Abstract

Background/Objectives: Plaque psoriasis is a chronic immune-mediated inflammatory disease affecting approximately 3% of the global population and resulting in a significant deterioration in quality of life. Systemic therapy with monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) targeting TNF-α, IL-23, and IL-17 improves clinical outcomes and patients’ quality of life. Treatment strategies commonly include different mAbs and different sequencing approaches between agents, which are well-established in clinical practice. In contrast, evidence supporting the switch from intravenous to subcutaneous administration of the same mAb remains limited. Herein, we report data from a retrospective case series of patients with plaque psoriasis treated with intravenous infliximab (IV-IFX; Anti TNF-α) and transitioned to subcutaneous infliximab (SC-IFX) to compare clinical and patient-reported outcomes across routes. Methods: A total of 11 plaque psoriasis patients were retrospectively analyzed. The scores of the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI), Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and Physician Global Assessment (PGA) were assessed during IV-IFX and after switching to SC-IFX. To evaluate patients’ satisfaction, the Score of Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire Medication-9 (TSQM-9) was evaluated. Both Student’s t-test and ANOVA were used to assess statistically significant differences between the two routes of administration (p < 0.05). Results: Scores for PASI, DLQI, and PGA were lower with SC-IFX compared with IV-IFX, indicating improved disease control and quality of life after the switch. PASI and DLQI improved in 81% and 100% of patients treated with SC-IFX, respectively. TSQM-9 total scores increased significantly by 24% (p < 0.001). In particular, the questions addressing the “convenience” of treatment revealed a marked advantage for the SC-IFX formulation (p < 0.001). No treatment-emergent adverse events were registered. Conclusions: In this retrospective case series, switching from IV-IFX to SC-IFX appeared to be safe and to maintain or improve clinical response and enhanced treatment satisfaction. These findings highlight the potential of SC-IFX as a viable maintenance option for patients with plaque psoriasis previously treated with IV-IFX.

1. Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic disease caused by an inflammatory condition of the skin, sometimes associated with other conditions such as psoriatic arthritis, psychological, cardiovascular, and gastrointestinal disorders. The World Health Organization (WHO) [1] has considered psoriasis a serious non-communicable disease and has emphasized the importance of appropriate clinical treatments, which are often compromised due to frequent misdiagnosis [2]. Psoriasis occurs in both sexes but tends to manifest earlier in women and in those with a family history of the disease. The age of onset usually falls within two decades: between 30 and 39 years and between 60 and 69 years for men, whereas in women, the first symptoms may appear up to 10 years earlier [3,4]. The clinical manifestations of psoriasis are heterogeneous and include cutaneous and systemic manifestations [5,6]. Most commonly, psoriasis presents as plaque psoriasis (psoriasis vulgaris), occurring in 80% of cases [5,6]. Symptoms include itching, burning sensations, and skin tenderness [6,7]. Several comorbidities are associated with psoriasis, including psoriatic arthritis, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, obesity, and inflammatory bowel disease [6,7,8]. Due to these systemic implications, psoriasis is also referred to as a systemic disease [4], a pathology linked to skin barrier dysfunction [9] and metabolic syndrome [10].

The etiology of psoriasis is complex and encompasses many intrinsic and extrinsic factors [6,11,12,13,14]. Psoriasis is mainly characterized by the activation of inflammatory pathways in innate and adaptive immune cells, leading to uncontrolled keratinocyte (KC) proliferation, acanthosis, neovascularization, and dense infiltration of immune cells into the skin [15]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines primarily involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis are mainly produced by T cells (e.g., IL-17, IL-21, IL-22, IFN-γ) and dendritic cells (DCs; e.g., TNF-α, IL-6, IL-20, IL-23, NO), forming a central pathogenic loop with IL-23-producing dendritic cells, IL-17-producing Th17 cells, and activated keratinocytes (KCs) [4,5,6,11]. TNF-α initiates the inflammatory cascade in psoriasis. It is secreted in response to triggers such as skin lesions, environmental stimuli, auto-antigens, and TLR receptor agonists [16,17], mainly by activated T cells and antigen-presenting cells (APCs) [18,19]. TNF-α synergizes with IFN-γ to induce chemokine expression in endothelial cells, promoting immune cell infiltration [6,20] and stimulating KCs and DCs to secrete IL-23 [21]. Accordingly, the results of numerous genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and clinical trials support the central role of the inflammatory signaling molecular pathways of TNF-α, IL-23, and IL-17 as the “founding fathers” of the pathogenesis of psoriasis, particularly plaque psoriasis [14,22,23,24].

Both the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicine Agency (EMA) have approved different monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) for treating plaque psoriasis, targeting TNF-α (e.g., adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab) [25,26], IL-23 (e.g., risankizumab, tildrakizumab, guselkumab) [27,28], and IL-17 (e.g., secukinumab, brodalumab, bimekizumab, ixekinumab) [14,23,29]. These agents achieve PASI 90 and PASI 100 response rates between 67% and 89% [14].

