Abstract

Background: This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to assess the burden of carotid atherosclerosis, including the prevalence of carotid plaques and stenosis, among individuals with familial hypercholesterolemia (FH). Methods: PubMed, Embase, and Scopus were searched up to 3 August 2025 to identify full-text, peer-reviewed articles published in English reporting the prevalence of carotid atherosclerotic plaques and/or stenosis in adult (≥18 years) patients with either a clinical or genetic diagnosis of FH. The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. Results were synthesized using random-effects meta-analysis and presented as pooled prevalence estimates with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) displayed in forest plots. Publication bias was assessed using the Doi plot and the Luis Furuya-Kanamori index. Results: For the analysis of carotid plaque prevalence, seventeen studies including a total of 2870 patients were included (weighted age 47.2 ± 13.4 years, 47.3% male). No statistical difference in the pooled prevalence of carotid plaques was observed between clinically and genetically diagnosed FH (both 53%; 95% CI: 40–65%), however sub-analyses suggested a higher plaque burden in genetic FH. For the analysis of carotid stenosis prevalence, four studies comprising 704 participants were included; however, the available data were less consistent, yielding a pooled prevalence of 9% (95% CI: 0–40%). In conclusion, the results should be interpreted with caution due to several limitations, including the relatively low quality of the included studies, potential publication bias, considerable heterogeneity between the studies, and low to moderate certainty of evidence for the pooled estimates. These findings further emphasize the need for large-scale, standardized, multicenter studies to better characterize the burden of carotid atherosclerosis in this population.

1. Introduction

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), the most common genetic lipid disorder, is characterized by markedly elevated levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) since birth [1]. The more prevalent heterozygous form of FH affects approximately 1 in 300 individuals worldwide and is typically associated with naive LDL-C concentrations ranging from 190 to 400 mg/dL [2,3]. Homozygous FH, historically estimated at 1 case per million population, is observed to be more prevalent in recent studies, accounting for 1 case per 170,000 to 300,000 [4]. Homozygotes of FH may have plasma LDL-C levels that are at least twice as high as those of heterozygous FH and therefore several times higher than normal serum levels [5].

FH leads to a substantially increased risk of premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) [5,6]. In particular, FH stimulates progression of atherosclerotic lesions in coronary and lower limb artery territories [6,7,8]. Most studies assessing the cardiovascular burden in FH have focused on coronary artery disease (CAD), where the risk is estimated to be up to 13-fold higher than in the general population, affecting roughly one-third of patients with FH [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. It has been reported that 50% of men by the age of 50 years and up to 30% of women by the age of 60 years will experience myocardial infarction (MI) when heterozygous FH remains untreated [12]. Homozygous FH imposes extremely high risk of major adverse cardiac and cerebral events (MACCE) [14]. Fatal cardiovascular complications could develop even in the first decade of life [4]. The coronary threshold would be around 11 years old even for individuals with lower LDL-C levels [8]. Most patients would not survive beyond 30 years of age when left untreated [15].

Data on the prevalence of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) in FH are less consistent, with reported rates ranging from as low as 0.3% to as high as 60%, depending on the study population and diagnostic methods applied [16]. Nevertheless, FH has been associated with up to threefold increased risk of PAD compared to the general population [17]. Data for renal artery stenosis in FH are not available. Emanuelsson et al. reported odds ratios (ORs) for PAD in individuals with FH as: 1.84 (95% CI: 1.70–2.00) in those with possible FH and 1.36 (95% CI: 1.00- 1.84) in individuals with probable/definite FH, whereas respective ORs of having chronic kidney disease were 1.92 (95% CI, 1.78–2.07) and 2.42 (95% CI, 1.86–3.26) [18]. In line, compared with individuals with unlikely FH and Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI) above 0.9, the multivariable adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) of MI was 4.60 (95% CI, 2.36–8.97) in those with possible/probable/definite FH and ABI below 0.9 [18].

The only reliable method to confirm FH is genetic testing [19]. The most common genetic disorders altering the metabolism of LDL-C include mutations in the gene for LDL receptor (LDLR), and less commonly in those for apolipoprotein B (APOB), proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9 (PCSK9), and others [1,19,20].

Although, genetic testing remains the gold standard for confirming the diagnosis of FH [1,19,20], several algorithms for FH diagnosis were built to facilitate patient management [21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. These algorithms include not only the magnitude of the naive LDL-C levels, but also a personal and family history of premature ASCVD, and physical findings such as tendon xanthomas and arcus corneae. Various combinations of these clinical features are incorporated into diagnostic algorithms used to estimate the probability of FH [21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. Among these, the Dutch Lipid Clinic Network (DLCN) criteria are the most widely used and validated [23]. Other established diagnostic approaches include Simon Broome criteria, Welsh FH score, Make Early Diagnosis to Prevent Early Deaths (MEDPED), as well as variety of national guidelines, such as Japanese Atherosclerosis Society guidelines criteria or Canadian FH criteria [24,25,26,27].

By contrast, evidence regarding atherosclerotic involvement of the carotid arteries in FH remains limited [28]. In the general population, carotid atherosclerosis is observed in approximately 20% of individuals, while significant carotid artery stenosis (CAS) affects approximately 3% of adults over 45 years old, increasing prevalence to 10% in the elderly [29,30,31,32]. CAS resulting in a significant lumen reduction (>50%) is observed in between 10% and 20% cases of all ischemic strokes [30,31,32,33]. It is commonly believed that atherosclerosis develops in parallel manner in diverse arterial territories, including the aorta, coronary, supra-aortic, renal and lower limb arterial beds [34,35,36]. Furthermore, atherosclerosis burden in one arterial territory could predict atherosclerosis extent in another, as well as the risk of adverse cardiovascular events [37,38,39].

To date, the prevalence of carotid plaques and stenosis in patients with FH has not been systematically established, despite the fact that carotid plaque is a strong predictor of MACCE [28,40]. Taking into consideration that carotid intima-media and carotid plaques are commonly recognized as mirrors for atherosclerotic burden in other arterial territories, the lack of consistency in reports puts this hypothesis at risk in patients with FH [41,42,43,44].

Therefore, the aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to evaluate the carotid atherosclerosis burden in patients with either clinical or genetic FH in order to establish a potential connection between carotid and coronary atherosclerosis in patients with FH.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines [45]. The PRISMA 2020 checklist is enclosed in the Supplementary Material (Figure S1) [45].

