsion in patients with different levels of spinal cord injury. J. Biomech. 2010, 43, 2508–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newsam, C.J.; Rao, S.S.; Mulroy, S.J.; Gronley, J.K.; Bontrager, E.L.; Perry, J. Three dimensional upper extremity motion during manual wheelchair propulsion in men with different levels of spinal cord injury. Gait Posture 1999, 10, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulig, K.; Newsam, C.J.; Mulroy, S.J.; Rao, S.; Gronley, J.K.; Bontrager, E.L.; Perry, J. The effect of level of spinal cord injury on shoulder joint kinetics during manual wheelchair propulsion. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol) 2001, 16, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnet, U.; Bossuyt, F.M.; Beirens, B.J.H.; de Vries, W.H.K. Shoulder pain in persons with tetraplegia and the association with force application during manual wheelchair propulsion. Arch. Rehabil. Res. Clin. Transl. 2024, 6, 100310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillon, B.; Van-Hecke, G.; Iddir, J.; Pellegrini, N.; Beghoul, N.; Vaugier, I.; Figère, M.; Pradon, D.; Lofaso, F. Evaluation of 3 pushrim-activated power-assisted wheelchairs in patients with spinal cord injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 96, 894–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, R.; Ashwell, Z.R.; Chang, M.W.; Boninger, M.L.; Koontz, A.M.; Sisto, S.A. Upper-limb joint power and its distribution in spinal cord injured wheelchair users: Steady-state self-selected speed versus maximal acceleration trials. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2007, 88, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, M.S.; Koppens, D.; van Haaren, M.; Sherman, A.L.; Lippiatt, J.P.; Lewis, J.E. Power-assisted wheels ease energy costs and perceptual responses to wheelchair propulsion in persons with shoulder pain and spinal cord injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2008, 89, 2080–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallone, P.; Vieira, T.; Quaglia, G.; Gazzoni, M. Electromyographic activities of shoulder muscles during Handwheelchair. Med. Eng. Phys. 2022, 106, 103833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walford, S.L.; Rankin, J.W.; Mulroy, S.J.; Neptune, R.R. The relationship between the hand pattern used during fast wheelchair propulsion and shoulder pain development. J. Biomech. 2021, 116, 110202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloud, B.A.; Zhao, K.D.; Ellingson, A.M.; Nassr, A.; Windebank, A.J.; An, K.N. Increased seat dump angle in a manual wheelchair is associated with changes in thoracolumbar lordosis and scapular kinematics during propulsion. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 98, 2021–2027.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukowski, L.A.; Roper, J.A.; Shechtman, O.; Otzel, D.M.; Bouwkamp, J.; Tillman, M.D. Comparison of metabolic cost, performance, and efficiency of propulsion using an ergonomic hand drive mechanism and a conventional manual wheelchair. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 95, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowan, R.E.; Boninger, M.L.; Sawatzky, B.J.; Mazoyer, B.D.; Cooper, R.A. Preliminary outcomes of the SmartWheel Users’ Group database: A proposed framework for clinicians to objectively evaluate manual wheelchair propulsion. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2008, 89, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lighthall-Haubert, L.; Requejo, P.S.; Mulroy, S.J.; Newsam, C.J.; Bontrager, E.; Gronley, J.K.; Perry, J. Comparison of shoulder muscle electromyographic activity during standard manual wheelchair and push-rim activated power assisted wheelchair propulsion in persons with complete tetraplegia. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2009, 90, 1904–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bickelhaupt, B.; Oyama, S.; Benfield, J.; Burau, K.; Lee, S.; Trbovich, M. Effect of wheelchair stroke pattern on upper extremity muscle fatigue. PMR 2018, 10, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algood, S.D.; Cooper, R.A.; Fitzgerald, S.G.; Cooper, R.; Boninger, M.L. Impact of a pushrim-activated power-assisted wheelchair on the metabolic demands, stroke frequency, and range of motion among subjects with tetraplegia. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2004, 85, 1865–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, J.L.; Boninger, M.; Koontz, A.; Ren, D.; Dyson-Hudson, T.; Cooper, R. Shoulder joint kinetics and pathology in manual wheelchair users. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol) 2006, 21, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boninger, M.L.; Impink, B.G.; Cooper, R.A.; Koontz, A.M. Relation between median and ulnar nerve function and wrist kinematics during wheelchair propulsion. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2004, 85, 1141–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algood, S.D.; Cooper, R.A.; Fitzgerald, S.G.; Cooper, R.; Boninger, M.L. Effect of a pushrim-activated power-assist wheelchair on the functional capabilities of persons with tetraplegia. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2005, 86, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.S.; Koontz, A.M.; Triolo, R.J.; Mercer, J.L.; Boninger, M.L. Surface electromyography activity of trunk muscles during wheelchair propulsion. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol) 2006, 21, 1032–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, W.M.; Rodriguez, R.; Woods, K.R.; Axelson, P.W. Stroke pattern and handrim biomechanics for level and uphill wheelchair propulsion at self-selected speeds. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2007, 88, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinger, J.L.; Boninger, M.L.; Koontz, A.M.; Price, R.; Sisto, S.A.; Tolerico, M.L.; Cooper, R.A. Shoulder biomechanics during the push phase of wheelchair propulsion: A multisite study of persons with paraplegia. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2008, 89, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, N.; Gorce, P. Surface electromyography activity of upper limb muscle during wheelchair propulsion: Influence of wheelchair configuration. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol) 2010, 25, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arva, J.; Fitzgerald, S.G.; Cooper, R.A.; Boninger, M.L. Mechanical efficiency and user power requirement with a pushrim activated power assisted wheelchair. Med. Eng. Phys. 2001, 23, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, K.A.; Roach, K.E.; Applegate, B.E.; Amar, T.; Benbow, C.S.; Genecco, T.D.; Gualano, J. Development of the wheelchair user’s shoulder pain index (WUSPI). Spinal Cord. 1995, 33, 290–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattie, J.; Tavares, J.; Matheson, B.; Smith, E.; Denison, I.; Miller, W.C.; Borisoff, J.F. Evaluation of the Nino® two-wheeled power mobility device: A pilot study. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2020, 28, 2497–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requejo, P.; Mulroy, S.; Haubert, L.L.; Newsam, C.; Gronley, J.; Perry, J. Evidence-based strategies to preserve shoulder function in manual wheelchair users with spinal cord injury. Top. Spinal Cord. Inj. Rehabil. 2008, 13, 86–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessels, R.D.; de Witte, L.P.; Van den Heuvel, W.J.A. Measuring effectiveness of and satisfaction with assistive devices from a user perspective: An exploration of the literature. Technol. Disabil. 2004, 16, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karat, J.; Karat, C.M. The evolution of user-centered focus in the human–computer interaction field. IBM Syst. J. 2003, 42, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J. Usability Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Shackel, B. Usability—Context, framework, definition, design and evaluation. In Hum Factors Inform Usability; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- National Rehabilitation Center. Evaluation Tool for Wheelchairs and Mobility Devices; National Rehabilitation Center: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2009.

- Min, S.H.; Jeong, S.W. Development of usability evaluation scale for manual wheelchair. J. Spec. Educ. Rehabil. Sci. 2016, 55, 311–333. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Kweon, O.S.; Jeon, S.J. A study on qualitative user research method for wheelchair design of people with physical disabilities. J. Korean Soc. Cult. 2018, 24, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, M.J. Outcomes of assistive technology use on quality of life. Disabil. Rehabil. 1996, 18, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.M.; Im, S.B.; Lee, J.H. A study on assistive technology support project satisfaction of Daegu Assistive Technology Center. J. Rehabil. Res. 2013, 17, 359–375. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).