Because of this extensive range of options, several international consensus guidelines support a personalized approach to care [30,31,32,33,34,35,36], accounting for disease phenotype, treatment history, comorbidities (e.g., IBD, demyelinating disease, drug characteristics (e.g., administration route, frequency), and lifestyle factors (e.g., family planning) [30,37,38,39,40,41,42]. For instance, genomic data, particularly the HLA*C60:02 status, may also guide treatment selection [43]; HLA*C60:02-negative patients tend to respond better to anti-TNF-α than anti-IL12/23 agents [43].

Furthermore, the availability of administration routes that do not require the assistance of specialized healthcare personnel, such as subcutaneous formulations or oral options, may offer a practical advantage for simplifying clinical management and improving patient convenience [44].

Real-world evidence (RWE) from immune-mediated diseases, including inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), Spondyloarthritis (SpA), Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), and chronic plaque psoriasis (PsO), supports the clinical utility of SC infliximab, showing high treatment persistence, stable disease control, and favorable safety profiles in routine practice, together with improvements in convenience and patient experience [45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. Notably, these effects are likely attributable to the stable pharmacokinetic profile of the subcutaneous formulation, characterized by high Ctrough values and reduced immunogenicity [53]. These data reinforce the rationale for evaluating an IV-to-SC transition in plaque psoriasis, where comparable benefits, particularly around convenience and adherence, may be clinically meaningful.

Building on this rationale, the present study reports real-world outcomes on switching to and maintaining SC infliximab monotherapy in patients with plaque psoriasis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

Data were collected between December 2023 and January 2024 and entered in an ad hoc database containing anonymized clinical and personal data. Anonymization was ensured through the immediate generation of an encrypted code, guaranteeing patient confidentiality.

2.2. Clinical Condition, Comorbidities, and Data Recovery

Data from 11 patients were entered into our database for statistical analysis. All patients had moderate to severe plaque psoriasis vulgaris. The patient group for these analyses consisted of 6 females and 5 males. The mean age was 45.5 ± 18.2 years. The diagnosis of plaque psoriasis was made at a specialized dermatology center. All patients were referred for systemic treatment, and each patient received intravenous IFX prior to transitioning to subcutaneous IFX administration. No other treatments, either concurrent or alternative, were administered. Only one patient (ID 4) in this case series presented with comorbid psoriatic arthritis.

2.3. Treatment

All patients had previously failed one or more courses of traditional systemic therapies (e.g., retinoids, cyclosporine, methotrexate) and subsequently began therapy with intravenous IFX at a dose of 5 mg/kg, with a mean treatment duration of 20 months (range: 9–38 months). According to the product information, transition to SC IFX therapy can begin from the sixth week of therapy, following two intravenous IFX infusions—one at initiation and one after two weeks. In this case series, all patients received intravenous IFX administered by trained personnel. Thereafter, SC-IFX was self-administered by the patients themselves, as reported in the literature [54]. All patients transitioned to SC-IFX after a mean of 20–27 months of intravenous IFX and continued SC therapy for 12 months.

2.4. TSQM-9 Questionnaire

Patient satisfaction with their pharmacological treatment was assessed using the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire Medication-9 (TSQM-9). The questionnaire consists of 9 questions covering various aspects of treatment and offers single-choice, multiple-option answers on Likert scales (only one answer is selectable). Seven of the nine questions use a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (bad) to 7 (good), while two questions (Q7 and Q8) use a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (bad) to 5 (good). Lower scores correspond to worse impressions, while higher scores are associated with better impressions. The total score of the questionnaire ranges from 9 (minimum) to 59 (maximum) points. A total score of 50 points indicates a high level of patient satisfaction (HLS). However, based on procedures reported in the scientific literature, TSQM-9 results are expressed as percentages (0–100%) to allow for data normalization [55]. Patient-reported scores were normalized by expressing the maximum questionnaire score (59 points) as 100%. Indeed, TSQM-9 values ≥50 points (84.75%) were selected as the threshold for HLS. TSQM-9 data were collected at the end of IV-IFX treatment and after 12 months of SC-IFX treatment.

2.5. PASI, DLQI, and PGAs

The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI), Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and Physician Global Assessment (PGA) scores were assessed before and after SC-IFX treatment. The PASI (0–72), DLQI (0–30) and the PGA (0, clear; 1, almost clear; 2, mild; 3, moderate; and 4, severe; Table 1) scores recorded by the patient were assessed by the attending physician at SC-IFX treatment initiation and 48 weeks after SC-IFX treatment [56].

Table 1.

Physician Global Assessment (PGA) [57].

2.6. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad 8.0 version (PRISM, San Diego, CA, USA). The Shapiro–Wilk test was applied to determine whether the data were parametrically distributed. Both W- and p-values were calculated. Student’s t-Test (parametric and paired) was used to compare TSQM-9 after IV-IFX (0 weeks) and SC-IFX (48 weeks) visits. Student’s t-Test was used to compare TSQM-9 scores, their normalized values (expressed as percentages), and delta variations between both treatments relative to the HLS reference point. In addition, ANOVA was used to compare TSQM scores between IV and SC–IFX treatments. All results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and number of items (N). For all quantitative analyses, statistical significance was defined as a p-value less than 0.05 (p < 0.05, *: p < 0.01, **; p < 0.001, ***; and p < 0.0001, ****).