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

We included peer-reviewed studies that reported the prevalence of carotid atherosclerotic plaques and/or stenosis in individuals with either a clinical or genetic diagnosis of FH. Eligible studies enrolled adult participants (≥18 years) diagnosed with FH and provided original data enabling the estimation of carotid plaques/stenosis frequency. Carotid atherosclerotic plaques were required to be assessed using ultrasonography and defined according to the Mannheim consensus criteria: (1) a focal structure encroaching into the arterial lumen by at least 0.5 mm, (2) a lesion protruding ≥50% beyond the surrounding intima–media thickness (IMT), or (3) a focal thickening >1.5 mm measured from the media–adventitia interface to the intima–lumen surface [46]. Studies applying any single criterion consistent with the Mannheim definition were also considered eligible. Carotid atherosclerotic stenosis had to be defined as ≥50% narrowing of the extracranial carotid artery (internal or common), with a specified method of detection, including ultrasonography, computed tomography angiography, magnetic resonance angiography or digital subtraction angiography [47]. In both research and clinical practice, ultrasound is a sufficient and preferred method for assessing the presence of carotid plaques; in contrast, the evaluation of carotid stenosis requires more precise quantification of the degree of narrowing, which explains the broader range of included imaging modalities. Diagnostic criteria for FH were required to be clearly defined, based on either genetic testing or established clinical algorithms, including the DLCN, Simon Broome Register, MEDPED, Japanese Atherosclerosis Society guidelines, Canadian FH criteria, or other established clinical criteria. Alternatively, diagnosis could be based on total cholesterol or LDL-C cutoffs, provided these were combined with additional clinical information, such as personal history of premature ASCVD, family history of hypercholesterolemia or premature ASCVD, and relevant physical findings (e.g., tendon xanthomas). Eligible studies had to provide sufficient data on number of FH individuals, and the number or percentage of individuals with carotid atherosclerotic plaques and/or stenosis. Exclusion criteria comprised case reports, case series with fewer than 10 participants, reviews, editorials, studies lacking sufficient data, and those focused exclusively on homozygous FH. Only full-text articles published in English were included.

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

A comprehensive search of PubMed (MEDLINE), Embase, and Scopus was conducted to 3 August 2025. The core search query applied across all databases was: (“familial hypercholesterolemia” OR “FH”) AND (“carotid atherosclerosis” OR “carotid plaque” OR “carotid stenosis”). In addition, database-specific controlled vocabulary was incorporated: for PubMed, “Hyperlipoproteinemia Type II” [Mesh] was used in the first part of the query and “Carotid Artery Diseases” [Mesh] in the second part; for Embase, the corresponding Emtree terms ‘familial hypercholesterolemia’/exp and ‘carotid artery disease’/exp were added. In Scopus, the search was restricted to titles and abstracts due to the high number of records initially retrieved (6244 records without restrictions). Reference lists of all eligible studies and relevant reviews were also screened to identify additional articles. No restrictions on language or publication date were applied.

2.3. Selection and Data Collection Processes

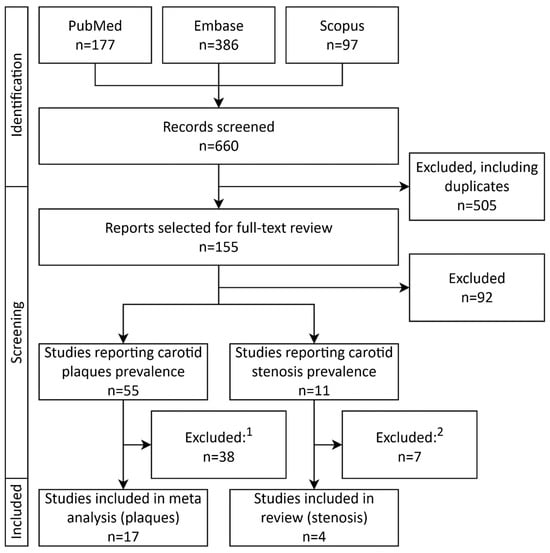

Titles and abstracts were screened, and the full texts of potentially eligible studies were subsequently assessed by MP. Given the heterogeneity of the included studies and the fact that carotid plaques/stenosis prevalence was often reported as part of population characteristics rather than as a primary study objective, methodological quality was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [48]. Studies were categorized into two quality groups based on the proportion of MMAT criteria met: high quality (≥80% of criteria fulfilled) and low quality (<80% of criteria fulfilled). Data extraction was performed by MP using a standardized form. Extracted data included study characteristics (author, year, country, DOI), details of carotid artery assessment (plaque definition, imaging modality used for carotid stenosis detection), and population characteristics (sample size, mean or median age, sex distribution, comorbidities including hypertension, diabetes and CAD, mean or median LDL-C concentration, and number of participants with carotid plaques/stenosis). The study selection flowchart is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA study selection flowchart depicting selection and inclusion process of studies. 1—Reasons for study exclusion after full-text review: lack of carotid plaque definition (n = 9); carotid plaque definition differing from the methodology adopted in this meta analysis (n = 7); conference abstract (n = 6); study population entirely or partly <18 years old (n = 4); overlapping study population with an included study (n = 3); full text in a non-English language (n = 2); full text not accessible (n = 2); multiple reasons (n = 5). 2—Reasons for study exclusion after full-text review: conference abstract (n = 3); full text available in a non-English language (n = 2); overlapping study population with an included study (n = 1); lack of information regarding carotid stenosis assessment (n = 1). Abbreviations: FH—familial hypercholesterolemia.

2.4. Data Items and Effect Measure

The primary outcomes were the prevalence of carotid atherosclerotic plaques and carotid stenosis in the adult FH population. Additional analyses evaluated plaque prevalence in studies based on a clinical diagnosis of FH (including those with a subset of genetically confirmed cases), in studies enrolling exclusively genetically confirmed FH individuals, and according to whether participants with established ASCVD were included. For each study, prevalence was defined as the proportion of FH participants presenting with carotid plaques or stenosis. The effect measure used for quantitative synthesis was the pooled prevalence with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Additional qualitative data were extracted as counts with percentages, whereas quantitative data were extracted as means with 95% CIs or as medians with the first and third quartiles (Q1–Q3) or interquartile ranges (IQR).

2.5. Synthesis Methods

Data were analyzed using R software (version 4.5.0) within the RStudio environment (version 2025.05.0+496). The quantitative and qualitative characteristics of participants in the included studies were summarized using weighted estimates. For studies reporting quantitative variables as median and interquartile range, the Box–Cox method was applied to approximate the corresponding mean and standard deviation. Pooled prevalence estimates were calculated using the inverse-variance method on the Freeman–Tukey double-arcsine transformed proportions. Between-study variance (τ2) was estimated using the Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) method, and confidence intervals for τ2/τ were calculated using the Q-Profile method. Heterogeneity was assessed with Cochran’s Q and I2 (based on Q). CI for the pooled estimates were computed using the Hartung–Knapp adjustment, and prediction intervals were calculated to estimate the expected range of prevalence in future studies. A 95% CI for individual study proportions was calculated using the Clopper–Pearson exact method. Predefined subgroup analyses were performed according to method of FH diagnosis and inclusion/exclusion of participants with established ASCVD. Publication bias was assessed through visual inspection of a Doi plot with the Luis Furuya-Kanamori (LFK) index. Results were presented as pooled prevalence with 95% confidence intervals and visualized using forest plots. Sensitivity analyses used a leave-one-out approach, excluding studies with extreme prevalence values to assess their impact on the pooled estimates. The overall certainty of the pooled prevalence estimates was qualitatively assessed using the GRADE approach, considering the methodological quality of the included studies, heterogeneity, and consistency of results across analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Carotid Plaques

3.1.1. Description of Included Studies

Seventeen international studies with total of 2870 patients enrolled were included in the final analysis, as shown in the PRISMA flowchart depicted in Figure 1. All studies were single-center, observational studies [28,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64]. Eleven studies were from Europe [28,50,51,53,55,56,59,60,61,62,64], and six from Central or East Asia [49,52,54,57,58,63]. All seventeen studies on FH reported the prevalence of carotid atherosclerotic plaques defined according to the Mannheim criteria [28,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64]. Eight studies fully applied the Mannheim criteria for plaque definition [28,49,52,53,54,57,60,61], while the remaining nine applied them only partially [50,51,55,56,58,59,62,63,64]. Among the included studies, seven enrolled only individuals without a prior diagnosis of ASCVD [49,51,55,56,59,61,62], whereas the remaining ten imposed no such restriction [28,50,52,53,54,57,58,60,63,64]. Five studies diagnosed FH using both DLCN criteria and genetic testing [49,53,54,57,59], with two of them additionally reporting data for genetically confirmed subgroups [53,54]. Four studies included only patients with genetically verified FH [51,52,56,62]. Two studies applied genetic testing in combination with the Simon Broome criteria [50,60], one used genetic testing or defined clinical criteria [28], one genetic testing or the van Aalst-Cohen criteria [61], and another genetic testing or either DLCN or Simon Broome criteria [55]. One study relied exclusively on DLCN [58], while two applied only defined clinical diagnostic criteria [63,64].