3. Results

3.1. Follow-Up and Treatments

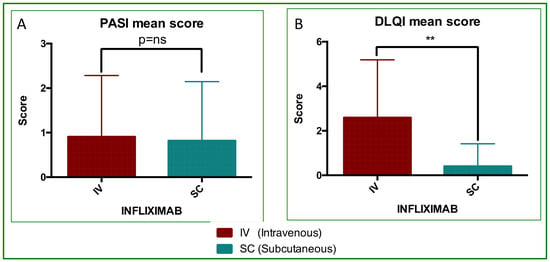

All patients demonstrated full treatment compliance with SC-IFX self-injections, and all completed at least 12 months of follow-up. The mean total treatment time (TTT; IV + SC) was 32.4 months (22 ÷ 50 months). Both PASI (Figure 1A) and DLQI (Figure 1B) improved at follow-up: the mean PASI decreased by approximately 10% after SC treatment, and DLQI improved in 100% of patients. PASI was better in 3/11 (27.3%), stable in 6/11 (54.5%), and worse in 2/11 (18.2%). Therefore, a total of 81.8% of patients did not show any worsening in their PASI scores. Notably, the two patients with worsening had low absolute PASI scores (2 and 4, respectively; Table 1). No adverse events were reported (Table 2).

Figure 1.

PASI and DLQI analyses. Mean score value and statistical analyses performed by paired Student’s and Wilcoxon tests. (A) PASI, differences were not significantly different; p = ns. (B) DLQI, differences were significantly different (p = 0.0041, **).

Table 2.

PASI and DLQI scores reported for IV-IFX and SC-IFX treatment.

3.2. TSQM Analyses

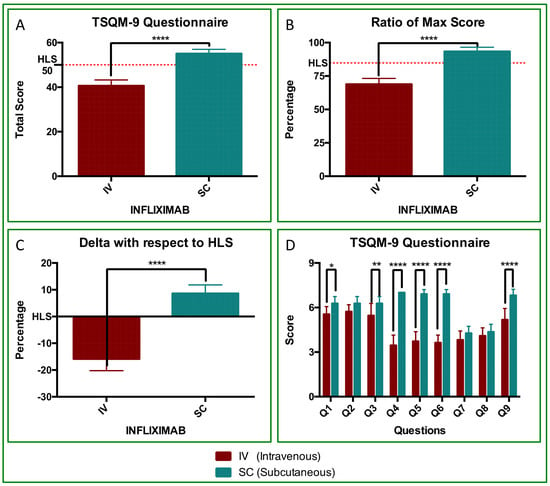

The TSQM-9 revealed a highly significant difference between IV-IFX and SC-IFX (Figure 2). Mean TSQM scores were 40.6 ± 0.8 for IV-IFX and 55.1 ± 0.6 for SC-IFX (p < 0.0001; Figure 2A). Scores were normalized to 0–100% to align with the existing literature, as detailed in the Section 2. The resulting percent TSQM values were 68.9 ± 4.4 in IV and 93.4 ± 3.2 in SC, respectively (p < 0.0001; Figure 1B). With respect to the HLS threshold, the deltas were −15.9% ± 4.4 for IV-IFX and 8.6% ± 3.2 for SC-IFX with a mean between-treatment difference of 24.5% (p < 0.0001; Figure 2C). Considering all items (Q1-Q9), the ANOVA results indicate significant effects of treatment (IV vs. SC; p < 0.0001) and differences in item scores (p < 0.0001). Sidak post hoc testing identified significant differences in 6 of 9 items: Q1 (p < 0.05), Q3 (p < 0.01), Q4 (p < 0.0001), Q5 (p < 0.0001), Q6 (p < 0.0001), and Q9 (p < 0.0001). Notably, Q4 to Q6, which assess treatment management/convenience, favored SC-IFX treatment, with mean differences of 3.545, 3.182, and 3.273 for Q4, Q5, and Q6, respectively (p < 0.0001; Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Treatment satisfaction (TSQM-9) with IV-IFX vs. SC-IFX. (A) TSQM-9 total score (0–59). The dotted line marks the HLS threshold (50/59 points). (B) Normalized TSQM-9 values (%), with a maximum of 100% (59 points). The dotted line marks the HLS threshold (84.75%). Differences were statistically significant (p < 0.0001, ****). All SC patients scored above 50 points. (C) Delta variation from the HLS threshold, showing negative values for IV-IFX and positive values for SC-IFX (p < 0.0001). (D) TSQM-9 Questionnaire (Q1–Q9 comparison). ANOVA with Sidak’s post hoc test showed statistically significant treatment effects and differences in mean item scores (p < 0.0001). Differences were highly significant for Q1 (p < 0.05, *), Q3 (p < 0.01, **), Q4 to Q6 (p < 0.0001,****), and Q9 (p < 0.0001, ****).