Overall, 14 of the 17 studies incorporated genetically confirmed FH cases to varying extents, with reported proportions ranging from 24.9% to 100%. Participant characteristics also varied. The mean or median age ranged from 37 to 56.9 years, with a weighted mean (WM) 47.2 ± 13.4 years. The proportion of men varied between 35.1% and 58.3%, with a weighted proportion (WP) of 47.3%. The prevalence of hypertension ranged from 8.3% to 66.7% (WP: 24.2%), diabetes mellitus from 0% to 15.3% (WP: 4.9%), and coronary artery disease from 0% to 66.9% (WP 13.4%). Reported mean or median LDL-C levels ranged from 127.6 to 363.5 mg/dL (WM: 216.0 ± 73.4 mg/dL).

Details regarding included studies and patient characteristics across individual studies are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies reporting carotid plaque.

3.1.2. Prevalence of Carotid Plaques in All Included Studies

The pooled prevalence of carotid atherosclerotic plaques among 2870 subjects with either clinical or genetic FH was 52% with 95% CI ranging from 40% to 65% (Figure 2). However, heterogeneity was considerable, yielding a wide prediction interval. In the subgroup analysis according to ASCVD status, studies including patients irrespective of ASCVD reported a pooled prevalence of 57% among 1944 individuals (95% CI: 40–73%), whereas in studies restricted to patients without previously established ASCVD, including 926 individuals, the prevalence was 46% (95% CI: 23–70%). In both subgroups, heterogeneity remained very high and the prediction intervals were non-conclusive (Figure S1).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of carotid plaque prevalence in all included studies. Abbreviations: CI—confidence interval.

3.1.3. Prevalence of Carotid Plaques in Studies with Clinical Diagnosis of FH (Including Those with a Subset of Genetically Confirmed Cases)

The analysis limited to studies based on a clinical diagnosis of FH, including those with a subset of genetically confirmed cases, encompassed 13 studies with a total of 2408 participants [28,49,50,53,54,55,57,58,59,60,61,63,64]. The proportion of genetically confirmed FH within these studies ranged from 0% (no genetic testing was performed) to 87.4%. The pooled prevalence of carotid plaques in this group was 53% (95% CI: 40–66%), (Figure 3). In studies restricted to participants without previously established ASCVD, the prevalence reached 55% (95% CI: 13–93%), whereas in studies without this restriction it was 53% (95% CI: 37–68%), (Figure S2).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of carotid plaque prevalence in studies with clinical diagnosis of FH (including those with a subset of genetically confirmed cases). Abbreviations: CI—confidence interval.

3.1.4. Prevalence of Carotid Plaques in Studies Including Only Genetically Confirmed FH

Among 706 individuals with genetically confirmed FH included in 6 studies [51,52,53,54,56,62], the pooled prevalence of carotid atherosclerotic plaques was 53% (95% CI: 17–88%), (Figure 4). When stratified by ASCVD status, studies enrolling patients regardless of ASCVD showed a prevalence of 73% across 305 participants (95% CI: 0–100%), while studies limited to ASCVD-free cohorts, comprising 401 participants, demonstrated a prevalence of 34% (95% CI: 0–85%), (Figure S3).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of carotid plaque prevalence in studies including only genetically confirmed FH. Abbreviations: CI—confidence interval.

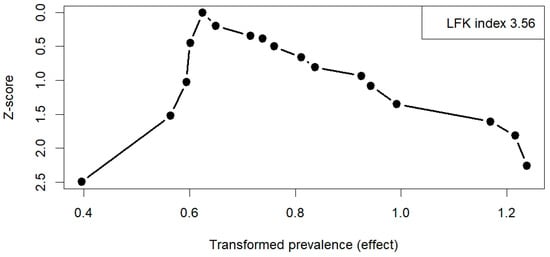

3.1.5. Publication Bias Assessment, Sensitivity Analysis, and Certainty of Evidence

Across all included studies, the Doi plot demonstrated marked asymmetry, with an LFK index of 3.56, indicating very high heterogeneity among the studies and a strong suggestion of potential publication bias (Figure 5). Similar results were obtained in the subgroup analyses, with an LFK index of 3.73 for studies based on a clinical diagnosis of FH and 2.9 for those including only genetically confirmed FH (Figure S4). Sensitivity analyses, excluding studies with extreme prevalence values, showed broadly similar pooled estimates, suggesting that the results were generally robust. The certainty of evidence for the pooled prevalence estimates of carotid plaques, including subgroup analyses, was rated as low to moderate.

Figure 5.

Doi plot of all included studies on carotid plaque prevalence. Abbreviations: LFK—Luis Furuya-Kanamori index.

3.2. Carotid Stenosis

3.2.1. Description of Included Studies

A total of four studies reporting the prevalence of carotid artery stenosis among patients with FH were included [65,66,67,68] (Table 2). Two were from Europe [66,67], and two from Japan [65,68]. In all studies, stenosis was assessed using ultrasonography [65,66,67,68]; however, only one study specified the use of the NASCET method [65], while the others did not report the method used to estimate the degree of narrowing [66,67,68]. The threshold defining stenosis varied between studies, ranging from 50% to 70%. Two studies included only patients with genetic FH [66,67], one study applied genetic testing in combination with the Japan Atherosclerosis Society guidelines [65], and one used defined clinical criteria [68].

Table 2.

Characteristics of the studies reporting carotid stenosis.

The mean age was reported only in one study [67]. The proportion of men was between 42.1% and 52.4%; the prevalence of hypertension was between 17.3% and 25.4%; diabetes mellitus was between 0% and 9.5%; and coronary artery disease between 26.8% and 100%.

Details of the studies and individuals included in the carotid stenosis prevalence analysis are presented in Table 2.

3.2.2. Prevalence of Carotid Stenosis

The reported prevalence of carotid artery stenosis varied substantially, ranging from 0.7–4.6% in studies with larger populations to 23.8–26.3% in studies with considerably smaller sample sizes. The pooled prevalence of carotid stenosis among 704 FH individuals in 4 studies was 9% (95% CI: 0–40%), (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Forest plot of carotid stenosis prevalence. Abbreviations: CI—confidence interval.