3.3. PGA

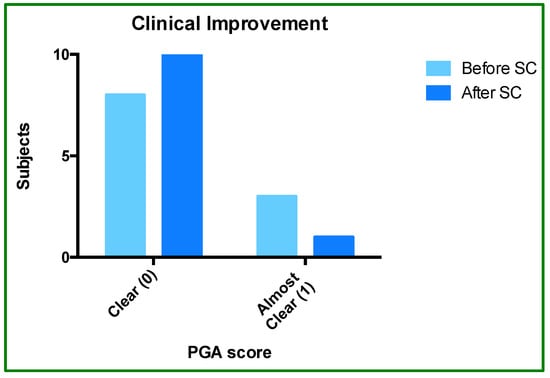

PGA score analysis showed an improvement, indicating an added benefit of SC-IFX. The proportion of patients who rated clear (score 0) versus almost clear (score 1) was 8:3 during IV treatment and 10:1 after SC treatment. This pattern reflects an interesting trend: SC-IFX did not worsen treatment clinical status and was rather associated with improvement in 18.2% of subjects (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Physician Global Assessment (PGA) before and after SC-IFX initiation. The bar graph shows the proportion of patients rated as “clear” (score of 0) or “almost clear” (score of 1) before and after switching to SC-IFX.

3.4. Adverse Events (AEs)

Treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs), defined as any untoward medical occurrence from the first administration of SC IFX to the end of follow-up, were recorded. In line with safety data for intravenous infliximab, particular attention was paid to infusion/injection-site reactions, infections, hypersensitivity reactions, and other treatment-related systemic events. In this case series, no adverse reactions were observed in any patient after switching.

4. Discussion

Inhibitors targeting TNF-α, IL-17, and IL-23 are widely used in clinical practice for the maintenance treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis [4,14,20,29,54,56]. The present study demonstrated the efficacy and safety of subcutaneous infliximab (SC-IFX) following long-term intravenous infliximab (IV-IFX) treatment. Over a mean follow-up of 32.4 months (Table 1), SC-IFX was well tolerated and associated with maintained or improved clinical and patient-reported outcomes compared with prior IV-IFX exposure.

After switching, the mean PASI and DLQI values were 0.82 and 0.00, respectively (Table 1 and Figure 1). This is consistent with the literature thresholds in which successful treatment corresponds to near-zero PASI and DLQI scores [51]. The change in PASI after the switch was not statistically significant, which was expected given the already very low switch PASI values. This indicates that SC treatment effectively maintained clinical remission. In contrast, DLQI showed a significant additional improvement (p = 0.0041; Figure 1), reflecting further gains in patient-reported quality of life after the switch.

To contextualize our TSQM-9 findings, we compared our satisfaction scores with those reported in another real-world psoriasis cohort using the same questionnaire, rather than to directly compare different therapies. In our study, patient satisfaction assessed with the TSQM-9 questionnaire was high, with an overall satisfaction score of 93%. For reference, the ProLOGUE study—an open-label, multicenter, real-world randomized study in Japanese adults with plaque psoriasis treated with the IL-17RA inhibitor brodalumab via subcutaneous injection—reported a TSQM-9 satisfaction score of 83% [55].

Furthermore, in our study, the TSQM-9 results also surpassed the high-level satisfaction (HLS) threshold, both in absolute score (50/59 points) and percentage (84.74%). ANOVA analysis showed that items Q4, Q5, and Q6, which reflect “treatment management/convenience” from the patient’s point of view [56], were 3-points higher on average with SC-IFX than those registered for IV-IFX (p < 0.001; Figure 2D). This improvement, although numerically modest, represents a statistically and clinically meaningful enhancement in patients’ day-to-day treatment experience and exceeded the outcomes reported in the ProLOGUE trial [55].

Finally, PGA analyses showed a trend favoring SC-IFX, suggesting that route switching did not hinder the physician-assessed outcomes (Figure 2). These findings are consistent with real-world evidence (RWE) from other chronic immune-mediated diseases, such as inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs, psoriatic arthritis (PsA), Spondyloarthritis (SpA), Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA), and chronic plaque psoriasis (PsO) [48,49,50,51,52,54,55,56]. In these instances, SC-IFX has been associated with high long-term treatment persistence, improved patient convenience and quality of life, lower immunogenicity, and improved cost-effectiveness. Although we did not perform pharmacokinetic or immunogenicity assessments in our cohort, phase I–III bridging studies comparing SC-IFX with its intravenous formulation have shown higher and more stable trough serum concentrations with SC administration, while maintaining comparable efficacy, safety, and overall rates of anti-drug antibodies [58,59,60]. This pattern has been interpreted as compatible with a high-zone tolerance mechanism, whereby sustained higher drug exposure does not increase, and may attenuate, clinically relevant immunogenic responses [53]. This pharmacokinetic and immunogenicity profile provides a mechanistic rationale for our observation that switching from IV to SC infliximab maintained clinical remission in patients with psoriasis.

Intriguingly, the recent REWATCH study provides reassuring data that earlier switching from IV- to SC-IFX does not compromise efficacy and safety in IBD patients [46]. Further evidence is needed to explore this hypothesis in the context of other chronic immune-mediated diseases. This case series provides proof of principles for the feasibility and safety of switching psoriasis patients from IV-IFX to SC-IFX. However, given the limited sample size and retrospective design, these results should be interpreted with caution, and larger comparative studies will be needed to confirm our findings. Despite these limitations, the data show high long-term treatment persistence, aligning with other real-world evidence across chronic immune-mediated diseases [46], reinforcing the potential of SC-IFX formulation to increase patient satisfaction and improve overall disease management.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, switching from intravenous to subcutaneous infliximab treatment was associated with reductions in DLQI and PGA scores, while maintaining similar PASI scores, in patients with plaque psoriasis. TSQM-9 scores revealed a greater treatment satisfaction with SC-IFX, particularly regarding convenience and daily treatment management. The results suggest that switching to subcutaneous IFX therapy did not worsen clinical assessment scores or raise safety concerns, supporting SC-IFX as a valid and apparently safe maintenance option after prior exposure to IV-IFX. Despite the modest sample size (n = 11) and the need for further comparative studies to validate these findings, these data underscore the potential of subcutaneous IFX to optimize long-term disease management in patients with plaque psoriasis previously treated with intravenous IFX.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.R. and L.Z.; methodology, D.R.; software, G.L.; validation, D.R., G.L. and M.F.; formal analysis, D.R.; investigation, G.L.; resources, M.F.; data curation, M.F. and L.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, D.R.; writing—review and editing, L.Z.; visualization, G.L.; supervision, L.Z.; project administration, L.Z.; funding acquisition, D.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Medical writing, graphical and editorial assistance and language editing were unconditionally funded by Celltrion Healthcare Italy S.r.l.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study. The data used for the analyses were anonymized; therefore, identifying the subjects, even using subsequent operations at the informatics level, is not possible. This aspect is regulated by law no. 675/1996 of the Guarantor of Privacy in Italy, in compliance with the use of personal data for scientific purposes. According to Italian national regulations (Ministerial Decree of 17 December 2004, and AIFA Guidelines for Observational Studies, 20 March 2008), as well as the European Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (GDPR) regarding data protection, and international ethical standards (Declaration of Helsinki, WMA 2013, art. 37), retrospective studies that do not involve identifiable data and do not alter the patient’s diagnostic–therapeutic path do not require prior approval by an ethics committee, provided that patient privacy and confidentiality are protected.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- WHO. Global Report on Psoriasis. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/global-report-on-psoriasis (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Raharja, A.; Mahil, S.K.; Barker, J.N. Psoriasis: A Brief Overview. Clin. Med. 2021, 21, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parisi, R.; Iskandar, I.Y.K.; Kontopantelis, E.; Augustin, M.; Griffiths, C.E.M.; Ashcroft, D.M. National, Regional, and Worldwide Epidemiology of Psoriasis: Systematic Analysis and Modelling Study. BMJ 2020, 369, m1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrowietz, U.; Lauffer, F.; Sondermann, W.; Gerdes, S.; Sewerin, P. Psoriasis as a Systemic Disease. Dtsch. Ärztebl. Int. 2024, 121, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, A.W.; Read, C. Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation, and Treatment of Psoriasis: A Review. JAMA 2020, 323, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieminska, I.; Pieniawska, M.; Grzywa, T.M. The Immunology of Psoriasis—Current Concepts in Pathogenesis. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2024, 66, 164–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greb, J.E.; Goldminz, A.M.; Elder, J.T.; Lebwohl, M.G.; Gladman, D.D.; Wu, J.J.; Mehta, N.N.; Finlay, A.Y.; Gottlieb, A.B. Psoriasis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2016, 2, 16082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshita, J.; Grewal, S.; Langan, S.M.; Mehta, N.N.; Ogdie, A.; Van Voorhees, A.S.; Gelfand, J.M. Psoriasis and Comorbid Diseases. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 76, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsmond, A.; Bereza-Malcolm, L.; Lynch, T.; March, L.; Xue, M. Skin Barrier Dysregulation in Psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.J.; Kavanaugh, A.; Lebwohl, M.G.; Gniadecki, R.; Merola, J.F. Psoriasis and Metabolic Syndrome: Implications for the Management and Treatment of Psoriasis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, R.G.; Cano, A.; Ortiz, A.; Espina, M.; Prat, J.; Muñoz, M.; Severino, P.; Souto, E.B.; García, M.L.; Pujol, M.; et al. Psoriasis: From Pathogenesis to Pharmacological and Nano-Technological-Based Therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuyama, M.; Mabuchi, T. New Treatment Addressing the Pathogenesis of Psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komiya, E.; Tominaga, M.; Kamata, Y.; Suga, Y.; Takamori, K. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Itch in Psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhang, H.; Lin, W.; Lu, L.; Su, J.; Chen, X. Signaling Pathways and Targeted Therapies for Psoriasis. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rendon, A.; Schäkel, K. Psoriasis Pathogenesis and Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arakawa, A.; Siewert, K.; Stöhr, J.; Besgen, P.; Kim, S.-M.; Rühl, G.; Nickel, J.; Vollmer, S.; Thomas, P.; Krebs, S.; et al. Melanocyte Antigen Triggers Autoimmunity in Human Psoriasis. J. Exp. Med. 2015, 212, 2203–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganguly, D.; Chamilos, G.; Lande, R.; Gregorio, J.; Meller, S.; Facchinetti, V.; Homey, B.; Barrat, F.J.; Zal, T.; Gilliet, M. Self-RNA–Antimicrobial Peptide Complexes Activate Human Dendritic Cells through TLR7 and TLR8. J. Exp. Med. 2009, 206, 1983–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, A.S.; Cohen, J.; Fei, J.; Zaba, L.C.; Cardinale, I.; Toyoko, K.; Ott, J.; Krueger, J.G. Insights into Gene Modulation by Therapeutic TNF and IFNγ Antibodies: TNF Regulates IFNγ Production by T Cells and TNF-Regulated Genes Linked to Psoriasis Transcriptome. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2008, 128, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowes, M.A.; Chamian, F.; Abello, M.V.; Fuentes-Duculan, J.; Lin, S.-L.; Nussbaum, R.; Novitskaya, I.; Carbonaro, H.; Cardinale, I.; Kikuchi, T.; et al. Increase in TNF-α and Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase-Expressing Dendritic Cells in Psoriasis and Reduction with Efalizumab (Anti-CD11a). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 19057–19062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, N.N.; Teague, H.L.; Swindell, W.R.; Baumer, Y.; Ward, N.L.; Xing, X.; Baugous, B.; Johnston, A.; Joshi, A.A.; Silverman, J.; et al. IFN-γ and TNF-α Synergism May Provide a Link between Psoriasis and Inflammatory Atherogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiricozzi, A.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Suárez-Fariñas, M.; Nograles, K.E.; Tian, S.; Cardinale, I.; Chimenti, S.; Krueger, J.G. Integrative Responses to IL-17 and TNF-α in Human Keratinocytes Account for Key Inflammatory Pathogenic Circuits in Psoriasis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2011, 131, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, C.E.M.; Strober, B.E.; Van De Kerkhof, P.; Ho, V.; Fidelus-Gort, R.; Yeilding, N.; Guzzo, C.; Xia, Y.; Zhou, B.; Li, S.; et al. Comparison of Ustekinumab and Etanercept for Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langley, R.G.; Elewski, B.E.; Lebwohl, M.; Reich, K.; Griffiths, C.E.M.; Papp, K.; Puig, L.; Nakagawa, H.; Spelman, L.; Sigurgeirsson, B.; et al. Secukinumab in Plaque Psoriasis—Results of Two Phase 3 Trials. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cargill, M.; Schrodi, S.J.; Chang, M.; Garcia, V.E.; Brandon, R.; Callis, K.P.; Matsunami, N.; Ardlie, K.G.; Civello, D.; Catanese, J.J.; et al. A Large-Scale Genetic Association Study Confirms IL12B and Leads to the Identification of IL23R as Psoriasis-Risk Genes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 80, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reich, K.; Nestle, F.O.; Papp, K.; Ortonne, J.-P.; Evans, R.; Guzzo, C.; Li, S.; Dooley, L.T.; Griffiths, C.E.M. EXPRESS study investigators Infliximab Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis: A Phase III, Multicentre, Double-Blind Trial. Lancet 2005, 366, 1367–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, C.L.; Powers, J.L.; Matheson, R.T.; Goffe, B.S.; Zitnik, R.; Wang, A.; Gottlieb, A.B. Etanercept Psoriasis Study Group Etanercept as Monotherapy in Patients with Psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 2014–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, C.L.; Kimball, A.B.; Papp, K.A.; Yeilding, N.; Guzzo, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Dooley, L.T.; Gordon, K.B.; PHOENIX 1 Study Investigators. Efficacy and Safety of Ustekinumab, a Human Interleukin-12/23 Monoclonal Antibody, in Patients with Psoriasis: 76-Week Results from a Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial (PHOENIX 1). Lancet 2008, 371, 1665–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, K.; Armstrong, A.W.; Langley, R.G.; Flavin, S.; Randazzo, B.; Li, S.; Hsu, M.-C.; Branigan, P.; Blauvelt, A. Guselkumab versus Secukinumab for the Treatment of Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis (ECLIPSE): Results from a Phase 3, Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, K.B.; Blauvelt, A.; Papp, K.A.; Langley, R.G.; Luger, T.; Ohtsuki, M.; Reich, K.; Amato, D.; Ball, S.G.; Braun, D.K.; et al. Phase 3 Trials of Ixekizumab in Moderate-to-Severe Plaque Psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatore, F.; Villani, A.