3.2.3. Publication Bias Assessment, Sensitivity Analysis, and Certainty of Evidence

The Doi plot shows significant asymmetry, with an LFK index of 4.32 (Figure S5). Sensitivity analyses demonstrated that pooled prevalence estimates varied appreciably with the exclusion of individual studies, highlighting instability of the summary effect. The certainty of evidence for the pooled estimate of carotid artery stenosis prevalence was rated as very low.

4. Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis provide the first comprehensive synthesis of the prevalence of carotid atherosclerosis burden among adults with FH. Our findings indicate a pooled prevalence of carotid plaques of 57% in a total of 2870 subjects, highlighting a substantial burden of carotid atherosclerosis in this high-risk population. Notably, prevalence was higher in studies including patients with established ASCVD compared to ASCVD-free cohorts (57% vs. 46%), suggesting that coexisting CAD or PAD significantly increases carotid plaque burden.

Similarly, the prevalence of carotid artery stenosis in individuals with FH appears highly variable across studies, ranging from less than 1% to over 25%. This heterogeneity likely reflects differences in study populations, diagnostic criteria, and stenosis thresholds, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions. Compared with the general population, where carotid stenosis is estimated to affect approximately 3% of adults, with a sporadic incidence under the age of 50 years [69], the available data may suggest that FH may confer an elevated risk, but the magnitude of this risk remains unclear. Nonetheless, due to the lack of a direct comparison between FH and non-FH subjects within this study, the obtained results must be interpreted with caution. These findings underscore that carotid stenosis in FH is a poorly investigated area.

Nevertheless, all analyses demonstrated substantial heterogeneity, wide confidence intervals, and inconclusive prediction intervals. These findings likely reflect considerable variability across studies, including differences in FH diagnostic criteria, definitions of carotid plaques, and inclusion criteria based on ASCVD status. Study populations also differed markedly in terms of comorbidities (CAD, hypertension, diabetes mellitus), age distribution, and LDL-C levels. Regarding LDL-C, discrepancies arose due to inconsistent reporting, as studies did not uniformly clarify whether reported values represented the highest recorded level, calculated estimates under ongoing lipid-lowering therapy, or current measurements. Finally, variations in lipid-lowering treatment across cohorts likely further contributed to the observed heterogeneity.

The assessment of carotid atherosclerosis burden holds dual and fundamental clinical significance. On one hand, the presence of plaques in the carotid artery is widely recognized as a powerful, non-invasive surrogate marker of systemic atherosclerosis, serving as a ‘mirror’ for the overall atherosclerotic burden in other crucial vascular beds, including the CAD. On the other hand, these plaques are an independent and robust predictor of ischemic stroke and other MACCE. Consequently, confirmation that a substantial proportion of individuals with FH is affected by carotid atherosclerosis provides a foundation for more focused and clinically relevant future investigations.

Given that the weighted proportion of CAD was 13.4%, and the pooled prevalence of carotid plaques reached 52%, it cannot be concluded that, for FH patients, carotid plaques can be reliably positioned as a singular marker of total atherosclerotic burden. These results suggest substantial variability in the spectrum of atherosclerosis extent in the carotid arterial territory. In particular, in patients with genetically confirmed FH, carotid artery involvement varies tremendously. Specifically, the absence of atherosclerotic lesions in carotid arteries may fail to rule out significant CAD and therefore should not serve as a reliable risk determinant in patients with FH. This finding is highly relevant, as researchers have used carotid plaque presence to score cardiovascular risk, including cardiovascular death, MI, and ischemic stroke [44,70]. In the general population, carotid plaque progression or regression may increase or decrease the risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes [71,72]. In contrast, in FH patients, such an approach is not yet appropriate, emphasizing the need for more comprehensive and multicenter studies. Additionally, a better reappraisal of FH is required to improve the selection of patients with FH [73]. Ray et al. demonstrated that the incidence of cardiovascular events increased with age and was highest for definite FH and lowest for unlikely FH within each age category. The risk of premature cardiovascular events was significantly higher for both definite and potential FH (HR 4.21, 95% CI 3.69–4.81 and HR 3.46, 95% CI 3.07–3.89, respectively) compared to unlikely FH.

While the prevalence of carotid atherosclerosis in the general population is estimated at approximately 20% [29], our results suggest that FH patients represent a particularly vulnerable group, with prevalence rates two to three times higher. Such a marked difference suggests that atherosclerotic changes may begin early in the course of FH, potentially even before adulthood. Tada et al. and Shibayama et al. have reported that carotid plaques begin to develop in the FH population as early as adolescence [74,75]. These estimates are supported by studies on children with FH, among whom carotid atherosclerotic plaques can already be detected. Earlier studies have shown that the prevalence of carotid plaques in children with FH is approximately 10% [76,77,78]. More recent studies involving pediatric FH populations, likely due to advances in treatment methods, have reported primarily CIMT measurements rather than plaque detection [79,80].

Studies indicate that the prevalence of FH among patients with CAD is up to 20 times higher than in the general population, affecting approximately 1 in 15 individuals (6.7%) [2,3]. In light of the high prevalence of carotid atherosclerosis among FH patients, it is reasonable to expect an elevated prevalence of FH among individuals with carotid atherosclerosis, particularly those with carotid stenosis. Nevertheless, this association remains poorly established, as a review of the literature identified only two studies addressing this specific relationship, both published solely in abstract form, which substantially limits their interpretability. Ijäs et al., in a study involving 500 patients with symptomatic and asymptomatic internal carotid artery stenosis undergoing carotid endarterectomy, found that a probable or definite diagnosis of FH based on DLCN criteria applied to 1.8% of participants. However, genetic testing confirmed the diagnosis in only one individual, yielding a prevalence of 1 in 500 [81]. In another study, Perica et al. reported that a possible diagnosis of FH according to DLCN criteria was observed in 11 out of 52 patients (21.15%) with CAS treated with carotid artery stenting [82].

Carotid atherosclerosis is a strong predictor of future MACCE [28,83], which raises the question of whether individuals with FH are at higher risk of stroke. The evidence on this issue remains inconsistent. Some studies have suggested a higher incidence of stroke among individuals diagnosed with FH [84,85]; however, these observations are primarily based on clinical diagnostic criteria, which tend to overestimate the true prevalence of FH [86]. In contrast, several large observational studies and meta-analyses of genetically confirmed FH cases have failed to demonstrate a significantly elevated risk of ischemic stroke in this population [87,88,89,90,91]. This discrepancy may be explained by the fact that clinical diagnostic criteria often capture patients with existing cardiovascular disease, a strong risk factor for stroke, which may confound the observed association [92,93]. Furthermore, the apparent lack of increased ischemic stroke risk in genetically confirmed FH may reflect important differences in the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying stroke versus myocardial infarction. While coronary artery disease is directly driven by lipid accumulation and plaque rupture within the coronary arteries, ischemic stroke is more heterogeneous in origin, often resulting from embolic events, small vessel occlusion, or cardioembolic sources rather than from extracranial large-vessel atherosclerosis alone [94,95,96].

5. Limitations

Several crucial limitations must be acknowledged. Firstly, the search was restricted to English-language publications, which may introduce language bias. Secondly, the search, selection, and data extraction were conducted by a single reviewer. Thirdly, most included studies were not specifically designed to assess carotid artery plaques, with plaque evaluation often reported only as descriptive data rather than a primary objective. Fourthly, over half of the studies were of low methodological quality. Fifthly, the studies were highly heterogeneous, and evidence of publication bias was suggested by Doi plot asymmetry and high LFK index values. Sixthly, sensitivity analyses for carotid stenosis demonstrated instability of the summary effect. Collectively, these factors led to an overall certainty of evidence rated as low to moderate for carotid plaques and very low for carotid stenosis.