-P.; Tauber, M.; Viguier, M.; Guillot, B.; The Psoriasis Research Group of the French Society of Dermatology (Groupe de Recherche sur le Psoriasis de la Société Française de Dermatologie). French Guidelines on the Use of Systemic Treatments for Moderate-to-severe Psoriasis in Adults. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, 464–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskins, M.; Dressler, C.; Werner, R.N.; Nast, A. Methods Report: Update of the German S3 Guideline for the Treatment of Psoriasis Vulgaris. JDDG J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2018, 16, ddg.13471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisondi, P.; Fargnoli, M.C.; Amerio, P.; Argenziano, G.; Bardazzi, F.; Bianchi, L.; Chiricozzi, A.; Conti, A.; Corazza, M.; Costanzo, A.; et al. Italian Adaptation of EuroGuiDerm Guideline on the Systemic Treatment of Chronic Plaque Psoriasis. Ital. J. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 157, 1–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nast, A.; Smith, C.; Spuls, P.I.; Avila Valle, G.; Bata-Csörgö, Z.; Boonen, H.; De Jong, E.; Garcia-Doval, I.; Gisondi, P.; Kaur-Knudsen, D.; et al. EuroGuiDerm Guideline on the Systemic Treatment of Psoriasis Vulgaris—Part 1: Treatment and Monitoring Recommendations. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 2461–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nast, A.; Smith, C.; Spuls, P.I.; Avila Valle, G.; Bata-Csörgö, Z.; Boonen, H.; De Jong, E.; Garcia-Doval, I.; Gisondi, P.; Kaur-Knudsen, D.; et al. EuroGuiDerm Guideline on the Systemic Treatment of Psoriasis Vulgaris—Part 2: Specific Clinical and Comorbid Situations. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, 281–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oon, H.H.; Tan, C.; Aw, D.C.W.; Chong, W.-S.; Koh, H.Y.; Leung, Y.-Y.; Lim, K.S.; Pan, J.Y.; Tan, E.S.-T.; Tan, K.W.; et al. 2023 Guidelines on the Management of Psoriasis by the Dermatological Society of Singapore. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2024, 53, 562–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.A.; Guyatt, G.; Ogdie, A.; Gladman, D.D.; Deal, C.; Deodhar, A.; Dubreuil, M.; Dunham, J.; Husni, M.E.; Kenny, S.; et al. 2018 American College of Rheumatology/National Psoriasis Foundation Guideline for the Treatment of Psoriatic Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2019, 71, 2–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiricozzi, A.; Pimpinelli, N.; Ricceri, F.; Bagnoni, G.; Bartoli, L.; Bellini, M.; Brandini, L.; Caproni, M.; Castelli, A.; Fimiani, M.; et al. Treatment of Psoriasis with Topical Agents: Recommendations from a Tuscany Consensus. Dermatol. Ther. 2017, 30, e12549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaio, M.; Vastarella, M.G.; Sullo, M.G.; Scavone, C.; Riccardi, C.; Campitiello, M.R.; Sportiello, L.; Rafaniello, C. Pregnancy Recommendations Solely Based on Preclinical Evidence Should Be Integrated with Real-World Evidence: A Disproportionality Analysis of Certolizumab and Other TNF-Alpha Inhibitors Used in Pregnant Patients with Psoriasis. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamrawi, R.I.; Ghiam, N.; Wu, J.J. Comparison of Psoriasis Guidelines for Use of IL-23 Inhibitors in the United States and United Kingdom: A Critical Appraisal and Comprehensive Review. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2022, 33, 1252–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauregui, W.; Abarca, Y.A.; Ahmadi, Y.; Menon, V.B.; Zumárraga, D.A.; Rojas Gomez, M.C.; Basri, A.; Madala, R.S.; Girgis, P.; Nazir, Z. Shared Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Psoriasis: Unraveling the Connection. Cureus 2024, 16, e68569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.D.; Jo, H.; Cho, H.; Jang, W.; Park, J.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.; Lee, K.; Oh, J.; Wen, X.; et al. Biologics Use for Psoriasis during Pregnancy and Its Related Adverse Outcomes in Pregnant Women and Newborns: Findings from WHO Pharmacovigilance Study. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2025, 186, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, R.H.A.; Essam, M.; Anwar, I.; Shehab, H.; Komy, M.E. Psoriasis Paradox—Infliximab-Induced Psoriasis in a Patient with Crohn’s Disease: A Case Report and Mini-Review. J. Int. Med. Res. 2023, 51, 03000605231200270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dand, N.; Duckworth, M.; Baudry, D.; Russell, A.; Curtis, C.J.; Lee, S.H.; Evans, I.; Mason, K.J.; Alsharqi, A.; Becher, G.; et al. HLA-C*06:02 Genotype Is a Predictive Biomarker of Biologic Treatment Response in Psoriasis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 143, 2120–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morita, A.; Nishikawa, K.; Yamada, F.; Yamanaka, K.; Nakajima, H.; Ohtsuki, M. Safety, Efficacy, and Drug Survival of the Infliximab Biosimilar CT-P13 in Post-marketing Surveillance of Japanese Patients with Psoriasis. J. Dermatol. 