6. Conclusions

This meta-analysis indicates that carotid atherosclerosis may be highly prevalent in adult patients with FH, especially those with genetically confirmed FH, affecting approximately half of this population. These findings highlight the substantial gap in understanding the relationship between FH and carotid atherosclerosis. Future high-quality studies are warranted to refine prevalence estimates and to further elucidate the interplay between these conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm14248676/s1, PRISMA 2020 checklist; Figure S1: Prevalence of carotid atherosclerotic plaques in all included studies stratified by ASCVD status; Figure S2: Prevalence of carotid plaques in studies with clinical diagnosis of FH (including those with a subset of genetically confirmed cases), stratified by ASCVD status; Figure S3: Prevalence of carotid plaques in studies including only genetically confirmed FH, stratified by ASCVD status; Figure S4: DOI plots of studies included in the subgroup analysis, stratified according to the diagnostic method of FH; Figure S5: Doi plot of the studies reporting carotid stenosis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P.; methodology, M.P.; software, M.P.; validation, M.K.-W. and A.K.-Z.; formal analysis, M.K.-W. and A.K.-Z.; investigation, M.P.; resources, M.P. and A.K.-Z.; data curation, A.K.-Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P., M.K.-W. and A.K.-Z.; writing—review and editing, M.P., M.K.-W. and A.K.-Z.; visualization, M.P.; supervision, A.K.-Z.; project administration, M.P.; funding acquisition, A.K.-Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article was supported by the science fund from the Saint John Paul II Hospital, Cracow, Poland (no: FN/23/2025 to A.K.-Z.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kalwick, M.; Roth, M. A Comprehensive Review of the Genetics of Dyslipidemias and Risk of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients 2025, 17, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Dharmayat, K.I.; Stevens, C.A.T.; Sharabiani, M.T.A.; Jones, R.S.; Watts, G.F.; Genest, J.; Ray, K.K.; Vallejo-Vaz, A.J. Prevalence of Familial Hypercholesterolemia Among the General Population and Patients with Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation 2020, 141, 1742–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beheshti, S.O.; Madsen, C.M.; Varbo, A.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Worldwide Prevalence of Familial Hypercholesterolemia. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 2553–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nohara, A.; Tada, H.; Ogura, M.; Okazaki, S.; Ono, K.; Shimano, H.; Daida, H.; Dobashi, K.; Hayashi, T.; Hori, M.; et al. Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2021, 28, RV17050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuchel, M.; Raal, F.J.; Hegele, R.A.; Al-Rasadi, K.; Arca, M.; Averna, M.; Bruckert, E.; Freiberger, T.; Gaudet, D.; Harada-Shiba, M.; et al. 2023 Update on European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Statement on Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolaemia: New Treatments and Clinical Guidance. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 2277–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostis, P.; Antza, C.; Florentin, M.; Kotsis, V. Familial Hypercholesterolemia and Its Manifestations: Practical Considerations for General Practitioners. Kardiol. Pol. 2023, 81, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrowolski, P.; Kabat, M.; Kępka, C.; Januszewicz, A.; Prejbisz, A. Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Burden in Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Interpretation of Data on Involvement of Different Vascular Beds. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2022, 132, 16248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordestgaard, B.G.; Chapman, M.J.; Humphries, S.E.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Masana, L.; Descamps, O.S.; Wiklund, O.; Hegele, R.A.; Raal, F.J.; Defesche, J.C.; et al. Familial Hypercholesterolaemia Is Underdiagnosed and Undertreated in the General Population: Guidance for Clinicians to Prevent Coronary Heart Disease: Consensus Statement of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 3478–3490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elshorbagy, A.; Vallejo-Vaz, A.J.; Barkas, F.; Lyons, A.R.M.; Stevens, C.A.T.; Dharmayat, K.I.; Catapano, A.L.; Freiberger, T.; Hovingh, G.K.; Mata, P.; et al. Overweight, Obesity, and Cardiovascular Disease in Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolaemia: The EAS FH Studies Collaboration Registry. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 1127–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benn, M.; Watts, G.F.; Tybjaerg-Hansen, A.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Familial Hypercholesterolemia in the Danish General Population: Prevalence, Coronary Artery Disease, and Cholesterol-Lowering Medication. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, 3956–3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.; Sullivan, D.R.; Hare, D.L.; Colquhoun, D.M.; Bates, T.R.; Ryan, J.D.M.; Bishop, W.; Burnett, J.R.; Bell, D.A.; Simons, L.A.; et al. Gaps in the Care of Familial Hypercholesterolaemia in Australia: First Report From the National Registry. Heart Lung Circ. 2021, 30, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zhang, H.-W.; Guo, Y.-L.; Wu, N.-Q.; Zhu, C.-G.; Zhao, X.; Sun, D.; Gao, X.-Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Very Young Myocardial Infarction. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marco-Benedí, V.; Bea, A.M.; Cenarro, A.; Jarauta, E.; Laclaustra, M.; Civeira, F. Current Causes of Death in Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Lipids Health Dis. 2022, 21, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, A.I.; Akioyamen, L.E.; Lee, S.; Bélanger, A.; Ruel, I.; Hales, L.; Genest, J.; Brunham, L.R. Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolaemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2022, 29, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajufo, E.; Cuchel, M. Recent Developments in Gene Therapy for Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2016, 18, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acitelli, E.; Guedon, A.F.; De Liguori, S.; Gallo, A.; Maranghi, M. Peripheral Artery Disease: An Underdiagnosed Condition in Familial Hypercholesterolemia? A Systematic Review. Endocrine 2024, 85, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundal, L.J.; Igland, J.; Svendsen, K.; Holven, K.B.; Leren, T.P.; Retterstøl, K. Association of Familial Hypercholesterolemia and Statin Use with Risk of Dementia in Norway. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e227715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuelsson, F.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Benn, M. Familial Hypercholesterolemia and Risk of Peripheral Arterial Disease and Chronic Kidney Disease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 4491–4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.P.; Ahmed, H.M.; Wilson Tang, W.H. Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Detect, Treat, and Ask about Family. Cleve Clin. J. Med. 2020, 87, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontario Health (Quality). Genetic Testing for Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Health Technology Assessment. Ont. Health Technol. Assess. Ser. 2022, 22, 1–155. [Google Scholar]

- Boccatonda, A.; Rossi, I.; D’Ardes, D.; Cocomello, N.; Perla, F.M.; Bucciarelli, B.; Di Rocco, G.; Del Ben, M.; Angelico, F.; Guagnano, M.T.; et al. Comparison between Different Diagnostic Scores for the Diagnosis of Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Assessment of Their Diagnostic Accuracy in Comparison with Genetic Testing. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, ehaa946.3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, J.; Medeiros, A.M.; Alves, A.C.; Bourbon, M.; Antunes, M. Performance Comparison of Different Classification Algorithms Applied to the Diagnosis of Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Paediatric Subjects. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoshchenko, O.; Ivanoshchuk, D.; Semaev, S.; Orlov, P.; Zorina, V.; Shakhtshneider, E. Diagnosis of Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Children and Young Adults. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scientific Steering Committee on behalf of the Simon Broome Register Group. Risk of Fatal Coronary Heart Disease in Familial Hypercholesterolaemia. Scientific Steering Committee on Behalf of the Simon Broome Register Group. BMJ 1991, 303, 893–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tada, H.; Okada, H.; Nomura, A.; Usui, S.; Sakata, K.; Nohara, A.; Yamagishi, M.; Takamura, M.; Kawashiri, M. Clinical Diagnostic Criteria of Familial Hypercholesterolemia—A Comparison of the Japan Atherosclerosis Society and Dutch Lipid Clinic Network Criteria. Circ. J. 2021, 85, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfield-watt, P.; Gritzmacher, L.; McDowell, I.; Bayly, G.; Haralambos, K. A Comparison of Simon Broome and Welsh Criteria for Selecting Patients for Familial Hypercholesterolaemia (FH) Genetic Testing. Atherosclerosis 2018, 275, e181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruel, I.; Brisson, D.; Aljenedil, S.; Awan, Z.; Baass, A.; Bélanger, A.; Bergeron, J.; Bewick, D.; Brophy, J.M.; Brunham, L.R.; et al. the Presence of Carotid Artery Plaque and Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Genetic Hypercholesterolemia. Simplified Canadian Definition for Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Can. J. Cardiol. 2018, 34, 1210–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bea, A.M.; Civeira, F.; Jarauta, E.; Lamiquiz-Moneo, I.; Pérez-Calahorra, S.; Marco-Benedí, V.; Cenarro, A.; Mateo-Gallego, R. Association Between the Presence of Carotid Artery Plaque and Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Genetic Hypercholesterolemia. Rev. Española Cardiol. 2017, 70, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Fang, Z.; Wang, H.; Cai, Y.; Rahimi, K.; Zhu, Y.; Fowkes, F.G.R.; Fowkes, F.J.I.; Rudan, I. Global and Regional Prevalence, Burden, and Risk Factors for Carotid Atherosclerosis: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Modelling Study. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e721–e729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piechocki, M.; Przewłocki, T.; Pieniażek, P.; Trystuła, M.; Podolec, J.; Kabłak-Ziembicka, A. A Non-Coronary, Peripheral Arterial Atherosclerotic Disease (Carotid, Renal, Lower Limb) in Elderly Patients—A Review: Part I—Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Atherosclerosis-Related Diversities in Elderly Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossabhoy, S.; Arya, S. Epidemiology of Atherosclerotic Carotid Artery Disease. Semin. Vasc. Surg. 2021, 34, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Weerd, M.; Greving, J.P.; De Jong, A.W.F.; Buskens, E.; Bots, M.L. Prevalence of Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Stenosis According to Age and Sex: Systematic Review and Metaregression Analysis. Stroke 2009, 40, 1105–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechtouff, L.; Rascle, L.; Crespy, V.; Canet-Soulas, E.; Nighoghossian, N.; Millon, A. A Narrative Review of the Pathophysiology of Ischemic Stroke in Carotid Plaques: A Distinction versus a Compromise between Hemodynamic and Embolic Mechanism. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabłak-Ziembicka, A.; Przewłocki, T.; Stępień, E.; Pieniążek, P.; Rzeźnik, D.; Sliwiak, D.; Komar, M.; Tracz, W.; Podolec, P. Relationship between carotid intima-media thickness, cytokines, atherosclerosis extent and a two-year cardiovascular risk in patients with arteriosclerosis. Kardiol. Pol. 2011, 69, 1024–1031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Zheng, Z.; Feng, Z.; Lv, K.; Cao, X.; Geng, D. Risk of acute cerebral infarction in patients with hypertension based on high-resolution MRI. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2025, 15, 3000–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garoff, M.; Ahlqvist, J.; Levring Jäghagen, E.; Wester, P.; Johansson, E. Carotid Calcifications in Panoramic Radiographs Can Predict Vascular Risk. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2025, 54, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.J.; Kim, S.E.; Kim, J.Y.; Kang, J.; Kim, B.J.; Han, M.K.; Choi, K.H.; Kim, J.T.; Shin, D.I.; Cha, J.K.; et al. Five-Year Risk of Acute Myocardial Infarction After Acute Ischemic Stroke in Korea. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e018807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merkler, A.E.; Diaz, I.; Wu, X.; Murthy, S.B.; Gialdini, G.; Navi, B.B.; Yaghi, S.; Weinsaft, J.W.; Okin, P.M.; Safford, M.M.; et al. Duration of Heightened Ischemic Stroke Risk After Acute Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e010782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kablak-Ziembicka, A.; Przewlocki, T.; Pieniazek, P.; Musialek, P.; Sokolowski, A.; Drwila, R.; Sadowski, J.; Zmudka, K.; Tracz, W. The role of carotid intima-media thickness assessment in cardiovascular risk evaluation in patients with polyvascular atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2010, 209, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihle-Hansen, H.; Vigen, T.; Berge, T.; Walle-Hansen, M.M.; Hagberg, G.; Ihle-Hansen, H.; Thommessen, B.; Ariansen, I.; Røsjø, H.; Rønning, O.M.; et al. Carotid Plaque Score for Stroke and Cardiovascular Risk Prediction in a Middle-Aged Cohort From the General Population. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e030739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzouk, L.; Rockman, C.B.; Patel, M.R.; Guo, Y.; Adelman, M.A.; Riles, T.S.; Berger, J.S. Co-existence of vascular disease in different arterial beds: Peripheral artery disease and carotid artery stenosis—Data from Life Line Screening. Atherosclerosis 2015, 241, 687–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Xu, Q.; Xu, X.; Peng, J.; Lin, M.; Chen, C.E.; Zhang, S. Evaluation of the ultrasonic arterial measurement and analysis system for predicting 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in patients with type 2 diabetes. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2025, 15, 4921–4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osawa, K. Can carotid plaque assessment perform the role of a risk predictor for secondary prevention? Int. J. Cardiol. 2023, 376, 154–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabłak-Ziembicka, A.; Przewłocki, T. Clinical Significance of Carotid Intima-Media Complex and Carotid Plaque Assessment by Ultrasound for the Prediction of Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Primary and Secondary Care Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touboul, P.-J.; Hennerici, M.G.; Meairs, S.; Adams, H.; Amarenco, P.; Bornstein, N.; Csiba, L.; Desvarieux, M.; Ebrahim, S.; Hernandez Hernandez, R.; et al. Mannheim Carotid Intima-Media Thickness and Plaque Consensus (2004–2006–2011). Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2012, 34, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, E.; Grazhdani, H.; Aliotta, L.; Gavazzi, L.M.; Foti, P.V.; Palmucci, S.; Inì, C.; Tiralongo, F.; Castiglione, D.; Renda, M.; et al. Imaging of Carotid Stenosis: Where Are We Standing? Comparison of Multiparametric Ultrasound, CT Angiography, and MRI Angiography, with Recent Developments. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018 for Information Professionals and Researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz, M.F.; Guven, B.; Ebeoglu, A.O.; Gul, O.B.; Nayir, A.; Ozkan, P.; Bulat, Z.; Turk, I.; Demirelce, O.; Kimyonok, H.A.; et al. Screening for Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Insights and Implications. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdziel, J.; Fedak, A.; Kawalec, E.; Miarka, P.; Micek, A.; Małecki, M.; Walus-Miarka, M. Lipoprotein(a) Concentration and Cardiovascular Disease in a Group of Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolemia—A Lipid Clinic Experience. Clin. Cardiol. 2025, 48, e70125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, G.; Di Giacomo Barbagallo, F.; Di Marco, M.; Scilletta, S.; Miano, N.; Capuccio, S.; Musmeci, M.; Di Mauro, S.; Filippello, A.; Scamporrino, A.; et al. Evaluations of Metabolic and Innate Immunity Profiles in Subjects with Familial Hypercholesterolemia with or without Subclinical Atherosclerosis. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2025, 132, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokhina, A.V.; Ershova, A.I.; Kiseleva, A.V.; Sotnikova, E.A.; Zharikova, A.A.; Zaicenoka, M.; Vyatkin, Y.V.; Ramensky, V.E.; Kutsenko, V.A.; Litinskaya, O.A.; et al. Clinical and Biochemical Features of Atherogenic Hyperlipidemias with Different Genetic Basis: A Comprehensive Comparative Study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0315693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malo, A.-I.; Girona, J.; Ibarretxe, D.; Rodríguez-Borjabad, C.; Amigó, N.; Plana, N.; Masana, L. Serum Glycoproteins A and B Assessed by 1H-NMR in Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis 2021, 330, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenova, A.E.; Sergienko, I.V.; García-Giustiniani, D.; Monserrat, L.; Popova, A.B.; Nozadze, D.N.; Ezhov, M.V. Verification of Underlying Genetic Cause in a Cohort of Russian Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolemia Using Targeted Next Generation Sequencing. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2020, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgórski, M.; Szatko, K.; Stańczyk, M.; Pawlak-Bratkowska, M.; Konopka, A.; Starostecka, E.; Tkaczyk, M.; Góreczny, S.; Rutkowska, L.; Gach, A.; et al. “Apple Does Not Fall Far from the Tree”—Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Children with Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Lipids Health Dis. 2020, 19, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattina, A.; Giammanco, A.; Giral, P.; Rosenbaum, D.; Carrié, A.; Cluzel, P.; Redheuil, A.; Bittar, R.; Béliard, S.; Noto, D.; et al. Polyvascular Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Familial Hypercholesterolemia: The Role of Cholesterol Burden and Gender. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2019, 29, 1068–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.-X.; Liu, H.-H.; Sun, D.; Jin, J.-L.; Xu, R.-X.; Guo, Y.-L.; Wu, N.-Q.; Zhu, C.-G.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; et al. The Different Relations of PCSK9 and Lp(a) to the Presence and Severity of Atherosclerotic Lesions in Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis 2018, 277, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Zhou, B.; Zhao, X.; Li, S.; Zhu, C.; Guo, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wu, N.; Liu, G.; Dong, Q.; et al. Lipoprotein(a) Level Associates with Coronary Artery Disease Rather than Carotid Lesions in Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolemia. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2018, 32, e22442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, S.; Duvekot, M.H.C.; ten Kate, G.-J.R.; Verhoeven, A.J.M.; Mulder, M.T.; Schinkel, A.F.L.; Nieman, K.; Watts, G.F.; Sijbrands, E.J.G.; Roeters van Lennep, J.E. Carotid Artery Plaques and Intima Medial Thickness in Familial Hypercholesteraemic Patients on Long-Term Statin Therapy: A Case Control Study. Atherosclerosis 2017, 256, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waluś-Miarka, M.; Czarnecka, D.; Wojciechowska, W.; Kloch-Badełek, M.; Kapusta, M.; Sanak, M.; Wójcik, M.; Małecki, M.T.; Starzyk, J.; Idzior-Waluś, B. Carotid Plaques Correlates in Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Angiology 2016, 67, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Oord, S.C.H.; Akkus, Z.; Roeters van Lennep, J.E.; Bosch, J.G.; van der Steen, A.F.W.; Sijbrands, E.J.G.; Schinkel, A.F.L. Assessment of Subclinical Atherosclerosis and Intraplaque Neovascularization Using Quantitative Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound in Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis 2013, 231, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, P.; Alonso, R.; Rosado, P.; Mata, N.; Fernández-Friera, L.; Jiménez-Borreguero, L.J.; Badimon, L.; Mata, P. Detection of Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Familial Hypercholesterolemia Using Non-Invasive Imaging Modalities. Atherosclerosis 2012, 222, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taira, K.; Bujo, H.; Kobayashi, J.; Takahashi, K.; Miyazaki, A.; Saito, Y. Positive Family History for Coronary Heart Disease and ‘Midband Lipoproteins’ Are Potential Risk Factors of Carotid Atherosclerosis in Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis 2002, 160, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendelhag, I.; Wiklund, O.; Wikstrand, J. On Quantifying Plaque Size and Intima-Media Thickness in Carotid and Femoral Arteries. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1996, 16, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funabashi, S.; Kataoka, Y.; Hori, M.; Ogura, M.; Doi, T.; Noguchi, T.; Harada-Shiba, M. Characterization of Polyvascular Disease in Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Its Association with Circulating Lipoprotein(a) Levels. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e025232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasta, A.; Cremonini, A.L.; Formisano, E.; Fresa, R.; Bertolini, S.; Pisciotta, L. Long Term Follow-up of Genetically Confirmed Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolemia Treated with First and Second-Generation Statins and Then with PCSK9 Monoclonal Antibodies. Atherosclerosis 2020, 308, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soljanlahti, S.; Autti, T.; Hyttinen, L.; Vuorio, A.F.; Keto, P.; Lauerma, K. Compliance of the Aorta in Two Diseases Affecting Vascular Elasticity, Familial Hypercholesterolemia and Diabetes: A MRI Study. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2008, 4, 1103–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koga, N.; Watanabe, K.; Kurashige, Y.; Sato, T.; Hiroki, T. Long-term Effects of LDL Apheresis on Carotid Arterial Atherosclerosis in Familial Hypercholesterolaemic Patients. J. Intern. Med. 1999, 246, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Weerd, M.; Greving, J.P.; Hedblad, B.; Lorenz, M.W.; Mathiesen, E.B.; O’Leary, D.H.; Rosvall, M.; Sitzer, M.; Buskens, E.; Bots, M.L. Prevalence of Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Stenosis in the General Population. Stroke 2010, 41, 1294–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsioulos, G.; Kounatidis, D.; Vallianou, N.G.; Poulaki, A.; Kotsi, E.; Christodoulatos, G.S.; Tsilingiris, D.; Karampela, I.; Skourtis, A.; Dalamaga, M. Lipoprotein(a) and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: Where Do We Stand? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-I.; Park, K.-H.; Kim, U.; Kim, H.-J.; Choi, K.-U.; Nam, J.-H.; Lee, C.-H.; Son, J.-W.; Park, J.-S. Contributing Factors to the Short-Term Progression of Carotid Plaque and Its Relation to Cardiovascular Outcomes. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2025, 19, 878–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacoń, J.; Przewłocki, T.; Podolec, J.; Badacz, R.; Pieniażek, P.; Mleczko, S.; Ryniewicz, W.; Żmudka, K.; Kabłak-Ziembicka, A. Prospective Study on the Prognostic Value of Repeated Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Assessment in Patients with Coronary and Extra Coronary Steno-Occlusive Arterial Disease. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2018, 129, 808–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, K.K.; Pillas, D.; Hadjiphilippou, S.; Khunti, K.; Seshasai, S.R.K.; Vallejo-Vaz, A.J.; Neasham, D.; Addison, J. Premature Morbidity and Mortality Associated with Potentially Undiagnosed Familial Hypercholesterolemia in the General Population. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2023, 15, 100580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tada, H.; Kawashiri, M.; Okada, H.; Nakahashi, T.; Sakata, K.; Nohara, A.; Inazu, A.; Mabuchi, H.; Yamagishi, M.; Hayashi, K. Assessments of Carotid Artery Plaque Burden in Patients With Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Am. J. Cardiol. 2017, 120, 1955–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibayama, J.; Tada, H.; Sakata, K.; Usui, S.; Takamura, M.; Kawashiri, M. The Assessment of Carotid Atherosclerotic Plaque among Young Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Intern. Med. 2022, 61, 3165–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spengel, F.A.; Kaess, B.; Keller, C.; Kröner, K.K.; Schreiber, M.; Schuster, H.; Zöllner, N. Atherosclerosis of the Carotid Arteries in Young Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Klin. Wochenschr. 1988, 66, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonstad, S.; Joakimsen, O.; Bugge, S.; Ose, L.; Bønaa, K.H.; Leren, T.P. Carotid Intima–Media Thickness and Plaque in Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolaemia Mutations and Control Subjects. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 28, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedman, M.; Matikainen, T.; Föhr, A.; Lappi, M.; Piippo, S.; Nuutinen, M.; Antikainen, M. Efficacy and Safety of Pravastatin in Children and Adolescents with Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia: A Prospective Clinical Follow-Up Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 1942–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Borjabad, C.; Ibarretxe, D.; Girona, J.; Ferré, R.; Feliu, A.; Amigó, N.; Guijarro, E.; Masana, L.; Plana, N.; Fèlix, A.; et al. Lipoprotein Profile Assessed by 2D-1H-NMR and Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Children with Familial Hypercholesterolaemia. Atherosclerosis 2018, 270, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, L.M.; Hutten, B.A.; Tsimikas, S.; Yeang, C.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Kroon, J.; Revers, A.; Kastelein, J.J.P.; Wiegman, A. Lipoprotein(a) Levels and Carotid Intima-Media Thickness in Children: A 20-Year Follow-up Study. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2024, 18, e290–e294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ijäs, P.; Kemppainen, K.; Häppölä, P.; Eriksson, H.; Sebastian, R.; Palta, P.; Nuotio, K.; Vikatmaa, P.; Soinne, L.; Lindsberg, P.J.; et al. Familial Hypercholesterolaemia and LDL-C Polygenic Risk in Patients with Severe Carotid Artery Stenosis. Atherosclerosis 2021, 331, e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perica, D.; Paponja, K.; Leskovar, D.; Šućur, N.; Hauptman, A.G.; Ljevak, J.; Reiner, Ž.; Pećin, I. Screening for Familial Hypercholesterolemia among Patients with Internal Carotid Artery Stenosis. Atherosclerosis 2023, 379, S120–S121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacoń, J.; Przewlocki, T.; Podolec, J.; Badacz, R.; Pieniazek, P.; Ryniewicz, W.; Żmudka, K.; Kabłak-Ziembicka, A. The Role of Serial Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Assessment as a Surrogate Marker of Atherosclerosis Control in Patients with Recent Myocardial Infarction. Postepy Kardiol. Interwencyjnej 2019, 15, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyen, B.; Qureshi, N.; Kai, J.; Akyea, R.K.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Roderick, P.; Humphries, S.E.; Weng, S. Risk of Cardiovascular Disease Outcomes in Primary Care Subjects with Familial Hypercholesterolaemia: A Cohort Study. Atherosclerosis 2019, 287, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beheshti, S.; Madsen, C.M.; Varbo, A.; Nordestgaard, B.G. 2.6-Fold Risk of Ischemic Stroke in Individuals with Clinical Familial Hypercholesterolemia: The Copenhagen General Population Study with 102,961 Individuals. Atherosclerosis 2017, 263, e235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toft-Nielsen, F.; Emanuelsson, F.; Benn, M. Familial Hypercholesterolemia Prevalence Among Ethnicities—Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 840797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svendsen, K.; Olsen, T.; Vinknes, K.J.; Mundal, L.J.; Holven, K.B.; Bogsrud, M.P.; Leren, T.P.; Igland, J.; Retterstøl, K. Risk of Stroke in Genetically Verified Familial Hypercholesterolemia: A Prospective Matched Cohort Study. Atherosclerosis 2022, 358, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beheshti, S.; Madsen, C.M.; Varbo, A.; Benn, M.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Relationship of Familial Hypercholesterolemia and High Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol to Ischemic Stroke. Circulation 2018, 138, 578–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovland, A.; Mundal, L.J.; Igland, J.; Veierød, M.B.; Holven, K.B.; Bogsrud, M.P.; Tell, G.S.; Leren, T.P.; Retterstøl, K. Risk of Ischemic Stroke and Total Cerebrovascular Disease in Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Stroke 2019, 50, 172–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akioyamen, L.E.; Tu, J.V.; Genest, J.; Ko, D.T.; Coutin, A.J.S.; Shan, S.D.; Chu, A. Risk of Ischemic Stroke and Peripheral Arterial Disease in Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia: A Meta-Analysis. Angiology 2019, 70, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez de Isla, L.; Alonso, R.; Mata, N.; Saltijeral, A.; Muñiz, O.; Rubio-Marin, P.; Diaz-Diaz, J.L.; Fuentes, F.; de Andrés, R.; Zambón, D.; et al. Coronary Heart Disease, Peripheral Arterial Disease, and Stroke in Familial Hypercholesterolaemia. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2016, 36, 2004–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piechocki, M.; Przewłocki, T.; Pieniążek, P.; Trystuła, M.; Podolec, J.; Kabłak-Ziembicka, A. A Non-Coronary, Peripheral Arterial Atherosclerotic Disease (Carotid, Renal, Lower Limb) in Elderly Patients—A Review PART II—Pharmacological Approach for Management of Elderly Patients with Peripheral Atherosclerotic Lesions outside Coronary Territory. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1508. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, K.; Katzenellenbogen, J.M.; Kleinig, T.J.; Kim, J.; Budgeon, C.A.; Thrift, A.G.; Nedkoff, L. Large Burden of Stroke Incidence in People with Cardiac Disease: A Linked Data Cohort Study. Clin. Epidemiol. 2023, 15, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheldeman, L.; Sinnaeve, P.; Albers, G.W.; Lemmens, R.; Van de Werf, F. Acute Myocardial Infarction and Ischaemic Stroke: Differences and Similarities in Reperfusion Therapies—A Review. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 2735–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badacz, R.; Przewłocki, T.; Legutko, J.; Żmudka, K.; Kabłak-Ziembicka, A. microRNAs Associated with Carotid Plaque Development and Vulnerability: The Clinician’s Perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widimsky, P.; Coram, R.; Abou-Chebl, A. Reperfusion Therapy of Acute Ischaemic Stroke and Acute Myocardial Infarction: Similarities and Differences. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).