2022, 49, 957–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baraliakos, X.; Tsiami, S.; Vijayan, S.; Jung, H.; Barkham, N. Real-world Evidence for Subcutaneous Infliximab (CT-P13 SC) Treatment in Patients with Psoriatic Arthritis during the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic: A Case Series. Clin. Case Rep. 2022, 10, e05205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertani, L.; Ribaldone, D.G.; Bossa, F.; Guerra, M.; Annese, M.; Manta, R.; Armandi, A.; Caviglia, G.P.; Todeschini, A.; Variola, A. When to Switch to Subcutaneous Infliximab? The RE-WATCH Multicenter Study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2025, 31, 3363–3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buisson, A.; Nachury, M.; Bazoge, M.; Yzet, C.; Wils, P.; Dodel, M.; Coban, D.; Pereira, B.; Fumery, M. Long-term Effectiveness and Acceptability of Switching from Intravenous to Subcutaneous Infliximab in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease Treated with Intensified Doses: The REMSWITCH-LT Study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 59, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buisson, A.; Nachury, M.; Reymond, M.; Yzet, C.; Wils, P.; Payen, L.; Laugie, M.; Manlay, L.; Mathieu, N.; Pereira, B.; et al. Effectiveness of Switching From Intravenous to Subcutaneous Infliximab in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: The REMSWITCH Study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 21, 2338–2346.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.N.; Hye Song, J.; Jin Kim, S.; Ha Park, Y.; Wan Choi, C.; Eun Kim, J.; Ran Kim, E.; Kyung Chang, D.; Kim, Y.-H. One-Year Clinical Outcomes of Subcutaneous Infliximab Maintenance Therapy Compared with Intravenous Infliximab Maintenance Therapy in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Prospective Cohort Study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2024, 30, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, A. Safety and Efficacy of Transitioning Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients from Intravenous to Subcutaneous Infliximab: A Single-Center Real-World Experience. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2023, 36, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.J.; Critchley, L.; Storey, D.; Gregg, B.; Stenson, J.; Kneebone, A.; Rimmer, T.; Burke, S.; Hussain, S.; Yi Teoh, W.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Elective Switching from Intravenous to Subcutaneous Infliximab [CT-P13]: A Multicentre Cohort Study. J. Crohns Colitis 2022, 16, 1436–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viazis, N.; Karamanakos, A.; Mousourakis, K.; Christidou, A.; Fousekis, F.; Mpakogiannis, K.; Koukoudis, A.; Katsanos, K.; Christodoulou, D.; Cheila, M.; et al. Switching from Intravenous to Subcutaneous Infliximab in Patients with Immune Mediated Diseases in Clinical Remission. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1583401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Alten, R.; Cummings, F.; Danese, S.; D’Haens, G.; Emery, P.; Ghosh, S.; Gilletta De Saint Joseph, C.; Lee, J.; Lindsay, J.O.; et al. Innovative Approaches to Biologic Development on the Trail of CT-P13: Biosimilars, Value-Added Medicines, and Biobetters. mAbs 2021, 13, 1868078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditto, M.C.; Parisi, S.; Cotugno, V.; Barila, D.A.; Sardo, L.L.; Cattel, F.; Fusaro, E. Subcutaneous Infliximab CT-P13 without Intravenous Induction in Psoriatic Arthritis: A Case Report and Pharmacokinetic Considerations. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 62, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imafuku, S.; Ohata, C.; Okubo, Y.; Tobita, R.; Saeki, H.; Mabuchi, T.; Hashimoto, Y.; Murotani, K.; Kitabayashi, H.; Kanai, Y. Effectiveness of Brodalumab in Achieving Treatment Satisfaction for Patients with Plaque Psoriasis: The ProLOGUE Study. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2022, 105, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharmal, M.; Payne, K.; Atkinson, M.J.; Desrosiers, M.-P.; Morisky, D.E.; Gemmen, E. Validation of an Abbreviated Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM-9) among Patients on Antihypertensive Medications. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2009, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, C.; Langley, R.G.; Papp, K.; Tyring, S.K.; Wasel, N.; Vender, R.; Unnebrink, K.; Gupta, S.R.; Valdecantos, W.C.; Bagel, J. Adalimumab for treatment of moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis of the hands and feet: Efficacy and safety results from REACH, a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Arch. Dermatol. 2011, 147, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chetwood, J.D.; Arzivian, A.; Tran, Y.; Paramsothy, S.; Leong, R.W. Meta-Analysis: Intravenous Versus Subcutaneous Infliximab in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 62, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, S.; Ben-Horin, S.; Leszczyszyn, J.; Dudkowiak, R.; Lahat, A.; Gawdis-Wojnarska, B.; Pukitis, A.; Horynski, M.; Farkas, K.; Kierkus, J.; et al. Randomized Controlled Trial: Subcutaneous vs. Intravenous Infliximab CT-P13 Maintenance in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 2340–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, S.; Colombel, J.-F.; Hanauer, S.B.; Sandborn, W.J.; Danese, S.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, S.H.; Bae, Y.J.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, S.G.; et al. Comparing Outcomes With Subcutaneous Infliximab (CT-P13 SC) by Baseline Immunosuppressant Use: A Post Hoc Analysis of the LIBERTY-CD and LIBERTY-UC Studies. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2025, 31, 2714–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).